Abstract

Few studies have assessed the neural mechanisms of the effects of emotion on cognition in generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) patients. In this functional MRI (fMRI), we investigated the effects of emotional interference on working memory (WM) maintenance in GAD patients. Fifteen patients with GAD participated in this study. Event-related fMRI data were obtained while the participants performed a WM task (face recognition) with neutral and anxiety-provoking distracters. The GAD patients showed impaired performance in WM task during emotional distracters and showed greater activation on brain regions such as DLPFC, VLPFC, amygdala, hippocampus which are responsible for the active maintenance of goal relevant information in WM and emotional processing. Although our results are not conclusive, our finding cautiously suggests the cognitive-affective interaction in GAD patients which shown interfering effect of emotional distracters on WM maintenance.

Keywords: Generalized anxiety disorder, Working memory, Emotional distractor, Functional magnetic resonance imaging

INTRODUCTION

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) affects an average of 5% of people over the course of their lives and up to 25% of patients who visited anxiety disorder clinics have GAD.1 GAD is characterized by chronic, excessive and difficult to control anxiety and worry that is associated with somatic symptoms,1 which might be due to abnormalities of the functions that regulate emotional processes.2 Normally, people tend to use worry as a strategy for managing emotional self-control. However, excessive worry is a fallacious strategy to solve objective and subjective difficulties, which cause uncontrollable anxiety, and vice versa. Cognitive models suggest that worry reflects an overlearned compensatory strategy for dulling emotional experience.3

Despite a growing recognition of the importance of emotion regulation deficits in GAD, few studies have assessed neural mechanisms of the effects of emotion on cognition. To our best knowledge, this study is the first fMRI study examining the regional brain differences from the direct effects of emotional distraction during delayed working memory (WM) task among GAD patients. We evaluated the effects of emotional distractors on WM maintenance in GAD patients using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) with a face recognition task.

METHODS

Subjects

Fifteen GAD patients (mean age=36.4±11.2 years) participated. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation. All of the GAD patients were diagnosed on the basis of DSM-IV-TR by using Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders (SCID-I)4 and had no other psychiatric disorders. The mean year of education was 13.7±2.6 years. Except for one patient, psychotropic medications were prescribed for fourteen patients; escitalopram (n=8), paroxetine (n=2), bupropion (n=1), fluvoxamine (n=1), duloxetine (n=1), mirtazapine (n=1), buspirone (n=6), alprazolam (n=5), zolpidem (n=1). Among them, nine patients prescribed multiple psychotropic medication and five patients prescribed single psychotropic medication. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the Ethics Committee of Chonbuk National University Hospital.

Task paradigms

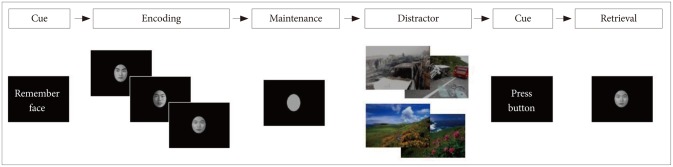

Subjects underwent fMRI scanning during a face recognition task with emotional distractors (neutral and anxiety-provoking pictures). The activation paradigm consisted of a trial with the sequence "encoding (6 seconds); WM maintenance (4 seconds); distracter (6 seconds); button preparation (2 seconds); retrieval (2 seconds); and intertrial interval (ITI) (12 seconds)" (Figure 1). The human faces (half male, half female) were selected from a high school yearbook, converted to black-and-white and cropped into an oval shape showing only the eyes, nose, mouth, and eyebrows. To induce emotional responses of participants, neutral and anxiety-inducing images were viewed. The retrieval task consisted of 10 trials with anxiety-provoking distracters and 10 trials with neutral distracters, yielding a total trial time of 640 s. Each distracter (anxiety-provoking or neutral) trial included two distracter pictures. Of the total 20 trials, the order of the two types of the distracters was randomly arranged. Prior to the fMRI experiment, 50 images of each type were collected from the International affective picture system (IAPS)5 and a variety of Web sites. The neutral images designed to induce a comfortable feeling including scenic pictures and the anxiety-provoking images included photographs of life-threatening behaviors. Ten college students each nominated 30 neutral and anxiety-inducing images from a pool of 100 images as appropriate experimental stimulators. Among them, psychiatrist selected 20 neutral and 20 anxiety-provoking images. All task paradigms for this fMRI study were presented to the subjects using the SuperLab software (Cedrus Corporation, San Pedro, CA, USA).

Figure 1. Diagrams for the Delayed-Response Working Memory (WM) Tasks With Anxiety-provoking and Neutral Distracters*. *In the encoding task, three different human faces appear once; the subjects were instructed to encode and maintain the WM for the presented human faces, followed by looking at the distracters with neutral pictures (or anxiety-provoking pictures) while maintaining the WM. In the retrieval period, either of the face presented in the encoding task or a new face was presented for (50% were presented with an encoding face, and 50% were presented with a new face), and then response to the probe for the previously presented human face or a new one.

fMRI data acquisition

An fMRI data acquisition was performed on a 3.0 Tesla Magnetom Verio MR Scanner (Siemens Medial Solutions, Malvern, PA, USA) with a 12-channel bird-cage head coil. A total of 25 axial slices parallel to the anterior commissure to posterior commissure (AC-PC) line were acquired using a gradient-echo echo planar pulse sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE)=2000 ms/30 ms, flip angle=90°, field of view (FOV)=22×22 cm, matrix size=64×64, and slice thickness=5 mm. In addition, two phases of dummy scans were supplemented to circumvent unstable fMRI signals. The high resolution T1-weighted images (TR/TE=1900 ms/2.35 ms) were comprised with FOV=22×22 cm, matrix size=256×256, slice thickness=5 mm.

Data preprocessing and analysis

The fMRI data were analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM8, Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, University College London, London, UK). Prior to the statistical analysis, a slice-timing was performed to correct for differences of the slice-acquisition time. The images were realigned utilizing to the reference volume and were spatially normalized to the standard EPI template in MNI space and resampled to 2×2×2 mm resolution. Finally, the images were smoothed with an 8 mm full-width-half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian filter. The preprocessed data were analyzed using the standard general linear model (GLM) approach within the SPM8. For the imaging analysis in this study, we used the data of the distracter phase from among the task paradigms. To analyze the individual blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal, an independent t-test was performed in the rest and activation conditions (neutral pictures and anxiety-provoking pictures). For the within group comparison of the GAD patients, the differential brain activation maps, which are correspondent to the contrast of neutral pictures vs. anxiety-provoking pictures, were obtained from the paired t-test (p<0.001) with a spatial extent of at least 10 adjacent voxels.

RESULTS

The demographic characteristics were as follows; age (36.4±11.2), gender (8 male, 7 female), years of education (13.7±2.6). The clinical characteristics were as follows; duration of illness (4.7±7.6), HAM-A (18.5±4.7), STAI-S (53.9±10.5), and ASI-R (62.3±27.1). The feeling of discomfort, which rated after the fMRI experiment, for anxiety-provoking pictures measured on an 11 point visual analogue scale and was significantly higher than that regarding the neutral pictures (7.4±1.5 vs. 0.1±0.4, respectively). In terms of behavioral performance, the scores for the face recognition task with the neutral scene were significantly higher than those for the anxiety-provoking pictures (10 trials each, 72.0±13.2% vs. 60.7±14.9%, p<0.05). There was no missing response in behavioral performance.

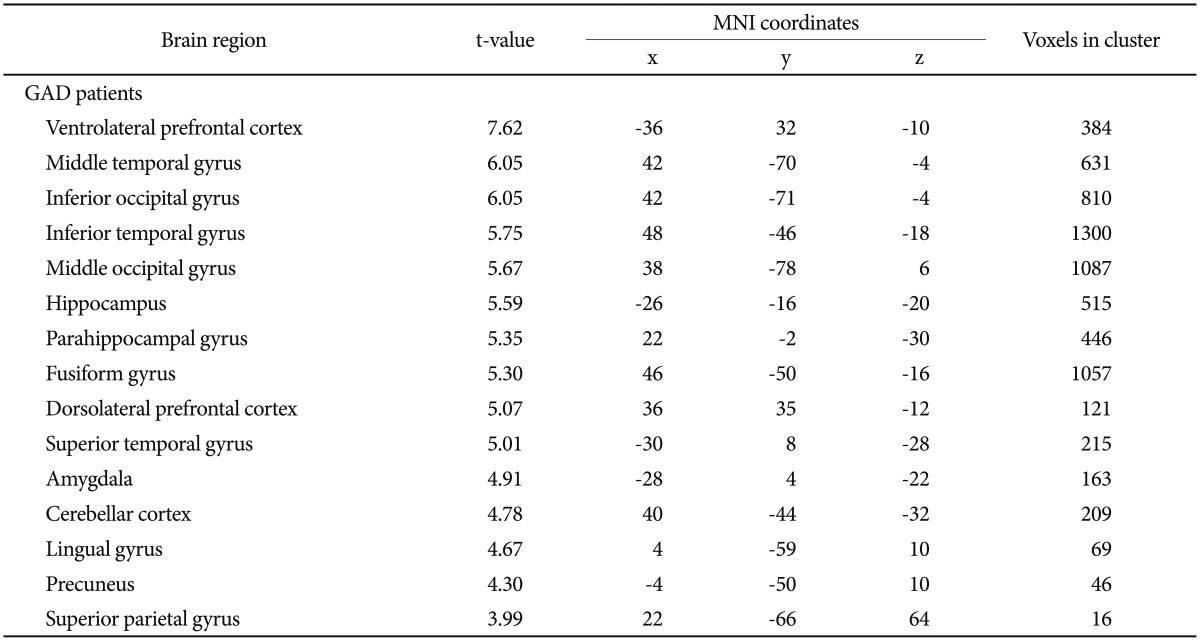

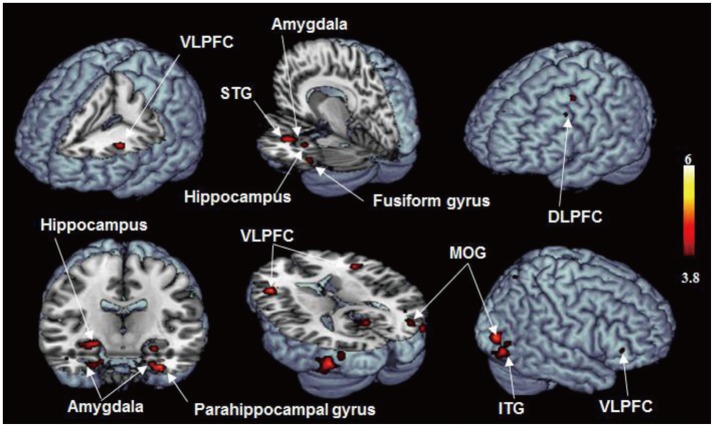

The brain activation area which shown significantly increased activation regarding the anxiety-provoking pictures compared with the neutral pictures were as below (all brain regions p<0.001) (Table 1, Figure 2); VLPFC, Middle temporal gyrus, Inferior occipital gyrus, Inferior temporal gyrus, Middle occipital gyrus, Hippocampus, Parahippocampal gyrus, Fusiform gyrus, DLPFC, Superior temporal gyrus, Amygdala, Cerebellar cortex, Lingual gyrus, Precuneus, Superior parietal gyrus. The brain areas with predominant activities in patients with GAD were not observed when viewing neutral distracter compared with anxiety-provoking distracter (p<0.001).

Table 1. Brain regions showed increased activation (anxiety-provoking picture>neutral scene, p<0.001).

GAD: generalized anxiety disorder, MNI: Motreal Neurological Institute

Figure 2. Brain regions showed increased activation (anxiety-provoking picture> neutral scene, p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we investigated brain activation patterns associated with the effects of emotional distractors during WM maintenance in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. At a facial recognition task level, we found that WM maintenance in the GAD patients was significantly impaired by the emotional distractors, as evidenced by the significantly lower task accuracies with the emotional distracters compared to those with neutral pictures. It seemed that GAD patients tried to maintain goal-relevant in formation in mind and keeping goal-irrelevant information out of mind while interfered by anxiety-provoking situation. Accordingly, in our result, brain regions relevant to anxiety, WM maintenance, and cognitive inhibition showed increased activation. As compared to the face recognition task with neutral pictures, brain regions including the DLPFC, VLPFC, amygdala, and hippocampus revealed increased activation during the task with anxiety-provoking pictures.

Our results are in consistent with previous studies. The role of the amygdala in emotional processing is relatively well established in healthy control6,7 and in patients with anxiety disorder.8 Amygdala showed greater activity in amygdala in response to fearful faces in GAD patients.9,10 The hippocampus adjacent to the amygdala also plays a crucial role in anxiety.11 In addition, hippocampal hyperactivity is also associated cognitive dysfunction.12 The prefrontal cortex is highly interacts with various brain structures, including other cortical, subcortical and brain stem sites.13 In healthy controls, the DLPFC involved in the active maintenance of goal-relevant information in WM,14,15 whereas the VLPFC was involved in emotional processing.16,17 In previous study with GAD patients, Monk et al.18 demonstrated results which shown greater activation in the VLPFC in the attentional bias away from angry face than healthy controls.

Interestingly, it has been suggested that an affective-cognitive interaction mainly constituted by two control system, which are dorsal executive and ventral emotional control system. The dorsal executive control system (such as DLPFC and lateral parietal cortex) involved in the active maintenance of gold-relevant information processing in working memory.14,19,20 The ventral emotional system (VLPFC and medial PFC, and amygdala) involved in emotional processing.20,21,22 Although our results are not conclusive, one possible explanation of increased activation in the DLPFC, VLPFC, and amygdala might be the result of an affective-cognitive interaction during WM maintenance with emotional distracters in GAD patients.

In our result, increased brain activations were found in the fusiform gyrus and superior parietal gyrus. These areas are known to be involved in facial recognition, which also shown increased activation using facial recognition task in previous studies.23,24,25 The inferior and middle temporal gyrus also works together with the fusiform gyrus in recognition of the information.27 The superior temporal gyrus has been involved in the perception of emotions in facial stimuli.28

There are some limitations in our study. First, the number of trials in the WM task used in our study was limited since the head-movement could not be sustained with increasing experimental time during the fMRI. Second, the possibility of medication effects on brain activation patterns could not be excluded.

In summary, the present study provides the first functional neuroimaging evidence in GAD patients that impaired performance in the presence of emotional distracters are associated with brain regions responsible for the active maintenance of goal relevant information in the WM (DLPFC) and emotional processing including the VLPFC, amygdala, and hippocampus. Although our results are not conclusive, our finding cautiously suggests the cognitive-affective interaction in GAD patients which shown interfering effect of emotional distracters on WM maintenance. Further research on the effects of emotion on cognition, such as a comparison with healthy control, may help to further clarify the neural mechanisms of GAD and other anxiety disorders.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by research funds of Chonbuk National University in 2011.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: :American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mennin DS, Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Fresco DM. Preliminary evidence for an emotion dysregulation model of generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1281–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mennin DS, Holaway RM, Fresco DM, Moore MT, Heimberg RG. Delineating components of emotion and its dysregulation in anxiety and mood psychopathology. Behav Ther. 2007;38:284–302. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders Research Version, Patient Edition, (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective Ratings of Pictures and Instruction Manual. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costafreda SG, Brammer MJ, David AS, Fu CH. Predictors of amygdala activation during the processing of emotional stimuli: a meta-analysis of 385 PET and fMRI studies. Brain Res Rev. 2008;58:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sergerie K, Chochol C, Armony JL. The role of the amygdala in emotional processing: a quantitative meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:811–830. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kent JM, Rauch SL. Neuroimaging Studies of Anxiety Disorders. In: Charney DS, Nestler EJ, editors. Neurobiology of Mental Illnesses. 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 639–660. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blair K, Shaywitz J, Smith BW, Rhodes R, Geraci M, Jones M, et al. Response to emotional expressions in generalized social phobia and generalized anxiety disorder: evidence for separate disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1193–1202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07071060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whalen PJ, Johnstone T, Somerville LH, Nitschke JB, Polis S, Alexander AL, et al. A functional magnetic resonance imaging predictor of treatment response to venlafaxine in generalized anxiety disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:858–863. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engin E, Treit D. The role of hippocampus in anxiety: intracerebral infusion studies. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18:365–374. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282de7929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNaughton N. Cognitive dysfunction resulting from hippocampal hyperactivity-a possible cause of anxiety disorder? Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;56:603–611. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00419-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvarez JA, Emory E. Executive function and the frontal lobes: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2006;16:17–42. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Courtney SM, Ungerleider LG, Keil K, Haxby JV. Transient and sustained activity in a distributed neural system for human working memory. Nature. 1997;386:608–611. doi: 10.1038/386608a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith EE, Jonides J. Storage and executive processes in the frontal lobes. Science. 1999;283:1657–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aron AR, Robbins TW, Poldrack RA. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jha AP, Fabian SA, Aguirre GK. The role of prefrontal cortex in resolving distractor interference. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2004;4:517–527. doi: 10.3758/cabn.4.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monk CS, Nelson EE, McClure EB, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Leibenluft E, et al. Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation and attentional bias in response to angry faces in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1091–1097. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chafee MV, Goldman-Rakic PS. Inactivation of parietal and prefrontal cortex reveals interdependence of neural activity during memory guided saccades. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1550–1566. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolcos F, McCarthy G. Brain systems mediating cognitive interference by emotional distraction. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2072–2079. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5042-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson RJ, Irwin W. The functional neuroanatomy of emotion and affective style. Trends Cogn Sci. 2000;3:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phan KL, Wager T, Taylor SF, Liberzon I. Functional neuroanatomy of emotion: a meta-analysis of emotion activation studies in PET and fMRI. NeuroImage. 2002;16:331–348. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acheson DJ, Hagoort P. Stimulating the brain's language network: syntactic ambiguity resolution after TMS to the inferior frontal gyrus and middle temporal gyrus. J Cogn Neurosci. 2013;25:1664–1677. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dolcos F, Miller B, Kragel P, Jha A, McCarthy G. Regional brain differences in the effect of distraction during the delay interval of a working memory task. Brain Res. 2007;1152:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM. The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4302–4311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04302.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ojeda N, Ortuno F, Arbizu J, Lopez P, Marti-Climent JM, Penuelas I, et al. Functional neuroanatomy of sustained attention in schizophrenia: contribution of parietal cortices. Hum Brain Mapp. 2002;17:116–130. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spiridon M, Fischl B, Kanwisher N. Location and spatial profile of category-specific regions in human extrastriate cortex. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006;27:77–89. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bigler ED, Mortensen S, Neeley ES, Ozonoff S, Krasny L, Johnson M, et al. Superior temporal gyrus, language function, and autism. Dev Neuropsychol. 2007;31:2217–2238. doi: 10.1080/87565640701190841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]