Abstract

Irreversible tropane analogs have been useful in identifying binding sites of cocaine on biogenic amine transporters, including transporters for dopamine (DAT), serotonin (SERT) and norepinephrine (NET). The present study characterizes the properties of the novel phenylisothiocyanate tropane HD-205, synthesized from the highly potent 2-napthyl tropane analog WF-23. In radioligand binding studies in brain membranes, direct IC50 values of HD-205 were 4.1, 14 and 280 nM at DAT, SERT and NET, respectively. Wash-resistant binding was characterized by preincubation of HD-205 with brain membranes, followed by extensive washing before performing transporter radioligand binding. Results for HD-205 showed wash-resistant IC50 values of 191 nM, 230 nM and 840 nM at DAT, SERT and NET, respectively. Saturation binding studies with [125I]RTI-55 in membranes pretreated with 100 nM HD-205 showed that HD-205 significantly decreased the Bmax but not KD of DAT and SERT binding. To further characterize its irreversible binding, an iodinated analog of HD-205, HD-244, was prepared from a trimethylsilyl precursor. The direct IC50 of HD-244 at DAT was 20 nM. [125I]HD-244 was synthesized with chloramine-T, purified on HPLC, reacted with rat striatal membranes, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Results showed several non-specific labeled bands, but only a single specific band of radioactivity co-migrating with an immunoreactive DAT band at approx. 80 kDa was detected, suggesting that [125I]HD-244 covalently labeled DAT protein in striatal membranes. These results demonstrate that phenylisothiocyanate analogs of WF-23 can be used as potential ligands to map distinct binding sites of cocaine analogs at DAT.

1. Introduction

Cocaine binds to dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine transporters (DAT, SERT and NET respectively) with approximately equal affinities, preventing the reuptake of monoamines into presynaptic neurons. Although SERT and NET play important roles in the actions of cocaine, DAT has been the primary target for development of effective pharmacotherapeutics for cocaine abuse. The increased synaptic levels of dopamine, resulting in prolonged stimulation of dopamine receptors, is believed to be a primary neurochemical mechanism underlying the psychostimulant and reinforcing actions of cocaine [1].

The rapid metabolism of cocaine by cholinesterases [2] is crucial in the pharmacokinetics of cocaine and is a limiting factor to developing cocaine-related pharmacotherapeutic agents. As an alternative, many laboratories have developed metabolically stable compounds based on the structure of cocaine [3–10]. Development of novel cocaine analogs has two purposes: first, as potential therapeutic agents to treat cocaine abuse; second, as ligands to probe the structure of cocaine binding site on monoamine transporters. Numerous cocaine analogs have been studied in vivo, and several compounds are reported to attenuate cocaine’s effects in animal models of psychomotor stimulant abuse [6, 11]. Some of these have been evaluated preclinically and several are in clinical trials [12, 13]. Radioligands synthesized from these compounds have been effective in vitro ligands for transporter binding [11, 14, 15] as well as PET ligands for in vivo imaging [16–18]. Furthermore, the structure-activity relationships of cocaine analogs have provided vital information to design specific molecular tools to characterize the structure and function of DAT, and to further explore its role in the pharmacology of cocaine.

The amino acid residues in DAT responsible for cocaine binding have been identified by techniques such as site-directed mutagenesis [19–23] which, while important, can be problematic because a change in a single amino acid can alter the protein’s conformational structure and affect the interpretation of results. An alternative approach uses irreversible ligands as probes for cocaine binding sites in DAT. Several studies have reported the existence of multiple binding sites for different inhibitors on DAT, and studies with irreversible ligands may be important in mapping these respective sites [24–27]. Both photoaffinity ligands [28–30] and alkylating reagents [31–34], including the tropane analog [125I]RTI-82 [35], have been used to identify the ligand binding sites of cocaine and related tropane analogs on DAT. In addition, alkylating agents including isothiocyanate and bromoacetamide tagged to cocaine, rimcazole and benztropine analogs have been successful as irreversible DAT analogs [31, 32, 36].

In the present study, we report on the properties of a novel phenylisothiocyanate tropane analog, HD-205, as a potential irreversible ligand at DAT. This analog was synthesized from WF-23, a 2-napthyl analog that exhibits some of the most potent affinities at DAT and SERT of any tropane analog reported [37]. An iodinated form of HD-205, HD-244, was used to label DAT in rat striatal membranes. These results demonstrate that a phenylisothiocyanate 2-napthyl tropane can be a useful irreversible ligand for labeling biogenic amine transporters.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

Frozen male rat brains were obtained from Pel-Freez Biologicals (Rogers, AR). [125I]RTI-55 (2200 Ci/mmol), [3H]citalopram (81.2 Ci/mmol), [3H]nisoxetine (70 Ci/mmol), and Na[125I] (17.4 Ci/mg) were purchased from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA). Iodo-beads iodination reagent was obtained from Pierce Chemicals (Rockford, IL). Monoclonal antibody to rat DAT was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) and secondary antibody, peroxidase conjugated affinity-purified anti-rat IgG, was obtained from Rockland (Gilbertsville, PA). Immobilon western chemiluminescent HRP substrate was obtained from Millipore Corp. (Billerica, MA). X-ray films were purchased from Phenix Research (Hayward, CA). Nova-Pak C18 HPLC column was obtained from Waters Chromatography (Milford, MA). Buffers and other chemicals were reagent grade chemicals from Sigma and Fisher.

2.2 Binding studies

Affinities of analogs at DAT were determined by displacement of [125I]RTI-55 binding in rat striatal membranes [11]. Frozen male rat brains were thawed on ice and striata were dissected. Tissue was homogenized in 10 vol of DAT assay buffer (0.32 M sucrose, 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) with a Polytron (setting 6, 20 sec), and centrifuged three times at 48,000 × g for 10 min. Assay tubes contained 0.5 mg (original wet weight) of membranes, 10 pM [125I]RTI-55, and various concentrations of unlabeled drugs dissolved in DAT assay buffer in a final volume of 2 ml. Tubes were incubated for 50 min at 25°, and the reaction was terminated by rapid filtration with 3 × 5 ml of cold 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.3 through Whatman GF/B glass fiber filters pre-soaked in Tris buffer containing 0.1% BSA.

Affinities of analogs at SERT were determined by displacement of [3H]citalopram binding [38]. Frozen whole male rat brain (minus cerebellum) was thawed on ice and homogenized in 10 vol of SERT assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, pH 7.4), and centrifuged two times at 48,000 × g for 10 min. Assay tubes contained 50 mg (original wet weight) of membranes, 0.4 nM [3H]citalopram, and various concentrations of unlabeled drugs dissolved in SERT assay buffer in a final volume of 2 ml. Tubes were incubated for 60 min at 25°, and the reaction was terminated by rapid filtration with 3 × 4 ml of cold Tris buffer through Whatman GF/B glass fiber filters pre-soaked in Tris buffer containing 0.5% polyethyleneimine.

Binding of analogs at NET was determined by displacement of [3H]nisoxetine binding [39]. Frozen whole male rat brain (minus cerebellum) was thawed on ice and homogenized in 30 vol of NET membrane buffer (120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4), and centrifuged at 48,000 × g for 10 min. The membranes were resuspended in NET assay buffer (300 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) and centrifuged again before final resuspension in 50 vol of NET assay buffer. Assay tubes contained 750 μl of brain membranes, [3H]nisoxetine (0.7 nM) together with unlabeled drugs dissolved in NET assay buffer to a final volume of 1 ml. Tubes were incubated for 40 min at 25°, and the reaction was terminated by rapid filtration with 3 × 4 ml of cold Tris buffer through Whatman GF/B glass fiber filters pre-soaked in Tris buffer containing 0.1% BSA.

In all binding assays, non-specific binding was determined with 1 μM WF-23. Radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry in 5 ml of Ecolite scintillation fluid (ICN); for [3H] assays (50% efficiency), filters were eluted overnight. In all assays, protein values were determined by the method of Bradford [40].

IC50 values were calculated from displacement curves using 7–10 concentrations of unlabeled analogs. All data are mean values ± S.E.M. of at least three separate experiments, each of which was conducted in triplicate.

2.3 Wash-resistant binding

Wash-resistant affinities of analogs at transporters were determined by displacement of radioligand binding in rat brain membranes after preincubation with analogs and extensive washing of membranes. Rat brain membranes were prepared as described above for DAT, SERT and NET assays, and diluted in 6 one-ml aliquots of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0. Membranes were preincubated for 1 hr at 25° with various concentrations of analogs and terminated by dilution with 30 ml HEPES. Tubes were washed five times, with each wash consisting of centrifugation at 48,000 × g for 10 min, incubation for 20 min at 25°, and centrifugation again. After the final wash, membranes were resuspended in DAT, SERT and NET assay buffers and binding was performed as described above. All data are mean values ± S.E.M. of at least three separate experiments, each of which was conducted in triplicate.

For saturation analyses of wash-resistant binding, membranes were preincubated with 100 nM HD-205 as described above, using three times the amount of membrane protein compared to previous studies. After five wash steps, saturation binding was conducted using various concentrations of [3H]citalopram (SERT) or various concentrations of unlabeled RTI-55 displacing 10 pM [125I]RTI-55 (DAT) as described for direct binding assays above. Calculations of KD and Bmax values were performed by non-linear curve fitting (Prism, Graphpad).

2.4. Radiolabeling and HPLC purification of irreversible tropane analog

The iodinated form of HD-205, HD-244, was synthesized from the trimethylsilyl precursor HD-243. The radioiodination reaction consisted of 600 μCi Na[125I], 100 mM HEPES, two iodo beads (containing a bound form of chloramine-T) and 8 nmol of HD-243 in a total volume of 120 μl. Tubes were incubated for 30 min and the reaction was terminated by removal of iodo beads. Purification of radiolabeled [125I]HD-244 from unreacted HD-243 was done by injecting the reacted sample on a C-18 reverse phase column (Nova-Pak C-18, 4 μm, 3.9×150 mm), with a flow rate of 1 ml/min, using a two solvent gradient consisting of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0 and 100% acetonitrile. UV absorbance was monitored at 235 nm and radioactivity was determined in 10 μl aliquots from each 1 ml fraction.

DAT binding assays in rat striatal membranes were performed on each active fraction from the HPLC. Equal amounts of [125I] (60,000 cpm) were added to tubes containing 0.5 mg (original wet weight) of striatal membranes with and without 1 μM WF-23, and incubated as described above for [125I]RTI-55 binding. Peak fractions of specific [125I] bound were pooled, concentrated in a speed-vac, and used in labeling DAT protein.

2.5 Radiolabeling of DAT protein

Rat striatal membranes (200 μg protein) were treated with equal amounts of [125I]HD-244 (4 × 106 cpm) in the presence and absence of 1 μM WF-23. The reaction was terminated with 1 ml sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, and tubes centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was discarded, the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml sodium phosphate buffer, and tubes centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was discarded, the pellet was dissolved in a 1:1 ratio of 10% SDS with loading buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl, 2% SDS, 20% glycerol, and 2% 2-mercaptoethanol) and boiled for 2 min. Samples were run on 10% SDS-PAGE with molecular markers; the gel was dried, exposed to a phosphorimaging screen, scanned after 72 hr exposure, and analyzed by densitometric analysis. For photography, the gel was re-exposed to X-ray film for 6 weeks.

2.6 Western blots of DAT protein

Rat striatal and cerebellar membranes (200 μg protein each) were dissolved in 1:1 ratio of 10% SDS with loading buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl, 2% SDS, 20% glycerol, and 2% 2-mercaptoethanol), and boiled for 2 min. Samples were run on 10% SDS PAGE with molecular weight markers (Invitrogen; BIO-RAD), then transferred electrophoretically to PVDF membranes pre-soaked for 5 min in Bjerrum/Schafer-Nielsen buffer (48 mM Tris, 39 mM glycine, 20% methanol, pH 9.2). After transfer, membranes were incubated for 15 hr at 4° with 1:200 dilutions of primary monoclonal antibody obtained from Abcam (prepared from the 66 amino acids from the amino terminus of rat DAT). The blot was washed and incubated in peroxidase-conjugated affinity purified anti Rat-IgG (1:2000). The membrane was then treated with chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Millipore) for 2–5 min, then dried and exposed to X-ray film for 30 sec – 3 min.

3. Results

3.1 Novel tropane analogs as potential irreversible DAT ligands

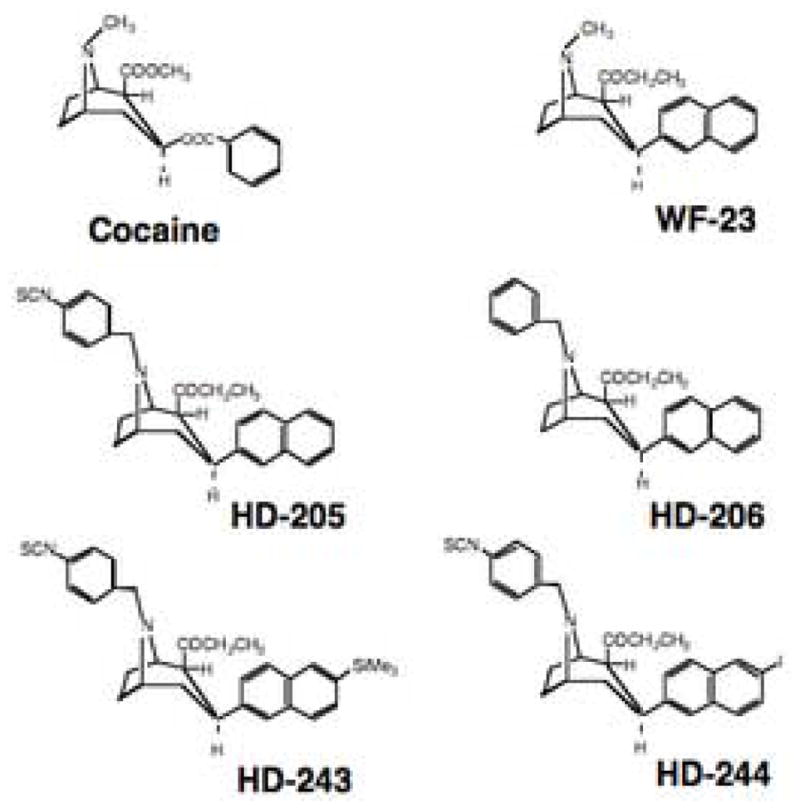

Fig. 1 shows the structures of several relevant tropane analogs compared to cocaine. To produce a potent irreversible tropane analog that would potentially react with all three monoamine transporters (DAT, SERT and NET), analogs were chosen based on the parent structure of WF-23, a 2-napthyl tropane analog that binds with high affinity to DAT, NET and SERT [37]. The result was HD-205, a modified tropane analog in which a phenylisothiocyanate moiety was attached to the tropane nitrogen of WF-23 (Fig. 1). In addition, HD-206 was also developed as a reversible control analog, identical in structure to HD-205 except lacking its isothiocyanate group. To prepare a radiolabeled form of HD-205, [125I] was added in the para position of the 2-napthyl moiety of HD-205 to prepare HD-244. A trimethylsilyl derivative, HD-243, was used as a precursor to prepare HD-244.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of tropane analogs.

3.2 Wash-resistant binding of HD-205 to biogenic amine transporters in brain

Irreversible binding of ligands occurs in two steps: a reversible binding of the ligand to its binding site, followed by covalent reaction of the active moiety of the ligand with relevant amino acids. Standard radioligand binding, conducted at equilibrium for the radioligand, actually measures both steps, while wash-resistant binding assays focus on the irreversible step. In the present study, affinities of analogs determined in standard binding assays will be referred to as direct IC50 values, to distinguish from wash-resistant IC50 values. Direct IC50 values for HD-205 and HD-206 in displacing [125I]RTI-55 at DAT, [3H]citalopram at SERT and [3H]nisoxetine at NET are presented in Table 1, compared to direct IC50 values of the parent compound WF-23 from previous literature [37]. WF-23 exhibited very high affinities at both DAT (0.20 nM) and SERT (0.39 nM), with lower affinity at NET (2.9 nM). Addition of the phenylisothiocyanate to form HD-205 significantly increased direct IC50 values: 4 nM at DAT, 14 nM at SERT and 280 nM at NET. However, affinities at both DAT and SERT remained sufficiently high to proceed with further wash-resistant studies. The direct IC50 value of the control analog HD-206 was similar to HD-205 at DAT (9 nM), but HD-206 was more potent than HD-205 at both SERT and NET (1.6 nM and 29 nM, respectively).

Table 1.

Direct and wash-resistant IC50 values of tropanes in binding to monoamine transporters in rat brain membranes

| Transporter | Direct IC50 values (nM):

|

Wash-resistant HD-205 IC50 (nM) | IC50 Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WF-23* | HD-205 | HD-206 | |||

| DAT | 0.20 | 4.07 ± 0.93 | 8.99 ± 2.74 | 252 ± 30 | 62 |

| SERT | 0.39 | 14.1 ± 0.91 | 1.62 ± 0.58 | 207 ± 6.3 | 15 |

| NET | 2.90 | 284 ± 92 | 28.6 ± 3.9 | 991 ± 63* | 3.4 |

Direct IC50 values of tropane analogs were calculated from displacement curves of [125I]RTI-55 (DAT) binding in striatal membranes, and [3H]citalopram (SERT) and [3H]nisoxetine (NET) binding in membranes from whole brain (minus cerebellum). Direct IC50 values for WF-23 are cited from Bennett et al. [37]. Wash-resistant IC50 values for HD-205 were determined by preincubating membranes with various concentrations of HD-205 for 1 hr, followed by five washes, before performing radioligand binding as described in Methods. The wash-resistant IC50 value of HD-205 at NET (*) was estimated by non-linear curve fitting. The ratio column indicates the ratio between wash-resistant and direct IC50 values of HD-205. All data are mean values ± S.E.M. of at least three separate experiments, each of which was conducted in triplicate.

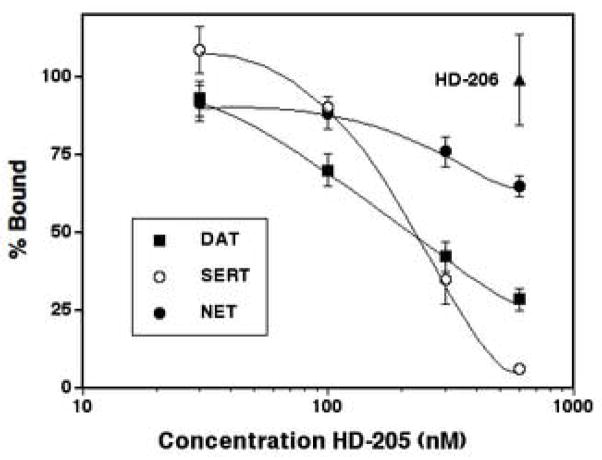

Fig. 2 shows the wash-resistant inhibition of radioligand binding at DAT, SERT and NET following preincubation with 30–600 nM HD-205, or with 600 nM of the reversible analog HD-206. Unlike HD-206, which produced no wash-resistant inhibition of binding, HD-205 produced concentration-dependent wash-resistant inhibition of radioligand binding to all three transporters. The potency of HD-205 varied between the three transporters, with wash-resistant IC50 values of 252 nM at DAT and 207 nM at SERT (Table 1). HD-205 also produced wash-resistant inhibition of binding at NET, but the exact IC50 value could not be calculated because the highest concentration used, 600 nM, produced only 35% inhibition of binding at NET. Non-linear curve-fitting produced an estimated IC50 value of 991 nM at NET (Table 1). In all cases, wash-resistant IC50 values were significantly higher than direct IC50 values (Table 1), with IC50 ratios of 62, 15 and 3 at DAT, SERT and NET, respectively (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Wash-resistant inhibition of radioligand binding at DAT, SERT and NET by HD-205 and HD-206. Rat striatal or whole brain membranes were preincubated for 1 hr at 25° with various concentrations of tropane analogs, then subjected to five washes before determination of radioligand binding with [125I]RTI-55 (DAT), [3H]citalopram (SERT) and [3H]nisoxetine (NET) as described in Methods. For preincubation with HD-206 (600 nM), results averaged for all the three transporters are shown. The individual data for HD-206 at the three transporters (expressed as % control) are: 84% ± 10%, 99% ± 15% and 102% ± 11% at DAT, SERT and NET respectively.

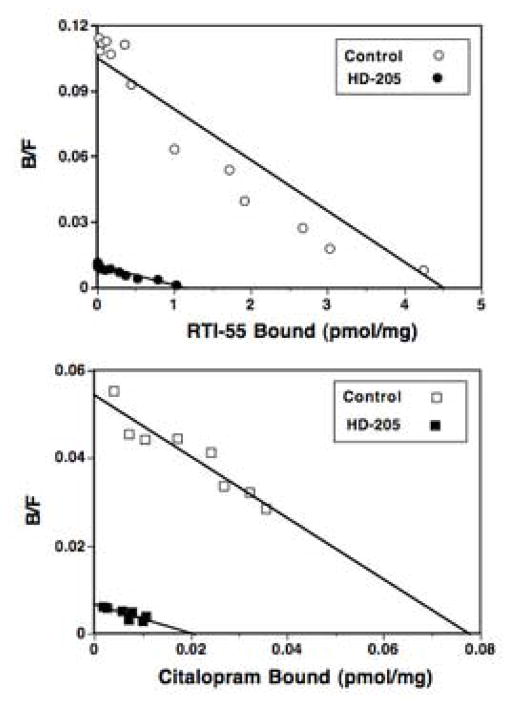

If wash-resistant binding of HD-205 represents a covalent reaction of the drug with monoamine transporters, then it should produce a reduction in Bmax, not KD, of transporter radioligand binding. Saturation analysis of transporter binding was performed in brain membranes following preincubation with 100 nM HD-205 or buffer (control). Fig. 3 shows representative Scatchard plots of radioligand binding at DAT and SERT. For both transporters, the wash-resistant effects of HD-205 produced a significant decrease in Bmax of radioligand binding with no significant effects on KD values. Table 2 shows KD and Bmax values from saturation binding of [125I]RTI-55 and [3H]citalopram after preincubation with 100 nM HD-205. [3H]citalopram binding at SERT was monophasic, and preincubation with HD-205 reduced the Bmax by 87% with no significant change in KD values. The results at DAT were similar (Table 2): preincubation with 100 nM HD-205 reduced the Bmax of [125I]RTI-55 binding by 73%, with no significant change in the KD values, as calculated by a single site analysis. These wash-resistant effects on Bmax values were somewhat higher than those predicted from the wash-resistant IC50 values calculated from Fig. 2, but the preincubations with HD-205 were conducted under different conditions between the two assays. In particular, the use of significantly larger quantities of membrane protein for the saturation studies could increase the apparent wash-resistant effects of HD-205.

Fig. 3.

Wash-resistant effects of HD-205 on Scatchard plots of DAT binding (top) and SERT binding (bottom). Membranes were preincubated with 100 nM HD-205 for 1 hr at 25°, followed by five washes prior to radioligand binding. Data are typical plots from experiments repeated at least three times. Lines represent best-fit parameters for single-site analysis.

Table 2.

Wash-resistant effects of HD-205 on KD and Bmax values of [125I]RTI-55 (DAT) and [3H]citalopram (SERT) binding in rat brain membranes

| Pretreatment:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Transporter | Control | HD-205 | |

| DAT | KD (nM) | 6.13 ± 1.07 | 5.52 ± 1.14 |

| Bmax (pmol/mg) | 5.65 ± 0.90 | 1.50 ± 0.38* | |

| SERT | KD (nM) | 1.19 ± 0.17 | 0.92 ± 0.17 |

| Bmax (pmol/mg) | 0.77 ± 0.12 | 0.096 ± 0.01* | |

Saturation binding studies were conducted after preincubating striatal membranes (DAT) or forebrain membranes (SERT) with buffer (control) or 100 nM HD-205 for 1 hr, followed by five washes as described in Methods. Saturation binding at DAT was conducted with 10 pM [125I]RTI-55 with varying concentrations (0.1 nM–40 nM) of unlabeled RTI-55. Saturation binding at SERT was conducted using varying concentrations (0.03 nM–1.6 nM) of [3H]citalopram. Binding parameters for both DAT and SERT were calculated by single-site analysis of nonlinear curve fitting (GraphPad Prism) of specific binding data. All data represent mean values ± S.E.M. of at least three separate experiments, each of which was conducted in triplicate.

p < 0.005 different from control values, Student’s t-test.

3.3 Radiolabeling of HD-205 and covalent labeling of DAT

To radiolabel HD-205, the trimethylysilyl analog HD-243 (Fig. 1) was synthesized as a precursor. Non-radioactive iodine was used to synthesize unlabeled HD-244 (Fig. 1) from HD-243. The direct IC50 value for HD-244 at DAT was 20 nM, five fold lower affinity than the parent analog HD-205 (Table 1) but still relatively potent as a DAT ligand. In contrast, the trimethylysilyl precursor HD-243 was very weak at DAT (176 nM).

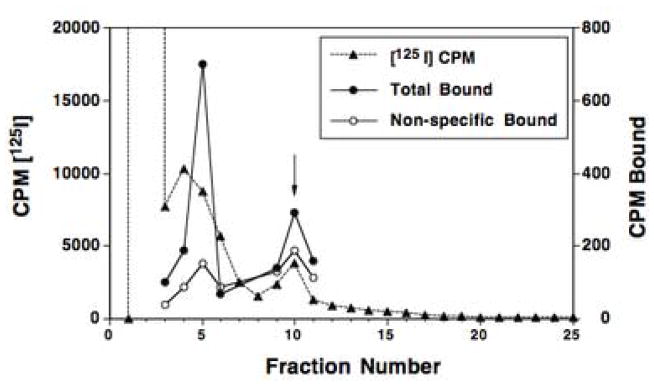

Radioiodination of HD-243 was performed with Na[125I] and purification of [125I]HD-244 was accomplished by reverse phase HPLC (Fig. 4). The arrow in Fig. 4 shows the elution position of non-radioactive HD-244 in fraction 10. After reaction of HD-243 with Na[125I], over 99% of the radioactivity eluted in the void volume (fractions 2–3). However, small peaks of [125I] eluted in fractions 5, 10 and 14. To determine which of these peaks correspond to authentic [125I]HD-244, we performed DAT binding studies in striatal membranes with aliquots from HPLC fractions. Equal amounts of [125I] (60,000 cpm) from fractions 3–11 were incubated with striatal membranes in the presence and absence of 1 μM WF-23 to distinguish specific and non-specific binding. Binding in each fraction is presented in Fig. 4 as total and non-specific binding. Results showed that the highest amount of specific binding was detected in fractions 5 and 10, with fraction 10 corresponding to the elution position of unlabeled HD-244.

Fig. 4.

Purification and pharmacological characterization of radiolabeled [125I]HD-244 by HPLC. After reaction of HD-243 with 600 μCi of Na[125I] with iodo-beads, samples were eluted on a C18 HPLC column using a linear gradient of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0 and acetonitrile. Arrow indicates the elution position of non-radioactive HD-244. Radioactivity (closed triangles) was determined in 10 μl aliquots from each fraction; expressed as cpm × 10−3. Equal amounts of [125I] (60,000 cpm) from fractions 3–11 were used in DAT binding assays with rat striatal membranes in the presence (closed circles) and absence (open circles) of WF-23 to distinguish total and non-specific binding.

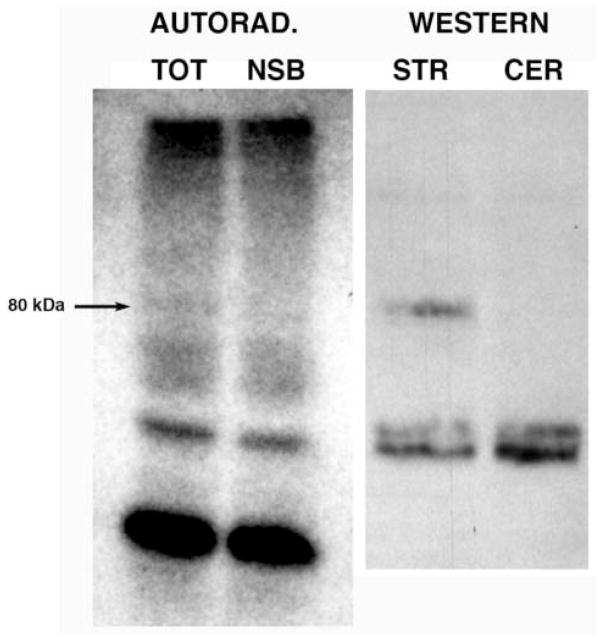

Rat striatal membranes were incubated with [125I] from both HPLC fractions 5 and 10 (Fig. 4) in the presence and absence of 1 μM WF-23 to distinguish total and non-specific labeling. After centrifugation to remove unbound [125I], membranes were dissolved in SDS, and samples were run on SDS-PAGE. Results using [125I] from fraction 5 showed no specific labeling of bands on SDS gels (data not shown). However, specific labeling of one band at 80 kDa was observed using with [125I] from fraction 10. Fig. 5 shows the resulting autoradiogram (left) with lanes of total (TOT) and non-specific (NSB) binding, along side a Western blot (right) from unlabeled striatal and cerebellar membranes run in parallel. The autoradiogram shows numerous bands labeled with [125I]HD-244 in both total and NSB lanes. However, one labeled band at approximately 80 kDa (arrow in Fig. 5) was present in the TOT lane but not visible in the NSB lane. The Western blot confirmed that this labeled band at 80 kDa co-migrated with the immunoreactive DAT band in striatal membranes that was absent in cerebellar membranes. These results from SDS-PAGE autoradiography strongly suggest that [125I]HD-244 covalently labeled DAT protein in rat striatal membranes. The efficiency of this covalent reaction of DAT with [125I]HD-244 was very low: approximately 1.7% of the total [125I]HD-244 added to striatal membranes reacted with the bands identified on the SDS gel, and less than 0.1% of the reacted radioactivity was associated with the 80 kDa DAT band.

Fig. 5.

Covalent labeling of striatal membrane proteins with [125I]HD-244. Rat striatal membranes were incubated with [125I]HD-244 for 1 hr at 25° in the presence and absence of 1 μM WF-23, solubilized in SDS buffer, and proteins separated by SDS-PAGE. Left, autoradiography of SDS-PAGE gel. TOT: total binding (without WF-23); NSB: non-specific binding (with WF-23). Right, Western blot of unlabeled membranes from rat striatum (STR) and cerebellum (CER) indicating the position of immunoreactive DAT protein in striatal membranes, using primary antibody directed against rat DAT (Abcam).

4. Discussion

In this manuscript we report the synthesis and characterization of the novel phenylisothiocyanate-based irreversible ligand HD-205. With a direct IC50 value of 4 nM, HD-205 is one among the most potent potential irreversible analogs for DAT reported so far. Irreversible ligands bind covalently at the ligand recognition site of the transporter and have been designed as valuable molecular probes in identifying specific amino acid residues involved in ligand binding. Although other irreversible DAT ligands have been synthesized in previous studies, it is critical to design ligands with different structural moieties to probe the cocaine binding pharmacophore. HD-205 is potentially important as an irreversible ligand because it is derived from the 2-napthyl tropanes, which have among the highest affinities at DAT of any tropanes synthesized, and because it utilizes phenylisothiocyanate (NCS) for covalent reaction, an approach that has met with limited success in previous studies.

Irreversible ligands including photoaffinity ligands [28–30] and alkylating reagents [31–34] have been used for identification of binding sites on DAT. Irreversible DAT ligands including [125I]DEEP, a GBR-based photoaffinity ligand and [125I]GA-II-34, a benztropine derivative, labeled residues in TM1 and TM2 of DAT, whereas the cocaine analog [125I]RTI-82 labeled TM6 [28, 29, 35, 41]. [125I]AD-96-129, another GBR analog, exhibits a two-site pattern on incorporation not previously observed for DAT [30]. These data suggest the distinctive pattern of binding exhibited by a wide variety of cocaine related compounds and the complexity involved in understanding the cocaine pharmacophore.

An isothiocyanato tropane ligand based on RTI-82, with a direct IC50 of 32 nM at DAT, has been shown to exhibit wash-resistant binding [32]. On the other hand, isothiocyanate benztropine analogs did not retain sufficient affinity at DAT to be used as potential irreversible ligands [32]. It is possible that HD-205 would label the same amino acid residues on DAT that have previously been demonstrated with other phenylisothiocyanate tropane analogs; however, the unique presence of the 2-napthyl group on HD-205 may provide alternative binding sites on DAT that would help to further define the tropane pharmacophore on the transporter.

In this study the isothiocyanato tropane HD-205, derived from the 2-napthyl tropane WF-23, was evaluated for its direct and wash-resistant affinities at DAT, SERT and NET. The addition of the phenylisothiocyanate to the parent structure WF-23 significantly reduced affinities at all three transporters. The reduction in affinity by adding phenylisothiocyanate is not unusual in structure activity relationship studies [31, 32]. Fortunately, the direct IC50 values of 4 nM and 14 nM at DAT and SERT, respectively, showed that HD-205 retained relatively high potency at DAT and SERT despite the loss of potency compared to WF-23. The low potency of HD-205 at NET, approximately 300 nM, suggests that this ligand may not be ideal as a probe for norepinephrine transporters. On the other hand, tropane analogs in general have been shown to be relatively weak in displacing [3H]nisoxetine binding to NET [42]. For this reason, HD-205 may actually be more potent in irreversibly blocking norepinephrine uptake than predicted from these [3H]nisoxetine binding results.

Wash-resistant binding studies showed that HD-205 produced a concentration-dependent wash-resistant inhibition of radioligand binding at all three transporters. This effect was not produced by the control analog HD-206 lacking isothiocyanate, even at the highest concentration of 600 nM. Since in direct binding assays HD-206 was similarly potent compared to HD-205 at DAT, and about ten times more potent than HD-205 at SERT, it is unlikely that this difference in wash-resistant binding is due to highly potent lipophilic compounds surviving multiple washes. Moreover, the wash-resistant binding results showed that the direct potencies of HD-205 at various transporters did not predict its wash-resistant potencies. For example, the wash-resistant potency of HD-205 was the same for both DAT and SERT, despite a three-fold difference in potency of HD-205 at DAT and SERT in direct binding assays. This suggests that HD-205 is more efficient in covalently labeling SERT than DAT.

Saturation binding studies at both SERT and DAT after preincubation of brain membranes with HD-205 further suggested a covalent interaction of the drug at these transporters, since pretreatment with HD-205 decreased Bmax with no effect on KD values of radioligand binding at both DAT and SERT. The results of DAT binding were somewhat complicated. Analyzed with a single-site model, preincubation of striatal membranes with 100 nM HD-205 reduced the Bmax of [125I]RTI-55 binding by 73%. Although previous studies [26, 27] have shown the existence of both high and low affinity tropane binding sites at DAT, and two binding sites for DAT has been reported with RTI-55 [7], the Scatchard plots from our studies analyzed by two-site models did not yield consistent results for high and low affinity sites of [125I]RTI-55, with an average calculated Hill slope of 0.8. It is possible that the preincubations and extensive washes necessary to define wash-resistant binding affected high affinity [125I]RTI-55 binding. Therefore, these results could not conclude whether HD-205 was reacting with the high or the low affinity site on DAT.

Although these wash-resistant binding studies suggested that HD-205 was reacting covalently with DAT and SERT, wash-resistant effects do not prove that the effects of HD-205 are mediated by covalent reaction with the transporter. Confirmation of the irreversible effects of HD-205 was obtained by SDS-PAGE of DAT-containing membranes labeled with an [125I] form of the drug. Radiolabeling of HD-205 to create [125I]HD-244 was accomplished with Na [125I] and HD-243 with chloramine-T on iodo-beads, followed by separation of radiolabeled material by HPLC. The pharmacological identity of [125I]HD-244 was confirmed when aliquots from HPLC fractions were tested in binding assays to show that specific binding of [125I]HD-244 occurred in those fractions that corresponded to the elution position of authentic HD-244 (Fig. 4). SDS-PAGE of striatal membranes incubated with [125I]HD-244 in presence and absence of 1 μM WF-23 revealed the presence of numerous bands in both the total and non-specific binding lanes (Fig. 5). This is not surprising, since isothiocyanate is highly reactive and will react with primary amino groups on a variety of proteins. However, only one band labeled in the total lane was blocked in the non-specific lane, and the position of this band at approximately 80 kDa co-migrated with the immunoreactive DAT band from striatal membranes run in a parallel experiment. These results strongly suggest that [125I]HD-244 covalently reacted with DAT in striatal membranes, although it reacted non-specifically with a variety of other proteins as well. This high level of non-specific binding may complicate the identification of specific labeling of amino acid residues on DAT; however, the use of transfected cell lines, as well as the use of high resolution mass spectroscopic methods coupled with immunoprecipitation and 2D electrophoresis to isolate DAT peptides after proteolytic cleavage, suggest that this reagent may be practical even with this high level of non-specific binding.

In summary, these results demonstrate that relatively potent isothiocyanate tropane analogs can be developed from the 2-napthyl WF-23 structure, and that such compounds can be used as irreversible probes of biogenic amine transporter structure. Knowledge of the amino acids on DAT that react with HD-205, when coupled with knowledge obtained from previous studies with other tropane and benztropine analogs, will provide important information about the site of cocaine action on these transporters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by grant DA-06634 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Abbreviations

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- SERT

5-HT transporter

- NET

norepinephrine transporter

- WF-23

2-β-propanoyl-3-β-(2-naphthyl)tropane

- HD-205

2-β-propanoyl-3-β-(2-naphthyl)-8-[(4-isothiocyanato)benzyl]nortropane

- HD-206

2-β-propanoyl-3-β-(2-naphthyl)-8-benzyl nortropane

- HD-243

2-β-propanoyl-3-β-(6-trimethylsilyl-2-naphthyl)-8-[(4-isothiocyanato)benzyl]nortropane

- HD-244

2-β-propanoyl-3-β-(6-iodo-2-naphthyl)-8-[(4-isothiocyanato)benzyl] nortropane

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science. 1987;237:1219–23. doi: 10.1126/science.2820058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johanson C, Schuster CR. Cocaine. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ, editors. Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. New York: Raven Press; 1995. pp. 1685–97. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothman RB, Becketts KM, Radesca LR, de Costa BR, Rice KC, Carroll FI, et al. Studies of the biogenic amine transporters. II. A brief study on the use of [3H]DA-uptake-inhibition to transporter-binidng-inhibition ratios for the in vitro evaluation of putative cocaine antagonists. Life Sci. 1993;53:PL267–72. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90602-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies HML, Saikali E, Young WB. Synthesis of (±)-ferruginine and (±)-anhydroecognine methyl ester by a tandem cyclopropananation/Cope rearrangement. J Org Chem. 1991;56:5696–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boja JW, Carroll FI, Rahman MA, Philip A, Lewin AH, Kuhar MJ. New, potent cocaine analogs: Ligand binding and transport studies on rat striatum. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;184:329–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90627-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll FI, Howell LL, Kuhar MJ. Pharmacotherapies for treatment of cocaine abuse: preclinical aspects. J Med Chem. 1999;42:2721–35. doi: 10.1021/jm9706729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boja JW, Mitchell WM, Patel A, Kopajtic TA, Carroll FI, Lewin AH, et al. High-affinity binding of [125I]RTI-55 to dopamine and serotonin transporters in rat brain. Synapse. 1992;12:27–36. doi: 10.1002/syn.890120104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies HML, Saikali E, Sexton T, Childers SR. Novel 2-substituted cocaine analogs: binding properties at dopamine transport sites in rat striatum. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;244:93–7. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(93)90063-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies HML, Saikali E, Huby NSJ, Gilliat VJ, Matasi J, Sexton T, et al. Synthesis of 2-beta-acyl-aryl-8-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octanes and their binding affinities at dopamine and serotonin transport sites in rat striatum and frontal cortex. J Med Chem. 1994;37:1262–8. doi: 10.1021/jm00035a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmquist CR, Keverline-Frantz KI, Abraham P, Boja JW, Kuhar MJ, Carroll FI. 3α-(4′-substituted phenyl)tropane-2β-carboxylic acid methyl esters: novel ligands with high affinity and selectivity at the dopamine transporter. J Med Chem. 1996;39:4139–41. doi: 10.1021/jm960515u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boja JW, Patel A, Carroll FI, Rahman MA, Philip A, Lewin AH, et al. [125I]RTI-55: a potent ligand for dopamine transporters. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;194:133–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90137-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sofuoglu M, Kosten TR. Novel approaches to the treatment of cocaine addiction. CNS Drugs. 2005;19:13–25. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200519010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorelick DA, Gardner EL, Xi Z. Agents in development for the management of cocaine abuse. Drugs. 2004;64:1547–73. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464140-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madras BK, Fahey MA, Bergman J, Canfield DR, Spealman RD. Effects of cocaine and related drugs in nonhuman primates. I. [3H] Cocaine binding sites in caudate-putamen. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:131–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dutta AK, Reith ME, Madras BK. Synthesis and preliminary characterization of a high-affinity novel radioligand for the dopamine transporter. Synapse. 2001;39:175–81. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(200102)39:2<175::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harada N, Ohba H, Fukumoto D, Kakiuchi T, Tsukada H. Potential of [18F]-CFT-FE(2 -Carbomethoxy-3 -(4-fluorophenyl)-8-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)nortropane) as a Dopamine Transporter Ligand: A PET Study in the Conscious Monkey Brain. Synapse. 2004;54:37–45. doi: 10.1002/syn.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stehouwer JS, Plisson C, Jarkas N, Zeng F, Ronald J, Voll RJ, Williams L, et al. Synthesis, radiosynthesis, and biological evaluation of carbon-11 and fluorine-18 (N-fluoroalkyl) labeled 2beta-carbomethoxy-3beta-(4′-(3-furyl)phenyl)-tropanes and -nortropanes: candidate radioligands for in vivo imaging of the serotonin transporter with positron emission tomography. J Med Chem. 2005;48:7080–3. doi: 10.1021/jm0504095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischman AJ, Bonab AA, Babich JW, Livni E, Alpert NM, Meltzer PC, et al. [11C,127I] Altropane: a highly selective ligand for PET imaging of dopamine transporter sites. Synapse. 2001;39:332–42. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010315)39:4<332::AID-SYN1017>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin Z, Uhl GR. Dopamine transporter mutants with cocaine resistance and normal dopamine uptake provide targets for cocaine antagonism. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:885–91. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.4.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang JB, Moriwaki A, Uhl GR. Dopamine transporter cysteine mutants: second extracellular loop cysteines are required for transporter expression. J Neurochem. 1995;64:1416–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64031416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin Z, Itokawa M, Uhl GR. Dopamine transporter proline mutations influence dopamine uptake, cocaine analog recognition, and expression. FASEB J. 2000a;14:715–28. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin Z, Wang W, Uhl GR. Dopamine transporter tryptophan mutants highlight candidate dopamine- and cocaine-selective domains. Mol Pharmacol. 2000b;58:1581–92. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitsuhata C, Kitayama S, Morita K, Vandenbergh D, Uhl GR, Dohi T. Tyrosine-533 of rat dopamine transporter: involvement in interactions with 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium and cocaine. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;56:84–8. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reith MEA, Berfield JL, Wang LC, Ferrer JV, Javitch JA. The uptake inhibitors cocaine and benztropine differentially alter the conformation of the human dopamine transporter. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:417–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011785200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reith ME, de Costa B, Rice KC, Jacobson AE. Evidence for mutually exclusive binding of cocaine, BTCP, GBR 12935 and dopamine to the dopamine transporter. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;227:417–25. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(92)90160-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madras BK, Spealman RD, Fahey MA, Neumeyer JL, Saha JK, Milius RA. Cocaine receptors labeled by [3H]2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-fluorophenyl)tropane. Mol Pharmacol. 1989;36:518–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothman RB, Cader JL, Akunne HC, Silverthorn ML, Bauman MH, Carroll FI, et al. Studies of the biogenic amine transporters. IV. Demonstration of a multiplicity of binding sites in rat caudate membranes for the cocaine analog [125I]RTI-55. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:296–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaughan RA, Parnas LM, Gaffaney JD, Lowe MJ, Wirtz S, Pham A, et al. Affinity labeling the dopamine transporter ligand binding site. Journal of Neurochemical Methods. 2005;143:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vaughan RA. Photoaffinity-labeled ligand binding domains on dopamine transporters identified by peptide mapping. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:956–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaughan RA, Gaffaney JD, Lever JR, Reith ME, Dutta AK. Dual incorporation of photoaffinity ligands on dopamine transporters implicates proximity of labeled domains. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:1157–64. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Husbands SM, Izenwasser S, Loeloff RJ, Katz JL, Bowen WD, Vilner BJ, et al. Isothiocyanate derivatives of 9-[3-(cis-3,5-dimethyl-1-piperazinyl)propyl]-carbazole (Rimcazole): irreversible ligands for the dopamine transporter. J Med Chem. 1997;40:4340–6. doi: 10.1021/jm9705519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zou MF, Kopajtic T, Katz JL, Wirtz S, Justice JBJ, Newman AH. Novel tropane-based irreversible ligands for the dopamine transporter. J Med Chem. 2001;44:4453–61. doi: 10.1021/jm0101904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carroll FI, Gao Y, Abraham P, Lewin AH, Lew R, Patel A, et al. Probes for the cocaine receptor: potentially irreversible ligands for the dopamine transporter. J Med Chem. 1992;35:1813–7. doi: 10.1021/jm00088a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimmel HL, Carroll FI, Kuhar MJ. RTI-76, an irreversible inhibitor of dopamine transporter binding, increases locomotor activity in the rat at high doses. Brain Res. 2001;897:157–63. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaughan RA, Sakrikar DA, Parnas ML, Adkins S, Foster JD, Duval RA, et al. Localization of cocaine analog [125I]RTI 82 irreversible binding to transmembrane domain 6 of the dopamine transporter. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:8915–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610633200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Husbands SM, Izenwasser S, Kopajtic T, Bowen WD, Vilner BJ, Katz JL, et al. Structure-activity relationships at the monoamine transporters and σ receptors for a novel series of 9-[3-(cis-3,5-dimethyl-1-piperazinyl)-propyl]carbazole (rimcazole) analogues. J Med Chem. 1999;42:4446–55. doi: 10.1021/jm9902943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bennett BA, Wichems CH, Hollingsworth CK, Davies HML, Thornley C, Sexton T, et al. Novel 2-substituted cocaine analogs: uptake and ligand binding studies at dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine transport sites in the rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272:1176–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D’Amato RJ, Largent BL, Snowman AM, Snyder SH. Selective labeling of serotonin uptake sites in rat brain by [3H]citalopram contrasted to labeling of multiple sites by [3H]imipramine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;242:364–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tejani-Butt SM. [3H]-Nisoxetine: a radioligand for quantitation of norepinephrine uptake sites by autoradiography or by homogenate binding. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;260:427–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vaughan RA, Agoston GE, Lever JR, Newman AH. Differential binding of tropane-based photoaffinity ligands on the dopamine transporter. J Neurosci. 1999;19:630–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00630.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reith MEA, Wang LC, Dutta AK. Pharmacological profile of radioligand binding to the norepinephrine transporter: instances of poor indication of functional activity. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;143:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.