Abstract

Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a critical role in preventing autoimmune disease by limiting the effector activity of conventional T cells that have escaped thymic negative selection or cell-autonomous peripheral inactivation1–3. However, despite the substantial information available about the molecular players mediating Treg functional interference with auto-aggressive effector responses4,5, the relevant cellular events in intact tissues remain largely unexplored and the issues of whether Tregs prevent activation of self-specific T cells or function primarily to limit damage from such cells have not been addressed6. Here we have employed multiplex, high-resolution, quantitative imaging to reveal that within most secondary lymphoid tissues, Tregs expressing phosphorylated STAT5 (pSTAT5) and high amounts of the suppressive molecules CD73 and CTLA-4 exist in discrete clusters with rare IL-2 producing effector T cells activated by self-antigens. This local IL-2 production induces the STAT5 phosphorylation in the Tregs and is part of a feedback circuit that augments the suppressive properties of the Tregs to limit further autoimmune responses. Inducible ablation of TCR expression by Tregs reduces their regulatory capacity and disrupts their localization in such clusters, resulting in uncontrolled effector T cell responses. Our data thus reveal that autoreactive T cells reach a state of activation and cytokine gene induction on a regular basis, with physically co-clustering, TCR-stimulated Tregs responding to this activation in a feedback manner to suppress incipient autoimmunity and maintain immune homeostasis.

To explore how Tregs are organized in secondary lymphoid tissues, we utilized a newly developed method for high-resolution, multiplex examination of tissue sections termed Histo-cytometry7–9. This technique permits quantitative, spatially-resolved phenotyping of cells in tissue sections akin to analysis by flow cytometry, while also permitting measurement of activation state using anti-phosphopeptide reagents, and functional state using anti-cytokine antibodies.

pSTAT5+ Tregs exist as discrete clusters

We took advantage of prior observations showing that interleukin-2 (IL-2) is indispensible for maintaining Treg function in vivo10–12 by searching for pSTAT5+ T cells in sections from mouse lymph nodes (LN). In the steady state, we could detect pSTAT5 signals using flow cytometry primarily in a fraction of Foxp3+ Tregs present in diverse lymphoid organs (Extended Data Fig. 1a), as reported13. The pSTAT5 signals in Tregs were stringently dependent on IL-2, as they were completely eliminated after treatment with IL-2 blocking antibody (Extended Data Fig. 1a, b) and in IL-2 but not IL-15 knockout mice (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Using Foxp3-EGFP reporter mice14, we observed GFP+ Tregs distributed evenly in the T cell zone, whereas the pSTAT5+ Treg subset was less uniformly distributed, with many of these cells in a few discrete aggregates in the outer paracortical T cell region (Fig. 1a). 3-D analysis of 350 μm tissue sections clearly showed that a variable number of pSTAT5+ Tregs formed a small group with tightly associated cells in the center, which we term a cluster (Supplementary Video 1); this contrasted with the scattered pSTAT5+ Tregs described previously in spleen13. To quantify the imaging data, we performed Histo-cytometry. pSTAT5+ Tregs were extracted from raw images (Fig. 1b, left) with coordinates corresponding to their positions in the tissue (Fig. 1b, middle). The data were further transformed into a contour plot based on cell densities (Fig. 1b, right). pSTAT5+ Tregs clusters were then identified and the center of each cluster was determined. In addition to the uneven distribution of pSTAT5+ Tregs, we also found that the intensity of the pSTAT5 signal was heterogeneous among Tregs. There was a clear tendency for higher pSTAT5 signals in Tregs residing closer to the center of the cluster (Fig. 1c). Tregs less than 100 μm from the center showed significantly higher pSTAT5 intensity than did cells beyond that range (Fig. 1c). This strongly suggested that the source of IL-2 driving pSTAT5 generation was in the cluster center and indeed, we detected individual IL-2 producing cells surrounded by pSTAT5+ Tregs (Fig. 1d) in many, but not all, of such clusters. Among all the IL-2 producing cells we detected in situ, 75% were associated with Treg clusters (Extended Data Fig. 2); this is likely an underestimate given the sensitivity limitations of the imaging method and the temporal asynchrony of the responses. These in vivo data on the limited distance of strong pSTAT5 signals with respect to the cytokine producer cell agree with recent mathematical models of IL-2 signaling in tissues15.

Figure 1. pSTAT5+ Treg clusters in lymph nodes.

a, Immunofluorescence staining of an inguinal LN section from SPF Foxp3-EGFP mice. Arrows indicate representative pSTAT5+ Treg clusters. b, Extraction of pSTAT5+ Treg profiles from images of sections and further transformation of these data into a contour plot. c, The correlation between pSTAT5 intensity in Tregs and their distance to the nearest center of a pSTAT5+ cluster. Each dot indicates a pSTAT5+ Treg cell in (b). d, Localization of an IL-2 producing cell within a pSTAT5+ Treg cluster. e, Flow cytometry analysis of pSTAT5+ Tregs in different lymphoid organs from SPF and germ-free mice. iLN, inguinal LN; mLN, mesenteric LN. Each dot indicates a single mouse. Results are pooled from three independent experiments. f, Immunofluorescence staining of an inguinal LN section from germ-free mice. Arrows indicate representative pSTAT5+ Treg clusters. **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 in (c) as calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. ***p<0.001 in (e) as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test.

To identify the cells making IL-2 in the steady state we crossed RAG1−/− IL2GFP/GFP knock-in mice16 with wild type (WT) mice to generate IL2WT/GFP heterozygous mice, in which GFP expression from one allele allows for detection of IL-2 transcription, whereas the other cytokine–producing allele can protect the host from autoimmunity. The frequency of IL-2 producing cells in lymphoid tissues was extremely low (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Almost all the GFP+ cells expressed CD3 but were negative for CD1d-tetramer staining, indicating they were not NKT cells. More than 80% of GFP+CD3+ cells also expressed CD4, while fewer than 10% were CD8 positive (Extended Data Fig. S3b). Thus, our data indicate that CD4+ T cells are the major cell type producing IL-2 in the steady state, in accord with previous conclusions17–19.

T cells make IL-2 when the TCR stimulus reaches a certain threshold in the presence of co-stimulatory signals, mainly involving CD80/86 engagement of CD28 on the T cell20. Previous reports of CD4+ T cell production of IL-2 in the steady-state17–19 did not examine whether the stimulus came from commensal organisms, the largest source of “non-self” antigens presented by activated dendritic cells (DCs), or involved self-antigens presented by cells with adequate TCR ligand density and costimulatory properties even in the absence of microbial colonization. We therefore compared the number and nature of pSTAT5+ Treg clusters in the lymphoid tissues of conventional SPF vs. germ-free animals. Remarkably, the lymphoid tissues of germ-free mice showed as many, and in the spleen, more pSTAT5+ Tregs as compared to conventional animals (Fig. 1e). These clusters in germ-free animals were also similar in location and size to those of conventional SPF mice (Fig. 1f). This was true in skin-draining LN that would not be expected to be readily accessed by food-derived antigens, strongly suggesting that effector T cell activation for IL-2 production is driven by self-antigens. These latter findings indicate that even in the presence of functional Tregs and absence of overt autoimmunity or discrete microbial stimuli, a small fraction of T cells can still be sufficiently activated by self-antigens to become IL-2 secreting proto-effector T cells. Such activation likely requires active suppression by Tregs to prevent tissue damaging responses, consistent with the evidence that Treg depletion in germ-free animals results in a severe lymphoproliferative disease and immune mediated inflammation21.

Preferential role of migratory DC in Treg clustering

Based on prior observations using intravital 2-photon microscopy showing migration arrest of T cells upon TCR engagement22,23, the tight clustering of Tregs and effector T cells suggested that they were interacting with antigen-presenting cells, presumably DCs, via self-ligand engagement by their TCR or following recent TCR-induced integrin affinity up-regulation24. Indeed, CD11c+MHC-II+ DCs could be directly observed in tight association with most Treg clusters (Fig. 2a). Given that the majority of Treg clusters were localized in the outer T cell zone paracortex and interfollicular regions (Fig. 1a), our previous demonstration of differential DC subset positioning in steady state LN7 suggested that specific DC populations might be preferentially involved in cluster formation. Histo-cytometry showed that Treg clusters were predominantly localized in LN regions densely populated with CD11cdimMHC-IIhigh migratory DCs (Extended Data Fig. 4a upper row, Fig. 2b). Quantitative analysis (Extended Data Fig. 4b) revealed a statistically significant preferential association of Treg clusters with migratory DCs (Fig. 2c). Consistent with these data, higher MHC-II expression on such migratory cells is also likely to correlate with greater self-antigen presentation to T cells, as well as with increased CD80/86 expression, thus making these DC excellent candidates for driving proto-effector activation. In accord with this notion, Histo-cytometry indicated that there was a higher percentage of CD86high DCs within Treg clusters than among DCs not associated with such clusters (Extended Data Fig. 5). Finer grained analysis showed that Tregs were able to cluster with various DC subsets, with a preference for CD11b+ migratory DCs (Fig. 2d). Together, these data show that in the steady state, self-reactive effector T cells co-aggregate with Tregs around a select population of mainly migratory DCs presenting self-antigens.

Figure 2. Preferential role of migratory DC in Treg clustering.

a, A representative image showing association of a Treg cluster with a CD11c+MHC-II+ DC (arrow). b, Distribution of Treg clusters and different DC subsets in an inguinal LN section from a Foxp3-EGFP mouse. Creation of surfaces for each cell type was performed based on immunofluorescence staining and subsequent Histo-cytometry analysis as shown in Fig. S4A. Treg clusters were determined by setting a threshold for the volume within Treg surfaces created in the EGFP channel without object splitting. c, Quantification of the percentages of migratory DCs associated with Treg clusters. Each dot indicates a section, with a total of 6 sections from 3 LN analyzed. d, Phenotypic characterization of DCs associated with pSTAT5+ and pSTAT5− Treg clusters (n=6, 6 LN from 6 mice, mean+/−s.e.m., pooled from 2 experiments). ***p<0.001 in (c) as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test. *p < 0.05 in (d) as calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test.

High suppressive phenotype of clustered Tregs

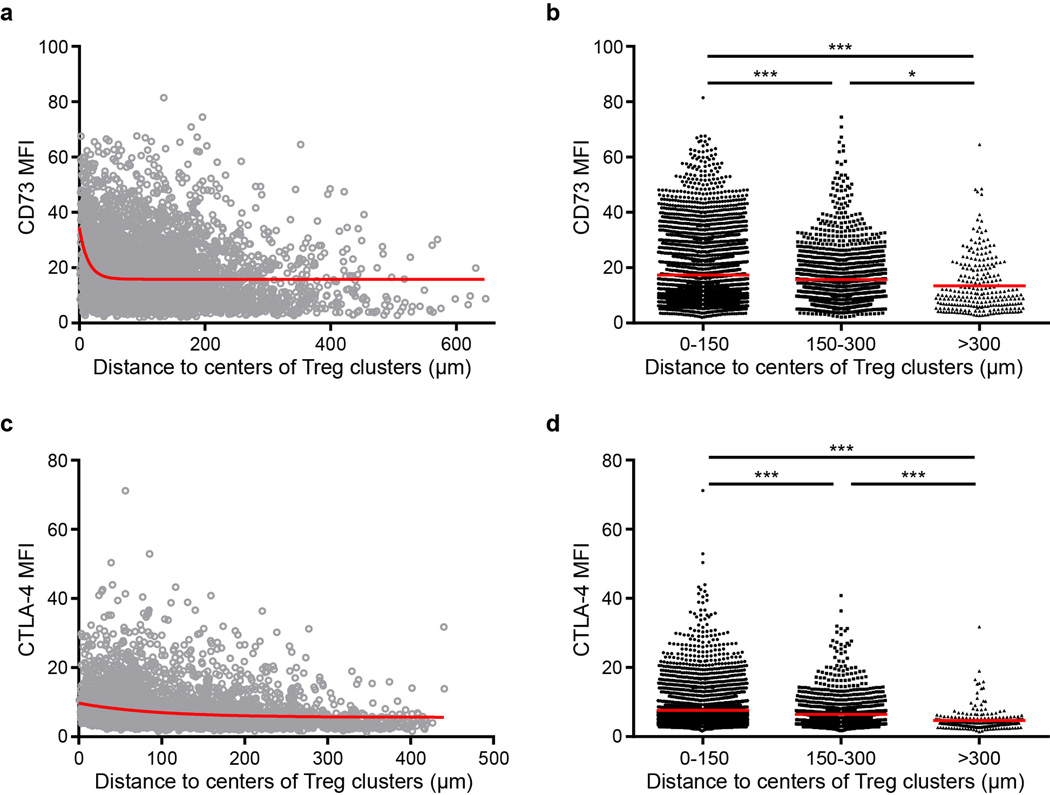

The known role of Tregs in maintenance of immune homeostasis under steady-state conditions implies that there should be continuous successful suppression of the col-localized activated T cells to prevent their becoming the source of an uncontrolled autoimmune response. Treg suppression of effector T cell responses has been reported to involve diverse molecular mechanisms, including generation of adenosine via CD39/CD73 expression25,26, competition for IL-227, and interference with costimulatory molecule engagement of CD28 on proto-effector T cells through the expression of CTLA-4 by the Tregs28,29. Histo-cytometry revealed that the majority of CD73high Tregs localized along the T-B border (Fig. 3a,b), an area also enriched for pSTAT5+ Treg clusters and MHC-IIhigh DCs. Furthermore, CD73 expression level on Tregs was positively associated in a significant manner with their distance to the center of cluster (Extended Data Fig. 6a,b). The Tregs in the clusters showed the highest levels of CD73 amongst all LN Tregs (Fig. 3e, f). CTLA-4 expression showed a similar distribution pattern (Extended Data Fig. 6c,d and Fig. 3c,d,g,h). Thus, the highest expression of inhibitory molecules is on Tregs within the clusters, consistent with these cells being the most adept at constraining effector T cell responses.

Figure 3. Highly suppressive phenotype of clustered Tregs.

a, Immunofluorescence staining of CD73 in a popliteal LN section from a Foxp3-EGFP mouse. CD73 signals were gated on EGFP+ Tregs. Yellow dots indicate the distribution of CD73high Tregs. b, The correlation between CD73 intensity of Tregs and the distance of the Tregs to the center of LN. Each dot indicates a Treg cell shown in (a). c, Immunofluorescence staining of CTLA-4 in a popliteal LN section from a Foxp3-EGFP mouse. CTLA-4 signals were gated on EGFP+ Tregs. Yellow dots indicate the distribution of CTLA-4high Tregs. d, The correlation between CTLA-4 intensity of Tregs and the distance of these Tregs to the center of LN. Each dot indicates a Treg cell shown in (c). (E) Representative images showing CD73 staining in Treg clusters. Arrows indicate Treg clusters. f, Quantification of CD73 expression on Tregs inside or outside of clusters (n=4, 4 LN from 4 mice). Results are representative of two independent experiments. g, Representative images showing CTLA-4 staining in Treg clusters. Arrows indicate Treg clusters. h, Quantification of CTLA-4 expression on Tregs inside or outside of clusters (n=4, 4 LN from 4 mice). Results are representative of two independent experiments. ***p<0.001 in (b, d) as calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. **p<0.01 in (f, h) as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test.

Role of Treg TCR expression in clustering and suppression

The tight conjugation of Tregs to DCs in the clusters implied that they were actively recognizing or had very recently recognized TCR ligands presented by DCs. Depriving mature Tregs of TCR expression results in rampant autoimmunity within a few weeks without gross diminution in the overall Treg number in the animals, indicating that post-thymic Tregs need TCR expression to mediate their suppressive function30,31. Together, these data suggested that TCR engagement might contribute to effective Treg activity by participating in the co-localization of Treg with proto-effectors associated with stimulatory DC, as well as also possibly signaling the Treg to adopt a more suppressive state. To investigate this possibility, TracFL mice were crossed with Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 mice to enable tamoxifen-inducible deletion of TCRa specifically in Tregs30. Mice were treated with tamoxifen on days 0 and 1, and sacrificed for analysis on day 7. The majority of Tregs (~ 70%) lost surface expression of TCRa in TracFL/FLFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 mice after tamoxifen treatment (Fig. 4a) but they remained in the T zone with unchanged overall density (Fig. 4b,c). However, the loss of TCR expression led to a striking difference in Treg spatial distribution of TCRaWT/WTFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 vs. TCRaFL/FLFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 mice. The fraction of Tregs in discrete clusters diminished in the LN of the treated FL/FL mice (Fig. 4b,d). Furthermore, Tregs became a substantially smaller fraction of the cells in pSTAT5+ clusters (Fig. 4b,e). The latter change was not accompanied by an overall loss of pSTAT5+ Tregs in the LN (Fig. 4f), in agreement with prior observations by flow cytometry30. Thus, acute loss of TCR signaling in Tregs was co-incident with a failure of these cells to form discrete clusters, with enhanced IL-2 production and signaling among proto-effector T cells, and with a loss of spatial constraint in IL-2 signaling in Tregs. We then compared the expression of CD73 and CTLA-4 by T cells of TCRaWT/WTFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 vs. TCRaFL/FLFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 animals after tamoxifen treatment (Extended Data Fig. 7). The bulk population showed a small but significant change in mean CD73 (Extended Data Fig. 7a, b left) or CTLA-4 (Extended Data Fig. 7c, d left) expression, and the highest expressing cells among Tregs were diminished substantially in the TCR-deleted animals. Furthermore, the high expressing cells lost in the absence of Treg TCR engagement were those found preferentially in peripheral clusters in WT animals (Extended Data Fig. 7b right and 7d right). These data on the selective reduction in Tregs with the greatest capacity for suppression are consistent with the loss of Treg control of effector function in the tamoxifen-treated FL/FL mice30,31.

Figure 4. Role of Treg TCR expression in clustering and suppression.

a, Detection of TCRa on CD4+ LN T cells from TracWT/WTFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 and TracFL/FLFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 mice 7 days after tamoxifen treatment. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate the percentages of cells in each area. b, Immunofluorescence staining of mesenteric LN sections from TracWT/WTFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 (upper panel) and TracFL/FLFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 (lower panel) mice treated as in (a). Quantification of Treg density in T cell zone (c), percentage of Tregs forming clusters (d), Treg density in pSTAT5+ clusters (e), and percentage of pSTAT5+ Tregs (f). mLN, mesenteric LN; iLN, inguinal LN; panLN, pancreatic LN. Each dot indicates a section, and each type of LN includes 6 sections from 2 LN from 2 individual mice. **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test.

Role of IL-2 feedback in Treg-mediated suppression

Due to very high CD25 expression and miR-155 dependent repression of SOCS132, Tregs have an advantage over normal T cells in capturing and responding to IL-2 secreted within the clusters. Thus, in addition to depriving effector T cells of access to their own IL-2, which is important for effector T cell differentiation33, we speculated that this ready capture of IL-2 by the Tregs might play an important role in enhancing their local suppressive function beyond that dependent on TCR engagement. To test this hypothesis, we first blocked IL-2 in the steady state in IL2WT/GFP heterozygous mice by injecting IL-2 neutralizing antibody. IL-2 blockade for 8 days did not grossly affect Treg numbers (Fig. 5a). However, there was a significant increase in both the frequency and the total number of IL-2/GFP+ CD4+ polyclonal T cells in spleen and LN under these conditions (Fig. 5b), consistent with the loss of IL-2 stimulation of Tregs freeing conventional T cells for stronger responses to self-or environmental antigens. These findings are consistent with the idea that IL-2 could be playing a critical negative feedback role under normal conditions, informing Tregs of incipient autoimmune responses of conventional T cells and by increasing the suppressive activity of the Tregs, constraining such potentially damaging responses. To examine this possibility, we employed a cell transfer system involving pigeon cytochrome c (PCC)-specific 5C.C7 TCR transgenic T cells (5C.C7 T cells). PCC peptide-pulsed splenic DCs were transferred into WT mice possessing a full repertoire of Tregs and normal endogenous levels of IL-2. Eighteen hours after DC transfer, alternately labeled polyclonal CD4+ T cells and WT or IL-2 deficient 5C.C7 T cells were transferred into host animals. In this experimental system, endogenous Tregs in the draining popliteal LN can sense locally generated IL-2 secreted by activated WT 5C.C7 T cells but are blind to such cytokine feedback sensing with respect to the IL-2 KO 5C.C7 T cells. Twenty-four hours after 5C.C7 T cells transfer, we could find large clusters of blasting IL-2 KO 5C.C7 T cells binding to antigen-pulsed DCs, whereas smaller 5C.C7 clusters were observed in LN of mice transferred with WT cells (Fig. 5c). Consistent with this finding, intravital 2P microscopy revealed a significantly longer interaction time between IL-2 KO 5C.C7 T cells and DCs (Supplementary video 2 and Fig. 5d) as compared to WT 5C.C7 T cells. Taken together, and consistent with previous report34, these observations all support a critical role for IL-2-mediated feedback enhancement of Treg suppressive function in controlling ongoing self-stimulation of proto-effector T cells and maintaining immune tolerance.

Figure 5. Role of IL-2 feedback in Treg-mediated suppression.

a, Quantification of percentages and absolute numbers of Tregs in IL-2WT/GFP reporter mice treated with isotype control Ab or IL-2 neutralizing Ab (1 mg per mouse daily) for 8 days. b, Left panel: representative flow data showing detection of GFP+CD4+ cells in different lymphoid organs from IL-2WT/GFP reporter mice treated as in (a); right panel: Quantification of percentages and absolute numbers of GFP+CD4+. Each dot in (a, b) indicates a single mouse. Results are representative of two independent experiments. c, Confocal imaging of popliteal LN 24 hours after transfer with PCC peptide loaded splenic DCs and WT or IL-2−/− 5C.C7 transgenic RAGII−/− T cells. d, Quantification of interaction time between DCs and WT or IL-2−/− 5C.C7 transgenic RAGII−/− T cells from 4 independent 2P intravital imaging experiments. To control experimental preparation and to permit data comparison between different experiments, polyclonal T cells were co-transferred with each type of 5C.C7 cells. See also Movie 2. e, Cellular interaction time for individual cells pooled from 4 experiments. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05 in (a, b) as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test. ***p<0.001 and ns in (d, e) as calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test.

Discussion

Our detection of pSTAT5+ Tregs that arise in response to IL-2 secreted by activated CD4+ T cells under steady-state conditions is inconsistent with the view that the immune system is kept in an “off” state by tonic action of Tregs that prevents activation of self-reactive T cells. Rather, Tregs appear to operate at least in large measure to constrain the latter’s expansion and development into damaging effectors. There is a substantial risk difference between a system in which T cells only activate to self in the absence of Tregs and one in which the latter limit damage from already activated anti-self T cells. These new findings showing the constant entry of auto-responsive cells into a true activated state also account for the very rapid onset of autoimmune disease when Tregs are removed from the system or made ineffective by eliminating IL-2 feedback control or the capacity to act locally through TCR-dependent clustering30,31.

We also observed pSTAT5− Treg clusters in the LN, which may suggest either an absence of effector T cells in the cluster or that activation and cytokine production by the proto-effector has already ceased. Both possibilities may exist in the steady state, as Tregs can either suppress the on-going activation of effector T cells interacting with the same DC, or prevent some pre-effector T cells from binding to DCs by maintaining DCs in a less stimulatory state35,36.

Continuous TCR signaling plays a critical role in Treg function in the periphery. Such signaling may act to maintain or induce the expression of genes whose products are required for effective suppression. Our data suggest that TCR signaling is probably also required for effective control of autoimmunity by promoting the co-localization of Tregs with target T effectors on a DC platform. This process allows Tregs to stay together long enough with effector T cells to accomplish suppression, it maximizes the effects of inhibitory mechanisms, especially for membrane molecules and soluble factors with a limited working distance, and it promotes acquisition of enhanced suppressor capacity as evidenced by the high expression of CD73 and CTLA4 by clustered Tregs. These insights reveal the strategy used by Tregs to maintain effective tolerance, placing past observations on molecular mechanisms in an in vivo context that highlights the role of spatial proximity in this critical immunoregulatory process.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6, and IL15−/−, mice were obtained from Taconic Laboratories. Foxp3-EGFP, B10.A CD45.2−, B10.A CD45.2+ 5C.C7 TCR-transgenic RAG2−/−, B10.A CD45.2+ 5C.C7 TCR-transgenic RAG2−/−IL2−/−, RAG1−/−, and IL2GFP/GFP KI RAG1−/− mice were obtained from Taconic Laboratories through a special NIAID contract. IL2GFP/GFP RAG1−/− mice were crossed to C57BL/6 mice to generate IL2WT/GFP heterozygous mice. IL2−/− mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. All the above mice were maintained in SPF conditions at an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited animal facility. Germ-free C57BL/6 mice were kindly provided by Dr. Yasmine Belkaid (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). TCRaWT/WTFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 and TCRaFL/FLFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 mice were generated as previously described30. Six to ten week old sex-matched mice were used for all experiments, and were randomly allocated into treatment groups. No blinding was performed for animal experiments in this study. For tamoxifen administration, mice were given oral gavage of 200 μl tamoxifen emulsion per treatment on day 0 and 1, and sacrificed for analysis on day 7. All procedures were approved by the NIAID Animal Care and Use Committee (NIH).

Flow cytometry

Cells were isolated from lymphoid organs as indicated and stained with anti-CD3 (17A2; Biolegend), anti-CD4 (L3T4; Biolegend), anti-CD8 (53-6.7; Biolegend), anti-Foxp3 (150D; Biolegend), anti-TCRb (H57-597; Biolegend), anti-GFP (Life Technologies) and CD1d-tetramer (NIH Tetramer facility). For pSTAT5 staining, cells were fixed using BD Cytofix™ Fixation Buffer (10 minutes at 37°C), permeabilized in BD Phosflow™ Perm Buffer III (30 minutes on ice) and stained with anti-pSTAT5 (47/Stat5; BD Biosciences). Flow cytometric data were collected on an LSR II (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

IL-2 neutralization

For examining the role of IL-2 in pSTAT5 signals in Tregs, mice were injected i.v. with 1 mg anti-IL2 (S4B6-1; BioXcell) or isotype control antibody (2A3; BioXcell) 24 hours before sacrifice. For examining the role of IL-2 in Treg function, IL2WT/GFP mice were treated i.p. with 1mg anti-IL-2 or isotype control daily for 8 days before analysis.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal imaging

Lymph nodes were harvested and fixed using fixation buffer containing 1% PFA for 12 hours, then dehydrated in 30% sucrose prior to embedding in OCT freezing media (Sakura Finetek). 20 μm sections were prepared with a Leica cryostat and blocked with a blocking buffer containing 1% normal mouse serum, 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 hour. Sections were stained with directly conjugated antibodies or appropriate primary and secondary antibodies for 3 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C in a dark, humidified chamber.

For whole mount staining, 350 μm LN sections were made with Leica VT1000 S Vibrating blade microtome and blocked for 8 hours, followed by staining with antibodies diluted in the blocking buffer for 48 hours at 4°C on a shaker. Tissue clearing was performed as previously detailed37.

The following antibodies were used for staining: anti-B220 (RA3-6B2; Biolegend), anti-CD3 (17A2; Biolegend), anti-CD8 (53-6.7; Biolegend), anti-Foxp3 (FJK-16s; eBioscience), anti-IL2 (JES6-5H4; eBioscience), anti-GFP (Life Technologies), anti-CD11c (N418; Biolegend), anti-MHCII (M5/114.15.2; Biolegend), anti-CTLA4 (UC10-4B9; Biolegend), anti-CD73 (TY/11.8; Biolegend), anti-CD11b (5C6; AbD Serotec), anti-CD86 (AP-MAB0803; Novus Biologicals) and anti-pSTAT5 (C11C5; Cell Signaling Technology).

Images were acquired on a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope or a Leica Sp8 confocal microscope.

Adoptive cell transfer and 2P intravital imaging

Cell preparation and adoptive transfer were performed as previously described23. Briefly, splenic DCs were purified from B10.A CD45.2− mice using CD11c microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Polyclonal CD4+ T cells from LNs of B10.A CD45.2− and TCR transgenic 5C.C7 CD4+ T cells from WT or IL2−/− B10.A CD45.2+ 5C.C7 TCR-transgenic RAG2−/− mice were purified by negative immunomagnetic cell sorting (Miltenyi Biotec). DCs were incubated in vitro with PCC peptide (10 μM pPCC, American Peptide Company) and LPS (1.0 μg/ml, Invivogen) for 4 hours at 37°C before s.c. injection at 1 × 106/footpad. CD4+ T cells were transferred by i.v. injection at 2 × 106/recipient 18 hours post-transfer of DCs.

For 2P intravital imaging, DCs were stained with 100 μM CTB (7-amino-4-chloromethylcoumarin, Molecular Probes), polyclonal CD4+ T cells were stained with 1.25 μM CMFDA (5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate, Molecular Probes), and WT or IL2−/− TCR transgenic 5C.C7 CD4+ T cells were stained with 1.25 μM CMTPX (Molecular Probes). 24 hours after T cell transfer, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and popliteal LNs were surgically exposed. Imaging was performed on a Zeiss 710 microscope equipped with a Chameleon laser (Coherent) tuned to 800 nm in combination with a 20× water-dipping lens (NA 1.0, Zeiss) using Zen 2010 acquisition software.

Histo-cytometry

Histo-cytometry analysis was performed as previously described7–9, with minor modifications. In brief, multi-parameter confocal images were corrected for fluorophore spillover using the Leica Channel Dye Separation module. Due to high spatial resolution of the 63× 1.4 NA objective, deconvolution was not performed. For analysis of DC subsets associated with Treg clusters, all LN regions with visible Treg cell clusters were first imaged, with individual files then recombined into a single composite file representing each LN. To identify Treg clusters, The Foxp3-EGFP channel was used for Treg surface creation with zero object splitting (Imaris, Bitplane). Treg surfaces with a volume above a certain threshold were considered as Treg clusters. These Treg clusters were then separated based on pSTAT5 mean intensity parameter to isolate discrete pSTAT5+ and pSTAT5− Treg clusters, which were then used to create new binary pSTAT5+ and pSTAT5− Treg cluster channels. DC surfaces were created based on a newly generated DC channel (DC = CD11c + MHC-II - CD3/B220). DCs that associate with Treg clusters were determined by gating on DC surfaces positive for intensity in the already created pSTAT5+ or pSTAT5− Treg cluster channels. DC surface marker gating within CD11c+MHC-II+CD3−B220− voxels was then performed as previously described7. Finally, the object statistics were exported into FlowJo X (TreeStar Inc.) for analysis and graphing (Prism, Graphpad).

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test was used for the statistical analysis of multiple groups. Student’s t test (two-tailed) was used for the statistical analysis of differences between two groups. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size.

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, and ns (not statistically significant).

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Role of IL-2 in induction of pSTAT5 in Tregs.

a, Representative flow data showing pSTAT5 staining of Tregs from lymphoid organs as indicated after treatment with isotype Ab or IL-2 neutralizing Ab (1 mg per mouse) for 24 hours. The numbers in the quadrants indicate the percentages of cells in each quadrant. pLN, Popliteal LN; iLN, inguinal LN; mLN, mesenteric LN. b, Quantification of pSTAT5+ Tregs. Results are representative of two independent experiments. c, Detection of pSTAT5+ Tregs in WT, IL-2 KO and IL-15 KO mice. The numbers in the quadrants indicate the percentages of cells in each quadrant. Results are representative of two independent experiments. ***p<0.001 as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test.

Extended Data Figure 2. Spatial correlation between IL-2+ cells and pSTAT5+ Treg clusters.

a, A positive control showing immunofluorescence staining of IL-2 in situ, and the comparison of IL-2 detection sensitivity between flow cytometry and Histo-cytometry. OVA323-339 peptide loaded splenic DCs (cyan) were stained with CMTMR and injected into the footpad, and RAG2−/− TCR transgenic OT-II CD4+ T cells (green) stained with CMFDA were transferred 18 hours post-transfer of DCs. For each recipient, 16 hours after T cell transfer, one draining popliteal LN was isolated for IL-2 (red) immunofluorescence staining, while the contralateral one for intracellular IL-2 staining ex vivo. Each dot in the middle panel of the upper row indicates a LN. *p < 0.05 as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test. b, Immunofluorescence staining of IL-2 and pSTAT5 in LN from EGFP-Foxp3 reporter mice. Upper row indicates an IL-2+ cell associated with clustered Tregs among a group of pSTAT5+ Tregs. Lower row indicates an unassociated IL-2+ cell surrounded by a group of pSTAT5+ Tregs. c, Quantification of IL-2+ cells associated or unassociated with Treg clusters. Data are pooled from 7 LN.

Extended Data Figure 3. Phenotypic characterization of IL-2-producing cells in the steady state in IL-2WT/GFP heterozygous mice.

a, Representative flow data showing the phenotypes of cells from inguinal LN of WT or IL-2WT/GFP heterozygous mice. b, Quantification of the percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ cells within GFP+CD3+ population from different lymphoid organs (n=3, mean+/−s.e.m.). iLN, inguinal LN; mLN, mesenteric LN.

Extended Data Figure 4. Histo-cytometry analysis of DC subsets associated with Treg clusters.

a, Immunofluorescence staining of an inguinal LN section from Foxp3-EGFP mice (upper row) and Histo-cytometry analysis of DC subsets (lower row). Surfaces for each identified DC subset are shown in Fig. 2b. Briefly, DC surfaces were created based on a new channel (DC = CD11c + MHC-II -CD3/B220), and DC surface markers (CD11c, MHC-II, CD11b and CD8) were gated within CD11c+MHC-II+CD3−B220− voxels to exclude non-DCs. b, Gating strategy for the phenotypic characterization of DC subsets associated with pSTAT5+ or pSTAT5− Treg clusters.

Extended Data Figure 5. CD86 expression on DCs associated with Treg clusters.

a, Representative images showing immunofluorescence staining of CD86 in LN from EGFP-Foxp3 reporter mice. b, Histo-cytometry analysis of CD11c, MHC-II, and CD86 expression for DCs associated or unassociated with Treg clusters. c-d, Quantification of percentages of CD86high (c) and CD86 MFI (d) in different DC subsets. Each dot indicates a section. 6 sections from 3 inguinal LN. ***p<0.001 in (c) as calculated by two-tailed Student’s t test. ***p<0.001 and ns in (d) as calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test.

Extended Data Figure 6. The correlation between CD73/CTLA-4 expression on Tregs and their distance to the center of Treg clusters.

Regression analysis of CD73 (a, b) and CTLA-4 (c, d) based on images shown in Fig. 3e, g. Each circle in (a, c) or each dot in (b, d) indicates a Treg cell. The red lines in (a, c) indicate the trend lines. ***p < 0.001 and *p < 0.05 as calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test.

Extended Data Figure 7. Role of TCR signaling in high expression of CD73 and CTLA-4 in Tregs.

Immunofluorescence staining of CD73 (a) and CTLA-4 (c) in mesenteric LN sections from TracWT/WTFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 and TracFL/FLFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 mice 7 days after tamoxifen treatment. CD73 and CTLA-4 signals were gated on EGFP+ Tregs. (b, d) Histo-cytometry analysis of CD73 and CTLA-4 MFI in indicated cell populations from the sections shown in (a, c). Error bars represent mean+/−SD. The dots in the yellow rectangles in the left panels indicate CD73high or CTLA-4high Tregs. The right panels in (b, d) show the distribution pattern of the gated WT CD73high and CTLA-4high Tregs (in left panels) in sections. Arrows indicate CD73high and CTLA-4high Tregs in representative clusters. ***p < 0.001 as calculated by One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Video 1. Visualization of a pSTAT5+ Treg cluster in 3D. Immunofluorescence staining of a 350 μm thick inguinal LN section from Foxp3-EGFP mice. Green indicates EGFP+ Tregs, red indicates pSTAT5 signals, and cyan indicates B220+ cells.

Supplementary Video 2. 2P intravital imaging of interaction between DCs and WT or IL-2−/− 5C.C7 transgenic RAGII−/− T cells. WT or IL-2−/− 5C.C7 transgenic RAGII−/− T cells (green) were each co-transferred with polyclonal CD4+ T cells (blue) into distinct WT host mice, 18 hours post-transfer of PCC peptide loaded splenic DCs (red). Imaging was performed 24 hours after T cell transfer.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Yasmine Belkaid for providing germ-free mice. We also would like to thank members of the LBS, LSB for their helpful comments during the course of these studies and critical input during preparation of this manuscript. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIAID, NIH and by the US National Institutes of Health (R37AI034206 to A.Y.R.; T32GM007739 to A.G.L.), the Ludwig Cancer Center at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (A.Y.R.), and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (A.Y.R.).

Footnotes

Contributions

Z.L. designed and conducted most of the experiments, data analysis, and drafted the manuscript; M.Y.G. performed the analysis of DC phenotype and provided assistance with Histo-cytometry studies; N.V.P. conducted 2P intravital imaging experiments; A.G.L. and A.Y.R. created TCRaWT/WTFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 and TCRaFL/FLFoxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 mice, generated tissue samples from tamoxifen treatment of these mice, and discussed data interpretation; R.N.G. helped design experiments, interpret data, and with input from all other authors, develop the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Benoist C, Mathis D. Treg cells, life history, and diversity. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2012;4:a007021. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annual review of immunology. 2012;30:531–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xing Y, Hogquist KA. T-cell tolerance: central and peripheral. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2012;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2008;8:523–532. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shevach EM. Mechanisms of foxp3+ T regulatory cell-mediated suppression. Immunity. 2009;30:636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Germain RN. Maintaining system homeostasis: the third law of Newtonian immunology. Nature immunology. 2012;13:902–906. doi: 10.1038/ni.2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerner MY, Kastenmuller W, Ifrim I, Kabat J, Germain RN. Histo-cytometry: a method for highly multiplex quantitative tissue imaging analysis applied to dendritic cell subset microanatomy in lymph nodes. Immunity. 2012;37:364–376. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerner MY, Torabi-Parizi P, Germain RN. Strategically localized dendritic cells promote rapid T cell responses to lymph-borne particulate antigens. Immunity. 2015;42:172–185. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radtke AJ, et al. Lymph-Node Resident CD8alpha+ Dendritic Cells Capture Antigens from Migratory Malaria Sporozoites and Induce CD8+ T Cell Responses. PLoS pathogens. 2015;11:e1004637. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nature immunology. 2005;6:1142–1151. doi: 10.1038/ni1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Cruz LM, Klein L. Development and function of agonist-induced CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in the absence of interleukin 2 signaling. Nature immunology. 2005;6:1152–1159. doi: 10.1038/ni1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng G, Yu A, Malek TR. T-cell tolerance and the multi-functional role of IL-2R signaling in T-regulatory cells. Immunological reviews. 2011;241:63–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smigiel KS, et al. CCR7 provides localized access to IL-2 and defines homeostatically distinct regulatory T cell subsets. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014;211:121–136. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bettelli E, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofer T, Krichevsky O, Altan-Bonnet G. Competition for IL-2 between Regulatory and Effector T Cells to Chisel Immune Responses. Frontiers in immunology. 2012;3:268. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naramura M, Hu RJ, Gu H. Mice with a fluorescent marker for interleukin 2 gene activation. Immunity. 1998;9:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80603-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Setoguchi R, Hori S, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi S. Homeostatic maintenance of natural Foxp3(+) CD25(+) CD4(+) regulatory T cells by interleukin (IL)-2 and induction of autoimmune disease by IL-2 neutralization. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;201:723–735. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Almeida AR, Zaragoza B, Freitas AA. Indexation as a novel mechanism of lymphocyte homeostasis: the number of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells is indexed to the number of IL-2-producing cells. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:192–200. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amado IF, et al. IL-2 coordinates IL-2-producing and regulatory T cell interplay. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:2707–2720. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell JD, Ragheb JA, Kitagawa-Sakakida S, Schwartz RH. Molecular regulation of interleukin-2 expression by CD28 co-stimulation and anergy. Immunological reviews. 1998;165:287–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chinen T, Volchkov PY, Chervonsky AV, Rudensky AY. A critical role for regulatory T cell-mediated control of inflammation in the absence of commensal microbiota. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207:2323–2330. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mempel TR, Henrickson SE, Von Andrian UH. T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature. 2004;427:154–159. doi: 10.1038/nature02238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Panhuys N, Klauschen F, Germain RN. T-cell-receptor-dependent signal intensity dominantly controls CD4(+) T cell polarization In Vivo. Immunity. 2014;41:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Lim D, Rudd CE. Immunopathologies linked to integrin signalling. Seminars in immunopathology. 2010;32:173–182. doi: 10.1007/s00281-010-0202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deaglio S, et al. Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:1257–1265. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobie JJ, et al. T regulatory and primed uncommitted CD4 T cells express CD73, which suppresses effector CD4 T cells by converting 5'-adenosine monophosphate to adenosine. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:6780–6786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandiyan P, Zheng L, Ishihara S, Reed J, Lenardo MJ. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce cytokine deprivation-mediated apoptosis of effector CD4+ T cells. Nature immunology. 2007;8:1353–1362. doi: 10.1038/ni1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Read S, et al. Blockade of CTLA-4 on CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells abrogates their function in vivo. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:4376–4383. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wing K, et al. CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science. 2008;322:271–275. doi: 10.1126/science.1160062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine AG, Arvey A, Jin W, Rudensky AY. Continuous requirement for the TCR in regulatory T cell function. Nature immunology. 2014;15:1070–1078. doi: 10.1038/ni.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vahl JC, et al. Continuous T cell receptor signals maintain a functional regulatory T cell pool. Immunity. 2014;41:722–736. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu LF, et al. Foxp3-dependent microRNA155 confers competitive fitness to regulatory T cells by targeting SOCS1 protein. Immunity. 2009;30:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liao W, Lin JX, Leonard WJ. Interleukin-2 at the crossroads of effector responses, tolerance, and immunotherapy. Immunity. 2013;38:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Gorman WE, et al. The initial phase of an immune response functions to activate regulatory T cells. Journal of immunology. 2009;183:332–339. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Q, et al. Visualizing regulatory T cell control of autoimmune responses in nonobese diabetic mice. Nature immunology. 2006;7:83–92. doi: 10.1038/ni1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tadokoro CE, et al. Regulatory T cells inhibit stable contacts between CD4+ T cells and dendritic cells in vivo. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:505–511. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erturk A, et al. Three-dimensional imaging of solvent-cleared organs using 3DISCO. Nature protocols. 2012;7:1983–1995. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Video 1. Visualization of a pSTAT5+ Treg cluster in 3D. Immunofluorescence staining of a 350 μm thick inguinal LN section from Foxp3-EGFP mice. Green indicates EGFP+ Tregs, red indicates pSTAT5 signals, and cyan indicates B220+ cells.

Supplementary Video 2. 2P intravital imaging of interaction between DCs and WT or IL-2−/− 5C.C7 transgenic RAGII−/− T cells. WT or IL-2−/− 5C.C7 transgenic RAGII−/− T cells (green) were each co-transferred with polyclonal CD4+ T cells (blue) into distinct WT host mice, 18 hours post-transfer of PCC peptide loaded splenic DCs (red). Imaging was performed 24 hours after T cell transfer.