Abstract

Significance

Diabetes and its complications represent a major socioeconomic problem.

Recent Advances

Changes in the balance of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) play an important role in the pathogenesis of β-cell dysfunction that occurs in response to type 1 and type 2 diabetes. In addition, changes in H2S homeostasis also play a role in the pathogenesis of endothelial injury, which develop on the basis of chronically or intermittently elevated circulating glucose levels in diabetes.

Critical Issues

In the first part of this review, experimental evidence is summarized implicating H2S overproduction as a causative factor in the pathogenesis of β-cell death in diabetes. In the second part of our review, experimental evidence is presented supporting the role of H2S deficiency (as a result of increased H2S consumption by hyperglycemic cells) in the pathogenesis of diabetic endothelial dysfunction, diabetic nephropathy, and cardiomyopathy.

Future Directions

In the final section of the review, future research directions and potential experimental therapeutic approaches around the pharmacological modulation of H2S homeostasis in diabetes are discussed.

Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a colorless, flammable, water-soluble gas with the characteristic smell of rotten eggs. Until recently, H2S was viewed primarily as a toxic gas and environmental hazard. However, research conducted over the last decade demonstrates that H2S is synthesized by mammalian tissues, and it serves various important regulatory functions (8, 41, 60, 61). There are multiple lines of evidence showing that H2S modulates the function of β cells as well as that H2S modulates and possibly mediates the injury of β cells, which underlies the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. Similarly, multiple lines of evidence implicate that changes in H2S homeostasis contribute to the pathogenesis of endothelial dysfunction induced by elevated extracellular glucose. Endothelial dysfunction is a central process in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications, because it is directly connected to the pathogenesis of various diabetic complications, including vascular dysfunction, neuropathy, nephropathy, retinopathy, and heart failure (27, 62). The current article provides an overview of the experimental evidence implicating H2S as a pathophysiological effector in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes and in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications in vitro and in vivo.

H2S Regulates β Cell Function and Vascular Function

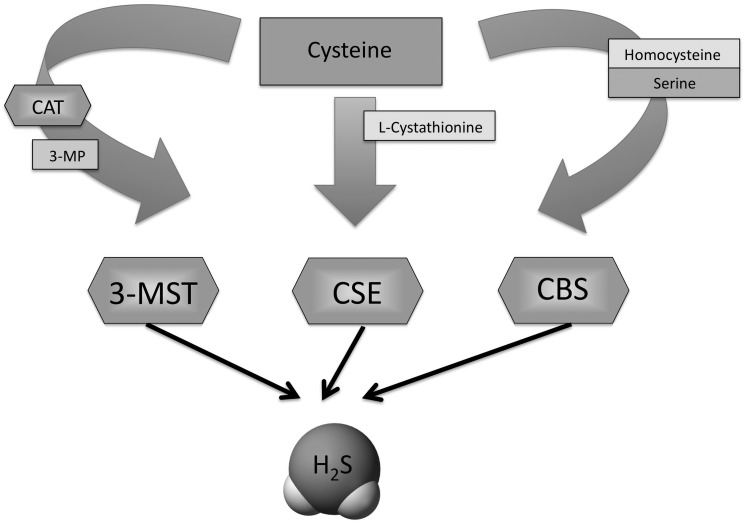

A growing body of data accumulating over the last decade shows that H2S is synthesized by mammalian tissues via two cytosolic pyridoxal-5′-phosphate-dependent enzymes responsible for metabolism of l-cysteine—cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE)—as well as by a mitochondrial third pathway involves the production from l-cysteine of H2S via the combined action of 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase and cysteine aminotransferase (8, 41, 60, 61) (Fig. 1). As a gaseotransmitter, H2S rapidly travels through cell membranes without utilizing specific transporters and exerts a host of biological effects on a variety of biological targets resulting in a variety of biological responses. Similarly to the other two gaseotransmitters (nitric oxide and carbon monoxide), many of the biological responses to H2S follow a biphasic dose–response: the effects of H2S range from physiological, cytoprotective effects (which occur at low concentrations) to cytotoxic effects (which are generally only apparent at higher concentrations) (60). Depending on the experimental system studied, the molecular mechanisms of the biological actions of H2S include antioxidant effects, both via direct chemical reactions with various oxidant species, as well as via increased cellular glutathione levels via activation/expression of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase; modulation of intracellular caspase and kinase pathways; stimulatory effects on the production of cyclic AMP and modulation of intracellular calcium levels; as well as opening of potassium-opened ATP channels (KATP channels) (41, 60, 61).

FIG. 1.

Schematic presentation of the three hydrogen sulfide (H2S)-producing enzymes. H2S is synthesized by mammalian cells tissues via two cytosolic pyridoxal-5′-phosphate-dependent enzymes responsible for metabolism of l-cysteine: cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), as well as by a mitochondrial third pathway involves the production from l-cysteine of H2S via the combined action of 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST) and cysteine aminotransferase (CAT).

The biological roles of endogenous H2S are multiple and rapidly expanding. Its regulatory functions span the central and peripheral nervous system, the regulation of cellular metabolism, regulation of immunological/inflammatory responses, and various aspects of cardiovascular biology (21, 41, 60, 61). For the purpose of the current article, we restrict our discussion to a brief overview the physiological roles of H2S in the endocrine pancreas (relevant for the pathogenesis of diabetic β-cell injury) and in the vascular endothelium (relevant for the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiovascular complications).

In the pancreas, both CSE and CBS are involved in the production of H2S (40). The production of high levels of H2S has been demonstrated in pancreatic β-cell lines (1, 40, 76). For instance, H2S production in homogenates of rat (INS-1E) and hamster (HIT-T15) β-cell lines was demonstrated in the presence of l-cysteine (1, 76). Significant H2S production was also reported in the mouse insulin-secreting cell line MIN6 (40). Interestingly, expression of CSE, but not CBS, dramatically increased in the islet cells after glucose stimulation, resulting in increased H2S production in these cells (39). In contrast, glucose stimulation has been reported to decrease the H2S-producing activity in the homogenates of INS-1E cells (76). The contradictory effects of glucose on H2S production may be due to species-specific differences in the conditions for gene induction of CSE and/or cell-type differences. Although the precise functional role of H2S in pancreatic β-cells remains to be investigated in additional detail, according to most studies, intraislet H2S exerts a physiological inhibitory effect on insulin release (1, 40, 41, 76]. This inhibition occurs via multiple mechanisms (opening of KATP channels, decrease of cellular ATP levels, and regulation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration) (1, 46): the relative contribution of these mechanisms remains to be clarified.

In the cardiovascular system, the principal enzyme involved in the formation of H2S is CSE, expressed in vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and cardiac myocytes (41, 60, 61). The vascular regulatory roles of H2S include vasodilatation, vascular protection, and the stimulation of angiogenesis (59, 75). The multiple roles of H2S in vascular and cardiac physiology have been subject of recent reviews (41, 59–61).

Role of H2S in the Pathogenesis of Autoimmune β-Cell Death in Type 1 Diabetes

Type 1 diabetes (or insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus) is an autoimmune disease occurring predominantly in children and young adults resulting in destruction of the pancreatic β-cells. It is characterized by prolonged periods of hyperglycemia, via reduced uptake of glucose and relative increase in glucagon secretion and gluconeogenesis. The destruction of the islet β-cells is caused by an autoimmune attack involving an initial hyperexpression of class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules by all of the islet endocrine cells, which is followed by β-cell exclusive expression of MHC class II molecules. Expression of the MHC proteins induces an insulitis, whereby the islet is islet infiltrated by mononuclear cells, including lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells. The actual trigger for the process of β-cell destruction is still unknown, but it has been proposed that it is an external factor (viral, chemical) or an internal stimulus (cytokines, free radical) which damages a proportion of the β-cells, leading to release of specific β-cell proteins, which can be taken up by antigen presenting cells and processed to antigenic peptides (37, 38, 70).

The potential role of H2S in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes was initially investigated using in vitro model systems. These investigations yielded somewhat conflicting results, presumably due to the substantial differences in the experimental conditions employed, as well as the biphasic nature of the pharmacological actions of H2S that include cytoprotection at lower concentrations, as well as cytotoxicity at higher local levels (60). Yang and colleagues have demonstrated that H2S administration or CSE overexpression results in the expression of endoplasmatic reticulum (ER)-stress-related molecules and apoptosis in rat insulinoma INS-1E cells, and showed that this effect was mediated by p38 MAP kinase activation (76). The same group later demonstrated that streptozotocin-induced death of the same insulinoma cells can be prevented by pharmacological inhibition of CSE, indicating an active pro-apoptotic role of endogenously produced H2S in this system and it occurs via the activation of ER stress as well as mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases (76). In contrast, other groups have reported that H2S may act as a cytoprotective hormone in mouse islets and in MIN6 cells exposed to high glucose, fatty acids, or a mixture of cytotoxic cytokines (39, 64). The cytoprotective effects included both a protection from loss of viability, and a prevention of the deterioration of insulin secretion in response to elevated glucose (64).

Only a limited number of studies have investigated the role of H2S in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes in vivo. Moore and colleagues demonstrated the induction of H2S-producing enzyme CBS (but not of CSE) in the pancreas of animals treated with the β-cell toxin streptozotocin (79). Moreover, in Zucker diabetic fatty rats (a diabetic model with obesity and hyperinsulinemia), CSE expression was found to be upregulated in the islets (73). Overall, these observations suggested that intrapancreatic or intraislet H2S production is increasing in various models of diabetes. The question, then arose, whether this increase in intraislet H2S biosynthesis is part of a protective mechanism (whereby increased H2S levels counteract the increased oxidative/nitrosative stress conditions during the process of islet cell death), or, alternatively, is it part of the pathophysiology of the disease (suppressing insulin production and contributing to β-cell destruction)? Studies from Wang's laboratory have recently provided evidence for the latter pathomechanism (74). Using pharmacological tools (dl-propargylglycine, a pharmacological inhibitor of CSE) an improvement of glycemic control was demonstrated in the Zucker diabetic model (73). Similarly, treatment of mice subjected to streptozotocin-diabetes with the CSE inhibitor dl-propargylglycine protected the animals from hyperglycemia and hypoinsulinemia (74). Finally, CSE knockout mice subjected to streptozotocin exhibited a delayed onset of diabetic status (74). Histopathological evaluation of the pancreas of these animals revealed that CSE-deficient animals maintained a larger number of functional β-cells and maintained higher intraislet insulin levels (74).

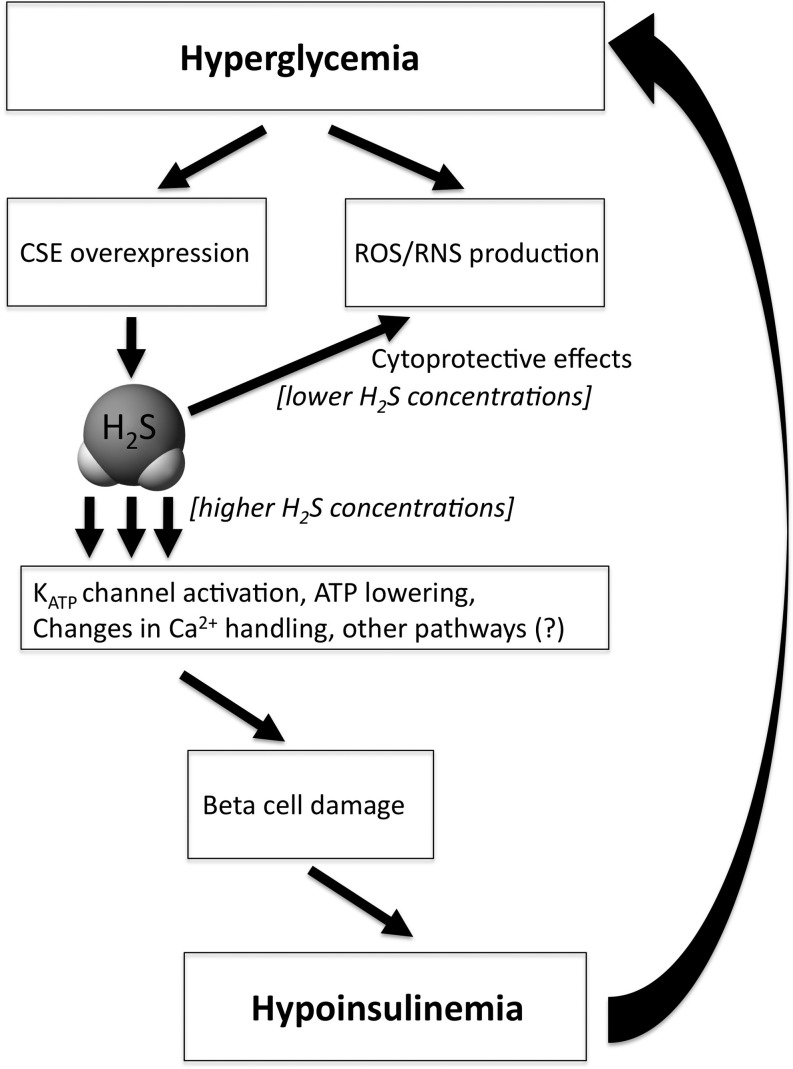

How, then, can one reconcile the contrasting (cytoprotective or cytotoxic) effects of H2S in the in vitro islet studies with the in vivo studies demonstrating overexpression of H2S-producing enzymes in the islets of animals that develop diabetes, and with the in vivo studies showing that CSE inhibition or CSE deficiency protects against the onset of diabetes in the streptozotocin model? Why would the body purposefully overexpress a cytotoxic hormone in its β-cells, thereby actively contributing to their destruction? Although much more work needs to be conducted to address all mechanistic aspects of the process, we propose the following working hypothesis (Fig. 2). We hypothesize that in the early stage of diabetes development, a high-glucose-induced pancreatic CSE overexpression may serve as a protective mechanism, because it may neutralize oxidative/nitrosative stress and autoimmune attack. However, as a by-product of this process, an increase in intraislet H2S production may lead to an inhibition of insulin production via KATP channel activation, and the resulting increase in circulating glucose may lead to progressive β-cell toxicity. We further speculate that—as this positive feedback cycle amplifies—local levels of H2S may reach a threshold concentration where an autocrine-type cytotoxic response may be induced. This response may be especially prominent on a background of an oxidant-mediated and autoimmune attack against the β-cell (i.e., in a cell that has weakened cellular defenses). Ultimately, the above processes may culminate a progressive destruction (apoptosis) of the β-cells. However, it must be noted that there are marked species differences in the regulation of CSE expression in islets (65). For instance, H2S production can be increased by hyperglycemia, which has been observed in mouse islets and MIN6 cells (65), but not in rat insulinoma cells (80). It should be also noted that the hypothesis that increased production of H2S is eventually toxic ex vivo has been proven in rat INS-1E insulinoma cells (76) but not in normal mouse islets or MIN6 cells (39, 64). Thus, the above working hypothesis as well as additional mechanistic details of the role of H2S in diabetic β-cell destruction need to be further elucidated in future studies.

FIG. 2.

A working hypothesis depicting the cytoprotective and cytotoxic roles of H2S in the β-cell during diabetes development. We hypothesize that in the early stage of diabetes development, a high-glucose-induced pancreatic CSE overexpression may serve as a protective mechanism, because it may neutralize oxidative/nitrosative stress and autoimmune attack. However, as a by-product of this process, an increase in intraislet H2S production may lead to an inhibition of insulin production via potassium-opened ATP channels (KATP) channel activation, and the resulting increase in circulating glucose may lead to progressive β-cell toxicity, which, ultimately, results in a lowering of circulating insulin levels. We further speculate that—as this positive feedback cycle amplifies—local levels of H2S may reach a threshold concentration where an autocrine-type cytotoxic response may be induced. This response may be especially prominent on a background of an oxidant-mediated and autoimmune attack against the β-cell. Ultimately, the above processes may culminate a progressive destruction (apoptosis) of the β-cells, leading to hypoinsulinemia and further hyperglycemia. ROS, reactive oxygen species; RNS, reactive nitrogen species.

Role of H2S in the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Complications

The quality of life and life expectations of diabetic patients are determined by the complications of the disease. Endothelial dysfunction is a well-documented complication in various forms of diabetes, and in prediabetic individuals. The pathogenesis of this endothelial dysfunction includes increased polyol pathway flux, altered cellular redox state, increased formation of diacylglycerol, activation of specific protein kinase C isoforms, and accelerated nonenzymatic formation of advanced glycation endproducts (27, 62). Many of these pathways trigger the production of oxygen- and nitrogen-derived oxidants and free radicals, such as superoxide anion and peroxynitrite, and activation of the nuclear enzyme poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), which play a significant role in the pathogenesis of the diabetes-associated endothelial dysfunction and other diabetic complications. While the cellular sources of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anion are multiple and include advanced glycation endproducts, NADH/NADPH oxidases, the mitochondrial respiratory chain, xanthine oxidase, the arachidonic acid cascade, and microsomal enzymes, a dysregulated mitochondrial electron transport chain is increasingly being recognized as the central effector in this process (27, 62).

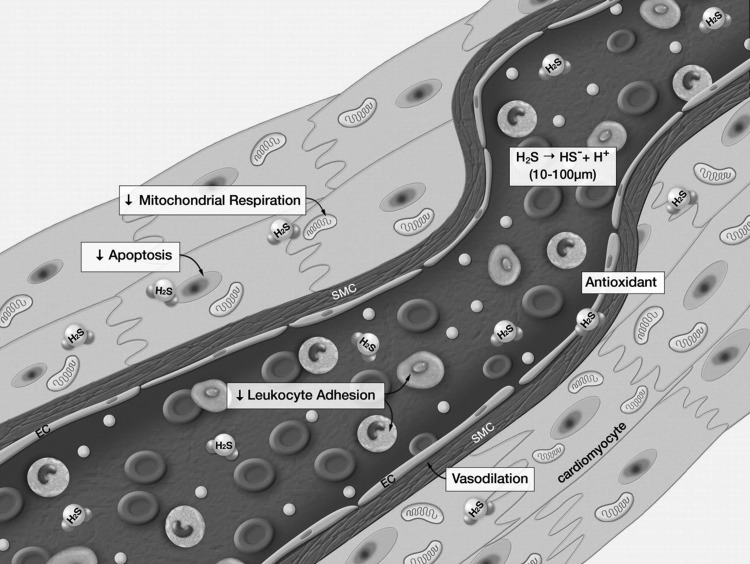

H2S plays multiple protective roles in the vascular system, effecting vasodilatation, angiogenesis, inhibition of leukocyte adhesion, and cell death processes (Fig. 3) (45). In the context of hyperglycemic endothelial dysfunction, it is important to consider the local, biologically active levels of H2S that the blood vessels actually experience. As discussed in the previous section, several studies suggested the induction of H2S-producing enzymes CBS and/or CSE in the pancreas in rats treated with the pro-diabetic β-cell toxin streptozotocin (79), and similar findings pertain to the liver and kidney of streptozotocin-diabetic rats (78, 79). On the other hand, Denizalti and colleagues failed to demonstrate significant alterations in CSE mRNA in the thoracic aorta of rats subjected to diabetes (14), and our recent study failed to demonstrate any notable changes in the expression of CSE or CBS in the brain, heart, kidney, lung, liver, or thoracic aorta of rats subjected to streptozotocin diabetes (58). Thus, H2S-producing enzymes may or may not become upregulated in various models of diabetes, perhaps depending on the experimental model and/or the severity of the disease (but it appears that they are certainly not down-regulated). In contrast to these enzyme expression data, however, the circulating H2S levels in animal models of diabetes are either decreased, as shown in studies using streptozotocin-model of diabetes (33, 58) and in a study by using the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse model (5) or tend to decrease (as seen in another streptozotocin-diabetic rat model) (79). Furthermore, lower circulating H2S levels have been detected in plasma samples of type 2 diabetic patients by two independent groups of investigators (33, 71).

FIG. 3.

Summary of the physiological actions of H2S in blood vessels. H2S is produced in the cardiovascular system and exerts a number of critical effects on the cardiovascular system. H2S has been shown to induce vasodilation and inhibit leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in the circulation. H2S is a potent antioxidant and inhibits cellular apoptosis. H2S also has been shown to transiently and reversibly inhibit mitochondrial respiration. Taken together, this physiological profile is ideally suited for protection of the cardiovascular system against disease states. Reproduced with permission from ref. (45).

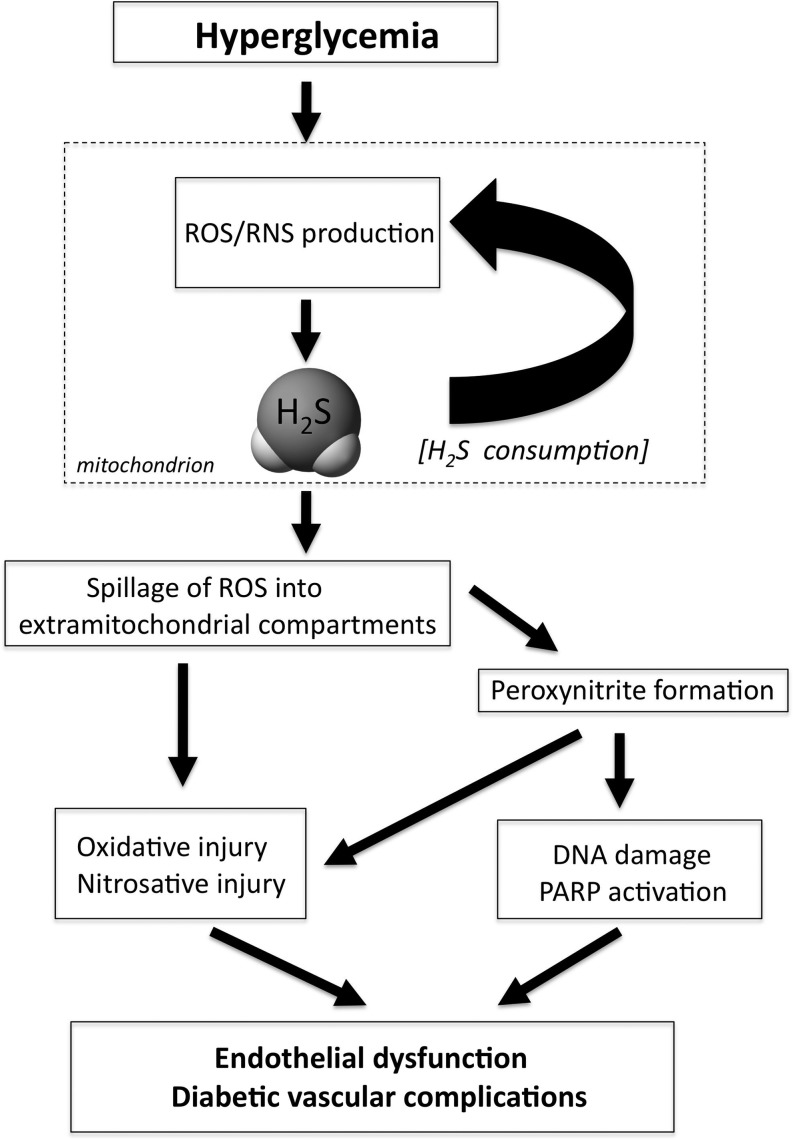

This paradox of the unchanged or potentially increased tissue H2S production versus the lower circulating H2S may be resolved by our recent studies demonstrating that hyperglycemic endothelial cells show an increased rate of H2S consumption due to ROS generation (58). We know from the original studies of Kraus and colleagues that production and consumption of H2S is a dynamic process in tissues (16). We have recently observed that endothelial cells placed in elevated glucose conditions consume both exogenous and endogenous H2S compared to cells that are grown in normal extracellular glucose (58). This accelerated H2S consumption can be reduced by either treatment of the cells with ROS scavengers, or treatment with mitochondrial uncoupling agents, pointing to the importance of mitochondrially derived ROS in this process (58). The pathophysiological implication of the above findings is that in hyperglycemia, the increased mitochondrial ROS production is the cause of a relative H2S deficiency in endothelial cells.

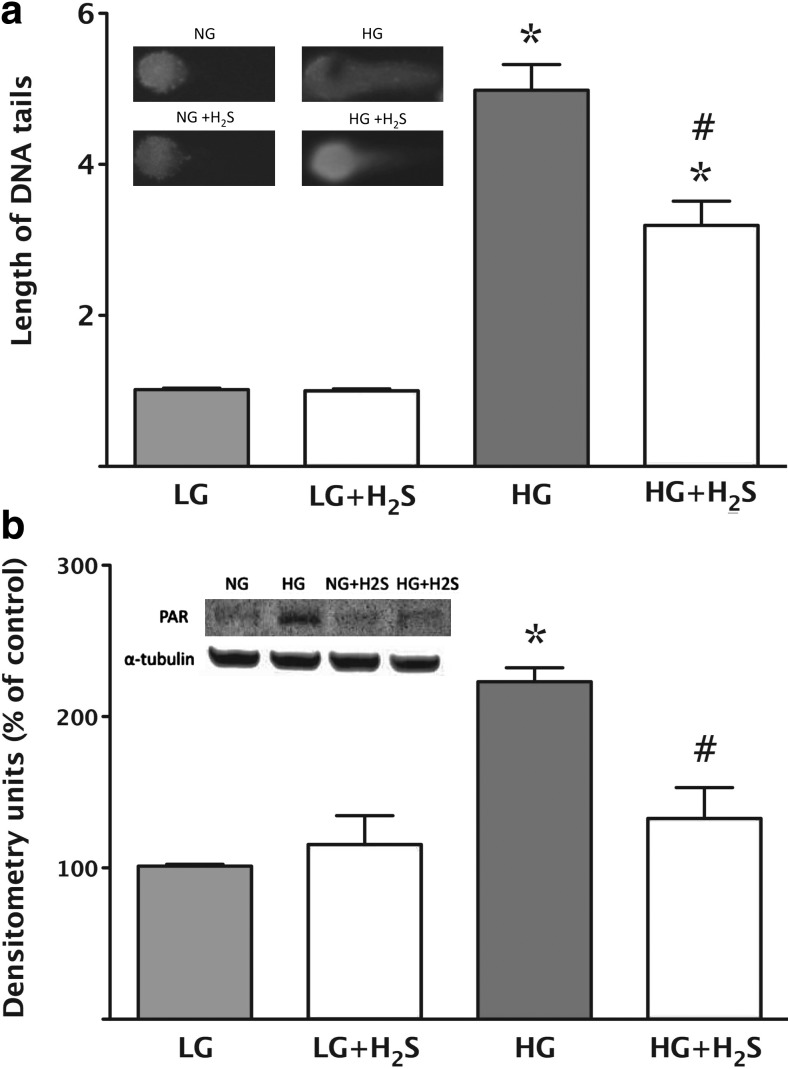

The next question, then, became, whether modulation of endothelial H2S levels (either by inhibiting it or by supplementing it) affects hyperglycemic endothelial cells functionally. We have shown that inhibition of H2S production (by CSE siRNA silencing) exacerbates ROS production in hyperglycemic endothelial cells, while supplementation/replacement of H2S (either by pharmacological means or by adenoviral overexpression of CSE) reduces mitochondrial ROS production and protects the cells from hyperglycemic cell dysfunction (58). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that H2S provides a physiological reducing/antioxidant intracellular environment within the endothelial cells, which helps to maintain normal mitochondrial function (58). Our results suggest that this balance becomes perturbed when mitochondrial ROS production is stimulated by hyperglycemia. We hypothesized, therefore, that the ROS from hyperglycemic mitochondria directly reacts with and consumes the intracellular H2S, which then creates additional mitochondrial dysfunction, possibly by oxidative modification to mitochondrial proteins and proposed that such a positive feed-forward cycle may then culminate in a dysfunctional mitochondrial state where molecular oxygen is utilized to produce ROS (as opposed to ATP), and where mitochondrial efficacy is diminished (58). Our data indicate that the above sequence of events, ultimately, leads to a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and, finally, a spillage of ROS to the cytosolic and nuclear compartments, which contributes to the development of hyperglycemic endothelial cell dysfunction (Fig. 4) (58). One of the pathways that are then triggered is the activation of the nuclear enzyme PARP, which—as demonstrated in previous studies (26, 51)—is known to lead to an impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxations in hyperglycemia and diabetes. The activation of this enzyme, as well as the degree of DNA breakage (which is the proximal cause of PARP activation), is attenuated by H2S in hyperglycemic endothelial cells (Fig. 5) (58). Taken together, the data show that supplementation of H2S to hyperglycemic endothelial cells exerts marked protective effects. Similar conclusions were drawn by an independent group of investigators, who have demonstrated that treatment with H2S protects human umbilical vein endothelial cells against high glucose-induced apoptosis (29).

FIG. 4.

Proposed scheme of H2S/ROS interactions in hyperglycemic endothelial cells. In normal endothelial cells, physiological production of H2S (as well as many other antioxidant systems) protects against oxidative stress generated by the mitochondria, and mitochondrial ROS do not spill over to the cytosolic or nuclear compartment. When cells are placed in elevated glucose, mitochondrial ROS production gradually consumes H2S. This process, coupled with the depletion of other antioxidant defenses, eventually culminates in the spillage of ROS into the cytosolic and nuclear compartments. ROS production, ultimately, on its own, or by combining with nitric oxide (NO) to form peroxynitrite (ONOO−), activates multiple pathways of diabetic complications, such as the nuclear enzyme poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), the polyol pathway, the advanced glycation endproduct system (AGE), protein kinase C (PKC), and the hexosamine system. Supplementation of H2S can protect against these processes.

FIG. 5.

Replacement of H2S attenuates cellular responses that lay downstream from hyperglycemic mitochondrial ROS production in bEnd.3 endothelial cells. (a) DNA strand breakage was measured in low (5.5 mM, LG) or high (40 mM, HG) glucose conditions at 7 days using the Comet assay. High glucose induced an increase in DNA strand breakage as compared with low glucose (*p<0.05) and H2S (300 μM) afforded a significant suppression of this response (#p<0.05). In the inset, representative images are shown for the four respective groups (LG/HG with and without 300 μM H2S). (b) Activation of the nuclear enzyme PARP was measured by detection of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymers using western blotting. High glucose induced an increase in PARP activation (*p<0.05) and H2S (300 μM) afforded a suppression of this response (#p<0.05). In the insert a representative western blot is shown for the four respective groups (low and high glucose with and without 300 μM H2S). Reproduced with permission from ref. (58).

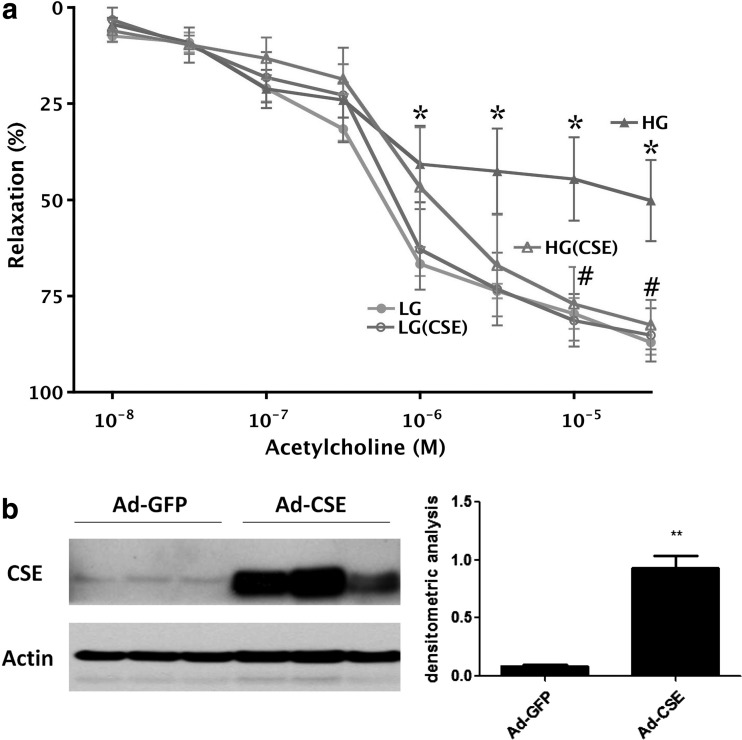

We next investigated what functional role does the modulation (inhibition or supplementation) of H2S production have on the loss of endothelium-dependent relaxant function in hyperglycemic or diabetic blood vessels. One of the simplest models to study diabetic vascular dysfunction is to incubate isolated vascular rings in elevated extracellular glucose, followed by the measurement of isometric contractions and relaxations. Using this system, we have demonstrated that the absence of vascular H2S production (i.e., rings from CSE deficient mice) accelerates the development of endothelial dysfunction in rings placed into elevated extracellular glucose, whereas supplementation of H2S by pharmacological supplementation or by overexpressing CSE (Fig. 6) protects the blood vessels against this process (58).

FIG. 6.

CSE overexpression protects against the development of endothelial dysfunction in thoracic aortic rings placed in elevated extracellular glucose. (a) Rat aortic rings were incubated in low (5.5 mM, LG) or high (40 mM, HG) glucose for 48 h. High glucose induced a suppression of endothelium-dependent relaxant responses (*p<0.05), an effect that was attenuated in the rings overexpressing CSE (#p<0.05). n=4. (b) Depicts representative western blots and densitometric analysis for CSE in rings exposed to adenovirus expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) or CSE. **p<0.01 shows a significant upregulation of CSE. Reproduced with permission from ref. (58).

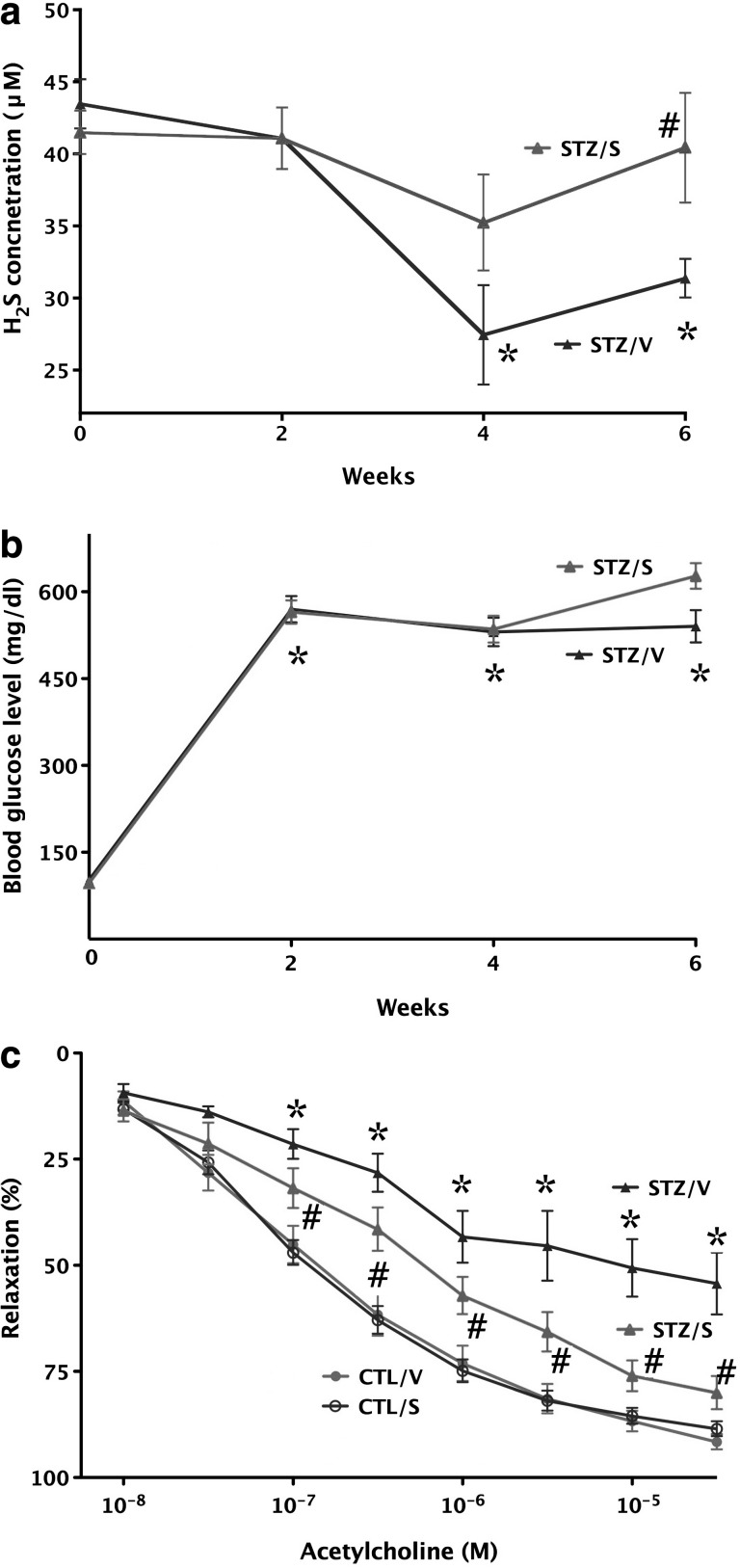

The protection of H2S by diabetic cardiac or vascular dysfunction can also be demonstrated in vivo, in rodent models of diabetes. In a rat model of streptozotocin-induced diabetes, we have recently demonstrated that supplementation of H2S (applied by a H2S-releasing minipump) corrects the decrease in plasma H2S levels, and improves the endothelium-dependent relaxant responses of the thoracic aorta ex vivo, without affecting the degree of hyperglycemia (Fig. 7) (58). Likewise, in an independent study focusing on diabetic renal dysfunction, treatment of streptozotocin-diabetic rats with intraperitoneal H2S reduced the diabetes-induced increases in blood urea nitrogen levels, and attenuated renal collagen and tumor growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) expression (78), without affecting the degree of hyperglycemia. Furthermore, in a streptozotocin model of diabetic cardiomyopathy, intraperitoneal or oral administration of H2S was found to reduce myocardial hypertrophy, improved the histological picture of the diabetic hearts, and reduced the degree of fibrosis (19). These effects were associated with marked reductions in the up-regulation of matrix metalloproteinase 2 and TGF-β1 in the hearts of H2S-treated diabetic animals. Furthermore, H2S therapy resulted in an improved antioxidant status, evidenced by elevated levels of glutathione levels and reduced levels of myocardial hydroxyproline (19). However, in contrast to our study, the study of El-Seweidy and colleagues found that H2S therapy also improved the diabetic status (evidenced by reduced degree of hyperglycemia and increased levels of insulin and C-peptide). Thus, the improvements in myocardial improvements in this study may not be due to a direct effect of H2S to the inflammatory and redox processes in the myocardium, but may be due to the reduced degree of hyperglycemia in the H2S-treated animals. The differing effects of H2S on the streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemia are unclear and require additional investigation; as noted above, in two out of three studies, no effect was seen (58, 78), whereas in one study, there was an improvement of diabetic status (19). Taken together, the above data suggest a protective effect of H2S against diabetic vasculopathy, nephropathy, and cardiomyopathy. These effects may be mediated by antioxidant effects as well as by the suppression of pro-fibrotic mediator expression.

FIG. 7.

Improvement of endothelial function by H2S in diabetic rats ex vivo. (a) Streptozotocin-diabetic vehicle-treated rats (STZ/V) exhibit reduced blood H2S levels (*p<0.05), an effect that is normalized by supplementation of H2S using the H2S-releasing minipumps (STZ/S; #p<0.05). (b) The streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemic response is unaffected by H2S-releasing minipumps: *p<0.05 shows significant and comparable degree of hyperglycemia in STZ rats treated with vehicle or H2S-releasing pumps, compared to initial blood glucose values. (c) The thoracic aortas of streptozotocin-diabetic rats (STZ/V) exhibit reduced endothelium-dependent relaxant function in response to acetylcholine (1 nM–30 μM; *p<0.05); supplementation of H2S using the H2S-releasing minipumps (STZ/S) attenuated the degree of this endothelial dysfunction (#p<0.05). Reproduced with permission from ref. (58).

H2S and Diabetes: Unanswered Questions and Future Directions

The field of H2S and diabetes, or H2S and diabetic complications is a new and expanding research area. The sections below represent a partial list of open questions and potential future research directions.

The conflict of H2S-mediated protection versus cytotoxicity in β-cells

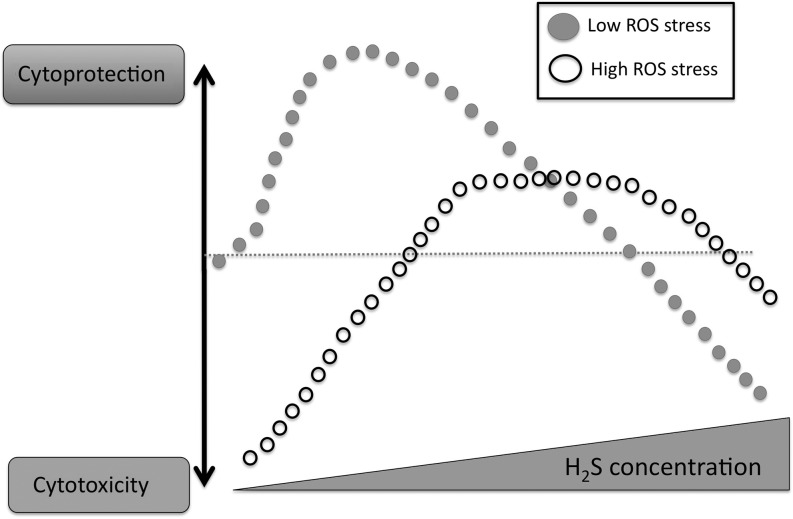

As it is apparent from the earlier section of this review, there is a clear conflict in the field as to whether H2S is cytoprotective or cytotoxic in β-cells in vitro. H2S exerts biphasic responses to cell viability (lower concentrations tends to be cytoprotective, while higher concentrations begin to exert cytotoxicity). While it is likely that the full range of cytoprotective or cytotoxic mechanisms of H2S are not fully understood, a number of mechanisms have been identified to contribute to both the pro-survival/cytoprotective effects of H2S, and to the cytotoxic effects. Cytoprotective mechanisms include various direct and indirect antioxidant/redox/based mechanisms (10, 34, 35); upregulation of antioxidant pathways and mechanisms such as thioredoxin (35), Nrf2 (9, 24), and Hsp90 (77); modulation of cytoprotective kinase pathways (43); and possibly a direct energetic mechanism whereby H2S can donate electrons to mitochondrial Complex II, thereby enhancing ATP formation (28, 42). Cytotoxic mechanisms include pro-oxidative cellular responses and the depletion of antioxidants (17, 68), release of free intracellular iron, DNA injury, and the inhibition of mitochondrial Complex IV, resulting in the inhibition of mitochondrial function (3, 31, 48, 66) (Fig. 8). As far as the effects of H2S in β-cells, however, a concentration-based explanation can give a only partial answer, as the concentrations used in the available reports do not necessarily support the above simplistic view. While cell type differences, cell culture conditions, times of exposure, and other conditions may explain some of these differences, a bigger question remains to be answered: Does H2S in vivo in pancreatic β-cell exert cytotoxic or cytoprotective effects?

FIG. 8.

Cytotoxic/cytoprotective effects of H2S. Under low oxidative stress conditions, H2S exerts cytoprotective effects at low concentrations, but becomes cytotoxic at higher concentrations. However, under high levels of baseline oxidative/nitrosative stress, H2S exerts cytoprotective effects. See text for more detailed delineation of the pathways/mechanisms involved in each response.

The role of H2S in diabetic β-cell destruction

Further to the last point, additional work needs to be conducted on the role of endogenously produced H2S in the pathogenesis of autoimmune β-cell destruction. From the recent study of Wang and colleagues using a streptozotocin model of diabetes in mice, it appears that intraislet H2S, in part produced in direct response to streptozotocin action on islet cell KATP channels, induces intraislet H2S production, which then contributes to the death of the β-cells (74). However, the streptozotocin model (while it is an acceptable model of diabetic hyperglycemia and associated complications) is an imperfect model to study the development of β-cell destruction; autoimmune models are generally considered closer to the human disease. Currently, there are no interventional studies on the role of H2S in the pathogenesis of diabetes in autoimmune models of diabetes (such as the NOD model); a cross of the CSE-deficient mice with the NOD mice may answer this question.

The regulation of H2S-producing enzymes in diabetes

As discussed earlier, there are conflicting reports in the literature as to whether CSE and/or CBS is upregulated in diabetes; in some studies no change was seen; in others an upregulation was reported. It is possible that these alterations are cell type- and tissue-dependent; it is also possible that these alterations are different at different times or different severity of the disease; these questions as well as the actual molecular regulation of these enzymes on the signal transduction and transcription/translational level need to be investigated in additional detail in future studies.

The levels of H2S in biological fluids in general and in diabetes in specific

One of the biggest controversies in the field of H2S relates to the quantification of biological levels of H2S. As discussed in several articles, the absolute value of the H2S level in extracellular fluids or in plasma depends on the experimental method used (e.g., derivatization of H2S with monobromobimane, or other methods, or measurement using the methylene blue assay, or free H2S gas measurements using headspace analysis, or readings taken by H2S electrode), as well as the tissue type studied, with vascular tissues exhibiting substantially high levels than many other tissues (46, 49, 56, 72). While the current review cannot offer a clear resolution to this discrepancy, it is important to emphasize that further work is needed to resolve this issue, and, in the meantime, the method of detection must be taken into significant consideration when interpreting the data obtained by various groups and methodologies. As far as H2S levels in diabetes, it appears to be consistent across most animal models of diabetes, as well as the small amount of human data, that H2S levels decrease in the circulation. However, in the diabetic Zucker rats (an animal model of type 2 diabetes), apparently the circulating H2S levels are increased (73): the relevance of this finding is not known at the moment. Additional work needs to be done to determine the effect of diabetes specifically on the free forms of H2S in the circulation. Both animals and humans exhale significant amounts of H2S (32, 67); measurements of exhaled H2S in diabetic animals or patients with diabetes may be a possible approach to address this question. Further work also needs to be conducted to determine the exact role of obesity versus diabetic status on the modulation of circulating H2S levels; a recent study suggests that obesity is a significant independent contributing factor to lower circulating H2S levels in diabetes (71).

Another, rather contentious issue to be mentioned here, which also relates to the discrepancy of the biological levels of H2S, is the amount of biologically relevant H2S in studies where it is supplemented/added to cells or tissues. Given the fact that there is no clear agreement in the literature as to what the endogenous concentrations of H2S are, it is hard to determine what concentration of H2S can be considered physiological when added to cells or tissues. Clearly, the published concentrations of H2S (including the studies discussed in the current review) range from low μM to several hundreds of μM. It must be noted, however, that these concentrations represent initial and extracellular concentrations. When H2S is added to culture medium, its concentration rapidly decreases due to a combination of outgassing, reaction with oxygen and oxidants in the medium, as well as due to biological decomposition (active metabolism) by the cells. Although the intracellular concentrations have not yet been measured, we can assume that they are substantially lower than the initial, extracellular concentrations that the experimenters have started out with. Clearly, much additional work is required to resolve this issue.

The molecular details of the regulation by H2S of the hyperglycemic endothelial dysfunction

Our recent studies (58) have demonstrated that hyperglycemic endothelial cell damage is exacerbated in the absence of endogenous H2S and is protected by H2S supplementation. We have investigated several intracellular processes (mitochondrial ROS formation, mitochondrial membrane permeability transition, switch between oxidative phosphorylation, and glycolysis), and a limited number of downstream processes (DNA damage and PARP activation), but the potential regulation by H2S of many additional pathways relevant to diabetic complications remain to be explored (activation of pro-inflammatory signaling, activation of protein kinase C, upregulation of pro-fibrotic mediators, potential changes in mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial fission, etc.) In addition, the nature of the high glucose-induced mitochondrial dysfunction (e.g., specific transcriptional or post-translational changes to specific mitochondrial proteins), and the potential regulation by H2S of these processes remains to be elucidated.

The functional consequences of the regulation by H2S of diabetic endothelial dysfunction on the development of diabetic complications

While several lines of very interesting data start to emerge showing that H2S improves diabetic vasculopathy (58), nephropathy (78), and cardiomyopathy (19), there are no published data so far on the potential effect of H2S on diabetic retinopathy, diabetic erectile dysfunction, and the accelerated atherosclerosis in diabetes. Even in the published models, there are some significant gaps. The data on vasculopathy are currently restricted on macrovasculature (but not microvasculature) (58), the data on cardiomyopathy are restricted on histological and biochemical alterations (lacking functional data, e.g., myocardial contractility) (19), and the data on nephropathy are, in some respects, functionally inconclusive (e.g., H2S appears to normalize blood urea nitrogen levels but apparently does not affect creatinine levels) (78). Studies in autoimmune diabetes models (e.g., the NOD mice or the db/db mice) are also needed. In addition, the therapeutic window of the action of H2S (pretreatment vs. post-treatment, intermittent treatments, rebound effects after discontinuation, etc.) needs to be investigated, and longer-term studies need to be performed.

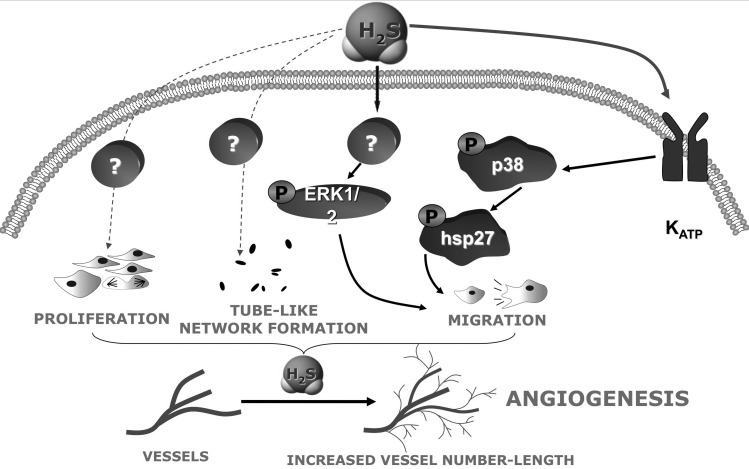

Regulation of angiogenesis by H2S: potential relevance for diabetic retinopathy, diabetic wound healing, and diabetic foot disease

Emerging data support the role of H2S in the regulation of angiogenesis. Addition of H2S promotes endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation, while inhibition of H2S production attenuates these processes (Fig. 9) (6, 53, 59). Furthermore, the pro-angiogenic effect of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is mediated by the endogenous production of H2S; pharmacological inhibition or siRNA knock-down of CSE attenuates VEGF-induced angiogenesis (53). Finally, wound healing is accelerated after H2S supplementation, while it is delayed in the CSE-deficient mice, when compared to corresponding wild-type animals (53). The H2S-mediated angiogenic phenomena have not yet been investigated under the conditions of hyperglycemia or diabetes, and this remains an interesting future research direction. One can speculate that inhibition of H2S biosynthesis may have uses in hyperproliferative conditions (perhaps inhibition of H2S biosynthesis may have a therapeutic utility in diabetic retinopathy), whereas H2S supplementation may have a therapeutic utility to improve wound healing in diabetic patients.

FIG. 9.

Pathways involved in the pro-angiogenic effects of H2S in endothelial cells. Further work needs to determine whether diabetes/hyperglycemia modulates these pathways.

The potential protective effect of H2S against myocardial reperfusion injury in diabetic patients

Diabetic patients have an increased incidence of myocardial infarction and other acute cardiac events, at least in part due to increased oxidative/nitrosative stress (15). In this context it is interesting to mention that H2S administration exerts marked protective effects in rodent and large animal models of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (20, 57, 63), and that H2S elicits cardioprotection by myocardial pre and postconditioning (9, 36, 52). According to a recent report, H2S also exerts cardioprotection against myocardial reperfusion in diabetic rats (25). Much additional work needs to be conducted in this area in order to expand on these findings, and to study the effect of H2S in diabetic animals in reperfusion injury of organs other than the heart, on the development of congestive cardiomyopathy, as well as on the process of postischemic angiogenesis. It also needs to be investigated whether or not the preconditioning effect of H2S is maintained in diabetes, because it is known that the efficacy of many preconditioning approaches is diminished in diabetes (13, 23).

Role of H2S in the development of insulin resistance in diabetes and in metabolic syndrome

Although several studies have begun to characterize the potential role of H2S in the regulation of tissue glucose uptake, in insulin resistance, the body of the published literature is inconclusive and conflicting. In an in vitro study, H2S was found to inhibit glucose uptake into adipocytes (22). Furthermore, in an insulin resistance model in rats induced by fructose feeding, a negative correlation was found between glucose uptake into fat tissue and the amount of H2S produced by the same tissue (22). These data would argue for a potential active role of H2S in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance, and would possibly suggest that pharmacological inhibition of H2S may be a possible therapeutic approach. This notion, however, is not supported by a second report where H2S was not found to have any effect on the development of insulin resistance in diabetic rats (54). Clearly, additional studies need to be conducted to bring clarity and mechanistic insight into this very important area.

Conclusions and Therapeutic Implications

It appears that inhibition of pancreatic H2S biosynthesis emerges as a potential approach to protect β-cells from destruction during the induction phase of diabetes, whereas supplementation/donation of H2S emerges as a potential approach to maintain diabetic blood vessel patency, and possibly to protect against the development of diabetic complications such as diabetic nephropathy and cardiomyopathy.

The therapeutic inhibition of H2S biosynthesis to prevent diabetes onset appears to be problematic for several reasons. First, there are no potent and therapeutically applicable inhibitors of CSE; the available inhibitors are of low (millimolar) potency, and of questionable selectivity. Second, there are no good ways to predict autoimmune attack to the β-cell; in fact, the various interventional studies conducted so far that aimed to prevent diabetes onset have not been very successful (30, 69). Clearly, much more work needs to be done in this area to develop a valid therapeutic concept.

The therapeutic donation of H2S, on the other hand, may be more straightforward. There are a number of compounds that have been synthesized specifically to deliver therapeutic H2S to tissues (7, 47). Some of these molecules are stand-alone H2S donors; others are combined molecules where an existing drug molecule is coupled with a H2S-donating group. It may be an interesting research direction to test some of these compounds in experimental models of diabetic complications. Additionally, a report by Benavides and colleagues has demonstrated that certain polysulfide molecules contained in garlic release biologically active H2S upon reaction with tissue glutathione (4). Subsequent studies have demonstrated that these polysulfides release H2S in vivo (32) and that they exert cardioprotective potential therapeutic effects via the release of H2S (12, 44, 55). In fact, there are several articles in the literature reporting the beneficial effects of garlic extracts in various models of diabetic complications and wound healing (2, 11, 18, 50). However, in these studies the specific role of H2S as a mediator of these therapeutic actions remains to be investigated.

Abbreviations Used

- AGE

advanced glycation endproduct system

- CAT

cysteine aminotransferase

- CBS

cystathionine β-synthase

- CSE

cystathionine γ-lyase

- ER

endoplasmatic reticulum

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HG

high glucose

- H2S

hydrogen sulfide

- KATP channels

potassium-opened ATP channels

- LG

low glucose

- MAP kinase

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- 3-MST

mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOD

nonobese diabetic

- ONOO−

peroxynitrite

- PARP

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PKC

protein kinase C

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- STZ

streptozotocin

- TGF-β1

tumor growth factor β1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Acknowledgments

The work of C.S. is supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation and the Shriners Hospitals for Children. The editorial assistance of Lili Szabo is appreciated.

Author Disclosure Statement

C.S. has stock ownership in Ikaria, Inc., a for-profit organization involved in the development of H2S-based therapies.

References

- 1.Ali MY. Whiteman M. Low CM. Moore PK. Hydrogen sulphide reduces insulin secretion from HIT-T15 cells by a KATP channel-dependent pathway. J Endocrinol. 2007;195:105–112. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baluchnejadmojarad T. Roghani M. Endothelium-dependent and -independent effect of aqueous extract of garlic on vascular reactivity on diabetic rats. Fitoterapia. 2003;74:630–637. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(03)00158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baskar R. Li L. Moore PK. Hydrogen sulfide-induces DNA damage and changes in apoptotic gene expression in human lung fibroblast cells. FASEB J. 2007;21:247–255. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6255com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benavides GA. Squadrito GL. Mills RW. Patel HD. Isbell TS. Patel RP. Darley-Usmar VM. Doeller JE. Kraus DW. Hydrogen sulfide mediates the vasoactivity of garlic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17977–17982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705710104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brancaleone V. Roviezzo F. Vellecco V. De Gruttola L. Bucci M. Cirino G. Biosynthesis of H2S is impaired in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:673–680. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai WJ. Wang MJ. Moore PK. Jin HM. Yao T. Zhu YC. The novel proangiogenic effect of hydrogen sulfide is dependent on Akt phosphorylation. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caliendo G. Cirino G. Santagada V. Wallace JL. Synthesis and biological effects of hydrogen sulfide (H2S): development of H2S-releasing drugs as pharmaceuticals. J Med Chem. 2010;53:6275–6286. doi: 10.1021/jm901638j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calvert JW. Coetzee WA. Lefer DJ. Novel insights into hydrogen sulfide-mediated cytoprotection. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:1203–1217. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calvert JW. Jha S. Gundewar S. Elrod JW. Ramachandran A. Pattillo CB. Kevil CG. Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide mediates cardioprotection through Nrf2 signaling. Circ Res. 2009;105:365–374. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carballal S. Trujillo M. Cuevasanta E. Bartesaghi S. Möller MN. Folkes LK. García-Bereguiaín MA. Gutiérrez-Merino C. Wardman P. Denicola A. Radi R. Alvarez B. Reactivity of hydrogen sulfide with peroxynitrite and other oxidants of biological interest. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.10.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang SH. Liu CJ. Kuo CH. Chen H. Lin WY. Teng KY. Chang SW. Tsai CH. Tsai FJ. Huang CY. Tzang BS. Kuo WW. Garlic oil alleviates MAPKs- and IL-6-mediated diabetes-related cardiac hypertrophy in STZ-induced DM rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:950150. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neq075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chuah SC. Moore PK. Zhu YZ. S-allylcysteine mediates cardioprotection in an acute myocardial infarction rat model via a hydrogen sulfide-mediated pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2693–H2701. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00853.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Valle HF. Lascano EC. Negroni JA. Crottogini AJ. Absence of ischemic preconditioning protection in diabetic sheep hearts: role of sarcolemmal KATP channel dysfunction. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;249:21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denizalti M. Bozkurt TE. Akpulat U. Sahin-Erdemli I. Abacioglu N. The vasorelaxant effect of hydrogen sulfide is enhanced in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2011;383:509–517. doi: 10.1007/s00210-011-0601-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Filippo C. Cuzzocrea S. Rossi F. Marfella R. D'Amico M. Oxidative stress as the leading cause of acute myocardial infarction in diabetics. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 2006;24:77–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2006.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doeller JE. Isbell TS. Benavides G. Koenitzer J. Patel H. Patel RP. Lancaster JR., Jr. Darley-Usmar VM. Kraus DW. Polarographic measurement of hydrogen sulfide production and consumption by mammalian tissues. Anal Biochem. 2005;341:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eghbal MA. Pennefather PS. O'Brien PJ. H2S cytotoxicity mechanism involves reactive oxygen species formation and mitochondrial depolarisation. Toxicology. 2004;203:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ejaz S. Chekarova I. Cho JW. Lee SY. Ashraf S. Lim CW. Effect of aged garlic extract on wound healing: a new frontier in wound management. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2009;32:191–203. doi: 10.1080/01480540902862236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Seweidy MM. Sadik NA. Shaker OG. Role of sulfurous mineral water and sodium hydrosulfide as potent inhibitors of fibrosis in the heart of diabetic rats. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;506:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elrod JW. Calvert JW. Morrison J. Doeller JE. Kraus DW. Tao L. Jiao X. Scalia R. Kiss L. Szabo C. Kimura H. Chow CW. Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15560–15565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elsey DJ. Fowkes RC. Baxter GF. Regulation of cardiovascular cell function by hydrogen sulfide. Cell Biochem Funct. 2010;28:95–106. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng X. Chen Y. Zhao J. Tang C. Jiang Z. Geng B. Hydrogen sulfide from adipose tissue is a novel insulin resistance regulator. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;380:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferdinandy P. Schulz R. Baxter GF. Interaction of cardiovascular risk factors with myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, preconditioning, and postconditioning. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:418–458. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.06002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francis RC. Vaporidi K. Bloch KD. Ichinose F. Zapol WM. Protective and detrimental effects of sodium sulfide and hydrogen sulfide in murine ventilator-induced lung injury. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:1012–1021. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823306cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao Y. Yao X. Zhang Y. Li W. Kang K. Sun L. Sun X. The protective role of hydrogen sulfide in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion-induced injury in diabetic rats. Int J Cardiol. 2011;152:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia Soriano F. Virag L. Jagtap P. Szabo E. Mabley JG. Liaudet L. Marton A. Hoyt DG. Murthy KG. Salzman AL. Southan GJ. Szabo C. Diabetic endothelial dysfunction: the role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation. Nat Med. 2001;7:108–113. doi: 10.1038/83241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giacco F. Brownlee M. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ Res. 2010;107:1058–1070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goubern M. Andriamihaja M. Nübel T. Blachier F. Bouillaud F. Sulfide, the first inorganic substrate for human cells. FASEB J. 2007;21:1699–1706. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7407com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guan Q. Zhang Y. Yu C. Liu Y. Gao L. Zhao J. Hydrogen sulfide protects against high glucose-induced apoptosis in endothelial cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;152:177–183. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31823b4915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haller MJ. Atkinson MA. Schatz DA. Efforts to prevent and halt autoimmune β cell destruction. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hildebrandt TM. Modulation of sulfide oxidation and toxicity in rat mitochondria by dehydroascorbic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:1206–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Insko MA. Deckwerth TL. Hill P. Toombs CF. Szabo C. Detection of exhaled hydrogen sulphide gas in rats exposed to intravenous sodium sulphide. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:944–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain SK. Bull R. Rains JL. Bass PF. Levine SN. Reddy S. McVie R. Bocchini JA. Low levels of hydrogen sulfide in the blood of diabetes patients and streptozotocin-treated rats causes vascular inflammation? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:1333–1337. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeney V. Komódi E. Nagy E. Zarjou A. Vercellotti GM. Eaton JW. Balla G. Balla J. Supression of hemin-mediated oxidation of low-density lipoprotein and subsequent endothelial reactions by hydrogen sulfide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:616–623. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jha S. Calvert JW. Duranski MR. Ramachandran A. Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury: role of antioxidant and antiapoptotic signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H801–H806. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00377.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ji Y. Pang QF. Xu G. Wang L. Wang JK. Zeng YM. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide postconditioning protects isolated rat hearts against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;587:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson JD. Luciani DS. Mechanisms of pancreatic β-cell apoptosis in diabetes and its therapies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;654:447–462. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-3271-3_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaminitz A. Stein J. Yaniv I. Askenasy N. The vicious cycle of apoptotic β-cell death in type 1 diabetes. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:582–589. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaneko Y. Kimura T. Taniguchi S. Souma M. Kojima Y. Kimura Y. Kimura H. Niki I. Glucose-induced production of hydrogen sulfide may protect the pancreatic β-cells from apoptotic cell death by high glucose. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaneko Y. Kimura Y. Kimura H. Niki I. L-cysteine inhibits insulin release from the pancreatic β-cell: possible involvement of metabolic production of hydrogen sulfide, a novel gasotransmitter. Diabetes. 2006;55:1391–1397. doi: 10.2337/db05-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide: its production, release and functions. Amino Acids. 2011;41:113–121. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lagoutte E. Mimoun S. Andriamihaja M. Chaumontet C. Blachier F. Bouillaud F. Oxidation of hydrogen sulfide remains a priority in mammalian cells and causes reverse electron transfer in colonocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:1500–1511. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lan A. Liao X. Mo L. Yang C. Yang Z. Wang X. Hu F. Chen P. Feng J. Zheng D. Xiao L. Hydrogen sulfide protects against chemical hypoxia-induced injury by inhibiting ROS-activated ERK1/2 and p38MAPK signaling pathways in PC12 cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lavu M. Bhushan S. Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide-mediated cardioprotection: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011;120:219–229. doi: 10.1042/CS20100462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lefer DJ. A new gaseous signaling molecule emerges: cardioprotective role of hydrogen sulfide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17907–17908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709010104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levitt MD. Abdel-Rehim MS. Furne J. Free and acid-labile hydrogen sulfide concentrations in mouse tissues: anomalously high free hydrogen sulfide in aortic tissue. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:373–378. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martelli A. Testai L. Breschi MC. Blandizzi C. Virdis A. Taddei S. Calderone V. Hydrogen sulphide: novel opportunity for drug discovery. Med Res Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/med.20234. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nicholls P. Inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase by sulphide. Biochem Soc Trans. 1975;3:316–319. doi: 10.1042/bst0030316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olson KR. Is hydrogen sulfide a circulating “gasotransmitter” in vertebrate blood? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:856–863. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ou HC. Tzang BS. Chang MH. Liu CT. Liu HW. Lii CK. Bau DT. Chao PM. Kuo WW. Cardiac contractile dysfunction and apoptosis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats are ameliorated by garlic oil supplementation. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:10347–10355. doi: 10.1021/jf101606s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pacher P. Liaudet L. Soriano FG. Mabley JG. Szabo E. Szabo C. The role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation in the development of myocardial and endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:514–521. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pan TT. Chen YQ. Bian JS. All in the timing: a comparison between the cardioprotection induced by H2S preconditioning and post-infarction treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;616:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Papapetropoulos A. Pyriochou A. Altaany Z. Yang G. Marazioti A. Zhou Z. Jeschke MG. Branski LK. Herndon DN. Wang R. Szabo C. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous stimulator of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21972–21977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908047106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel M. Shah G. Possible role of hydrogen sulfide in insulin secretion and in development of insulin resistance. J Young Pharm. 2010;2:148–151. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.63156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaik IH. George JM. Thekkumkara TJ. Mehvar R. Protective effects of diallyl sulfide, a garlic constituent, on the warm hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury in a rat model. Pharm Res. 2008;25:2231–2242. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9601-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen X. Pattillo CB. Pardue S. Bir SC. Wang R. Kevil CG. Measurement of plasma hydrogen sulfide in vivo and in vitro. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:1021–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sodha NR. Clements RT. Feng J. Liu Y. Bianchi C. Horvath EM. Szabo C. Stahl GL. Sellke FW. Hydrogen sulfide therapy attenuates the inflammatory response in a porcine model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:977–984. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.08.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suzuki K. Olah G. Modis K. Coletta C. Kulp G. Gero D. Szoleczky P. Chang T. Zhou Z. Wu L. Wang R. Papapetropoulos A. Szabo C. Hydrogen sulfide replacement therapy protects the vascular endothelium in hyperglycemia by preserving mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13829–13834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105121108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Szabo C. Papapetropoulos A. Hydrogen sulfide and angiogenesis: mechanisms and applications. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:853–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Szabo C. Gaseotransmitters: new frontiers for translational science. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:59ps54. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Szabo C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:917–935. doi: 10.1038/nrd2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Szabo C. Role of nitrosative stress in the pathogenesis of diabetic vascular dysfunction. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:713–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Szabo G. Veres G. Radovits T. Gero D. Modis K. Miesel-Gröschel C. Horkay F. Karck M. Szabo C. Cardioprotective effects of hydrogen sulfide. Nitric Oxide. 2011;25:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taniguchi S. Kang L. Kimura T. Niki I. Hydrogen sulphide protects mouse pancreatic β-cells from cell death induced by oxidative stress, but not by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:1171–1178. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taniguchi S. Niki I. Significance of hydrogen sulfide production in the pancreatic beta-cell. J Pharmacol Sci. 2011;116:1–5. doi: 10.1254/jphs.11r01cp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thompson RW. Valentine HL. Valentine WM. Cytotoxic mechanisms of hydrosulfide anion and cyanide anion in primary rat hepatocyte cultures. Toxicology. 2003;188:149–159. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Toombs CF. Insko MA. Wintner EA. Deckwerth TL. Usansky H. Jamil K. Goldstein B. Cooreman M. Szabo C. Detection of exhaled hydrogen sulphide gas in healthy human volunteers during intravenous administration of sodium sulphide. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:626–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Truong DH. Mihajlovic A. Gunness P. Hindmarsh W. O'Brien PJ. Prevention of hydrogen sulfide-induced mouse lethality and cytotoxicity by hydroxocobalamin (vitamin B12a) Toxicology. 2007;242:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Belle TL. Coppieters KT. von Herrath MG. Type 1 diabetes: etiology, immunology, and therapeutic strategies. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:79–118. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watson D. Loweth AC. Oxidative and nitrosative stress in β-cell apoptosis: their contribution to β-cell loss in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Br J Biomed Sci. 2009;66:208–215. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2009.11730278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whiteman M. Gooding KM. Whatmore JL. Ball CI. Mawson D. Skinner K. Tooke JE. Shore AC. Adiposity is a major determinant of plasma levels of the novel vasodilator hydrogen sulphide. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1722–1726. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wintner EA. Deckwerth TL. Langston W. Bengtsson A. Leviten D. Hill P. Insko MA. Dumpit R. VandenEkart E. Toombs CF. Szabo C. A monobromobimane-based assay to measure the pharmacokinetic profile of reactive sulphide species in blood. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:941–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu L. Yang W. Jia X. Yang G. Duridanova D. Cao K. Wang R. Pancreatic islet overproduction of H2S and suppressed insulin release in Zucker diabetic rats. Lab Invest. 2009;89:59–67. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang G. Tang G. Zhang L. Wu L. Wang R. The pathogenic role of cystathionine γ-lyase/hydrogen sulfide in streptozotocin-induced diabetes in mice. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:869–879. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang G. Wu L. Jiang B. Yang W. Qi J. Cao K. Meng Q. Mustafa AK. Mu W. Zhang S. Snyder SH. Wang R. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science. 2008;322:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1162667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang G. Yang W. Wu L. Wang R. H2S, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and apoptosis of insulin-secreting β cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16567–16576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang Z. Yang C. Xiao L. Liao X. Lan A. Wang X. Guo R. Chen P. Hu C. Feng J. Novel insights into the role of HSP90 in cytoprotection of H2S against chemical hypoxia-induced injury in H9c2 cardiac myocytes. Int J Mol Med. 2011;28:397–403. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yuan P. Xue H. Zhou L. Qu L. Li C. Wang Z. Ni J. Yu C. Yao T. Huang Y. Wang R. Lu L. Rescue of mesangial cells from high glucose-induced over-proliferation and extracellular matrix secretion by hydrogen sulfide. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2119–2126. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yusuf M. Kwong Huat BT. Hsu A. Whiteman M. Bhatia M. Moore PK. Streptozotocin-induced diabetes in the rat is associated with enhanced tissue hydrogen sulfide biosynthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:1146–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang L. Yang G. Tang G. Wu L. Wang R. Rat pancreatic level of cystathionine γ-lyase is regulated by glucose level via specificity protein 1 (SP1) phosphorylation. Diabetologia. 2011;54:2615–2625. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2187-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]