Abstract

Background and Aims Experimental drought is well documented to induce a decline in photosynthetic capacity. However, if given time to acclimate to low water availability, the photosynthetic responses of plants to low soil moisture content may differ from those found in short-term experiments. This study aims to test whether plants acclimate to long-term water stress by modifying the functional relationships between photosynthetic traits and water stress, and whether species of contrasting habitat differ in their degree of acclimation.

Methods Three Eucalyptus taxa from xeric and riparian habitats were compared with regard to their gas exchange responses under short- and long-term drought. Photosynthetic parameters were measured after 2 and 4 months of watering treatments, namely field capacity or partial drought. At 4 months, all plants were watered to field capacity, then watering was stopped. Further measurements were made during the subsequent ‘drying-down’, continuing until stomata were closed.

Key Results Two months of partial drought consistently reduced assimilation rate, stomatal sensitivity parameters (g1), apparent maximum Rubisco activity () and maximum electron transport rate (). Eucalyptus occidentalis from the xeric habitat showed the smallest decline in and ; however, after 4 months, and had recovered. Species differed in their degree of acclimation. Eucalyptus occidentalis showed significant acclimation of the pre-dawn leaf water potential at which the and ‘true’ Vcmax (accounting for mesophyll conductance) declined most steeply during drying-down.

Conclusions The findings indicate carbon loss under prolonged drought could be over-estimated without accounting for acclimation. In particular, (1) species from contrasting habitats differed in the magnitude of V′cmax reduction in short-term drought; (2) long-term drought allowed the possibility of acclimation, such that V′cmax reduction was mitigated; (3) xeric species showed a greater degree of V′cmax acclimation; and (4) photosynthetic acclimation involves hydraulic adjustments to reduce water loss while maintaining photosynthesis.

Keywords: Drought acclimation, photosynthesis, water stress, Vcmax, Jmax, water use efficiency, stomatal conductance, mesophyll conductance, Huber value, hydraulic adjustment, riparian Eucalyptus camaldulensis, xeric Eucalyptus occidentalis

INTRODUCTION

Drought duration and intensity are predicted to increase in future in some regions, particularly in Mediterranean and subtropical climates (IPCC, 2014). The mechanisms underlying plant response to water stress are different for different time scales of stress (Maseda and Fernández, 2006). Short-term water stress reduces plant photosynthesis (A) through limitation of stomatal conductance (gs) and/or mesophyll conductance to CO2 (gm) (Bota et al., 2004; Flexas et al., 2004, 2006, 2012; Grassi and Magnani, 2005; Egea et al., 2011; Galmés et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2013, 2014), reduction of the maximum carboxylation rate (Vcmax) (Kanechi et al., 1996; Castrillo et al., 2001; Parry et al., 2002; Tezara, 2002; Zhou et al., 2013, 2014) and/or reduction of the maximum electron transport rate (Jmax) (Tezara et al., 1999; Thimmanaik et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2014). Zhou et al. (2014) reported that short-term water stress led to concurrent stomatal, mesophyll and biochemical limitations on photosynthesis, while species from contrasting hydro-climates differed in the drought sensitivity of each process – reflecting inherent differences in drought tolerance.

During longer-term water stress in long-lived plants such as trees, acclimation can take place, rendering the xylem less vulnerable to cavitation. Acclimation to long-term drought can include adjustments at different levels, including leaf physiology, anatomy, morphology, chemical composition, xylem hydraulics, growth and/or carbon partitioning among organs (Maseda and Fernández, 2006; Limousin et al., 2010a, b; Martin-StPaul et al., 2012, 2013). However, much of our knowledge about plant drought responses comes from short-term studies, and thus does not include acclimation responses (Cano et al., 2014). In particular, process-based models of vegetation function typically predict drought effects on trees based on the drought-induced diffusional and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis found in short-term experiments (e.g. Verhoef and Egea, 2014), meaning that they may overestimate the long-term drought impacts if acclimation of these responses occurs.

Although many studies demonstrate acclimation to long-term water stress (e.g. Nogués and Alegre, 2002; Guarnaschelli et al., 2006; Rodriguez-Calcerrada et al., 2011; Ogle et al., 2015), relatively few have examined whether acclimation includes a modification of the functional relationships between photosynthetic traits and water stress, and those few that have, disagree. Limousin et al. (2010b) and Misson et al. (2010) compared the responses of Quercus ilex exposed to different manipulative precipitation regimes for several years in the field, and found high sensitivity of gs, gm, Vcmax and Jmax to decreased pre-dawn leaf water potential but the functional relationships were not affected by the drought treatment. In contrast, Martin-StPaul et al. (2012) compared the responses of three populations of Q. ilex in sites differing in mean annual rainfall, and found steeper declines of gs, gm, Vcmax and Jmax as pre-dawn leaf water potential declined in the wettest site compared with the drier sites. Limousin et al. (2013) also found acclimation of the functional responses in a long-term precipitation manipulation experiment in Pinus edulis and Juniperus monosperma.

Another important but largely unexplored question is whether species of contrasting habitat differ in their degree of acclimation in photosynthetic traits during long-term water stress. Cano et al. (2014) reported that long-term water stress led to decreased mesophyll limitation in a xeric species, but not mesic species. A synthesis study by Choat et al. (2012) showed that vulnerability to drought is equally high in plants from both mesic and xeric ecosystems, despite soil water availability being lower in xeric ecosystems – indicating that there must be important differences between the responses of mesic and xeric species to prolonged drought.

In this paper, we test three general hypotheses on the long-term water stress impacts on photosynthesis of contrasting tree species: (1) long-term water stress should allow the possibility of acclimation, such that the diffusional and/or biochemical limitations found in short-term water stress are mitigated; (2) relative to species from riparian habitats, species from xeric habitats should show a greater degree of acclimation; and (3) plants would respond to water stress by controlling stomatal openness in the shorter term, whereas longer-term acclimation to water stress would involve hydraulic adjustments to reduce water loss while maintaining photosynthesis. We tested these hypotheses in a common glasshouse experiment with three congeneric (Eucalyptus) taxa originating from riparian and xeric habitats. Plants were maintained under either field capacity (FC) or partial drought treatment, and gas exchange was monitored after shorter- and longer-term treatment. After the longer-term treatment, we watered all plants to FC and then withheld water and compared their stomatal, mesophyll and biochemical responses during the ‘drying down’ process. We investigated whether the plants acclimate to the partial drought treatment. We then investigated whether the plants could better tolerate water stress during the drying-down process after the longer-term water stress, and how the contrasting taxa differed in their degree of photosynthetic acclimation to water stress. We also assessed the hydraulic adjustments after the longer-term water stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Choice of plant taxa

Three evergreen taxa were selected from the widely distributed Australian genus Eucalyptus. The selected taxa were E. occidentalis from south-western Australia (seed source: Spa Bundaleer, Western Australia; 33·19°S, 138·33°E), E. camaldulensis subsp. subcinerea from central Australia (seed source: Arthur Creek, Northern Territory; 22·40°S, 136·38°E) and E. camaldulensis subsp. camaldulensis from south-eastern Australia (seed source: Barmah SF, New South Wales; 35·50°S, 145·07°E). Although all three plant taxa occur in warm and dry environments, E. camaldulensis subsp. camaldulensis and E. camaldulensis subsp. subcinerea are considered to be mesic species because they are strongly riparian plant taxa which only occur along rivers. Past studies have reported that E. camaldulensis is a phreatophyte with strong sensitivity to soil moisture content (White et al., 2000; Merchant et al., 2007).

Plant material, growth conditions and experimental design

Seeds of the three Eucalyptus taxa were collected directly from their natural habitats by the Australian Tree Seed Centre at Canberra and were germinated in May 2012 at Macquarie University. At 3 months, the seedlings were transplanted into 90 -L pots containing 80 kg of loamy soil (collected from the Robertson area in New South Wales, Australia), evenly mixed with slow-release fertilizer. The plants were grown in the open air with regular watering and full sunshine for 3 months to allow natural establishment. At 6 months (December 2012), the plants were placed in a glasshouse under a 25°C/18 °C diurnal temperature cycle and maintained in a moist condition (100 % FC). Plants were under the natural photoperiod, and received natural light which was attenuated 40 % by the glasshouse roof. Humidity in the glasshouse was not monitored during this experiment, but previous experiments under similar conditions found an average vapour pressure deficit of 1·3 kPa with no significant differences among glasshouses (J. W. Kelly et al., unpubl. res.). Beginning in February 2013, plants of each taxon were subjected to one of two treatments – full watering (100 % FC) or moderate partial drought (70 % FC). The 70 % FC was used to induce moderate drought, following Atwell et al. (2007) who observed a significant 40 % reduction of leaf and stem growth in Eucalyptus tereticornis when grown at this level of soil moisture availability under similar growth conditions. Three plants of each taxon were randomly assigned to each treatment. Soil water content was maintained based on pot weighting. The soil surface was covered with gravel to minimize water loss. Pots were randomly located in the glasshouse, and randomly relocated twice a week.

Measurements of light-saturated net CO2 assimilation rate (Asat), gs, Vcmax and Jmax were conducted at 2 months of treatment (April 2013). Measurements of these parameters plus steady-state fluorescence and maximum fluorescence were conducted at 4 months of treatment (June 2013). After 4 months, all pots were watered to 100 % FC. Then watering was ceased, and plants were subjected to drying-down until stomatal conductance was close to zero. Daily measurements of pre-dawn leaf water potential, leaf gas exchange, CO2 response curves and chlorophyll fluorescence were conducted throughout the drying-down process. The dry-down process took 18–25 d.

Pre-dawn leaf water potential

Pre-dawn leaf water potential (Ψpd) was adopted as the consistent measure of soil moisture across plants. Ψpd is the best measure of plant water availability because it integrates soil water potential over the root zone (Schulze and Hall, 1982). In particular: (1) Ψpd is not influenced by daytime transpiration, while daytime leaf water potential depends strongly on transpiration as well as soil water status; (2) Ψpd is independent of differences in rooting depth and soil water access; and (3) unlike volumetric soil moisture content, Ψpd is independent of soil texture. Ψpd was measured using a pressure chamber (PMS 1000, PMS Instruments, Corvallis, OR, USA). All measurements were completed before sunrise. Two leaves per sapling were sampled. When the observed difference between the two leaves was >0·2 MPa, a third leaf was measured.

Leaf gas exchange, carbon response curve, chlorophyll fuorescence and mesophyll conductance

Leaf gas exchange measurements were performed on current-year, fully expanded sun-exposed leaves, using a portable photosynthesis system (LI-6400, Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) equipped with an LI-6400-40 Leaf Chamber Fluorometer. Before each measurement, the leaf was acclimated in the chamber for 20–30 min to achieve stable gas exchange, with leaf temperature maintained at 25 °C, reference CO2 concentration at 400 µmol CO2 (mol air)−1, and a saturating photosynthetic photon flux density (Q) of 1800 µmol photons m−2 s−1. Vapour pressure deficit (D) was held as constant as possible during the measurement (D = 1·5 kPa). After the leaf acclimated to the cuvette environment, Asat and gs were measured. Leaf CO2 uptake (A) versus intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) curves were then determined with the cuvette reference CO2 concentration set as follows: 300, 200, 150, 100, 50, 400, 400, 600, 800, 1000, 1400 and 2000 µmol CO2 (mol air)−1. The leaf was allowed to equilibrate for at least 3 min at each Ci step. After completion of these measurements, the light was switched off for 3 min and then leaf respiration rate was measured at the ambient CO2 concentration as the approximation of dark respiration. A and Ci values at each step were corrected for CO2 diffusion leaks with a diffusion correction term (k) of 0·445 µmol m−2 s−1, following the manufacturer’s recommendation (Li-Cor).

At each measurement step, steady-state fluorescence (Fs) and maximum fluorescence () were measured during a light-saturating pulse, allowing calculation of the photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) as ΦPSII = ( − Fs)/. The rate of photosynthetic electron transport from fluorescence (JETR) was then calculated following Krau and Edwards (1992), as JETR = 0·5ΦPSII·α·Q, where 0·5 is a factor accounting for the light distribution between the two photosystems and α is leaf absorptance (assumed to be 0·85–0·88 in the LI-6400 calculations).

Mesophyll conductance was quantified following the variable electron transport rate method of Harley et al. (1992):

| (1) |

where the value of Γ* was taken from Bernacchi et al. (2002), and the rate of non-photorespiratory respiration continuing in the light (Rd) was taken as half the rate of respiration measured in the dark (Niinemets et al., 2005). Thereafter, gm was quantified for every step of the carbon response curves, and then used to calculate the CO2 concentration at the chloroplast (Cc) as follows:

| (2) |

Estimation of , , Vcmax and Jmax

Estimation of , , Vcmax and Jmax (the terms without primes being ‘true’ values, accounting for gm) followed methods described in detail by Zhou et al. (2014). In brief, the values were quantified from CO2 response curves using the leaf photosynthesis model of Farquhar et al. (1980), based on the curve fitting routine was that introduced by Domingues et al. (2010) using the least-squares fitting method in the ‘R’ environment (R Development Core Team, 2010).

Conduit anatomy, Huber values, sapwood-specific and leaf-specific hydraulic conductivity

One current-year branch 25 cm long from the distal apex was collected from each plant for measurements of xylem conduit anatomy. A cross-section at 25 cm from the apex was made by hand, stained with methylene blue and mounted in water for immediate microphotography. The microscope (Olympus BX53, Olympus America Inc.) was interfaced with a digital camera at ×4 magnification to record the whole sapwood area, and at ×20 magnification to record the conduit diameter. Both measurements were made using ImageJ image analysis software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/; ImageJ 1.48; US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MB, USA). Huber values (HVs) were calculated as the ratio between the cross-sectional sapwood area and the leaf area supplied. The hydraulically weighted vessel diameter was calculated for each plant to determine the relative contribution of the conduit to hydraulic conductivity. Calculation of hydraulically weighted diameter and sapwood-specific hydraulic conductivity (KS, kg m−1 s−1 MPa−1) was performed as described by Lewis and Boose (1995). Leaf-specific conductivity (KL) was calculated as the product of KS and HV.

Leaf mass per area, intrinsic water use efficiency, leaf nitrogen content, height and basal diameter

After 4 months of treatment, three current-year fully expanded sun-exposed leaves of each plant were collected, scanned and measured with the ImageJ image analysis software. The leaves were then oven-dried at 60 °C for at least 48 h and weighed to calculate leaf mass per area (LMA, kg m−2). The dried leaf tissue was analysed for stable carbon isotope composition (δ13C, ‰) and nitrogen content on a mass basis (Nmass, %) as described by Mitchell et al. (2008). δ13C provides a time-integrated measure of intrinsic water-use efficiency over the period in which the leaf carbon is assimilated. Nitrogen content on an area basis (Narea, g m−2) was calculated as the product of Nmass and LMA. The height and trunk basal diameter of each plant were also measured.

Stomatal sensitivity to water stress

The g1 parameter (kPa−0·5) was introduced by Medlyn et al. (2011) to represent the stomatal behaviour. Medlyn et al. (2011) showed that a stomatal optimality hypothesis results in a simple theoretical model of very similar form to the widely used empirical stomatal models (Ball et al., 1987; Collatz et al., 1991; Leuning, 1995; Arneth et al., 2002):

| (3) |

where Ca is the atmospheric CO2 concentration at the leaf surface (µmol mol−1) and g0 is the leaf water vapour conductance when photosynthesis is zero (mol H2O m−2 s−1). The derivation of the model by Medlyn et al. (2011) provides an interpretation for g1 as being inversely proportional to the marginal carbon cost of water. An alternative derivation of the same expression and further empirical support were provided by Prentice et al. (2014). The g1 parameter has proved to be a useful, experimentally determined measure of stomatal sensitivity across climates and plant functional types (PFTs) (Héroult et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2013, 2014). Its response to water stress is consistent with the theoretical analysis by Mäkelä et al. (1996) suggesting that the marginal water cost of carbon gain should decline exponentially with decreasing soil moisture availability, and the rate of decline with soil moisture should increase with the probability of rain (Zhou et al., 2013, 2014).

We estimated g1 for each pre-dawn leaf water potential from measurements of A, gs, Ca and D by re-arranging eqn (3). The parameter g0 is not part of the optimization and was assigned the value 0·001 mol m−2 s−1.

Analytical model for the function of stomatal, mesophyll and biochemical responses during the drying-down process

We used equations introduced by Zhou et al. (2013, 2014) to analyse the response functions of g1, gm, and to Ψpd during the drying-down process. An exponential decrease of g1 and gm with declining Ψpd was fitted to each set of observations:

| (4) |

| (5) |

where g1*, b1, gm* and b2 are fitted parameters: g1* is the g1 value at Ψpd = −0·3 MPa, and b1 represents the sensitivity of g1 to Ψpd. gm* is the gm value at Ψpd = −0·3 MPa, and b2 represents the sensitivity of gm to Ψpd. Species adopting different water use strategies are expected to differ in their g1 sensitivity (b1) and gm sensitivity (b2) to water stress. The responses of and were quantified using the logistic function (Tuzet et al., 2003):

| (6) |

We also quantified all parameters defining the drought response of Vcmax. The function ƒ(ΨPD) accounts for the relative effect of water stress on Vcmax, and . The form of this function allows a relatively flat response of Vcmax, and under moist conditions, followed by a steep decline, with a flattening again (towards zero) under the driest conditions. K is the value of ƒ(Ψpd) under moist conditions. Sf is a sensitivity parameter indicating the steepness of the decline, while Ψf is a reference value indicating the water potential at which K decreases to half of its maximum value. Species adopting different water use strategies might be expected to differ in the sensitivity of Vcmax, and to water stress (SfV, SfV′, and SfJ′) and reference water potential (ΨfV, ΨfV′ and ΨfJ′).

Statistical analyses

The analysis of variance package anova() in R was used to assess treatment effects, and interactions between species and treatment and between treatment and duration. The non-linear least-squares package nls() in R was used to find initial values (least-squares estimates) of the parameters of the exponential functions for responses of g1 and gm (g1*, b1, gm* and b2); the alternative non-linear least-squares package nls2() was used to find initial values of the parameters of the logistic functions for responses of Vcmax, and (Vcmax*, *, *, SfV, SfV′, SfJ′, ΨfV, ΨfV′ and ΨfJ′). These initial values were then input into the maximum-likelihood estimation package bblme() in R to yield best estimates and standard errors for each parameter. The package glht() was used to conduct multi-comparison analysis on response curves of each parameter across the three contrasting Eucalyptus taxa in the drying-down process after 4 months of treatments. Principal components analysis (PCA) was conducted on the best estimates of parameters to investigate the correlations among the key traits defining the longer-term drought responses of g1, gm, and of three contrasting taxa.

RESULTS

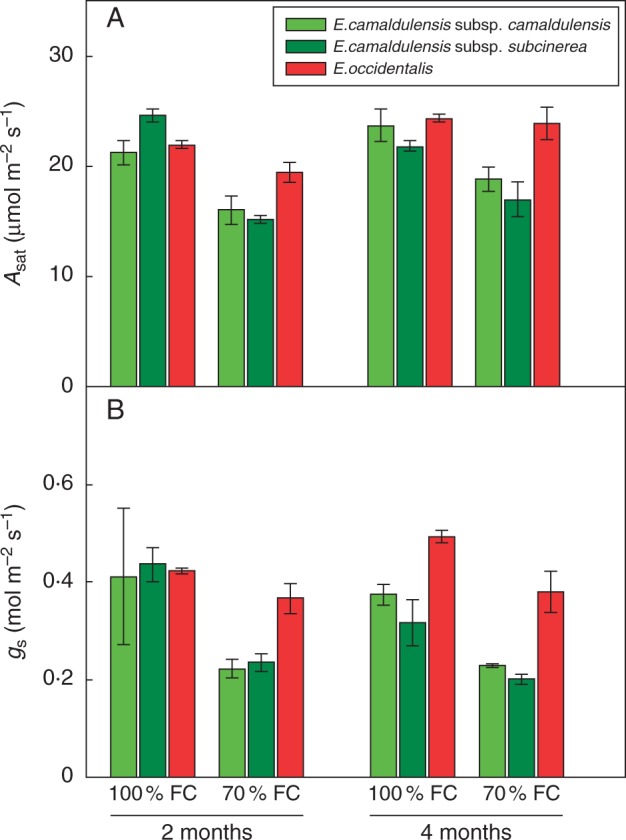

Effect of partial drought on Asat, gs, g1, and after 2 and 4 months

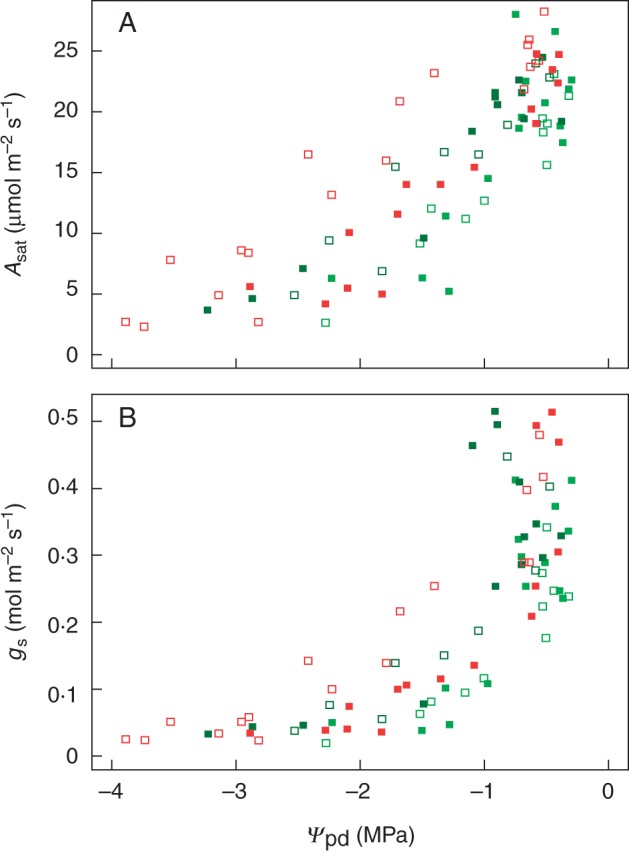

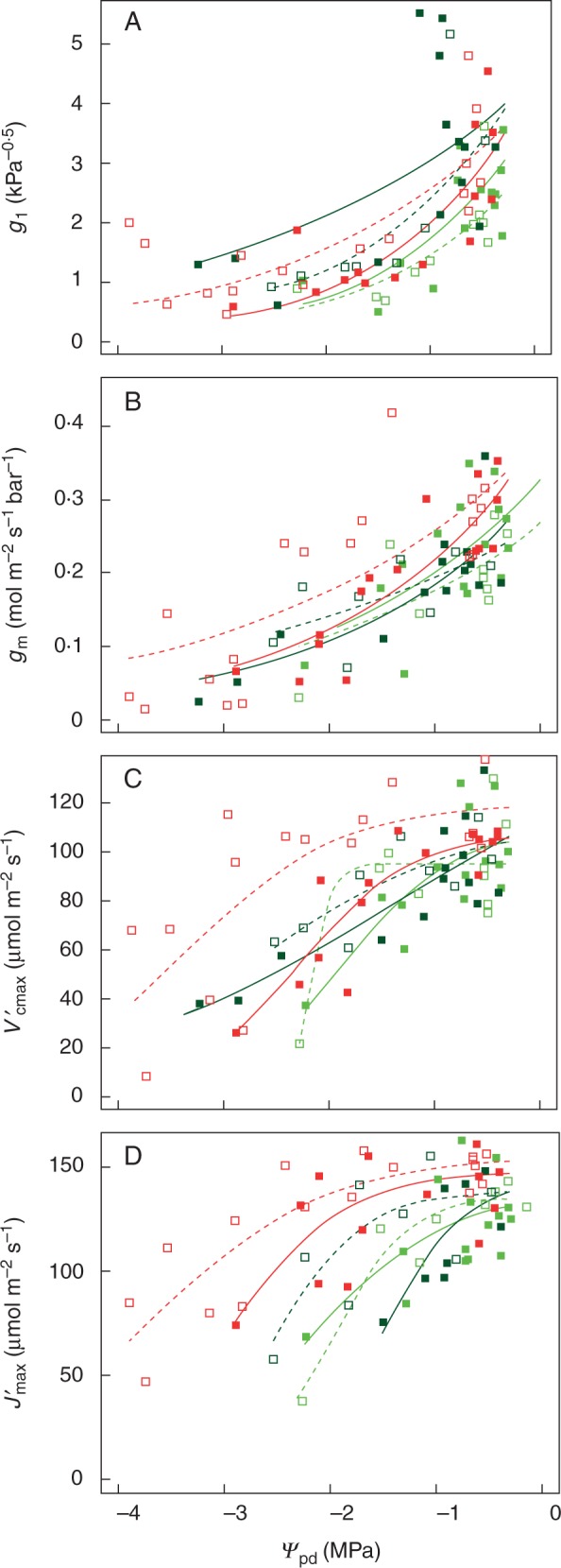

The partial drought consistently reduced the light-saturated CO2 assimilation rate (Asat) after 2 months (P < 0·001) and 4 months (P < 0·01). There was a significant interaction between species and treatment (P < 0·01; Table 1), indicating that partial drought had a greater impact on photosynthesis in the riparian E. camaldulensis than the xeric E. occidentalis (Fig. 1A). There was also a significant interaction between treatment and time (P < 0·05; Table 1), indicating that in both riparian and xeric species, the effect of water stress on photosynthesis recovered over time. Compared with E. camaldulensis subsp. camaldulensis and E. camaldulensis subsp. subcinerea, E. occidentalis from the xeric habitat showed the smallest decline in Asat after 2 months (Fig. 1A). In E. occidentalis, Asat recovered completely after 4 months, such that there was no difference in Asat between the droughted and well-watered plants (Fig. 1A). The partial drought significantly reduced gs in all taxa after 2 months (P < 0·01) and 4 months (P < 0·001) (Fig. 1B), and reduced g1 after 4 months (P < 0·01) (Fig. 2A).

Table 1.

P-values of comparison across three Eucalyptus taxa exposed to two watering treatments (100 % versus 70 % FC) on components of leaf gas exchange (leaf net photosynthesis at saturating light Asat; stomatal conductance gs; stomatal sensitivity parameter g1; apparent Rubisco activity ; apparent maximum electron transport rate ; ratio of to ) measured after 2 and 4 months of treatment, and on hydraulic traits, growth status and leaf nitrogen content (carbon-isotope composition δ13C; leaf-specific conductivity KL; sapwood-specific conductivity KS; Huber value HV; height; basal diameter; leaf mass per area LMA; leaf nitrogen content on an area basis Narea) measured after 4 months of treatment

| Asat | gs | g1 | / | δ13C | KL | KS | HV | Height | Basal diameter | LMA | Narea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | 0·001 | <0·001 | 0·029 | 0·37 | 0·05 | 0·13 | 0·69 | 0·001 | 0·001 | 0·007 | 0·49 | 0·32 | 0·01 | 0·32 |

| Treatment | <0·001 | <0·001 | 0·01 | <0·001 | 0·002 | 0·11 | 0·02 | 0·004 | 0·91 | <0·001 | 0·093 | <0·001 | 0·12 | 0·98 |

| Time | 0·004 | 0·59 | 0·074 | 0·022 | 0·013 | <0·001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Species × Treatment | 0·002 | 0·16 | 0·86 | 0·049 | 0·28 | 0·23 | 0·81 | 0·18 | 0·67 | 0·27 | 0·88 | 0·94 | 0·95 | 0·96 |

| Species × Time | 0·084 | 0·15 | 0·59 | 0·70 | 0·94 | 0·74 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment × Time | 0·045 | 0·84 | 0·40 | 0·043 | 0·48 | 0·034 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Species × Treatment × Time | 0·50 | 0·70 | 0·86 | 0·80 | 0·52 | 0·78 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Data are shown in Figs 1–3 (means ± s.e.; n = 3). NA, not applicable.

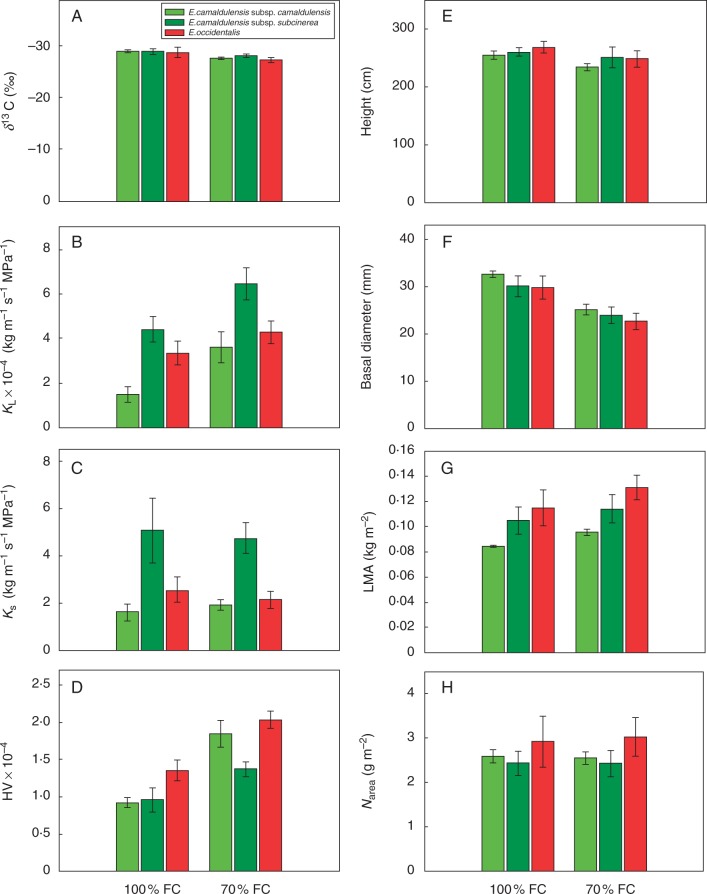

Fig. 1.

(A) Leaf net photosynthesis at saturating light (Asat) and (B) stomatal conductance (gs) of three Eucalyptus taxa exposed to watering treatments of 100 % field capacity (FC) (Ψpd = –0·3 ± 0·1 MPa) and 70 % FC (Ψpd = –0·5 ± 0·1 MPa), measured after 2 and 4 months of treatment. Values are means ± s.e. (n = 3).

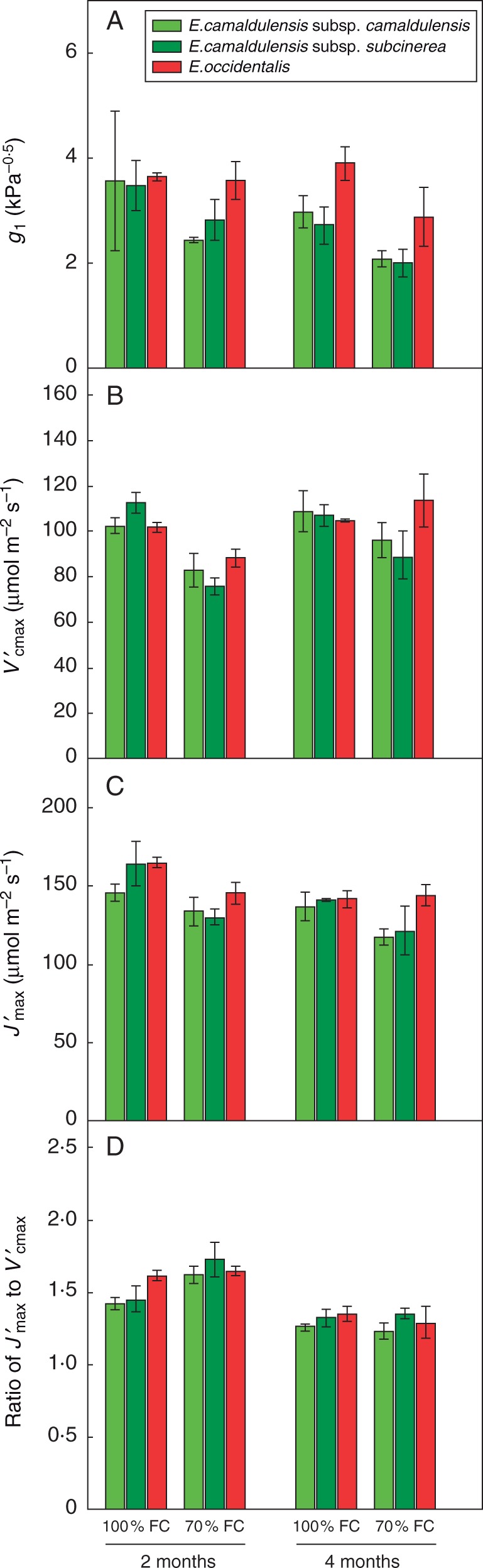

Fig. 2.

Components of leaf gas exchange in three Eucalyptus taxa exposed to watering treatments of 100 % FC (Ψpd = –0·3 ± 0·1 MPa) and 70 % FC (Ψpd = –0·5 ± 0·1 MPa), after 2 and 4 months of treatment. (A) Stomatal sensitivity parameter g1; (B) apparent Rubisco activity ; (C) apparent maximum electron transport rate ; (D) ratio of to . Values are means ± s.e. (n = 3).

was significantly reduced by the partial drought after 2 months (P < 0·001) but not after 4 months. There were significant interactions between species and treatment (P < 0·05; Table 1) and between treatment and time (P < 0·05; Table 1) (Fig. 2B). Compared with the two riparian taxa, E. occidentalis showed the smallest decline in after 2 months, and the recovered after 4 months (Fig. 2B). The partial drought significantly reduced (P < 0·01) and increased the ratio between and (P < 0·05) after 2 months, while there was no significant reduction after 4 months (Fig. 2C, D).

Effect of partial drought on δ13C, KL, KS, HV, height, basal diameter, LMA and Narea after 4 months

Compared with plants of the three taxa kept under 100 % FC (Ψpd = –0·3 ± 0·1 MPa) for 4 months, plants kept under 70 % FC (Ψpd = –0·5 ± 0·1 MPa) showed less negative δ13C (P < 0·05) (Fig. 3A; Table 1), larger KL (P < 0·01) (Fig. 3B; Table 1), larger HV (P < 0·001) (Fig. 3D; Table 1), lower height (marginally significant, P < 0·1) (Fig. 3E; Table 1) and lower basal diameter (P < 0·001) (Fig. 3F; Table 1). There was no effect of treatment on KS (Fig. 3C; Table 1), LMA (Fig. 3G; Table 1), Nweight and Narea (Fig. 3H; Table 1) or hydraulically weighted vessel diameter (Supplementary Data Fig. S1). These long-term responses to partial drought did not differ significantly among species.

Fig. 3.

Hydraulic traits, growth status and leaf nitrogen content of three Eucalyptus taxa exposed to watering treatments of 100 % FC (Ψpd = –0·3 ± 0·1 MPa) and 70 % FC (Ψpd = –0·5 ± 0·1 MPa), measured after 4 months of treatment. (A) Carbon-isotope composition δ13C; (B) leaf-specific conductivity KL; (C) sapwood-specific conductivity KS; (D) Huber value (sapwood area per unit leaf area); (E) height; (F) basal diameter; (G) leaf mass per area; (H) leaf nitrogen content on an area basis. Values are means ± s.e. (n = 3).

Response of g1, gm, and in the drying-down process after 4 months

In the drying-down process after 4 months of treatments, all plants showed considerable decline of Asat, gs, g1, gm, and as water availability declined (Figs 4 and 5). There was no effect of growth treatment (100 % FC vs. 70 % FC) on the response of g1, gm and to declining ΨPD (Fig. 5A, B, D; Table 2). There was a significant effect of growth treatment on the response curve of to declining ΨPD in xeric E. occidentalis but not in either subspecies of riparian E. camaldulensis (Fig. 5C; Table 2). Compared with plants under 100 % FC, E. occidentalis plants from the 70 % FC treatment had significantly more negative ΨfV′ (the water potential at which decreases to half of its maximum value) (P < 0·01; Table 2). Similarly, there was a difference between these contrasting taxa when comparing the effect of growth treatment on the response curve of Vcmax, which was consistent with the contrasting responses of (Supplementary Data Fig. S2; Table 2). Eucalyptus occidentalis plants from 70 % FC had more negative ΨfV (marginally significant, P = 0·07) than plants from 100 % FC (Table 2). Estimated parameter values for each Eucalyptus taxon from each treatment are given in Table 2.

Fig. 4.

(A) Light-saturated CO2 assimilation rate (Asat) and (B) stomatal conductance as a function of pre-dawn leaf water potential during a drying cycle following 4 months of treatment at 100 % FC (solid squares) or 70 % FC (open squares). Dark green: E. camaldulensis subsp. camaldulensis; light green: E. camaldulensis subsp. subcinerea; red: E. occidentalis.

Fig. 5.

Components of leaf gas exchange as a function of pre-dawn leaf water potential during a drying cycle following 4 months of treatment at 100 % FC (solid squares for raw data; solid lines for fitted curves) or 70 % FC (open squares for raw data; solid lines for fitted curves). (A) Stomatal sensitivity parameter g1; (M) mesophyll conductance gm; (C) apparent Rubisco activity ; (D) apparent maximum electron transport rate . Dark green: E. camaldulensis subsp. camaldulensis; light green: E. camaldulensis subsp. subcinerea; red: E. occidentalis.

Table 2.

Fitted values of 13 traits defining the drought responses of stomatal and non-stomatal components of three Eucalyptus taxa during the drying-down process after 4 months of treatment

| Species and treatment | g1* | b1 | * | SfV′ | ΨfV′ | gm* | b2 | Vcmax* | SfV | ΨfV | * | SfJ′ | ΨfJ′ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 % FC | |||||||||||||

| E. occidentalis | 3·68 | 0·97 | 107 | 1·82 | −2·28 | 0·32 | 0·55 | 134 | 1·94 | −2·69 | 148 | 1·83 | −2·92 |

| E. camaldulensis subsp. subcinerea | 3·54 | 0·31 | 113 | 0·65 | −1·28 | 0·26 | 0·51 | 126 | 0·63 | −2·16 | 142 | 2·61 | −1·48 |

| E. camaldulensis subsp. camaldulensis | 3·04 | 0·84 | 106 | 1·9 | −1·85 | 0·28 | 0·5 | 127 | 2·71 | −1·93 | 134 | 1·57 | −2·15 |

| 70 % FC | |||||||||||||

| E. occidentalis | 3·57 | 0·48 | 118 | 1·42 | −3·35 | 0·34 | 0·39 | 142 | 2·46 | −3·46 | 154 | 1·21 | −3·67 |

| E. camaldulensis subsp. subcinerea | 3·89 | 0·69 | 107 | 1·01 | −2·66 | 0·24 | 0·32 | 138 | 2·46 | −2·43 | 138 | 2·45 | −2·49 |

| E. camaldulensis subsp. camaldulensis | 2·52 | 0·78 | 94·8 | 10·3 | −2·16 | 0·24 | 0·43 | 125 | 9·97 | −2·14 | 136 | 2·79 | −1·97 |

The 13 traits are: g1* and b1 (eqn 4), gm* and b2 (eqn 5), * ( estimated at Ψpd = 0), SfV′ (sensitivity of ), ΨfV′, Vcmax* (Vcmax estimated at Ψpd = 0), SfV (sensitivity of Vcmax), ΨfV, * ( estimated at Ψpd = 0), SfJ′ (sensitivity of ), ΨfJ′ (eqn 6). Fitted functional relationships are shown in Fig. 5.

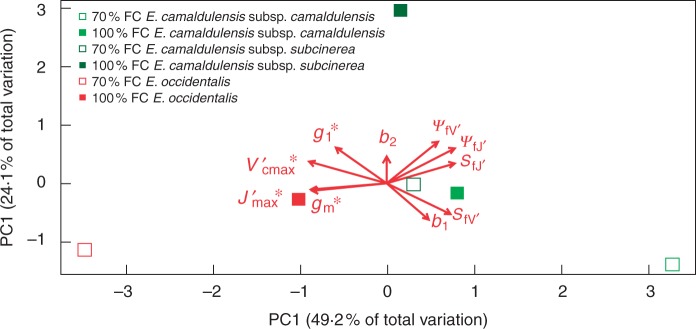

Water relation strategies

PCA (Fig. 6) showed strong dominance by the first principal component (PC1), which explained 49·2 % of the total variation. PC1 showed a continuum from the most xeric Eucalyptus taxon (E. occidentalis towards the left) to the most mesic taxon (E. camaldulensis subsp. camaldulensis towards the right), characterized by the positive correlation among b1, SfV′, SfJ′, ΨfV′ and ΨfJ′, and by their negative correlations with g1*, gm*, Vcmax*′ and Jmax*′ (Fig. 6). Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. camaldulensis, found to the right of PC1, was characterized by (1) lower initial g1, gm, and values under moist conditions; (2) a relatively higher rate of decline in g1, and in the drying-down process; and (3) the decrease of and commencing at a more negative pre-dawn leaf water potential (Fig. 6; Table 2).

Fig. 6.

Principal components analysis of ten drought-response traits, b1 (sensitivity of g1) and g1* (eqn 4), b2 (sensitivity of gm) and gm* (eqn 5), * ( estimated at Ψpd = 0), SfV′, ΨfV′, * ( estimated at Ψpd = 0), SfJ′ and ΨfJ′ (eqn 6).The first principal component (PC1) showed a continuum of species from more mesic to more xeric, which explained 49·2 % of the total variation. The second principal component (PC2) showed a continuum of plants from 70 to 100 % FC treatment, which explained 24·1 % of the total variation. Trait values are shown in Table 2.

The second principal component (PC2) explained 24·1 % of the total variation. Along PC2, the plants were arranged into two loose groups along another continuum from the Eucalyptus taxa kept under 70 % FC for 4 months (towards the bottom) to the Eucalyptus taxa kept under 100 % FC (towards the top), characterized by the positive correlation with b2. The Eucalyptus taxa kept under 70 % FC for 4 months were characterized by a lower rate of decline of gm in the drying-down process. PC1 and PC2 suggested a direction of acclimation from plants kept under 100 % FC to that of 70 % FC in long-term water stress. Compared with plants kept under 100 % FC, plants kept under 70 % FC for 4 months tended to have lower values of b2 and ΨfV′. Parameter values of the three Eucalyptus taxa from the two treatments are shown in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

We investigated whether plant photosynthetic rates and their response to soil moisture stress could acclimate to longer-term low soil moisture availability. This study provides important experimental evidence that the photosynthetic acclimation can occur in longer-term water stress, and highlights the significant acclimation of in xeric but not riparian Eucalyptus taxa.

Differential acclimation of photosynthetic responses in contrasting Eucalyptus taxa to long-term water stress

After 2 months of 70 % FC treatment, we observed a significant reduction in Asat, gs, and in all taxa (Figs 1 and 2). However, the effect of partial drought on photosynthesis differed among species, such that E. occidentalis from xeric habitat showed less stomatal and biochemical limitations than the riparian E. camaldulensis at 2 months.

Meanwhile, the effect of partial drought differed at the different time points, being smaller at 4 months than at 2 months. Four months of 70 % FC treatment allowed for acclimation of and such that the biochemical limitations found in short-term water stress in all taxa are mitigated (Fig. 2). However, E. occidentalis showed more recovery of and than E. camaldulensis after 4 months of water stress (Fig. 2).

In the subsequent drying-down process, all plants consistently showed a progressive increase in stomatal, mesophyll and biochemical limitation with increasing water stress (Figs 4 and 5; Table 2), which is consistent with previous studies in which a drying-down process was imposed without the longer-term water stress (Zhou et al., 2013, 2014). The response functions of g1, gm, and to declining ΨPD were compared between plants from 70 and 100 % FC using a multi-comparison analysis. We investigated two possible classes of causes accounting for mitigation of limitation on in longer-term water stress: (1) mitigation of limitation on gm as reported by Galle et al. (2009) and Cano et al. (2014); and (2) mitigation of limitation on Vcmax, which has never been reported before according to our knowledge. The results showed the three contrasting Eucalyptus taxa differed notably in their degree of modification of the functional relationship of (and Vcmax) with declining ΨPD (Fig. 5; Table 2). When comparing the plants kept under 70 and 100 % FC, E. occidentalis showed a significantly higher degree of (and Vcmax) acclimation than the two riparian taxa in the longer-term water stress, by significantly displacing the start of severe limitations on (and Vcmax) to lower ΨfV′ (and ΨfV) (Fig. 5; Table 2). E. occidentalis plants kept under 70 % FC for 4 months – during which the significant acclimation process occurred – showed the ability to continue active photosynthesis down to much lower soil water potential (−3·9 MPa) than plants of the two riparian taxa kept under 70 % FC for four months (Figs 4 and 5).

For the first time, we report significant acclimation of drought sensitivity of Vcmax in xeric but not riparian Eucalyptus (Figs 2 and 5; Supplementary Data Fig. S2; Table 2). This study adds novel information to previous studies investigating whether plants acclimate to long-term water stress by modifying the functional relationships between photosynthetic traits and water stress (Limousin et al., 2010b; Misson et al., 2010; Martin-StPaul et al., 2012). After long-term water stress during which the acclimation process occurred, the xeric but not riparian Eucalyptus taxa could significantly modify the functional relationship between Rubisco activity and declined ΨPD. The inherent differences among the three Eucalyptus taxa of contrasting habitat were not only reflected in their contrasting degree of tolerance in short-term water stress, but also in their contrasting degree of acclimation in long-term water stress. These differences supported our original hypothesis, namely that xeric species would show stronger acclimation to water stress, and probably reflect stronger evolutionary pressures for drought tolerance in dry habitats.

Short-term water stress could lead to the decrease of Rubisco activity, associated with down-regulation of the activation state of the enzyme (Galmés et al., 2013), reduction in Rubisco content and/or soluble protein content (Hanson and Hitz, 1982; Wilson et al., 2000; Xu and Baldocchi, 2003; Grassi et al., 2005; Misson et al., 2006). However, the longer-term water stress might lead to significantly higher protein content and/or protein allocated to Rubisco in leaves of the drought-tolerant taxa than drought-sensitive taxa (Tezara and Lawlor, 1995; Panković et al., 1999), indicating that higher Rubisco content could be one factor in conferring higher drought tolerance and acclimation in xeric species than mesic species. In this study, there was no difference in leaf Nmass or Narea between plants from the two treatments (Fig. 3), but we were unable to further test if the plants kept under 70 % FC had higher nitrogen allocation to Rubisco than that of plants kept under 100 % FC.

We did not find significantly higher gm in xeric species than mesic species after longer-term water stress as reported by Cano et al. (2014). Species-specific physiology may be of particular importance in comparing their responses to longer-term water stress, leading to varied findings among studies investigating the comparative acclimation in contrasting species (Ogaya and Peñuelas, 2003; Cano et al., 2014). Note that the drought stress treatments applied here differed considerably from those used by Cano et al. (2014). Our low-water treatment was 70 % FC for all taxa, whereas Cano et al. (2014) defined their low-water treatment by stomatal conductance <0·05 mol m−2 s−1, leading to a lower soil moisture potential in the xeric than the mesic species. Differences in the depth and severity of drought applied, as well as age of plant material, may account for different findings across drought experiments. The current experiment, at 4 months, is shorter than many field-based drought manipulations; however, acclimation is likely to occur more rapidly in seedlings and saplings than in the mature trees typically used in field studies (e.g. Limousin et al., 2010b, 2013). For example, a drought pre-conditioning period of 32 d was sufficient to increase drought survival of Eucalyptus globulus seedlings (Guarnaschelli et al., 2006). It remains to be shown whether the same patterns found in the present study occur in mature Eucalyptus trees in the field, and also for contrasting species of other genera and/or in other biomes.

Hydraulic adjustments after the longer-term water stress

Without sufficient control of water loss during severe drought, xylem embolism and damage could occur and lead to hydraulic failure. However, maintaining water potentials through stomatal closure during severe drought reduces photosynthesis, potentially leading to carbon starvation and mortality (Sala et al., 2012; Adams et al., 2013). Hydraulic down-regulation has been reported to link to drought acclimation of leaf gas exchange in long-term precipitation manipulation experiments (e.g. Limousin et al., 2013; Martin-StPaul et al., 2013). Our results showed an adjustment of hydraulic properties in plants exposed to 4 months of 70 % FC treatment (Figs 2, 3 and 6; Table 2), which would reduce the vulnerability of xylem to cavitation while maintaining photosynthesis during longer-term water stress. The plants kept under 70 % FC for 4 months had stopped growth in height and basal diameter, and significantly increased their sapwood area invested per unit leaf area, yielding higher leaf-specific conductivity. Meanwhile, the plants kept under 70 % FC for 4 months had lower δ13C, b2, ΨfV′ and ΨfJ′ when compared with plants kept under 100 % FC (Fig. 6; Table 2). This combination of trait changes allowed them to increase the intrinsic water use efficiency, decrease gm, and slowly to maintain more CO2 supply to the chloroplasts, and also maintain higher photosynthetic capacity and RuBP regeneration capacity down to lower water potential. Prentice et al. (2014) predicted that HV and are necessarily linked, which supported our results on the acclimation of carboxylation capacity and the larger HVs in plants kept under 70 % FC for 4 months.

We conclude that the photosynthetic drought responses of plants in the long term can be different from those observed in short-term experiments. For plant physiologists and modellers, this study highlights the importance of considering the acclimation process and its variation with the habitat of species when predicting the long-term drought effect. The findings on intra- and inter-species variation of photosynthetic acclimation in long-term drought could also help restoration ecologists on the selection of species for restoration schemes aiming to increase long-term drought resistance and resilience of forest ecosystems.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org. and consist of the following. Figure S1: hydraulically weighted vessel diameter of three taxa at 100 and 70 % FC treatments after 4 months. Figure S2: Rubisco activity Vcmax as a function of pre-dawn leaf water potential during a drying cycle following 4 months of treatment at 100 or 70 % FC.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the help of Associate Prof. Brian Atwell and Srikanta Dani Kaidala-Ganesha with plant materials and soil preparation, glasshouse maintenance and watering. We acknowledge Dr Drew Allen for help on R and statistics. S.-X.Z. was supported by an international Macquarie University Research Excellence Scholarship. This work was supported by ARC Discovery Grant DP120104055.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adams HD, Germino MJ, Breshears DD, et al. 2013. Nonstructural leaf carbohydrate dynamics of Pinus edulis during drought-induced tree mortality reveal role for carbon metabolism in mortality mechanism. New Phytologist 197: 1142–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arneth A, Lloyd J, Santruckova H, et al. 2002. Response of central Siberian Scots pine to soil water deficit and long-term trends in atmospheric CO2 concentration. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 16: 5–1–5-13. [Google Scholar]

- Atwell BJ, Henery ML, Rogers GS, Seneweera SP, Treadwell M, Conroy JP. 2007. Canopy development and hydraulic function in Eucalyptus tereticornis grown in drought in CO2-enriched atmospheres. Functional Plant Biology 34: 1137–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball JT, Woodrow IE, Berry JA. 1987. A model predicting stomatal conductance and its contribution to the control of photosynthesis under different environmental conditions. In: Biggins J, ed. Progress in photosynthesis research. Dordrecht: Martinus-Nijhoff Publishers, 221–224. [Google Scholar]

- Bernacchi CJ, Portis AR, Nakano H, von Caemmerer S, Long SP. 2002. Temperature response of mesophyll conductance. Implications for the determination of Rubisco enzyme kinetics and for limitations to photosynthesis in vivo. Plant Physiology 130: 1992–1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bota J, Medrano H, Flexas J. 2004. Is photosynthesis limited by decreased Rubisco activity and RuBP content under progressive water stress? New Phytologist 162: 671–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano FJ, López R, Warren CR. 2014. Implications of the mesophyll conductance to CO2 for photosynthesis and water-use efficiency during long-term water stress and recovery in two contrasting Eucalyptus species. Plant Cell and Environment 37: 2470–2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrillo M, Fernandez D, Calcagno A. 2001. Responses of ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate carboxylase, protein content, and stomatal conductance to water deficit in maize, tomato, and bean. Photosynthetica 39: 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Choat B, Jansen S, Brodribb TJ, et al. 2012. Global convergence in the vulnerability of forests to drought. Nature 491: 752–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collatz GJ, Ball JT, Grivet C, Berry JA. 1991. Physiological and environmental regulation of stomatal conductance, photosynthesis and transpiration: a model that includes a laminar boundary layer. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 54: 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Domingues TF, Meir P, Feldpausch TR, et al. 2010. Co-limitation of photosynthetic capacity by nitrogen and phosphorus in West Africa woodlands. Plant Cell and Environment 33: 959–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egea G, Verhoef A, Vidale PL. 2011. Towards an improved and more flexible representation of water stress in coupled photosynthesis–stomatal conductance models. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 151: 1370–1384. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA. 1980. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149: 78–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Bota J, Loreto F, Cornic G, Sharkey TD. 2004. Diffusive and metabolic limitations to photosynthesis under drought and salinity in C3 plants. Plant Biology 6: 269–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Ribas-Carbó M, Bota J, et al. 2006. Decreased Rubisco activity during water stress is not induced by decreased relative water content but related to conditions of low stomatal conductance and chloroplast CO2 concentration. New Phytologist 172: 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Barbour MM, Brendel O, et al. 2012. Mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2: an unappreciated central player in photosynthesis. Plant Science 193-194: 70–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galle A, Florez-Sarasa I, Tomas M, et al. 2009. The role of mesophyll conductance during water stress and recovery in tobacco (Nicotiana sylvestris): acclimation or limitation? Journal of Experimental Botany 60: 2379–2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Aranjuelo I, Medrano H, Flexas J. 2013. Variation in Rubisco content and activity under variable climatic factors. Photosynthesis Research 117: 73–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi G, Magnani F. 2005. Stomatal, mesophyll conductance and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis as affected by drought and leaf ontogeny in ash and oak trees. Plant Cell and Environment 28: 834–849. [Google Scholar]

- Grassi G, Vicinelli E, Ponti F, Cantoni L, Magnani F. 2005. Seasonal and interannual variability of photosynthetic capacity in relation to leaf nitrogen in a deciduous forest plantation in northern Italy. Tree Physiology 25: 349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaschelli AB, Prystupa P, Lemcoff JH. 2006. Drought conditioning improves water status, stomatal conductance and survival of Eucalyptus globulus subsp. bicostata seedlings. Annals of Forest Science 63: 941–950. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson AD, Hitz WD. 1982. Metabolic responses of mesophytes to plant water deficits. Annual Review of Plant Physiology 33: 163–203. [Google Scholar]

- Harley PC, Loreto F, Di Marco G, Sharkey TD. 1992. Theoretical considerations when estimating the mesophyll conductance to CO2 flux by analysis of the response of photosynthesis to CO2. Plant Physiology 98: 1429–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Héroult A, Lin Y-S, Bourne A, Medlyn BE, Ellsworth DS. 2013. Optimal stomatal conductance in relation to photosynthesis in climatically contrasting Eucalyptus species under drought. Plant Cell and Environment 36: 262–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. 2014. In Stocker TF, et al., eds. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kanechi M, Uchida N, Yasuda T, Yamaguchi T. 1996. Non-stomatal inhibition associated with inactivation of rubisco in dehydrated coffee leaves under unshaded and shaded conditions. Plant Cell Physiology 37: 455–460. [Google Scholar]

- Krau JP, Edwards GE. 1992. Relationship between photosystem II activity and CO2 fixation in leaves. Physiologia Plantarum 86: 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Leuning R. 1995. A critical appraisal of a combined stomatal-photosynthesis model for C3 plants. Plant Cell and Environment 18: 339–355. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AM, Boose ER. 1995. Estimating volume flow rates through xylem conduits. American Journal of Botany 82: 1112–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Limousin JM, Longepierre D, Huc R, Rambal S. 2010a. Change in hydraulic traits of Mediterranean Quercus ilex subjected to long-term throughfall exclusion. Tree Physiology 30: 1026–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limousin JM, Misson L, Lavoir AV, Martin NK, Rambal S. 2010b. Do photosynthetic limitations of evergreen Quercus ilex leaves change with long-term increased drought severity? Plant Cell and Environment 33: 863–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limousin JM, Bickford CP, Dickman LT, et al. 2013. Regulation and acclimation of leaf gas exchange in a piñon–juniper woodland exposed to three different precipitation regimes. Plant Cell and Environment 36: 1812–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä A, Berninger F, Hari P. 1996. Optimal control of gas exchange during drought: theoretical analysis. Annals of Botany 77: 461–467. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-StPaul NK, Limousin JM, Rodríguez-Calcerrada J, et al. 2012. Photosynthetic sensitivity to drought varies among populations of Quercus ilex along a rainfall gradient. Functional Plant Biology 39: 25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-StPaul NK, Limousin JM, Vogt-Schilb H, et al. 2013. The temporal response to drought in a Mediterranean evergreen tree: comparing a regional precipitation gradient and a throughfall exclusion experiment. Global Change Biology 19: 2413–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maseda PH, Fernández RJ. 2006. Stay wet or else: three ways in which plants can adjust hydraulically to their environment. Journal of Experimental Botany 57: 3963–3977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medlyn BE, Duursma RA, Eamus D, et al. 2011. Reconciling the optimal and empirical approaches to modelling stomatal conductance. Global Change Biology 17: 2134–2144. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant A, Callister A, Arndt S, Tausz M, Adams M. 2007. Contrasting physiological responses of six Eucalyptus species to water deficit. Annals of Botany 100: 1507–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misson L, Tu KP, Boniello RA, Goldstein AH. 2006. Seasonality of photosynthetic parameters in a multi-specific and vertically complex forest ecosystem in the Sierra Nevada of California. Tree Physiology 26: 729–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misson L, Limousin JM, Rodriguez R, Letts MG. 2010. Leaf physiological responses to extreme droughts in Mediterranean Quercus ilex forest. Plant Cell and Environment 33: 1898–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PJ, Veneklaas EJ, Lambers H, Burgess SS. 2008. Using multiple trait associations to define hydraulic functional types in plant communities of south-western Australia. Oecologia 158: 385–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets ÜLO, Cescatti A, Rodeghiero M, Tosens T. 2005. Leaf internal diffusion conductance limits photosynthesis more strongly in older leaves of Mediterranean evergreen broad-leaved species. Plant Cell and Environment 28: 1552–1566. [Google Scholar]

- Nogués S, Alegre L. 2002. An increase in water deficit has no impact on the photosynthetic capacity of field-grown Mediterranean plants. Functional Plant Biology 29: 621–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogaya R, Peñuelas J. 2003. Comparative field study of Quercus ilex and Phillyrea latifolia: photosynthetic response to experimental drought conditions. Environmental and Experimental Botany 50: 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ogle K, Barber JJ, Barron-Gafford GA, et al. 2015. Quantifying ecological memory in plant and ecosystem processes. Ecology Letters 18: 221–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panković D, Sakač Z, Kevrešan S, Plesničar M. 1999. Acclimation to long-term water deficit in the leaves of two sunflower hybrids: photosynthesis, electron transport and carbon metabolism. Journal of Experimental Botany 50: 128–138. [Google Scholar]

- Parry MA, Andralojc PJ, Khan S, Lea PJ, Keys AJ. 2002. Rubisco activity: effects of drought stress. Annals of Botany 89: 833–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice IC, Dong N, Gleason SM, Maire V, Wright IJ. 2014. Balancing the costs of carbon gain and water transport: testing a new theoretical framework for plant functional ecology. Ecology Letters 17: 82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. . 2010. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Calcerrada J, Jaeger C, Limousin JM, Ourcival JM, Joffre R, Rambal S. 2011. Leaf CO2 efflux is attenuated by acclimation of respiration to heat and drought in a Mediterranean tree. Functional Ecology 25: 983–995. [Google Scholar]

- Sala A, Woodruff DR, Meinzer FC. 2012. Carbon dynamics in trees: feast or famine? Tree Physiology 32: 764–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze ED, Hall AE. 1982. Stomatal responses, water loss and CO2 assimilation rates of plants in contrasting environments. In: Lange OL, Nobel PS, Osmond CB, Ziegler H, eds. Physiological plant ecology. II. Water relations and carbon assimilation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 181–230. [Google Scholar]

- Tezara W. 2002. Effects of water deficit and its interaction with CO2 supply on the biochemistry and physiology of photosynthesis in sunflower. Journal of Experimental Botany 53: 1781–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tezara W, Lawlor DW. 1995. Effects of water stress on the biochemistry and physiology of photosynthesis in sunflower. Photosynthesis: from Light to Biosphere 4: 625–628. [Google Scholar]

- Tezara W, Mitchell VJ, Driscoll SD, Lawlor DW. 1999. Water stress inhibits plant photosynthesis by decreasing coupling factor and ATP. Nature 401: 914–917. [Google Scholar]

- Thimmanaik S, Kumar SG, Kumari GJ, Suryanarayana N, Sudhakar C. 2002. Photosynthesis and the enzymes of photosynthetic carbon reduction cycle in mulberry during water stress and recovery. Photosynthetica 40: 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Tuzet A, Perrier A, Leuning R. 2003. A coupled model of stomatal conductance, photosynthesis and transpiration. Plant, Cell and Environment 26: 1097–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef A, Egea G. 2014. Modeling plant transpiration under limited soil water: comparison of different plant and soil hydraulic parameterizations and preliminary implications for their use in land surface models. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 191: 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- White DA, Turner NC, Galbraith JH. 2000. Leaf water relations and stomatal behavior of four allopatric Eucalyptus species planted in Mediterranean southwestern Australia. Tree Physiology 20: 1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KB, Baldocchi DD, Hanson PJ. 2000. Quantifying stomatal and non-stomatal limitations to carbon assimilation resulting from leaf aging and drought in mature deciduous tree species. Tree Physiology 20: 787–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Baldocchi DD. 2003. Seasonal trends in photosynthetic parameters and stomatal conductance of blue oak (Quercus douglasii) under prolonged summer drought and high temperature. Tree Physiology 23: 865–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Duursma RA, Medlyn BE, Kelly JW, Prentice IC. 2013. How should we model plant responses to drought? An analysis of stomatal and non-stomatal responses to water stress. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 182: 204–214. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Medlyn BE, Santiago S, Sperlich D, Prentice IC. 2014. Short-term water stress impacts on stomatal, mesophyll, and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis differ consistently among tree species from contrasting climates. Tree Physiology 34: 1035–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.