Abstract

BACKGROUND

Relatively high plasma levels of soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) have been associated with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and poor clinical outcomes in patients with various conditions. It is unknown whether elevated suPAR levels in patients with normal kidney function are associated with future decline in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and with incident chronic kidney disease.

METHODS

We measured plasma suPAR levels in 3683 persons enrolled in the Emory Cardiovascular Biobank (mean age, 63 years; 65% men; median suPAR level, 3040 pg per milliliter) and determined renal function at enrollment and at subsequent visits in 2292 persons. The relationship between suPAR levels and the eGFR at baseline, the change in the eGFR over time, and the development of chronic kidney disease (eGFR <60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 of body-surface area) were analyzed with the use of linear mixed models and Cox regression after adjustment for demographic and clinical variables.

RESULTS

A higher suPAR level at baseline was associated with a greater decline in the eGFR during follow-up; the annual change in the eGFR was −0.9 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 among participants in the lowest quartile of suPAR levels as compared with −4.2 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 among participants in the highest quartile (P<0.001). The 921 participants with a normal eGFR (≥90 ml per minute per 1.73 m2) at baseline had the largest suPAR-related decline in the eGFR. In 1335 participants with a baseline eGFR of at least 60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2, the risk of progression to chronic kidney disease in the highest quartile of suPAR levels was 3.13 times as high (95% confidence interval, 2.11 to 4.65) as that in the lowest quartile.

CONCLUSIONS

An elevated level of suPAR was independently associated with incident chronic kidney disease and an accelerated decline in the eGFR in the groups studied. (Funded by the Abraham J. and Phyllis Katz Foundation and others.)

Chronic kidney disease and progressive loss of kidney function constitute a major public health problem affecting 11% of the U.S. population.1 Patients with chronic kidney disease are at high risk for cardiovascular disease and death.2 It is thus important to identify patients at high risk for chronic kidney disease and to treat underlying disease processes that drive kidney injury.3 In clinical practice, methods of screening for kidney disease are limited to measurement of urinary protein excretion and calculation of the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Proteinuria and a decline in the eGFR are relatively insensitive indexes of early injury and have limited usefulness in mass screening for chronic kidney disease.3–5 Hence, more sensitive biomarkers are required to identify at-risk patients earlier in the disease process in order to develop and study interventions aimed at preventing the progression to chronic kidney disease.

Soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) is the circulating form of a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol–anchored three-domain membrane protein that is expressed on a variety of cells, including immunologically active cells, endothelial cells, and podocytes.6–8 Both the circulating and membrane-bound forms are directly involved in the regulation of cell adhesion and migration through binding of integrins.6 The circulating form is produced by cleavage of membrane-bound urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor and is readily detected in plasma, serum, urine, and other bodily fluids.9–11 Elevated suPAR levels have been associated with poor outcomes in various patient populations.12–20 In addition, suPAR has been implicated in the pathogenesis of kidney disease, specifically focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and diabetic nephropathy, through interference with podocyte migration and apoptosis.7,13,21,22 Although these findings are still under investigation,23 they suggest a possible broader role of suPAR in kidney disease. Therefore, in a large, prospective cohort study involving patients with cardiovascular disease, we tested the hypothesis that plasma suPAR levels are associated with new-onset chronic kidney disease.

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION

Study participants were recruited from the Emory Cardiovascular Biobank, a prospective registry of patients undergoing cardiac catheterization at three Emory Healthcare sites in Atlanta between 2003 and 2009.20 Patients were excluded if they had congenital heart disease, severe valvular heart disease, severe anemia, a recent blood transfusion, myocarditis, or a history of active inflammatory disease or cancer. Persons 20 to 90 years of age were interviewed and data were collected on demographic characteristics, medical history, medication use, and behavioral habits. The prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease and kidney disease was determined by the examining physician. Medical records were reviewed to confirm self-reported medical history.

STUDY DESIGN

We examined the relationship between baseline suPAR levels and kidney function (as determined by the eGFR and semiquantitative assessment of urinary protein excretion) in 3683 people. To investigate the association between suPAR levels and the change in the eGFR during follow-up, at least one post-baseline measurement of the eGFR (median, seven measurements) was obtained in 2292 participants (62%) during a median follow-up period of 1337 days. In addition, the relationship between suPAR levels and incident chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 of body-surface area beyond 30 days, was determined in 1335 persons who had a baseline eGFR of at least 60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org).24

SAMPLE COLLECTION AND MEASUREMENT OF SUPAR AND HIGH-SENSITIVITY C-REACTIVE PROTEIN

Fasting arterial blood samples were obtained, and serum and plasma were stored at −80°C for a mean duration of 4.9 years. Serum concentrations of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) were determined with the use of a particle- enhanced immunoturbidimetry assay (FirstMark, a division of GenWay Biotech) that has a lower limit of detection of 0.03 mg per liter.25 Plasma levels of suPAR were measured with the suPAR-nostic kit (ViroGates), which has a lower limit of detection of 100 pg per milliliter; according to the manufacturer, the intra-assay variation is 2.75% and the interassay variation is 9.17%.

MEASURES OF KIDNEY FUNCTION

Serum creatinine measurements at enrollment and all subsequent measurements obtained during routine follow-up clinic visits or hospitalizations within the Emory Healthcare system were recorded. The eGFR was calculated by means of the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation.26 Semiquantitative measurements of protein excretion in random urine samples by dipstick testing were available for 2292 participants: in the case of 1477 participants, measurements were obtained at the time of enrollment; an additional 815 participants with subsequent dipstick tests showing trace or no proteinuria were assumed to have had trace or no proteinuria at enrollment.

STUDY OVERSIGHT

The study was approved by the institutional review board at Emory University. All the participants provided written informed consent at the time of enrollment. The suPAR sample kits were donated by ViroGates. High-sensitivity CRP sample measurements were conducted by FirstMark, a division of GenWay Biotech. Neither ViroGates nor FirstMark had any role in data analysis or manuscript preparation.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations or as medians and inter-quartile ranges, and categorical variables are presented as proportions. We used independent-sample t-tests to compare continuous variables and chi-square tests to compare categorical variables. Proteinuria status was dichotomized as no proteinuria (in 2188 participants), defined by negative or trace results for protein on urine dip-stick testing, or proteinuria (in 104 participants), defined by a result of 1+ or higher for protein. All eGFR values of more than 120 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 (<1% of measurements) were set at 120 ml per minute per 1.73 m2. Both suPAR and eGFR values were logarithmically transformed on a natural log scale before analyses. All multivariable analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race (blacks vs. others), body-mass index, proteinuria (1+ or higher vs. negative or trace result for protein), high-sensitivity CRP level, use or nonuse of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors, and presence or absence of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, a history of smoking, and a history of myocardial infarction.

The association between baseline suPAR levels and the change in the eGFR over time was investigated in 2292 participants who had follow-up eGFR measurements. We used linear mixed-effects modeling with a random participant-specific intercept and a random time effect, by regressing log(eGFR) against log(suPAR), follow-up time (years since baseline), log(suPAR) × time, and baseline eGFR, in addition to the aforementioned covariates. Three-way interaction terms were incorporated into the model to determine whether eGFR, race, and the presence or absence of diabetes modified the association between suPAR levels and the change in the eGFR. The estimated decline in the eGFR in each subgroup was derived accordingly.

Among the 1335 participants who had an eGFR of more than 60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 at baseline, we evaluated the rate of progression to clinical chronic kidney disease (eGFR <60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2) according to quartiles of suPAR levels, using the log-rank test and a Cox proportional-hazards model with adjustment for the aforementioned covariates. In addition, we calculated the C-statistic and category-free net reclassification improvement for risk discrimination.27

To validate our results, we repeated the analysis after randomly dividing the entire study sample into two groups; in addition, we performed the analysis in a subgroup of 347 patients enrolled in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) (see the Supplementary Appendix).28,29 Two-tailed P values of less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed with the use of SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE EMORY CARDIOVASCULAR BIOBANK COHORT

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the total cohort and of the cohort dichotomized according to median suPAR level (3040 pg per milliliter [interquartile range, 2373 to 4019]) are shown in Table 1. Elevated plasma suPAR levels at baseline were independently associated with female sex, a history of smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, proteinuria, hyperlipidemia, a history of myocardial infarction, high-sensitivity CRP levels, and eGFR (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Emory Cardiovascular Biobank Cohort.*

| Characteristic | Entire Cohort (N = 3683) | suPAR <3040 pg/ml (N = 1839) | suPAR ≥3040 pg/ml (N = 1844) | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age — yr | 63±12 | 60±11 | 65±12 | <0.001 |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 2404 (65) | 1324 (72) | 1080 (59) | <0.001 |

| Black race — no. (%)‡ | 654 (18) | 334 (18) | 320 (17) | 0.55 |

| Body-mass index§ | 30±6 | 29±6 | 30±7 | 0.07 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| History of smoking — no./total no. (%) | 2063/3556 (58) | 968/1722 (56) | 1095/1784 (61) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension — no./total no. (%) | 2601/3628 (72) | 1220/1816 (67) | 1381/1812 (76) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus — no./total no. (%) | 1168/3650 (32) | 423/1825 (23) | 745/1825 (41) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia — no./total no. (%) | 2494/3627 (69) | 1220/1816 (67) | 1274/1811 (70) | 0.06 |

| History of myocardial infarction — no./total no. (%) | 1296/3622 (36) | 568/1805 (31) | 728/1817 (40) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease — no./total no. (%)¶ | 2279/3442 (66) | 1092/1731 (63) | 1187/1711 (69) | <0.001 |

| Renin–angiotensin system antagonists — no./total no. (%) | 2046/3251 (63) | 998/1613 (62) | 1048/1638 (64) | 0.09 |

| Urine dipstick result ≥1+ for protein — no./total no. (%) | 137/1477 (9) | 32/679 (5) | 105/798 (13) | <0.001 |

| eGFR — ml/min/1.73 m2 of body-surface area | 73±23 | 81±18 | 64±24 | <0.001 |

| High-sensitivity CRP — ng/ml | 6.85±12.86 | 5.23±10.83 | 8.46±14.42 | <0.001 |

| suPAR — pg/ml | 3493±1938 | 2330±452 | 4654±2145 | <0.001 |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. CRP denotes C-reactive protein, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, and suPAR soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor.

The P value is for the comparison between patients with a suPAR level of at least 3040 pg per milliliter and those with a level of less than 3040 pg per milliliter.

Race was self-reported.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Coronary artery disease was defined as the presence of an obstructive lesion (≥50% stenosis of the artery diameter) in any of the major vessels on a coronary angiogram.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EGFR, PROTEINURIA, AND SUPAR LEVELS AT BASELINE

A lower eGFR at baseline was independently associated with increasing age, male sex, black race, higher body-mass index, a history of smoking, hypertension, proteinuria, nonuse of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors, and elevated suPAR levels (Table S1 and Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). The correlation between suPAR levels and the eGFR varied according to the baseline eGFR (P<0.001 for interaction) and was weak among participants with an eGFR of at least 90 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 (r=−0.07, P = 0.04) (Fig. S2C and S2D in the Supplementary Appendix). More than 30% of the participants with an eGFR of at least 90 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 had a suPAR level of 3040 pg per milliliter or higher (Fig. S2B in the Supplementary Appendix).

In addition, we found a positive correlation between proteinuria and suPAR levels (r = 0.22, P<0.001) that was independent of the eGFR (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). More than half the participants without proteinuria (52%) had suPAR levels of 3040 pg per milliliter or higher (Fig. S3B in the Supplementary Appendix).

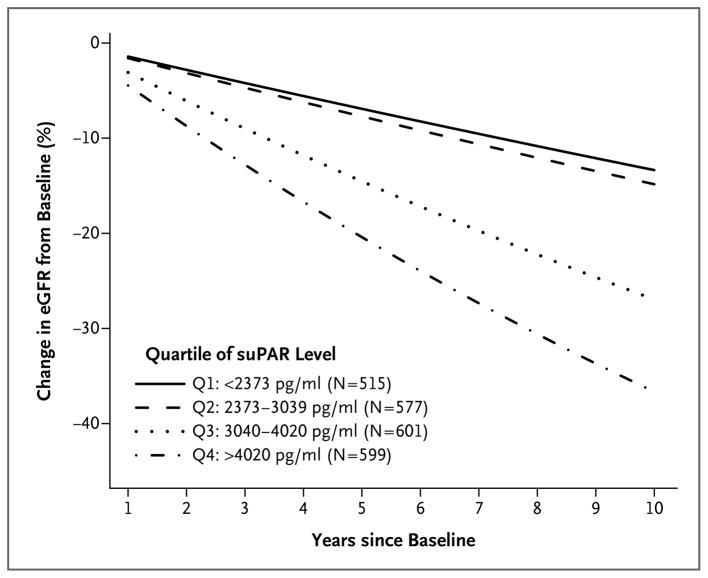

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SUPAR LEVELS AND CHANGE IN EGFR DURING FOLLOW-UP

We determined the relationship between the plasma suPAR level at baseline and the change in the eGFR among 2292 participants (62%) who had follow-up eGFR measurements. The decline in the eGFR was greater in persons with higher baseline suPAR levels (Fig. 1, and Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Participants in the two higher quartiles of suPAR levels (≥3040 pg per milliliter) had a significantly greater decline in the eGFR than did those in the two lower quartiles (<3040 pg per milliliter) after multivariable adjustment (Fig. 1). Over a period of 5 years, the decline in the eGFR was 7.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.0 to 9.5) in the two lower quartiles, as compared with 14.5% (95% CI, 10.7 to 18.2) in the third quartile and 20.4% (95% CI, 12.9 to 27.3) in the fourth quartile.

Figure 1. Levels of suPAR and Decline in the eGFR.

Shown are data from a statistical model examining the percent change in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) over time in 2292 persons, with data stratified according to quartile (Q1 through Q4) of the soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) level at baseline. The annual change in the eGFR was −0.9 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 in Q1 as compared with −4.2 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 in Q4 (P<0.001). Q4 had a significantly higher rate of decline than both Q1 and Q2 (P<0.001 for both comparisons); Q3 also had a significantly higher rate of decline than both Q1 and Q2 (P<0.001 for both comparisons). There was not a significant difference in the rate of decline between Q1 and Q2 (P = 0.91) or between Q3 and Q4 (P = 0.08).

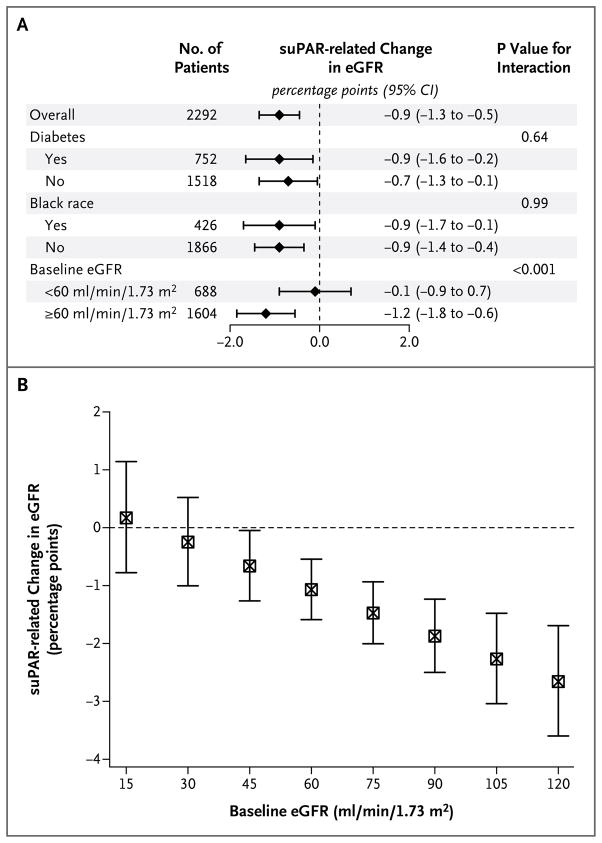

We performed sensitivity analyses to determine whether race, the presence of diabetes, the presence of proteinuria, baseline eGFR values, or baseline high-sensitivity CRP values influenced the relationship between the suPAR level and the change in the eGFR. The suPAR level remained independently associated with eGFR decline regardless of race or the presence of diabetes (Fig. 2A). However, the interaction with the baseline eGFR was significant (P<0.001): there was no relationship between suPAR levels and eGFR decline among participants with a baseline eGFR of less than 60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2, whereas the suPAR level was associated with eGFR change among those with an eGFR of at least 60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 at baseline (Fig. 2A). The 921 participants with a normal eGFR (≥90 ml per minute per 1.73 m2) at baseline had the largest suPAR-related decline in the eGFR (P<0.001 for interaction) (Fig. 2B). We did not find a significant interaction with the presence of proteinuria at baseline (P = 0.29) or baseline serum high-sensitivity CRP levels (P = 0.89).

Figure 2. The suPAR-Related Decline in the eGFR, According to Subgroup.

Panel A shows the suPAR-related change in the eGFR per year during follow-up, stratified according to presence or absence of diabetes, black or nonblack race (race was self-reported), and baseline eGFR (<60 or ≥60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 of body-surface area). Information on diabetes status was missing for 22 patients. CI denotes confidence interval. Panel B shows the suPAR-related change in the eGFR per year, stratified according to baseline eGFR. Patients with an eGFR in the normal range (90 to 120 ml per minute per 1.73 m2) had the largest suPAR-related decline in the eGFR. I bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

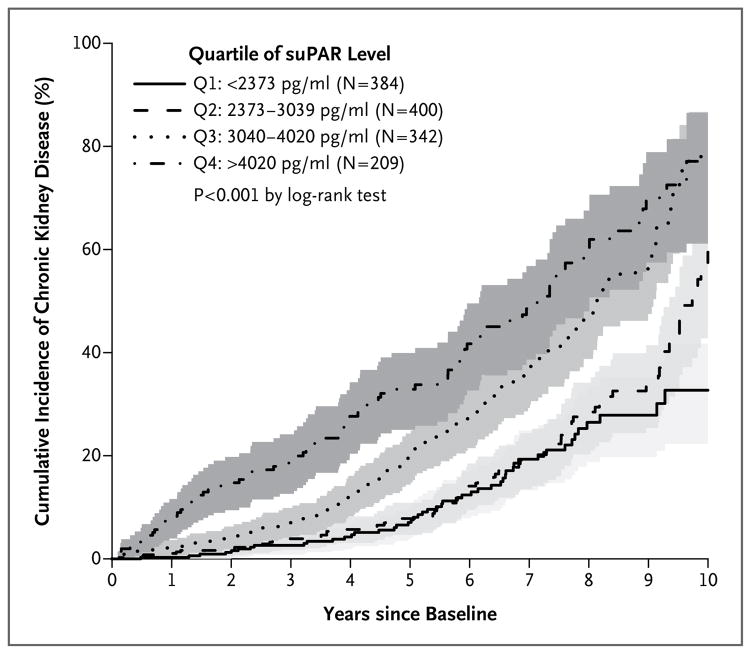

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SUPAR LEVELS AND INCIDENT CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE

Among 1335 participants who had an eGFR of at least 60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 at baseline, we determined whether baseline suPAR level was associated with progression to clinical chronic kidney disease (defined as an eGFR <60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2). Chronic kidney disease developed in 320 participants (24%) during follow-up. Incident chronic kidney disease was independently associated with age, baseline eGFR, hypertension, and plasma suPAR level (Table 2). A higher suPAR level at baseline was associated with a significantly greater incidence of chronic kidney disease (P<0.001) (Fig. 3, and Fig. S4 in the Supplementary Appendix). Participants with a suPAR level in the third quartile had a risk of incident chronic kidney disease that was twice that of participants in the first (lowest) quartile, and participants in the fourth quartile had a risk that was three times that of participants in the first quartile (Table 2). The rate of chronic kidney disease was 7% at 1 year and 41% at 5 years among participants with a suPAR level of at least 3040 ng per milliliter (third and fourth quartiles), as compared with 1% and 12%, respectively, among participants with a suPAR level of less than 3040 ng per milliliter (first and second quartiles).

Table 2.

Baseline Factors and Their Association with Incident Chronic Kidney Disease.*

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline eGFR, per increase of 1 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) | <0.001 |

| Age, per increase of 1 yr | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.05 |

| Female sex | 0.94 (0.72–1.23) | 0.66 |

| Black race | 1.23 (0.90–1.70) | 0.20 |

| Body-mass index, per increase of 1 unit | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.39 |

| History of smoking | 1.16 (0.91–1.47) | 0.24 |

| Hypertension | 1.34 (1.00–1.78) | 0.05 |

| Diabetes | 1.18 (0.91–1.52) | 0.22 |

| Proteinuria | 1.55 (0.86–2.81) | 0.15 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.03 (0.78–1.35) | 0.86 |

| History of myocardial infarction | 0.96 (0.76–1.23) | 0.76 |

| Use of renin–angiotensin system antagonist | 0.84 (0.65–1.09) | 0.18 |

| High-sensitivity CRP, ≥2.8 vs. <2.8 ng/ml | 1.08 (0.84–1.38) | 0.55 |

| suPAR | ||

| Per quartile increment | 1.40 (1.26–1.55) | <0.001 |

| ≥3040 vs. <3040 pg/ml | 1.97 (1.53–2.54) | <0.001 |

| Quartile 2 vs. quartile 1 | 1.18 (0.81–1.73) | 0.39 |

| Quartile 3 vs. quartile 1 | 2.00 (1.38–2.89) | <0.001 |

| Quartile 4 vs. quartile 1 | 3.13 (2.11–4.65) | <0.001 |

| Quartile 4 vs. quartile 3 | 1.51 (1.11–2.06) | 0.01 |

Hazard ratios were calculated with the use of a multivariable model incorporating all covariates listed in the table. Except for baseline eGFR, age, body-mass index, high-sensitivity CRP, and suPAR, all variables were dichotomous (i.e., presence vs. absence). The effect of suPAR is reported as a continuous variable, dichotomized according to the median value (≥3040 vs. <3040 pg per milliliter) and according to quartile. CI denotes confidence interval.

Figure 3. Levels of suPAR and Incident Chronic Kidney Disease.

Kaplan–Meier curves show the cumulative incidence of chronic kidney disease, defined as an eGFR of less than 60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2, among the 1335 participants who had a baseline eGFR of at least 60 ml per minute per 1.73 m2, stratified according to quartile of suPAR level. The shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals. The P value is the result of the log-rank test for the overall comparison among the groups.

Even after excluding the 208 participants with potential acute kidney injury (defined as a 50% decline in the eGFR as compared with the prior eGFR measurement regardless of time), we found that both the third and fourth quartiles of suPAR level remained associated with incident chronic kidney disease (odds ratio for the third quartile as compared with the first quartile, 2.20 [95% CI, 1.33 to 3.06], and odds ratio for the fourth quartile as compared with the first quartile, 2.93 [95% CI, 1.86 to 4.62]). These findings suggest that suPAR is associated with a progressive decline in kidney function.

Risk Discrimination

We tested the incremental value of adding the suPAR level to a statistical model with traditional risk factors in predicting incident chronic kidney disease. The C-statistic for incident chronic kidney disease at both 1 year and 5 years of follow-up increased with the addition of suPAR quartile groups (Δ = 0.08 [95% CI, 0.01 to 0.15] and Δ = 0.03 [95% CI, 0.01 to 0.06], respectively) (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). The continuous net-reclassification-improvement metric showed substantial reclassification of participant risk by the addition of the suPAR level to the model at both 1 year (0.40 [95% CI, 0.15 to 0.53]) and 5 years (0.34 [95% CI, 0.19 to 0.41]) (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). Addition of the suPAR level to the model with conventional risk factors was associated with a change in R2 of 0.33, a change that was larger than that with all other variables combined (Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Validation Analyses

We repeated the longitudinal analyses in two randomly selected subgroups of the Emory Cardiovascular Biobank cohort and also in a subgroup of women in the WIHS cohort. In both randomly selected subgroups of the Emory Cardiovascular Biobank, an elevated suPAR level at baseline was associated with eGFR decline during follow-up and with incident chronic kidney disease, findings consistent with those of the primary analysis (Tables S2 and S5 in the Supplementary Appendix).

We then measured suPAR using a different assay (Quantikine Human uPAR Immunoassay [R&D Systems]) in a separate replication cohort of 347 women enrolled in the WIHS (mean age, 40 years; 62% of black race; 39% with positivity for the human immunodeficiency virus) (Table S6 in the Supplementary Appendix) for whom follow-up data on the eGFR were available (median, 26 measurements over a period of ≥10 years). Over a period of 5 years, the 175 women with a baseline suPAR level of at least 3000 pg per milliliter had a decline of 3.0 percentage points in the eGFR (95% CI, 1.6 to 4.4), whereas the 172 women with a suPAR level of less than 3000 pg per milliliter had a decline of 0.7 percentage points (95% CI, 0.6 to 2.0) (Table S7 and Fig. S5 in the Supplementary Appendix).

DISCUSSION

In this prospective cohort of adults with cardiovascular disease, we identified an association between elevated plasma suPAR levels and both a decline in the eGFR and the development of chronic kidney disease. This association was observed in patients with normal baseline kidney function and was independent of conventional risk factors for kidney disease and cardiovascular disease, including baseline eGFR, age, race, diabetes, hypertension, and high-sensitivity CRP levels. Inclusion of the suPAR level in a prediction model significantly improved discrimination of future risk of chronic kidney disease over a standard clinical model, as evidenced by significant improvement in the C-statistic and the net reclassification metric. The risk reclassification was greater than that with well-established biomarkers such as high-sensitivity CRP and B-type natriuretic peptide, which are used to predict cardiovascular events and heart failure, respectively.30 We also found that suPAR remained associated with a decline in renal function among younger persons, who have a significantly lower burden of risk factors for cardiovascular disease, which suggests that the effect of suPAR is truly independent of traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease. The estimated annual eGFR decline in the WIHS subgroup was, not surprisingly, lower than that observed in the Emory Cardiovascular Biobank cohort (decline of 3% vs. 20% over a period of 5 years), probably owing to the older age and greater burden of risk factors for cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in the Bio-bank cohort.

High suPAR levels have typically been attributed to a state of inflammation or decreased renal clearance.15,23 Although we found a negative correlation between plasma suPAR level and the baseline eGFR, this association was weak at a baseline eGFR of more than 90 ml per minute per 1.73 m2, with a substantial proportion (>30%) of participants with normal kidney function having suPAR levels of 3040 pg per milliliter or higher in the absence of sepsis or cancer. Thus, elevated suPAR levels are unlikely to be simply the result of a decrease in renal clearance and may be related to the underlying pathogenic mechanisms initiating kidney disease.

Evidence that suPAR plays a pathogenic role in kidney disease has emerged mainly from studies of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in which suPAR was shown to activate αVβ3, integrin on podocytes, leading to effacement of foot processes and proteinuria.21 Elevated suPAR levels have also been associated with diabetic nephropathy and with progression of lupus nephritis.12,29 In animal models of diabetic kidney disease, blockade of β3 integrin with the use of a monoclonal antibody was protective.12,31,32 In addition to its role in the activation of αVβ3 integrin on podocytes, suPAR may mediate kidney injury through several molecular mechanisms. For example, CD40 autoantibodies have been implicated in modifying the effect of suPAR in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis,33 whereas levels of acid sphingomyelinase-like phosphodiesterase 3b have been implicated in modulating the effect of suPAR in diabetic nephropathy.13 Thus, suPAR may interact with other molecules to induce podocyte dysfunction and mediate progression to chronic kidney disease in a broad range of conditions.

Alternatively, given the stability of the suPAR protein both in vivo and in vitro,34 it is possible that suPAR acts as a marker of underlying low-grade inflammatory processes that lead to disease. That said, in our cohort, the level of high-sensitivity CRP, a well-accepted marker of chronic inflammation, was associated with cardiovascular events (similarly to the suPAR level) but not with a decline in kidney function, findings that suggest that the role of suPAR in chronic kidney disease goes beyond inflammatory processes.

Early identification and management of chronic kidney disease is highly cost-effective and can reduce the risk of progression to chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease by up to 50%.35 Currently, proteinuria is considered to be the most sensitive marker for progression of chronic kidney disease in clinical practice, especially when there is also a decline in the eGFR. However, there are considerable shortfalls in the diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity of these variables. Although multiple biomarkers are currently being explored as predictors of progression of kidney disease and associated risk of accelerated cardiovascular disease, none have been shown to predict the incidence of chronic kidney disease in patients with a normal eGFR.36

Our results suggest that suPAR meets critical requirements for a biomarker of chronic kidney disease. First, suPAR levels are relatively stable in plasma,34 and elevated levels are associated with incident chronic kidney disease before any decline in the eGFR occurs. Second, it adds prognostic value in all patients and in the subgroups of patients who have diabetes or hypertension, the two most prevalent diseases associated with chronic kidney disease in the United States. Third, it is associated with chronic kidney disease in both whites and blacks, despite the marked differences between these two racial groups in the likelihood of chronic kidney disease. Fourth, measurement of suPAR may allow for more accurate stratification of patients early in their disease course, enabling rational targeting of preventive health resources and enrollment into potential trials of new renoprotective therapies. We and others have found that elevated suPAR levels are associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events in people with or without chronic kidney disease.20,37

Our conclusions are strengthened by the large cohort size and its heterogeneity, which is reflective of a real-world clinical setting, and by independent replication. Patients with confounding disorders such as active infection and cancer were systematically excluded, and the use of inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin system was carefully documented. The predictors of chronic kidney disease in this cohort are consistent with those in previous reports, thus reinforcing the validity of our conclusions.38 Our findings regarding proteinuria have limitations given the small number of patients with proteinuria and the use of dipstick testing of randomly collected urine samples (Tables S8 and S9 in the Supplementary Appendix).

In conclusion, we found that elevated plasma suPAR levels were associated with incident chronic kidney disease and a more rapid decline in the eGFR in persons with normal kidney function at baseline.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Abraham J. and Phyllis Katz Foundation, Robert W. Woodruff Health Sciences Center Fund, Emory Heart and Vascular Center, and grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (UL1 RR025008 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award program, R01 HL089650 and R01 HL113451 to Dr. Quyyumi, and R01 DK101350 to Drs. Sever and Reiser). The Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (U01-AI-103401, U01-AI-103408, U01-AI-35004, U01-AI-31834, U01-AI-34994, U01-AI-103397, U01-AI-103390, U01-AI-34989, and U01-AI-42590), with additional cofunding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of Mental Health. Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects is also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health.

We thank Myles Wolf (Northwestern University), Andrew Levey (Tufts Medical Center), Edmund Lewis (Rush University), and Stephen Korbet (Rush University) for their suggestions in the process of preparing and revising an earlier version of the manuscript; Isabel Fernandez, Beata Tryniszewska, Jing Li, and Yanxia Cao for assistance with measuring suPAR in WIHS samples; and the members of the WIHS, Emory Biobank Team, Emory Clinical Cardiovascular Research Institute, and Atlanta Clinical and Translational Science Institute for recruitment of participants, compilation of data, and preparation of samples.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org

References

- 1.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:2038–47. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gansevoort RT, Correa-Rotter R, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet. 2013;382:339–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James MT, Hemmelgarn BR, Tonelli M. Early recognition and prevention of chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2010;375:1296–309. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levey AS, Cattran D, Friedman A, et al. Proteinuria as a surrogate outcome in CKD: report of a scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation and the US Food and Drug Administration. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:205–26. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallan SI, Ritz E, Lydersen S, Romundstad S, Kvenild K, Orth SR. Combining GFR and albuminuria to classify CKD improves prediction of ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1069–77. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thunø M, Macho B, Eugen-Olsen J. suPAR: the molecular crystal ball. Dis Markers. 2009;27:157–72. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2009-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei C, Möller CC, Altintas MM, et al. Modification of kidney barrier function by the urokinase receptor. Nat Med. 2008;14:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huai Q, Mazar AP, Kuo A, et al. Structure of human urokinase plasminogen activator in complex with its receptor. Science. 2006;311:656–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1121143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Witte H, Sweep F, Brunner N, et al. Complexes between urokinase-type plasminogen activator and its receptor in blood as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Int J Cancer. 1998;77:236–42. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980717)77:2<236::aid-ijc12>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sier CF, Sidenius N, Mariani A, et al. Presence of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor in urine of cancer patients and its possible clinical relevance. Lab Invest. 1999;79:717–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gustafsson A, Ajeti V, Ljunggren L. Detection of suPAR in the saliva of healthy young adults: comparison with plasma levels. Biomark Insights. 2011;6:119–25. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S8326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Theilade S, Lyngbaek S, Hansen TW, et al. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor levels are elevated and associated with complications in patients with type 1 diabetes. J Intern Med. 2015;277:362–71. doi: 10.1111/joim.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoo TH, Pedigo CE, Guzman J, et al. Sphingomyelinase-like phosphodiesterase 3b expression levels determine podocyte injury phenotypes in glomerular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:133–47. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013111213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Bock CE, Wang Y. Clinical significance of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) expression in cancer. Med Res Rev. 2004;24:13–39. doi: 10.1002/med.10054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Backes Y, van der Sluijs KF, Mackie DP, et al. Usefulness of suPAR as a biological marker in patients with systemic inflammation or infection: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1418–28. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2613-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borné Y, Persson M, Melander O, Smith JG, Engström G. Increased plasma level of soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor is associated with incidence of heart failure but not atrial fibrillation. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:377–83. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eugen-Olsen J, Andersen O, Linneberg A, et al. Circulating soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor predicts cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and mortality in the general population. J Intern Med. 2010;268:296–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuhrman B. The urokinase system in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2012;222:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyngbæk S, Marott JL, Sehestedt T, et al. Cardiovascular risk prediction in the general population with use of suPAR, CRP, and Framingham Risk Score. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2904–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eapen DJ, Manocha P, Ghasemzedah N, et al. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor level is an independent predictor of the presence and severity of coronary artery disease and of future adverse events. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(5):e001118. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei C, El Hindi S, Li J, et al. Circulating urokinase receptor as a cause of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Med. 2011;17:952–60. doi: 10.1038/nm.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei C, Trachtman H, Li J, et al. Circulating suPAR in two cohorts of primary FSGS. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:2051–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012030302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spinale JM, Mariani LH, Kapoor S, et al. A reassessment of soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor in glomerular disease. Kidney Int. 2015;87:564–74. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(Suppl 1):S1–S266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeppesen J, Hansen TW, Olsen MH, et al. C-reactive protein, insulin resistance and risk of cardiovascular disease: a population-based study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15:594–8. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328308bb8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uno H, Cai T, Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Wei LJ. On the C-statistics for evaluating overall adequacy of risk prediction procedures with censored survival data. Stat Med. 2011;30:1105–17. doi: 10.1002/sim.4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Epidemiology. 1998;9:117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hessol NA, Schneider M, Greenblatt RM, et al. Retention of women enrolled in a prospective study of human immunodeficiency virus infection: impact of race, unstable housing, and use of human immunodeficiency virus therapy. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:563–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.6.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang TJ. Assessing the role of circulating, genetic, and imaging biomarkers in cardiovascular risk prediction. Circulation. 2011;123:551–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.912568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maile LA, Gollahon K, Wai C, Dunbar P, Busby W, Clemmons D. Blocking alphaVbeta3 integrin ligand occupancy inhibits the progression of albuminuria in diabetic rats. J Diabetes Res. 2014:421827. doi: 10.1155/2014/421827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maile LA, Busby WH, Gollahon KA, et al. Blocking ligand occupancy of the αVβ3 integrin inhibits the development of nephropathy in diabetic pigs. Endocrinology. 2014;155:4665–75. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delville M, Sigdel TK, Wei C, et al. A circulating antibody panel for pretransplant prediction of FSGS recurrence after kidney transplantation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:256ra136. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersen O, Eugen-Olsen J, Kofoed K, Iversen J, Haugaard SB. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor is a marker of dysmetabolism in HIV-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Med Virol. 2008;80:209–16. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson DW. Evidence-based guide to slowing the progression of early renal insufficiency. Intern Med J. 2004;34:50–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0903.2004.t01-6-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fassett RG, Venuthurupalli SK, Gobe GC, Coombes JS, Cooper MA, Hoy WE. Biomarkers in chronic kidney disease: a review. Kidney Int. 2011;80:806–21. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meijers B, Poesen R, Claes K, et al. Soluble urokinase receptor is a biomarker of cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2015;87:210–6. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fox CS, Larson MG, Leip EP, Culleton B, Wilson PWF, Levy D. Predictors of new-onset kidney disease in a community-based population. JAMA. 2004;291:844–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.7.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.