Abstract

Nephrologists play an important role in providing medical education in a variety of settings, including the medical school classroom, nephrology consult service, outpatient clinic, and dialysis unit. Therefore, nephrologists interact with a variety of learners. In this article the current state of published literature in medical education in nephrology is reviewed. Eight attending roles are identified of the nephrologist as a medical educator in the academic settings: inpatient internal medicine service, nephrology inpatient consult service, inpatient ESRD service, outpatient nephrology clinic, kidney transplantation, dialysis unit, classroom teacher, and research mentor. Defining each of these distinct settings could help to promote positive faculty development and encourage more rigorous education scholarship in nephrology.

Keywords: nephropathy, ESRD, transplantation

Introduction

Many nephrologists supervise, instruct, and inspire physician trainees across the medical education spectrum. From the classroom in medical school to the nephrology consult service, nephrologists have major roles in teaching medical students, residents, and fellows in training. In these various roles, nephrologists are often recognized as excellent teachers and mentors (1). Despite these laudable qualities, research in nephrology education is lacking (2). Although education research in nephrology has gained some ground in the last 5 years, the publication of high-quality studies in this area remains suboptimal. In fact, most published studies report survey results of learners and faculty perceptions, providing low levels of evidence to guide educational innovation and improvement (2).

An understanding of educational research methodology is important for clinicians and nephrologists involved in undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate medical education. The field of medical education has progressed significantly in the last two decades; however, medical education research in nephrology has been slow to adapt to changes (2).

To examine some of these concerns, we define the various teaching roles of nephrologists in the academic settings to provide a foundation for exploring future research avenues. The current literature of medical education in nephrology is reviewed to establish where research deficits exist in each of the eight roles for the nephrologist educator. Examples from other academic specialties and subspecialties that have performed rigorous medical education research are also reported. We then explore the rigor and steps required to help move the field of nephrology forward in the arena of educational scholarship. The challenges and opportunities that nephrologist educators face when teaching medical students, medical residents, and nephrology fellows are considered. Finally, we propose that nephrology should embrace a bona fide career track for clinician educators in both the academic institution and professional societies.

Materials and Methods

A MEDLINE search of indexed articles in nephrology medical education was performed with the help of a medical librarian. The search term “nephrology” and subheading “education”, further limited to citations in “English”, “human”, and “full text”, were used. A search with the subheading “fellowship education” and subheading “residency education” was also used. Editorials/letters, commentaries/perspectives, studies related to education of the public or patients, news postings, society addresses, and conference proceedings, continuing medical education/biomedical advances, and studies related to nurse education/practice were excluded. Abstracts from scientific meetings were not searched because a prior publication reviewing all accepted educational research abstracts from the 2008 to 2013 ASN Kidney Week meetings has already been reported (2).

A MEDLINE search of indexed articles to collect a sample of education publications from other fields of medicine was also conducted. Specifically, randomized controlled trials done in medical education research during residency training in other fields of medicine were reviewed. A search with the heading “randomized controlled trials” and subheading “residency training” and subheading “education research” was also used. Selected publications from various fields other than nephrology with rigorous designs were selected to discuss as examples. The outcomes of the studies were categorized under knowledge acquisition, behavior change, or patient care outcomes.

To identify key educator roles of nephrologists in the academic settings, we (K.D.J. and M.A.P.) described typical teaching activities as academic nephrologists. We probed the meaning of these different roles until agreement was reached on their distinctions. Eight roles were defined. To determine if these descriptions could be generalized across academic settings, an Internet survey (using www.surveymonkey.com) was developed and distributed to a group of randomly selected nephrology fellowship training program directors (TPDs) working in different regions of the country and across university and community settings. The survey included a short paragraph for each role that delineated the nephrologist’s teaching role, location of the activity, typical patients, learners involved, and teaching and evaluation methods used. For each role, survey respondents were asked if this role existed in their settings and if the description was accurate, inviting open-ended comments that were then used to revise the role description. Respondents were also invited to describe additional roles. North Shore and Long Island Jewish Health System’s Feinstein Research Institute granted institutional review board exemption for the survey.

Responses to the survey were reviewed, and descriptive statistics (percent responses and acceptance of the descriptions) were performed. Modifications to role descriptions were made on the basis of suggestions of all respondents to each category.

Results

Literature Search

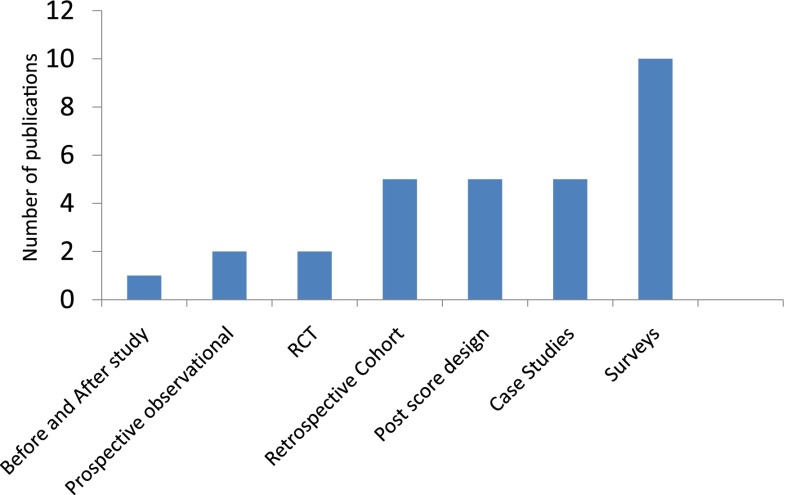

Results of the literature search are shown in Table 1. Seventy-three citations were retrieved for the initial nephrology education research search; most were unrelated to teaching and learning in nephrology. We were left with 30 (41%) articles after applying the exclusion and inclusion criteria. Six articles were related to student learning (3–8), five were related to postgraduate trainees (9–13), and 19 were related to fellows or fellowship training (1,14–31). None of the articles had teachers or faculty members as subjects of the educational investigation. Figure 1 categorizes each of these articles into their respective study design type. In addition, we performed a MEDLINE search of indexed articles from other fields (173 articles) to collect a sample of medical education publications using randomized trials from other fields to provide examples of interventions currently being performed in medical education (Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of literature review on nephrology education research

| Type of Study Design (Ref) | Author (Year) | Outcome Type | Training Level | Study Aim |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case study (3) | Nambudiri (2014) | Knowledge acquisition | Medical students | Describe a 1-month clinical elective course involving multiple medical fields with focus on lupus. |

| Case study (4) | Mezza (2004) | Knowledge acquisition | Medical students | Describe educational session using student-selected nephrology case to integrate narrative and EBM learning. |

| Case study (5) | Richardson (2004) | Knowledge acquisition | Medical students | Test visual demonstration as an instructional strategy to clear up misunderstandings related to clearance and volume. |

| Survey (6) | Piccoli (2004) | Knowledge acquisition and behavior change | Medical students | Test the interest and opinions of medical students. |

| Postscore design (7) | Piccoli (2003) | Knowledge acquisition | Medical students | Teach about RRT in medical school to improve predialysis care later. |

| Postscore design (8) | Elzubeir (2012) | Knowledge acquisition | Medical students | Assess teaching of new PBL curriculum according to students’ and tutors’ perceptions of relevance, stimulation, and amount learned from the problems. |

| Case study (9) | Kamesh (2012) | Knowledge acquisition | Residents | Evaluate resource requirements and effect on service delivery of implementing CBT in renal medicine. |

| Survey (10) | Agrawal (2011) | Knowledge acquisition | Residents | Assess residency preparation for CKD complications seen in primary care. |

| RCT (11) | Davids (2014) | Knowledge acquisition | Medical students/residents | To investigate a usability evaluation of electrolyte case multimedia e-learning resource in medical residents retention of knowledge. |

| RCT (12) | Jhaveri (2012) | Behavior change | Residents | Novel nephrology elective structure compared with traditional inpatient only model on improving interest in nephrology. |

| Postscore design (13) | Calderon (2011) | Knowledge acquisition | Residents | Assessing creative writing as a teaching tool in nephrology to assess knowledge acquisition. |

| Retrospective cohort (14) | Fülöp (2014) | Knowledge acquisition | Fellows | Review of 2.5 years of renal biopsy experience after receiving training and practice in renal sonogram. |

| Retrospective cohort (15) | Amos (2013) | Behavior change | Fellows | Describe the relationship between clinical experiences during training and number of trainees. |

| Before and after study (16) | Dawoud (2012) | Knowledge acquisition | Fellows | Assess change in confidence in kidney biopsy with simulation training; procedural competence measured by outcomes compared with nonparticipants. |

| Retrospective cohort (17) | Coentrao (2012) | Knowledge acquisition | Fellows | Examine the accuracy of physical examination in the assessment of AVF dysfunction compared with angiography. |

| Survey (18) | Combs (2015) | Knowledge acquisition and behavior change | Fellows | Examining the quality of training in and attitudes toward end-of-life care and knowledge and preparedness to provide nephrology-specific end-of-life care of renal fellows. |

| Retrospective cohort (19) | Yuan (2014) | Knowledge acquisition | Fellows | Outpatient encounter chart audits during training years corresponding to participation in the nephrology in-training examination; assessing long-term deficiencies via chart audits. |

| Postscore design (20) | Prince (2014) | Knowledge acquisition | Fellows | Use of observed standardized clinical examinations in the recognition and management of rare hemodialysis emergencies. |

| Survey (21) | Shah (2014) | Knowledge acquisition and behavior change | Fellows | Assessing palliative and end-of-life training in nephrology fellows. |

| Retrospective cohort (22) | Fülöp (2013) | Knowledge acquisition | Fellows | Assessing the competency of trainees in tunneled catheter removal. |

| Survey (23) | Clark (2013) | Knowledge acquisition | Fellows | Assessing the comfort level of catheter insertion for dialysis by renal fellows in training in Canada. |

| Postscore design (24) | Shah (2013) | Knowledge acquisition | Fellows | Novel tool used to do interdivisional debates. |

| Survey (25) | Jhaveri (2013) | Knowledge acquisition and behavior change | Fellows | A web-based survey asking why nonrenal fellows did not choose nephrology as a career choice. |

| Survey (1) | Shah (2012) | Behavior change | Fellows | A web-based survey on career satisfaction of nephrology fellows in training. |

| Prospective observational cohort (26) | Ahya (2012) | Knowledge acquisition | Fellows | Simulation trained fellows on catheter insertion followed for 6 months on actual patient catheter insertions using the checklist and reassessed for retention at 1 year. |

| Survey (27) | Weinstein (2010) | Knowledge acquisition and behavior change | Fellows | Web-based survey in assessing the reasons for entry into pediatric nephrology workforce. |

| Survey (28) | Berns (2010) | Knowledge acquisition | Fellows | An Internet-based survey to rate fellowship training in specific areas and the importance of each area to their current careers and practices. |

| Prospective observational cohort (29) | Barsuk (2009) | Knowledge acquisition | Fellows | Comparing traditional training versus simulator training for dialysis catheter insertion for fellows in training with follow-up clinical care. |

| Survey (30) | Holley (2003) | Knowledge acquisition and behavior change | Fellows | Survey of fellows in training on end-of-life care in nephrology. |

| Case study (31) | Jhaveri (2012) | Knowledge acquisition | Fellows | Evaluation of a novel teaching tool to teach in the classroom setting in nephrology. |

Ref, reference; RCT, randomized controlled trial; EBM, evidence-based medicine; PBL, problem-based learning; CBT, competency-based training; AVF, arteriovenous fistula.

Figure 1.

Number of nephrology medical education publications reviewed (N=30) categorized by research method type. RCT, randomized controlled trials.

Table 2.

Selected medical education research studies in other fields of medicine.

| Type of Study Design (Ref) | Author (Year) | Field of Medicine | Outcome Type | Training Level | Study Aim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT (32) | Kerfoot (2007) | Urology | Knowledge acquisition | Residents | Study the effect of educational program on the basis of spacing effect principles on acquisition and retention of medical knowledge in comparison with standard testing. |

| RCT (33) | Kerfoot (2008) | Urology | Knowledge acquisition | Medical students | Study the effect of educational program on the basis of spacing effect principles on acquisition and retention of medical knowledge in comparison with standard testing. |

| RCT (34) | Kerfoot (2010) | Urology | Knowledge acquisition | Medical students | Study the effect of spaced education on improving learning efficiency compared with standard methods. |

| Prospective trial (35) | Kerfoot (2012) | Urology | Knowledge acquisition | Residents | Study the effect of a spaced education game methodology on knowledge acquisition on surgery residents. |

| RCT (36) | Destephano (2015) | Obstetrics | Knowledge acquisition | Medical students | Study to evaluate the effectiveness of a high-fidelity birth simulator compared with a lower-cost, low-tech, birth simulator in teaching medical students on how to perform a spontaneous vaginal delivery. |

| RCT (37) | Nesbitt (2015) | Surgery | Assessing feedback | Medical students/faculty | Study to evaluate the benefit of two types of video feedback (individualized video feedback, with the student reviewing their performance with an expert tutor, and unsupervised video-enhanced feedback, where the student reviews their own performance together with an expert teaching video) to determine if these improve performance when compared with a standard lecture feedback. |

| RCT (38) | Bongers (2014) | Surgery | Assessing multitasking | Medical students | Study to examine whether multitasking and more specifically task switching can be trained in a virtual reality laparoscopic skills simulator. |

| RCT (39) | Saeidifard (2014) | Endocrinology | Knowledge acquisition | Medical students | Study to compare concept mapping with lecture-based method in teaching of evidence-based educated topic to medical students. |

| RCT (40) | Pfund (2014) | Internal medicine | Research methods, knowledge acquisition | Faculty | Study to see whether a structured mentoring curriculum improves research mentoring skills. |

| RCT (41) | Pucher (2014) | Surgery | Knowledge acquisition | Residents | Study to investigate the effects of a simulation-based curriculum for ward-based care on ward round performance. |

| RCT (42) | Connolly (2014) | Pediatrics | Knowledge acquisition | Residents | Study to create and evaluate the educational effectiveness of a digital resource instructing pediatric trainees in a systematic approach to observe child development. |

| RCT (43) | Curtis (2013) | Internal medicine | Patient care outcomes | Residents/nurse practitioners trainees | Study that examined if simulation-based training improves skill acquisition of communication skills improves patient care outcomes in end-of-life care compared with standard setting. |

| RCT (44) | Ward (1996) | Family medicine | Patient care outcomes | Residents | Study the effect on clinical behavior of a 3-day workshop designed to increase trainees' rates of smoking cessation counseling and reminders about Pap smears in routine consultations. |

| RCT (45) | Holmboe (2004) | Internal medicine | Knowledge and behavior changes | Faculty | Study the efficacy of a new multifaceted method of faculty development called direct observation of competence training. |

| RCT (46) | Kim (2014) | Internal medicine | Knowledge acquisition | Residents | Study the speed and accuracy of answering clinical questions using Google versus summary resources. |

| RCT (47) | Harris (2013) | Internal medicine | Knowledge acquisition | Residents and faculty | Study to compare the educational effectiveness of two virtual patient based e-learning strategies versus no training in improving physicians' substance abuse management knowledge, attitudes, self-reported behaviors, and decision making. |

| RCT (48) | Cook (2009) | Internal medicine | Knowledge acquisition | Residents | Study the comparative efficacy of case-based and noncase-based self-assessment questions in web-based instructions. |

| RCT (49) | Bump (2012) | Internal medicine | Behavior change, knowledge acquisition | Residents and faculty | Study to see if a sign-out checklist paired with faculty member review and feedback would improve interns' written sign-out compared with standard setting. |

Ref, reference; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Roles of Nephrologists and Survey Summary

To define the various teaching roles that nephrologists perform, we surveyed TPDs from several institutions to describe the teaching roles at their center. Twelve TPDs responded to our survey (75% of those invited). The TPDs reported that seven of the eight predefined teaching roles existed at their respective institution, and approximately 60% of the TPDs felt the eight teaching role descriptions were accurate (Table 3). On the basis of survey responses, changes to the teaching descriptions were made to internal medicine attending role, medical school classroom teacher, and research mentor categories. Medical school classroom teacher was renamed classroom teaching to encompass resident and fellow teaching in the classroom setting. Patient-centered quality improvement project mentoring was added to the research mentor section. Of all of the eight teaching role descriptions, the only role that did not exist throughout each of the sampled centers was nephrologists as the internal medicine attending. However, because this role was present in 68% of the TPDs surveyed, we included it as a final educator role.

Table 3.

Descriptions of the eight roles of the nephrologists as educator

| Role | Description |

|---|---|

| Internal medicine attending | This is a hospital-based role. The nephrologist serves as the hospitalist and is the leader of a team of learners which may include third- and fourth-year medical students, PA students, internal medicine residents, and nephrology fellows. On the basis of our review and survey, in some centers, the nephrologist serves as the hospitalist of record (also responsible for patient care and billing), but in most centers, they serve as the teaching attending with a separate hospitalist attending responsible for patient care and billing. |

| Renal inpatient consult attending | This is a hospital-based role. The nephrologist’s clinical expertise is requested to assist with the care of hospitalized (acute and critical care) patients. In addition, the consult attending would also take care of patients with CKD and complications related to kidney disease in the hospitalized patient with CKD. The consult team includes attending nephrologists, nephrology fellows, internal medicine residents, and fourth-year medical students/PA students. The nephrologist serves as attending of record and supervisor of team members. |

| Inpatient ESRD service attending | This is a hospital-based role. The nephrologist’s clinical expertise is requested to assist with care to hospitalized patients with ESRD, and the team may include third- and fourth-year medical students, internal medicine residents, nephrology fellows, and an attending nephrologist. Nephrologists serve as the attending of record and supervisor of team members. |

| Outpatient nephrology clinic attending | This is an outpatient clinic/office-based role. Nephrology care is provided to patients referred for nephrology consultation for an array of conditions. Patients with CKD make up the bulk of patients, but other renal problems (glomerular disease, cancer-related kidney disease, cardiorenal, liver-related kidney disease, electrolyte and acid-base disturbances, etc) are also cared for in the ambulatory setting. Clinic participants may include third- and fourth-medical students and PA students who elect the rotation, whereas the nephrology attending often sees patients with nephrology fellows (continuity clinic) and, at times, internal medicine residents. Nephrologists serve as attending of record and supervisor of team members. |

| Outpatient ESRD unit attending | This is an outpatient-based role. Nephrology (ESRD) care is provided in the hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis unit setting; however, some patients may be seen separately in the office/clinic. Patients with ESRD in the ambulatory setting constitute the group care for the nephrologist. The third- and fourth-year medical students, PA students, and internal medical residents may elect this rotation. Nephrologists serve as the attending of record and supervisor of team members. Patient and/or family members, social worker, pharmacist, dietician, and nursing staff may have significant ancillary teaching roles in this setting. |

| Transplant attending | This is a both an inpatient and outpatient-based role. Transplant nephrologists provide care to renal transplant recipients in the hospital and outpatient settings, often emphasizing the pre-/during/post-transplant pathway of care. The third- and fourth-year medical students and PA students may elect this rotation. Nephrology fellows are required to participate as part of their training. Nephrologists and transplant surgeons serve as attending of record and supervisors of team members. |

| Classroom teacher | This important role takes place in the medical school classroom for all levels in medical school coursework. Other classroom-like venues include didactic noon conferences for internal medicine residents and students and core curriculum conferences for nephrology fellows. These include nephrology grand rounds, fellow’s pathophysiology lecture series, dialysis seminars, journal club conferences, and renal pathology seminars. The nephrologist serves as a classroom instructor; usually students, internal medicine residents, nephrology fellows, and other nephrologists are present at these sessions. |

| Research mentor | This academic role takes place in a research setting (laboratory, office, clinic, research center), and the length is variable and depends on project and level of learner. Medical students, internal medicine residents, and nephrology fellows can be involved. Types of research varies from basic science, clinical research, outcomes research, education research, quality improvement projects, systematic reviews/meta-analyses, review articles, case series, and case reports. The nephrologist serves as the research mentor and senior collaborator for the trainee’s project. |

PA, physician assistant.

On the basis of differences in structure in some centers, description of the internal medicine attending was altered to include nephrologists to be either service attending of record or teaching attending only. Overall, the rest of the survey results were in agreement with the eight roles of nephrologists as educators. The eight roles are as follows: (1) inpatient medicine attending, (2) renal inpatient consult attending, (3) inpatient ESRD service attending, (4) outpatient nephrology clinic attending, (5) transplant attending, (6) outpatient ESRD unit attending, (7) classroom teacher (medical student/resident/fellow didactic teacher), and (8) research mentor. The nephrologist-as-educator role descriptions are shown in Table 3. In addition, Table 4 highlights the similarities and differences within the different roles of the nephrology educator.

Table 4.

Comparison of the eight roles of the nephrologists as educator

| Inpatient Medicine Attending | Renal Inpatient Consult Attending | ESRD Inpatient Service Attending | Outpatient Nephrology Clinic Attending | Transplant Attending | Outpatient ESRD unit Attending | Classroom Teacher | Research Mentor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Hospital | Hospital | Hospital | Clinic | Hospital and clinic | Dialysis unit (ambulatory) | Hospital, medical school | Laboratory, office |

| Patient care | General medicine patients with nephrology-related problems and illnesses | Nephrology consultation requested for hospitalized patients | Hospitalized patients with ESRD (during dialysis); other medical issues related to kidney disease | Nephrology consultation is requested; established chronic renal disease diagnosis | Pre- and postrenal transplant including new transplant and complications | ESRD for chronic dialysis care (in center, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, home hemodialysis) | NA | NA |

| Teaching setting | Bedside, Conference room | Bedside, conference room | Bedside, dialysis chair/bed, conference room | Examination room, Staff room | Bedside, examination room, conference room | Dialysis chair, team huddle, conference room | Classroom, lecture hall, grand rounds | Laboratory, office |

| Learners involved, typical rotation length | ||||||||

| Third-year student | 4–6 wk block | 2–4 wk elective | Not standard but may be part of renal elective | 2–4 wk elective | Not standard but available as an elective | Not standard but may be part of renal elective | Entire year | Entire year |

| Fourth-year student | 2–4 wk elective | Not standard but may be part of renal elective | 2–4 wk elective | Not standard but available as an elective | Not standard but may be part of renal elective | Entire year | Entire year | |

| PGY 1 resident | 2–4 wk block | 2–4 wk elective | Not standard but may be part of renal elective | 2–4 wk elective | Not standard but may be part of renal elective | Not standard but may be part of renal elective | Variable | Variable |

| PGY 2 and 3 resident | 2–4 wk block | 4 wk elective | Not standard but may be part of renal elective | 2–4 wk elective | Not standard but may be part of renal elective | Not standard but may be part of renal elective | Variable | Variable |

| First-year fellow | NA | 4 wk | 4 wk | Continuity clinic | 4–8 wk | 4 wk | Entire year | Variable |

| Second-year fellow | 2–4 wk block (some centers) | 4 wk | 4 wk | Continuity clinic | 4–8 wk | 4 wk | Entire year | Variable |

| Others involved during teaching | ||||||||

| Primary nurse | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | NA |

| NP or PA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | NA |

| Social worker | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | NA |

| Pharmacist | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | NA | NA |

| Nutritionist | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | NA | NA |

PGY, postgraduate; NA, not applicable; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant.

Discussion

Medical education in nephrology appears to lag behind the research and innovations occurring in other specialties. There are few rigorous studies on nephrology education published and little information on the role of clinician educators in nephrology. The important areas are subsequently discussed.

Education Research in Nephrology

Our literature review reveals that little guidance exists for addressing the teaching roles of nephrologists or faculty development that supports nephrology educators. Most reported single-site descriptive studies about curricular innovations. None discussed how nephrology educators might gain a deeper understanding of or how to improve their teaching, clinical supervision, or mentorship. Additionally, to compare and illustrate, we reviewed literature in other fields of medicine to illustrate examples of medical education scholarship (32–49) (Table 2). Research in medical education, just as in clinical research, is a highly structured process that involves careful protocols with a clear hypothesis, defined subjects, and careful data analysis. Importantly, we must improve our reporting and dissemination of high-quality medical education research. These data suggest that research in medical education in nephrology is lagging behind other specialties in medicine. In fact, we could only find a few studies that meet the rigor of bona fide medical education research (11,12,29). Only two articles met the randomized controlled trial design (11,12). In contrast, we found high-quality medical education research studies reported in both general internal medicine and surgery (Table 2). The articles in other fields can serve as a template for nephrology educators interested in pursuing high-quality educational research with rigorous methods that can be used to model their own research studies.

Rigor in Education Research

The conceptual framework most widely used in medical education research is the Kirkpatrick classification that categorizes the outcome to either perception or knowledge of the trainee to change in patient outcomes (42). This framework suggests educational research that ultimately improves patient care has the biggest effect (Table 5) (50). However, most articles reported in nephrology educational research as described in Table 2 relate to outcomes of the participants rather than downstream patient care outcomes. We suggest that more research studies in medical education in nephrology need to be pursued that are level 4a or 4b that directly affect patient outcomes. Although levels 1–3 are important to consider in nephrology, randomized trials aiming for a level 4 type of outcome are desired. An example of a well designed randomized controlled trial in medical education with patient care outcomes that is currently ongoing is individualized comparative effectiveness of models optimizing patient safety and resident education. Nephrology educators should strive for study designs and outcomes that are similar in their research projects (51).

Table 5.

Kirkpatrick classification

| Level | Details |

|---|---|

| 1 | Perception of training by subjects |

| 2a | Change of attitudes in subjects |

| 2b | Change of knowledge/skills of subjects |

| 3 | Change of behavior of subjects |

| 4a | Change in professional practice |

| 4b | Change in patient outcomes |

Modified from reference 50, with permission.

Rigor is needed to conduct high-quality medical education research. As a guide to the nephrology educator interested in conducting research in medical education, we have summarized the various types of research in education in Table 6. Furthermore, Table 7 proposes a stepwise approach on developing a scholarly project in medical education. Once the type of study is identified, it must be refined to create a conceptual framework followed by review of the literature to find existing gaps in understanding. Understanding and identifying appropriate study designs and methods will substantially improve the quality of scholarly projects. Selecting outcomes a priori becomes one of the most important components in designing a study. Applying this systematic approach to study design will help to improve the rigor of medical education research in nephrology (52).

Table 6.

Medical education research study designs (quantitative and qualitative)

| Type | Study Design | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Surveys | Quantitative | Inexpensive, convenient. Most common tool used. Nonresponse bias, validity, and reliability of the survey tool. |

| Postcourse designs | Quantitative | Data collection after a new course or innovation; tool used is surveys. Inexpensive, straightforward, quick to conduct and analyze, and high response rates. No collection of baseline data, unable to measure long-term effect of intervention. |

| Before and after studies | Quantitative | Similar to postcourse designs except before and after surveys used; easy to design and collect data; close proximity of data gives high response rates and tracking; limited in providing rigorous understanding of long-term change. No control group. |

| Longitudinal studies | Quantitative | Effect of intervention over time; can assess long-term effects of an intervention; good design to establish relevance in clinical practice; limited because of learners change training, jobs, and location over time; collective data long term might be burdensome. |

| Controlled before and after studies | Quantitative | Quasi-experimental technique; more robust then aforementioned methods; amount of time and data collection increases; loss to follow-up; long-term change is hard to assess. |

| Randomized controlled trials | Quantitative | Similar to clinical trials; most robust form of data; minimal bias; gold standard, but not common in medical education because of sample size–related concerns; ethical objections regarding education intervention |

| Meta-analysis | Quantitative | Similar to meta-analysis or other medical reviews; increasingly used in medical education; can generate evidence synthesis; time and cost intensive. |

| Ethnography | Qualitative | Use observations of social groups in real environment and interviews to focus on meanings of actions and explanations; development of theories. |

| Phenomenology | Qualitative | Use observations and interviews and personal documents, such as diaries, to gain insight in the experience. |

| Grounded theory | Qualitative | Use variety of qualitative data, such as focus groups, diaries, and interviews, to get results. |

| Case studies | Qualitative | Examine a particular situation (individuals, groups, events, roles); can get complex phenomenon data. |

| Action research studies | Qualitative | Researchers work together with participants in cycles of action and change and guide participants in the change process; researchers help participants to develop, deliver, study, and improve practice ultimately |

| Mixed designs | Qualitative and quantitative | Can provide more detailed outcomes in medical education activities, resource intensive, and cost. Requires expertise to design. |

Table 7.

Three steps for developing a scholarly project in medical education

| Three Steps |

|---|

| 1. Refine the study question via literature review, problem statement, conceptual framework, and statement of study intent. |

| 2. Identify designs and methods (experimental, observational or qualitative, or a systematic review). |

| 3. Select outcomes (knowledge, attitude, professional behavior change, or patient care outcomes) and outcome methods (surveys or other assessment tools). |

Roles of Nephrologists as Educators: A Good Starting Point

Where does one begin when conducting research in medical education in nephrology? The various roles nephrologists play as educators are first defined to better guide us in potential avenues to conduct educational research. Once these roles are better defined, different educational interventions can be undertaken to improve the outcomes of education and ultimately positively affect patient care. To address this gap, we identified eight roles for the nephrologist educator. A selected group of TPDs confirmed these descriptions as accurately representing the nephrologists’ educator roles in most academic health centers in the United States. One limitation of our approach is the potential for sampling bias given the small sample size (12/140) of our survey. However, our goal was simply to attempt to validate and make changes of our descriptions of nephrology education roles.

The roles described in Table 3 shed some light on various venues where nephrologists do interact with trainees across the medical education spectrum. Several unifying themes emerged among the different educator roles. The responsibility of the nephrologist educator includes assuring excellent patient-centered care, supervising learners’ care of patients, making judgments about what learners can be trusted to do with less supervision (53,54), assessing a learners’ performance, and providing constructive feedback. A comparison of the various nephrology teaching roles illustrated in Table 4 demonstrates the wide variety of learners that a nephrologist educator interacts with. These could include medical students, physician assistant students, interns, residents, or fellows. In the ESRD outpatient unit, the learners are usually fellows, but in some centers, medical students and residents might rotate on this service (12).

Comparison of the nephrology teaching roles (Table 3) also highlights the opportunity for nephrologist educators to take the lead in developing interprofessional clinical learning experiences. With increasing emphasis on teamwork and collaborative practice noted in training program requirements (54), these venues could serve as ideal environments for learners from multiple professions to work together and learn about each other’s roles and responsibilities. These interactions could help to improve communication and collaboration among disparate professions, ultimately leading to new ways at looking at old problems. This could be especially beneficial when treating patients with complex health care needs such as CKD. For example, patients nearing the need for RRT involve collaborative practice among physicians, nurses, social workers, nutritionists, pharmacists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants (ESRD units and transplant settings). All of these are potential topics for medical education research.

Roadmap for Nephrologists as Educators

Additional training in education research design and implementation is increasingly becoming mandatory for successfully navigating a career in medical education research (55). Courses have been designed to help provide an overview of a wide range of topics in education. Most courses should cover the following five domains: (1) principles and theories of education, (2) teaching methods, (3) educational research methods, (4) assessment and evaluation, and (5) educational leadership. The medical education research certificate from the Association of American Medical Colleges (56) is an excellent short course that is intended to provide the knowledge necessary to understand the purposes and processes of medical education research, to understand necessary literature, and to be effective collaborators in medical education research in nephrology. However, the medical education research certificate alone is not sufficient to produce independent medical education researchers. A master’s or doctorate degree in medical education is recommended to those planning on devoting a significant portion of their effort to medical education research. The Foundation of Advancement of International Medical Education and Research (57) website offers a listing of programs around the world. Additionally, the Harvard Macy Institute (58) offers training in medical education research for various experience levels and is another great resource. Besides acquiring knowledge of education theory and methodology, the aforementioned courses allow creation of appropriate mentorship that fosters creativity and guidance in the initiation of novel projects.

Several deficiencies in nephrology education research were identified: (1) few rigorous studies performed in nephrology education and (2) lack of information on the role of educators in various aspects of nephrology. Eight distinct educational roles for nephrologist educators that include the classroom setting, inpatient wards, outpatient clinics, and dialysis units were identified. Our goal is to clarify these educational roles to provide a foundation for educational research and scholarship. Enhancing research that is rigorous and thoughtful in nephrology education will lead to improved curriculum design, instructional strategies, workplace activities of learners, and competency assessment. All of these educational venues challenge nephrologist educators to balance the demands of providing quality clinical care to patients with educating fellows, residents, and students.

The time is ripe for nephrologists to address educational challenges and opportunities with the same standards applied to advancing basic science and clinical research.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following training program directors in nephrology for helping us define the clinical roles of the nephrologists: Drs. Nancy Adams, Gregory Braden, Stan Nahman, Suzanne M. Norby, Alan S. Segal, and Charuhas Thakar. We also thank all other anonymous survey respondents. Thank you to Dr. Judith L. Bowen, Medical Education, Oregon Health and Science University, for her tremendous contribution to the initial version of this manuscript and to Dr. Matthew A. Sparks, Duke University and Durham VA Medical Centers, for critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Shah HH, Jhaveri KD, Sparks MA, Mattana J: Career choice selection and satisfaction among US adult nephrology fellows. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1513–1520, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jhaveri KD, Wanchoo R, Maursetter L, Shah HH: The need for enhanced training in nephrology medical education research. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 807–808, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nambudiri VE, Newman LR, Haynes HA, Schur P, Vleugels RA: Creation of a novel, interdisciplinary, multisite clerkship: “Understanding lupus”. Acad Med 89: 404–409, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mezza E, Oggé G, Attini R, Rossetti M, Soragna G, Consiglio V, Burdese M, Vespertino E, Tattoli F, Gai M, Motta D, Segoloni GP, Todros T, Piccoli GB: Pregnancy after kidney transplantation: An evidence-based approach. Transplant Proc 36: 2988–2990, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson D, Speck D: Addressing students’ misconceptions of renal clearance. Adv Physiol Educ 28: 210–212, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piccoli GB, Putaggio S, Soragna G, Mezza E, Burdese M, Bergamo D, Longo P, Rinaldi D, Bermond F, Gai M, Motta D, Novaresio C, Jeantet A, Segoloni GP: Kidney vending: Opinions of the medical school students on this controversial issue. Transplant Proc 36: 446–447, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piccoli GB, Mezza E, Soragna G, Pacitti A, Burdese M, Gai M, Quaglia M, Fabrizio F, Anania P, Jeantet A, Segoloni GP: Teaching peritoneal dialysis in medical school: An Italian pilot experience. Perit Dial Int 23: 296–299, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elzubeir MA: Teaching of the renal system in an integrated, problem-based curriculum. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 23: 93–98, 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamesh L, Clapham M, Foggensteiner L: Developing a higher specialist training programme in renal medicine in the era of competence-based training. Clin Med 12: 338–341, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agrawal V, Agarwal M, Ghosh AK, Barnes MA, McCullough PA: Identification and management of chronic kidney disease complications by internal medicine residents: A national survey. Am J Ther 18: e40–e47, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davids MR, Chikte UM, Halperin ML: Effect of improving the usability of an e-learning resource: A randomized trial. Adv Physiol Educ 38: 155–160, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jhaveri KD, Shah HH, Mattana J: Enhancing interest in nephrology careers during medical residency. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 350–353, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calderon K, Jhaveri KD: Invited manuscript poster on renal-related education American Society of Nephrology, Nov. 16-21, 2010. Creative writing in nephrology education. Ren Fail 33: 655–657, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fülöp T, Alemu B, Dossabhoy NR, Bain JH, Pruett DE, Szombathelyi A, Dreisbach AW, Tapolyai M: Safety and efficacy of percutaneous renal biopsy by physicians-in-training in an academic teaching setting. South Med J 107: 520–525, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amos L, Toussaint ND, Phoon RK, Elias TJ, Levidiotis V, Campbell SB, Walker AM, Harrex C: Increase in nephrology advanced trainee numbers in Australia and associated reduction in clinical exposure over the past decade. Intern Med J 43: 287–293, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawoud D, Lyndon W, Mrug S, Bissler JJ, Mrug M: Impact of ultrasound-guided kidney biopsy simulation on trainee confidence and biopsy outcomes. Am J Nephrol 36: 570–574, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coentrao L, Faria B, Pestana M: Physical examination of dysfunctional arteriovenous fistulae by non-interventionalists: A skill worth teaching. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 1993–1996, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Combs SA, Culp S, Matlock DD, Kutner JS, Holley JL, Moss AH: Update on end-of-life care training during nephrology fellowship: A cross-sectional national survey of fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 233–239, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan CM, Prince LK, Zwettler AJ, Nee R, Oliver JD, 3rd, Abbott KC: Assessing achievement in nephrology training: Using clinic chart audits to quantitatively screen competency. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 737–743, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prince LK, Abbott KC, Green F, Little D, Nee R, Oliver JD, 3rd, Bohen EM, Yuan CM: Expanding the role of objectively structured clinical examinations in nephrology training. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 906–912, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah HH, Monga D, Caperna A, Jhaveri KD: Palliative care experience of US adult nephrology fellows: A national survey. Ren Fail 36: 39–45, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fülöp T, Tapolyai M, Qureshi NA, Beemidi VR, Gharaibeh KA, Hamrahian SM, Szarvas T, Kovesdy CP, Csongrádi E: The safety and efficacy of bedside removal of tunneled hemodialysis catheters by nephrology trainees. Ren Fail 35: 1264–1268, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark EG, Schachter ME, Palumbo A, Knoll G, Edwards C: Temporary hemodialysis catheter placement by nephrology fellows: Implications for nephrology training. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 474–480, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah HH, Mattana J, Jhaveri KD: Evidence-based nephrology-rheumatology debates: A novel educational experience during nephrology fellowship training. Ren Fail 35: 911–913, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jhaveri KD, Sparks MA, Shah HH, Khan S, Chawla A, Desai T, Iglesia E, Ferris M, Parker MG, Kohan DE: Why not nephrology? A survey of US internal medicine subspecialty fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 61: 540–546, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahya SN, Barsuk JH, Cohen ER, Tuazon J, McGaghie WC, Wayne DB: Clinical performance and skill retention after simulation-based education for nephrology fellows. Semin Dial 25: 470–473, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein AR, Reidy K, Norwood VF, Mahan JD: Factors influencing pediatric nephrology trainee entry into the workforce. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1770–1774, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berns JS: A survey-based evaluation of self-perceived competency after nephrology fellowship training. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 490–496, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barsuk JH, Ahya SN, Cohen ER, McGaghie WC, Wayne DB: Mastery learning of temporary hemodialysis catheter insertion by nephrology fellows using simulation technology and deliberate practice. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 70–76, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holley JL, Carmody SS, Moss AH, Sullivan AM, Cohen LM, Block SD, Arnold RM: The need for end-of-life care training in nephrology: National survey results of nephrology fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 813–820, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jhaveri KD, Chawla A, Shah HH: Case-based debates: An innovative teaching tool in nephrology education. Ren Fail 34: 1043–1045, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerfoot BP, Baker HE, Koch MO, Connelly D, Joseph DB, Ritchey ML: Randomized, controlled trial of spaced education to urology residents in the United States and Canada. J Urol 177: 1481–1487, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerfoot BP: Interactive spaced education versus web based modules for teaching urology to medical students: A randomized controlled trial. J Urol 179: 2351–2356, discussion 2356–2357, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerfoot BP: Adaptive spaced education improves learning efficiency: a randomized controlled trial. J Urol 183: 678–681, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerfoot BP, Baker H: An online spaced-education game to teach and assess residents: A multi-institutional prospective trial. J Am Coll Surg 214: 367–373, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeStephano CC, Chou B, Patel S, Slattery R, Hueppchen N: A randomized controlled trial of birth simulation for medical students. Am J Obstet Gynecol 213: 91:e1–e7, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nesbitt CI, Phillips AW, Searle RF, Stansby G: Randomized trial to assess the effect of supervised and unsupervised video feedback on teaching practical skills. J Surg Educ 72: 697–703, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bongers PJ, Diederick van Hove P, Stassen LP, Dankelman J, Schreuder HW: A new virtual-reality training module for laparoscopic surgical skills and equipment handling: can multitasking be trained? A randomized controlled trial. J Surg Educ 72: 184–191, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saeidifard F, Heidari K, Foroughi M, Soltani A: Concept mapping as a method to teach an evidence-based educated medical topic: a comparative study in medical students. J Diabetes Metab Disord 13: 86, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfund C, House SC, Asquith P, Fleming MF, Buhr KA, Burnham EL, Eichenberger Gilmore JM, Huskins WC, McGee R, Schurr K, Shapiro ED, Spencer KC, Sorkness CA: Training mentors of clinical and translational research scholars: A randomized controlled trial. Acad Med 89: 774–782, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pucher PH, Aggarwal R, Singh P, Srisatkunam T, Twaij A, Darzi A: Ward simulation to improve surgical ward round performance: A randomized controlled trial of a simulation-based curriculum. Ann Surg 260: 236–243, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Connolly AM, Cunningham C, Sinclair AJ, Rao A, Lonergan A, Bye AM: ‘Beyond Milestones’: A randomised controlled trial evaluating an innovative digital resource teaching quality observation of normal child development. J Paediatr Child Health 50: 393–398, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curtis JR, Back AL, Ford DW, Downey L, Shannon SE, Doorenbos AZ, Kross EK, Reinke LF, Feemster LC, Edlund B, Arnold RW, O’Connor K, Engelberg RA: Effect of communication skills training for residents and nurse practitioners on quality of communication with patients with serious illness: a randomized trial. JAMA 310: 2271–2281, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ward J, Sanson-Fisher R: Does a 3-day workshop for family medicine trainees improve preventive care? A randomized control trial. Prev Med 25: 741–747, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holmboe ES, Hawkins RE, Huot SJ: Effects of training in direct observation of medical residents’ clinical competence: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 140: 874–881, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim S, Noveck H, Galt J, Hogshire L, Willett L, O’Rourke K: Searching for answers to clinical questions using google versus evidence-based summary resources: A randomized controlled crossover study. Acad Med 89: 940–943, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris JM, Jr, Sun H: A randomized trial of two e-learning strategies for teaching substance abuse management skills to physicians. Acad Med 88: 1357–1362, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cook DA, Thompson WG, Thomas KG: Case-based or non-case-based questions for teaching postgraduate physicians: A randomized crossover trial. Acad Med 84: 1419–1425, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bump GM, Bost JE, Buranosky R, Elnicki M: Faculty member review and feedback using a sign-out checklist: Improving intern written sign-out. Acad Med 87: 1125–1131, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beckman TJ, Cook DA: Developing scholarly projects in education: A primer for medical teachers. Med Teach 29: 210–218, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.iCOMPARE: Purpose and goals of the trial. Available at: http://www.jhcct.org/icompare/default.asp. Accessed June 3, 2015

- 52.Barr H, Koppel I, Reeves S, Hammick M, Freeth S: Effective interprofessional education: argument, assumption and evidence, Oxford, United Kingdom, John Wiley and Sons, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen HC, van den Broek WE, ten Cate O: The case for use of entrustable professional activities in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med 90: 431–436, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caverzagie KJ, Cooney TG, Hemmer PA, Berkowitz L: The development of entrustable professional activities for internal medicine residency training: A report from the Education Redesign Committee of the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine. Acad Med 90: 479–484, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cook DA: Randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis in medical education: what role do they play? Med Teach 34: 468–473, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Association of American Medical Colleges: Medical Education Research Certificate (MERC) Program. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/members/gea/merc/. Accessed March 22, 2015

- 57.Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research: Master’s Programs in Health Professions Education. Available at: http://www.faimer.org/resources/mastersmeded.html. Accessed March 22, 2015

- 58.Harvard Macy Institute: Available at: http://www.harvardmacy.org/. Accessed March 22, 2015