Abstract

This study aimed to determine the levels of fumonisins produced by Fusarium verticillioides and FUM gene expression on Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) and non-Bt maize, post harvest, during different periods of incubation. Transgenic hybrids 30F35 YG, 2B710 Hx and their isogenic (30F35 and 2B710) were collected from the field and a subset of 30 samples selected for the experiments. Maize samples were sterilized by gamma radiation at a dose of 20 kGy. Samples were then inoculated with F. verticillioides and analyzed under controlled conditions of temperature and relative humidity for fumonisin B1 and B2 (FB1 and FB2) production and FUM1, FUM3, FUM6, FUM7, FUM8, FUM13, FUM14, FUM15, and FUM19 expression. 2B710 Hx and 30F35 YG kernel samples were virtually intact when compared to the non-Bt hybrids that came from the field. Statistical analysis showed that FB1 production was significantly lower in 30F35 YG and 2B710 Hx than in the 30F35 and 2B710 hybrids (P < 0.05). However, there was no statistical difference for FB2 production (P > 0.05). The kernel injuries observed in the non-Bt samples have possibly facilitated F. verticillioides penetration and promoted FB1 production under controlled conditions. FUM genes were expressed by F. verticillioides in all of the samples. However, there was indication of lower expression of a few FUM genes in the Bt hybrids; and a weak association between FB1 production and the relative expression of some of the FUM genes were observed in the 30F35 YG hybrid.

Keywords: transgenic corn, mycotoxins, Fusarium, gene expression, Bacillus thuringiensis

Introduction

Maize (Zea mays L.) is one of the world’s major agricultural crops serving as a staple food for millions, with an annual average production and consumption of 989.2 million metric tons (Mt) and 953.9 Mt (2013-2014), respectively. Brazil is currently the world’s third largest producer, after United States and China, with an average production of 79.3 Mt over the last year (United States Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2014).

Susceptible to fungal and mycotoxin contamination, numerous toxic fungal secondary metabolites can be found in maize, though, fumonisins occur with greatest frequency. Members of the Fusarium fujikuroi species complex, mainly F. verticillioides (Sacc.) Nirenberg and F. proliferatum (Matsush.) Nirenberg, are capable of producing these mycotoxins consistently (Desjardins, 2006). F. verticillioides is one of the most important species associated with maize throughout the world and produces high levels of fumonisins. Contamination with these mycotoxins has a significant impact, compromising the quality of maize products (de la Campa et al., 2005).

Based on chemical structure, fumonisins have been classified into A, B, C, and P groups; the most common are the B analogs and fumonisin B1 (FB1) is the most prevalent and toxic of the group (Stepien et al., 2011). Fumonisin B1 is known to cause toxicity in animals and humans due to the inhibition of sphingolipid metabolism and cell cycle regulation, resulting in diverse and complex effects. Examples include leukoencephalomalacia in horses, pulmonary oedema, and hydrothorax in swine; fumonisin B1 is additionally carcinogenic to rodents and exhibits nephrotoxic as well as hepatotoxic activity in rats and rabbits (Desjardins, 2006). Epidemiological studies have suggested that fumonisins may also be associated with oesophageal cancer and neural tube birth defects in humans (Marasas et al., 2004).

In F. verticillioides, fumonisin production is regulated by the fumonisin biosynthetic gene cluster (FUM), which consists of 16 genes encoding biosynthetic enzymes, regulatory, and transport proteins (Proctor et al., 2013). FUM1 catalyzes the synthesis of a linear polyketide that forms the backbone structure of fumonisins. FUM8 encodes an α-oxoamine synthase responsible for the condensation of the linear polyketide with alanine (Proctor et al., 2003, 2013; Lazzaro et al., 2012; Medina et al., 2013). The cluster also encodes a C-3 carbonyl reductase (FUM13), and cytochrome P450 oxygenases (FUM2, FUM3, FUM6, FUM15; Proctor et al., 2003; Bojja et al., 2004). The genes FUM7, FUM10, FUM11, FUM14, and FUM16 are required for tricarballylic acid esterification. FUM17 and FUM18 are longevity assurance factors; and FUM19 encodes a protein highly similar to ABC multidrug transporters, which can possibly reduce cellular concentration of toxins, therefore conferring self-protection (Proctor et al., 2003; Bojja et al., 2004; Desjardins, 2006). FUM21 encodes a Zn(II)2Cys6 binuclear DNA-binding transcription factor that positively regulates FUM gene expression (Brown et al., 2007). Studies have demonstrated that these genes are correlated with fumonisin production (Lopez-Errasquín et al., 2007; Medina and Magan, 2010; Rocha et al., 2011) and the expression of some mycotoxin genes respond positively to different environmental conditions (Medina and Magan, 2010).

Globally, fumonisin contamination in food is a concern. The FDA (the United States Food and Drug Administration) has established a limit of 3–4 ppm of fumonisin contamination (FB1 + FB2 + FB3) in human foods and 5–100 ppm in animal feeds. The Commission Regulation (EC) of the European Union has established a maximum level of 4 ppm for FB1 + FB2 in unprocessed maize and 1 ppm in maize and maize-based products intended for human consumption (European Commission Regulation [EC], 2007). However, the legislation is distinct around the world, depending on the concern that the authorities have about the potential toxic effects of fumonisins on animals and their implications for industry (Food and Drug Administration [FDA], 2001; Schatzmayr and Streit, 2013).

Low levels of fumonisins can occur even in intact maize kernels, since F. verticillioides is found in both asymptomatic and diseased plants. Environmental conditions, water availability and the genetic background of the plant and the pathogen are significant factors in disease development and mycotoxin production (Oren et al., 2003; Bowers et al., 2013). It has been shown that physically injured kernels increase the propensity for fungal contamination and mycotoxin production (Munkvold et al., 1999; Parsons and Munkvold, 2012; Bowers et al., 2013). Kernel injuries caused by ear feeding insects are particularly important. These pests act as vectors for fungal spores, increasing the severity of fungal disease and mycotoxin production (Dowd, 2000; Wu, 2006; Ferreira-Castro et al., 2012).

The damage caused by European corn borer (ECB, Ostrinia nubialis Hübner), Southwestern corn borer (SWCB, Diatraea grandiosella Dyar), corn earworm (CEW, Helicoverpa zea Boddie) and fall armyworm (FAW, Spodoptera frugiperda, J.E. Smith) has been shown to favor mycotoxin contamination in the field and to contribute to mycotoxin accumulation during storage (Sinha, 1994; Dowd, 2000; Wu, 2006). Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) hybrids have been effective in reducing injuries by these insects, indirectly controlling plant susceptibility to fungal infection and mycotoxin contamination (Munkvold et al., 1997; Munkvold and Hellmich, 1999; Ostry et al., 2010; Bowers et al., 2013; Foresti et al., 2013)

It is widely known that Bt maize presents a lower risk of fumonisin contamination compared with non-Bt hybrids when exposed to lepidopteran insects (Duvick, 2001; Pazzi et al., 2006; Abbas et al., 2011; Bowers et al., 2013, 2014). A recent study has also demonstrated that Bt maize exhibited reduction in deoxynivalenol and zearalenone contamination in harvested maize kernels (Ostry et al., 2010). Although many studies have shown the relationship between kernel injuries by insects and fumonisin contamination in maize during harvest, none has focused on the fumonisin accumulation in Bt and non-Bt maize after this period.

The aim of this study was to verify the levels of fumonisins produced by F. verticillioides on Bt and non-Bt maize, post harvest, in different periods of incubation under controlled conditions. The second objective of this study was to compare FUM gene expression between Bt and non-Bt hybrids and to study the association between fumonisin production and FUM gene expression by F. verticillioides for each of the hybrids.

Materials and Methods

Maize Grain Samples

Maize cultivar samples of Bt 2B710 Hx and 30F35 YG and their isogenic non-Bt 2B710 and 30F35 were provided by the Agronomic Institute of Campinas (Instituto Agronômico de Campinas, APTA-São Paulo, Brazil). These samples were sown in November/2010 and harvested in March/2011 in Cruzália, State of São Paulo, Brazil.

Sampling was conducted according to methodology proposed by Delp et al. (1986) with modifications. Bt and non-Bt crop fields were sampled by dividing them into four sectors of uniform size containing eight rows each. Ten samples were randomly collected from each sector, for a total of 40 samples per hybrid. The hybrids were harvested manually in the experimental field by the technical support staff of the Agronomic Institute of Campinas. Thirty subsamples for each hybrid were then selected for this experiment, totalling 120 tests.

Ten samples of 30F35 YG (expressing Cry 1Ab protein, equivalent to MON810, Monsanto), 10 samples of 2B710 Hx (expressing Cry 1F protein, equivalent to TC1 507, Dow Agrosciences) corn grains and their respective isogenic hybrids were used for each incubation period (10, 20, and 30 days).

The injuries caused by S. frugiperda in 30F35 YG, 2B710 Hx and their isogenic hybrids were previously analyzed from sowing to harvest by The Agronomic Institute of Campinas in the same experimental field used in the current study (Michelotto et al., 2011).

All samples were sterilized by gamma radiation at a dose of 20 kGy to eliminate the natural mycoflora at the Nuclear and Energetic Research Institute (Instituto de Pesquisas Energéticas e Nucleares-IPEN-CNEN/SP). A GammaCell irradiator equipped with a cobalt 60 source was used and a dose rate ranging from 4.74 to 4.84 kGy/h was applied. The mycoflora was verified in order to control the irradiation procedure (Berjak, 1984). Samples were previously analyzed for the presence of fumonisins according to the methodology described by Visconti et al. (2001), because gamma radiation does not eliminate fumonisin from grains (Ferreira et al., 2007). The values (for each sample) were considered to be a basal FB1 or FB2 contamination, and were used to calculate the final fumonisin concentration produced by F. verticillioides after each period of incubation (total concentration minus basal concentration).

Fusarium verticillioides Strain

Fusarium verticillioides isolate 13BA was obtained from the culture collection of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences, ICBII, University of São Paulo, Brazil. The isolate was maintained on SNA (Spezieller Nährstoffarmer Agar) by monosporic isolation and it was used in all experiments (Rocha et al., 2011).

Before beginning the experiments, the ability of fumonisin production by F. verticillioides strain 13BA was re-evaluated according to methodology proposed by Ross et al. (1990) and Sydenham et al. (1990), with concentrations of 120and 36 μg/g for FB1 and FB2, respectively.

Inoculation of Corn Samples with Fusarium verticillioides Spore Suspension

The F. verticillioides fungal spore suspension was prepared according to Ferreira et al. (2007). The final suspension was adjusted to 5 × 105 spores/mL and inoculated into 5 g of maize bran (previously treated with 20 kGy gamma radiation). This mixture was added to Petri dishes containing 25 g of grains used for fumonisin and FUM gene cluster expression analyses. The samples were stored in a plastic container at a relative humidity and temperature controlled by a previously calibrated thermo hygrometer. The container was incubated in a BOD incubator at 25°C and a relative humidity of 97.5 to 99.0% obtained with 30% K2SO4 solution as described by Winston and Bates (1960) for 10, 20, and 30 days. After each incubation period, 10 samples of each hybrid were analyzed, with 20 g for fumonisin analyses and 5 g for gene expression experiments.

Determination of Fumonisins

Samples were prepared and extracted according to the methodology proposed by Visconti et al. (2001). Afterwards, fumonisins were mixed with the derivatizing agent ortho-phthaldehyde (OPA; Visconti et al., 2001) and injected into a Shimadzu liquid chromatograph (LC-10AD). Separation was performed on a C-18 reverse phase column (5 ODS-20, 150 mm × 4.6 mm; Phenomenex).

Fumonisins were quantified based on a calibration curve using standard solutions of FB1 and FB2 (Sigma–Aldrich). The coefficient of correlation was 0.993 for FB1 and 0.995 for FB2. The limit of quantification (LOQ) for FB1 was 0.015 μg/g, with a mean recovery of 92.38% and standard deviation of 13.68% (five replicates). For FB2, LOQ was 0.015 μg/g, with a mean recovery of 85.39% and standard deviation of 6.87% (five replicates). LOQ was determined via recovery tests. The lowest validated spike (0.015 μg/g) level with a percentage of recovery between 70 and 120% and a standard variation lower than 20% was defined as the method LOQ in this study (European Commission Regulation [EC], 2007).

The final fumonisin concentration was calculated through the subtraction of the total FB1 or FB2 for each analyzed sample (basal FB1 or FB2 concentration plus the concentration of FB1 or FB2 produced by F. verticillioides during the respective incubation periods) minus the basal FB1 or FB2 contamination of each sample that came from the field.

FUM Gene Cluster Expression

Isolation of mRNA and Reverse Transcription

RNA was extracted from 5 g of corn samples corresponding to each inoculation period (10, 20, and 30 days) using the Plant RNA Isolation Aid Kit (Ambion®, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) followed by purification utilizing RNAqueous Kit (Ambion®, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized in a Gene Amp® PCR System 9700 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies) for 1 h at 37°C. The samples were stored at -20°C.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

In this study, the following FUM genes were initially tested: FUM1, FUM2, FUM3, FUM6, FUM7, FUM8, FUM10 FUM13, FUM14, FUM15, FUM19, and FUM21. Primers were designed in the program Primer 31 from the reference sequences AF155773 (Proctor et al., 1999) and U27303/EU430619 (Yan and Dickman, 1996; Visentin et al., 2009) deposited at the National Centre for Biotechnology Information-NCBI2. FUM1, FUM19, and TUB primers were obtained from the study of Lopez-Errasquín et al. (2007; Table 1). The specificity of the primer sequences was verified through BLAST tool in NCBI.

Table 1.

qPCR primers used to evaluate FUM gene expression by Fusarium verticillioides in maize grains.

| Locus | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | Fragment size (bp) | Reference/NCBI accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

|

FUM1F FUM1R |

GAGCCGAGTCAGCAAGGATT AGGGTTCGTGAGCCAAGGA |

90 | Lopez-Errasquín et al., 2007 |

|

FUM3F FUM3R |

CTTGGCGGTGCCCATACTA GGACCAAGAGCGTGGATG |

60 | This study/AF155773 |

|

FUM6F FUM6R |

GATAGACTCGGGGCTGAGA AGCTCGCCGACAGAATC |

100 | This study/AF155773 |

|

FUM7F FUM7R |

CATCGTATCTACATTGTCGCATC TGTACTCTCCAACAATATGAATGAGTC |

100 | This study/AF155773 |

|

FUM8F FUM8R |

CAACAGAAATACGCAATGACG TGCTCGACCACTACATCAGG |

99 | This study/AF155773 |

|

FUM13F FUM13R |

GCCTTTGGTCTTGTTCTCTCA CGTCAATTATTGCCTCTTTCAA |

100 | This study/AF155773 |

|

FUM14F FUM14R |

TAGGTCCAGGTCGAGATGCT GGAAGCCAAGAACCCAATCT |

99 | This study/AF155773 |

|

FUM15F FUM15R |

TGCCATCCAGAATGACGATA GAGTCTCAGGAGAGCGAGGA |

94 | This study/AF155773 |

|

FUM19F FUM19R |

ATCAGCATCGGTAACGCTTATGA CGCTTGAAGAGCTCCTGGAT |

88 | Lopez-Errasquín et al., 2007 |

|

TUBF TUBR |

CCGGTATGGGTACTCTGCTC CTCAACGACGGTGTCAGAGA |

95 | Lopez-Errasquín et al., 2007 |

|

CALMF CALMR |

ACGGTTTCATTTCTGCTGCT TCAGCCTCTCGGATCATCTC |

97 | This study/AF155773 |

The Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG reagent (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) was used as the reaction mixture, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate. An appropriate negative control containing no template was used in all reactions to exclude possible contaminations. The quantification of mRNA was normalized using the average of TUB (β-tubulin) and CALM (calmodulin) genes (Bustin et al., 2009), with cDNA amplifications ran on the same plate. The following reference genes were tested prior to the experiments: CALM, TUB, EF-1α (elongation factor 1 α) and 18s rRNA (18s ribosomal RNA). The Ct values of TUB and CALM were similar; therefore, the mean values of these genes were used for normalizing the data.

Relative quantification based on ΔΔCt values was the method of analysis used in this study, since the efficiencies of compatibility tests between the average of the reference genes (TUB and CALM) and the target gene were similar, with slopes between -0.1 and 0.1 (Pfaffl, 2001; Gizinger, 2002; Schmittgen and Livak, 2008; Raymaekers et al., 2009).

For validation of the method, serial dilutions of the target genes and of the reference genes were prepared in triplicate. The primers’ efficiency was calculated based on the curve generated by the software. FUM2, FUM10, and FUM21 were excluded from the analysis since qPCR parameters were not acceptable according to the method of analysis proposed by Pfaffl (2001) and Schmittgen and Livak (2008).

Statistical Analysis

The results were analyzed using Gamlss R 2.9 package and Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) version 9.1. The Gamlss model (5% level of significance) with Weibull distribution was used to evaluate differences of FB1 and FB2 production between Bt and non-Bt maize during the period of incubation (10, 20, and 30 days; Rigby and Stasinopoulos, 2005). The Weibull distribution was chosen using quantile residual plots (Dunn and Smyth, 1996). The analysis was conducted based on the overall data (from the first to 30th day). The Gamlss model was used to verify the interaction between hybrids (Bt and non-Bt) and period of incubation (10, 20, and 30 days). As these interactions were not significant (P > 0.05), further analyses based on each period of incubation (10, 20, and 30 days) were not conducted.

The differences of FUM gene expression between Bt and non-Bt maize were evaluated using the Mann–Whitney test, since the data was not normally distributed (5% level of significance) for each period of incubation (Gibbons and Chakraborti, 2003). Pearson’s correlation tests were performed to investigate possible associations between the relative expression levels of FUM1, FUM3, FUM6, FUM7, FUM8, FUM13, FUM14, FUM15, and FUM19 and the production of FB1 and FB2 by F. verticillioides on Bt and non-Bt samples.

Results

Production of FB1 and FB2 in Bt and Non-Bt Maize Samples Artificially Contaminated with F. verticillioides During the Periods of 10, 20, and 30 days

FB1 and FB2 were quantified during 10, 20, and 30 days of incubation. The Bt hybrid 30F35 YG presented FB1 levels between 0.11 to 4.99 μg/g (mean: 2.38 μg/g) and FB2 from 0.02 to 2.66 μg/g (mean: 1.53 μg/g). 30F35 hybrid presented FB1 levels from 1.49 to 5.34 μg/g (mean: 3.17 μg/g) and FB2 from 0.015 to 2.83 μg/g (mean: 1.7 μg/g) (Table 2). Statistical analysis showed that FB1 contamination was significantly lower in 30F35YG when compared to its isogenic hybrid 30F35 (P = 0.0095). However, there was no statistical difference between Bt and non-Bt maize samples for FB2 production (P = 0.827). Interaction between hybrids (Bt and non-Bt) and period of incubation (10, 20, and 30 days) was not significant (P > 0.05), therefore there was no evidence that the mean difference of FB1 (P = 0.26) and FB2 (P = 0.82) production between Bt and non-Bt maize changed over the period of incubation.

Table 2.

Fumonisin production by F. verticillioides in 30 maize samples of 30F35 YG, 2B710 Hx (Bt), 30F35 and 2B710 (non-Bt hybrids) during 10, 20, and 30 days of incubation under temperature of 25°C and humidity of 97.5 to 99.0%.

| Period of Incubation | Samples | 30F35 YG (Bt) |

30F35 (non-Bt) |

2B710 Hx (Bt) |

2B710 (non-Bt) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FB1 (μg/g) | FB2 (μg/g) | FB1 (μg/g) | FB2 (μg/g) | FB1 (μg/g) | FB2 (μg/g) | FB1 (μg/g) | FB2 (μg/g) | ||

| 10 days | 1 | 2,92b | 2,26 | 3,14 | 2,66 | 7,65 | 3,50 | 8,05 | 4,59 |

| 2 | 2,91 | 2,60b | 3,78 | 2,83b | 6,72 | 2,61 | 10,90 | 5,68 | |

| 3 | 0,99 | 0,52 | 1,58 | 0,63 | 7,52 | 3,48 | 9,36 | 5,15 | |

| 4 | 1,99 | 0,60 | 2,07 | 0,41a | 0,19a | 0,02a | 7,92 | 3,68 | |

| 5 | 1,29 | 2,54 | 4,64b | 2,29 | 8,15 | 3,83 | 6,95 | 3,56 | |

| 6 | 0,32a | 0,61 | 2,06 | 0,78 | 6,01 | 6,03 | 8,98 | 2,59 | |

| 7 | 0,84 | 0,37a | 3,51 | 1,77 | 3,58 | 1,28 | 6,13 | 3,11 | |

| 8 | 2,02 | 0,57 | 4,19 | 2,21 | 7,70 | 5,68 | 4,46a | 2,89 | |

| 9 | 1,24 | 0,49 | 1,49a | 0,53 | 4,34 | 3,64 | 4,90 | 0,80a | |

| 10 | 2,64 | 2,29 | 2,71 | 2,30 | 8,24b | 6,75b | 11,03b | 8,31b | |

| Mean | c1.72 ± 0.29∗ | 1.29 ± 0.31 | d2.92 ± 0.35 | 1.64 ± 0.30 | e6.01 ± 0.82 | 3.68 ± 0.66 | f7.87 ± 0.72 | 4.04 ± 0.65 | |

| 20 days | 11 | 2,71 | 1,96 | 2,86 | 1,99 | 8,74 | 6,56 | 9,57 | 5,42 |

| 12 | 4,99b | 1,64 | 5,11b | 1,64 | 7,26 | 5,89 | 10,34 | 5,87 | |

| 13 | 4,31 | 2,66b | 4,42 | 2,66b | 8,49 | 3,02 | 9,16 | 4,36 | |

| 14 | 3,47 | 2,01 | 3,76 | 2,03 | 7,24 | 3,68 | 10,97b | 6,58b | |

| 15 | 3,62 | 1,03 | 4,09 | 1,07 | 5,72 | 2,95 | 7,52 | 5,46 | |

| 16 | 3,48 | 1,40 | 3,65 | 1,41 | 6,11 | 2,24a | 5,05a | 2,46a | |

| 17 | 1,00 | 1,66 | 3,12 | 2,05 | 7,90 | 6,10 | 10,16 | 5,88 | |

| 18 | 3,03 | 2,27 | 3,16 | 2,27 | 4,97a | 3,05 | 6,83 | 3,45 | |

| 19 | 0,41a | 1,17 | 2,15 | 1,67 | 9,00b | 6,72b | 10,47 | 5,22 | |

| 20 | 1,00 | 0,02a | 1,84a | 0,015a | 5,64 | 3,98 | 7,37 | 4,45 | |

| Mean | c2.8 ± 0.48 | 1.58 ± 0.23 | d3.42 ± 0.32 | 1.68 ± 0.23 | e7.11 ± 0.45 | 4.42 ± 054 | f8.74 ± 0.61 | 4.92 ± 0.39 | |

| 30 days | 21 | 2,87 | 1,55 | 2,96 | 1,55 | 4,43 | 3,64 | 9,24 | 7,45 |

| 22 | 0,11a | 1,60 | 2,55 | 1,61 | 5,55 | 2,42 | 9,00 | 6,32 | |

| 23 | 2,30 | 0,91a | 2,45a | 0,92a | 5,56 | 1,55 | 9,43 | 7,90b | |

| 24 | 2,89 | 2,17b | 2,98 | 2,17 | 3,44 | 2,76 | 3,33a | 0,98a | |

| 25 | 2,83 | 1,88 | 2,90 | 1,88 | 8,43 | 4,95 | 11,55b | 7,47 | |

| 26 | 2,71 | 1,86 | 2,82 | 1,87 | 9,47 | 5,49 | 9,70 | 3,35 | |

| 27 | 3,72b | 2,06 | 4,01 | 2,08 | 9,71b | 6,62 | 7,86 | 3,62 | |

| 28 | 2,38 | 1,51 | 2,64 | 1,51 | 3,72 | 2,92 | 9,61 | 5,21 | |

| 29 | 2,96 | 1,83 | 3,15 | 1,83 | 2,59a | 1,50a | 8,22 | 2,56 | |

| 30 | 3,49 | 1,70 | 5,34b | 2,28b | 8,63 | 6,64b | 10,73 | 5,66 | |

| Mean | c2.63 ± 0.31 | 1.71 ± 0.11 | d3.18 ± 0.28 | 1.77 ± 0.12 | e6.15 ± 0.85 | 3.85 ± 0.62 | f8.87 ± 0.70 | 5.05 ± 0.74 | |

| Mean/total | c2,38 ± 0.22 | 1,53 ± 0.13 | d3,17 ± 0.18 | 1,7 ± 0.13 | e6.58 ± 0.41 | 3.98 ± 0.36 | f8.68 ± 0.31 | 4.67 ± 0.35 | |

Fumonisin levels were calculated as described in section “Materials and Methods.”

aMinimum fumonisin level for each 10, 20, and 30 days; bMaximum fumonisin level for each 10, 20, and 30 days; ∗Mean ± standard error; c,dDifferences of FB1 production in 30F35 YG and 30F35, respectively (P < 0.05); e,fDifferences of FB1 production in 2B710 Hx and 2B710, respectively (P < 0.05).

2B710 Hx presented levels of FB1 and FB2 between 0.19–9.71 μg/g (mean: 6.42 μg/g) and 0.02–6.75 μg/g (mean: 3.98 μg/g), respectively. The isogenic 2B710 hybrid presented FB1 levels from 3.33–11.55 μg/g (mean: 8.49 μg/g) and FB2 from 0.8 to 8.31 μg/g (mean: 4.67 μg/g) (Table 2). FB1 contamination was significantly lower in 2B710Hx when compared to its isogenic hybrid 2B710 (P = 0.0001). There was no statistical difference between Bt and non-Bt maize samples for FB2 production (P = 0.382). There was no evidence that the mean difference of FB1 (P = 0.95) and FB2 (P = 0.61) production between Bt and non-Bt maize changed over the period of incubation.

Optimization of qPCR Reactions and FUM Gene Expression in Bt and Non-Bt Maize Samples Artificially Contaminated with F. verticillioides During the Periods of 10, 20, and 30 days

The comparative ΔΔCt method was chosen for FUM gene expression analysis, since qPCR efficiencies were similar. ΔΔCt relative quantification is used to compare the gene expression between one sample and another (control). In this study, the control was considered the samples with the lowest Ct value for all of the genes for each hybrid (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

The efficiencies (E) obtained in the qPCR analysis were between 78 and 110% for all of the studied genes, with slopes between -4 (FUM21) and -3.1 (FUM8, FUM14, FUM15) and r2 from 0.97 (FUM2, FUM6, FUM10) to 0.99 (all the other genes; Supplementary Figure S1). According to the European Network of GMO Laboratories, acceptable slopes for standard curve range from -3.1 to -3.6. In this study, FUM2, FUM10, and FUM21 presented values outside this range (European Network of Gmo Laboratories [ENGL], 2008). The melt-curve analysis resulted in one single peak for all of the genes used in the analysis (Supplementary Figure S1).

The average between the Ct values of the reference genes β-tubulin (TUB) and CALM were selected to normalize the Ct values of the samples. The average of CALM and TUB showed better repeatability and less variability in Ct values when compared to other tested genes (EF- 1α and 18s rRNA). The ΔCt values were plotted against the log dilutions, and the slopes ranged from -0.24 (FUM21 in relation to TUB and CALM) to 0.02 (FUM 1 in relation to TUB and CALM). FUM2, FUM10, and FUM21 reactions did not present acceptable validation parameters once slope values for compatibility tests were not within -0.1 and 0.1; therefore they were excluded from the analysis. Even though r2 for FUM6 was below 0.99, this gene was not excluded from the analyses, since efficiency and slope values were satisfactory.

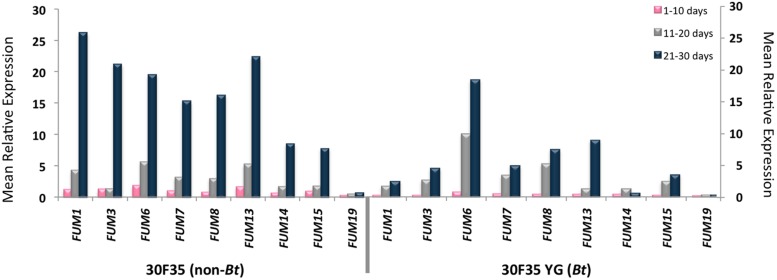

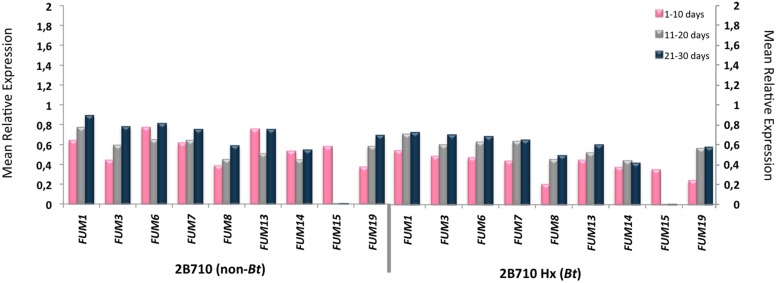

Amplification of the FUM genes was observed in all of the samples. Statistical analysis showed that there was an indication of higher FUM1 expression during the three periods of incubation (P < 0.02), higher FUM13 expression during the 10th day of incubation and higher FUM7, FUM8, and FUM14 expressions during the 30th day of incubation (P < 0.04) and higher levels of FUM19 expression in the 20 and 30th days of incubation (P < 0.04) in the non-Bt 30F35 hybrid. There was an indication of higher FUM19 expression during the 10th day of incubation in the non-Bt 2B710 hybrid (P < 0.03).

There was a weak correlation between FB1 production and the expression of FUM1 (P = 0.009, r = 0.47), FUM7 (P = 0.017, r = 0.43), FUM8 (P = 0.024, r = 0.41), FUM13 (P = 0.032, r = 0.39), FUM14 (P = 0.001, r = 0.57), FUM15 (P = 0.011, r = 0.46), and FUM19 (P = 0.009, r = 0.47) in corn samples of 30F35 YG hybrid at a 5% significance level. For this hybrid, FUM19 was also slightly correlated to FB2 production (P = 0.049, r = 0.36). However, there is no evidence of correlation between FB1 and FB2 production and the studied FUM genes for the hybrids 30F35, 2B710, and 2B710 Hx (Figures 1 and 2).

FIGURE 1.

Mean relative expression of FUM1, FUM3, FUM6, FUM7, FUM8, FUM13, FUM14, FUM15, and FUM19 in 30F35 and 30F35 YG hybrids during 30 days of incubation.

FIGURE 2.

Mean relative expression of FUM1, FUM3, FUM6, FUM7, FUM8, FUM13, FUM14, FUM15, and FUM19 in 2B710 and 2B710 Hx hybrids during 30 days of incubation.

Discussion

Samples representing the non-Bt hybrids 2B710 and 30F35 that came from the field presented damaged kernels as a result of insect injuries, which could possibly facilitate fungal penetration and consequently fumonisin production. 2B710 Hx and 30F35 YG samples were virtually intact (Michelotto et al., 2011). It has been shown that wounded plants and seeds facilitate fungal contamination, increasing the chance of diseases and mycotoxin production (Wallin, 1986; Gradziel and Wang, 1994; Mahoney and Rodrigues, 1996; Imathiu et al., 2008; Mohammadi and Hokmabadi, 2010).

The Bt hybrids 30F35 YG and 2B710 Hx were chosen due to their worldwide utilization for controlling insect pests. 30F35 YG expresses cry1Ab, an efficient protein for reducing injuries from lepidopteran pests’ feeding (Bowers et al., 2014). Although cry1Ab is not highly effective against CEW (Bowers et al., 2013) and FAW, important lepidopteran insects found in Brazil (Farias et al., 2014), this protein has demonstrated efficacy in preventing insect injuries and therefore aiding in the reduction of fungal contamination and mycotoxin production (Munkvold, 2003; Ostry et al., 2010; Leslie and Logrieco, 2014).

2B710 Hx expresses cry1F protein, and it has been shown to be ineffective against CEW (Bowers et al., 2013), however, hybrids expressing this protein have demonstrated temporary efficacy in controlling FAW in Brazil, since cry1F resistant populations of S. frugiperda have emerged from maize field where cry1F protein has been extensively used (Farias et al., 2014). This insect is native to the tropical regions of the western hemisphere from the United States to Argentina. The larvae feed primarily on maize leaf tissue, causing extensive defoliation (Farias et al., 2014); in addition, S. frugiperda can migrate to corn ear, causing damage to kernels (Gorman and Kang, 1991), creating infection sites for toxigenic fungi, such as Fusarium and Aspergillus (Munkvold, 2003, 2014).

Complementary research conducted by Michelotto et al. (2011), using the field and maize samples corresponding to those used in this study, has demonstrated that the damage caused by S. frugiperda was significantly lower in 30F35 YG and 2B710 Hx when compared to their respective isogenic hybrids from sowing to harvest. This may explain the pattern of fumonisin production in the samples under controlled conditions, since damaged kernels can promote F. verticillioides invasion and therefore facilitate fumonisin production in non-Bt maize. In fact, insects are able to cause injuries to the external protection of grains and plant tissues in the field, allowing the fungal hyphae to readily penetrate, have access to nutrients and produce mycotoxins (Wu et al., 2004; Wu, 2006; Jouany, 2007). Since Bt maize reduces insect damage and the risk of fungal contamination, it could indirectly control mycotoxin accumulation during storage. However, it is important to emphasize that a deeper investigation regarding the differences between Bt and non-Bt maize in F. verticillioides contamination and fumonisin production as well as the use of different cry proteins to effectively control insect pests are warranted to aid in the management strategies and to better understand the correlation between insect pest control and fungal invasion/mycotoxin production in maize.

The current study also compared the fumonisin production by F. verticillioides with FUM1, FUM3, FUM6, FUM7, FUM8, FUM13, FUM14, FUM15, and FUM19 gene expression for each of the studied hybrids, and also compared the FUM gene expression between Bt and non-Bt hybrids.

FUM genes were expressed by F. verticillioides in all of the corn samples, with an indication of lower gene expression for some of the studied genes in the Bt hybrids. There was a weak correlation between FB1 and FB2 production and the relative expression of some of the studied FUM genes were observed in 30F35 YG. Among these genes, FUM1, FUM14, and FUM19 were better correlated with fumonisin production. Interestingly, it was observed differences in the expression of these same genes in Bt and non-Bt hybrids.

Studies have shown a correlation between some of the FUM genes and fumonisin production (Lopez-Errasquín et al., 2007; Jurado et al., 2010; Rocha et al., 2011; Lazzaro et al., 2012; Medina et al., 2013). FUM19 encodes a protein that is highly similar to the ATP-binding cassette of multidrug resistance transporters, which act as efflux pumps to reduce cellular concentrations of toxins and thereby confer protection (Desjardins, 2006). Although Lopez-Errasquín et al. (2007), Jurado et al. (2010) and Rocha et al. (2011), have found a positive correlation between FUM19 and fumonisin production, our results have shown a weak association between this gene expression and fumonisin production in 30F35 YG hybrid. FUM14 also had a weak association with fumonisin production; this gene encodes a protein involved in the formation of tricarballylic ester function. Indeed, a previous study has demonstrated that FUM14, as well as FUM1 and FUM19 exhibit a significant effect on the synthesis of FB1 and FB2 (Medina et al., 2013). Further studies regarding the expression of these genes should be conducted to verify whether or not they could be useful for diagnostics.

It is relevant to emphasize that previous studies have used synthetic media to produce fumonisins and analyze FUM gene expression (Lopez-Errasquín et al., 2007; Jurado et al., 2010; Rocha et al., 2011; Lazzaro et al., 2012; Medina et al., 2013), which increases the quality and concentration of RNA. Fungal RNA extraction from maize can be limited, once kernel consists of 90% starch and 10% proteins (Gibbon and Larkins, 2005). Even though the experimental Petri dishes containing maize grains were covered in F. verticillioides mycelium, the final RNA consisted of plant and fungal RNA, which likely decreased the performance of qPCR reactions, thereby interfering in the correlation between FUM gene cluster and fumonisin production. The rationale for isolating fungal RNA from maize grains is due to the fact that F. verticillioides can persist in undamaged plants and produce fumonisins; thus, identifying an adequate genetic marker for assessing fumonisin production during interaction between F. verticillioides and symptomless plants could aid in the prevention of fumonisin accumulation in the field and storage (Presello et al., 2007; Duncan and Howard, 2010; Bowers et al., 2013).

Conclusion

Non-Bt maize samples 30F35 and 2B710 presented damaged kernels caused by insects in the field. In this study, wounded grains have possibly facilitated F. verticillioides penetration, leading to higher fumonisin production in non-Bt hybrids during the period of incubation due to the increase of fungal biomass. Insects cause physical damage, disruption of nutrients and grain injuries to several crops. Management of insects through the use of Bt maize can greatly reduce insect damage, thus indirectly controlling fungal and mycotoxin contamination in the field and the accumulation of mycotoxins during storage. Despite the known effect of Bt maize on fumonisin content in the field, due to the control of insect pests, there is a lack of information regarding the accumulation of mycotoxins in Bt maize during a post-harvest period. Highlighting that, further investigations using different Bt hybrids could possibly aid in the controlling strategies. The gene expression analyses demonstrated that further studies should be conducted to determine an acceptable qualitative genetic marker for identifying fumonisin production in early stages of infection by F. verticillioides in maize.

Author Contributions

LR, BC, and AD conceived the study. AD and MM provided the maize samples. MM performed field sampling and initial tests for grain damage. VB and LA conducted fumonisin analysis. FF-C conducted gene expression tests. GP performed statistical analyses. LR and GP analyzed the overall data for the manuscript. LR wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo) for providing financial support. We also thank the group of Instituto Agronômico de Campinas, Cruzália - SP for technical assistance and suggestions during field sampling. We are grateful to Tatiana Alves dos Reis and Sabina Moser Tralamazza for technical assistance with HPLC method validation and gene expression analysis, respectively.

Funding. This research was funded by FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01503

Optimization of qPCR reactions. (A) FUM1, (B) FUM3, (C) FUM6, (D) FUM7, (E) FUM8, (F) FUM13, (G) FUM14, (H) FUM15, and (i) FUM19 and reference genes [(J) TUB and (K) CALM]. Melt- curve, slope, r2, and efficiency results for each of the studied genes. Curves were generated by four dilutions of total fungal RNA (10-fold dilutions for each point of the curve) extracted from maize grains contaminated with Fusarium verticillioides mycelium. Five replicates were tested for each dilution, and the slope, r2 and efficiencies were calculated.

References

- Abbas H. K., Shier W. T., Cartwright R. D. (2011). Effect of temperature, rainfall and planting date on aflatoxin and fumonisin contamination in commercial Bt and non-Bt corn hybrids. Phytoprotection 88 41–50. 10.7202/018054ar [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berjak P. (1984). Report of seed storage committee working group on the effects of storage fungi on seed viability. Seed Sci. Technol. 12 233–253. [Google Scholar]

- Bojja R. S., Cerny R. L., Proctor R. H., Liangcheng D. (2004). Determining the biosynthetic sequence in the early steps of the fumonisin pathway by use of three gene-disruption mutants of Fusarium verticillioides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52 2855–2860. 10.1021/jf035429z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers E. L., Hellmich R. L., Munkvold G. P. (2013). Vip3Aa and Cry1Ab proteins in maize reduce Fusarium ear rot and fumonisins by deterring kernel injury from multiple Lepidopteran pests. World Mycotoxin J. 6 127–135. 10.3920/WMJ2012.1510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers E. L., Hellmich R. L., Munkvold G. P. (2014). Comparison of fumonisin contamination using HPLC and ELISA methods in Bt and near-isogenic maize hybrids infested with european corn borer or western bean cutworm. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62 6463–6472. 10.1021/jf5011897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. W., Butchko R. A. E., Busman M., Proctor R. H. (2007). The Fusarium verticillioides FUM gene cluster encodes a Zn(II)2Cys6 protein that affects FUM gene expression and fumonisin production. Eukaryot. Cell 6 1210–1218. 10.1128/EC.00400-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin S. A., Benes V., Garson J. A., Hellemans J., Huggett J., Kubista M., et al. (2009). The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 55 611–622. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Campa R., Hooker D. C., Miller J. D., Schaafsma A. W., Hammond B. G. (2005). Modeling effects of environment, insect damage, and Bt genotypes on fumonisin accumulation in maize in Argentina and the Philippines. Mycopathologia 159 539–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delp R. B., Stewell L. J., Marois J. J. (1986). Evaluation of field sampling techniques for estimation of disease incidence. Phytopathology 76 1299–1305. 10.1094/Phyto-76-1299 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins A. E. (2006). Fusarium Mycotoxins. Chemistry, Genetics and Biology. St Paul, MN: APS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dowd P. F. (2000). Indirect reduction of ear molds and associated mycotoxins in Bacillus thuringiensis corn under controlled and open field conditions: utility and limitations. J. Econ. Entomol. 93 1669–1679. 10.1603/0022-0493-93.6.1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan K. E., Howard R. J. (2010). Biology of maize kernel infection by Fusarium verticillioides. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23 6–16. 10.1094/MPMI-23-1-0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn P. K., Smyth G. K. (1996). Randomized quantile residuals. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 5 236–244. 10.1080/10618600.1996.10474708 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duvick J. (2001). Prospects for reducing fumonisin contamination of maize through genetic modification. Environ. Health Perspect. 109 337–342. 10.1289/ehp.01109s2337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Regulation [EC] (2007). No. 1126/2007 of 28 september 2007 amending regulation (EC) No. 1881/2006. setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs as regards fusarium toxins in maize and maize products. J. Eur. Union 255 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Regulation [EC] (2013). No. 12571/2013 of 19 of November 2013. Guidance Document on Analytical Quality Control and Validation Procedures for Pesticide Residues Analysis in Food and Feed. Brussels: European Commission, Health and Consumer Protection Directorate-General. [Google Scholar]

- European Network of Gmo Laboratories [ENGL] (2008). Definition of Minimum Performance Requirements for Analytical Methods of GMO Testing. Available at: http://gmo-crl.jrc.ec.europa.eu [Google Scholar]

- Farias J. R., Andow D. A., Horikoshi R. J., Sorgatto R. J., Fresia P., dos Santos A. C., et al. (2014). Field– evolved resistance to Cry1F maize by Sporodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Brazil. Crop Prot. 64 150–158. 10.1603/EC14190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira F. L., Aquino S., Ribeiro D. H. B., Correa B. (2007). Effects of gamma radiation on maize samples contaminated with Fusarium verticillioides. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 65 927–933. 10.1016/j.apradiso.2007.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Castro F. L., Potenza M. R., Rocha L. O., Correa B. (2012). Interaction between toxigenic fungi and weevils in corn grain samples. Food Control 26 594–600. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.02.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration [FDA] (2001). Background Paper in Support of Fumonisin Levels in Corn and Corn Products Intended for Human Consumption. College Park, MD: US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. [Google Scholar]

- Foresti J., Bernardi O., Zart M., Garcia M. S. (2013). Oviposition behavior of Helicoverpa zea (Boddie, 1850) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in corn seed and simulation of control. Rev. Bras. Milho Sorgo 12 78–84. 10.18512/1980-6477/rbms.v12n1p78-84 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon B. C., Larkins B. A. (2005). Molecular genetic approaches to developing quality protein maize. Trends Genet. 21 227–233. 10.1016/j.tig.2005.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons J. D., Chakraborti S. (2003). Nonparametric Statistical Inference. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker. [Google Scholar]

- Gizinger D. G. (2002). Gene quantification using real-time quantitative PCR: an emerging technology hits the mainstream. Exp. Hematol. 30 503–512. 10.1016/S0301-472X(02)00806-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman D. P., Kang M. S. (1991). Preharvest aflatoxin contamination in maize: resistance and genetics. Plant Breed. 107 1–10. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.1991.tb00522.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gradziel T. M., Wang D. (1994). Susceptibility of California almond cultivars to aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus. HortScience 29 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Imathiu S. M., Ray R. V., Back M., Hare M. C., Edwards S. G. (2008). Fusarium langsethiae pathogenicity and aggressiviness towards oats and wheat in wounded and unwounded in vitro detached leaf assays. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 124 117–126. 10.1007/s10658-008-9398-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jouany J. P. (2007). Methods for preventing decontamination and minimizing the toxicity of mycotoxins in feeds. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 137 342–362. 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2007.06.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jurado M., Marín P., Calleja C., Moretti A., Vázquez C., González-Jaén M. T. (2010). Genetic variability and fumonisin production by Fusarium proliferatum. Food Microbiol. 27 50–57. 10.1016/j.fm.2009.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro I., Susca A., Mulè G., Ritieni A., Ferracane R., Marocco A., et al. (2012). Effects of temperature and water activity on FUM2 and FUM21 gene expression and fumonisin B1 production in Fusarium verticillioides. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 134 685–695. 10.1007/s10658-012-0045-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie K. F., Logrieco A. (2014). Mycotoxn Reduction in Grain Chains. Iowa City, IA: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Errasquín E., Vazquez C., Jimenez M., Gonzalez-Jaen M. T. (2007). Real-Time RT-PCR assay to quantify the expression of FUM1 and FUM19 genes from the fumonisin-producing Fusarium verticillioides. J. Microbiol. Methods 68 312–317. 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney M. E., Rodrigues S. B. (1996). Aflatoxin variability in pistachios. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62 1197–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marasas W. F. O., Riley R. T., Hendricks K. A., Stevens V. L., Sadler T. W., Gelineau-Van Waes J., et al. (2004). Fumonisins disrupt sphingolipid metabolismo, folato transport, and neural tube development in embryo culture and in vivo: a potential risk fator for human neural tube defects among populations consuming fumonisin- contaminated maize. J. Nutr. 134 711–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina A., Magan N. (2010). Comparisons of water activity and temperature impacts on growth of Fusarium langsethiae strains from northern Europe on oat-base media. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 142 365–369. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina A., Schmidt-Heydt M., Cárdenas-Chávez L., Parra R., Geisen R., Magan N. (2013). Integrating toxin gene expression, growth and fumonisin B1and B2 production by a strain of Fusarium verticillioides under different environmental factors. J. R. Soc. Interface 10 1–12. 10.1098/rsif.2013.0320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelotto M. D., Pereira A. D., Finoto E. L., Freitas R. S. (2011). Controle de pragas em híbridos de milho geneticamente modificados. Grandes Cult. 145 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi M. M., Hokmabadi H. (2010). Study on the effect of pistachio testa on the reduction of Aspergillus flavus growth and aflatoxin B1 production in kernels of different pistachio cultivars. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 4 744–749. [Google Scholar]

- Munkvold G. P. (2003). Cultural and genetic approaches to managing mycotoxins in maize. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 41 99–116. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.41.052002.095510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkvold G. P. (2014). “Crop management practices to minimize the risk of mycotoxins contamination in temperate-zone maize,” in Mycotoxin Reduction in Grain Chains, eds Leslie J. F., Logrieco A. (Iowa City, IA: Willey Blackwell; ), 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Munkvold G. P., Hellmich R. L. (1999). Comparison of fumonisin concentrations in kernels of transgenic Bt maize hybrids and nontransgenic hybrids. Plant Dis. 83 130–138. 10.1007/BF03036703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkvold G. P., Hellmich R. L., Rice L. G. (1999). Comparison of fumonisin concentrations in kernels of transgenic Bt maize hybrids and non-transgenic hybrids. Plant Dis. 83 130–138. 10.1094/PDIS.1999.83.2.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkvold G. P., Hellmich R. L., Showers W. B. (1997). Reduced Fusarium ear rot and symptomless infection in kernels of maize genetically engineered for European corn borer resistance. Phytopathology 87 1071–1077. 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.10.1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren L., Ezrati S., Cohen D., Sharon A. (2003). Early events in the Fusarium verticillioides –maize interaction characterized by using a green fluorescent protein-expressing transgenic isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69 1695–1701. 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1695-1701.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostry V., Ovesna J., Skarkova J., Pouchova V., Ruprich J. (2010). A review on comparative data concerning Fusarium mycotoxins in Bt maize and non-Bt isogenic maize. Mycotoxin Res. 26 141–145. 10.1007/s12550-010-0056-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons M. W., Munkvold G. P. (2012). Effects of planting date and environmental factors on Fusarium ear rot symptoms and fumonisin B1 accumulation in maize grown in six North American locations. Plant Pathol. 61 1130–1142. 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2011.02590.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pazzi F., Lener M., Colombo L., Monastra G. (2006). Bt maize and mycotoxins: the current state of research. Ann. Microbiol. 56 223–230. 10.1007/BF03175009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. W. (2001). A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 2002–2007. 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presello D. A., Iglesias J., Botta G., Eyhérabide G. H. (2007). Severity of Fusarium ear rot and concentration of fumonisin in grain of Argentinian maize hybrids. Crop Prot. 26 852–855. 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.3.251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor R. H., Brown D. W., Plattner R. D., Desjardins A. E. (2003). Co-expression of 15 contiguous genes delineates a fumonisin biosynthetic gene cluster in Gibberella moniliformis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 38 237–249. 10.1016/S1087-1845(02)00525-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor R. H., Desjardins A. E., Plattner R. D., Hohn T. M. (1999). A poly– ketide synthase gene required for biosynthesis of fumonisin mycotoxins in Gibberella fujikuroi mating population A. Fungal Genet. Biol. 7 100–112. 10.1006/fgbi.1999.1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor R. H., Van Hove F., Susca A., Stea G., Busman M., Van der Lee T., et al. (2013). Birth, death and horizontal gene transfer of the fumonisin byosinthetic gene cluster during the evolutionary diversification of Fusarium. Mol. Microbiol. 90 290–306. 10.1111/mmi.12362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymaekers M., Smets R., Maes B., Cartuyvels R. (2009). Checklist for optimization and validation of real-time PCR assays. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 23 145–151. 10.1002/jcla.20307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby R. A., Stasinopoulos D. M. (2005). Generalized additive models for location, scale and shape. J. R. Stat. Soc. C Appl. Stat. 54 507–554. 10.1111/j.1467-9876.2005.00510.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha L. O., Reis G. M., da Silva V. N., Braghini R., Teixeira M. M. G., Corrêa B. (2011). Molecular characterization and fumonisin production by Fusarium verticillioides isolated from corn grains of different geographic origins in Brazil. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 145 9–21. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross P. F., Nelson P. E., Richard J. L., Plattner R. D., Rice L. G., Osweiller G. D., et al. (1990). Production of fumonisin by Fusarium verticillioides and Fusarium proliferatum isolates associated with equine leukoencephalomalacia and pulmonary oedema syndrome swine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56 3224–3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzmayr G., Streit E. (2013). Global occurrence of mycotoxins in the food and feed chain: facts and figures. World Mycotoxin J. 6 213–222. 10.3920/WMJ2013.1572 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen T. D., Livak K. J. (2008). Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative Ct method. Nat. Protoc. 3 1101–1108. 10.1038/nprot.2008.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha A. K. (1994). “The impact of insect pests on aflatoxin contamination of stored wheat and maize,” in Proceedings of the 6th International Working Conference on Stored-Product Protection, eds Highley E., Wright E. J., Banks H. J., Champ B. R. (Wallingford: CAB International; ), 1059–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Stepien L., Koczyk G., Waskiewicz A. (2011). Genetic and phenotypic variation of Fusarium proliferatum isolates from different host species. J. Appl. Genet. 52 487–496. 10.1007/s13353-011-0059-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sydenham E. W., Thiel P. G., Marasas W. F. O., Shephard G. S., Schalkwyk D. J., Koch K. R. (1990). Natural occurrence of some Fusarium mycotoxins in corn from low and high esophageal cancer prevalence areas of the Transkei, Southern Africa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 38 1900–1903. 10.1021/jf00100a004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture [USDA] (2014). World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates. Available at: www.usda.gov/oce/commodity/wasde/latest.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Visconti A., Solfrizzo M., Girolamo A. (2001). Determination of fumonisins B1 and B2 in corn and corn flakes by liquid chromatography with immunoaffinity column cleanup: collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 84 1828–1837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visentin I., Tamietti G., Valentino D., Portis E., Karlovsky P., Moretti A., et al. (2009). The ITS region as a taxonomic discriminator between Fusarium verticillioides and Fusarium proliferatum. Mycol. Res. 113 1137–1145. 10.1016/j.mycres.2009.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin J. R. (1986). Production of aflatoxin in wounded and whole maize kernels by Aspergillus flavus. Plant Dis. 70 429–430. 10.1094/PD-70-429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winston P. W., Bates D. H. (1960). Saturated solutions for the control of humidity in biological research. Ecology 41 232–236. 10.2307/1931961 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F. (2006). Mycotoxin reduction in Bt corn: potential economic, health, and regulatory impacts. Transgenic Res. 15 277–289. 10.1007/s11248-005-5237-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Miller J. D., Casman E. A. (2004). Bt corn and mycotoxin reduction: economic impacts in the United States and the developing world. J. Toxicol. Toxin Rev. 23 397–424. 10.1081/TXR-200027872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan K., Dickman M. B. (1996). Isolation of a 3-tubulin gene from Fusarium moniliforme that confers cold-sensitive benomyl resistance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62 3053–3056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Optimization of qPCR reactions. (A) FUM1, (B) FUM3, (C) FUM6, (D) FUM7, (E) FUM8, (F) FUM13, (G) FUM14, (H) FUM15, and (i) FUM19 and reference genes [(J) TUB and (K) CALM]. Melt- curve, slope, r2, and efficiency results for each of the studied genes. Curves were generated by four dilutions of total fungal RNA (10-fold dilutions for each point of the curve) extracted from maize grains contaminated with Fusarium verticillioides mycelium. Five replicates were tested for each dilution, and the slope, r2 and efficiencies were calculated.