Abstract

Context:

It has been proposed that serum free 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] may better reflect vitamin D action than total 25(OH)D. An ELISA for serum free 25(OH)D has recently become available, permitting direct assay.

Objective:

To determine whether serum free 25(OH)D provides additional information in relation to calcium absorption and other biomarkers of vitamin D action compared to total serum 25(OH)D.

Setting:

Ambulatory research setting in a teaching hospital.

Outcome:

Serum free 25(OH)D measured in a previously performed study of varied doses of vitamin D3 (placebo and 800, 2000, and 4000 IU) on calcium absorption, PTH, procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide, and C-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen. Free 25(OH)D was measured by ELISA. Calcium absorption was measured at baseline and at 10 weeks using stable dual calcium isotopes.

Results:

Seventy-one subjects completed this randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Baseline group mean free and total 25(OH)D varied from 4.7 ± 1.8 to 5.4 ± 1.5 pg/mL, and from 23.7 ± 5.9 to 25.9 ± 6.1 ng/mL, respectively. Participants assigned to the 4000-IU dose arm achieved free 25(OH)D levels of 10.4 pg/mL and total 25(OH)D levels of 40.4 ng/mL. Total and free 25(OH)D were highly correlated at baseline and after increasing vitamin D dosing (r = 0.80 and 0.85, respectively). Free 25(OH)D closely reflected changes in total 25(OH)D. PTH was similarly correlated at baseline and follow-up with total and free 25(OH)D. Serum C-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen had a moderate positive correlation with total and free 25(OH)D at follow-up. The serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D change increased significantly with the change in 25(OH)D but not with the change in free 25(OH)D.

Conclusion:

There was no advantage from measuring free over total 25(OH)D in assessing the response of calcium absorption, PTH, and markers of bone turnover to vitamin D. Free 25(OH)D responded to increasing doses of vitamin D in a similar fashion to total 25(OH)D.

It has been suggested that the free form of hormones (the quantity unattached to binding proteins) may be important for transporting the hormones into cells (1). This has been called the “free hormone hypothesis.” This concept involving unbound hormone has clinical applicability for T4, cortisol, and sex steroids and has been considered particularly relevant where illness or drugs affect serum levels of hormone binding proteins.

Although free 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D], but not total 1,25(OH)2D, is influential on target cell function, the free hormone hypothesis has not been enthusiastically embraced for 25(OH)D, a prohormone (25-hydroxyvitamin D) (2). One reason for this has been the elucidation of the role of megalin, a protein that is a multiligand receptor in several tissues. Megalin in the proximal tubule is a cell surface receptor for vitamin D binding protein (VDBP). The megalin-VDBP complex undergoes internalization in the cell through endocytosis, and the hydroxylase in the cell acting on 25(OH)D results in the intracrine synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D. Cubulin may assist in this function. Because 1,25(OH)2D is critical in the vitamin D endocrine system, the role of bound 25(OH)D has been viewed by some as more important than free 25(OH)D. Nonetheless, the free hormone hypothesis is compatible with the role of 25(OH)D in cells other than renal cells, and vitamin D has been implicated in many extraskeletal disorders (2).

The concept of free 25(OH)D has recently been reconsidered when it was shown that blacks had similar concentrations of free 25(OH)D compared to whites despite their lower levels of total 25(OH)D (3). It was demonstrated that blacks had genetic polymorphisms that result in lower concentrations of VDBP. This may explain the paradox whereby African Americans do not have inferior bone health despite their lower concentration of total serum 25(OH)D (4).

The relative influence of total serum 25(OH)D and free 25(OH)D has also been addressed by their relationship to biomarkers of vitamin D action such as bone density and serum PTH levels with variable findings (2, 3, 5). We recently completed a study of the response of calcium absorption to increasing doses of vitamin D3 (6). We have directly measured free 25(OH)D in the participants of this study to answer this question: Does free 25(OH)D provide any information above and beyond total 25(OHD with respect to calcium absorption? We also examined the association of skeletal markers of vitamin D action with free 25(OH)D.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

This report is based on analysis of serum samples from a prior study of calcium absorption (6). Recruitment started in November 2010, and the study ended in March 2012. The study population was 75% white and 10% black, with the rest being self-declared as Asian or Hispanic. In this study, exclusion criteria included any chronic illness or any factor that influences calcium and vitamin D metabolism.

Protocol

Subjects had a baseline visit for screening. They returned for a randomization visit where calcium absorption was measured and medication was dispensed. After 8 weeks of supplementation, they returned for another visit (wk 10) where calcium absorption and baseline laboratory studies were repeated. They were randomly assigned to one of four groups, with each receiving either placebo or 20 μg (800 IU), 50 μg (2000 IU), or 100 μg (4000 IU) of vitamin D3 daily. A computer-generated block randomization was used.

Calcium absorption

Calcium absorption measurement was performed at baseline and again after 10 weeks. A dual-tracer isotope method was used to measure calcium absorption efficiency (7–11). The relative fraction of the oral, compared with the iv, dose in a 24-hour urine pool was determined and represented the fraction of the oral tracer dose that was absorbed. Samples were analyzed for isotopic enrichment using thermal ionization mass spectrometry as previously described (7). Analyses were performed in the laboratory of the USDA/ARS Children's Nutrition Research Center.

Laboratory analyses

The serum 25(OH)D was measured by a RIA from DiaSorin, Inc. Our laboratory participates in the Vitamin D External Quality Assessment Scheme, an external quality control program, and employs the National Institute of Standards and Technology standard. Serum 1,25(OH)2D was measured by enzyme immunoassay manufactured by Immuno Diagnostic System Ltd. The vitamin D tablets were assayed by HPLC (Waters Symmetry C18, 3.9 × 150-mm column; Waters Corp; mobile phase, acetonitrile and methanol [75:25]). Serum PTH was measured by the Immulite 2000 Analyzer for the quantitative measurement of Intact PTH (Diagnostic Products Corporation). Serum C-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen (CTX) was measured with a Serum Crosslaps ELISA kit made by Nordic Bioscience Diagnostics. Serum procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) was measured using a UniQ P1NP RIA kit from Orion Diagnostica.

Samples were sent to Future Diagnostics for free 25(OH)D testing. The free 25(OH)D ELISA is based on a two-step immunoassay procedure performed in a microtiter plate. During the first incubation step, free 25(OH)D [25(OH)D2 and -D3] is bound to the anti-vitamin D antibody coated on the wall of the microtiter plate. The in vivo equilibrium between free and bound 25(OH)D is minimally disturbed. After washing, a fixed amount of biotinylated 25(OH)D is added to each well. The nonbound biotinylated 25(OH)D is removed by washing, and a streptavidin peroxidase conjugate is added. In a next step, tetramethylbenzidine chromogenic substrate is added. Finally, the reaction is stopped by addition of Stop reagent, and the absorbance (A450 nm) is measured using a plate spectrophotometer. The concentration of free vitamin D in the sample is inversely proportional to the absorbance in each sample well.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (ie, mean, median, SD) of continuous clinical covariates and laboratory markers were generated to describe the sample of patients, both overall and within each treatment arm. Associations between continuous covariates were examined via Pearson correlation coefficients and linear regression models. Scatterplots of continuous variables were generated and presented along with estimated regression lines and model R2 values to describe the nature of the association. To facilitate comparison between models for total and free 25(OH)D, standardized regression coefficients were estimated based on models using normalized values of the independent and dependent variables. Bioavailable 25(OH)D was calculated as the sum of free 25(OH)D bound to albumin and free 25(OH)D measured directly (3). We include data on bioavailable 25(OH)D out of interest, but it is calculated from free and total 25(OH)D.

Results

Seventy-six subjects were randomly assigned to the four treatment groups, and 71 completed the study. There were no significant differences at baseline from the control group in age (60 ± 45 y), body mass index (26.2 ± 3.8 kg/m2), dietary calcium, serum 25(OH)D, calcium absorption, or serum albumin. Mean serum albumin in the control group was 4.32 ± 0.30 g/dL. The response to increased vitamin D dose is similar for both serum measures of vitamin D; as dose increases, 10-week serum 25(OH)D levels (free and total) increase. Table 1 shows the average levels of free and total 25(OH)D at baseline and follow-up; participants assigned to the 4000-IU dose arm had average 10-week total serum 25(OH)D levels of 40.4 ng/mL and free serum 25(OH)D levels of 10.4 pg/mL, compared to 23.7 ng/mL and 5.3 pg/mL, respectively, for those assigned to the placebo arm. After adjusting for baseline serum 25(OH)D levels, the relationship between assigned dose and 10-week free or total serum D level is consistent and strongly significant for both variables (P values < .001). Standardized estimates for the effect of assigned dose are 0.71 with 95% confidence interval (0.63, 0.91) for total serum 25(OH)D and 0.77 with 95% confidence interval (0.58, 0.83) for free serum 25(OH)D. Furthermore, dose level and baseline level of serum 25(OH)D account for the same amount of information (R2 = 0.72) in both models.

Table 1.

Average Levels of Free and Total 25(OH)D at Baseline and Follow-up

| Measurement | Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 19) | |||||

| Baseline | |||||

| Bioavailable D, ng/mL | 1.8 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 2.9 |

| Free vitamin D, pg/mL | 4.7 | 1.8 | 4.7 | 1.4 | 7.9 |

| Total 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 24.7 | 6.1 | 25.6 | 13.9 | 36.3 |

| Follow-up | |||||

| Bioavailable D, ng/mL | 2.1 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 3.1 |

| Free vitamin D, pg/mL | 5.3 | 1.5 | 5.2 | 2.6 | 7.6 |

| Total 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 23.7 | 5.9 | 22.9 | 14.6 | 33.8 |

| Dose, 800 IU (n = 19) | |||||

| Baseline | |||||

| Bioavailable D, ng/mL | 2.0 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 3.1 |

| Free vitamin D, pg/mL | 5.1 | 1.4 | 4.8 | 3.1 | 7.5 |

| Total 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 25.6 | 5.5 | 26.3 | 13.4 | 33.6 |

| Follow-up | |||||

| Bioavailable D, ng/mL | 2.6 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 3.6 |

| Free vitamin D, pg/mL | 6.4 | 1.3 | 6.6 | 3.4 | 8.8 |

| Total 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 28.2 | 6.2 | 26.8 | 18.9 | 37.9 |

| Dose, 2000 IU (n = 20) | |||||

| Baseline | |||||

| Bioavailable D, ng/mL | 1.9 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 3.0 |

| Free vitamin D, pg/mL | 1.3 | 1.3 | 5.1 | 2.6 | 7.4 |

| Total 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 25.9 | 6.1 | 26.8 | 13.1 | 34.5 |

| Follow-up | |||||

| Bioavailable D, ng/mL | 2.8 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 4.0 |

| Free vitamin D, pg/mL | 7.1 | 1.3 | 7.1 | 4.2 | 9.7 |

| Total 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 33.7 | 4.2 | 34.4 | 24.4 | 39.6 |

| Dose, 4000 IU (n = 18) | |||||

| Baseline | |||||

| Bioavailable D, ng/mL | 2.2 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 3.2 |

| Free vitamin D, pg/mL | 5.4 | 1.5 | 5.7 | 2.4 | 7.7 |

| Total 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 24.9 | 5.7 | 26.2 | 14.7 | 33.2 |

| Follow-up | |||||

| Bioavailable D, ng/mL | 4.1 | 0.6 | 4.2 | 3.1 | 5.4 |

| Free vitamin D, pg/mL | 10.4 | 1.4 | 10.2 | 8.2 | 13.2 |

| Total 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 40.4 | 7.7 | 39.7 | 28.2 | 51.9 |

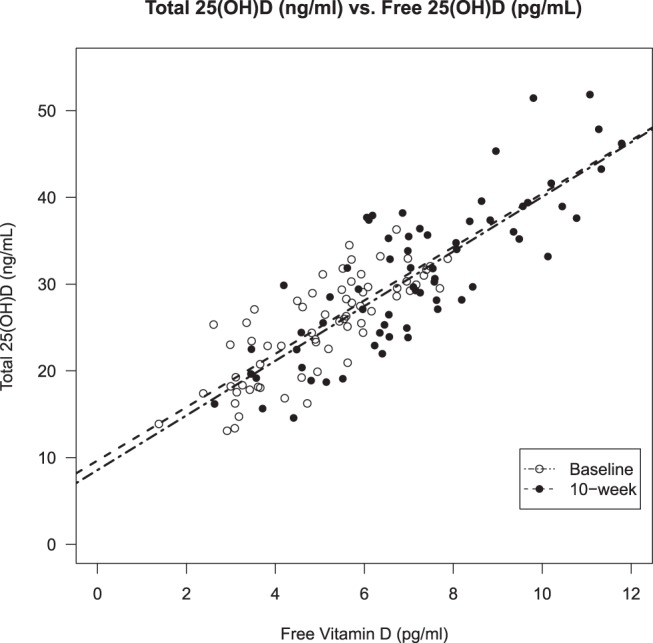

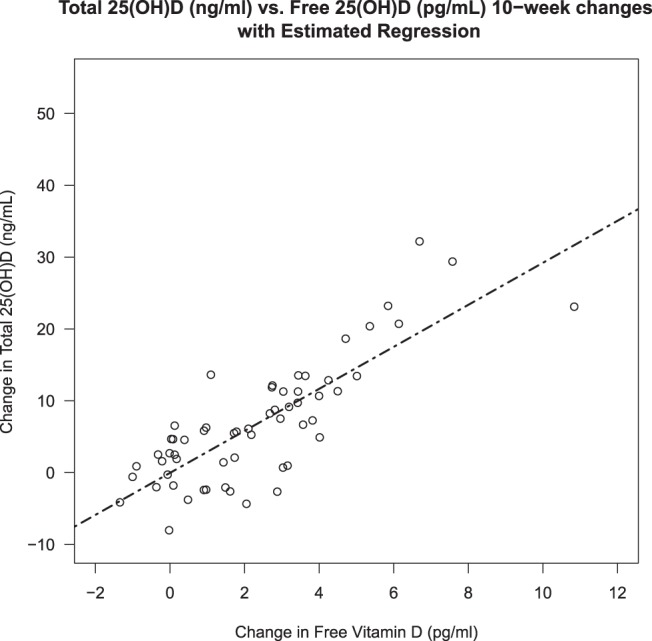

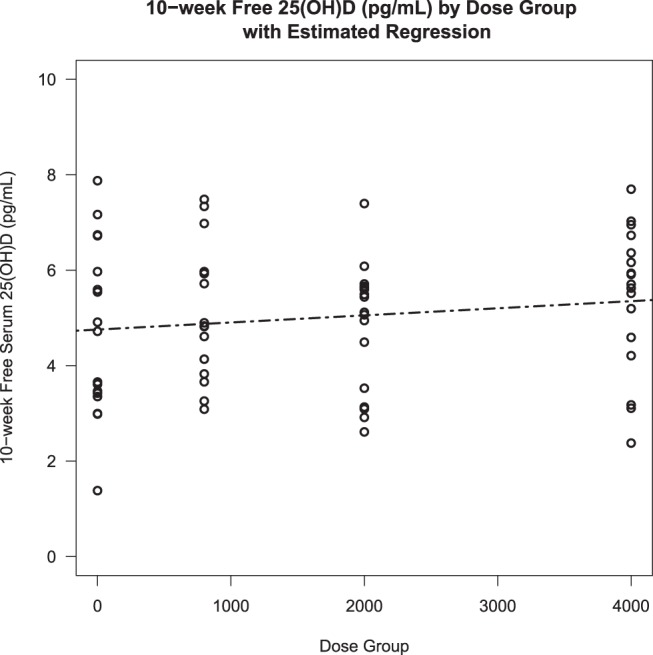

Figure 1 illustrates the strong linear relationship between free and total serum 25(OH)D levels both at baseline and after increasing vitamin D intake (correlation = 0.80 and 0.83, respectively). Similarly, Figure 2 shows the strong relationship between changes at 10 weeks between free and total serum 25(OH)D (correlation = 0.81). Given these high correlations, adjustment for both free and total serum D levels to reduce observed variation in markers such as PTH, CTX, serum calcium, or calcium absorption is not warranted. In Figure 3, the increase in serum free 25(OH)D by increasing doses of vitamin D is depicted. This response is similar to that previously reported for total 25(OH)D.

Figure 1.

Total 25(OH)D (ng/mL) vs free 25(OH)D (pg/mL).

Figure 2.

Total 25(OH)D (ng/mL) vs free 25(OH)D (pg/mL) 10-week changes with estimated regression.

Figure 3.

Ten-week free 25(OH)D (pg/mL) by dose group with estimated regression.

Tables 2 and 3 provide correlations between free and total serum 25(OH)D levels and 10-week changes in these markers and other biomarkers of interest. In Table 3, the close correlation between total 25(OH)D and free 25(OH)D at both baseline and follow-up is noted again. Calcium absorption is not correlated with total or free 25(OH)D in this sample, nor is there a significant correlation with serum 1,25(OH)2D at baseline. The correlation at the final visit with the change in dose of vitamin D is of interest.

Table 2.

Dose-Response Models

| Follow-up | Slope (SE) for Baseline Levels | Slope (SE) for Dose | Standardized Slope for Baseline Levels | Standardized Slope for Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioavailable D, ng/mL | 0.44 (0.13) | 0.47 (0.05) | 0.28 (0.079) | 0.71 (0.081) |

| Free vitamin D, pg/mL | 0.38 (0.11) | 1.21 (0.11) | 0.25 (0.073) | 0.77 (0.07) |

| Total vitamin D, ng/mL | 0.65 (0.10) | 4.14 (0.37) | 0.43 (0.063) | 0.71 (0.063) |

Dose is equal to 0 (placebo), 0.8 (800 IU), 2.0 (2000 IU), or 4.0 (4000 IU).

Table 3.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients Between Markers

| Baseline Visit |

10-Week Visit |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total 25(OH)D | Free 25(OH)D | Bioavailable D | Total 25(OH)D | Free 25(OH)D | Bioavailable D | |

| Total 25(OH)D | 1.00000 | 0.79550a | 0.74289a | 1.00000 | 0.82566a | 0.78473a |

| Free 25(OH)D | 0.79550a | 1.00000 | 0.95464a | 0.82566a | 1.00000 | 0.97583a |

| Bioavailable D | 0.74289a | 0.95464a | 1.00000 | 0.78473a | 0.97583a | 1.00000 |

| Albumin | −0.06625 | −0.07026 | 0.22354 | 0.05423 | 0.00729 | 0.13988 |

| Calcium absorption | 0.04032 | 0.01708 | 0.02018 | 0.11318 | 0.21659 | 0.20799 |

| PTH | −0.23154b | −0.22894 | −0.29583b | −0.26515b | −0.21234 | −0.29174b |

| CTX | −0.01828 | −0.03429 | −0.01853 | 0.23645b | 0.23546 | 0.22708 |

| 1,25(OH)2D | 0.17432 | 0.10819 | 0.12164 | 0.31137b | 0.25933b | 0.25762b |

| P1NP | −0.08606 | −0.12878 | −0.09328 | 0.13763 | 0.11958 | 0.14169 |

| Serum calcium | 0.14591 | −0.01116 | 0.04081 | 0.09598 | 0.05234 | 0.14326 |

P value < .001.

P value < .05.

PTH is negatively correlated with total 25(OH)D (rho = −0.23 and −0.27 at baseline and follow-up, respectively) and similarly for free 25(OH)D (rho = −0.23 and −0.21 at baseline and follow-up, respectively). Serum CTX had a moderate positive correlation with total and free 25(OH)D at follow-up (however, not at baseline), and P1NP was not associated with free or total serum 25(OH)D. Correlations between the changes in markers are of interest. Close correlation between the change in free 25(OH)D with the change in total 25(OH)D is of note (r = 0.81; P < .001). Serum PTH decreased with the increase in total 25(OH)D and free 25(OH)D. However, these correlations were not statistically significant, and the changes in 1,25(OH)2D increased significantly with the change in total 25(OH)D (r = 0.25; P < .05) but not with free 25(OH)D. No racial differences were observed with respect to the correlations between serum total or free 25(OH)D and other biomarkers at baseline or follow-up or for both visits in the model.

Discussion

In this study of the response of calcium absorption to increasing doses of vitamin D, there was no advantage of measuring free over total 25(OH)D. The close correlation between total and free 25(OH)D at baseline was confirmed, and importantly, the change in free 25(OH)D in response to vitamin D intake correlated closely with the change in total 25(OH)D. This suggests that because free 25(OH)D behaves similarly in dose response, it may also be used as a biomarker of nutritional status of vitamin D. However, it is clear that in this healthy population, free 25(OH)D does not provide additional information over total 25(OH)D. The suggestion by some that previous nutritional studies using total 25(OH)D need to be repeated with free 25(OH)D does not appear to be meritorious. The major determinant of free 25(OH)D in our models is total 25(OH)D. We included data on bioavailable 25(OH)D out of interest, realizing that it is calculated from free and total 25(OH)D in the study and, therefore, would not be expected to provide additional information. Clinically, free 25(OH)D measurement may prove useful when there is alteration of VDBPs such as issues in pregnancy, cirrhosis, acute illness, hypoalbuminemia, or sex hormone use (12–15).

A special consideration, however, is race. People of African ancestry have genetic polymorphisms that result in lower concentrations of VDBP (3). Thus, although they have lower total 25(OH)D, the free 25(OH)D levels of African Americans are the same as in white Americans. This may explain the paradox whereby African Americans have lower total 25(OH)D but still have superior bone health. It could be argued that our findings suggest that free 25(OH)D should be measured in African Americans to avoid their overtreatment. This suggestion is premature until further studies are completed of the extraskeletal actions of vitamin D. Large clinical trials are under way to examine these questions (16).

Our study tests the hypothesis that free 25(OH)D might better reflect a canonical action of vitamin D, ie, calcium absorption. Free 25(OH)D did not differ from total 25(OH)D in the small increase observed in calcium absorption. A caveat is that the average 25(OH)D in this study was similar to that seen in a healthy American population. As a result, we do not have sufficient data to comment on these relationships in individuals who are vitamin D deficient.

The relationships with the other biomarkers of vitamin D action also do not support that free 25(OH)D reflects vitamin D action better than total 25(OH)D. Of particular relevance is the decline in PTH that is seen with increasing serum levels of total 25(OH)D. This relationship was statistically significant for total 25(OH)D but not for free 25(OH)D. It would have been of interest if the change in free 25(OH)D had a greater correlation with the observed change in PTH than total 25(OH)D, but our findings suggest that in healthy individuals free 25(OH)D does not offer additional information concerning this relationship. The correlation between total 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D is expected because it is the bound 25(OH)D that interacts with megalin in the renal synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D. The change in CTX corresponding to the change in 25(OH)D is also expected because of the resorptive action of vitamin D. However, we did not study any extraskeletal actions of vitamin D where it is expected that cellular effects could be dependent on free 25(OH)D, specifically those involving the immune system. Further studies aimed at the extraskeletal actions of vitamin D are warranted and are in progress (16).

We are aware of several weaknesses in this study. Most importantly, our subjects were not severely vitamin D deficient. We do not know whether free 25(OH)D would prove a more robust measurement in the deficient state, and studies with low baseline 25(OH)D do need to be done. Our study also concentrated on the skeletal effects of vitamin D, PTH, and bone markers and especially calcium absorption. Free 25(OH)D would be expected to be a major factor in extraskeletal effects, and this proposition needs to be established.

In conclusion, we have observed in healthy individuals that free 25(OH)D mirrors total 25(OH)D in calcium absorption. We found little to suggest that free 25(OH)D would be a more useful measurement in healthy individuals unless a binding protein abnormality was present. The preferred use of serum free 25(OH)D assay in African Americans remains to be elucidated, as does the role of free 25(OH)D in extraskeletal tissues. A normative database for free 25(OH)D needs to be developed, and its usefulness in various abnormalities of VDBP needs to be explored further. Studies must also be done on the assay methodology itself to ensure standardization.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-AG032440–01A2.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- CTX

- C-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen

- 1,25(OH)2D

- 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D

- 25(OH)D

- 25-hydroxyvitamin D

- P1NP

- procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide

- VDBP

- vitamin D binding protein.

References

- 1. Bikle DD, Gee E, Halloran B, Kowalski MA, Ryzen E, Haddad JG. Assessment of the free fraction of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in serum and its regulation by albumin and the vitamin D-binding protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63(4):954–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chun RF, Peercy BE, Orwoll ES, Nielson CM, Adams JS, Hewison M. Vitamin D and DBP: the free hormone hypothesis revisited. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;144:132–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Powe CE, Evans MK, Wenger J, et al. Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D status of black Americans and white Americans. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(21):1991–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aloia JF. African Americans, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and osteoporosis: a paradox. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(2):545S–550S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ponda MP, McGee D, Breslow JL. Vitamin D-binding protein levels do not influence the effect of vitamin D repletion on serum PTH and calcium: data from a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(7):2494–2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aloia JF, Dhaliwal R, Shieh A, et al. Vitamin D supplementation increases calcium absorption without a threshold effect. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(3):624–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abrams SA. Using stable isotopes to assess mineral absorption and utilization by children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(6):955–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Griffin IJ, Abrams SA. Methodological considerations in measuring human calcium absorption: relevance to study the effects of inulin-type fructans. Br J Nutr. 2005;93(suppl 1):S105–S110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abrams SA, Griffin IJ, Hawthorne KM, Gunn SK, Gundberg CM, Carpenter TO. Relationships among vitamin D levels, parathyroid hormone, and calcium absorption in young adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(10):5576–5581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abrams SA, Copeland KC, Gunn SK, Stuff JE, Clarke LL, Ellis KJ. Calcium absorption and kinetics are similar in 7- and 8-year-old Mexican-American and Caucasian girls despite hormonal differences. J Nutr. 1999;129(3):666–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abrams SA, Copeland KC, Gunn SK, Gundberg CM, Klein KO, Ellis KJ. Calcium absorption, bone mass accumulation, and kinetics increase during early pubertal development in girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(5):1805–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schwartz JB, Lai J, Lizaola B, et al. A comparison of measured and calculated free 25(OH) vitamin D levels in clinical populations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(5):1631–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schwartz JB, Lai J, Lizaola B, et al. Variability in free 25(OH) vitamin D levels in clinical populations. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;144:156–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bikle DD, Halloran BP, Gee E, Ryzen E, Haddad JG. Free 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels are normal in subjects with liver disease and reduced total 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. J Clin Invest. 1986;78(3):748–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bikle DD, Gee E, Halloran B, Haddad JG. Free 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels in serum from normal subjects, pregnant subjects, and subjects with liver disease. J Clin Invest. 1984;74(6):1966–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Manson J.E., Bassuk S.S. Vitamin D research and clinical practice: at a crossroads. JAMA. 2015;313(13):1311–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]