Abstract

The synthetic progestin, 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate, is increasingly used for the prevention of premature birth in at-risk women, despite little understanding of the potential effects on the developing brain. Rodent models suggest that many regions of the developing brain are sensitive to progestins, including the mesocortical dopamine pathway, a neural circuit important for complex cognitive behaviors later in life. Nuclear progesterone receptor is expressed during perinatal development in dopaminergic cells of the ventral tegmental area that project to the medial prefrontal cortex. Progesterone receptor is also expressed in the subplate and in pyramidal cell layers II/III of medial prefrontal cortex during periods of dopaminergic synaptogenesis. In the present study, exposure to 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate during development of the mesocortical dopamine pathway in rats altered dopaminergic innervation of the prelimbic prefrontal cortex and impaired cognitive flexibility with increased perseveration later in life, perhaps to a greater extent in males. These studies provide evidence for developmental neurobehavioral effects of a drug in widespread clinical use and highlight the need for a reevaluation of the benefits and potential outcomes of prophylactic progestin administration for the prevention of premature delivery.

Receiving Food and Drug Administration approval in 2011, the administration of the synthetic progestin, 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17-OHPC), to women considered at risk for premature delivery is increasing dramatically (1, 2), despite little information regarding the potential effects on fetal development. 17-OHPC is prescribed during the late second and early third trimesters and can be detected in maternal and fetal plasma more than a month after the last injection (3), suggesting that fetuses may be exposed to 17-OHPC during critical periods of cortical development, particularly during the maturation of the mesocortical dopamine pathway (4, 5), a neural circuit important for executive function.

In rats, the mesocortical dopamine pathway is sensitive to progestins during development. Nuclear progesterone receptor (PR) is transiently expressed in dopaminergic cells of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) during perinatal development including VTA cells that project to the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (6). PR is also expressed in cells of the subplate and in pyramidal cell layers II/III of the mPFC (6–8) during the arrival of dopaminergic axons from VTA and during subsequent synaptogenesis (9). Steroid receptors, as powerful transcription factors, can alter fundamental processes of neural development and pharmacological inhibition of PR during development impairs the performance on mPFC-mediated tasks in adulthood (6). Therefore, in light of the notable rise in the number of children potentially exposed to 17-OHPC in utero, the present experiments used a rodent model to examine the effects of 17-OHPC administration during development on cognitive flexibility in adulthood and on dopaminergic innervation of the mPFC in preadolescence, a period of synaptic development for the prefrontal cortex. Cognitive flexibility, the ability to change strategy in light of shifting environmental contingencies, is highly dependent on dopaminergic activity in the mPFC (10–12), notably within the prelimbic (PL) mPFC (13, 14).

Materials and Methods

Animals and treatment

Pregnant Sprague Dawley rats, purchased from Taconic Laboratories, were allowed to deliver normally, and the day of birth was designated as postnatal day (P) 1. Animals were housed on a reverse 12-hour light, 12-hour dark cycle at a constant temperature of 25°C ± 2°C, with food and water available ad libitum unless otherwise specified. Male and female pups were injected daily with 17-OHPC (MP Biomedicals) (0.5 mg/kg in sesame oil, sc; ie, the per kilogram equivalent to the dose used in women) or an equal volume of the oil vehicle alone from P1 through P14, representing the period of PR expression in the VTA and prefrontal cortex. After weaning at P21, all animals were housed in pairs or triplets with same-sex littermates. One cohort of animals (n = 31) was used for behavioral testing at P90 (experiment 1). Brain tissue from a separate cohort of males and females (n = 20) was collected at P25 for immunocytochemical analysis (experiment 2). For both experiments, the treatment groups were counterbalanced within litters, such that each litter contained vehicle and 17-OHPC male and female rats. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University at Albany.

Experiment 1

Male and female rats treated from P1 to P14 with 17-OHPC or vehicle were behaviorally tested as young adults. Cognitive flexibility was assessed using the attentional set-shift task. Beginning at P87, food was restricted to 15 g/d prior to and during testing, and animals were maintained at 80%–90% of free-feeding weight to ensure motivation for a food reward. There was no effect of treatment on baseline body weight or changes in weight in response to food restriction (data not shown). The testing apparatus is a four-armed maze, in which the arms of the maze are painted either white or black and the floors have either a rough or smooth texture (Figure 1). All habituation, pretesting, and testing procedures were identical with those described by Stefani and Moghaddam in 2006 (10) and are briefly described in Figure 1. Group differences in the number of trials to criterion in set 1 were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. A two-way, repeated-measures ANOVA (treatment × trial block) was used to analyze the percentage correct across set 2. Preliminary analysis showed that in the control animals, there was a significant improvement in performance between the first (trial blocks 1–5) and second (trial blocks 6–10) halves of set 2 (ie, a shift to the new rule). This was true for both male (F[1,39] = 64.313, P < .001) and female (F[1,29] = 174.677, P < .001) controls. As a result, separate two-way, repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted for the first half (trial blocks 1–5) and the second half (trial blocks 6–10). Repeated-measures ANOVAs (set 2 half × treatment) were used to compare the number of perseveration and omission errors between groups on set 2.

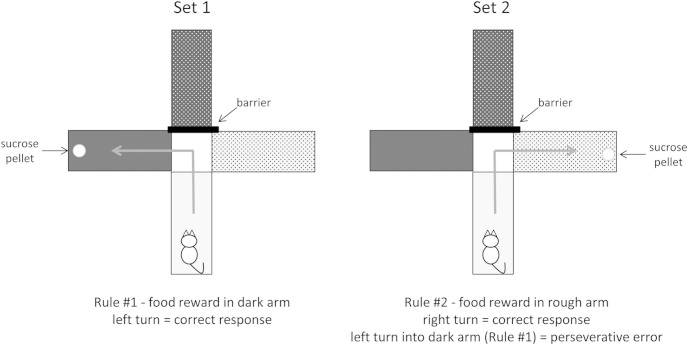

Figure 1.

Set shift task procedure. Habituation trials were conducted for 3 days prior to testing in which all arms were baited with a food reward. Set 1, Rats were trained to a criterion of eight consecutive correct trials in which one arm was barricaded and another arm was baited in a forced-choice paradigm. Barricaded and start arms were counterbalanced and the maze was rotated to eliminate use of spatial cues. Rats were placed into the start arm and were trained to learn a rule (ie, an association between a specific maze arm dimension [ie, color: light/dark or texture: rough/smooth] and the food reward [eg, food reward in light arms]). Set 2, Twenty-four hours after set 1, rats underwent 80 trials (10 trials per trial block), regardless of performance, in which a new rule using a different sensory domain was imposed (eg, food reward switched from light arm to rough arm). This extradimensional shift (from one sensory domain to another) is dependent on dopaminergic activity in the mPFC (10, 12). Again, the maze was rotated and start arms were counterbalanced across trials. Entry into an arm using the new rule was a correct trial. Entry into an arm using the rule from set 1 was considered a perseveration error. Entry into an arm that uses neither the new rule nor the old rule was considered an omission error.

Experiment 2

Cognitive flexibility is dependent on dopaminergic activity in the prefrontal cortex (10, 12), with the prelimbic mPFC being particularly important (12–15). Therefore, we examined the effects of neonatal 17-OHPC treatment on the density of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive (THir) fibers in the mPFC during preadolescence at P25. Tissue collection and immunocytochemical procedures were identical with those described previously (6), using a primary antisera against TH (1:1000: rabbit polyclonal; Millipore). Analysis of THir fiber density in the mPFC was determined as described using previously established methods (12, 15). Briefly, representative, anatomically matched sections containing the PL mPFC and the anterior cingulate (AC; as a control region) were used to capture photographs under dark-field illumination. Pictures were acquired using a model 1.3.0 SPOT digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments Inc) attached to a Nikon E600 microscope using a ×20 objective, and analysis was performed using Scion Image Software (Scion Corp). Relative density of THir fibers was assessed by measuring the area (square micrometers) covered by thresholded pixels (ie, those pixels with higher immunoreactive intensity than a defined threshold density [specific immunoreactive staining]). Separate photographs were acquired from layers I–II and from layers V–VI (see Figure 4, A and B). Separation of these layers is made identifiable based on THir fiber orientation (9, 12, 15). The PL mPFC was identified based on proximity to the forceps minor corpus callosum, easily identifiable by its white matter composition. Statistical analyses were performed for both regions using a two-way ANOVA (sex × treatment), followed by preplanned, post hoc comparisons using a Student-Newman-Keuls test (P < .05).

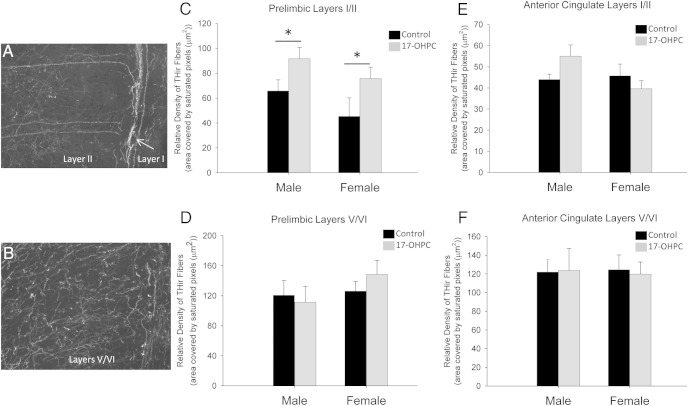

Figure 4.

17-OHPC exposure during development increased dopaminergic innervation in the prelimbic mPFC in preadolescence. Digital photomicrographs (×20 magnification) depicting PL mPFC layers I/II (A) and V/VI (B) are shown. The relative density of THir fibers in layers I/II (C and E) and layers V/VI (D and F) of the PL mPFC (C and D) or AC (E and F) in P25 males and females treated neonatally with either 17-OHPC or the vehicle control. *, Significantly different from control (P < .05). There were no significant effects of treatment in layers V/VI of the PL mPFC and no significant effects in either layer of the AC.

Results

17-OHPC during development impaired cognitive flexibility with increased perseveration in adulthood

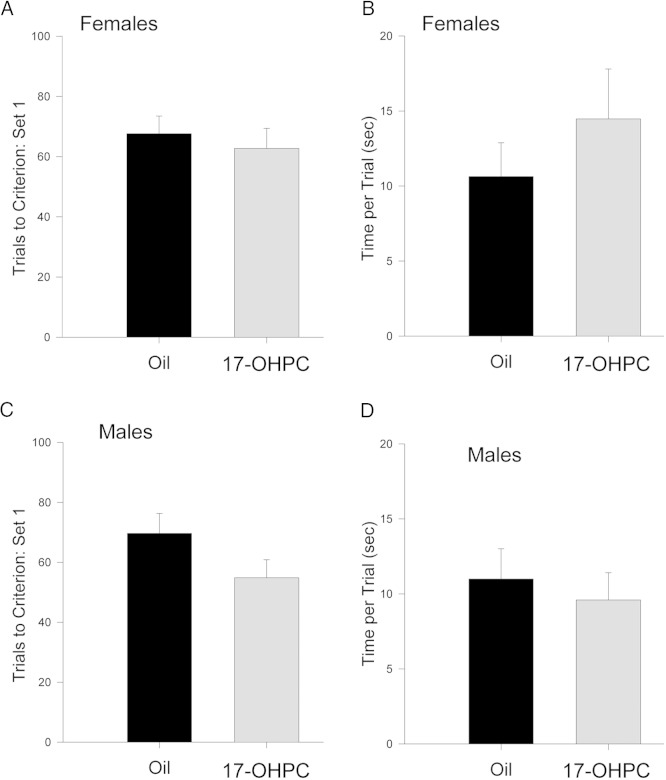

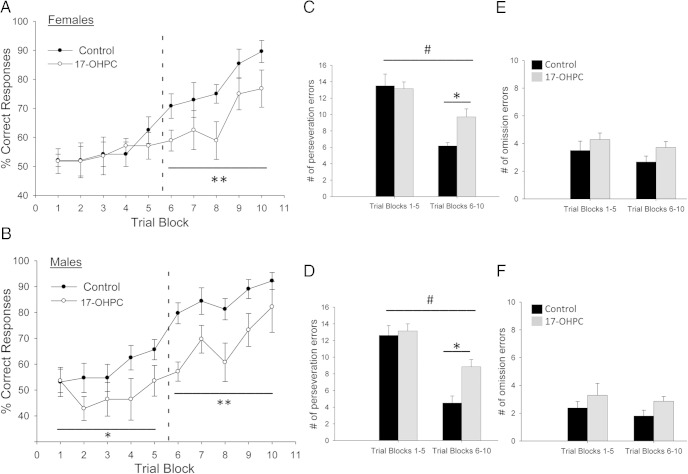

In set 1, there was no significant effect of 17-OHPC on the number of trials to criterion in set 1 or the mean time required per trial in either males or females (Figure 2), indicating no impairment in associative learning. In set 2, trial blocks 6–10, there was a significant main effect of 17-OHPC treatment on the percentage correct responses for both males and females (females [F(1,64) = 13.237, P < .005]; males [F(1,74) = 15.933, P < .005]) (Figure 3, A and B). By trial block 6, control males and females began to acquire the new rule (ie, make the shift; see Materials and Methods), reaching almost 90% correct responses by trial block 10. In contrast, 17-OHPC-treated males and females were slower to make the shift to the new rule (approximately trial block 9), never performing as well as controls (Figure 3, A and B). Interestingly, there was a significant main effect of 17-OHPC in the initial response to the rule change (ie, trial blocks 1–5) in males (F[1,74] = 6.259, P < .05) but not in females, suggesting that sex differences in the effects of 17-OHPC exposure may exist.

Figure 2.

17-OHPC exposure during development did not affect learning of the initial rule in set 1 in adulthood. A and C, The number of trials required to reach criterion (ie, eight consecutive correct trials). B and D, The mean time required to complete each trial in set 1 of the set shift task in females (A and B) and males (C and D) treated neonatally with either 17-OHPC or the vehicle control. There were no significant effects of 17-OHPC treatment on either measure.

Figure 3.

17-OHPC exposure during development impaired cognitive flexibility and increased perseveration in adulthood. The percentage correct responses per trial block (each block is eight trials) in set 2 in females (A) and males (B) treated neonatally with either 17-OHPC or the vehicle control are shown. Dashed line indicates the point at which the shift to the new rule occurs in controls (see Materials and Methods). The number of perseveration errors (C and D) and omission errors (E and F) in set 2 for trial blocks 1–5 and trial blocks 6–10 in females and males treated neonatally with either 17-OHPC or the vehicle control is shown. *, Significant difference between control and 17-OHPC treated (P < .05); #, Significant difference between trial blocks 1–5 and 6–10 (P < .001). There were no significant effects of treatment or trial blocks on omission errors.*, Significantly different from control; *, P < .05) **, P < .01.

17-OHPC treatment significantly increased the number of perseverative errors (errors attributable to responses based on the set 1 contingency) (Figure 3, C and D) but had no effect on the number of omission errors (incorrect responses for either set 1 or set 2 contingencies) (Figure 3, E and F). For perseveration errors, there was a significant interaction between treatment and trial blocks (females [F(1,28) = 7.033, P < .05]; males [F(1,29) = 7.922, P < .05]) and a significant main effect of trial blocks (females [F(1,28) = 53.422, P < .001]; males [F(1,29) = 82.781, P < .001]) (Figure 3, C and D). For omission errors, there was no significant main effect of 17-OHPC treatment or trial block (Figure 3, E and F).

17-OHPC during development increased dopaminergic innervation of prelimbic mPFC in preadolescence

17-OHPC treatment significantly increased THir fiber density in layers I/II (ie, the location of layer III pyramidal cell apical dendrites) of the prelimbic mPFC. There was a significant main effect of treatment for layers I/II (F[1,19] = 6.721, P < .05) but no significant effect of sex (Figure 4C). There was no effect of treatment in V/VI of the prelimbic mPFC (Figure 4D) or in any layer of the anterior cingulate cortex (Figure 4, E and F).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the results from this study provide the first documentation of long-term consequences of 17-OHPC exposure during development on cognitive behavior and offer more insight into the potential role of progestins in neural development. 17-OHPC administration during a period of mesocortical dopamine pathway development in rats increased dopaminergic innervation of specific lamina of prelimbic mPFC in juveniles, consistent with the possibility of impaired synaptic pruning. Additionally, 17-OHPC exposure impaired cognitive flexibility in adulthood. 17-OHPC-treated rats were slower to make a cognitive switch to a new rule and continued to perseverate on the old rule longer than controls. Taken together, these findings are consistent with previous reports indicating that increases in dopaminergic activity in the prefrontal cortex above baseline produce deficits in cognitive flexibility in rats (15, 16). Because the PR is expressed in dopaminergic VTA neurons and in mPFC pyramidal cells during development (6), it is likely that 17-OHPC exerted its effects by altering PR activity in these regions during critical periods of connectivity and synaptogenesis. Abnormal levels of PR activity and/or PR activity at improper times during this critical period of connectivity may significantly alter the development of important behavioral neural circuits.

In humans, 17-OHPC can be transferred from maternal to fetal circuits of the human placenta (17), and fetuses may be exposed to 17-OHPC well past the last treatment and longer than originally thought (2). The present findings reporting neurocognitive effects reminiscent of those often associated with developmental disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism (18–20) should highlight the need for additional research on the potential effects in children and contribute to the assessment of the benefits vs the potential risks of synthetic progestin administration in pregnant women.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant IOS1050367 and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD07643001 (to C.K.W.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AC

- anterior cingulate

- mPFC

- medial prefrontal cortex

- 17-OHPC

- 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate

- P

- postnatal day

- PL

- prelimbic

- PR

- progesterone receptor

- THir

- tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive

- VTA

- ventral tegmental area.

References

- 1. Di Renzo GC, Giardina I, Clerici G, Mattei A, Alajmi AH, Gerli S. The role of progesterone in maternal and fetal medicine. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28:925–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saccone G, Suhag A, Berghella V. 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for maintenance tocolysis: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Caritis SN, Sharma S, Venkataramanan R, et al. Pharmacology and placental transport of 17-hydroxyprogesterone caproate in singleton gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:398.e1–398.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Verney C, Milosevic A, Alvarez C, Berger B. Immunocytochemical evidence of well-developed dopaminergic and noradrenergic innervations in the frontal cerebral cortex of human fetuses at midgestation. J Comp Neurol. 1993;336:331–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zecevic N, Verney C. Development of the catecholamine neurons in human embryos and fetuses, with special emphasis on the innervation of the cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1995;351:509–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Willing J, Wagner CK. Progesterone receptor expression in the developing mesocortical dopamine pathway: importance for complex cognitive behavior in adulthood. Neuroendocrinology. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lopez V, Wagner CK. Progestin receptor is transiently expressed perinatally in neurons of the rat isocortex. J Comp Neurol. 2009;512:124–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jahagirdar V, Wagner CK. Ontogeny of progesterone receptor expression in the subplate of fetal and neonatal rat cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:1046–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kalsbeek A, Voorn P, Buijs RM, Pool CW, Uylings HB. Development of the dopaminergic innervation in the prefrontal cortex of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1988;269:58–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stefani MR, Moghaddam B. Rule learning and reward contingency are associated with dissociable patterns of dopamine activation in the rat prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and dorsal striatum. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8810–8818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rich EL, Shapiro M. Rat prefrontal neurons selectively code strategy switches. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7208–7219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Naneix F, Marchand AR, Di Scala G, Pape JR, Coutureau E. A role for medial prefrontal dopaminergic innervation in instrumental conditioning. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6599–6606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ragozzino ME, Detrick S, Kesner RP. Involvement of the prelimbic-infralimbic areas of the rodent prefrontal cortex in behavioral flexibility for place and response learning. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4585–4594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ragozzino ME, Kim J, Hassert D, Minniti N, Kiang C. The contribution of the rat prelimbic-infralimbic areas to different forms of task switching. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:1054–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kritzer MF, Brewer A, Montalmant F, Davenport M, Robinson JK. Effects of gonadectomy on performance in operant tasks measuring prefrontal cortical function in adult male rats. Horm Behav. 2007;51:183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gruber AJ, Calhoon GG, Shusterman I, Schoenbaum G, Roesch MR, O'Donnell P. More is less: a disinhibited prefrontal cortex impairs cognitive flexibility. J Neurosci. 2010;30:17102–17110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hemauer SJ, Yan R, Patrikeeva SL, et al. Transplacental transfer and metabolism of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:169.e1–169.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arnsten AF, Li BM. Neurobiology of executive functions: catecholamine influences on prefrontal cortical functions. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1377–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brennan AR, Arnsten AF. Neuronal mechanisms underlying attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: the influence of arousal on prefrontal cortical function. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1129:236–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Prince J. Catecholamine dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an update. J Clin Psychopharm. 2008;28:s39–s45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]