Abstract

Recently, the family Midichloriaceae has been described within the bacterial order Rickettsiales. It includes a variety of bacterial endosymbionts detected in different metazoan host species belonging to Placozoa, Cnidaria, Arthropoda and Vertebrata. Representatives of Midichloriaceae are also considered possible etiological agents of certain animal diseases. Midichloriaceae have been found also in protists like ciliates and amoebae. The present work describes a new bacterial endosymbiont, “Candidatus Fokinia solitaria”, retrieved from three different strains of a novel Paramecium species isolated from a wastewater treatment plant in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil). Symbionts were characterized through the full-cycle rRNA approach: SSU rRNA gene sequencing and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with three species-specific oligonucleotide probes. In electron micrographs, the tiny rod-shaped endosymbionts (1.2 x 0.25–0.35 μm in size) were not surrounded by a symbiontophorous vacuole and were located in the peripheral host cytoplasm, stratified in the host cortex in between the trichocysts or just below them. Frequently, they occurred inside autolysosomes. Phylogenetic analyses of Midichloriaceae apparently show different evolutionary pathways within the family. Some genera, such as “Ca. Midichloria” and “Ca. Lariskella”, have been retrieved frequently and independently in different hosts and environmental surveys. On the contrary, others, such as Lyticum, “Ca. Anadelfobacter”, “Ca. Defluviella” and the presently described “Ca. Fokinia solitaria”, have been found only occasionally and associated to specific host species. These last are the only representatives in their own branches thus far. Present data do not allow to infer whether these genera, which we named “stand-alone lineages”, are an indication of poorly sampled organisms, thus underrepresented in GenBank, or represent fast evolving, highly adapted evolutionary lineages.

Introduction

The order Rickettsiales belongs to the Alphaproteobacteria and exclusively comprises obligate intracellular bacteria including causative agents for serious human diseases, such as Rickettsia rickettsii (Rocky Mountain spotted fever), and Rickettsia prowazekii (epidemic typhus) [1–3]. For many years, it was mainly the pathogenicity of species such as Rickettsia, Anaplasma and Ehrlichia that stirred up the interest in this group. Later, the discovery of their close relationship to mitochondria fueled speculations on their phylogeny and evolution [4–6]. Studies on so-called “neglected Rickettsiaceae” or Rickettsia-like organisms (RLO) inhabiting non-haematophagous hosts opened further perspectives in this field, both from the evolutionary and ecological points of view [7–10]. Studying the biodiversity of Rickettsiales will not only provide missing links needed to resolve the intricate evolutionary patterns within Rickettsiales per se and enlighten their role as partners in numerous symbiotic systems, but also broaden our knowledge of host-symbiont interaction and its development during evolution.

At present the order Rickettsiales comprises the families [11]: i) Rickettsiaceae, with the genera Rickettsia, Orientia, Occidentia [12], “Candidatus (Ca.) Megaira” [10], “Ca. Cryptoprodotis” [8], “Ca. Arcanobacter” [13], “Ca. Trichorickettsia” and “Ca. Gigarickettsia” [14]; ii) Anaplasmataceae, with the genera Anaplasma, Wolbachia, Ehrlichia, Neorickettsia [15,16], Aegyptianella [17], “Ca. Neoehrlichia” [18], “Ca. Xenohaliotis” [19], and “Ca. Xenolissoclinum” [20]; and iii) the newly described “Ca. Midichloriaceae” (Midichloriaceae from now on). Recently, Midichloriaceae have been recognized as a clade or even a putative family by several authors [3,21–25] and finally received their formal family description by Montagna and colleagues [26]. The status of a fourth family, Holosporaceae, is presently debated. It fell at the base of Rickettsiales evolution in several phylogenetic trees based on SSU rRNA gene analyses (e.g. [25,27–30]), and even on concatenated protein coding genes [25]. However, other recent studies that consider LSU rRNA and/or different sets of protein coding genes seem to contradict this view, suggesting alternative placements of Holosporaceae within Alphaproteobacteria [11,31–33]. Whatever the position of Holosporaceae is, it does not affect the monophyletic evolutionary status of the three families Rickettsiaceae, Anaplasmataceae and Midichloriaceae, defined in all studies addressing their phylogeny (e.g. [11,26,30]). Therefore, Holosporaceae will not be discussed here.

The families of the order Rickettsiales show differences in their host range. Up to now, members of the Anaplasmataceae have been only detected in animals (Metazoa), thus suggesting a certain host specificity (reviewed in [16]). The family Rickettsiaceae was considered to inhabit only arthropods and vertebrates as alternating hosts. Rather unexpectedly, members of this family, including species showing no pathogenicity to vertebrates [7], have been recently detected in most eukaryotic super-groups as defined by Adl and colleagues [34]. Rickettsia-like endosymbionts occur in Opisthokonta, such as Metazoa (e.g. in leeches [35]) and Holomycota (e.g. Nuclearia [36]); in Archaeplastida, such as green algae [37–39] and higher plants [40]; in SAR (Stramenopiles, Alveolata, Rhizaria) host organisms, such as Alveolata, mainly ciliates [8,10,14] and Rhizaria [41]; in Excavata, such as euglenozoans [42,43]. In particular, “Ca. Megaira polyxenophila” shows an exceptionally broad host range inhabiting different ciliates [10,44,45], cnidarians [46,47] and green algae [37,39], indicating the possibility of horizontal transfer.

Similarly, the recently described family Midichloriaceae, with “Ca. Midichloria” as a type genus, revealed a striking biodiversity in the last years. Midichloriaceae as a whole show a wide host range. They can invade not only different arthropods including ticks, fleas, bed bugs, seed bugs and gadflies [21,48–51], but also other metazoan species such as Trichoplax adhaerens [25] and cnidarians [46,52]. Associations to fish [53,54] and mammals [55,56], including humans [24,51,57], were detected as well. Moreover, they have been found in Amoebozoa [58] and Ciliophora [22,59,60]. Indeed, they have been detected in organisms belonging to different eukaryotic super-groups (for review see [25,26]) but up to now, there are no records from Archaeplastida and Excavata.

Representative hosts of both, Rickettsiaceae and Midichloriaceae, are found at various trophic levels of the food chain, suggesting the theoretical possibility of horizontal transfer of the bacteria from one host to another by trophic interaction. Though not yet proven for all Rickettsiales, recent findings support the idea of possible host shifts in some Rickettsiaceae [9,10]. Data on recently described members of Midichloriaceae (i.e. “Ca. Defluviella procrastinata” in Paramecium nephridiatum and “Ca. Cyrtobacter zanobii” in Euplotes aediculatus) support the notion of the independent establishment of different symbiotic systems involving Midichloriaceae and ciliates during evolution [32,60,61]. Protists may have served as a source of infection for other organisms in aquatic environments, and may have facilitated the later transfer of Rickettsiaceae and Midichloriaceae to terrestrial habitats by arthropods. Taking into account the frequent occurrence of Midichloriaceae in haematophagous ticks [21,23,62–66] and bed bugs [50], it is only a little step up to the tick’s or bug’s victim, a potential vertebrate host. This putative course of host range expansion is presently supported by a growing evidence for potential infectivity of Midichloriaceae towards vertebrates [53,56,57]. Thus, studying this group may result in finding new potential pathogens of humans and economically important vertebrate species.

In the present study we provide an ultrastructural, molecular and phylogenetic description of a novel bacterial endosymbiont representing a new solitary branch within the Midichloriaceae family. It was recently discovered in a Paramecium species collected from a wastewater treatment plant in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil). According to the taxonomic rules for uncultivable bacteria [67], we propose to name the endosymbiont species “Ca. Fokinia solitaria”. New insights into the evolutionary pattern of Rickettsia-Like Organisms are also discussed.

Materials and Methods

Host isolation, cultivation and identification

The Paramecium strains Rio ETE_ALG 3VII, 3IX, 3X and 3XI were isolated from the wastewater treatment plant Estação de Tratamento de Esgoto Alegria (22°52'16"S 43°13'44"W, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) in February 2012. Sampling permission was provided by the State water and sewage company CEDAE (Companhia Estadual de Águas e Esgotos do Rio de Janeiro). Monoclonal cultures (strains) were established and maintained at 22 ± 1°C in 0.25% Cerophyl-medium inoculated with Enterobacter aerogenes [68]. According to morphological features [69] and eukaryotic SSU rRNA gene sequencing [70] the host was identified at genus level. As strain Rio ETE_ALG 3XI lost its endosymbionts after few generations of cultivation, bacterial SSU rRNA gene sequence and TEM observation were not obtained for this strain.

DNA extraction

Total DNA extraction was performed according to the following protocol: approximately 50 cells were washed by six successive transfers into sterile mineral water (Volvic®, Danone Waters, Paris, France); Paramecium cells were starved overnight in sterile Volvic water, washed again six times to minimize bacterial contamination and fixed in 70% ethanol. DNA was extracted applying the NucleoSpin® Plant DNA Extraction Kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Düren NRW, Germany), following the CTAB protocol for mycelium.

Molecular characterization

For the molecular characterization of the endosymbiont, bacterial SSU rRNA genes were amplified with the Alphaproteobacteria specific forward primer 16Sα_F19b 5'-CCTGGCTCAGAACGAACG-3' [71] and the universal bacterial reverse primer 16S_R1522a 5'- GGAGGTGATCCAGCCGCA -3' [71] using a touchdown PCR with annealing temperatures of 58°C (30 sec, 5 cycles), 54°C (30 sec, 10 cycles) and 50°C (30 sec, 25 cycles). The reaction was carried out in a C1000 Thermal cycler form Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA). The obtained PCR products were purified with the EuroGold CyclePure Kit (EuroClone S.p.A. Headquarters & Marketing, Pero Milano, Italy) and sequenced using the internal primers 16S F343 ND 5’-TACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’, 16S R515 ND 5’-ACCGCGGCTGCTGGCAC-3’ and 16S F785 ND 5’-GGATTAGATACCCTGGTA-3’ [71] at GATC Biotech AG (Konstanz, Germany).

Species-specific probe design

In order to verify that the sequenced bacterial SSU rRNA gene amplicon derived from the endosymbiont, three species-specific probes were designed: Fokinia_198 5'-CTTGTAGTGACATTGCTGC-3' (Alexa488-labeled, Tm = 54.5°C), Fokinia_434 5'-ATTATCATCCCTACCAAAAGAG-3' (Cy3-labeled, Tm = 54.7°C) and Fokinia_1250 5'-ACCCTGTTGCAGCCTTCT-3' (Cy3-labeled, Tm = 56.0°C). Tm was determined by Eurofins GMBH (Ebersberg, Germany) that synthetized the probes. FISH experiments using one of the species-specific probes in combination with the almost universal eubacterial probe EUB338 (either FITC- or Cy3-labeled [72]) were performed. The newly designed probes were tested at different formamide concentrations ranging from 0% up to 50%; their specificity was in silico determined using the TestProbe tool 3.0 (SILVA rRNA database project [73]) and the probe match tool of the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP [74]) allowing 0, 1 or 2 mismatches (Table 1). Finally, they have been uploaded to ProbeBase [75] and figshare (DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.2008524).

Table 1. In silico matching of the species-specific probes Fokinia_198, Fokinia_434 and Fokinia_1250 against bacterial SSU rRNA gene sequences available from RDP (release 11, update 4) and SILVA (release 123) databases.

Number of sequences in the corresponding database was 3,333,501 (RDP) or 1,756,783 (SILVA). “mism” stands for “mismatch(es)”. Reported are the number of sequences (“hits”) which theoretically hybridize with the probe allowing for the given number of mismatches.

| Species-specific probe | RDP | SILVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mism | 1 mism | 2 mism | 0 mism | 1 mism | 2 mism | |

| Fokinia_198 | 0 hits | 0 hits | 7 hits | 0 hits | 0 hits | 0 hits |

| Fokinia_434 | 0 hits | 84 hits | 1,540 hits | 0 hits | 18 hits | 437 hits |

| Fokinia_1250 | 0 hits | 0 hits | 13 hits | 0 hits | 0 hits | 4 hits |

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

FISH experiments were performed to detect the presence of endosymbiotic bacteria. At least 20 cells were washed three times in sterile Volvic and placed on SuperFrost Ultra Plus® slides (Gerhard Menzel GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany). Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA), dehydrated in an ethanol gradient and air-dried. Fixed cells were covered with hybridization buffer [76] containing recommended formamide concentration and 10 ng/μL of each probe. Slides were incubated overnight at 46°C in order to increase the accessibility of the bacterial SSU rRNA [77]. The next day, after washing for 20 min at 48°C, slides were air dried, mounted with CitiFluorTM AF1 (Citifluor Ltd, London, Great Britain) containing DAPI, and examined using the fluorescence microscope Nikon Eclipse Ti (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Alternatively, to reduce autofluorescence background signal, cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C in 2% PFA in depression slides, transferred to microscope slides and incubated again for 30 minutes at 4°C. The surplus liquid was removed. One drop of ice-cold 70% methanol was added, immediately removed and the slides were transferred into a washing chamber filled with 2x PBS at room temperature. Hybridization was performed applying 10 ng/μL of each probe in the hybridization buffer containing optimal formamide concentration (see results). The slides were incubated at 46°C in a humid chamber for 1.5–2 hours, followed by two washing steps in washing buffer [76] for 30 minutes at 48°C. During the whole procedure cells were prevented from drying. Finally, the cells were covered with Mowiol (Calbiochem®, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) containing PPD and DAPI according to manufacturer protocol. Images were obtained with a Leica TCS SPE confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany).

The used probes were EUB338 (5’-GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-3’, Cy3-labeled [72]), the Alphaproteobacteria-specific probe ALF1b (5’-CGTTCGYTCTGAGCCAG-3’, 6-FAM-labeled [76]) and the specifically designed ones.

Phylogenetic analysis

The obtained bacterial SSU rRNA gene sequence of “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” was aligned with the automatic aligner of the ARB software package version 5.2 [78] together with 22 closely related sequences of the Midichloriaceae family, 17 members of the Anaplasmataceae and Rickettsiaceae and 10 sequences representing the outgroup. The alignment was optimized manually especially focusing on the predicted base pairing of the stem regions, referring to the SSU rRNA structure of E. coli provided by ARB. The aligned sequences were then trimmed at both ends to the length of the shortest one; gaps were treated as missing data. The resulting alignment (S1 Alignment) contained 1,568 nucleotide columns that were used for phylogenetic inference. The optimal substitution model was selected with jModelTest 2.1 [79] according to the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). A maximum likelihood (ML) tree was calculated with 1,000 bootstrap pseudoreplicates using the PHYML software version 2.4.5 [80] from the ARB package. Bayesian inference (BI) was performed with MrBayes 3.2 [81], using three runs each with one cold and three heated Monte Carlo Markov chains, with a burn-in of 25%, iterating for 1,000,000 generations (obtained model parameters are shown in S1 Table). The runs were stopped after verifying the average standard deviation of the split frequencies had reached a value 0.01 or below. A similarity matrix [82] was built using the same 1,568 columns employed in phylogenetic reconstructions.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Ciliates were processed for electron microscopy as described elsewhere [59]. Briefly, the cells were fixed in a mixture of 1.6% PFA and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2–7.4) for 1.5 h at room temperature, washed in the same buffer containing sucrose (12.5%) and postfixed in 1.6% OsO4 (1 h at 4°C). Then the cells were dehydrated in an ethanol gradient followed by ethanol/acetone (1:1), 100% acetone, and embedded in Epoxy embedding medium (Fluka Chemie AG, St. Gallen, Switzerland). The resin was polymerized according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The blocks were sectioned with a Leica EM UC6 Ultracut. Sections were stained with aqueous 1% uranyl acetate followed by 1% lead citrate.

Negative staining was performed by first washing and starving the cells overnight in distilled water to decrease the abundance of food and environmental bacteria. Single cells were then squashed with the micropipette and the remaining were transferred onto grids covered with the supporting film. Staining was performed using aqueous 1% uranyl acetate. All samples were examined with a JEOL JEM-1400 (JEOL, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) electron microscope at 90 kV. The images were obtained with an inbuilt digital camera.

Nucleotide sequence accession number

The sequence obtained from bacterial SSU rRNA gene of the endosymbiont of Paramecium clone Rio ETE_ALG 3VII was submitted to the GenBank database (NCBI) under the accession number KM497527 (1,473 bp).

Results

Characterization of the host

The Paramecium strains isolated from the wastewater samples were submitted to morphological analyses. General morphological features like size, body shape and location of the cytoproct were typical for the Paramecium caudatum-aurelia clade. However, species identification proved to be equivocal, suggesting the possibility that we were dealing with a new species. A detailed description of the host including morphometric, ultrastructural, and molecular characterization will be provided in a separate publication.

Molecular characterization of endosymbiont

Nearly full-length bacterial SSU rRNA gene sequences were obtained for the three strains Rio ETE_ALG 3VII, 3IX and 3X. The sequences were identical, hence, strain Rio ETE_ALG 3VII was used representatively for all three strains (Rio ETE_ALG 3VII: 1,473 bp, GenBank accession: KM497527). NCBI Blastn results against nucleotide collection (nr/nt) showed the highest identity (88.5% and 87.0%, respectively) with an uncultured bacterium from a lake in New York (accession number FJ437943) and “Ca. Defluviella procrastinata”, symbiont of Paramecium nephridiatum. It is noteworthy that, compared to the other Midichloriaceae included in the analysis, the SSU rRNA gene sequences of both “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” and “Ca. Defluviella procrastinata” had four small insertions (2–13 nucleotides long) in the same positions (76, 94, 200, 216, according to the E. coli SSU rRNA gene reference numbering). These insertions were paired two by two in the predicted rRNA structure, increasing the length of two stems in regions V1 and V2 respectively. Other two small insertions (4 and 5 nucleotides long, at positions 452 and 476, respectively) were present in “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” only, which were predicted to increase the length of a third stem in region V3 of the rRNA molecule.

FISH experiments

In preliminary FISH experiments, positive signals with both probes (EUB338 and Alf1b) were observed in the cytoplasm of all Paramecium strains. Overlapping signals of both probes indicated the presence of endosymbiotic bacteria belonging to Alphaproteobacteria in the cell cortex. Bacteria localized in digestive vacuoles (food bacteria) showed positive signals only with probe EUB338.

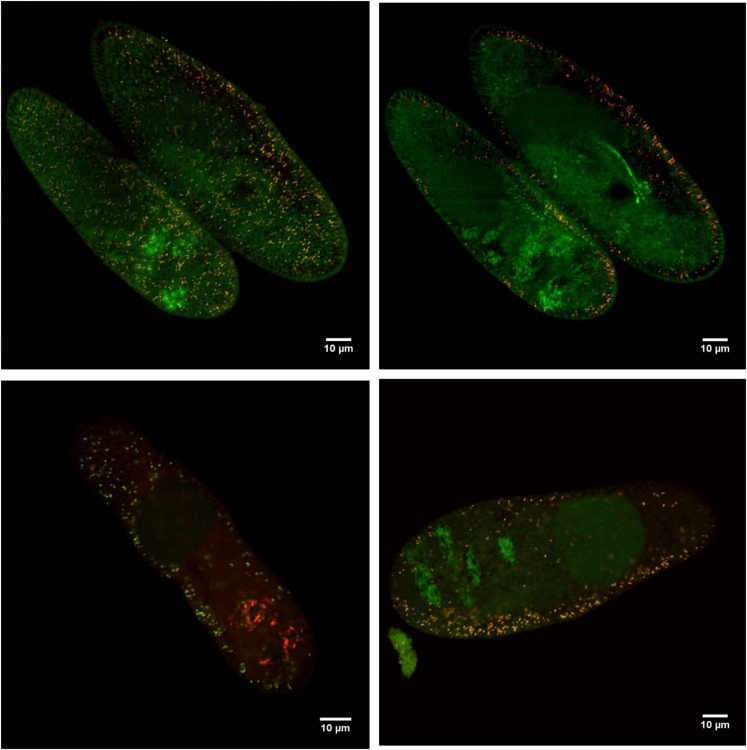

The designed species-specific probes Fokinia_198, Fokinia_434, and Fokinia_1250 were specifically designed to have a similar and low Tm that should have guaranteed good specificity without formamide or with low formamide concentrations. Hybridization experiments with their target organism in a formamide range from 0 to 30%, confirmed the signal intensity was best between 0–15% formamide (Fig 1). Specificity of probes was tested in silico against available bacterial SSU rRNA gene sequences (Table 1). The probes Fokinia_198 and Fokinia_1250 showed high specificity even when mismatches were allowed. Probe Fokinia_434, on the other hand, recognized 84 non-target sequences when one mismatch was allowed (Table 1). Experiments with one species-specific probe and either EUB338 or Alf1b clearly showed that “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” is the only symbiont residing in the cytoplasm (outside the food-vacuoles) of these host strains (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Species-specific in situ detection of “Candidatus Fokinia solitaria” in Paramecium sp. strain Rio ETE ALG 3VII at 15% formamide concentration.

Merge of the signals from probes EUB338 (fluorescein-labelled, green signal) and A) species-specific probe Fokinia_434 (Cy3-labelled, red signal), B) alphaproteobacterial probe ALF1b (Cy3), C) species-specific probe Fokinia_198 (labelled with Alexa488, green signal), or D) species-specific probe Fokinia_1250 (Cy3). Stratification of the endosymbiont in section through the host cortex (A, C) and through the inner part of the host cell (B, D). “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” appears yellowish. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Phylogenetic analysis

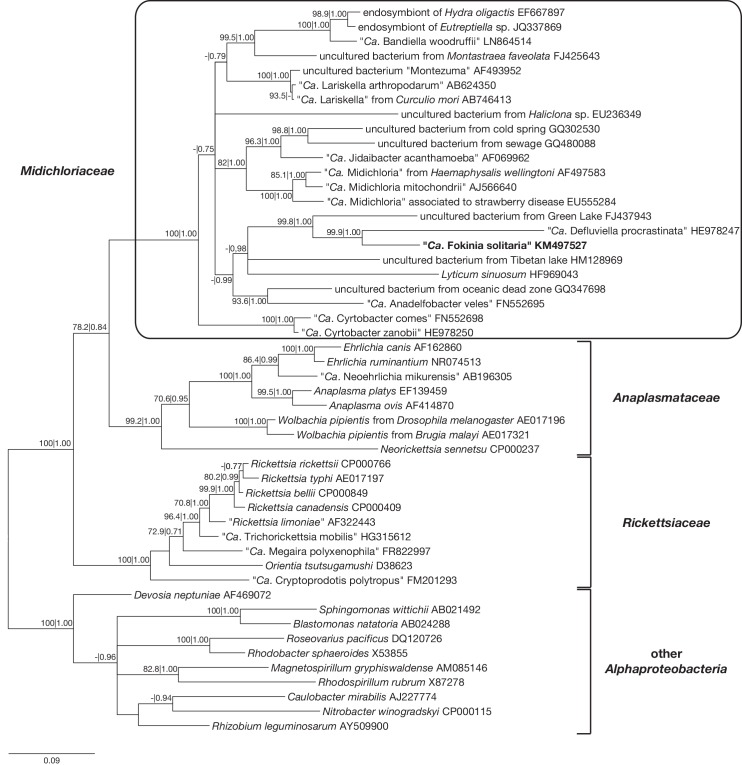

After the choice of the GTR+I+G substitution model with jModelTest, the ML and BI trees were estimated (Fig 2). The monophyly of the three families Rickettsiaceae, Anaplasmataceae and Midichloriaceae was confirmed with both inference methods, which joined Midichloriaceae and Anaplasmataceae as the sister group to Rickettsiaceae, with bootstrap value 78.2% for ML and posterior probability value 0.80 for BI. Additionally, in both trees several sequences within the Midichloriaceae formed well-supported monophyletic clades, like the genera “Ca. Midichloria” and “Ca. Lariskella”. However, most of the ancient relationships within this family showed comparatively little support and appeared still unresolved, which is in good agreement with literature (e.g. [59,60]). Only the position of “Ca. Cyrtobacter” as sister group to all other Midichloriaceae was obtained with high support with both inference methods (100% ML; 1.00 BI).

Fig 2. Bayesian inference phylogenetic tree built with MrBayes employing the GTR + I + G model.

Numbers indicate bootstrap values inferred after 1,000 pseudoreplicates for maximum likelihood and Bayesian posterior probabilities (values below 70.0% and 0.7 are not shown). The sequence characterized in the present work is reported in bold. Scale bar: 9 nucleotide substitutions per 100 positions. “Ca.” stands for “Candidatus”.

The sequence of “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” from Paramecium strain Rio ETE_ALG 3VII affiliated to Midichloriaceae and was strongly associated (99.9% ML; 1.00 BI) to “Ca. Defluviella procrastinata” endosymbiont of P. nephridiatum (Fig 2), while the identity among them was only 87.0%. The two sequences together were grouped with high support (99.8% ML; 1.00 BI) to the previously mentioned uncultured bacterium from a freshwater lake in New York (FJ437943), which had 88.5% and 84.9% identity with “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” and “Ca. Defluviella procrastinata”, respectively. The branches leading to the three sequences were long compared to the other Midichloriaceae in the obtained phylogenetic tree. Further groupings of the three sequences with the genus Lyticum, “Ca. Anadelfobacter veles” and other uncultured bacteria were not supported statistically.

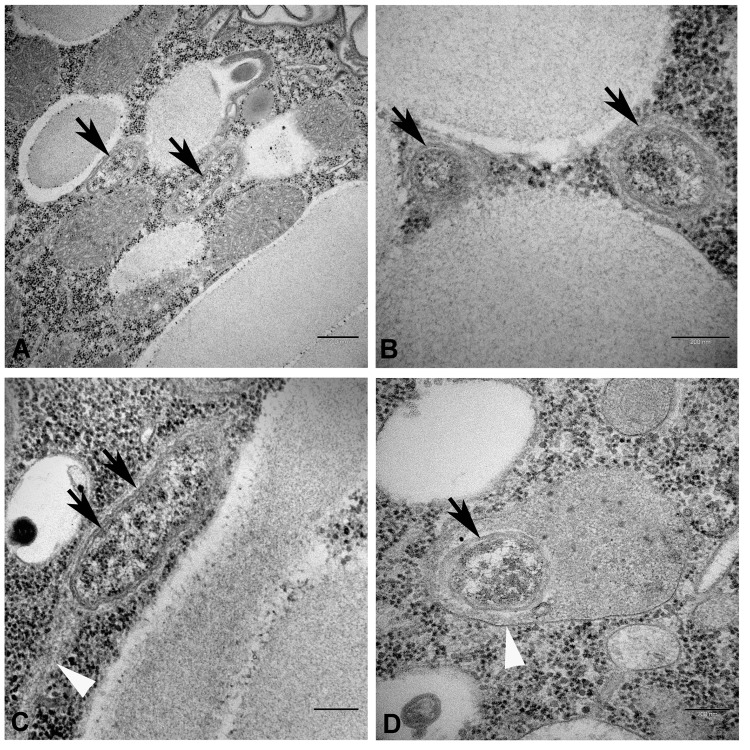

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

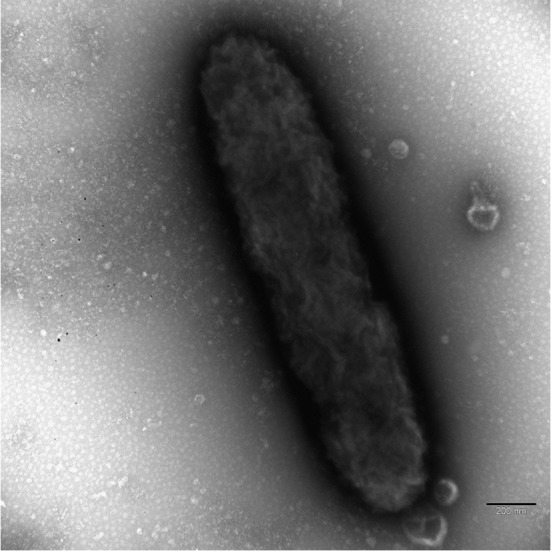

The endosymbionts were located in the host cortex, stratified in a narrow layer in between the trichocysts or just below them (Fig 3A and 3B). Most often, they were oriented parallel to the trichocysts axis and perpendicular to the plasma membrane. In ultrathin sections, endosymbionts appeared as tiny rods, 1.2 μm long and 0.25–0.35 μm wide. They showed a distinct double membrane characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria (Fig 3C). The bacteria never formed clusters and lay naked in the host cytoplasm. Occasionally, dividing forms could be found. No flagella were detected. However, in cross sections bacteria were surrounded by a narrow rim lacking host ribosomes and containing fine fibrils, while in some longitudinal sections, there seemed to be a “tail” of the same material trailing after the endosymbiont (Fig 3C, white arrowhead). However, negative staining demonstrated the absence of flagella (Fig 4). Bacterial ribosomes and nucleoid were quite conspicuous in the bacterial cytoplasm, but other inclusions were rarely observed. The cytoplasm of the infected ciliates was abundant in autolysosomes, most often containing mitochondria; the endosymbionts could be also quite frequently enclosed in autolysosomes (Fig 3D, white arrowhead), sometimes together with mitochondria (not shown).

Fig 3. Transmission electron microscopy images of ‘‘Candidatus Fokinia solitaria” in longitudinal (A, C) and transverse (B, D) sections.

Black arrows point at the bacterial membranes; white arrowheads indicate fibrillar material associated to the endosymbiont (C) and host autolysosome containing the endosymbiont (D). Scale bars: 0.5 μm (A) and 0.2 μm (B, C, D).

Fig 4. Negative staining of “Candidatus Fokinia solitaria”.

No flagella are visible. Scale bar: 0.2 μm.

Discussion

After the description of “Ca. M. mitochondrii” had been published in 2006, the number of species and sequences closely related to “Ca. M. mitochondrii” and other members of the family increased remarkably. During the last years, several new genera were discovered and our knowledge of the family Midichloriaceae took shape step by step. With the present species description of “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” we add a new piece to the puzzle of Midichloriaceae.

The families Midichloriaceae, Anaplasmataceae and Rickettsiaceae represent monophyletic clades with high support values (Fig 2). The obtained tree topologies based on bacterial SSU rRNA gene sequences associating Midichloriaceae to Anaplasmataceae is coherent with all previously published SSU rRNA phylogenies [21,22,25,32,59,60,83,84], except one [51]. Two genome based studies [25,85] showed a closer relationship between Midichloriaceae and Rickettsiaceae. On the contrary, other recent publications using different sets of species and genes placed Midichloriaceae as sister to Anaplasmataceae, although with limited support, in agreement with most SSU rRNA trees [32,86]. Further genomic data will be necessary to unambiguously establish evolutionary association among the three families.

The phylogenetic analyses of our data indicated a close association of “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” to two different sequences forming a highly supported (99.8% ML; 1.00 BI) monophyletic branch. One of the sequences derives from an uncultured bacterium of a freshwater lake in New York (unpublished; accession number FJ437943), the other one belongs to “Ca. Defluviella procrastinata”, an endosymbiotic bacterium inhabiting P. nephridiatum [60]. Their phylogenetic proximity suggests that these three species might have derived from a common ancestor. Additionally, the occurrence of similar insertions in the SSU rRNA genes of “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” and “Ca. Defluviella procrastinata”, supports this presumption and suggests that this feature could be a shared derived character of the two genera. The sequence FJ437943 does not share any of the insertions and therefore seems to retain the ancient condition. Nevertheless, as the identity values among the three sequences (84.9–88.5%) are far below the taxonomic threshold for discriminating bacterial genera (sequence similarity of 94.5% or lower, according to [87]), the three sequences belong to different genera. Taking into account their highly supported phylogenetic association, the low sequence identities and the long terminal branches in the phylogenetic analysis, these species appear to be fast evolving.

Up to now, some representatives of Midichloriaceae, such as genera “Ca. Midichloria”, “Ca. Lariskella” and “Ca. Bandiella”, have been observed in a great variety of host species and with a worldwide distribution [21,23,64–66,88–91]. Such host species occur both in aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Most likely, the ancestral host species was an aquatic organism indicating at least one event of adaptation to terrestrial animals [61]. Due to the unresolved phylogenetic relationships between the genera of Midichloriaceae it is not clear, when and how many times the adaptation to terrestrial animals took place (compare Fig 2 of this work with Fig 4 of [61]). Nevertheless, infection experiments on “Candidatus Jidaibacter acanthamoeba” and “Candidatus Bandiella woodruffii” proved the possibility of horizontal transfer among aquatic organisms [32,89]. In contrast to these genera, others seem to be represented by few isolates appearing as “stand-alone” branches in the phylogeny of Midichloriaceae, not only as “Ca. Fokinia”, but also the recently redescribed genus Lyticum [59,92–94] as well as “Ca. Defluviella” [60] and “Ca. Anadelfobacter” [22]. Presently noted “stand-alone” genera of Midichloriaceae could be either an indication of poorly sampled organisms, thus underrepresented in GenBank, or fast evolving, highly specialized, real “stand-alone” evolutionary lineages.

Overall, the family Midichloriaceae seems to consist of different clades with members showing different evolutionary strategies: widespread and adaptable endosymbiotic bacteria (“Ca. Midichloria”, “Ca. Lariskella”, and “Ca. Bandiella”) on one hand, and fast evolving “stand-alone” symbionts, such as Lyticum, “Ca. Defluviella”, “Ca. Anadelfobacter” and “Ca. Fokinia”, on the other hand. To refer to the characteristic of “Ca. Fokinia”, represented by an isolated branch, and in accordance with the guidelines of the International Committee of Systematic Bacteriology [67], we propose the name “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” in honor to our appreciated colleague Professor Sergei I. Fokin, a prominent specialist in the study of bacterial symbionts of ciliates.

All so far discovered Midichloriaceae-endosymbionts of ciliates are rod-shaped but differ significantly in their size, “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” being one of the smallest. There are also remarkable differences in the intracellular localization of the endosymbionts. “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” and “Ca. Cyrtobacter comes” [22] are not surrounded by a host membrane and lie naked in the host cytoplasm, whereas both Lyticum species and “Ca. Anadelfobacter veles” reside in host vesicles [22,59]. Only “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” shows a defined distribution, stratified in a narrow layer in the host cortex. This area is known to be devoid of acid phosphatase (AcPase) activity, indicating the absence of lysosomes and autophagosomes [95,96]. The special localization of endosymbionts between the host trichocysts could be favorable for “Ca. Fokinia solitaria”, permitting it to avoid the host defense mechanisms, especially because it is not surrounded by a protective symbiont-containing vacuole. The occurrence of “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” in autolysosomes in the inner parts of the cytoplasm seems to support this view. Autophagy is not only a process of degrading macromolecules or organelles to provide nutrition during starvation periods; it is also involved in other biological processes like development and differentiation, cell death as well as immune system and protection against pathogens [97–99]. In mammalian cells, autophagy defends the host cells against pathogenic microbes (xenophagy [100]) like viruses [101], bacteria [102–104] and pathogenic protists [105]. Hence, the loss of “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” in one of the sampled Paramecium strains may be the result of xenophagy and implies that the endosymbiont is not necessary for the host species and is treated as a pathogen. On the other hand, several pathogens were found to be able to avoid, subvert or even utilize the hosts autophagic machinery for replication [106,107] and egress from the host cell [108].

TEM observation of “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” gave no evidence for the existence of flagella (Fig 4) but the occurrence of a narrow rim lacking host ribosomes and containing fine fibrillar material was detected (Fig 3C) and a tail-like structure possibly made out of fibrils has been found in some longitudinal sections. These observations and the distinct distribution of “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” inside the host cell indicate the possibility that the bacteria are able to move inside the host cytoplasm, probably by using host actin for the movement [109–112].

The microbial community of wastewater and activated sludge is highly diverse. Due to the enriched abundance of organic matter, wastewater is a perfect milieu for growth of non-pathogenic and pathogenic bacteria and the close association between many different bacteria species increases the development and distribution of virulence and resistance factors (for review see [113]). After passing several steps of clarifying and removing contaminants, the remaining sewage is released into the environment still containing several pathogens [113–115]. Therefore, ciliates play a necessary role in the purification of sewage by supporting the flocculation process [116] and more importantly, as bacterivorous organisms they regulate bacterial biomass and the occurrence of pathogenic bacteria [117,118]. During the process of feeding, they run the risk of being colonized by bacteria [95,119]. Thus, the probability of being infected by potential human or animal pathogens is high in a habitat bearing many different bacteria. Hence, ciliates could play a role as reservoir for pathogens [44] especially in environments like wastewater. Indeed, in some cases, protists have been found to harbor pathogenic bacteria [120–122]. Other potentially pathogenic bacteria have been found in amoeba and ciliates as well [123,124]. “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” was found in a Paramecium species isolated from a wastewater treatment plant in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Up to now, only two other records of bacteria inhabiting ciliates deriving from wastewater are available [60,125], suggesting that the role of ciliates as reservoir for potentially pathogenic bacteria in wastewater may have been overlooked.

A big diversity of Rickettsiales not associated with pathogenicity for vertebrates emerged recently [7]. In almost five years of intensive environmental screening for endosymbiotic bacteria in ciliates, eight new species of Midichloriaceae corresponding to six new genera have been described, or respectively molecularly characterized for the first time, in ciliate model organisms Paramecium and Euplotes, i.e. “Ca. Defluviella procrastinata”, “Ca. Cyrtobacter comes” and “Ca. C. zanobii”, “Ca. Anadelfobacter veles” [22,60], Lyticum sinuosum and L. flagellatum [59], “Ca. Bandiella wodruffii” [89], and this new one, “Ca. Fokinia solitaria”. This high rate of new species descriptions indicates a general high abundance of different Midichloriaceae species in ciliates and, possibly, in protists. It seems very likely that more descriptions of new Midichloriaceae will follow providing us a better understanding of their phylogenetic relationships and host-endosymbiont interactions.

Description of “Candidatus Fokinia solitaria”

“Candidatus Fokinia solitaria” (Fo.kiˈni.a so.li. taˈri.a; N.L. fem. n. Fokinia, in honor of Professor Sergei I. Fokin; N.L. adj. solitarius, solitary, lonely). Short rod-like bacterium (1.2 x 0.25–0.35 μm in size). Cytoplasmic endosymbiont of the ciliate Paramecium sp. strain Rio ETE_ALG 3VII (Oligohymenophorea, Ciliophora). Basis of assignment: SSU rRNA gene sequence (accession number: KM497527) and positive match with the specific FISH oligonucleotide probes Fokinia_198 (5'-CTTGTAGTGACATTGCTGC-3'), Fokinia_434 (5'-ATTATCATCCCTACCAAAAGAG-3') and Fokinia_1250 (5'-ACCCTGTTGCAGCCTTCT-3'). Belongs to Midichloriaceae family in the order Rickettsiales (Alphaproteobacteria). Identified in Paramecium sp. strain Rio ETE_ALG 3VII isolated from a wastewater treatment plant in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil). Uncultured thus far.

Supporting Information

22 closely related sequences of the Midichloriaceae family, 17 members of the Anaplasmataceae and Rickettsiaceae and 10 other Alphaproteobacteria representing the outgroup were aligned with “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” to perform phylogenetic analyses. The alignment was trimmed at both ends to reach the length of the shortest sequence on each side, the resulting 1,568 nucleotide columns are presented here.

(S1_ALIGNMENT)

The parameters are given as total tree length (TL), reversible substitution rates (r(A<->C), r(A<->G), etc), stationary state frequencies of the four bases (pi(A), pi(C), etc), the shape of the gamma distribution of rate variation across sites (alpha), and the proportion of invariable sites (pinvar). The estimated sampling size (ESS) is shown as minimal (minESS) and average (avgESS) values. PSRF stands for potential scale reduction factor.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

Studies were partly performed using the equipment of the Core Facility Centers for Microscopy and Microanalysis and for Molecular and Cell Technologies of St.-Petersburg State University. Thanks are due to Konstantin Benken for his help with CLSM, Eike Dusi for constructive discussions and Simone Gabrielli for his technical assistance in photographic artwork. We would like to thank also the two anonymous referees, who helped to improve the manuscript with their helpful and constructive comments.

Data Availability

The SSU rRNA gene sequence of "Ca. Fokinia solitaria" is available on GenBank database (NCBI) (accession number: KM497527). Species specific oligonucleotide probes were uploaded on probeBase and Figshare (DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.2008524).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by: European Commission FP7-PEOPLE-2009-IRSES project CINAR PATHOBACTER (247658): mobility support to GP ES FS MS SK; European Commission FP7-PEOPLE-2011-IRSES project CARBALA (295176): mobility support to ES; COST action BM1102: mobility support to FS; PRIN fellowship (protocol 2012A4F828_002) from the Italian Research Ministry (MIUR) to GP, Volkswagen foundation (project number 84816) to MS, RFFI grant number 15-04-06410 and the SPbU grant 1.42.1454.2015 to ES: general research costs. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Walker DH, Ismail N. Emerging and re-emerging rickettsioses: endothelial cell infection and early disease events. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008:6: 375–386. 10.1038/nrmicro1866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McQuiston JH, Paddock CD. Public health: Rickettsial infections and epidemiology In: Palmer GH, Azad AF, editors. Intracellular pathogens II Rickettiales. Washington: ASM Press; 2012. pp. 40–83. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillespie JJ, Nordberg EK, Azad AF, Sobral BWS. Phylogeny and comparative genomics: The shifting landscape in the genomics era In: Palmer GH, Azad AF, editors. Intracellular pathogens II Rickettiales. Washington: ASM Press; 2012. pp. 84–141. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson SGE, Zomorodipour A, Andersson JO, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Alsmark UCM, Podowski RM, et al. The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature. 1998:396: 133–140. 10.1038/24094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray MW, Burger G, Lang BF. The origin and early evolution of mitochondria. Genome Biol. 2001:2: 1018.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emelyanov VV. Rickettsiaceae, Rickettsia-like endosymbionts, and the origin of mitochondria. Bioscience Rep. 2001:21: 1–17. 10.1023/A:1010409415723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perlman SJ, Hunter MS, Zchori-Fein E. The emerging diversity of Rickettsia. Proc R Soc B. 2006:273: 2097–2106. 10.1098/rspb.2006.3541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrantini F, Fokin SI, Modeo L, Andreoli I, Dini F, Görtz HD, et al. ‘‘Candidatus Cryptoprodotis polytropus,” a novel Rickettsia-like organism in the ciliated protist Pseudomicrothorax dubius (Ciliophora, Nassophorea). J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2009:56: 119–129. 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00377.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinert LA, Werren JH, Aebi A, Stone GN, Jiggins FM. Evolution and diversity of Rickettsia bacteria. BMC Biol. 2009:7: 6 10.1186/1741-7007-7-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schrallhammer M, Ferrantini F, Vannini C, Galati S, Schweikert M, Görtz HD, et al. ‘Candidatus Megaira polyxenophila’ gen. nov., sp. nov.: Considerations on evolutionary history, host range and shift of early divergent Rickettsiae. PLoS ONE. 2013:8: e72581 10.1371/journal.pone.0072581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferla MP, Thrash JC, Giovannoni SJ, Patrick WM. New rRNA gene-based phylogenies of the Alphaproteobacteria provide perspective on major groups, mitochondrial ancestry and phylogenetic instability. PLoS ONE. 2013:8: e83383 10.1371/journal.pone.0083383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mediannikov O, Nguyen T-T, Bell-Sakyi L, Padmanabhan R, Fournier P-E, Raoult D. High quality draft genome sequence and description of Occidentia massiliensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the family Rickettsiaceae. Stand Genomic Sci. 2014:9: 9 10.1186/1944-3277-9-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martijn J, Schulz F, Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, Viklund J, Stepanauskas R, Andersson SGE, et al. Single-cell genomics of a rare environmental alphaproteobacterium provides unique insights into Rickettsiaceae evolution. ISME J. 2015:9: 2373–2385. 10.1038/ismej.2015.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vannini C, Boscaro V, Ferrantini F, Benken KA, Mironov TI, Schweikert M, et al. Flagellar movement in two bacteria of the family Rickettsiaceae: A re-evaluation of motility in an evolutionary perspective. PLoS ONE 2014:9: e87718 10.1371/journal.pone.0087718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumler JS, Barbet AF, Bekker CPJ, Dasch GA, Palmer GH, Ray SC, et al. Reorganization of genera in the families Rickettsiaceae and Anaplasmataceae in the order Rickettsiales: unification of some species of Ehrlichia with Anaplasma, Cowdria with Ehrlichia and Ehrlichia with Neorickettsia, descriptions of six new species combinations and designation of Ehrlichia equi and ‘HGE agent’ as subjective synonyms of Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Int J Syst Evol Micr. 2001:51: 2145–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rikihisa Y. Mechanisms to create a safe haven by members of the family Anaplasmataceae In: Hechemy KE, AvsicZupanc T, Childs JE, Raoult DA, editors. Rickettsiology: Present and Future Direction. New York: Ann NY Acad Sci; 2003. pp. 548–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rikihisa Y, Zhang C, Christensen BM. Molecular characterization of Aegyptianella pullorum (Rickettsiales, Anaplasmataceae). J Clin Microbiol. 2003:41: 5294–5297. 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5294-5297.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawahara M, Rikihisa Y, Isogai E, Takahashi M, Misumi H, Suto C, et al. Ultrastructure and phylogenetic analysis of ‘Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis’ in the family Anaplasmataceae, isolated from wild rats and found in Ixodes ovatus ticks. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004:54: 1837–1843. 10.1099/ijs.0.63260-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman CS, Andree KB, Beauchamp KA, Moore JD, Robbins TT, Shields JD, et al. ‘Candidatus Xenohaliotis californiensis‘, a newly described pathogen of abalone, Haliotis spp., along the west coast of North America. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000:50: 847–855. 10.1099/00207713-50-2-847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwan JC, Schmidt EW. Bacterial endosymbiosis in a chordate host: long-term co-evolution and conservation of secondary metabolism. PLoS ONE. 2013: e80822 10.1371/journal.pone.0080822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epis S, Sassera D, Beninati T, Lo N, Beati L, Piesman J, et al. Midichloria mitochondrii is widespread in hard ticks (Ixodidae) and resides in the mitochondria of phylogenetically diverse species. Parasitology. 2008:135: 485–494. 10.1017/S0031182007004052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vannini C, Ferrantini F, Schleifer KH, Ludwig W, Verni F, Petroni G. “Candidatus Anadelfobacter veles” and “Candidatus Cyrtobacter comes,” two new Rickettsiales species hosted by the protist ciliate Euplotes harpa (Ciliophora, Spirotrichea). Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010:76: 4047–4054. 10.1128/AEM.03105-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams-Newkirk AJ, Rowe LA, Mixson-Hayden TR, Dasch GA. Presence, genetic variability, and potential significance of ‘‘Candidatus Midichloria mitochondrii” in the lone star tick Amblyomma americanum. Exp Appl Acarol. 2012:58: 291–300. 10.1007/s10493-012-9582-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mariconti M, Epis S, Gaibani P, Dalla Valle C, Sassera D, Tomao P, et al. Humans parasitized by the hard tick Ixodes ricinus are seropositive to Midichloria mitochondrii: is Midichloria a novel pathogen, or just a marker of tick bite? Pathog Glob Health. 2012:106: 391–396. 10.1179/2047773212Y.0000000050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Driscoll T, Gillespie JJ, Nordberg EK, Azad AF, Sobral BW. Bacterial DNA sifted from the Trichoplax adhaerens (Animalia: Placozoa) genome project reveals a putative rickettsial endosymbiont. Genome Biol Evol. 2013:5: 621–645. 10.1093/gbe/evt036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montagna M, Sassera D, Epis S, Bazzocchi C, Vannini C, Lo N, et al. “Candidatus Midichloriaceae” fam. nov. (Rickettsiales), an ecologically widespread clade of intracellular Alphaproteobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013:79: 3241–3248. 10.1128/AEM.03971-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amann R, Springer N, Ludwig W, Görtz H-D, Schleifer K-H. Identification in situ and phylogeny of uncultured bacterial endosymbionts. Nature. 1991:351: 161–164. 10.1038/351161a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Springer N, Ludwig W, Amann R, Schmidt HJ, Görtz H-D, Schleifer K-H. Occurrence of fragmented 16S rRNA in an obligate bacterial endosymbiont of Paramecium caudatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993:90: 9892–9895. 10.1073/pnas.90.21.9892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eschbach E, Pfannkuchen M, Schweikert M, Drutschmann D, Brümmer F, Fokin SI, et al. ‘‘Candidatus Paraholospora nucleivisitans”,an intracellular bacterium in Paramecium sexaurelia shuttles between the cytoplasm and the nucleus of its host. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2009:32: 490–500. 10.1016/j.syapm.2009.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boscaro V, Fokin SI, Schrallhammer M, Schweikert M, Petroni G. Revised systematics of Holospora-like bacteria and characterization of “Candidatus Gortzia infectiva”, a novel macronuclear symbiont of Paramecium jenningsi. Microbial Ecol. 2013:65: 255–267. 10.1007/s00248-012-0110-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Georgiades K, Madoui M-A, Le P, Robert C, Raoult D. Phylogenomic analysis of Odyssella thessalonicensis fortifies the common origin of Rickettsiales, Pelagibacter ubique and Reclimonas americana mitochondrion. PLoS ONE. 2011:5: e24857 10.1371/journal.pone.0024857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulz F, Martijn J, Wascher F, Lagkouvardos I, Kostanjšek R, Ettema TJG, et al. A Rickettsiales symbiont of amoebae with ancient features. Environ Microbiol. In press. 10.1111/1462-2920.12881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Z, Wu M. Complete genome sequence of the endosymbiont of Acanthamoeba strain UWC8, an Amoeba endosymbiont belonging to the “Candidatus Midichloriaceae” family in Rickettsiales. Genome Announc. 2014:2: e00791–14. 10.1128/genomeA.00791-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adl SM, Simpson AGB, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Bass D, Bowser SS, et al. The revised classification of eukaryotes. J Euk Microbiol. 2012:59: 429–514. 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kikuchi Y, Sameshima S, Kitade O, Kojima J, Fukatsu T. Novel clade of Rickettsia spp. from leeches. Appl Environ Microb. 2002:68: 999–1004. 10.1128/AEM.68.2.999-1004.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyková I, Veverkova M, Fiala I, Macháčková B, Pecková H. Nuclearia pattersoni sp. n. (Filosea), a new species of amphizoic amoeba isolated from gills of roach (Rutilus rutilus), and its rickettsial endosymbiont. Folia Parasit. 2003:50: 161–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawafune K, Hongoh Y, Hamaji T, Nozaki H. Molecular identification of rickettsial endosymbionts in the non-phagotrophic volvocalean green algae. PLoS ONE 2012:7: e31749 10.1371/journal.pone.0031749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hollants J, Leliaert F, Verbruggen H, Willems A, De Clerck O. Permanent residents or temporary lodgers: characterizing intracellular bacterial communities in the siphonous green alga Bryopsis. Proc R Soc Lond. 2013:280: 20122659 10.1098/rspb.2012.2659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawafune K, Hongoh Y, Nozaki H. A rickettsial endosymbiont inhabiting the cytoplasm of Volvox carteri (Volvocales, Chlorophyceae). Phycologia. 2014:53: 95–99. 10.2216/13-193.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis MJ, Ying Z, Brunner BR, Pantoja A, Ferwerda FH. Rickettsial relative associated with papaya bunchy top disease. Curr Microbiol. 1998:36: 80–84. 10.1007/s002849900283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hine PM, Wakefield S, Diggles BK, Webb VL, Maas EW. Ultrastructure of a haplosporidian containing Rickettsiae, associated with mortalities among cultured paua Haliotis iris. Dis Aquat Organ. 2002:49: 207–219. 10.3354/dao049207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim E, Park JS, Simpson AGB, Matsunaga S, Watanabe M, Murakami A, et al. Complex array of endobionts in Petalomonas sphagnophila, a large heterotrophic euglenid protist from Sphagnum-dominated peatlands. ISME J. 2010:4: 1108–1120. 10.1038/ismej.2010.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuo RC, Lin S. Ectobiotic and endobiotic bacteria associated with Eutreptiella sp. isolated from Long Island Sound. Protist. 2013:164: 60–74. 10.1016/j.protis.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vannini C, Petroni G, Verni F, Rosati G. A bacterium belonging to the Rickettsiaceae family inhabits the cytoplasm of the marine ciliate Diophrys appendiculata (Ciliophora, Hypotrichia). Microbial Ecol. 2005:49: 434–442. 10.1007/s00248-004-0055-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun HY, Noe J, Barber J, Coyne RS, Cassidy-Hanley D, Clark TG, et al. Endosymbiotic bacteria in the parasitic ciliate Ichthyophthirius multifiliis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009:75: 7445–7452. 10.1128/AEM.00850-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fraune S, Bosch TCG. Long-term maintenance of species-specific bacterial microbiota in the basal metazoan Hydra. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007:104: 13146–12151. 10.1073/pnas.0703375104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sunagawa S, DeSantis TZ, Piceno YM, Brodie EL, DeSalvo MK, Voolstra CR, et al. Bacterial diversity and White Plague Disease-associated community changes in the Caribbean coral Montastraea faveolata. ISME J. 2009:3: 512–521. 10.1038/ismej.2008.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hornok S, Földvári G, Elek V, Naranjo V, Farkas R, de la Fuente J. Molecular identification of Anaplasma marginale and rickettsial endosymbionts in blood-sucking flies (Diptera: Tabanidae, Muscidae) and hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). Vet Parasitol. 2008:154: 354–359. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Erickson DL, Anderson NE, Cromar LM, Jolley A. Bacterial communities associated with flea vectors of plague. J Med Entomol. 2009:46: 1532–1536. 10.1603/033.046.0642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richard S, Seng P, Parola P, Raoult D, Davoust B, Brouqui P. Detection of a new bacterium related to ‘Candidatus Midichloria mitochondrii’ in bed bugs. Clin Microbiol Infec 2009:15: 84–85. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02244.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsuura Y, Kikuchi Y, Meng XY, Koga R, Fukatsu T. Novel clade of alphaproteobacterial endosymbionts associated with stinkbugs and other arthropods. Appld Environ Microbiol. 2012:78: 4149 10.1128/AEM.00673-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sunagawa S, Woodley CM, Medina M. Threatened corals provide underexplored microbial habitats. PLoS ONE 2010:5: e9554 10.1371/journal.pone.0009554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lloyd SJ, LaPatra SE, Snekvik KR, St-Hilaire S, Cain KD, Call DR. Strawberry disease lesions in rainbow trout from southern Idaho are associated with DNA from a Rickettsia-like organism. Dis Aquat Organ. 2008:82: 111–118. 10.3354/dao01969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cafiso A, Sassera D, Serra V, Bandi C, McCarthy U, Bazzocchi C. Molecular evidence for a bacterium of the family Midichloriaceae (order Rickettsiales) in skin and organs of the rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum) affected by red mark syndrome. J Fish Dis. In press. 10.1111/jfd.12371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Skarphédinsson S, Jensen PM, Kristiansen K. Survey of tickborne infections in Denmark. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005:11: 1055–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bazzocchi C, Mariconti M, Sassera D, Rinaldi L, Martin E, Cringoli G, et al. Molecular and serological evidence for the circulation of the tick symbiont Midichloria (Rickettsiales: Midichloriaceae) in different mammalian species. Parasites & Vectors. 2013:6: 350 10.1186/1756-3305-6-350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mediannikov O, Ivanov LI, Nishikawa M, Saito R, Sidel’nikov IN, Zdanovskaia NI, et al. Microorganism “Montezuma” of the order Rickettsiales: the potential causative agent of tick-borne disease in the Far East of Russia. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 2004:1: 7–13, in Russian with English summary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fritsche TR, Horn M, Seyedirashti S, Gautom RK, Schleifer KH, Wagner M. In situ detection of novel bacterial endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba spp. phylogenetically related to members of the order Rickettsiales. Appl Environ Microb. 1999:65: 206–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boscaro V, Schrallhammer M, Benken KA, Krenek S, Szokoli F, Berendonk TU, et al. Rediscovering the genus Lyticum, multiflagellated symbionts of the order Rickettsiales. Sci Rep. 2013:3: 3305 10.1038/srep03305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boscaro V, Petroni G, Ristori A, Verni F, Vannini C. “Candidatus Defluviella procrastinata” and “Candidatus Cyrtobacter zanobii”, two novel ciliate endosymbionts belonging to the “Midichloria clade”. Microbial Ecol. 2013:65: 302–310. 10.1007/s00248-012-0170-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kang Y-J, Diao X-N, Zhao G-Y, Chen M-H, Xiong Y, Shi M, Fu W-M, Guo Y-J, Pan B, Chen X-P, Holmes EC, Gillespie JJ, Dumler SJ, Zhang Y-Z. Extensive diversity of Rickettsiales bacteria in two species of ticks from China and the evolution of the Rickettsiales. BMC Evol Biol. 2014:14: 167 10.1186/s12862-014-0167-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spitalska E, Boldis V, Kostanova Z, Kocianova E, Stefanidesova K. Incidence of various tick-borne microorganisms in rodents and ticks of central Slovakia. Acta Virol. 2008:52: 175–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Overbeek L, Gassner F, van der Plas CL, Kastelein P, Rocha UND, Takken W. Diversity of Ixodes ricinus tick-associated bacterial communities from different forests. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2008:66: 72–84. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dergousoff SJ, Chilton NB. Novel genotypes of Anaplasma bovis, ‘‘Candidatus Midichloria” sp. and Ignatzschineria sp. in the Rocky Mountain wood tick, Dermacentor andersoni. Vet Microbiol. 2011:150: 100–106. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ahantarig A, Trinachartvanit W, Baimai V, Grubhoffer L. Hard ticks and their bacterial endosymbionts (or would be pathogens). Folia Microbiol. 2013:58: 419–428. 10.1007/s12223-013-0222-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu LM, Liu JN, Liu Z, Yu ZJ, Xu SQ, Yang XH, et al. Microbial communities and symbionts in the hard tick Haemaphysalis longicornis (Acari: Ixodidae) from north China. Parasites & Vectors. 2013:6: 310 10.1186/1756-3305-6-310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stackebrandt E, Frederiksen W, Garrity GM, Grimont PAD, Kämpfer P, Maiden MCJ, et al. Report of the ad hoc committee for the re-evaluation of the species definition in bacteriology. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002:52: 1043–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krenek S, Berendonk TU, Petzoldt T. Thermal performance curves of Paramecium caudatum: A model selection approach. Eur J Protistol. 2011:47: 124–137. 10.1016/j.ejop.2010.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fokin SI. Paramecium genus: biodiversity, some morphological features and the key to the main morphospecies discrimination. Protistology. 2010/11:6: 227–235. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Petroni G, Dini F, Verni F, Rosati G. A molecular approach to the tangled intrageneric relationships underlying phylogeny in Euplotes (Ciliophora, Spirotrichea). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2002:22: 118–130. 10.1006/mpev.2001.1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vannini C, Rosati G, Verni F, Petroni G. Identification of the bacterial endosymbionts of the marine ciliate Euplotes magnicirratus (Ciliophora, Hypotrichia) and proposal of ‘Candidatus Devosia euplotis’. Int J Syst Evol Micr. 2004:54: 1151–1156. 10.1099/ijs.0.02759-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Amann RI, Binder BJ, Olson RJ, Chisholm SW, Devereux R, Stahl DA. Combination of 16S ribosomal-RNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microb. 1990:56: 1919–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013:41: 590–596. 10.1093/nar/gks1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cole JR, Wang Q, Cardenas E, Fish J, Chai B, Farris RJ, et al. The Ribosomal Database Project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009:37: 141–145. 10.1093/nar/gkn879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Loy A, Maixner F, Wagner M, Horn M. probeBase–an online resource for rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes: new features 2007. Nucleic Acids Res 2007:35: D800–D804. 10.1093/nar/gkl856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Manz W, Amann R, Ludwig W, Wagner M, Schleifer KH. Phylogenetic oligodeoxynucleotide probes for the major subclasses of proteobacteria: problems and solutions. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992:15: 593–600. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yilmaz LS, Ökten HE, Noguera DR. Making all parts of the 16S rRNA of Escherichia coli accessible in situ to single DNA oligonucleotides. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006:72: 733–744. 10.1128/AEM.72.1.733-744.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ludwig W, Strunk O, Westram R, Richter L, Meier H et al. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004:32: 1363–1371. 10.1093/nar/gkh293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012:9: 772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003:52: 696–704. 10.1080/10635150390235520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ronquist F, Teslenko M. van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna D, et al. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012:61: 539–542. 10.1093/sysbio/sys029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987:4: 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lo N, Beninati T, Sassera D, Bouman EAP, Santagati S, Gern L, et al. Widespread distribution and high prevalence of an alpha-proteobacterial symbiont in the tick Ixodes ricinus. Environ Microbiol. 2006:8: 1280–1287. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01024.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sassera D, Beninati T, Bandi C, Bouman EAP, Sacchi L, Fabbi M, et al. ‘Candidatus Midichloria mitochondrii’, an endosymbiont of the tick Ixodes ricinus with a unique intramitochondrial lifestyle. Int J Syst Evol Micr. 2006:58: 2535–2540. 10.1099/ijs.0.64386-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sassera D, Lo N, Epis S, D’Auria G, Montagna M, Comandatore F, et al. Phylogenomic evidence for the presence of a flagellum and cbb3 oxidase in the free-living mitochondrial ancestor. Mol Biol Evol. 2011:28: 3285–3296. 10.1093/molbev/msr159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang Z, Wu M. Phylogenomic reconstruction indicates mitochondrial ancestor was an energy parasite. PLoS ONE 2014:9: e110685 10.1371/journal.pone.0110685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yarda P, Yilmas P, Pruesse E, Glockner FO, Ludwig W, Schleifer KH, et al. Uniting the classification of cultured and uncultured bacteria and archaea using 16S rRNA gene sequences. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2014:12: 635–645. 10.1038/nrmicro3330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Venzal JW, Estrada-Peña A, Portillo A, Mangold AJ, Castro O, de Souza CG, et al. Detection of Alpha and Gamma-Proteobacteria in Amblyomma triste (Acari: Ixodidae) from Uruguay. Exp Appl Acarol. 2008:44: 49–56. 10.1007/s10493-007-9126-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Senra MXV, Dias RJP, Castelli M, da Silva-Neto ID, Verni F, Soares CAG, et al. A house for two–double bacterial infection in Euplotes woodruffi Sq1 (Ciliophora, Euplotia) sampled in southeastern Brazil. Microb Ecol. In press. 10.1007/s00248-015-0668-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Harrus S, Perlman-Avrahami A, Mumcuoglu KY, Morick D, Eyal O, Baneth G. Molecular detection of Ehrlichia canis, Anaplasma bovis, Anaplasma platys, Candidatus Midichloria mitochondrii and Babesia canis vogeli in ticks from Israel. Clin Microbiol Infec. 2010:17: 459–463. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Subramanian G, Sekeyova Z, Raoult D, Mediannikov O. Multiple tick-associated bacteria in Ixodes ricinus from Slovakia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012:3: 405–409. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sonneborn TM. Kappa and related particles in Paramecium. Adv Virus Res. 1959:6: 229–356. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Preer JR, Preer LB, Jurand A. Kappa and other endosymbionts in Paramecium aurelia. Bacteriol Rev. 1974:38: 113–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Preer JR, Preer LB. Revival of names of protozoan endosymbionts and proposal of Holospora caryophila nom. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1982:32: 140–141. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fok AK, Allen RD. The lysosome system In: Görzt HD, editor. Paramecium. Berlin: Springer; 1988. pp. 301–324. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kodama Y, Fujishima M. Induction of secondary symbiosis between the ciliate Paramecium and the green alga Chlorella In: Vilas Antonio Mendez, editor. Current Research, Technology and Education Topics in Applied Microbiology and Microbial Biotechnology. Badajoz: Formatex Research Center; 2010. pp. 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Deretic V, Levine B. Autophagy, immunity, and microbial adaptations. Cell Host Microbe. 2009:5: 527–549. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Duszenko M, Ginger ML, Brennand A, Gualdrón-López M, Colombo MI, Coombs GH, et al. Autophagy in protists. Autophagy. 2011:7: 127–158. 10.4161/auto.7.2.13310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wirawan E, Berghe TV, Lippens S, Agostinis P, Vandenabeele P. Autophagy: for better or for worse. Cell Research. 2012:22: 43–61. 10.1038/cr.2011.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Levine B. Eating oneself and uninvited guests: autophagy-related pathways in cellular defense. Cell. 2005:120: 159–162. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tallóczy Z, Virgin HW, Levine B. PKR-dependent autophagic degradation of herpes simplex virus type 1. Autophagy. 2006:2: 24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nakagawa I, Amano A, Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Yamaguchi H, Kamimoto T, et al. Autophagy defends cells against invading group A Streptococcus. Science. 2004:306: 1037–1040. 10.1126/science.1103966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gutierrez MG, Master SS, Singh SB, Taylor GA, Colombo MI, Deretic V. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell. 2004:119: 753–766. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Birmingham CL, Smith AC, Bakowski MA, Yoshimori T, Brumell JH. Autophagy controls Salmonella infection in response to damage to the Salmonella-containing vacuole. J Biol Chem. 2006:281: 11374–11383. 10.1074/jbc.M509157200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Andrade RM, Wessendarp M, Gubbels MJ, Striepen B, Subauste CS. CD40 induces macrophage anti–Toxoplasma gondii activity by triggering autophagydependent fusion of pathogen-containing vacuoles and lysosomes. J Clin Invest. 2006:116: 2366–2377. 10.1172/JCI28796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Campoy E, Colombo MI. Autophagy subversion by bacteria In: Levine B, Yoshimori T, Deretic V, editors. Autophagy in infection and immunity. Berlin: Springer; 2009. pp. 227–250. 10.1007/978-3-642-00302-8_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pareja MEM, Colombo MI. Autophagic clearance of bacterial pathogens: molecular recognition of intracellular microorganisms. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013:3: 54 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Friedrich N, Hagedorn M, Soldati-Favre D, Soldatib T. Prison break: pathogens’ strategies to egress from host cells. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2012:76: 707 10.1128/MMBR.00024-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Goldberg MB. Actin-based motility of intracellular microbial pathogens. Microbiol Mol Biol R. 2001:65: 595–626. 10.1128/MMBR.65.4.595-626.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Heinzen RA. Rickettsial actin-based motility behavior and involvement of cytoskeletal regulators In: Hechemy KE, AvsicZupanc T, Childs JE, Raoult DA, editors. Rickettsiology: Present and Future Directions. New York: Ann NY Acad Sci; 2003. pp. 535–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sabaneyeva EV, Derkacheva ME, Benken KA, Fokin SI, Vainio S, Skovorodkin IN. Actin-based mechanism of Holospora obtusa trafficking in Paramecium caudatum. Protist. 2009:160: 205–219. 10.1016/j.protis.2008.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fujishima M. Infection and maintenance of Holospora species in Paramecium caudatum In: Fujishima M, editor. Endosymbionts in Paramecium. Microbiology Monographs 12 Berlin: Springer; 2009. pp. 201–225. 10.1007/978-3-540-92677-1_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Varela AR, Manaia CM. Human health implications of clinically relevant bacteria in wastewater habitats. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2013:20: 3550–3569. 10.1007/s11356-013-1594-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dowd SE, Gerba CP, Pepper IL. Confirmation of the human-pathogenic Microsporidia Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Encephalitozoon intestinalis, and Vittaforma corneae in water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998:64: 3332–3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gerba CP, Smith JE. Sources of pathogenic microorganisms and their fate during land application of wastes. J Environ Qual. 2005:34: 42–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Curds CR. The flocculation of suspended matter by Paramecium caudatum. J Gen Microbiol. 1963:33: 357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Curds CR, Fey GJ. The effect of ciliated protozoa on the fate of Escherichia coli in the activated sludge process. Water Res. 1969:3: 853–867. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Curds CR. The ecology and role of protozoa in aerobic sewage treatment processes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1982:36: 27–46. 10.1146/annurev.mi.36.100182.000331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Görtz HD, Fokin SI. Diversity of endosymbiotic bacteria in Paramecium In: Fujishima M, editor. Endosymbionts in Paramecium. Microbiology Monographs 12 Berlin: Springer; 2009. pp. 131–160. 10.1007/978-3-540-92677-1_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Rowbotham T. Preliminary report on the pathogenicity of Legionella pneumophila for freshwater and soil amoebae. J Clin Pathol. 1980:33: 1179–1183. 10.1136/jcp.33.12.1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hilbi H, Hoffmann C, Harrison CF. Legionella spp. outdoors: colonization, communication and persistence. Environ Microbiol Reports. 2011:3: 286–296. 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2011.00247.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hoffmann C, Harrison CR, Hilbi H. The natural alternative: protozoa as cellular models for Legionella infection. Cell Microbiol. 2014:16: 15–26. 10.1111/cmi.12235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mura M, Bull TJ, Evans H, Sidi-Bournedine K, McMinn L, Rhodes G, et al. Replication and long-term persistence of bovine and human strains of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis within Acanthamoeba polyphaga. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006:72: 854–859. 10.1128/AEM.72.1.854-859.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Schrallhammer M, Schweikert M, Vallesi A, Verni F, Petroni G. Detection of a novel subspecies of Francisella noatunensis as endosymbiont of the ciliate Euplotes raikovi. Microbial Ecol. 2011:61: 455–464. 10.1007/s00248-010-9772-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Görtz HD, Maier G. A bacterial infection in a ciliate from sewage sludge. Endocyt Cell Res. 1991:8: 45–52. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

22 closely related sequences of the Midichloriaceae family, 17 members of the Anaplasmataceae and Rickettsiaceae and 10 other Alphaproteobacteria representing the outgroup were aligned with “Ca. Fokinia solitaria” to perform phylogenetic analyses. The alignment was trimmed at both ends to reach the length of the shortest sequence on each side, the resulting 1,568 nucleotide columns are presented here.

(S1_ALIGNMENT)

The parameters are given as total tree length (TL), reversible substitution rates (r(A<->C), r(A<->G), etc), stationary state frequencies of the four bases (pi(A), pi(C), etc), the shape of the gamma distribution of rate variation across sites (alpha), and the proportion of invariable sites (pinvar). The estimated sampling size (ESS) is shown as minimal (minESS) and average (avgESS) values. PSRF stands for potential scale reduction factor.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

The SSU rRNA gene sequence of "Ca. Fokinia solitaria" is available on GenBank database (NCBI) (accession number: KM497527). Species specific oligonucleotide probes were uploaded on probeBase and Figshare (DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.2008524).