Abstract

Background

Few studies have examined the effect of a behavioral weight loss intervention (BWLI) on young adults (age = 18 to 35 years).

Methods

Participants (N=470) enrolled in a 6 month BWLI that included weekly group sessions, a prescribed energy restricted diet and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA). Assessments included weight, body composition, fitness, lipids, glucose, insulin, resting blood pressure and heart rate, physical activity, and dietary intake. Data are presented as median [25th, 75th percentiles].

Results

Retention was 90% (N=424; age: 30.9 [27.8, 33.7] years; BMI: 31.2 [28.4, 34.3] kg/m2). Participants completed 87.5% (76.1%, 95.5%) of scheduled intervention contacts. Weight and body fat decreased while fitness increased (p<0.0001). MVPA in bouts ≥10 minutes increased (p<0.0001), though total MVPA did not change significantly. Sedentary time decreased (p=0.03). Energy and percent fat intake decreased, while percent carbohydrate and protein intake increased (p<0.0001). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and insulin decreased (p<0.0001).

Conclusions

A 6 month BWLI produced favorable changes in dietary intake and physical activity and elicited favorable changes in weight and other health outcomes in young adults. MVPA performed in bouts of ≥10 minutes was associated with greater weight loss, but sedentary behavior was not.

Keywords: Weight Loss, Behavior Modification, Diet, Physical Activity, Risk Factors

Introduction

Overweight and obesity are significant public health concerns in the United States.(1) Young adults are not immune to being overweight or obese, with 60.3% of 20–39 year old adults meeting these clinical classifications based on population-based data,(1) and young adults may be prone to gain weight.(2) Thus, there is a need for interventions that treat overweight and obese young adults.

Lifestyle interventions for weight loss combine reduced energy intake and increased energy expenditure, resulting in an average weight loss of approximately 8% to 10% of initial body weight within the initial 6 months of treatment.(3) The majority of these interventions have been implemented middle-age or older adults.(4–13) Whether these interventions are effective for weight loss among younger adults is unclear.

This report examined whether a 6 month behavioral intervention would result in an increase in physical activity, reduction in energy intake, and favorable changes in weight, body composition, fitness, and cardiovascular disease risk factors in young adults. In addition, exploratory analyses were conducted to examine non-modifiable demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, race and ethnicity, etc.) and intervention components as predictors of change in weight.

Methods

A consortium of studies was formed to focus on weight loss or preventing weight gain in young adults (EARLY Trials).(14) Young adults were defined as individuals 18 to 35 years at study enrollment. Each study in the consortium implemented different interventions. In IDEA (Innovative approaches to Diet, Exercise, and Activity), participants received the same behavioral weight loss intervention for 6 months after which two different interventions were implemented to examine outcomes at month 24. This study reports on the initial 6 months of the intervention during which all participants received the identical weight loss intervention.

Participants

Participants were recruited between October 2010 and October 2012 using direct mail strategies, mass media advertisements, or referral from clinical research registries, friends, family, or other study participants. Medical history and a physical activity readiness questionnaire were completed, and clearance from the participant’s physician was obtained prior to study participation. Procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Eligibility criteria included age between 18 to 35 years and body mass index (BMI) within 25.0 to <40.0 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria included: 1) past or planned weight loss surgery; 2) current use of systemic steroids or weight loss medication, 3) current treatment for an eating disorder, 4) cardiovascular event (heart attack, stroke, episode of heart failure, or revascularization procedure) within the prior 6 months; 5) current treatment for malignancy other than non-melanoma skin cancer; 6) currently pregnant or gave birth within the last 6 months, currently lactating or breastfeeding within the last 3 months, actively planning pregnancy within the study period; 7) taking medication that would affect heart rate or blood pressure responses to exercise (e.g., beta blockers); 8) self-reported weight loss of >5% of current body weight in the previous 3 months; 9) current treatment for psychological issues or taking psychotropic medications within the previous 6 months; 10) taking medication that could affect metabolism, appetite, or change body weight; 11) current treatment for diabetes mellitus; 12) history of heart disease, angina, heart attack, stroke, or cancer; 13) taking medication for hypertension, resting systolic blood pressure of ≥160 mmHg, or resting diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg; 14) investigator discretion due to concerns related to study compliance; 15) unable or unwilling to provide written consent; 16) household member on the study staff.

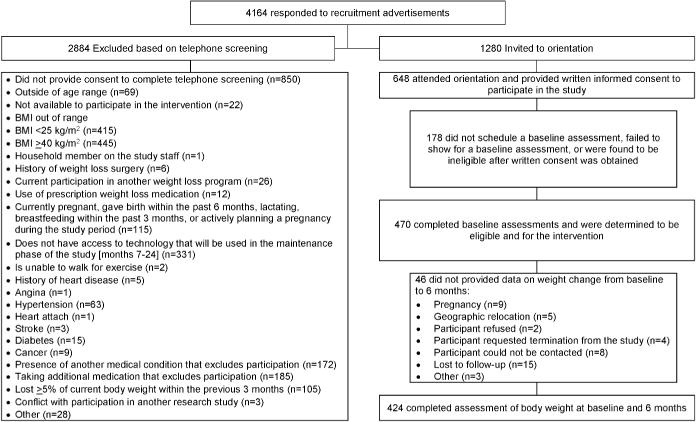

This study conducted 4,164 telephone interviews to identify 470 eligible study participants (Figure 1). Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of young adults participating in a behavioral weight loss intervention

| Subjects Eligible to Initiate the Intervention (N=470) | Analysis Sample: Subjects with body weight assessed at 6 months (N=424) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 30.9 (27.8, 33.7) | 31.0 (27.6, 33.7) |

| Range | 18.5–35.9 | 18.5–35.9 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 31.2 (28.4, 34.3) | 31.2 (28.4, 34.3) |

| Range | 24.4–39.9 | 24.4–39.9 |

| Gender* | ||

| Male | 136 (28.9%) | 127 (30.0%) |

| Female | 334 (71.1%) | 297 (70.0%) |

| Race* | ||

| White | 363 (77.2%) | 333 (78.5%) |

| Non-white | 107 (22.8%) | 91 (21.5%) |

| Hispanic/Latino* | ||

| Yes | 20 (4.3%) | 19 (4.5%) |

| No | 450 (95.7%) | 405 (95.5%) |

| Relationship status* | ||

| Married/like married | 233 (49.6%) | 211 (49.8%) |

| Single/separated/divorced | 237 (50.4%) | 213 (50.2%) |

| Number of adults in home* | ||

| 1 | 149 (31.7%) | 130 (30.7%) |

| 2 | 266 (56.6%) | 244 (57.5%) |

| 3 or more | 55 (11.7%) | 50 (11.8%) |

| Children in home* | ||

| 0 | 271 (57.7%) | 247 (58.3%) |

| 1 | 71 (15.1%) | 58 (13.7%) |

| 2 | 82 (17.4%) | 77 (18.2%) |

| 3 or more | 46 (9.8%) | 42 (9.9%) |

| Education* | ||

| High school graduate or Graduate Equivalency Degree (GED) | 117 (24.9%) | 102 (24.1%) |

| College graduate or higher | 323 (75.1%) | 322 (75.9%) |

| Student status* | ||

| Not student | 349 (74.3%) | 314 (74.1%) |

| Currently a student (part-time or full-time) | 121 (25.7%) | 110 (25.9%) |

| Current Employment Status* | ||

| Full-time for pay | 357 (76.0%) | 323 (76.2%) |

| Part-time for pay | 65 (13.8%) | 57 (13.4%) |

| Other | 44 (9.4%) | 40 (9.4%) |

| Missing | 4 (0.9%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Household income * | ||

| Missing | 4 (0.9%) | 4 (0.9%) |

| Less than $25,000 | 58 (12.4%) | 50 (11.8%) |

| $25,000 – $49,999 | 132 (28.3%) | 120 (28.6%) |

| $50,000 –$74,999 | 101 (21.7%) | 91 (21.7%) |

| $75,000 – $99,999 | 97 (20.8%) | 89 (21.2%) |

| $100,000 or more | 78 16.7%) | 70 (16.7%) |

Values are expressed as number of subjects (%)

Outcome Assessments

Outcomes were assessed at 0 and 6 months. Participants were compensated $100 for completing 6 month assessments.

Weight, Height, BMI

Weight was assessed on a digital scale to the nearest 0.1 kg with the participant clothed in a hospital gown or light-weight clothing. Height was measured only at baseline to the nearest 0.1 cm. BMI was computed as kg/m2.

Body Composition

Body composition was assessed using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) from a total body scan (GE Lunar iDXA, Madison, WI).

Resting Blood Pressure and Heart Rate

Resting blood pressure and heart rate were assessed following a 5 minute seated resting period using an automated system. Participants with systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mmHg or <90 mmHg, or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg were referred to their physician for follow-up evaluation.

Blood Analysis

Blood samples were analyzed for lipids (total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides), glucose, and insulin, with LDL cholesterol calculated using the Friedwald equation.(15) Participants were instructed to fast, other than water, and to abstain from exercise for 12 hours prior to their assessment.

Cardiorespiratory Fitness

A submaximal graded exercise test performed on a motorized treadmill. The speed was constant at 80.4 m/min, with grade starting at 0% and increasing by 1% until the point of test termination. Test termination occurred when the participant achieved 85% of age-predicted maximal heart rate (age-predicted maximal heart rate = 220 − age). Oxygen consumption was assessed using a metabolic cart.

Physical Activity

Physical activity was measured using a device worn for one week (SenseWear Pro Armband, BodyMedia, Inc.), which has been shown to provide a valid measure of energy expenditure when compared to indirect calorimetry(16) and to doubly-labeled water.(17) Data were used to identify minutes of sedentary (1.5 METs), light-intensity physical activity (LPA = 1.5 to <3.0 METs) and moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA: ≥3.0 METs) physical activity. Only data from participants who wore the device for ≥10 hours per day for ≥4 days were used for data analysis.(18, 19)

Dietary Intake

Dietary intake and macronutrient composition were assessed using the Diet History Questionnaire.(20, 21) Participants reported the frequency and amount of various foods consumed over the prior month. DietCalc software (version 1.5.0) was used to analyze these data.

Behavior Weight Loss Intervention

Participants received a 6 month intervention that included group-based behavioral sessions, prescribed diet, and prescribed physical activity. These components are described below and also within the supplemental materials.

Intervention Sessions

Weekly group-based behavioral sessions were provided to promote engagement and adherence to the prescribed diet and physical activity. If unable to attend a scheduled group session, attempts were made to engage the participant in an individual or telephone-based make up session. Participants were weighed at each session to allow for feedback on weight loss progress. Group sessions focused on educating participants on the components of the prescribed diet and physical activity, along with a focus on behavioral strategies to promote adherence to these weight loss behaviors. The intervention was based on a multi-theoretical approach that included social-cognitive theory,(22) health belief model,(23, 24) problem-solving theory,(25) and relapse prevention.(26)

Dietary Intervention

Calorie intake was prescribed at 1200, 1500, and 1800 kcal/d for individuals with a baseline weight of <90.7 kg, 90.7 to <113.4 kg, and ≥113.5 kg, respectively. Individual calorie intake was adjusted upward if weight loss exceeded 6% at the end of each 4 week period or to prevent further weight loss when BMI was ≤22 kg/m2. Dietary fat was prescribed at 20 to 30% of total calorie intake. Participants were instructed to self-monitor dietary intake in a diary that was returned to the investigators at the conclusion of each week. The intervention staff provided feedback on these diaries prior to returning them to the participant.

Physical Activity

Non-supervised physical activity was initially prescribed at 100 minutes per week and increased by 50 minutes per week at 4 week intervals until a prescription of 300 minutes per week was achieved. Participants were instructed to engage in structured forms of physical activity that were ≥10 minutes in duration. Physical activity was prescribed at a MVPA intensity. Participants were instructed to self-monitor their daily MVPA in a diary that was returned to the intervention staff at the conclusion of each week. The intervention staff provided feedback on these diaries prior to returning them to the participant.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages for categorical variables; medians, 25th and 75th percentiles, minima and maxima for continuous variables) were used to summarize baseline characteristics. Those excluded from the analysis sample (n=46) were compared to those in the analysis sample (n=424) using the chi square test for categorical variables or the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables.

Statistical significance of change in weight, body composition, cardiometabolic risk factors, physical activity, and dietary intake from baseline to 6 months was assessed with McNemar’s test for paired dichotomous variables, or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variables. Distributions for several of the variables were skewed such that the mean was not a useful measure of central tendency. To avoid potential confusion the median for all variables was reported, which equals the mean for normally distributed data.

Linear mixed models were used to examine associations between factors and percentage weight change from baseline to 6 months. Intervention was delivered in groups, so models controlled for group as a random effect to account for possible clustering effects. Four models were constructed. The first three models evaluated pre-intervention predictors. Model 1 included sociodemographics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, employment, household income, student status, marital status, and number of children in the home). Categories of the sociodemographic factors that did not differ significantly in percent weight loss in univariate analysis were combined, and therefore categories of household income were collapsed as <$25,000 and ≥$25,000. Model 2 added baseline BMI to the variables in model 1. Model 3 added baseline behavioral factors (percentage sedentary time, LPA [MET-minutes/week], MVPA [MET-minutes/week] completed in sessions at least 10 minutes in duration, energy intake [kcal/day], percentage of calories consumed as fat, and percentage of calories consumed as protein) to the variables in model 2. Because the percentage of calories from carbohydrates is 100% minus the sum of the percentage calories from fat and protein, it was not included in the model to avoid collinearity. An alternative version of model 3 substituted total MVPA (MET-minutes/week) for MVPA (MET-minutes/week) completed in sessions at least 10 minutes. Model 4 examined the association of percent weight loss at 6 months with intervention adherence variables (percentage of intervention sessions attended, percentage of intervention diaries returned), and pre- to post- intervention changes in sedentary behavior, physical activity, and dietary intake, while controlling for factors included in model 3. Interactions between significant main effects were tested and included if they reached statistical significance. All reported p-values are two-sided. P-values less than 0.05 are considered to be statistically significant.

Results

This study recruited 471 participants. Prior to initiating the intervention, one participant was found to be ineligible and is excluded from these analyses. Thus, 470 initiated the weight loss intervention, with 46 participants not completing the 6 month assessment (Figure 1). Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in characteristics between those included (n=424) and excluded from analysis (n=46), with the exception of race. Black participants had lower representation in the analysis sample compared to those who did not complete the 6 month assessment (21.5% vs. 34.8%; p=0.04).

Weight and Body Composition

Weight and body composition are shown in Table 2. Median weight change at 6 months of −7.8 (25th, 75th %-iles: −12.2, −3.7) kg and percentage weight change of −8.8% (25th, 75th %-iles: −13.4%, −3.8%) were significantly different from 0 (p<0.0001). There was a reduction in fat mass (p<0.0001), a modest but significant reduction in lean body mass (p<0.0001), and a reduction in percent body fat (p<0.0001). Bone mass (p<0.0001) and total body bone mineral density (p=0.008) also showed modest but significant decreases.

Table 2.

Weight related measures and body composition of young adults in a six month behavioral weight loss intervention.

| N | Baseline | 6 months | Change | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Weight, kg | 424 | <.0001 | |||

| median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 90.3 (79.5, 101.9) | 81.3 (72.2, 92.7) | −7.8 (−12.2, −3.7) | ||

| Range | 60.1–146.1 | 54.2–132.9 | −31.5–10.4 | ||

|

| |||||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 424 | <.0001 | |||

| median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 31.2 (28.4, 34.4) | 28.1 (25.7, 31.4) | −2.7 (−4.2, −1.2) | ||

| Range | 24.4–39.9** | 20.0–39.7 | −9.4–4.1 | ||

|

| |||||

| Fat mass, kg | 422 | <.0001 | |||

| median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 36.4 (30.2, 42.5) | 29.6 (23.5, 35.8) | −6.0 (−10.0, −2.8) | ||

| Range | 17.5–62.4 | 8.8–62.0 | −28.6–8.1 | ||

|

| |||||

| Lean mass, kg | 422 | <.0001 | |||

| median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 48.6 (43.5, 58.1) | 47.2 (42.6, 56.1) | −1.1 (−2.3, −0.1) | ||

| Range | 33.1–85.7 | 32.8–83.7 | −9.6–3.4 | ||

|

| |||||

| Total mass, kg | 422 | <.0001 | |||

| median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 89.6 (79.2, 101.4) | 81.2 (72.2, 92.2) | −7.3 (−11.8, −3.5) | ||

| Range | 59.7–144.4 | 54.4–131.8 | −30.0–10.1 | ||

|

| |||||

| Percent body fat, % | 422 | <.0001 | |||

| median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 40.7 (36.5, 45.1) | 37.2 (30.9, 41.9) | −3.8 (−6.4, −1.7) | ||

| Range | 19.8–56.0 | 12.0–54.9 | −21.4–3.5 | ||

|

| |||||

| *** Tissue percent body fat, % | 422 | <.0001 | |||

| median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 42.0 (37.8, 46.5) | 38.5 (32.1, 43.3) | −3.8 (−6.4, −1.7) | ||

| Range | 20.7–57.4 | 12.6–56.3 | −22.0–3.5 | ||

|

| |||||

| Percent lean mass, % | 422 | ||||

|

| |||||

| median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 59.3 (54.9,63.5) | 62.8 (58.1, 69.1) | 3.8 (1.7, 6.4) | <.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Range | 44.0–80.2 | 45.1–88.0 | −3.5–21.4 | ||

|

| |||||

| *** Tissue percent lean mass, % | 422 | ||||

|

| |||||

| median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 58.0 (53.5, 62.2) | 61.5 (56.7, 67.9) | 3.8 (1.7, 6.4) | <.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Range | 42.6–79.3 | 43.7–87.4 | −3.5–22.0 | ||

|

| |||||

| Bone Mass, grams | 422 | ||||

| median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 2767.1 (2517.3, 3103.5) | 2765.6 (2524.8, 3080.5) | −11.6 (−34.9, 10.3) | <.0001 | |

| Range | 1913.0–4638.5 | 1888.3–4631.3 | −128.8–213.3 | ||

|

| |||||

| Total Body Bone Mineral Density, g/cm2 | 422 | 0.008 | |||

| median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 1.3 (1.2, 1.4) | 1.3 (1.2, 1.4) | −0.002 (−0.014, 0.009) | ||

| Range | 1.0–1.7 | 1.0–1.7 | −0.1–0.1 | ||

Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Participants were deemed eligible based on assessment of BMI at the orientation session; however, outcome measures are based on data collected at the assessment session, which at baseline may reflect a BMI <25 kg/m2.

Excluding bone mass.

Dietary Intake and Physical Activity

Dietary intake data at baseline and 6 months were available for 417 participants (Table 3). There was a reduction in daily energy intake (p<0.0001) and percent dietary fat intake (p<0.0001), and an increase in percent carbohydrate intake (p<0.0001) and percent protein intake (p<0.0001).

Table 3.

Change in physical activity and dietary intake of young adults in a six month behavioral weight loss intervention.

| N | Baseline | 6 months | Change | P-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Physical Activity | ||||||

| Sedentary (% of monitor wear time) |

Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 385 | 65.4 (57.4, 72.7) | 65.0 (52.2, 74.7) | −0.6 (−10.6, 6.9) | 0.03 |

| Range | 7.0–91.3 | 3.9–95.5 | −58.6–44.6 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Sedentary (hours/day) |

Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 385 | 9.1 (7.9, 10.2) | 8.8 (7.3, 10.4) | −0.2 (−1.6, 1.0) | 0.02 |

| Range | 1.0–13.4 | 0.6–14.6 | −8.8–6.0 | |||

|

| ||||||

| LPA (minutes/week) |

Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 386 | 1537.0 (1149.0, 1961.0) | 1583.0 (1123.0, 2184.0) | 59.2 (−320.0, 523.0) | 0.01 |

| Range | 415.0–3848.0 | 175.0–4581.0 | −1842.0–3215.0 | |||

|

| ||||||

| LPA (MET-minutes/week) |

Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 386 | 3132.6 (2355.6, 4010.9) | 3099.5 (2202.5, 4268.0) | 20.0 (−778.1, 884.5) | 0.66 |

| Range | 757.7–8663.1 | 325.7–9692.1 | −4788.0–6172.9 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Total MVPA (minutes/week) |

Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 386 | 422.2 (289.0, 611.0) | 423.3 (254.0, 666.0) | −22.6 (−156.0, 172.0) | 0.94 |

| Range | 66.0–3168.0 | 8.0–3019.0 | −2542.0–1880.0 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Total MVPA (MET-min/wk) |

Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 386 | 1532.9 (1040.8, 2287.5) | 1537.8 (895.0, 2440.0) | −95.0 (−609.8, 661.4) | 0.82 |

| Range | 231.0–13362.8 | 29.6–10689.7 | −10093.2–7344.6 | |||

|

| ||||||

| ≥10 minute sessions of MVPA (minutes/week) |

Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 386 | 100.0 (26.0, 192.0) | 214.5 (99.0, 389.0) | 103.4 (3.0, 247.0) | <0.0001 |

| Range | 0–1889.0 | 0–2182.8 | −1521.0–1823.0 | |||

|

| ||||||

| ≥10 minute sessions of MVPA (MET-minutes/week) |

Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 386 | 427.7 (118.2, 859.4) | 945.3 (415.0, 1753.8) | 420.6 (0, 1035.8) | <0.0001 |

| Range | 0–11393.3 | 0–10225.3 | −7709.8–7378.8 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Dietary Intake | ||||||

| Total calories (kcal/day) | Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 417 | 1655.1 (1224.9, 2284.4) | 1257.6 (909.6, 1677.3) | −397.2 (−800.4, −63.1) | <0.0001 |

| Range | 458.3–13317.3 | 96.6–6247.7 | −9743.3–2330.5 | |||

|

| ||||||

| % calories carbohydrates |

Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 417 | 47.6 (42.9, 52.4) | 50.3 (45.4, 56.8) | 2.5 (−2.4, 7.5) | <0.0001 |

| Range | 24.7–75.2 | 26.7–77.3 | −36.8–33.7 | |||

|

| ||||||

| % calories protein | Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 417 | 15.9 (14.1, 18.0) | 16.8 (14.8, 18.4) | 0.8 (−1.4, 2.8) | <0.0001 |

| Range | 6.5–34.6 | 7.7–27.4 | −20.6–14.2 | |||

|

| ||||||

| % calories fat | Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 417 | 35.3 (30.3, 39.0) | 31.4 (27.2, 35.6) | −3.5 (−7.8, 0.6) | <0.0001 |

| Range | 15.9–57.3 | 13.4–59.6 | −25.3–32.2 | |||

MET: metabolic equivalent; LPA: light-intensity physical activity (1.5 to <3.0 METs); MVPA: moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (≥3.0 METs).

Wilcoxon signed rank test.

The device to assess physical activity was worn by 415 participants at both baseline and 6 months, with 386 participants having sufficient weartime (at least 4 days and for at least 10 hours per day) at both assessment periods (Table 3). When compared to those participants providing usable physical activity data, a higher percentage of those not providing usable date were female, non-white, a high school graduate or earning graduate equivalency degree (GED), and currently a student. Reasons for missing data included lack of sufficient wear time of ≥4 days for ≥10 hours per day (n=6 at baseline, n=19 at 6 months, n=4 at both baseline and 6 months), with 55 missing due to the participant not wearing the device or failing to return the device. The device was worn for 7, 6, 5, or 4 days by 85.2%, 10.4%, 3.4% or 1.0% of participants, respectively, for a median of 14.0 (25th, 75th %-iles: 13.3, 14.6) hours per day at baseline. At 6 months the percent of participants who wore the device for 7, 6, 5, or 4 days was 80.8%, 10.6%, 4.9%, or 3.6%, respectively for 14.0 (25th, 75th %-iles: 13.2, 14.6) hours per day.

There was a modest but significant reduction in sedentary behavior defined as percent of the non-sleeping time that the device was worn for which energy expenditure was <1.5 METs (p=0.03). MET-min/week of total LPA or MVPA did not change; however, there was a significant increase of 103.4 (3.0, 247.0) min/week and 420.6 (25th, 75th %-iles: 0, 1035.8) MET-min/week of MVPA performed in bouts of ≥10 minutes (p<0.0001). Participants engaging in at least 150 minutes of MVPA performed in bouts of ≥10 minutes increased from 132 (34.2%) at baseline to 256 (66.3%) at 6 months. Significantly more participants not engaging in at least 150 minutes of MVPA performed in bouts of ≥10 minutes at baseline increased to this level at 6 months (n=141), than participants engaging in at least 150 minutes of MVPA performed in bouts of ≥10 minutes at baseline and then not achieving this level at 6 months (n=17, p<.0001).

Intervention Process Data

Participants returned a median of 87.5% (25th, 75th %-iles: 58.3%, 95.8%) of the expected 24 intervention diaries and attended 87.5% (25th, 75th %-iles: 76.1%, 95.5%) of the scheduled intervention contacts. Intervention contact consisted of attendance at a median of 17.0 (25th, 75th %-iles: 13.0, 20.0) group sessions and 2.0 (25th, 75th %-iles: 1.0, 4.0) as individual make-up sessions, with 9.0% (n=38) completing 1 make-up session via telephone and 9.4% (n=40) completing ≥2 make-up sessions via telephone.

Other Health-Related Outcomes

Changes in resting heart rate and blood pressure were available for 422 participants (Table 4). There was a decrease is resting heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure (p<0.0001). None of the participants were taking anti-hypertensive medication at baseline, whereas 2 participants were taking this type of medication at 6 months.

Table 4.

Changes in resting heart rate, resting blood pressure, fasting lipids, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and cardiorespiratory fitness of young adults in a 6 month behavioral weight loss intervention.

| N | Baseline | 6 months | Change | P-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Resting heart rate (beats/minute) | Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 422 | 70.0 (63.5, 77.5) | 64.5 (58.0, 71.5) | −5.5 (−11.0, 0) | <.0001 |

| Range | 42.7–133.0 | 42.0–96.0 | −54.0–19.5 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 422 | 114.5 (107.5, 121.5) | 109.5 (104.5, 117.0) | −4.0 (−8.5, 0.5) | <.0001 |

| Range | 83.0–152.5 | 89.5–154.5 | −32.0–29.5 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 422 | 70.0 (64.5, 76.5) | 67.0 (61.5, 72.5) | −3.0 (-6.5, 1.0) | <.0001 |

| Range | 52.0–98.0 | 53.5–94.0 | −22.5–22.0 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 416 | 180.0 (159.5, 201.0) | 164.0 (149.0, 184.0) | −13.0 (−28.0, 2.0) | <.0001 |

| Range | 87.0–298.0 | 100.0–283.0 | −99.0–108.0 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Low-density lipoprotein Cholesterol (mg/dl) | Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 416 | 103.5 (83.9, 124.1) | 92.9 (78.6, 111.0) | −9.5 (−21.7, 2.0) | <.0001 |

| Range | 25.0–229.2 | 14.8–187.4 | −72.9–82.1 | |||

|

| ||||||

| High-density lipoprotein Cholesterol (mg/dl) | Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 416 | 51.5 (41.6, 62.1) | 51.9 (42.9, 61.6) | 0 (−5.2, 5.4) | 0.72 |

| Range | 21.5–115.0 | 21.0–104.0 | −28.6–24.5 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 416 | 97.0 (70.0, 135.0) | 81.5 (62.0, 109.0) | −8.5 (−44.0, 9.0) | <.0001 |

| Range | 21.0–523.0 | 27.0–314.0 | −388.0–135.0 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 416 | 93.0 (87.5, 99.0) | 89.0 (84.5, 94.0) | −4.0 (−8.0, 1.0) | <.0001 |

| Range | 64.0–142.0 | 70.0–164.0 | −35.0–74.0 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Insulin (μU/ml) | Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 416 | 14.2 (10.7, 18.7) | 11.3 (8.8, 15.3) | −2.6 (−5.9, 0.7) | <.0001 |

| Range | 2.5–82.7 | 2.0–55.7 | −54.9–45.4 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Cardiorespiratory Fitness (ml/kg/min) | Median (25th, 75th %-iles) | 416 | 26.0 (22. 7, 29.9) | 29.0 (25.4, 35.0) | 3.6 (0.8, 6.2) | <.0001 |

| Range | 14.4–50.1 | 15.8–58.5 | −13.7–28.3 | |||

Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Change in blood parameters were available on 416 participants (Table 4). Total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and insulin decreased (p<0.0001). There was not a significant change in HDL cholesterol (p=0.72). At baseline 6 participants reported taking lipid-lowering medication, whereas 4 participants reported taking this type of medication at 6 months.

Data on change in cardiorespiratory fitness were available for 416 participants (Table 4). There was an increase in cardiorespiratory fitness (median: 3.6, 25th, 75th %-iles: 0.8, 6.2 ml/kg/min, p<0.0001).

Change in Outcomes by Magnitude of Weight Loss

Participants were also categorized by magnitude of weight loss (Table 5). There were significant trends for a greater proportion of participants at higher magnitudes of weight loss to have reductions in resting heart rate and blood pressure, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and insulin, and a greater proportion having an increase in fitness. Moreover, there were significant trends for the magnitude of change in these outcomes to be greater as weight loss increased.

Table 5.

Change in outcomes from baseline to 6 months by weight change category at 6 months.

| Weight Change Category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with Weight Gain or No Weight Loss | Participants with <5% Weight Loss | Participants with 5% to <10% Weight Loss | Participants with ≥10% Weight Loss | P-value* | |

| Body Weight change, kg | |||||

| N | 30 | 94 | 121 | 179 | |

| Median change (25th, 75th %-iles) | 1.2 (0.4, 2.5) | −2.4 (−3.5, −1.2) | −6.4 (−8.0, −5.5) | −13.2 (−17.8, −10.5) | NA*** |

| Fat mass, kg | 29 | 94 | 120 | 179 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 5 (17.2%) | 80 (85.1%) | 120 (100%) | 179 (100%) | <0.0001 |

| Median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −0.9 (−1.2, −0.4) | −2.2 −3.1, −1.4) | −5.5 (−6.7, −4.2) | −10.7 (−13.8, −8.4) | <0.0001 |

| Lean mass, kg | 29 | 94 | 120 | 179 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 10 (34.5%) | 55 (58.5%) | 95 (79.2%) | 166 (94.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Median loss (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −0.8 (−0.3, −0.1) | −0.8 (−1.2, −0.5) | −1.3 (−1.9, −0.6) | −2.4 (−3.6, −1.5) | <0.0001 |

| Percent body fat, % | 29 | 94 | 120 | 179 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 8 (27.6%) | 77 (81.9%) | 119 (99.2%) | 179 (100%) | <0.0001 |

| median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | -0.6 (−1.0, −0.3) | −1.5 (−2.0, −0.9) | −3.2 (−4.6, −2.3) | −6.9 (−9.5, −5.2) | <0.0001 |

| **** Tissue percent body fat, % | 29 | 94 | 120 | 179 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 9 (31.0%) | 76 (80.9%) | 119 (99.2%) | 179 (100%) | <0.0001 |

| Median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −0.6 (−0.9, −0.2) | −1.5 (−2.1, −0.9) | −3.2 (−4.7, −2.3) | −6.9 (−9.7, −5.2) | <0.0001 |

| Percent lean mass, % | 29 | 94 | 120 | 179 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 21 (72.4%) | 17 (18.1%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | <0.0001 |

| Median loss (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −1.0 (−1.6, −0.5) | −0.6 (−1.2, −0.4) | −0.4 (NA) | NA | 0.21 |

| **** Tissue percent lean mass, % | 29 | 94 | 120 | 179 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 20 (69.0%) | 18 (19.2%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (10%) | <0.0001 |

| Median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −1.0 (−1.6, −0.5) | −0.6 (−1.3, −0.5) | −0.5 (NA) | NA | 0.12 |

| Bone Mass, kg | 29 | 94 | 120 | 179 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 11 (37.9%) | 47 (50.0%) | 76 (63.3%) | 140 (78.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −0.018 (−0.035, −0.008) | −0.018 (−0.30, −0.009) | −0.024 (−0.042, −0.011) | −0.032 (−0.054, −0.017) | <0.0001 |

| Total Body Bone Mineral Density, g/cm2 | 29 | 94 | 120 | 179 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 15 (51.7%) | 48 (51.1%) | 62 (51.7%) | 70 (39.1%) | 0.04 |

| Median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | 0.010 (0.005, 0.020) | 0.009 (0.005, 0.017) | 0.006 (0.003, 0.016) | 0.015 (0.008, 0.020) | 0.17 |

| Resting Heart Rate (beat per minute) | 29 | 93 | 121 | 179 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 11 (37.9%) | 65 (69.9%) | 90 (74.4%) | 149 (83.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −7.5 (−13.5, −3.5) | −6.5 (−11.0, −4.0) | −7.5 (−12.0, −4.0) | −9.0 (−14.5, −4.0) | 0.01 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 29 | 93 | 121 | 179 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 17 (58.6%) | 60 (64.5%) | 79 (65.3%) | 136 (76.0%) | 0.01 |

| Median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −5.0 (−9.5, −1.5) | −5.5 (−8.3, −3.0) | −6.0 (−9.0, −2.5) | −8.0 (−12.0, −4.5) | 0.0001 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 29 | 93 | 121 | 179 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 17 (56.7%) | 62 (66.0%) | 83 (68.6%) | 130 (72.6%) | 0.05 |

| Median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −5.5 (−8.3, −2.3) | −4.0 (−7.0, −2.0) | −5.5 (−8.2, −3.0) | −6.1 (−9.5, −3.0) | 0.01 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 28 | 91 | 120 | 177 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 15 (53.6%) | 52 (57.1%) | 85 (70.8%) | 151 (85.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −21.0 (−32.0, −6.0) | −14.5 (−23.5, −8.0) | −16.0 (−29.0, −8.0) | −28.0 (−40.0, −15.0) | <0.0001 |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 28 | 91 | 120 | 177 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 15 (53.6%) | 48 (52.8%) | 84 (70.0%) | 142 (29.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −12.0 (−24.8, −8.0) | −14.9 (−21.4, −7.9) | −11.4 (−22.0, −5.9) | −20.2 (−32.2, −12.0) | <0.0001 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 28 | 91 | 120 | 177 | |

| N with increase (% with reduction) | 13 (46.4%) | 42 (46.2%) | 62 (51.7%) | 90 (50.9%) | 0.47 |

| Median increase (25th, 75th %-iles)** | 5.4 (4.3, 7.4) | 7.0 (3.6, 10.4) | 4.7 (2.5, 8.0) | 6.7 (2.6, 11.1) | 0.84 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 28 | 91 | 120 | 177 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 15 (53.6%) | 46 (50.6%) | 74 (61.7%) | 127 (71.8%) | <0.001 |

| Median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −16.0 (−29.0, −5.0) | −18.0 (−34.0, −11.0) | −17.5 (−47.0, −7.0) | −48.0 (−80.0, −21.0) | <0.0001 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 28 | 91 | 120 | 177 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 15 (53.6%) | 52 (57.1%) | 80 (66.7%) | 132 (74.6%) | 0.001 |

| Median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −5.0 (−9.0, −3.0) | −5.0 (−8.0, −3.0) | −6.0 (−8.5, −4.0) | −8.0 (−11.0, −4.5) | <0.001 |

| Insulin (μU/ml) | 28 | 91 | 120 | 177 | |

| N with reduction (% with reduction) | 15 (53.6%) | 52 (57.1%) | 84 (70.0%) | 146 (82.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Median reduction (25th, 75th %-iles)** | −2.5 (−2.9, −0.8) | −3.1 (−4.7, −1.5) | −3.7 (−6.4, −2.2) | −5.9 (−9.0, −2.8) | <0.0001 |

| Fitness (ml/mg/min) | 30 | 93 | 120 | 173 | |

| N with increase (% with increase) | 14 (46.7%) | 70 (75.3%) | 93 (77.5%) | 163 (94.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Median increase (25th, 75th %-iles)** | 1.7 (0.9, 3.7) | 2.8 (1.1, 4.5) | 4.1 (2.1, 5.6) | 6.2 (3.8, 9.2) | <0.0001 |

The Cochran-Armitage trend test was used to test whether there was a trend in the proportion with a change in the outcome by the ordinal weight change variable. The Jonckheere-Terpstra trend test was used to test whether there was a trend in the magnitude of change in the outcome by the ordinal weight change variable only among those with some change.

Data represent that change for those designated to have a reduction or increase in the specified variable.

Ordinal weight change categories were created by applying clinically meaningful cut points to the continuous weight change measure.

Excluding bone mass.

Baseline Predictors of Weight Change

Associations between baseline factors and 6-month percent weight change are shown in Table 6. Being male, white, and having at least a college education were significantly related to greater percent weight loss at 6 months, than females, non-whites, and less than college education, respectively, when sociodemographic characteristics were considered (model 1). Baseline BMI was not significantly associated with percent weight loss when added to the model (model 2), nor were baseline physical activity and dietary intake parameters (model 3). In the final baseline predictors model (model 3), only sex and race were statistically associated with percent weight loss.

Table 6.

Baseline factors related to six month percent weight change* in young adults in a behavioral weight loss intervention.

| Model 1: Socio-demographic Characteristics | Model 2: Plus Body Mass Index | Model 3a: Plus physical activity and dietary intake | Model 3b: Plus physical activity and dietary intake | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Beta* | P-value | Beta* | P-value | Beta* | P-value | Beta* | P-value |

| Age (per 10 years) | −1.82 | 0.054 | −1.64 | 0.08 | −1.40 | 0.15 | −1.43 | 0.14 |

| Sex (reference=female) | −2.09 | 0.004 | −1.95 | 0.001 | 1.92 | 0.01 | 1.78 | 0.02 |

| Hispanic (reference=no) | 0.11 | 0.94 | 0.13 | 0.93 | 0.10 | 0.95 | 0.10 | 0.95 |

| Race (reference=non-white) | −3.08 | 0.0002 | −3.12 | 0.0002 | 2.69 | 0.002 | 2.69 | 0.002 |

| Education (reference=< college degree) | −1.66 | 0.04 | −1.82 | 0.02 | −1.43 | 0.08 | −1.44 | 0.08 |

| Employment (reference= full time) | −1.03 | 0.20 | −1.08 | 0.18 | −0.83 | 0.31 | −0.86 | 0.29 |

| Student (reference=not a student) | −0.16 | 0.84 | −0.13 | 0.87 | 0.002 | 1.00 | 0.009 | 0.99 |

| Marital status (reference=married/like married) | −0.46 | 0.52 | −0.53 | 0.46 | 0.67 | 0.36 | 0.68 | 0.34 |

| Children in home (reference=yes) | −0.55 | 0.49 | −0.60 | 0.45 | −0.97 | 0.24 | −0.93 | 0.26 |

| Household income (reference=<$25,000) | −1.88 | 0.06 | −1.79 | 0.08 | −1.66 | 0.11 | −1.66 | 0.11 |

| Model 2 addition | ||||||||

| BMI, per 5 kg/m2 | −0.64 | 0.10 | −0.80 | 0.07 | −0.80 | 0.058 | ||

| Model 3 additions | ||||||||

| Sedentary: % of monitor wear time (per 10%) | −1.40 | 0.19 | −1.88 | 0.13 | ||||

| LPA (per 180 MET-minutes/week) | −0.29 | 0.09 | −0.35 | 0.051 | ||||

| Total MVPA (per 180 MET-minutes/week) | −0.08 | 0.40 | ||||||

| ≥10 minute sessions of MVPA (per 180 MET-minutes/week) | −0.05 | 0.61 | ||||||

| Dietary intake (per 250 kcal/day) | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.10 | ||||

| % calories protein (per 5%) | −0.45 | 0.39 | −0.44 | 0.40 | ||||

| % calories fat (per 5%) | −0.24 | 0.32 | −0.24 | 0.32 | ||||

MET: metabolic equivalent; LPA: light-intensity physical activity (1.5 to <3.0 METs); MVPA: moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (≥3.0 METs).

Negative value indicates higher percent of weight loss.

Intervention Predictors of Weight Change

Associations between intervention adherence and changes in sedentary behavior, physical activity, and dietary intake with weight loss at 6 months are shown in Table 7. A greater percentage of intervention sessions completed (p=0.003) and diaries returned (p=0.0003), increases in MET-minutes/week of LPA (p=0.046) and MVPA completed in sessions at least 10 minutes in duration (p=0.004), and decreases in daily calories (p=0.04) and percentage of calories consumed as dietary fat (p=0.01) were independently related to greater percentage weight loss at 6 months. When change in MET-minutes/week of total MVPA replaced MET-minutes/week of MVPA completed in sessions at least 10 minutes in duration, MVPA was no longer significantly related to percent weight loss (p=0.13).

Table 7.

Adjusted associations between intervention participation and change in physical activity and dietary intake and six month percent weight change**.

| Model* (includes ≥10 minute sessions of MVPA) |

Model* (includes total MVPA) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta** | P-value | Beta** | P-value | |

| Percentage of intervention contacts completed (per 10% of intervention contacts completed) |

−0.74 | 0.003 | −0.72 | 0.004 |

| Percentage of intervention diaries returned (per 10% of intervention diaries returned) |

−0.58 | 0.0003 | −0.64 | <.0001 |

| Physical Activity Variables | ||||

| Decrease in percentage time sedentary (per 10% decrease) |

1.21 | 0.20 | −0.16 | 0.89 |

| Increase in LPA (per 180 MET-minutes/week increase) |

−0.32 | 0.046 | −0.15 | 0.34 |

| Increase in total MVPA (per 180 MET-minutes/week increase) |

— | — | −0.10 | 0.13 |

| Increase in ≥10 minute sessions of MVPA (per 180 MET-minutes/week increase) |

−0.21 | 0.004 | — | — |

| Dietary Intake Variables | ||||

| Decrease in energy intake (per 250 kcal/day decrease) |

−0.28 | 0.04 | −0.25 | 0.07 |

| Decrease in % protein calories (per 5% decrease) |

0.91 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.053 |

| Decrease in % fat calories (per 5% decrease) |

−0.59 | 0.01 | −0.55 | 0.02 |

MET: metabolic equivalent; LPA: light-intensity physical activity (1.5 to <3.0 METs); MVPA: moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (≥3.0 METs).

Controlling for intervention group and baseline age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, employment, household income, student status, marital status, children, body mass index, percentage time sedentary, LPA MET-min/week, MVPA MET-min/week in ≥10 minute sessions, caloric intake, % calories from protein and % calories from fat.

Negative value indicates higher percent of weight loss.

Discussion

Young adults are responsive to an in-person, group-based behavioral weight loss intervention. The median weight loss of 8.8% is comparable to the weight loss observed across a broader age range,(3) and it exceeds the magnitude that has been shown to result in health improvements.(3) The weight loss achieved was accompanied by reductions in fasting blood lipids, glucose, insulin, and resting heart rate and blood pressure, and increased cardiorespiratory fitness.

This study of young adults supports that a dietary intervention should focus on reductions in total energy intake and percent dietary fat to achieve weight loss. This study also shows that more MVPA performed in bouts that were at least 10 minutes in duration was associated with greater weight loss. This should be an important intervention target, because total MVPA was not predictive of weight loss, and this has recently been observed in another large trial.(27) Sedentary behavior was also not predictive of weight change, which may suggest that solely targeting this component of physical activity limits the impact on body weight.

MVPA performed in bouts of ≥10 minutes increased from approximately 100 min/wk to 214 min/wk, and there was a reduction in sedentary behavior. Why the intervention did not result in an increase in total MVPA is not clear. Widely accepted MET levels were used to define LPA and MVPA, and it is possible that use of these MET levels leads to classification error when defining LPA or MVPA in young adults. Participants may not have consistently achieved ≥3.0 METs when engaging in what they perceived to be MVPA, resulting in some of this activity being classified as LPA. Moreover, despite the use of objective methods to assess physical activity, there may been measurement error due to the instrumentation when assessing physical activity in this study. This study also did not exclude participation based on level of physical activity at baseline. In fact, 34.2% of participants were engaging in at least 150 min/wk of physical activity at baseline, which may have influenced further adoption of physical activity in some of the study participants. Thus, a more extensive analysis of the data is warranted to understand how physical activity was impacted by this intervention in young adults.

Despite the observed increase in MVPA performed in bouts of ≥10 minutes, there was no significant change in HDL cholesterol. The lack of an increase in the presence of an increase in MVPA is consistent with clinical guidelines that concluded that there is no consistent effect of physical activity on change in HDL cholesterol.(28)

Young adults engaged in the behavioral weight loss intervention over the period of 6 months. Retention was 90%, and after correcting for those who could not complete the intervention due to pregnancy or geographical relocation the retention rate was 93%. These rates of intervention engagement and retention are similar to what has been shown in studies that have not specifically targeted adults 18 to 35 years of age.(7, 29)

There are limitations to this study. Physical activity and diet were assessed at baseline and 6 months, and these data may not be representative of activity and dietary patterns across the entire intervention period in this sample of young adults. This study did not include a no treatment control group, which limits the ability to understand the full influence of the intervention on the study outcomes. Data were not available to determine the cost of the intervention or whether cost may impact generalizability or implementation within a clinical or community-based setting.

In conclusion, a 6-month group-based behavioral intervention resulted in weight loss and improved other health outcomes in young adults. Important intervention components included reductions in energy and dietary fat intake, and increased MVPA performed in bouts with a duration of at least 10 minutes. Thus, this lifestyle intervention can be an effective approach for weight loss in young adults.

What is already known about this subject

Overweight and obesity are significant public health concerns in the United States. Young adults are not immune to being overweight or obese, with current population-based data estimating that 60.3% of 20–39 year old adults meet the clinical classifications for overweight or obesity.

Intensive in-person (group-based) behavioral interventions have been shown to be effective for weight loss for adults and older adults. However, few large-scale studies have been conducted to examine the weight loss achieved with this type of intervention in young adults.

What this study adds

This is one of the few large (N=470) clinical intervention trials to describe the effect of a standard in-person group-based behavioral intervention of weight loss and other health outcomes in young adults. Thus, a group-based lifestyle intervention can be an effective approach for weight loss and related health improvements in young adults.

This study examined components of the intervention that were predictive of weight loss. Results support that a dietary intervention should focus on reductions in total energy intake and percent dietary fat to achieve weight loss. This study also shows that more moderate-to-vigorous physical activity performed in bouts of at least 10 minutes in duration is associated with greater weight loss. Sedentary behavior was not predictive of weight loss. This informs behavioral targets for weight loss in young adults.

This study reports associations between baseline factors and 6-month percent weight change. Being male, white, and having at least a college education were significantly related to greater percent weight loss at 6 months, than females, non-whites, and less than college education, respectively. Baseline BMI, baseline dietary intake parameters, and baseline physical activity were not significantly associated with percent weight loss.

Behavioral Lesson Delivery and Content.

Each group visit focused on a specific behavioral topic related to weight loss, eating, or physical activity. Discussion related to this topic was facilitated by the interventionist, and interactive group participation was encouraged. The interventionist was trained in behavior, nutrition, or physical activity, with their expertise matched with the sessions that were delivered in the group format. Additional details of the general procedures for leading a session and the general content of these sessions is provided below.

General Procedures for Leading a Group Session

-

Every class began with a discussion of the previous week and a review of the assignment. Participants were asked to share information about their week.

Discuss successes and barriers.

Each participant was asked to think of at least one thing he/she is proud of or went well this past week, and participants were invited to share this with the group if they were comfortable doing so.

Participants were asked to think of barriers or an area they feel needs some attention, and participants were invited to share this with the group if they were comfortable doing so.

Include topics of specific concern, i.e.: planning for and feedback after holidays, football, hockey, and/or baseball season, vacation, changes in weather, etc.

Address any questions/concerns about the previous week.

The goal was to make the group meetings as interactive and participant-driven as possible.

Each week the interventionist distributed the Session handout and accompanying Key Card that included the “take home” points of the session.

General Topics of the Group Intervention Sessions

-

Introductory Sessions

Introducing the weight loss process

Establishing the process of the group session

Process of self-monitoring and evaluating your progress

-

Behavioral Related Sessions (these also are incorporated into the nutrition and physical activity sessions listed below)

Goal setting

Motivation

Barrier identification

Problem solving

Thoughts

Mindfulness

Self-efficacy

Stimulus control

Relapse prevention

Stress management

Antecedents and consequences

Social support

-

Nutrition/Diet Focused Sessions

Energy balance

Portion sizes

Diet Quality

Beverage considerations for energy balance and weight loss

Eating away from home

Smart snacking

Satiety vs. Hunger

-

Physical Activity Session Topics

The importance of physical activity for weight loss

Contribution of physical activity to energy balance

Developing and implementing a structured physical activity program

Sessions to increase physical activity variety and self-efficacy for physical activity engagement (e.g., resistance exercise, circuit training, group exercise classes, yoga)

Standardizing Delivery of the Intervention

Weekly intervention staff meetings were conducted to discuss session content and the delivery of the session content.

Sessions were periodically observed by senior staff and investigators to monitor quality control.

A guide was provided to standardize how a session was to be delivered by the intervention staff.

Acknowledgments

We recognize the contribution of the staff and graduate students at the Physical Activity and Weight Management Research Center and the Epidemiology Data Center at the University of Pittsburgh for their assistance.

Funding: Supported by the National Institutes of Health (U01HL096770) and the American Heart Association (12BGIA9410032)

Disclosures: Dr. Jakicic received an honorarium for serving on the 2015 Scientific Advisory Board for Weight Watchers International, and was the Principal Investigator on a grant to examine the validity of activity monitors awarded to the University of Pittsburgh by Jawbone, Inc. Dr. Rogers is the Principal Investigator on a grant awarded to the University of Pittsburgh by Weight Watcher International. Dr. Gibbs is the Principal Investigator on a grant awarded to the University of Pittsburgh by Humanscale.

Footnotes

Clinical Trials Registration: clinicaltrials.gov NCT01131871

Author Contributions: Conception and design: JMJ, SHB; Data acquisition: JMJ, RJR; Data analysis and interpretation: SHB, AW, WCK, JMJ; Drafting manuscript or critical revision: JMJ, WCK, MDM, KKD, DH, ADR, BBG, RJR, AW, SHB; Obtaining funding: JMJ, SHB, BBG; Administrative, technical, and material support: JMJ, WCK, MDM, KKD, DH, ADR, BBG, RJR, AW, SHB; Supervision: JMJ, SHB

None of the other authors had conflicts of interest to report.

Bibliography

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis CE, Jacobs DR, McCreath H, Kiefe CI, Schreiner PJ, Smith DE, et al. Weight gain continues in the 1990s: 10-year trends in weight and overweight from the Cardia Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:1172–81. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2013;129(25 (Suppl 2)):S102–38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Lang W, Janney C. Effect of exercise on 24-month weight loss in overweight women. Arch Int Med. 2008;168(14):1550–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakicic JM, Rickman AD, Lang W, Davis KK, Barone Gibbs B, Neiberg RH, et al. Time-based physical activity interventions for weight loss: a randomized trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(5):1061–9. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jakicic JM, Tate D, Davis KK, Polzien K, Rickman AD, Erickson K, et al. Effect of a stepped-care intervention approach on weight loss in adults: The Step-Up Study Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2012;307(24):2617–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakicic JM, Wing RR, Butler BA, Robertson RJ. Prescribing exercise in multiple short bouts versus one continuous bout: effects on adherence, cardiorespiratory fitness, and weight loss in overweight women. International Journal of Obesity. 1995;19:893–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakicic JM, Winters C, Lang W, Wing RR. Effects of intermittent exercise and use of home exercise equipment on adherence, weight loss, and fitness in overweight women: a randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(16):1554–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Sherwood NE, Tate DF. Physical activity and weight loss: Does prescribing higher physical activity goals improve outcome? Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(4):684–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Thorson C, Burton LR. Use of personal trainers and financial incentives to increase exercise in a behavioral weight loss program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:777–83. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Look AHEAD Research Group. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1374–83. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wing RR, Venditti EM, Jakicic JM, Polley BA, Lang W. Lifestyle intervention in overweight individuals with a family history of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(3):350–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lytle LA, Svetkey LP, Patrick K, Belle S, Fernandez ID, Jakicic JM, et al. The EARLY Trials: A consortium of studies targeting weight control in young adults. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2014;4(3):304–13. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0252-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative centrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18(6):499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakicic JM, Marcus MD, Gallagher KI, Randall C, Thomas E, Goss FL, et al. Evaluation of the SenseWear Pro Armband ™ to assess energy expenditure during exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(5):897–904. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000126805.32659.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.St-Onge M, Mignault D, Allison DB, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Evaluation of a portable device to measure daily energy expenditure in free-living adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:742–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masse LC, Fuemmeler BF, Anderson CB, Matthews CE, Trost SG, Catellier DJ, et al. Accelerometer data reduction: a comparison of four reduction algorithms on select outcome variables. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(11 Suppl):S544–S54. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185674.09066.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller GD, Jakicic JM, Rejeski WJ, Whitt-Glover M, Lang W, Walkup MP, et al. Effect of varying accelerometry criteria on physical activity: the Look AHEAD Study. Obesity. 2013;21(1):32–44. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Hurwitz P, McNutt S, et al. Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires: the Eating at America’s Table Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(12):1089–99. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson FE, Subar AF, Brown CC, Smith AF, Sharbaugh CO, Jobe JB, et al. Cognitive reseearch enhances accuracy of food frequency questionnaire reports: results of an experimental validation study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(2):212–25. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Education Quarterly. 1984;11:1–42. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education Monograph. 1974;2:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, Shermer RL, Renjilian DA, Viegener BJ. Relapse prevention training and problem solving therapy in the long-term management of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:722–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Relapse Prevention. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jakicic JM, Tate DF, Lang W, Davis KK, Polzien K, Neiberg R, et al. Objective physical activity and weight loss in adults: The Step-Up randomized clinical trial. Obesity. 2014;22:2284–92. doi: 10.1002/oby.20830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard J, Hubbard VS, de Jesus JM, Lee IM, et al. AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology American/Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Gallagher KI, Napolitano M, Lang W. Effect of exercise duration and intensity on weight loss in overweight, sedentary women. A randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1323–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.10.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]