Abstract

Theories of language production are monolingual but the world is multilingual. In the domain of word-form encoding, it is clear that languages rely differentially on different phonological units, challenging the generality of the monolingual theories. To address this, we propose the proximate units principle, which holds that the initial selection of sub-lexical phonological units (syllables, morae, phonemic segments, etc) is crucial both to understanding language specific processing, and to identifying what is language general in word production. We define proximate units and the role they play in speech planning and execution. The proximate units principle is consistent with much of what is already known about word form encoding across languages but also makes new predictions and can bring greater clarity to interpretations of experimental and speech error data.

Keywords: proximate units, word production, speech planning, phonology, cross-linguistic analysis

The Challenge of Generality

The two most widely endorsed models of word production, those of Dell and Levelt, are grounded in Germanic languages, English and Dutch respectively. These models agree that word production hinges on two primary kinds of units, words/morphemes themselves, and phonological segments or phonemes. By this we mean that words, or in some cases sublexical morphemes, are first selected, and then the phonological segments of these units are disbursed and linearized. Intermediate units such as syllables are either not represented at all in the retrieval of phonological ingredients (Levelt et al. 1999), or are only indirectly represented (Dell, 1986). In the Levelt et al model, syllabification is engendered during the linearization of phonemes. In the Dell model, syllable structure is represented in the structural frame that is retrieved with words and that guides linearization (see also Sevald, Dell & Cole, 1995). These models generalize quite well to other European languages, though there are some variations in detail, as reflected in speech error patterns, that remain to be explained (e.g., Perez et al., 2007). Our goal here is not to compare the Dell and Levelt models but rather to emphasize their common conclusion that words and segments are the key players in word form encoding. This conclusion is motivated, respectively, by the syllable paradox, the fact that in English syllable structure strongly constrains segmental errors but syllables do not themselves comprise error units (Dell 1986), and by the need for flexible assembly in languages that allow extensive resyllabification, that is, departures from citation forms in connected speech (Levelt et al., 1999).

Evidence from outside the Indo-European arena however suggests that the Dell and Levelt models do not generalize in their language-specific formats (see e.g., Chen and Dell, 2006; Cholin, Schiller & Levelt, 2004, for discussion). In Chinese languages, experimental and speech error evidence indicates that syllables are primary phonological units, that is, that they are explicitly selected in the first post-lexical step of full phonological encoding (Chen, Chen & Dell, 2002; Chen et al., 2009). Likewise, in Japanese, the mora, a unit smaller than the syllable but often comprising more than one segment, figures prominently in speech errors (Kubozono, 1989) and as a planning unit (Kureta, Fushimi & Tatsumi, 2006). These two examples are sufficient to suggest that the existing models do not generalize widely in their language-specific forms. To date, responses to this challenge have emphasized accommodation to the existing models (e.g., Chen et al 2002; Kureta et al., 2006). We suggest here that for this reconciliation to be satisfying it is necessary to develop models that are defined not in terms of specific units but in terms of their functions and relations. As a first step in this direction we propose the proximate units principle.

Proximate Units

Proximate units are the first explicitly selectable phonological production units below the level of the word or morpheme. These units vary cross-linguistically. Therefore, we propose the following proximate units principle: Planning and execution of word-form encoding is crucially dependent on the type of the proximate units in a language.

For this proposal to be substantive, proximate units must be clearly identifiable. We argue that they are indeed identifiable, both by their immediate relation to words, and because of their explicit status. This ease of identification is aided by the fact that in production, units do not merely subsist in an associative network, but must be coherently selected and sequenced in order for speech to be possible. Application of this strong constraint limits the viable accounts of phonological encoding to those that satisfy criteria that we elaborate in what follows. Variation in the type of proximate phonological unit has implications for the control of word production, and for the status of other units, most importantly phonemic segments in cases where they are nonproximate. These implications can be traced out in tasks that engage planning, in speech errors, in metalinguistic awareness, and in TOT states, among other contexts. We first outline these implications as corollaries of the proximate units principle, and then elaborate on actual and potential sources of evidence for our proposal under the headings of Form preparation, Speech errors, Advance planning, and Metalinguistic access.

Corollaries of the proximate units principle:

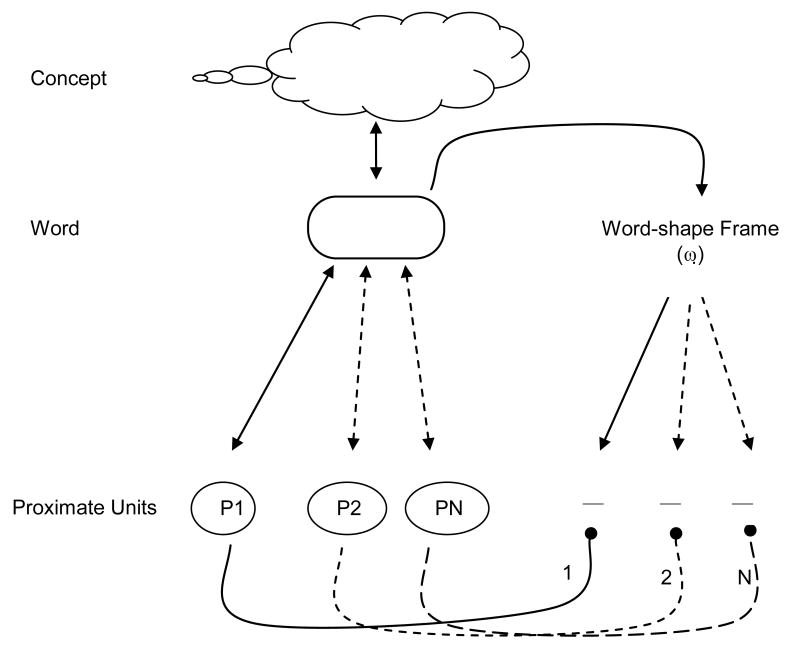

A word comprises one or more proximate phonological units that are retrieved simultaneously and linearized sequentially (e.g., Levelt et al., 1999; O'Seaghdha & Marin, 2000). See Figure 1.

Proximate units can thus be wholistically miss-selected. Table 1 summarizes evidence that proximate units feature prominently as speech errors, and just as importantly that non-proximate units – such as syllables in Germanic languages – do not.

The claim that syllables are not proximate units in some languages does not of course mean that they are unimportant. All accounts agree that syllabification is represented in the speech output of Indo-European languages. Syllables could be represented indirectly in the activation levels of subsyllabic components, or structurally (as in the original Dell, 1986, model), but neither of these would qualify syllables for proximate unit status. Likewise, the articulatory syllabary of the Levelt et al model involves hypothetical phonetic syllables that are engaged by corresponding assembled phonological syllables (Levelt et al., 1999; Cholin et al, 2004). By definition, such units are nonproximate.

Proximate units, as the first sublexical units that are selected during phonological encoding, will necessarily be manifest in automatic activation of phonology prior to selection (for example in masked presentation of words; Chen, Lin & Ferrand, 2003) or in advance phonological activation of downstream words (Dell and O'Seaghdha, 1992).

Additional steps are involved in segmental encoding of multi-segmental proximate units. For example, we have proposed for Mandarin that a secondary stage of segmental encoding follows selection and assignment of syllables (Chen et al., 2009; see also Chen et al., 2002).

Proximate units are meta-cognitively accessible, and may be default phonological components for linguistically naïve speakers. More specifically, proximate units are available left to right in imagined or covertly rehearsed speech. Thus the grain size of the most accessible phonological units, for example, what may be reported as a “word beginning”, is constrained by the proximate units of a language.

Likewise, other things being equal, proximate units will be salient in tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) states. English speakers often report the first segments of TOT words (e.g., Brown, 1991). In contrast, we hypothesize that Mandarin speakers are more likely to access whole syllables than segments in failed word retrieval; however, this may be difficult to test because retrieval of a whole syllable will tend to trigger release from the TOT state in a vocabulary that is dominated by disyllables. The prediction may be testable in Japanese where initial CV morae comprise a smaller portion of many complex words.

Figure 1. A Generic Model of Word Production.

When the word is scheduled for production, proximate units are retrieved in parallel and then selected sequentially by assignment to linear positions. Arrows signify flow of activation. Button terminals signify assignment of contents to structural positions. When the proximate units are suprasegmental, additional phonological processes are needed prior to articulation.

Table 1. Occurrence of Error Types as a Function of Language/Proximate Unit Combination.

| Language/Proximate Unit | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English/Phonemic segment | Mandarin/Syllable | Japanese/Mora | |

| Syllable errors | No | Yes | No |

| Mora errors | NA | NA | Yes |

| Segment errors | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Evidence

Form preparation

Evidence from form preparation experiments of cross-linguistic variation in the units that speakers prepare, has played a significant part in motivating the proximate units idea. In form preparation experiments, participants are given small sets of words that share a phonological component (homogeneous conditions: e.g., day dough dye dew) or do not (heterogeneous conditions: e.g., day pea rye sow). They then produce the items of the set in random order, repeatedly, under speeded instructions, in response to associative or direct cues. The dependent measure is naming time. Benefits of the shared component in the homogeneous conditions show that participants can cash in their foreknowledge of the shared component. In Germanic languages such as Dutch (Meyer, 1990, 1991; Roelofs 2006) and English (e.g., Damian & Bowers, 2003; Chen et al., 2009), speakers benefit from knowing the onsets of words, and there are further benefits of knowing additional contiguous segments. In contrast, Chen et al (2002) showed that whole syllables, but not the initial consonants of disyllables, showed benefits in Mandarin. Likewise, Kureta et al (2006) showed that Japanese speakers benefited from knowing the first morae of multi-moraic words (e.g., the /ta/ of ta.ba.ko) but not the initial consonants of the words.

In newer work, Chen et al (2009) tested extensively for initial consonant preparation in Mandarin. We considered that obliviousness to shared onsets could be inherent or alternatively a result of the need to sequence the syllables of complex words. On this basis, we tested simple monosyllables as well as disyllables, but found no benefit in either case. Thus even when the onsets were “there for the taking”, Taiwanese speakers of Mandarin did not benefit from homogeneity of onsets. In contrast, English speakers showed clear benefits with monosyllables of equivalent complexity (e.g., day, dough, dye, dew). Taken together the various findings constitute strong support for the proposal that proximate units are always available to form preparation, but that segmental components of larger proximate units are not.

Speech errors

Another hallmark of proximate units is their role in speech errors. Because proximate units are selected for sequencing, they have the potential to be miss-selected and so must appear as error units. According to the syllable paradox, whole syllable errors are extremely rare in English, whereas segmental errors, constrained by syllable position, are common (Dell, 1986). Whole syllable errors are well documented in Mandarin (Chen, 2000). For Japanese, Kubozono (1989) provides evidence that morae slip in speech errors. Kubozono's analysis does not exclude the possibility of syllable errors in Japanese, but these errors may instead be interpreted as multiple mora errors, just as multiple segment errors in English may or may not coincide with a syllable.

Segment errors also occur in Mandarin and Japanese, but they may have different distributions than in English. For Mandarin, we have proposed that segmental spell-out is delegated to syllables, such that after syllable selection (see Figure 1), the CV frame of the syllable and its ingredients are linked in an additional step. Because of their subordination to syllables in advance planning, the range of segment errors in Mandarin is predicted to be narrower than that of syllables, and also narrower than the range of segment errors in English. In addition:

Mandarin syllables may move between words (Chen, 2000)

Mandarin syllables may also be miss-selected within words (Chen, 2000; O'Seaghdha et al., 2009)

In Mandarin, segments may move between syllables within words as well as between words (Chen, 2000; O'Seaghdha et al 2009).

Advance Planning

The last claim about the ranges of syllabic and segmental errors in Mandarin raises the question of the activation of proximate units in advance planning of larger stretches of speech such as phrases and sentences. Because the majority of phonological errors occur within phrases, the range of immediately prearticulatory phonological planning may be limited to phrasal units. However, in situations where speakers plan whole sentences, there is evidence that while the subject phrase is being phonologically prepared ingredients of the object noun phrase are also phonologically active (e.g., Dell & O'Seaghdha, 1992). Even within a phrase of moderate complexity, words are sequentially selected so that phonological ingredients go from a waiting state of activation prior to selection, to a ready state where phonology is fully impleted prior to articulation. Languages such as Mandarin in which proximate syllable units differ from the segmental units called immediately prior to articulation thus have the potential to provide greater insight into the control of phonological encoding than languages like English where proximate and prearticulatory units are the same. For example, as noted already, because downstream phonology in Mandarin comes bundled in syllabic packages, longer range errors will tend to be syllabic, whereas near range errors will include more segmental slips. More speculatively, there is more time, opportunity, and perhaps need to preselect segments as well as syllables in more deliberative Mandarin speech. This predicts that the proportion of phonological segment errors in Mandarin will increase relative to syllable errors when speech is more deliberative, although the overall error rate will of course decline. In contrast, reduced speech rate predicts a simple reduction in phonological segment errors in English (see Dell, Burger & Svec, 1997). This hypothesis illustrates how variation in proximate unit deployment across languages may be used to refine our understanding of the time-course of phonological encoding.

Metalinguistic access

Finally, we consider the closely related issue of how linguistic variation in proximate units impacts phonological awareness.

Consider first the status in form preparation. Here, one may intuit that an English speaker who knows that all words in a set begin with a particular consonant is metalinguistically aware of that fact, and is therefore able to deploy the corresponding segment. This in turn saves time in producing the homogeneous words. In contrast, it is far less clear what a Mandarin speaker who knows a word begins with a certain syllable can deploy.

A recent study by Oppenheim and Dell (2007) suggests that the nature of the prepared content is not as obvious as it may seem even in English. Oppenheim and Dell tested for slips of the tongue in inner speech and found that in contrast to overt speech, there was no phonological similarity effect. One may conclude from this that phonemes but not subphonemic features are activated in inner speech. Because form preparation is non-overt, one may assume that preparation likewise does not fully engage subphonemic features. But in that case, it follows that preparation of a syllable in Mandarin or of a mora in Japanese is even more abstract, and may not extend to the phonemic level. Indeed the absence of onset preparation benefits in Mandarin and Japanese appears to suggest just this. Moreover, for Mandarin, syllables must be specified for tone before they are spoken, and so, when the tone is variable, syllable preparation cannot be phonetic. Taken together, these observations raise new questions about the representation of prepared units in form preparation and other contexts. They suggest that it is possible to image or prefigure proximate units without fully specifying their content.

Navigating between proximate unit systems

The evidence that languages vary substantially in the configuration of sublexical phonological units has implications for second language learning. Second language learners therefore may provide important insights into the fundamental processes of word encoding. For example, the prominence of syllables in Mandarin depends on systematic properties of the language and cannot be transferred wholesale to English. Thus, Mandarin learners of English are obliged to adopt a segmental proximate mode. In a recent study (O'Seaghdha et al, 2009), we asked whether experience in English influenced the bilinguals' Mandarin word production in circumstances where the English mode is applicable.

We tested Mandarin-English bilinguals of varying fluency in a Mandarin form preparation experiment. Recall that monolingual Mandarin speakers do not show any onset benefit. For bilinguals, in contrast, we found a clear onset benefit suggesting that the English mode was engaged. Interestingly, the benefit was shown even by less proficient speakers and did not vary with English fluency level. This raises an important theoretical question concerning proximate units. One logical possibility is that the word production architecture is highly adaptable allowing for a shift from the syllabic to the segmental level in these bilinguals. Alternatively, the adaptation shown in our study is task specific and does not indicate substantial alteration of the overall Mandarin-specific regulation of phonological encoding. In the form preparation task, knowledge of English provides an analog that allows these speakers to direct attention to phonological onsets. But in fully fledged speech, the demands of fluent communication may preclude such flexibility. Instead, the proximate syllabic units will manifest themselves in speech errors, and other measures, just as they do for monolingual speakers. Likewise, we hypothesize that monolinguals and bilinguals will not differ in single word masked priming where metacognitive awareness is not engaged.

Conclusion

The proximate units principle points to a fertile seam of investigation in the cross-linguistic analysis of word production and suggests a way to preserve language-general theories in the face of linguistic diversity. These investigations address not only immediate processes of individual word production, but coordination of sentence meaning and form in advance planning of speech, interpretation of cross-linguistic speech error patterns, and the mental representation of planned units.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIDCD grant R01DC006948 and by the National Science Council of Taiwan. We thank Train-Min Chen, Alexandra Frazer, Jordan Knicely, and Kuan-Hung Liu for contributions to this project.

Contributor Information

Padraig G O'Seaghdha, Email: pat.oseaghdha@lehigh.edu, Department of Psychology, Lehigh University, USA.

Jenn-Yeu Chen, Email: psyjyc@mail.ncku.edu.tw, Institute of Cognitive Science, National Cheng Kung University, TAIWAN.

References

- Brown AS. A review of the tip-of-the-tongue experience. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;109:204–223. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY. Syllable errors from naturalistic slips of the tongue in Mandarin Chinese. Psychologia: An International Journal of Psychology in the Orient Special Issue: Cognitive processing of the Japanese and Chinese languages II. 2000;43:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, Chen TM, Dell GS. Word-form encoding in Mandarin Chinese as assessed by the implicit priming task. Journal of Memory & Language. 2002;46:751–781. [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, Lin WC, Ferrand L. Masked priming of the syllable in Chinese speech production. Chinese Journal of Psychology. 2003;45:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, Dell GS. Word form encoding in Chinese speech production. In: Li P, et al., editors. The Handbook of East Asian Psycholinguitics Vol 1: Chinese. Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, O'Seaghdha PG, Chen TM, Liu KH. Control of word production: Word form preparation addresses syllables in Mandarin but segments in English. 2009 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Cholin J, Schiller NO, Levelt WJM. The preparation of syllables in speech production. Journal of Memory and Language. 2004;50:47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Damian MF, Bowers JS. Effects of orthography on speech production in a form-preparation paradigm. Journal of Memory and Language. 2003;49:119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Dell GS. A spreading-activation theory of retrieval in sentence production. Psychological Review. 1986;93:283–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell GS, Burger LK, Svec WR. Language production and serial order: A functional analysis and a model. Psychological Review. 1997;104:123–147. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.104.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell GS, O'Seaghdha PG. Stages of lexical access in language production. Cognition. 1992;42:287–314. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(92)90046-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer AK, Knicely JL, O'Seaghdha PG. Expect the unexpected: Robust planning processes in speech production. Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society.2009. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- Kubozono H. The mora and syllable structure in Japanese: Evidence from speech errors. Language and Speech. 1989;32:249–278. [Google Scholar]

- Kureta Y, Fushimi T, Tatsumi IF. The functional unit of phonological encoding: Evidence for moraic representation in native Japanese speakers. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition. 2006;32:1102–1119. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.32.5.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levelt WJM, Roelofs A, Meyer AS. A theory of lexical access in speech production. Behavioral & Brain Sciences. 1999;22:1–75. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99001776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AS. The time course of phonological encoding in language production: The encoding of successive syllables of a word. Journal of Memory & Language. 1990;29:524–545. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AS. The time course of phonological encoding in language production: Phonological encoding inside a syllable. Journal of Memory & Language. 1991;30:69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim GM, Dell GS. Inner speech slips exhibit lexical bias, but not the phonemic similarity effect. Cognition. 2008;106:528–537. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Seaghdha PG, Marin JW. Phonological competition and cooperation in form-related priming: Sequential and nonsequential processes in word production. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance. 2000;26:57–73. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.26.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Seaghdha PG, Wang Y, Schuster K. Syllables actuate word production in Mandarin Chinese but not in English. 2009 Manuscript under revision. [Google Scholar]

- O'Seaghdha PG, Chen JY, Chen TM, Su JJ. Word production in Chinese-English bilinguals exhibits an L2-to-L1 influence. Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Psychological Science.2009. May, [Google Scholar]

- Pérez E, Santiago J, Palma A, O'Seaghdha PG. Perceptual bias in speech error data collection: Insights from Spanish speech errors. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 2007;36:207–235. doi: 10.1007/s10936-006-9042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelofs A. Phonological segments and features as planning units in speech production. Language & Cognitive Processes. 1999;14:173–200. [Google Scholar]

- Roelofs A. The influence of spelling on phonological encoding in word reading, object naming, and word generation. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2006;13:33–37. doi: 10.3758/bf03193809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevald CA, Dell GS, Cole J. Syllable structure in speech production: Are syllables chunks or schemas? Journal of Memory & Language. 1995;34:807–820. [Google Scholar]