Abstract

Background

In utero alcohol, or ethanol, exposure produces developmental abnormalities in the brain of the fetus, which can result in lifelong behavioral abnormalities. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) is a term used to describe a range of adverse developmental conditions caused by ethanol exposure during gestation. Children diagnosed with FASD potentially exhibit a host of phenotypes including growth retardation, facial dysmorphology, central nervous system anomalies, abnormal behavior and cognitive deficits. Previous research suggests that abnormal gene expression and circuitry in the neocortex may underlie reported disabilities of learning, memory, and behavior resulting from early exposure to alcohol (El Shawa et al., 2013).

Methods

Here, we utilize a mouse model of FASD to examine effects of prenatal ethanol exposure, or PrEE, on brain anatomy in newborn (P0), weanling (P20) and early adult (P50) mice. We correlate abnormal cortical and subcortical anatomy with atypical behavior in adult P50 PrEE mice. In this model, experimental dams self-administered a 25% ethanol solution throughout gestation (gestational day, GD, 0 to 19, day of birth), generating the exposure to the offspring.

Results

Results from these experiments reveal long-term alterations to cortical anatomy, including atypical developmental cortical thinning, and abnormal subcortical development as a result of in utero ethanol exposure. Furthermore, offspring exposed to ethanol during the prenatal period performed poorly on behavioral tasks measuring sensorimotor integration and anxiety.

Conclusions

Insight from this study will help provide new information on developmental trajectories of prenatal ethanol exposure and the biological etiologies of abnormal behavior in people diagnosed with FASD.

Keywords: prenatal alcohol exposure, brain development, neocortex, FASD, anatomy

Introduction

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) describe a continuum of deleterious effects on offspring from in utero ethanol exposure. Individuals with FASD often exhibit neurological, craniofacial, skeletal, cardiovascular and cognitive-behavioral deficits (Clarren et al., 1978; Murawski et al., 2015). Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, or FAS, represents the most severe form of FASD where the child is physically, cognitively and/or behaviorally impaired from prenatal ethanol exposure (PrEE). FAS epidemiological data show an incidence rate of 0.5–2.0 cases per 1,000 births (May and Gossage, 2001). However, rates of the spectrum, where all levels of exposure-related deficits are included, are believed to be much higher, as 18.6% of U.S. pregnant women age 35–44 reported drinking during pregnancy (Tan et al., 2015). According to the World Health Organization, PrEE is the leading cause of preventable mental retardation in the Western world. Despite this, the biological mechanisms that lead to altered brain development in offspring prenatally exposed to ethanol are not fully understood. Identification of brain regions susceptible to the effects of in utero ethanol exposure in humans and animal models provide critical insight that can be applied to future diagnoses and treatments in people with FASD.

The Collaborative Initiative on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (CIFASD) has provided support for links between prenatal ethanol exposure and anatomical irregularities in the human brain. For example, PrEE-related reductions in brain volume have been identified using human brain imaging (Archibald et al., 2001; Norman et al., 2009; Lebel et al., 2011). MRI studies in humans have revealed abnormalities in corpus callosum, with high variability in structural form persisting into adulthood (Bookstein et al., 2002; 2007), reduced basal ganglia (Mattson et al., 1996) and left-right hippocampal asymmetry (Riikonen et al., 1999). The neocortex is differentially affected by PrEE (Riikonen et al., 1999; Archibald et al., 2001; Sowell et al., 2002) with cortical thinning reported in middle-frontal, inferior-occipital and paracingulate areas (Zhou et al., 2011), and thickening reported in inferior-parietal, anterior-frontal and orbital-frontal cortex of subjects exposed ethanol during gestation (Sowell, et al. 2002a; Sowell et al., 2002b; Yang et al., 2011). Abnormal hippocampal and cortical information processing may largely underlie reported disabilities of learning, memory, and behavior as result of early exposure to alcohol (Streissguth et al., 1994; Granato et. al., 2006, El Shawa et al., 2013).

Many experimental studies in animal models have also demonstrated the risk of maternal ethanol consumption during pregnancy. Drinking while pregnant significantly impacts the offspring’s brain development, with the cerebral cortex being one of the key structures damaged by ethanol’s teratogenicity. PrEE leads to varying levels of cortical dysfunction, including defects in neuronal migration, changes in apoptosis or cell death, alterations in cortical thickness, callosal connectivity and selective reduction of GABA neurons (Miller 1993; Sampson et al., 1994; Ikonomidou et al., 2000; O’leary-Moore et al., 2011; Cao et al., 2014; Smiley et al., 2015). Furthermore, in our CD-1 mouse model of FASD, PrEE generated ectopic neocortical gene expression and disrupted targeting of intraneocortical connections (El Shawa et al., 2013). These atypical features of brain development were correlated with behavioral deficits around weaning. Other studies have identified non-cortical damage to the developing nervous system from PrEE. For example, West and colleagues described abnormal development in the hippocampus, cerebellum and corpus callosum following prenatal ethanol exposure in a rat model of FASD (Maier and West, 2001; Livy et al., 2003; Livy and Elberger, 2008).

In this study, we measure cortical thickness, cortical and subcortical structures in PrEE and control mice at three developmental timepoints in a novel mouse model of FASD: postnatal day (P)0 (newborn), P20 (weanling) and P50 (young adult). We predicted that moderate PrEE in the developing CD-1 mouse would result in abnormal region-specific neocortical thickness as well as altered cortical and sub-cortical structural development. Furthermore, we speculated that these PrEE-induced brain defects would persist across development, from birth to early adulthood. By assessing multiple locations throughout the brain at different stages of development we were able to map transient and persistent changes in the neuroanatomy of mice exposed to ethanol in utero.

Methods

Animal care

All experimental procedures conducted were approved by the University of California, Riverside Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Ten-week-old Female CD-1 mice were bred with non-sibling males, and housed alone during the entire gestational period following confirmation of a vaginal plug (gestational day, GD, 0.5). Dams were weight-matched, separated into ethanol-treated and control groups, and provided ad libitum access to standard mouse chow. A series of dam measures were taken to validate the exposure model; detailed methods for the measures are located in Supplemental Information. Upon birth, post-natal day (P) 0 male mice were weight-matched, euthanized (described in Supplemental Information) or cross-fostered with ethanol-naïve dams until age P20. P20 male weanlings were weight-matched, euthanized or weaned and raised to P50, when they were euthanized after behavioral testing.

Ethanol Administration

Ethanol administration in the CD-1 model was carried out as described previously (El Shawa et al., 2013). Dams received either 25% EtOH in water (experimental), or an isocaloric maltodextrin solution (control). Both solutions were available ad libitum alongside standard mouse chow for the entirety of gestation.

Tissue Processing

After euthanasia and perfusion, brains were collected and weighed at three ages (P0, P20, after behavioral experiments at P50) and cryoprotected in a sucrose solution for 1–3 days. Tissue was cryosectioned at 30µM in the coronal plane, mounted onto glass slides, stained for Nissl and imaged using a Zeiss Microscope and Zeiss Axiocamera.

Anatomical Measures

Gross dorsal views of P0, P20 and P50 control and PrEE brains were imaged using Zeiss microscopy. Regions of interest (ROI) in individual tissue sections were measured across all cases using an electronic micrometer in ImageJ by a trained researcher blind to the treatment. Cortical thickness measures in sections stained for Nissl substance were taken along a line perpendicular to the cortical sheet extending between the most superficial portion of layer I to the deepest portion of layer VI. These included prelimbic cortex (PL), frontal cortex (FC), primary auditory cortex (A1), primary somatosensory cortex (S1) and primary visual cortex (V1). ROIs were identified with the Paxinos atlas using specific cortical and subcortical landmarks such as the genu of the corpus callosum, the anterior commissure, the fimbria of hippocampus and the superior colliculus. Corpus callosum (CC) thickness was measured from the midline region. Measures of hippocampal subfield thickness were taken in CA3. Measures of basal ganglia (BG) were limited to caudate putamen, globus pallidus, and ventral palladium. Boundaries for dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) measures were taken using specific anatomical landmarks surrounding the dLGN, including: the intergeniculate leaf (IGL) for the ventral lateral border, the external medullary lamina (EM) for the ventral medial border, the lateral posterior nucleus (LP) for the dorsal border, and the brachium of the superior colliculus (BSC) for the dorsal lateral border of the dLGN. Basal Ganglia and dLGN volumes were calculated by drawing borders around the BG and dLGN in serial sections at a fixed magnification using ImageJ. Cell packing density within these ROIs was measured; these methods are located in Supplemental Information. Cortical thickness measures were as follows: P0 PrEE n = 15 and P0 Control n = 15; P20 PrEE n = 12 and P20 Control n = 12; P50 PrEE n = 12 and P50 Control n = 15. Subcortical measures were as follows: P0 PrEE n = 8 and P0 Control n = 8; P20 PrEE n = 8 and P20 Control n = 8; P50 PrEE n = 8 and Control n = 8). See Table 1 for a list of abbreviations.

Table 1.

| Abbreviation | Structure |

|---|---|

| A1 | Primary auditory cortex |

| BG | Basal ganglia |

| CA3 | Cornu ammonis region 3, hippocampus |

| CC | Corpus callosum |

| dLGN | Dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus |

| FAS | Fetal alcohol syndrome |

| FASD | Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders |

| FC | Frontal cortex |

| P | Postnatal day |

| PL | Prelimbic cortex |

| PrEE | Prenatal ethanol exposure |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| S1 | Primary somatosensory cortex |

| V1 | Primary visual cortex |

Behavioral assays

The effects of PrEE on sensorimotor integration, balance and anxiety-like behaviors were measured at P50 using two behavioral assays: the Suok test and the platform test. These tests have been used previously in this PrEE mouse model (El Shawa et al., 2013); methods for these behavioral assays are located in Supplemental Information.

Statistical Analyses

A 2×3 ANOVA with Holm-Šídák post hoc analysis was used to establish significant differences between body and brain weight, cortical thickness and volume differences of PrEE and control mice. To achieve homogenous variation data were log (base 10) transformed before analysis. Student’s t-test was used to analyze dam measures and offspring behavior. For data displayed as percent change, mean baseline corrected control was set as 100%, with experimental measures expressed as percentage variation from that mean.

Results

Dam measures

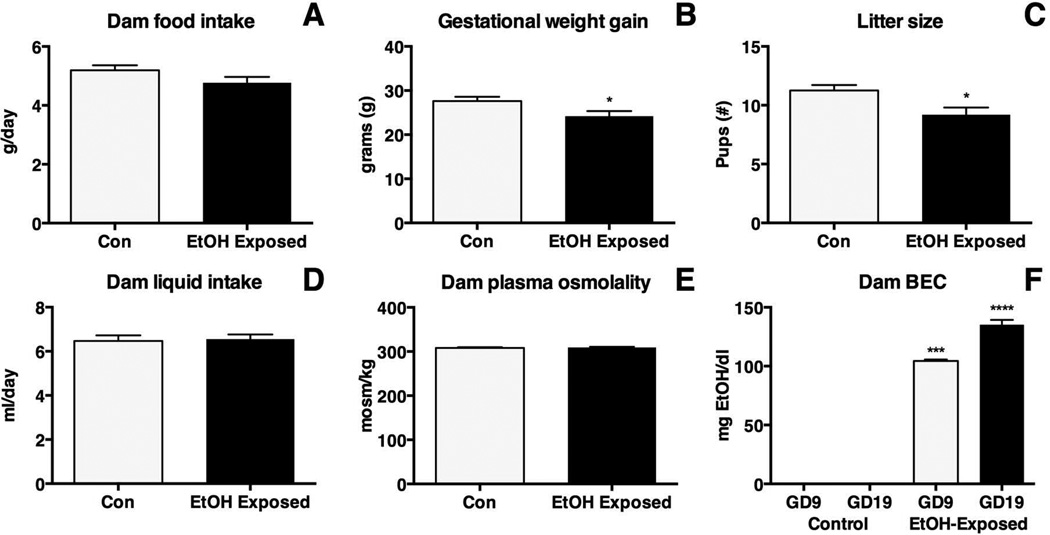

Multiple dam measures were recorded to verify effects generated by our ethanol exposure paradigm (Figure 1). To ensure our exposure paradigm did not cause malnutrition or dehydration measures of blood plasma osmolality, food intake, liquid intake and dam weight were taken. No significant variation was detected in daily food consumption (Figure 1A; control 5.19 ± 0.17 g/day; EtOH-exposed 4.78 ± 0.20 g/day; p = 0.16), though a significant reduction in weight gain over the entirety of gestation was observed (Figure 1B; control 27.63 ± 0.96 g; EtOH-exposed 24.18 ± 1.17 g; p<0.05). The reduced weight gain correlated with reduced litter size in EtOH-exposed dams (Figure 1C; control 11.25 ± 0.47 pups; EtOH-exposed 9.20 ± 0.60 pups; p<0.05). Liquid intake (Figure 1D; control 6.48 ± 0.25 ml/day; EtOH-exposed 6.55 ± 0.20 ml/day; p = 0.81) and measures of blood plasma osmolality revealed no significant variance in hydration between treatments (Figure 1E; control 308.2 ± 1.77 mosm/kg; EtOH-exposed 309.2 ± 1.65 mosm/k; p = 0.68)

Figure 1. Measurements in ethanol (EtOH)-exposed and control dams.

A, No significant differences were detected in average dam food intake. (EtOH-exposed, N=24; control, N=26). B, EtOH-exposed dams (N=12) gained significantly less weight during gestation when compared with controls (N=14; * p< 0.05). C, Gestational exposure to EtOH resulted in significantly reduced litter size in experimental cases (N=11) when compared with controls (N=10; * p<0.05). D, No significant difference was detected in average dam liquid intake (EtOH-exposed, N=24; control, N=26). E, No significant difference was detected in average dam plasma osmolality (EtOH-exposed, N=15; control, N=15). F, EtOH-exposed dams (GD9 N=11, GD19 N=12) had elevated BEC levels compared to untreated controls (GD9 N=5, GD19 N=7; * **p<0.001, * ***p<0.0001).

Blood ethanol content was measured at two gestational timepoints: GD9 and GD19. EtOH-exposed dams had elevated BEC levels at both GD9 (Figure 1F; control 0.00 ± 0.0 mg EtOH/dl; EtOH-exposed 104.4 ± 1.21 mg EtOH/dl; p<0.001) and GD19 (Figure 1F; control 0.00 ± 0.0 mg EtOH/dl; EtOH-exposed 135.2 ± 4.12 mg EtOH/dl; p<0.0001) when compared to controls.

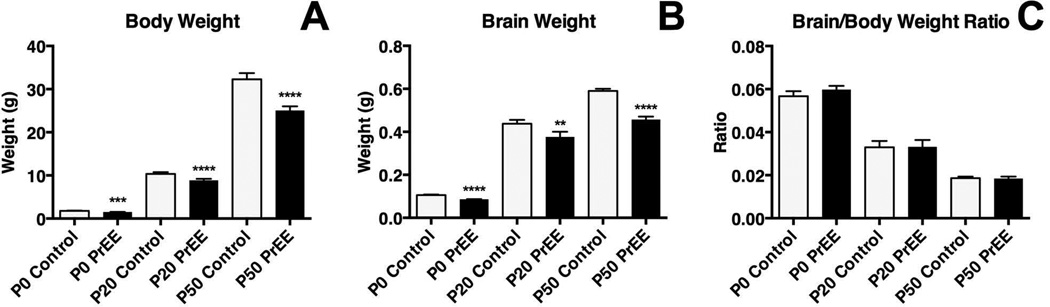

Body and brain weights of PrEE and control mice

Body weights were significantly reduced across both treatment [F(1, 101) = 53.32, p<0.0001] and age [F(2, 101) = 3230, p<0.0001]. Post hoc analysis indicated significant decreases in body weight across development in PrEE mice (Figure 2A: P0, control 1.794 ± 0.041 and PrEE 1.515 ± 0.029, p<0.001; P20, control 9.882 ± 0.428 and PrEE 7.953 ± 0.375, p<0.0001; P50, control 32.27 ± 1.446 and PrEE 25.04 ± 0.990, p<0.0001). Average daily growth rate from P0 to P20 was similar in control (9.35% per day) and PrEE animals (9.12% per day), while average growth rate from P20 to P50 was slightly accelerated in PrEE animals (4.01% per day) compared to controls (3.3% per day). Brain weight measurements of PrEE and control brains revealed significant effect across both treatment [F(1, 101) = 94.57, p<0.0001] and age [F(2, 101) = 3583, p<0.0001]. Post hoc analysis indicated that significant variation between control and PrEE mice was present at P0 (Figure 2B; control 0.104 ± 0.004 and PrEE 0.089 ± 0.001; p<0.0001), P20 (Figure 2B; control 0.438 ± 0.018 and PrEE 0.377 ± 0.024; p<0.01) and P50 (Figure 2B; control 0.590 ± 0.010 and PrEE 0.457 ± 0.014; p<0.0001). Average daily growth rate of whole brain from P0 to P20 and P20 to P50 was consistent in control and PrEE animals (P0-20: control = 7.7% per day, PrEE = 8.4% per day; P20-P50: control = 1.3% per day, PrEE = 0.07% per day). These changes occur without altering brain/body weight ratios at any age (Figure 2C: P0, control 0.057 ± 0.002 and PrEE 0.060 ± 0.002, p = 0.73; P20, control 0.033 ± 0.003 and PrEE 0.034 ± 0.003, p = 0.99; P50, control 0.019 ± 0.001 and PrEE 0.018 ± 0.001, p = 0.99). Consistent with body and brain weight reductions, visual assessment of brain size across conditions and ages revealed that PrEE mice are born with smaller brains than age-matched controls, which persists into early adulthood (dorsal view images of brains shown in Figure 3).

Figure 2. Body and brain weight measures.

A, Average body weight was significantly reduced in PrEE animals at all timepoints (P0, Control: n=20, PrEE: n=20, p<0.001; P20, Control: n=17, PrEE: n=17 p<0.0001; P50, Control: n=17, PrEE: n=17, p<0.0001). B, A significant reduction in average brain weight was observed in PrEE mice at all timepoints (P0, Control: n=20, PrEE: n=20, p<0.0001; P20, Control: n=17, PrEE: n=17, p<0.01; P50, Control: n=17, PrEE: n = 17, p<0.0001). C, Brain/body weight ratios were not significantly altered between treatments at any age.

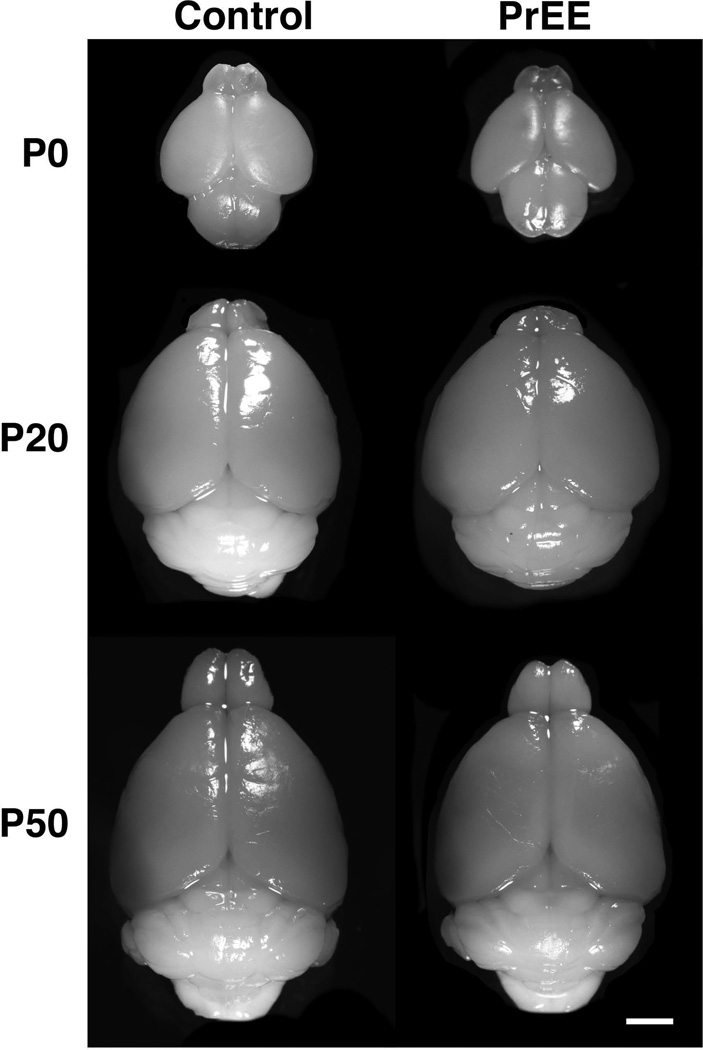

Figure 3. Brain size at P0, P20 and P50.

Dorsal images of control and PrEE mice brains. PrEE brains are reduced in size when compared to age-matched controls. Scale bar = 2 mm.

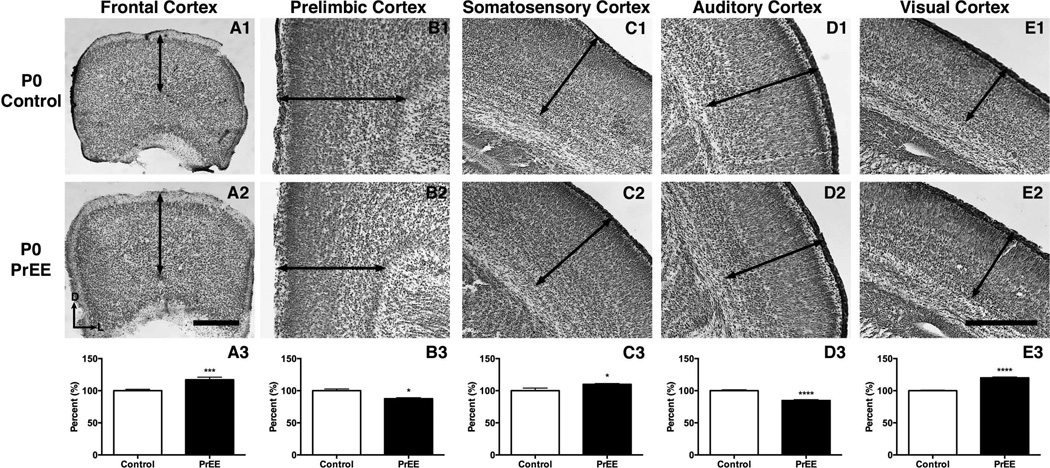

Cortical thickness in PrEE and control mice

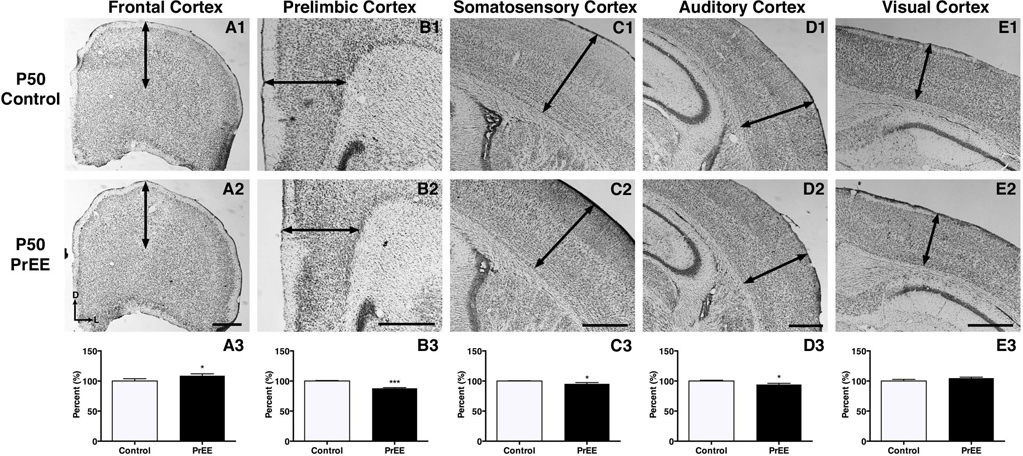

Frontal cortex

Significant thickening of frontal cortex was observed in PrEE mice across development [F(2, 78) = 288.4, p<0.0001]. Post hoc analysis at P0 (Figure 4A1-A3, control 100 ± 2.231 %, PrEE 117.1 ± 4.023 % p<0.001), P20 (Figure 5A1-A3, control 100 ± 3.305 %, PrEE 116.7 ± 2.254 %, p<0.01) and P50 (Figure 6A1-A3, control 100 ± 3.869 %, PrEE 108.8 ± 3.134 %, p<0.05) revealed significant variance between control and PrEE animals.

Figure 4. Cortical thickness measures in P0 PrEE and control mice.

Coronal sections in control (top row) and PrEE mice (middle row). Arrows indicate area of measure. A significant reduction was detected in prelimbic (B3; p<0.05) and auditory cortices (D3; p<0.0001). PrEE mice exhibited significantly thicker dorsal frontal (A3; p<0.001), somatosensory (C3; p<0.05) and visual cortices (E; p<0.0001). Data is expressed as mean percent of control ± S.E.M. Dorsal (D) up, lateral (L) to the right. Scale bars = 500 µM. Control: n=15, PrEE: n=15.

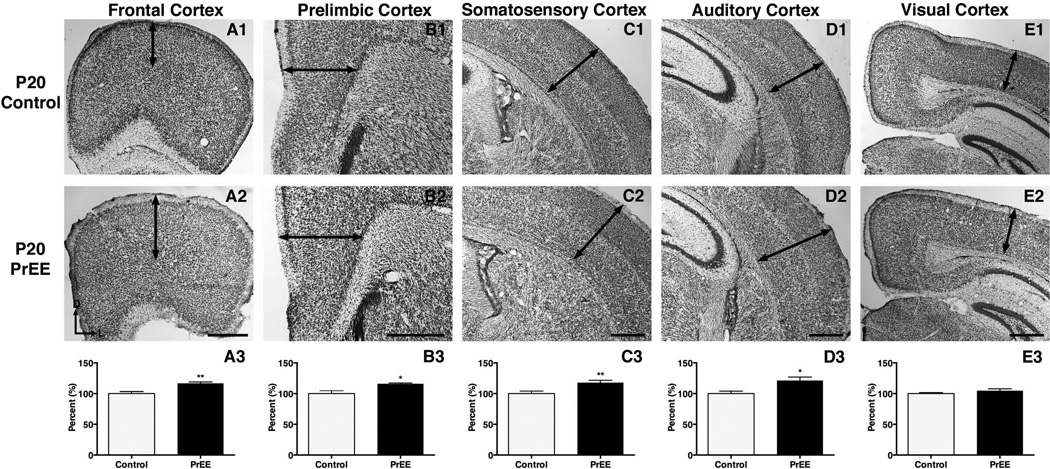

Figure 5. Cortical thickness measures in P20 PrEE and control mice.

Coronal sections of representative control (top row) and PrEE (middle row) tissue. Arrows indicate area of measure. PrEE mice exhibited significantly thicker frontal (A3; p<0.01), prelimbic (B3; p<0.05), somatosensory (C3; p<0.01) and auditory cortices (D3; p<0.05). No significant variation was detected in visual cortex of PrEE animals (E3; P = 0.19). Data is expressed as mean percent of control ± S.E.M. Dorsal (D) up, lateral (L) to the right. Scale bar = 500 µM. Control: n=12, PrEE: n=12.

Figure 6. Cortical thickness measures in P50 PrEE and control mice.

Coronal view of representative sections in P50 control (top row) and PrEE mice (middle row). Arrows indicate area of measure. Significant thinning of PrEE cortical tissue was found in prelimbic (B3; p<0.001), somatosensory (C3; P<0.05) and auditory cortices (D3; p<0.05). Significant variation was found in frontal (A3; p<0.05), but not visual cortices (E3; p = 0.13) of PrEE animals. Data is expressed as mean percent of baseline corrected control ± S.E.M. Dorsal (D) up, lateral (L) to the right. Scale bar = 500 µM. Control: n=12, PrEE: n=12

Prelimbic cortex

Experimental animals exhibited an inverted U-shape developmental trajectory in prelimbic cortex that varied significantly across age [F(2, 78) = 1575, p<0.0001]. Post hoc analysis revealed that PrEE induced significant thinning in PL at birth (Figure 4B1-B3, control 100 ± 2.711 %, PrEE 87.46 ± 1.424 %, p<0.05). By P20 significant thickening in the PL was found in PrEE mice (Figure 5B1-B3, control 100 ± 4.460%, PrEE 115.9 ± 1.301%, p<0.05), with the PL reverting to substantial thinning in experimental groups by P50 (Figure 6B1-B3, control 100 ± 0.8254 %, PrEE 87.80 ± 1.094, p<0.001).

Somatosensory cortex

PrEE inhibited early developmental cortical thinning in somatosensory cortex at both P0 (Figure 4C1-C3, control 100 ± 1.412 %; PrEE 109.9 ± 1.310 %, p<0.05), and P20 (Figure 5C1-C3, control 100 ± 4.091 %, PrEE 117.8 ± 3.692 %, p<0.01). The absence of developmental thinning of S1 early on was reversed by early adulthood with PrEE generating significant thinning at P50 (Figure 6C1-C3, control 100 ± 0.4849 %, PrEE 95.29 ± 2.144 %, p<0.05). An effect of PrEE was also detected across development [F(2, 78) = 902.1, p<0.0001].

Auditory cortex

Significant variance in auditory cortex was detected across treatment [F(1, 78) = 6.834, p<0.05] and age [F(2, 78) = 614.0, p<0.0001]. Post hoc analysis indicated significant thinning of auditory cortex in P0 PrEE brains, compared to P0 control (Figure 4D1-D3, control 100 ± 1.433 %, PrEE 84.74 ± 1.277 %, p<0.0001). At P20, however, PrEE induced significant thickening of auditory cortex (Figure 5D1-D3, control 100 ± 3.910 %, PrEE 121.4 ± 5.567 %, p<0.05). Significant changes persisted into early adulthood, with PrEE brains having significantly thinner A1 (Figure 6D1-D3, control 100 ± 1.260%, PrEE 91.18 ± 2.018%, p<0.05).

Visual cortex

Significant variance in visual cortex was detected across treatment [F(1, 78) = 36.20, p<0.05] and age [F(2, 78) = 3259, p<0.0001]. Visual cortex thickness was significantly increased in P0 PrEE brains (Figure 4E1-E3, control 100 ± 0.8511 %, PrEE 120.0 ± 1.305 %, p<0.0001), when compared to controls. No significant variance persisted into later developmental time points (Figure 5E1-E3, p = 0.21; Figure 6E1-E3, p = 0.21).

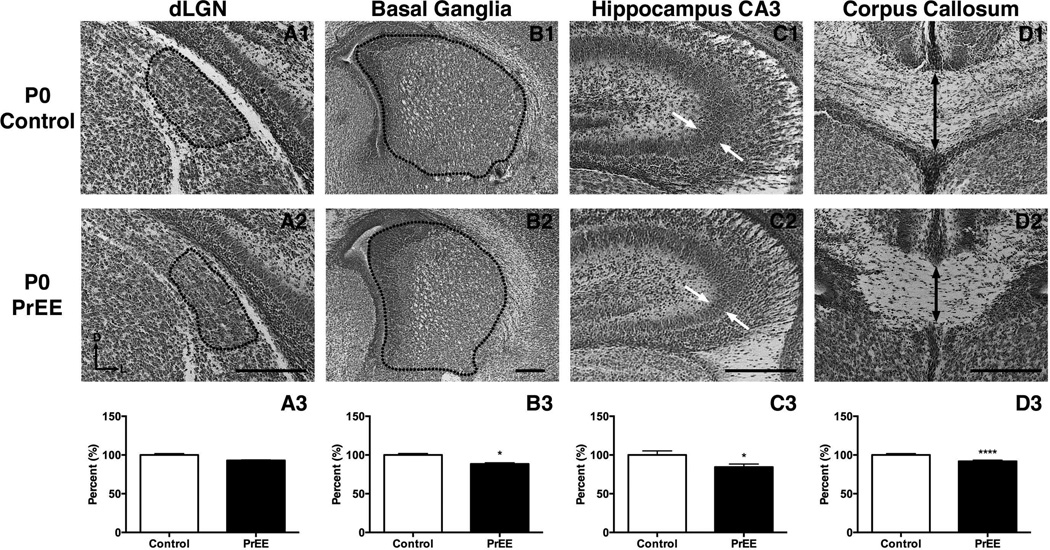

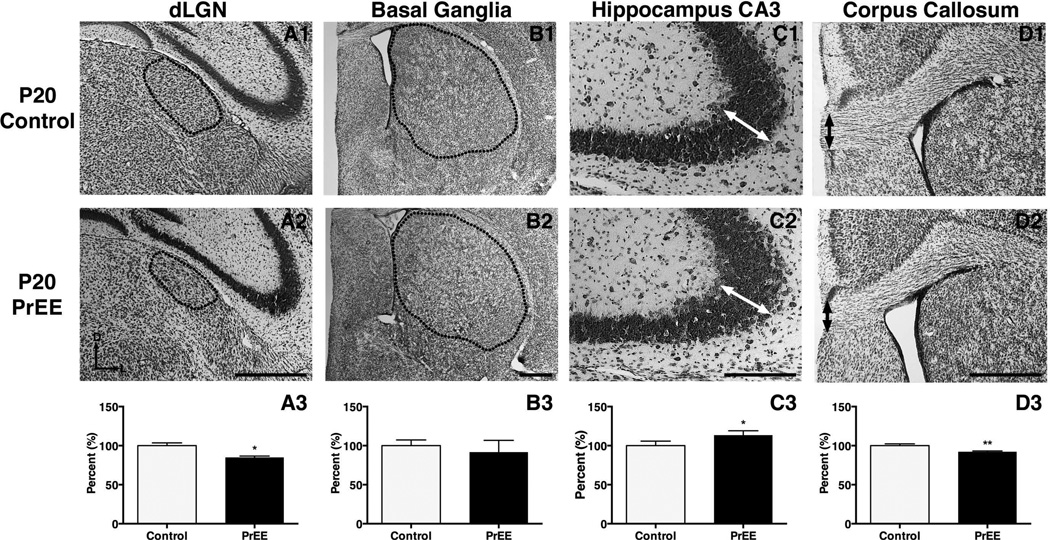

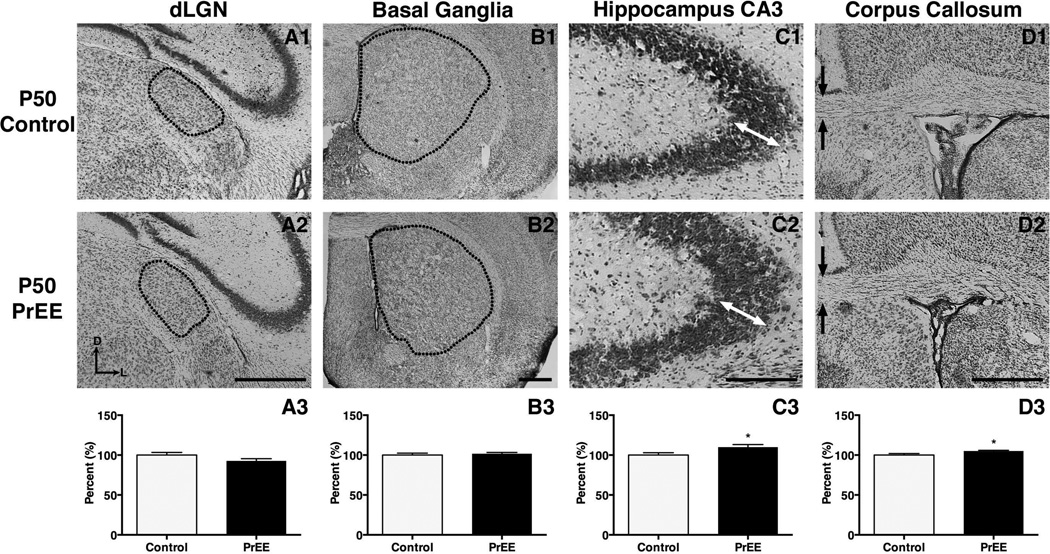

Dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus

Significant variance in dLGN was detected across treatment [F(1, 78) = 4.938, p<0.05] and age [F(2, 78) = 13.08, p<0.0001]. Post hoc analysis of dLGN size revealed no significant change in P0 PrEE mice (Figure 7A1-A3, control 100 ± 1.767 %, PrEE 92.99 ± 0.7395 %; p = 0.65). A reduction in size of dLGN was present at P20 in PrEE mice (Figure 8A1-A3, control 100 ± 3.567 %, PrEE 84.99 ± 1.673 %; p<0.05). Analysis of P50 PrEE and control dLGN revealed no differences in nuclear size (Figure 9A1-A3; p = 0.70).

Figure 7. Anatomical volume and thickness measures in P0 PrEE and control mice.

Representative coronal sections in control (top row) and PrEE mice (middle row). Outlines and arrows indicate area of measure. No significant difference was detected in dLGN (A3; p = 0.65). Significant reductions were detected across all other regions investigated:, basal ganglia (B3; p<0.05), CA3 pyramidal layer thickness (C3; p<0.05) and corpus callosum (D3; p<0.0001). Data is expressed as mean percent of baseline corrected control ± S.E.M. Dorsal (D) up, lateral (L) to the right. Scale bars = 500 µM. Control: n=8, PrEE: n=8

Figure 8. Anatomical volume and thickness measures in P20 PrEE and control mice.

Representative coronal sections in control (top row) and PrEE mice (middle row). Outlines and arrows indicate area of measure. Significant reductions were detected in dLGN (A3; p<0.05) and corpus callosum (D3; p<0.01). CA3 pyramidal layer thickness was significantly increased in PrEE animals (C3; p<0.05). PrEE basal ganglia (B3; p = 0.11) did not differ significantly from that of controls. Data is expressed as mean percent of baseline corrected control ± S.E.M. Dorsal (D) up, lateral (L) to the right. Scale bar = 500 µM. Control: n=8, PrEE: n=8.

Figure 9. Anatomical volume and thickness measures in P50 PrEE and control mice.

Representative coronal sections in P50 control (top row) and PrEE mice (middle row). Outlines and arrows indicate area of measure. No significant variance was detected in dLGN (A3; p = 0.09) or basal ganglia (B3; p = 0.54). Pyramidal layer thickness increased within CA3 of PrEE animals (C3; p<0.05). A significant increase of callosal thickness was detected at the midline of PrEE corpus callosum (D3; p<0.05). Data is expressed as mean percent control ± S.E.M. Dorsal (D) up, lateral (L) to the right. Scale bar = 500 µM. Control: n=8, PrEE: n=8.

Basal ganglia

The basal ganglia exhibited significant variance across treatment [F(1, 78) = 10.38, p<0.01] and age [F(2, 78) = 26.49, p<0.0001]. Post hoc analysis of newborn PrEE mice revealed reduced BG size (Figure 7B1-B3, control 100 ± 1.894 %, PrEE 88.38 ± 1.501 %; p<0.05). Further analyses of BG in weanling and early adult mice revealed no persistent variance between treatments (Figure 8B1-B3; p = 0.65; Figure 9B1-B3, p = 0.77).

Hippocampus

The CA3 region of the hippocampus varied significantly across development [F(2, 78) = 44.33, p<0.0001]. Post hoc analysis revealed significant thinning in P0 PrEE (Figure 7C1-C3, control 100 ± 5.353%, PrEE 84.38 ± 3.917 %, p<0.05) and P20 PrEE mice (Figure 8C1-C3, p<0.05). By early adulthood a significant thickening of CA3 was observed in PrEE brains, compared to controls (Figure 9C1-C3, control 100 ± 1.963 %, PrEE 108.1 ± 0.826 %, p<0.05).

Corpus Callosum

Significant differences in midline callosal thickness were observed between treatments [F(1, 78) = 16.32, p<0.001] across early development [F(2, 78) = 1135, p<0.0001]. Post hoc analysis indicated PrEE mice had a significantly thinner CC at P0 (Figure 7D1-D3, control 100 ± 1.844 %, PrEE 91.85 ± 1.430 %, p<0.0001), and P20 (Figure 8D1-D3, control 100 ± 2.347 %, PrEE 92.20 ± 1.049 %, p<0.01). However, CC thinning in P0 and P20 PrEE mice was no longer evident in young adult brains (P50). Instead, a statistically significant, dramatic increase in thickness was observed at P50 in PrEE mice as compared to controls (Figure 9D1-D3, p<0.05).

Cell packing density

To determine if altered cortical thickness observed in PrEE mice was generated by varied total cell number or degree of compaction, cell nuclei packing density was measured at P0, P20 and P50 (table 2). Regional cell packing density in cortex did not significantly differ at any of the developmental timepoints measured. Thus, the varied region-specific volumetric changes in cortical thickness are not simply caused by a change in cell packing density.

Table 2.

Cortical cell packing density in PrEE and control mice expressed in cells × 103/mm3 as mean ± s.e.m.

| PL | dFC | S1 | A1 | V1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Con | PrEE | Con | PrEE | Con | PrEE | Con | PrEE | Con | PrEE | |

| P0 | 101.4 ± 3.1 | 100.5 ± 1.9 | 102.6 ± 3.8 | 100.6 ± 2.7 | 115.5 ± 1.1 | 111.7 ± 1.4 | 104.7 ± 2.4 | 103.1 ± 2.0 | 121.0 ± 1.8 | 119.6 ± 2.3 |

| P20 | 87.8 ± 3.5 | 89.5 ± 0.9 | 89.8 ± 1.8 | 89.9 ± 2.7 | 94.0 ± 1.5 | 98.9 ± 3.2 | 91.1 ± 0.9 | 92.1 ± 3.0 | 95.3 ± 1.5 | 98.1 ± 3.8 |

| P50 | 89.0 ± 0.2 | 86.5 ± 2.2 | 83.5 ± 0.8 | 88.1 ± 2.2 | 86.0 ± 0.4 | 86.6 ± 0.2 | 86.3 ± 1.2 | 87.7 ± 0.6 | 90.4 ± 1.6 | 93.0 ± 1.5 |

Note: PL, prelimbic cortex; dFC, dorsal frontal cortex; S1, primary somatosensory cortex; A1, primary auditory cortex; V1, primary visual cortex.

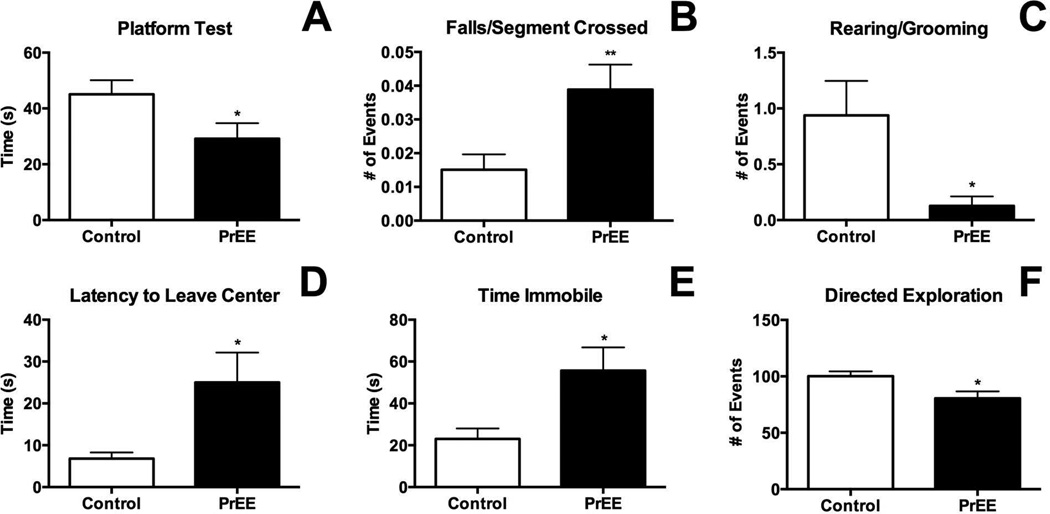

Behavioral analyses

Performance on the Suok and platform apparatus was recorded at P50, revealing increased anxiety and reduced balance and sensorimotor integration in PrEE mice compared to age-matched controls. Balance, as defined by performance on the platform test, was significantly different across treatments (Fig 10A, control 45.07 ± 5.056 s, PrEE 29.18 ± 5.538 s; p<0.05). Falls per segment crossed, a measure of sensorimotor integration, revealed a pronounced deficit in PrEE mice when compared to controls (Figure 10B, control 0.015 ± 0.005, PrEE 0.04 ± 0.007; p<0.01). Rearing and stereotyped cephalo-caudal grooming was reduced significantly in PrEE animals indicating increased anxiety (Figure 10C, control 0.9375 ± 0.309, PrEE 0.1250 ± 0.085; p<0.05). Additional anxiety-like behaviors were detected in measures on the Suok apparatus including an increased latency to leave the central portion of the apparatus (Figure 10D, control 6.817 ± 1.471 s, PrEE 25.03 ± 7.114 s; p<0.05), increased time spent immobile (Figure 10E, control 23.07 ± 4.947 s, PrEE 55.73 ± 11.04 s; p<0.05) and reduced directed exploration (Fig 10F, control 100.1 ± 4.352, PrEE 80.53 ± 6.187; p<0.05).

Figure 10. Behavioral measures in young adult mice.

In the platform test (A) PrEE mice exhibited a significant reduction in balance compared to control (p<0.05). In the Suok test PrEE animals fell significantly more for each segment crossed, a measure of sensorimotor integration (B; p<0.01). Anxiety-like behaviors including rearing/cephalo-caudal grooming (C), latency to leave central zone (D), time spent immobile (E) and directed exploration all indicated increased anxiety in PrEE mice (p<0.05). Control: n=16, PrEE: n=17.

Discussion

In this report we describe structural abnormalities in PrEE mice at postnatal days 0, 20 and 50, with behavioral analyses performed at P50. By detailing developmental changes in the neuroanatomy of PrEE mice, we gain a more complete understanding of ethanol’s impact on the trajectory of cortical thinning, nuclear size and structural features during development. Furthermore, measuring behavioral dysfunction in the same animals at P50 suggests that these changes may underlie some commonly observed cognitive and behavioral impairments observed in children with FASD.

Effects of PrEE on offspring body and brain weights

In this study, we found that newborn PrEE mice had decreased body and brain weights when compared to controls, although brain to body weight ratio remained unchanged following prenatal ethanol exposure, suggesting that we are non-selectively inhibiting CNS development. Neuronal loss in the cortex, coupled with reports of specific loss of cerebellar and hippocampal neurons, and decreased white matter in the brain as a result of ethanol exposure during development, could account for the overall loss of brain mass observed in children diagnosed with FASD (Bauer-Moffett and Altman, 1977; Goodlett et al., 1990; Ikonomidou et al., 2000). In addition to our PrEE mice displaying lower brain weights throughout development when compared to their control counterparts, ethanol exposed mice also had decreased body weights at birth, an effect that was maintained through early adulthood (P50). Decreased body weight across development in our mouse model is consistent with outcomes observed in humans and rodents exposed to ethanol via maternal consumption during pregnancy (Margret et al., 2005; Chappell et al., 2007; May et al., 2014). Interestingly, however, despite this effect average growth rates were marginally accelerated in weanling (P20) and young adult (P50) PrEE animals when compared to controls. This time period is considered a sensitive developmental time-period, as the body and brain undergo considerable maturation. Although a growth spurt may represent a form of recovery from P20-P50 in PrEE mice, weight increases outside of normal programmed growth rates may have long-term adverse consequences. Perhaps the offspring are compensating for low body weights by increasing caloric intake. This increased rate of weight gain when compared to controls may negatively impact programmed developmental mechanisms and cause unwanted consequences related to obesity later in life.

PrEE and cortical thickness

Prenatal ethanol exposure disrupts the normal cortical developmental trajectory, beginning with a significant thickening of FC, S1 and V1 and thinning of PL and A1 at P0. In control P20 mice, developmental cortical thinning is usually observed across cortical areas; however, in the PrEE mice, all cortical areas except V1 are thicker than controls, suggesting a delay in area maturation. By P50, PrEE PL, S1 and A1 exhibit distinct thinning, while FC shows thickening and V1 show no observable changes in thickness compared to controls. The observation of reduced developmental cortical thinning during a time related to ‘middle childhood’ in children and a maintained perturbation during early adulthood in our model is reminiscent of variation seen in humans with FASD. For example, these changes mark an alteration to an essential developmental process thought to be broadly driven by arealization, and in particular, the refinement of neuronal networks, white matter myelination and synaptic pruning (Sowell et al., 2004; Treit et al., 2014). The process of cortical thinning, beginning in early development and carrying through to adulthood, proceeds at varying rates dependent upon brain region, with frontal and prelimbic regions thinning at lower rates in humans (Tamnes et al., 2010). The persistence of thickened FC in PrEE mice throughout early development is stereotaxically consistent with dysregulated intraneocortical connections previously reported by our laboratory (El Shawa et al., 2013). The failure to prune these aberrant connections may be involved in delayed cortical thinning, with these alterations potentially underlying the impaired coordination and increased anxiety we observed in P50 PrEE mice. Further evidence demonstrating the dysfunctional impact of inhibited FC thinning can be found in human studies which have demonstrated that FC thickness during development is increased in individuals with both attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and FASD when compared to those suffering from FASD alone, a finding they attribute to immature brain development (Fernández-Jaén et al., 2011).

Prenatal ethanol exposure alters the development of sensory areas in the neocortex and thus impacts sensory processing. One area altered by PrEE is the V1 cortical retinotopic map, which is the recipient of projections from the dLGN. Studies show a lack of connectional and electrophysiological refinement in response to prenatal ethanol exposure in V1 (Lantz et al., 2014). Somatosensory and auditory information show similar multi-leveled processing deficits ranging from thalamic defects to altered cortical pyramidal cell morphology and function (Mooney et al., 2010; Church et al., 2012; De Giorgio and Granato, 2015). Taken together, these findings suggest that impaired higher-order cortical processing and integration of auditory, somatosensory and visual information may contribute to balance and motor control impairments in our mouse model of FASD.

Cortical thickness is influenced by a number of factors including cytoarchitecture, organization and overall cell number (Dunty et al., 2001; Miller, 1988). Analysis of cell packing density in the present study revealed no significant change amongst treatments. This suggests that the maintenance of cortical thickness in PrEE animals occurs independently of cell packing density of specific cortical populations. Instead, it is probable that these changes occur at least partially through a comprehensive change in cell number, possibly generated via up/down regulation of migration or proliferation pathways, which maintain cortical cell packing density despite altered cortical thickness.

Extra-Neocortical brain structures altered by PrEE

Commensurate with PrEE induced changes in brain size and cortical thickness, widespread extra-neocortical abnormalities have been detected in both mice exposed to ethanol during gestation and children with FASD, with neuroimaging studies revealing the largest variation residing in BG, CA3 regions of the hippocampus and the CC (Derauf et al., 2009; Norman et al., 2009; Godin et al., 2011). As such, these regions, along with the dLGN, were investigated from birth to early adulthood.

dLGN

Our data demonstrate a reduction in the size of dLGN in P20 PrEE mice when compared to controls; however, this effect is not present at either P0 or P50. We believe the observed change is two-fold: reduction of the dLGN in the PrEE animals may result from altered expression of ephrin A5 in the nucleus, as its development is linked to the expression (Dye et al., 2012). We also suggest that PrEE, in addition to disrupting other developmental programs, induces a developmental delay.

Basal Ganglia

We initially observed decreased volume of the PrEE BG at P0, with recovery by P20, which persisted into early adulthood. While measures of BG volume typically reveal an overall reduction, these changes are commonly measured only during early postnatal and adolescent periods (Mattson et al., 1996; Godin et al., 2011). Our data demonstrates an increase in both anxiety-like behavior and deficits in motor function in PrEE mice at P50, behaviors associated with BG function, without persistent anatomical variation of BG size across PrEE and control mice at this age. Perturbations in early development may be sufficient for the generation of long-lasting behavioral consequences, even in the absence of persistent anatomical change.

Hippocampus

Clinical investigations have established a distinct association between gestational ethanol consumption and learning and memory deficits in exposed offspring (Willford et al., 2004). Owing to this vulnerability even moderate levels of ethanol exposure during development are sufficient to reduce hippocampal CA1 and CA3 pyramidal cell number, and alter dendritic morphology. Furthermore, timing of exposure has been demonstrated to play a role in both the persistence, and magnitude of effect (Maier and West, 2001; Livy et al., 2003). In the present report, measurement of the CA3 region of hippocampus revealed an initial reduction in CA3 thickness at birth in PrEE mice. However, by weaning and persisting to early adulthood, a significant thickening was observed in PrEE mice compared to controls. It is likely that the early reduction detected at P0 results from a combination of factors including reduced neurogenesis, synaptogenesis and decreased cell and spine density (Tarelo-Acuna et al., 2000; Livy et al., 2003; Cullen et al., 2014). Later recovery, and thickening observed in CA3 suggests the possibility of a preliminary period of a reversible neurodegenerative process, such as cell swelling due to the acute toxic effect of ethanol, which could become exacerbated following cessation of ethanol administration to the dams (Paula-Barbosa et al., 1993).

Corpus Callosum

Midline callosal hypoplasia was detected in both P0 and P20 PrEE mice, consistent with previous studies in both human and mouse that demonstrate an association between prenatal ethanol exposure and shape abnormalities with volumetric changes in the CC (Livy and Elberger, 2008; Gautam et al., 2014). Our results show an initial thinning of the CC at birth, lasting through P20, due to PrEE. However, by P50, we observe a recovery of the phenotype that led to increased thickness of the CC in early adulthood. These results have been observed in humans with FASD, and may be associated with deficits in executive function (Bookstein et al., 2002).

PrEE impacts behavior in Early Adulthood

Sensory/motor cortical and extra-neocortical development is disrupted by PrEE with effects on behavior lasting into early adulthood. These results corroborate similar findings reported previously in P20 PrEE mice (El Shawa et al., 2013). Furthermore, our results are consistent with cognitive and behavioral deficits described in children with FASD (Vernescu et al., 2012; Jirikowic et al., 2013).

Some anatomical measures show recovery of PrEE-related phenotypes by adulthood at P50 in our model (for example, the BG, dLGN, V1) without rescue of behavioral effects. We suggest that ectopic connectivity, as shown in our previous report (El Shawa et al., 2013), persists into adulthood. Despite a recovery in volume of some structures, a persistence of abnormal connectivity could account for the maintenance of the behavioral phenotype.

In summary, we report alterations to developmental cortical thinning across functionally diverse regions of cortex, and altered development of extra-neocortical structures, with correlative behavioral deficits in early adulthood. The observed group of PrEE-induced alterations is consistent with documented human patterns of birth defects present at early developmental stages. By extending our findings into childhood and early adulthood, we identify possible markers, which if investigated using non-invasive methods, such as MRI, could prove informative for clinical diagnosis of individuals with FASD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Hani El Shawa for his role in the early development of the mouse model.

Support: NIAAA 1R03AA021545-01 to K.J.H.

References

- Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, Gamst A, Riley EP, Mattson SN, Jernigan TL. Brain dysmorphology in individuals with severe prenatal alcohol exposure. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:148–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer-Moffett C, Altman J. The effect of ethanol chronically administered to preweanling rats on cerebellar development: A morphological study. Brain Res. 1977;119(2):249–268. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90310-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein FL, Connor PD, Huggins JE, Barr HM, Pimentel KD, Streissguth AP. Many infants prenatally exposed to high levels of alcohol show one particular anomaly of the corpus callosum. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:868–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein FL, Sampson PD, Connor PD, Streissguth AP. Midline corpus callosum is a neuroanatomical focus of fetal alcohol damage. Anat Rec Part B New Anat. 2002;269:162–174. doi: 10.1002/ar.10110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Li W, Han H, O’Leary-Moore SK, Sulik KK, Allan Johnson G, Liu C. Prenatal alcohol exposure reduces magnetic susceptibility contrast and anisotropy in the white matter of mouse brains. Neuroimage. 2014;102:748–755. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell TD, Margret CP, Li CX, Waters RS. Long-term effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the size of the whisker representation in juvenile and adult rat barrel cortex. Alcohol. 2007;41:239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church MW, Hotra JW, Holmes PA, Anumba JI, Jackson DA, Adams BR. Auditory brainstem response (ABR) abnormalities across the life span of rats prenatally exposed to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen CL, Burne THJ, Lavidis NA, Moritz KM. Low dose prenatal alcohol exposure does not impair spatial learning and memory in two tests in adult and aged rats. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e101482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derauf C, Kekatpure M, Neyzi N, Lester B, Kosofsky B. Neuroimaging of children following prenatal drug exposure. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:441–454. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Giorgio A, Granato A. Reduced density of dendritic spines in pyramidal neurons of rats exposed to alcohol during early postnatal life. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2015;41:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunty WCJ, Chen S, Zucker RM, Dehart DB, Sulik KK. Selective vulnerability of embryonic cell populations to ethanol-induced apoptosis: implications for alcohol-related birth defects and neurodevelopmental dis-order. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1523–1535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye CA, Abbott CW, Huffman KJ. Bilateral enucleation alters gene expression and intraneocortical connections in the mouse. Neural Dev. 2012;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Shawa H, Abbott CW, Huffman KJ. Prenatal ethanol exposure disrupts intraneocortical circuitry, cortical gene expression, and behavior in a mouse model of FASD. J Neurosci. 2013;33:18893–18905. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3721-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Jaén A, Fernández-Mayoralas DM, Quiñones Tapia D, Calleja-Pérez B, García-Segura JM, Arribas SL, Muñoz Jareño N. Cortical thickness in fetal alcohol syndrome and attention deficit disorder. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;45:387–391. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam P, Nuñez SC, Narr KL, Kan EC, Sowell ER. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the development of white matter volume and change in executive function. Neuroimage Clin 4. 2014;5:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin EA, Dehart DB, Parnell SE, O'Leary-Moore SK, Sulik KK. Ventromedian forebrain dysgenesis follows early prenatal ethanol exposure in mice. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2011;33:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlett CR, Marcussen BL, West JR. A single day of alcohol exposure during the brain growth spurt induces brain weight restriction and cerebellar Purkinje cell loss. Alcohol. 1990;7:107–114. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(90)90070-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidou C, Bittigau P, Ishimaru MJ, Wozniak DF, Koch C, Genz K, Price MT, Stefovska V, Horster F, Tenkova T, Dikranian K, Olney JW. Ethanol-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration and fetal alcohol syndrome. Science. 2000;287:1056–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirikowic TL, McCoy SW, Lubetzky-Vilnai A, Price R, Ciol MA, Kartin D, Hsu LY, Gendler B, Astley SJ. Sensory control of balance: a comparison of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders to children with typical development. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2013;20:e212–e228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz CL, Pulimood NS, Rodrigues-Junior WS, Chen CK, Manhaes AC, Kalatsky VA, Medina AE. Visual defects in a mouse model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:107. doi: 10.3389/fped.2014.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel C, Roussotte F, Sowell ER. Imaging the impact of prenatal alcohol exposure on the structure of the developing human brain. Neuropsyhcol Rev. 2011;21:102–118. doi: 10.1007/s11065-011-9163-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigland LA, Ford MM, Lerch JP, Kroenke CD. The influence of fetal ethanol exposure on subsequent development of the cerebral cortex as revealed by magnetic resonance imaging. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(6):924–932. doi: 10.1111/acer.12051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livy DJ, Elberger AJ. Alcohol exposure during the first two trimesters-equivalent alters the development of corpus callosum projection neurons in the rat. Alcohol. 2008;42:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livy DJ, Miller EK, Maier SE, West JR. Fetal alcohol exposure and temporal vulnerability: effects of binge-like alcohol exposure on the developing rat hippocampus. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2003;25:447–458. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(03)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SE, West JR. Regional differences in cell loss associated with bing-like alcohol exposure during the first two trimesters equivalent in the rat. Alcohol. 2001;23:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margret CP, Li CX, Elberger AJ, Matta SG, Chappell TD, Waters RS. Prenatal alcohol exposure alters the size, but not the pattern, of the whisker representation in neonatal rat barrel cortex. Exp Brain Res. 2005;165:167–178. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-2287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP. Estimating the prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome. A summary. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:159–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Hamrick KJ, Corbin KD, Hasken JM, Marais AS, Brooke LE, Blankenship J, Hoyme HE, Gossage JP. Dietary intake, nutrition, and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;46:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Effect of prenatal exposure to ethanol on the development of cerebral cortex: I. Neuronal generation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1988;12:440–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Migration of cortical neurons is altered by gestational exposure to ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:304–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney SM, Miller MW. Prenatal exposure to ethanol affects postnatal neurogenesis in thalamus. Exp Neurol. 2010;223:566–573. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murawski NJ, Moore EM, Thomas JD, Riley EP. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: from animal models to human studies. Alcohol Res. 2015;37:97–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman AL, Crocker N, Mattson SN, Riley EP. Neuroimaging and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15:209–217. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez CC, Roussotte F, Sowell ER. Focus on: structural and functional brain abnormalities in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34:121–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary-Moore SK, Parnell SE, Lipinski RJ, Sulik KK. Magnetic resonance-based imaging in animal models of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Neuropsychol Rev. 2011;21(2):167–185. doi: 10.1007/s11065-011-9164-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paula-Barbosa MM, Brandaõ F, Madeira MD, Cadete-Leite A. Structural changes in the hippocampal formation after long-term alcohol consumption and withdrawal in the rat. Addiction. 1993;88:237–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riikonen RS, Salonen I, Partanen K, Verho S. Brain perfusion SPECT and MRI in fetal alcohol syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41:652–659. doi: 10.1017/s0012162299001358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson PD, Bookstein FL, Barr HM, Streissguth AP. Prenatal alcohol exposure, birth weight, and measures of child size from birth to age 14 years. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1421–1428. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.9.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiley JF, Saito M, Bleiwas C, Masiello K, Ardekani B, Guilfoyle DN, Gerum S, Wilson DA, Vadasz C. Selective reduction of cerebral cortex GABA neurons in a late gestation model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Alcohol. 2015;49:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Mattson SN, Tessner KD, Jernigan TL, Riley EP, Toga AW. Regional brain shape abnormalities persist into adolescence after heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Cereb Cortex. 2002a;12:856–865. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Peterson BS, Mattson SN, Welcome SE, Henkenius AL, Riley EP, Jernigan TL, Toga AW. Mapping cortical gray matter asymmetry patterns in adolescents with heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Neuroimage. 2002b;17:1807–1819. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Leonard CM, Welcome SE, Kan E, Toga AW. Longitudinal mapping of cortical thickness and brain growth in normal children. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8223–8231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1798-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Barr HM, Sampson PD, Bookstein FL. Prenatal alcohol and offspring development: The first fourteen years. Drug and Alc Depen. 1994;36:89–99. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamnes CK, Ostby Y, Fjell AM, Westlye LT, Due-Tonnessen P, Walhovd KB. Brain maturation in adolescence and young adulthood: Regional age-related changes in cortical thickness and white matter volume and microstructure. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:534–548. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan CH, Denny CH, Cheal NE, Sniezek JE, Kanny D. Alcohol use and binge drinking among women of childbearing age-United States 2011–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report from CDC. 2015;64(37):1042–1046. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6437a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarelo-Acuna L, Olvera-Cortes ME, Gonzalez-Burgos I. Prenatal and postnatal exposure to ethanol induces changes in the shape of the dendritic spines from hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons of the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 2000;286:13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treit S, Zhou D, Lebel C, Rasmussen C, Andrew G, Beaulieu C. Longitudinal MRI reveals impaired cortical thinning in children and adolescents prenatally exposed to alcohol. Hum Brain Map. 2014;35:4892–4903. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernescu RM, Adams RJ, Courage ML. Children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder show an amblyopia-like pattern of vision deficit. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54:557–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willford JA, Richardson GA, Leech SL, Day N. Verbal and visuospatial learning and memory function in children with moderate prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:497–507. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000117868.97486.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Roussotte F, Kan E, Sulik KK, Mattson SN, Riley EP, Jones KL, Adnams CM, May PA, O'Connor MJ, Narr KL, Sowell ER. Abnormal cortical thickness alterations in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders and their relationships with facial dysmorphology. Cereb Cortex. 2011;22:1170–1179. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Lebel C, Lepage C, Rasmussen C, Evans A, Wyper K, Pei J, Andrew G, Massey A, Massey D, Beaulieu C. Developmental cortical thinning in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Neuroimage. 2011;58:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.