Abstract

Background & Aims

Anemia is a common manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that can greatly affect patients’ quality of life. We performed a prospective study of a large cohort of patients with IBD to determine if patterns of anemia over time are associated with aggressive or disabling disease.

Methods

We performed a longitudinal analysis of demographic, clinical, laboratory, and treatment data from a registry of patients with IBD at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center from 2009 through 2013. Patients with a complete follow up (at least 1 annual visit with laboratory results) were included. Anemia was defined by World Health Organization criteria. Disease activity scores (the Harvey-Bradshaw Index or ulcerative colitis activity index) and quality of life scores (based on the short IBD questionnaire) were determined at each visit; laboratory data, including levels of C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rates, as well as patterns of IBD-related health care use, were analyzed.

Results

A total of 410 IBD patients (245 with Crohn’s disease, 165 with ulcerative colitis, and 50.5% female) were included. The prevalence of anemia in patients with IBD was 37.1% in 2009 and 33.2% in 2013. Patients with IBD and anemia required significantly more health care and had higher indices of disease activity, as well as lower average quality of life, than patients without anemia (P<.0001). Anemia (persistent or recurrent) for ≥3 years was independently correlated with hospitalizations (P<.01), visits to gastroenterology clinics (P<.001), phone calls (P<.004), surgeries for IBD (P=.01), higher levels of C-reactive protein (in patients with ulcerative colitis, P=.001), and higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate (P<.0001). Anemia negatively correlated with quality of life score (P<.03).

Conclusion

Based on a longitudinal analysis of 410 patients, persistent or recurrent anemia correlates with more aggressive or disabling disease in patients with IBD.

Keywords: Quality of life, CRP, ESR, CD, UC

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic inflammatory disorders characterized by a variable clinical course. CD often has a progressive pattern from inflammatory to more complicated disease with stenoses or fistulae (1). UC may become more extensive with time, increasing the possibility of colectomy or cancer (2). IBD patients who manifest an aggressive disease course characterized by frequent relapses, persistent inflammatory activity, a need for intensified medical treatment and/or surgical management have recently been defined as having severe or disabling disease (3).

There is a lack of reliable and universally accepted biomarkers which predict disease course in IBD. Moreover, the assessment of disease activity in IBD is difficult (4,5). (5). Concerning the use of biomarkers in the management and prognosis of IBD, CRP and fecal calprotectin are the most widely used but both have several limitations and are far from ideal. Due to the shortcomings of clinical and biochemical indices, endoscopic evaluation and assessment of mucosal healing is becoming increasingly important in the clinical management of IBD patients (6).

Anemia is an important complication and/or extraintestinal manifestation of IBD which is present in one third of the patients resulting in a significant impact on their quality of life. Several recent studies have focused on the prevalence, pathophysiology and treatment of anemia in IBD (7–11); however, the data on the use of anemia and its course over time in the outpatient clinic setting as a potential marker of disabling disease is limited. A recent study of 62 uncomplicated CD patients showed that low hemoglobin or hematocrit levels were independent predictors of the first complication or CD-related surgery (12). Persistent anemia is common in IBD (13), but its potential role in the disease stratification is unknown.

The aim of this study was to investigate if the presence and duration of anemia in IBD patients followed longitudinally correlate with a clinical pattern of aggressive/disabling disease.

Patients and methods

The characteristics of the consented, prospective, longitudinal natural history registry of patients with IBD at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center have been previously described (14). In addition to demographic information, the registry houses temporally organized prescription, endoscopic, pathological, radiological, laboratory, and other clinical data regarding healthcare utilization of enrolled patients and is updated routinely through Information Technology support. De-identified longitudinal data were used in the analysis from patients with a definitive IBD diagnosis according to established criteria. Patients who were seen during the 5-year period from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2013 and who had complete follow-up defined as at least one annual visit during this period with laboratory evaluation were included. Demographic, clinical and laboratory data prospectively collected from clinic visits and information from electronic medical record based computer searches and manual confirmation of information were recorded. Complete blood count data, disease activity scores, biochemical markers of inflammation and anemia, and patterns of medication use were prospectively monitored in all patients. Patterns of health care use such as emergency department (ED) or GI clinic visits, phone calls to the IBD office and hospitalizations were also prospectively recorded. Disease location and behavior in CD and extent of bowel involvement in UC was classified according to clinical activity scores such as Harvey-Bradshaw index (HBI) for CD (16) and ulcerative colitis activity index (UCAI) for UC (17). Prospectively collected health-related quality of life as measured by the validated short IBD questionnaire (SIBDQ) (18) was also analyzed. The average scores of HBI, UCAI, and SIBDQ as well as of CRP and ESR of the 5-year measurements were calculated and used in the analysis.

Anemia was defined as Hb <13 g/dL in men and Hb <12 g/dL in non-pregnant women based on World Health Organization (WHO) criteria (19). IBD patients were divided in three groups: patients without anemia (group A), patients with anemia for one or two (consecutive or not) years (group B) and patients with anemia for 3 (consecutive or not) or more years (group C). Persistent anemia was considered the absence of hematopoietic response (normal Hb) after treatment and recurrent anemia was considered the response to treatment followed by drop of Hb. Patients with other important diseases which may manifest with anemia such as renal or heart failure, cirrhosis and malignancies were excluded from the analysis. Information on possible iron supplementation for anemic patients was characterized using the electronic records. Proportions of patients treated for anemia at the time of the evaluation with oral or intravenous (IV) iron were recorded.

The University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Review Board approved enrollment and participation of the patients in the research registry (PRO12110117).

Statistical analysis

Data is presented either as mean±SD for continuous, normally distributed variables or as median and range for nonparametric data. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate distribution normality. Differences between groups were evaluated using Student’s t test for parametric continuous data and Mann–Whitney U test for nonparametric continuous data. Data from contingency tables was analyzed using chi-squared analysis. Correlation with Spearman’s rho (r) was used for assessing the relationship between anemia status and biomarkers or disease activity indices. A logistic regression analysis was used to adjust for potential confounders. In the final model, the dependent variable was the presence of persistent anemia, and the covariates were those with significance <.1 in the univariate analysis. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 421 IBD patients met the inclusion criteria of complete follow-up with at least one annual visit including complete blood count and biomarkers (CRP and ESR) evaluation. Eleven cases were excluded due to uncertain IBD diagnosis or presence of other diseases related to the manifestation of anemia. In the final study population there were 245 patients with CD and 165 with UC. The demographic and clinical data of the IBD patients included in the study is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease patients included in the study

| Diagnosis | CD | UC | Total IBD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 245 (59.8) | 165 (40.2) | 410 (100) |

| Median age (years, range) | 39 (17–79) | 43 (15–83) | 40 (15–83) |

| Gender (females, %) | 137 (55.9) | 70 (42.4) | 207 (50.5) |

| Smoking (yes, %) | 102 (41.6) | 63 (38.2) | 165 (40.2) |

| Median disease duration (years, range) | 13 (0–63) | 10 (0–70) | 11 (0–70) |

| Montreal classification for UC | |||

| Proctitis (E1, %) | 14 (8.6) | ||

| Left sided colitis (E2, %) | 59 (35.6) | ||

| Extensive colitis (E3, %) | 92 (55.8) | ||

| Montreal classification for CD | |||

| Inflammatory (B1, %) | 99 (40.4) | ||

| Stricturing (B2, %) | 92 (37.6) | ||

| Penetrating (B3, %) | 54 (22.0) | ||

| Perianal (p, %) | 57 (23.3) | ||

| Ileum (L1, N, %) | 58 (23.7) | ||

| Colon (L2, N, %) | 49 (20.0) | ||

| Ileocolon (L3, N, %) | 132 (53.9) | ||

| Upper GI (L4, N, %) | 6 (2.4) | ||

| Use of immunomodulators (N, %) | 113 (46.1) | 53 (32.1) | 166 (40.%) |

| Use of biologics (N, %) | 94 (38.4) | 20 (12.1) | 114 (27.8) |

| History of surgery for IBD (N, %) | 149 (60.8) | 46 (27.9) | 195 (47.6) |

CD, Crohn’s disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; UC, ulcerative colitis

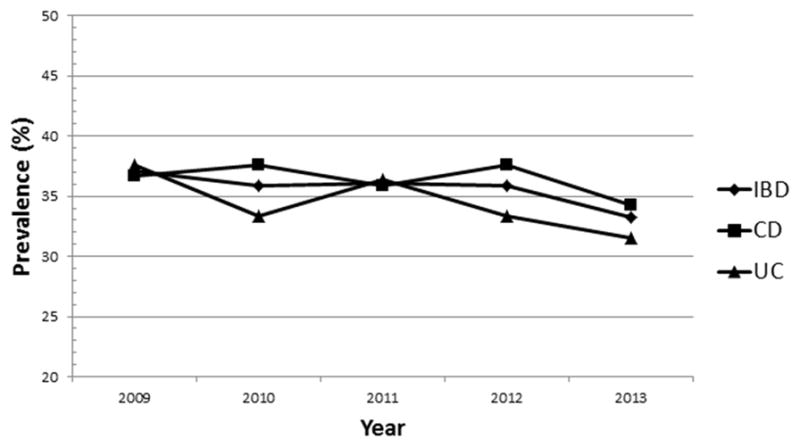

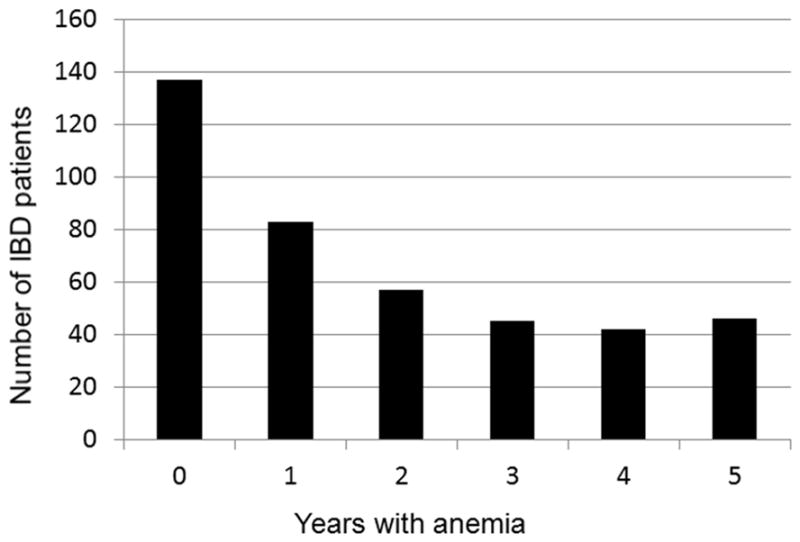

The prevalence of anemia was 37.1% (36.7% for CD and 37.6% for UC) in 2009 with a small decrease in 2013 to 33.2% (CD 34.3%, UC 31.5%). The prevalence of anemia per year in IBD patients is presented in Figure 1. No significant differences between CD and UC or the time periods of the study concerning the prevalence of anemia were found (p>.05). The burden of anemia as expressed by years with anemia of the IBD patients is presented in Figure 2. One hundred thirty seven IBD patients (33.4%) were without anemia at any time (group A), 140 IBD patients (34.1%) had anemia for 1–2 years (group B) and 133 patients (32.5%) had anemia for ≥3 years (group C). Median numbers of measurements with normal Hb were 12 (5–48) in group A, 11 (3–36) in group B and 9 (0–29) in group C. Median numbers of Hb measurements with low values were 0 in group A, 2 (1–17) in group B and 12 (3–150) in group C. Among patients of group C 30 (23.6%) had persistent anemia (no measurement with normal Hb) and 103 (77.4%) had recurrent anemia (measurements with low and normal Hb). Twenty four patients (80%) with persistent anemia and 78 patients (75.7%) with recurrent anemia had active disease (HBI or UCAI>4). Iron supplementation at any time was administered to 167 patients (131 oral, 36 IV). Folate or vitamin B12 deficiency was found in 4 and 7 cases with anemia respectively. CD patients with history of surgery (149) were under vitamin B12 replacement. No case with myelodysplastic syndrome was observed.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease patients over the 5 year period

CD, Crohn’s disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; UC, ulcerative colitis

Figure 2.

The burden of anemia as expressed by years with anemia of the inflammatory bowel disease patients included in the study

IBD patients without anemia during the 5 years were found to have significantly lower clinical or biochemical activity scores (average values for the 5 years), and lower rates of health care use (ED or GI clinic visits, phone calls and hospitalizations) as well as higher SIBDQ score compared to patients with anemia (for all parameters p<.0001). IBD patients of group C had significantly higher clinical or biochemical activity scores (average values for the 5 years), and higher rates of health care use (ED or GI clinic visits, phone calls and hospitalizations) as well as lower SIBDQ score compared to patients of groups A and B (Table 2). The prevalence of complicated disease (stricturing or penetrating) was higher in CD patients of groups C (61.7%) and B (58.9%) compared to CD patients of group A (48.6%) but the difference was not statistical significant (p=.07). The prevalence of extensive UC was significantly higher in group C (58.5%) compared to groups A (38.3%) and B (37.9%) (p=.004).

Table 2.

Activity indices, quality of life scores and health care use in inflammatory bowel disease patients in relation to the status of anemia

| Parameter | Group A* | Group B** | Group C*** | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-year average CRP (mg/L, median, range) | 0.2 (0.02–5.2) | 0.5 (0.02–9.5) | 1.1 (0.02–23.5) | <.001 |

| 5-year average ESR (mm/h mean ± SD) | 14.7 ± 8.5 | 18.8 ±12.0 | 34.1 ± 20.8 | <.0001 |

| 5-year average HBI (for CD, median, range) | 2.0 (0–17) | 3.3 (0–23) | 5.7 (0.4–21.8) | <.001 |

| 5-year average UCAI (for UC, median, range) | 1.7 (0–13) | 3.0 (0–13) | 5.3 (0–28) | .001 |

| 5-year average SIBDQ (median, range) | 58 (22.7–69.8) | 52.4 (26.5–70) | 47.2 (18.2–67.3) | <.001 |

| Phone calls (median, range) | 13 (0–95) | 17 (0–157) | 28 (0–288) | <.001 |

| Emergency department visits (median, range) | 0 (0–52) | 1 (0–79) | 4 (0–78) | <.0001 |

| GI department visits (median, range) | 8 (0–29) | 11 (0–81) | 12 (0–107) | <.001 |

| Hospitalizations (median, range) | 0 (0–7) | 1 (0–27) | 3 (0–27) | <.0001 |

Patients without anemia;

with anemia for 1–2 years;

with anemia for ≥3 years;

CRP, C-reactive protein, ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; SIBDQ, short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire; HBI, Harvey-Bradshaw index; CD, Crohn’s disease; UCAI, ulcerative colitis activity index; UC, ulcerative colitis

Concerning the use of IBD medications patients of group C had significantly lower use of thiopurines (azathioprine or mercaptopurine) compared to group A patients (p=.008) but the use of methotrexate or biologic agents was similar among groups (Table 3). In seven cases (5 CD, 2UC) with persistent anemia, erythropoietic growth factors (2 epoetin alfa, 5 darbepoetin alfa) were also administered. Blood transfusions occurred rarely (4% of the patients) and were given in cases with Hb<7g/dl (17 patients 5 in group B and 12 in group C).

Table 3.

Use of medications and history of operations in inflammatory bowel disease patients in relation to the status of anemia at the time of the evaluation

| Medication | Group A* | Group B** | Group C*** | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azathioprine or mercaptopurine (N, %) | 57 (41.6 %) | 47 (33.6) | 34 (25.6) | .008**** |

| Methotrexate | 6 (4.4) | 13 (9.3) | 13 (9.8) | .14 |

| Biologics | 32 (23.4) | 45 (32.1) | 37 (27.8) | .48 |

| Oral iron | 5 (3.6) | 10 (7.1) | 20 (15.0) | .002* |

| IV iron | 0 (0) | 4 (2.9) | 10 (7.5) | .003* |

| History of IBD surgery | 39 (28.5) | 74 (52.9) | 82 (61.6) | <.0001* |

Patients without anemia;

with anemia for 1–2 years;

with anemia for ≥3 years;

group A vs group C

IV, intravenous; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease

In the Spearman’s correlation the anemia status of the IBD patients was significantly correlated with CRP (r=.37, p<.0001), ESR (r=.46, p<.0001), SIBDQ (r=−.29, p<.0001), ED (r=.41, p<.0001) or GI clinic (r=.13, p=.007) visits, phone calls (r=.26, p<.0001), hospitalizations (r=.49, p<.0001) and history of a surgery for IBD (r=.25, p<.0001). Anemia status was also significantly correlated with HBI (r=.32, p<.0001) in CD patients and with UCAI (r=.34, p<.0001) in UC patients. No association with diagnosis (CD vs UC), gender, smoking status, or disease duration was found (p>.05).

Table 4 shows the factors associated with persistent/recurrent anemia in the logistic regression analysis. After adjustment, the parameters that were found to be associated with persistent/recurrent anemia in the final model were ESR (p<.0001), SIBDQ (p=.03), GI clinic visits (p=.001), phone calls (p=.004), hospitalizations (p=.01) and surgery for IBD (p=.01). Logistic regression analysis of only CD patients showed similar results but in contrast to univariate analysis no correlation of persistent/recurrent anemia with HBI (OR 1.04, 95% CI:0.94–1.15, p=.38). Logistic regression analysis in UC patients showed further significant correlation of persistent/recurrent anemia with UCAI (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.03–1.44, p=.002) and with CRP (OR 2.54, 95% CI 1.31–4.92, p=.006).

Table 4.

Determinants of persistent/recurrent anemia in inflammatory bowel disease patients in the adjusted analysis

| Independent variables | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.08 (0.88–1.33) | .45 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 1.08 (1.06–1.11) | <.0001 |

| SIBDQ | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | .03 |

| ED visits | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | .73 |

| GI clinic visits | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | .001 |

| Phone calls | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | .004 |

| Hospitalizations | 1.20 (1.04–1.39) | .01 |

| History of surgery for IBD | 2.15 (1.17–3.98) | .01 |

OD, odds ratio; CI, confidence intervals; CRP, C-reactive protein, ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; SIBDQ, short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire; ED, Emergency department; GI, Gastrointestinal

Discussion

In this study we found that patients with IBD and anemia and particularly those with persistent or recurrent anemia required significantly more health care and had higher indices of disease activity, as well as lower average quality of life, than patients without anemia.

The prevalence of anemia in IBD according to systematic reviews ranges from 6% to 74% (9,20). A recent meta-analysis of European studies showed an overall anemia prevalence of 27% for CD and 21% for UC (11). Two recent Scandinavian studies showed significant decrease of the prevalence of anemia in IBD during the disease course (21,22). In contrast, Wiskin et al showed that 30% of pediatric IBD patients had persistent anemia two years after diagnosis (13).

Our study showed that one third of IBD patients had anemia at any time during the study period. These prevalence rates are similar to previous reports, but in marked contrast, we found only a small decrease in the prevalence of anemia in IBD patients over time (37.1% in 2009 and 33.2% in 2013), despite IBD treatment and iron supplementation. IBD-related therapy was not significantly different in patients with anemia compared to those without anemia with the exception of thiopurines. The more frequent use of thiopurines in patients without anemia compared to patients with anemia may be related to differences in the tolerability of these medications in patients with anemia.

Several clinical and serological markers have been extensively investigated in IBD for disease stratification, diagnostic association and to a lesser degree for disease prognostication. Although red cell parameters have been linked to the diagnosis of anemia or to IBD activity (23), little attention has been given to the presence of anemia as a marker of disease severity or disease course prediction. Rieder et al recently showed that presence of anemia in CD patients could serve as an independent predictor of disease related complications or surgeries (12). Our study shows that anemia is significantly correlated with disease severity and outcome. The presence of persistent/recurrent anemia was found to associate significantly with all the examined parameters of IBD-related health care utilization. There is evidence that IBD patients with disabling disease have significantly higher health care utilization and cost compared to IBD patients with mild disease or to those in remission (14, 24, 25). We also found a significant association between the anemia status and disease activity measured by clinical activity indices (HBI or UCAI) and biochemical markers (CRP and ESR). The presence of persistent/recurrent anemia was significantly correlated with all these parameters in the univariable analysis. However, in the multivariable analysis the statistical significance remained only for ESR. Multivariate analysis in UC patients showed significant correlation of persistent/recurrent anemia with UCAI and CRP whereas in CD no significant association between persistent/recurrent anemia and HBI or CRP was found. These rather unexpected differences between UC and CD could be related to variations in the type of anemia (iron deficiency vs anemia of chronic disease), which unfortunately we were not able to investigate more thoroughly in the present study. The higher rates of IBD-related operations in CD, which often include small bowel resection, could also contribute to the difference between UC and CD. Persistent/recurrent anemia was found in our study to be significantly associated with a history of IBD related surgeries, which are known to be more common in patients with severe disease. Finally we found that in our study population, IBD patients with anemia had significantly decreased quality of life scores as measured by SIBDQ compared to patients without anemia. The presence of persistent/recurrent anemia was independently negatively correlated with mean SIBDQ. Several previous studies have already established that disease severity is a major factor in the reduction of quality of life amongst IBD patients (24–26).

Our results also suggest that anti-TNF therapy despite its significant beneficial effects on disease activity and clinical outcomes, has only a modest effect on anemia. Data on the therapeutic effect of anti-TNF treatment on anemia in IBD patients is limited. A recent pediatric study in accordance to our results showed no significant differences in Hb levels between responders and non-responders to anti-TNF treatment (27). Moreover, we recently showed that anemia in IBD patients who are under anti-TNF treatment often persists and remains a significant manifestation of IBD even after one year of treatment (28).

The suggested criteria for the definition for disabling disease in IBD include hospitalization for flare-up or complications, presence of disabling chronic symptoms, need for immunosuppressive therapy or intestinal resection, or perianal surgery (3). The present study showed that persistent/recurrent anemia is significantly independently correlated with parameters considered as characteristics of disabling disease such as hospitalizations, continued active disease and IBD related surgeries. Based on these results the presence of persistent/recurrent anemia could be considered to be associated with disabling disease and probably as an important parameter in therapeutic decisions for IBD patients. Disabling disease is certainly the result of active and complicated IBD but according to our findings the presence of anemia and especially of persistent/recurrent anemia could serve as a marker for the appropriate management possibly preventing disabling course. Our results also emphasize that anemia should not be neglected in the general management of IBD patients and the appropriate treatment for anemia should be administered. We also found that IBD patients with persistent/recurrent anemia have more often active, extensive and complicated disease obviously as secondary manifestation. Based on these observational data we cannot support that treatment of anemia alone has any potential independent influence on the disease course but future prospective case-controlled studies are needed. IBD patients with persistent anemia should have a complete evaluation in order to characterize the type of anemia and exclude other causes of anemia. First line treatment in these cases should be IV iron replacement followed by erythropoiesis stimulating agents in patients with persistent anemia and characteristics of anemia of chronic disease.

This study has several strengths but it also has some limitations. First the study was conducted in a tertiary center and the study population might not be representative of the overall U.S. or international IBD general population. Biases related to the referral centers and selection of more severe IBD patients could be involved. Second the absence of enough data on the iron status of IBD patients did not permit investigation of possible differences concerning the type of anemia or to clarify how many of patients have characteristics of anemia of chronic disease which is useful information for their treatment.

In summary, anemia status in IBD patients may serve as a biomarker for assessment of disease severity and may be predictive of clinical outcome. The presence of persistent/recurrent anemia in IBD is independently correlated with parameters associated with disabling disease and with worse health related quality of life. Persistent/recurrent anemia for>3 years could be used as an objective marker of disabling disease in IBD helping to identify patients who need more aggressive management. Future studies in other tertiary or population-based cohorts should validate these results.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: Ioannis Koutroubakis was supported by a sabbatical salary of Medical Faculty University of Crete Greece; Benjamin Click was supported by NIDDK Grant 5T32DK063922-10 (PI: David C. Whitcomb MD PhD); Michael Dunn and David G. Binion were supported by a Grant W81XWH-11-2-0133 from the US Army Medical Research and Material Command.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence intervals

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- ED

Emergency department

- ESR

erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- HBI

Harvey-Bradshaw index

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IV

intravenous

- OD

odds ratio

- SIBDQ

short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire

- UC

ulcerative colitis

- UCAI

ulcerative colitis activity index

Footnotes

Writing assistance: None

Disclosures: Ioannis Koutroubakis Consulting/advisory board for Abbvie and MSD; Miguel Regueiro has served as a consultant for Abbvie, Janssen, Shire, Takeda, and UCB. David Binion Consulting/advisory board – Abbvie, Janssen, Cubist, Salix Steering committee FDA Safety Board – UCB Pharma Grant support – Janssen; The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Author Contributions: Ioannis E Koutroubakis: Study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. She has approved the final draft submitted. Claudia Ramos Rivers: Acquisition of data, analysis of data, critical revision of the manuscript, administrative and technical support. She has approved the final draft submitted. Miguel Regueiro: Acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript and study supervision. He has approved the final draft submitted. Efstratios Koutroumpakis: Acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript and study supervision. He has approved the final draft submitted. Benjamin Click: Acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript and study supervision. He has approved the final draft submitted. Robert E. Schoen Acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript and study supervision. He has approved the final draft submitted. Jana G. Hashash: Acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript and study supervision. She has approved the final draft submitted. Marc Swartz: Acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript and study supervision. He has approved the final draft submitted. Jason Swoger: Acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript and study supervision. He has approved the final draft submitted. Leonard Baidoo: Acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript and study supervision. He has approved the final draft submitted. Arthur Barrie, III: Acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript and study supervision. He has approved the final draft submitted. Michael Dunn: Acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript, and study supervision. He has approved the final draft submitted. David G. Binion: Mentor, study concept, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript and study supervision. He has approved the final draft submitted.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, et al. Disease activity courses in a regional cohort of Crohn’s disease patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:699–706. doi: 10.3109/00365529509096316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, et al. Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:3–11. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blonski W, Buchner AM, Lichtenstein GR. Clinical predictors of aggressive/disabling disease: ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2012;41:443–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levesque BG, Sandborn WJ, Ruel J, et al. Converging Goals of Treatment for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, from Clinical Trials and Practice. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:37–51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:763–86. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh A, Palmer R, Travis S. Mucosal healing as a target of therapy for colonic inflammatory bowel disease and methods to score disease activity. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2014;24:367–78. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein J, Dignass AU. Management of iron deficiency anemia in inflammatory bowel disease - a practical approach. Ann Gastroenterol. 2013;26:104–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oustamanolakis P, Koutroubakis IE, Kouroumalis EA. Diagnosing anemia in inflammatory bowel disease: beyond the established markers. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulnigg S, Gasche C. Systematic review: managing anemia in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1507–1523. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasche C, Berstad A, Befrits R, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of iron deficiency and anemia in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1545–1553. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filmann N, Rey J, Schneeweiss S, et al. Prevalence of anemia in inflammatory bowel diseases in european countries: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:936–45. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000442728.74340.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rieder F, Paul G, Schnoy E, et al. Hemoglobin and Hematocrit Levels in the Prediction of Complicated Crohn’s Disease Behavior – A Cohort Study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e104706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiskin AE, Fleming BJ, Wootton SA, et al. Anaemia and iron deficiency in children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:687–91. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramos-Rivers C, Regueiro M, Vargas EJ, et al. Association between telephone activity and features of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:986–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a working party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 (Suppl A):5–36. doi: 10.1155/2005/269076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn’s disease activity. Lancet. 1980;1:514. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92767-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kozarek RA, Patterson DJ, Gelfand MD, et al. Methotrexate induces clinical and histologic remission in patients with refractory inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:353–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-5-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Barton JR, et al. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire is reliable and responsive to clinically important change in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2921–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO, UNICEF, UNU. Report of a joint WHO/UNICEF/UNU consultation. World Health Organization; 1998. Iron Deficiency Anemia: Assessment, Prevention and Control. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson A, Reyes E, Ofman J. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Med. 2004;116(Suppl 7A):44S–49S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Høivik ML, Reinisch W, Cvancarova M, et al. Anaemia in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based 10-year follow-up. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:69–76. doi: 10.1111/apt.12541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sjöberg D, Holmström T, Larsson M, et al. Anemia in a Population-based IBD Cohort (ICURE): Still High Prevalence After 1 Year, Especially Among Pediatric Patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2266–70. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oustamanolakis P, Koutroubakis IE, Messaritakis I, et al. Measurement of reticulocyte and red blood cell indices in the evaluation of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibson PR, Weston AR, Shann A, et al. Relationship between disease severity, quality of life and health-care resource use in a cross-section of Australian patients with Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1306–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibson PR, Vaizey C, Black CM, et al. Relationship between disease severity and quality of life and assessment of health care utilization and cost for ulcerative colitis in Australia: A cross-sectional, observational study. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2014;8:598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalafateli M, Triantos C, Theocharis G, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a single-center experience. Ann Gastroenterol. 2013;26:243–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assa A, Hartman C, Weiss B, et al. Long-term outcome of tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonist’s treatment in pediatric Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:369–76. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koutroubakis IE, Ramos–Rivers C, Regueiro M, et al. The influence of anti-TNF agents on hemoglobin levels of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflam Bowel Dis. 2015 doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000417. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]