Abstract

Anger is among the earliest occurring symptoms of mental health, yet we know little about its developmental course. Further, no studies have examined whether youth with persistent anger are at an increased risk of exhibiting antisocial personality features in adulthood, or how cognitive control abilities may protect these individuals from developing such maladaptive outcomes.

Method

Trajectories of anger were delineated among 503 boys using annual assessments from childhood to middle adolescence (~ages 7–14). Associations between these trajectories and features of antisocial personality in young adulthood (~age 28) were examined, including whether cognitive control moderates this association.

Results

Five trajectories of anger were identified (i.e., Childhood-Onset, Childhood-Limited, Adolescent-Onset, Moderate, and Low). Boys in the Childhood-Onset group exhibited the highest adulthood antisocial personality features (e.g., psychopathy, aggression, criminal charges). However, boys in this group were buffered from these problems if they had higher levels of cognitive control during adolescence. Findings were consistent across measures from multiple informants, replicated across distinct time periods, and remained when controlling for general intelligence and prior antisocial behavior.

Conclusions

This is the first study to document the considerable heterogeneity in the developmental course of anger from childhood to adolescence. As hypothesized, good cognitive control abilities protected youth with persistent anger problems from developing antisocial personality features in adulthood. Clinical implications and future directions are discussed.

Keywords: Anger, Antisocial, Cognitive Control, Development

Anger is a severe and prevalent form of emotion dysregulation wherein even minor provocations elicit responses that range from mild annoyance to rage (Spielberger, 1995). Often arising in response to experiencing frustration, anger is one of the earliest emerging and most commonly occurring mental health symptoms (Hawkins & Cougle, 2011; Watson, 2008). However, despite being one of the most frequently cited pathological emotions (Watson, 2008), existing research into the development of anger is remarkably sparse (Leibenluft, 2013; Stringaris & Goodman, 2009a). Indeed, no study has characterized the developmental course of anger across childhood and adolescence. This is a considerable limitation, particularly as evidence suggests childhood-onset anger that follows a persistent and severe course may increase risk for developing antisocial personality features (Caprara, Paciello, Gerbino, & Cugini, 2007; Deater-Deckard, 2007; Leibenluft, 2013), especially when coupled with poor top-down regulatory capabilties (Siever, 2008). To address these limitations, the current study provides the first investigation into individual differences in developmental pathways of child and adolescent anger. Further, prospective associations with adult antisocial personality features are examined, while also considering the potential moderating influence of top-down cognitive control abilities.

Prior to continuing, a few considerations of terminology often used to describe the construct of anger, as well as its application in the current study are warranted. Although definitions in the literature are varied, most consider anger to be a negatively valenced, approach-oriented construct that emerges in response to negative emotional stimuli (Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009). As an affective phenomenon, it has been described as an emotion (Harmon-Jones, 2004) and mood state (Rusting & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998), while at other times it has been more generally referred to as a temperamental or trait-like characterisitic (Wilkowski & Robinson, 2008). In addition, it is often used interchangeably with terms such as irritabilty and reactive aggression (Blair, 2012; De Pauw & Mervielde, 2010; Drabick & Gadow, 2012); but see (Leibenluft, 2013). Importantly however, psychometric work has demonstrated that measures intended to assess each of these distinct concepts are strongly correlated and likely tap the same underyling construct (Martin, Watson, & Wan, 2000; Wilkowski & Robinson, 2008; Wilkowski, Robinson, Gordon, & Troop-Gordon, 2007). Rather than focusing on more fine grained distinctions (though an unquestionably important area of investigation), it is this more general construct with which the current study is concerned. That said, it should be noted that anger assessed in the current study is construed as being an approach-oriented and negatively valenced construct that is more heavily focused on emotional, as opposed behavioral content (see measures section).

Establishing Longitudinal Invariance

Existing studies focused on continuity and change in anger are sparse, and we are aware of none that have considered fundamental measurement issues such as longitudinal invariance. To convincingly argue that individuals undergo change in some construct (e.g., anger) across development, a critical prerequisite for researchers is to first establish longitudinal measurement invariance. Indeed, this is a central issue across a number of scientific fields, as a lack of invariance can lead to spurious conclusions (Borsboom, 2006; Horn & McArdle, 1992). In brief, longitudinal invariance requires that items on a given measure operate consistently across repeated assessments (Horn & McArdle, 1992). In the absence of invariance, change over time in a construct may result from variations in item functioning, rather than “true” developmental change (Obradović, Pardini, Long, & Loeber, 2007).

Emergence and Developmental Course of Anger

We are aware of only two studies that have examined developmental trajectories of anger or related symptoms. A recent study by Wiggins, Mitchell, Stringaris, and Leibenluft (2014) delineated trajectories of irritability, focusing on emotional (e.g., “stubborn, sullen or irritable,”, “sudden changes in mood or feelings”), rather than behavioral facets of the construct. Study findings demonstrated 5 distinct trajectories of irritability (low decreasing, moderate decreasing, high decreasing, high increasing, stable high) among children assessed at 3, 5, and 9 years of age. In the other study, Caprara et al. (2007) examined irritability, defined by impulsive and aggressive reactivity to frustration, from adolescence into early adulthood (ages 12–20). This study provided evidence of 4 underlying irritability trajectories (low, moderate decreasing, moderate, and stable high).

Importantly, each of these studies were comprised of a small subgroup of individuals displaying childhood-onset symptoms of anger that remained persistently high across development. Accumulating evidence suggests a unique etiological pathway may account for the early emergence and continuity of anger inherent to this childhood-onset subgroup (Caprara et al., 2007). More specifically, research indicates that this developmental trajectory is markedly driven by underlying neurobiological factors, compared to more transient pathways (e.g., adolescent-onset and childhood-limited trajectories) (Caprara et al., 2007; Wiggins et al., 2014). Biological vulnerabilities such as genetically conferred risk and atypical neurocognitive development are considered to exert substantial influence, leading to a rather immutable and severe course of anger (Caprara et al., 2007; Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005; Siever, 2008; Wilkowski & Robinson, 2008).

In addition to a chronically high subgroup, each of these studies also provided evidence of a subset of individuals having initially high levels of anger that dissipated over time. Research suggests that early environmental factors (e.g., trauma, poor parenting) may be play a pivotal role in the early emergence of anger among this subgroup (Caprara et al., 2007; Veenstra, Lindenberg, Verhulst, & Ormel, 2009; Wiggins et al., 2014). In contrast to anger that remains persistently high, symptoms among this pathway remit as individual’s self-regulatory and cognitive control capacities undergo more normative improvement (Caprara et al., 2007; Wiggins et al., 2014). Finally, the principal difference between these two previous studies is the finding of an increasing trajectory among the childhood sample, but not the adolescence to adulthood study. It is perhaps likely that the early increases seen in the childhood sample eventually level-off or even subside into more consistently moderate or even low-level symptoms during later development. In these cases, some individuals may maintain persistently high levels of anger, while others come to demonstrate a pattern more in-line with adolescent-limited types of conceptualizations (Moffitt, 1993).

Although these studies have provided important insights, research into the developmental course of anger that spans across childhood and adolescence remains markedly absent. Indeed, the need for research to address this limitation was highlighted by Wiggins et al. (2014). These authors noted that the increased emergence of psychopathology during this transitional period makes such research essential for identifying individuals most in need of treatment and intervention services.

Antisocial Outcomes and the Influence of Cognitive Control

Anger is a central feature and key DSM criterion of antisocial personality disorder. Yet, little is known about how the presence of anger during early development may predict adult antisocial personality features. Some research indicates that although anger is associatied with antisocial features during earlier periods of development, this relationship may diminish by adulthood (Stringaris, Cohen, Pine, & Leibenluft, 2009). In contrast, other evidence suggests that individuals who experience an early-onset and chronic pattern of anger may be at a particularly high risk for demonstrating adult antisocial features (Boylan, Vaillancourt, & Szatmari, 2012; Broidy et al., 2003; Caprara et al., 2007; Leibenluft, 2013). This parallels a substantial body of research showing that mental health problems that follow a childhood-onset and persistent course lead to heightened risk for a range of deleterious outcomes (Kessler, Amminger, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, & Ustun, 2007; Kessler & Wang, 2008; Kim-Cohen et al., 2003; Post, 2010). To date however, there has been no direct investigation into the relationship between the early developmental course of anger and subsequent features of adult antisocial personality.

Although childhood-onset anger that persists across development may enhance risk for later antisocial features, not all individuals following this trajectory will experience this outcome. Delineating factors that may moderate the link between early anger and subsequent psychopathology has been pointed to as a critical next step for investigators (Leibenluft, 2013). To this extent, evidence suggests that individuals experiencing chronically high anger may confer even greater risk of displaying subsequent antisocial features if they also demonstrate poor cognitive control capabilties (Caprara et al., 2007; Zelazo, 2007).

Cognitive control processes (e.g., response suppression, attentional-set switching, reversal learning) allow for voluntary planned behavior across differing contexts and to varying goals (Luna, Padmanabhan, & O’Hearn, 2010). According to “double-hit” conceptualizations, deficits in cognitive control may further limit an individual’s ability to manage their anger and adapt their behavior in response to frustrating events, serving to amplify their engagement in antisocial behaviors (Caprara et al., 2007; Siever, 2008). Importantly, cognitive control has been shown to be widely available by the time individuals reach adolescence (though with continual refinement and specialization into early adulthood) (Luna et al., 2010; Paniak, Miller, Murphy, & Patterson, 1996; Paulsen, Hallquist, Geier, & Luna, 2015; Rosselli & Ardila, 1993). Thus, among persons demonstrating chronic anger problems, those who also exhibit poor cognitive control during adolescence (when such functions are largely available at near adult levels), may be at an increased risk for demonstrating a severe pattern of antisocial behaviors into adulthood.

Current Study

The current study investigated 1) developmental pathways of anger among boys (n = 503) from childhood to adolescence (ages ~7–14); 2) the association between these pathways and adult antisocial personality features; and 3) the moderating influence of cognitive control. It was hypothesized that a relatively small group of youth would exhibit a childhood-onset course of anger that remained high across development. Individuals exhibiting this pattern of anger were hypothesized to be at particularly increased risk for adult antisocial outcomes if they did not demonstrate adequate levels of cognitive control in adolescence.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were 503 boys (40.6% Caucasian; 55.7% African-American) from the youngest cohort of the longstanding Pittsburgh Youth Study (PYS). The current study delineated trajectories of anger across 8 annual assessments from childhood (M = 6.90, SD = .55) to middle adolescence (M = 14.01, SD = .55). Of the 503 boys included in the trajectory analyses, 330 took part in a neurobiological substudy during adolescence (M = 16.15, SD = .88), at which time cognitive control abilities were assessed. Antisocial personality outcome data was collected during adulthood follow-up assessments (M = 28.54, SD = 2.58), and was available for 88% (n =289) of participants (see “Missing Data” section). All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh. Written informed consent was obtained from parents and/or youth prior to each assessment. (Further details regarding the study sample can be found in Supplement 1 and Loeber, Farrington, Stouthamer-Loeber, and Van Kammen (1998).

Measures

Descriptive information for studies measures is provided in Table S1.

Anger

An extended version of the Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986) was used to assess anger. Four items from this measure were used to index participants’ tendency to experience anger and have difficulties managing their emotional reactivity (e.g., “easily frustrated,” “stubborn, sullen or irritable,” “temper tantrums,” “sudden changes in mood or feelings”). Past research using these items to assess anger provides evidence in support of construct validity (Kim, Mullineaux, Allen, & Deater-Deckard, 2010; Stringaris A1, 2013; A. Stringaris & R. Goodman, 2009a, 2009b). Items were rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true), with the items being summed to create a total anger score. The internal consistency of this measure was high across each of the eight follow-up assessments in the current study (α’s range = .82–.90).1

Prior research suggests that using teacher reported ratings of these items may provide several benefits (Kim et al., 2010). Specifically, when measured over time, it provides a characterization of children’s typical pattern of behavior using multiple changing informants, eliminating any informant-specific response biases2. This is particularly important as the use of a single informant can result in shared method variance and lead to inflated associations between aspects of temperament and prospective outcomes in developmentally focused research (Sanson, Hemphill, & Smart, 2004). Second, the school environment is a setting where youth face situations that often elicit frustration and anger, including dealing with peer provocation, authority figures, and increasing academic demands. Teacher informants provide valuable insight into the developmental course of anger while taking into account this important context-specific information (Kim et al., 2010; Mangelsdorf, Schoppe, & Buur, 2000)

Cognitive Control

Cognitive control was assessed using a computerized version of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST; Heaton, 1993). This task has been used extensively to measure aspects of executive functioning in both clinical practice and research (Lezak, 2004). During the task, participants sort 64 cards according to changing matching rules (i.e., color, shape, or number). Participants must learn the matching rule by trial and error as the computer provides feedback about the correctness of their responses. After 10 consecutive correct responses, the sorting rule changes without the participant’s knowledge, which then requires the participant to identify the new sorting rule. Number of perseverative errors was the outcome of interest, as perseverative responding has been linked to frontal lobe dysfunction and is considered to tap into multiple facets of cognitive control abilities (e.g., response supression, reversal learning, set shifting; Heaton, 1993; Lezak, 2004).

Adult Outcomes (Age 28)

Anger and Physical Aggression

The Anger and Physical Aggression subscales from the Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ; Buss & Perry, 1992) were used to assess these features in adulthood. Items on this measure are rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (“never or hardly applies to me”) to 5 (“very often applies to me”). The seven item Anger subscale of the BPAQ was used as an index of adult anger as it contained items similar in content to those found in the teacher-report measure administered in the current study (e.g., “When frustrated, I let my irritation show”; “I have trouble controlling my temper”). In contrast, the Physical Aggression subscale consists of nine items that are associated with harming others and destroying objects when angry or provoked (e.g., “Given enough provocation, I may hit another person”; “I have become so mad that I have broken things”). Severe aggression is a feature of antisocial and psychopathic personality disorder (i.e., poor behavioral control, criminal versatility) in adulthood. The internal consistencies for the Anger (α = .79) and Physical Aggression (α = .77) subscales were acceptable.

Psychopathic Personality

Psychopathic personality features were assessed using the short-form of Self-Report Psychopathy scale (SRP-III; Paulhus, Neumann, & Hare, in press). This scale consists of 28 items assessing participants’ general tendency to be callous/unemotional, deceitful/manipulative, impulsive/irresponsible, and engage in an antisocial lifestyle (e.g., “I never feel guilty over hurting others”; “I’ve often done something dangerous just for the thrill of it”). Each item is rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (“disagree strongly”) to 5 (“agree strongly”), with items being summed to create a total psychopathy score. This measure has been shown to exhibit convergent validity, as well as predict future criminal offending in young adult males (Neumann, 2012). The internal consistency of total score was high in the current study (α = .92). Additional analyses examining associations with SRP facet level data are provided in the online supplementary tables.

Antisocial Personality Disorder

Symptoms of antisocial personality disorder were assessed using the Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Fourth Edition (C- DISC-IV; Helzer & Robins, 1988). The CDIS-IV is a structured interview that uses a series of standardized probes and follow-up questions to gather information about DSM-IV disorder symptoms participants. It has demonstrated evidence of reliability and construct validity in previous investigations (for a review, see Malgady, Rogler, & Tryon, 1992). As part of the CDIS-IV, participants self-reported on adult symptoms of ASPD (e.g., deceitfulness, lack of remorse, anger, and aggressiveness). A negative binomial model was employed in analyses using this outcome due to the count nature of this variable. Estimates are provided as predicted mean counts.

Adult Criminal Charges

Official criminal records were used to assess total number of adulthood (i.e., after age 18) criminal charges (besides minor traffic offenses). Records were gathered from the Pennsylvania (PA) State Police and the Federal Bureau of Investigation for charges that occurred out of PA. These records reflect charges until February, 2012, at which time participants were an average of 31-years-old.

Control Variables (Age ~ 16)

Several variables collected at the time of the cognitive control follow-up assessment (~ 16-years of age) were used as control variables in the current study.

Demographics

Participants completed questionnaires that provided information regarding their age and race/ethnicity.

IQ

Full-scale IQ was estimated using the Vocabulary, Information, Block Design, and Picture Completion subtests of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC–III; Wechsler, 1991). The WISC-III is a widely used measure of general intelligence for children aged 6–16.

Aggressive Behavior

The Reactive–Proactive Aggression Questionnaire (Raine et al., 2006) subscales were used to assess early aggression. This self-report instrument consists of 12 items indexing proactive aggression and 11 items measuring reactive aggression. Each item is scored based on frequency of occurrence, using a 3-point scale (0 = never to 2 = often). The internal consistencies for the reactive (α = .84) and proactive (α = .85) aggression scales were high.

Early Psychopathic Features

Early features of psychopathy were assessed using the 41-item parent report Childhood Psychopathy Scale (CPS; Lynam, 1997)). The 41-item CPS was originally developed to identify Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL–R; Hare, 2003) personality characteristics during childhood and adolescence. The CPS includes 2- to 4-item scales used to operationalize 12 of the 20 PCL-R items. Three items on the CPS scale (“easily frustrated,” “temper tantrums,” “sudden changes in mood or feelings”) were removed due to their overlap with items used to assess anger. There were no differences in study results dependent on the inclusion or exclusion of these items from the CPS. The internal consistency for the total CPS score was high (α = .91).

Prior Charges

Official records of charges concurrent with and prior to the cognitive control assessment were collected. All juvenile records were collected from the Allegheny County Juvenile Court’s and the Pennsylvania Juvenile Court Judges’ Commission.

Data Analytic Plan

Initial analyses were conducted to assess the longitudinal measurement invariance of the anger construct across the study period. This included assessing factor structure of the anger measure separately at each measurement period. Next thresholds and loadings of the same item was constrained to equality across each different assessment point. This model was then compared to a model wherein thresholds and loadings for each item were free to vary across time (Horn & McArdle, 1992). The relative fit between these competing nested models was examined via a corrected chi-square difference test for weighted least squares estimation using the DIFFTEST procedure in Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). However, as the chi-square difference test has been shown to be sensitive to sample size and violations of normality (Brannick, 1995), a second method for comparing nested models based on absolute fit indices in invariance testing was implemented. Specifically, changes in CFI equal to or less than .01, and changes in RMSEA of equal to or less than .015, have been proposed as demonstrating evidence metric invariance (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). (For a more thorough review of the steps conducted as part of this procedure see (Hawes, Mulvey, Schubert, & Pardini, 2014).

Latent Class Growth Analysis (LCGA) was used to identify trajectories of anger from childhood to adolescence using Mplus 7.0 software. LCGA is a person-centered method that identifies latent subgroups of individuals who follow similar developmental trajectories (Jung & Wickrama, 2007). Models were specified using maximum likelihood estimation with standard errors and a chi-square statistic that is robust to non-normality, which allows for missing data under the assumption it is missing at random. The best class solution was chosen based on classification accuracy (Muthen, 2004), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; Schwarz, 1978), the Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT; Feng & McCulloch, 1996) interpretability, and parsimony. Individuals were assigned to their most likely class using their posterior probability of group membership.

Subsequent to the LCGA analyses, main effects and interactions between anger trajectory groups and cognitive control scores predicting each adulthood outcome were examined using the generalized linear model (GZLM) function in SPSS version 20 (IBM, 2011). In line with study hypotheses, the primary analyses focused on contrasting the Childhood-Onset group with each of the additional trajectory groups. Significant interactions were probed by inspecting adulthood outcome scores among the anger subgroups at low (−1 SD), moderate (mean), and high levels (+1 SD) of cognitive control. In accordance with current best practices (Simmons, Nelson, & Simonsohn, 2011), results are presented with covariates included and excluded from all analyses. Study control variables are discussed further in the measures section above.

Missing Data

Of the 503 individuals in the overall sample, 330 were included in the cognitive control follow-up study (at ~age 16). No significant differences were found in the composition of anger trajectory groups when including the full sample (n =503) compared to when using only indivdiuals in the substudy (n=330; see results section). Among the 330 individuals included in the follow-up substudy, 289 had adulthood outcome data available (at ~age 28). No differences on any demographic or control variables were found between those individuals included in the substudy who had available outcome data (n=289) and those participants included in the substudy, but missing data for the outcome assessment (n=41). Among all individuals having available outcome data, there were no differences on any adulthood outcomes between individuals included in the substudy (n=289) or those from the original overall sample who were not included in the substudy (n=110). When predicting adulthood outcomes, only the 289 substudy participants with complete data were included. No differences on anger scores at any assessment wave or for any demographic variable were found between those individuals included in the substudy who had available outcome data (n=289) compared to all other participants from the original sample (n=214).

Results

To investigate longitudinal invariance of the anger construct across the study period, a baseline configural model was initially specified. This model consisted of the unidimensional anger construct being fit at each assessment wave, and item loadings and thresholds allowed to vary across time. The baseline model provided a good fit to the data (χ2 = 538.98, df = 436, p < .001; CFI = .994, TLI = .994, RMSEA = .022). Next, a more parsimonious metric invariance model was specified that constrained loadings and thresholds of identical items to remain equivalent across all assessment waves. As with the configural model, the metric invariance model revealed excellent fit (χ2 = 589.67, df = 478, p < .001; CFI = .994, TLI = .994, RMSEA = .022).

There were no differences in the absolute fit indices of these 2 models, although the chi-square difference test did produce a marginially significant difference (χ2 = 59.04, df = 42, p = .042). However, as previously discussed in the methods section, the chi-square difference test has been shown to be overly sensitive to model rejection (Brannick, 1995; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). Therefore, in conjuction with the lack of any substantive change noted among absolute fit indices of the configural and metric invariance models, these results were considered to support longitudinal invariance of the the anger construct.

Latent Class Growth Analysis

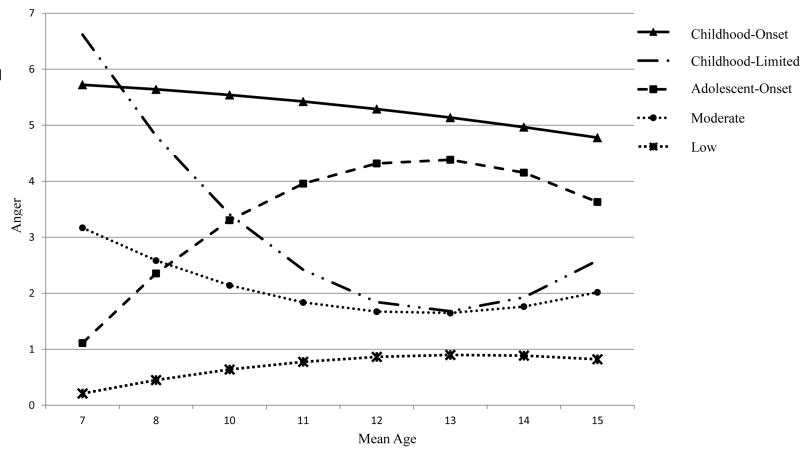

Results from the unconditional growth model revealed the inclusion of a quadratic slope factor improved upon the linear model (Satorra-Bentler: Δχ2 (4) =30.43) and resulted in good overall fit (χ2(27) =38.88, p=.064; CFI=.983; RMSEA=.030). A 5-class LCGA solution emerged as optimal based on model fit indices and entropy values (see Table S2), while also producing theoretically meaningful groups (see Figure 1; “Childhood-Onset” (n=38; 7.2%), “Childhood-Limited” (n=28; 5.5%), “Adolescent-Onset” (n=96; 19.1%), “Moderate” (n=54; 10.7%), “Low” (n=286; 56.9%). As an extra precaution, trajectory groups were also modeled using only the 330 individuals included in the cognitive control follow-up. Results from these analyses were nearly identical: “Childhood-Onset” (n=26; 7.9%), “Childhood-Limited” (n=21; 6.4%), “Adolescent-Onset” (n=61; 18.5%), “Moderate” (n=29; 8.8%), and “Low” (n=193; 58.5%).

Figure 1.

Trajectories of Anger Across Childhood and Middle Adolescence

Anger Trajectories and Cognitive Control Predicting Adult Outcomes

Main effects and interactions of anger dysregulation trajectory group and cognitive control as predictors of adult antisocial personality outcomes are presented in Table 1. There was no main effect of cognitive control predicting any outcome. In contrast, anger trajectory group predicted adulthood physical aggression, anger, and total criminal charges, but not adult psychopathic or antisocial personality. The mean score on each of the adulthood outcomes for each anger trajectory group is provided in Table S3.

Table 1.

Main Effects and Interactions of Anger Trajectory Group and Cognitive Control on Adult Antisocial Features

| Physical Aggression | Anger | Psychopathy | ASPD | Charges | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | p-value | χ2 | df | p-value | χ2 | df | p-value | χ2 | df | p-value | χ2 | df | p-value | |

| Step1 | |||||||||||||||

| Trajectory Group | 14.64 | 4 | 0.005 | 15.46 | 4 | .004 | 1.36 | 4 | 0.85 | 2.45 | 4 | 0.65 | 10.66 | 4 | 0.03 |

| Cognitive Control | 0.16 | 1 | 0.69 | 0.20 | 1 | .65 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.93 | 1.08 | 1 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.73 |

| Step2 | |||||||||||||||

| Trajectory Group X Cognitive Control | 14.21 | 4 | 0.007 | 9.32 | 4 | .05 | 26.59 | 4 | < .001 | 20.86 | 4 | < .001 | 19.57 | 4 | .001 |

Notes: Above analyses control for participant demographics (age, ethnicity, IQ) and early antisocial features (reactive/proactive aggression, psychopathy, offending) as described in the method and results sections.

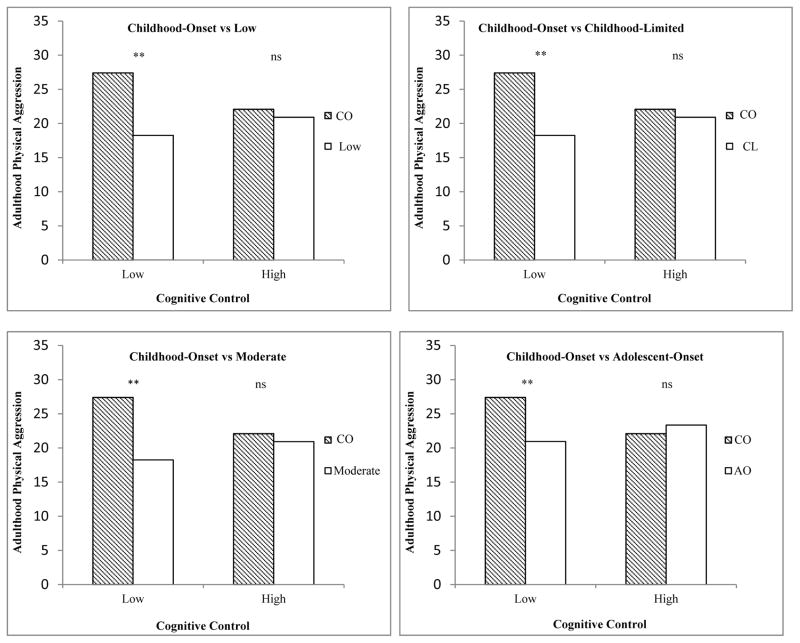

There was a significant interaction between anger trajectory groups and cognitive control for each adulthood outcome (see Table 1)3. Interactions between the Childhood-Onset group and each of the additional trajectory groups were probed separately. Findings demonstrated that at low levels of cognitive control, boys in the Childhood-Onset group were consistently higher on each antisocial outcome compared to the Low, Childhood- Limited, Moderate, and Adolescent-Onset groups. The magnitude of these effects generally ranged from moderate to large (Cohen’s d range = .17 to 1.32; average Cohen’s d = .76). However, at high levels of cognitive control no differences were found between the Childhood-Onset group and any other anger trajectory group on any adulthood outcomes (see Table 2; Figure 2)4. Participant’s demographic (i.e., age, ethnicity, IQ) and early antisocial factors (i.e., aggression, psychopathy, offending) were controlled for in each of these analyses. However, in line with current best practices (Simmons et al., 2011), results are also presented with these controls excluded from the analyses (see Table S5 and Table S6). Study findings remained unchanged after excluding study covariates.

Table 2.

Anger Trajectory Group Scores on Adulthood Outcomes at High, Moderate, and Low Levels of Cognitive Control

| Low (−1 SD Cognitive Control) | Moderate (mean Cognitive Control) | High (+1 SD Cognitive Control) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO Trajectory Mean (SE) | Comparison Trajectory Mean (SE) | Mean Diff | p-value | CO Trajectory Mean (SE) | Comparison Trajectory Mean (SE) | Mean Diff | p-value | CO Trajectory Mean (SE) | Comparison Trajectory Mean (SE) | Mean Diff | p-value | |

| Physical Aggression | ||||||||||||

| CO vs. Low | 27.40 (1.83) | 20.98 (0.66) | 6.41 | .001 | 24.82 (1.10) | 20.81 (0.45) | 4.01 | .001 | 22.09 (1.25) | 20.62 (0.61) | 1.46 | .30 |

| CO vs. CL | 20.06 (1.48) | 7.34 | .002 | 21.98 (1.94) | 2.84 | .20 | 24.01 (2.97) | −1.92 | .55 | |||

| CO vs. Moderate | 18.25 (1.00) | 9.15 | < .001 | 19.54 (1.26) | 5.27 | .001 | 20.92 (1.69) | 1.17 | .57 | |||

| CO vs. AO | 20.95 (.85) | 6.45 | .001 | 22.12 (0.80) | 2.70 | .04 | 23.35 (1.26) | −1.26 | .47 | |||

| Anger | ||||||||||||

| CO vs. Low | 19.04 (1.36) | 13.55 (.59) | 5.49 | < .001 | 16.72 (1.19) | 13.44 (0.40) | 3.27 | .01 | 14.25 (1.54) | 13.33 (0.54) | 0.92 | .57 |

| CO vs. CL | 11.67 (.74) | 7.36 | < .001 | 12.02 (1.12) | 4.69 | .004 | 12.39 (2.08) | 1.86 | .47 | |||

| CO vs. Moderate | 11.92 (.71) | 7.11 | < .001 | 12.21 (.89) | 4.50 | .002 | 12.51 (1.23) | 1.74 | .36 | |||

| CO vs. AO | 14.11 (.88) | 4.93 | .002 | 14.72 (0.80) | 1.99 | .16 | 15.37 (1.23) | −1.11 | .57 | |||

| Psychopathic Features | ||||||||||||

| CO vs. Low | 70.54 (4.22) | 59.14 (1.92) | 11.39 | .01 | 61.54 (3.43) | 57.88 (1.09) | 3.66 | .31 | 52.01 (4.34) | 56.54 (1.50) | −4.53 | .32 |

| CO vs. CL | 55.07 (5.02) | 15.46 | .01 | 59.56 (4.74) | 1.98 | .73 | 64.31 (8.02) | −12.30 | .17 | |||

| CO vs. Moderate | 54.90 (2.05) | 15.63 | .001 | 58.07 (2.43) | 3.47 | .40 | 61.42 (3.15) | −9.41 | .08 | |||

| CO vs. AO | 54.11 (2.54) | 16.43 | .001 | 58.37 (2.06) | 3.16 | .41 | 62.90 (3.44) | −10.89 | .05 | |||

| ASPD | ||||||||||||

| CO vs. Low | 2.85 (0.45) | 2.27 (0.26) | 0.57 | .26 | 2.48 (0.28) | 2.14 (0.15) | .34 | .28 | 2.14 (0.32) | 2.01 (0.21) | 0.13 | .73 |

| CO vs. CL | .96 (0.38) | 1.89 | .001 | 1.86 (0.51) | .62 | .27 | 3.73 (1.87) | −1.58 | .40 | |||

| CO vs. Moderate | 1.37 (0.31) | 1.48 | .006 | 2.45 (0.38) | .03 | .93 | 4.53 (1.13) | −2.38 | .04 | |||

| CO vs. AO | 1.70 (0.29) | 1.15 | .03 | 2.48 (0.24) | .29 | .39 | 2.87 (0.43) | −0.72 | .15 | |||

| Total Charges | ||||||||||||

| CO vs. Low | 16.12 (3.24) | 8.06 (1.38) | 8.05 | .02 | 13.25 (2.44) | 8.04 (.86) | 5.20 | .04 | 10.21 (3.29) | 8.02 (1.24) | 2.18 | .54 |

| CO vs. CL | 6.46 (3.43) | 9.65 | .04 | 6.40 (2.94) | 6.84 | .07 | 6.35 (5.09) | 3.86 | .52 | |||

| CO vs. Moderate | 7.02 (2.31) | 9.09 | .02 | 9.92 (2.33) | 3.32 | .32 | 13.00 (3.31) | −2.78 | .55 | |||

| CO vs. AO | 13.08 (2.35) | 3.03 | .44 | 13.11 (2.44) | .14 | .96 | 13.14 (2.27) | −2.92 | .46 | |||

Notes: CO = Childhood-Onset; CL = Childhood-Limited; AO = Adolescent-Onset; Mean Diff = Mean Difference based on pairwise comparison least significant difference (LSD); Above analyses control for participant demographics (age, ethnicity, IQ) and early antisocial features (reactive/proactive aggression, psychopathy, offending) as described in the method and results sections.

Figure 2.

Graph of the Association between Cognitive Control and Adulthood Outcomes by Anger Trajectory Group

Notes: ** = p < .01; ns = p > .05

Supporting Analyses Examining IQ and Adolescent Antisocial Features

As an additional check, all analyses were re-run using IQ scores in place of cognitive control to determine whether study findings were not better accounted for by more general differences in intelligence. These analyses revealed no significant main or interaction effects of IQ predicting any adult outcome (results available upon request). Further, we also examined if similar main effect and interaction results were found when using trajectory group membership and cognitive control to predict antisocial features in adolescence. These analyses were conducted by treating control variables from our primary analyses (i.e., reactive/proactive aggression, early psychopathic features, prior criminal charges) as outcome variables (still controlling for participant demographics of age, ethnicity, and IQ as done in all primary study analyses. Findings were largely consistent with those found with adult outcomes (see Tables S7–S8). That is, individuals exhibiting Childhood-Onset anger also displayed more antisocial features during adolescence than any other trajectory groups at low, but only at low levels of cognitive control.

Supplemental Analyses: Further Evaluation of the Anger Construct

To examine the psychometric properties of the anger measure, and ensure that the this construct was distinct from other potentially related constructs (conduct problems, interpersonal callousness, hyperactivity/impulsivity, and anxiety), a series of confirmatory factor analytic models were conducted using Mplus 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). The conduct problem, hyperactivity/impulsivity, and anxiety scales each consisted of 5 items and have been rated by clinicians as being very consistent with symptoms of the corresponding scales (Achenbach, Dumenci, & Rescorla, 2003). The 8-item interpersonal callousness scale assesses aspects of the interpersonal and affective features of adult psychopathy in youth (Pardini, Obradovic, & Loeber, 2006). Model fit was assessed using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

The model fit of the anger construct at each of the 8 assessment waves in the current study ranged from acceptable to excellent (CFI’s = .99 – 1.00; TLI’s=.99 – 1.00; RMSEA’s=.03 – .09). Data collected during participant’s screening phase was used to examine a series of CFA models that included the anger construct, as well as the conduct problems, interpersonal callousness, hyperactivity/impulsivity, and anxiety constructs. When all items were examined together, results indicated that a five factor model consisting of separate anger, conduct problems, interpersonal callousness, hyperactivity/impulsivity, and anxiety constructs provided the best fit to the data (CFI = .97; TLI=.96; RMSEA=.04). All items exhibited significant loadings on their respective factors (p’s < .001). Explorations of alternative configurations with items across constructs, loading onto single factors (e.g., anger and hyperactivity-impulsivity; anger and conduct problems) significantly degraded model fit. The estimated variance inflation factor for each predictor was ≤ 2.7, indicating that model parameters were not substantially biased by multicollinearity.

Several additional analyses were conducted to evaluate the degree of potential overlap between the anger construct and conduct problems. At each assessment wave, a two factor model with these items specified to load onto distinct, yet correlated Anger and Conduct Problem constructs was an improvement over a model having these items load onto a single factor as indicated by increases in CFI, decreases in RMSEA and significant chi-square difference tests (see Table S9). Correlations between these Conduct Problems and Anger across each assessment wave ranged from r’s .71–.77, indicating approximately 50% shared variance among these constructs (see Table S10). Finally, analyses were conducted to provide comparisons with similarly specified trajectories of Conduct Problems. A 2-class trajectory appeared to provide the best solution for the Conduct Problem construct (see Table S11 & Figure S1). However, we also present results from a 5-class model since this number of trajectory groups emerged as the best solution for Anger (Figures S2). Analyses indicated that there were no significant interactions between Conduct Problem trajectory groups (using either the 2-class of 5-class solution) and Cognitive Control when predicting the adult antisocial outcomes (see Table S12). In addition, when the models involving Anger were re-run controlling for Conduct Problem trajectory group membership, 4 of the 5 reported interactions remained significant (see Table S13). The only exception was the interaction involving official criminal charges in adulthood (p=.12), although probing of the interaction revealed the same general trend observed for the other adulthood outcomes. Further details regarding these analyses are available upon request.

Discussion

This is the first study to characterize the considerable developmental heterogeneity in boys’ levels of anger from childhood to middle adolescence. It also represents the first study to examine how early manifestations of anger are associated with antisocial personality features in adulthood. Consistent with hypotheses, boys who displayed a Childhood-Onset pattern of anger were at highest risk for exhibiting features of antisocial personality in adulthood (e.g., psychopathic traits, physical aggression, persistent criminal offending), but only if they exhibited poor cognitive control as adolescents.

Stability and Change in Dysregulated Anger across Development

Establishing invariance is exceedingly important, particularly for longitudinal studies, as measures that operate inconsistently across time can lead to distorted and inaccurate conclusions. In the current study, evidence of longitudinal invariance provides added confidence in the study measure and results delineating the developmental course of anger. Although anger is often conceptualized as a stable temperamental trait, current findings indicate that youth who display difficulties regulating their anger are a heterogeneous group. Specifically, nearly half of boys with high levels of anger in early elementary school no longer displayed these problems by middle adolescence. In contrast, approximately twenty percent of boys exhibited features of anger as they transitioned into the teenage years. Importantly youth in this adolescent-onset group were not at increased risk for exhibiting high levels of anger reactivity in adulthood, unlike boys who exhibited problems with anger from childhood into adolescence. Research suggests that atypical neurobiological development may be particularly influential in the development of this rather incalcitrant etiological pathway of childhood-onset anger (Caprara et al., 2007; Siever, 2008; Wilkowski & Robinson, 2008).

Chronic Dysregulated Anger, Cognitive Control, and Antisocial Personality Features

Findings consistently indicated that youth exhibiting childhood-onset anger were at increased risk of displaying features of antisocial personality in adulthood if they exhibited poor cognitive control in middle adolescence. Cognitive control impacts an individual’s ability to regulate emotions and alter behavioral responses (Zelazo, 2007), and often begins to reach adult-like levels during adolescence (Paulsen et al., 2015). Thus, poor cognitive control and regulatory abilities in middle adolescence (when these functions are available at near adulthood levels) may act as a marker of the relationship between a chronic developmental course of anger and future antisocial behaviors. These findings are in line with other research suggesting that increased anger coupled with poor cognitive control can lead to explosive aggression and antisocial behaviors (e.g., Blair, 2012; Caprara et al., 2007; Siever, 2008).

Strengths and Limitations

This study was characterized by a number of strengths including a developmentally focused longitudinal design, the use of multiple informants to assess anger (i.e., different teachers at each annual assessment), multiple sources to measure antisocial personality (i.e., official records, parent-report, self-report), and replication of results across distinct time periods (i.e., replication at age ~16 assessment). However, several limitations should also be noted. The study focused on a community sample of at-risk boys and results may not generalize to girls and more severe clinical populations. Additionally, anger was limited in terms of item content and only collected until middle adolescence. However, it is worth noting that scales with nearly identical item content have been used in prior studies investigating anger in youth. In addition, analyses in the current study also indicated that the items indexed the same construct from childhood to adolescence (i.e., longitudinal invariance). The assessment of cognitive control was based on performance during a single task administered in middle adolescence. As correlations among executive functioning tasks are often low (e.g., Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, et al., 2000), replication of these findings using alternative measures of is critical. Such analyses may provide additional insight into the specific mechanisms underlying the moderation effects demonstrated in the current study. That is, are these findings specific to ‘cognitive control’ as assessed by the WCST, or do they extend to a more generalizable and higher-order factor of executive function, in a similar vein as Miyake and Friedman’s (2012) “Unity” and “Diversity” characterizations. Future work assessing change in cognitive control across development is also necessary. Finally, primary analyses predicting adult antisocial outcomes only included a subset of participants with complete data.

As pointed out by Sher, Jackson, and Steinley (2011), generalizing findings from mixture models should be carried out with caution, and the potential for overextraction of classes should always considered (Bauer & Curran, 2003). Importantly, the trajectory groups delineated in the current study are consistent prior research into the developmental course of anger during childhood (Wiggins et al., 2014) and adolescence (Caprara et al., 2007). Though subgroups were relatively small in some instances, this is expected as such patterns of psychopathology are by their nature atypical. Further, classes were differentiated on study outcomes in theoretically meaningful ways, particularly the Childhood-Onset group. This said, these cautions should be noted and the current results need to be replicated.

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

This is the first study to demonstrate that there is considerable heterogeneity in the developmental course of anger among boys. Findings suggest that youth who exhibit a childhood-onset pattern of anger coupled with poor cognitive control are at particularly high risk for displaying antisocial personality features in adulthood. Future research may wish to examine the effectiveness of programs designed to enhance cognitive control and executive function skills in reducing long-term antisocial outcomes among youth with persistent difficulties regulating their anger.

Supplementary Material

Lay Summary.

Findings from this study highlight important differeneces in the developmental course of anger from childhood to adolescence. Early manifestations of anger were associated with antisocial personality features assessed prospectively in adulthood. Notably, youth exhibiting a pattern of chronic anger beginning in childhood were at particularly high risk for displaying adult antisocial personality features, but only when coupled with poor cognitive control assessed during adolescence.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Grant support provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH51091-01A1, MH094467, MH48890, MH50778, MH078039-01A1); National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA411018); and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (96-MU-FX-0012).

Footnotes

See ‘Supplemental Analyses’ at the end of the results section for a more thorough evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Anger construct used in this study.

It should be noted that teacher assessment was completed by the participant’s current teacher on a yearly basis. Thus, anger was assessed across multiple informants (generally eight different teacher informants) during childhood and adolescence, for each participant.

In addition to the primary study outcomes, we also examined interactions between the anger trajectory groups and cognitive control with the SRP psychopathy measure at the facet level (i.e., Callous, Interpersonal, Erratic Lifestyle, Antisocial). This data is reported as part of the online supplementary information (Tables S4).

Although the current study focused on comparisons with the Childhood-Onset Chronic group, we also compared each of the other 4 trajectory groups with each other separately (i.e., 6 combinations) at the 3 levels of cognitive control (low, moderate, high), for all 5 outcomes. This resulted in a total of 90 comparisons (6×3×5), across which, only three marginally significant differences (.01< p’s <.05) were found. Results available upon request.

References

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the teacher’s report form and teacher version of the child behavior profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA. DSM-oriented and empirically based approaches to constructing scales from the same item pools. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32(3):328–340. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Distributional assumptions of growth mixture models: Implications for overextraction of latent trajectory classes. Psychological Methods. 2003;8:338–363. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair R. Considering anger from a cognitive neuroscience perspective. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science. 2012;3(1):65–74. doi: 10.1002/wcs.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom D. When does measurement invariance matter? Medical care. 2006;44(11):S176–S181. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000245143.08679.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan K, Vaillancourt T, Szatmari P. Linking oppositional behaviour trajectories to the development of depressive symptoms in childhood. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2012:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannick MT. Critical comments on applying covariance structure modeling. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1995;16(3):201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Broidy LM, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE, Bates JE, Brame B, Dodge KA, Vitaro F. Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: a six-site, cross-national study. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(2):222–245. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63(3):452–459. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV, Paciello M, Gerbino M, Cugini C. Individual differences conducive to aggression and violence: Trajectories and correlates of irritability and hostile rumination through adolescence. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33(4):359–374. doi: 10.1002/ab.20192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Harmon-Jones E. Anger is an approach-related affect: Evidence and implications. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(2):183–204. doi: 10.1037/A0013965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Roberts BW, Shiner RL. Personality development: stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:453–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structual Equation Modeling. 2002;9(2):233–255. [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw SSW, Mervielde I. Temperament, personality and developmental psychopathology: A review based on the conceptual dimensions underlying childhood traits. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2010;41(3):313–329. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Petrill SA, Thompson LA. Anger/frustration, task persistence, and conduct problems in childhood: A behavioral genetic analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:80–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabick DA, Gadow KD. Deconstructing oppositional defiant disorder: clinic-based evidence for an anger/irritability phenotype. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(4):384–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng ZD, McCulloch CE. Using bootstrap likelihood ratios in finite mixture models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1996:609–617. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) 2. North Toawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E. On the relationship of frontal brain activity and anger: Examining the role of attitude toward anger. Cognition & Emotion. 2004;18(3):337–361. doi: 10.1080/02699930341000059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes S, Mulvey E, Schubert C, Pardini D. Structural Coherence and Temporal Stability of Psychopathic Personality Features During Emerging Adulthood in Serious Adolescent Offenders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0037078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins KA, Cougle JR. Anger problems across the anxiety disorders: findings from a population–based study. Depression and anxiety. 2011;28(2):145–152. doi: 10.1002/da.20764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtis G. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) manual revised and expanded. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Robins LN. The diagnostic interview schedule: Its development, evolution, and use. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1988;23(1):6–16. doi: 10.1007/BF01788437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn J, McArdle J. A practical and theoretical guide to measurement invariance in aging research. Experimental Aging Research. 1992;18(3–4):117–144. doi: 10.1080/03610739208253916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jung T, Wickrama KAS. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2007;10 [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustun TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Current opinion in psychiatry. 2007;20(4):359. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler &, Wang The Descriptive Epidemiology of Commonly Occurring Mental Disorders in the United States. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:115–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Mullineaux PY, Allen B, Deater-Deckard K. Longitudinal studies of anger and attention span: Context and informant effects. Journal of Personality. 2010;78(3):1091–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E, Stoddard J. The developmental psychopathology of irritability. Development and psychopathology. 2013;25(2):1473–1487. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW, Hannay HJ, Fischer JS. Neuropsychological assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB. Antisocial behavior and mental health problems: Explanatory factors in childhood and adolescence. New York, NY: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Luna B, Padmanabhan A, O’Hearn K. What has fMRI told us about the development of cognitive control through adolescence? Brain and cognition. 2010;72(1):101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR. Pursuing the psychopath: capturing the fledgling psychopath in a nomological net. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(3):425–438. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malgady RG, Rogler LH, Tryon WW. Issues of validity in the Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1992;26(1):59–67. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(92)90016-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf SC, Schoppe SJ, Buur H. The meaning of parental reports: A contextual approach to the study of temperament and behavior problems in childhood. Temperament and personality development across the life span. 2000:121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Watson D, Wan CK. A three-factor model of trait anger: Dimensions of affect, behavior, and cognition. Journal of Personality. 2000;68(5):869–897. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP. The nature and organization of individual differences in executive functions four general conclusions. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2012;21:8–14. doi: 10.1177/0963721411429458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology. 2000;41:49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100(4):674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B. Latent variable analysis. Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. Handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Pardini D. Factor structure and construct validity of the Self-Report Psychopathy (SRP) scale and the Youth Psychopathic Traits inventory (YPI) in young men. Journal of personality disorders. 2012:1–15. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2012_26_063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradović J, Pardini DA, Long JD, Loeber R. Measuring interpersonal callousness in boys from childhood to adolescence: An examination of longitudinal invariance and temporal stability. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36(3):276–292. doi: 10.1080/15374410701441633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paniak C, Miller HB, Murphy D, Patterson L. Canadian developmental norms for 9 to 14 year-olds on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Canadian Journal of Rehabilitation. 1996;9:233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Pardini D, Obradovic J, Loeber R. Interpersonal callousness, hyperactivity/impulsivity, inattention, and conduct problems as precursors to delinquency persistence in boys: A comparison of three grade-based cohorts. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(1):46–59. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus D, Neumann CS, Hare RD. Manual for the Self-Report of Psychopathy (SRP-III) scale. Multi-Health Systems; Toronto, Ontario CA: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen DJ, Hallquist MN, Geier CF, Luna B. Effects of incentives, age, and behavior on brain activation during inhibitory control: A longitudinal fMRI study. Developmental cognitive neuroscience. 2015;11:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Leverich GS, Kupka RW, Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Nolen WA. Early-onset bipolar disorder and treatment delay are risk factors for poor outcome in adulthood. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71(7):864–872. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04994yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Dodge K, Loeber R, Gatzke-Kopp L, Lynam D, Reynolds C, Liu J. The reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire: Differential correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent boys. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32(2):159–171. doi: 10.1002/ab.20115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosselli M, Ardila A. Developmental norms for the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test in 5-to 12-year-old children. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1993;7:145–154. doi: 10.1080/13854049308401516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusting CL, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Regulating responses to anger: effects of rumination and distraction on angry mood. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1998;74(3):790. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanson A, Hemphill SA, Smart D. Connections between temperament and social development: A review. Social Development. 2004;13(1):142–170. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Jackson KM, Steinley D. Alcohol use trajectories and the ubiquitous cat’s cradle: cause for concern? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(2):322–335. doi: 10.1037/a0021813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siever L. Neurobiology of aggression and violence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):429–442. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons JP, Nelson LD, Simonsohn U. False-positive psychology undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological Science. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0956797611417632. 0956797611417632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Reheiser EC, Sydeman SJ. Measuring the experience, expression, and control of anger. Issues in comprehensive pediatric nursing. 1995;18(3):207–232. doi: 10.3109/01460869509087271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris Cohen P, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Adult outcomes of youth irritability: A 20-year prospective community-based study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1048–1054. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris &, Goodman Longitudinal outcome of youth oppositionality: irritable, headstrong, and hurtful behaviors have distinctive predictions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(4):404–412. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181984f30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A1, MB, Copeland WS, Costello EJ, Angold A. Irritable mood as a symptom of depression in youth: prevalence, developmental, and clinical correlates in the Great Smoky Mountains Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(8):831. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R. Longitudinal outcome of youth oppositionality: Irritable, headstrong, and hurtful behaviors have distinctive predictions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009a;48(4):404–412. doi: 10.1097/Chi.0b013e3181984f30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R. Three dimensions of oppositionality in youth. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009b;50(3):216–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra R, Lindenberg S, Verhulst FC, Ormel J. Childhood-limited versus persistent antisocial behavior why do some recover and others do not? The TRAILS study. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29(5):718–742. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, O’Hara MW, Scott S. Hierarchical structures of affect and psychopathology and their implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25(4) doi: 10.1002/da.20496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 3. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins Mitchell C, Stringaris A, Leibenluft E. Developmental Trajectories of Irritability and Bidirectional Associations With Maternal Depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53(11):1191–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkowski BM, Robinson MD. The cognitive basis of trait anger and reactive aggression: An integrative analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2008;12:3–21. doi: 10.1177/1088868307309874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkowski BM, Robinson MD, Gordon RD, Troop-Gordon W. Tracking the evil eye: Trait anger and selective attention within ambiguously hostile scenes. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41(3):650–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo PD, Cunningham WA. Executive Function: Mechanisms Underlying Emotion Regulation. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.