Abstract

Objective

Chronic inflammation is associated with cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and psychiatric disorders. The neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) has been investigated as a new biomarker for systemic inflammatory response. The aim of the study is to investigate the relation of NLR with severity of depression and CV risk factors.

Methods

The study population consisted of 256 patients with depressive disorder. Patients were evaluated with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D). Patients were classified into four groups according to their HAM-D score such as mild, moderate, severe, and very severe depression. Patients were also evaluated in terms of CV risk factors.

Results

Patients with higher HAM-D score had significantly higher NLR levels compared to patients with lower HAM-D score. Correlation analysis revealed that severity of depression was associated with NLR in depressive patients (r=0.333, p<0.001). Patients with one or more CV risk factors have significantly higher NLR levels. Correlation analysis revealed that CV risk factors were associated with NLR in depressive patients (r=0.132, p=0.034). In logistic regression analyses, NLR levels were an independent predictor of severe or very severe depression (odds ratio: 3.02, 95% confidence interval: 1.867-4.884, p<0.001). A NLR of 1.57 or higher predicted severe or very severe depression with a sensitivity of 61.4% and specificity of 61.2%.

Conclusion

Higher HAM-D scores are associated with higher NLR levels in depressive patients. NLR more than 1.57 was an independent predictor of severe or very severe depression. A simple, cheap white blood cell count may give an idea about the severity of depression.

Keywords: Depression, Lymphocyte, Neutrophil, Inflammatory, Cardiovascular risk

INTRODUCTION

The rates of depressive disorders have increased all over the world in the recent years. Moreover, the World Health Organization estimates that depression will be the second leading cause of morbidity worldwide in 2020.1,2 Depression has been associated with alterations in the central nervous system, immune response, and vascular reactivity that all of these factors are important in the generation of a systemic inflammatory response.3 Previous studies showed that depression is associated with elevated inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6, and interleukin-1.4,5 A recent study showed that elevated level of CRP is associated with increased risk of depression and psychological distress.6

Inflammation is associated with lots of chronic disease such as malignancy, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, connective tissue disease, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular (CV) disease and psychiatric disorders.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 White blood cell count and its subtypes are some of the predictors of chronic inflammation. Neutrophils and leukocytes play an important role in inflammatory processes. The neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), which can be derived from the white blood cell count is an inexpensive, reproducible test and has been investigated as a new biomarker for systemic inflammatory response.15,16 NLR has emerged as an important inflammatory marker, and high NLR levels are associated with increased mortality in some malignancies.17,18 The aim of the study is to investigate the relation of NLR with severity of depression and CV risk factors.

METHODS

Study population

Patients were selected among cases referred to psychiatry outpatient clinics for evaluation of depressive disorders from January 2013 to October 2013. The study included 256 consecutive patients with diagnosed depression according to the criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Text (DSM IV-TR). All patients were evaluated about previous medical history. Patients with systemic disease and using of medical treatment to affect the white blood cell counts, such as hematopoietic system disorders, history of malignancies and/or treatment with chemotherapy, evidence of any concomitant inflammatory disease, acute infection, and chronic inflammatory status, acute coronary syndrome and percutaneous coronary intervention within the past 6 months, history of using the glucocorticoid therapy within the past 3 months, secondary hypertension, heart failure, history of chronic renal or hepatic disease and cerebrovascular disease were excluded from the study. The investigation complies with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and all participants gave written informed consent before participating.

Measurement of severity of depression

Patients were evaluated for severity of depressive symptoms by using Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D). HAM-D has proven useful for many years as a method of determining a patient's level of depression.19 The reliability and validity of the Turkish version of HAM-D has been established in Turkish patients, which have been widely used in clinical practice.20 HAM-D consists of 21 items, but the scoring is based on the first 17 items. Eight items are scored on a 5-point scale, ranging from zero point (not present) to four points (severe). Nine items are scored from 0 to 2. Total score is evaluated as follows; 0-7=Normal, 8-13=Mild Depression, 14-18=Moderate Depression, 19-22=Severe Depression, ≥23=Very Severe Depression (http://www.assessmentpsychology.com/HAM-D-scoring.pdf).

Laboratory findings and evaluation of cardiovascular risk factors

Complete blood counts which included total white blood cells, neutrophils, and lymphocytes were obtained at the time of admission. NLR was calculated as the ratio of neutrophil count to lymphocyte count. All patients were evaluated for presence of cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and smoking. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg, previously diagnosed hypertension, or use of any antihypertensive medications. Hyperlipidemia was defined as serum total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL, serum triglyceride ≥200 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥130 mg/dL, previously diagnosed hyperlipidemia, or use of lipid-lowering medication. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting plasma glucose levels more than 126 mg/dL in multiple measurements, previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus or use of antidiabetic medications such as oral anti-diabetic agents or insulin. Smoking status was defined as the history of tobacco use at admission or in the 6 months prior to visit.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 statistical package for Windows. Continuous data were expressed as mean±standard deviation while categorical data were presented as percentages. Chi-square test was used for comparison of categorical variables while Student t-test or Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare parametric and nonparametric continuous variables, respectively. Normal distribution is assessed by the Kolmogorov Smirnov test. Correlation analysis was performed by Pearson or Spearman's correlation test. Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the independent predictors of mild and moderate versus severe and very severe depression. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to determine the cut-off level of NLR to predict the mild and moderate versus severe and very severe depression. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

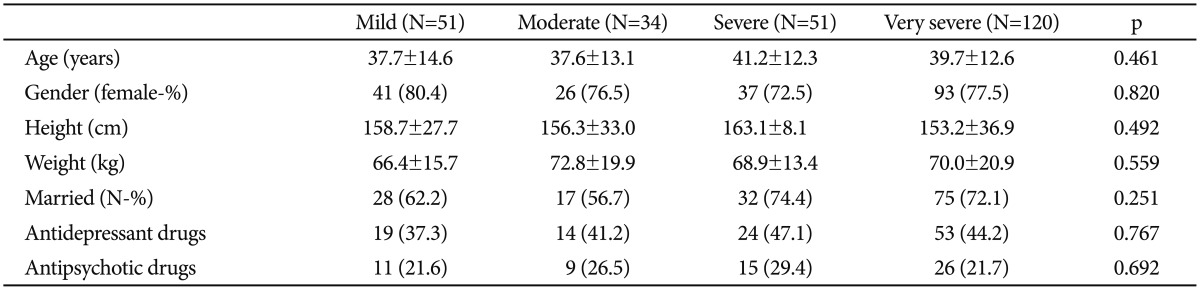

The study population was consisted of 256 consecutive patients who were diagnosed with depression. All patients were divided into four groups according to scores of HAM-D such as mild, moderate, severe, and very severe depression (HAM-D scores 8-13, 14-18, 19-22, and ≥23, respectively). Baseline characteristics and clinical data of study population are shown in Table 1. Patient characteristics, usage of antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs are similar between groups.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and clinical data of the study population.

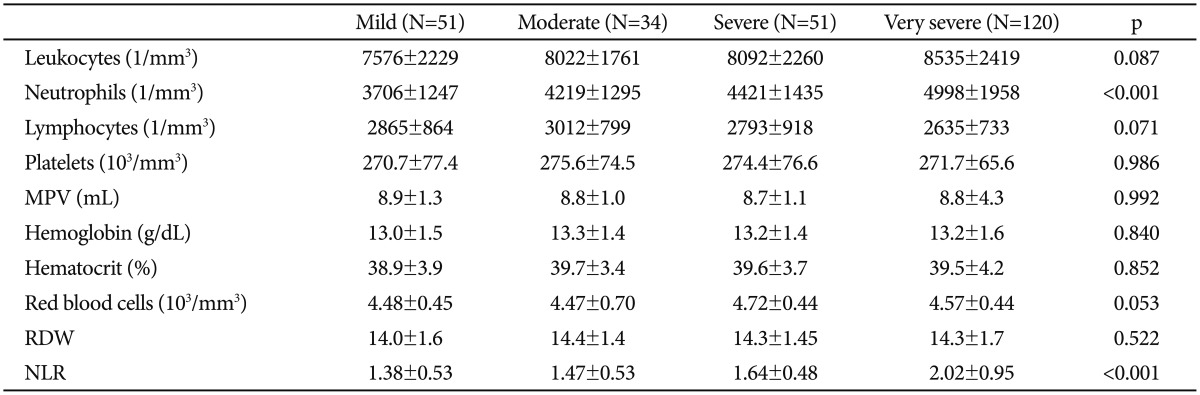

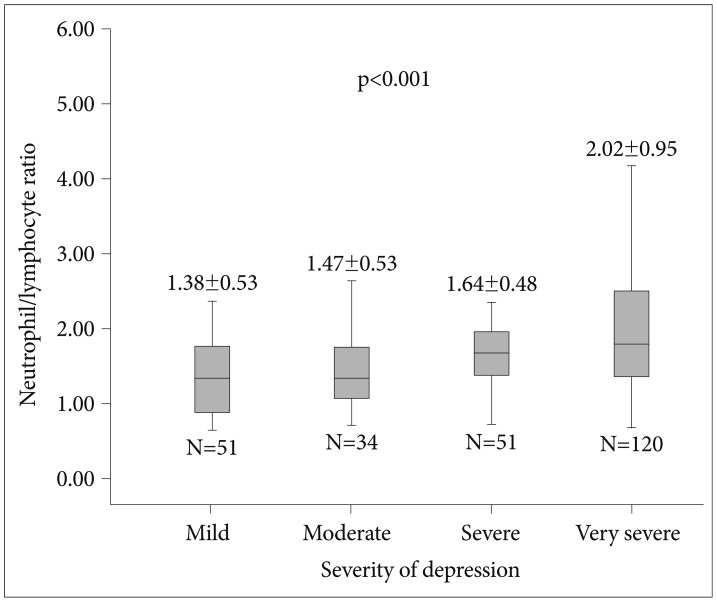

Measurements of complete blood count of study population are expressed in Table 2. We compared severity of depression and NLR between groups. Patients with higher HAM-D scores had significantly higher NLR levels compared to patients with lower HAM-D scores (Figure 1). Correlation analysis revealed that severity of depression is associated with NLR (r=0.333, p<0.001) in patients with depressive disorders. Patients were also divided into two groups according to usage of psychotropic drugs. Patients under treatment with antidepressant (110 patients) and/or antipsychotic (61 patients) drugs have higher NLR values compared to patients free of psychotropic drugs without reaching statistical significance (1.76±0.78 vs. 1.74±0.81, p=0.853).

Table 2. Comparison of the complete blood count parameters of the study population.

NLR: neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, RDW: red cell distribution width, MPV: mean platelet volume

Figure 1. Comparison of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio between patients with depression according to severity of disease.

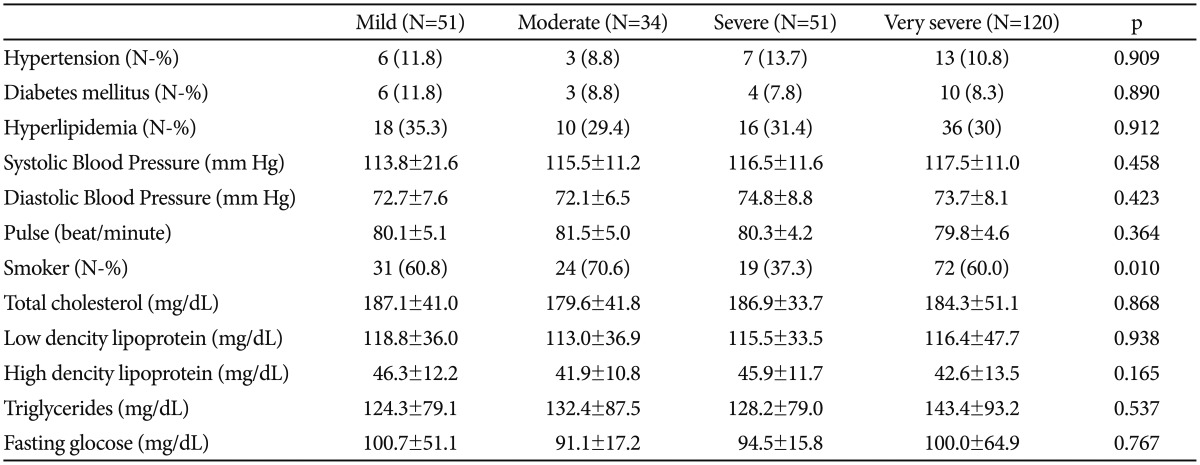

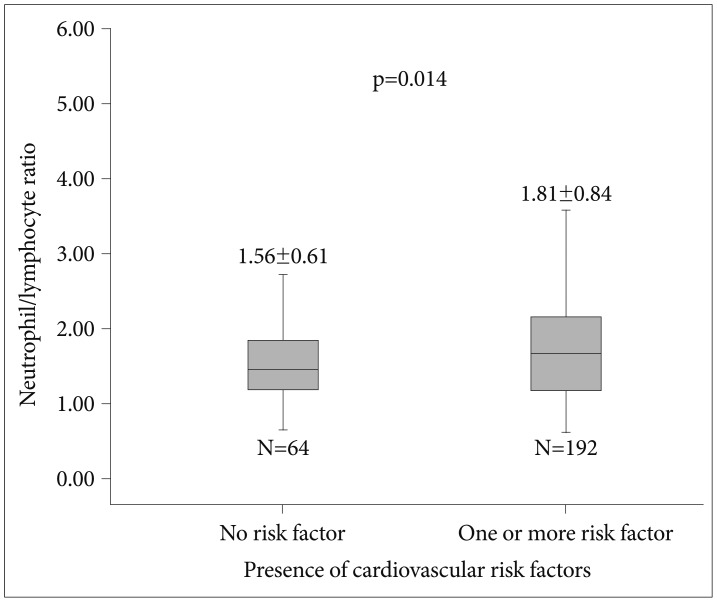

All study population were evaluated for presence of cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and smoking. Cardiovascular risk factors and laboratory findings are shown in Table 3. Patients with one or more cardiovascular risk factors had significantly higher NLR levels compared to patients that have no cardiovascular risk factors (Figure 2). Patients with smoking have higher NLR values compared to patients without smoking without reaching statistical significance (1.81±0.87 vs. 1.67±0.67, p=0.142). Correlation analysis revealed that presence of cardiovascular risk factors is associated with NLR (r=0.132, p=0.034) in patients with depressive disorders.

Table 3. Comparison of the cardiovascular risk factors and laboratory findings.

Figure 2. Comparison of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio between patients with depression according to presence of cardiovascular risk factors.

All patients were divided into two groups according to scores of HAM-D such as mild and moderate or severe and very severe depression (HAM-D scores 8-18 or ≥19). Severe and very severe depression had significantly higher NLR levels compared to patients with mild and moderate depression (1.91±0.85 vs. 1.42±0.53, p<0.001). In univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses, NLR was an independent predictor of severe or very severe depression (odds ratio: 3.02, 95% confidence interval: 1.867-4.884, p<0.001). ROC analysis was performed to determine the cut-off value of NLR to predict the severe or very severe depression. A NLR of 1.57 or higher predicted severe or very severe depression with a sensitivity of 61.4% and specificity of 61.2%.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we explored that higher HAM-D scores were associated with higher NLR values in patients with depressive disorders. Severity of depression was also correlated with NLR in these patients. Moreover NLR more than 1.57 was an independent predictor of severe or very severe depression. CV risk factors may also be attributed to the course of disease in these patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in literature to evaluate the association between NLR and severity of depression and its relation with CV risk factors.

Depression is a common, complex disease and it is associated with prominent disability, social burden and reduced quality of life.21 Depression is associated with increased morbidity21 and it is also common in patients with CV disease.22 Previous studies have shown that depression is associated with interaction in the central nervous system, immune response, and vascular reactivity.23 Immune system is altered during the process of clinical depression. Although acute stress stimulates immune functions, chronic stress represses immune system.23 Alterations in the levels of inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukins (IL-1, IL-6) are central to the pathophysiology of depression.24 Inflammatory cytokines are important biomarkers in the course of disease including diagnosis, treatment selection and long-term follow-up.23,24 Although inflammatory cytokines are useful biomarkers, increased cost and limited attainability are some of the handicaps.

White blood cell count is a cheap and commonly used inflammatory marker. Neutrophils are the most abundant type of the white blood cells. Neutrophils and leukocytes play an important role in the course of inflammatory diseases. They take important roles in the inflammatory response. Neutrophils are the first cells responding to inflammation especially caused by bacterial infection, cancer and environmental exposure. NLR which can be derived from the white blood cell count is an inexpensive, routinely used, reproducible test and has shown up as a marker of systemic inflammatory response. Neutrophils lead to secretion of several inflammatory cytokines. Inflammation triggered by these molecules can both induce an oxidative stress and further inflammation due to cell dysfunction in various organs. Increased NLR is also interconnected with oxidative stress and increased cytokine productions, and those findings were found in depressive disorders.25 In a previous study, Kim et al.12 reported that activation of monocytic proinflammatory cytokines, and inhibition of interferon gamma, interleukin-2, and interleukin-4 may be associated with immunological dysregulation in patients with major depressive disorder. Transforming growth factor-beta1 may be associated with the regulation of monocytic cytokines in those patients. Previous studies showed that NLR is associated with poor clinical outcomes in cardiac diseases, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and several malignancies.17,18,26 NLR is a new parameter that gives us information not only about the systemic inflammation but also the stress response of the patient. While mainly high neutrophil counts reflect to inflammation, low lymphocyte counts reflect poor general health and physiologic stress.15 Our findings demonstrated that NLR is associated with severity of depression. Presence of CV risk factors is also associated with higher NLR values in patients with depressive disorder. According to our study results, NLR may be a state marker of presence and severity of depression.

There is a close relationship between inflammation and smoking.27 Previous studies have demonstrated that chronic inflammation and immune response play an important role in the development of smoking related disorders.28 Smoking may increase the atherosclerosis through triggering the inflammation.29 It is not surprising that smoking is also associated with NLR values. In our study, patients with smoking had higher NLR values without reaching statistical significance.

Our study has important clinical implications. We have shown for the first time the association between NLR and severity of depression. We demonstrated that NLR levels might be related with the severity of depression in patients that definitely have no other conditions that may activate inflammatory response. NLR seems to be a simple, cost effective method for evaluation of the severity of depression in depressive disorder and it may be used in outpatient clinic setting. Closer follow up can be performed for these patients who have higher NLR levels.

Our study has several limitations. This study was designed as a cross-sectional study. It would be better if we had followed the patients and explored the relation between course of depression and NLR levels. We did not evaluate the prognostic value of the NLR and its relation with CV risk factors in these patients. Since we could not determine the subtype of depression, we could not assess the varieties related to this issue and further studies may determine the associations between NLR and subtype of depression. Lack of a healthy control group and/or a group with other psychiatric disorder as comparators is an important limitation of our study. It would be better if we displayed the effect of psychological stress on NLR levels. Therefore, further large scale, prospective studies are needed to explore extensive information about the impact of NLR on severity of depression.

In conclusion, higher HAM-D scores were associated with higher NLR levels in patients with depressive disorder and severity of depression was also correlated with NLR in these patients. Moreover NLR more than 1.57 was an independent predictor of severe or very severe depression. CV risk factors may also contribute to the course of disease in these patients. A simple cheap white blood cell count may also give an idea about the severity of depression and should be included in psychiatric evaluation of these patients.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebmeier KP, Donaghey C, Steele JD. Recent developments and current controversies in depression. Lancet. 2006;367:153–167. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67964-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thornton LM, Andersen BL, Schuler TA, Carson WE., 3rd A psychological intervention reduces inflammatory markers by alleviating depressive symptoms: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:715–724. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b0545c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dekker RL, Moser DK, Tovar EG, Chung ML, Heo S, Wu JR, et al. Depressive symptoms and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;13:444–450. doi: 10.1177/1474515113507508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elovainio M, Aalto AM, Kivimäki M, Pirkola S, Sundvall J, Lönnqvist J, et al. Depression and C-reactive protein: population-based Health 2000 study. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:423–430. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31819e333a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wium-Andersen MK, Orsted DD, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated C-reactive protein, depression, somatic diseases, and all-cause mortality: a mendelian randomization study. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S, Choe JW, Kim HK, Sung J. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and cancer. J Epidemiol. 2011;21:161–168. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20100128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitsavos C, Tampourlou M, Panagiotakos DB, Skoumas Y, Chrysohoou C, Nomikos T, et al. Association between low-grade systemic inflammation and type 2 diabetes mellitus among men and women from the ATTICA study. Rev Diabet Stud. 2007;4:98–104. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2007.4.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libby P. What have we learned about the biology of atherosclerosis? The role of inflammation. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:3J–6J. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01879-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okyay GU, Inal S, Oneç K, Er RE, Paşaoğlu O, Paaolu H, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in evaluation of inflammation in patients with chronic kidney disease. Ren Fail. 2013;35:29–36. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2012.734429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torun D, Ozelsancak R, Yiğit F, Micozkadıoğlu H. Increased inflammatory markers are associated with obesity and not with target organ damage in newly diagnosed untreated essential hypertensive patients. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2012;34:171–175. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2011.577489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim YK, Na KS, Shin KH, Jung HY, Choi SH, Kim JB. Cytokine imbalance in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:1044–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myint AM, Leonard BE, Steinbusch HW, Kim YK. Th1, Th2, and Th3 cytokine alterations in major depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;88:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myint AM, Kim YK. Network beyond IDO in psychiatric disorders: revisiting neurodegeneration hypothesis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;48:304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibson PH, Cuthbertson BH, Croal BL, Rae D, El-Shafei H, Gibson G, et al. Usefulness of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio as predictor of new-onset atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sunbul M, Gerin F, Durmus E, Kivrak T, Sari I, Tigen K, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte and platelet to lymphocyte ratio in patients with dipper versus non-dipper hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2014;36:217–221. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2013.804547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamhane UU, Aneja S, Montgomery D, Rogers EK, Eagle KA, Gurm HS. Association between admission neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:653–657. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halazun KJ, Aldoori A, Malik HZ, Al-Mukhtar A, Prasad KR, Toogood GJ, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts survival following hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akdemir A, Türkçapar MH, Orsel SD, Demirergi N, Dag I, Ozbay MH. Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:161–165. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.19756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sunbul M, Zincir SB, Durmus E, Sunbul EA, Cengiz FF, Kivrak T, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with coronary artery disease. Bull Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;23:345–352. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dinan TG. Inflammatory markers in depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:32–36. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328315a561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashmi AM, Butt Z, Umair M. Is depression an inflammatory condition? A review of available evidence. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63:899–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasama T, Miwa Y, Isozaki T, Odai T, Adachi M, Kunkel SL. Neutrophil-derived cytokines: potential therapeutic targets in inflammation. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2005;4:273–279. doi: 10.2174/1568010054022114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruk M, Przyłuski J, Kalińczuk Ł, Pregowski J, Deptuch T, Kadziela J, et al. Association of non-specific inflammatory activation with early mortality in patients with ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome treated with primary angioplasty. Circ J. 2008;72:205–211. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andreoli C, Bassi A, Gregg EO, Nunziata A, Puntoni R, Corsini E. Effects of cigarette smoking on circulating leukocytes and plasma cytokines in monozygotic twins. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015;53:57–64. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2013-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith CJ, Perfetti TA, King JA. Perspectives on pulmonary inflammation and lung cancer risk in cigarette smokers. Inhal Toxicol. 2006;18:667–677. doi: 10.1080/08958370600742821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]