ABSTRACT

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is an alphavirus responsible for causing epidemic outbreaks of polyarthralgia in humans. Because CHIKV is initially introduced via the skin, where γδ T cells are prevalent, we evaluated the response of these cells to CHIKV infection. CHIKV infection led to a significant increase in γδ T cells in the infected foot and draining lymph node that was associated with the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in C57BL/6J mice. γδ T cell−/− mice demonstrated exacerbated CHIKV disease characterized by less weight gain and greater foot swelling than occurred in wild-type mice, as well as a transient increase in monocytes and altered cytokine/chemokine expression in the foot. Histologically, γδ T cell−/− mice had increased inflammation-mediated oxidative damage in the ipsilateral foot and ankle joint compared to wild-type mice which was independent of differences in CHIKV replication. These results suggest that γδ T cells play a protective role in limiting the CHIKV-induced inflammatory response and subsequent tissue and joint damage.

IMPORTANCE Recent epidemics, including the 2004 to 2007 outbreak and the spread of CHIKV to naive populations in the Caribbean and Central and South America with resultant cases imported into the United States, have highlighted the capacity of CHIKV to cause explosive epidemics where the virus can spread to millions of people and rapidly move into new areas. These studies identified γδ T cells as important to both recruitment of key inflammatory cell populations and dampening the tissue injury due to oxidative stress. Given the importance of these cells in the early response to CHIKV, this information may inform the development of CHIKV vaccines and therapeutics.

INTRODUCTION

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a mosquito-transmitted alphavirus belonging to the Togaviridae family and was first isolated in Tanzania in 1952 (1–3). It is responsible for epidemics of debilitating rheumatic disease associated with inflammation and destruction of musculoskeletal tissues in humans (4). Beginning in 2004, CHIKV reemerged, causing millions of infections in coastal Africa, islands of the Indian Ocean, and India (5–9). Infected visitors to these areas of CHIKV epidemics returned to Europe, Australia, the United Kingdom, Japan, Belgium, Canada, and the United States (10–15), and importation of human cases to northern Italy, New Caledonia, China, the French Riviera, and Saudi Arabia produced autochthonous outbreaks resulting from infection of naive mosquito populations (16–20). In late 2013, the first local transmission of CHIKV in the Americas was identified in Caribbean countries and territories, indicating that mosquito populations in these areas had become infected with the virus and are competent to transmit it to humans (21–23). Since that time, a total of approximately 1.2 million suspected and over 24,000 confirmed cases of CHIKV have been reported in 44 countries or territories in the Caribbean or South America (24), including hundreds of travelers returning to the United States, with subsequent localized transmission in Florida in 2014.

Analysis of the explosive 2004–2007 epidemic suggests that new disease manifestations may be associated with CHIKV that increase cause for concern. During the epidemic, CHIKV infection resulted in increased morbidity as well as mortality in adults (25, 26). Additionally, greater numbers of CHIKV-infected persons developed the more severe forms of the disease, including neurological complications and fulminant hepatitis, while maternal-fetal transmission associated with neonatal encephalopathy was also reported (25, 27–30). Of particular concern with this outbreak was the threat of CHIKV introduction and spread into new regions, in part through successful adaptation of the virus, allowing it to infect not only the classical vector Aedes aegypti but also the widely distributed mosquito vector Aedes albopictus (5, 31–35).

Symmetrical polyarthritis is the hallmark of CHIKV infection and is responsible for the severe arthralgia and inflammation associated with infection (36, 37). In addition to rheumatic disease, CHIKV infection is also associated with fever, headache, rigors, photophobia, myalgia, and a petechial or maculopapular rash (38, 39). The acute phase of CHIKV infection typically lasts from days to several weeks; however, multiple studies have reported chronic fatigue and chronic joint pain for a significant time postinfection, with one study demonstrating persistent joint pain in roughly 79% of patients at 27.5 months postinfection, with 5% of those infected with CHIKV meeting a modified version of the American College of Rheumatology criteria for rheumatoid arthritis (14, 37, 40–45). In both human cases and mouse models, CHIKV-induced immunopathology is implicated as the primary mediator of damage and persistent pain (46–50). Support for the immune-mediated pathogenesis of CHIKV comes from the observation that inflammation continues well after viral replication has ceased (51). Additionally, high levels of proinflammatory cytokines are observed both in humans and in mouse models of CHIKV disease. Finally, the contributions of immune mediators to pathology in closely related alphavirus infections have been well described (52–57).

The bulk of the work examining CHIKV-induced pathology and viral clearance has been centered on the innate immune response following infection (58–60). In particular the type I interferon (IFN) pathway is critical for controlling viral replication and pathogenesis during the early stages of CHIKV infection, though this response does not completely ablate CHIKV replication or disease (61–66). With respect to adaptive immunity, B cells and antibodies are known to be important, as CHIKV RNA persists in the serum of B cell-deficient mice for greater than a year and passive transfer of CHIKV-immune serum to IFNAR−/− mice protects against lethal infection (67). In human acute CHIKV infection, CD8+ T cells predominate in the early stages of the disease, with CD4+ T cells mediating the adaptive response at later times postinfection (60). Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have been shown to infiltrate CHIKV-infected tissues in mouse models of infection (66, 68). CD4+ T cells were recently shown to contribute to pathogenesis during CHIKV infection in mice independent of changes in viral titer and IFN-γ production (69). CD4−/− mice had lower levels of anti-CHIKV antibody with reduced neutralizing activity, although this did not affect their ability to control CHIKV infection (67). Regulatory T cells are also important in the pathogenesis of CHIKV, as interleukin-2 (IL-2) antibody-mediated expansion of regulatory T cells results in inhibition of CHIKV-specific CD4+ effector cells and abolishes joint pathology in mice (70). While these studies provided evidence that T cells contribute to CHIKV protection and pathogenesis, characterization of the different types of T cells responsible and the mechanism by which these cells contribute to CHIKV infection requires further study.

Since arboviruses are delivered to the human host subcutaneously by feeding mosquitos, it stands to reason that resident skin immune cells would serve as an important first defense against these infections. Immune cell populations within the skin are comprised of a heterogeneous population, including numerous types of dendritic cells (DCs), monocytes, and lymphocytes, with γδ T cells being the most abundant resident T lymphocytes in the skin and mucosal surfaces (71). γδ T cells lack major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restriction such that they react to antigens without the need for conventional processing and have been shown to be key players in cytotoxicity, cytokine secretion, and enhancement of DC maturation and function (72, 73). Notably, increased inflammation and exaggerated tissue damage observed in γδ T cell-deficient mice infected with various pathogens identified a requirement for γδ T cells in the resolution of potentially damaging immune responses and prevention of immune-mediated damage (74–79). γδ T lymphocytes have been studied in several different arbovirus infections, where they have been shown to contribute to both the innate and adaptive immune response (80–84).

To determine if γδ T cells play a role in CHIKV infection, wild-type (wt) C57BL/6J mice and mice deficient for the γδ T cell receptor (γδ T−/−) were infected and monitored for disease severity, viral replication, and joint and tissue pathology. Our results indicated that in the absence of γδ T cells, monocytic inflammatory cells and inflammatory cytokines increase at the site of CHIKV infection, and disease signs and tissue damage are exacerbated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus.

The virus used in this study was produced from electroporation of baby hamster kidney (BHK-21) cells with in vitro-transcribed RNA (mMESSAGE mMACHINE SP6 transcription kit; Life Technologies) derived from plasmid pMH56.2, which is an infectious clone that carries the full-length genome of CHIKV isolate SL15649. pMH56.2 was produced by sequential ligation of commercially synthesized genome fragments (BioBasic) into a modified pSinRep5 plasmid (Invitrogen). Detailed sequences and cloning details are available from the authors upon request. The clinical isolate SL15649 has been previously described (68). All studies were performed in certified biological safety level 3 facilities in biological safety cabinets with protocols approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of Environment, Health and Safety and the Institutional Biosafety Committee.

Mice.

C57BL/6J and γδ T cell−/− mice on a C57BL/6J genetic background were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. All mice were bred in-house as homozygous knockouts. Twenty-four-day-old mice were inoculated in the left rear footpad with 100 PFU of CHIKV in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in a 10-μl volume. Control animals were inoculated with 10 μl of sterile PBS alone. Mice were weighed daily and monitored for clinical signs of disease, including swelling of the ipsilateral foot by using calipers. At indicated times postinfection, mice were sacrificed by isoflurane (Attane; Minrad, Inc.) overdose. Animal husbandry and experiments were performed in accordance with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines and approval.

Virus titers.

At various times postinfection, mice were sacrificed and perfused by intracardial injection with 1× PBS. Blood was collected prior to perfusion, removed to serum separator tubes, and centrifuged for 5 min at full speed to collect serum. Tissues were dissected, weighed, homogenized in PBS, and stored at −80°C. The amount of infectious CHIKV present was determined by standard plaque assay on Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81).

Histological analysis.

Mice were sacrificed and perfused by intracardial injection with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), pH 7.3. Hind limb tissues were embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm sections were prepared. Tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and tissue sections were evaluated for the extent and severity of inflammation and musculoskeletal tissue damage. Photomicrographs were obtained using an Olympus BX43 model microscope with CellSens software.

Immunohistochemistry.

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and affixed to positively charged glass slides. Slides were deparaffinized with a graded series of xylene and ethanol washes followed by microwaving for 20 min in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6) for antigen retrieval. Specimens were blocked in 10% donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and subsequently stained with antibody specific for nitrotyrosine (Millipore). Staining was detected with the use of biotinylated secondary antibodies followed by streptavidin–DyLight-594 conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Stained sections were mounted in ProLong Antifade Reagent Gold with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen) and viewed with an Olympus BX60 fluorescence microscope; images were collected with the iVision software v.4.0.0 (BioVision Technologies).

Flow cytometry.

Inoculated mice were sacrificed and perfused with 1× PBS. The skin was removed from the hind limbs and the leg was dissected just above the patella, ensuring that the bone marrow was not exposed. Following gentle separation of tissues from bone with a scalpel, the entire tissue sample was incubated for 1 h with vigorous shaking at 37°C in digestion buffer (RPMI 1640, 10% fetal bovine serum, 15 mM HEPES, 2.5 mg/ml collagenase A [Roche], 1.7 mg/ml DNase I [Sigma]). Following digestion, cells were passed through a 40-μm cell strainer and washed in wash buffer, and total viable cells were determined by trypan blue exclusion. Cells were stained in fluorescence-activated cell-sorting staining buffer (1× Hanks balanced salt solution, 1% fetal bovine serum, 0.01% sodium azide) with the following antibodies from eBioscience: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–F4/80, phycoerythrin cyanine (PE)-NK1.1, PE-Texas Red (PETR)–CD11c, peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP)-Ly6C, PE-cyanine 7 (Cy7)–lymphocyte common antigen (LCA), eF450-CD11b, allophycocyanin (APC)–MHC-IIc, APC-eF780–Ly6G, PE–γδ T cell receptor (TCR), PETR-CD4, and FITC-CD3. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight before being analyzed on a cyan cytometer (Dako Cytomation) using the Summit software (Beckman-Coulter).

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR was performed using ABI Prism 7300 sequence detection system software (v14.0). For absolute quantification of viral RNA, a sequence-tagged CHIKV-specific reverse transcription (RT) primer in the reverse transcription reaction mixture, CHIKV sequence-specific forward reverse primers, and an internal TaqMan probe were used as previously described (50). Standard curves were derived from 15-fold dilutions of the CHIKV infectious clone plasmid, which contained nonstructural CHIKV coding sequences. Real-time PCR was run using ABI Prism 7300 sequence detection system software (v14.0).

Quantitative protein analysis.

The treated ankle and foot from mock- or CHIKV-infected mice were harvested at the designated times and homogenized in sterile PBS. From the homogenates, protein levels of cytokines/chemokines were evaluated using multiplex bead array assays. All the antibodies and cytokine standards were purchased as antibody pairs from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) or Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Individual Luminex bead sets (Luminex, Riverside, CA) were coupled to cytokine-specific capture antibodies according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Biotinylated antibodies were used at twice the concentrations recommended for a classical enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer. All assay procedures were performed in assay buffer containing PBS supplemented with 1% normal mouse serum (Gibco BRL), 1% normal goat serum (Gibco BRL), and 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). The assays were run using 1,200 beads per set of each of the cytokines measured per well in a total volume of 50 μl. The plates were read on a Luminex MagPIX platform. For each bead set, >50 beads were collected. The median fluorescence intensities of the following cytokines/chemokines were recorded for each bead and used for analysis with the Milliplex software using a 5P regression algorithm: granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-15, IL-17α, IL-22, CXCL2/macrophage inflammatory protein 2α (MIP-2α), CXCL10/IP-10, CXCL1/KC, CXCL5/LIX, CXCL9/MIG, CXCL12/SDF1α, CXCL20/MIP-3α, CCL-2/monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), CCL3/MIP-1α, CCL-4/MIP-1β, CCL5/RANTES, CCL7/MCP-3, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α).

Statistical analyses.

All statistical analyses were performed within R (www.r-project.org). Data were transformed to fit normality (transformations are indicated in the descriptions of specific results) and analyzed within an analysis of variance (ANOVA) framework. Specifically, we used two-way ANOVA to examine the role of time postinfection and of different host genetics on various responses to infection. Within assay type, we utilized Bonferroni corrections to maintain stringency.

RESULTS

CHIKV infection increases activated γδ T cells at the site of infection and within the draining lymph nodes of C57B6/J mice.

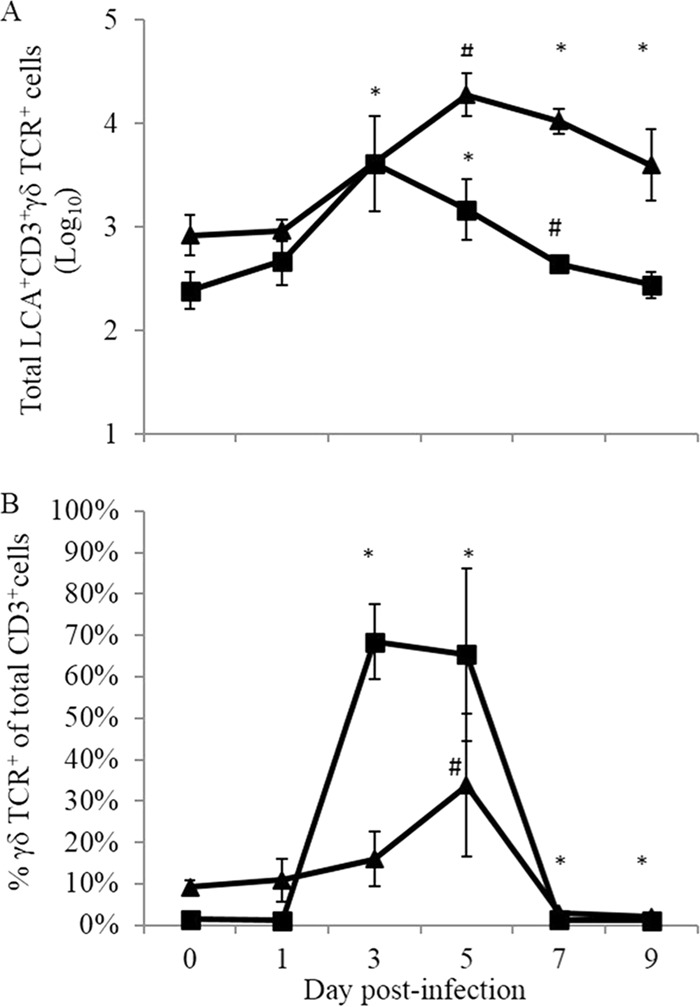

Although the contributions of αβ T cells to CHIKV clearance and pathogenesis have been examined (66, 68, 69, 85), to date no experiments have aimed at examining potential roles for γδ T cells in the disease process. To assess whether CHIKV infection of wild-type mice induced a γδ T cell response, infected feet and draining lymph nodes (DLNs) were harvested, and single-cell suspensions were assayed by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 1A, LCA+ CD3+ γδ TCR+ T cells significantly increased in number over day 0 levels by 3 to 7 days postinfection (dpi) in both the ipsilateral foot/ankle and DLNs following CHIKV infection. In addition to increased numbers, the proportion of all CD3+ γδ TCR+ T cells increased in both the DLNs and ipsilateral foot throughout the course of infection, with the percentage of CD3+ γδ TCR+ T cells peaking in the DLNs at 3 to 5 dpi and in the infected foot at 5 dpi (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Numbers and proportions of γδ T cells following CHIKV infection. C57BL/6J mice were infected in the left footpad with 100 PFU CHIKV, and tissues were harvested and processed for flow cytometry analysis. (A) Numbers of γδ T cells identified in both the ipsilateral foot (▲) and draining lymph node (■) at the times indicated postinfection. (B) Proportions of γδ T cells in the same tissues. *, P ≤ 0.05; #, P ≤ 0.01 (compared to day 0 values for each tissue, using a two-tailed t test).

This finding that γδ T cells rapidly accumulate at the site of infection and within the draining lymph nodes of CHIKV-infected C57BL/6J mice suggests that these cells are early responders to CHIKV infection in the mice and may affect the outcome of infection.

Mice lacking γδ T cells develop more severe CHIKV-induced disease than wild-type animals.

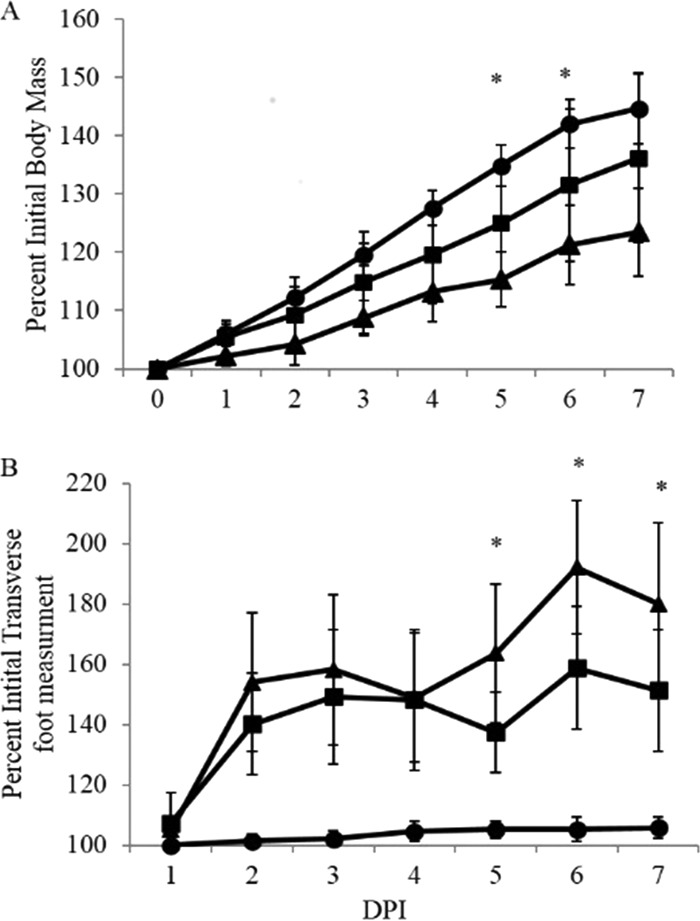

Previous studies demonstrated that C57BL/6J mice infected with a clinical isolate of CHIKV developed disease characterized by decreased weight gain and edema/swelling of the inoculated foot and that these disease signs correlated with inflammation and damage of infected tissues (59, 68). We directly assessed the role of γδ T cells in the pathogenesis of CHIKV infection by infecting 24-day-old mice deficient for the γδ TCR and wt mice with 100 PFU CHIKV in the left rear footpad. Mice were monitored daily for weight gain and swelling in the ipsilateral foot, measured using calipers. Clinically, CHIKV infection was more severe in γδ T−/− mice, evidenced by both their failure to gain weight at the same rate as infected wt mice (Fig. 2A) and more pronounced ipsilateral hind limb swelling measured at 5 to 7 dpi (Fig. 2B). These clinical disease differences correlated with the time of maximum γδ T cell presence at the site of infection, further supporting the idea that this T cell subset is a major player in the disease process and/or immune response to CHIKV infection.

FIG 2.

Mice lacking γδ T cells develop more severe CHIKV-induced clinical signs of disease than do wt C57BL/6J mice. Wild-type C57BL/6J (■), and γδ T−/− (▲) mice were infected with 100 PFU of CHIKV or mock infected (●) and monitored at 24-h intervals for signs of disease, including weight gain (A) and swelling of the ipsilateral foot, measured using calipers (B). Results are representative of four duplicate experiments (n = 5). Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed t test: *, P ≤ 0.05 (comparing C57BL/6J to γδT−/− CHIKV-infected animals).

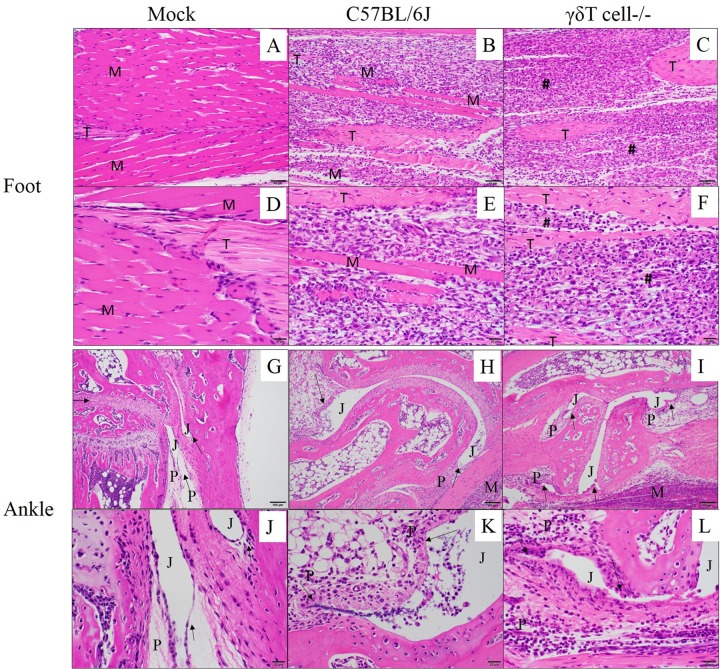

CHIKV infection induces greater inflammatory tissue damage in γδ T−/− mice than in wt mice.

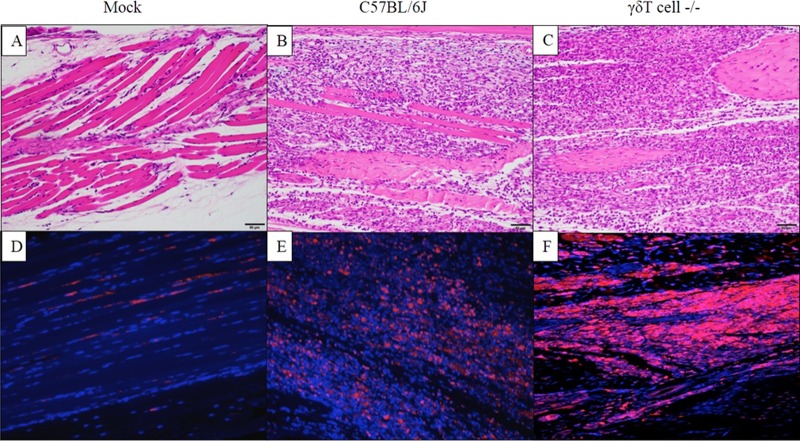

Footpad inoculation of C57BL/6J mice with CHIKV results in inflammation and musculoskeletal pathology, with peak severity from 7 to 10 dpi (68). In these studies, H&E staining was used to analyze inflammation and tissue damage following CHIKV infection of wt and γδ T−/− mice. Mock-infected feet displayed no significant histopathological changes (Fig. 3A and D). Both CHIKV-infected C57BL/6J (Fig. 3H and K) and γδ T−/− (Fig. 3I and L) joint tissues displayed variable histopathological changes compared to mock-infected tissues (Fig. 3G and J), but no noteworthy histopathologic differences were observed between wild-type and γδ T−/− mice. In either strain, following CHIKV infection, the synovium was expanded to a thickness of 2 to 4 cells by hypertrophied (reactive) synovial cells and infiltrating inflammatory cells. Perisynovial tissue appeared variably expanded by edema and mixed inflammation. Joint spaces variably contained scattered sloughed cells and infiltrating mixed inflammatory cells. In contrast to synovial joints, CHIKV-induced myositis within the foot was more severe in γδ T−/− mice than in wt C57BL/6 mice. CHIKV infection of wild-type mice resulted in abundant inflammatory cells replacing nearly all pedal myocytes which had been lost to necrosis (Fig. 3B and E). Myocyte loss and inflammation were even more severe in CHIKV-infected γδ T−/− mice, with complete replacement of myocytes by inflammation and associated tendons remaining only partially intact (Fig. 3C and F). Based on a lack of remaining myocytes in the γδ T−/− mice, it appears that the absence of γδ T cells increased tissue damage in the CHIKV-infected foot by 7 dpi. To qualitatively assess the degree of tissue damage at the site of CHIKV infection and replication, immunofluorescence was performed on sections from mock- and CHIKV-infected mice to detect nitrotyrosine (NT), a well-established marker of protein damage caused by oxidative stress. Nitrotyrosine is a stable end product of peroxynitrite oxidation and is a marker for inflammation and NO-dependent damage in vivo (86, 87). The presence of nitrotyrosine has been detected in various inflammatory processes, including arthritis in humans (88) and rodents (89). As shown in Fig. 4, compared to mock-infected mice (Fig. 4A and D), NT was increased at sites of inflammation in the ipsilateral foot of both C57BL/6J (Fig. 4B and E) and γδ T−/− mice (Fig. 4C and F). However, the presence of NT staining was enhanced in the infected feet of CHIKV-infected γδ T−/− mice compared to feet of wt animals. These data taken together with the clinical data and histological evidence of increased inflammation suggest that γδ T cells have a role in limiting inflammatory cell-induced tissue damage during CHIKV infection.

FIG 3.

Inflammatory cell infiltrate increases in CHIKV-infected tissues in the absence of γδ T cells. Twenty-four-day-old C57BL/6J or γδ T−/− mice (n = 5) were inoculated with diluent only (mock) or 100 PFU of CHIKV in the left rear footpad. At 7 dpi, mice were sacrificed and perfused by intracardial injection with 4% paraformaldehyde. Tissue sections of the ipsilateral foot (A to F) or ankle joint (G to L) were stained with H&E to determine the degree of inflammation and tissue damage at the various sites. M, muscle tissue; #, area of complete myocyte loss with replacement by inflammation; T, tendon; P, periarticular tissue; J, joint space; arrows, synovial lining. Photomicrographs were taken at 200× (A, B, C, G, H, and I) and 400× magnification (D, E, F, J, K, and L).

FIG 4.

Inflammatory cell infiltrate is associated with increased tissue damage in CHIKV-infected tissues in the absence of γδ T cells. Twenty-four-day-old C57BL/6J or γδ T−/− mice (n = 5) were inoculated with diluent only (mock) or 100 PFU of CHIKV in the left rear footpad. At 7 dpi, mice were sacrificed and perfused by intracardial injection with 4% paraformaldehyde. Tissue sections of the ipsilateral ankle joint and footpad were stained with H&E (A to C), and immunofluorescence was done to detect nitrotyrosine within sites of inflammation in the ipsilateral foot (D to F). Panels A to C are representative H&E images of the respective tissues labeled in panels D to F.

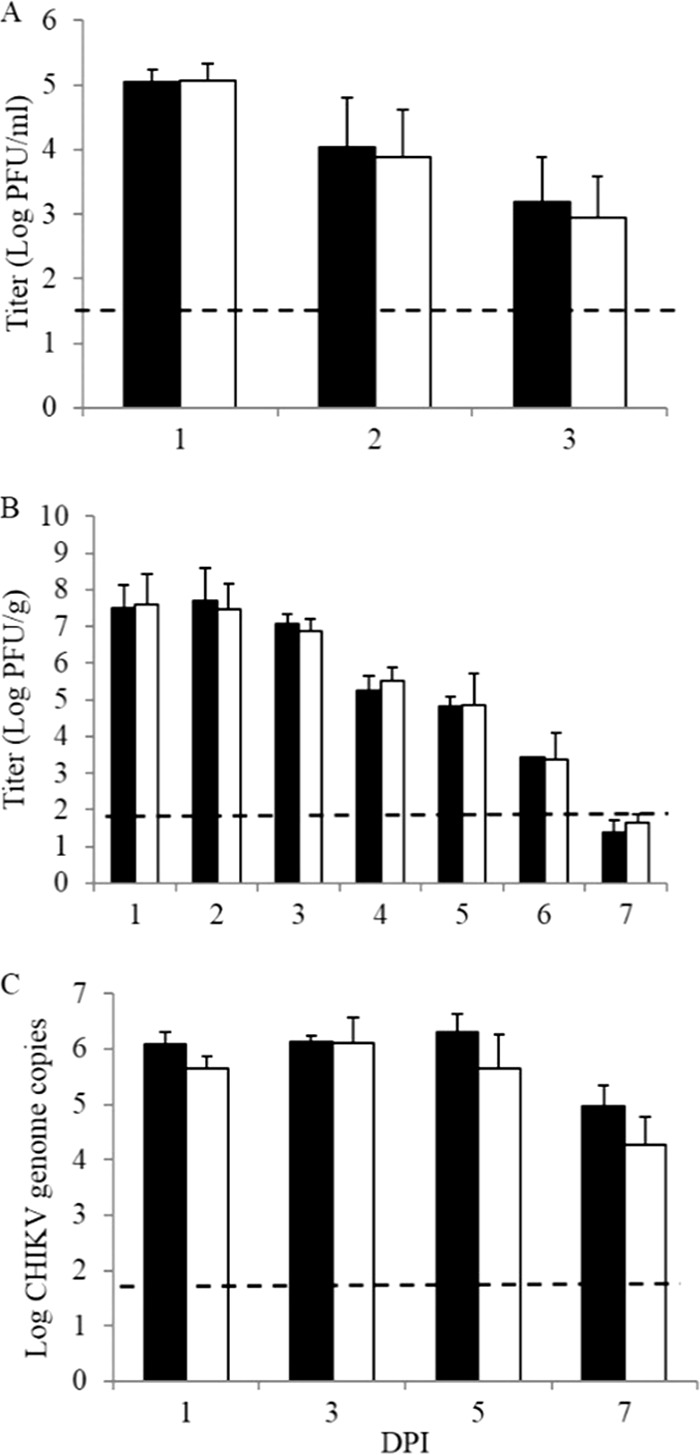

γδ TCR deficiency does not affect viral replication in vivo.

To determine if the increased severity of disease in γδ T−/− mice correlated with differences in viral titers, infectious virus levels were quantified by standard plaque assay. Serum samples and ipsi- and contralateral foot/ankle tissues were harvested from wt or γδ T−/− mice at 24-h intervals following infection with 100 PFU CHIKV. Tissues were homogenized in PBS and assayed on Vero cell monolayers. CHIKV replicated in the serum (Fig. 5A) and the ipsilateral foot/ankle (Fig. 5B) with no titer differences observed between C57BL/6J and γδ T−/− mice. Further, no difference in titer was observed in contralateral feet (data not shown). As confirmation, we ran CHIKV-specific real-time PCR to assess viral RNA copies, and we saw no difference in the amount of CHIKV RNA in the ipsilateral foot/ankle at 1 to 7 dpi (Fig. 5C). These results demonstrate that the increased disease and damage associated with CHIKV infection in γδ T−/− mice are not due to increased viral replication, spread, or the inability to clear virus.

FIG 5.

Absence of γδ T cells does not affect viral replication or clearance during acute CHIKV infection. (A and B) Twenty-four-day-old C57BL/6J (black bars) and γδ T−/− (white bars) mice were infected with 100 PFU CHIKV in the left rear footpad. Serum (A) and ipsilateral foot/ankle tissues (B) were harvested at the indicated times postinfection. Ankle/foot tissues were homogenized in PBS, and all samples were assayed on Vero cell monolayers in a standard plaque assay. (C) Total RNA was extracted from foot/ankle tissues of CHIKV- or mock-infected C57BL/6J and γδ T−/− mice by using the TRIzol RNA extraction protocol followed by reverse transcription using the SuperScript III reverse transcriptase system. CHIKV-specific real-time PCR was performed. Data represent mean viral titers and standard deviations and are representative of 3 independent experiments. Dashed lines indicate the limit of detection for each assay.

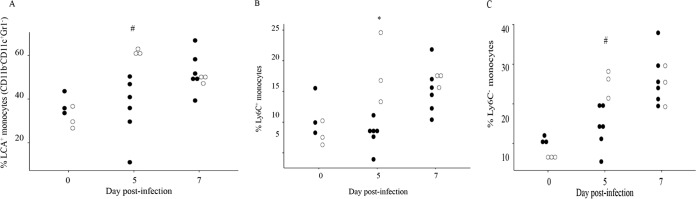

γδ T cell deficiency increases key populations of inflammatory cells in infected tissues.

Based on the finding that γδ T−/− mice have increased inflammation and damage within infected tissues despite equivalent viral titers, it was of interest to assess the composition of the inflammatory cell infiltrates. To this end, leukocytes were isolated from the ipsilateral foot/ankle tissues at 5 and 7 days after inoculation with 100 PFU in CHIKV into wt and γδ T−/− mice. At 5 dpi, the proportion of total monocytes (LCA+ CD11b+ CDllc-Gr1−), inflammatory Ly6C+ monocytes, and regulatory Ly6C− monocytes were all significantly increased in the γδ T−/− mice (Fig. 6A to C). Similar increases were not seen until day 7 in the wt animals. Given that monocytes/macrophages have been shown to contribute to CHIKV-induced inflammatory pathology (66), the finding that these monocyte populations were increased in the γδ T−/− but not wt mice at early times in the disease process suggests that γδ T cells may decrease early monocyte influx and help limit tissue damage caused by these cells.

FIG 6.

Absence of γδ T cells increases monocyte recruitment to the site of CHIKV infection at 5 dpi. Total cells were isolated from the foot/ankle tissues of C57BL/6J (■) (n = 6) and γδ T−/− mice (□) (n = 3) at 7 or 10 days postinfection. Viable cells were quantified by flow cytometry using the cell surface markers described in the text to determine the proportion of all LCA+ cells that were CD11b+ CD11c− Gr1− monocytes (A) and the proportions of monocytes that were Ly6C+ (B) or Ly6C− (C). *, P ≤ 0.05; #, P ≤ 0.01 by ANOVA.

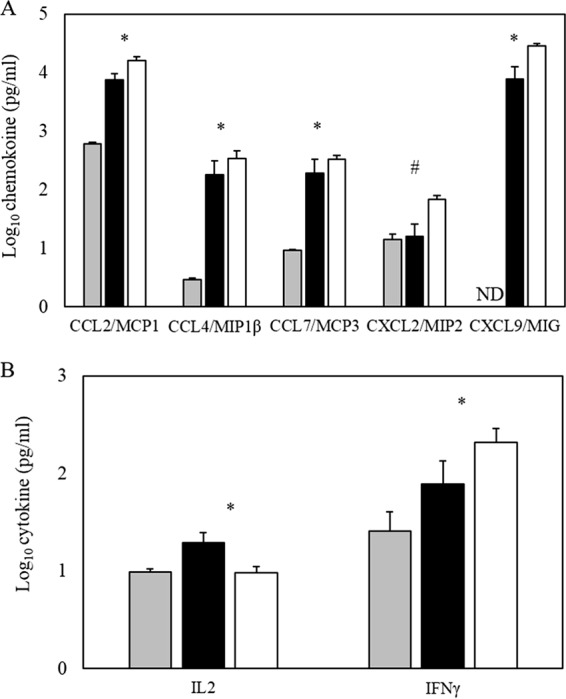

Lack of γδ T cells alters the levels of key mediators of inflammation at sites of CHIKV infection.

Based on histological and flow cytometry data indicating increased monocyte populations in the feet/ankles of γδ T cell-deficient versus wt mice following CHIKV infection, we investigated the impact of γδ T cell deficiency on production of various inflammatory cytokines and chemokines following CHIKV infection by using a multiplex ELISA for 24 unique cytokines and chemokines. C57BL/6J and γδ T−/− mice were infected, and foot/ankle tissues were harvested at 5 and 7 dpi. No differences in the levels of cytokines/chemokines were observed in mock-infected C57BL/6J or mock-infected γδ T−/− animals at any time postinfection (data not shown). Chemokine/cytokine responses could be grouped into three categories: a group in which levels were unchanged between mock- and CHIKV-infected animals at the time points analyzed, a group in which CHIKV infection led to increased expression but with no differences between the two mouse strains, and a third category in which wild-type and γδ T−/− mice exhibited significant differences in expression following CHIKV infection. In the first group, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-15, IL-17α, IL-22, and GM-CSF showed no detectable induction over mock-infected animals at the time points tested in wild-type or γδ T−/− mice (data not shown). Within the second group, comprising IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, IL12p70, and CXCL5/LIX, all showed induction following CHIKV infection, but no differences in expression were detected between the two mouse strains (data not shown). The last group was comprised of chemokines which showed enhanced expression in γδ T−/− compared to wild-type mice at day 7 postinfection: CCL2/MCP1, CCL4/MIP1β, CCL7/MCP3, CXCL2/MIP2, and CXCL9/MIG (Fig. 7A). The expression of IL-2 and IFN-γ, two key cytokines associated with T cell activation and function, were also differentially expressed in wild-type versus γδ T−/− mice (Fig. 7B), indicating that the absence of γδ T cells leads to altered cytokine/chemokine expression in response to CHIKV infection.

FIG 7.

Absence of γδ T cells alters CHIKV-induced cytokine expression 7 days following infection. The ankle and foot from CHIKV-infected C57BL/6J (black bars) or γδ T−/− (white bars) mice or mock-infected mice (gray bars) were harvested at 7 dpi and homogenized in sterile PBS. From the homogenates, cytokine concentrations were measured by multiplex ELISA using the Luminex MAGPIX platform. The average expression for each chemokine (A) and T cell-associated cytokine (B) are shown. Data represent mean amounts of total protein detected (in picograms per milliliter) (n = 5) and the error bars indicate standard deviations. ND, not detected. These data are representative of two independent experiments. Values for mock-treated C57BL/6J and γδ T−/− mice were not different, and the data shown are the averages of all mock animals of both genotypes. Statistical significance: *, P ≤ 0.05; #, P ≤ 0.01 (determined by Student's t test for C57BL/6J versus γδ T−/− animals).

DISCUSSION

Chikungunya virus infection in both humans and mouse models is characterized by inflammatory responses and histopathology that implicates immune-mediated pathology and modulation as drivers of CHIKV-induce disease (46–48, 50, 90, 91). Although some host immune pathways have been implicated in the recognition of CHIKV and subsequent induction of protective and pathogenic responses (59, 62, 67, 69, 82, 92–94), the precise mediators and mechanisms of CHIKV pathogenesis are still relatively poorly understood. Given the prevalence of γδ T cells in the skin, the primary site of CHIKV infection, and evidence that this T cell subset plays a role in the pathogenesis of other arboviruses (95–98), we tested whether γδ T cells played any role in the pathogenesis of CHIKV-induced disease. These studies demonstrated that CHIKV infection leads to significant increases in the prevalence of γδ T cells in both the foot and draining popliteal lymph node and that the absence of these cells leads to enhanced clinical signs of disease as well as CHIKV-induced histopathologic changes. Regulation of the host response to CHIKV by γδ T cells, evidenced by altered inflammatory cytokine expression and increased monocyte populations present at the site of infection, suggests that targeting of the inflammatory pathways that this T cell subset modulates may have therapeutic benefit in the treatment of CHIKV-induced and other alphavirus-induced inflammatory diseases.

An important role for γδ T cells is the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines that bias the inflammatory milieu toward a Th1-like environment as a response to infection or host cell dysregulation (99–101). In response to various bacterial and viral infections, γδ T cells can rapidly produce cytokines, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-17 (82, 102–105). However, mechanisms by which these pathogens elicit cytokine responses in γδ T cells are poorly understood. West Nile virus replication in γδ T cells induces proinflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ and TNF-α, as well as IL-17 and transforming growth factor β (80, 96); following West Nile virus infection of mice, γδ T cells expanded quickly and produced significant amounts of IFN-γ (82). While the impact of IFN-γ on the pathogenesis of CHIKV disease is somewhat controversial, with one study group finding that IFN-γ limited viral replication but not joint swelling (69) while another group found that IFN-γ promotes virus-induced swelling (85), our finding that mice lacking γδ T cells had increased IFN-γ production (Fig. 7B) suggests that it will be important to further analyze IFN-γ's role in the context of CHIKV infection.

In addition to cytokine production, γδ T cells have been described as a bridge between the innate and acquired immune responses by providing for the early and rapid movement and functions of key effector cells, such as neutrophils, macrophages, and NK cells, to the site of infection (74–76, 106, 107) and then downregulating the immune response after the danger has passed, to minimize potential immune-mediated injury (31, 72, 73, 96, 97). Monocytes have been shown to play a pathogenic role during CHIKV infection (66), and therefore the finding that monocyte numbers were increased in the foot/ankle of γδ T−/− mice suggests that γδ T cells may limit monocytic influx at day 5 and thereby decreasing the damage these cells cause within muscle tissue of the foot (Fig. 3 and 4).

In summary, these results suggest that γδ T cells may play a major role in regulating inflammatory responses within joint-associated tissues during the acute stages of CHIKV disease and that this occurs independently of changes in viral replication. These results suggest that further investigation of the role of γδ T cells in CHIKV pathogenesis may provide novel insights into how the host response modulates CHIKV-induced disease and lead to the identification of pathways which may be exploited for therapeutic or prophylactic therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff of the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center/Department of Laboratory Animal Medicine Histopathology Core at UNC Chapel Hill for histological processing and staining and Bob Bagnell, Jr., Director of the UNC Chapel Hill Microscopy Services Laboratory for training and assistance with microscopy. Both UNC resources are supported in part by an NCI Center Core support grant (CA16086).

REFERENCES

- 1.Powers AM, Logue CH. 2007. Changing patterns of Chikungunya virus: re-emergence of a zoonotic arbovirus. J Gen Virol 88:2363–2377. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82858-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lumsden WH. 1955. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952-53. II. General description and epidemiology. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 49:33–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson MC. 1955. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952-53. I. Clinical features. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 49:28–32. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(55)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suhrbier A, La Linn M. 2004. Clinical and pathologic aspects of arthritis due to Ross River virus and other alphaviruses. Curr Opin Rheumatol 16:374–379. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000130537.76808.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuffenecker I, Iteman I, Michault A, Murri S, Frangeul L, Vaney MC, Lavenir R, Pardigon N, Reynes JM, Pettinelli F, Biscornet L, Diancourt L, Michel S, Duquerroy S, Guigon G, Frenkiel MP, Brehin AC, Cubito N, Despres P, Kunst F, Rey FA, Zeller H, Brisse S. 2006. Genome microevolution of chikungunya viruses causing the Indian Ocean outbreak. PLoS Med 3:e263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon F, Tolou H, Jeandel P. 2006. The unexpected Chikungunya outbreak. Rev Med Interne 27:437–441. (In French.) doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sergon K, Njuguna C, Kalani R, Ofula V, Onyango C, Konongoi LS, Bedno S, Burke H, Dumilla AM, Konde J, Njenga MK, Sang R, Breiman RF. 2008. Seroprevalence of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection on Lamu Island, Kenya, October 2004. Am J Trop Med Hyg 78:333–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sergon K, Yahaya AA, Brown J, Bedja SA, Mlindasse M, Agata N, Allaranger Y, Ball MD, Powers AM, Ofula V, Onyango C, Konongoi LS, Sang R, Njenga MK, Breiman RF. 2007. Seroprevalence of Chikungunya virus infection on Grande Comore Island, union of the Comoros, 2005. Am J Trop Med Hyg 76:1189–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laras K, Sukri NC, Larasati RP, Bangs MJ, Kosim R, Djauzi Wandra T, Master J, Kosasih H, Hartati S, Beckett C, Sedyaningsih ER, Beecham HJ III, Corwin AL. 2005. Tracking the re-emergence of epidemic Chikungunya virus in Indonesia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 99:128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochedez P, Jaureguiberry S, Debruyne M, Bossi P, Hausfater P, Brucker G, Bricaire F, Caumes E. 2006. Chikungunya infection in travelers. Emerg Infect Dis 12:1565–1567. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.060495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon F, Savini H, Parola P. 2008. Chikungunya: a paradigm of emergence and globalization of vector-borne diseases. Med Clin North Am 92:1323–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parola P, de Lamballerie X, Jourdan J, Rovery C, Vaillant V, Minodier P, Brouqui P, Flahault A, Raoult D, Charrel RN. 2006. Novel Chikungunya virus variant in travelers returning from Indian Ocean islands. Emerg Infect Dis 12:1493–1499. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.060610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeffer M, Loscher T. 2006. Cases of chikungunya imported into Europe. Euro Surveill 11(3):E060316.2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pialoux G, Gauzere BA, Jaureguiberry S, Strobel M. 2007. Chikungunya, an epidemic arbovirosis. Lancet Infect Dis 7:319–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70107-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bottieau E, Van Esbroeck M, Cnops L, Clerinx J, Van Gompel A. 2009. Chikungunya infection confirmed in a Belgian traveller returning from Phuket (Thailand). Euro Surveill 14(25):pii=19248 http://www. eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?Articleid=19247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rezza G, Nicoletti L, Angelini R, Romi R, Finarelli AC, Panning M, Cordioli P, Fortuna C, Boros S, Magurano F, Silvi G, Angelini P, Dottori M, Ciufolini MG, Majori GC, Cassone A, CHIKV Study Group . 2007. Infection with Chikungunya virus in Italy: an outbreak in a temperate region. Lancet 370:1840–1846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61779-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beltrame A, Angheben A, Bisoffi Z, Monteiro G, Marocco S, Calleri G, Lipani F, Gobbi F, Canta F, Castelli F, Gulletta M, Bigoni S, Del Punta V, Iacovazzi T, Romi R, Nicoletti L, Ciufolini MG, Rorato G, Negri C, Viale P. 2007. Imported Chikungunya infection, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis 13:1264–1266. doi: 10.3201/eid1308.070161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angelini P, Macini P, Finarelli AC, Pol C, Venturelli C, Bellini R, Dottori M. 2008. Chikungunya epidemic outbreak in Emilia-Romagna (Italy) during summer 2007. Parassitologia 50:97–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angelini R, Finarelli AC, Angelini P, Po C, Petropulacos K, Macini P, Fiorentini C, Fortuna C, Venturi G, Romi R, Majori G, Nicoletti L, Rezza G, Cassone A. 2007. An outbreak of Chikungunya fever in the province of Ravenna, Italy. Euro Surveill 12(36):pii=3260 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussain R, Alomar I, Memish ZA. 2013. Chikungunya virus: emergence of an arthritic arbovirus in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J 19:506–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cassadou S, Boucau S, Petit-Sinturel M, Huc P, Leparc-Goffart I, Ledrans M. 2014. Emergence of Chikungunya fever on the French side of Saint Martin island, October to December 2013. Euro Surveill 19(13):pii=20752. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.13.20752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leparc-Goffart I, Nougairede A, Cassadou S, Prat C, de Lamballerie X. 2014. Chikungunya in the Americas. Lancet 383:514. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Bortel W, Dorleans F, Rosine J, Blateau A, Rousset D, Matheus S, Leparc-Goffart I, Flusin O, Prat C, Cesaire R, Najioullah F, Ardillon V, Balleydier E, Carvalho L, Lemaitre A, Noel H, Servas V, Six C, Zurbaran M, Leon L, Guinard A, van den Kerkhof J, Henry M, Fanoy E, Braks M, Reimerink J, Swaan C, Georges R, Brooks L, Freedman J, Sudre B, Zeller H. 2014. Chikungunya outbreak in the Caribbean region, December 2013 to March 2014, and the significance for Europe. Euro Surveill 19(13):pii=20759. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.13.20759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014. Chikungunya virus. CDC, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Economopoulou A, Dominguez M, Helynck B, Sissoko D, Wichmann O, Quenel P, Germonneau P, Quatresous I. 2009. Atypical Chikungunya virus infections: clinical manifestations, mortality and risk factors for severe disease during the 2005-2006 outbreak on Reunion. Epidemiol Infect 137:534–541. doi: 10.1017/S0950268808001167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Josseran L, Paquet C, Zehgnoun A, Caillere N, Le Tertre A, Solet JL, Ledrans M. 2006. Chikungunya disease outbreak, Reunion Island. Emerg Infect Dis 12:1994–1995. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chua HH, Abdul Rashid K, Law WC, Hamizah A, Chem YK, Khairul AH, Chua KB. 2010. A fatal case of Chikungunya virus infection with liver involvement. Med J Malaysia 65:83–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rampal Sharda M, Meena H. 2007. Neurological complications in Chikungunya fever. J Assoc Physicians India 55:765–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rampal Sharda M, Meena H. 2007. Hypokalemic paralysis following Chikungunya fever. J Assoc Physicians India 55:598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wielanek AC, Monredon JD, Amrani ME, Roger JC, Serveaux JP. 2007. Guillain-Barre syndrome complicating a Chikungunya virus infection. Neurology 69:2105–2107. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000277267.07220.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vazeille M, Jeannin C, Martin E, Schaffner F, Failloux AB. 2008. Chikungunya: a risk for Mediterranean countries? Acta Trop 105:200–202. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vazeille M, Moutailler S, Coudrier D, Rousseaux C, Khun H, Huerre M, Thiria J, Dehecq JS, Fontenille D, Schuffenecker I, Despres P, Failloux AB. 2007. Two Chikungunya isolates from the outbreak of La Reunion (Indian Ocean) exhibit different patterns of infection in the mosquito, Aedes albopictus. PLoS One 2:e1168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsetsarkin KA, Vanlandingham DL, McGee CE, Higgs S. 2007. A single mutation in Chikungunya virus affects vector specificity and epidemic potential. PLoS Pathog 3:e201. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diallo M, Thonnon J, Traore-Lamizana M, Fontenille D. 1999. Vectors of Chikungunya virus in Senegal: current data and transmission cycles. Am J Trop Med Hyg 60:281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delatte H, Dehecq JS, Thiria J, Domerg C, Paupy C, Fontenille D. 2008. Geographic distribution and developmental sites of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) during a Chikungunya epidemic event. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 8:25–34. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon F, Parola P, Grandadam M, Fourcade S, Oliver M, Brouqui P, Hance P, Kraemer P, Ali Mohamed A, de Lamballerie X, Charrel R, Tolou H. 2007. Chikungunya infection: an emerging rheumatism among travelers returned from Indian Ocean islands. Report of 47 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 86:123–137. doi: 10.1097/MD/0b013e31806010a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sissoko D, Malvy D, Ezzedine K, Renault P, Moscetti F, Ledrans M, Pierre V. 2009. Post-epidemic Chikungunya disease on Reunion Island: course of rheumatic manifestations and associated factors over a 15-month period. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3:e389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mourya DT, Mishra AC. 2006. Chikungunya fever. Lancet 368:186–187. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69017-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yazdani R, Kaushik VV. 2007. Chikungunya fever. Rheumatology (Oxford) 46:1214–1215. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fourie ED, Morrison JG. 1979. Rheumatoid arthritic syndrome after Chikungunya fever. S Afr Med J 56:130–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kennedy AC, Fleming J, Solomon L. 1980. Chikungunya viral arthropathy: a clinical description. J Rheumatol 7:231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brighton SW, Simson IW. 1984. A destructive arthropathy following Chikungunya virus arthritis: a possible association. Clin Rheumatol 3:253–258. doi: 10.1007/BF02030766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manimunda SP, Vijayachari P, Uppoor R, Sugunan AP, Singh SS, Rai SK, Sudeep AB, Muruganandam N, Chaitanya IK, Guruprasad DR. 2010. Clinical progression of Chikungunya fever during acute and chronic arthritic stages and the changes in joint morphology as revealed by imaging. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 104:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soumahoro MK, Gerardin P, Boelle PY, Perrau J, Fianu A, Pouchot J, Malvy D, Flahault A, Favier F, Hanslik T. 2009. Impact of Chikungunya virus infection on health status and quality of life: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 4:e7800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Essackjee K, Goorah S, Ramchurn SK, Cheeneebash J, Walker-Bone K. 2013. Prevalence of and risk factors for chronic arthralgia and rheumatoid-like polyarthritis more than 2 years after infection with chikungunya virus. Postgrad Med J 89:440–447. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poo YS, Nakaya H, Gardner J, Larcher T, Schroder WA, Le TT, Major LD, Suhrbier A. 2014. CCR2 deficiency promotes exacerbated chronic erosive neutrophil-dominated Chikungunya virus arthritis. J Virol 88:6862–6872. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03364-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoarau JJ, Gay F, Pelle O, Samri A, Jaffar-Bandjee MC, Gasque P, Autran B. 2013. Identical strength of the T cell responses against E2, nsP1 and capsid CHIKV proteins in recovered and chronic patients after the epidemics of 2005-2006 in La Reunion Island. PLoS One 8:e84695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawman DW, Stoermer KA, Montgomery SA, Pal P, Oko L, Diamond MS, Morrison TE. 2013. Chronic joint disease caused by persistent Chikungunya virus infection is controlled by the adaptive immune response. J Virol 87:13878–13888. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02666-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dupuis-Maguiraga L, Noret M, Brun S, Le Grand R, Gras G, Roques P. 2012. Chikungunya disease: infection-associated markers from the acute to the chronic phase of arbovirus-induced arthralgia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6:e1446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stoermer KA, Burrack A, Oko L, Montgomery SA, Borst LB, Gill RG, Morrison TE. 2012. Genetic ablation of arginase 1 in macrophages and neutrophils enhances clearance of an arthritogenic alphavirus. J Immunol 189:4047–4059. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kam YW, Simarmata D, Chow A, Her Z, Teng TS, Ong EK, Renia L, Leo YS, Ng LF. 2012. Early appearance of neutralizing immunoglobulin G3 antibodies is associated with Chikungunya virus clearance and long-term clinical protection. J Infect Dis 205:1147–1154. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jupille HJ, Oko L, Stoermer KA, Heise MT, Mahalingam S, Gunn BM, Morrison TE. 2011. Mutations in nsP1 and PE2 are critical determinants of Ross River virus-induced musculoskeletal inflammatory disease in a mouse model. Virology 410:216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morrison TE, Simmons JD, Heise MT. 2008. Complement receptor 3 promotes severe ross river virus-induced disease. J Virol 82:11263–11272. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01352-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morrison TE, Fraser RJ, Smith PN, Mahalingam S, Heise MT. 2007. Complement contributes to inflammatory tissue destruction in a mouse model of Ross River virus-induced disease. J Virol 81:5132–5143. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02799-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morrison TE, Whitmore AC, Shabman RS, Lidbury BA, Mahalingam S, Heise MT. 2006. Characterization of Ross River virus tropism and virus-induced inflammation in a mouse model of viral arthritis and myositis. J Virol 80:737–749. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.737-749.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gunn BM, Morrison TE, Whitmore AC, Blevins LK, Hueston L, Fraser RJ, Herrero LJ, Ramirez R, Smith PN, Mahalingam S, Heise MT. 2012. Mannose binding lectin is required for alphavirus-induced arthritis/myositis. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002586. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lidbury BA, Simeonovic C, Maxwell GE, Marshall ID, Hapel AJ. 2000. Macrophage-induced muscle pathology results in morbidity and mortality for Ross River virus-infected mice. J Infect Dis 181:27–34. doi: 10.1086/315164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Den Bossche D, Cnops L, Meersman K, Domingo C, Van Gompel A, Van Esbroeck M. 2015. Chikungunya virus and West Nile virus infections imported into Belgium, 2007-2012. Epidemiol Infect 143:2227–2236. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814000685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Long KM, Whitmore AC, Ferris MT, Sempowski GD, McGee C, Trollinger B, Gunn B, Heise MT. 2013. Dendritic cell immunoreceptor regulates Chikungunya virus pathogenesis in mice. J Virol 87:5697–5706. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01611-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wauquier N, Becquart P, Nkoghe D, Padilla C, Ndjoyi-Mbiguino A, Leroy EM. 2011. The acute phase of Chikungunya virus infection in humans is associated with strong innate immunity and T CD8 cell activation. J Infect Dis 204:115–123. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Couderc T, Chretien F, Schilte C, Disson O, Brigitte M, Guivel-Benhassine F, Touret Y, Barau G, Cayet N, Schuffenecker I, Despres P, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Michault A, Albert ML, Lecuit M. 2008. A mouse model for Chikungunya: young age and inefficient type-I interferon signaling are risk factors for severe disease. PLoS Pathog 4:e29. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schilte C, Couderc T, Chretien F, Sourisseau M, Gangneux N, Guivel-Benhassine F, Kraxner A, Tschopp J, Higgs S, Michault A, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Colonna M, Peduto L, Schwartz O, Lecuit M, Albert ML. 2010. Type I IFN controls Chikungunya virus via its action on nonhematopoietic cells. J Exp Med 207:429–442. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Werneke SW, Schilte C, Rohatgi A, Monte KJ, Michault A, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Vanlandingham DL, Higgs S, Fontanet A, Albert ML, Lenschow DJ. 2011. ISG15 is critical in the control of Chikungunya virus infection independent of UbE1L mediated conjugation. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002322. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gardner CL, Burke CW, Higgs ST, Klimstra WB, Ryman KD. 2012. Interferon-alpha/beta deficiency greatly exacerbates arthritogenic disease in mice infected with wild-type Chikungunya virus but not with the cell culture-adapted live-attenuated 181/25 vaccine candidate. Virology 425:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Teng TS, Foo SS, Simamarta D, Lum FM, Teo TH, Lulla A, Yeo NK, Koh EG, Chow A, Leo YS, Merits A, Chin KC, Ng LF. 2012. Viperin restricts Chikungunya virus replication and pathology. J Clin Invest 122:4447–4460. doi: 10.1172/JCI63120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gardner J, Anraku I, Le TT, Larcher T, Major L, Roques P, Schroder WA, Higgs S, Suhrbier A. 2010. Chikungunya virus arthritis in adult wild-type mice. J Virol 84:8021–8032. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02603-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lum FM, Teo TH, Lee WW, Kam YW, Renia L, Ng LF. 2013. An essential role of antibodies in the control of Chikungunya virus infection. J Immunol 190:6295–6302. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morrison TE, Oko L, Montgomery SA, Whitmore AC, Lotstein AR, Gunn BM, Elmore SA, Heise MT. 2011. A mouse model of Chikungunya virus-induced musculoskeletal inflammatory disease: evidence of arthritis, tenosynovitis, myositis, and persistence. Am J Pathol 178:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Teo TH, Lum FM, Claser C, Lulla V, Lulla A, Merits A, Renia L, Ng LF. 2013. A pathogenic role for CD4+ T cells during Chikungunya virus infection in mice. J Immunol 190:259–269. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee WW, Teo TH, Her Z, Lum FM, Kam YW, Haase D, Renia L, Rotzschke O, Ng LF. 2015. Expanding regulatory T cells alleviates Chikungunya virus-induced pathology in mice. J Virol 89:7893–7904. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00998-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hayday AC. 2000. γδ cells: a right time and a right place for a conserved third way of protection. Annu Rev Immunol 18:975–1026. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Born W, Cady C, Jones-Carson J, Mukasa A, Lahn M, O'Brien R. 1999. Immunoregulatory functions of gamma delta T cells. Adv Immunol 71:77–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carding SR, Egan PJ. 2002. γδ T cells: functional plasticity and heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol 2:336–345. doi: 10.1038/nri797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Egan PJ, Carding SR. 2000. Downmodulation of the inflammatory response to bacterial infection by γδ T cells cytotoxic for activated macrophages. J Exp Med 191:2145–2158. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.12.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fu YX, Roark CE, Kelly K, Drevets D, Campbell P, O'Brien R, Born W. 1994. Immune protection and control of inflammatory tissue necrosis by gamma delta T cells. J Immunol 153:3101–3115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.D'Souza CD, Cooper AM, Frank AA, Mazzaccaro RJ, Bloom BR, Orme IM. 1997. An anti-inflammatory role for gamma delta T lymphocytes in acquired immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol 158:1217–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hisaeda H, Sakai T, Nagasawa H, Ishikawa H, Yasutomo K, Maekawa Y, Himeno K. 1996. Contribution of extrathymic gamma delta T cells to the expression of heat-shock protein and to protective immunity in mice infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Immunology 88:551–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-694.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dalton JE, Pearson J, Scott P, Carding SR. 2003. The interaction of gamma delta T cells with activated macrophages is a property of the V gamma 1 subset. J Immunol 171:6488–6494. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tramonti D, Rhodes K, Martin N, Dalton JE, Andrew E, Carding SR. 2008. γδ T cell-mediated regulation of chemokine producing macrophages during Listeria monocytogenes infection-induced inflammation. J Pathol 216:262–270. doi: 10.1002/path.2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fang H, Welte T, Zheng X, Chang GJ, Holbrook MR, Soong L, Wang T. 2010. γδ T cells promote the maturation of dendritic cells during West Nile virus infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 59:71–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Safavi F, Feliberti JP, Raine CS, Mokhtarian F. 2011. Role of γδ T cells in antibody production and recovery from SFV demyelinating disease. J Neuroimmunol 235:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang T, Scully E, Yin Z, Kim JH, Wang S, Yan J, Mamula M, Anderson JF, Craft J, Fikrig E. 2003. IFN-gamma-producing gamma delta T cells help control murine West Nile virus infection. J Immunol 171:2524–2531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Paessler S, Ni H, Petrakova O, Fayzulin RZ, Yun N, Anishchenko M, Weaver SC, Frolov I. 2006. Replication and clearance of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus from the brains of animals vaccinated with chimeric SIN/VEE viruses. J Virol 80:2784–2796. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2784-2796.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Paessler S, Yun NE, Judy BM, Dziuba N, Zacks MA, Grund AH, Frolov I, Campbell GA, Weaver SC, Estes DM. 2007. Alpha-beta T cells provide protection against lethal encephalitis in the murine model of VEEV infection. Virology 367:307–323. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nakaya HI, Gardner J, Poo YS, Major L, Pulendran B, Suhrbier A. 2012. Gene profiling of Chikungunya virus arthritis in a mouse model reveals significant overlap with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 64:3553–3563. doi: 10.1002/art.34631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Crow JP, Beckman JS. 1995. Reactions between nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: footprints of peroxynitrite in vivo. Adv Pharmacol 34:17–43. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(08)61079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Crow JP, Beckman JS. 1995. The role of peroxynitrite in nitric oxide-mediated toxicity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 196:57–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kaur H, Halliwell B. 1994. Evidence for nitric oxide-mediated oxidative damage in chronic inflammation. Nitrotyrosine in serum and synovial fluid from rheumatoid patients. FEBS Lett 350:9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nemirovskiy OV, Radabaugh MR, Aggarwal P, Funckes-Shippy CL, Mnich SJ, Meyer DM, Sunyer T, Rodney Mathews W, Misko TP. 2009. Plasma 3-nitrotyrosine is a biomarker in animal models of arthritis: pharmacological dissection of iNOS' role in disease. Nitric Oxide 20:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rulli NE, Rolph MS, Srikiatkhachorn A, Anantapreecha S, Guglielmotti A, Mahalingam S. 2011. Protection from arthritis and myositis in a mouse model of acute Chikungunya virus disease by bindarit, an inhibitor of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 synthesis. J Infect Dis 204:1026–1030. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kelvin AA, Banner D, Silvi G, Moro ML, Spataro N, Gaibani P, Cavrini F, Pierro A, Rossini G, Cameron MJ, Bermejo-Martin JF, Paquette SG, Xu L, Danesh A, Farooqui A, Borghetto I, Kelvin DJ, Sambri V, Rubino S. 2011. Inflammatory cytokine expression is associated with chikungunya virus resolution and symptom severity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5:e1279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schilte C, Buckwalter MR, Laird ME, Diamond MS, Schwartz O, Albert ML. 2012. Cutting edge: independent roles for IRF-3 and IRF-7 in hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells during host response to Chikungunya infection. J Immunol 188:2967–2971. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kam YW, Ong EK, Renia L, Tong JC, Ng LF. 2009. Immuno-biology of Chikungunya and implications for disease intervention. Microbes Infect 11:1186–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Clavarino G, Claudio N, Couderc T, Dalet A, Judith D, Camosseto V, Schmidt EK, Wenger T, Lecuit M, Gatti E, Pierre P. 2012. Induction of GADD34 is necessary for dsRNA-dependent interferon-beta production and participates in the control of Chikungunya virus infection. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002708. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Welte T, Lamb J, Anderson JF, Born WK, O'Brien RL, Wang T. 2008. Role of two distinct γδ T cell subsets during West Nile virus infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 53:275–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang T. 2011. Role of γδ T cells in West Nile virus-induced encephalitis: friend or foe? J Neuroimmunol 240–241:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroim.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Welte T, Aronson J, Gong B, Rachamallu A, Mendell N, Tesh R, Paessler S, Born WK, O'Brien RL, Wang T. 2011. Vγ4+ T cells regulate host immune response to West Nile virus infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 63:183–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00840.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Griffin DE, Levine B, Tyor WR, Irani DN. 1992. The immune response in viral encephalitis. Semin Immunol 4:111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chomarat P, Kjeldsen-Kragh J, Quayle AJ, Natvig JB, Miossec P. 1994. Different cytokine production profiles of gamma delta T cell clones: relation to inflammatory arthritis. Eur J Immunol 24:2087–2091. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Huber S, Shi C, Budd RC. 2002. γδ T cells promote a Th1 response during coxsackievirus B3 infection in vivo: role of Fas and Fas ligand. J Virol 76:6487–6494. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6487-6494.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nishimura H, Yajima T, Kagimoto Y, Ohata M, Watase T, Kishihara K, Goshima F, Nishiyama Y, Yoshikai Y. 2004. Intraepithelial γδ T cells may bridge a gap between innate immunity and acquired immunity to herpes simplex virus type 2. J Virol 78:4927–4930. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4927-4930.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ferrick DA, King DP, Jackson KA, Braun RK, Tam S, Hyde DM, Beaman BL. 2000. Intraepithelial gamma delta T lymphocytes: sentinel cells at mucosal barriers. Springer Semin Immunopathol 22:283–296. doi: 10.1007/s002810000047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.O'Brien RL, Roark CL, Born WK. 2009. IL-17-producing γδ T cells. Eur J Immunol 39:662–666. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Aoyagi M, Shimojo N, Sekine K, Nishimuta T, Kohno Y. 2003. Respiratory syncytial virus infection suppresses IFN-gamma production of γδ T cells. Clin Exp Immunol 131:312–317. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Toka FN, Kenney MA, Golde WT. 2011. Rapid and transient activation of γδ T cells to IFN-γ production, NK cell-like killing, and antigen processing during acute virus infection. J Immunol 186:4853–4861. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tagawa T, Nishimura H, Yajima T, Hara H, Kishihara K, Matsuzaki G, Yoshino I, Maehara Y, Yoshikai Y. 2004. Vδ1+ γδ T cells producing CC chemokines may bridge a gap between neutrophils and macrophages in innate immunity during Escherichia coli infection in mice. J Immunol 173:5156–5164. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Vincent MS, Roessner K, Lynch D, Wilson D, Cooper SM, Tschopp J, Sigal LH, Budd RC. 1996. Apoptosis of Fas high CD4+ synovial T cells by borrelia-reactive Fas-ligandhigh gamma delta T cells in Lyme arthritis. J Exp Med 184:2109–2117. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]