Abstract

Background:

In early 2009, 2 observational studies and a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory addressed the drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and clopidogrel. One study suggested that pantoprazole could be used safely in this setting, whereas the other study and the FDA advisory did not distinguish among PPIs. We examined trends in PPI prescribing among clopidogrel recipients in the period following these events.

Methods:

We conducted a population-based time series analysis of Ontario residents aged 66 years or older for whom clopidogrel was prescribed between Apr. 1, 1999, and Sept. 30, 2013. We determined the proportion of clopidogrel recipients dispensed a PPI during each quarter and the proportions who received pantoprazole or other PPIs. The outcome of interest was change in the use of pantoprazole.

Results:

In the final quarter of 2008, pantoprazole represented 23.7% of all PPI prescriptions dispensed to patients receiving clopidogrel. Following the publications and FDA advisory in early 2009, pantoprazole use increased substantially. By the end of 2009, this medication accounted for 52.5% of all PPI prescriptions issued to patients receiving clopidogrel; by the end of the study period, it accounted for 71.0% of all PPI prescriptions dispensed to such patients (p < 0. 001). We also observed a modest drop in overall PPI use among clopidogrel recipients beginning in early 2009.

Interpretation:

In 2009, the prescribing of PPIs with clopidogrel changed substantially in Ontario, with pantoprazole rapidly becoming the most commonly prescribed agent in its class. However, a modest decline in overall PPI use also occurred that may reflect suboptimal translation of emerging drug safety information to clinical practice.

Clopidogrel is a widely used drug for the treatment of ischemic heart disease and stroke. As a prodrug, its antiplatelet activity is partly dependent on conversion to an active metabolite by cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 2C19.1,2 Over the past decade, several investigators have explored the possibility that some proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) - omeprazole in particular - might inhibit this process, thereby attenuating the effect of clopidogrel. In 2006, Gilard and colleagues3 published the first report describing a potential pharmacodynamic interaction between omeprazole and clopidogrel, a finding that was subsequently confirmed by others.4-6 However, in 2009, Cuisset and colleagues6 showed that the same phenomenon did not occur with pantoprazole, an observation predicted by the fact that pantoprazole does not inhibit cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 2C19.7 This finding was reaffirmed by several other groups,8-12 including Angiolillo and colleagues12 a in a randomized crossover study.

In early 2009, we published an observational study of the clinical consequences of this drug interaction.13 We concluded that, among patients who received clopidogrel following acute myocardial infarction, concomitant therapy with PPIs other than pantoprazole was associated with an increased risk of reinfarction. Five weeks after the online publication of our study, a large observational study was published in which the authors used different methods but reached a similar conclusion.14 These findings were controversial; over the ensuing 2 years they were disputed by other investigators15-17 including Bhatt and colleagues,17 who found in a randomized controlled trial that the combination of omeprazole and clopidogrel was associated with a significantly lower risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage and no increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events. However, the trial's intervention was a proprietary product (CGT-2168) specifically formulated to avoid a pharmacokinetic interaction between clopidogrel and omeprazole, which precluded valid inference about the safety of the drug combination.18

An important finding of our 2009 study was that, whereas PPIs as a class were associated with an increased risk of recurrent myocardial infarction, pantoprazole was not. In the media attention that accompanied our study, we emphasized that patients need not avoid the concomitant use of PPIs with clopidogrel when both drugs were necessary. Rather, when a PPI was indicated, we suggested the preferential use of pantoprazole on the basis of our findings, the known pharmacologic profile of these drugs7 and the findings of Cuisset and colleagues.6 In contrast, an alert issued by the US Food and Drug Administraton (FDA)19 2 days before our publication as well as the large observational study14 published shortly after ours did not distinguish among the PPIs. Indeed, the FDA recommended that "healthcare providers should re-evaluate the need for starting or continuing treatment with a PPI. …"19 Similarly, a Health Canada advisory issued in August 200920 did not distinguish among PPIs.

In the current study, we examined trends in PPI prescribing among clopidogrel recipients in the period following these events.

Methods

Setting

We conducted a population-based cross-sectional study involving Ontario residents aged 66 years or more for whom clopidogrel was prescribed between Apr. 1, 1999, and Sept. 30, 2013. These people had universal access to health care services and prescription drug coverage.

Data sources

We identified prescriptions for PPIs and clopidogrel using the Ontario Drug Benefit program database, which contains comprehensive records of prescription medications dispensed to Ontario residents 65 years of age or older. This database has been shown to be of high validity, with little missing data.21 Patient age was obtained from the Registered Persons Database, which contains demographic information for all Ontarians ever issued a health card. These databases were anonymously linked with the use of encrypted 10-digit health card numbers.

Identification of patients and rates

In each quarter of each calendar year, we identified all patients who received at least 1 prescription for clopidogrel. Patients were excluded if they had invalid identifiers, if their age was unknown, or if they were younger than 66 on the date the clopidogrel was prescribed. Among clopidogrel recipients, we identified those who received any prescription for pantoprazole, omeprazole, rabeprazole, lansoprazole or esomeprazole during the quarter.

Statistical analysis

In each quarter, we calculated the proportion of patients prescribed clopidogrel who also received PPI therapy during that quarter. Analyses were conducted for all PPIs as a group and were then stratified into pantoprazole versus other PPIs (omeprazole, rabeprazole, lansoprazole or esomeprazole).

We used autoregressive integrated moving average models to evaluate changes in quarterly PPI prescribing rates beginning in the first quarter of 2009. We assessed stationarity using the autocorrelation function and the augmented Dickey-Fuller test. The autocorrelation, partial autocorrelation and inverse autocorrelation functions were used to model parameter appropriateness and seasonality. We assessed the presence of white noise by examining the autocorrelation at various lags using the Ljung-Box χ2 statistic. Analyses were conducted with the use of SAS 9.1 software (SAS Institute, Inc.).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto.

Results

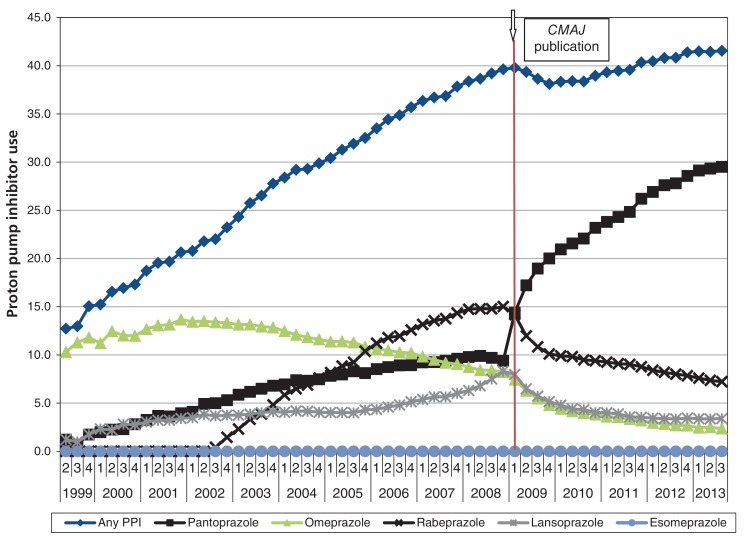

During the 14-year study period, the number of people aged 66 years or more for whom clopidogrel was prescribed during each quarter increased from 330 in the second quarter of 1999 to 83 921 in the third quarter of 2013. Coprescription of a PPI with clopidogrel increased threefold over this period, from 12.7% in early 1999 to 41.6% in September 2013 (Figure 1). In the last quarter of 2008, rabeprazole was the PPI most commonly prescribed with clopidogrel; this reflected its lower cost and preferred status on the Ontario Drug Benefit formulary.

Figure 1.

Coprescription of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) among clopidogrel recipients 66 years of age or older from 1999 to 2013, by quarter and PPI use.

In 2009, a major shift in PPI prescribing patterns occurred: the proportion of clopidogrel recipients who were prescribed pantoprazole increased significantly between the final quarter of 2008 (9.4%) and the final quarter of 2009 (20.0%) (p < 0.001) (Figure 1). This increase was accompanied by a corresponding decrease in the proportion of clopidogrel recipients who were prescribed PPIs other than pantoprazole, from roughly 31.5% in late 2008 to 20.0% in late 2009 (p < 0.001). By the end of 2009, pantoprazole accounted for 52.5% of all PPI prescriptions issued to patients receiving clopidogrel; by the end of the study period, it accounted for 71.0% of all PPI prescriptions dispensed to such patients (p < 0.001).

We also noted a modest decline in the overall prescription of PPIs among patients receiving clopidogrel: in the first quarter of 2010 (1 year after the FDA advisory19 and publication of the 2 observational studies13,14), 38.3% of clopidogrel recipients were also prescribed a PPI.

We conducted a post hoc examination of prescribing patterns among patients receiving a PPI other than pantoprazole with clopidogrel before publication of our observational study.13 We identified 14 318 such patients in the fourth quarter of 2008. In the 6 months following our publication, 10 318 (72.1%) of the 14 318 continued with a PPI other than pantoprazole, 2717 (19.0%) were switched to pantoprazole, and 1283 (9.0%) received no further PPI prescription. Furthermore, 628 (4.4%) of these patients received a histamine H2 receptor antagonist.

Interpretation

We found major changes in the prescribing of PPIs to clopidogrel recipients beginning in 2009, with a substantial increase in the use of pantoprazole and a slight decrease in overall PPI use. We speculate that the shift toward the selective use of pantoprazole in patients taking clopidogrel resulted, in part, from media coverage associated with our 2009 publication,13 because neither the contemporaneous FDA advisory19 nor the subsequent observational study14 distinguished among the available PPIs. Although health care providers rarely receive notice of drug interactions in this way, our findings suggest that rapid and substantial changes in prescribing can occur in response to publications, regulatory warnings and the associated media attention.

It is important to reiterate that recent data clearly indicate that the use of a PPI with clopidogrel reduces the risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage.17 Although the observed decline in overall PPI use in 2009 may reflect appropriate discontinuation of PPI therapy in some patients, it may also reflect misinterpretation of our study (in which pantoprazole's safety was clearly documented) or the wholesale avoidance of PPI therapy on the assumption, by patients or by physicians, of a "class effect," as might have been inferred from a subsequent publication14 or the widely publicized FDA advisory.19 This highlights the importance of clearly communicating within-class differences in drug effects when they exist.

Limitations

The principal limitation of this study was our focus solely on trends in drug use. Because this was an ecological rather than a patient-level analysis, and because it is generally accepted that the interaction between PPIs and clopidogrel is not likely to present a hazard for most patients,22 we did not examine whether the shift in PPI prescribing was associated with differences in clinical outcomes at the population level. In addition, the observed increase in use of pantoprazole may have been influenced by other factors, including the introduction of a new proprietary formulation (Tecta) on the Ontario Drug Benefit formulary in mid-2010 and its heavy marketing to clinicians. This cannot, however, explain the rise in pantoprazole use in 2009 and early 2010. Finally, we have no information regarding the extent to which our results can be generalized to other jurisdictions.

Conclusion

Our study highlighted major changes in the prescribing of PPIs among older patients receiving clopidogrel that occurred following publication of a prominent observational study and an FDA advisory. These findings suggest that publication of observational research and regulatory warnings may influence prescribing behaviour; this response may be both rapid and drug-specific when a clear message is communicated to clinicians and patients. However, the modest decline in overall PPI use that we also observed may reflect suboptimal translation of emerging drug safety information to clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) Drug Innovation Fund and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario MOHLTC. The authors thank Jen Levi for assistance with manuscript preparation and Brogan Inc., Ottawa, for use of their Drug Product and Therapeutic Class Database. The opinions, results and conclusions are those of the authors, and no endorsement by the Ontario MOHLTC or ICES is intended or should be inferred.

Footnotes

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/3/4/E428/suppl/DC1

Competing interests: Muhammad Mamdani has served as an advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Hoffmann-La Roche and Novartis. No competing interests were declared by the other authors.

Contributors: David Juurlink conceived of the study and drafted the manuscript. All of the authors participated in the design, interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. Tara Gomes performed the data extraction, and Muhammad Mamdani performed the time series analysis. All of the authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to be guarantors of the work.

References

- 1.Giusti B, Gori AM, Marcucci R, et al. Cytochrome P450 2C19 loss-of-function polymorphism, but not CYP3A4 IVS10 + 12G/A and P2Y12 T744C polymorphisms, is associated with response variability to dual antiplatelet treatment in high-risk vascular patients. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:1057–64. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f1b2be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt JT, Close SL, Iturria SJ, et al. Common polymorphisms of CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 affect the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic response to clopidogrel but not prasugrel. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2429–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilard M, Arnaud B, Le Gal G, et al. Influence of omeprazol on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated to aspirin. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:2508–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siriswangvat S, Sansanayudh N, Nathisuwan S, et al. Comparison between the effect of omeprazole and rabeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel. Circ J. 2010;74:2187–92. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily JC, et al. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole Clopidogrel Aspirin) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:256–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuisset T, Frere C, Quilici J, et al. Comparison of omeprazole and pantoprazole influence on a high 150-mg clopidogrel maintenance dose: the PACA (Proton Pump Inhibitors And Clopidogrel Association) prospective randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1149–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li XQ, Andersson TB, Ahlström M, et al. Comparison of inhibitory effects of the proton pump-inhibiting drugs omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole on human cytochrome P450 activities. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:821–7. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.8.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siller-Matula JM, Spiel AO, Lang IM, et al. Effects of pantoprazole and esomeprazole on platelet inhibition by clopidogrel. Am Heart J. 2009;157:148.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fontes-Carvalho R, Albuquerque A, Araujo C, et al. Omeprazole, but not pantoprazole, reduces the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel: a randomized clinical crossover trial in patients after myocardial infarction evaluating the clopidogrel-PPIs drug interaction. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:396–404. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283460110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neubauer H, Engelhardt A, Kruger JC, et al. Pantoprazole does not influence the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel - a whole blood aggregometry study after coronary stenting. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2010;56:91–7. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181e19739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuern CS, Geisler T, Lutilsky N, et al. Effect of comedication with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) on post-interventional residual platelet aggregation in patients undergoing coronary stenting treated by dual antiplatelet therapy. Thromb Res. 2010;125:e51–4. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angiolillo DJ, Gibson CM, Cheng S, et al. Differential effects of omeprazole and pantoprazole on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of clopidogrel in healthy subjects: randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover comparison studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:65–74. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Ko DT, et al. A population-based study of the drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMAJ. 2009;180:713–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.082001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2009;301:937–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray WA, Murray KT, Griffin MR, et al. Outcomes with concurrent use of clopidogrel and proton-pump inhibitors: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:337–45. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-6-201003160-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM, et al. Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;374:989–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61525-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatt DL, Cryer BL, Contant CF, et al. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1909–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juurlink DN. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:681–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1013859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Early communication about an ongoing safety review of clopidogrel bisulfate (marketed as Plavix). Silver Spring (MD): US Food and Drug Administration. 2013. [accessed 2015 Sept. 1]. Available www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/ucm079520.htm.

- 20.Potential interaction of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) with Plavix (clopidogrel) - for health professionals. Ottawa: Health Canada. 2009. [accessed 2015 Nov. 6]. Available www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall-alert-rappel-avis/hc-sc/2009/14567a-eng.php.

- 21.Levy AR, O'Brien BJ, Sellors C, et al. Coding accuracy of administrative drug claims in the Ontario Drug Benefit database. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;10:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juurlink DN. Proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel: putting the interaction in perspective. Circulation. 2009;120:2310–2. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.907295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.