Abstract

Oocytes segregate chromosomes in the absence of centrosomes. In this situation, the chromosomes direct spindle assembly. It is still unclear in this system which factors are required for homologous chromosome bi-orientation and spindle assembly. The Drosophila kinesin-6 protein Subito, although nonessential for mitotic spindle assembly, is required to organize a bipolar meiotic spindle and chromosome bi-orientation in oocytes. Along with the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC), Subito is an important part of the metaphase I central spindle. In this study we have conducted genetic screens to identify genes that interact with subito or the CPC component Incenp. In addition, the meiotic mutant phenotype for some of the genes identified in these screens were characterized. We show, in part through the use of a heat-shock-inducible system, that the Centralspindlin component RacGAP50C and downstream regulators of cytokinesis Rho1, Sticky, and RhoGEF2 are required for homologous chromosome bi-orientation in metaphase I oocytes. This suggests a novel function for proteins normally involved in mitotic cell division in the regulation of microtubule–chromosome interactions. We also show that the kinetochore protein, Polo kinase, is required for maintaining chromosome alignment and spindle organization in metaphase I oocytes. In combination our results support a model where the meiotic central spindle and associated proteins are essential for acentrosomal chromosome segregation.

Keywords: meiosis, synthetic lethal mutation, homolog bi-orientation, spindle, chromosome segregation, Drosophila

CHROMOSOMES are segregated during cell division by the spindle, a bipolar array of microtubules. In somatic cells, spindle assembly is guided by the presence of centrosomes at the poles. In this conventional spindle assembly model, the kinetochores attach to microtubules from opposing centrosomes and tension is established. This satisfies the spindle assembly checkpoint, which then allows the cell to proceed to anaphase (Musacchio and Salmon 2007). Cell division is completed by recruiting proteins to a midzone of antiparallel microtubules that forms between the segregated chromosomes, signaling furrow formation (Fededa and Gerlich 2012; D’Avino et al. 2015). However, spindle morphogenesis in oocytes of many animals occurs in the absence of centrosomes. This may contribute to the high rates of segregation errors that are maternal in origin and are a leading cause of miscarriages, birth defects, and infertility (Herbert et al. 2015). How a robust spindle assembles without guidance from the centrosomes is not well understood. While it is clear that the chromosomes can recruit microtubules and drive spindle assembly (Tseng et al. 2010; Dumont and Desai 2012), how a bipolar spindle is organized and chromosomes make the correct attachments to microtubules is not understood.

The Drosophila oocyte provides a genetically tractable system for the identification of genes involved in acentrosomal spindle assembly. Substantial evidence in Drosophila suggests that the chromosomes direct microtubule assembly, subsequent elongation of the spindle, and establishment of spindle bipolarity (Theurkauf and Hawley 1992; Matthies et al. 1996; Doubilet and McKim 2007). We have also shown that the kinesin-6 protein Subito, a homolog of human MKLP2 with a role in cytokinesis (Neef et al. 2003), is also essential for organizing the meiotic spindle and the bi-orientation of homologous chromosomes (Giunta et al. 2002; Jang et al. 2005; Radford et al. 2012). Subito colocalizes with members of the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC), which is composed of the scaffolding subunit INCENP, the kinase Aurora B, and the targeting subunits Survivin (Deterin) and Borealin (Dasra) (Ruchaud et al. 2007). The CPC has a critical role in assembling the acentrosomal spindle and segregating chromosomes (Colombié et al. 2008; Radford et al. 2012). In addition, with Subito, the CPC localizes to the equatorial region of the meiotic metaphase I spindle and are mutually dependent for their localization (Jang et al. 2005; Radford et al. 2012). This equatorial region is composed of antiparallel microtubules and is a structure that includes a plethora of proteins (Jang et al. 2005). Assembling a central microtubule array may be a conserved mechanism to organize a bipolar spindle in the absence of centrosomes (Dumont and Desai 2012).

The meiotic central spindle, while assembling during metaphase, has several features and proteins associated with the midzone present during anaphase in mitosis. Indeed, Subito is required for the localization of the CPC to the midzone at anaphase (Cesario et al. 2006). The mitotic spindle midzone proteins function in anaphase and telophase to direct abscission, furrow formation, and cytokinesis (Glotzer 2005; D’Avino et al. 2015). The role of these proteins in the Drosophila acentrosomal meiotic spindle assembly pathway is unclear, however, since there is no cytokinetic function required at metaphase I and Drosophila does not extrude polar bodies (Callaini and Riparbelli 1996). It is possible that these proteins are loaded in the central spindle at metaphase for a function later in meiotic anaphase, as has been proposed for Centrosomin (Riparbelli and Callaini 2005). Alternatively, these central spindle proteins could be adapted for a new role, like Subito, in spindle assembly and/or bi-orientation of homologous chromosomes.

To identify and study the function of meiotic central spindle proteins, we carried out screens for genes that interact with subito (sub) and the CPC component Incenp. First, an enhancer screen was performed for mutations that are synthetically lethal with sub. Second, since synthetic lethality is a mitotic phenotype, a screen was performed for enhancement of the meiotic nondisjunction phenotype caused by a transgene overexpressing an epitope-tagged Incenp (Radford et al. 2012). In these screens we identified new mutations in CPC components (Incenp, aurB, borr), the Centralspindlin gene tumbleweed (tum), and the transcription factor snail. Mutations in at least 16 additional loci were also identified, and we directly tested candidate mitotic central spindle proteins for functions in meiosis. Several proteins were found to be required for microtubule organization and homologous chromosome bi-orientation during metaphase of meiosis I, including proteins in the Rho-GTP-signaling pathway required for cytokinesis such as TUM (RacGAP50C), Rho1, Sticky (Citron kinase homolog), and RhoGEF2. Not all mitotic midzone proteins are required for the meiotic central spindle, however, demonstrating meiosis-specific features of this structure. For example, Polo kinase may be required only for kinetochore function while the RhoGEF Pebble was not required for meiosis. In summary, this is the first documentation that proteins known to be required for anaphase/telophase and cytokinesis in mitotic cells are also essential in meiotic acentrosomal spindle assembly and chromosome bi-orientation.

Materials and Methods

Deficiency and mutagenesis screens for synthetic lethality

To test synthetic lethality of third chromosome mutations and deficiencies, cn sub bw/CyO; e/ TM3, Sb females were crossed to Df/TM3, Sb females (Supporting Information, Figure S1). The cn sub bw/ +; Df/TM3 males were then crossed to sub bw/CyO or cn sub/CyO females to generate cn sub bw/sub bw; Df/+ progeny. The frequency of these progeny was compared to cn sub bw/sub bw; TM3/+ siblings to measure the synthetic lethal phenotype as a percentage of relative survival.

The mutagenesis screen was performed for the second chromosome using ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS). y/y+Y; sub131 bw sp/SM6 males were exposed to 2.5 mM EMS in 1% sucrose overnight. About 25 mutagenized males were mated to 50 al dp b pr Sp bw/SM6 virgin females (Figure S2). Single sub131 bw sp*/SM6 (asterisk denotes random mutations) males were mated with virgin cn sub1 bw/SM6 females, and the progeny were scored for the absence of brown-eyed flies, which indicates a synthetic lethal interaction between the heterozygous EMS-induced mutation and the sub mutant. Initially, 51 synthetic lethal lines were isolated. Each line was retested twice by crossing sub131 bw sp*/SM6a sibling male progeny to cn sub1bw/SM6a females and examining again for brown-eyed progeny. Eventually 19 lines carrying a synthetic lethal mutation (sub131 bw sp*/SM6a) were established and used for complementation testing and mapping.

Genetics, mapping, and complementation testing

To generate recombinant chromosomes for mapping or to remove the sub131 allele, we mated sub131 bw sp*/SM6a males to al dp b pr cn c px sp/CyO virgin females, collected sub131 bw sp*/al d b pr cn c px sp virgin females, and mated them to al dp b pr Bl cn c px sp/CyO males. Recombinants that were al− and c+ were collected and, because these recombinants likely carried the sub mutant allele, were tested for synthetic lethality. In contrast, recombinants that retained the c mutation likely did not carry the sub mutant allele. These were used to evaluate whether the synthetic lethal mutation had a recessive lethal phenotype.

For establishing complementation groups, sub131 bw sp*/SM6a flies were crossed to c px sp*/CyO flies. A failure to complement was established by the absence of straight-winged (Cy+) progeny with a total of at least a hundred flies being scored. For some mutations we used deficiency mapping. Three deficiencies—Df(2L)r10, Df(2L)osp29, and Df(2L)Sco[rv14]—failed to complement 22.64 and 27.18. The allele of snail used for complementation was sna1. One deficiency, Df(2R)Exel7128, failed to complement 15.173 and 16.135. The alleles of tum used for complementation were tumAR2 and tumDH15.

X-chromosome nondisjunction was measured by crossing females to y Hw w /BSY males. The Y chromosome carries a dominant Bar allele such that XX and XY progeny are phenotypically distinguishable from exceptional XXY and XO progeny that received two or no X chromosomes from their female parent. Nullo-X and triplo-X progeny are inviable, which is compensated in nondisjunction calculations by doubling the number of XXY and XO progeny.

Generating germline clones by FLP-FRT

Males of the genotype w/Y; ovoD FRT40A/CyO were mated to y w hsFLP70; Sco/CyO virgins, and y w hsFLP70;ovoD FRT40A/CyO males were selected from the progeny. These were mated to either 22.64 pr FRT40A/CyO (or 27.89) virgins for the experiment or b pr FRT40A/CyO virgins for the control (Chou and Perrimon 1996). Third instar larval progeny from these crosses were heat-shocked at 37° for 1 hr on the fourth day. Female progeny of the genotypes y w hsFLP; ovoD FRT40A/ 22.64 FRT40A and y w hsFLP; ovoD FRT40A/ b pr FRT40A were yeasted for 3–4 days, and stage 14 oocytes were collected and analyzed.

Sequencing

DNA was extracted from a single fly (Gloor et al. 1993) and amplified using standard polymerase chain reaction. The gene of interest was amplified using specific primer sets spanning the length of the gene. This DNA was then sent for sequencing to Genewiz Inc. Since the stocks were balanced, the resulting sequence was analyzed using Align-X (Invitrogen) and Snapgene software for the presence of heterozygous SNPs indicating possible EMS-induced mutations.

Expression of RNAi in oocytes and quantification

Expression of short hairpin RNA lines designed and made by the Transgenic RNAi Project at Harvard (TRiP) was induced by crossing each RNAi line to either P{w+mC = tubP-GAL4}LL7 for ubiquitous expression or P{w+mC = matalpha4-GAL-VP16}V37 for germline-specific and oocyte expression (referred to as “drivers”). The latter is expressed throughout oogenesis starting late in the germarium (Radford et al. 2012). For expression of tum RNAi we used P{GAL4-Hsp70.PB}89-2-1. In this method, 2-day-old adult females were yeasted for 2 days with males and then heat-shocked for 2 hr at 37°. They were allowed to recover for 3 1/2 hr, and then oocytes were collected and fixed. At this time point the oocytes that were at approximately stages 10–11 at the time of heat shock were being laid as mature oocytes. Later time points did not yield sufficient quantities of oocytes in the tum RNAi as oogenesis had arrested by then. tum RNAi females were sterile for 72 hr after heat shock whereas wild type regained fertility soon after heat shock.

For reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR, total RNA was extracted from late-stage oocytes using TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was consequently prepared using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). The qPCR was performed in either a StepOnePlus (Life Technologies) or Eco (Illumina) real-time PCR system using the following TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Life Technologies): Dm01823196_g1 (polo), Dm01794608_m1 (Rho1), Dm018202757_g1 (sticky), Dm01794707_m1, (RhoGEF2), and Dm01822327_g1 (pebble).

Antibodies and immunofluorescent microscopy

Stage 14 oocytes were collected from 50 to 200, 3- to 4-day-old yeast-fed nonvirgin females by physical disruption in a common household blender in modified Robb’s media (Theurkauf and Hawley 1992; McKim et al. 2009). The oocytes were fixed in either 100 mM cacodylate/8% formaldehyde fixative for 8 min or 5% formaldehyde/heptane fixative for 2.5 min and then their chorion and vitelline membranes were removed by rolling the oocytes between the frosted part of a slide and a coverslip (McKim et al. 2009). For FISH, oocytes were prepared as described (Radford et al. 2012). Oocytes and embryos were stained for DNA with Hoechst 33342 (10 µg/ml) and for microtubules with mouse anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody DM1A (1:50), directly conjugated to FITC (Sigma, St. Louis) or rat anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (1:75) (Millipore). Additional primary antibodies were rat anti-Subito antibody (used at 1:75) (Jang et al. 2005), rat anti-INCENP (1:400) (Radford et al. 2012), rabbit anti-TUM (1:50) (Zavortink et al. 2005), rabbit anti-SPC105R (1:4000) (Schittenhelm et al. 2007), rabbit anti-Sticky (1:50) (D’Avino et al. 2004), and mouse monoclonal anti-Rho1 (P1D9, 1:50) (Magie et al. 2002). These primary antibodies were combined with either a Cy3 or Cy5 secondary antibody pre-absorbed against a range of mammalian serum proteins (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). FISH probes used were the AACAC repeat (second chromosome) and dodeca repeat (third chromosome). Oocytes were mounted in SlowFade gold (Invitrogen). Images were collected on a Leica TCS SP5 or SP8 confocal microscope with a 63×, numerical aperture 1.4 lens. Images are shown as maximum projections of complete image stacks followed by merging of individual channels and cropping in Adobe Photoshop (PS6).

Results

sub mutants interact with multiple third chromosome loci including Deterin (Survivin) and pavarotti (MKLP1)

Null mutants of sub are viable but female sterile (Giunta et al. 2002). CPC members INCENP and Aurora B are mislocalized in the larval neuroblasts of sub mutants, which may be the reason why a reduction of INCENP or Aurora B dosage by 50% causes sub homozygotes to die (Cesario et al. 2006). This observation suggests that the sub mutant is a sensitized genetic background in which to perform forward genetic screens to identify mitotic proteins with possible functions in meiosis similar to the CPC or Subito. Thus, we performed screens for mutations that show a dominant lethal interaction with sub, also known as “synthetic lethality” (Figure S1 and Figure S2). The advantage of these screens is that we can recover mutations in essential genes and identify genes encoding central spindle proteins even if there is no direct physical interaction.

On the third chromosome we screened 81 deficiencies obtained from Bloomington Stock Center for synthetic lethality, covering ∼75% of the chromosome. Synthetic lethality was calculated as a ratio of sub1/sub131;Df/+ to sub1/sub131;+/+ progeny. Seven deficiencies—Df(3L)ZN47, Df(3R)23D1, Df(3R)DG2, Df(3L)rdgC-co2, Df(3L)GN24, Df(3R)Exel9014, and Df(3L)ri-XT1—that displayed synthetic lethal interaction with sub at viability rates between 0–10% were identified (Table 1). Three additional deficiencies—Df(3R)Antp17, Df(3L)emc-E12, and Df(3R)BSC43—exhibited a milder synthetic lethal interaction with a viability rate between 10 and 30% (Table 1).

Table 1. Deficiencies that are synthetic lethal with sub and/or dominantly enhance Incenpmyc.

| Deficiency | Cytology | Viabilitya | Totala | % X-nondisjunctionb | Totalb | Candidate genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sub | 20.3 | 1438 | ||||

| + | 1.3 | 158 | ||||

| Df(3L)emc-E12 | 61A;61D3 | 30.1 | 272 | 22.6 | 257 | fwd |

| Df(3L)ED4177 | 61C1;61E2 | 67.0 | 309 | 2.6 | 1440 | fwd |

| Df(3L)GN24 | 63F6-63F7;64C8-64C9 | 0 | 118 | 1.2 | 1027 | pavarotti |

| Df(3L)Exel9000 | 64A10;64A12 | 30.1 | 359 | 5.3 | 219 | pavarotti |

| Df(3L)ZN47 | 64C4-64C6;65D2 | 0 | 98 | 2.1 | 391 | Mad2, RCC1 |

| Df(3L)rdgC-co2 | 77A1;77D1 | 7.3 | 191 | polo | ||

| Df(3L)ri-XT1 | 77E2-77E4;78A2-78A4 | 6.1 | 70 | 12.2 | 460 | Spc105R, pitsire |

| Df(3L)BSC452 | 77E1;77F1 | 39 | 163 | 13.1 | 565 | |

| Df(3L)BSC449 | 77F2;78C2 | 122 | 180 | 4.8 | 565 | |

| Df(3R)Antp17 | 84A1-84A5;84D9 | 16.7 | 28 | |||

| Df(3R)DG2 | 89E1-89F4;91B1-91B2 | 0 | 36 | 0.0 | 297 | Deterin |

| Df(3R)ED5780 | 89E11;90C1 | 8.7 | 577 | |||

| Df(3R)BSC43 | 92F7;93B6 | 10.1 | 89 | 0.0 | 439 | |

| Df(3R)23D1 | 94A3-94A4;94D1-94D4 | 0 | 175 | 6.1 | 457 | |

| Df(3R)Exel6191 | 94A6;94B2 | 113.3 | 224 | 3.8 | 311 | |

| Df(3R)Exel6273 | 94B2;94B11 | 112.3 | 155 | 4.5 | 532 | |

| Df(3R)ED6091 | 94B5;94C4 | 158.1 | 191 | 0.0 | 156 | |

| Df(3R)Exel6192 | 94B11;94D3 | 111.1 | 133 | 6.0 | 807 | ND |

| Df(3R)Exel9013 | 95B1;95B5 | 132.8 | 288 | 8.4 | 1197 | ND |

| Df(3R)Exel9014 | 95B1;95D1 | 0 | 49 | 11.1 | 2234 | ND |

| Df(3R)Exel6196 | 95C12;95D8 | 140.6 | 77 | 6.5 | 2043 | ND |

Percentage viability was calculated from the ratio of sub131/sub1;Df/+::sub131/sub1;+/+ flies obtained (Figure S2).

X-chromosome nondisjunction was measured by crossing females to y Hw w/BSY males (Materials and Methods).

For each of the seven deficiencies with the strongest synthetic lethal phenotype, we looked at sets of overlapping deficiencies and specific mutations to identify candidate genes. Df(3R)DG2 uncovers the gene Deterin (also known as survivin), which we expect to be synthetic lethal with sub similar to the other members of the CPC. A null allele of Deterin was tested and also exhibited a synthetic lethal interaction (4% sub1/sub131;Dete01527/+ progeny; n = 184). Deficiency Df(3L)rdgC-co2 uncovers polo, which we expected to be synthetic lethal based on previous results (Cesario et al. 2006). Within Df(3L)GN24 we tested six smaller deficiencies and found synthetic lethality with Df(3L)Exel9000. Within this deficiency is pavarotti, which encodes the Drosophila homolog of MKLP1 that localizes to the central spindle in both mitosis and meiosis similar to Subito (Adams et al. 1998; Minestrini et al. 2003; Jang et al. 2005). A null allele of pavarotti also was synthetic lethal with sub (0% sub1/sub131; pavB200/+ progeny; n = 69).

Two of the deficiencies identified as synthetic lethal with sub, Df(3R)Exel9014, and Df(3L)ri-XT1 disrupt the kinetochore protein-encoding gene Spc105R (Table 1). Df(3R)Exel9014 does not delete Spc105R, but the chromosome carries a second mutation that is a null allele, Spc105R1 (Schittenhelm et al. 2009). One of two smaller deficiencies within Df(3L)ri-XT1, Df(3L)BSC452, also deletes Spc105R and has a synthetic lethal phenotype. We directly tested synthetic lethality with a Spc105R1 chromosome that lacked Df(3R)Exel9014. Spc105R1 on its own was not synthetic lethal with sub (n = 253). We also tested two additional kinetochore mutants, but neither mis12 (n = 337) nor spc25 (n = 131) were synthetic lethal with sub. These results suggest that there is no synthetic lethal interaction between sub and kinetochore mutants. Df(3R)Exel9014 and Df(3L)ri-XT1 must interact with sub because of loci other than Spc105R.

For two of the deficiencies, Df(3L)ZN47 and Df(3R)23D1, we did not identify a smaller interacting region. It is possible that the interaction lies in a gene disrupted only by the larger deficiency. Alternatively, the genetic interaction may involve haploinsufficiency for more than one gene within the larger deficiency. There are also possibly more complex interactions of positive and negative regulators. In this case, a smaller deficiency could have a less severe synthetic lethal phenotype than a point mutant. This was observed with deletions of pav. While a pav mutation and Df(3L)GN24 had severe synthetic lethal phenotypes, the smaller deficiency Df(3L)Exel9000 had a relatively mild synthetic lethal phenotype.

Overall, in addition to confirming genetic interactions between sub and polo, pav or Det, the third chromosome deficiency screen for synthetic lethality identified at least seven additional interacting loci.

Mutagenesis screen for synthetic lethal mutants on the second chromosome reveals new alleles of CPC genes and centralspindlin component Tumbleweed

A mutagenesis screen of the second chromosome was done to identify genes that genetically interact with sub. We screened 5314 second chromosomes mutagenized with EMS and isolated 19 lines with a synthetic lethal phenotype (Materials and Methods) (Figure S2). We expected to obtain alleles of the CPC since three of its members—Incenp, aurB, and borr—are on the second chromosome. Complementation testing with deficiencies uncovering these genes and existing mutants revealed three alleles of Incenp, two of aurB, and one of borr (Table 2). Most of these mutations were also homozygous lethal. However, Incenp18.197 is a hypomorphic allele that causes recessive sterility and not lethality. The rest of the mutations were put into 11 complementation groups. There are 2 groups with two alleles each (22.64, 27.18 and 15.173, 16.135) and 9 that are represented by one allele each (Table 2).

Table 2. Mutations obtained from EMS screen of the second chromosome.

| Complementation groups | Mutant localization | Allele | Phenotypea | Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incenp | 43A2-43A3 | 22.68 | Lethal | Q611-Stop |

| 47.125 | Lethal | ND | ||

| 18.197 | ♀ Sterile | P746L | ||

| aurB | 32B2 | 35.33 | Lethal | L166F |

| 49.149 | Lethal | Q95-Stop | ||

| borr | 44.356 | Lethal | Lost | |

| snail | 35D2 | 22.64 | Lethal | ND |

| 27.18 | Lethal | Q275-Stop | ||

| tumbleweed | 50C6 | 15.173 | Lethal | P463L |

| 16.135 | Lethal | ND | ||

| 6 | 31B1-32D1 | 27.89 | Lethal | |

| 7 | 34D1-43E16 | 27.88 | viable | |

| 8 | ND | 48.116 | Lethal | |

| 9 | 25A2 – 34D1 | 44.13 | Lethal | |

| 10 | ND | 46.10 | Lethal | |

| 11 | ND | 47.90 | ND | |

| 12 | ND | 47.134 | ND | Lost |

| 13 | ND | 49.178 | ND | Lost |

| 14 | ND | 10.33 | ND |

Based on phenotype of recombinant chromosome lacking the subito mutation.

Some synthetic lethal mutations that complemented all CPC mutants were genetically mapped (Table 2). We picked two types of recombinants—those that also retained the sub mutation so that the synthetic lethal mutation could be mapped and those that did not have the sub mutation—to determine if the mutation had a recessive phenotype, such as lethality or sterility. A detailed example of this approach is described in File S1 for the synthetic lethal mutation 27.89.

Mutation 27.89 was mapped between dp and b on chromosome 2R. Using SNP mapping, the synthetic lethal mutation was mapped to a 300-kb region (File S1, Figure S3, and Figure S4). Surprisingly, it is possible that 27.89 is homozygous lethal but viable when heterozygous to a deficiency (Figure S5), although we have not excluded a second lethal mutation on the 27.89 chromosome. To examine if 27.89 has a germline phenotype, we generated germline clones to collect 27.89 homozygous oocytes to determine if there was an effect on meiosis. In fact, homozygous 27.89 germline clones failed to develop into mature oocytes. This inability to generate mature germline clones is a phenotype shared by other mutations isolated in the screen such as Incenp, aurB, and tumbleweed, which are involved in the early mitotic cell divisions that occur pre-oogenesis. This indicates that 27.89 may play a role in cell division.

Mutation 22.64 was mapped to the interval between b and pr and, based on complementation to deficiencies, we found that 22.64 and 27.18 failed to complement existing alleles of snail, which encodes a zinc finger containing a transcriptional repressor (Ashraf et al. 1999; Ashraf and Ip 2001). This was a surprising finding because snail has not previously been shown to regulate spindle assembly. An analysis of mature oocytes using germline clones has revealed that snail mutants do not grossly affect meiotic spindle assembly (Figure S6). Further work is necessary to address why snail mutations enhance the sub mutant phenotype and if snail has a role in meiotic or mitotic spindle function. Interestingly, a Drosophila paralog of Snail, Worniu, has been shown to regulate cell cycle progression in neuroblasts (Lai et al. 2012).

Both 15.173 and 16.135 genetically mapped to a region on chromosome 2R between cn and c and failed to complement a deficiency in this region, Df(2R)Exel7128. Based on this mapping, we found that both mutations failed to complement existing alleles of tum, which encodes the Drosophila homolog of RacGAP50C (Goldstein et al. 2005). RacGAP50C is a Centralspindlin component that, as described earlier, also includes Pavarotti. Thus, all known members of two complexes, the CPC and Centralspindlin, genetically interact with sub. This is consistent with previous observations that Subito, Incenp, and RacGAP50C colocalize at the central spindle during mitosis (Cesario et al. 2006) and meiosis (Jang et al. 2005). Below are the results from analyzing the meiotic phenotype of oocytes depleted for RacGAP50C.

Mutations that enhance the dominant meiotic chromosome segregation phenotype of an Incenp allele

While the synthetic lethal screens revealed genes that interact with sub, these genes may not function in meiosis. To test interacting genes for a function in meiosis, we determined if they enhanced the nondisjunction phenotype of a transgene expressing the CPC member Incenp tagged with the myc epitope at its N terminus (UASP:Incenpmyc). Females expressing UASP:Incenpmyc with nos-GAL4:VP16 in addition to the endogenous alleles show ∼1% X-chromosome nondisjunction. Females also heterozygous for a null allele of sub show ∼20% X-chromosome nondisjunction (Radford et al. 2012) (Table 1). It is not known if the phenotype arises from the N-terminal tag or overexpression of Incenp. We used UASP:Incenpmyc to screen for mutations that dominantly enhance the nondisjunction phenotype, similar to sub.

We tested deficiencies that showed a synthetic lethal interaction with sub (Table 1). Using a cutoff for enhancement of 4% increase over the control, 10 deficiencies showed an increase in nondisjunction ranging from 5 to 19% over control levels (Table 3). This assay appears to be more sensitive than the synthetic lethal phenotype for detecting interactions. For example, the strong nondisjunction phenotype of Df(3L)emc-E12 contrasts with the mild synthetic lethal phenotype. Similarly, while Df(3R)BSC452 had a milder synthetic lethal phenotype than the larger Df(3R)ri-XT1, it had a similar nondisjunction phenotype with UASP:Incenpmyc. Taking into account that some of these deficiencies overlap, these experiments identified at least six loci that genetically interact with UASP:Incenpmyc. These results suggest that some of the deficiencies identified as synthetic lethal also have at least one gene required for meiotic chromosome segregation.

Table 3. Frequency of mono-orientation in oocyte knockouts of central spindle proteins.

| Genotype | AACAC % mono-orientation (n)a | DODECA % mono-orientation (n)b | P-valuec (AACAC) | P-valuec (DODECA) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 4 (2) | 0 | NA | NA | 45 |

| Wild type (HS)d | 5.5 (1) | 5.5 (1) | NA | NA | 18 |

| tum HMS01417 (HS)d | 50 (10) | 45 (9) | 0.004 | 0.009 | 20 |

| Rho1 HMS00375 | 35 (9) | 15 (4) | 0.001 | 0.019 | 26 |

| sticky GL00312 | 27 (6) | 18 (4) | 0.013 | 0.015 | 22 |

| RhoGEF2 HMS01118 | 20 (5) | 13 (3) | 0.045 | 0.039 | 24 |

| pbl GL01092 | 0 | 0 | NS | NS | 15 |

| polo GL00014 | 61.9 (13) | 47.6 (10) | 0.009 | 0.01 | 21 |

Percentage of total oocytes with second chromosome AACAC probe mono-oriented.

Percentage of total oocytes with third chromosome Dodeca probe mono-oriented.

Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate the P-values compared to wild type.

HS = heat shock: These values were obtained from independent experiments with the heat-shock driver.

In addition, we tested several candidate genes for enhancement of UASP:Incenpmyc (Table S1). A mutation in non-claret disjunctional (ncd), which encodes a kinesin-14 motor protein, was notable because it enhanced as strongly as sub. The groups of genes that most consistently enhanced UASP:Incenpmyc were Cyclin B and its regulators. Also relevant to the current study is the finding that mutants in cytokinesis genes such as four wheel drive (fwd), which encodes phosphatidylinositol (PI) 4-kinase III β (Polevoy et al. 2009), and twinstar, which encodes cofilin (Gunsalus et al. 1995), enhanced UASP:Incenpmyc. Some mutants had surprisingly weak enhancement phenotypes, such as pav, Df(3L)Exel9000 that deletes pav and tum, which are strongly synthetic lethal. Other notable mutations that did not interact with UASP:Incenpmyc were in the central spindle component gene feo (encodes PRC1) and the checkpoint genes BubR1 and zw10. These results suggest that the enhancement of UASP:Incenpmyc depends on a specific defect. Indeed, there was evidence for allele-specific interactions, with mutations in genes such as fzy, which encodes a Cdc20 homolog; ord, which encodes a nonconserved cohesion protein, spc25, which encodes a kinetochore protein; and Incenp. Furthermore, a fwd mutant enhanced UASP:Incenpmyc while a deficiency, Df(3L)ED4177, had a weaker phenotype. These results suggest that specific types of alleles may cause enhancement of UASP:Incenpmyc. It is possible that all the genes that interact with UASP:Incenpmyc affect the localization or regulation of sub (see Discussion).

Polo kinase is required for karyosome maintenance and homologous chromosome bi-orientation at metaphase I

In the previous sections, we identified genes that genetically interact with sub and Incenp. To determine if any are required during meiosis I for chromosome segregation, we examined oocytes lacking some of these proteins for meiotic defects. Loss of these genes might be expected to have a phenotype similar to sub mutants, with defects in spindle bipolarity and homolog bi-orientation.

Mutants of polo are synthetic lethal with sub (Cesario et al. 2006). Since polo mutants are recessive lethal, we used polo RNAi (TRiP GL00014 and GL00512) to test the function of Polo in acentrosomal spindle assembly and chromosome segregation. Expression of both short hairpin RNA (shRNA) lines using ubiquitous P{tubP-GAL4}LL7 resulted in lethality, suggesting that the protein had been knocked down by the shRNA. Oocyte-specific shRNA expression was achieved using matalpha4-GAL4-VP16, and this resulted in sterility and knockdown of the messenger RNA as measured by qRT-PCR (Table S2 and Figure S7).

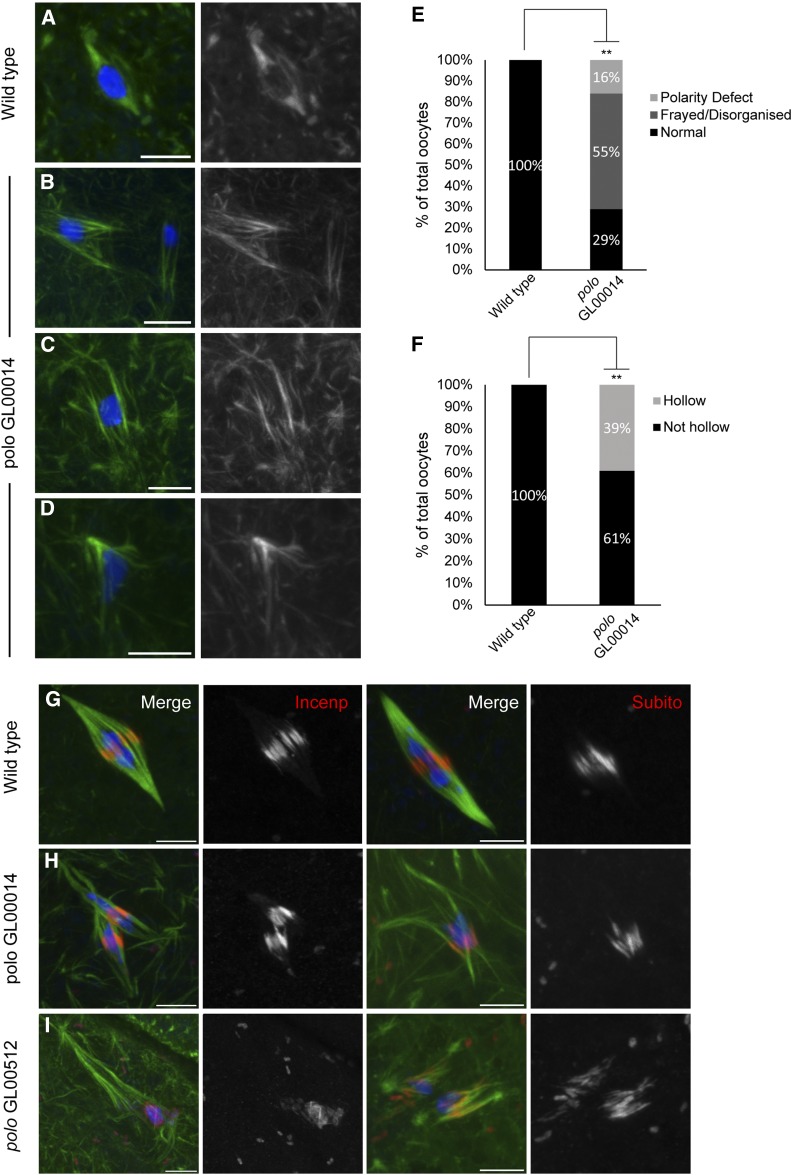

In wild-type oocytes, the chromosomes cluster together in a spherical mass referred to as the karyosome in the center of a spindle with well-defined poles and a central spindle containing Subito and the CPC (Figure 1, A and G). In polo GL00014 RNAi oocytes, there were defects in both chromosome and spindle organization. There were multiple karyosome masses (2–5) in most oocytes (Figure 1B) (69%; n = 31). In addition, there were defects in spindle microtubules that we have classified into three types. First, 55% of the oocytes had disorganized spindles with characteristics like frayed microtubules, untapered spindle poles, and displaced karyosomes (Figure 1B). Second, 39% of the spindles appeared “hollow,” composed primarily of central spindle microtubules and few or no kinetochore microtubules, those microtubules ending at the chromosomes (Figure 1C). Third, 16% of the oocytes had mono- or tripolar spindles (Figure 1D). Localization of the central spindle proteins INCENP and Subito was not affected (Figure 1H), suggesting that Polo is not required for central spindle assembly. Similar observations were made when the other shRNA, GL00512, was expressed (Figure 1I). The multiple karyosome phenotype (78%; n = 14) and spindle defects (Table S2) were observed at similar frequencies with the two shRNAs.

Figure 1.

Polo is required for karyosome and spindle organization at meiotic metaphase I. DNA is in blue, INCENP or Subito is in red, and tubulin is in green. (A) A wild-type bipolar spindle and (B–D) polo RNAi oocytes showing monopolar, frayed/disorganized, and hollow spindles, respectively. (E and F) Spindle defects in polo RNAi (n = 33) oocytes compared to wild type (n = 13). Percentage of oocytes with disorganized (E) or hollow (F) spindles are graphed separately. Asterisks denote significantly higher spindle defects (for E, P = 0.001; for F, P = 0.009). (G) Wild-type bipolar spindle showing either INCENP or Subito staining at meiotic central spindle. (H and I) polo GL00014 or GL00512 RNAi oocytes showing INCENP and Subito localization. Bars, 5 µm.

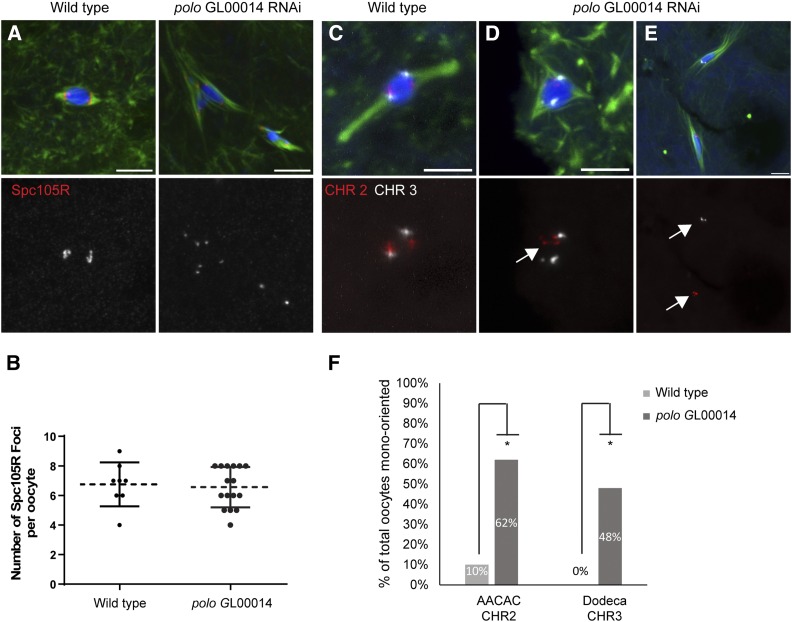

Polo accumulates at the kinetochores during meiotic metaphase of Drosophila oocytes (Jang et al. 2005). Therefore, we examined the centromeres and kinetochores directly in Polo knockout oocytes. At metaphase in wild-type oocytes, the centromeres are attached to microtubules and oriented toward the two poles while the central spindle forms between them with proteins like Subito and INCENP localized in a ring around the karyosome. The kinetochore protein SPC105R localized normally in GL00014 oocytes (Figure 2A), suggesting that Polo is not required for kinetochore assembly. With an average of 6.5 SPC105R foci per oocyte compared to 6.7 in wild type, these results also show that Polo is not required for cohesion at the centromeres at metaphase I (Figure 2B), in contrast to a recent report in mouse (Kim et al. 2015).

Figure 2.

Polo is required for bi-orientation but not kinetochore protein localization. (A) Wild-type and polo RNAi oocytes were stained with SPC105R antibody to examine localization of kinetochore components. SPC105R is in red, DNA in blue, and tubulin in green while the single channel shows SPC105R in white. (B) Graph showing the number of SPC105R foci in wild-type and polo GL00014 RNAi oocytes is not significantly different. (C–E) Probes to the AACAC repeat on the second chromosome (red) and the Dodeca satellite on the third chromosome (white) were used to assess bi-orientation. (C) In wild-type oocytes the second and third chromosomes bi-orient toward the two poles within a single karyosome. (D and E) polo RNAi oocytes showing mono-orientation (arrows) without and with a karyosome defect, respectively. Bars, 5 µm. (F) Summary of orientation defects in wild-type and polo GL00014 RNAi oocytes. Asterisk shows significantly higher mono-orientation compared to wild type. P-values are in Table 3.

In wild-type oocytes, each pair of homologous centromeres orients toward opposite poles (known as bi-orientation). To test if polo knockdown oocytes have bi-orientation defects, we performed FISH on polo RNAi oocytes with probes to the second (AACAC) and third (Dodeca) chromosome heterochromatin. Wild-type oocytes normally shows the second and third chromosome signals oriented toward opposite poles (Figure 2C and Table 3). In polo knockdown oocytes, the second and third chromosomes were frequently mono-oriented compared to wild type (Figure 2, D–F; Table 3). Due to the separated karyosome phenotype, in some cases these defects were observed in oocytes where the second and third chromosomes were in different masses with their own spindles. Importantly, in most cases where the karyosomes had separated, the homologous chromosome pairs were in the same mass, indicating that the cohesion holding the bivalents together had not been released. These results show that Polo is required for microtubule attachment, chromosome bi-orientation, and karyosome structure, but is not required for central spindle function.

Centralspindlin is required for meiotic spindle organization and homologous chromosome bi-orientation

We identified the Centralspindlin components pav and tum as synthetic lethal mutations with sub. The role of the Centralspindlin proteins in mitotic spindle midzone formation and stabilization leading to cytokinesis is well documented (Guse et al. 2005; D’Avino et al. 2006; Pavicic-Kaltenbrunner et al. 2007; Simon et al. 2008). Their contribution to acentrosomal spindle assembly, however, has not been characterized. To test the role of the Centralspindlin complex in oocyte meiotic spindle assembly, we expressed shRNA against both tum and pav (HMS01417 and HMJ02232, respectively) (Ni et al. 2011) with GAL4::VP16-nos.UTR, which expresses GAL4 with the germline-specific promoter from the nanos gene (Rorth 1998). Both lines failed to generate mature oocytes, probably due to cytokinesis defects in the mitotic germline divisions, which would also preclude using the FLP-FRT system to generate germline clones. To circumvent this problem, we expressed each shRNA with matalpha4-GAL-VP16, which expresses throughout most of the meiotic prophase but, importantly, after premeiotic S phase (Radford et al. 2012). However, these two shRNAs expressed with matalpha4-GAL-VP16 also produced very few mature oocytes, indicating a role for these proteins in oogenesis that prevented analysis of their meiotic function.

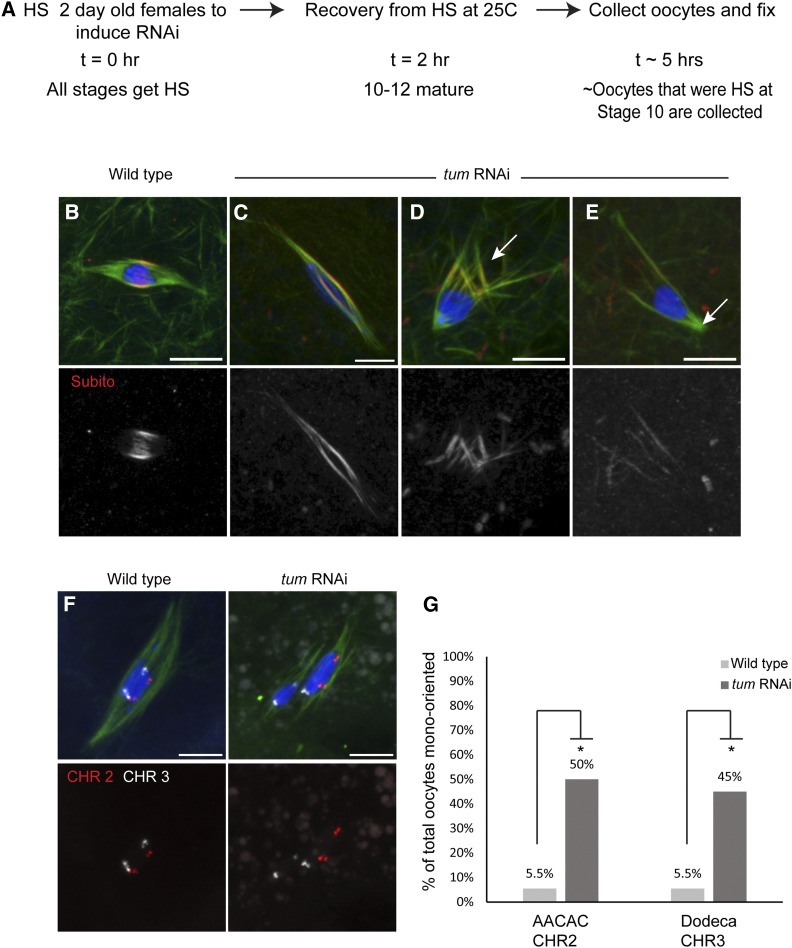

Because of the requirement for tum and pav in oogenesis, we developed an alternative method to knock down gene expression in oocytes. We chose to focus on tum with the goal of knocking down expression after its requirement in oogenesis, but prior to spindle assembly in mature oocytes. To achieve this, a heat-shock-inducible driver (P{GAL4-Hsp70.PB}89-2-1) was used to express tum shRNA (Figure 3A). The Drosophila oocyte undergoes 14 developmental stages to form a mature oocyte (Spradling 1993). Therefore, application of heat shock to a female will result in induction of RNAi in all stages present at the time. At 5 hr after induction of tum shRNA by heat shock, the adult females produced inviable embryos, suggesting that they had stage 14 oocytes depleted of TUM. This was confirmed using an antibody to TUM, which showed an absence of TUM protein on the spindle in a majority of the heat shock treated oocytes (Figure S8). At times greater than 5 hr after heat shock, in which stage 14 oocytes would have been at stage 10 or earlier at the time of heat shock, stage 14 oocytes were not produced. These results suggest that oocytes depleted of TUM at stage 10 or earlier fail to develop. With the 5-hr time point, however, we could investigate tum knockdown oocytes for defects in acentrosomal meiotic spindle assembly and chromosome segregation.

Figure 3.

TUM is required for proper localization of Subito to the central spindle and chromosome segregation during meiosis I. (A) Protocol used to induce RNAi expression late in oogenesis to bypass the early requirement of TUM in oocyte development. The heat-shock treatment caused some mild karyosome defects in the controls. However, these were occasionally observed in wild type, and the mutant defects were qualitatively different because they involved spindle organization defects not observed in the controls. (B–E) Wild-type and tum RNAi females were heat-shocked and examined for central spindle components. DNA is shown in blue, tubulin in green, and Subito in red in merged images. (B) Subito localizes to the central spindle region in wild type. (C–E) tum RNAi oocytes showing diffuse Subito staining all along the length of the spindle (C); frayed spindles are in D, and monopolar spindles are in E. (F) Wild-type and tum RNAi oocytes showing FISH probes AACAC (chromosome 2) in red and Dodeca (chromosome 3) in white. (G) Summary of mono-orientation frequency in tum RNAi oocytes compared to wild type. Asterisk indicates significantly different values. P-values are calculated by Fisher’s exact test (Table 3). Bars, 5 µm.

Similar to wild type, in heat-shocked wild-type oocytes or tum shRNA oocytes that were not heat-shocked, the chromosomes were clustered with their centromeres oriented toward the two poles while the central spindle proteins like Subito and Incenp localize in a ring around the karyosome (Figure 3B). In oocytes depleted of tum by heat-shock-induced RNAi, Subito was mislocalized over the entire spindle (65%; n = 20; P < <0.05) instead of its normal restriction to the central spindle in wild type (n = 14) (Figure 3C). Since TUM localization is abnormal in sub mutants (Jang et al. 2005), these results indicate that Subito and TUM are interdependent for their localization during meiosis. TUM-depleted spindles also had frayed microtubules or polarity defects (70%; n = 20; P < <0.05) as compared to wild type (14%; n = 14) (Figure 3, D and E). These oocytes frequently had grossly elongated or broken karyosomes (Figure 3F) (47%; n = 45; P < 0.0004) compared to wild-type oocytes (9%; n = 33).

Defects in spindle assembly can lead to mono-orientation, where homologous centromeres are oriented toward the same pole. To test if tum knockdown oocytes had bi-orientation defects, we performed FISH with probes to the heterochromatic regions of the second (AACAC repeat) and third (Dodeca satellite repeat) chromosomes. We found that in tum knockdown oocytes, 50% of oocytes had AACAC mono-oriented (n = 20; P < 0.05) and 45% of oocytes had Dodeca mono-oriented (n = 20; P < 0.05) as compared to 5.5% in wild type (n = 18) (Figure 3, F and G; Table 3). These results show that TUM is required for meiotic spindle assembly and chromosome bi-orientation.

Meiotic function of Centralspindlin may depend on Rho1 activation

Since the above results show that the Centralspindlin complex is required for meiotic chromosome segregation, we investigated the role of the proteins activated by this complex. Pebble, a Rho Guanine Exchange Factor (GEF, ECT2 homolog), associates with the Centralspindlin complex during mitotic anaphase, and together they regulate the GTPase Rho1 (RhoA) and its downstream effectors such as Citron kinase (encoded by sticky) (O’Keefe et al. 2001; Somers and Saint 2003; Yüce et al. 2005). There is also a second GEF, RhoGEF2, that may play a role in the germline (Padash Barmchi et al. 2005). Rho1 and Sticky (citron kinase homolog) are recruited by Centralspindlin to the spindle midzone during mitosis (D’Avino et al. 2004; Bassi et al. 2011, 2013). We failed to detect localization of Rho1 to the meiotic spindle using available antibodies. However, these negative results could be explained by localization to membranes, the actin cytoskeleton, or that some antibodies are very sensitive to fixation conditions in Drosophila oocytes (McKim et al. 2009). In contrast, we did detect Sticky on oocyte meiotic spindles (Figure S9).

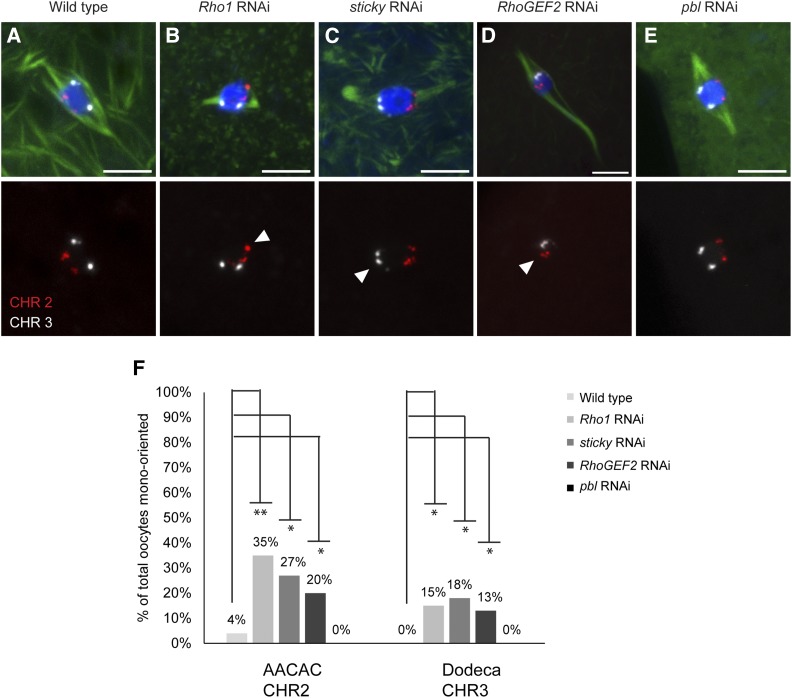

To examine their roles in spindle microtubule organization and homologous chromosome bi-orientation in oocytes, matalpha4-GAL-VP16}V37 was used to express shRNAs against Rho1, sticky, RhoGEF2, and pebble (HMS00375, GL00312, HMS01118, and GL01092, respectively). Expression of each shRNA with P{tubP-GAL4}LL7 caused lethality, suggesting that the proteins were indeed knocked down. Consistent with this, all four shRNAs caused significant knockdowns when evaluated using qRT-PCR of oocytes (Table S2).

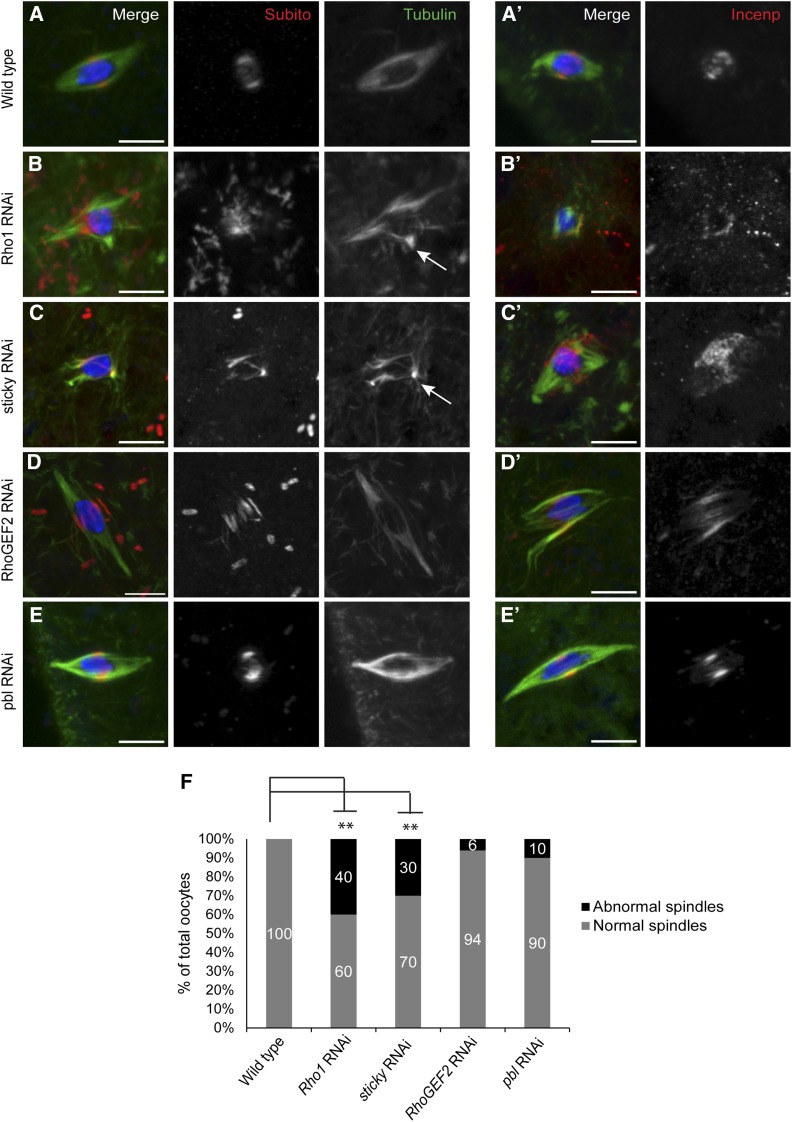

We used antibodies against Subito and INCENP as markers for the integrity of the meiotic central spindle. Wild-type metaphase spindles have a well-defined band of Subito and INCENP and a bipolar spindle (n = 30) (Figure 4, A and F). However, Rho1 RNAi oocytes showed a significantly higher level of abnormal spindle microtubule organization (40%, P < <0.05) accompanied by aberrant central spindle protein localization (Figure 4, B and F; Table S2). Sticky RNAi oocytes also showed significant microtubule disorganization (30%; P < <0.05) and Subito and INCENP mis-localization compared to wild-type control oocytes (Figure 4, C and F; Table S2). RhoGEF2 and pbl RNAi oocytes did not show any significant defects in either spindle formation or Subito or INCENP localization (Figure 4, D–F; Table S2). These results indicate that some mitotic cytokinesis proteins regulate acentrosomal spindle assembly and central spindle integrity in meiosis.

Figure 4.

Mitotic midzone proteins affect microtubule organization and central spindle protein localization in meiotic metaphase I. Oocytes were stained with DNA (blue), Tubulin (green), and Subito or INCENP (red). (A and A′) Wild-type oocytes localize Subito or INCENP to the central region of a bipolar metaphase spindle. (B and B′) Rho1 and (C and C′) sticky RNAi oocytes show disorganized microtubules (marked with arrows) and aberrant Subito or INCENP localization. (D and D′) RhoGEF2 and (E and E′) pbl RNAi oocytes resemble wild type in both microtubule organization and Subito localization. (F) Graph summarizing the spindle defects in wild-type and RNAi oocytes. Significantly different P-values are indicated by asterisks. Bars, 5 µm.

To test whether Rho1, sticky, RhoGEF2, and pebble RNAi oocytes show bi-orientation defects, we performed FISH on knockdown oocytes. Rho1, sticky, and RhoGEF2 showed significantly higher frequency of oocytes with mono-orientation defects compared to wild-type oocytes (Figure 5, A–D and F). In contrast, pbl RNAi oocytes showed no AACAC or Dodeca mono-orientation defects (n = 15) (Figure 5, E and F; Table 3). These results indicate that Rho1, Sticky, and RhoGEF2, but not Pebble, are required for the kinetochores to make correct attachments to microtubules that result in bi-orientation.

Figure 5.

Homologous chromosome bi-orientation is affected by Rho1, sticky, and RhoGEF2 but not by pbl RNAi. (A–E) (Top) Merged images with FISH probes AACAC (chromosome 2) in red and Dodeca (chromosome 3) in white. DNA is in blue and tubulin is in green. (A) The probes in wild type are bi-oriented toward the two poles. (B–D) Rho1, sticky, and RhoGEF2 RNAi oocytes show one or both probes mono-oriented. (E) pbl RNAi oocyte with no orientation defect. (Bottom) Only the probes are shown, with mono-orientation marked by arrowheads. Bars, 5 µm. (F) Summary of orientation defects. Significantly higher mono-orientation defects in mutants are indicated by asterisks, and P-values are indicated in Table 3.

Discussion

While the microtubules of the acentrosomal spindle may be nucleated from cytoplasmic MTOCs (Schuh and Ellenberg 2007) or from the chromatin itself (Heald et al. 1996), additional factors are required to organize them and segregate chromosomes. One such factor is the kinesin-6 motor protein Subito, which functions in cytokinesis during mitotic anaphase, but during acentrosomal meiosis it is required to organize a bipolar spindle (Giunta et al. 2002). Similarly, another prominent central spindle component is the CPC, which is also required for acentrosomal spindle assembly (Colombié et al. 2008; Radford et al. 2012). Based on these and other studies, we and others have suggested that, in the absence of centrosomes, the central spindle has a critical role in organizing the microtubules and chromosome alignment (Jang et al. 2005; Resnick et al. 2006; Dumont and Desai 2012; Radford et al. 2012). Thus, we have initiated the first comprehensive study of central spindle protein function in acentrosomal spindle assembly and chromosome segregation.

Cytological analysis of mitotic cells has shown that Subito is required to localize the CPC to the midzone during cytokinesis (Cesario et al. 2006), consistent with the studies of its human homolog, MKLP2 (Gruneberg et al. 2004). This function becomes only essential when the dosage of the CPC is reduced. We have used this observation to identify genes that interact genetically with sub, with the expectation that we might find other genes that function in meiotic spindle assembly like the CPC and Subito. We identified proteins associated with the mitotic central spindle or midzone, such as all CPC and Centralspindlin components. Furthermore, we confirmed that several mitotic central spindle genes have a role in meiotic acentrosomal spindle assembly. These are functions during metaphase I, rather than anaphase and cytokinesis as in mitotic cells. Finally, this study has identified at least 16 novel loci that interact with sub (synthetic lethal) and at least six novel loci on the third chromosome that interact meiotically with Incenp.

Polo may function only at the kinetochore during female metaphase I

We had previously found that polo mutations cause synthetic lethality and that there is a direct interaction between Polo and Subito (Cesario et al. 2006). Therefore, we determined if Polo has a meiotic central spindle function. Previous work in Drosophila has shown that Polo inhibition by Matrimony is important for maintaining prophase arrest (Xiang et al. 2007; Bonner et al. 2013), but its role in meiosis I has not been characterized. Polo has diverse roles in mitosis ranging from centrosome maturation, spindle assembly, kinetochore attachment, the SAC response, and cytokinesis (Carmena et al. 1998; Petronczki et al. 2008). Correlating with these diverse functions, Polo localizes to the centrosomes and centromeres at metaphase and the midzone at anaphase. Meiotic metaphase is different, however, because Polo retains its localization to the centromeres (Jang et al. 2005), unlike meiotic central spindle proteins like Subito and the CPC. In analyzing oocytes lacking Polo, we observed two prominent phenotypes. First, the chromosomes were disorganized, resulting in the failure to maintain a single karyosome. Second, these oocytes form aberrant spindles that appear to be composed mostly of central spindle. The spindles often appear “hollow,” which can reflect loss of kinetochore but not central spindle microtubules (Radford et al. 2015). These results are consistent with a role for Polo in stabilizing microtubule–kinetochore attachments (Elowe et al. 2007; Lénárt et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2012; Suijkerbuijk et al. 2012) but with no function in the central spindle. These results also show that, while the meiotic metaphase central spindle contains many proteins found in the anaphase midzone, it also has important differences. Indeed, it remains to be determine if Polo relocalizes to the midzone at anaphase I.

Mitotic spindle midzone proteins regulate acentrosomal spindle function

From our genetic screens, we identified mutations in all the components of two essential mitotic central spindle components: the CPC and Centralspindlin. Our analysis of TUM shows that Centralspindlin also plays an important role in organizing the acentrosomal spindle and localizing Subito. It is possible that, since Centralspindlin colocalizes with Subito in meiosis, it is involved in stabilizing the interpolar microtubules in the central spindle. TUM localization is in turn dependent on Subito, demonstrating the underlying interdependence of the meiotic central spindle proteins (Jang et al. 2005).

In its cytokinesis role, Centralspindlin signals to the actomyosin complex via the RhoA pathway. Pebble, the Drosophila homolog of GEF ECT2, is critical for cytokinesis (Yüce et al. 2005; Simon et al. 2008; Wolfe et al. 2009), interacts with RacGAP50C (O’Keefe et al. 2001; Somers and Saint 2003), and activates RhoA. Indeed, we found that Centralspindlin downstream effectors Rho1 (RhoA) and Sticky (Citron kinase) are required for accurate meiotic chromosome segregation. Loss of these proteins resulted in spindle assembly and centromere bi-orientation defects. This is the first report that the contractile ring proteins have been shown to be involved in meiotic chromosome segregation. Given these results, however, it was surprising that Pebble was not found to be critical for meiosis. Drosophila, however, has RhoGEF2 that is also a GEF and is required to regulate actin organization and contractility in the embryo (Padash Barmchi et al. 2005).

A hierarchy of central spindle assembly and function

None of the knockdowns we have studied have the same phenotype as a sub mutant with spindle bipolarity defects. Similarly, while we identified several interesting genes that interact with Incenp, most did not interact as strongly as sub mutants. We suggest that this interaction occurs because the epitope tag fused to the N terminus of the Incenp allele causes the dominant phenotype, and there is a direct physical interaction between Subito and the N terminus of INCENP, as recently described for MKLP2 (Kitagawa et al. 2014). That we observed consistent genetic interactions between Incenp and Cyclin B and some of its regulators, which are also known to regulate Subito/Mklp2 localization (Hummer and Mayer 2009; Kitagawa et al. 2014), is consistent with a specific direct interaction between Subito and Incenp. A surprisingly strong interaction was also observed between Incenp and ncd mutants, suggesting that the NCD motor has an important role in central spindle assembly. Indeed, we previously observed an allele-specific genetic interaction between ncd and sub (Giunta et al. 2002). These results are striking because ncd mutants do not have cytokinesis defects, suggesting that NCD may have a specific function in the central spindle of acentrosomal meiosis.

Based on the lack of mutants with phenotypes similar to sub, we suggest that the integrity of the meiotic central spindle and spindle bipolarity may depend only on the activity of Subito to bundle antiparallel microtubules. Our results also show, however, that contractile ring proteins are required in meiosis to maintain the organization of microtubules and promote homolog bi-orientation. One interpretation of these data is that the actin cytoskeleton is required for the organization or function of the meiotic central spindle microtubules. While the actin cytoskeleton is required to position the meiotic spindle in some systems (Brunet and Verlhac 2011; Fabritius et al. 2011; McNally 2013), it could also affect functioning of the spindle itself. Indeed, the formin mDIA3 has been shown to be involved in recruiting Aurora B for error correction (Mao 2011). RhoA has been shown to regulate microtubule stability, possibly through its downstream effectors mDia or Tau (Cook et al. 1998; Waterman-Storer et al. 2000; Palazzo et al. 2001). In the future, it will be important to directly perturb the actin cytoskeleton and examine chromosome alignment and segregation.

An alternative is that the contractile ring proteins directly regulate microtubule organization. Interestingly, RhoGEF2 has been found to associate with microtubule plus ends in a process that depends on EB1 (Rogers et al. 2004). Citron kinase (Sticky), rather than functioning simply as a downstream effector of RhoA, directly interacts with Pavarotti and another Kinesin, Nebbish (Klp38B), and is required for RhoA and Pavarotti localization and midzone formation (Bassi et al. 2011, 2013). In the future, it will be important to determine if the meiotic function of Citron kinase depends on interactions with actomyosin components or only with the microtubules.

Our results implicate proteins required during mitosis for midzone function and cytokinesis in meiotic chromosome segregation. In cytokinesis, a precise position of a division plane must be established (D’Avino et al. 2015). This activity may also be important for the acentrosomal spindle; a precise division plane may be established during metaphase I to sort each pair of homologous chromosomes. This process could result in the two kinetochores of each bivalent interacting with the microtubules from opposite poles. Activities such as those promoted by the Centralspindlin complex may fine-tune the central spindle structure to create a precise division plane. Further studies will be required, however, to determine if the meiotic spindle depends on interactions with the actin cytoskeleton for chromosome segregation or if these proteins exert their effects only through central spindle microtubules at meiosis I.

Acknowledgments

We thank Li Nguyen for technical assistance; Karen Schindler, Ruth Steward, and members of the McKim lab for helpful comments on the manuscript; Christian Lehner, David Glover, and Robert Saint for providing antibodies; and the Transgenic RNAi Project at Harvard Medical School [National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant R01-GM084947] for providing transgenic RNAi fly stocks. Fly stocks obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH grant P40OD018537) were also used in this study. A.D. was funded by a Busch Predoctoral Fellowship, and S.J.S., B.F., and R.A.B. were funded by an Aresty Foundation Summer Research Fellowship. This work was supported by NIH grant GM101955 (to K.S.M.).

Footnotes

Communicating editor: S. E. Bickel

Supporting information is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.115.181081/-/DC1.

Literature Cited

- Adams R. R., Tavares A. A., Salzberg A., Bellen H. J., Glover D. M., 1998. pavarotti encodes a kinesin-like protein required to organize the central spindle and contractile ring for cytokinesis. Genes Dev. 12: 1483–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf S. I., Ip Y. T., 2001. The Snail protein family regulates neuroblast expression of inscuteable and string, genes involved in asymmetry and cell division in Drosophila. Development 128: 4757–4767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf S. I., Hu X., Roote J., Ip Y. T., 1999. The mesoderm determinant snail collaborates with related zinc-finger proteins to control Drosophila neurogenesis. EMBO J. 18: 6426–6438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi Z. I., Verbrugghe K. J., Capalbo L., Gregory S., Montembault E., et al. , 2011. Sticky/Citron kinase maintains proper RhoA localization at the cleavage site during cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 195: 595–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi Z. I., Audusseau M., Riparbelli M. G., Callaini G., D’Avino P. P., 2013. Citron kinase controls a molecular network required for midbody formation in cytokinesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: 9782–9787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner A. M., Hughes S. E., Chisholm J. A., Smith S. K., Slaughter B. D., et al. , 2013. Binding of Drosophila Polo kinase to its regulator Matrimony is noncanonical and involves two separate functional domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: E1222–E1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet S., Verlhac M. H., 2011. Positioning to get out of meiosis: the asymmetry of division. Hum. Reprod. Update 17: 68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaini G., Riparbelli M. G., 1996. Fertilization in Drosophila melanogaster: centrosome inheritance and organization of the first mitotic spindle. Dev. Biol. 176: 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmena M., Riparbelli M. G., Minestrini G., Tavares A. M., Adams R., et al. , 1998. Drosophila polo kinase is required for cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 143: 659–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesario J. M., Jang J. K., Redding B., Shah N., Rahman T., et al. , 2006. Kinesin 6 family member Subito participates in mitotic spindle assembly and interacts with mitotic regulators. J. Cell Sci. 119: 4770–4780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou T. B., Perrimon N., 1996. The autosomal FLP-DFS technique for generating germline mosaics in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 144: 1673–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombié N., Cullen C. F., Brittle A. L., Jang J. K., Earnshaw W. C., et al. , 2008. Dual roles of Incenp crucial to the assembly of the acentrosomal metaphase spindle in female meiosis. Development 135: 3239–3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook T. A., Nagasaki T., Gundersen G. G., 1998. Rho guanosine triphosphatase mediates the selective stabilization of microtubules induced by lysophosphatidic acid. J. Cell Biol. 141: 175–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Avino P. P., Savoian M. S., Glover D. M., 2004. Mutations in sticky lead to defective organization of the contractile ring during cytokinesis and are enhanced by Rho and suppressed by Rac. J. Cell Biol. 166: 61–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Avino P. P., Savoian M. S., Capalbo L., Glover D. M., 2006. RacGAP50C is sufficient to signal cleavage furrow formation during cytokinesis. J. Cell Sci. 119: 4402–4408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Avino P. P., Giansanti M. G., Petronczki M., 2015. Cytokinesis in animal cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7: a015834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doubilet S., McKim K. S., 2007. Spindle assembly in the oocytes of mouse and Drosophila: similar solutions to a problem. Chromosome Res. 15: 681–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont J., Desai A., 2012. Acentrosomal spindle assembly and chromosome segregation during oocyte meiosis. Trends Cell Biol. 22: 241–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elowe S., Hümmer S., Uldschmid A., Li X., Nigg E. A., 2007. Tension-sensitive Plk1 phosphorylation on BubR1 regulates the stability of kinetochore microtubule interactions. Genes Dev. 21: 2205–2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabritius A. S., Ellefson M. L., McNally F. J., 2011. Nuclear and spindle positioning during oocyte meiosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23: 78–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fededa J. P., Gerlich D. W., 2012. Molecular control of animal cell cytokinesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 14: 440–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giunta K. L., Jang J. K., Manheim E. A., Subramanian G., McKim K. S., 2002. subito encodes a kinesin-like protein required for meiotic spindle pole formation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 160: 1489–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloor G. B., Preston C. R., Johnson-Schlitz D. M., Nassif N. A., Phillis R. W., et al. , 1993. Type I repressors of P element mobility. Genetics 135: 81–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzer M., 2005. The molecular requirements for cytokinesis. Science 307: 1735–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein A. Y., Jan Y. N., Luo L., 2005. Function and regulation of Tumbleweed (RacGAP50C) in neuroblast proliferation and neuronal morphogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 3834–3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruneberg U., Neef R., Honda R., Nigg E. A., Barr F. A., 2004. Relocation of Aurora B from centromeres to the central spindle at the metaphase to anaphase transition requires MKlp2. J. Cell Biol. 166: 167–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunsalus K. C., Bonaccorsi S., Williams E., Verni F., Gatti M., et al. , 1995. Mutations in twinstar, a Drosophila gene encoding a cofilin/ADF homologue, result in defects in centrosome migration and cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 131: 1243–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guse A., Mishima M., Glotzer M., 2005. Phosphorylation of ZEN-4/MKLP1 by aurora B regulates completion of cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 15: 778–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heald R., Tournebize R., Blank T., Sandaltzopoulos R., Becker P., et al. , 1996. Self-organization of microtubules into bipolar spindles around artificial chromosomes in Xenopus egg extracts. Nature 382: 420–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert M., Kalleas D., Cooney D., Lamb M., Lister L., 2015. Meiosis and maternal aging: insights from aneuploid oocytes and trisomy births. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7: a017970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer S., Mayer T. U., 2009. Cdk1 negatively regulates midzone localization of the mitotic kinesin Mklp2 and the chromosomal passenger complex. Curr. Biol. 19: 607–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J. K., Rahman T., McKim K. S., 2005. The kinesinlike protein Subito contributes to central spindle assembly and organization of the meiotic spindle in Drosophila oocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell 16: 4684–4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Ishiguro K., Nambu A., Akiyoshi B., Yokobayashi S., et al. , 2015. Meikin is a conserved regulator of meiosis-I-specific kinetochore function. Nature 517: 466–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M., Fung S. Y., Hameed U. F., Goto H., Inagaki M., et al. , 2014. Cdk1 coordinates timely activation of MKlp2 kinesin with relocation of the chromosome passenger complex for cytokinesis. Cell Reports 7: 166–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai S. L., Miller M. R., Robinson K. J., Doe C. Q., 2012. The Snail family member Worniu is continuously required in neuroblasts to prevent Elav-induced premature differentiation. Dev. Cell 23: 849–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Davydenko O., Lampson M. A., 2012. Polo-like kinase-1 regulates kinetochore-microtubule dynamics and spindle checkpoint silencing. J. Cell Biol. 198: 491–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lénárt P., Petronczki M., Steegmaier M., Di Fiore B., Lipp J. J., et al. , 2007. The small-molecule inhibitor BI 2536 reveals novel insights into mitotic roles of polo-like kinase 1. Curr. Biol. 17: 304–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magie C. R., Pinto-Santini D., Parkhurst S. M., 2002. Rho1 interacts with p120ctn and alpha-catenin, and regulates cadherin-based adherens junction components in Drosophila. Development 129: 3771–3782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y., 2011. FORMIN a link between kinetochores and microtubule ends. Trends Cell Biol. 21: 625–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthies H. J., McDonald H. B., Goldstein L. S., Theurkauf W. E., 1996. Anastral meiotic spindle morphogenesis: role of the non-claret disjunctional kinesin-like protein. J. Cell Biol. 134: 455–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKim K. S., Joyce E. F., Jang J. K., 2009. Cytological analysis of meiosis in fixed Drosophila ovaries. Methods Mol. Biol. 558: 197–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally F. J., 2013. Mechanisms of spindle positioning. J. Cell Biol. 200: 131–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minestrini G., Harley A. S., Glover D. M., 2003. Localization of Pavarotti-KLP in living Drosophila embryos suggests roles in reorganizing the cortical cytoskeleton during the mitotic cycle. Mol. Biol. Cell 14: 4028–4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A., Salmon E. D., 2007. The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8: 379–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef R., Preisinger C., Sutcliffe J., Kopajtich R., Nigg E. A., et al. , 2003. Phosphorylation of mitotic kinesin-like protein 2 by polo-like kinase 1 is required for cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 162: 863–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni J. Q., Zhou R., Czech B., Liu L. P., Holderbaum L., et al. , 2011. A genome-scale shRNA resource for transgenic RNAi in Drosophila. Nat. Methods 8: 405–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe L., Somers W. G., Harley A., Saint R., 2001. The pebble GTP exchange factor and the control of cytokinesis. Cell Struct. Funct. 26: 619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padash Barmchi M., Rogers S., Häcker U., 2005. DRhoGEF2 regulates actin organization and contractility in the Drosophila blastoderm embryo. J. Cell Biol. 168: 575–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo A. F., Cook T. A., Alberts A. S., Gundersen G. G., 2001. mDia mediates Rho-regulated formation and orientation of stable microtubules. Nat. Cell Biol. 3: 723–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavicic-Kaltenbrunner V., Mishima M., Glotzer M., 2007. Cooperative assembly of CYK-4/MgcRacGAP and ZEN-4/MKLP1 to form the centralspindlin complex. Mol. Biol. Cell 18: 4992–5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronczki M., Lénárt P., Peters J. M., 2008. Polo on the rise: from mitotic entry to cytokinesis with Plk1. Dev. Cell 14: 646–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polevoy G., Wei H. C., Wong R., Szentpetery Z., Kim Y. J., et al. , 2009. Dual roles for the Drosophila PI 4-kinase four wheel drive in localizing Rab11 during cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 187: 847–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford S. J., Jang J. K., McKim K. S., 2012. The chromosomal passenger complex is required for meiotic acentrosomal spindle assembly and chromosome bi-orientation. Genetics 192: 417–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford S. J., Hoang T. L., Głuszek A. A., Ohkura H., McKim K. S., 2015. Lateral and end-on kinetochore attachments are coordinated to achieve bi-orientation in Drosophila oocytes. PLoS Genet. 11: e1005605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick T. D., Satinover D. L., MacIsaac F., Stukenberg P. T., Earnshaw W. C., et al. , 2006. INCENP and Aurora B promote meiotic sister chromatid cohesion through localization of the Shugoshin MEI-S332 in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 11: 57–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riparbelli M. G., Callaini G., 2005. The meiotic spindle of the Drosophila oocyte: the role of centrosomin and the central aster. J. Cell Sci. 118: 2827–2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S. L., Wiedemann U., Häcker U., Turck C., Vale R. D., 2004. Drosophila RhoGEF2 associates with microtubule plus ends in an EB1-dependent manner. Curr. Biol. 14: 1827–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorth P., 1998. Gal4 in the Drosophila female germline. Mech. Dev. 78: 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchaud S., Carmena M., Earnshaw W. C., 2007. Chromosomal passengers: conducting cell division. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8: 798–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schittenhelm R. B., Heeger S., Althoff F., Walter A., Heidmann S., et al. , 2007. Spatial organization of a ubiquitous eukaryotic kinetochore protein network in Drosophila chromosomes. Chromosoma 116: 385–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schittenhelm R. B., Chaleckis R., Lehner C. F., 2009. Intrakinetochore localization and essential functional domains of Drosophila Spc105. EMBO J. 28: 2374–2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuh M., Ellenberg J., 2007. Self-organization of MTOCs replaces centrosome function during acentrosomal spindle assembly in live mouse oocytes. Cell 130: 484–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G. C., Schonteich E., Wu C. C., Piekny A., Ekiert D., et al. , 2008. Sequential Cyk-4 binding to ECT2 and FIP3 regulates cleavage furrow ingression and abscission during cytokinesis. EMBO J. 27: 1791–1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers W. G., Saint R., 2003. A RhoGEF and Rho family GTPase-activating protein complex links the contractile ring to cortical microtubules at the onset of cytokinesis. Dev. Cell 4: 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling A. C., 1993. Developmental genetics of oogenesis, pp. 1–70 in The Development of Drosophila melanogaster, edited by Bate M., Arias A. M. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Suijkerbuijk S. J., Vleugel M., Teixeira A., Kops G. J., 2012. Integration of kinase and phosphatase activities by BUBR1 ensures formation of stable kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Dev. Cell 23: 745–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theurkauf W. E., Hawley R. S., 1992. Meiotic spindle assembly in Drosophila females: behavior of nonexchange chromosomes and the effects of mutations in the nod kinesin-like protein. J. Cell Biol. 116: 1167–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng B. S., Tan L., Kapoor T. M., Funabiki H., 2010. Dual detection of chromosomes and microtubules by the chromosomal passenger complex drives spindle assembly. Dev. Cell 18: 903–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman-Storer C., Duey D. Y., Weber K. L., Keech J., Cheney R. E., et al. , 2000. Microtubules remodel actomyosin networks in Xenopus egg extracts via two mechanisms of F-actin transport. J. Cell Biol. 150: 361–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe B. A., Takaki T., Petronczki M., Glotzer M., 2009. Polo-like kinase 1 directs assembly of the HsCyk-4 RhoGAP/Ect2 RhoGEF complex to initiate cleavage furrow formation. PLoS Biol. 7: e1000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y., Takeo S., Florens L., Hughes S. E., Huo L. J., et al. , 2007. The inhibition of polo kinase by matrimony maintains G2 arrest in the meiotic cell cycle. PLoS Biol. 5: e323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yüce O., Piekny A., Glotzer M., 2005. An ECT2-centralspindlin complex regulates the localization and function of RhoA. J. Cell Biol. 170: 571–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavortink M., Contreras N., Addy T., Bejsovec A., Saint R., 2005. Tum/RacGAP50C provides a critical link between anaphase microtubules and the assembly of the contractile ring in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Sci. 118: 5381–5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]