Mutations affecting epigenetic regulators have long been known to play a crucial role in cancer and, in particular, hematological malignancies (1, 2). One of the earliest epigenetic factors described altered in leukemia was mixed lineage leukemia (MLL), which is found translocated in 10% of adult acute myeloid leukemia (AML), 30% of secondary AML, and greater than 75% of infants with both AML and acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL). MLL is a SET domain containing protein, which is recruited to many promoters and mediates Histone 3 Lysine 4 (H3K4) methyltransferase activity, thought to promote gene expression (3).

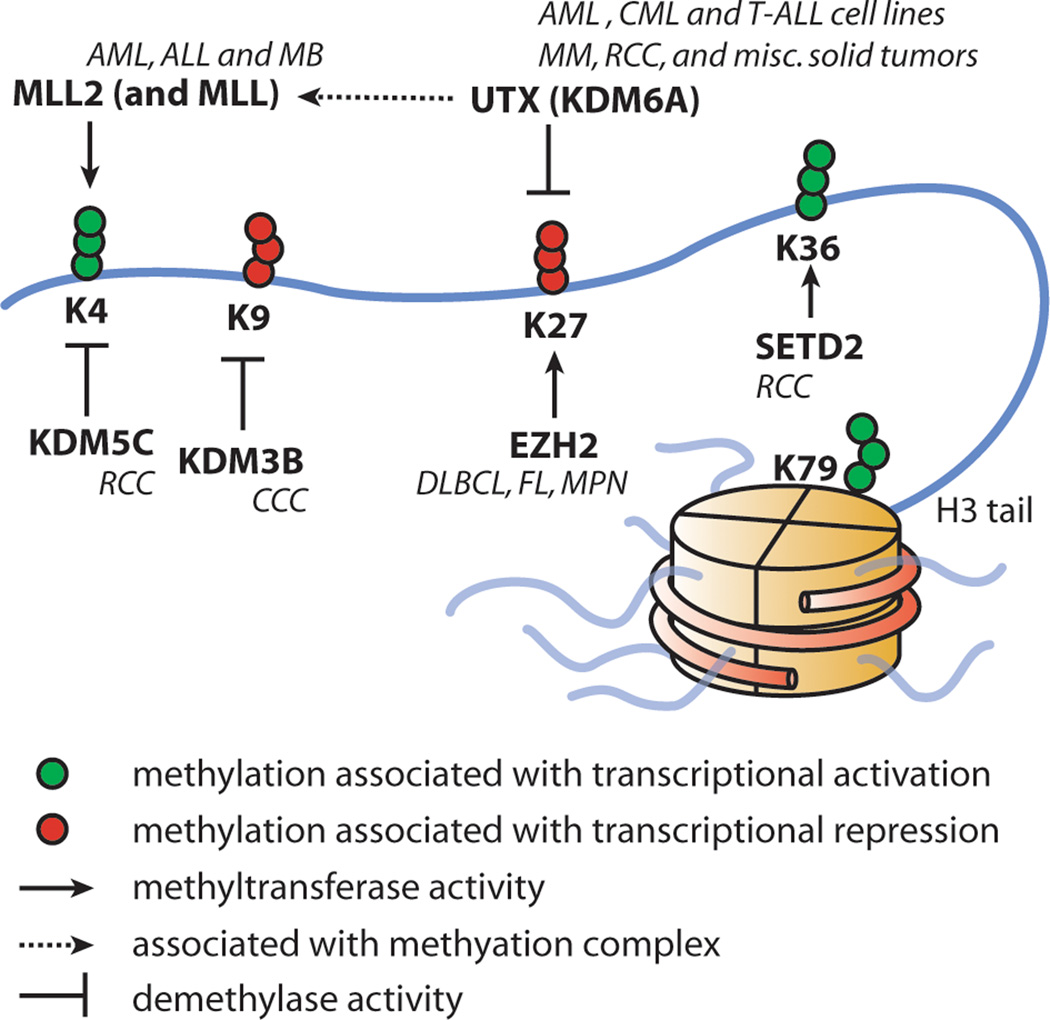

In addition to MLL fusions, recently, somatic mutations of UTX (also known as KDM6A), encoding a H3K27 demethylase, were described in multiple hematological malignancies including multiple myeloma and many types of leukemia cell lines (4, 5). H3K27 methylation is generally thought to cause gene repression. Complimentary to UTX, mutations of EZH2, a H3K27 methyltransferase, have been reported in both lymphoid and myeloid tumors (Figure 1) (6, 7). These mutations lead to altered EZH2 activity and influence H3K27 in tumor cells. Similarly, point mutations affecting the functional jumonji C (jmjC) domain of UTX inactivates its H3K27 demethylase activity. In addition, UTX associates with MLL2 in a multiprotein complex which promotes H3K4 methylation, and recently MLL2 has also been found mutated in cancer further pointing to a common and complex epigenetic deregulation in cancer (8). In line with the growing evidence for epigenetic regulators as important in tumorigenesis, additional mutations affecting epigenetic regulators such as SETD2, a H3K36 methyltransferase, KDM3B, a H3K9 demethylase, and KDM5C, a H3K4 demethylase, have been reported and are associated with distinct gene expression patterns (Figure 1) (4).

Figure 1.

Histone 3 methylation and selected histone demethylases and methyltransferases. Cancers are shown in italics next to the mutated protein they are associated with. MM: Multiple myeloma. AML: Acute Myeloid Leukemia. ALL: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. MLL: Mixed Lineage Leukemia. FL: Follicular Lymphoma. DLBCL: Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma. RCC: Renal Cell Carcinoma. CCC: Clear cell carcinoma. MPN: myeloproliferative neoplasm. MB: Medulloblastoma.

Though the clinical significance of these findings remains to be explored, it is evident that epigenetic deregulation is playing an important role in both lymphoid and myeloid leukemogenesis. Furthermore, with novel drugs at hand, such as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors or demethylating agents that can target and reverse epigenetic alterations, understanding the underlying molecular aberrations is of growing interest (9). We therefore undertook an effort to examine the prevalence of somatic mutations in genes encoding histone modifying proteins, in particular, KDM3B, KDM5C, UTX, MLL2, EZH2 and SETD2, which previously were reported mutated in cancer (4, 5).

For an initial screen, we analyzed banked diagnostic primary leukemia samples from 44 childhood B-cell ALL and 50 adult AML patients, and where available, used bone marrow samples obtained in complete remission to validate the somatic nature of the mutations. Samples had been collected with patient/parental informed consent from patients enrolled on Dana-Farber Cancer Institute protocols for childhood ALL [DFCI 00-001 (NCT00165178), DFCI 05-001 (NCT00400946)] or AML treatment protocols of the German-Austrian AML Study Group (AMLSG) for younger adults [AMLSG-HD98A (NCT00146120), AMLSG 07-04 (NCT00151242)], and the study was approved by the IRB of the participating centers.

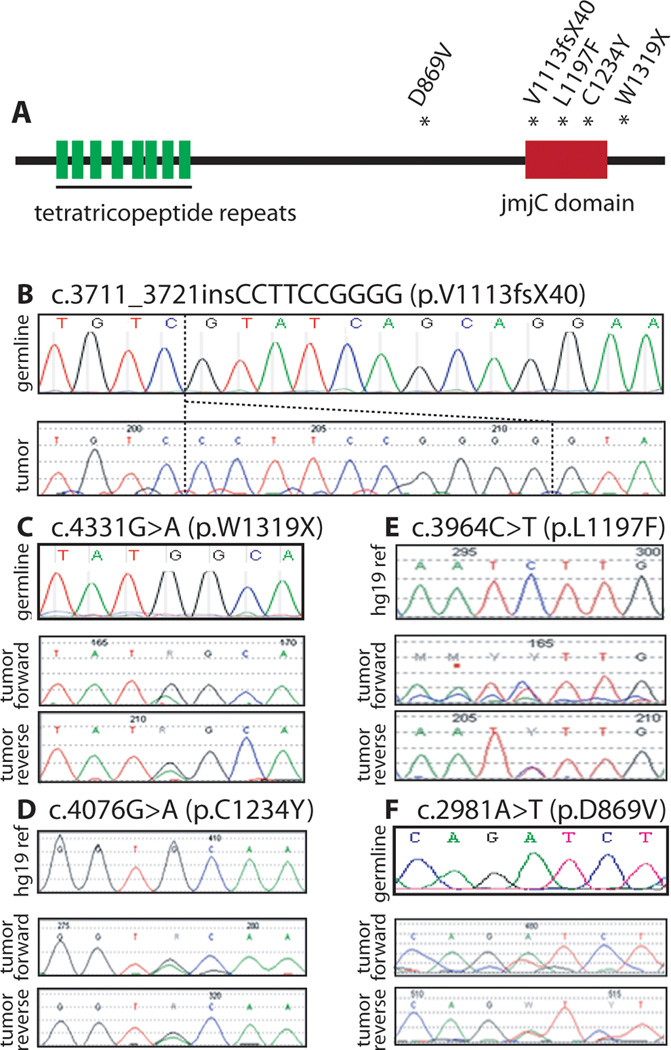

Using conventional Sanger sequencing of primary leukemia sample derived genomic DNA, we first screened all coding exons in which mutations have been reported previously (4, 5). Initially, we analyzed a total of 36 of 174 exons [KDM3B (2/24), KDM5C (9/26), UTX (7/29), MLL2 (8/54), EZH2 (1/20), and SETD2 (9/21)] and found 7 non-synonymous tumor-specific aberrations. In AML, we found one EZH2 mutation (p.G648E) in a t(8;21)-positive, and two MLL2 missense mutations (p.R5153Q and p.Y5216S; Table 1) and one MLL2 insertion leading to a frameshift in cytogenetically normal (CN) AML cases. UTX mutations (Figure 2 and Table 1) were found at a higher incidence (n=4), which included 2 heterozygous missense (p.L1197F and p.C1234Y), 1 hemizygous frameshift (c.3711-3721 insCCTTCCGGGG) at codon 1113 leading to 40 missense amino acids before a stop codon (p.V1113fsX40) and 1 heterozygous nonsense mutation (p.W1319X). Based on these findings we sequenced the remaining 22 UTX exons in our first cohort of 44 ALL cases and screened the entire coding region of UTX in an additional 94 B-cell ALL diagnosis samples. This analysis identified 1 additional missense (p.D869V), making 5 variants in 138 samples (4%; Table 1 and Figure 2). None of these polymorphisms were present in dbSNP build 131, which includes 1000 Genomes data. These mutations were validated as somatic in those with germline DNA available (3 of 5 patients). RNA from the patient with the D869V mutation was extracted and RT-PCR performed with UTX transcript specific primers. Sanger sequencing of the PCR product demonstrated expression of both the wildtype and mutant alleles, in approximately equal amounts (data not shown). In addition, according to profiles banked at the NIH Gene Expression Omnibus, UTX is expressed at high levels in both primary ALL and AML patient samples (10, 11).

Table 1.

Overview of Variants Found in AML and ALL

| Patient | Gender | Disease | Cytogenetics | Gene | DNA | Protein | Somatic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 560-D | Male | AML | t(8;21) | EZH2 | 2136G>A1 | p.G648E2 | Confirmed7 |

| 232-D | Female | AML | CN | MLL2 | 15458G>A3 | p.R5153Q4 | Confirmed7 |

| 692-D | Female | AML | CN | MLL2 | 15647A>C3 | p.Y5216S4 | Confirmed7 |

| 00-171 | Female | ALL | CN | MLL2 | 4498_4499insGG3 | p.G1500fsX64 | Confirmed7 |

| 00-A04 | Female | ALL | not available | UTX | 4076G>A 5 | p.C1234Y6 | N/A8 |

| 05-091 | Male | ALL | t(3;8),+8,dic(9;12) | UTX | 3711_3721 insCCTTCCGGGG5 |

p.V1113fsX406 | Confirmed7 |

| 00-D10 | Female | ALL | not available | UTX | 3964C>T5 | p.L1197F6 | N/A8 |

| 05-357 | Male | ALL | der(19),t(1;19)(q23;q13) | UTX | 4331G>A5 | p.W1319X6 | Confirmed7 |

| 05-046 | Female | ALL | CN | UTX | 2981A>T5 | p.D869V6 | Confirmed7 |

EZH2:

cDNA reference: NM_004456.4,

protein reference: NP_004447.2

MLL2:

cDNA reference: NM_003482.3,

protein reference: NP_003473.3

UTX:

cDNA reference: NM_021140.2,

protein reference: NP_066963.2

Germline material (remission bone marrow) was available and variant was confirmed to only be present in tumor material

Germline material was not available for this patient, thus this variant cannot be confirmed to be a somatic mutation

CN: cytogenetically normal

Figure 2.

UTX variants in ALL samples. A) schematic of the protein structure of UTX. Mutations identified in ALL samples are indicated by the asterisks. B) (top) germline sequence. (bottom) forward sequence. C, F) (top) germline sequence. (middle) forward (bottom) reverse D, E) (top) hg19 reference chromatograph generated by mutation surveyor (no germline material available). (middle) forward (bottom) reverse

The frameshift observed at codon 1113 of UTX truncates the protein in the jmjC domain (Figure 2B). Similarly located frameshift mutations leading to truncation were described in bladder transitional cell carcinoma, colorectal adenocarcinoma, multiple myeloma, and renal cell carcinoma samples (5). The mutation p.W1319X leads to a stop codon located in the C-terminal end, truncating 81 amino acids with a preserved jmjC domain (Figure 2C). Similarly located mutations were described in colorectal adenocarcinoma and renal cell carcinoma samples (5). Of the missense mutations observed in the jmjC domain p.C1234Y was predicted by PolyPhen (12) to be damaging while p.L1197F was predicted to be benign based on the possible impact of the amino acid substitution on the structure and function of the protein (Figure 2D).

UTX is found on the X chromosome and interestingly, 2 of the 5 variants we found were in males and thus hemizygous (p.V1113fsX40 and p.W1319X). In the patient with W1319X, the single nucleotide variant traces show the remaining wildtype allele, which is likely to be a small amount of normal hematopoietic cells, or a tumor cell subclone lacking the mutation. A homolog of UTX, called UTY, exists on the Y chromosome, however in vivo studies show that purified UTY does not completely recapitulate the activity of UTX (13). The other mutations were found heterozygous in female patients, however, this gene has been shown to escape X inactivation (14), consistent with the finding that both alleles are expressed in the patient with the D869V mutation. As most mutations in UTX are thought to cause loss of function, it is possible that UTX gene dosage may be critical. Alternatively, these mutants have the potential to act as gain of function dominant negatives, as they preserve the protein interacting tetratricopeptide repeats at the N-terminus of UTX.

In conclusion, our analysis in acute leukemia revealed mutations in the histone modifying enzymes recently identified to be altered in other cancers, particularly UTX in ALL and MLL2 in AML, although not at a high incidence. Important to note, is that UTX and MLL2 are part of the same protein complex and both MLL2 and UTX mutations may lead to similar phenotypic consequences in cancer cells. Also, MLL2 was not fully sequenced in our analysis, leaving open the possibility of additional mutations in AML. Nevertheless, our findings warrant further analyses within larger studies and most likely more comprehensive studies based on targeted or whole genome/exome next-generation sequencing approaches. Of interest, most of UTX mutations observed in our study were found in clinically defined high-risk patients and at least 1 of those patients (05-046) eventually relapsed. Therefore, this observation might be of particular interest with regard to potential epigenetic treatment approaches, although the exact mechanisms of transformation in UTX-mutated ALL remain to be elucidated.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NCI P01CA684841 and the Charles Hood Foundation. L.B. was supported in part by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Heisenberg-Stipendium BU 1339/3-1).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Claus R, Plass C, Armstrong SA, Bullinger L. DNA methylation profiling in acute myeloid leukemia: from recent technological advances to biological and clinical insights. Future Oncol. 2010 Sep;6(9):1415–1431. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neff T, Armstrong SA. Chromatin maps, histone modifications and leukemia. Leukemia. 2009 Jul;23(7):1243–1251. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slany RK. The molecular biology of mixed lineage leukemia. Haematologica. 2009 Jul;94(7):984–993. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.002436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C, Chen L, Bignell G, Butler A, et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010 Jan 21;463(7279):360–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Haaften G, Dalgliesh GL, Davies H, Chen L, Bignell G, Greenman C, et al. Somatic mutations of the histone H3K27 demethylase gene UTX in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2009 May;41(5):521–523. doi: 10.1038/ng.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernst T, Chase AJ, Score J, Hidalgo-Curtis CE, Bryant C, Jones AV, et al. Inactivating mutations of the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 in myeloid disorders. Nat Genet. 2010 Aug;42(8):722–726. doi: 10.1038/ng.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morin RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM, Mungall AJ, An J, Goya R, et al. Somatic mutations altering EZH2 (Tyr641) in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of germinal-center origin. Nat Genet. 2010 Feb;42(2):181–185. doi: 10.1038/ng.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parsons DW, Li M, Zhang X, Jones S, Leary RJ, Lin JC, et al. The genetic landscape of the childhood cancer medulloblastoma. Science. 2011 Jan 28;331(6016):435–439. doi: 10.1126/science.1198056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin L, Gray JW. Translating insights from the cancer genome into clinical practice. Nature. 2008 Apr 3;452(7187):553–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marston E, Weston V, Jesson J, Maina E, McConville C, Agathanggelou A, et al. Stratification of pediatric ALL by in vitro cellular responses to DNA double-strand breaks provides insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying clinical response. Blood. 2009 Jan 1;113(1):117–126. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-142950. GEO accession number GDS3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metzeler KH, Hummel M, Bloomfield CD, Spiekermann K, Braess J, Sauerland MC, et al. An 86-probe-set gene-expression signature predicts survival in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008 Nov 15;112(10):4193–4201. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-134411. GEO accession number GDS3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010 Apr;7(4):248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lan F, Bayliss PE, Rinn JL, Whetstine JR, Wang JK, Chen S, et al. A histone H3 lysine 27 demethylase regulates animal posterior development. Nature. 2007 Oct 11;449(7163):689–694. doi: 10.1038/nature06192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenfield A, Carrel L, Pennisi D, Philippe C, Quaderi N, Siggers P, et al. The UTX gene escapes X inactivation in mice and humans. Hum Mol Genet. 1998 Apr;7(4):737–742. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.4.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]