Abstract

Context:

A single measurement of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25 [OH] D) may not accurately reflect long-term vitamin D status. Little is known about change in 25(OH)D levels over time, particularly among blacks.

Objective:

The objective of the study was to determine the longitudinal changes in 25(OH)D levels among Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study participants.

Design:

This was a longitudinal study.

Setting:

The study was conducted in the general community.

Participants:

A total of 9890 white and 3222 black participants at visit 2 (1990–1992), 888 whites and 876 blacks at visit 3 (1993–1994), and 472 blacks at the brain visit (2004–2006) participated in the study.

Main Outcome Measure:

The 25(OH)D levels were measured, and regression models were used to assess the associations between clinical factors and longitudinal changes in 25(OH)D.

Results:

Vitamin D deficiency (<50 nmol/L [<20 ng/mL]) was seen in 23% and 25% of whites at visits 2 and 3, and in 61%, 70%, and 47% of blacks at visits 2, 3, and the brain visit, respectively. The 25(OH)D levels were correlated between visits 2 and 3 (3 y interval) among whites (r = 0.73) and blacks (r = 0.66). Among blacks, the correlation between visit 2 and the brain visit (14 y interval) was 0.33. Overall, increases in 25(OH)D levels over time was associated with male gender, use of vitamin D supplements, greater physical activity, and higher high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (P < .001). Decreases in 25(OH)D levels over time were associated with current smoking, higher body mass index, higher education, diabetes, and hypertension (all P < .05).

Conclusions:

Among US blacks and whites, 25(OH)D levels remained relatively stable over time. Certain modifiable lifestyle factors were associated with change in 25(OH)D levels over time.

25-Hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) deficiency has been associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (1), hypertension (2), diabetes (3), and all-cause mortality (4, 5). Most of the observational data linking suboptimal 25(OH)D levels to adverse health outcomes has been based on single baseline measurements of 25(OH)D in individuals. However, there is considerable variation in 25(OH)D level within an individual by season (6, 7), suggesting that a single baseline measurement may not accurately reflect long-term vitamin D status.

No observational study in the United States has reported longitudinal measurements of 25(OH)D within the same individual, and population-based studies of the temporal changes in vitamin D status in the United States were based on serial cross-sectional measurements of 25(OH)D level in different subjects (8, 9). The few studies that examined longitudinal variation in 25(OH)D levels (10–12) have been conducted predominantly among white participants residing in high latitudes outside the United States. Because black adults generally have a lower 25(OH)D level compared with whites (4), the longitudinal changes in 25(OH)D level in this population remain largely unknown.

We sought to examine longitudinal changes in vitamin D status through serial 25(OH)D measurements in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, a large, well-characterized cohort including a significant number of participants who are black and reside in southern latitudes in the United States. We also sought to assess demographic, behavioral, and comorbid factors associated with change in 25(OH)D level over time. We hypothesized that 25(OH)D levels would be reasonably correlated over time among whites and blacks but that certain clinical characteristics (such as elevated body mass index [BMI], decreased physical activity, and smoking) would be associated with decreasing levels over time.

Materials and Methods

Study population

The ARIC study is an ongoing, community-based prospective cohort of 15 792 adults aged 45–65 years at the first visit (1987–1989) recruited from four US communities (listed with their respective latitudes): Minneapolis, Minnesota (44.98° N); Washington County, Maryland (39.60° N); Forsyth County, North Carolina (36.13° N); and Jackson, Mississippi (32.30° N) (13).

ARIC visit 2 was conducted between 1990 and 1992 and was attended by 14 348 white and black participants. 25(OH)D was measured from samples taken at visit 2, which will serve as the baseline for this study. The ARIC Brain MRI ancillary study included a subset of ARIC participants who were aged 55 years or older from the Forsyth County and Jackson sites only that were invited for a cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cognitive testing during the first 2 years of ARIC visit 3 (1993–1994) (14). Excluded were those with a contraindication to MRI or declined MRI. 25(OH)D was again measured at ARIC visit 3 among white and black subjects participating in the ARIC Brain MRI ancillary study.

A subset of individuals enrolled in this ARIC Brain MRI ancillary study returned for a follow-up visit in 2004–2006 (ARIC Brain MRI visit [brain visit]). Although more than 1100 individuals participated in this later brain visit, stored plasma (related to an ancillary proposal) was available for only a third measurement of 25(OH)D for 494 participants from the Jackson site (all blacks) and 20 whites for Forsythe County.

Excluded from the analysis are participants at visit 2 who self-identified as neither black nor white (n = 42), blacks from the Minnesota and Maryland centers (n = 49; because of the small numbers these individuals are not thought to represent their communities), and whites at the brain visit (n = 20). Also excluded where those with missing 25(OH)D data (n = 1097 for visit 2, n = 165 for visit 3, n = 2 for the brain visit). This led to an analytical study sample of 9890 whites and 3222 blacks at visit 2 (baseline), 888 whites and 876 blacks at visit 3, and 472 blacks at the brain visit.

The Institutional Review Boards at all ARIC study sites approved study protocols and all participants provided written informed consent at each study visit.

Measurement of 25(OH)D

25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 levels were measured from serum samples (visits 2 and 3) or plasma samples (brain visit) using liquid chromatography-tandem high-sensitivity mass spectrometry (Waters Alliance e2795) (15). All samples were stored at −70°C until analyzed in 2012–2013. Using samples collected in duplicate tubes and stored, the coefficient of variation (processing plus assay variation) for 25(OH)D2 was 20.8% and for 25(OH)D3 was 6.9%. The Pearson correlations (mean differences) from the blind duplicate samples at visit 2 were 0.98 (−0.04) for 25(OH)D2 and 0.97 (−0.38) for 25(OH)D3. The intraclass correlation coefficients at visit 2 from the blind duplicate samples, calculated by the function icc in the R package irr, were as follows: 0.96 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.95–0.96) for 25(OH)D2 and 0.91 (0.86–0.92) for 25(OH)D3. Blind duplicate samples were not available at ARIC visit 3 or the Brain MRI visit to calculate the intraclass correlation coefficient for those latter specimens. 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 were added together for total 25(OH)D concentration. To convert 25(OH)D levels from nanomoles per liter to nanograms per milliliter, divide by 2.496.

Seasonally adjusted vitamin D

25(OH)D levels vary by season (6). Therefore, we adjusted 25(OH)D for seasonal variation by computing the residuals from a linear regression model with 25(OH)D level as the dependent variable and month of blood draw as the independent variable (15). By definition, these residuals are not correlated with month of blood draw. The grand mean was then added to the vitamin D residuals obtained from this model. We performed this adjustment separately for whites and blacks because seasonal variation in 25(OH)D concentrations also varies by race. This new variable, vitamin D adjusted for month of blood draw, is an estimate of average annual 25(OH)D levels and was used as the outcome variable in the analyses. Of note, seasonal adjustment by this residual approach gives very similar 25(OH)D values to a seasonally adjusted 25(OH)D using a Cosinor approach, which other authors have used (16). The Pearson correlation between 25(OH)D adjusted by the Cosinor method and by the residual method is 0.997.

Adjusted 25(OH)D levels of 50 nmol/L or greater (≥20 ng/mL) were considered adequate (replete) for health per the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendations (17), and levels less than 50 nmol/L (<20 ng/mL) were considered deficient. The IOM report indicated that levels greater than 50 nmol/L should cover the requirements of at least 97.5% of the population. The IOM also noted that levels of 40 nmol/L or greater (≥16 ng/mL) should meet the requirements for approximately half of the population; as such, not everyone with levels less than 50 nmol/L are truly deficient. In a sensitivity analysis, we also explored the cut point of 40 nmol/L (16 ng/mL).

Covariate factors

All variables used in the analyses were assessed at visit 2 (1990–1992), visit 3 (1993–1994), and the brain visit (2004–2006), unless otherwise stated. We examined demographic and lifestyle factors potentially associated with change in 25(OH)D levels including the following: age (years, continuous), sex (male; female), race/center (whites in Minneapolis, Minnesota; whites in Washington County, Maryland; whites in Forsyth County, North Carolina; blacks in Forsythe County, North Carolina; blacks in Jackson, Mississippi), education (<high school; high school or vocational school; college, graduate, or professional school; assessed at visit 1), physical activity (score range 1–5, based on replies to the modified Baecke Physical Activity questionnaire [18] assessed at visit 1 and visit 3), cigarette smoking (current; former; never), current alcohol intake (yes, no), and BMI (categories of <20; 25 to <30; ≥30 in weight [kilograms]/height [square meters]).

A survey questionnaire specifically designed to assess vitamin intake was done only at visit 3. However, participants were asked to bring in their medications at each visit, and medication data including nutritional products was coded at visit 2, visit 3, and the brain visit. Multivitamins or other nutritional products containing vitamin D were coded as vitamin D supplement use (yes/no). Note that there might be differences in ascertainment of vitamin D supplement status between visit 3 when the vitamin survey was used compared with the other visits during which only medication data were recorded.

We also examined health conditions that may be associated with 25(OH)D including the following: diabetes (yes/no; defined by self-reported physician diagnosis, medication use, fasting serum glucose ≥7 mmol/L [≥126 mg/dl] or nonfasting glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L [≥200 mg/dL], assessed at visit 2 and visit 3), hypertension (yes/no; defined by self-reported physician diagnosis, medication use, systolic blood pressure [BP] ≥140 mm Hg, or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg), total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol ([continuous per millimoles per liter], assessed at visits 2 and 3), and categories of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the CKD-Epi equation (19) ([<30, 30 to <60; 60 to <90; ≥90 mL/min per 1.73 m2], assessed at visit 2).

Statistical analyses

Characteristics of the study population were described at visit 2, visit 3, and the brain visit stratified by race using means and proportions. We used Bland Altman plots (20) to assess how far the 25(OH)D measurements differ from each other at each visit and whether the difference is dependent on the magnitude of the measurement. In a supplementary analysis, we also used Pearson correlations (r) to examine the correlation between 25(OH)D levels at visit 2 vs visit 3 (median difference 3 y) separately by race. The correlations between 25(OH)D levels at visit 3 vs the brain visit (median difference 11 y) and between visit 2 vs the brain visit (median difference 14 y) were available only in blacks.

To assess the longitudinal association between baseline clinical factors (measured at visit 2) and change in vitamin D level across three time points, we used a random-intercept linear mixed model for longitudinal data. Repeated 25(OH)D measurements over time in the same participant were accounted for, and random variations in baseline 25(OH)D levels were allowed for across participants. Results were stratified by race. The longitudinal associations of 25(OH)D and baseline clinical factors (selected a priori based on known associations with vitamin D) were evaluated in the mixed model, which provided the average longitudinal change (in nanomoles per liter) of seasonally adjusted 25(OH)D level, associated with differences in baseline covariate values across study subjects.

The risk of becoming vitamin D deficient at each follow-up visit and its determinants were evaluated using logistic regression models (participants with 25[OH]D deficiency at baseline were excluded from this analysis). We used three models with increasing degrees of adjustment. Model 1 included demographic variables (age, sex, and race/center); model 2 included behavioral variables (supplement use containing vitamin D, education, BMI, smoking status, current alcohol drinking status, physical activity) in addition to the variables in model 1; and model 3 included all variables in models 1 and 2 plus hypertension, diabetes, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, and eGFR categories.

All statistical analyses were conducted by Stata version 12 (StataCorp). Two-sided values of P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The clinical characteristics of the participants stratified by race and by visit are presented in Table 1. Among whites, overall mean (±SD) 25(OH)D levels were 65.0 ± 20.8 nmol/L at visit 2 and 63.5 ± 19.9 nmol/L at visit 3. Supplement use containing vitamin D was 21% at visit 2 and 32% at visit 3 among whites. As anticipated, lower 25(OH)D levels were seen among blacks with a mean level of 47.0 ± 16.8 nmol/L at visit 2, 43.5 ± 15.8 nmol/L at visit 3, and 53.2 ± 17.5 nmol/L at the brain visit. Among blacks, vitamin D supplement use increased from 14% at visit 2 to 25% at visit 3 to 46% at the brain visit. Vitamin D deficiency (<50 nmol/L) was seen in 23% and 25% of whites at visit 2 and 3, respectively, and in 62%, 70%, and 47% of blacks at visit 2, visit 3, and the brain visit, respectively. Clinical characteristics of vitamin D supplement (or multivitamin) users and nonusers at visit 2 are displayed in Supplemental Table 1. When considering only the complete sample for those who attended both visit 2 and visit 3, the mean (SD) 25(OH)D at visit 2 and 3 was 68.6 (21.8) and 63.5 (19.9) nmol/L for whites and 49.9 (16.5) and 43.5 (15.8) nmol/L for blacks, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants by Race and Visita

| Overall |

Whites |

Blacks |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Brain MRI Visit | |

| n | 13 112 | 1764 | 9890 | 888 | 3222 | 876 | 472 |

| 25(OH)D, nmol/L | 60.6 (21.4) | 53.6 (20.6) | 65.0 (20.8) | 63.5 (19.9) | 47.0 (16.8) | 43.5 (15.8) | 53.2 (17.5) |

| Supplement use with vitamin D, n, % | 2516 (19.2) | 507 (28.7) | 2053 (20.8) | 286 (32.2) | 463 (14.4) | 221 (25.2) | 218 (46.0) |

| Deplete (25[OH]D <50 nmol/L), n, % | 4274 (32.6) | 833 (47.2) | 2290 (23.2) | 223 (25.1) | 1984 (61.6) | 610 (69.6) | 220 (46.6) |

| Age, y | 56.9 (5.7) | 62.4 (4.5) | 57.1 (5.7) | 63.2 (4.4) | 56.2 (5.8) | 61.7 (4.5) | 72.2 (4.1) |

| Male, n, % | 5697 (43.4) | 710 (40.2) | 4545 (46.0) | 389 (43.8) | 1152 (35.8) | 321 (36.6) | 163 (34.5) |

| Center, n, % | |||||||

| Forsyth County, North Carolina | 3326 (25.4) | 995 (56.4) | 2981 (30.1) | 888 (100.0) | 345 (10.7) | 107 (12.2) | 0 |

| Jackson, Mississippi | 2831 (21.6) | 769 (43.6) | 0 | 0 | 2831 (87.9) | 769 (87.8) | 472 (100.0) |

| Minneapolis, Minnesota | 3548 (27.1) | 0 | 3531 (35.7) | 0 | 17 (0.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Washington County, Maryland | 3407 (26.0) | 0 | 3378 (34.2) | 0 | 29 (0.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Education, n, %b | |||||||

| <High school | 2804 (21.4) | 483 (27.4) | 1548 (15.7) | 130 (14.6) | 1256 (39.1) | 353 (40.4) | 172 (36.6) |

| High school or vocational school | 5471 (41.8) | 603 (34.2) | 4551 (46.1) | 384 (43.2) | 920 (28.6) | 219 (25.1) | 109 (23.2) |

| College, graduate, or professional school | 4816 (36.8) | 676 (38.4) | 3779 (38.3) | 374 (42.1) | 1037 (32.3) | 302 (34.6) | 189 (40.2) |

| Smoking status, n, % | |||||||

| Never | 5284 (40.4) | 786 (44.7) | 3817 (38.6) | 358 (40.4) | 1467 (45.8) | 428 (49.0) | 281 (60.3) |

| Former | 4929 (37.7) | 653 (37.1) | 4007 (40.5) | 369 (41.6) | 922 (28.8) | 284 (32.5) | 157 (33.7) |

| Current | 2877 (22.0) | 321 (18.2) | 2064 (20.9) | 160 (18.0) | 813 (25.4) | 161 (18.4) | 28 (6.0) |

| Current alcohol consumption, n, % | |||||||

| No | 5701 (43.6) | 1100 (62.5) | 3583 (36.2) | 469 (52.8) | 2118 (66.1) | 631 (72.3) | 365 (77.3) |

| Yes | 7388 (56.4) | 661 (37.5) | 6304 (63.8) | 419 (47.2) | 1084 (33.9) | 242 (27.7) | 107 (22.7) |

| Physical activity indexc | 2.4 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.2 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.7) | NA |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.9 (5.4) | 28.0 (5.2) | 27.3 (4.9) | 26.5 (4.6) | 30.0 (6.2) | 29.5 (5.3) | 30.5 (5.2) |

| Diabetes, n, % | 1923 (14.7) | 324 (18.4) | 1138 (11.5) | 99 (11.1) | 785 (24.6) | 225 (25.8) | NA |

| Hypertension, n, % | 4680 (35.8) | 851 (48.5) | 2906 (29.4) | 295 (33.3) | 1774 (55.4) | 556 (64.1) | 372 (82.7) |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.4 (1.0) | 5.4 (1.0) | 5.4 (1.0) | 5.4 (0.9) | 5.4 (1.1) | 5.4 (1.0) | NA |

| HDL, mmol/L | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.5) | NA |

| LDL, mmol/L | 3.5 (1.0) | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.2 (0.8) | 3.5 (1.0) | 3.3 (1.0) | NA |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.3 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.7) | NA |

| PTH, pmol/L | 4.5 (2.5) | 4.9 (3.3) | 4.2 (1.6) | 4.4 (2.7) | 5.3 (4.2) | 5.4 (3.7) | NA |

| Calcium, mmol/L | 2.3 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | 2.3 (0.1) | 2.3 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | NA |

| Phosphate, mmol/L | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.2) | NA |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 96.3 (15.8) | NA | 94.0 (13.1) | NA | 103.3 (20.6) | NA | NA |

| eGFR categories, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | |||||||

| <30 | 30 (0.2) | NA | 4 (0.0) | NA | 26 (0.8) | NA | NA |

| 30 to <60 | 247 (1.9) | NA | 168 (1.7) | NA | 79 (2.5) | NA | NA |

| 60 to <90 | 3330 (25.4) | NA | 2697 (27.3) | NA | 633 (19.6) | NA | NA |

| ≥90 | 9505 (72.5) | NA | 7021 (71.0) | NA | 2484 (77.1) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: LDL, low-density lipoprotein; NA, not available.

Data are means (SD) or number (percentage).

Education information for visits 2 and 3 is derived from visit 1 (1987–1989).

Physical activity index for visit 2 is derived from visit 1 (1987–1989).

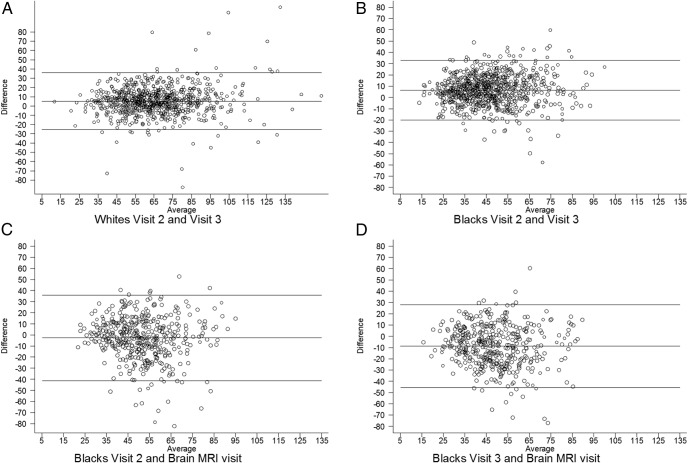

The agreement of 25(OH)D levels between visits as assessed by Bland-Altman plots are shown in Figure 1. The mean difference in nanomoles per liter and 95% CI are as follows: for whites between visits 2 and 3, 5.28 (4.51 to 6.04); for blacks between visit 2 and 3: 6.51 (5.92 to 7.10); for blacks between visit 2 and brain visit, −2.61 (−3.68 to −1.55); and for blacks between visit 3 and brain visit, −8.66 (−9.67 to −7.64).

Figure 1.

Bland-Altman plots assessing the correlation of 25(OH)D levels between visit 2 and visit 3 for whites (median 3 y) (A); between visit 2 and visit 3 for blacks (median 3 y) (B), between visit 2 and brain visit for blacks (median 14 y) (C); and between visit 3 and brain visit for blacks (median 11 y) (D).

The correlations of 25(OH)D levels between visits by Pearson's correlations (r) are shown in Supplemental Figure 1. As anticipated, correlations were stronger between visits 2 and 3 (3 y interval) than between visit 2 or 3 and the brain visit (14 or 11 y interval, respectively). The correlation coefficient of 25(OH)D levels between visits 2 and 3 was 0.73 in whites and 0.66 in blacks. Among blacks, the correlation coefficient was lower between visit 2 and the brain visit (r = 0.33, median duration 14 y) and between visit 3 and the brain visit (r = 0.39, 11 y interval). For comparison with other CVD risk factors, the correlation between visit 2 and visit 3 for systolic BP was 0.71 for whites and 0.60 for blacks (excluding those on antihypertensive medication), and for total cholesterol, the correlation was 0.68 for whites and 0.75 for blacks (excluding those for on lipid therapy). The correlation for systolic BP (r = 0.41) and diastolic BP (r = 0.25) among blacks between visit 2 and the brain visit was similar to the correlation for 25(OH)D level (cholesterol was not measured again at the brain visit).

Table 2 describes the associations of baseline clinical factors with longitudinal change in 25(OH)D levels over time for overall population attending each visit. White participants contributed only to visit 2 and visit 3 (median 3 y), whereas black participants could contribute to baseline visit 2, visit 3, and the brain visit (up to 14 y), as available. Among whites, in fully adjusted model 3, increasing 25(OH)D levels were associated with male sex, use of supplements containing vitamin D, greater physical activity, and greater HDL and total cholesterol. Decreasing 25(OH)D levels over time in whites were associated with increasing age, greater BMI, higher education, current smoking, and diabetes. The association with renal function was mixed. Compared with whites with normal renal function (eGFR ≥90 mL/min per 1.73 m2), those with eGFRs of 30–60 and 60–90 had higher and those with eGFR less than 30 had lower 25(OH)D levels over time. Among blacks, increasing age, male sex, use of supplements containing vitamin D, physical activity, and greater HDL cholesterol were associated with increases in 25(OH)D levels, whereas higher education, current drinking, and hypertension were associated were decreasing 25(OH)D levels. Among blacks, compared with those with a normal eGFR of 90 mL/min per 1.73 or greater, those with eGFR of 60–90 had increases in 25(OH)D levels over time.

Table 2.

Association Between Baseline Systemic Risk Factors (Measured at Visit 2 Unless Noted) and Trajectory of Vitamin D (per Nanomoles per Liter of 25 [OH]D)

| Overall |

White |

Black |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |

| Participants/visits, n | 13 260/15 322 | 13 150/15 202 | 12 836/14 827 | 9993/10 798 | 9940/10 743 | 9769/10 561 | 3313/4570 | 3256/4505 | 3113/4312 |

| Age, 10 y | 1.61 (1.05, 2.16) | 0.77 (0.23, 1.32) | 0.22 (−0.36, 0.80) | 0.81 (0.11, 1.50) | 0.04 (−0.64, 0.71) | −0.77 (−1.48, −0.05) | 3.52 (2.65, 4.39) | 2.50 (1.62, 3.38) | 2.51 (1.58, 3.44) |

| Male | 5.19 (4.56, 5.81) | 5.13 (4.49, 5.78) | 6.51 (5.80, 7.21) | 4.57 (3.79, 5.35) | 4.66 (3.86, 5.47) | 6.67 (5.78, 7.56) | 6.85 (5.87, 7.83) | 7.22 (6.17, 8.27) | 7.78 (6.66, 8.89) |

| Vitamin D supplement use | 8.02 (7.26, 8.79) | 7.94 (7.17, 8.71) | 7.74 (6.82, 8.67) | 7.77 (6.84, 8.69) | 8.86 (7.57, 10.15) | 8.51 (7.19, 9.83) | |||

| Educationd | |||||||||

| <High school | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| High school | −2.09 (−2.92, −1.25) | −2.20 (−3.04, −1.36) | −1.83 (−2.97, −0.69) | −2.08 (−3.22, −0.95) | −2.53 (−3.70, −1.35) | −2.51 (−3.71, −1.31) | |||

| ≥College | −4.10 (−4.97, −3.24) | −4.46 (−5.33, −3.58) | −4.29 (−5.50, −3.08) | −4.84 (−6.05, −3.63) | −2.88 (−4.02, −1.74) | −3.10 (−4.27, −1.93) | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||||||||

| <25 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 25 to <30 | −2.85 (−3.58, −2.12) | −2.07 (−2.82, −1.32) | −3.04 (−3.92, −2.17) | −2.26 (−3.15, −1.36) | −0.54 (−1.84, 0.77) | 0.15 (−1.21, 1.51) | |||

| ≥30 | −6.85 (−7.65, −6.04) | −5.10 (−5.96, −4.23) | −8.17 (−9.19, −7.15) | −6.32 (−7.41, −5.24) | −2.58 (−3.91, −1.26) | −1.17 (−2.60, 0.26) | |||

| Smoking | |||||||||

| Never | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Former | 0.48 (−0.23, 1.18) | 0.57 (−0.14, 1.28) | 0.52 (−0.35, 1.39) | 0.57 (−0.30, 1.44) | 0.41 (−0.72, 1.53) | 0.50 (−0.64, 1.65) | |||

| Current | −3.18 (−4.01, −2.35) | −2.56 (−3.40, −1.72) | −4.09 (−5.13, −3.05) | −3.37 (−4.42, −2.32) | −0.39 (−1.67, 0.90) | −0.05 (−1.37, 1.28) | |||

| Current drinking | |||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Yes | −0.21 (−0.88, 0.46) | −0.68 (−1.36, 0.01) | 0.30 (−0.54, 1.13) | −0.25 (−1.09, 0.60) | −2.21 (−3.29, −1.13) | −2.40 (−3.51, −1.29) | |||

| Physical activity indexd | 3.62 (3.22, 4.01) | 3.49 (3.09, 3.89) | 4.23 (3.75, 4.71) | 3.96 (3.48, 4.43) | 1.18 (0.48, 1.88) | 1.30 (0.58, 2.01) | |||

| Hypertension | −0.81 (−1.48, −0.13) | −0.33 (−1.20, 0.53) | −1.65 (−2.63, −0.66) | ||||||

| Diabetes | −2.38 (−3.27, −1.49) | −3.38 (−4.60, −2.15) | −0.95 (−2.12, 0.22) | ||||||

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/liter | 4.05 (3.25, 4.84) | 4.95 (3.91, 5.98) | 2.17 (1.01, 3.34) | ||||||

| Total cholesterol, mmol/liter | 0.19 (−0.11, 0.48) | 0.42 (0.05, 0.80) | −0.15 (−0.60, 0.30) | ||||||

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | |||||||||

| ≥90 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 60 to <90 | 3.03 (2.30, 3.75) | 3.45 (2.57, 4.33) | 1.73 (0.51, 2.95) | ||||||

| 30 to <60 | 7.66 (5.42, 9.90) | 9.72 (6.84, 12.59) | 3.01 (−0.25, 6.28) | ||||||

| <30 | −0.08 (−6.27, 6.11) | −29.24 (−48.32, −10.16) | 2.29 (−3.32, 7.91) | ||||||

White participants contributed only to visit 2 and visit 3 (median 3 y), whereas black participants could contribute to baseline visit 2, visit 3, and the ARIC brain visit (up to 14 y). Results in bold font represent statistically significant results (P < .05).

Model 1 (demographic variables) included the following: age, sex, and race/center (overall model) or center (race stratified models).

Model 2 (demographic + behavioral variables) included the following: model 1 + Vitamin D supplementation use, education, BMI, smoking status, current alcohol drinking status, and physical activity.

Model 3 (demographic + behavioral + comorbidities) included the following: model 2 + hypertension, diabetes, HDL-cholesterol, total cholesterol, and eGFR.

Used data from visit 1 (1986–1990) for visit 2.

Supplemental Table 2 describes the associations of clinical factors with longitudinal change in 25(OH)D levels over time restricted to only the complete sample of participants who attended both visit 2 and visit 3 (ie, excludes whites from Minnesota and Maryland who did not have vitamin D measured at visit 3). Associations were similar as described for overall population, and some associations were even stronger.

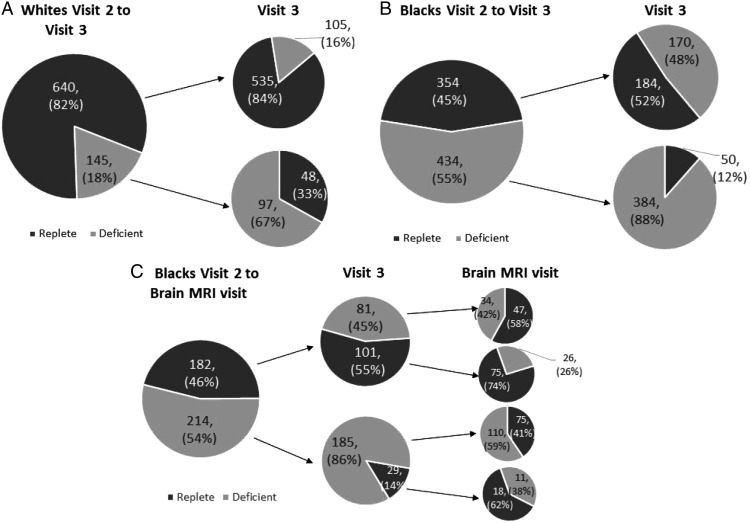

Vitamin D status (deficient/replete) at each time point is displayed in Figure 2 for the complete sample that attended each visit. Between visits 2 and 3, 16% of whites and 48% of blacks that were initially replete became deficient. Conversely, of those initially deficient, 33% of whites and 12% of blacks became replete. Between visit 3 and the brain visit, 26% of blacks that were initially replete became deficient, whereas 41% of blacks initially deficient became replete.

Figure 2.

Change of Vitamin D status across visits for the complete sample who attended each visit. A, Whites who attended visits 2 and 3. B, Blacks who attended visits 2 and 3. C, Blacks who attended visit 2, visit 3, and the brain visit. Pie charts represented proportion of participants with Vitamin D deficiency (monthly adjusted 25(OH)D < 50 nmol/L) and vitamin D sufficiency (monthly adjusted 25(OH)D ≥50 nmol/L) at each visit.

Factors associated with the odds of becoming vitamin D deficient (<50 nmol/L [<20 ng/ml]) among those initially replete are shown in Table 3. Among whites and blacks, male sex and greater physical activity were associated with lower odds of becoming vitamin D deficient between visits 2 and 3 (P < .05). Conversely, college education was associated with greater odds of becoming deficient (P < .05) among both whites and blacks, and current smoking and diabetes were associated with greater odds of becoming deficient among whites only. No factors were statistically significantly associated with becoming vitamin D deficient among blacks between visit 3 and the brain visit, but sample size was smaller.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios (95% CI) for Risk of Vitamin D Deficiency (<50 nmol/L [<20 ng/mL]) Among Those Initially Replete (≥50 nmol/L) by Baseline Clinical Factors (Measured at Visit 2 Unless Noted)

| Visit 2 (1990–1992) to Visit 3 (1993–1995) |

Visit 2 (1990–1992) to Visit 3 (1993–1995) |

Visit 3 (1993–1995) to Brain MRI Visit (2004–2006) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whites |

Blacks |

Blacks |

|||||||

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |

| Cases/subjects, n | 105/640 | 105/638 | 105/634 | 170/354 | 169/350 | 163/341 | 41/142 | 41/141 | 41/141 |

| Age, 10 y | 0.93 (0.58, 1.50) | 0.95 (0.58, 1.58) | 1.02 (0.60, 1.72) | 0.75 (0.47, 1.20) | 0.91 (0.56, 1.50) | 0.93 (0.55, 1.56) | 0.94 (0.37, 2.35) | 1.30 (0.47, 3.63) | 1.07 (0.37, 3.11) |

| Male | 0.47 (0.30, 0.73) | 0.47 (0.28, 0.79) | 0.37 (0.20, 0.66) | 0.40 (0.26, 0.62) | 0.35 (0.22, 0.57) | 0.35 (0.20, 0.61) | 0.93 (0.45, 1.93) | 1.01 (0.44, 2.35) | 0.93 (0.35, 2.47) |

| Use of MVI or | 0.83 (0.49, 1.40) | 0.87 (0.51, 1.49) | 0.75 (0.44, 1.25) | 0.83 (0.49, 1.42) | 0.84 (0.36, 1.98) | 0.78 (0.32, 1.87) | |||

| Educationd | |||||||||

| <High School | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| High school | 1.56 (0.76, 3.18) | 1.67 (0.81, 3.44) | 1.19 (0.68, 2.08) | 1.32 (0.74, 2.36) | 1.11 (0.37, 3.36) | 1.38 (0.42, 4.50) | |||

| ≥College | 1.77 (0.85, 3.67) | 2.14 (1.01, 4.53) | 1.66 (0.95, 2.89) | 1.82 (1.02, 3.24) | 1.18 (0.45, 3.06) | 1.39 (0.51, 3.81) | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||||||||

| <25 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 25 to <30 | 1.26 (0.77, 2.05) | 1.15 (0.69, 1.91) | 1.45 (0.78, 2.69) | 1.50 (0.76, 2.95) | 1.45 (0.41, 5.15) | 1.27 (0.35, 4.61) | |||

| ≥30 | 1.90 (1.00, 3.60) | 1.69 (0.86, 3.35) | 1.00 (0.52, 1.91) | 1.09 (0.53, 2.26) | 3.56 (1.00, 12.61) | 2.54 (0.67, 9.58) | |||

| Smoking | |||||||||

| Never | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Former | 1.26 (0.74, 2.15) | 1.30 (0.75, 2.25) | 1.18 (0.70, 1.99) | 1.16 (0.68, 2.00) | 1.31 (0.55, 3.14) | 1.36 (0.56, 3.33) | |||

| Current | 2.04 (1.15, 3.61) | 2.06 (1.15, 3.70) | 1.13 (0.59, 2.17) | 1.24 (0.62, 2.50) | 2.13 (0.63, 7.23) | 2.57 (0.72, 9.21) | |||

| Current drinking | |||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.72 (0.45, 1.14) | 0.77 (0.48, 1.23) | 1.39 (0.80, 2.41) | 1.49 (0.84, 2.65) | 1.45 (0.56, 3.78) | 1.46 (0.53, 4.00) | |||

| Physical activityd | 0.67 (0.51, 0.90) | 0.69 (0.51, 0.92) | 0.69 (0.48, 0.98) | 0.65 (0.46, 0.94) | 0.98 (0.57, 1.69) | 1.02 (0.58, 1.79) | |||

| Hypertension | 0.81 (0.47, 1.40) | 0.86 (0.53, 1.39) | 2.01 (0.82, 4.92) | ||||||

| Diabetes | 2.12 1.06, 4.24) | 0.80 (0.44, 1.44) | 1.88 (0.75, 4.76) | ||||||

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 0.60 (0.33, 1.10) | 0.91 (0.49, 1.68) | 0.72 (0.27, 1.90) | ||||||

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.07 (0.85, 1.33) | 1.18 (0.95, 1.46) | 1.02 (0.69, 1.50) | ||||||

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | |||||||||

| ≥90 | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| 60 to <90 | 0.84 (0.50, 1.39) | 0.64 (0.37, 1.09) | |||||||

| 30 to <60 | 1.24 (0.39, 3.96) | 1.11 (0.19, 6.57) | |||||||

| <30 | NA | NA | |||||||

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | |||||||||

| ≥90 | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| 60 to <90 | 0.84 (0.50, 1.39) | 0.64 (0.37, 1.09) | |||||||

| 30 to <60 | 1.24 (0.39, 3.96) | 1.11 (0.19, 6.57) | |||||||

| <30 | NA | NA | |||||||

Abbreviation: NA, not available. Results in bold font represent statistically significant results (P < .05).

Model 1 (demographic variables) included the following: age, sex, center (race stratified models).

Model 2 (demographic + behavioral variables) included the following: model 1 + vitamin D supplementation use, education, BMI, smoking status, current alcohol drinking status, and physical activity.

Model 3 (demographic + behavioral + comorbidities) included the following: model 2 + hypertension, diabetes, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and eGFR (from visit 2 to visit 3 only).

Used data from visit 1 (1986–1990) for visit 2.

In an exploratory analysis (Supplemental Table 3), we examined the association of certain professions with the risk of becoming vitamin D deficient. Compared with those employed, participants who were homemakers or retired were less likely to become vitamin D deficient. Compared with those with managerial and professional occupations (ie, office jobs), those with occupations in service, production, and labor were at a lower risk of becoming vitamin D deficient.

An additional analysis was conducted assessing the odds of vitamin D deficiency among participants with deficiency defined as less than 40 nmol/L (<16 ng/mL) (17). The results were consistent with those using less than 50 nmol/L (<20 ng/mL) as the cutoff for vitamin D deficiency (Supplemental Table 4). We also performed sensitivity analyses excluding participants with very high 25(OH)D levels of 125 nmol/L or greater (≥50 ng/mL) (77 participants, 0.6%), and results remained similar (data not shown).

Discussion

In this large, US community-based sample, 25(OH)D levels within blacks and white participants remained relatively stable over time, with moderate correlation over a 3-year period. Whereas the correlation over 11 years was weaker, it was similar in magnitude to that seen for other CVD-associated risk factors. Furthermore, whereas average 25(OH)D levels slightly increased in black participants between visit 3 and the brain visit, 26% of participants developed incident 25(OH)D deficiency over this time period. Previously, little was known from US data about temporal changes in 25(OH)D level within the same individuals, particularly among black Americans.

Three studies, conducted in Canada (10), The Netherlands (11), and Norway (12) have measured serial 25(OH)D levels and similarly found that vitamin D levels remain relatively stable over time. In the Canadian study, 31% of the participants experienced an increase in 25(OH)D of more than 20 nmol/L and 20% experienced a decrease greater than 20 nmol/L over 10 years of follow-up, resulting in a small average increase in the overall population (<10 nmol/L) (10). Supplement use accounted for 44% of the increase of 25(OH)D levels among women and 25% among men. In the Dutch study, 25(OH)D levels significantly increased by 4 nmol/L over 6 years in participants 55–65 years of age, whereas they decreased by 4 nmol/L over 13 years in those 65–88 years of age (11). In the Norwegian study, average 25(OH)D levels slightly increased over a 14-year period from 61 ± 19 nmol/L to 65 ± 20 nmol/L for samples measured in August but decreased over the same time period from 52 ± 11 nmol/L to 49 ± 19 nmol/L for samples measured in February (12). In that study, the correlation of 25(OH)D over 14 years ranged from r = 0.42–0.52, depending on how seasonal change was accounted for, slightly higher than the correlation coefficient in our study for 25(OH)D levels in blacks over 11 years of follow-up.

In our study, we accounted for seasonal variation between laboratory draws by estimating an annular average of 25(OH)D level for each participant. Of note, participants with 25(OH)D from visit 3 and the brain visit were from Forsyth County, North Carolina, and Jackson, Mississippi, located in a more southern latitude compared with the other two ARIC sites (included in baseline averages at visit 2 but not the longitudinal change analyses). Individuals living in southern latitudes may have less variability in seasonal change compared with northern latitudes, and blacks also have less seasonal variation compared with whites (21).

It is well established that blacks have lower serum concentrations of 25(OH)D than whites (22). Although comparably low 25(OH)D levels in whites or Hispanics are associated with decreased bone mineral density, blacks tend to have higher bone mineral density than would be expected based on their 25(OH)D level (22), suggesting that the effects of vitamin D may vary by race or may be affected by racial differences in bioavailable 25(OH)D levels (23). Prior work on longitudinal changes in vitamin D levels included predominantly white participants residing at northern latitudes (10–12). Our findings extended prior work by demonstrating that longitudinal changes in vitamin D levels among blacks living in southern latitudes were similar to whites (when considering similar time periods).

Several demographic and clinical factors are associated with longitudinal changes in 25(OH)D levels. We found that male sex, vitamin D supplement use, and physical activity were associated with increases in 25(OH)D levels over time, whereas smoking, higher education, diabetes, and hypertension were associated with decreases in 25(OH)D over time. Furthermore, we found that higher BMI was associated with lower 25(OH)D levels over time, which is consistent with multiple other studies showing cross-sectional associations between higher BMI and lower vitamin D levels (24). The association with age varied by race in our study. In whites, older age was associated with decreases in 25(OH)D over time, whereas in blacks, older age was associated with increased levels.

The literature on differences in vitamin D status by sex has been mixed. Some studies have shown that female sex is associated with a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency (25, 26), whereas others have shown no difference by sex (9, 27–29). We found that women were more likely to be taking supplements containing vitamin D compared with men.

We also found that diabetes and hypertension were associated with lower levels of 25(OH)D over time. Diabetes and hypertension are likely markers of a poor health state, with increased prevalence of comorbidities, lower likelihood of outdoor physical activity, and less sun exposure.

Interestingly, although a greater level of education may be expected to be associated with a higher likelihood of supplement use and better overall health, this variable was associated with a higher risk of developing vitamin D deficiency over time in our study. This may be explained by differences in the types of jobs held among more highly educated individuals, who are more likely to have office jobs with limited sunlight exposure, compared with the jobs held by those with less than high school education, who are more likely to have manual and outdoor jobs with greater levels of sunlight exposure. Indeed, our data regarding types of professions and risk of becoming vitamin D deficient supported this difference.

Regarding chronic kidney disease (CKD), there were 30 participants (0.2%) and 247 (1.9%) with eGFR less than 30 and 30–60 mL/min per 1.73/m2, respectively. Changes in 25(OH)D levels over time associated with renal function were mixed. Compared with those with normal renal function (eGFR ≥90 mL/min per 1.73/m2), whites with moderate CKD (eGFR 30–60 and 60–90 mL/min per 1.73/m2) and blacks with eGFR 60–90 mL/min per 1.73/m2 had higher 25(OH)D levels over time, whereas whites with severe CKD (eGFR <30 mL/min per 1.73/m2) had lower levels. Blacks with eGFR 60–90 mL/min per 1.73/m2 also had increasing 25(OH)D levels over time compared with those with normal renal function. These findings were not explained by a higher prevalence of vitamin D supplementation use or lower BMI among the CKD patients. Participants with CKD were more likely to be older and retired or homemakers (P < .001). We found that older participants tended to have higher 25(OH)D levels, and participants who were retired or homemakers were less likely to be vitamin D deficient, which may account for our findings. Renal function was not associated with risk of vitamin D deficiency (<50 nmol/L) over time. Of note, we measured 25(OH)D, which is not the active metabolite (calcitriol) that occurs after renal metabolism. These findings of change in 25(OH)D levels by CKD status should be confirmed in other studies.

Several limitations need to be considered in the interpretation of our findings. We did not have dietary information throughout follow-up, which limited our ability to determine associations of intake from diet and vitamin D status over time. Vitamin D supplement use was also ascertained differently at visit 3 (with a designated vitamin survey) compared with the other visits during which nutritional product information was obtained from a medication use questionnaire. Therefore, differences in recall (if one remembered to mention the vitamin D use on the vitamin survey but not when asked about medication usage) may have influenced the differences in prevalence of supplement usage at these visits. Furthermore, since these data were collected, the proportion of the population taking vitamin D supplements and multivitamins has further increased (30). We also did not have a measure of sunscreen use or a measure of exposure to sunlight, although physical activity can be used as a proxy for sunlight exposure. Finally, there were no whites seen at the brain visit, so our analysis among whites was limited to a 3-year follow-up. However, longitudinal changes in vitamin D level in blacks has not been characterized in the literature, so our analysis of change in vitamin D status among black participants at 3-, 11-, and 14-year intervals is an important contribution to the field.

In conclusion, this descriptive analysis demonstrated that 25(OD) levels remained relatively stable among white and black participants in the ARIC study, a large community-based cohort in the United States. Despite relatively stable levels on average, a sizable proportion of the population became deficient in 25(OH)D over time. Reductions in 25(OH)D levels over time were associated with certain demographic and behavioral factors, which may help identify subjects at high risk of vitamin D deficiency.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (Grant R01NS072243 to E.D.M.), the NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (Grant R01HL103706 to P.L.L.), the NIH Office of Dietary Supplements (Grant R01HL103706-S1 to P.L.L.), and the NIH/NHLBI (Grant R01HL70825 to T.H.M.). A.L.C.S. was supported by NIH/NHLBI Training Grant T32HL007024. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts (Grants HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ARIC

- Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

- BMI

- body mass index

- CI

- confidence interval

- CKD

- chronic kidney disease

- CVD

- cardiovascular disease

- eGFR

- estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HDL

- high-density lipoprotein

- IOM

- Institute of Medicine

- MRI

- magnetic resonance imaging

- 25(OH)D

- 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

References

- 1. Wang L, Song Y, Manson JE, et al. Circulating 25-hydroxy-vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(6):819–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Forman JP, Giovannucci E, Holmes MD, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of incident hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49(5):1063–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mattila C, Knekt P, Mannisto S, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(10):2569–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Melamed ML, Michos ED, Post W, Astor B. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D levels and the risk of mortality in the general population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(15):1629–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dobnig H, Pilz S, Scharnagl H, et al. Independent association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(12):1340–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shoben AB, Kestenbaum B, Levin G, et al. Seasonal variation in 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in the cardiovascular health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(12):1363–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Woitge HW, Scheidt-Nave C, Kissling C, et al. Seasonal variation of biochemical indexes of bone turnover: results of a population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(1):68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Looker AC, Pfeiffer CM, Lacher DA, Schleicher RL, Picciano MF, Yetley EA. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status of the US population: 1988–1994 compared with 2000–2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(6):1519–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ginde AA, Liu MC, Camargo CA., Jr Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988–2004. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(6):626–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berger C, Greene-Finestone LS, Langsetmo L, et al. Temporal trends and determinants of longitudinal change in 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone levels. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(6):1381–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Schoor NM, Knol DL, Deeg DJ, Peters FP, Heijboer AC, Lips P. Longitudinal changes and seasonal variations in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in different age groups: results of the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(5):1483–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jorde R, Sneve M, Hutchinson M, Emaus N, Figenschau Y, Grimnes G. Tracking of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels during 14 years in a population-based study and during 12 months in an intervention study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(8):903–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mosley TH, Jr, Knopman DS, Catellier DJ, et al. Cerebral MRI findings and cognitive functioning: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Neurology. 2005;64(12):2056–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lutsey PL, Eckfeldt JH, Ogagarue ER, Folsom AR, Michos ED, Gross M. The 25-hydroxyvitamin D C-3 epimer: distribution, correlates, and reclassification of 25-hydroxyvitamin D status in the population-based Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC). Clin Chim Acta. 2015;442:75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sachs MC, Shoben A, Levin GP, et al. Estimating mean annual 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations from single measurements: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(6):1243–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36(5):936–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):20–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Michos ED, Carson KA, Schneider AL, et al. Vitamin D and subclinical cerebrovascular disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities brain magnetic resonance imaging study. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(7):863–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gutierrez OM, Farwell WR, Kermah D, Taylor EN. Racial differences in the relationship between vitamin D, bone mineral density, and parathyroid hormone in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(6):1745–1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Powe CE, Evans MK, Wenger J, et al. Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D status of black Americans and white Americans. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(21):1991–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Samuel L, Borrell LN. The effect of body mass index on optimal vitamin D status in US adults: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2006. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23(7):409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vu LH, Whiteman DC, van der Pols JC, Kimlin MG, Neale RE. Serum vitamin D levels in office workers in a subtropical climate. Photochem Photobiol. 2011;87(3):714–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Erkal MZ, Wilde J, Bilgin Y, et al. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, secondary hyperparathyroidism and generalized bone pain in Turkish immigrants in Germany: identification of risk factors. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(8):1133–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cinar N, Harmanci A, Yildiz BO, Bayraktar M. Vitamin D status and seasonal changes in plasma concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in office workers in Ankara, Turkey. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(2):197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rudnicki M, Thode J, Jorgensen T, Heitmann BL, Sorensen OH. Effects of age, sex, season and diet on serum ionized calcium, parathyroid hormone and vitamin D in a random population. J Intern Med. 1993;234(2):195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pal BR, Marshall T, James C, Shaw NJ. Distribution analysis of vitamin D highlights differences in population subgroups: preliminary observations from a pilot study in UK adults. J Endocrinol. 2003;179(1):119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dickinson A, Blatman J, El-Dash N, Franco JC. Consumer usage and reasons for using dietary supplements: report of a series of surveys. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33(2):176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]