Abstract

Context:

Obesity is associated with a pro-inflammatory state and relative hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Estrogen (E2) is a potential link between these phenomena because it exhibits negative feedback on gonadotropin secretion and also inhibits production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Objective:

We sought to examine the effect of estrogen priming on the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis in obesity.

Design, Setting, and Participants:

This was an interventional study at an academic center of 11 obese and 10 normal-weight (NW) women.

Intervention:

A frequent blood-sampling study and one month of daily urinary collection were performed before and after administration of transdermal estradiol 0.1 mg/d for one entire menstrual cycle.

Main Outcome Measures:

Serum LH and FSH before and after GnRH stimulation, and urinary estrogen and progesterone metabolites were measured.

Results:

E2 increased LH pulse amplitude and FSH response to GnRH (P = .048, and P < .03, respectively) in obese but not NW women. After E2 priming, ovulatory obese but not NW women had a 25% increase in luteal progesterone (P = .01). Obese women had significantly higher baseline IL-6, IL-10, TGF-β, and IL-12 compared with NW (all P < .05); these levels were reduced after E2 (−6% for IL-1β, −21% for IL-8, −5% for TGF-β, −5% for IL-12; all P < .05) in obese but not in NW women.

Conclusions:

E2 priming seems to improve hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis function and systemic inflammation in ovulatory, obese women. Reducing chronic inflammation at the pituitary level may decrease the burden of obesity on fertility.

It is estimated that by end of 2015 41% of U.S. adults will be obese, as defined by a body mass index (BMI) of greater than 30 kg/m2 (1). Female adult obesity is associated with menstrual cycle irregularities, ovulatory dysfunction, and high risk for obstetrical complications. The reproductive phenotype of obese women is worsened by further increases in BMI, and this is not only due to anovulation (2). Although the association of adiposity with reduced reproductive fitness is well documented, the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood.

Starting from the 1970s, studies have associated obesity with longer follicular phases and decreased serum gonadotropins and luteal progesterone (3). A detailed evaluation of daily hormones from 674 ovulatory cycles suggested that overweight and obese women excreted significantly less LH, FSH, and progesterone metabolites than did normal-weight (NW) women (4). This relative hypogonadotropic hypogonadism of obesity could be manifested by either central or peripheral defects within the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis. Several distinct lines of evidence point to a selective deficiency in LH pulse amplitude in obesity. An animal model of human obesity, the obese Zucker rat, exhibits attenuated LH pulse amplitude but has a preserved LH surge (5). Decreased LH pulse amplitude but unaffected LH pulse frequency is a hallmark of hypogonadism in obese men (6). Studies of ovulatory obese women conducted by our group suggest significant reductions in LH pulse amplitude but no change in LH pulse frequency compared with NW controls (7). In general, a pituitary (rather than a hypothalamic) site of action is favored when changes in LH pulse amplitude occur without a change in LH pulse frequency (8). Thus, the preponderance of published evidence suggests that the central HPO hormonal alterations observed in obesity are localized to the level of pituitary gland.

Studies controlling for endogenous hormones in women have revealed an attenuated LH and FSH response to GnRH after exogenous estrogen administration (9). Furthermore, mice lacking pituitary estrogen receptor alpha demonstrate infertility and disrupted LH secretion, reflecting a lack of estrogen negative feedback on the gonadotropes (10). Taken together, this suggests that the pituitary plays a prominent role in mediating estrogen negative feedback on gonadotropin secretion. Alterations in estrogen (E2) serum levels and pathophysiology are well described in obese women (11, 12). However, the relationship of obesity with E2 negative feedback on gonadotropin secretion is not well described. In contrast, multiple in vitro and clinical studies (13, 14) demonstrated that E2 administration results in significant changes in serum cytokines, including a reduction in proinflammatory cytokines and systemic inflammation. We hypothesized that the HPO axis would be more sensitive to estrogen negative feedback in obese women compared with NW controls. To test this hypothesis, we performed a proof-of-concept, mechanistic study to determine the effects of exogenous E2 priming in obese women.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Twenty-one regularly menstruating obese and NW women were recruited from the community through campus-wide advertisement and completed the study. The study was approved by Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (11–0293); a signed informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to participation. Study criteria included: 1) age 18–42 years; 2) obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) or normal (18–25 kg/m2) BMI; 3) history of regular menses every 25–40 days; and 4) normal baseline prolactin, TSH and blood count. BMI was calculated as measured weight in kilograms divided by the square of measured height in meters. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) was prospectively ruled out given that all participants were required to have regular menstrual cycles and were non-hirsute; we used the National Institutes of Health definition of PCOS, which includes oligomenorrhea as a central criterion. Participants were excluded if they had a positive screen for activated protein C resistance at screening, or any other contraindications to exogenous estrogen (including previous thromboembolic events or stroke, history of an estrogen-dependent tumor, active liver disease, undiagnosed abnormal uterine bleeding, hypertriglyceridemia), smoking, hypertension, used medication known to affect reproductive hormones, used exogenous sex steroids within the last 3 months, exercised more than 4 hours weekly, or were attempting pregnancy. One participant became pregnant in the third month of study; her urinary collection was excluded from the analysis. All participants had a baseline physical examination by study personnel and underwent all blood sampling at the Clinical and Translational Research Center of the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute. Pregnancy was excluded by a serum pregnancy test at the beginning of each month of testing.

Protocol

All women underwent an 8-hour, every-10-minute blood sampling session twice: at baseline and after 1 month of transdermal estrogen administration (Supplemental Figure 1). Each frequent blood sampling study was completed during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycles and included an iv administration of a physiologic, weight-based (75 ng/kg) bolus of GnRH (Lutrelef; Ferring) given at 6 hours (15). Each participant therefore had a 6-hour window to assess endogenous LH and FSH secretion prior to the administration of exogenous GnRH. Daily, first-morning voided urine was collected over the entire menstrual cycle for cycles 1 and 3 using previously described methodology (7).

Starting with day 1 of the next menstrual cycle after baseline, study participants were instructed to apply 0.1 mg/day transdermal estrogen patches (17β-estradiol, Climara; Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals). This dose of transdermal estrogen has been successfully used in young women in prior studies (16). The patch was changed every 84 hours to achieve stable blood levels (9) and applied for the duration of one entire menstrual cycle. On day 1 of menses 3, the patch was discontinued and participants were scheduled for postintervention studies. If participants did not initiate a menstrual period after 40 days on the patch, it was discontinued and they were instructed to take daily oral progestin for 10 days. Postintervention studies were performed after menses 3, with an identical frequent blood sampling session and daily urinary collection as in cycle 1. All participants also underwent a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan (Hologic Discovery W; Apex 4.0.1) at baseline to evaluate body composition. Total body scans were analyzed for total fat mass and fat-free mass, and regional (ie, legs, arms, and trunk) fat mass.

Hormone assays

Serum LH and FSH were measured using a solid-phase, two-site-specific immunofluorometric assay (DELFIA; PerkinElmer) (7). Interassay and intra-assay coefficients of variation were 4.8 and 5.4% for LH, and 6.3 and 4.2% for FSH. Ligand Assay and Analysis Core services (University of Virginia) were used to assay Inhibin A, Inhibin B, and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) using commercial two-site ELISA assays (Beckman Coulter). Daily urine samples were assayed for estrone conjugates (E1c) and pregnanediol glucuronide (Pdg) (17). See Supplemental Materials and Methods for more details.

Cytokines

Serum proinflammatory cytokine levels were determined using a custom-made 10-cytokine array kit (RayBiotech) per the manufacturer's instructions. The array included the following cytokines: IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, TNF-α, TGF-β, resistin, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1). While most of the cytokines that were selected have clear predominant proinflammatory properties, two chosen cytokines, IL-10 and TGF-β, have mixed actions on inflammation. IL-10 has well-documented numerous anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive activities, but also has some immunostimulatory effects on CD4, CD8 T cells, and/or natural killer cells that may result in increased interferon-gamma production (18). TGF-β also has a well-known tumor suppressive role but also in monocytes, TGF-β has been shown to promote expression of proinflammatory mediators including IL-1 and IL-6 (19). Both TGF-β and IL-10 were selected in our panel to examine their respective trends in response to estradiol in obese individuals. For each membrane, 1 mL of serum from each participant was diluted 1:4 with a blocking buffer and added to the membrane. Following incubation and addition of antibodies, the array was exposed to x-ray film, and signals were detected using a film developer. These images were scanned and average intensities were measured using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad) after locating signals to antibody array map.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome measure was the change in the average LH pulse amplitude before and after administration of E2. With 10 subjects per group we had 80% power to detect a change of 0.3 IU/L (or a 37.5% reduction in LH pulse amplitude) using a paired t test with unequal variances assuming a moderate correlation of 0.5 between the baseline and follow-up outcomes on the same subject. This change is approximately 40% of the difference between the LH pulse amplitudes of NW and obese patients in cross-sectional studies (7).

LH pulsatility was characterized for first 6 hours of data prior to GnRH in each study period. LH pulse frequency and amplitude were computed for each individual before and after E2 use using a modified objective pulse detection method that has been previously validated (7, 20). Post-GnRH administration, both LH and FSH mean serum level, peak level, area under the curve (AUC), and maximum response (the arithmetic difference between the nadir prior to GnRH and the peak post GnRH) were evaluated. Baseline characteristics were compared between obese and NW women for all gonadotrope, cytokine, and DXA measures using two-sample t tests. A two-sample t test was used to assess whether average change in hormonal and demographic measures differed between obese and NW women. Paired t test was used to assess whether the assessed parameters differed before vs after the E2-priming intervention. P < .05 was used to denote statistical significance. The analysis was repeated on change in each of the other measures listed above. We also performed the analysis on the log (base-e) scale to address skew. The transformed and untransformed results were consistent. Thus, we present the findings on the untransformed scale. To investigate whether DXA measures were differentially correlated with gonadotropin measures in the obese and NW groups, separate linear regression models (one for each gonadotrope outcome) with an interaction between group (obese and NW) and DXA were fitted. All statistical calculations were performed using R software for Windows, version 3.1.2.

Results

Gonadotropins and steroid hormones

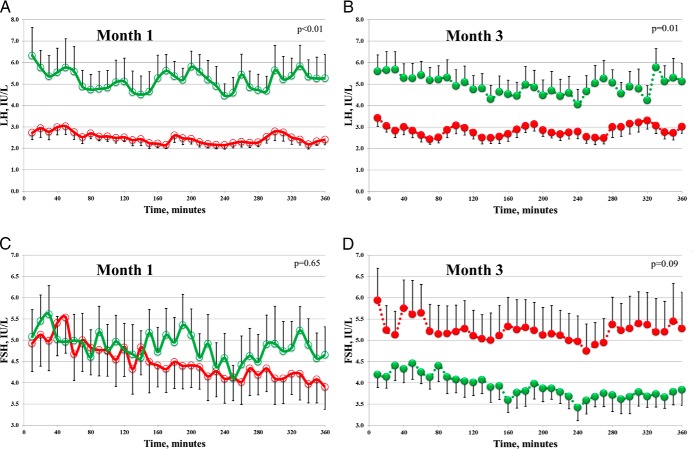

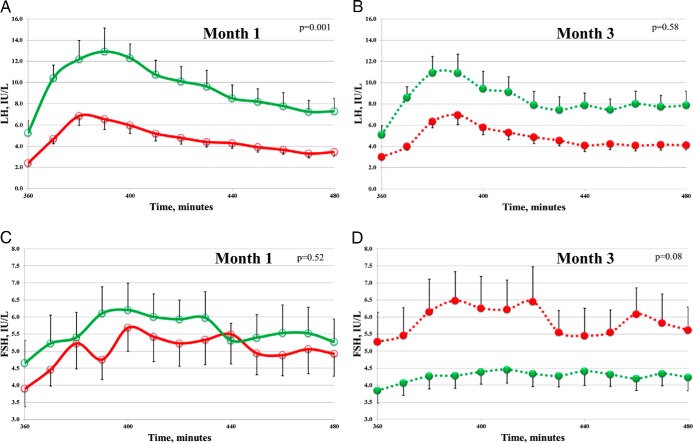

A total of 21 women provided complete data for analysis: 11 obese and 10 NW controls (Table 1). Compared with NW women, obese women exhibited reduced measures of ovarian reserve, AMH, and Inhibin B. At baseline, during the first 6 hours of unstimulated testing (Figure 1A, and Table 2), mean serum LH was significantly lower in obese women when compared with NW controls (2.5 ± 0.2 vs 5.2 ± 0.8 IU/L, respectively; P < .001). LH pulse amplitude was also significantly lower in obese women (1.1 ± 0.2 vs 2.7 ± 0.5 IU/L, respectively; P = .007), whereas pulse frequency did not differ between the groups (3.0 ± 0.3 for NW vs 3.2 ± 0.3 pulses in obese; P = .64; Supplemental Figure 2, month 1). Following a physiologic (75 ng/kg) iv GnRH bolus, all LH parameters (Figure 2A) remained significantly lower in obese women vs controls (mean serum level, AUC, peak, and maximum response; P ≤ .002 for all). Baseline FSH parameters were not statistically different between obese and NW women before or after GnRH (Figures 1C and 2C).

Table 1.

Biometric and Endocrine Characteristics

| Characteristic | NW (n = 10) | Obese (n = 11) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 29.4 (1.9) | 32.5 (1.8) | .25 |

| BMI kg/m2 | 21.2 (1.5) | 36.7 (1.3) | <.001 |

| Weight, kg | 59.4 (2.3) | 98.2 (4.0) | <.001 |

| Total body fat mass, kg | 16.2 (1.2) | 41.9 (2.2) | <.001 |

| Percentage of body fat | 27.9 (1.3) | 39.7 (4.1) | .02 |

| AMH, ng/mL | 3.2 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.3) | .01 |

| Inhibin B, pg/mL | 96.6 (11.5) | 67.7 (11.5) | .04 |

| T, ng/dL | 8.0 (2.5) | 13.3 (4.3) | .31 |

| Cycle 1 length, d | 32.2 (1.9) | 28.6 (1.8) | .18 |

| Cycle 2 length, d | 40.1 (3.0) | 38.0 (2.1) | .56 |

| Cycle 3 length, d | 25.4 (1.1 ) | 26.8 (1.5) | .46 |

Values represent mean (±SEM).

Figure 1.

Effect of transdermal estradiol treatment on serum gonadotropins. LH (A and B) and FSH (C and D) during unstimulated frequent blood sampling. Data are from normal-weight women (green; n = 10), and from obese women (red; n = 11) at month 1 (open circles) and month 3 (filled circles). Error bars indicate SEM for group composites. P values comparing mean levels between NW and obese women using two-sample t test.

Table 2.

Effect of Transdermal Estradiol on LH and FSH During Unstimulated and GnRH-stimulated Portions of Frequent Blood Sampling (IU/L)

| NW (n = 10) |

Obese (n = 11) |

Pe | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post Estradiol | δc | Pd | Baseline | Post Estradiol | δc | Pd | ||

| LH unstimulated | |||||||||

| Mean level | 5.19 (0.83) | 4.93 (0.67) | −0.26 (0.58) | .66 | 2.46 (0.24) | 2.93 (0.3) | 0.48 (0.4) | .27 | .32 |

| No. of pulses | 3.0 (0.26) | 3.5 (0.34) | 0.5 (0.34) | .18 | 3.2 (0.33) | 3.1 (0.28) | −0.1 (0.5) | .83 | .3 |

| Average pulse amplitude | 2.73 (0.46) | 2.18 (0.4) | −0.54 (0.42) | .23 | 1.12 (0.19) | 1.59 (0.29) | 0.47 (0.21) | .06 | .048 |

| FSH unstimulated | |||||||||

| Mean level | 4.86 (0.59) | 3.91 (0.29) | −0.94 (0.59) | .14 | 4.48 (0.57) | 5.23 (0.64) | 0.75 (0.64) | .26 | .07 |

| AUCa | 1751 (212.3) | 1411 (106.0) | −340.2 (212.7) | .14 | 1610 (206.7) | 1887 (230.7) | 276.4 (227.6) | .25 | .06 |

| Peak | 6.43 (0.74) | 4.95 (0.31) | −1.48 (0.73) | .07 | 5.79 (0.82) | 6.38 (0.81) | 0.6 (0.84) | .49 | .08 |

| LH GnRH-stimulated | |||||||||

| AUCa | 1203.5 (160) | 1126.0 (124.6) | −77.49 (148.2) | .68 | 581.6 (69.9) | 863.8 (269.3) | 282.2 (288.6) | .35 | .30 |

| Peak | 14.55 (2.03) | 11.97 (1.75) | −2.58 (1.9) | .21 | 6.81 (0.88) | 10.6 (12.3) | 0.33 (0.98) | .65 | .18 |

| Max responseb | 11.23 (1.5) | 8.73 (1.4) | −2.51 (1.65) | .24 | 5.19 (0.81) | 5.23 (0.71) | 0.04 (0.71) | .97 | .15 |

| FSH GnRH-stimulated | |||||||||

| Mean level | 5.59 (0.65) | 4.24 (0.33) | −1.35 (0.6) | .052 | 4.99 (0.64) | 5.87 (0.77) | 0.88 (0.67) | .22 | .02 |

| AUCa | 710.8 (83.9) | 544.0 (43.9) | −166.8 (79.3) | .065 | 641.6 (84.0) | 762.0 (101.1) | 120.4 (90.0) | .21 | .03 |

| Peak | 7.09 (0.69) | 4.99 (0.41) | −2.1 (0.63) | .009 | 6.14 (0.88) | 7.46 (1.01) | 1.31 (0.75) | .11 | .003 |

| Max responseb | 3.77 (0.44) | 2.13 (0.29) | −1.64 (0.41) | .006 | 2.67 (0.61) | 3.22 (0.68) | 0.54 (0.52) | .56 | .005 |

Values represent mean (±SEM), unless otherwise specified.

AUC, sum of concentrations for 360 min (unstimulated) or 120 min (GnRH stimulated) calculated using trapezoidal rule.

Max response to GnRH is defined as the peak level after the bolus minus the lowest value in the hour preceding GnRH.

Arithmetic difference between post estradiol and baseline.

P for comparing values before and post estradiol treatment in each group using paired t test.

P for comparing δ between NW and obese groups using two-sample t test.

Figure 2.

Effect of transdermal estradiol treatment on GnRH-stimulated serum gonadotropins. LH (A and B) and FSH (C and D) during frequent blood sampling after 75 ng/kg GnRH stimulation. Data are from normal-weight women (green; n = 10), and from obese women (red; n = 11) at month 1 (open circles) and month 3 (filled circles). Error bars indicate SEM for group composites. P values comparing mean levels between NW and obese women using two-sample t test.

Following transdermal E2 treatment, sampling suggested opposite changes in unstimulated LH output between NW and obese women (Figure 1, and Table 2). LH pulse amplitude increased in the obese group from 1.1 ± 0.2 to 1.6 ± 0.3 IU/L and decreased in NW women from 2.7 ± 0.5 to 2.2 ± 0.4 IU/L (P = .048; Supplemental Figure 2, month 3). Directionality of change was similar for mean LH (decreased from 5.2 ± 0.8 to 4.9 ± 0.7 IU/L in NW women whereas it increased from 2.5 ± 0.2 to 2.9 ± 0.3 IU/L in obese women), although this was not statistically significant (P = .32). No significant changes were observed in unstimulated mean FSH between NW and obese after E2 (Figure 1D).

Upon GnRH stimulation, month 3 FSH response also indicated opposite changes between NW and obese women in relation to month 1 studies (Figure 2, C and D; Table 2). On average, percent change for mean FSH was −24% for NW and +18% for obese women (P = .02). Similarly, all other metrics of FSH response to GnRH increased significantly in obese women but had a nonsignificant decrease in NW women following E2 treatment. LH parameters were not different for either group post-GnRH stimulation for month 3 vs month 1 comparison (Table 2).

Total serum T and E2 levels were measured. E2/androgen ratios were calculated at baseline (month 1) and after the intervention (month 3). No significant differences in E2/androgen ratios were observed for either within the group or between the group comparisons.

Urinary hormones

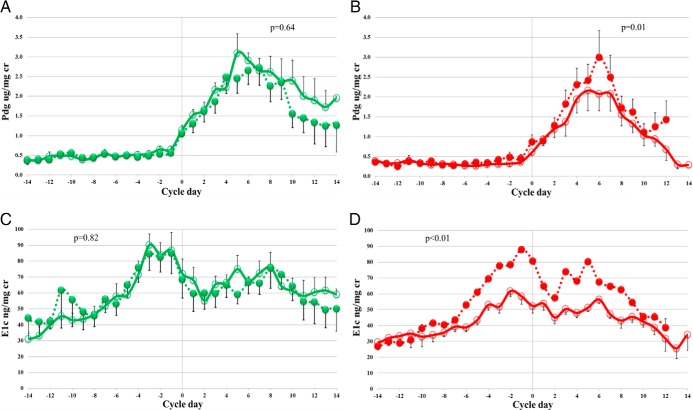

All subjects were ovulatory at baseline by objective a priori criteria (17). Cycle length did not differ between NW and obese women at any point during the study (Table 1). Following E2, six NW and five obese women required oral progestin administration to induce menstrual bleeding because they had not initiated bleeding after 40 days of transdermal E2 (the proportion of progestin takers was not different between NW and obese groups; P = .51). After E2 priming (month 3), all NW and seven obese women were ovulatory. There was a significant increase in luteal urinary Pdg excretion from 17.6 ± 2.9 to 21.8 ± 3.4 ug/mg cr (P = .01), as well as an increase in follicular phase E1c excretion from 600.9 ± 98.2 to 780.5 ± 85.5 ng/mg cr (P = .003) in ovulatory obese women (Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 1). E2 treatment did not significantly affect corresponding levels of Pdg and E1c in NW women.

Figure 3.

Effect of transdermal estradiol treatment on urinary hormones. Pdg (A and B) and E1c (C and D). Error bars indicate SEM for composite whole-cycle data. Data were centered on the day of luteal transition. Data from ovulatory normal-weight women (green; n = 10), and obese women (red; n = 7) at month 1 (open circles) and month 3 (filled circles). P values comparing luteal phase levels for Pdg and comparing follicular phase levels for E1c using a paired t test.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted by controlling for participants who required oral progesterone administration and looking at their results in both subgroups (patients who took progesterone and those who did not). For all tested subgroups, the association of the gonadotropin outcomes did not change assessment of statistical significance and the point estimates remained similar to that of the full cohort (data not shown).

Proinflammatory cytokines

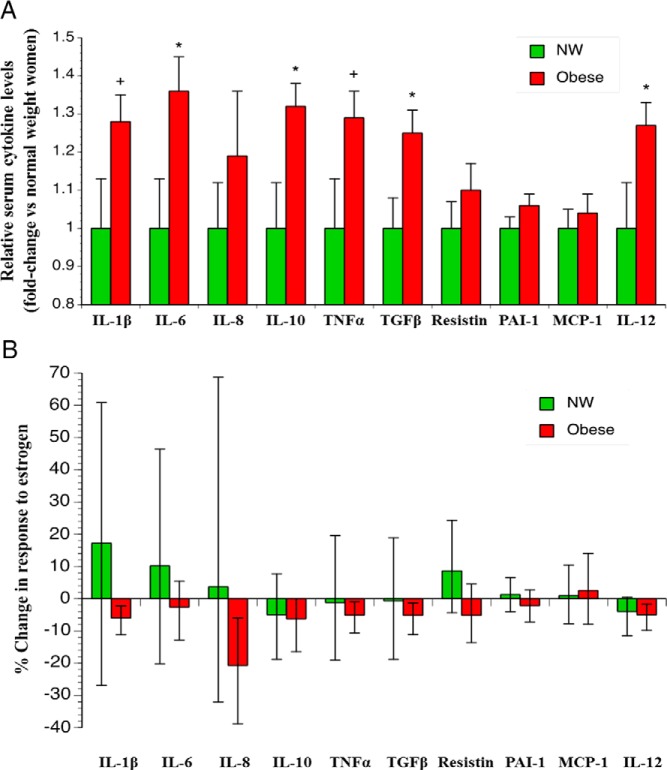

We examined selected circulating serum cytokines before and after E2 using markers implicated in maternal obesity-associated inflammation (21, 22). Obese women had significantly higher baseline IL-6, IL-10, TGF-β, and IL-12 compared with NW (all P < .05). In addition, IL-1β and TNF-α comparison at baseline in obese vs NW women were just shy of conventional statistical significance levels (P = .06) (Figure 4A). When these measurements were repeated in the third month of the study after a month of E2 treatment, nine of 10 cytokines had decreased in the obese women, with a statistically significant decrease in IL-1β, IL-8, TGF-β, and IL-12 (P < .05 for all). A similar trend was observed for TNF-α (P = .051) in obese women (Figure 4B). No significant changes in cytokines were observed in NW women (Supplemental Table 2). When the analysis was restricted to only ovulatory women, similar results were seen (data not shown). Principal component analysis (23) was performed for these cytokines and analyzed in NW and obese women before and after treatment (see Supplemental Materials and Methods). Among all measured cytokines that contributed to the variance for the pre- and post-treatment time points, IL-8, and PAI-1 seemed to be most promising cytokines that are potentially important in explaining the mechanisms behind the observed results (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Effect of transdermal estrogen treatment on proinflammatory cytokines. Relative baseline cytokine levels (A). Data are mean ± SEM at month 1. *, P < .05; +, P = .06. P values represent comparisons of the two group levels using a two-sample t test. Change in cytokine levels in response to estrogen (B). Results are expressed as percent change in cytokine levels after treatment in month 3. Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

DXA

As expected, all adiposity indices for the obese group were markedly higher than for NW (Table 1), substantiating the adequacy of BMI for selecting our study criteria. Strong inverse relationships between LH output and total and central adiposity were observed for all participants (Supplemental Table 3). FSH metrics were only associated with adiposity in the obese but not NW women: mean unstimulated FSH was negatively related to total fat mass (r = −0.71; P = .01); FSH AUC after GnRH was negatively related to total fat mass (r = −0.62; P = .04); and peak unstimulated FSH negatively related to percent trunk fat (r = −0.62; P = .04) in obese women. There were no correlations of FSH with any measure of body composition in NW women (Supplemental Figure 4).

Discussion

Obesity is associated with hypogonadotropism in ovulatory women without PCOS (7). The mechanisms behind this association are not well understood. We have tested the effect of exogenous estrogen on the HPO axis based on BMI. We predicted that augmented negative feedback with E2 would be more likely to cause cycle disruption in obese women. Instead, the obese women responded with increased LH pulse amplitude and improved FSH responsiveness to GnRH, whereas NW women demonstrated the expected evidence of HPO axis suppression in response to E2 priming. Improvement of the serum proinflammatory cytokine profile was also observed after E2 treatment in the obese. Estrogen treatment improved corpus luteum function by 25–30% only in ovulatory obese women (7/10), with no effect in NW women. Improvement in ovarian hormonal production was likely related to improvement in central gonadotrope measures as well as to improvement in the proinflammatory cytokines. To the best of our knowledge, this the first report of an association between an improvement in gonadotrope sensitivity and amelioration of chronic inflammation in obesity.

Obesity produces a unique inflammatory state that is low grade, chronic, and creates a modified milieu favoring a proinflammatory systemic and local environment (21, 22, 24). Many inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, are dramatically increased in adipose tissue and other sites, including the hypothalamus (25). TNF-α and IL-1β are known to suppress pituitary LH secretion in animal studies (26). Estrogen modulates cytokine expression in vitro and in vivo (27, 28). It specifically inhibits proinflammatory cytokine production in numerous clinical studies (29), although it is also reported to play a proinflammatory role in some autoimmune diseases (30).

We herein report that transdermal E2 treatment reduced the serum levels of nine of 10 of the examined proinflammatory cytokines in obese women, with significant reduction in IL-1β, IL-8, TGF-β, and IL-12. Although the magnitude of change was moderate, the overall direction for the entire proinflammatory profile was consistent with other clinical studies of exogenous E2 administration in women (31) and in agreement with other interventional studies of serum cytokines in obesity (32). Obesity has been associated with increased levels of IL-10 (33), possibly acting with anti-inflammatory properties. Both IL-10 and TGF-β were elevated in obese individuals when compared with NW women, but after estrogen treatment, TGF-β but not IL-10 decreased significantly in obese women. Estrogen treatment as was seen here, did not change the levels of IL-10 and may suggest unaffected anti-inflammatory role of this cytokine in this context. We interpret our results that estrogen treatment had a positive anti-inflammatory action and that resulted in a decrease of the levels of most proinflammatory cytokines. Cytokines were measured using a well-established platform that was successfully used in animal studies. Although there was a considerable variability of before vs after cytokine change in response to intervention (Figure 4B), the variability of actual cytokine measurements was well within the acceptable limits and similar to in vitro and clinical studies (Figure 4A) (21, 34).

Obesity presents an apparent paradox of decreased gonadal hormones and inappropriate under-response of FSH (35). In women, circulating FSH levels are responsive to the endocrine input from the ovary. The inhibins, secreted by ovarian granulosa cells, exert a negative feedback on FSH (36). The increase of FSH with chronological and reproductive aging is classically preceded by a decrease in circulating inhibin B (37). However, this paradigm is not operative in obesity, which is associated with reduced levels of inhibin B (38, 39) and overall lower whole cycle estrogen secretion and excretion (40). Further, this reduction of inhibin B with obesity is not associated with a reduction in the number of ovarian follicles (12, 41) and this inverse association of inhibin B with BMI disappears after menopause (39). This is noteworthy because it suggests that the effect of obesity is exerted on granulosa cell function, rather than through an altered volume of distribution. This paradigm is not sex specific as reduced inhibin B is also a characteristic feature of male obesity (42). Thus, obesity represents a state of relatively low ovarian hormonal function for reasons that are not well understood. We hereby present data suggesting that exogenous E2 results in increased FSH output and increased LH pulse amplitude in obese women coincidental with reduced serum proinflammatory cytokines. In rats, administration of IL-1β into the cerebral ventricles results in immediate reduction of FSH and LH secretion by the pituitary and consequent reduction in gonadal sex steroids (43). The link between circulating inflammatory cytokines and suppression of HPO axis function is also consistent with endotoxin-induced increase in hypothalamic IL-1β concentration, which results in profound suppression of gonadotropin output (44). Future studies are well positioned to examine anti-inflammatory interventions in an attempt to alleviate the relative hypogonadotropism of obesity.

We also examined the relationship between gonadotropins and regional adiposity by DXA, because regional body fat distribution can be more important than overall adiposity in predicting disease risk. Recent advances in our understanding of androgen metabolism suggest that site-specific modulation of expression of a key enzyme, 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 5 (17β-HSD5), mediates susceptibility of adipose tissue to aberrant androgen production that is characteristic of obesity (45). Specifically, altered activity of 17β-HSD5 resulted in a net gain in more potent androgens in sc fat, which was in contradistinction to the net gain in less potent androgens in omental fat. Thus, differential regional fat distribution may play a role in reproductive competency of obese individuals. Visceral obesity is thought to be predominantly associated with poor metabolic health and reduced fecundity, even in ovulating women (46). In the present report, when both obese and NW groups were analyzed together, LH output was found to be attenuated with increasing total and central (visceral) adiposity regardless of body mass. FSH output was inversely related to adiposity only in obese, but not NW women. We included studies of body composition by DXA in correlation with reproductive hormones as a pilot exploration to approach the issues of regional variability of adipose tissue in reproduction.

In summary, we have shown an improvement of LH pulse amplitude and FSH response to GnRH in obese women following E2 treatment as well as an improvement in corpus luteum function in ovulatory obese women. Strengths of this study include detailed frequent blood sampling, daily urine collection, and robust assays. The limitations include a moderate sample size. Nonetheless, the level of detail with which we were able to perform this study will help to inform larger-scale investigations examining the relationship between chronic inflammation and reproductive hormones. Also, due to the presence of a strong outlier in the NW women group and small sample size, it is difficult to draw conclusions regarding the discordant association of LH and FSH with adiposity. This should be further probed on a larger scale. Another limitation was the use of a progestin to induce menstrual bleeding, as that led to variable starting time for post-interventional studies, the proportion of women who took progestin in both groups was not different, however, and when controlling for those women who took progestin, results remained the same. Our findings imply that HPO axis function seems to improve in ovulatory, obese women concurrent with improved proinflammatory profiles after E2 priming. Reducing chronic inflammation at the pituitary level may decrease the burden of obesity on fertility. Given the public health implications of maternal obesity, future studies should address medical or nutritional strategies directed at decreasing chronic inflammation and alleviating the burden of obesity on reproductive fitness.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of Bill Lasley, PhD, and the Endocrine Core at the California National Primate Research Center, who supplied conjugate and antibody for the urinary steroid assays. The University of Virginia, Center for Research in Reproduction Ligand Assay and Analysis Core for hormonal assays. We also gratefully acknowledge invaluable assistance with cytokine measurement and interpretation of Jacob Friedman, PhD and Becky de la Houssaye, MS.

This study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov as trial number NCT01381016.

This work was supported by Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Grant No. 7347 and the Clinical and Translational Sciences Centers at the University of Colorado School of Medicine 1UL1 RR025780 (University of Colorado Clinical and Translational Research Center). Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Institutes of Health (Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research) Grant U54-HD28934. GnRH was supplied by Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

Neither the sponsor nor any of the grant providers had any role in the design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Disclosure Summary: N.S. reports investigator-initiated grant funding from Bayer, Inc. and stock options in Menogenix. Z.A., H.L., N.C., J.C., J.L., C.R., A.B., N.G., T.P., W.K., and A.P. have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AMH

- anti-Müllerian hormone

- AUC

- area under the curve

- BMI

- body mass index

- DXA

- dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- E1c

- estrone conjugates

- E2

- estrogen

- HPO

- hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian

- 17β-HSD5

- 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 5

- NW

- normal weight

- PCOS

- polycystic ovary syndrome

- Pdg

- pregnanediol glucuronide.

References

- 1. Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States—Gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:6–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Polotsky AJ, Hailpern SM, Skurnick JH, Lo JC, Sternfeld B, Santoro N. Association of adolescent obesity and lifetime nulliparity—The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2004–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sherman BM, Korenman SG. Measurement of serum LH, FSH, estradiol and progesterone in disorders of the human menstrual cycle: The inadequate luteal phase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1974;39:145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Santoro N, Lasley B, McConnell D, et al. Body size and ethnicity are associated with menstrual cycle alterations in women in the early menopausal transition: The Study of Women's Health across the Nation (SWAN) Daily Hormone Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2622–2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Todd BJ, Ladyman SR, Grattan DR. Suppression of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion but not luteinizing hormone surge in leptin resistant obese Zucker rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vermeulen A, Kaufman JM, Deslypere JP, Thomas G. Attenuated luteinizing hormone (LH) pulse amplitude but normal LH pulse frequency, and its relation to plasma androgens in hypogonadism of obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:1140–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jain A, Polotsky AJ, Rochester D, et al. Pulsatile luteinizing hormone amplitude and progesterone metabolite excretion are reduced in obese women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2468–2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Levine JE, Chappell P, Besecke LM, et al. Amplitude and frequency modulation of pulsatile luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone release. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1995;15:117–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shaw ND, Histed SN, Srouji SS, Yang J, Lee H, Hall JE. Estrogen negative feedback on gonadotropin secretion: Evidence for a direct pituitary effect in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1955–1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Singh SP, Wolfe A, Ng Y, et al. Impaired estrogen feedback and infertility in female mice with pituitary-specific deletion of estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1). Biol Reprod. 2009;81:488–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tworoger SS, Eliassen AH, Missmer SA, et al. Birthweight and body size throughout life in relation to sex hormones and prolactin concentrations in premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2494–2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Pergola G, Maldera S, Tartagni M, Pannacciulli N, Loverro G, Giorgino R. Inhibitory effect of obesity on gonadotropin, estradiol, and inhibin B levels in fertile women. Obesity. 2006;14:1954–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ito A, Bebo BF, Jr, Matejuk A, et al. Estrogen treatment down-regulates TNF-alpha production and reduces the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in cytokine knockout mice. J Immunol. 2001;167:542–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koh KK. Effects of estrogen on the vascular wall: Vasomotor function and inflammation. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55:714–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martin K, Santorot N, Hall J, et al. Management of ovulatory disorders with pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:1081A–1081G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ditkoff EC, Fruzzetti F, Chang L, Stancyzk FZ, Lobo RA. The impact of estrogen on adrenal androgen sensitivity and secretion in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:603–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Santoro N, Crawford SL, Allsworth JE, et al. Assessing menstrual cycles with urinary hormone assays. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E521–E530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lauw FN, Pajkrt D, Hack CE, Kurimoto M, van Deventer SJ, van der Poll T. Proinflammatory effects of IL-10 during human endotoxemia. J Immunol. 2000;165:2783–2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fontana A, Constam DB, Frei K, Malipiero U, Pfister HW. Modulation of the immune response by transforming growth factor beta. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1992;99:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rochester D, Jain A, Polotsky AJ, et al. Partial recovery of luteal function after bariatric surgery in obese women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1410–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heerwagen MJ, Stewart MS, de la Houssaye BA, Janssen RC, Friedman JE. Transgenic increase in N-3/n-6 Fatty Acid ratio reduces maternal obesity-associated inflammation and limits adverse developmental programming in mice. PloS One. 2013;8:e67791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:415–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ringnér M. What is principal component analysis? Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:303–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bastard JP, Maachi M, Lagathu C, et al. Recent advances in the relationship between obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. De Souza CT, Araujo EP, Bordin S, et al. Consumption of a fat-rich diet activates a proinflammatory response and induces insulin resistance in the hypothalamus. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4192–4199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rivier C, Vale W. Cytokines act within the brain to inhibit luteinizing hormone secretion and ovulation in the rat. Endocrinology. 1990;127:849–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gilmore W, Weiner LP, Correale J. Effect of estradiol on cytokine secretion by proteolipid protein-specific T cell clones isolated from multiple sclerosis patients and normal control subjects. J Immunol. 1997;158:446–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Monteiro R, Teixeira D, Calhau C. Estrogen signaling in metabolic inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:615917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Racho D, Myliwska J, Suchecka-Racho K, Wieckiewicz J, Myliwski A. Effects of oestrogen deprivation on interleukin-6 production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells of postmenopausal women. J Endocrinol. 2002;172:387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Straub RH. The complex role of estrogens in inflammation. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:521–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vural P, Akgul C, Canbaz M. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on plasma pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and some bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women. Pharmacol Res. 2006;54:298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marfella R, Esposito K, Siniscalchi M, et al. Effect of weight loss on cardiac synchronization and proinflammatory cytokines in premenopausal obese women. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Esposito K, Pontillo A, Giugliano F, et al. Association of low interleukin-10 levels with the metabolic syndrome in obese women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1055–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Prabhakar U, Eirikis E, Davis HM. Simultaneous quantification of proinflammatory cytokines in human plasma using the LabMAP assay. J Immunol Methods. 2002;260:207–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Globerman H, Shen-Orr Z, Karnieli E, Aloni Y, Charuzi I. Inhibin B in men with severe obesity and after weight reduction following gastroplasty. Endocr Res. 2005;31:17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Groome NP, Illingworth PJ, O'Brien M, et al. Measurement of dimeric inhibin B throughout the human menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:1401–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Welt CK, McNicholl DJ, Taylor AE, Hall JE. Female reproductive aging is marked by decreased secretion of dimeric inhibin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cortet-Rudelli C, Pigny P, Decanter C, et al. Obesity and serum luteinizing hormone level have an independent and opposite effect on the serum inhibin B level in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR. Obesity and reproductive hormone levels in the transition to menopause. Menopause. 2010;17:718–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Randolph JF, Jr, Sowers M, Gold EB, et al. Reproductive hormones in the early menopausal transition: Relationship to ethnicity, body size, and menopausal status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1516–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Roth LW, Allshouse AA, Bradshaw-Pierce EL, et al. Luteal phase dynamics of follicle-stimulating and luteinizing hormones in obese and normal weight women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2014;81:418–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jensen TK, Andersson AM, Hjollund NH, et al. Inhibin B as a serum marker of spermatogenesis: Correlation to differences in sperm concentration and follicle-stimulating hormone levels. A study of 349 Danish men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:4059–4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Turnbull AV, Rivier C. Inhibition of gonadotropin-induced testosterone secretion by the intracerebroventricular injection of interleukin-1 beta in the male rat. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1008–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ma XC, Chen LT, Oliver J, Horvath E, Phelps CP. Cytokine and adrenal axis responses to endotoxin. Brain Res. 2000;861:135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Quinkler M, Sinha B, Tomlinson JW, Bujalska IJ, Stewart PM, Arlt W. Androgen generation in adipose tissue in women with simple obesity—A site-specific role for 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 5. J Endocrinol. 2004;183:331–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zaadstra BM, Seidell JC, Van Noord PA, et al. Fat and female fecundity: Prospective study of effect of body fat distribution on conception rates. BMJ. 1993;306:484–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]