Abstract

Context:

Children with the most common and severe type of congenital hyperinsulinism (HI) frequently require pancreatectomy to control the hypoglycemia. Pancreatectomy increases the risk for diabetes, whereas recurrent hypoglycemia places children at risk of neurocognitive dysfunction. The prevalence of these complications is not well defined.

Objective:

The objective was to determine the prevalence of diabetes and neurobehavioral deficits in surgically treated HI.

Design:

This was designed as a cross-sectional study of individuals who underwent pancreatectomy for HI between 1960 and 2008.

Outcomes:

Diabetes outcomes were assessed through patient interview and medical record review. Neurobehavioral outcomes were assessed through the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 2nd edition (ABAS-II), and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).

Results:

A total of 121 subjects were enrolled in the study at a median age of 8.9 years (range, 3.5–50.7 y). Thirty-six percent (44 of 121) of subjects had diabetes. Nine subjects developed diabetes immediately after pancreatectomy. Of the remaining 35 subjects who developed diabetes, the median age at diabetes diagnosis was 7.7 years (range, 8 mo to 43 y). In subjects with diabetes, the median hemoglobin A1c was 7.4% (range, 6.5–12.6%), and 38 (86%) subjects required insulin. Subjects with diabetes had a greater percentage of pancreatectomy than subjects without diabetes (95% [range, 65–98] vs 65% [1–98]). Neurobehavioral abnormalities were reported in 58 (48%) subjects. Nineteen (28%) subjects had abnormal ABAS-II scores, and 10 (16%) subjects had abnormal CBCL scores.

Conclusions:

Children, who undergo near-total pancreatectomy are at high risk of developing diabetes. Neurobehavioral deficits are common, and developmental assessment is essential for children with HI.

Congenital hyperinsulinism (HI) is the leading cause of persistent hypoglycemia in infants and children. Inactivating mutations of the β-cell ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel, encoded by ABCC8 and KCNJ11, result in the most common and severe form of HI (1, 2). Available drugs to treat HI are frequently ineffective for the treatment of KATP HI, and therefore, children may require pancreatectomy to control the hypoglycemia. There are two distinct forms of KATP HI: the diffuse disease, in which β-cells throughout the pancreas show hyperactivity; and the focal disease, which is characterized by a discrete lesion of islet cell hyperplasia or adenomatosis (3–5). Children with diffuse HI require near-total pancreatectomy, which is palliative, and they frequently continue to have hypoglycemia, albeit milder, after surgery (6). In contrast, children with focal HI can be cured if the lesion is resected. Elucidation of the molecular genetics of these two forms in the 1990s and the advent of the 18-fluoro L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (18F DOPA) positron emission tomography (PET) scan in the early 2000s allowed for more accurate differentiation of diffuse from focal disease, as well as preoperative localization of focal lesions (7–10). Prior to that time, patients with focal HI frequently underwent more extensive pancreatic resections or near-total pancreatectomies (11, 12).

Long-term complications of HI and its treatment are a consideration when treatment decisions are made. Without timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment, children with HI are exposed to recurrent hypoglycemia, which may result in neurological injury. Additionally, pancreatectomy places children at risk of diabetes later in life. The prevalence of these complications has not been well defined.

Existing reports of long-term glucose metabolism have small sample sizes and find conflicting results (13, 14). The largest study consisting of 114 children in Germany found a 27% incidence of diabetes after pancreatectomy but did not differentiate between diffuse and focal HI (15). In their study of 105 patients with HI who underwent pancreatectomy, Beltrand et al (16) found that no patients with focal disease required antidiabetic treatment, but 91% of patients with diffuse HI required insulin by age 14 years.

In the 1980s, studies found that up to 50% of children with HI had neurological dysfunction (17). It is unclear whether recent advances in diagnosis and more aggressive interventions have improved the neurodevelopmental outcomes of children with HI. Recent studies have found rates of neurodevelopmental abnormalities ranging from 26–46% and rates of epilepsy ranging from 25–43% (18, 19). Children with surgical HI appear to be at higher risk of poor neurological outcomes than children with medically manageable HI. Steinkrauss et al (20) found that children requiring pancreatectomies had higher rates of abnormal development than patients who received medical management.

Our aim is to determine the prevalence of diabetes and neurobehavioral problems in children with surgically treated HI and to identify risk factors for these complications.

Subjects and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted of individuals who underwent pancreatectomy for HI between 1960 and 2008 and received care at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). A diagnosis of HI was made with biochemical evidence of insulin excess: detectable insulin level and/or suppressed β-hydroxybutyrate at the time of hypoglycemia (plasma glucose < 50 mg/dL) and/or an inappropriate rise in glucose of > 30 mg/dL over 40 minutes after receiving 1 mg glucagon. Clinical data were gathered through patient or parent interview and medical record review. Subjects were considered to have diabetes if they had any of the following: fasting glucose > 126 mg/dL, a glucose > 200 mg/dL at 2 hours with an oral glucose tolerance test, hemoglobin A1c > 6.5%, or if they were receiving insulin or oral antidiabetic treatment. This study was approved by the CHOP Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Neurocognitive outcomes were assessed through two self- or parental-administered instruments: the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 2nd edition (ABAS-II) and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). The ABAS-II assesses adaptive behavior and is available for all ages (21–23). The General Adaptive Composite (GAC) score is the main outcome score of the ABAS-II and has a mean of 100 with SD of 15. Lower scores indicate worse outcomes. The CBCL assesses emotional and social functioning and is available for subjects who are ≤ 18 years old (24, 25). The total problem (TP) score is the main outcome score for the CBCL, and it has a mean of 50 with a SD of 10. Higher scores indicate worse outcome.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics as well as various outcomes of interest were summarized by standard descriptive statistics. Histograms and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test were used to assess normality of distribution of continuous variables (eg, neurobehavioral outcomes). For comparisons of continuous variables of interest between various naturally occurring subgroups (eg, diffuse vs focal HI, subjects with diabetes vs those without diabetes), t-tests were used to compare means of normally distributed data, and Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare medians of nonparametric outcome data. χ2 or Fisher's exact tests were used to examine associations between subgroups and categorical variables.

Scores on the neurobehavioral screening tests were considered abnormal if they were more than 1 SD below the mean for GAC score or more than 1 SD above the mean for TP score. To examine differences in proportion of subjects with abnormal scores, GAC and TP scores were converted to z-scores, which reflect the number of SD values that a score is above or below the population mean. One-sample z-tests of proportions were used to examine differences between the observed proportion of subjects and the expected proportions in a normal distribution.

Results

Subjects

A total of 258 individuals underwent pancreatectomy between 1960 and 2008 and received care at the CHOP. A total of 121 subjects were enrolled in the study, 133 subjects were unable to be contacted, and four declined to participate. Sixty-nine subjects completed the ABAS-II, and 62 subjects completed the CBCL. The median age of subjects at enrollment in the study was 8.9 years (range, 3.5–50.7 y), and 53% were female (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| Age, y | 8.9 (3.5–50.7) |

|---|---|

| Female, % | 53 |

| Presentation | |

| Gestational age, wk | 39 (33–41) |

| History of prematurity, %a | 16 |

| Birth weight, g | 3884 ± 702 |

| Age at presentation, d | 0 (0–477) |

| Seizures at presentation, % | 44 |

| Age at HI diagnosis, d | 11 (0–730) |

| Genetics | |

| ABCC8 | 93 (77) |

| KCNJ11 | 4 (3) |

| GLUD1 | 2 (2) |

| GCK | 1 (1) |

| Negative | 16 (13) |

| Not tested | 5 (4) |

Data are expressed as number (percentage) or median (range) unless stated otherwise.

Defined as ≤ 36 weeks.

Surgical history

The median age at initial pancreatectomy was 1.7 months (range, 0.2–144). Thirteen of 121 (11%) subjects underwent additional pancreatic resections for persistent hypoglycemia. The median extent pancreatectomy was 95% (range, 1–99%). Histological examination of the pancreas revealed diffuse HI in 49% (59 of 121) of subjects and focal HI in 45% (54 of 121). In 6% of subjects (seven of 121), histology was not consistent with either diffuse or focal disease. Of these seven children, six had histology consistent with localized islet nuclear enlargement, and one had normal histology. Pathology was not available on one subject who underwent pancreatectomy in the 1960s. Subjects with diffuse HI had a significantly greater percentage of pancreatectomy than those with focal HI (95% [range, 75–99%] vs 50% [1–98%]; P < .0005). Of the 11 subjects with focal disease who had a greater than 95% pancreatectomy, all except one underwent pancreatectomy before the advent of the 18F DOPA PET scan.

Development of diabetes

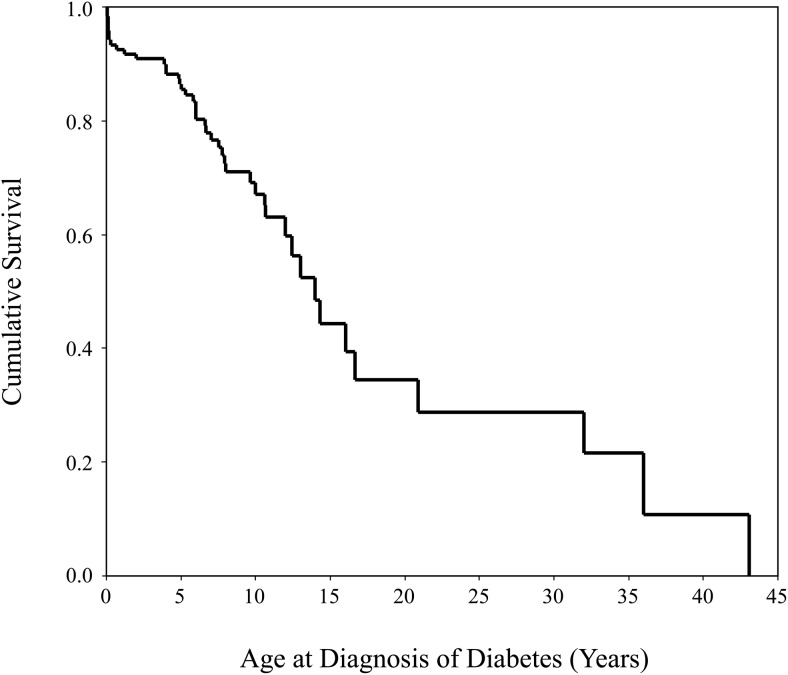

Thirty-six percent (44 of 121) of subjects had diabetes. Nine subjects developed hyperglycemia in the postoperative period after pancreatectomy and had a persistent insulin requirement. Of the 35 subjects who developed diabetes outside of the postoperative period, the median age at diabetes diagnosis was 7.7 years (range, 8 mo to 43 y) (Figure 1). The proportion with diabetes increased with age (Table 2). The median hemoglobin A1c at the time of study enrollment was 7.4% (range, 6.5–12.6%). Eighty-six percent (38 of 44) of subjects with diabetes required insulin. Five subjects were on oral antidiabetic medications: four were treated with metformin, and one was on a sulfonylurea and a thiazolidinedione. One subject used diet modifications alone for glycemic control.

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier survival curve showing the age at diabetes diagnosis in subjects with diabetes.

Table 2.

Proportion of Subjects with Diabetes by Age Group

| Age Group | Diabetes | No Diabetes | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| <10 y | 19 | 56 | 25 |

| 10–20 y | 17 | 19 | 47 |

| >20 y | 8 | 2 | 80 |

The median percentage pancreatectomy was greater in subjects who developed diabetes compared to those who did not develop diabetes (97% [range, 65–100%] vs 65% [1–100%]; P < .0005). Ninety-three percent (41 of 44) of subjects who developed diabetes had ≥ 95% pancreatectomy. The other three subjects with diabetes had 65, 75, and 90% pancreatectomies, respectively, and developed noninsulin-dependent diabetes at ages 36, 43, and 32 years.

Subjects with diabetes were more likely to have a history of diffuse HI than focal HI (84 vs 14%; P < .0005). The six subjects with focal HI who developed diabetes had ≥ 97% pancreatectomies, and all except one subject underwent surgery before 18F DOPA PET scan became available.

Neurobehavioral outcomes

Neurobehavioral problems were reported in 48% (58 of 121) of the study population. Psychiatric/behavioral problems and speech delay were the most common abnormalities reported (Table 3). Only 24% of subjects report having undergone formal neurocognitive testing. There were no associations between parent reported neurobehavioral problems and age at enrollment, age at presentation, seizures at presentation, age at surgery, histology, or HI genetics.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Reported Neurobehavioral Abnormalities

| Psychiatric/behavioral | 25 (21) |

|---|---|

| Speech delay | 22 (18) |

| Learning disability | 19 (16) |

| Seizures | 16 (13) |

| Physical disability | 13 (11) |

| ADHD | 12 (10) |

| Autism | 2 (2) |

| Total | 58 (48) |

Data are expressed as number (percentage).

Fifty-seven percent (69 of 121) of subjects completed the ABAS-II. Their median age was 9.1 years (range, 3.5–50.7 y), and 49% were female. The mean GAC score was 96 ± 25 (Table 4). The proportion of subjects scoring more than 1 SD below the mean was significantly greater than in the general population (27.5 vs 15.8%; P = .008), as was the proportion scoring more than 2 SD below the mean (18.8 vs 2.2%; P < .0005). Subjects scoring more than 1 SD below the mean were more likely to have reported neurobehavioral problems.

Table 4.

Neurobehavioral Measures

| ABAS-II (n = 69)a | Mean ± SD | % < 1 SD | % < 2 SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAC score | 96 ± 25 | 27.5d | 18.8e |

| Conceptual composite score | 98 ± 22 | 21.2 | 11.8e |

| Social composite score | 100 ± 21 | 22.1 | 14.7e |

| Practical composite score | 92 ± 25 | 30.9e | 16.2e |

| CBCL (n = 62)b | % > 1 SD | % > 2 SD | |

| TP score | 49 ± 16 | 16.1 | 8.1d |

| Internalizing problems | 49 ± 13 | 16.1 | 9.7e |

| Externalizing problems | 47 ± 11 | 11.5 | 6.5c |

Normal population mean is 100 with SD of 15; higher scores are more favorable.

Normal population mean is 50 with SD of 10; lower scores are more favorable.

P < .02;

P < .01;

P < .001, compared to normal population.

Fifty-seven percent (62 of 109 eligible subjects) completed the CBCL. Their median age was 8.6 years (range, 3.5–17.3 y), and 48% were female. The mean TP score was 49 ± 16 (Table 3). The proportion of subjects scoring more than 1 SD above the mean was not significantly different than the general population (P = .94; 16.1 vs 15.8), but the proportion scoring > 2 SD above the mean was significantly greater than in the general population (8.1 vs 2.2%; P = .002). Subjects scoring more than 1 SD above the mean were more likely to have reported neurobehavioral problems.

Subjects with diffuse HI had worse outcomes on the neurobehavioral measures than those with focal disease. Subjects with diffuse HI were more likely than those with focal HI to have GAC scores > 2 SD below the mean (9 vs 2; P = .02) and an internalizing problem score > 1 SD above the mean on the CBCL (8 vs 2; P = .016). There were no associations between outcomes on the neurobehavioral measures and age at enrollment, age at presentation, seizures at presentation, age at surgery, or HI genetics.

The cohort was divided into those diagnosed before December 2004 and those diagnosed in December 2004 and later, when 18F DOPA PET imaging was established at CHOP. Between the two groups, there were no differences in mean GAC scores, mean TP scores, proportion with abnormal GAC or TP score, or proportion with a reported neurobehavioral problem.

Discussion

The management of congenital HI is challenging, particularly for children who fail to respond to medical therapy. To avoid recurrent and severe hypoglycemia, pancreatectomy is often their only option. Although children with focal HI are cured with partial pancreatic resection, children with diffuse HI require near-total pancreatectomies, which places them at high risk of diabetes.

Our study found that 36% of individuals with surgically treated HI had developed diabetes. Although a significant number of subjects (20%) developed hyperglycemia and a permanent insulin requirement in the postoperative period, the majority developed diabetes later in life. The median age at diabetes diagnosis was 7.7 years, and all except three subjects developed diabetes during the first two decades of life. Although our study cohort was young, one-fourth of the subjects less than 10 years old had developed diabetes. These findings are consistent with the results of another large study, which found that 42% of children with surgically managed diffuse HI were insulin dependent by 8 years of age (16). Arya et al (26) found in their study of 45 children with diffuse HI requiring near-total pancreatectomy that 70% required insulin by 7 years of age. Our study confirms the high rate of progression to diabetes and insulin dependence in the first decade of life. Starting within the first few years of life, children who undergo near-total pancreatectomy should be screened for diabetes. Parents also should be appropriately counseled on the risk of progression to diabetes.

As expected, most subjects with diabetes were insulin dependent. Six subjects were on oral antidiabetic medications or used dietary modifications to control their diabetes. We would not expect oral medications to be effective after pancreatectomy. However, three of these subjects developed diabetes in their thirties and forties and had 65–90% pancreatectomies, which raises the possibility that they may have a combination of impaired insulin secretion and insulin resistance secondary to age and elevated body mass index. Two of these three subjects had a body mass index greater than 25 kg/m2.

In their 1998 study of 53 patients who underwent > 70% pancreatectomy, Lovvorn et al (11) found diabetes had developed in seven subjects with diffuse disease and no subjects with focal disease, leading them to conclude that the risk of diabetes was likely associated with underlying pathology and not the extent of pancreatectomy. Our findings suggest otherwise. Of the focal subjects who developed diabetes, all had ≥ 97% pancreatectomies, and all but one underwent surgery at the time when recognition and localization of focal lesions were limited. Therefore, we conclude that the risk of diabetes results primarily from the degree of pancreatectomy. Our study speaks to the importance of identifying and appropriately treating children with focal HI who can be cured with partial pancreatic resection. With appropriate localization and resection of the lesion, children with focal HI may avoid the risk of diabetes that occurs with near-total pancreatectomies.

Neurobehavioral abnormalities are common in individuals with HI, likely due to recurrent hypoglycemia during a crucial period of brain development. Timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment are essential to limit exposure to hypoglycemia and the risk of neurological injury. Parents report high rates of neurobehavioral dysfunction, and the results from the ABAS-II and CBCL showed that a significant proportion of subjects were severely affected neurologically. Despite the high rate of neurobehavioral dysfunction, only one-fourth of subjects reported receiving a formal neurocognitive assessment. Many subjects with neurobehavioral issues were only identified after struggling academically in school. Given the high rate of neurobehavioral issues, all children with HI should receive neurocognitive evaluation.

Our study demonstrates that despite significant advances in the field, children with HI continue to have a high risk of neurocognitive abnormalities. In 1971, Harken et al (27) reported that six of 10 patients with HI who underwent pancreatectomy were developmentally delayed. In 1976, Stanley and Baker (28) found that 36% of patients with HI were delayed. A larger study of 90 patients published in 2001 reported that 26% of subjects had abnormal development, and 18% had epilepsy (19). Our study found very similar rates of neurobehavioral dysfunction: 27.5% of subjects scored abnormally on the ABAS-II, our developmental measure; and 13% of subjects have chronic seizures. Our study also compared neurobehavioral outcomes in subjects diagnosed before 2004 and after 2004. Despite receiving the benefits of advances in the field of HI, the group diagnosed after 2004 had the same neurobehavioral outcomes as the group before 2004. This finding suggests that the neurological insult from hypoglycemia occurs in the first several days of life before diagnosis and treatment.

There are several limitations to our study. It is cross-sectional and not longitudinal, so the incidence of diabetes and neurobehavioral problems could not be determined. We also gathered data through subject/parent interviews, although we also reviewed current medical records whenever possible. Our neurobehavioral testing was through self or parent assessment and not through formal neurocognitive testing of our study subjects. Although neurobehavioral problems were reported in nearly half of subjects, only 27.5% of subjects had abnormal scores on the ABAS-II and 16.1% on the CBCL. This discrepancy makes determining the exact prevalence of neurobehavioral dysfunction difficult. The difference between reported problems and test scores may reflect overrating of a child's behavior and adaptive skills by parents. Additionally, only a proportion of subjects completed the neurobehavioral measures, and it is possible that parents of children with better neurological outcomes were more willing to complete measures. Formal neurocognitive testing with a larger sample is necessary to determine the exact prevalence of neurobehavioral dysfunction.

Despite these limitations, our study demonstrates the high rate of progression to diabetes in children who undergo near-total pancreatectomy and highlights the need for early diabetes screening in this population. New medical therapies for treatment of diffuse HI are essential, so that surgery may be avoided. We also found a high rate of neurobehavioral problems. Surprisingly, despite the incredible advances in the field, which have allowed for the identification and cure of focal cases, the neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with HI have not changed significantly. The fact that children with focal HI who are cured after surgery, as well as children with transient HI in whom the HI resolves spontaneously (29), suffer from neurodevelopmental deficits strongly suggests that the initial insult from recurrent hypoglycemia before diagnosis and treatment greatly contributes to the poor outcomes. Thus, early diagnosis and aggressive treatment of hypoglycemia is necessary to improve the long-term outcomes of children with HI. New guidelines published by the Pediatric Endocrine Society seek to improve the early identification of these children (30).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the patients and families who participated in this study as well as the hyperinsulinism team at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Hyperinsulinism Center.

This work was supported by the National Center for Research Resources (Grant UL1RR024134; to K.L.) and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Grants R01 DK098517, to D.D.D.L.; R37 DK056268, to C.A.S.; and T32-DK63688–09, to K.L.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- 18F DOPA

- 18-fluoro L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine

- HI

- hyperinsulinism

- KATP

- ATP-sensitive potassium

- PET

- positron emission tomography.

References

- 1. Thomas PM, Cote GJ, Wohllk N, et al. Mutations in the sulfonylurea receptor gene in familial persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. Science. 1995;268:426–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thomas P, Ye Y, Lightner E. Mutation of the pancreatic islet inward rectifier Kir6.2 also leads to familial persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1809–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Leon DD, Stanley CA. Pathophysiology of diffuse ATP-sensitive potassium channel hyperinsulinism. In: Stanley CA, De Leon DD, eds. Monogenic Hyperinsulinemic Hypoglycemia Disorders. 1st ed Vol 21 Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 2012:18–29. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rahier J, Fält K, Müntefering H, Becker K, Gepts W, Falkmer S. The basic structural lesion of persistent neonatal hypoglycaemia with hyperinsulinism: deficiency of pancreatic D cells or hyperactivity of B cells? Diabetologia. 1984;26:282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Lonlay P, Fournet JC, Rahier J, et al. Somatic deletion of the imprinted 11p15 region in sporadic persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy is specific of focal adenomatous hyperplasia and endorses partial pancreatectomy. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:802–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lord K, Dzata E, Snider KE, Gallagher PR, De León DD. Clinical presentation and management of children with diffuse and focal hyperinsulinism: a review of 223 cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E1786–E1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Verkarre V, Fournet JC, de Lonlay P, et al. Paternal mutation of the sulfonylurea receptor (SUR1) gene and maternal loss of 11p15 imprinted genes lead to persistent hyperinsulinism in focal adenomatous hyperplasia. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1286–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sempoux C, Capito C, Bellanné-Chantelot C, et al. Morphological mosaicism of the pancreatic islets: a novel anatomopathological form of persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3785–3793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hardy OT, Hernandez-Pampaloni M, Saffer JR, et al. Accuracy of [18F]fluorodopa positron emission tomography for diagnosing and localizing focal congenital hyperinsulinism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4706–4711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Otonkoski T, Näntö-Salonen K, Seppänen M, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of focal hyperinsulinism of infancy with [18F]-DOPA positron emission tomography. Diabetes. 2006;55:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lovvorn HN, 3rd, Nance ML, Ferry RJ, Jr, et al. Congenital hyperinsulinism and the surgeon: lessons learned over 35 years. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:786–792; discussion 792–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Adzick NS, Thornton PS, Stanley CA, Kaye RD, Ruchelli E. A multidisciplinary approach to the focal form of congenital hyperinsulinism leads to successful treatment by partial pancreatectomy. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:270–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leibowitz G, Glaser B, Higazi AA, Salameh M, Cerasi E, Landau H. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy (nesidioblastosis) in clinical remission: high incidence of diabetes mellitus and persistent β-cell dysfunction at long-term follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:386–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mercimek-Mahmutoglu S, Rami B, Feucht M, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with congenital hyperinsulinism in Austria. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2008;21:523–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meissner T, Wendel U, Burgard P, Schaetzle S, Mayatepek E. Long-term follow-up of 114 patients with congenital hyperinsulinism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2003;149:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beltrand J, Caquard M, Arnoux JB, et al. Glucose metabolism in 105 children and adolescents after pancreatectomy for congenital hyperinsulinism. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jacobs DG, Haka-Ikse K, Wesson DE, Filler RM, Sherwood G. Growth and development in patients operated on for islet cell dysplasia. J Pediatr Surg. 1986;21:1184–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ludwig A, Ziegenhorn K, Empting S, et al. Glucose metabolism and neurological outcome in congenital hyperinsulinism. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2011;20:45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Menni F, de Lonlay P, Sevin C, et al. Neurologic outcomes of 90 neonates and infants with persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Pediatrics. 2001;107:476–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Steinkrauss L, Lipman TH, Hendell CD, Gerdes M, Thornton PS, Stanley CA. Effects of hypoglycemia on developmental outcome in children with congenital hyperinsulinism. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20:109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harrison P, Oakland T. The Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harrison P, Oakland T. The Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS). 2nd ed San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harrison P, Oakland T. Technical report: Adaptive Behavior Assessment System. 2nd ed San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bérubé RL, Achenbach TM. Bibliography of Published Studies using Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA). Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arya VB, Senniappan S, Demirbilek H, et al. Pancreatic endocrine and exocrine function in children following near-total pancreatectomy for diffuse congenital hyperinsulinism. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harken AH, Filler RM, AvRuskin TW, Crigler JF., Jr The role of “total” pancreatectomy in the treatment of unremitting hypoglycemia of infancy. J Pediatr Surg. 1971;6:284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stanley CA, Baker L. Hyperinsulinism in infants and children: diagnosis and therapy. Adv Pediatr. 1976;23:315–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Avatapalle HB, Banerjee I, Shah S, et al. Abnormal neurodevelopmental outcomes are common in children with transient congenital hyperinsulinism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2013;4:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thornton PS, Stanley CA, De Leon DD, et al. Recommendations from the Pediatric Endocrine Society for evaluation and management of persistent hypoglycemia in neonates, infants, and children. J Pediatr. 2015;167:238–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]