Abstract

A highly convergent, stereocontrolled total synthesis of the architecturally complex marine sponge metabolite (−)-enigmazole A has been achieved. Highlights include an unprecedented late-stage large-fragment Petasis–Ferrier union/rearrangement, a multicomponent Type I Anion Relay Chemistry (ARC) tactic, and a dithiane–epoxide union in conjunction with an oxazole-directed stereoselective reduction.

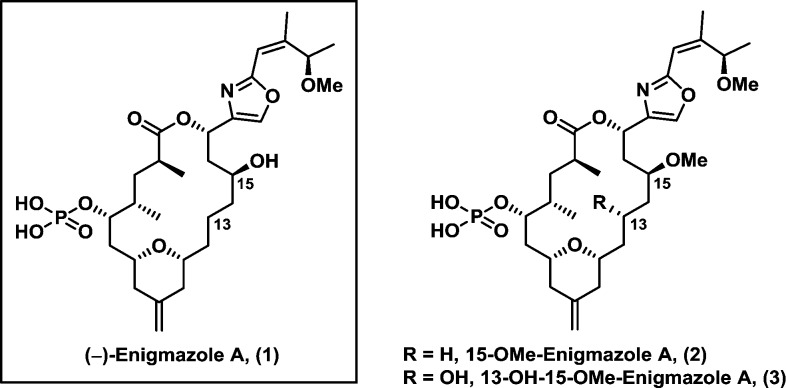

Enigmazole A (1) and the related congeners 2 and 3 constitute the first and to date only family of phosphate-containing marine macrolides (Figure 1).1 Isolated by Gustafson and co-workers in 2006 from marine sponge Cinachyrella enigmatica,2 (−)-enigmazole A (1) was found to be highly cytotoxic against the NCI 60 human tumor cell lines, with a GI50 mean activity of 1.7 μM.1 The potent activity, in conjunction with the complex architecture, the latter secured via a combination of NMR analysis and chemical derivatization,1 has attracted considerable interest in the synthetic community,3 culminating in 2010 with the first total synthesis by the Molinski group.4 Examination of the structure of (−)-enigmazole A (1) led us to a synthetic plan, whereby methods, recently developed in our laboratory including our three-stage Petasis–Ferrier union/rearrangement5 and Type I Anion Relay Chemistry (ARC),6 could be applied.

Figure 1.

(−)-Enigmazole A (1) and related congeners.

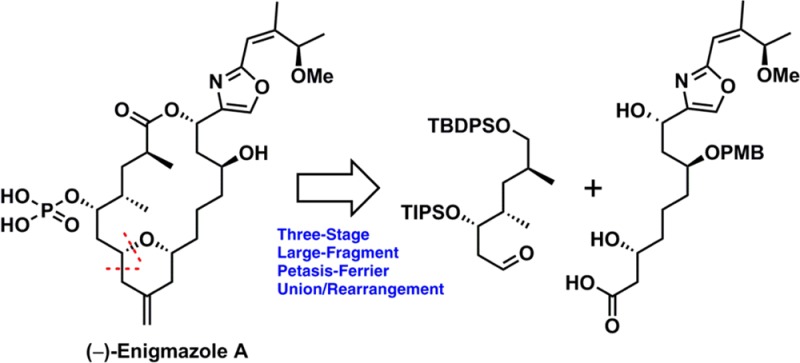

Toward this end, disconnection of (−)-enigmazole A (1) at the macrolactone presented the possibility of a late-stage large-fragment Petasis–Ferrier union/rearrangement to unite the western and eastern hemispheres (4 and 5, respectively) that would generate the entire carbon skeleton with the requisite embedded methylene tetrahydropyran core (Scheme 1). Although the Petasis–Ferrier union/rearrangement has proven to be a powerful tactic during a number of successful total syntheses,7 construction of a late-stage intermediate, employing two large fragments, had not been attempted. In turn the western hemisphere 4 was envisioned to be constructed from the commercially available Roche ester, while elaboration of the eastern hemisphere 5 would derive from the union of dithiane 6 and epoxide 7. Continuing with this analysis, access to the requisite dithiane 6 would entail a Negishi cross-coupling employing commercially available chloride 8 and vinyl iodide 9. The requisite epoxide 7, in turn, would arise via a multicomponent Type I ARC union6 of known fragments 10, 11, and 12.

Scheme 1. Retrosynthetic Analysis.

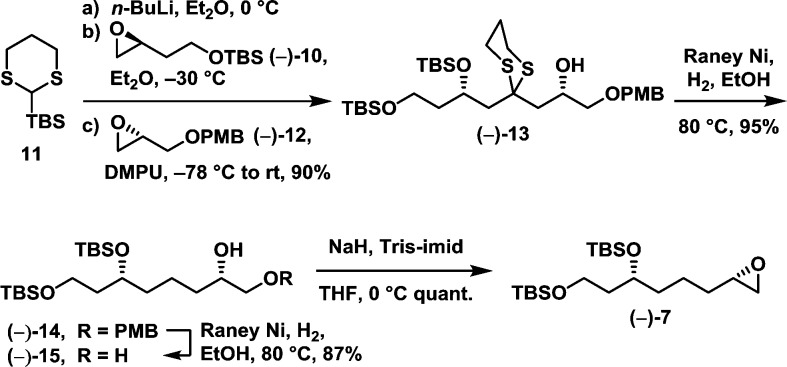

We began the synthesis with epoxide 7 (Scheme 2). Union of enantiopure epoxides (−)-10 and (−)-12 employing dithiane 11 as linchpin furnished (−)-13 in 90% yield as a single diastereomer. The dithiane moiety was next removed under reductive conditions to furnish alcohol (−)-14 in 95% yield,8 which was submitted to Raney nickel reduction to remove the PMB protecting group to furnish diol (−)-15 in 87% yield.9 Epoxide (−)-7 was then generated in near-quantitative yield from diol (−)-15 following the one-step Fraser-Reid protocol.10

Scheme 2.

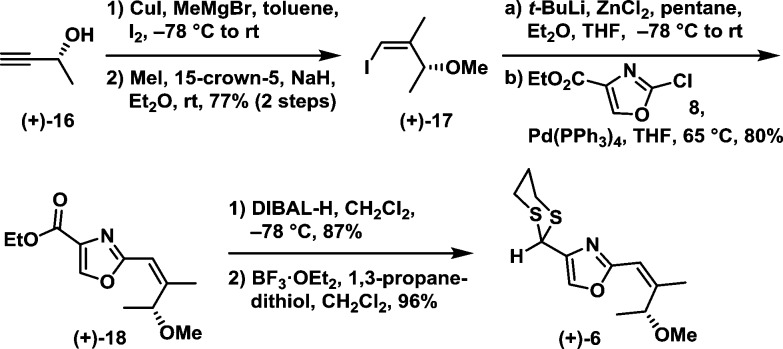

Construction of dithiane 6 began with commercially available (R)-3-butyn-2-ol [(+)-16] (Scheme 3). The desired Z-geometry was established via a copper catalyzed carbometalation/iodination sequence;11 subsequent methylation led to vinyl iodide (+)-17 in 77% yield for the two steps as a single isomer. We next exploited a Negishi cross-coupling protocol to unite the vinyl zincate prepared from (+)-17 with commercially available chloride 8 to furnish oxazolyl ester (+)-18 in 80% yield.12 The resulting ester (+)-18 was then reduced with DIBAL-H to provide the corresponding aldehyde in 87% yield, which was converted to dithiane (+)-6 with BF3·OEt2 and 1,3-propanedithiol; the yield was 96%.

Scheme 3.

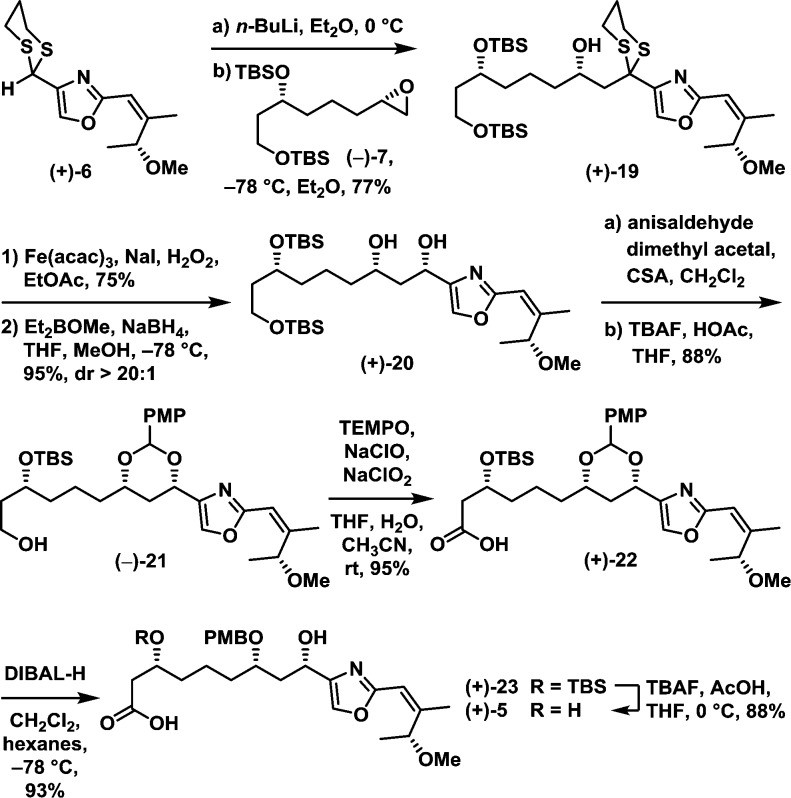

With both dithiane (+)-6 and epoxide (−)-7 in hand, focus turned to construction of the eastern hemisphere 5 (Scheme 4). Their union furnished dithiane (+)-19 in 77% yield after extensive screening of conditions (i.e., solvents, reactant stoichiometry, etc.).13 Hydrolysis of the dithiane was next achieved in 75% yield employing the recently disclosed, environmentally friendly Fe3+ protocol.14 Subsequent exposure of the resulting ketone to a Narasaka–Prasad 1,3-directed reduction provided diol (+)-20 as a single diastereomer in 95% yield.15

Scheme 4.

Continuing with the synthetic venture, protection of diol (+)-20 as the PMP acetal and removal of the primary TBS group then proved possible in a single flask to furnish alcohol (−)-21 in 88% yield. Subsequent TEMPO-mediated oxidation led to carboxylic acid (+)-22 in 95% yield.16 Turning to the next critical step, previous studies during the total synthesis of phorboxazole A had revealed oxazole moieties can form strong complexes with aluminum Lewis acids.7a We therefore reasoned that DIBAL-H would selectively reduce the benzyl acetal functional group of (+)-22 to open the acetal C–O bond proximal to the oxazole, while not reducing carboxylic acid. Pleasingly, treatment of (+)-22 with DIBAL-H in CH2Cl2 furnished alcohol (+)-23 in 93% yield with near-perfect regioselectivity. Subsequent removal of the secondary TBS group of (+)-23 completed construction of the eastern hemisphere (+)-5 in 88% yield.

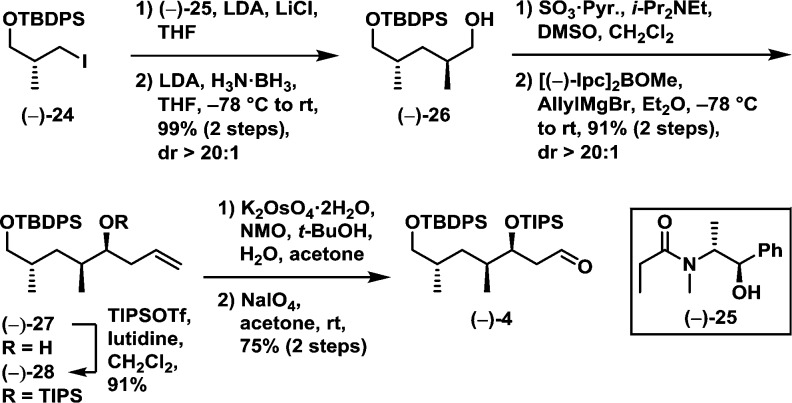

Turning next to the western hemisphere, we began with known iodide (−)-24,17 prepared in three steps from the commercially available (−)-(R)-Roche ester (Scheme 5). Exposure of (−)-24 to a two-step Myers alkylation/reduction sequence,18 employing pseudoephedrine amide (−)-25, led to alcohol (−)-26 in 99% yield for the two steps, as a single diastereomer. Sequential Parikh–Doering oxidation19 and Brown allylation20 then furnished olefin (−)-27 again as a single diastereomer (2 steps, 91% yield). The derived hydroxyl group in (−)-27 was next protected with TIPSOTf to furnish silyl ether (−)-28 in 91% yield. Finally, cleavage of the terminal olefin via a dihydroxylation/oxidation21 sequence led to western hemisphere (−)-4 in 75% yield.

Scheme 5.

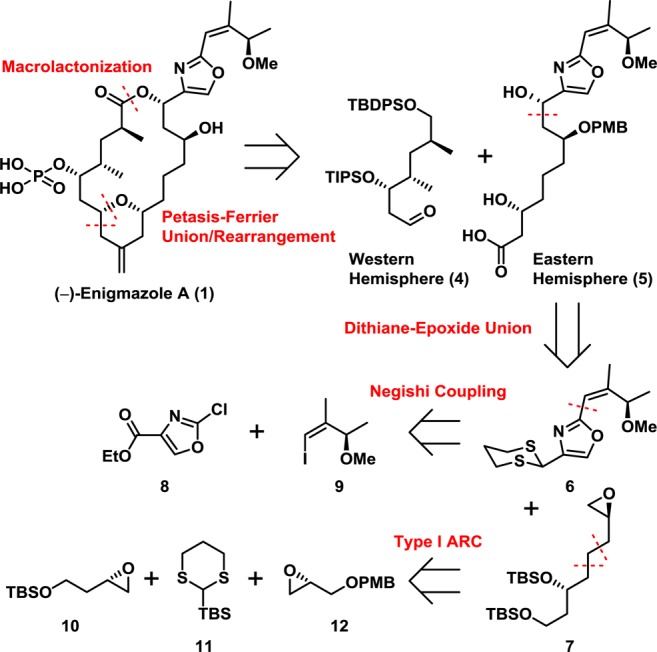

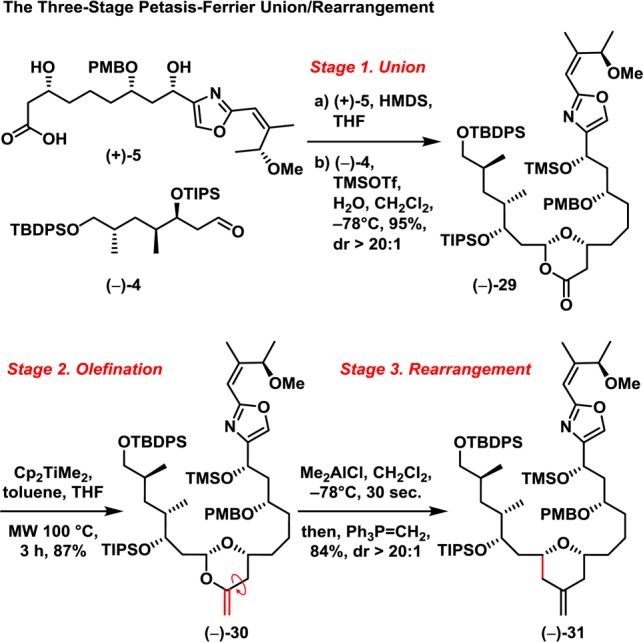

Having constructed both the eastern and western hemispheres [(+)-5 and (−)-4, respectively], we turned to the three-stage Petasis–Ferrier union/rearrangement (Scheme 6).5,7 Although initial attempts at Stage 1, that is union of (+)-5 and (−)-4 utilizing the standard conditions of HMDS/TMSOTf, resulted only in low yields (e.g., <10%), introduction of a trace amount of H2O significantly improved the union to furnish dioxanone (−)-29 in 95% yield. The presumption is that the trace of H2O generates TfOH in situ from TMSOTf, thereby greatly facilitating the formation of the dioxanone.5b Turning to Stage 2, we discovered that the unprecedented use of microwave irradiation during the Petasis olefination led to enol acetal (−)-30 in 87% yield, compared with 40–50% yield utilizing conventional heating.22 Moreover, the microwave conditions significantly decreased the reaction time and minimized the known [2 + 2] side reaction5b between the desired product enol-acetal and the excess Petasis reagent. For Stage 3, at first only inconsistent yields (ca. 20–80%) of the desired tetrahydropyranone resulted employing Me2AlCl, within reaction times ranging between 20 and 35 s, due to an unanticipated Lewis acid promoted intramolecular retro-Michael fragmentation of the tetrahydropyran ring in the desired product.23 Pleasingly, however, success was achieved exploiting an unconventional quenching/olefination tactic, involving addition of methylene ylide (CH2=PPh3) to the rearrangement reaction mixture, directly generating the methylene tetrahydropyran (−)-31. Pleasingly the reaction proceeded consistently in 84% yield to furnish a single diastereomer (−)-31. The late-stage, large-fragment three-stage Petasis–Ferrier union/rearrangement to furnish the entire carbon skeleton of (−)-enigmazole A had thus been achieved in high yield [70%; three steps with a ratio of (+)-5:(−)-4 = 1:1.17] with excellent diastereoselectivity.

Scheme 6.

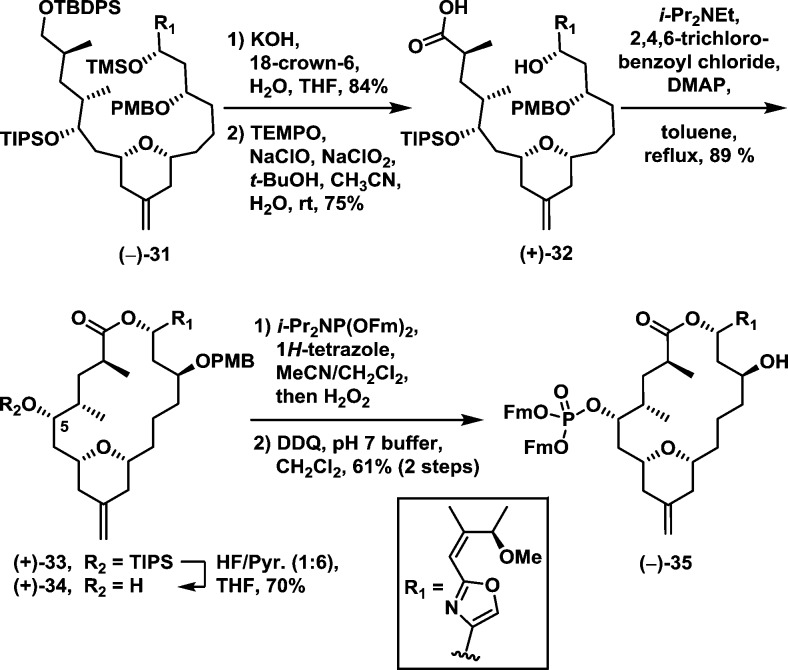

The endgame for (−)-enigmazole A would now require selective deprotections, oxidation to the carboxylic acid, macrolactonization, and introduction of the phosphate moiety (Scheme 7). To this end, the TBDPS and TMS groups in (−)-31 were first removed in a single step utilizing KOH and 18-crown-6 (84% yield). Pleasingly, oxidation of the primary alcohol employing TEMPO then proceeded selectively over the benzylic hydroxyl to furnish macrolactonization precursor (+)-32 in 75% yield.15 Yamaguchi conditions were next employed to generate macrolactone (+)-33; the yield was 89%.24 With macrolide (+)-33 in hand, the TIPS group required removal; initial attempts led to intramolecular transesterification of the derived C5 hydroxyl with the macrolactone carbonyl!25 Eventually, after extensive screening, we discovered that employing the HF–pyridine complex buffered with a large excess of pyridine led to alcohol (+)-34 in satisfactory yield (70%).26 Installation of the 9-fluorenylmethyl (Fm) protected phosphate27 and PMB deprotection28 then smoothly furnished the bis-protected natural product (−)-35 in 61% yield for the two steps.

Scheme 7.

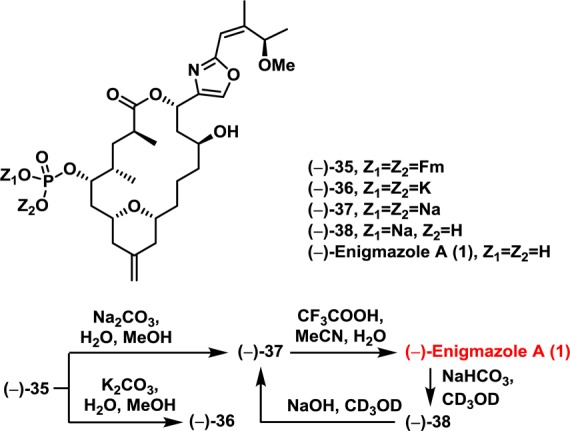

Removal of the Fm protecting groups was initially attempted with K2CO3 (Scheme 8). Interestingly, the 1H NMR spectrum of the resulting dipotassium phosphate (−)-36 displayed multiple inconsistencies compared to that derived from the natural product (e.g., difference >0.11 ppm; see Supporting Information). We reasoned that the inconsistent NMR spectrum could arise from the presence of different counterions (K+ and Na+) based on a suggestion in Molinski’s report of the total synthesis of (−)-enigmazole A.4 We therefore utilized Na2CO3 for Fm deprotection to avoid involvement of K+. The derived disodium phosphate (−)-37, however, displayed the same 1H NMR spectrum as the dipotassium phosphate (−)-36. We next considered that the spectral differences might be due to different levels of proton dissociation of the phosphoric acid. The synthesis of all three forms of the natural product was therefore carried out. Purification of the disodium phosphate (−)-37, employing C18 RP-HPLC buffered with 0.1% TFA, led to the formation of phosphoric acid (−)-1 [95% yield from (−)-35]. Subsequent treatment of (−)-1 with saturated NaHCO3 in CD3OD furnished the monosodium phosphate (−)-38, which could be converted to disodium phosphate (−)-37 via addition of NaOH in CD3OD. Interestingly, the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of all three phosphate forms of (−)-enigmazole A displayed considerable differences with each other. Pleasingly, the synthetic monosodium phosphate (−)-38 displayed spectral properties in excellent agreement with those derived from both the natural product reported by Gustafson1 and the Molinski synthetic sample4 [i.e., 1H, 13C, 31P NMR (500, 125, 202 MHz, respectively), HRMS parent ion identification, UV and chiroptic properties].

Scheme 8.

In summary, a highly convergent, stereocontrolled total synthesis of (−)-enigmazole A (1), along with the mono- and disodium phosphate salts, has been achieved in 4.4% overall yield with a longest linear sequence of 22 steps from commercially available (R)-3-butyn-2-ol. The cornerstone transformation of the synthesis comprised a late-stage large-fragment three-stage Petasis–Ferrier union/rearrangement. Importantly, the spectral properties of all three phosphate forms of the natural product are now available for the first time. Studies toward the synthesis of other enigmazoles continue in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (National Cancer Institute) through CA-19033. We also thank Drs. George Furst and Jun Gu, and Dr. Rakesh Kohli at the University of Pennsylvania for assistance in obtaining NMR and high-resolution mass spectra, respectively.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5b11540.

Experimental procedures, as well as spectroscopic and analytical data for all new compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Oku N.; Takada K.; Fuller R. W.; Wilson J. A.; Peach M. L.; Pannell L. K.; McMahon J. B.; Gustafson K. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10278. 10.1021/ja1016766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oku N.; Gustafson K. R.; Fuller R. W.; Wilson J. A.; Pannell L. K.; McMahon J. B. Symposium on the Chemistry of Natural Products 2006, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Synthetic Studies:; a Persich P.; Llaveria J.; Lhermet R.; de Haro T.; Stade R.; Kondoh A.; Fürstner A. Chem. - Eur. J. 2013, 19, 13047. 10.1002/chem.201302320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kishi T.; Fujisawa Y.; Takamura H.; Kadota I. Heterocycles 2014, 89, 515. 10.3987/COM-13-12905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skepper C. K.; Quach T.; Molinski T. F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10286. 10.1021/ja1016975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Petasis N. A.; Lu S.-P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 141. 10.1016/0040-4039(95)02114-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Smith A. B.; Fox R. J.; Razler T. M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 675. 10.1021/ar700234r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Smith A. B.; Boldi A. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 6925. 10.1021/ja970371o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Smith A. B.; Pitram S. M.; Boldi A. M.; Gaunt M. J.; Sfouggatakis C.; Moser W. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 14435. 10.1021/ja0376238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Smith A. B.; Xian M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 66. 10.1021/ja057059w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Smith A. B. III; Wuest W. M. Chem. Commun. 2008, 5883. 10.1039/b810394a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Smith A. B.; Minbiole K. P.; Verhoest P. R.; Schelhaas M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 10942. 10.1021/ja011604l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Smith A. B.; Safonov I. G.; Corbett R. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 11102. 10.1021/ja020635t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Smith A. B.; Zhu W.; Shirakami S.; Sfouggatakis C.; Doughty V. A.; Bennett C. S.; Sakamoto Y. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 761. 10.1021/ol034037a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Smith A. B.; Mesaros E. F.; Meyer E. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 5292. 10.1021/ja060369+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Smith A. B.; Simov V. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 3315. 10.1021/ol0611752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Smith A. B.; Basu K.; Bosanac T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 14872. 10.1021/ja077569l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozingo R.; Wolf D. E.; Harris S. A.; Folkers K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1943, 65, 1013. 10.1021/ja01246a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- When attempts were made to reduce directly (–)-13 to (–)-15 utilizing Raney Ni/H2, only a small amount of desired product was observed

- Hicks D. R.; Fraser-Reid B. Synthesis 1974, 1974, 203. 10.1055/s-1974-23284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z.; Ma S. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 2655. 10.1021/jo0524021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A. O.; Okukado N.; Negishi E.-i. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1977, 683. 10.1039/c39770000683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Molinski et al. disclosed a related Negishi coupling protocol for (+)-18 in their synthesis of (−)-enimgzole A, ref (4).

- Seebach D.; Corey E. J. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 231. 10.1021/jo00890a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirihara M.; Suzuki S.; Ishizuka Y.; Yamazaki K.; Matsushima R.; Suzuki T.; Iwai T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 5477. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.07.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narasaka K.; Pai F.-C. Tetrahedron 1984, 40, 2233. 10.1016/0040-4020(84)80006-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota M.; Tamura N.; Saito T.; Isogai A. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 78, 330. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2009.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Wu J.; Luo J.; Dai W.-M. Chem. - Eur. J. 2010, 16, 11530. 10.1002/chem.201001794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers A. G.; Yang B. H.; Chen H.; McKinstry L.; Kopecky D. J.; Gleason J. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 6496. 10.1021/ja970402f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh J. R.; Doering W. v. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 5505. 10.1021/ja00997a067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H. C.; Desai M. C.; Jadhav P. K. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 5065. 10.1021/jo00147a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Pappo R.; Allen D. S. Jr.; Lemieux R. U.; Johnson W. S. J. Org. Chem. 1956, 21, 478. 10.1021/jo01110a606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b VanRheenen V.; Kelly R. C.; Cha D. Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 1973. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)78093-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petasis N. A.; Bzowej E. I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 6392. 10.1021/ja00173a035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NMR studies of the major byproduct clearly demonstrated an α,β-unsaturated ketone structure.

- Inanaga J.; Hirata K.; Saeki H.; Katsuki T.; Yamaguchi M. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1979, 52, 1989. 10.1246/bcsj.52.1989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- See Supporting Information for the spectral data for a δ-lactone which we envisioned arising via an intramolecular transesterification after formation of desired alcohol (+)-34.

- See similar conditions:Carreira E. M.; Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 10825. 10.1021/ja00102a074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann E.; Engels J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986, 27, 1023. 10.1016/S0040-4039(86)80038-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horita K.; Yoshioka T.; Tanaka T.; Oikawa Y.; Yonemitsu O. Tetrahedron 1986, 42, 3021. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90593-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.