Abstract

Exposure of humans to bisphenol A (BPA) is widespread and continuous. The effects of protracted exposure to BPA on the adult prostate have not been studied. We subjected Noble rats to 32 weeks of BPA (low or high dose) or 17β-estradiol (E2) in conjunction with T replenishment. T treatment alone or untreated groups were used as controls. Circulating T levels were maintained within the physiological range in all treatment groups, whereas the levels of free BPA were elevated in the groups treated with T+low BPA (1.06 ± 0.05 ng/mL, P < .05) and T+high BPA (10.37 ± 0.43 ng/mL, P < .01) when compared with those in both controls (0.1 ± 0.05 ng/mL). Prostatic hyperplasia, low-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), and marked infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells into the PIN epithelium (P < .05) were observed in the lateral prostates (LPs) of T+low/high BPA-treated rats. In contrast, only hyperplasia and high-grade PIN, but no aberrant immune responses, were found in the T+E2-treated LPs. Genome-wide transcriptome analysis in LPs identified differential changes between T+BPA vs T+E2 treatment. Expression of multiple genes in the regulatory network controlled by hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α was perturbed by the T+BPA but not by the T+E2 exposure. Collectively these findings suggest that the adult rat prostate, under a physiologically relevant T environment, is susceptible to BPA-induced transcriptomic reprogramming, immune disruption, and aberrant growth dysregulation in a manner distinct from those caused by E2. They are more relevant to our recent report of higher urinary levels BPA found in patients with prostate cancer than those with benign disease.

Bisphenol A (BPA), a ubiquitous endocrine disruptor and a synthetic estrogen (1), is used primarily in the fabrication of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins, with an estimated global capacity of production exceeding 8 billion pounds per year (2). Biomonitoring studies of human urine, blood, and tissue samples indicate widespread and continuous exposure to BPA in the US population (3–5). In the 1980s, the National Toxicology Program (NTP) did not consider BPA a carcinogen (6). However, the controversy as to whether BPA causes adverse health effects in humans has been ongoing during the last 3 decades (7). In 2008, the NTP reported “negligible concern for reproductive effects in nonoccupationally exposed adults” but identified “some concern for BPA exposure in fetuses, infants, and children at current human exposures.” Therefore, the Food and Drug Administration recently banned the use of BPA in baby bottles and cups and for the packaging of infant formula. The adverse effects of BPA may stem from its estrogenic properties. BPA elicits biological responses via estrogen receptor-α, estrogen receptor-β, or G protein-coupled estrogen receptor through genomic and/or rapid nongenomic signaling pathways (8–11). The potential risk to adult men due to chronic, continuous environmental exposure to BPA remains largely unclarified.

Compelling evidence from our laboratory and others has linked developmental BPA exposure to predisposition to prostate cancer (PCa) (12–14). Recently we correlated urinary levels of BPA to human PCa and demonstrated that low-dose BPA promoted centrosome amplification and anchorage-independent growth in PCa cells (15). In addition to carcinogenicity, BPA exposure has been linked to enhanced prostate growth and inflammatory responses. When BPA was given at low doses in utero, it stimulated prostate duct growth in fetal prostates (16) and increased the prostate weight of the offspring when assessed during adulthood (17). However, other studies failed to replicate such low-dose effects (18, 19). Prepubertal BPA exposure for 10 days induced inflammation in the adult prostate (20), whereas adult BPA exposure for 4 weeks aggravated preexisting benign prostate hyperplasia (21). Nonetheless, a gap in knowledge exists as to whether chronic exposure to low-dose BPA through a long period of adult life could induce aberrant prostate pathologies. Furthermore, the question concerning whether the effects of exposure to BPA mimic those elicited by the natural estrogen, 17β-estradiol (E2), needs to be addressed.

This study examined the effects of protracted exposure of adult animals to low-dose BPA on prostate pathohistological and transcriptomic changes using the hormone-induced PCa Noble (NBL) rat model (22–26). We have previously established that NBL rats are uniquely sensitive to estrogen-induced neoplastic transformation (23, 24, 26) and have recently compared the transcriptional responses of the rat's dorsolateral prostate with E2 and the xenoestrogen diethylstilbestrol using microarray analyses (27, 28). In the present study, we chronically elevated circulating levels of free (bioactive) BPA in adult NBL rats to relevant levels (1–10 ng/mL) in humans (3, 4) while maintaining physiological levels of T, which have been reported to be reduced by BPA treatment alone (29). We hypothesize that such treatment is effective in inducing hyperplasia, inflammation and/or premalignant lesions in the rat prostate that is accompanied by BPA-associated gene expression changes. The study design also compares the effects of BPA with those of E2 in the T-supported environment.

Materials and Methods

Animals and hormone treatment

Protocols of animal usage were approved by the University of Cincinnati Medical School Animal Care and Usage Committee. All animal experimentation in this study was conducted in accordance with accepted standards of humane animal care, as outlined in the ethical guidelines. NBL rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories and kept under standard conditions. Rats were fed the AIN-76A diet (TestDiet). Water was available via an automatic water system (no plastic water bottles). In brief, adult NBL rats (16 wk of age) were randomized into five treatment groups (n = 3 or 4): control, T+E2, T+low-dose BPA (T+low BPA), T+high-dose BPA (T+high BPA), and T alone (T). Control rats were surgically implanted with empty capsules sc. T+E2-treated rats were implanted with SILASTIC brand capsules (Dow Corning) containing 30 mg of T and 15 mg of E2 as reported previously (28, 30). The combined treatment with T and E2 used in the current study has been well established as maintaining the serum T levels at physiological levels while elevating serum E2 levels 4- to 5-fold (30). Rats treated with T+low BPA received T- and BPA-filled capsules containing 30 mg of T and 15 mg of BPA, respectively. Rats treated with T+high BPA received the same amount of T but 320 mg of BPA. Rats treated with T alone received T capsules containing 30 mg of T. Supplemental Table 1 gives the detailed specification of SILASTIC brand capsules and the dosage of hormone/BPA in each treatment group. New hormone capsules were administered every 8 weeks. At the end of a 32-week treatment period, animals were killed by administering an overdose of isoflurane, and lateral (LP), ventral (VP), dorsal (DP), and anterior (AP) prostate lobes were excised. Half of each lobe was processed for histological examination, and the other half was snap frozen for RNA extraction.

Histopathology

Formalin-fixed samples were processed for hematoxylin/eosin staining and scored for prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) lesions in a blinded manner, as previously described (12, 13, 28, 30). The incidence and mean PIN scores per treatment group were determined and analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Mann-Whitney U test in the post hoc analysis. P < .01 was used to determine the significance for comparing treatment means.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining of Ki-67 (NCL-Ki67-MM1, 1:100; Novocastra Laboratories), CD8a (number 554854, 1:50; BD Biosciences), and CD4 (CL003AP, 1:500; Cedarlane Labs) was conducted as previously described (28, 31) (Table 3). The Ki-67 index of epithelial cells was determined, as previously described (28). The quantitation of epithelium-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was conducted by manual cell counting as previously described (32). The number of positively and negatively stained cells were determined in three to five noncontiguous ×40 fields of normal or PIN epithelium across treatment groups. Values were expressed as cell count index, ie, number of CD4+/CD8+ T-cells divided by the total number of cells within a specific epithelial region times 100%.

Table 3.

Antibody Table

| Peptide/Protein Target | Antigen Sequence (if Known) | Name of Antibody | Manufacturer, Catalog Number, and/or Name of Individual Providing the Antibody | Species Raised (Monoclonal or Polyclonal) | Dilution Used | DOI or Publication Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki67 antigen | Ki67 antibody | Leica Biosystems, NCL-Ki67-MM1 | Mouse monoclonal | 1:100 | DOI: 10.1210/me.2010-0179 | |

| CD8a | CD8a antibody | BD Biosciences, 554854 | Mouse monoclonal | 1:50 | DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/en.2002-0038 | |

| CD4 | CD4 antibody | Cedarlane Labs, CL003AP | Mouse monoclonal | 1:500 | DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/en.2002-0038 |

Measurement of BPA in sera

BPA levels in samples were determined in the Laboratory of Organic Analytical Chemistry of Wadsworth Center (New York State Department of Health, Albany, New York). HPLC coupled with electrospray triple-quadrupole mass spectrometry was used to quantify BPA, a technique similar to that described earlier, with minor modifications (13, 33). In brief, serum from each animal was split into two aliquots, and 5 ng of deuterated-bisphenol A (d16-BPA) was added as an internal standard. One aliquot was used for measurement of freely available BPA (active), and the other was used for analysis of total BPA (free plus glucuronidated-BPA, the main bound form of BPA [inactive]). Analyte separation and detection were carried out using an Agilent 1100 series HPLC interfaced with an Applied Biosystems API 2000 electrospray MS/MS (Applied Biosystems). Quality-assurance and quality-control parameters included validation of the method by spiking deuterated BPA into the sample matrices and passing through the entire analytical procedure to calculate recoveries of BPA. The limit of detection was 0.05 ng/mL. Quantification was based on an external calibration curve prepared by injecting 10 mL of 0.02-, 0.05-, 0.1-, 0.2-, 0.5-, 1, 5-, 10-, and 50-ng/mL standards.

RIA of serum T

Total T levels in serum were measured by RIA, which was conducted in the Ligand Assay and Analysis Core, Center for Research in Reproduction at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia). The RIA kit for the T assay was provided by Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics. The sensitivity of the T assays is 10 ng/dL. The reportable range of the assay was 10–1000 ng/dL.

Microarray experiment and data analysis

Total RNA was isolated from LPs using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA with an RNA integrity number greater than 9 (Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer; Agilent) was used for the microarray analysis. Microarrays were performed according to a previously published protocol (28). In brief, 15 μg of fragmented amplified RNA was hybridized to Rat Gene 1.0 ST array (Affymetrix), and signals were scanned with the Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G with GCOS software. After array quality was assessed using the Quality Metrics package of Bioconductor (34), data were analyzed using software R and the limma package (35) of Bioconductor with custom Computable Document Format downloaded from BrainArray (36). Data preprocessing, including background correction and normalization, was performed using Robust Multiarray Average. Primary and processed microarray data are accessible through the Gene Expression Omnibus database under the accession identifier GSE66633. Genes differentially expressed in T+E2, T+low BPA, or T+high BPA treatments vs control (one way ANOVA, P < .01) were subjected to a two-way hierarchical gene clustering. In the heat map, genes present in an individual block of clusters were further tested by a one-way ANOVA to identify differentially expressed genes specific to a certain treatment (eg, T+low BPA; P < .01 vs control, fold change > 1.2). For biological function analyses, genes identified as differentially expressed compared with the control-treated LP were imported into the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (IPA; version 7.5, www.ingenuity.com, Ingenuity Systems), and networks were generated on the basis of the Ingenuity Knowledge Base. Genes directly or indirectly connected in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base were displayed as networks.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was reverse transcribed, and real-time qPCR was carried out as previously described (37, 38). Primer sequences are presented in Supplemental Table 2. PCRs were performed with SYBR GreenER PCR master mix (Invitrogen) and monitored with the 7900HT Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Individual mRNA levels were normalized to ribosomal protein L19 (Rpl19), a housekeeping gene whose transcript level is not altered by E2, BPA, or T treatment (12, 27, 28, 30) and expressed relative to the untreated control LP levels.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean SEM. Statistical analysis included an ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison tests unless stated otherwise. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Subcutaneous implantation of SILASTIC brand capsules containing BPA elevated serum BPA levels

The levels of T, free BPA, and total BPA (free and glucuronidated) in the serum after 32 weeks of sc implantation of T-, E2-, and/or BPA-filled SILASTIC brand capsules (Dow Corning) are shown in Table 1. Implantation of T-filled capsules (30 mg/rat) maintained the serum T at physiological levels in all treated groups (P > .05 vs the untreated control group). Implants filled with T+low BPA (15 mg BPA/rat) increased the concentrations of free BPA 10-fold (1.06 ± 0.05 ng/mL, P < .05) as compared with levels in the untreated control rats (0.1 ± 0.05 ng/mL). In the T+high BPA (320 mg BPA/rat) group, free BPA levels (10.37 ± 0.43 ng/mL) were approximately 100-fold higher than those in the untreated controls. Serum concentrations of total BPA were also increased in the T+low BPA group (229-fold, P < .05) and T+high BPA group (937-fold, P < .05). In the T+low BPA group, 4.6% of total BPA was in the free bioavailable form. The percentage of free BPA was increased to 11% in the T+high BPA group. The levels of free and total BPA in the untreated control rats were low (0.1–0.05 ng/mL), levels that were close to the detection limit (0.05 ng/mL). The BPA levels in the T+E2 group were below the detection limit of the BPA assay.

Table 1.

Serum T and Free and Total BPA Levels

| Treatment | T, ng/mL | Free BPA, ng/mL | Total BPA, ng/mL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.21 ± 0.38 | 0.1 ± 0.05 | 0.1 ± 0.05 |

| T+E2 | 1.91 ± 0.37 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| T+low BPA | 2.32 ± 0.28 | 1.06 ± 0.05a | 22.93 ± 4.02a |

| T+high BPA | 2.54 ± 0.43 | 10.37 ± 0.43a,b | 93.7 ± 4.7a,b |

| T | 1.17 ± 0.18 | ND | ND |

Abbreviation: ND, not determined. BPA detection limit is 0.05 ng/mL; T detection limit is 10 ng/dL. Values represent mean ± SEM.

P < .05 vs control or T+E2.

P < .05 vs T+low BPA.

Cotreatment with T and BPA increased prostate weights

At the end of 32 weeks of treatment, the mean body weight of T+E2-treated rats was significantly decreased as compared with that of untreated controls (P < .05, Table 2). However, T+low BPA, T+high BPA, or T did not result in significant changes in the body weight (P > .05, Table 2). For prostate lobes, T+E2 increased the relative weight of LPs and APs (P < .05, Table 2). In the T+low BPA and T+high BPA groups, the relative weight of VPs, LPs, DPs, and APs were significantly increased as compared with those of untreated controls (P < .05, Table 2). There were significant increases of the relative weights of VPs, DPs, and APs in the T+low/high BPA groups when compared with the T+E2 and the T groups. T treatment alone did not significantly increase the relative prostate weights.

Table 2.

Effects of Chronic Exposure to T+E2/BPA or T Alone on Body Weight and Prostate Weight

| Treatment | Body Weight, g | Relative Prostate Weight, mg per 100 g Body Weight |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VP | LP | DP | AP | ||

| Control | 410 ± 16.63 | 51.79 ± 3.02 | 32.09 ± 2.72 | 24.6 ± 1.73 | 16.45 ± 1.99 |

| T+E2 | 303 ± 15.92a | 69.21 ± 1.82 | 64.15 ± 7.26a | 38.13 ± 2.49 | 37.52 ± 4.5a |

| T+low BPA | 369.3 ± 15.07 | 132.1 ± 33.36a,b | 112.2 ± 27.02a,c | 90.82 ± 26.12a,b,c | 93.01 ± 24.5a,b,c |

| T+high BPA | 417.3 ± 13.48b | 143.0 ± 6.89a,b,c | 110.2 ± 4.76a,c | 90.24 ± 7.7a,b,c | 98.86 ± 5.33a,b,c |

| T | 408.5 ± 10.87b | 71.66 ± 9.89 | 50.77 ± 4.57 | 40 ± 4.69 | 33.29 ± 3.2 |

Values represents mean ± SEM.

P < .05 vs control.

P < .05 vs T+E2.

P < .05 vs T.

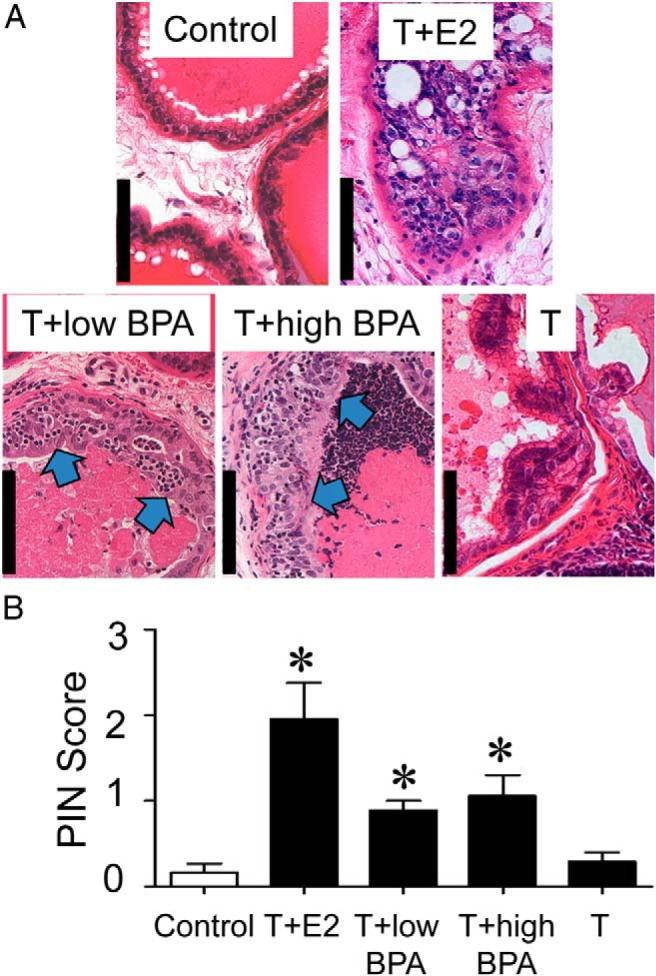

T-supported BPA-induced PIN development and epithelial cell proliferation in LPs

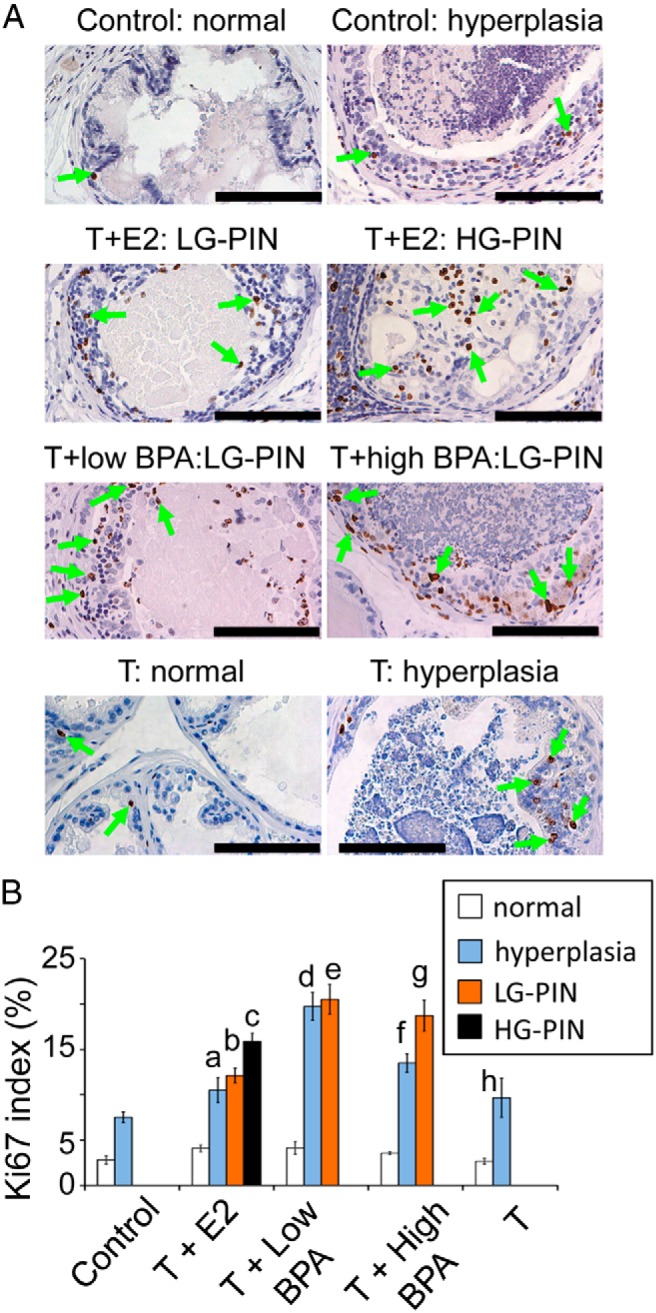

As shown previously (30, 39), T+E2 treatment induced low-grade (LG) PIN (not shown) and high-grade (HG) PIN (Figure 1A) in LPs (PIN incidence, 100%; mean PIN score, 2.0, Figure 1B). Only LG-PIN was detected in LPs treated with T+low/high BPA (T+low BPA: PIN incidence 100%; mean PIN score 0.9; T+high BPA: PIN incidence 100%; mean PIN score 1.0, Figure 1, A and B). The histology of LPs of untreated control and T-treated rats remained normal (Figure 1A). No PIN lesions were observed in VPs, DPs, and APs of untreated, T+E2-treated, or T+low/high BPA-treated rats (not shown). To correlate the observed hyperplastic/preneoplastic changes with cell proliferation activity, the Ki67 index was determined in the epithelial compartments of various proliferative lesions (hyperplasia, LG-PIN, and HG-PIN) in LPs across treatments. T+E2 and T+low/high BPA significantly increased epithelial cell proliferation in the regions of hyperplasia, LG-PIN, and/or HG-PIN (Figure 2, A and B). Notably, the rates of cell proliferation in the groups treated with T+low BPA (hyperplasia and LG-PIN) and T+high BPA (LG-PIN) were significantly higher than those of the respective lesions identified in the T+E2-treated group. T treatment alone displayed a similar cell proliferation rate in the rat LPs when compared with the no-treatment control (Figure 2, A and B).

Figure 1.

A, Representative hematoxylin/eosin-stained sections from LPs of the five treatment groups. Untreated or T-treated control LPs show normal glandular architecture with little or no infiltration by inflammatory cells. T+E2-treated LPs exhibit an HG-PIN lesion with a typical cribriform pattern. T+low/high BPA exposure induced the development of LG-PIN in LPs, as evidenced by the presence of pleomorphic nuclei in the dysplastic epithelium (blue arrows). B, Mean PIN scores across treatment groups. Bar, 100 μm. *, P < .01 vs control.

Figure 2.

A, Representative Ki-67 staining (green arrows) of specific regions of LPs across treatment groups. B, Ki-67 index of normal or specific histological lesions (hyperplasia, LG-PINs, or HG-PINs) of LPs across treatment groups. Bar, 100 μm. a, P < .05 vs control: normal; T+E2: normal; T+E2: HG-PIN; T+low BPA: hyperplasia. b, P < .05 vs control: normal; T+E2: normal; T+low BPA: LG-PIN; T+high BPA: LG-PIN. c, P < .05 vs control: normal; T+E2: normal; T+E2: hyperplasia. d, P < .05 vs control: normal; control: hyperplasia; T+low BPA: normal; T+E2: hyperplasia; T+high BPA: hyperplasia; T: hyperplasia. e, P < .05 vs control: normal; T+low BPA: normal; T+E2: LG-PIN. f, P < .05 vs control: normal; control: hyperplasia; T+low BPA: hyperplasia; T+high BPA: normal. g, P < .05 vs control: normal; T+E2: LG-PIN; T+high BPA: normal. h, P < .05 vs control: normal; T: normal; T+low BPA: hyperplasia

T-supported BPA-induced intraepithelial lymphocyte infiltration in LPs

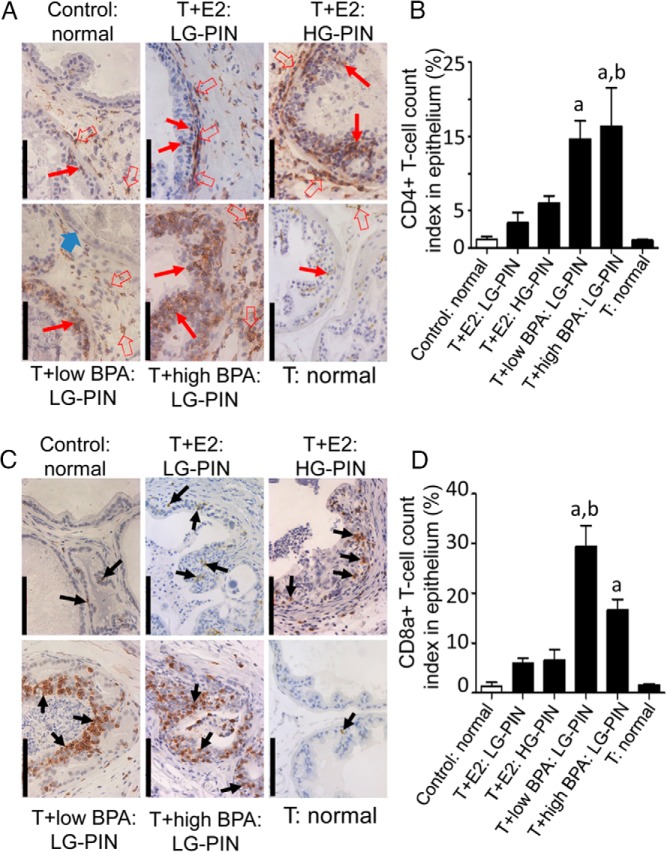

Histological evaluations revealed inflammatory cell infiltration in LPs but not in other prostate lobes (data not shown). The lymphocyte infiltration of LPs was localized by immunostaining tissue sections for CD4+ and CD8a+ T lymphocytes (Figure 3, A and C, respectively). In untreated control LPs, CD4+ and CD8a+ cells were rarely found in the stromal region. T+E2 treatment provoked a massive infiltration of CD4+ cells into the dysplastic epithelium and periacinar stroma, whereas CD8a+ infiltration was less pronounced. In T+low/high BPA-treated LPs, massive infiltration of both CD4+ and CD8a+ cells was found in the dysplastic epithelium but not in the adjacent periglandular stroma, histologically normal acini, or hyperplastic glands. Quantitative analysis of intraepithelial T cells revealed that T+low/high BPA treatment significantly (P < .05) elevated the infiltration of both CD4+ and CD8a+ cells into the PIN epithelium compared with the no-, T+E2-, and T-treatment (Figure 3, B and D). Notably, approximately 15%–30% of the epithelia were made up of these immune cells, representing a severe disruption of the epithelial architecture. Interestingly, T+low BPA induced more CD8a+ cells infiltrating to the PIN epithelium than T+high BPA (P < .05, Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

T+BPA treatment induced infiltration of CD4+ and CDa8+ T cells into PIN epithelium of LPs. A, Immunohistochemical localization of CD4+ T cells (red arrows: epithelium; red open arrows: stroma) in LPs across treatments: in normal and T-treated control LPs, CD4+ T cells were occasionally found in the epithelium and stroma; in T+E2-treated LP, CD4+ T cells were found in the epithelium and stroma of LG- and HG-PIN lesions; in T+low BPA-treated LP, numerous CD4+ T cells were infiltrated to the LG-PIN gland. An adjacent normal gland is free of any CD4+ cell infiltration (blue arrow). In T+high BPA-treated LP, massive infiltration of CD4+ T cells was observed in the PIN epithelium. B, Quantitation of CD4+ T-cell infiltration into the normal and PIN epithelium across treatments. The number of CD4+ T cells was significantly increased in the PIN epithelium of T+low/high BPA-treated LPs when compared with untreated or T-treated controls or LG-PIN glands in T+E2-treated LPs. a, P < .05 vs control: normal; T+E2: LG-PIN; T: normal. b, P < .05 vs T+E2: HG-PIN. C, Immunohistochemical localization of CD8a+ T cells (black arrows) in LPs across treatments: in untreated or T-treated control LPs, CD8+ T cells were sporadically detected in normal glandular epithelium; in T+E2-treated LP, a few CD8a+ T cells were localized in the LG-/HG-PIN epithelium; in T+low BPA-treated LP, clusters of CD8a+ T cells were often detected in PIN epithelium; in T+high BPA-treated LP, numerous CD8a+ cells were infiltrated into PIN epithelium. Bar, 100 μm. D, Quantitation of CD8a+ T-cell infiltration into the normal and PIN epithelium across treatments. The number of epithelium-infiltrating CD8a+ T cells was significantly higher in the PIN glands of T+low/high BPA-treated LPs than in the normal/PIN glands of untreated, T+E2-treated, and T-treated LPs. a, P < .05 vs control: normal; T+E2: LG-PIN; T+E2: HG-PIN; T: normal. b, P < .05 vs T+high BPA: LG-PIN.

Identification of T+low BPA gene signatures in LPs

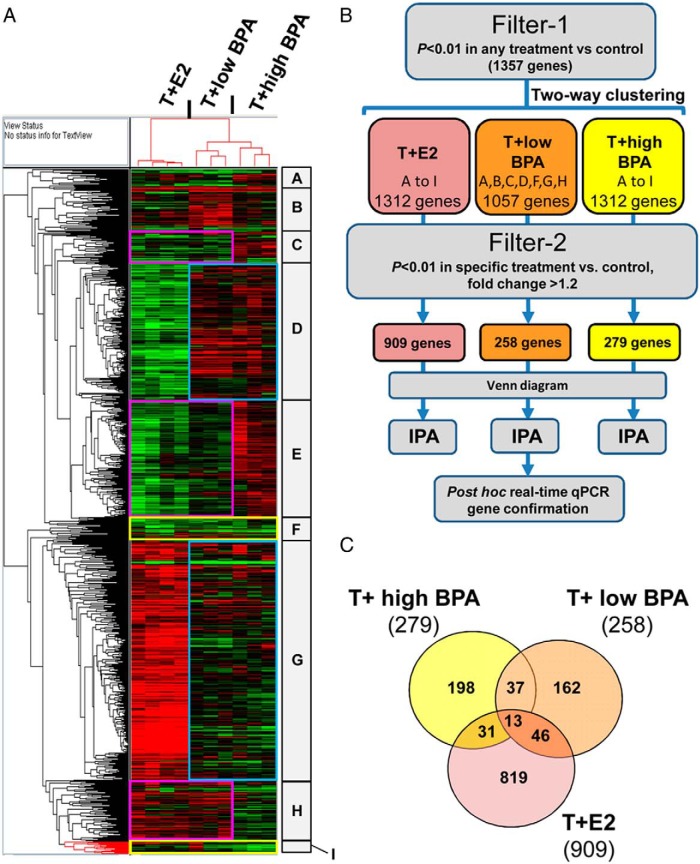

We next conducted microarray analysis to determine the effects of environmentally relevant doses of BPA on adult rat LPs. Treatment with T+E2, T+low BPA, or T+high BPA altered 1357 genes in rat LPs (filter-1: one way ANOVA, P < .01, any treatment vs control). Two-way clustering analysis showed distinct visual patterns of BPA-regulated genes similar to or different from that of T+E2 (Figure 4A). To identify T+BPA specific genes, we further filtered a combined blocks of genes associated with a specific treatment using filter 2 (one way ANOVA, P < .01 and fold change > 1.2 of a specific treatment vs control). In summary, 258 genes were differentially expressed in the LPs of T+low BPA-treated rats, whereas 279 genes were differentially expressed in the LPs of T+high BPA-treated rats (Figure 4, B and C). T+E2 induced differential expression of 909 genes (one way ANOVA, P < .01 and fold change greater than 1.2, Figure 4, B and C). Complete lists of differentially expressed genes in the T+low BPA-, T+high BPA-, or T+E2-treated groups are available (Supplemental Tables 3–5).

Figure 4.

Two-way hierarchical clustering of differential genes expressed across treatment groups. A, Heat map showing genes differentially expressed in the LP of T+E2-treated, T+low BPA-treated, and T+high BPA-treated groups as compared with the untreated control group. Red, Up-regulated; green, down-regulated. Specific blocks (A–I) of gene clusters are denoted as high and/or low BPA-sensitive clusters. Pink boxes, Clusters of genes showing the same response to T+low BPA and T+E2 but displaying a distinctive pattern of expression in response to T+high BPA. Blue boxes, Clusters of genes revealing the same pattern of response to T+low BPA and T+high BPA but showing a different pattern of response to T+E2. Yellow boxes, Clusters of genes showing similar responses in all treatment groups. B, A schematic diagram demonstrating approaches for gene categorization, shaving with the filter 1 and filter 2 (two-way clustering, Venn diagram representation, network mapping, and post hoc confirmation). C, Venn diagram represents the population of significantly differentiated genes in the treatment groups after shaving with the filter 2 (P < .01 vs control, fold change > 1.2). Numbers of genes that are significant for a specific treatment were shown.

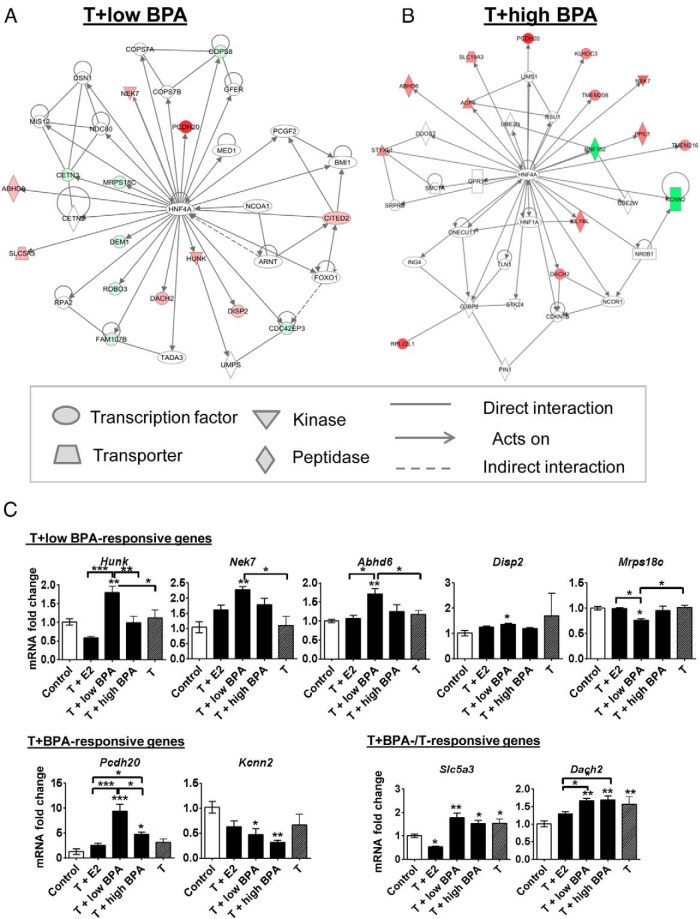

Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (HNF4) α as a regulatory node for T+BPA treatment

To provide biological relevance of chronic BPA exposure in an adult male with a physiologically normal level of T, we examined the gene networks altered by T+low BPA in rat LPs. IPA showed that the top five molecular and cellular functions modified by T+low BPA were related to cell cycle, cellular development, cell function and maintenance, cell growth and proliferation, and DNA replication/recombination/repair (Supplemental Table 6). Notably, a tight network of genes altered by T+low BPA are direct targets of HNF4α, as depicted by the solid arrow radiating from the HNF4α node (Figure 5A and Supplemental Figure 1). T+high BPA also altered gene expression related to HNF4α (Figure 5B) and common pathways stimulated by T+E2, including nuclear factor-κB, ERK1/2, and insulin-related signaling (Supplemental Figures 2 and 3 and Supplemental Tables 7 and 8). A summary of IPA networks of genes altered by T+E2, T+low BPA, and T+low BPA is shown in Supplemental Table 9. Interestingly, in addition to the HNF4α-regulated genes, T+high BPA also induced differential gene expression in pathways previously shown to be indirectly stimulated by E2 (Supplemental Figure 2D).

Figure 5.

HNF4α network and post hoc real-time qPCR analyses of the T+low BPA-responsive genes. Molecular interaction network by IPA demonstrated that HNF4α as a central node of genes was regulated by T+low BPA (A) and T+high BPA (B) treatment in the rat LPs. The intensity of genes indicates the degree of up-regulation (red) or down-regulation (green) of a specific gene. Different shapes represented the functional classes of the gene, and the direct or indirect relationship between genes is linked by lines (see legend). Molecules in white were not directly involved in treatment response but were related to the imported molecules. C, Genes involved in the HNF4α-related pathway were validated in the LPs of control-, T+E2-, T+low BPA-, T+high BPA-, and T-treated rats. Values are normalized to Rpl19 and are expressed relative to the LPs of control-treated rats for a specific transcript. Results are analyzed by a one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni test. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *, P < .05,**, P < .01, and ***, P < .001 compared with control unless otherwise specified.

Confirmation of T+low BPA-responsive genes by real-time qPCR

To validate these HNF4α-regulated genes responsive to T+low BPA, we designed primers for 11 genes in the T+low BPA-HNF4α network as well as Kcnn2, which is also a direct target of HNF4α (40), for real-time qPCR analyses. As shown in Figure 5C, five of these genes (Hunk, Nek7, Abhd6, Disp2, and Mrps18c) were shown to be exclusively responsive to T+low BPA, whereas two of these genes (Pcdh20 and Kcnn2) were confirmed to be responsive to both T+low and T+high BPA. Slc5a3 and Dach2 were confirmed to be responsive to T+low/high BPA or T but not T+E2. A nonsignificant change in three of these HNF4α-regulated genes (Fam107b, Dem1, and Cetn3, Supplemental Figure 4) was seen in the T+low BPA treatment group. For in-house quality control, the top down-regulated genes (Tgm4 and Itln1) that were common to the T+low and T+high BPA groups, but irrelevant to the HNF4α network, were also confirmed (Supplemental Figure 5).

Discussion

To restore the BPA-suppressed androgenic status of rats with chronic BPA exposure (29), we coimplanted T-filled SILASTIC brand capsules (Dow Corning) to clamp serum T levels at a narrow physiological range. This study provided the first evidence to show the procarcinogenic effects and immune disruption action of BPA exposure with the support of T on the prostate gland of the adult rat and identified the HNF4α-regulatory gene network as a target for a low-dose, human relevant BPA exposure. Our findings indicate that chronic BPA exposure, even at low doses, induces hyperplasia (characterized by increase in prostate weight and cell proliferation), an inflammatory response (characterized by T lymphocyte infiltration to the glandular epithelium), and emergence of LG-PIN (a procarcinogenic response) in rat prostate glands. The heightened proliferative and inflammatory status of the PIN lesions induced by T+low/high BPA, when compared with T+E2, suggests a fundamental difference in the natural history of PIN development triggered by these two types of estrogens, endogenous E2 and synthetic BPA.

The routine detection of BPA in human sera, with a short half-life of BPA (<6 h), suggested a continuous mode of BPA exposure for humans (3). Dermal exposure to BPA, in addition to exposure by the oral route, has been recognized as a major source of contamination (41, 42). We quantified BPA levels using highly sensitive liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (detection limit 0.05 ng/mL) recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (33), and the sc BPA implantation consistently reproduced internal levels of BPA observed in human population (3–5). Animal data from the NTP suggested that BPA is not a carcinogen in the context of adult exposure (6). However, previous studies by our group and others have linked neonatal BPA exposure to prostatic abnormities including increased PCa risk later in life (12–14), proliferation (43–45), migration (45), anchorage-independent growth (15), centrosome amplification (15), and DNA adducts formation (46). To date, the link between adult exposure to BPA and prostate pathology has not been adequately studied. Our data clearly demonstrated that elevated internal BPA levels at a dose range relevant to human exposure initiated prostatic proliferative/inflammatory lesions, as characterized by emergence of LG-PIN accompanied by augmented epithelial cell proliferation and inflammatory cell infiltration. However, no HG-PIN, which is regarded as a PCa precursor, or overt PCa was detected in the prostate exposed to BPA in this model. Given that heightened cellular proliferation and chronic inflammation are risk factors of PCa in human, chronic BPA exposure may initiate preneoplastic changes per se, but we did not find it sufficient to promote oncogenic progression to cancer in rats at the current setting. Prolonged treatment is warranted to determine whether BPA-treated rats will reach the stage of HG-PIN and PCa.

In this study, chronic exposure to T+low/high-dose BPA increased the prostate weights. This growth-promoting effect by T+low/high BPA was more pronounced than that by T+E2 in VP, DP, and AP, which were free of PIN and inflammation. BPA exposure in utero stimulated the fetal prostate growth (16) and permanently increased the prostate size in male adult offspring (17). Our data agree with a previous report demonstrating that oral exposure to environmentally relevant doses of BPA aggravated T-induced BPH in adult rats (21). It is interesting that BPA stimulated self-renewal and amplification of human prostate epithelial stem-like cells derived from young adult disease-free organ donors (14). This recent report suggested that epithelial stem/progenitor cells in the adult prostate are direct BPA targets that may play a critical role in prostatic disorders in the context of chronic environmental exposure to BPA.

A National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey study has correlated BPA exposures to numerous immune and inflammatory disorders in humans (47). BPA has been shown to modulate the proliferation and differentiation of T lymphocytes in the spleen and thymus (48). Our data showed that chronic BPA exposure promotes massive infiltration of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells specifically in the dysplastic epithelium of PIN lesions but these T cells were rarely or sporadically found in the adjacent normal and hyperplastic epithelium. This observation implicates that sustained epithelial proliferation and preneoplastic changes in the T+BPA-induced PIN could be reactive to intraepithelial T-cell infiltration. The role of CD4+ T cells in carcinogenesis is controversial (49). CD4+ regulatory T cells have been shown to promote (50) or suppress (51) the progression of PCa in different mouse models. In men, infiltration of higher numbers of CD4+ regulatory T cells in prostate tumors correlate with an increasing risk of lethal PCa (32). In addition, known antitumor effectors CD8+ T cells are induced to become immunosuppressive cells in the prostate tumor microenvironment (52) and to promote early progression of PCa in a transgenic mouse model (52, 53). Taken together, the results of our study suggest that BPA exposure in adulthood alters the T-cell status of prostate glands, possibly predisposing to tumorigenesis.

A primary aim of the present study was to assess whether exposures to BPA at low and high doses (at a physiologically normal T level) display similar estrogen-like effects on gene expression programming in adult rat LPs. This is the first study reporting the global transcriptional responses of the rat prostate to human-relevant internal levels of BPA (low dose BPA in the present study). The gene expression alternation altered by low doses of BPA partially resembled those of E2 (reference physiological estrogen) in the support of physiological T. In contrast, BPA at higher doses (reproducing a 10-fold increase of internal levels of free BPA) had a rather different transcriptional influence than E2 under normal T level. These molecular profiles suggest that BPA has only modest estrogenic activity, consistent with a recent report demonstrating that BPA is a weak estrogen based on global uterine gene expression (54). Our findings implicate that BPA at levels within the range observed in the human population as acting more like E2 than BPA at higher doses in the prostate. A recent study showed that BPA at low doses (10 nM) has the same activational capabilities as E2 through rapid signaling pathways in prostate stem/progenitor cells (14). Future studies accommodating a wider range of BPA doses are required to determine whether BPA produces a nonmonotonic response on gene expression and induces other pathological outcomes.

We identified a transcription factor, HNF4α (or NR2A1), as a unique BPA-responsive regulatory hub in T-supported rat LPs. HNF4α is the most abundant DNA-binding protein in the liver. Approximately 40% of the actively transcribed genes in the liver have an HNF4α response element, and these genes are largely involved in the hepatic gluconeogenic program and lipid metabolism (55). HNF4α is a key regulator for hepatocyte differentiation in embryonic development and the maintenance of hepatocyte differentiation in the mature liver (56, 57). A majority of genes regulated by HNF4α respond to cytokine treatment, suggesting that HNF4α may be involved in the regulation of the hepatic inflammatory response (58). Indeed, we observed infiltration of T cells to the prostate epithelium upon BPA exposure, a response associated with the deregulation of the HNF4α network. Activation of HNF4α controls the switch between the transcriptional and adhesion functions of Wnt/β-catenin (59), resulting in the transactivation of T-cell factor target genes and the primary transforming event in colorectal cancer (60). In addition, stabilization of β-catenin is a crucial event for the initiation of PIN-like lesions (61). HNF4α also regulates the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (59), a process that has been demonstrated to be involved in PIN development in a mouse model (62). Whether the increase in hyperplasia and LG-PIN observed in the T+low BPA treatment group in the present study is associated with a stabilization of nuclear β-catenin or an increase in epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype requires further investigation.

HNF4α-responsive genes display an enrichment of the ETS family of transcription factors, including ELK1 and ELK4, in the promoter regions in liver HepG2 cells, suggesting HNF4α may regulate target genes via the ETS family (58). Similarly, one of the BPA-downregulated genes, potassium intermediate/small conductance calcium-activated channel (Kcnn2), which encodes for a potassium channel protein, is a potential ETS transcription factor target that is down-regulated in PCa (63). Most BPA-up-regulated genes are associated with oncogenesis. Dachshund family transcription factor 2 (Dach2), which is highly expressed in ovarian cancer, predicts a poor prognosis (64). NIMA (never in mitosis gene a)-related kinase 7 (Nek7) kinase is enriched at the centrosome and is required for proper spindle assembly and mitotic progression (65). Furthermore, NEK7 contributes to mitotic progression (66), and the up-regulation of NEK7 promotes oncogenesis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (67). Hormonally up-regulated Neu-associated kinase (Hunk) is required for HER2/neu-induced mammary tumorigenesis, cell proliferation (68), and tumor metastasis (69). Abhydrolase domain containing 6 (Abhd6) is a serine-hydrolyzing enzyme with typical α/β-hydrolase family domains that is absent in the normal prostate tissue but at high levels in PCa PC3 cells (70). However, protocadherin 20 (Pcdh20) is a tumor suppressor gene that antagonizes Wnt/ β-catenin in hepatocellular carcinoma (71). Other BPA-responsive genes include solute carrier family 5 member 3 (Slc5a3), which functions in cellular osmoregulation (72). Dispatched homolog 2 (Drosophila, DISP2), identified in Drosophila, is required for the release of cholesterol-anchored Hedgehog to maintain normal Hedgehog signaling (73). Finally, mitochondrial ribosomal protein S18C (Mrps18c) is a mitochondrial ribosomal protein that contributes to protein synthesis within the mitochondrion (74).

Our study was constrained by the limited number of animals per treatment group. Despite the relatively low sample size, the serum T and BPA measurements revealed a substantial homogeneity in the internal doses achieved. Furthermore, our findings showed a high consistency on prostate phenotypes and gene alterations associated with T+E2 and T+BPA within each group. In the present study, we chose to use NBL rats, which are inbred rats with high susceptibility to estrogen-induced prostate carcinogenesis compared with outbred Sprague Dawley rats (75). The robust phenotypes observed with the small sample size herein could be attributed to the expected small genetic background variation of this rat strain and highly consistent prostatic responses to estrogens. Our gene expression data showed that both BPA doses induced a common HNF4α pathway; however, there are other pathways distinct to a specific dose of BPA. The phenotype/time point that we assessed here was not able to identify the differential BPA-induced prostate phenotypic changes, and whether the low- and high-dose BPA demonstrates different HG-PIN- or PCa-inducing effects warrants longer follow-up investigations.

In summary, this study provides the first evidence that the adult prostate remains vulnerable to environmental exposure to BPA, with increased proliferation, heightened inflammatory responses, and emergence of preneoplastic lesions. Notably, our results suggest that prostatic responses (eg, gene expression, proliferation, and CD8+ T-cell infiltration) may be more profound in human-relevant low-dose BPA when compared with the high-dose BPA, consistent with our previous report (15) and the typical nonlinear response to estrogenic compounds in hormone-responsive organs (76). BPA is ubiquitous, and PCa takes decades to develop. We propose that continuous exposure to BPA may interact with other oncogenic insults, such as aging or exposure to other carcinogens, to trigger the progression of PCa late in life. Our findings also provide a comprehensive analysis on novel BPA-responsive genes and their networks under the influence of T in normal adult males, underscoring the molecular link between endocrine disruption and prostate diseases.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Mr Saikumar Karyala and the Genomics, Epigenomic, and Sequencing Core at the University of Cincinnati for the Affymetrix microarray experiments; Dan Song for the immunohistochemistry; Hong Xiao for the Ki67 index analysis; Dr Linda Levin for her expertise in the statistical analysis; and Nancy K. Voynow for her professional editing of this manuscript. We also thank Dr Kurunthachalam Kannan for the BPA measurement and the Ligand Assay and Analysis Core at the University of Virginia for the T assay.

Current address for H.-M.L.: Department of Urology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

Current address for J.C.: Biomedical Informatics, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio.

This work was supported by Grants from the U.S. National Cancer Institute: R01CA015776 (to S.-M.H.), R01CA112532 (to S.-M.H.), R21CA156042 (to N.N.C.T.); the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences: R01ES015584 (to S.-M.H.), U01ES019480 (to S.-M.H.), U01ES020988 (to S.-M.H.), P30ES006096 (to S.-M.H.), RC2ES018789 (to S.-M.H.), and RC2ES018758 (to S.-M.H.); the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: I01BX000675 (to S.-M.H.); the U.S. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute: U54HL127624 (to M.M.); and the U.S. Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award (to H.-M.L.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AP

- anterior prostate

- BPA

- bisphenol A

- DP

- dorsal prostate

- E2

- 17β-estradiol

- HG

- high grade

- HNF4

- hepatocyte nuclear factor 4

- IPA

- Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software

- LG

- low grade

- LP

- lateral prostate

- NBL

- Noble

- NEK7

- NIMA-related kinase 7

- NTP

- National Toxicology Program

- PCa

- prostate cancer

- PIN

- prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- VP

- ventral prostate.

References

- 1. Dodds EC, Fitzgerald MEH, Lawson W. Oestrogenic activity of some hydrocarbon derivatives of ethylene. Nature. 1937;140:772. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rubin BS. Bisphenol A: an endocrine disruptor with widespread exposure and multiple effects. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;127:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vandenberg LN, Hauser R, Marcus M, Olea N, Welshons WV. Human exposure to bisphenol A (BPA). Reprod Toxicol. 2007;24:139–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vandenberg LN, Chahoud I, Heindel JJ, Padmanabhan V, Paumgartten FJ, Schoenfelder G. Urinary, circulating, and tissue biomonitoring studies indicate widespread exposure to bisphenol A. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1055–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, Reidy JA, Needham LL. Exposure of the US population to bisphenol A and 4-tertiary-octylphenol: 2003–2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Toxicology Program. Carcinogenesis bioassay of bisphenol A (CAS no. 80-05-7) in F344 rats and B6C3F1 mice (feed study). National Toxicology Program Technical Report Series. 1982;No. 215:1–116. (NIH publication no. 82-1771). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vandenberg LN, Maffini MV, Sonnenschein C, Rubin BS, Soto AM. Bisphenol-A and the great divide: a review of controversies in the field of endocrine disruption. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:75–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuiper GG, Lemmen JG, Carlsson B, et al. Interaction of estrogenic chemicals and phytoestrogens with estrogen receptor β. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4252–4263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Recchia AG, Vivacqua A, Gabriele S, et al. Xenoestrogens and the induction of proliferative effects in breast cancer cells via direct activation of oestrogen receptor α. Food Addit Contam. 2004;21:134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leung YK, Mak P, Hassan S, Ho SM. Estrogen receptor (ER)-β isoforms: a key to understanding ER-β signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13162–13167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thomas P, Dong J. Binding and activation of the seven-transmembrane estrogen receptor GPR30 by environmental estrogens: a potential novel mechanism of endocrine disruption. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;102:175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ho SM, Tang WY, Belmonte de Frausto J, Prins GS. Developmental exposure to estradiol and bisphenol A increases susceptibility to prostate carcinogenesis and epigenetically regulates phosphodiesterase type 4 variant 4. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5624–5632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prins GS, Ye SH, Birch L, Ho SM, Kannan K. Serum bisphenol A pharmacokinetics and prostate neoplastic responses following oral and subcutaneous exposures in neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats. Reprod Toxicol. 2011;31:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prins GS, Hu WY, Shi GB, et al. Bisphenol A promotes human prostate stem-progenitor cell self-renewal and increases in vivo carcinogenesis in human prostate epithelium. Endocrinology. 2014;155:805–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tarapore P, Ying J, Ouyang B, Burke B, Bracken B, Ho SM. Exposure to bisphenol A correlates with early-onset prostate cancer and promotes centrosome amplification and anchorage-independent growth in vitro. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Timms BG, Howdeshell KL, Barton L, Bradley S, Richter CA, vom Saal FS. Estrogenic chemicals in plastic and oral contraceptives disrupt development of the fetal mouse prostate and urethra. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7014–7019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nagel SC, vom Saal FS, Thayer KA, Dhar MG, Boechler M, Welshons WV. Relative binding affinity-serum modified access (RBA-SMA) assay predicts the relative in vivo bioactivity of the xenoestrogens bisphenol A and octylphenol. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105:70–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ashby J, Tinwell H, Haseman J. Lack of effects for low dose levels of bisphenol A and diethylstilbestrol on the prostate gland of CF1 mice exposed in utero. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1999;30:156–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cagen SZ, Waechter JM, Jr, Dimond SS, et al. Normal reproductive organ development in CF-1 mice following prenatal exposure to bisphenol A. Toxicol Sci. 1999;50:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stoker TE, Robinette CL, Britt BH, Laws SC, Cooper RL. Prepubertal exposure to compounds that increase prolactin secretion in the male rat: effects on the adult prostate. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:1636–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu JH, Jiang XR, Liu GM, Liu XY, He GL, Sun ZY. Oral exposure to low-dose bisphenol A aggravates testosterone-induced benign hyperplasia prostate in rats. Toxicol Ind Health. 2011;27:810–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ho SM, Leav I, Damassa D, Kwan PW, Merk FB, Seto HS. Testosterone-mediated increase in 5α-dihydrotestosterone content, nuclear androgen receptor levels, and cell division in an androgen-independent prostate carcinoma of Noble rats. Cancer Res. 1988;48:609–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leav I, Galluzzi CM, Ziar J, Stork PJ, Ho SM, Loda M. Mitogen-activated protein kinase and mitogen-activated kinase phosphatase-1 expression in the Noble rat model of sex hormone-induced prostatic dysplasia and carcinoma. Lab Invest. 1996;75:361–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaplan PJ, Leav I, Greenwood J, Kwan PW, Ho SM. Involvement of transforming growth factor α (TGFα) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in sex hormone-induced prostatic dysplasia and the growth of an androgen-independent transplantable carcinoma of the prostate. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:2571–2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ouyang XS, Wang X, Lee DT, Tsao SW, Wong YC. Up-regulation of TRPM-2, MMP-7 and ID-1 during sex hormone-induced prostate carcinogenesis in the Noble rat. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cavalieri EL, Devanesan P, Bosland MC, Badawi AF, Rogan EG. Catechol estrogen metabolites and conjugates in different regions of the prostate of Noble rats treated with 4-hydroxyestradiol: implications for estrogen-induced initiation of prostate cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tam NN, Szeto CY, Sartor MA, Medvedovic M, Ho SM. Gene expression profiling identifies lobe-specific and common disruptions of multiple gene networks in testosterone-supported, 17β-estradiol- or diethylstilbestrol-induced prostate dysplasia in Noble rats. Neoplasia. 2008;10:20–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tam NN, Szeto CY, Freudenberg JM, Fullenkamp AN, Medvedovic M, Ho SM. Research resource: estrogen-driven prolactin-mediated gene-expression networks in hormone-induced prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:2207–2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Castro B, Sanchez P, Torres JM, Preda O, del Moral RG, Ortega E. Bisphenol A exposure during adulthood alters expression of aromatase and 5α-reductase isozymes in rat prostate. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tam NN, Leav I, Ho SM. Sex hormones induce direct epithelial and inflammation-mediated oxidative/nitrosative stress that favors prostatic carcinogenesis in the noble rat. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1334–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gilleran JP, Putz O, DeJong M, et al. The role of prolactin in the prostatic inflammatory response to neonatal estrogen. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2046–2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Davidsson S, Ohlson AL, Andersson SO, et al. CD4 helper T cells, CD8 cytotoxic T cells, and FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells with respect to lethal prostate cancer. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:448–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Padmanabhan V, Siefert K, Ransom S, et al. Maternal bisphenol-A levels at delivery: a looming problem? J Perinatol. 2008;28:258–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kauffmann A, Gentleman R, Huber W. arrayQualityMetrics—a bioconductor package for quality assessment of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:415–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smyth GK. 2004 Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 3:Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dai M, Wang P, Boyd AD, et al. Evolving gene/transcript definitions significantly alter the interpretation of GeneChip data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chan QK, Lam HM, Ng CF, et al. Activation of GPR30 inhibits the growth of prostate cancer cells through sustained activation of Erk1/2, c-jun/c-fos-dependent upregulation of p21, and induction of G(2) cell-cycle arrest. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:1511–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lam HM, Ouyang B, Chen J, et al. Targeting GPR30 with G-1: a new therapeutic target for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:903–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leav I, Ho SM, Ofner P, Merk FB, Kwan PW, Damassa D. Biochemical alterations in sex hormone-induced hyperplasia and dysplasia of the dorsolateral prostates of Noble rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80:1045–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Odom DT, Zizlsperger N, Gordon DB, et al. Control of pancreas and liver gene expression by HNF transcription factors. Science. 2004;303:1378–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Biedermann S, Tschudin P, Grob K. Transfer of bisphenol A from thermal printer paper to the skin. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;398:571–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Porras SP, Heinala M, Santonen T. Bisphenol A exposure via thermal paper receipts. Toxicol Lett. 2014;230:413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wetherill YB, Petre CE, Monk KR, Puga A, Knudsen KE. The xenoestrogen bisphenol A induces inappropriate androgen receptor activation and mitogenesis in prostatic adenocarcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:515–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wetherill YB, Hess-Wilson JK, Comstock CE, et al. Bisphenol A facilitates bypass of androgen ablation therapy in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:3181–3190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Derouiche S, Warnier M, Mariot P, et al. Bisphenol A stimulates human prostate cancer cell migration via remodelling of calcium signalling. Springerplus. 2013;2:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. De Flora S, Micale RT, La Maestra S, et al. Upregulation of clusterin in prostate and DNA damage in spermatozoa from bisphenol A-treated rats and formation of DNA adducts in cultured human prostatic cells. Toxicol Sci. 2011;122:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Clayton EM, Todd M, Dowd JB, Aiello AE. The impact of bisphenol A and triclosan on immune parameters in the US population, NHANES 2003–2006. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:390–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rogers JA, Metz L, Yong VW. Review: endocrine disrupting chemicals and immune responses: a focus on bisphenol-A and its potential mechanisms. Mol Immunol. 2013;53:421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Erdman SE, Poutahidis T. Cancer inflammation and regulatory T cells. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:768–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tien AH, Xu L, Helgason CD. Altered immunity accompanies disease progression in a mouse model of prostate dysplasia. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2947–2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Poutahidis T, Rao VP, Olipitz W, et al. CD4+ lymphocytes modulate prostate cancer progression in mice. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:868–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shafer-Weaver KA, Anderson MJ, Stagliano K, Malyguine A, Greenberg NM, Hurwitz AA. Cutting edge: tumor-specific CD8+ T cells infiltrating prostatic tumors are induced to become suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:4848–4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Diener KR, Woods AE, Manavis J, Brown MP, Hayball JD. Transforming growth factor-β-mediated signaling in T lymphocytes impacts on prostate-specific immunity and early prostate tumor progression. Lab Invest. 2009;89:142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hewitt SC, Korach KS. Estrogenic activity of bisphenol A and 2,2-bis(p-hydroxyphenyl)-1,1,1-trichloroethane (HPTE) demonstrated in mouse uterine gene profiles. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chandra V, Huang P, Potluri N, Wu D, Kim Y, Rastinejad F. Multidomain integration in the structure of the HNF-4α nuclear receptor complex. Nature. 2013;495:394–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li J, Ning G, Duncan SA. Mammalian hepatocyte differentiation requires the transcription factor HNF-4α. Genes Dev. 2000;14:464–474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hayhurst GP, Lee YH, Lambert G, Ward JM, Gonzalez FJ. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (nuclear receptor 2A1) is essential for maintenance of hepatic gene expression and lipid homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1393–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang Z, Bishop EP, Burke PA. Expression profile analysis of the inflammatory response regulated by hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yang M, Li SN, Anjum KM, et al. A double-negative feedback loop between Wnt-β-catenin signaling and HNF4α regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:5692–5703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. van de Wetering M, Sancho E, Verweij C, et al. The β-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell. 2002;111:241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gounari F, Signoretti S, Bronson R, et al. Stabilization of β-catenin induces lesions reminiscent of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, but terminal squamous transdifferentiation of other secretory epithelia. Oncogene. 2002;21:4099–4107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sun F, Chen HG, Li W, et al. Androgen receptor splice variant AR3 promotes prostate cancer via modulating expression of autocrine/paracrine factors. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:1529–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Camoes MJ, Paulo P, Ribeiro FR, et al. Potential downstream target genes of aberrant ETS transcription factors are differentially affected in Ewing's sarcoma and prostate carcinoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nodin B, Fridberg M, Uhlen M, Jirstrom K. Discovery of dachshund 2 protein as a novel biomarker of poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2012;5:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yissachar N, Salem H, Tennenbaum T, Motro B. Nek7 kinase is enriched at the centrosome, and is required for proper spindle assembly and mitotic progression. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6489–6495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fry AM, O'Regan L, Sabir SR, Bayliss R. Cell cycle regulation by the NEK family of protein kinases. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:4423–4433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Saloura V, Cho HS, Kiyotani K, et al. WHSC1 promotes oncogenesis through regulation of NIMA-related kinase-7 in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;13:293–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yeh ES, Yang TW, Jung JJ, Gardner HP, Cardiff RD, Chodosh LA. Hunk is required for HER2/neu-induced mammary tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:866–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wertheim GB, Yang TW, Pan TC, et al. The Snf1-related kinase, Hunk, is essential for mammary tumor metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15855–15860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Li F, Fei X, Xu J, Ji C. An unannotated α/β hydrolase superfamily member, ABHD6 differentially expressed among cancer cell lines. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36:691–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lv J, Zhu P, Yang Z, et al. PCDH20 functions as a tumour-suppressor gene through antagonizing the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22:201–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mallee JJ, Atta MG, Lorica V, et al. The structural organization of the human Na+/myo-inositol cotransporter (SLC5A3) gene and characterization of the promoter. Genomics. 1997;46:459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Burke R, Nellen D, Bellotto M, et al. Dispatched, a novel sterol-sensing domain protein dedicated to the release of cholesterol-modified hedgehog from signaling cells. Cell. 1999;99:803–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Cavdar KE, Burkhart W, Blackburn K, Moseley A, Spremulli LL. The small subunit of the mammalian mitochondrial ribosome. Identification of the full complement of ribosomal proteins present. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19363–19374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bosland MC, Ford H, Horton L. Induction at high incidence of ductal prostate adenocarcinomas in NBL/Cr and Sprague-Dawley Hsd:SD rats treated with a combination of testosterone and estradiol-17β or diethylstilbestrol. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:1311–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Calabrese EJ. Estrogen and related compounds: biphasic dose responses. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2001;31:503–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]