Abstract

Oenococcus oeni is a wine-associated lactic acid bacterium mostly responsible for malolactic fermentation in wine. In wine, O. oeni grows in an environment hostile to bacterial growth (low pH, low temperature, and ethanol) that induces stress response mechanisms. To survive, O. oeni is known to set up transitional stress response mechanisms through the synthesis of heat stress proteins (HSPs) encoded by the hsp genes, notably a unique small HSP named Lo18. Despite the availability of the genome sequence, characterization of O. oeni genes is limited, and little is known about the in vivo role of Lo18. Due to the lack of genetic tools for O. oeni, an efficient expression vector in O. oeni is still lacking, and deletion or inactivation of the hsp18 gene is not presently practicable. As an alternative approach, with the goal of understanding the biological function of the O. oeni hsp18 gene in vivo, we have developed an expression vector to produce antisense RNA targeting of hsp18 mRNA. Recombinant strains were exposed to multiple stresses inducing hsp18 gene expression: heat shock and acid shock. We showed that antisense attenuation of hsp18 affects O. oeni survival under stress conditions. These results confirm the involvement of Lo18 in heat and acid tolerance of O. oeni. Results of anisotropy experiments also confirm a membrane-protective role for Lo18, as previous observations had already suggested. This study describes a new, efficient tool to demonstrate the use of antisense technology for modulating gene expression in O. oeni.

INTRODUCTION

Oenococcus oeni is a wine-associated lactic acid bacterium mostly responsible for wine malolactic fermentation (MLF) (1). In wine medium, O. oeni evolves under extreme physicochemical conditions: low pH (3.2 to 3.5), low temperature (18°C), and the presence of biological competitors such as yeast, producing inhibitory compounds, i.e., fatty acids, ethanol, 2-phenylethanol, and sulfites. The winemaking process itself may also constitute a hostile factor for bacterial growth. All these hostile environmental factors can cause a delay in MLF initiation. Thus, this fermentation step is currently not yet fully managed. However, the gradual increase in the ethanol level in wine during the alcoholic fermentation performed by yeasts and the production of substances inhibiting growth of lactic acid bacteria (dodecanoic acid or decanoic acid) led to the selection of the species most suited and adapted to wine conditions: O. oeni (1, 2). A better understanding of the mechanisms involved in stress-adaptive responses is essential to improve O. oeni development in wine and to perfect industrial processes of preparing wine malolactic starter. Because of its acidophilic properties, O. oeni is an interesting model for investigating stress response mechanisms in lactic acid bacteria (LAB). Like any organism undergoing an environmental stress, O. oeni tries to restore a metabolic profile beneficial for survival. Over the past decades, several mechanisms involved in adaptation to wine were described, including genes related to the general stress response, membrane composition and fluidity, pH homeostasis, the oxidative stress response, and DNA damage (3–8). To survive, O. oeni is known to set up transitional stress response mechanisms through the synthesis of heat stress proteins (HSPs) encoded by the hsp genes, notably a single small HSP (sHSP) named Lo18 (3, 6, 9, 10), whose synthesis is induced by multiple stresses such as heat, ethanol, low pH, or addition of benzyl alcohol membrane fluidifier (5, 11–13). sHSPs are ubiquitous proteins found throughout all biological domains and characterized by a sequence of about 100 amino acids residues called the α-crystallin (14). These proteins have a cytoplasmic molecular chaperone activity, and some of them were shown to be membrane associated and to play a role in membrane quality control (15).

Several studies have investigated Lo18 function in vitro using either heterologous (11, 16) or in vitro (17) systems. Under stress conditions, Lo18 is produced in large amounts (10), notably during ethanol stress (5, 10). Lo18 was shown to interact with the cytoplasmic membrane under stress conditions, suggesting that Lo18 could be involved in stress adaptation as a lipochaperone (5). Possible lipochaperone activity and molecular chaperone activity of Lo18 have been examined in vitro. Purified Lo18 protein was able to stabilize liposome fluidity (5) and to prevent protein aggregation (18). Since O. oeni is not a genetically tractable bacterium and has no available efficient expression plasmid for genetic studies, mutant construction is not presently practicable for investigating Lo18 function in vivo. Over the three last decades, the characterization of extrachromosomal DNA and genetic transformation techniques in O. oeni have received considerable attention. O. oeni transformation is presently possible by electroporation (19). Nevertheless, an efficient expression vector in O. oeni is still missing, and site-directed mutagenesis is presently not achievable because transformation efficiencies are lower than the frequency of recombination events (19, 20). Due to the lack of genetic tools for mutagenesis in O. oeni, we have focused our research on the antisense mechanism to modulate expression of target genes.

Antisense RNA (asRNA) was defined by Good as “natural or synthetic polymers that specifically recognize and inhibit target sense sequences, with mRNA being the usual target” (21). Diverse antisense mechanisms exist, and the term designates all mechanisms using sequence-specific mRNA recognition leading to reduced or altered expression of a transcript or a sense RNA (22). Antisense mechanisms are very common in nature and can affect mRNA transcription by inducing destruction and repression. Based on base pairing, the asRNA strategy is exploited for protein synthesis inhibition. Because asRNA action does not require modification of the organism's chromosomal DNA, it has a higher throughput than traditional gene inactivation. Moreover, gene deletion strategies are feasible only if the genes are not essential for bacteria survival. While permanent directed inactivation is termed gene knockout, antisense RNA-based gene silencing is described as gene knockdown. Indeed, expression of unmodified RNA targeting the exact antiparallel mRNA sequence is the simplest use of asRNA. Translation inhibition is mainly due either to steric hindrance blocking the translation machinery or to rapid degradation of double-stranded RNA by specific RNases (22). Several studies using asRNA have already been carried out in LAB, demonstrating RNA base-pairing gene inhibition. Baouazzaoui and Lapointe modified the molecular mass of exopolysaccharide by modulating glycosyltransferase gene (welE) expression using asRNA in Lactobacillus rhamnosus (23). In Lactococcus lactis, an antisense strategy was used to prevent proliferation of four phages (24). More recently, Oddone and collaborators adapted the nisin-controlled expression (NICE) system to express asRNA targeting the clpP protease gene in L. lactis (25). Several strategies can be considered to develop antisense RNA attenuation. Antisense RNA can be designed to target the entire open reading frame (ORF) of the gene, complementary to the mRNA (23–25). The ribosome binding site (RBS) or a ribosome target at a sequence nearby can also constitute an antisense strategy (21, 26). In this study, the target for antisense expression, hsp18, was chosen because it is one of the most well-studied hsp genes in O. oeni. This study reports the development of an asRNA strategy in O. oeni to investigate Lo18 function under stress conditions. This approach was completed by developing the first stable and efficient expression vector in O. oeni. We used two targeting strategies: (i) the hsp18 gene was cloned in the reverse orientation under the control of a LAB constitutive promoter to give rise to a nontranslatable double-stranded RNA molecule, and (ii) the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) of hsp18 was cloned in the reverse orientation, complementary to the RBS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Oenococcus oeni strain ATCC BAA-1163 is an acidophilic strain isolated from red wine. O. oeni was grown at 30°C in FT80m medium (pH 5.3) (27). In preparation for the experiments, O. oeni was cultured from glycerol stocks in FT80m medium, which contained 20 μg · ml−1 of vancomycin, 20 μg · ml−1 of lincomycin, and 20 μg · ml−1 of erythromycin when required. For survival tests, cells were used from the O. oeni culture to the end of exponential phase (A600 = 0.8) and then transferred at 48°C or into an acid FT80m medium adjusted to pH 3.5 or pH 3 and incubated at 30°C for 90 min.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| EC101 | JM101[supE thi (lac proAB) F′ traD36 proAB lacIq ZΔM15] with repA from pWV01 integrated in chromosome | Promega (Lyon, France) |

| EcAS18 | EC101 harboring pSIPSYNhsp18-ORF | This study |

| EcAS18-UTR | EC101 harboring pSIPSYNhsp18-5′ UTR | This study |

| Ecsyn | EC101 harboring pSIPSYN | This study |

| Oenococcus oeni strains | ||

| ATCC BAA-1163 | Wild-type strain, Vanr | Laboratory stock |

| OoS18 | ATCC BAA-1163 harboring pSIPSYNAShsp18-ORF | This study |

| OoAS18-UTR | ATCC BAA-1163 harboring pSIPSYNAShsp18-RBS | This study |

| Oosyn | ATCC BAA-1163 harboring pSIPSYN | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGID052 | Eryr Lincor; 3.38-kb HindIII DNA fragment of pLC22R, oriR of pLC22R | 36 |

| pSYNS3 | Eryr Lincor; derived from pGID052, PSYN promoter cloned between SwaI and PvuII sites | This study |

| pSIP409 | Eryr Ori+ Rep256 sppK sppR gusA, under control of PorfX promoter from pSIP401 | 41 |

| pSIPSYN | Eryr Lincor; derived from pSIP409, deletion of sppK, sppR, and gusA, under control of PSYN promoter | This study |

| pSIPSYNAS18 | Eryr Lincor; derived from pSIPSYN, ORFhsp18 in antisense orientation under control of PSYN promoter | This study |

| pSIPSYNAS18-UTR | Eryr Lincor; derived from pSIPSYN, 5′ UTR hsp18 in antisense orientation under control of PSYN promoter | This study |

Vanr, vancomycin resistance; Eryr, erythromycin resistance; Lincor, lincomycin resistance.

Escherichia coli EC101 strain [supE hsd-5 thi Δ(lac-proAB) F′(traD36 proAB+ lacIq lacZΔM15) repA+] was used for cloning and maintenance of plasmids. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with erythromycin (250 μg · ml−1) when necessary.

DNA manipulation and bacterial transformation.

O. oeni genomic DNA was extracted using the InstaGene matrix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). PCR was performed with the Expand high-fidelity PCR system (Roche, Meylan, France). Plasmids from E. coli were prepared with the GeneJET plasmid miniprep kit (Thermo Scientific, Illkirch, France). DNA fragments were purified with the GeneJET PCR purification kit (Thermo Scientific, Illkirch, France). T4 DNA ligase and other restriction endonucleases were purchased from New England BioLabs Inc. (Ipswich, USA). Plasmids and ligation products were transferred by electroporation into E. coli EC101 by the method of Taketo (28). Briefly, cells in early exponential phase (A600 of 0.5) were collected from 500 ml of LB culture, washed twice in 250 ml of ice-cold ultrapure water, and concentrated 100-fold in 2.5 ml of 25% glycerol. Aliquots of 0.1 ml were stored at −80°C. Aliquots of 0.1 ml were mixed on ice with plasmid DNA or ligation mixture and then subjected to an electroporation pulse of 25 μF, 200 Ω, and 12.5 kV/cm, followed by addition of 1 ml of LB medium. Cell suspensions were incubated for 20 min at 37°C, followed by plating of 0.1 ml on solid LB medium containing erythromycin (250 μg.ml−1). Plasmids were transferred by electroporation into O. oeni as previously described by Assad-Garcia et al. (19). Recombinant strains were selected on FT80m plates supplemented with erythromycin, vancomycin, and lincomycin (20 μg · ml−1 each) (19).

Plasmid constructions and cloning strategy.

A synthetic consensus promoter region was designed by aligning the following O. oeni gene promoter sequences: mleR-mleA (accession number X82326) (29), clpX (Y15953) (30), hsp18 (X99468) (8), alsS-alsD (X93091) (31), clpP-clpL (AJ606044) (3), groES (CAI65392) (6), grpE (CAI68011) (6), dnaG (EAV39431.1) (C. Grandvalet, unpublished data; direct submission), and ctsR-clpC (AJ890338.1) (6). Complementary oligonucleotides psynC and psynD (50 mM each) (Table 2) were annealed by heating (95°C, 5 min) and gently cooling (95°C to 20°C), and the DNA duplex was restricted with SwaI and SmaI restriction enzymes and then subcloned between the SwaI and PvuII sites of plasmid pGID052 (32). The resulting plasmid, named pSYNS3 (Table 1), was then used as a DNA matrix for PCR amplification of the promoter region using oligonucleotides olcg302 and olcg305 (Table 2). An RBS was added by insertion in the sequence of primer olcg302. The resulting PCR product, corresponding to a synthetic promoter called PSYN (KT716344) (this work), was finally cloned between the SalI and NcoI sites of plasmid pSIP409, replacing the sakacin P-based inducible expression system with the synthetic consensus promoter to obtain the plasmid pSIPSYN (33).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Gene or targeted region | Primer or probe | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Restriction site or DIG labeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| hsp18 | ASHsp181 | CGTCCCGGGATGGCAAATGAATTAATGGATAGAAATGAT | SmaI |

| ASHsp182 | GGGCCATGGTTATTGGATTTCAATATGATGAGTTTGACT | NcoI | |

| 5′ UTR hsp18 | ASHsp18R | GGGCCCGGGTAAGCGGTATGTAATATCACT | SmaI |

| ASHsp18F | GGGCCATGGCATATCAAATACCTCCTATTAAC | NcoI | |

| Synthetic promoter | psynC | GATCAGCTGCCATGGCTGCAGGGATCCCCGGGTACCTCGAGCTCTGAATTCATTATAGTGATTATTGGTACTAAAGTCAAATTTAAATCCG | |

| psynD | CGGATTTAAATTTGACTTTAGTACCAATAATCACTATAATGAATTCAGAGCTCGAGGTACCCGGGGATCCCTGCAGCCATGGCAGCTGATC | ||

| Olcg305 | CCCGTCGACGCGCAACTGTTGGGAAGGG | SalI | |

| Olcg302 | GGGCCATGGCAAATACCTCCTGATTCATTAATGCAGGGGTAC | NcoI | |

| Olcg303 | CCCAAGCTTGCGCAACTGTTGGGAAGGG | HindIII | |

| mhsp18 target | DIG-mhsp18 probe | CGAACGACATTATTTTTCTTGTCTTTTTCCTCGGCCTTGG | 3′ end-dUTPDig |

| ashsp18 target | DIG-ashsp18 probe | TGAAAACGATAAAGAATACGGCCTGAAAATCGAACTTCCA | 3′ end-dUTPDig |

Restriction sites are underlined, and the RBS is in bold.

Plasmids pSIPSYNAS18-UTR and pSIPSYNAS18 were constructed by inserting the amplified 5′ UTR hsp18 region containing the RBS or the full-length coding sequence of the hsp18 gene, respectively, into the multiple-cloning site of pSIPSYN. The antisense hsp18 gene inserts were amplified by PCR from O. oeni ATCC BAA-1163 genomic DNA using oligonucleotide pairs ASHsp181/ASHsp182 and ASHsp18R/ASHsp18F, respectively (Table 2) and cloned between the NcoI and SmaI restriction sites of pSIPSYN. The resulting plasmids were transferred into O. oeni by electroporation (19). The pSIPSYN vector alone was also introduced into O. oeni as a control. Positive clones were selected on FT80m plates supplemented with erythromycin, vancomycin, and lincomycin (20 μg · ml−1 each). The presence of plasmids was confirmed by colony PCR amplification with specific primer pair Olcg303/Olcg302 or ASHsp181/ASHsp18R (Table 2).

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis.

The plasmid DNA sequences were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing of both strands by Beckman Coulter Genomics (Essex, United Kingdom) using oligonucleotide Olcg303, ASHSP181, or ASHPS18R (Table 2). Nucleotide sequencing results were analyzed using LALIGN software (www.ch.embnet.org/software/LALIGN_form.html).

Total cellular protein extraction and detection by dot blot hybridization.

The cell pellet from 50 ml of culture was suspended in 800 μl of lysis buffer (Tris-HCl [10 mM], NaCl [200 mM], pH 8.8), glass beads (0.5 μm) were added, and cells were lysed by two consecutive 60-s treatments with a Precellys homogenizer (Paris, France) at 6,500 rpm. The suspension was centrifuged at 13,200 × g for 15 min at 4°C to remove intact cells and cellular debris. Supernatants containing total cellular proteins were collected and assayed with the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Protein concentrations were adjusted to 1 μg · μl−1, and 5 μg of from each sample was spotted on a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane activated by a 15-min wash in methanol (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). After drying, the membrane was washed twice in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After saturation in 1× PBS–5% milk and three washes in 1× PBS–0.2% Triton X-100, the membrane was first hybridized with anti-Lo18 antibody solution (antibody serum from rabbit [1:100] in 1× PBS–0.2% Triton X-100–5% milk) for 1 h at room temperature with gentle shaking (8). The membrane was then washed three times in 1× PBS–0.2% Triton X-100 and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody solution (1:5,000 in 1× PBS–0.2% Triton X-100–5% milk) (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Before detection, the membrane was washed in 1× PBS–0.2% Triton X-100 for 15 min and four times for 5 min. Chemiluminescence was detected using the ECL kit (Clarity ECL Western blotting substrate; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Membranes were exposed to Amersham Hyperfilm ECL (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Signal intensity was measured by Image Lab 4.1 (Bio-Rad) to assess the relative quantity of Lo18 protein in each sample. Values are the means of triplicates and were calculated relative to the signal intensity of the control Oosyn strain grown at 30°C, which was arbitrarily set as 100%.

Total RNA extraction and detection by dot blot hybridization.

The cell pellet from 25 ml of culture was suspended in 100 μl of TE buffer (Tris-HCl [10 mM], EDTA [1 mM], pH 8.0) containing 40 mg · ml−1 of lysozyme and incubated for 30 min at 37°C for cell lysis. The RNA was then purified on a NucleoSpin RNA column according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Macherey Nalgene, Hoerdt, France). The RNA samples were then treated with 10 μl of rDNase (Macherey Nalgene, Hoerdt, France) at 37°C for 1 h, followed by purification on NucleoSpin RNA with elution in a final volume of 20 μl. The absence of genomic DNA was tested by PCR amplification using universal bacterial primers for the 16S rRNA gene (27F [5′-AGAGTTTGATC[C/A]TGGCTCAG] and 1492R [5′-TACGG[A/T/C]TACCTTGTTACGACTT]) (34). Then, 10 μg of purified total RNA from each sample was loaded on positively charged nylon membranes (Roche, Laval, Québec, Canada). Oligonucleotide probes were purchased 3′ end labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) dideoxy-UTP (Eurogentec, Liège, Belgium). After prehybridization for 2 h at 50°C in Dig EasyHyb solution (5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 0.1% N-laurylsarcosine, 0.02% SDS, 2% blocking solution), the probe (10 pmol) was added and hybridization was carried out 15 h at 50°C. After washing the membranes twice for 5 min in 2× SSC–0.1% SDS at room temperature, two 15-min washes were carried out in 0.5× SSC–0.1% SDS at 50°C. To bind the DIG-labeled probes, the membrane was incubated at 25°C for 30 min with antibody solution (alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antidigoxigenin antibody [1:10,000] in blocking solution). Detection of chemiluminescence was performed with disodium 3-(4-methoxyspiro{1,2-dioxetane-M,2′-(5′-chloro)tricyclo[3.3.1.13,7]decan}-4-yl phenyl phosphate) (CSPD) as the chemiluminescent substrate according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Roche). Membranes were exposed to Kodak BioMax MS film (Kodak, Mandel Scientific, Guelph, Canada).

Fluorescence anisotropy measurements.

The method for membrane fluidity assays was previously validated in our laboratory (35). Cell energization with a 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES)-glucose buffer (50 mM MES, 10 mM glucose, KOH buffer [pH 5.5]) was necessary to prevent a decrease of membrane fluidity caused by bacterial death independent of the type of stress. Exponentially growing O. oeni cells (20-ml culture at an optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.8) were harvested by centrifugation at 6,300 × g for 10 min and washed once in 20 ml of MES-glucose. Pelleted cells were suspended in the same buffer, and the OD600 was adjusted to 0.6 for each sample. Hydrophobic 1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH) (Molecular Probes) was used as a probe, and fluorescence anisotropy measurements were performed immediately on the prepared samples as follows: DPH solution (3 μM) was added to the cell suspension, and samples were then placed in the stirred and thermostated spectrofluorometer cuvette holder (Fluorolog-3; Jobin Yvon, Inc., USA). Anisotropy values were calculated as described by Shinitzky and Barenholz (36). To ensure optimal anisotropy determinations, the probe was stabilized at 30°C for 5 min before shock. Ethanol shock was applied to the labeled cells directly during the measurement. Excitation and emission wavelengths were 352 and 402 nm, respectively. Anisotropy values were automatically calculated by the spectrofluorometer as described by Shinitzky and Barenholz (36) as previously reported (4, 35). Fluorescence anisotropy (inversely proportional to membrane fluidity) was measured every 7 s for 45 min. Each experiment was performed at least two times from independent cultures.

Statistical analysis.

The significance of the differences among fluorescence anisotropy values and survival tests was determined with a two-tailed Student t test. The confidence interval for a difference in the means was set at 95% (P ≤ 0.05) for all comparisons.

RESULTS

Cloning strategy: construction of expression vector to produce hsp18 antisense RNAs.

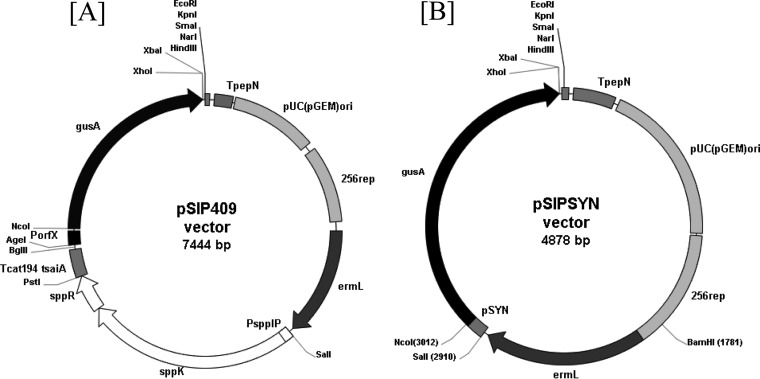

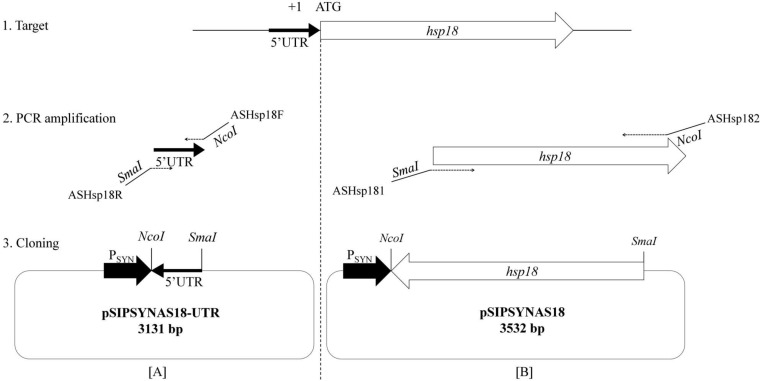

The pSIPSYN vector constructed in this work derived from the Gram-negative/Gram-positive shuttle expression vector pSIP409 (Fig. 1; Table 1). Previous work has shown that the sakacin P-based vector pSIP409 was the most promising for inducible expression of gusA in lactobacilli such as Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus sakei (33). Thus, the pSIP409 vector was used as a starting point for studying gene expression in LAB. This vector is a low-copy-number plasmid and stems from the pSIP vector series (33). Previously, our laboratory developed an expression vector in O. oeni called pGID052. This vector is a 5.7-kb Gram-positive/Gram-negative shuttle vector which contained a pLC22R region required for replication, measuring 3.38 kb, from Leuconostoc citreum and a polylinker from the pUC18 vector. However, this vector does not have any transcription signals and has a substantial size, limiting transformation efficiency. Therefore, we developed a new expression vector from pSIP409 adapted to O. oeni. Inducible expression systems, including the sppR, sppK, and sppIP genes and PorfX promoter, appear to be nonfunctional in O. oeni (data not shown). Consequently, the new vector was derived from pSIP409 by removing and replacing the sakacin P-inducible expression system with a synthetic promoter designed from alignment of promoter sequences from O. oeni genes (see Materials and Methods). The resulting plasmid was named pSIPSYN (Fig. 1B). Using the pSIPSYN vector, two different antisense RNAs of hsp18 (asRNA-hsp18) were produced to modulate hsp18 gene expression and investigate the knockdown of Lo18 protein levels (Fig. 2). First, the noncoding RNA of the hsp18 gene 5′ UTR was designed by cloning the 5′ UTR in antisense orientation to yield pSIPSYNAS18-UTR (Fig. 1B and 2A). Second, the full-length ashsp18 construction was designed by inserting the open reading frame of the hsp18 gene in antisense orientation to obtain plasmid pSIPSYNAS18 (Fig. 1B and 2B). Recombinant vectors, including pSIPSYN, were transferred to O. oeni strain ATCC BAA-1163, and recombinant strains were designated Oosyn, OoAS18-UTR, and OoAS18 for strains carrying plasmids pSIPSYN, pSIPSYNAS18-UTR, and pSIPSYNAS18, respectively.

FIG 1.

Restriction map of plasmids pSIP409 and pSIPSYN. (A) pSIP409. pSIP409 is a Gram-positive/Gram-negative shuttle vector with the Gram-negative replication origin pUC(GEM)ori, Gram-positive origin of replication 256rep, erythromycin selection (ermL), and expression of the reporter gene encoding β-glucuronidase (gusA) inducible by addition of a 19-amino-acid peptide pheromone (SppIP, MAGNSSNFIHKIKQIFTHR). (B) pSIPSYN. pSIPSYN is a derivative of pSIP409 with removal of the inducible expression system (sppK, sppR) and replacement of the PorfX inducible promoter with a synthetic promoter from O. oeni strain ATCC BAA-1163 upstream of the gene gusA between the SalI and NcoI restriction sites.

FIG 2.

Cloning strategy for antisense hsp18 expressed under control of the PSYN promoter. Primer sequences are listed in Table 2. (A) Cloning strategy targeting the 5′ UTR of hsp18. (B) Cloning strategy targeting the full-length hsp18 gene.

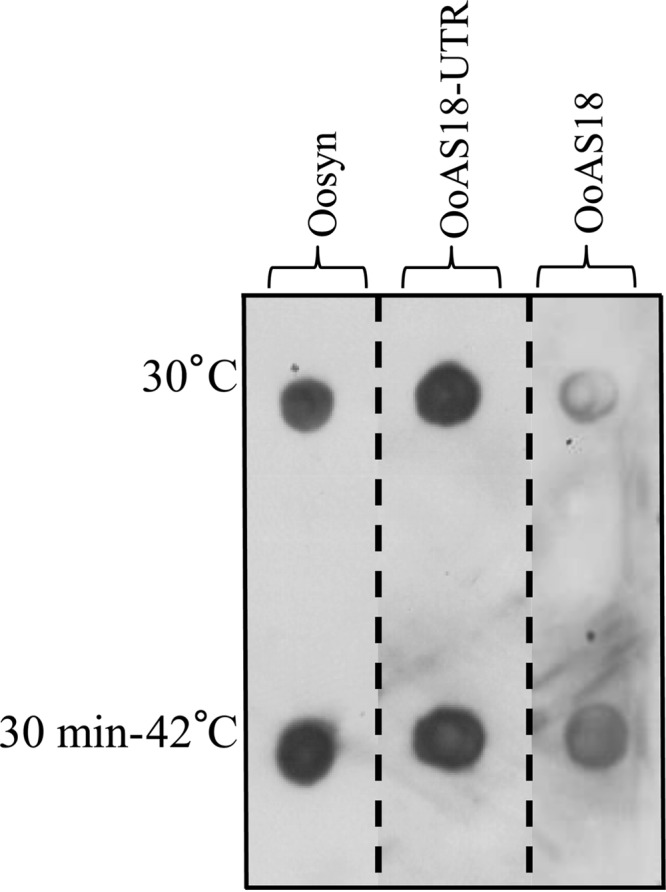

Detection of Lo18 by Western blotting: validation of asRNA function.

For each strain and condition, 5 μg of protein was deposited on membranes and revealed with polyclonal antibodies directed against Lo18. Relative quantities of Lo18 protein were calculated relative to the signal intensity of strain Oosyn grown at 30°C, which was arbitrarily designated 100%. Values are the means of duplicates. Between spot signals of Oosyn, the reference strain, and OoAS18-UTR, no differences in relative protein quantities were observed with (263% and 244%) or without (100% and 114%) thermal shock, indicating that there is no difference in the protein level when the 5′ UTR of the hsp18 gene is targeted by asRNA (Fig. 3). In contrast, the relative quantity of Lo18 in the recombinant strain OoAS18 at 30°C is 32%, indicating that the protein level of Lo18 is lowered 3.1-fold when the whole gene sequence is targeted by asRNA. After a heat shock, the same observation was made, with a 59% relative quantity of Lo18 protein in strain OoAS18 and 263% in strain Oosyn, meaning a 4.5-fold decrease. Having observed a 3.1-fold decrease at 30°C and a 4.5-fold decrease after a heat shock in Lo18 levels by expressing asRNA targeting the whole mRNA of hsp18 and no differences in the Lo18 protein level by targeting the 5′ UTR of hsp18, we focused our research on strain OoAS18.

FIG 3.

Immunodetection of Lo18 in the O. oeni recombinant strains. Strains carrying pSIPSYN (Oosyn), pSINSYNAS18-UTR (OoAS18-UTR), or pSIPSYNAS18 (OoAS18) vectors were cultivated at 30°C in FT80m medium until the end of the exponential growth phase. Total cellular proteins were extracted immediately (30°C) or following a thermal treatment (30 min at 42°C). For each strain and each condition, 5 μg of protein was loaded on a PVDF membrane activated with methanol. After drying the membrane, the O. oeni protein Lo18 was detected by immunodetection with polyclonal antibodies directed against Lo18 and anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with peroxidase. Signal intensity was measured by Image Lab 4.1 (Bio-Rad) to assess relative quantities of the Lo18 protein in each spot.

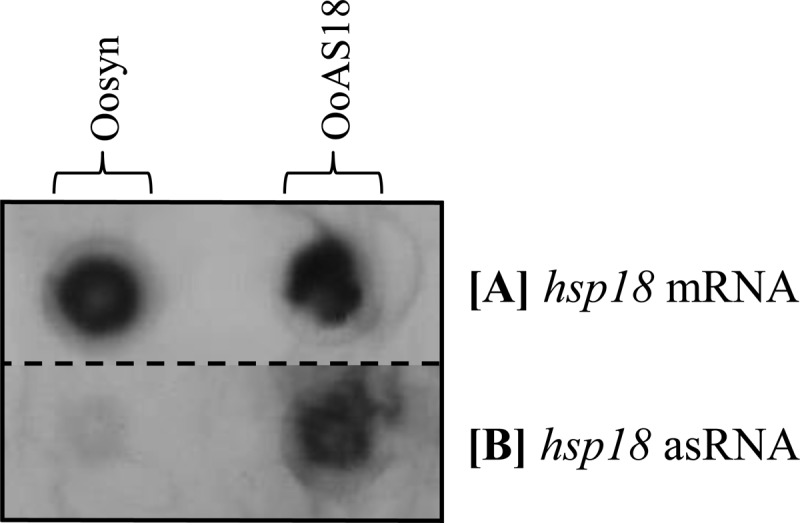

Detection of hsp18 asRNA and mRNA by Northern blotting: validation of asRNA expression.

For each strain and each condition, 10 μg of RNA was deposited on a nylon membrane. Digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes were used to detect hsp18 mRNA and hsp18 asRNA (Fig. 4). A signal corresponding to hsp18 mRNA was detected in the Oosyn and OoAS18 strains, and no difference in hsp18 mRNA levels was observed between the two strains (Fig. 4A). In contrast, a signal corresponding to hsp18 asRNA was detected in strain OoAS18 but not in Oosyn (Fig. 4B). This observation validates the pSIPSYN vector for expression of asRNA and target genes of interest. Based on this observation, we investigated the physiological effects of attenuation of hsp18 expression in O. oeni.

FIG 4.

Detection of hsp18 asRNA and hsp18 mRNA in the O. oeni recombinant strains. Dot blot hybridization with oligonucleotide probe DIG-mhsp18 complementary to mRNA (A) or oligonucleotide probe DIG-ashsp18 complementary to antisense RNA (B) was performed. Recombinant strains carrying the native plasmid (Oosyn) or carrying the plasmid expressing hsp18 asRNA (OoAS18) were cultivated at 30°C in FT80m medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics until the end of the exponential growth phase. Total RNA was isolated, and 5 μg of RNA from each strain and each condition was loaded on a nitrocellulose membrane.

What is the effect of lower Lo18 levels on O. oeni survival under stress conditions?

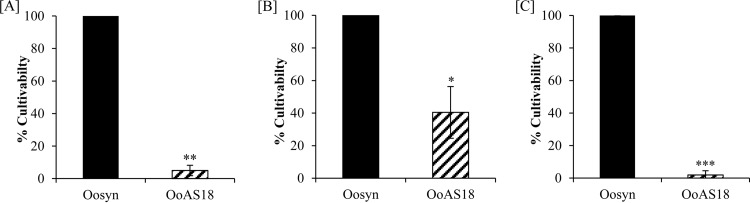

To address the in vivo function of hsp18, survival tests during stress treatments were performed on recombinant strains Oosyn and OoAS18. Based on in vitro studies of Lo18, we focused our physiological study on stresses causing membrane fluidity changes or protein aggregation, such as heat shock or acid shock. Cells were cultivated under optimal growth conditions to the middle of the exponential growth phase and then subjected to different stress treatments. Following CFU counts on agar plates, the cultivability rate was calculated and normalized to that of the reference strain Oosyn (Fig. 5). After a heat shock or acid shock induced by switching the temperature from 30°C to 48°C or the medium pH from 5.3 to 3 or 3.5 for 90 min, no loss of cultivability of strain Oosyn was observed. In contrast, strain OoAS18 lost 95.0% of its population (Fig. 5A). After a pH 3.5 acid shock, the attenuation of Lo18 levels induced a 59.6% loss of cultivability of strain OoAS18 (Fig. 5B). The loss of cultivability was higher when the acid shock was increased to pH 3, with strain OoAS18 losing 98.1% viability (Fig. 5C).

FIG 5.

Cultivability tests after stress treatments. Recombinant strains carrying native plasmid (Oosyn) or the plasmid expressing hsp18 asRNA (OoAS18) were grown at 30°C in FT80m medium until the end of the exponential phase (A600 = 0.8). Cultures were incubated at 48°C (A), or cells were transferred into FT80m medium adjusted to pH 3.5 (B) or pH 3 (C) and incubated at 30°C for 90 min. Bacterial cultivability was estimated (CFU · ml−1). Significant differences are based on unilateral and paired t tests. ***, P < 0.0005; **, P < 0.005; *, P < 0.05.

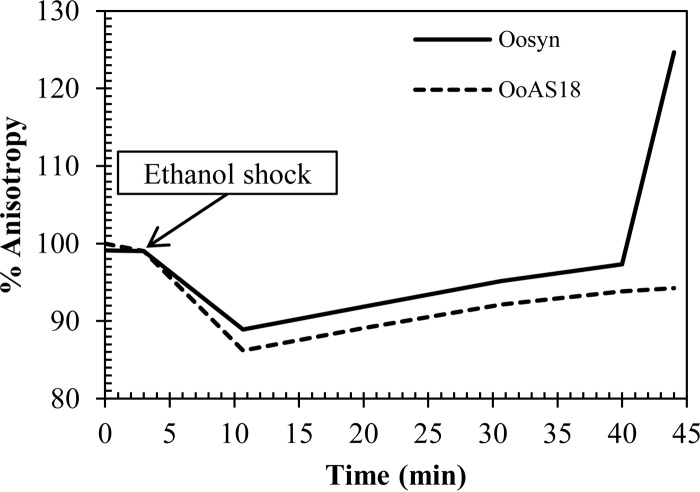

Effect of ethanol shock on membrane fluidity determined by fluorescence anisotropy.

Ethanol shock (12 [vol/vol]) gave rise to a 15% decrease of the initial anisotropy value, indicating an instantaneous increase in membrane fluidity (Fig. 6). The fluidifying effect of ethanol was transient. For Oosyn, the reference strain, membrane fluidity returned to its initial level 40 min after a 12% ethanol shock. After 40 min, the anisotropy value was higher than the initial level, indicating a membrane rigidification.

FIG 6.

Evolution of membrane fluidity (anisotropy percentage) in O. oeni cells during ethanol shock (30°C, pH 5.3, and 12% [vol/vol] ethanol). The reference strain Oosyn (solid line) and the recombinant strain OoAS18 (dashed line) were grown at 30°C in FT80m pH 5.3 medium until the end of the exponential phase (A600 = 0.8). After an MES-glucose buffer wash, the OD600 was adjusted to 0.6 for each sample. Results are expressed as anisotropy percentage as a function of time.

The reference strain recovered its initial membrane fluidity with a speed of 0.31% anisotropy unit · min−1. The recombinant strain OoAS18 was able to counteract the effect of ethanol shock at a speed comparable to that of the reference strain. Nevertheless, membrane fluidity did not return to the initial level and remained at 96% of the initial value, with no membrane rigidification. The kinetics of membrane fluidity restoration differed significantly between the reference strain Oosyn and the recombinant strain OoAS18.

DISCUSSION

Natural control of gene expression by the antisense strategy has been characterized in many bacteria and eukaryotes (37, 38). This regulatory system, by base pairing using small RNA, has been applied to the investigation of gene function in eukaryotes and is used more and more to study gene function or to modulate phage and plasmid replication (23–25, 39–41). Due to the lack of genetic tools for directed mutagenesis in O. oeni, the asRNA production approach is presently a highly promising approach to investigate the stress response in this bacterium. By targeting hsp18 for knockdown, we undertook the first in vivo approach with the aim of studying the only described O. oeni sHSP. The expression of a complementary asRNA targeting the full-length hsp18 gene reduced the levels of Lo18 3.1-fold during growth at 30°C and 4.5-fold after a heat shock at 42°C. In contrast, the targeting by asRNA of the 5′ UTR of the hsp18 gene was not effective. This observation is in agreement with studies performed in LAB using the antisense strategy to target the whole sequences of genes (23, 25, 42, 43). Indeed, the expression of antisense RNA covering the whole gene sequence appeared to be the most effective strategy to inhibit gene expression (43). Moreover, interestingly, reported effective antisense RNA approaches in LAB used 500-bp-length asRNAs, as in our study (23, 25, 43). The 68% decrease in Lo18 protein level at 30°C validated the usefulness and efficiency of the pSIPSYN vector to produce asRNA targeting mRNA and thus to attenuate gene expression in O. oeni.

Our Northern dot-blotting analysis allowed validation of the new expression vector by highlighting the presence of hsp18 asRNA. Even though quantities of hsp18 transcripts were not affected by antisense hsp18 expression, the Lo18 protein level and the survival capability of O. oeni under stress conditions were clearly affected. This result seems to indicate a posttranscriptional action of hsp18 antisense RNA expression, probably by preventing translation through steric hindrance. The 68% decrease in Lo18 protein detected by Western blotting validates this hypothesis. For asRNA-based regulatory techniques, the physical interaction of asRNA with the targeted mRNA is an essential condition (44). However, the interaction between asRNA and its target does not necessarily lead to the rapid degradation of the double-stranded RNA duplex. Thus, hybridization by base paring of asRNA with its target can cause the generation of a processing site leading to a translationally inactive or a stabilized form of the targeted mRNA (44).While it is difficult to conclude that the duplex asRNA-mRNA is not targeted by a degradation system, this hypothesis could explain why mRNA levels were only slightly affected in strain OoAS18.

Lo18 is the sole sHSP described in O. oeni and is encoded by the best-characterized in vitro hsp gene of O. oeni. Therefore, we selected it as a primary target for antisense RNA in order to unravel its potential in vivo role. Expression of the hsp18 gene is controlled by CtsR, the master transcriptional regulator of hsp gene expression in O. oeni (6). Lo18 synthesis is induced during the stationary growth phase and is also induced in response to various stresses, such as ethanol, heat, and acid stress (10, 18). Thus, Lo18 seems to have a cytoplasmic localization, which may allow it to exert a ATP-independent molecular chaperone activity (18). During our investigation of the potential of the asRNA approach, we have demonstrated that asRNA expression under the control of the synthetic promoter gave rise to phenotypic differences between the reference strain Oosyn and the recombinant strain OoAS18. This phenotypic analysis highlighted the role of Lo18 in counteracting stress effects on O. oeni whole cells. Thus, the attenuation of hsp18 expression led to a significant loss of viability after heat shock or acid shock. As previously shown in E. coli using a heterologous system (45), our findings finally confirm in O. oeni the involvement of Lo18 in the acidophilic capability of bacteria. Indeed, the attenuation of Lo18 levels reduces the stress response ability of O. oeni under the acid stress conditions tested. Moreover, Lo18 had an effect on the ability of cells to counteract heat stress. This observation confirms the in vivo implication of Lo18 in high-temperature thermoprotection and acid tolerance of stressed cells. The implications of sHSP have been previously explored in Lactobacillus plantarum, a wine-related LAB (46). Three small heat shock protein-encoding genes have been previously reported in L. plantarum strain WCFS1, hsp18.5, hsp18.55, and hsp19.3 (47, 48). The deletion of the hsp18.55 gene affects cell recovery following short intense heat stress, as well as cell morphology and membrane fluidity of L. plantarum cells (46). In addition, the hsp18 gene of Streptomyces albus encodes an sHSP that plays a role in thermotolerance (49), and HSP17 of Synechocystis spp. is essential for tolerance to high temperatures (49, 50). In O. oeni, Lo18 was shown to be a membrane-associated sHSP displaying a possible lipochaperone activity (5, 8, 17, 18).

Indeed, after addition of benzyl alcohol, a membrane fluidifier, Lo18 was found at the periphery of the membrane, suggesting a role in membrane stabilization during environmental stress and a potential molecular lipochaperone activity (5). Therefore, we assessed the lipochaperone activity of Lo18 by using fluorescence anisotropy analysis with a DPH probe, a method previously used in O. oeni (35). Attenuation of hsp18 gene expression affects the membrane fluidity of O. oeni recombinant strains, which immediately decreases after ethanol shock. Our findings demonstrate involvement of Lo18 in modulation of membrane fluidification caused by ethanol. These observations are consistent with previous studies in O. oeni during combined and single cold, acid, and ethanol shocks, highlighting a 15% decrease of anisotropy (4, 11, 35). After an ethanol shock, the reference strain Oosyn managed to restore its initial membrane fluidity in 45 min, while the OoAS18 strain failed to restore membrane fluidity to its initial value. Therefore, the attenuation of Lo18 protein level by asRNA targeting prevents the full restoration of membrane fluidity, which remained at 96% of the initial value. The anisotropy results were highly similar to those obtained by Török and coworkers in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803, where deletion of a small heat shock protein-encoding gene (hsp17) was characterized (13). Differences in membrane fluidity were detected when the fluorescence anisotropies of the wild-type and the hsp17 deletion strains were compared (13). The deletion of hsp17 showed that membrane fluidity of hsp17-deficient cells was remarkably higher than that of the parental cells suggesting that HSP17 may function primarily as a membrane-stabilizing factor. Our results clearly illustrate the membrane-protective role of sHSP during ethanol shock. In fact, our study using the asRNA strategy shows that Lo18 is required for O. oeni survival under environmental stress conditions causing fluidification of the membrane and aggregation of cellular proteins.

In summary, our findings indicate that knockdown by the antisense RNA system is presently the most relevant strategy to understand the role of hsp18. Moreover, besides technical restrictions, permanent knockout of hsp18 by directed mutagenesis may not be achievable due to the possibly lethal character of this mutation. We have reported an efficient technique available to investigate the function of stress genes in O. oeni and thus to study the stress response ability of this bacterium.

In addition, we can conclude that the pSIPSYN vector designed for this work is an efficient expression vector used to produce asRNA. This new expression vector opens two main perspectives in order to pursue the study of stress response mechanisms in O. oeni. This could enable the opening of a real in vivo investigation in O. oeni. Indeed, the synthetic promoter of the pSIPSYN vector enables constitutive expression in O. oeni, which could be a dual potential use of expressing candidate genes or targeting other genes of interest with the antisense approach. Thus, the pSIPSYN vector has already been exploited for gene overexpression to study the impact of O. oeni esterase genes on the aromatic quality of wine, opening the doors for wine-associated LAB engineering (M. Darsonval, unpublished data). Regarding the targeting of other genes by the antisense RNA approach, Sturino and Klaenhammer have already stated that the efficiency of the asRNA approach seems to be highly variable and dependent on the choice of the candidate gene targeted for this purpose (24, 43). These observations imply that some key criteria are needed to select an ideal asRNA target. Thus, the asRNA approach will certainly need further adjustments according to the targeted gene. To further study the stress response in O. oeni, we plan to target the ctsR gene, encoding the unique regulator of stress response gene expression identified in O. oeni, which should be ideally suited for this strategy (6).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Magali Maitre for her technical assistance with anisotropy measurements. We are grateful to Lars Axelsson for providing the pSIP409 vector.

This work was supported by the Ministère de la Recherche et de l'Enseignement Supérieur (France).

REFERENCES

- 1.Lonvaud-Funel A. 1999. Lactic acid bacteria in the quality improvement and depreciation of wine. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 76:317–331. doi: 10.1023/A:1002088931106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartowsky EJ, Borneman AR. 2011. Genomic variations of Oenococcus oeni strains and the potential to impact on malolactic fermentation and aroma compounds in wine. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 92:441–447. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3546-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beltramo C, Grandvalet C, Pierre F, Guzzo J. 2004. Evidence for multiple levels of regulation of Oenococcus oeni clpP-clpL locus expression in response to stress. J Bacteriol 186:2200–2205. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.7.2200-2205.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu-Ky S, Tourdot-Maréchal R, Maréchal P-A, Guzzo J. 2005. Combined cold, acid, ethanol shocks in Oenococcus oeni: effects on membrane fluidity and cell viability. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1717:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coucheney F, Gal L, Beney L, Lherminier J, Gervais P, Guzzo J. 2005. A small HSP, Lo18, interacts with the cell membrane and modulates lipid physical state under heat shock conditions in a lactic acid bacterium. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1720:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grandvalet C, Coucheney F, Beltramo C, Guzzo J. 2005. CtsR is the master regulator of stress response gene expression in Oenococcus oeni.. J Bacteriol 187:5614–5623. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.16.5614-5623.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grandvalet C, Assad-García JS, Chu-Ky S, Tollot M, Guzzo J, Gresti J, Tourdot-Maréchal R. 2008. Changes in membrane lipid composition in ethanol- and acid-adapted Oenococcus oeni cells: characterization of the cfa gene by heterologous complementation. Microbiology 154:2611–2619. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/016238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jobin MP, Delmas F, Garmyn D, Diviès C, Guzzo J. 1997. Molecular characterization of the gene encoding an 18-kilodalton small heat shock protein associated with the membrane of Leuconostoc oenos.. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:609–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzzo J, Cavin JF, Diviès C. 1994. Induction of stress proteins in Leuconostoc oenos to perform direct inoculation of wine. Biotechnol Lett 16:1189–1194. doi: 10.1007/BF01020849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guzzo J, Delmas F, Pierre F, Jobin M-P, Samyn B, Van Beeumen J, Cavin J-F, Diviès C. 1997. A small heat shock protein from Leuconostoc oenos induced by multiple stresses and during stationary growth phase. Lett Appl Microbiol 24:393–396. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.1997.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maitre M, Weidmann S, Dubois-Brissonnet F, David V, Covès J, Guzzo J. 2014. Adaptation of the wine bacterium Oenococcus oeni to ethanol stress: role of the small heat shock protein Lo18 in membrane integrity. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:2973–2980. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04178-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Török Z, Horváth I, Goloubinoff P, Kovács E, Glatz A, Balogh G, Vígh L. 1997. Evidence for a lipochaperonin: association of active protein folding GroESL oligomers with lipids can stabilize membranes under heat shock conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:2192–2197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Török Z, Goloubinoff P, Horváth I, Tsvetkova NM, Glatz A, Balogh G, Varvasovszki V, Los DA, Vierling E, Crowe JH, Vígh L. 2001. Synechocystis HSP17 is an amphitropic protein that stabilizes heat-stressed membranes and binds denatured proteins for subsequent chaperone-mediated refolding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:3098–3103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051619498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narberhaus F. 2002. α-Crystallin-type heat shock proteins: socializing minichaperones in the context of a multichaperone network. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 66:64–93. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.1.64-93.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamoto H, Vígh L. 2007. The small heat shock proteins and their clients. Cell Mol Life Sci 64:294–306. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6321-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weidmann S, Rieu A, Rega M, Coucheney F, Guzzo J. 2010. Distinct amino acids of the Oenococcus oeni small heat shock protein Lo18 are essential for damaged protein protection and membrane stabilization. FEMS Microbiol Lett 309:8–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.01999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maitre M, Weidmann S, Rieu A, Fenel D, Schoehn G, Ebel C, Coves J, Guzzo J. 2012. The oligomer plasticity of the small heat-shock protein Lo18 from Oenococcus oeni influences its role in both membrane stabilization and protein protection. Biochem J 444:97–104. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delmas F, Pierre F, Coucheney F, Diviès C, Guzzo J. 2001. Biochemical and physiological studies of the small heat shock protein Lo18 from the lactic acid bacterium Oenococcus oeni.. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 3:601–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Assad-García J, Bonnin-Jusserand M, Garmyn D, Guzzo J, Alexandre H, Grandvalet C. 2008. An improved protocol for electroporation of Oenococcus oeni ATCC BAA-1163 using ethanol as immediate membrane fluidizing agent. Lett Appl Microbiol 47:333–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dicks LMT. 1994. Transformation of Leuconostoc oenos by electroporation. Biotechnol Tech 8:901–904. doi: 10.1007/BF02447736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Good L. 2003. Translation repression by antisense sequences. Cell Mol Life Sci 60:854–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasmussen LCV, Sperling-Petersen HU, Mortensen KK. 2007. Hitting bacteria at the heart of the central dogma: sequence-specific inhibition. Microb Cell Fact 6:24. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouazzaoui K, LaPointe G. 2006. Use of antisense RNA to modulate glycosyltransferase gene expression and exopolysaccharide molecular mass in Lactobacillus rhamnosus.. J Microbiol Methods 65:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGrath S, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. 2001. Improvement and optimization of two engineered phage resistance mechanisms in Lactococcus lactis.. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:608–616. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.608-616.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oddone GM, Mills DA, Block DE. 2009. Dual inducible expression of recombinant GFP and targeted antisense RNA in Lactococcus lactis.. Plasmid 62:108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engdahl HM, Lindell M, Wagner EGH. 2001. Introduction of an RNA stability element at the 5′-end of an antisense RNA cassette increases the inhibition of target RNA translation. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev 11:29–40. doi: 10.1089/108729001750072100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cavin JF, Prevost H, Lin J, Schmitt P, Diviès C. 1989. Medium for screening Leuconostoc oenos strains defective in malolactic fermentation. Appl Environ Microbiol 55:751–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taketo A. 1988. DNA transfection of Escherichia coli by electroporation. Biochim Biophys Acta 949:318–324. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(88)90158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labarre C, Diviès C, Guzzo J. 1996. Genetic organization of the mle locus and identification of a mleR-like gene from Leuconostoc oenos.. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:4493–4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jobin M-P, Garmyn D, Diviès C, Guzzo J. 1999. The Oenococcus oeni clpX homologue is a heat shock gene preferentially expressed in exponential growth phase. J Bacteriol 181:6634–6641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garmyn D, Monnet C, Martineau B, Guzzo J, Cavin J-F, Diviès C. 1996. Cloning and sequencing of the gene encoding α-acetolactate decarboxylase from Leuconostoc oenos.. FEMS Microbiol Lett 145:445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beltramo C, Oraby M, Bourel G, Garmyn D, Guzzo J. 2004. A new vector, pGID052, for genetic transfer in Oenococcus oeni.. FEMS Microbiol Lett 236:53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2004.tb09626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sørvig E, Mathiesen G, Naterstad K, Eijsink VGH, Axelsson L. 2005. High-level, inducible gene expression in Lactobacillus sakei and Lactobacillus plantarum using versatile expression vectors. Microbiology 151:2439–2449. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rousseaux S, Hartmann A, Soulas G. 2001. Isolation and characterisation of new Gram-negative and Gram-positive atrazine degrading bacteria from different French soils. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 36:211–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2001.tb00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tourdot-Maréchal R, Gaboriau D, Beney L, Diviès C. 2000. Membrane fluidity of stressed cells of Oenococcus oeni.. Int J Food Microbiol 55:269–273. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shinitzky M, Barenholz Y. 1978. Fluidity parameters of lipid regions determined by fluorescence polarization. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Biomembr 515:367–394. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(78)90010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGarry TJ, Lindquist S. 1986. Inhibition of heat shock protein synthesis by heat-inducible antisense RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83:399–403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simons RW, Kleckner N. 1988. Biological regulation by antisense RNA in prokaryotes. Annu Rev Genet 22:567–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.003031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ji J, Wernli M, Klimkait T, Erb P. 2003. Enhanced gene silencing by the application of multiple specific small interfering RNAs. FEBS Lett 552:247–252. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00893-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Krol AR, Mol JN, Stuitje AR. 1988. Antisense genes in plants: an overview. Gene 72:45–50. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parish T, Stoker NG. 1997. Development and use of a conditional antisense mutagenesis system in mycobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett 154:151–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim SG, Batt CA. 1991. Antisense mRNA-mediated bacteriophage resistance in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol 57:1109–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sturino JM, Klaenhammer TR. 2004. Antisense RNA targeting of primase interferes with bacteriophage replication in Streptococcus thermophilus.. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:1735–1743. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1735-1743.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Georg J, Hess WR. 2011. cis-Antisense RNA, another level of gene regulation in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 75:286–300. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00032-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morel F, Delmas F, Jobin M-P, Diviès C, Guzzo J. 2001. Improved acid tolerance of a recombinant strain of Escherichia coli expressing genes from the acidophilic bacterium Oenococcus oeni.. Lett Appl Microbiol 33:126–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2001.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Capozzi V, Weidmann S, Fiocco D, Rieu A, Hols P, Guzzo J, Spano G. 2011. Inactivation of a small heat shock protein affects cell morphology and membrane fluidity in Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Res Microbiol 162:419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spano G, Capozzi V, Vernile A, Massa S. 2004. Cloning, molecular characterization and expression analysis of two small heat shock genes isolated from wine Lactobacillus plantarum.. J Appl Microbiol 97:774–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spano G, Beneduce L, Perrotta C, Massa S. 2005. Cloning and characterization of the hsp18.55 gene, a new member of the small heat shock gene family isolated from wine Lactobacillus plantarum.. Res Microbiol 156:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Servant P, Mazodier P. 1996. Heat induction of hsp18 gene expression in Streptomyces albus G: transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation. J Bacteriol 178:7031–7036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsvetkova NM, Horváth I, Török Z, Wolkers WF, Balogi Z, Shigapova N, Crowe LM, Tablin F, Vierling E, Crowe JH, Vígh L. 2002. Small heat-shock proteins regulate membrane lipid polymorphism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:13504–13509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192468399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]