Highlights

-

•

Myotonic dystropy patients have after major surgery increased risk for pulmonary complications because of weakness of respiratory muscles.

-

•

Such a patient tolerated a minimally invasive esophagectomy for cancer.

-

•

Minimally invasive instead of open surgery was probably the only feasible treatment due to less strain on respiratory function.

-

•

A life-threatening complication of gastrobronchial fistula healed by stenting of the gastric conduit and ventilation with low airway pressures.

-

•

Indications for stenting of gastrobronchial fistula are discussed.

Abbreviations: MIE, minimally invasive esophagectomy; MD, myotonic dystrophy

Keywords: Myotonic dystrophy, Cancer, Esophagectomy, Fistula

Abstract

Introduction

Myotonic dystrophies are inherited multisystemic diseases characterized by musculopathy, cardiac arrythmias and cognitive disorders. These patients are at increased risk for fatal post-surgical complications from pulmonary hypoventilation. We present a case with myotonic dystrophy and esophageal cancer who had a minimally invasive esophagectomy complicated with gastrobronchial fistulisation.

Presentation of case

A 44-year-old male with myotonic dystrophy type 1 and esophageal cancer had a minimally invasive esophagectomy performed instead of open surgery in order to reduce the risk for pulmonary complications. At day 15 respiratory failure occurred from a gastrobronchial fistula between the right intermediary bronchus (defect 7–8 mm) and the esophagogastric anastomosis (defect 10 mm). In order to minimize large leakage of air into the gastric conduit the anastomosis was stented and ventilation maintained at low airway pressures. His general condition improved and allowed extubation at day 29 and stent removal at day 35. Bronchoscopy confirmed that the fistula was healed. The patient was discharged from hospital at day 37 without further complications.

Discussion

The fistula was probably caused by bronchial necrosis from thermal injury during close dissection using the Ligasure instrument. Fistula treatment by non-surgical intervention was considered safer than surgery which could be followed by potentially life-threatening respiratory complications. Indications for stenting of gastrobronchial fistulas will be discussed.

Conclusions

Minimally invasive esophagectomy was performed instead of open surgery in a myotonic dystrophy patient as these patients are particularly vulnerable to respiratory complications. Gastrobronchial fistula, a major complication, was safely treated by stenting and low airway pressure ventilation.

1. Introduction

Myotonic dystrophies (MD) are autosomal dominant inherited multisystemic diseases characterized by symptoms including varying degrees of musculopathy, cognitive disorders and cardiac arrythmias [1]. It exists in two forms of which MD type 1 is the classic variant known as Steinert́s disease with more severe symptoms than MD type 2, also known as proximal myotonic myopathy. The gene defect of DM type 1 was discovered in 1992 and found to be a mutation of the myotonic dystrophy protein kinase gene located on chromosome 19q13.3.3 which codes for a myosin kinase expressed in skeletal muscle. In patients with a clinical picture of MD 2 the mutation is on chromosome 3. The estimated prevalence of MD 1 and MD 2 are about 1/8000 each, respectively.

The most crucial element afflicting surgery in MD patients is the effect on respiration postoperatively because of myopathy of respiratory muscles that increase the risk for pneumonia, atelectasis and ventilatory failure [2], [3].

MD is associated with increased risk of cancer. A Swedish and Danish study [4], including 1658 patients, generally disclosed a two-fold incidence ratio for cancer compared with the general population, and most pronounced (5–7-fold) for malignancy of the endometrium, ovary, colon and brain [4]. There are no studies reporting cancer of the esophagus.

We report for the first time a MD type 1 patient who was operated for esophageal cancer. The method used was a minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) in order to reduce the risk for respiratory failure. Gastrobronchial fistula (GBF) occurred as a major complication and was successfully treated with esophagogastric stenting and low pressure mechanical ventilation. Experience and requirements for stenting of gastrobronchial fistulas involving the esophagogastric anastomosis will be discussed.

2. Case presentation

A 44-year-old male of Norwegian ethnicity with a maternally inherited MD type 1, had a moderate functional disability in daily life, partially dependent on a wheel chair, but was able to walk about 500 m.

He presented with dysphagia and weight loss. Endoscopy revealed Barrett́s esophagus at 35–40 cm from the incisors, including a malignant stricture at 35 cm. Biopsies showed adenocarcinoma. There was no evidence of metastasis based on computed tomography (CT). Echocardiography (ECG) showed atrioventricular block type I and left posterior fascicular block. Spirometry demonstrated a moderate restriction (FVC 325l, 75% of predicted, FEV1 74% of predicted). Alveolar gas diffusion capacity and peripheral venous oxygen saturation were normal. The patient was considered unsuitable for conventional open surgery owing to the risk of myopathic postoperative respiratory failure.

He was operated in April 2012 with MIE in the left lateral position [5]; Laparscopic gastric resection converting the gastric remnant into a 4–5 cm wide tube. Thoraco-scopic esophageal resection and construction of a mediastinal stapled functional end-to-end esophagogastrostomy was done. Dissection using bipolar Ligasure with blunt tip posterior to esophagus and close to the right main bronchus was part of the procedure. The esophagus was transected with endo GIA (violet magazine) 10 mm caudal to the azygos vein. Macroscopically there were 2 cm free resection margin proximal to the tumor. Histology revealed a low differentiated adenocarcinoma staged T3N2Mx with tumor infiltration in the circumferential resection margin.

The patient was extubated without complications the first day postoperatively but reintubated the second day because of pneumonia and respiratory failure. A chest X-ray revealed atelectasis of the right lower lobe and bronchoscopic clearance of excess mucus in the bronchial tree was necessary. He was extubated on the third day and the patient had intermittent nocturnal non-invasive ventilation because of hypoventilation episodes and sleep apnea. At day seven the esophagogastric anastomosis was intact as judged by oral contrast X-ray enema (Fig. 1). Spirometry on day 11 showed significant reductions of FVC and FEV1 in the supine position and a restrictive spirometry indicating poor diaphragmatic function.

Fig. 1.

At day seven the esophagogastric anastomsis (arrow) was found intact as judged by oral contrast enema.

Unexpectedly, on day 15 postoperatively respiratory failure developed with oxygen desaturation, hypotension, tachypnea and signs of septicemia. ECG was normal. Bronchoscopy demonstrated a fistula with diameter 7–8 mm localized medially in the right intermediary bronchus distal to the upper lobe bronchus and proximal to the middle lobe bronchus. Through the fistula the mediastinal structures and the stapler sutures of the anastomosis were visible. Gastroscopy revealed the gastroesophageal anastomosis located 30 cm from the incisor line. In the stapler row at the edge of the anastomosis, there was an oval fistula with maximum length of 10 mm. Intubation and mechanical ventilation was established. Ventilator readings showed a considerable gas leakage caused by gas escaping and emptying via the bronchial fistula to the mediastinum and the gastroesophageal fistula. To cover the perforation to reduce air leakage an endoluminal 105 mm long partially covered Wall flex stent with core diameter 23 mm and end diameter 28 mm (lot. 1444010, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA,) was placed in the esophageal and gastric remnant. This stent was covered with a thin polyurethane layer except from the bare distal and proximal 1,5 cm that reduces the risk for migration. This wide diameter stent was also considered beneficial by reducing the peristalsis in the gastric conduit and thus improve the tegmentation of the GBF. The leakage of gas through the fistula was minimalized by using low peak airway pressures during mechanical ventilation, being reduced from 20 to 8 mm Hg. Two days later a thoracic CT scan demonstrated bilateral pleural effusion, lung consolidation and a small but visible fistulous communication from the gastric tube to the rigth intermediary bronchus (Fig. 2). On day 18 postoperatively percutaneous tracheotomy was performed. His general condition improved with resolution of the pleural effusion and pneumonia (Fig. 3) and allowed extubation on day 29 postoperatively. The stent was removed on day 35, and both gastroscopy and bronchoscopy confirmed that the fistula was healed.

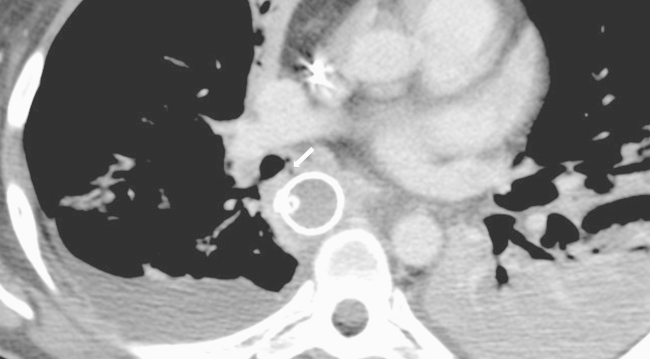

Fig. 2.

A CT scan without contrast demonstrating the fistula between the gastric tube and the right intermediary bronchus (arrow), bilateral pleural effusion and lung consolidation.

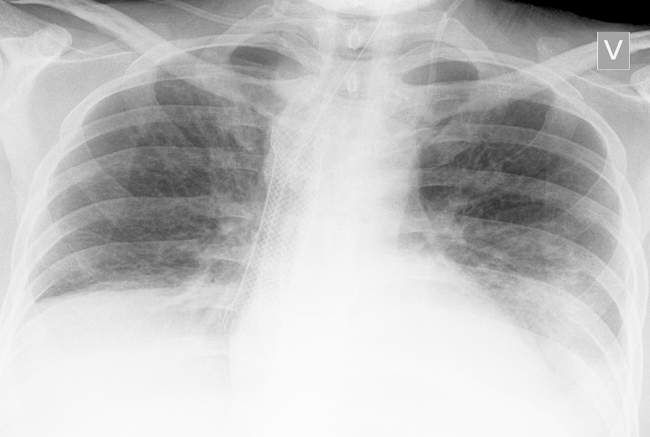

Fig. 3.

A chest X-ray demonstrating stent in place (arrow) and resolution of lung changes.

The patient was discharged from hospital 2 days later and was followed in the out-patient clinic. The postoperative course was uncomplicated until recurrence after 9 months and ultimately death from mediastinal and pulmonary metastases 11 months postoperatively.

3. Discussion

We outline the treatment of a high risk patient who had MD type 1 and esophageal cancer.

The reports on surgery in patients with DM are limited [2], [3], [6]. In the largest series of 219 cases [3], the patients had either limited peripheral surgery including procedures on eye, nose and throat and vagina, or abdominal operations like hysterectomy, tubal ligation, appendectomy, cesarean section and cholecystectomy. Concerning thoracic surgery we found only one series of six patients with MD type 1 and Barlow disease [6] who had complex mitral valve surgery during hypothermic cardiopulonary bypass and cardioplegia. MIE for esophageal cancer in a patient with DM has not been previously reported. Our patient had a protracted postoperative course until respiratory failure on the 15th postoperative day caused by the fistula. We had considered MIE an acceptable surgical alternative in order to minimize the risk for respiratory complications in this high risk patient. In order to reduce air leakage from the fistula and improve conditions for healing, a self expandable stent was placed in the gastric remnant. In addition, low ventilator pressures (8–10 mm Hg) was considered beneficial for healing of the fistula. Some degree of hypercapnia was accepted with these ventilator settings.

The fistula was probably caused by thermal injury of the right bronchus by the close dissection with Ligasure 5 mm with blunt tip. When using Ligasure the heat transmission is known to be within 2 mm from the jaw of the instrument (Covidien). The fistula development probably started with ischemic necrosis of the intermediate bronchus creating a fistulous tract that advanced into the anastomosis. Erosive injury by the staples can not be excluded. This is, however, considered less likely since the staplers do not transgress the lateral edge of the transected tissue of the intact gastric remnant. Non-surgical intervention caused healing of the fistula in our case. Open surgery for the bronchial fistula [7], [8] in this patient, with closure of the bronchial defect by suture, or with interponated tissue (pleura, oment or muscular flap) was considered as having an unacceptable risk.

The optimal treatment for gastrobronchial and gastrotracheal fistulas after posterior route mediastinal esophagectomy and intrathoracic esophagogastric anastomosis is still controversial, because of variable results with a high incidence of serious morbidity and considerable mortality [9], [10]. The mainstay of treatment is surgical in one or two stages depending on severity of the leakage, size of the fistula, blood supply of the conduit and the general health of the patient. One stage surgery comprises closure of the defect in the airways and the conduit with buttressing with interponate of oment, pleura or more often a pedicled muscle flap. Surgery in two stages usually include (i) total or partial resection of the conduit, and closure or more seldom resection of the airway defect with lobectomy, (ii) exteriorization of proximal esophagus (esophagostomy) and nutrition by a jejunal cathether. In the second stage the continuity of the gut is restored either with an anastomosis between esophagus and the initial but partially resected conduit or by colon or jejunum. Of the 44 patients reported with tracheobronchial fistula after surgery regardless of etiology [9], [11], 14 patients developed gastrobronchial fistula after esophagectomy for cancer and the mean mortality rate was 25% (range 0–100%). If conservative treatment can reduce this high mortality it should be attempted. Esophagogastric stenting of a dehisced anastomosis per se has in recent years shown promising results [12] with increased healing rates and survival compared with external and nasogastric drainage. However, stent migration has been reported in as many as 37.5% of patients [13] when using the self expandable plastic and covered Polyflex stent. Publications on stenting for GBF after esophagectomy for cancer within one month (early) and after 2–4 months (late) after surgery without recurrent cancer is limited [10], [14], [15]. Fistulas to the right and left main stem bronchus in 6 patients were reported. In three of the four early postoperative fistulas healing occurred (75%) and the patients survived. In one of these survivors stenting of trachea was also necessary in order to seal the the fistula. The fourth patient had a covered tracheal stent inserted for the presumed proximal gastrobronchial fistula, but died from respiratory problems and sepsis. The two patients with late fistulas were, in one case stented twice with 2 months interval due to distal stent migration. In the other case the patient was too debilitated to undergo surgical repair of the fistula and the initial treatment was insertion of an uncovered self-expanding metal stent but he fistula remained unhealed. Therefore an Amplatzer Septal Occluder composed of nitinol metal and polyester fabric was successfully introduced and closed the fistula. The patient subsequently had no airway symptoms but was readmitted to hospital after 4 weeks with Streptococcus milleri sepsis complicated with cerebral abscesses and died after two weeks. Stents used in the 6 patients were Polyflex stents of length 12 cm and diameter 25 mm (Rusch AG, Wiesbaden, Germany) and covered or uncovered Ultraflex stents of length 12 cm and diameter 18 mm (Boston Scientific, Natic, MA). Accordingly, overall stent migration occurred in one of six patients (16,7%) and the mortality rate was 2 of 6 patients (33,3%).

Stent migration and subsequent endoscopic manipulation and restenting may disturb the healing of the fistula. Use of covered stent is mandatory to seal the fistula, and thereby minimize leakage of air and digestive juice through the fistula. However, use of a stent which is exclusively uncovered in both ends, like the partially covered Wall flex stent used in the patient with DM, would presumable be more strongly anchored to the esophageal and gastric mucosa and accordingly exhibit less potential for migration. There is lower frequency of stent migration by using self expanding stents of metal (Ultraflex and Wall stent) (7,6%) instead of plastic (Polyflex stent) (57%) [16]. When considering stenting of a GBF communicating with the esophagogastric anastomosis adequate blood supply of the gastric conduit is important. In additon, the smaller the fistula opening (tentatively <7–8 mm) the greater is the possibility of fistula healing on the ariway side. Often stenting may be the only treatment option in a patient too debilitated for surgery. In a patient with a well-circulated conduit gastrobronchial fistula stenting should be considered as a first treatment option, but surgery, when needed, must be carried out if this is not successful.

In case of our patient with MD we are of the opinion that surgery would have been a high risk procedure because of myopathy of respiratory muscles.

4. Conclusions

Gastrobronchial fistula is a rare and potentially lethal complication following esophagectomy for cancer, especially in a patient with MD type 1 and ventilatory insufficiency because of respiratory muscle myopathy. The fistula was most likely caused by Ligasure induced thermal injury during dissection resulting in ischemic necrosis of the intermediary bronchus. Limited gastrobronchial fistulas may be successfully treated with stenting of the gastric remnant in order to seal the fistula. Low pressure ventilation probably improves healing. Our case demonstrates that MIE can be an acceptable surgical method for the treatment of esophageal cancer in MD patients.

In patients with well-circulated gastric conduit and limited size of the gastrobronchial fistula from the esophagogastric anastomosis to the main bronchi, insertion of a stent should be considered as a relevant treatment option.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

None.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's next of kin for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the management of the patient. S.H. and E.J. were involved in concept, design and writing of the manuscript. H.O.J., B.H., K.O. and H.M. contributed to critical revision of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Silje Hugin, Email: silje.hugin@gmail.com.

Egil Johnson, Email: egil.johnson@medisin.uio.no.

Hans-Olaf Johannessen, Email: uxhojo@ous-hf.no.

Bjørn Hofstad, Email: uxbjho@ous-hf.no.

Kjell Olafsen, Email: uxkjol@ous-hf.no.

Harald Mellem, Email: uxhame@ous-hf.no.

References

- 1.Meola G., Cardani R. Myotonic dystrophies: an update on clinical aspects, genetic, pathology, and molecular pathomechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;852(4):594–606. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basinotto F.M., Fabri D.C., Calçado M.S., Perfeito P.B., Tostes L.V., Sousa G.D. Anesthesia for videolaparoscopic cholecystectomy in a patient with Steinert disease: case report and review of the literature. Rev. Bras. Anesthesiol. 2010;60(2):181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0034-7094(10)70024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathieu J., Allard P., Gobeil G., Girard M., De Braekeleer M., Bégin P. Anesthetic and surgical complications in 219 cases of myotonic dystrophy. Neurology. 1997;49(6):1646–1650. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.6.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gadalla S.M., Lund M., Pfeiffer R.M., Gørtz S., Mueller C.M., Moxley R.T., 3rd, Kristinsson S.Y., Bjӧrkholm M., Shebl F.M., Hilbert O., Landgren J., Wohlfahrt M., Greene M.H. Cancer risk among patients with myotonic muscular dystrophy. JAMA. 2011;306(22):2480–2486. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy R.M., Trivedi D., Luketich J.D. Minimally invasive esophagectomy. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2012;92(5):1265–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelsomino S., Lorusso R., Billé G., De Cicco G., Da Broi U., Rostagno C., Stefàno P., Gensini G.F. Cardiac durgery in type-1-myotonic dystrophy (Steinert syndrome) associated to Barlow disease. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2008;7(2):222–226. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2007.171611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jha P.K., Deiraniya A.K., Keeling-Roberts C.S., Das S.R. Gastrobronchial fistula a recent series. Interact Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2003;2(1):6–8. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9293(02)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibuki Y., Hamai Y., Hihara J., Taomoto J., Kishimoto I., Miyata Y., Okada M. Emergency escape surgery for a gastro-bronchial fistula with respiratory failure that developed after esophagectomy. Surg. Today. 2015;45(3):369–373. doi: 10.1007/s00595-013-0821-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morita M., Saeki H., Okamoto T., Oki E., Yoshida S., Maehara Y. Tracheobronchial fistula during the perioperative period of esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. World. J. Surg. 2015;39(5):1119–1126. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-2945-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scweigert M., Dubecz A., Beron M., Muschweck H., Stein H.J. Management of anastomotic leakage-induced tracheobronchial fistula following esophagectomy: the role of endoscopic stent insertion. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2012;41(5):e74–e80. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezr328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yasadu T., Sugimura K., Yamasaki M., Miyata H., Motoori M., Yano M., Shiozaki H., Mori M., Doki Y. Ten cases of gastro-tracheobronchial fistula: a serious complication after esophagectomy and reconstitution using posterior mediastinal gastric tube. Dis. Esophagus. 2012;25(8):687–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kauer W.K., Stein H.J., Dittler H.J., Siewert J.R. Stent implantation as a treatment option in patients with thoracic anastomotic leaks after esophagectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2008;22(1):50–53. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langer F.B., Wenzl E., Prager G., Salat A., Miholic J., Mang T., Zacherl J. Management of post-operative esophageal leaks with the polyflex self expandable covered plastic stent. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2005;79(2):398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.07.006. discussion 404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bona D., Sarli D., Saino G., Quarenghi M., Bonavina L. Successful conservative management of benign gastro-bronchial fistula after intrathoracic esophagogastrostomy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007;84(3):1036–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green D.A., Moskowitz W.B., Sheperd R.W. Closure of a broncho-to-neoesophageal fistula using an Amplatzer Septal Occluder device. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2010;89(6):2010–2012. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubecz A., Watson T.J., Raymond D.P., Jones C.E., Matousek A., Allen J., Salvador R., Polomsky M., Peters J.H. Esophageal stenting for malignant and benign disease: 133 cases on thoracic surgical service. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011;92(6):2028–2032. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]