Use of pathologic complete response (pCR) as a trial-level surrogate for survival in early-stage breast cancer has been controversial. Re-analyses of data from two prior meta-analyses failed to demonstrate that pCR is a reliable trial-level surrogate for event-free or overall survival, or that it can be used to reliably screen out nonpromising agents from further drug development.

Keywords: breast cancer, pathologic complete response, surrogate end point, trial-level surrogate end point, randomized clinical trial, screening trials

Abstract

Background

A trial-level surrogate end point for a randomized clinical trial may allow assessment of the relative benefits of the treatment to be performed at an earlier time point and potentially with a smaller sample size. However, determining whether an end point is a reliable trial-level surrogate based on results of previous trials is not straightforward. The question of trial-level surrogacy is easily confused with the question of individual-level surrogacy, and this confusion can lead to controversy. A recent example concerns the evaluation of pathologic complete response (pCR) as a surrogate for event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) in early-stage breast cancer.

Materials and methods

The differences between individual-level surrogacy (i.e. for patients receiving a specific treatment, the surrogate end point predicts the definitive end point) and trial-level surrogacy (the results of the trial for the surrogate end point predict the results of the trial for the definitive end point) are discussed. Trial-level data used in two previous meta-analyses evaluating pCR as a trial-level surrogate for EFS and OS were re-analyzed using methods that appropriately account for the variability in pCR rates as well as the variability in the hazard ratios for EFS and OS.

Results

There is no evidence that pCR is a trial-level surrogate for EFS or OS, nor is there evidence that pCR could be used reliably to screen out nonpromising agents from further drug development.

Conclusions

At present, neoadjuvant RCTs should continue to follow patients to observe EFS and OS to assess clinical benefit, and they should be designed with sufficient sample size to reliably assess EFS. However, one cannot rule out the possibility that future meta-analyses involving more trials and in which the patient population or class of treatments is restricted could suggest the validity of pCR as a trial-level surrogate for EFS or OS in some focused settings.

introduction

Performing a randomized clinical trial (RCT) to assess the clinical benefit of a new adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment of early-stage breast cancer requires a large trial and a long time to observe sufficient numbers of overall survival (OS) or event-free survival (EFS) events to yield reliable conclusions. If one could predict OS and EFS results from surrogate outcome results observed earlier, one could develop new treatments more quickly and possibly make them available to patients sooner. In 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) distributed the draft guidance for industry, ‘Pathological complete response in neoadjuvant treatment of high-risk early-stage breast cancer: use as an endpoint to support accelerated approval’ [1]; the guidance was finalized in 2014 [2]. The guidance suggests that a new neoadjuvant treatment that shows sufficient improvement in pCR rates over a standard treatment in a RCT could support FDA accelerated approval. At the time of the release of the draft guidance, FDA investigators were performing a meta-analysis of 12 neoadjuvant trials, from which they eventually concluded ‘Patients who attain pathological complete response … have improved survival’ but ‘Our pooled analysis could not validate pathological complete response as a surrogate endpoint for improved EFS and OS.’ [3]. A second meta-analysis of 29 trials conducted by an independent group of investigators reached a similar conclusion: ‘This meta-regression analysis of 29 heterogeneous neoadjuvant trials does not support the use of pCR as a surrogate endpoint for DFS (disease-free survival) and OS in patients with breast cancer.’ [4]. A final piece of evidence obtained from a recently completed phase III trial reported at the 2014 ASCO Annual Meeting casts further doubt on the value of pCR as a surrogate end point; the ALTTO trial, which compared lapatinib plus trastuzumab to trastuzumab as adjuvant treatment, was reported as not being statistically significant [hazard ratio (HR) for DFS = 0.84, 97.5% confidence interval (CI) 0.70–1.02] [5]. This is despite the fact that the NeoALTTO trial, which compared the same treatments in the neoadjuvant setting, had shown a large increase in pCR rates with the addition of lapatinib (51.3% versus 29.5%) [6]. (Similar EFS results to ALTTO were seen in further follow-up of the NeoALTTO trial [7], but the numbers of events in NeoALTTO were small because that trial was not designed with sufficient sample size to reliably assess survival.) Even though the clinical setting was different (adjuvant instead of neoadjuvant), the impressive effect on pCR rates in NeoALTTO had led to the hope that the ALTTO trial would be impressively positive for DFS [8]. The modest observed HR for DFS in ALTTO and its failure to reach statistical significance did not meet these high expectations.

Despite the ostensibly negative conclusion about the reliability of pCR as a surrogate in the meta-analyses and the ALTTO-NeoALTTO trials, some have argued that pCR remains a useful end point and ‘should continue to be used as an opportunity to accelerate evaluation of promising agents’ [9]. This topic has been the center of a lively debate [8–12]. We believe that, part of the argument is due to a misunderstanding of terms, in particular, what is required of pCR to be useful as a drug development tool. We address this issue in this commentary by first examining the notions of individual-level versus trial-level surrogacy, and where pCR fits in this conceptual framework. We follow this by a detailed re-examination of the evidence in the previously published Cortazar and Berruti meta-analyses, with a focus on evaluation of the potential of pCR as a surrogate and/or as a screening end point. We end with a discussion of our conclusions.

individual-level versus trial-level surrogate end points

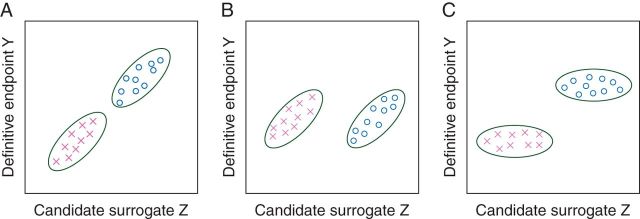

An intermediate end point that can be observed after randomization but before the definitive end point is an individual-level surrogate if, for patients receiving a given treatment, it reliably predicts patients who will have relatively good outcomes from those who will have relatively poor outcomes as reflected by the definitive end point. An intermediate end point is a trial-level surrogate if the results of a between-arm comparison of the intermediate end point reliably predict the eventual results of a between-arm comparison of the definitive clinical end point. Individual-level surrogacy and trial-level surrogacy are distinct concepts; an end point can be one and not the other [13, 14] (Figure 1). For example, consider a candidate surrogate marker (e.g. a tissue marker of tumor proliferation) that is strongly correlated with the definitive outcome when patients are given treatment X, and strongly correlated with the definitive outcome when patients are given treatment O. Although this marker would be a good individual-level surrogate, it is possible that it is a poor trial-level surrogate if, on average, the treatments X and O are equally effective in terms of the definitive outcome but treatment O is better than treatment X in terms of the candidate surrogate outcome (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Hypothetical data from a RCT of two treatments (represented by crosses and open circles) with a candidate surrogate end point Z and a definitive end point Y. (A) Z is both a good individual-level and trial-level surrogate for Y. (B) Z is a good individual-level surrogate for Y (within each treatment, Z and Y are correlated) but a poor trial-level surrogate for Y (there is no average effect of the treatment on Y but a large average effect on Z). (C) Z is a good trial-level surrogate but a poor individual-level surrogate for Y within each treatment arm.

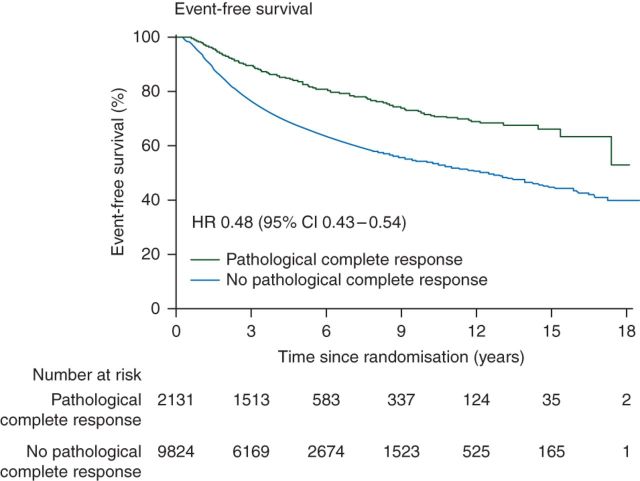

Although it is logically possible, how likely is it that pCR is a poor trial-level surrogate given that it is a reasonable individual-level surrogate (Figure 2)? It is helpful to consider hypothetical data again as one can then specify the relationships between the outcomes: Consider patients treated with a standard neoadjuvant treatment whose 5-year EFS is 85% or 65% for the 12% or 88% of the patients who had a pCR or not, respectively (standard treatment in Table 1). The overall EFS for these patients would be 67.4%. Now consider a new treatment that increases the pCR rate to 24% by achieving pCRs in an additional 12% of the patients who previously did not have a pCR (treatment 1 in Table 1). Suppose pCR status completely captures the effect of this new treatment, so that 5-year EFS for all patients who have a pCR is the same regardless of the treatment (new or standard) received, and the 5-year EFS for all patients who do not have a pCR is the same regardless of the treatment received. (Prentice [15] used this type of criterion to operationally define what is meant by a surrogate variable; we shall denote such a variable as a ‘Prentice surrogate’.) If pCR were a Prentice surrogate, we could calculate that the 5-year EFS would be 69.8% on treatment 1, better than the standard treatment, but not by a clinically meaningful amount. However, pCR may not be a Prentice surrogate and the new treatment could also improve the EFS of the patients who did not have a pCR (and possibly also the EFS of patients who had a pCR). As a simple example (treatment 2), suppose that the new treatment, in addition to increasing the pCR rate to 24%, improves the 5-year EFS of the remaining 76% of the patients from 65% to 75%, with the 5-year EFS for patients who experience a pCR remaining at 85%. With this scenario, the new treatment would be better than the standard treatment by a clinically meaningful amount with 5-year EFS being 77.4%. For a third example (treatment 3), we assume that the new treatment increases the pCR rate to 24%, but the additional 12% of the patients achieving a pCR do not have 5-year EFS of 85%, but only 75%. Then, the new and control treatments will have very similar 5-year EFS (68.6% versus 67.4%).

Figure 2.

Association between pCR and event-free survival in the CTNeoBC-pooled analysis (this figure is part of Figure 2 of Cortazar et al. [3]). Permission obtained.

Table 1.

Hypothetical 5-year event-free survival (EFS) rates (stratified by pCR status) for standard treatment and four new treatments that increase the pCR rates from 12% to 24%

| pCR outcome (%) | 5-year EFS (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Standard treatment | ||

| pCR | 12 | 85 |

| No pCR | 88 | 65 |

| Overall | – | 67.4 |

| New treatment 1 | ||

| pCR | 24 | 85 |

| No pCR | 76 | 65 |

| Overall | 69.8 | |

| New treatment 2 | ||

| pCR | 24 | 85 |

| No pCR | 76 | 75 |

| Overall | 77.4 | |

| New treatment 3 | ||

| pCR | 24 | (85 + 75)/2 = 80 |

| No pCR | 76 | 65 |

| Overall | 68.6 | |

| New treatment 4 | ||

| pCR | 24 | 90 |

| No pCR | 76 | 50 |

| Overall | 59.6 | |

Bolded numbers represent 5-year EFS for the group as a whole, regardless of pCR status.

(i) For treatment 1, pCR is a Prentice surrogate.

(ii) For treatment 2, treatment additionally increases 5-year EFS in the no-pCR group from 65% to 75%.

(iii) For treatment 3, the additional 12% of patients with a pCR have a 75% 5-year DFS, yielding 80% overall 5-year DFS for patients with a pCR.

(iv) For treatment 4, the 5-year DFS rates are 90% and 50% for the pCR and no-pCR groups.

As a final hypothetical example (treatment 4 in Table 1), suppose that the new treatment increases the pCR rate to 24% and the 5-year survival of those patients who experience a pCR is increased to 90%, whereas the 5-year EFS for the 76% who do not experience a pCR is decreased to 50%; the net result would be an overall 5-year EFS of 59.6%. Such a scenario could occur if the mechanisms of action of the standard and new therapies are such that the new treatment offers better EFS for patients who achieve a pCR and worse EFS for those who do not. It is even possible that if the new treatment has additional toxicities over the standard treatment that may limit some concurrent or subsequent therapies, then the new treatment could have worse EFS than the standard treatment even though it improves the pCR rate.

We conclude from these hypothetical examples that just knowing that pCR is a good individual-level surrogate does not allow one to predict at the trial level whether an improvement in pCR rate will translate into a survival difference; a large improvement in pCR rate could result in a small or large survival difference, or even worse EFS. Therefore, to assess whether pCR is an appropriate end point in clinical trials to support drug approval, one needs to evaluate trial-level pCR rates and survival data across trials, as will be discussed in the next section.

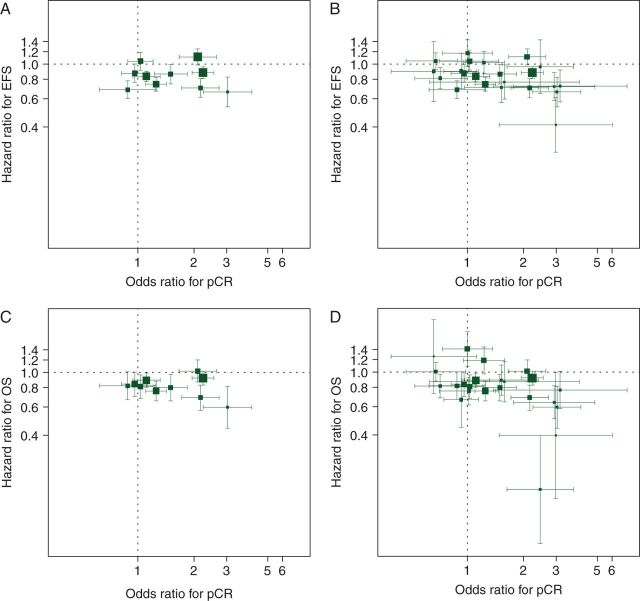

pCR as a trial-level surrogate

We perform a re-analysis of the trial results presented in Cortazar et al. [3] and Berruti et al. [4] to assess pCR as a trial-level surrogate for EFS and OS; the trials in the Cortazar analysis are included among the trials in the Berruti analysis. Figure 3A and B displays the associations between trial-level pCR effect [expressed as an odds ratio (OR)] and EFS effect (expressed as a HR), with Figure 3C and D presenting pCR and OS trial-level results; the trial-level data used in these analyses are in supplementary Appendix, available at Annals of Oncology online. A pattern of squares clustering around a line with a moderately large negative slope in these figures would provide evidence for trial-level surrogacy. This would indicate that for trials in which the OR for pCR is large comparing the treatment arms, the HRs for EFS and OS are small. (HRs are reported as the hazard of the experimental treatment divided by the hazard of the control treatment, so that smaller values represent more effective experimental treatments.) The plots in Figure 3 do not provide evidence to support such a relationship.

Figure 3.

Association of trial-level pCR effects (odds ratios) and EFS or OS effects (hazard ratios). (A) EFS, Cortazar trials; (B) EFS, Berruti trials; (C) OS, Cortazar trials; (D) OS, Berruti trials. Areas of squares are proportional to trial sample sizes and horizontal and vertical line segments represent 95% confidence intervals for the trial-level odds ratios and hazard ratios, respectively. The trials in the Cortazar analysis are included among the trials in the Berruti analysis.

Conclusions from Figure 3 should not be drawn too hastily, as one needs to consider whether the lack of association could be due to insufficient amount of data—too few trials or individual trials that are too small. To help answer this question, one can use one of the formal models of surrogacy [13]. We use a nonlinear mixed model with measurement error that has been used previously [14]. To examine the association between the trial-level pCR OR and the EFS hazard ratio (HREFS), we employ the model

| (1) |

| (1) |

where for Equation (1), for trial i, ORi is the observed OR comparing pCR for the two treatment arms, µ + mi is the true log OR for pCR (µ is a fixed effect representing the average log OR across trials, and mi is a random effect with mean 0 and variance representing an effect for trial i), and ϵi is a random error with standard deviation equal to the within-trial standard error of the estimate of the log OR. In Equation (2), is the observed HR comparing the two treatments arms in trial i. This equation specifies a linear relationship (with intercept α and slope β) between the true log HR for EFS () and the true log OR for pCR. Here, gi is a random effect with mean 0 and standard deviation that represents how much the true trial i log HR deviates from the regression line, and δi is a random error with standard deviation equal to the within-trial standard error of the estimate of the log HR for EFS for trial i. If pCR is a good trial-level surrogate for EFS, then β should be negative and large in absolute value (so that large ORs for pCR correspond to small HRs for EFS) and should be small. These parameters jointly govern the ability of the pCR OR to predict the EFS HR.

Table 2 presents the parameters estimated for the statistical model for EFS and pCR for the Cortazar and Berruti trials (see supplementary Appendix, available at Annals of Oncology online). For the Cortazar trials, the estimated slope (β) is close to zero (and positive), reinforcing the lack of association seen in Figure 3A. For the Berruti trials, the estimated slope is negative but less than one-standard error away from zero (i.e. far from being statistically significant). Table 3 uses the parameter estimates in Table 2 to predict the true EFS HR for a new trial based on its observed pCR results and sample size (see supplementary Appendix, available at Annals of Oncology online). For example, suppose a new trial with a sample size of 100 is carried out with observed pCR rates of 20% and 10% in the experimental and control treatment arms, respectively. Then using the model parameter estimates from the Cortazar data, we would predict that the true EFS HR for these treatments is 0.85, with a 95% prediction interval of (0.67, 1.08). Using the Cortazar data, the predicted HRs are essentially independent of the pCR results, with all ∼0.85 (roughly the average observed HR across the 10 trials analyzed). The fact that the average HR is observed to be less than one may suggest influence of some selection factors in deciding which trials to conduct or which trials to include in the meta-analysis, but this provides no evidence for value of pCR as a surrogate because HRs do not become smaller with increasingly positive pCR results. One may also be interested in predicting the HR that would be observed for a new trial (rather than the true HR for the treatments being tested in the new trial). The prediction based on the pCR rates is the same, but the prediction intervals are much wider and with the interval widths varying by the sample size of the trial (see supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 2.

Parameters (±standard errors) for nonlinear mixed-effects model for the association of log HR of EFS and log OR for pCR based on trials analyzed by Cortazar and Berruti

| Parameter | Estimate ± standard error |

|

|---|---|---|

| Cortazar trials (10 trials) | Berruti trials (23 trials) | |

| β | 0.0454 ± 0.1834 | −0.1230 ± 0.1505 |

| α | −0.1829 ± 0.0805 | −0.1072 ± 0.0581 |

| 0.00743 ± 0.01524 | 0.00759 ± 0.00932 | |

| µ | 0.3873 ± 0.1198 | 0.3057 ± 0.0942 |

| 0.1119 ± 0.0730 | 0.1120 ± 0.0610 | |

Table 3.

Predicted true EFS hazard ratio (95% prediction interval) for a new trial with specified sample size and observed pCR rates estimated using parameters in Table 2 (Cortazar trial data, top panel; Berruti trial data, bottom panel)

| New trial pCR results (experimental versus control) | Sample size of new trial |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 300 | 1000 | |

| Based on Cortazar trial data | |||

| 10% versus 10% | 0.84 (0.67, 1.07) | 0.84 (0.66, 1.07) | 0.84 (0.65, 1.08) |

| 20% versus 10% | 0.85 (0.67, 1.08) | 0.86 (0.67, 1.10) | 0.86 (0.65, 1.13) |

| 30% versus 10% | 0.86 (0.66, 1.11) | 0.87 (0.63, 1.19) | 0.88 (0.58, 1.32) |

| 40% versus 20% | 0.86 (0.67, 1.10) | 0.86 (0.65, 1.15) | 0.87 (0.63, 1.20) |

| Based on Berruti trial data | |||

| 10% versus 10% | 0.87 (0.71, 1.07) | 0.88 (0.71, 1.08) | 0.89 (0.72, 1.10) |

| 20% versus 10% | 0.85 (0.69, 1.05) | 0.84 (0.67, 1.05) | 0.83 (0.65, 1.04) |

| 30% versus 10% | 0.84 (0.67, 1.05) | 0.81 (0.62, 1.06) | 0.78 (0.56, 1.09) |

| 40% versus 20% | 0.84 (0.67, 1.05) | 0.82 (0.64, 1.05) | 0.81 (0.62, 1.06) |

The analysis based on the Berruti trial data is more promising in that the predicted HRs do become smaller as the pCR rates differ between the treatment arms (bottom panel of Table 3). However, the association is not large. For example, with a control treatment with an observed 10% pCR rate, the predicted EFS HR ranges from 0.87 to 0.85 to 0.84 if the observed pCR rate is 10%, 20%, or 30% in the experimental treatment arm, respectively, in a RCT with 100 patients. In addition, the prediction intervals are very wide. For example, even with a 1000 patient trial, the prediction interval for the EFS HR is (0.72, 1.10) if the pCR rates are the same in the treatment arms, and is (0.56, 1.09) if the pCR rate is tripled in the experimental arm (30% versus 10%). These analyses indicate that currently available evidence does not support pCR as a good trial-level surrogate for EFS. An analogous analysis is presented in supplementary Appendix, available at Annals of Oncology online, for using pCR as a surrogate for OS (supplementary Tables S4–S6, available at Annals of Oncology online), and it is seen that current evidence also does not support pCR as a good trial-level surrogate for OS.

pCR as an intermediate screening end point

Frequently, intermediate end points are used to screen new treatments in phase II trials for possible future development in larger phase III trials. Historically, single-arm trials of single cytotoxic agents were assessed in patients having metastatic disease, with objective tumor responses viewed as sufficient phase II evidence of biologic activity. More recently, randomized phase II trials have been used to allow for the screening of combinations of a new agent with a standard agent (which is expected to produce some responses by itself) or for the screening of agents where beneficial clinical activity is not necessarily expected to cause tumor responses (in which case a screening end point like progression-free survival might be appropriate) [16]. Unlike a surrogate end point, the purpose of a screening end point is not to recommend new treatments for the community based on its trial results, but instead to recommend such treatments for further evaluation in phase III trials. It is expected that some treatments that show activity with the screening end point will turn out to not have clinical benefit when tested in phase III. However, one should be confident that if a treatment shows no benefit in the screening end point, then it is very unlikely it would show clinical benefit using a definitive clinical end point. If this is not the case, good treatments could be screened out before a definitive evaluation.

We now address whether pCR could be used as a randomized phase II screening end point. Table 4 presents for the 23 Cortazar/Berruti trials the trial-level EFS and OS data ordered by the trial-level OR for pCR, and the one-sided upper 95% CIs for the EFS and OS HRs. In order to use pCR as a screening variable, one needs to have a cutoff such that experimental treatments with pCR ORs (versus control treatments) less than this cutoff are deemed uninteresting. In general, such a cutoff is somewhat arbitrary (with a large number of trials one could use statistical methods to attempt to identify it), but in the present case it would be reasonable to say that the OR ≤1.25 are small. However, if one eliminated the 12 treatments with pCR ORs ≤1.25, then one would be eliminating some potentially interesting treatments (studies H, D, and G). Our conclusion is that the Cortazar/Berruti data do not support a claim that pCR is a useful screening variable.

Table 4.

Trial-level results (comparisons between treatment arms) for 23 treatment-arm comparisons ordered by increasing pCR odds ratio

| Triala | pCR odds ratiob | EFS |

OS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRc | Upper 95% CI for HR | HRc | Upper 95% CI for HR | ||

| m | 0.66 | 0.90 | 2.12 | 1.26 | 3.63 |

| k | 0.68 | 1.05 | 1.33 | 1.01 | 1.32 |

| i | 0.72 | 0.82 | 1.11 | 0.82 | 1.14 |

| H | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 1.23 |

| l | 0.93 | 0.91 | 1.50 | 0.67 | 1.49 |

| C | 0.96 | 0.88 | 1.15 | 0.84 | 1.19 |

| d | 1.00 | 1.18 | 1.73 | 1.41 | 2.31 |

| j | 1.02 | 1.05 | 1.44 | 0.76 | 1.13 |

| A | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.36 | 0.81 | 1.13 |

| D | 1.11 | 0.84 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 1.10 |

| f | 1.23 | 1.03 | 1.40 | 1.19 | 1.75 |

| G | 1.25 | 0.75 | 0.91 | 0.76 | 1.01 |

| E | 1.50 | 0.87 | 1.15 | 0.80 | 1.17 |

| a | 1.53 | 0.71 | 1.09 | 0.89 | 1.36 |

| b | 1.59 | 0.77 | 1.26 | 0.87 | 1.55 |

| B | 2.10 | 1.12 | 1.41 | 1.02 | 1.40 |

| I | 2.17 | 0.71 | 0.93 | 0.69 | 0.99 |

| F | 2.24 | 0.89 | 1.04 | 0.92 | 1.13 |

| h | 2.47 | 0.97 | 2.08 | 0.18 | 0.85 |

| g | 2.94 | 0.72 | 1.08 | 0.64 | 1.04 |

| c | 3.00 | 0.41 | 0.90 | 0.40 | 2.43 |

| J | 3.04 | 0.67 | 1.02 | 0.60 | 1.09 |

| e | 3.17 | 0.73 | 1.15 | 0.77 | 1.31 |

aTrial letter designations are given in the supplementary Appendix, available at Annals of Oncology online. Capital letters represent trials used in the Cortazar analysis. The inclusion of trials in this table is described in the supplementary Appendix, available at Annals of Oncology online.

bAn OR >1 means that the observed pCR rate for the experimental treatment was higher (better) than for the standard treatment.

cA HR <1 means that the observed EFS for the experimental treatment was longer (better) than for the standard treatment.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

discussion

With the results from 23 trials, many of which have relatively few events, it can be hard to assess a relationship between trial results for a putative surrogate end point and a definitive end point. In addition, the data for 13 of the 23 trials presented in Berruti et al. [4] were based on summary outcome measures (HRs, OR) extracted from the literature, as opposed to the summary measures derived from the individual-level data on the 10 trials analyzed by Cortazar et al. [3]. The latter approach is preferable for a number of reasons, including the ability to calculate summary measures in a uniform way and to use consistent inclusion/exclusion criteria applied to the trials [17]. However, it is logistically more difficult to obtain individual-level data from completed trials. In general, collecting more trial data over time can become problematic because (i) the mechanisms of action of the new agents may change over time (so that a convincing surrogate relationship seen in an old class of agents may not hold for agents in a new class), and (ii) as more effective second-line and salvage treatments become available, a previously seen surrogate association with OS may be diminished as the OS is extended for all patients regardless of the treatments being assessed in trials [18].

The pCR trial-level data analyzed here fail to provide evidence that one can confidently recommend a treatment of general clinical use based solely on a positive pCR trial result, or eliminate a new agent from further drug development based on a negative trial result for pCR. The possibility remains that by acquiring more trial data and restricting the patient population or agents considered that a meaningful association of pCR results with EFS or OS trial results would be seen. However, in doing so, there is a risk of finding spurious associations due to multiple comparisons in many subclasses of agents and subsets of the population. An appropriate trial-level surrogacy analysis taking the multiple comparisons into account would be required. In addition, restrictions on the patient population or agents considered would mean that pCR surrogacy would be established only in these limited circumstances, potentially making it less useful. Unless and until persuasive evidence can be obtained to establish the reliability of pCR as a surrogate or screening end point in some setting, neoadjuvant RCTs should continue to follow patients to observe definitive long-term end points that are integral to accepted measures of clinical benefit.

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

references

- 1.Prowell TM, Pazdur R. Pathological complete response and accelerated drug approval in early breast cancer. New Engl J Med 2012; 366: 2438–2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Pathological complete response in neoadjuvant treatment of high-risk early-stage breast cancer: use as an endpoint to support accelerated approval. Silver Spring, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch M, et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet 2014; 384: 164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berruti A, Amoroso V, Gallo F, et al. Pathologic complete response as a potential surrogate for the clinical outcome in patients with breast cancer after neoadjuvant therapy: a meta-regression of 29 randomized prospective studies. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 3883–3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Holmes AP, Baselga J, et al. First results from the phase III ALTTO trial (BIG 2–06; NCCTG [Alliance] N063D) comparing one year of anti-HER2 therapy with lapatinib alone, trastuzumab alone, their sequence, or their combination in the adjuvant treatment of HER2-positive early breast cancer. In ASCO Annual Meeting Abstract LBA4. Presented 1 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baselga J, Bradbury I, Eidtmann H, et al. Lapatinib with trastuzumab for HER2-positive early breast cancer (NeoALTTO): a randomized open-label, multicenter, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2012; 379: 633–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Azambuja E, Holmes AP, Piccart-Gebhart M, et al. Lapatinib with trastuzumab for HER2-positive early breast cancer (NeoALTTO): survival outcomes of a randomized open-label, multicenter, phase 3 trial and their association with pathological complete response. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1137–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sledge G. Neoadjuvant doesn't predict adjuvant in breast cancer. Cancer Lett 2014; 40: 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeMichele A, Yee D, Berry DA, et al. The neoadjuvant model is still the future for drug development in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 2911–2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry D. In NeoALTTO & ALTTO trials, neoadjuvant response predicts adjuvant. Cancer Lett 2014; 40: 1, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berry D. Rejoinder to “Neoadjuvant doesn't predict adjuvant in breast cancer". Cancer Lett 2014; 40: 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berry DA, Hudis CA. Neoadjuvant therapy in breast cancer as a basis for drug approval. JAMA Oncol 2015; 1: 875–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buyse M, Molensberghs G, Burzykowski T, et al. The validation of surrogate endpoints in meta-analyses of randomized experiments. Biostatistics 2000; 1: 49–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korn EL, Albert PS, McShane LM. Assessing surrogates as trial endpoints using mixed models. Stat Med 2005; 24: 163–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prentice RL. Surrogate endpoints in clinical trials: definition and operational criteria. Stat Med 1989; 8: 431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubinstein LV, Korn EL, Freidlin B, et al. Design issues of randomized phase II trials and a proposal for phase II screening trials. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 7199–7206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. BMJ 2010; 340: 521–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buyse M, Molenberghs G, Paeoletti X, et al. Statistical evaluation of surrogate endpoints with examples from cancer clinical trials. Biom J 2015. Feb 12 [epub ahead of print], doi:10.1002/bimj.201400049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.