Abstract

Background

In the initiation and maintenance of arrhythmia, inflammatory processes play an important role. IL-2 is a pro-inflammatory factor which is associated with the morbidity of arrhythmias, however, how IL-2 affects the cardiac electrophysiology is still unknown.

Methods

In the present study, we observed the effect of IL-2 by qRT-PCR on the transcription of ion channel genes including SCN2A, SCN3A, SCN4A, SCN5A, SCN9A, SCN10A, SCN1B, SCN2B, SCN3B, KCNN1, KCNJ5, KCNE1, KCNE2, KCNE3, KCND3, KCNQ1, KCNA5, KCNH2 and CACNA1C. Western blot assays and electrophysiological studies were performed to demonstrate the effect of IL-2 on the translation of SCN3B/scn3b and sodium currents.

Results

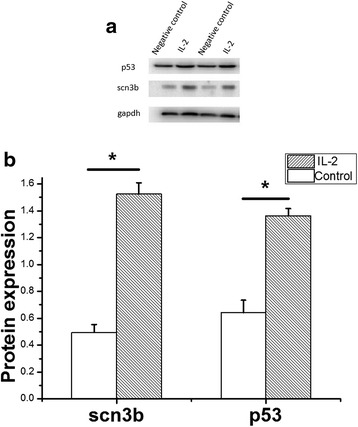

The results showed that transcriptional level of SCN3B was up-regulated significantly in Hela cells (3.28-fold, p = 0.022 compared with the control group). Consistent results were verified in HL-1 cells (3.73-fold, p = 0.012 compared with the control group). The result of electrophysiological studies showed that sodium current density increased significantly in cells which treated by IL-2 and the effect of IL-2 on sodium currents was independent of SCN3B (1.4 folds, p = 0.023). Western blot analysis showed IL-2 lead to the significantly increasing of p53 and scn3b (2.1 folds, p = 0.021 for p53; 3.1 folds, p = 0.023 for scn3b) in HL-1 cells. Consistent results were showed in HEK293 cells using qRT-PCR analysis (1.43 folds for P53, p = 0.022; 1.57 folds for SCN3B, p = 0.05).

Conclusions

The present study suggested that IL-2, may play role in the arrhythmia by regulating the expression of SCN3B and sodium current density.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12872-015-0179-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Interleukin-2, SCN3B, Sodium current density, p53

Background

In the initiation and maintenance of arrhythmia, inflammatory processes play an important role. Clinic studies have observed that pro-inflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), Interleukin 1 (IL-1) family members [1] and monocyte chemo attractant protein 1 (MCP-1) were associated with arrhythmia [2]. Basic studies also revealed that pro-inflammatory factors could regulate the expression of ion channel genes and induced abnormal cardiac electrophysiological activity [3, 4].

IL-2 is a pro-inflammatory factor which can induce T-cell proliferation, regulate the expression of Na/K pump in human lymphocytes [5] and participate in inflammatory processes. IL-2 has been reported to be associated with various cardiac arrhythmias including atrial fibrillation (AF) and ventricular tachycardia (VT). Ioannis Rizos et al. found that low serum IL-2 was associated with hypertension and/or chronic stable coronary artery disease and recent onset AF [6]. Lukasz Hak et al. observed that high serum level concentration of IL-2 might be a predictive factor for early postoperative AF in cardiopulmonary bypass graft (CABG) patients [7]. Although studies observed that IL-2 was associated with the morbidity of arrhythmias, however, how IL-2 affects the cardiac electrophysiology is still unknown.

In the present study, we hypothesized that IL-2 might affect ion channels directly as a pro-inflammatory cytokine, and observed the effect of IL-2 on the expression of ion channel genes including SCN2A, SCN3A, SCN4A, SCN5A, SCN9A, SCN10A, SCN1B, SCN2B, SCN3B, KCNN1, KCNJ5, KCNE1, KCNE2, KCNE3, KCND3, KCNQ1, KCNA5, KCNH2 and CACNA1C[8].

Methods

Cell lines and plasmids

Cell lines HEK293 (Human embryonic kidney cell), HeLa (Human cervical carcinoma cell) and mouse myocardial HL-1 cells were used in the study ((American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA).

HEK293 and HeLa cells were cultured in the Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) in the humidified incubator with 5 % CO2 at 37 °C. For HL-1 cells, tissue culture flasks were coated with 0.02 % gelatin and 5 μg/ml fibronectin (Gibco Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and incubated at 37 °C overnight. Then gelatin/fibronectin was removed, and HL-1 cells were cultured in the flasks. HL-1 cells were cultured in Claycomb medium (Gibco Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM norepinephrine,100U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 10 % FBS (Gibco Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) in the humidified incubator with 5 % CO2 at 37 °C.

Cultured cells were treated by IL-2 [IL-2 treated group: 1 ng/μl IL-2 (PeproTech, New Jersey, USA) was diluted into 100 ng/μl by ddH2O)] or ddH2O (control group) respectively when cells were cultured for 70-80 % confluent in plates.

The full length cDNA of SCN5A (GenBank: NC_000003.11) and SCN3B (GenBank: NC_000011.9) were amplified using human genomic cDNA and cloned them into plasmid of pcDNA 3.0 and pEGFP-N1 (pcDNA-SCN5A and pEGFP-N1-SCN3B) respectively.

Quantitative real time PCR analysis

Cells were harvested after 48 h and then lysed by using RNAiso plus (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Total RNA was isolated from cells and converted into cDNA by reverse transcription with the First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Toyobo, Japan) using OligodT.

qRT-PCR analysis was carried out using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master kit (Roche Applied Science, Mannhein, Germany) with 10 μl reaction volume on ABI 7900 Genome Analyzer System. The reaction system was 2 μl cDNA template, 5 μl SYBR green (including ROX) mix, 200nM forward and reverse primers. Human gene GAPDH was used as internal standard for HEK293 and HeLa cells, mouse gene Gapdh was used as internal standard for HL-1 cells. The primers for RT-qPCR analysis were listed in Table 1. The PCR products were verified by melting curve analysis and the results were analyzed using 2-ΔΔCt method as described [9]. Each examination was performed in triplicated and repeated at least three times.

Table 1.

The primers of cDNA of ion channels related genes and GAPDH/Gapdh for RT-PCR analysis

| Gene | F | R |

|---|---|---|

| SCN3B(human) | attgtttcccctggcttctc | gcctccacctcctctctctt |

| Scn3b(mouse) | catcctcctggtcttcctcac | cgggtaccacagagttctcct |

| P53(human) | ccccagccaaagaagaaacc | gcctgggcatccttgagttc |

| CACNA1C | ggctgctgaggattttcaag | acacagtgaggagggactgg |

| KCNE3 | tccagagacatcctgaagagg | ggtctccgttccattggtag |

| KCND3 | tgatgttttatgccgagaagg | ccatggtgactccagctctt |

| KCNN1 | agccaccctctctcccagtca | aggggttgggctcgctgca |

| SCN2A | atgatgaaaatggcccaaag | ggtggcactgaatcgagaga |

| SCN3A | atgctgggctttgttatgct | ttgctcctttcccagtaagc |

| SCN4A | tccagcagggttggaatatc | tgccaatgatcttgatgagc |

| SCN5A | ccagatctctatggcaatcca | gaatcttcacagccgctctc |

| SCN9A | gatgatgaagaagccccaaa | gtggcattgaaacggaagat |

| SCN10A | acttgaaagcctgcaaccag | cactaaaccgggaaatggtc |

| SCN1B | tctaccgcctgctcttcttc | ggcagcgatcttcttgtagc |

| SCN2B | atccatctgcaggtcctcat | catctgtgctcagcttctgc |

| KCNQ1 | ggccacggggactctcttc | tccgtcccgaagaacacca |

| KCNA5 | ggccgaccccttcttcatc | gcagctcgaaggtgaaccag |

| KCNH2 | gaggagcgcaaagtggaaatc | gccccatcctcgttcttcac |

| KCNJ5 | ttctgaagggagcaggtcat | cctagaatcgccagccatag |

| KCNE2 | cttgtgtgcaacccagaaga | gtcttccagcgtctgtgtga |

| Gapdh(mouse) | tggccttccgtgttcctacc | ggtcctcagtgtagcccaagatg |

| GAPDH(human) | aaggtgaaggtcggagtcaac | ggggtcattgatggcaacaata |

Electrophysiological studies

The sodium current was detected by patch-clapping on HEK293 cells. When HEK293 cells were cultured for 70–80 % confluent in 9.6 cm2 plates, 2 μg pcDNA-SCN5A and 500 ng pEGFP-N1 or 1 μg pcDNA-SCN5A and 1 μg pEGFP-N1-SCN3B were transfected into cells using lipofectamine2000 and Opti-Modified Eagle’s medium (OMEM). After cultured for 4–6 h, OMEM was replaced with DMEM and 1 ng/μl IL-2 was added into IL-2 treated group as well as ddH2O was added into control group. Cells were cultured for 48 h and GFP-positive cells were selected for electrophysiological studies.

Sodium current were recorded at room temperature (22 °C–25 °C) using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA) [10]. Patch pipettes (tip resistance was 2–3MΩ) were filled with following solutions as described previously [11]: 20 mM NaCl, 130 mM CsCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM EGTA, pH 7.2, with CsOH. The components of bath solution was 70 mM NaCl, 80 mM CsCl,5.4 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, pH 7.3, with CsOH (All products were purchased from Sigma, Madison, WI, USA). Junction potential, capacitance and series resistance were automatically compensated in the whole cell configuration. The holding potential was maintained at -120 mV, and the voltage clamp were operated as described [12]. The sodium currents were filtered at 5 kHz, sampled at 50 kHz, and stored on a desktop computer with equipped with an AD converter (Digidata 1440A, Molecular Devices). All current measurements were normalized using the cell capacitance. The Clampfit 10.2 (Axon Instruments), Excel (Microsoft), and Origin 85 (Microcal Software) were used for data acquisition and analysis.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed to observe the expression of proteins in HL-1 cells after stimulating by mouse homologous IL-2. Cells were cultured in 9.6 cm2 plates and transfected as described. After 48 h, cells were harvested and incubated in ice-cold TNEN lysis buffer (in mmol/L: 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2.0 mM EDTA, 1.0 % Nonidet P-40) with 1 mini tab of EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche) and 1 mmol/L PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) for 30 min at 4 °C. The insoluble fraction was pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000 x g for 15 min at 4 °C. 100 μl of supernatant was mixed with 20 μl of 6X laemmli buffer (0.3 mol/L Tris–HCl, 6%SDS, 60 % glycerol, 120 mmol/L dithiothreitol (DDT) and proprietary pink tracking dye), and heated at 37 °C for 10 min. 20 μl of samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto a 0.45um polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore) after electrophoresis. The membrane was probed with an anti-p53 mouse monoclonal antibody (abcam, PAb240) or anti-scn3b rabbit polyclonal antibody (GeneTex, GTX104440), followed by incubation with a HRP-conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit antibody respectively (Millipore). The protein signal was visualized by a Super Signal West Pico Chemi luminescent substrate according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Illinois, USA). Mouse GAPDH (Proteintech, 14C10) was used as loading control. Each assay was performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times.

Statistical analysis

All the experimental data were from three independent experiments and presented as means and standard deviation (S.D.). Statistical analysis was performed with a Student’s t-test using SPSS version 17.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Differences were considered significant when P value < 0.05. Multiple comparisons were applied using Bonferroni correction and Benjamini-Hochberg correction.

For analysis of the data from real-time RT-PCR analysis, we calculated the means for RQ values from the 3 wells and then compare the means from three independent experiments between two different groups with a Student’s t-test. For Western blot analysis, the images from three independent experiments were scanned with Quantity One 4.6.8 (Basic) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) and quantified. The means from three independent experiments were compared between two different groups with a Student’s t-test.

Results

IL-2 up-regulated the expression of SCN3B/Scn3b

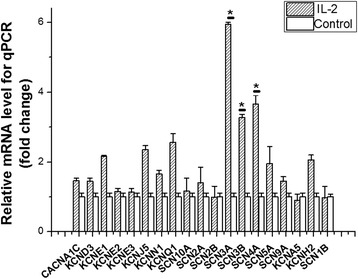

SCN2A, SCN3A, SCN4A, SCN5A, SCN9A, SCN10A, SCN1B, SCN2B, SCN3B, KCNN1, KCNJ5, KCNE1, KCNE2, KCNE3, KCND3, KCNQ1, KCNA5, KCNH2 and CACNA1C were endogenous expressed in HeLa cell lines (Fig. 1). After treating with 1 ng/μl IL-2 (IL-2 treated groups) or ddH2O (control groups) for 48 h, the mRNA levels of SCN3A, SCN3B and SCN4A were up-regulated in IL-2 treated groups (Fig. 1) and the mRNA level of SCN3B was up-regulated most significantly (3.28 folds, p = 0.02 compared with the control groups). The mRNA levels of KCNE1, KCNJ5, KCNH2 and KCNQ1 were also up-expressed over 2-fold in IL-2 treated group but were not significant compared with the control groups (p > 0.05). The rest genes including SCN1B, CACNA1C, KCND3, KCNE2, KCNE3, KCNN1, SCN10A, SCN2A, SCN5A, SCN9A and KCNA5 were up-expressed less than 2-fold. The results showed that IL-2 significantly increased the transcriptional level of several genes which encoded the subunit of sodium channels (SCN3A, SCN3B and SCN4A).

Fig. 1.

Effect of dealing with interleukin 2 (IL-2) on regulation of ion channels endogenous expressed in Human cervical carcinoma cells (HeLa cells) by quantitative real-time chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis. The mRNA samples were prepared from transfected HeLa cells. GAPDH was used as a control for normalization. SCN3A, SCN3B and SCN4A were up-regulated in transcription over 3-fold. KCNE1, KCNJ5, KCNH2 and KCNQ1 were also up-expression over 2-fold. Each experiment was performed in triplicate presented as means and standard deviation (S.D.). *p < 0.05

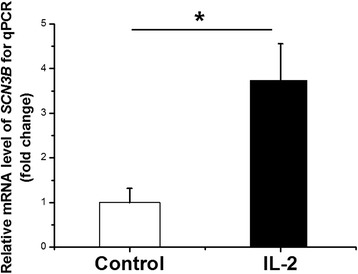

Because SCN3A and SCN4A mostly expressed in brain and skeletal muscle respectively, while SCN3B expressed in myocardium, then we carried out the experiment on mouse myocardial HL-1 cells and observed that the mRNA level of Scn3b was still up-regulated significantly (Fig. 2. 3.73 folds, p = 0.01 compared with the control groups). To control of multiple comparisons, we first applied the Bonferroni correction to calculate adjusted p values across 19 genes, unfortunately none of genes stood out (<0.05/19). Furthermore we applied Benjamini-Hochberg correction which was less conversed, but the results was consistent with Bonferroni correction. To reduce false positive signal due to our small sample size, we further validated the top signal SCN3B in a second independent experiments. Consistent results were showed in HEK293 cells using RT-PCR analysis (Additional file 1: Figure S1, 1.57 folds for SCN3B, p = 0.05; 1.43 folds for P53, p = 0.02). Based on above, we think the top gene SCN3B is an idea candidate for further electrophysiological studies.

Fig. 2.

Effect of dealing with interleukin 2 (IL-2) on regulation of Scn3b in mouse myocardial HL-1 cells by quantitative real-time chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis. The mRNA samples were prepared from transfected HL-1 cells. Gapdh was used as a control for normalization. Scn3b was 3.73-fold up-regulated in transcription (p = 0.01). Each experiment was performed in triplicate presented as means and standard deviation (S.D.). *p < 0.05

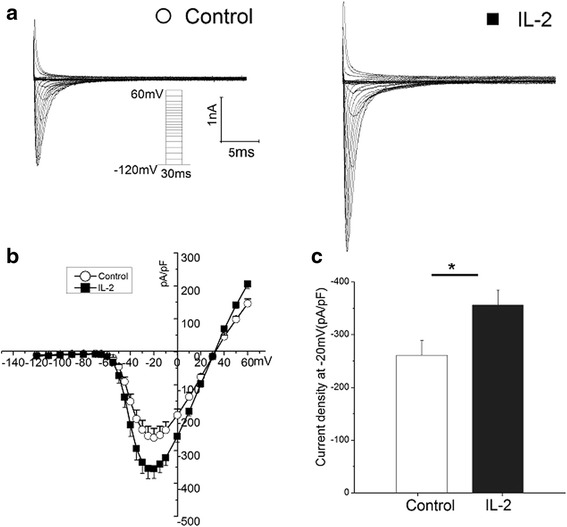

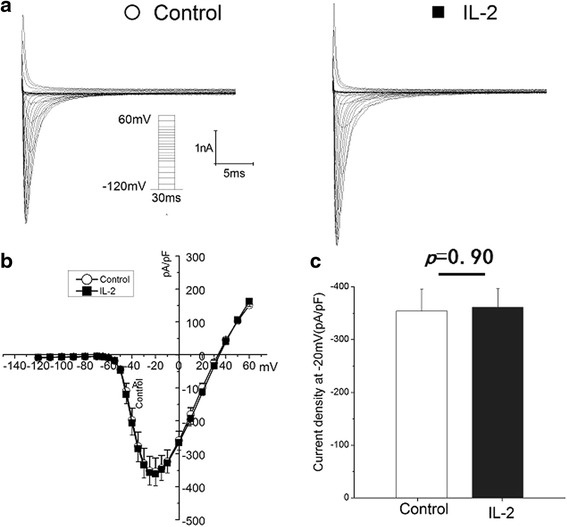

IL-2 causes the gain-of-function-like effect of SCN3B and increases the sodium current (INa)

The sodium current was commonly analyzed by patch-clapping of HEK293 cells. In order to determine if IL-2 affect the sodium current via increasing the expression level of SCN3B, we transfected both SCN3B and SCN5A or only SCN5A into HEK293 cells. The sodium current density (expressed as peak current normalized to cell capacitance, pA/pF) across the range of test potentials was significantly increased after treated by IL-2 (Fig. 3a and b). Comparing to untreated cells, the sodium current density across the range of test potentials was increased 1.4 folds in the cells which were transfected both SCN3B and SCN5A after IL-2 treated (Fig. 3c, p = 0.02). While IL-2 failed to affect the sodium currents in cells expressing the SCN5A (Fig. 4, p = 0.90) alone.

Fig. 3.

Interleukin 2 (IL-2) increased the sodium current density dependent on SCN3B. a Representative traces for sodium currents without (left) and with (right) treated by IL2were elicited with the current protocol depicted in the inset. b. I-V relation for peak sodium current Nav1.5. Average Nav1.5 sodium current density is greater by treatment of IL2 in the presence of SCN3B. c Histogram of sodium current densities at −20 mV. Means and SEM: Control (−260.6 and 28.1 pF/pA n = 17), IL2 (−355.9 and 28.3 pF/pA n = 21).*p < 0.05

Fig. 4.

Interleukin 2 (IL-2) failed to increase the sodium current density in the absence of SCN3B. a Representative traces for sodium currents without (left) and with (right) treated by IL-2 were elicited with the current protocol depicted in the inset. b. I-V relation for peak sodium current Nav1.5. Average Nav1.5 sodium current density is similar between with and without IL-2 in the absence of SCN3B. c Histogram of sodium current densities at −20 mV. Means and SEM: Control (−354.7 and 41.7 pF/pA n = 20), IL2 (−361.0 and 35.3 pF/pA n = 17). NS = Not Significant

IL-2 actively regulates the expression of p53 and scn3b in mouse myocardial cells

Because IL-2 actively regulates the expression of p53 in T cells [13] and p53 induces the expression of SCN3B in proapoptotic cells [14]. Then we performed the Western blot analysis to identify the effect of IL-2 on the expression of p53 and SCN3B in mouse myocardial HL-1 cells. The results showed that IL-2 significantly increased the expression level of p53 and scn3b (Fig. 5, 2.1 folds, p = 0.02 for p53; 3.1 folds, p = 0.02 for scn3b) in HL-1 cells.

Fig. 5.

The expression of p53 and scn3b in HL-1 cells induced by Interleukin 2 (IL-2) by Western blot analysis. The protein samples were prepared from transfected HL-1 cells. Gapdh was used as a control for normalization. P53 and Scn3b were significantly increased induced by IL-2 compared with negative control. The images of Western blot analysis shown in (a) were scanned, quantified and plotted in (b). Data is shown as means and SD

Discussion

In the present study, we observed that pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-2 can affect the expression of SCN3B, which encodes the β3 subunit for sodium channels [15], and increase the sodium current by the its effect on SCN3B for the first time.

IL-2 is a potent inducer for T cell proliferation as well as Th1 and Th2 differentiation and has been demonstrated may act as a key factor for many cardiovascular diseases and arrhythmia such as AF [2]. Previous studies showed that IL-2 could increase activity of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase but decrease its sensitivity to calcium in rat cardiomyocytes and IL-2 affected Ca2+ not from reduced activity of the L-type calcium channel [16]. Similar to above results, we observed that IL-2 didn’t affect the mRNA level of the CACNA1C, which encode the α1C subunit of L-type calcium channel. However, IL-2 can increase the mRNA level of genes which encodes the subunit for sodium channels, especially SCN3B.SCN3B encodes the β3 subunit for sodium channels and in 2009, Dan Hu, et al. detected a missense mutation (L10P) in exon 1 of SCN3B and provided the mutation led to an 82.6 % decrease in peak sodium current density, accelerated inactivation, slowed reactivation, a −9.6 mV shift of half-inactivation voltage and clinical manifestation of a Brugada syndrome, which is a disorder characterized by malignant ventricular arrhythmia and sudden death [17]. Subsequently, Carmen R. V., et al. identified a mutation V54G in SCN3B in a 20-year-old male who suffered ventricular fibrillation (VF) and observed that mutation V54G in SCN3B decrease peak sodium current significantly.[18]. The same year, we identified a mutation A130V in SCN3B dramatically decreased the cardiac sodium current density and led to AF by a dominant negative mechanism, in which the mutant protein negated or counteracted with the function of wild type SCN3B [19]. Then Morten S. Olesen et al. sequenced coding sequence of SCN3B in 192 unrelated AF patients and found three non-synonymous mutations in SCN3B, which led to loss of function in the sodium current by affecting biophysical parameters of conducted sodium current [20]. Furthermore, SCN3B knockout mice developed AF under atrial burst pacing protocols [21]. These results suggested that SCN3B may be critical to the pathogenesis of arrhythmia. Mutations in SCN3B impaired intracellular trafficking of sodium channel Nav1.5 to plasma membranes, decreased the density of cardiac sodium currents and play role in the mechanism of arrhythmia [22]. In present study, we observed that high expression level of the SCN3B which induced by IL-2 can increase the sodium current density, these results suggested that increased serum level of IL-2 can affect various cardiac arrhythmias [6, 7] by its effect on the SCN3B and sodium current density. In the present study, the increased expression of scn3b was associated with the expression level of p53, which was induced by IL-2 significantly. The results indicated that the IL-2 related expression of SCN3B may be regulated via the p53 pathway [13] and further studies are needed to reveal the exact mechanism.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study suggested that IL-2, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, may play role in the arrhythmia by its affection on SCN3B and sodium current density.

Limitation

In the present study, we observed the effect of IL-2 on the transcription of ion channel genes including SCN2A, SCN3A, SCN4A, SCN5A, SCN9A, SCN10A, SCN1B, SCN2B, SCN3B, KCNN1, KCNJ5, KCNE1, KCNE2, KCNE3, KCND3, KCNQ1, KCNA5, KCNH2 and CACNA1C. Based on the above findings, we speculate that the top gene SCN3B might be a good candidate. Nevertheless, it never rules out the possibility of false positive signal because it didn’t stand out after multiple comparisons. Further parallel and independent studies with larger sample size are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program: 2013CB531103), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 91439109, 81270163 and 31471204), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents at the University of China (NCET-11-0181).

Abbreviations

- AF

Atrial fibrillation

- IL-2

Interleukin 2

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- hsCRP

High sensitivity C reactive protein

- TNF-α

Pro-inflammatory factors tumor necrosis factor α

- IL-1

Interleukin 1

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemo attractant protein 1

- VT

Ventricular tachycardia (VT)

- CABG

Cardiopulmonary bypass graft

- PAF

Postoperative AF

Additional file

Effect of dealing with interleukin 2 (IL-2) on regulation of SCN3B and P53 in HEK293 cells by quantitative real-time chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis. The mRNA samples were prepared from transfected HEK293 cells. GAPDH was used as a control for normalization. SCN3B was 3.1-fold up-regulated in transcription (p = 0.02) and P53 was 2.1-fold up-regulated in transcription (p = 0.05). Each experiment was performed in triplicate presented as means and standard deviation (S.D.). *p < 0.05. (JPEG 106 kb)

Footnotes

Yuanyuan Zhao, Qiaobing Sun, Zhipeng Zeng and Qianqian Li contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YYZ and QBS performed qRT-PCR. ZPZ and YMX performed electrophysiological studies. YYZ, MCZ and QQL cultured Hela and HEK293 cells. QQL performed the Western blot analysis. SYZ, YYZ, YLX, XC, QW and XT conceived the study, participated in its design, contributed to the interpretation of the results and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yuanyuan Zhao, Email: 494730998@qq.com, Email: zoe007805@gmail.com.

Qiaobing Sun, Email: 576981705@qq.com.

Zhipeng Zeng, Email: peng5760242@163.com.

Qianqian Li, Email: 337030810@qq.com.

Shiyuan Zhou, Email: 13437285880@163.com.

Mengchen Zhou, Email: 1030435123@qq.com.

Yumei Xue, Email: yumei_xue@163.com.

Xiang Cheng, Email: nathancx@hotmail.com.

Yunlong Xia, Email: yunlong.xia@gmail.com.

Qing Wang, Email: QingWangHust@outlook.com.

Xin Tu, Phone: +8618971338442, Email: xtu@hust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Gungor B, Ekmekci A, Arman A, Ozcan KS, Ucer E, Alper AT, et al. Assessment of Interleukin‐1 Gene Cluster Polymorphisms in Lone Atrial Fibrillation: New Insight into the Role of Inflammation in Atrial Fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013;36:1220–7. doi: 10.1111/pace.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo Y, Lip GY, Apostolakis S. Inflammation in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2263–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishii Y, Schuessler RB, Gaynor SL, Yamada K, Fu AS, Boineau JP, et al. Inflammation of atrium after cardiac surgery is associated with inhomogeneity of atrial conduction and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2005;111:2881–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.475194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedrichs K, Klinke A, Baldus S. Inflammatory pathways underlying atrial fibrillation. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:556–63. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guglin M, Aljayeh M, Saiyad S, Ali R, Curtis AB. Introducing a new entity: chemotherapy-induced arrhythmia. Europace. 2009;11:1579–86. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizos I, Tsiodras S, Rigopoulos AG, Dragomanovits S, Kalogeropoulos AS, Papathanasiou S, et al. Interleukin-2 serum levels variations in recent onset atrial fibrillation are related with cardioversion outcome. Cytokine. 2007;40:157–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hak L, Mysliwska J, Wieckiewicz J, Szyndler K, Siebert J, Rogowski J. Interleukin-2 as a predictor of early postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiopulmonary bypass graft (CABG) J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:327–32. doi: 10.1089/jir.2008.0082.2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olesen MS, Andreasen L, Jabbari J, Refsgaard L, Haunso S, Olesen SP, et al. Very early-onset lone atrial fibrillation patients have a high prevalence of rare variants in genes previously associated with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:246–51. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakim P, Brice N, Thresher R, Lawrence J, Zhang Y, Jackson AP, et al. Scn3b knockout mice exhibit abnormal sino-atrial and cardiac conduction properties. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2010;198:47–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu L, Yong SL, Fan C, Ni Y, Yoo S, Zhang T, et al. Identification of a new co-factor, MOG1, required for the full function of cardiac sodium channel Nav 1.5. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6968–78. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng Z, Zhou J, Hou Y, Liang X, Zhang Z, Xu X, et al. Electrophysiological characteristics of a SCN5A voltage sensors mutation R1629Q associated with Brugada syndrome. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe M, Moon KD, Vacchio MS, Hathcock KS, Hodes RJ. Downmodulation of tumor suppressor p53 by T cell receptor signaling is critical for antigen-specific CD4(+) T cell responses. Immunity. 2014;40:681–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adachi K, Toyota M, Sasaki Y, Yamashita T, Ishida S, Ohe-Toyota M, et al. Identification of SCN3B as a novel p53-inducible proapoptotic gene. Oncogene. 2004;23:7791–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maier SK, Westenbroek RE, McCormick KA, Curtis R, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Distinct subcellular localization of different sodium channel α and β subunits in single ventricular myocytes from mouse heart. Circulation. 2004;109:1421–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121421.61896.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao CM, Xia Q, Bruce IC, Zhang X, Fu C, Chen JZ. Interleukin-2 increases activity of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2 + −ATPase, but decreases its sensitivity to calcium in rat cardiomyocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:572–80. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.048264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu D, Barajas-Martinez H, Burashnikov E, Springer M, Wu Y, Varro A, et al. A mutation in the beta 3 subunit of the cardiac sodium channel associated with Brugada ECG phenotype. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:270–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.829192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valdivia CR, Medeiros-Domingo A, Ye B, Shen WK, Algiers TJ, Ackerman MJ, et al. Loss-of-function mutation of the SCN3B-encoded sodium channel {beta}3 subunit associated with a case of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;86:392–400. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang P, Yang Q, Wu X, Yang Y, Shi L, Wang C, et al. Functional dominant-negative mutation of sodium channel subunit gene SCN3B associated with atrial fibrillation in a Chinese GeneID population. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olesen MS, Jespersen T, Nielsen JB, Liang B, Moller DV, Hedley P, et al. Mutations in sodium channel beta-subunit SCN3B are associated with early-onset lone atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;89:786–93. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hakim P, Brice N, Thresher R, Lawrence J, Zhang Y, Jackson A, et al. Scn3b knockout mice exhibit abnormal sino‐atrial and cardiac conduction properties. Acta Physiol. 2010;198:47–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishikawa T, Takahashi N, Ohno S, Sakurada H, Nakamura K, On YK, et al. Novel SCN3B mutation associated with Brugada syndrome affects intracellular trafficking and function of Nav1.5. Circ J. 2013;77:959–67. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-0995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]