INTRODUCTION

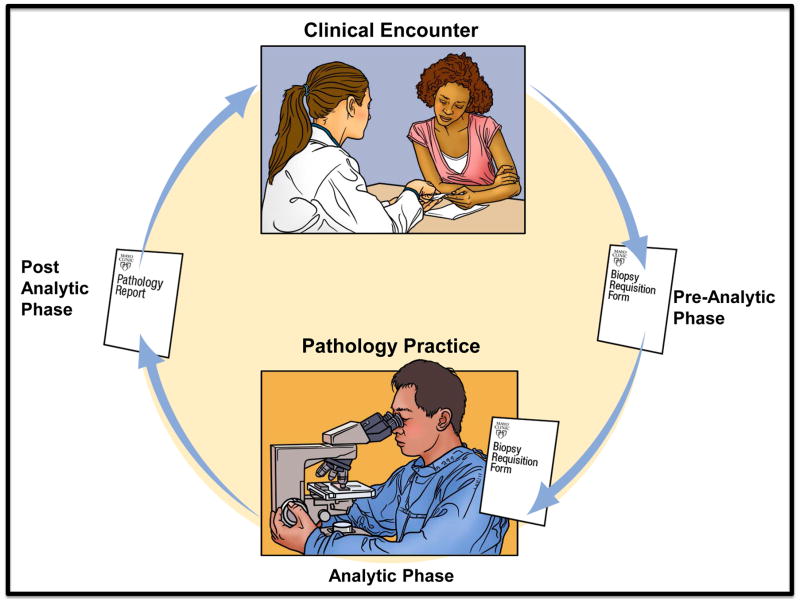

Ineffective communication and failures in information transfer among health care providers plays a significant role in sentinel events and critical medical incidents [1] including laboratory medicine and skin pathology [2,3]. Diagnostic errors, [4,5] occur frequently (10–20%) and in dermatopathology, may occur at any point in the process resulting in adverse patient outcomes and increased healthcare costs. In one survey, pre-analytic errors accounted for 23% of medical errors in dermatology practice [6]. Each step in the skin biopsy care process is dependent on clear communication. Ideally, a specific clinical question accompanies an adequate sample to a pathologist who performs histopathologic interpretation – the gold standard for diagnosis – that is then sent back to the requesting clinician to help guide management. In reality, dermatopathologists often are given incomplete or inaccurate clinical information that hinders their ability to efficiently make diagnostic decisions and relay a definitive diagnosis back to the requester. [7]

The skin biopsy requisition form serves as the primary and usually critical mode of communication between clinician and pathologist, but is susceptible to many of the problems associated with handoffs. The limited literature in dermatology highlights frequent missing clinical information in the requisition form that creates daily practice challenges for pathologists. This study aims to describe and evaluate the perceptions of the American Society of Dermatopathology (ASDP) members about the quality of clinical information from clinicians through an explanatory sequential mixed methods design.

METHODS

Ethical Review

This study was reviewed and approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and the Board of Directors of the ASDP.

Design: Mixed Methods Explanatory Sequential Design

We used a mixed methods approach to describe and evaluate the perceptions of dermatopathologists about the quality of clinical information from requesting clinicians using both quantitative and qualitative data and then integrating this data by connecting themes identified in a survey (quantitative study) using detailed perspectives gathered in focus group sessions (qualitative study). The ‘explanatory sequential design’ has been described previously [8].

Questionnaire Development and Administration

First, we sent a self-administered paper survey to practicing dermatopathologist members of the American Society of Dermatopathology (ASDP). In that survey we assessed the predominant mode of communication of clinical information in the skin biopsy care process, perceived impact of missing clinical information in the requisition form on diagnostic performance and work efficiency and diagnostic uncertainty associated with limited clinical information in the requisition form domains. The primary aim of the questionnaire was to gather self-reported concerns and challenges of dermatopathologists with the quality of clinical information provided in the requisition form. In order to develop the survey we conducted literature review, question development and pilot review of draft survey questions with pathologists. Their feedback informed the final questionnaire.

Primary physician characteristics were captured in responses to two key questions, ‘ Which of the following best describes how you view your role as a dermatopathologist?’ (1- It is my job to provide only a specific histopathologic diagnosis and description of the pertinent histopathologic findings, 2 – It is my job to provide only a clinically meaningful histopathologic interpretation that incorporates guidance in clinical decision making, 3 – Both of the above and 4 – None of the above) and ‘What was the nature of your residency and fellowship training?’ (Dermatology residency, Pathology residency or Other, please specify). We also included a case vignette with key clinical information and supportive pathologic images to gauge respondents’ reactions to missing or incomplete clinical information. The case vignette represented a shave biopsy from the right helix of a 50-year-old woman with clinical impression ‘rule out skin cancer’. Two hematoxylin and eosin-stained histopathologic images were provided --low magnification, 4X and high magnification, 10X). We adapted two questions (Q20) from the ‘Physician’s Reaction to Uncertainty’ (PRU) scale by Gerrity MS et. al. to measure reactions to diagnostic uncertainty in dermatopathology practice (9) (used with permission from MS Gerrity). The original instrument development included 61 items completed by 700 physicians using a 6-category response scale (strongly disagree, moderately disagree, slightly disagree, slightly agree, moderately agree, strongly agree). We used a 4-category response scale (strongly disagree, moderately disagree, moderately agree and strongly agree).

Framing variables obtained from the survey included physician demographics, practice setting (academic or community), method of compensation (fee-for-service and salary with or without bonus), number of pathologists interpreting skin specimens in the practice group, annual and daily dermatopathology case volumes in the practice and proportion of the practice devoted to dermatopathology specimens. Two categories of referring providers, 1) dermatology only and 2) combination of primary care, general surgery and surgical subspecialists and pathologists were created for ease of comparison. Two authors (MP and NC) independently reviewed respondent comments.

This eleven page, self-administered paper survey in its final phase was mailed to all practicing ASDP members (1103) between October 2012 and March 2013. Non-respondents were given 2 additional chances to respond. The initial mailing included a cover letter informing recipients that their responses would be anonymous and included the gift of a laser pointer pen. Second and third mailings were sent to non-responders 5 weeks apart and included a reminder cover letter in addition to the questionnaire.

Focus Group Sessions

Subsequent to the survey, we conducted two focus groups to enhance our interpretation of survey data and deepen our understanding of the challenges they face with incomplete clinical information. These sessions involved a trained facilitator (NC for the first, KH for the second) leading a conversation about physician work flows around these issues with topics such as: Outline of a typical day in the life of a dermatopathologist, ‘quality’ of skin biopsy specimens and clinical information in requisition forms, strategies used to manage inadequate skin biopsy specimens or missing clinical information and strategies for providing clinician feedback on the skin biopsy care process. We conducted these as groups at two separate continuing medical education meetings of dermatologists and dermatopathologists in 2013.

Study Participants and Data Collection

All ASDP members listed as practicing dermatopathologists (not limited to members employed in the US), were asked to participate in the survey (Figure 1). Focus group participants were identified using convenience sampling at two separate dermatology/dermatopathology meetings.

Figure 1.

ASDP Survey Questionnaire (view online at: need online link here)

Analysis

The primary survey outcomes addressed in this manuscript include physician self-reported concerns with 1) the quality and completeness of provided clinical information and, 2) the impact of this information on the quality of histopathologic diagnosis. The survey data were summarized using frequencies and percentages for categorical and ordinal characteristics. Bivariate associations between physician characteristics including responses to the two key questions (see section in Methods, ‘Questionnaire development and administration’) and our primary outcomes were tested using Kruskal Wallis (ordinal data) or Fisher Exact (categorical data) tests, as appropriate. Two sided p </= 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SAS version 9.3 was used to perform all statistical analyses (Cary, NC).

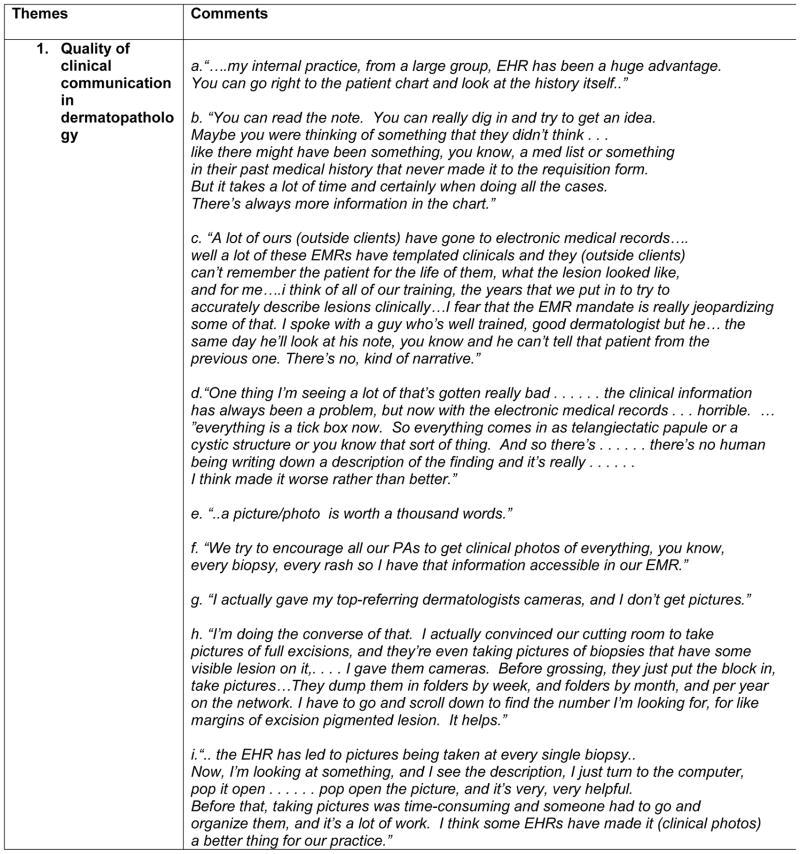

Qualitative data from the focus groups were categorized into major themes: 1- quality of clinical information in dermatopathology, 2 – quality of skin biopsy specimens, 3- strategies for managing inadequate biopsy specimens and missing or inaccurate clinical information and 4 – suggestions for improvement of the skin biopsy care process.

RESULTS

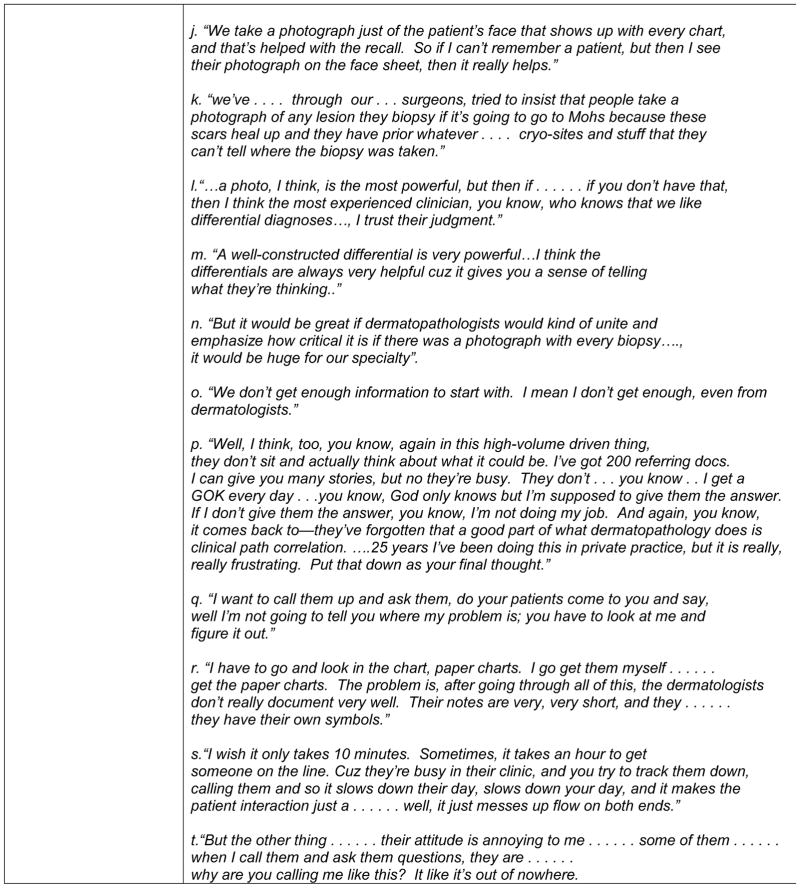

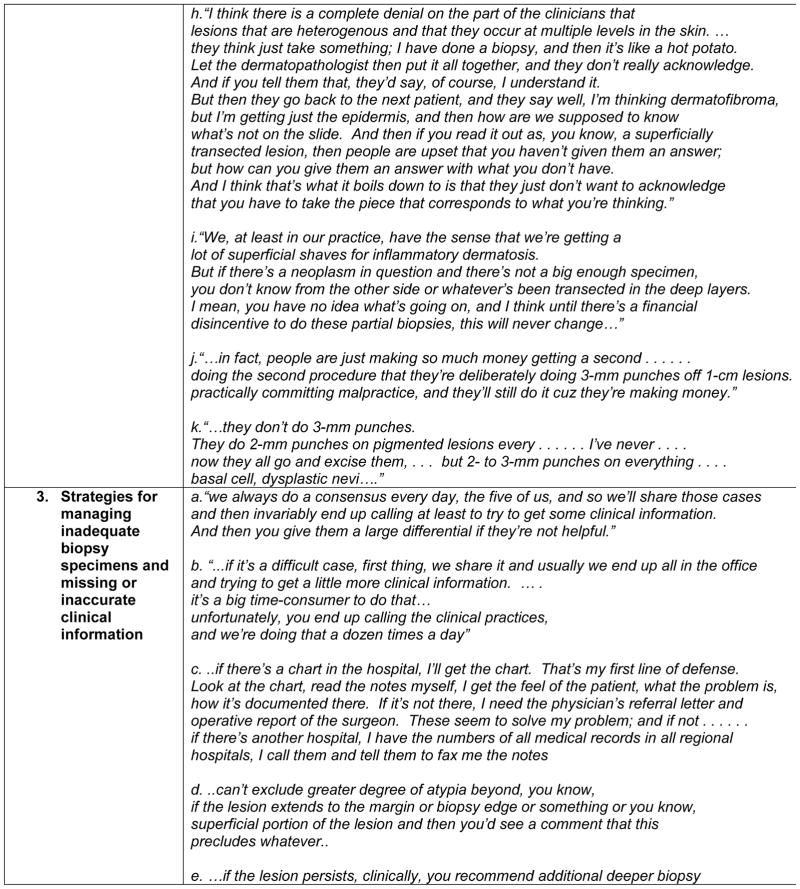

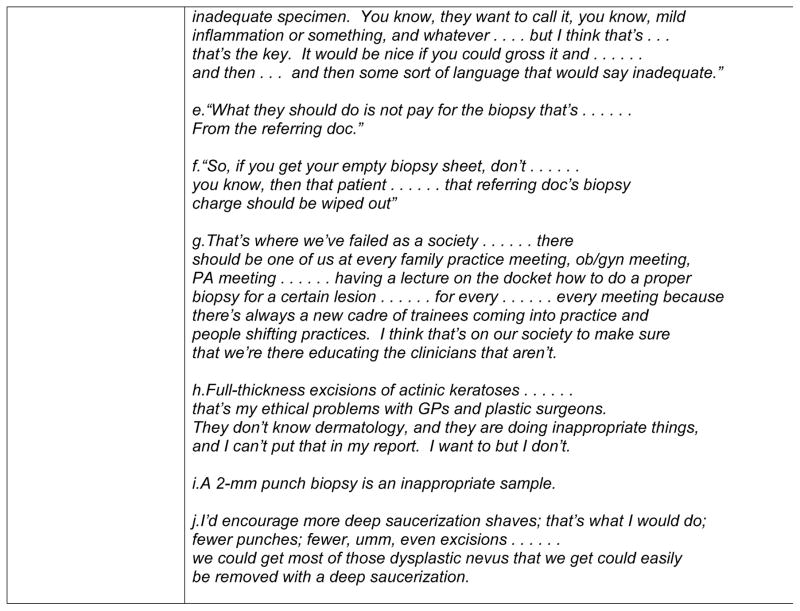

Out of 1103 dermatopathologists sent a survey, 1 was lost due to problems with labeling. Among the remaining 1102 potential respondents, 598 completed and returned the questionnaire (response rate, 54%). Table 1 summarizes respondent characteristics. A summary of selected comments from the two focus group sessions is presented in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Self-reported characteristics of 598 ASDP Dermatopathologist Survey Respondents

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 52 (11) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 389 (67%) |

| Female | 192 (33%) |

| Years of Interpretation | |

| Less than 5 years | 89 (15%) |

| 5 to 10 years | 138 (23%) |

| More than 10 years | 366 (62%) |

| Training | |

| Dermatology residency + DP fellowship | 215 (38%) |

| Pathology residency + DP fellowship | 297 (52%) |

| Daily interpretive volume | |

| Less than 50 cases | 235 (40%) |

| 50 to 80 cases | 194 (33%) |

| More than 80 cases | 158 (27%) |

| Proportion of practice devoted to dermatopathology | |

| Less than 50% | 168 (28%) |

| 50 to 80% | 117 (20%) |

| More than 80% | 265 (45%) |

| No of pathologists interpreting skin specimens in practice | |

| 1 | 133 (23%) |

| 2 to 5 | 359 (61%) |

| 6 to 10 | 78 (13%) |

| More than 10 | 21 (4%) |

| Referral base | |

| Dermatology only | 311 (55%) |

| Primary care, General Surgery, or Pathologist | 259 (45%) |

| Primary practice organization | |

| Community DP practice with academic affiliation | 165 (28%) |

| Community DP practice without academic affiliation | 208 (36%) |

| University-affiliated DP practice | 147 (25%) |

| Other | 64 (11%) |

| Method of reimbursement | |

| Fee-for-service | 215 (37%) |

| Salary only | 129 (22%) |

| Salary plus bonus | 208 (36%) |

Figure 2.

Impact of quality of clinical information on diagnostic performance

High level summary of demographics and key attitudinal covariates: 67% of respondents were male, had completed pathology residency training prior to dermatopathology fellowship (52%), were in practice for more than 10 years (62%), are situated in community dermatopathology practices without an academic affiliation (36%) and report that dermatologists are their primary referral source (55%). 436 of 548 (79.6%) respondents viewed their role in practice broadly, as providers of 1) specific histopathologic diagnosis with description of pertinent histopathologic features and 2) clinically meaningful histopathologic interpretation that incorporates consideration of the influence of the report on clinical decision making. Higher mean scores (3.4/4; 1= strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) in response to diagnostic uncertainty on the PRU scale were noted in this respondent group (91.2%) with a broadly perceived scope of practice. Paper or electronic requisition forms (84.7%; 458/541) were most commonly used by clinicians and were associated with the highest rates of dissatisfaction (‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ dissatisfied) in 36% (193/537).

Primary Outcomes

Quality and completeness of clinical information and biopsy specimens

42.7% (239/559) of respondents rated the quality of clinical information provided by clinicians as either fair or poor. 78.9% (440/558) felt that the dermatologic experience of the requesting clinician is ‘very’ important to the quality of provided clinical information. Higher ratings of receiving quality clinical information (good, very good or excellent) were noted by respondent groups whose predominant referral base constituted dermatologists as compared with non-dermatologists (188/297; 63.3% vs. 117/242; 48.3% p= 0.0023).

Missing relevant clinical information necessary for histopathologic interpretation was common (about half the time> half the time or always) across three broad disease categories: melanocytic proliferations (53.7%; 298/555), non-melanocytic proliferations (57.4%; 318/554) and inflammatory dermatoses (59.1%; 328/555). Clinical photographs of the lesion or dermatosis was highlighted by focus group participants as an important and potentially sufficient sole piece of clinical information in the absence of a clinical description (Theme 1k,l,f). In the words of multiple participants, “a photo is worth a thousand words” (Theme 1e). EHRs with applications that facilitate the easy upload of clinical images directly into the record have improved clinical efficiency and utility of photo capture devices in busy dermatology practices (Theme 1i). However, despite innovative solutions such as giving cameras to referring clinicians in some practices, skin biopsy specimens accompanied by clinical photos is not standard practice (Theme 1g), because of obstacles that include time and resource constraints associated with image storage, archiving and privacy concerns.

Focus group participants noted multiple benefits and limitations of visit notes in the EHR. While access to accurate clinical information was a commonly cited advantage, the time and effort required to identify relevant clinical information in the EHR was a significant negative. In particular, the yield of relevant clinical information varied depending on the dermatologic expertise of the clinician. Participants noted that visit notes prepared by dermatology-trained providers (physicians or physician extenders) compared with non-dermatology trained providers, offered information higher in quality and relevance to histopathologic interpretation. A limitation of the EHR is the increasing use of ‘templated’ visit notes or check boxes with pre-filled phrases, which generally lack the rich clinical narrative descriptions useful in histopathologic interpretation. Such templates were noted to adversely impact clinician recall of critical clinical information (Themes 1, a-d). Some practices have devised strategies such as the attachment of a photograph of the patients’ face to the visit note to aid provider recall (Theme 1j). Respondents who receive biopsy specimens from non-dermatologists (primary care, general surgery or pathology) cited higher rates of dissatisfaction (somewhat or very dissatisfied) with the paper/electronic requisition form as compared with those who received biopsy specimens from dermatologists only (99/233; 42.5% vs. 91/287; 31.7% p= 0.0223) (Table 2). Frustrations due to difficulty reaching clinicians via the telephone and inaccuracy of clinical information supplied in the requisition forms typically completed at the end of the day by members of the healthcare team who were not necessarily involved in the skin biopsy were expressed. Most focus group participants similarly highlighted frequent fruitless daily attempts to seek clinical information through various means including phone calls, email messages, text messages with physicians or support staff, direct access to the electronic health record (EHR) visit notes and paper medical charts (Themes 1k-o).

Table 2.

Modes and quality of clinical communication by predominant referral base

| Referral Type | Dermatology only (N=311) | Primary Care, General Surgery, Pathology (N=259) |

|---|---|---|

| Role as a dermatopathologist | ||

| Role 1 – Provide specific histopathologic diagnosis and description of findings. | 26/290 (9%) | 19/235 (8%) |

| Role 2 – Provide clinically meaningful histopathologic interpretation and guidance on decision making and specific histopathologic diagnosis and description of findings | 260/290 (90%) | 214/235 (91%) |

| Level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with paper/electronic requisition forms used by requesting clinicians for conveying clinical information related to skin biopsy specimens | ||

| Very or somewhat satisfied | 196/287 (68%) | 134/233 (58%) |

| Very or somewhat dissatisfied | 91/287 (32%) | 99/233 (42.5%) |

| For information that is provided by requesting clinicians, please rate the quality of that information | ||

| Good, very good or excellent | 188/297 (63%) | 117/242 (48%) |

| Fair or poor | 109/297 (37%) | 125/242 (52%) |

| In your experience, how important is the dermatologic experience of the requesting clinician to the quality of the clinical information provided? | ||

| Very or somewhat important | 279/293 (95%) | 236/244 (97%) |

| Not important | 14/293 (5%) | 8/244 (3%) |

Biopsy specimen adequacy was raised as a concern in the skin biopsy care process with implications for the quality of histopathologic interpretation. Focus group participants emphasized the poor quality of skin biopsy specimens, such as curettings or superficial shave biopsies of inflammatory dermatoses including panniculitis and partial samples (curettings, 2 or 3mm punch biopsies) of pigmented lesions including melanomas. The practice of obtaining small biopsy specimens was noted to be more common in private or community practices than academic settings and was dependent on specific provider preferences and expertise. Errant providers were typically not responsive to feedback either directly or via the pathology report, such as in the ‘comment’ field - strategies employed by dermatopathologists to address specimen inadequacy. Common reasons suggested by participants for the above trends include lack of provider knowledge about appropriate skin biopsy techniques, extra time and effort associated with performance of adequate skin biopsies, poor clinical outcomes and subsequent patient dissatisfaction associated with pathologically optimal biopsies, delegation of the skin biopsy to less-skilled members of the health care team, perverse financial incentives, skewed priorities with overemphasis on cosmesis and shifting of diagnostic decision making responsibility to the pathologist (Theme 2, a-k)

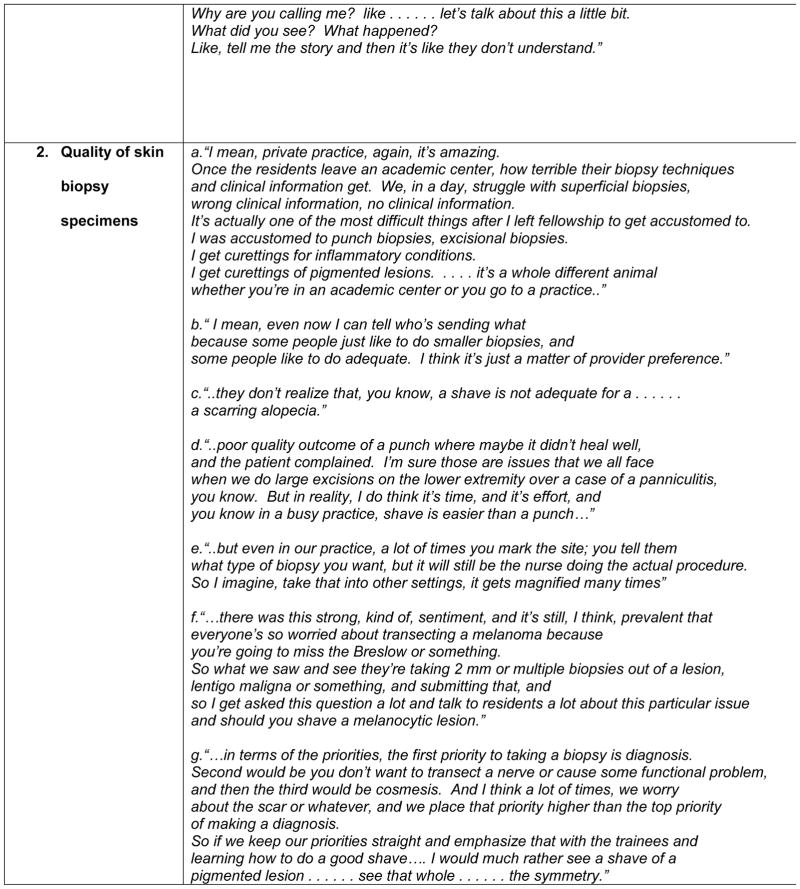

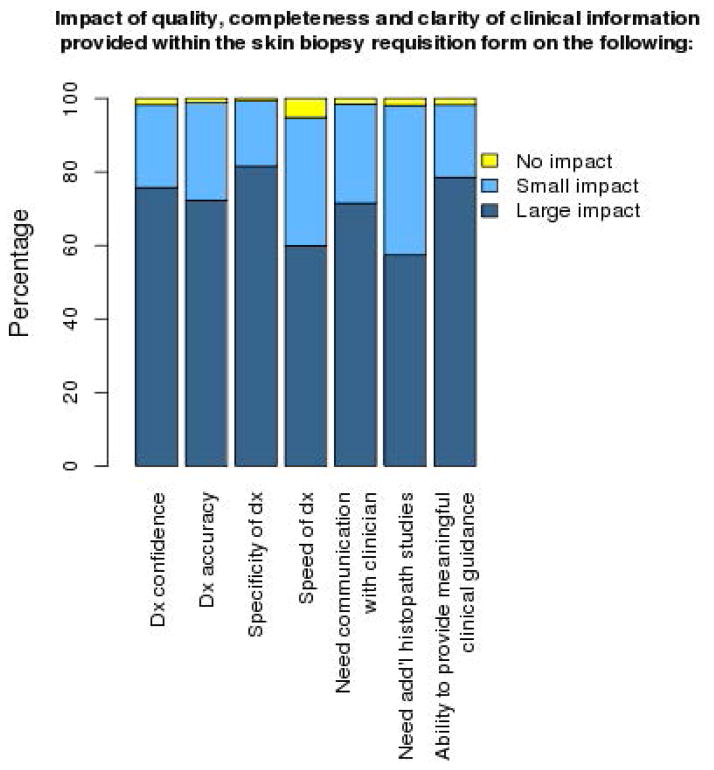

Impact of information on timely, high quality histopathologic diagnosis

44.7% (261/584) of dermatopathologists spent 30 minutes or more on average every day searching for relevant clinical information to assist with their histopathologic interpretation. Responses to a case vignette with limited clinical information demonstrated stress associated with uncertainty of diagnosis (Table 3). A majority of respondents (>70%) noted that the quality, completeness and clarity of clinical information provided within the RF has a ‘large’ impact on their diagnostic confidence, diagnostic accuracy, specificity of diagnosis, need for additional communication with the requesting clinician and their ability to provide a report with meaningful clinical guidance (Figure 3). In addition, 57.4% (333/580) of respondents noted that their need for additional histopathologic studies is influenced by the quality and completeness of provided clinical information.

Table 3.

Time and effort associated with gathering necessary clinical information

| Missing clinical information >/= 50% of the time | |

| Melanocytic proliferations | 298 (54%) |

| Non-melanocytic neoplasms | 318 (57%) |

| Inflammatory dermatoses | 328 (59%) |

| Average time spent searching for clinical information | |

| None | 21 (4%) |

| Less than 30 minutes | 302 (52%) |

| 30 minutes or more | 261 (44%) |

| Case Vignette | |

| Level of comfort with rendering diagnosis | |

| Very comfortable | 126 (22%) |

| Moderately comfortable | 293 (50%) |

| Not at all comfortable | 162 (28%) |

| Need for additional clinical information to render accurate histopathologic interpretation | |

| No | 145 (27%) |

| Yes | 387 (73%) |

| Need for additional elaboration on histopathologic findings within ‘comment’ field of pathology report | |

| Usually | 262 (45%) |

| Maybe but not always | 206 (35%) |

| Rarely | 102 (18%) |

| Never | 12 (2%) |

| Physicians’ Stress from Uncertainty scale | |

| Vague clinical impressions or missing relevant clinical information in DP makes me uneasy | |

| Strongly disagree | 28 (5%) |

| Moderately disagree | 24 (4%) |

| Moderately agree | 265 (45%) |

| Strongly agree | 272 (46%) |

| I find the absence of clinical information in DP practice disconcerting | |

| Stromgly disagree | 33 (6%) |

| Moderately disagree | 27 (5%) |

| Moderately agree | 201 (34%) |

| Strongly agree | 324 (55%) |

Figure 3.

Focus Group Select Comments

Several strategies were employed by focus group participants to manage missing or inaccurate clinical information and inadequate biopsy specimens: 1) daily group consensus conferences among dermatopathology staff (Theme 3a); 2) communication with the clinician or support staff through email messages, phone calls, text messages; 3) report a broad pathologic differential diagnosis (Theme 3b); 4) chart review by faxed paper charts or having support staff read the relevant portions of the visit note by phone (Theme 3c); 5) use of the comment field in the pathology report to highlight potential limitations of the histopathological diagnosis because of poor sample quality or limited clinical information (Theme 3d–g); 6) generation of a medical note in the EHR by the pathologist reflecting the inadequacy of the sample and/or clinical information (Theme 3h); 7) including representative photomicrographs in the pathology report (Theme 3i) and 8) offering interpretation of a second skin biopsy sample for free (Theme 3j). Participants noted that all of the above require significant time, effort, and expense by pathologists, as well as frequent interruptions during the work day of both pathologists and clinicians, which adversely impacts work efficiency, productivity and satisfaction.

Key associations with primary outcomes

1. Scope of dermatopathology practice

In bivariate tests of association, we found that diagnostic unease with vague clinical impressions was associated with respondents whose perceived scope of practice was defined broadly as compared to those with narrowly defined scopes of practice (Mean scores on scale of 1= strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree: 3.4 vs. 3.1 respectively p= 0.0028). There was either moderate or strong agreement with the phrase, ‘vague clinical impressions or missing relevant clinical information in dermatopathology makes me uneasy’, (91.2%; 537/589) and ‘I find the absence of clinical information in dermatopathology practice disconcerting’ (89.7%; 525/585) for most respondents. Dermatopathologists with narrowly perceived scopes of practice were more likely to spend less time (less than 30 minutes) daily, actively searching for relevant information as compared to those with broadly perceived scopes of practice (71.7%; 33/46 vs. 53.6%; 260/485 p = 0.003). Rates of missing relevant information for inflammatory dermatoses was significantly different between respondent groups with broadly vs. narrowly perceived practice scopes (295/486; 60.7% vs. 21/46; 45.6% p = 0.046). While most (491/581; 72.1%) respondents were either moderately or very comfortable with making a diagnosis based on the vignette images, dermatopathologists with narrowly perceived scopes of practice were more likely to indicate higher levels of discomfort (29%) and to require additional clinical information (44%) for accurate histopathologic interpretation, as compared to those with broadly perceived scopes of practice (11% discomfort, 25% required additional information) (p = 0.001 and 0.01, respectively). Furthermore, 45% (262/582) of dermatopathologists would typically elaborate on the histopathologic findings in the ‘comment’ field of their report, particularly those with broadly vs. narrowly perceived scopes of practice (218/482; 45.2% vs. 16/46; 34.8% p = 0.03).

2. Nature of training pathway

Respondents with pathology training were more likely to perceive a broad definition of their role than those with dermatology training (93.1% vs. 86.9%; p = 0.004). Paper/electronic requisition forms and phone calls were common modes of communication, utilized more frequently by those with pathology backgrounds (86.7% vs. 84.3% for paper/electronic requisition forms and 10.1% vs. 7.9% for telephone; p = 0.0002). In contrast, face-to-face/oral communication was more commonly used by respondents with dermatology vs. pathology backgrounds (6.3% vs. 1.1%; p = 0.0002). Respondents with dermatology training were more likely to rate the quality of clinical information provided by requesting clinicians as good, very good or excellent (63.7% vs. 52.6%; p = 0.02). Additionally, dermatology-trained dermatopathologists were more likely to spend less than 30 minutes (60.6% vs. 40.8%; p <0.0001) on an average day searching for clinical information to assist with histopathologic interpretation. Pathology-trained dermatopathologists were however, more likely to spend 30 minutes or more each day (57.1% vs. 34.7%; p<0.0001) searching for clinical information. Furthermore, there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups in their perception of the impact of the quality and completeness of provided clinical information on the ‘need for additional communication with the requesting clinician’ (80.2% vs. 65.6%; p<0.0001). There were no differences noted between the groups based on the impact of provided information on diagnostic confidence, accuracy, specificity and speed, need for additional histopathologic studies or ability to provide meaningful clinical guidance. Both groups appeared similar with respect to the case vignette and reactions to uncertainty in dermatopathology practice.

An additional notable association included a significant difference in the responses to the impact of the dermatologic expertise of the referring clinician on the quality of clinical information between those with dermatology only vs. non-dermatology (primary care, general surgery and pathology) referral bases (218/293; 74.4% vs. 203/244; 83.2% p= 0.0146) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This survey and the follow-up focus group data, demonstrate that dermatopathologists perceive that clinical information is crucial for accurate, timely and efficient dermatopathologic interpretation, but that information is missing or inaccurate about half of the time. Furthermore, dermatopathologists reported high rates of dissatisfaction with clinician-pathologist communication in the skin biopsy care process and stress related to diagnostic uncertainty due to missing or inaccurate clinical information. Many of these attitudes are based on whether they viewed their diagnostic role narrowly or broadly. These findings, in conjunction with previous studies [10,11] lend support to the importance of clinical and pathological correlation in dermatopathology and document the importance of considering clinical context in histopathologic interpretation.

The requisition form is the primary mode of clinician-pathologist communication and is often the object of disdain amongst dermatopathologists because of frequent missing and inaccurate clinical information. 45% of dermatopathologists spent 30 minutes or more every day gathering clinical information missing in the RF, by alternate means of communication with clinicians. These daily disruptions were noted to adversely affect both clinicians and pathologists, and were perceived to contribute to practice inefficiencies. Respondents who spent at least 30 minutes daily actively searching for clinical information predominantly relied on the use of telephone or paper/electronic requisition forms to support clinician-pathologist communication. This may reflect barriers to effective use of requisition forms by clinicians or suggest that pathologists who seek additional information are those who value a more comprehensive clinical picture. This stands in contrast to groups reliant on face-face communication that spend less than 30 minutes per day on average searching for clinical information. This is likely due to the ease and efficiency associated with face-to-face communication for directly addressing clinical inquiries with a bearing on pathology interpretation. Some respondents who provide pathology services to dermatology groups also highlighted the value of proximity to the clinical practice, which enables joint clinician-pathologist examination, facilitating viewing of the ‘gross’ pathology and procurement of relevant clinical information. Most respondents who reported satisfaction with the paper/electronic requisition form spent < 30 minutes daily searching for clinical information, which might reflect inherent characteristics of requisition forms or reflect the pathologist’s style/approach. Progressively lower levels of satisfaction with the paper/electronic requisition form corresponded to increasing time spent searching for clinical information. A similar trend was not observed for other modes of communication. Ratings of good or better on the quality of clinical information submitted were more commonly noted with decreasing amount of time spent searching for clinical information.

Despite the benefits of a shared EHR, information-gathering efforts may result in variable yields, perceived as a function of the dermatologic expertise of the clinician [7]. When responses were evaluated by composition of the referral base, there were significantly higher rates of dissatisfaction with the quality of clinical information submitted by non-dermatologists than by dermatologists. Respondents who received a majority of their skin specimens from non-dermatologists were more likely to rate the information provided according to the training of the clinician as either ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ important, supporting our hypothesis that the quality of clinical information may be related to the dermatologic expertise of the clinician. Pathologists have devised a number of ‘workarounds’ for managing communication deficiencies in practice with unclear but likely not insignificant costs to quality of care. The adequacy of biopsy specimens submitted for pathologic interpretation emerged as a significant concern. The increasing trend towards partial sampling appears to be multifactorial including provider preferences, patient preferences, cosmetic outcomes and practice related factors. Limited literature on this trend emphasizes its potential adverse impact on the quality of patient care [12].

Several significant differences in opinions on the role of clinical information in dermatopathology were noted when responses were assessed by pathologist training pathway – 1: dermatology residency and dermatopathology fellowship, 2: pathology residency and dermatopathology fellowship and 3: other. Higher proportions of respondents with training type 1 as compared to 2 reported longer years of dermatopathology experience and larger yearly case volumes (> 60,000), likely reflecting practice in larger pathology laboratories by those with training type 1. A higher proportion of respondents with training type 1 compared with training types 2 and 3, noted the predominant use of face-face communication of clinical information. Most dermatology-trained dermatopathologists work in dermatology (single-specialty) groups with close proximity of pathology and clinical practices enabling face-face communication, in contrast to commercial labs that may be situated at a distance from the clinical practices they service with associated obstacles to effective clinician-pathologist communication. Despite several established benefits of computerized provider order entry, especially enhanced communication between clinicians and efficiency (13,14) reports of harm, abound (15, 16). Future studies on the ‘ideal’ RF should incorporate the unique clinical informational and decision making needs and existing cultural norms, with respect to the division of diagnostic decision-making responsibilities between clinicians and pathologists in the design of computerized provider order entry systems.

The main limitation of the explanatory sequence mixed methods study design is the extended time required to conduct a quantitative followed by a qualitative study. Respondent bias may result in over-representation of the opinions of those who feel most strongly about and/or who are most dissatisfied with clinician-pathologist communication in the skin biopsy care process, which may result in an overly negative view and tendency to offer perceived socially desirable responses and not necessarily what actually occurs in daily practice. Hence responses may not accurately reflect their experiences. Despite the good response rate for the survey with likely limited concerns for response bias, our results should be interpreted with caution for the following reasons: limited information on the characteristics of non-respondents, findings that may not reflect the perceptions of all pathologists, in all practice settings and limitations in drawing cause and effect relationships from survey studies. Additionally, bivariate tests of association are useful in exploratory analyses such as our study and assist with identifying potential associations between variables, however they do not address causation.

In conclusion, ASDP dermatopathologists expressed dissatisfaction with clinical communication in the skin biopsy care process and concerns about adverse impact on their diagnostic performance, efficiency and ultimately quality and safety of patient care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This publication was made possible by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. The Joint Commission Sentinel Event Data Unit. http://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/assets/4/6/CTH_Hand-off_commun_set_final_2010.pdf.

- 2.Hollensead SC, Lockwood WB, Elin RJ. Errors in pathology and laboratory medicine: consequences and prevention. J Surg Oncol. 2004;88:161–181. doi: 10.1002/jso.20125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith ML, Raab SS, Fernald DH. Evaluating the connections between primary care practice and clinical laboratory testing. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:120–125. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2011-0555-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graber ML. Next steps: envisioning a research agenda. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009;14(Suppl 1):107–12. doi: 10.1007/s10459-009-9183-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiff GD, Hasan O, Kim S, Abrams R, Cosby K, Lambert BL, et al. Diagnostic error in medicine: analysis of 583 physician-reported errors. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1881–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson AJ, Redbord K, Taylor JS, Shippy A, Kostecki J, Swerlick R. Medical error in dermatology practice: Development of a classification system to drive priority setting in patient safety efforts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(5):729–737. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comfere NI, Sokumbi O, Montori VM, LeBlanc A, Prokop LJ, Murad HM, Tilburt JC. Provider-to-Provider Communication in Dermatology and Implications of Missing Clinical Information in Skin Biopsy Requisition Forms: A Systematic Review. Int J Dermatol. 2014 May;53(5):549–57. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creswell JW. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerrity MS, DeVellis RF, Earp JA. Physicians’ reactions to uncertainty in patient care. Medical Care. 1990;28(8):724–736. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sellheyer K, Bergfeld WF. “Lesion,” “rule out..” and other vagaries of filling out pathology requisition forms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:914–915. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohr MR, Indika SH, Hood AF. The utility of clinical photographs in dermatopathologic diagnosis: a survey study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1307–1308. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez EM, Helm T, Ioffreda M, Helm KF. The vanishing biopsy: the trend toward smaller specimens. Cutis. 2005;76:335–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steele AM, DeBrow M. In: Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol 4: Technology and Medication Safety) Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, editors. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. Aug, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weir CR, Staggers N, Laukert T. Reviewing the impact of computerized provider order entry on clinical outcomes: The quality of systematic reviews. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81:219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in healthcare: the nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(2):104–112. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ammenwerth E, Schnell-Inderst P, Machan C, et al. The effect of electronic prescribing on medication errors and adverse drug events: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:585–600. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.