ABSTRACT

Broadly reactive antibodies targeting the conserved hemagglutinin (HA) stalk region are elicited following sequential infection or vaccination with influenza viruses belonging to divergent subtypes and/or expressing antigenically distinct HA globular head domains. Here, we demonstrate, through the use of novel chimeric HA proteins and competitive binding assays, that sequential infection of ferrets with antigenically distinct seasonal H1N1 (sH1N1) influenza virus isolates induced an HA stalk-specific antibody response. Additionally, stalk-specific antibody titers were boosted following sequential infection with antigenically distinct sH1N1 isolates in spite of preexisting, cross-reactive, HA-specific antibody titers. Despite a decline in stalk-specific serum antibody titers, sequential sH1N1 influenza virus-infected ferrets were protected from challenge with a novel H1N1 influenza virus (A/California/07/2009), and these ferrets poorly transmitted the virus to naive contacts. Collectively, these findings indicate that HA stalk-specific antibodies are commonly elicited in ferrets following sequential infection with antigenically distinct sH1N1 influenza virus isolates lacking HA receptor-binding site cross-reactivity and can protect ferrets against a pathogenic novel H1N1 virus.

IMPORTANCE The influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) is a major target of the humoral immune response following infection and/or seasonal vaccination. While antibodies targeting the receptor-binding pocket of HA possess strong neutralization capacities, these antibodies are largely strain specific and do not confer protection against antigenic drift variant or novel HA subtype-expressing viruses. In contrast, antibodies targeting the conserved stalk region of HA exhibit broader reactivity among viruses within and among influenza virus subtypes. Here, we show that sequential infection of ferrets with antigenically distinct seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses boosts the antibody responses directed at the HA stalk region. Moreover, ferrets possessing HA stalk-specific antibody were protected against novel H1N1 virus infection and did not transmit the virus to naive contacts.

INTRODUCTION

The influenza virus is highly contagious and causes an acute respiratory illness, with seasonal epidemics in the human population. Despite global vaccination efforts, influenza remains a major medical issue and is responsible for substantial morbidity and mortality annually. It is estimated that 5 to 20% of the people in the United States contract influenza virus annually, and more than 200,000 people require hospitalization due to influenza-related complications (according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA [http://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/disease.htm; accessed 1 September 2015]). The young, the elderly, pregnant females, and those with certain medical conditions are at an increased risk for influenza-associated complications.

Current vaccination approaches primarily rely on the induction of antibodies recognizing hemagglutinin (HA) (1). The HA glycoprotein is expressed as a trimeric complex of identical subunits on the surface of influenza virus virions. HA mediates virus attachment and subsequent membrane fusion with target cells (2, 3). Individual HA monomers can be further segregated into the membrane-distal globular head and membrane-proximal stalk domains. The globular head encodes the receptor-binding site (RBS), and the stalk domain encodes the fusion peptide (2).

Antibodies directed against HA and, more specifically, to epitopes in close proximity to the RBS within the globular head region are elicited following infection or vaccination (4). These antibodies possess a potent neutralization capacity through the ability to interfere with viral attachment to target cells and are readily detected using a hemagglutinin inhibition (HAI) assay (3, 5). While antibodies with HAI activity can prevent influenza virus infection, they are largely strain specific. Accumulation of point mutations within the globular head region of HA, termed antigenic drift, generates viral escape variants and often leads to evasion of preexisting immunity (5–7). Moreover, antigenic drift necessitates frequent reformulation of the seasonal vaccine, and this process is both expensive and time-consuming.

The globular head domain of HA is highly variable between influenza virus subtypes. In contrast, the membrane-proximal stalk domain of HA is well conserved among group 1 and group 2 influenza A viruses (8, 9). In recent years, a growing collection of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) that target the conserved stalk region of HA have been isolated (10–17). These MAbs possess neutralizing activity against a variety of influenza virus strains and subtypes belonging to group 1 and/or group 2.

Despite recent advances enabling identification of broadly reactive B cells and antibody responses following infection or vaccination with novel influenza virus strains or subtypes, a number of open questions remain (18–21). Specifically, what conditions are necessary for induction of anti-HA stalk reactivity, and is this response commonly elicited following sequential infection with seasonal influenza virus isolates? Moreover, are HA stalk-specific antibody titers maintained following induction, and can these antibodies confer protection against in vivo challenge and prevent viral transmission?

Previously, our research group demonstrated that sequentially infecting ferrets with different seasonal influenza H1N1 (sH1N1) viruses isolated 8 to 13 years apart led to production of protective antibodies with HAI activity against the novel H1N1 A/California/07/2009 (CA/09) influenza virus (22). In this report, ferrets sequentially infected with sH1N1 viruses separated by longer chronological gaps (≥20 years), and consequentially separated by a greater antigenic distance, had antibody reactivity against the conserved HA stalk region. Following challenge with the novel H1N1 CA/09 virus, these sequentially infected ferrets had lower viral burdens and reduced rates of transmission.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Infection of ferrets.

Fitch ferrets (Mustela putorius furo, female, 6 to 12 months of age), negative for antibody to circulating influenza A (H1N1 and H3N2) and influenza B viruses, were descented and purchased from Marshall Farms (North Rose, NY, USA) or Triple F Farms (Sayre, PA, USA). Ferrets were pair housed in stainless steel cages (Shor-Line, Kansas City, KS, USA) containing Sani-Chips laboratory animal bedding (P. J. Murphy Forest Products, Montville, NJ, USA). Ferrets were provided with Teklad Global Ferret Diet (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI, USA) and fresh water ad libitum. Ferrets were infected with seasonal or pandemic H1N1 (pH1N1) influenza viruses (1 × 106 PFU) intranasally at 84-day intervals as previously described (22). Blood was collected from anesthetized ferrets via the anterior vena cava subclavin vein at day 14 and/or 84 ± 2 days after infection with each influenza virus. Serum was harvested and frozen at −20 ± 5°C until use.

In this report, we utilize the following nomenclature to describe the sequential infection schemes. Infection of ferrets with A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (PR/34) and reinfection 84 days later with PR/34 is denoted as PR/34→PR/34. Infection with PR/34 and 84 days later infection with A/Denver/1/1957 (Den/57) is denoted as PR/34→Den/57. Infection with PR/34 and 84 days later infection with A/Brisbane/59/07 (Bris/07) is denoted as PR/34→Bris/07. Likewise, infection with A/Singapore/6/1986 (Sing/86) and then 84 days later infection with A/New Caledonia/20/1999 (NC/99) or Bris/07 is denoted as Sing/86→NC/99 or Sing/86→Bris/07, respectively. Finally, the historical and modern sequentially influenza virus infections described previously (22) are denoted as PR/34→A/Fort Monmouth/1/1947 (FM/47)→Den/57 and A/Texas/36/1991 (TX/91)→NC/99→Bris/07, respectively.

Eighty-four days after the second influenza virus infection (day 168), ferrets were challenged intranasally with 1 × 106 PFU of the novel 2009 H1N1 virus A/California/07/2009 (CA/09) in a volume of 0.5 ml in each nostril, for a total infection volume of 1 ml. Ferrets were monitored daily for weight loss, disease signs, and death for up to 14 days, as previously described (22). Experimental endpoints were defined as >20% weight loss, development of neurological disease, or an activity score of 3 (neither active nor alert after stimulation). Nasal washes were performed by instilling 3 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) into the nares of anesthetized ferrets. Washes were collected and stored at −80 ± 5°C °C until use.

Contact transmission experiments were conducted as previously described (23). Briefly, 24 h after inoculation, an influenza virus antibody-naive, uninfected ferret (contact) was cohoused with one of the influenza virus-inoculated ferrets (direct). Contact animals were monitored for clinical signs of disease, and nasal washes were performed as described previously. Animal studies were conducted with the approval of the University of Georgia's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

HAI.

A hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assay was used to assess functional antibodies to the HA able to inhibit agglutination of turkey erythrocytes (turkey red blood cells, or TRBC) and was conducted as previously described (22). To inactivate nonspecific inhibitors, serum samples were treated with receptor-destroying enzyme (RDE; Denka Seiken, Co., Japan) prior to being tested. The HAI titer was defined as the reciprocal dilution of the last well containing nonagglutinated TRBC. Serum samples lacking HAI at the 1:10 dilution were recorded as 5 for graphing purposes. In this report, we considered serum samples exhibiting HAI activity at dilutions of 1:20 or higher to be HAI positive.

ELISA.

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to assess total antibody titer against hemagglutinin (HA) and the presence of HA stalk-reactive specificities. Immulon 4HBX plates (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) were coated overnight at 4°C with 0.1 to 2 μg/ml of recombinant HA (rHA) in carbonate buffer, pH 9.4, containing 5 μg/ml fraction V bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Equitech-Bio, Kerrville, TX, USA) (50 μl/well) in a humidified chamber. Plates were either coated with 0.1 to 0.5 μg/ml rHA derived from H1N1 isolates (NC/99, Bris/07, and CA/09; Protein Sciences, Meriden, CT, USA) or 2 μg/ml chimeric HA (cHA) expressing the globular head region from H5N1 isolate A/Vietnam/1204/2004 and the HA stalk region from H1N1 isolate CA/09 (24) (kindly provided by Florian Krammer). Plates were blocked with ELISA blocking buffer (PBS containing 5% BSA, 2% bovine gelatin, and 0.05% Tween 20) for 90 min at 37°C. Serum samples were serially diluted 3-fold in blocking buffer, and plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed five times with PBS, biotin-conjugated goat anti-ferret IgG (γ-chain specific) secondary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) diluted in blocking buffer was added to the wells, and plates were incubated for 90 min at 37°C. Plates were washed five times with PBS, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (SA-HRP) (Thermo Fisher) diluted in blocking buffer was added to the wells, and plates were incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Following additional PBS washes, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) substrate was added, and plates were incubated at 37°C for 20 to 30 min. Colorimetric conversion was terminated by addition of 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and optical density was measured at 414 nm (OD414) using a spectrophotometer (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Titers are reported as the log10 of the reciprocal serum dilution at which the OD414 value was greater than the background plus three standard deviations or the OD414 value was greater than 0.1.

For competition assays, plates were coated overnight at 4°C with 0.1 μg/ml CA/09 rHA in carbonate buffer, pH 9.4, containing 5 μg/ml BSA (50 μl/well). Plates were blocked with ELISA blocking buffer for 90 min at 37°C. Serum samples were serially diluted 2-fold in blocking buffer (50-μl volume); then titrated quantities of unlabeled (C179) (TaKaRa Bio, Inc., Japan) or biotin-conjugated (CR6261) (in-house) HA stalk-specific MAb were added (50 μl/well), and plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed five times with PBS and either horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (γ-chain specific) (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) secondary antibody (C179) or SA-HRP (CR6261) diluted in blocking buffer was added; plates were the incubated for 90 min at 37°C. Following additional PBS washes, ABTS substrate was added, and plates were incubated at 30 min at 37°C. Colorimetric conversion was terminated by the addition of 5% SDS, and optical density was measured at 414 nm. Titers are reported as the log10 value of the last reciprocal serum dilution yielding greater than half-maximal inhibition of stalk-specific MAb binding signal. Samples exhibiting less than half-maximal inhibition at the first dilution tested (1:500) were recorded as 250 for graphing purposes. Inhibition was calculated according to the following formula: fraction of signal = [OD414(serum sample+MAb) − OD414(background)]/[OD414(MAb only) − OD414(background)].

Viral plaque assay.

Influenza virus titers from ferret nasal washes were used to assess viral burden, as previously described (22). Briefly, nasal washes (1 ml) from infected ferrets were thawed and diluted in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin (iDMEM). Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were plated (5 × 105 per well) in six-well plates. Samples (nasal washes) were diluted (dilution factors from 1 × 10−1 to 1 × 10−6) and overlaid onto the cells in 100 μl of iDMEM in duplicate and incubated for 1 h. Virus-containing medium was removed, monolayers were washed with iDMEM, and medium was replaced with 2 ml of L15 medium containing 0.8% agarose (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ) and tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-trypsin. Plates were incubated for 48 to 72 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Once plaques were clearly visible, agarose was removed and discarded. Cells were fixed with 10% buffered formalin and then stained with 1% crystal violet for 15 min. Following thorough washing with water to remove excess crystal violet, plates were dried, and plaques were counted. Values reported are numbers of PFU per milliliter (PFU/ml). Replicates of nasal wash samples lacking plaques at the lowest dilution (101) were assayed undiluted, and samples lacking plaques were recorded as 5 PFU/ml for graphing purposes.

Statistical analysis.

Two-tailed Student's t tests were performed using Prism, version 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA), and P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Sequential infection with antigenically distinct seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses elicits reactivity against a novel H1N1.

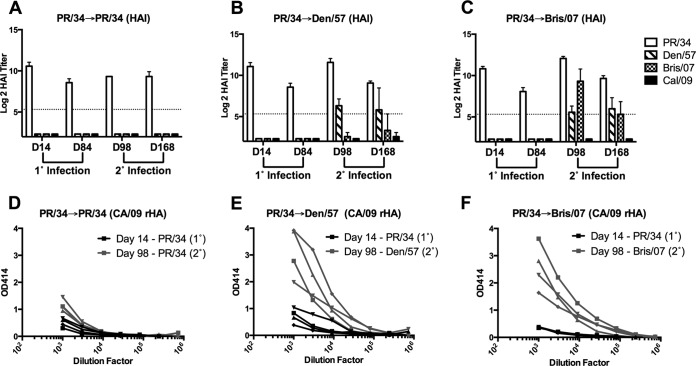

Infections of ferrets with seasonal H1N1 (sH1N1) virus isolate A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (PR/34) and 84 days later with either PR/34, A/Denver/1/1957 (Den/57) or A/Brisbane/59/2007 (Bris/07) are denoted as PR/34→PR/34, PR/34→Den/57, or PR/34→Bris/07, respectively. All ferrets infected with PR/34 had robust HAI activity against the PR/34 virus at day 14 postinfection, and this activity dropped slightly but was retained at day 84 (Fig. 1A to C). Consistent with our previous observations (22), serum samples collected at day 14 or day 84 following single infection with PR/34 lacked HAI activity against the Den/57 and Bris/07 sH1N1 isolates, as well as the novel H1N1 isolate A/California/07/2009 (CA/09). Moreover, sera collected 14 days following infection with the PR/34 influenza virus had negligible binding to Bris/07 HA (data not shown). Serum samples collected at day 98 and day 168 exhibited HAI activity against the PR/34, Den/57, and Bris/07 viruses used for secondary infection (Fig. 1A to C). Although HAI activity against the novel H1N1 CA/09 virus was not present at day 98, a strong and rapid induction of HAI-negative antibodies that bound CA/09 HA was detected following secondary infection with either Den/57 (PR/34→Den/57) (Fig. 1E) or Bris/07 (PR/34→Bris/07) (Fig. 1F) sH1N1 influenza virus. In contrast, CA/09 HA-specific antibody titers were not boosted following secondary infection with PR/34 (PR/34→PR/34) (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

Sequential infection with antigenically distinct seasonal H1N1 viruses elicits reactivity with novel H1N1 CA/09 in the absence of HAI activity. Groups of ferrets (n = 4) were initially infected with PR/34 and then infected 84 days later with PR/34, Den/57, or Bris/07 sH1N1, as indicated. (A to C) Serum collected at day 14 (D14) and day 84 (D84) following primary (1°) and at day 98 (D98) and day 168 (D168) following secondary (2°) infection was assessed for functional antibodies against the respective H1N1 isolates by HAI. Results are presented as the means ± standard errors of the means of the log2 HAI titer. Dashed lines denote limits of detection. (D to F) Serum collected at day 14 following primary (1°) and at day 98 following secondary (2°) infection was assessed for binding to CA/09 HA by ELISA. Symbols were used to denote individual ferrets. PR/34, A/Puerto Rico/8/1934; Den/57, A/Denver/1/1957; Bris/07, A/Brisbane/59/2007; CA/09, A/California/07/09.

Sequential infection with antigenically distinct sH1N1 viruses boosts HA stalk-specific antibodies.

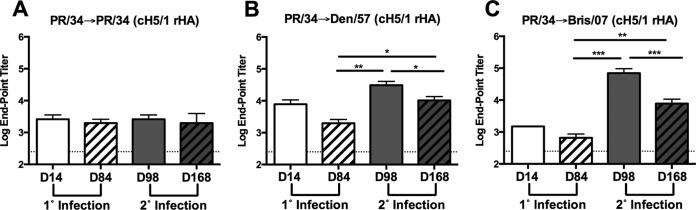

To determine if sequential infections with antigenically distinct sH1N1 viruses boosted HA stalk-specific antibodies, serum samples were tested for binding to chimeric HA with a globular head from an H5N1 viral isolate and the stalk region from CA/09 (cH5/1). Consistent with the modest CA/09 HA binding observed following secondary infection of PR/34-preimmune ferrets with PR/34 (PR/34→PR/34), an increase in binding to cH5/1 was not detected (Fig. 2A). However, there was a significant (P < 0.01 or P < 0.001, respectively) increase in antibody binding to cH5/1 following secondary infection of PR/34-preimmune ferrets with Den/57 (PR/34→Den/57) or Bris/07 (PR/34→Bris/07) influenza virus, respectively (Fig. 2B and C). Similar results were also obtained using a chimeric HA expressing the globular head from an H6N1 isolate (A/mallard/Sweden/81/02) with the HA stalk region from the PR/34 sH1N1 virus (cH6/1) (data not shown) (25).

FIG 2.

Antibodies targeting the stalk of HA are boosted following secondary infection with antigenically distinct seasonal H1N1 viruses. (A to C) Serum collected at day 14 and day 84 following primary (1°) and at day 98 and day 168 following secondary (2°) infection was assessed for binding to chimeric HA (cH5/1) expressing the globular head region from H5N1 isolate A/Vietnam/1204/2004 and the stalk regions from CA/09 by ELISA. Results are presented as the means ± standard errors of the means of the log10 endpoint titers (n = 4/time point for all panels). Dashed lines denote limits of detection. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (two-tailed paired t test).

In order to further confirm the elicitation of HA stalk-specific antibodies, a competitive binding assay was performed using the stalk-specific murine MAb C179 (26, 27). Serum samples collected at day 14 or day 84 following a single infection with sH1N1 (PR/34) were unable to compete with MAb C179 for recognition of CA/09 HA (Fig. 3A to C). However, at 14 days following secondary infection (day 98) of PR/34-preimmune ferrets with either a Den/57 or Bris/07 sH1N1 isolate, there was a significant (P < 0.01) increase in antibodies that competed with MAb C179 for binding to CA/09 HA (Fig. 3B and C).

FIG 3.

Stalk-specific antibodies are boosted following secondary infection with antigenically distinct seasonal H1N1 viruses. Serum collected at day 14 and day 84 following primary (1°) and at day 98 and day 168 following secondary (2°) infection was assessed for competition with stalk-specific MAb C179 (A to C) or CR6261 (D to F). Results are presented as the means ± standard errors of the means of the log10 50% inhibition titer (n = 4/time point for all panels). Dashed lines denote limits of detection. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (two-tailed paired t test).

A second stalk-specific MAb, CR6261, from human origin was also used to evaluate these serum samples (Fig. 3D to F) (16). Similar to the results obtained using MAb C179, serum collected at day 98 following secondary infection with a Den/57 or Bris/07 sH1N1 isolate was able to compete with MAb CR6261, albeit at lower titers (Fig. 3E and F). Collectively, these data indicate that stalk-specific antibodies are elicited following sequential infection of ferrets with antigenically distinct sH1N1 viruses.

Sequential infection with cross-reactive sH1N1 enhances HA stalk reactivity.

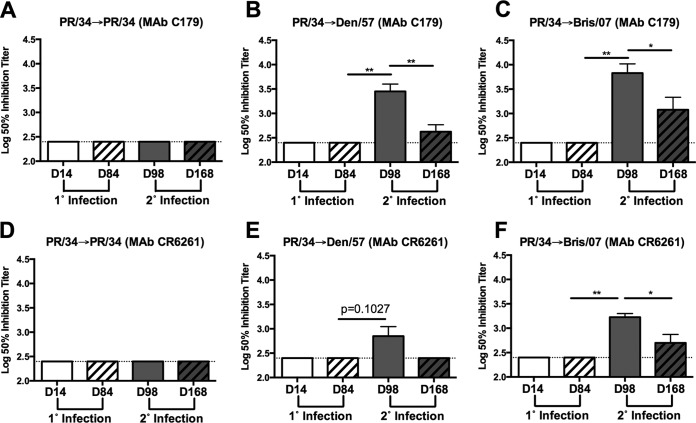

To determine whether HA stalk-specific antibody responses were boosted following sequential sH1N1 infection with isolates eliciting cross-reactive HA-specific binding but lacking RBS cross-reactivity and heterologous HAI activity, ferrets were infected with modern sH1N1 isolates segregated by a shorter chronological interval. Specifically, ferrets were infected with the sH1N1 isolate A/Singapore/6/1986 (Sing/86) and then infected with sH1N1 isolate A/New Caledonia/20/1999 (NC/99) (Sing/86→NC/99) or Bris/07 (Sing/86→Bris/07). All ferrets infected with Sing/86 had HAI activity against the Sing/86 virus at day 14 postinfection, and these titers remained elevated at day 84 (Fig. 4A and B). However, these serum samples lacked HAI activity against the NC/99 and Bris/07 sH1N1 viruses, as well as the novel H1N1 CA/09 virus. In contrast, NC/99 HA- and Bris/07 HA-specific antibodies were detected in sera collected at day 14 after Sing/86 virus infection (Fig. 4C and D). Additionally, the cross-reactive NC/99 HA-specific antibody titers were largely maintained, whereas the Bris/07 HA-specific titers waned by day 84 postinfection.

FIG 4.

Sequential infection with seasonal H1N1 virus boosts stalk specificities despite preexisting antibody cross-reactivity. Groups of ferrets (n = 16) were initially infected with Sing/86 and then infected 84 days later with NC/99 or Bris/07, as indicated. (A and B) Serum collected at day 14 and day 84 following primary (1°) and at day 98 and day 168 following secondary (2°) infection was assessed for functional antibodies against the respective H1N1 isolates by HAI (n = 16/time point). Results are presented as the means ± standard errors of the means of the log2 HAI titer. Dashed lines denote limits of detection. (C and D) Serum collected at day 14 and day 84 following primary (1°) and at day 98 and day 168 following secondary (2°) infection was assessed for binding to recombinant NC/99 or Bris/07 HA by ELISA (n = 8/time point). (E and F) Serum collected at day 14 and day 84 following primary (1°) and day at 98 and day 168 following secondary (2°) infection was assessed for binding to cH5/1 by ELISA (n = 8/time point). Results in panels C to F are presented as the means ± standard errors of the means of the log10 endpoint titer. Dashed lines denote limits of detection. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (two-tailed paired t test). Sing/86, A/Singapore/6/1986; NC/99, A/New Caledonia/20/1999; Bris/07, A/Brisbane/59/2007; CA/09, A/California/07/2009.

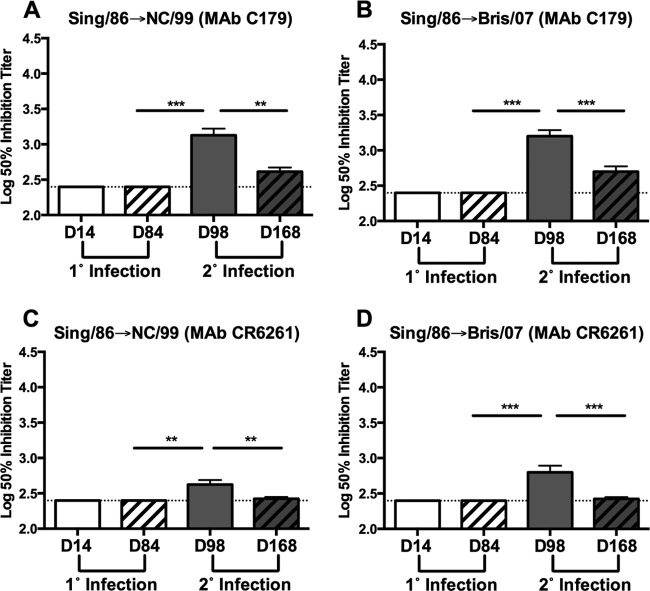

Following secondary infection (day 98) of Sing/86-preimmune ferrets with NC/99 or Bris/07 virus, there was a significant increase in antibodies reactive to cH5/1 HA (P < 0.001). Similar results were observed using cH6/1 HA protein (data not shown). These serum samples were also assessed for the presence of stalk-specific antibodies using C179 and CR6261 competitive binding assays. Serum samples collected 14 days postinfection (day 98) with NC/99 exhibited a significant increase in C179 (P < 0.001) and CR6261 (P < 0.01) competitive titers (Fig. 5A and C). Moreover, C179 and CR6261 competitive titers were significantly increased (P < 0.001) at day 98 following Bris/07 virus infection of Sing/86-preimmune ferrets.

FIG 5.

Stalk-specific antibodies are boosted following secondary infection with seasonal H1N1. Serum collected at day 14 and day 84 following primary (1°) and at day 98 and day 168 following secondary (2°) infection was assessed for competition with stalk-specific MAb C179 (A and B) or CR6261 (C and D). Results are presented as the means ± standard errors of the means of the log10 50% inhibition titer (n = 12 to 14/time point for all panels). Dashed lines denote limits of detection. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (two-tailed paired t test).

HA stalk-specific antibodies decline following sequential sH1N1 infection.

To determine whether stalk-specific antibody titers were maintained, serum collected 84 days following secondary influenza virus infection (day 168) was assessed for binding to the cH5/1 HA and the presence of antibodies that competed with MAb C179/CR6261. Serum collected at day 168 from PR/34→Den/57-infected and PR/34→Bris/07-infected ferrets exhibited binding to the cH5/1 HA (Fig. 2B and C). These titers were significantly elevated compared to levels in samples collected prior to secondary sH1N1 infection at day 84 (P < 0.01). However, cH5/1-specific antibody titers were significantly reduced at day 168 relative to those of day 98 for either group of sequentially infected ferrets (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001). A decline in C179 and CR6261 competitive titers was also observed at day 168. Specifically, PR/34→Den/57-infected ferrets had a significant reduction in C179 competitive titers (P < 0.01), and the CR6261 competitive titer dropped below the limit of detection at day 168 (Fig. 3B and E). A significant reduction in C179 and CR6261 competitive titers (P < 0.05) was also observed for PR/34→Bris/07-infected ferrets (Fig. 3C and F).

The serum collected at day 168 from ferrets infected with the Sing/86 virus followed by infection with NC/99 or Bris/07 virus was also evaluated for a decline in cH5/1 reactivity and C179/CR6261 competitive titers. Consistent with the previous data, antibody titers to cH5/1 remained significantly elevated at day 168 following infection with NC/99 or Bris/07 relative to the levels observed at day 84 (P < 0.01 or P < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 4E and F). However, in contrast to the decline in antibody binding to cH5/1 HA protein observed following secondary infection of PR/34-preimmune ferrets, a significant reduction in the antibody binding titer to cH5/1 HA did not occur between days 98 and 168 in Sing/86→NC/99 and Sing/86→Bris/07 sequentially sH1N1-infected ferrets (Fig. 4E and F). Despite the preservation of cH5/1 HA antibody titers at day 168 by Sing/86→NC/99-infected and Sing/86→Bris/07-infected ferrets, a significant reduction (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively) in both C179 and CR6261 competitive titers occurred from day 98 to day 168 (Fig. 5). Overall, these data indicate that stalk-specific antibody titers are not maintained following sequential infection with sH1N1.

Boost in anti-HA stalk antibody reactivity occurs in the absence of preexisting receptor-binding site antibody cross-reactivity.

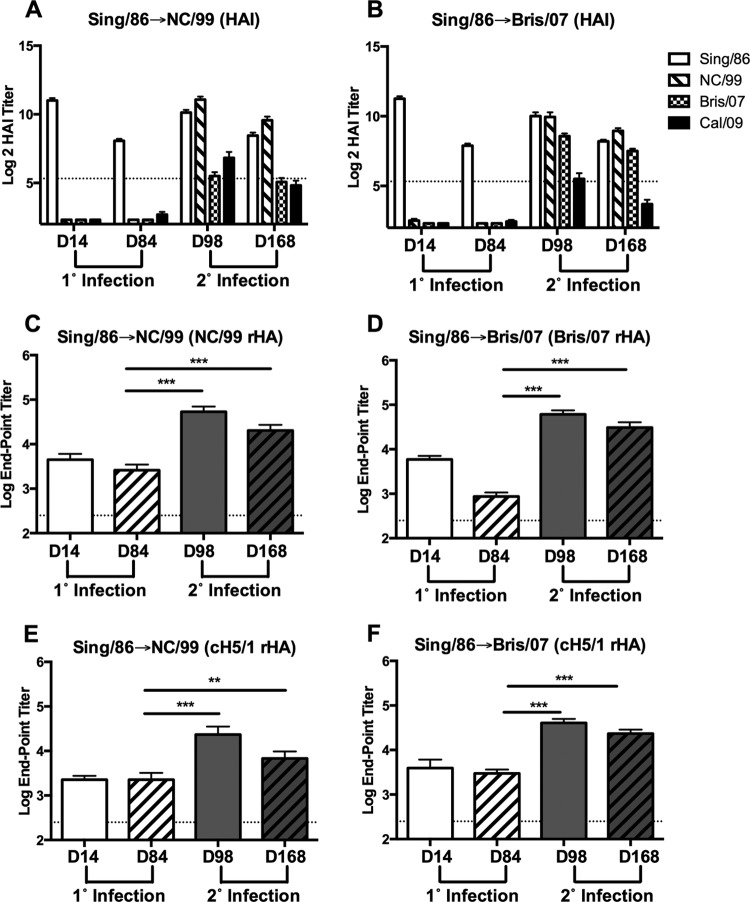

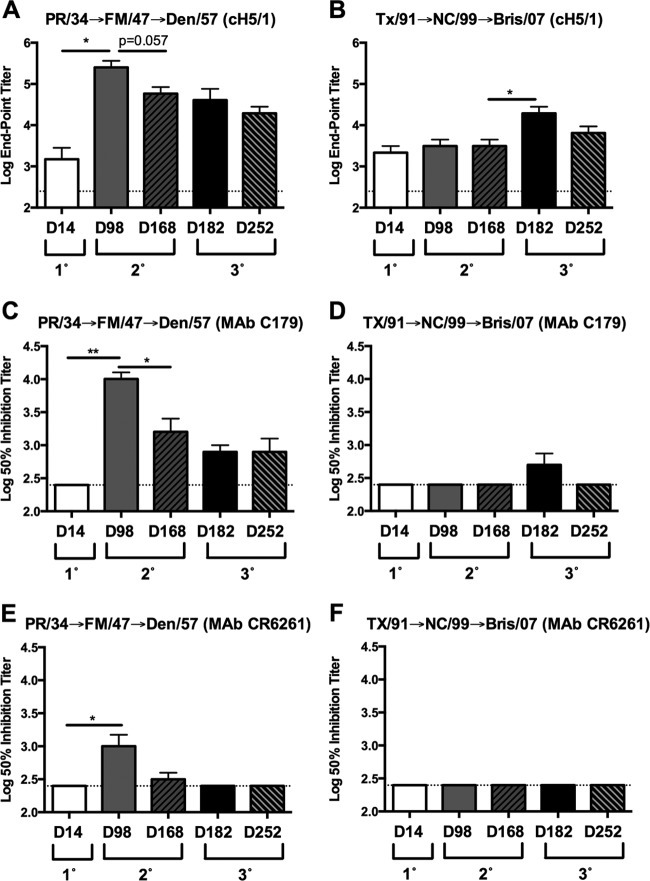

In order to further test the hypothesis that sequential infection with antigenically distinct sH1N1 isolates lacking HA RBS cross-reactivity would boost the antibody response directed against the HA stalk region, serum samples from ferrets sequentially infected with historical or modern sH1N1 isolates were evaluated for an increase in HA stalk-specific antibody titers (22). As previously reported, ferrets initially infected with PR/34 lacked HAI activity against A/Fort Monmouth/1/1947 (FM/47). In contrast, ferrets initially infected with A/Texas/36/1991 (TX/91) exhibited HAI activity against NC/99 prior to secondary infection. Consistent with the boost in HA stalk reactivity observed following secondary infection of PR/34 preimmune ferrets with Den/57 or Bris/07 sH1N1 isolates (Fig. 2B and C), a significant increase in cH5/1 HA-specific antibody titer (P < 0.05) was detected 14 days following secondary infection (day 98) of PR/34-preimmune ferrets with FM/47 (Fig. 6A). However, no such boost in cH5/1 reactivity was detected at day 98 following secondary infection of TX/91 preimmune ferrets with NC/99 but was observed 14 days (day 182) following the third infection of these ferrets with the Bris/07 sH1N1 isolate (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6B). Strikingly, an additional boost in cH5/1 reactivity was not observed at 14 days (day 182) following the third infection of PR/34→FM/47-preimmune ferrets with the Den/57 sH1N1 isolate despite the absence of preexisting HAI cross-reactivity, and this may reflect the subdominance of the HA stalk relative to the globular head region (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

Ferrets sequentially infected with historical and modern viruses exhibit a boost in stalk-specific antibody titers following infection with seasonal H1N1 isolates lacking receptor binding site cross-reactivity. Ferrets sequentially infected 12 weeks apart with PR/34 followed by FM/47 and Den/57 or with TX/91 followed by NC/99 and Bris/07 were previously described (22). (A and B) Serum collected at day 14 following primary (1°), at day 98 and day 168 following secondary (2°), and at day 182 and day 252 following tertiary (3°) infection was assessed for binding to chimeric HA (cH5/1) expressing the globular head region from H5N1 isolate A/Vietnam/1204/2004 and the stalk regions from CA/09 by ELISA. Results are presented as the means ± standard errors of the means of the log10 endpoint titers (n = 3/time point for panels A and B). Serum collected at day 14 following primary (1°), at day 98 and day 168 following secondary (2°), and at day 182 and day 252 following tertiary (3°) infection was assessed for competition with stalk-specific MAb C179 or CR6261, as indicated. Results in panels C to F are presented as the means ± standard errors of the means of the log10 50% inhibition titer (n = 3/time point for panels C to F). Dashed lines denote limits of detection. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (two-tailed paired t test). PR/34, A/Puerto Rico/8/1934; FM/47, A/Fort Monmouth/1/1947; Den/57, A/Denver/1/1957; TX/91, A/Texas/36/1991; NC/99, A/New Caledonia/20/1999; Bris/07, A/Brisbane/59/2007; CA/09, A/California/07/2009.

To further support the elicitation of HA stalk-specific antibodies in these ferrets, serum samples collected following the second and third infections with sH1N1 were assessed using the C179 and CR6261 competitive binding assays. Serum collected at 14 days following infection of PR/34-preimmune ferrets (day 98) with FM/47 exhibited a significant increase in both C179 and CR6261 (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively) competitive titers (Fig. 6C and E). Similarly, an increase in the C179 competitive titer was also detected at 14 days following the third infection (day 182) of TX/91→NC/99-preimmune ferrets with Bris/07 although the increase was modest and did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 6D). In agreement with the small increase in C179 competitive titers observed at day 182, no increase in the CR6261 competitive titer was detected in TX/91→NC/99-preimmune ferrets following the third infection with Bris/07 (Fig. 6F).

The serum samples collected at day 168 and day 252 from ferrets sequentially infected with historical or modern sH1N1 isolates were also evaluated for a decline in cH5/1 reactivity and C179/CR6261 competitive titers. Consistent with previous data, cH5/1 and C179/CR6261 competitive titers declined during the 12-week interval following either secondary or tertiary sH1N1 infection. Both cH5/1 antibody and C179/CR6261 competitive titers were reduced at day 168 relative to those at day 98 in PR/34→FM/47 sequentially infected ferrets although only the decline in C179 competitive titers was significant (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6A and C). Similarly, cH5/1 reactivity was reduced at day 252 relative to that at day 182 in ferrets sequentially infected with TX/91→NC/99→Bris/07, and C179 competitive titers dropped below the limit of detection (Fig. 6B and D). In aggregate, these data indicate that stalk-specific antibodies were elicited in both historical and modern sequentially infected ferrets following infection with sH1N1 isolates lacking HA RBS cross-reactivity.

Sequential infection with sH1N1 influenza viruses reduces viral replication and transmission of a novel H1N1 influenza virus.

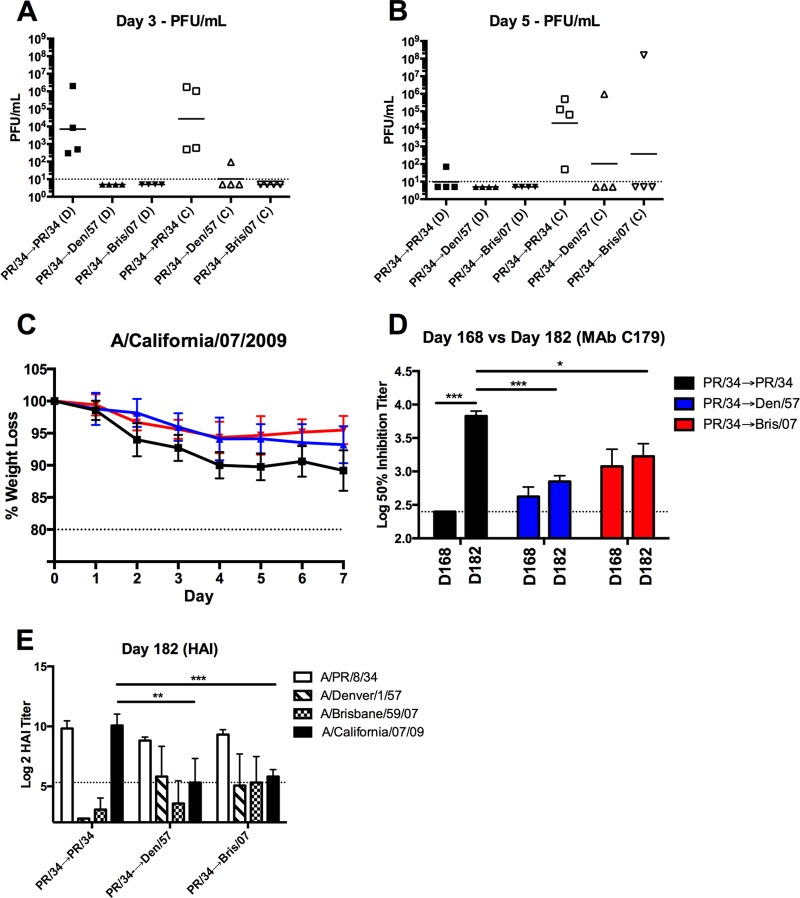

The induction of HA stalk-specific antibodies following sequential sH1N1 virus infection provided an opportunity to evaluate the role of stalk-specific antibodies in protecting against influenza virus challenge and moderating viral transmission to uninfected, naive ferrets in the absence of confounding HAI activity (Fig. 1B and C). Specifically, ferrets infected two times, 84 days apart, were challenged with the novel H1N1 CA/09 at day 168. Whereas high viral titers were present in nasal washes collected from PR/34→PR/34-infected ferrets at day 3 following CA/09 challenge, viral titers were undetectable in nasal washes from PR/34→Den/57- or PR/34→Bris/07-infected ferrets challenged with CA/09 at this time point. Moreover, each of the contact ferrets cohoused for 2 days with a CA/09-challenged PR/34→PR/34-infected ferret had viral titers in nasal washes at day 3 (Fig. 7A). In contrast, only one (1/4) contact animal pair housed with a CA/09-challenged PR/34→Den/57-infected ferret had a low viral titer (∼102 PFU/ml), and none of the contacts had detectable viral titers following paired housing with CA/09-challenged PR/34→Bris/07-infected ferrets at day 3. Furthermore, viral titers remained undetectable in day 5 nasal wash samples collected from CA/09-challenged PR/34→Den/57- or PR/34→Bris/07-infected ferrets (Fig. 7B). However, one contact cohoused ferret from these groups had high viral titers following 4 days of direct exposure. Additionally, PR/34→Den/57- or PR/34→Bris/07-infected ferrets exhibited reduced weight loss relative to weights of PR/34→PR/34-infected ferrets following CA/09 challenge (Fig. 7C).

FIG 7.

Reduced viral burden and transmission in ferrets with stalk antibody titers following novel H1N1 virus challenge. (A and B) Ferrets previously infected with seasonal H1N1 (Fig. 1 to 3) were challenged with novel H1N1 (A/California/07/2009). Directly inoculated (D) ferrets were cohoused with an influenza virus-naive contact (C)after 24 h. Viral titers were determined from nasal wash samples collected at day 3 and day 5, as indicated. The solid lines denote geometric mean viral titers for each group. (C and D) Directly inoculated preimmune ferrets were monitored daily for weight loss following infection with a novel H1N1 virus. Results are presented as the means ± standard deviations of individual ferrets within each group (C). Serum collected at day 168 and at day 182 (14 days following CA/09 challenge) from directly inoculated ferrets was assessed for C179 competitive titers (D). Results are presented as the means ± standard errors of the means of the log10 50% inhibition titer (n = 4/time point). Dashed lines denote limits of detection. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (two-tailed paired or unpaired t test). (E) Serum collected at day 182 from directly inoculated ferrets was assessed for functional antibodies against the respective H1N1 isolates by HAI. Dashed lines denote limits of detection. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (two-tailed unpaired t test).

To determine whether the directly infected preimmune ferrets mounted an immune response against the pH1N1 challenge virus, serum collected at day 182 (14 days after challenge) was assessed for C179 competitive titers and HAI activity against CA/09. PR/34→PR/34 sequentially infected ferrets exhibited a significant increase in the C179 competitive titer at day 182 relative to that at day 168 (P < 0.001) (Fig. 7D). Moreover, PR/34→PR/34-preimmune ferrets possessed C179 competitive titers that were significantly increased relative to those in PR/34→Den/57- and PR/34→Bris/07-preimmune ferrets (P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively). Furthermore, all of the PR/34→PR/34-infected ferrets possessed elevated HAI titers against CA/09 at day 182 (Fig. 7E). All PR/34→Bris/07-infected and almost all PR/34→Den/57-infected (3 out of 4) ferrets also had HAI activity against the CA/09 virus at day 182 although the HAI titers were significantly lower (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively) than those in PR/34→PR/34-infected ferrets (Fig. 7E). Collectively, the presence of HA stalk-specific antibody titers in the sH1N1 sequentially infected ferrets correlated with an absence of detectable viral replication, lower HAI titers against CA/09 following challenge, and mitigation of contact transmission in vivo.

DISCUSSION

In this study, HA stalk-specific antibodies were boosted following sequential infection of ferrets with antigenically distinct sH1N1 influenza virus isolates lacking HA RBS cross-reactivity. In addition, sequentially sH1N1 influenza virus-infected ferrets had undetectable nasal wash titers following challenge with novel H1N1 (CA/09) influenza virus. These same ferrets did not efficiently transmit the CA/09 influenza virus to cohoused naive contact ferrets. Collectively, these findings support the view that antibodies directed at the conserved HA stalk of influenza virus confer protection in vivo and that these specificities are boosted following encounters with antigenically distinct HA proteins (9, 28).

Antibodies directed against the HA globular head and possessing HAI activity against the novel H1N1 CA/09 influenza virus were elicited following sequential infection of PR/34-preimmune ferrets with FM/47 (PR/34→FM/47) (22). In contrast, HAI activity against the CA/09 virus was not observed in this study following PR/34→Den/57 sequential infection (Fig. 1B). Instead, an antibody response targeting the HA stalk of CA/09 was observed (Fig. 2B). Although both sets of PR/34-infected ferrets lacked cross-reactive HAI activity against the CA/09 virus after initial infection, it remains possible that differences in the memory B cell pools existed in these ferrets. Due to the outbred nature of the ferrets, these differences may have influenced the resulting recall response triggered by sequential infection with the respective sH1N1 isolate.

Another plausible and non-mutually exclusive explanation for these observations is that FM/47 HA, but not Den/57 HA, shares one or more common globular head epitopes with CA/09 HA. If so, FM/47 virus infection of PR/34-preimmune ferrets may have expanded or modified the existing memory B cell populations and/or the composition of serum antibody, and this may have resulted in HAI activity against the CA/09 virus. Previous studies showed that ferrets infected with the FM/47 virus, but not the Den/57 virus, had antibodies with high avidity for the CA/09 HA. In addition, ferrets singly infected with FM/47 virus had reduced viral titers and did not transmit virus to cohoused naive contact ferrets following challenge with the CA/09 virus (22). The lack of cross-reactivity between Den/57 and CA/09 HA is further supported by the observation that Den/57 virus infection of PR/34→FM/47-preimmune ferrets failed to enhance HAI titers against the CA/09 virus. Consequently, the induction of HAI activity against CA/09 following PR/34→FM/47 infection may have been fortuitous and might not have occurred if another historical sH1N1 isolate which did not elicit cross-reactive antibodies with CA/09 HA had been used for the secondary infection.

The findings presented are in agreement with earlier reports demonstrating a boost in HA stalk-specific antibody titers following sequential infection with seasonal influenza virus isolates (15, 25, 29). Moreover, a robust increase in C179 competitive antibody titers was observed following CA/09 challenge of PR/34→PR/34 sequentially infected ferrets (Fig. 7D). These data are consistent with the existing model that HA stalk-specific B cells seed the memory pool following primary infection and are more efficiently recruited into recall responses against a novel HA when competition with HA globular head-specific B cells is minimized (9, 28). In agreement with this notion, HA stalk-specific titers were not increased at day 98 following secondary infection of TX/91-preimmune ferrets with the NC/99 sH1N1 isolate because these viruses share RBS-specific HAI-positive cross-reactivity (Fig. 6B). However, the boost in HA stalk-specific titers observed following sequential infection of Sing/86-preimmune ferrets with the NC/99 or Bris/07 sH1N1 isolate demonstrates that HA stalk-specific B cells can participate in the recall response elicited by an antigenically related, but non-HAI cross-reactive, sH1N1 virus. Our findings also indicate that an HA stalk-specific antibody response can occur concurrently or sequentially with an RBS-specific response because HAI activity against the infecting strain was also present 14 days after infection (Fig. 1, 4, and 7). Cross-reactive, HAI-positive activity against the novel CA/09 virus also coincided with an increase in the HA stalk-specific antibody titer following the second infection of PR/34-preimmune ferrets with FM/47 and the third infection of TX/91→NC/99-preimmune ferrets with Bris/07 (Fig. 6) (22). Consistent with these observations, vaccination of influenza virus-preimmune human subjects with the monovalent pH1N1 vaccine (CA/09) elicited both an HAI-positive and stalk-specific antibody response (30, 31). In contrast, vaccination of influenza virus-preimmune human subjects with H5N1 predominantly elicits a response against the HA stalk alone; however, these subjects preferentially mount a globular head-specific response following booster vaccination (18, 19, 32).

Our observations suggest that HA stalk-specific B cells are sufficiently primed by sH1N1 infection of naive ferrets and that memory HA stalk-specific B cells commonly participate in the recall responses if the infecting sH1N1 virus lacks HAI cross-reactivity. Nevertheless, HA stalk-specific titers declined over the 12-week interval between influenza virus infections. Decay in HA stalk-specific titers also occurred following vaccination of influenza virus-preimmune humans with H5N1 (19). Moreover, the low abundance of HA stalk-specific antibody titers in the human population prior to introduction of pH1N1 suggests that a similar phenomenon occurs following infection or vaccination with sH1N1 (20, 33). Collectively, these observations are consistent with the subdominance of HA stalk responses relative to that of the globular head and the inefficiency of HA stalk-specific B cells to seed the long-lived plasma cell compartment (9, 34).

It is plausible that cross-reactive antibodies specific for the neuraminidase (NA) protein expressed by the novel H1N1 CA/09 virus may have contributed to the observed protection in this and the previous study (22). Since these studies utilized sH1N1 influenza virus isolates for sequential infection, it is likely that antibodies cross-reactive with the NA of CA/09 were elicited (35, 36). However, we consider it unlikely that the anti-NA antibodies contributed substantially to the observed protection against CA/09 challenge. First, we previously demonstrated that single infection with sH1N1 isolates, including PR/34, Den/57, and Bris/07, did not protect ferrets from the CA/09 challenge or limit their transmission of the virus (22). Second, mice passively transferred with antiserum recognizing NA from sH1N1 still exhibited substantial weight loss and high viral titers in the lung following challenge with novel H1N1 (35).

In this study, HA stalk-specific antibodies were detected following sequential sH1N1 infection of ferrets using a novel chimeric HA (cHA) and competitive binding assays. In support of the observed binding to CA/09 HA in the absence of HAI activity (Fig. 1), binding to cH5/1 and cH6/1 HA protein strongly suggested that the reactivity was HA stalk specific (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Competitive binding assays using the stalk-specific MAbs C179 and CR6261 also confirmed the induction of antibodies that bound, or were in close proximity, to a neutralizing epitope in the HA stalk region following sequential sH1N1 infection (Fig. 3) (16, 27, 37, 38). Both MAbs C179 and CR6261 possess neutralizing activity through their ability to block the low-pH-induced conformational change necessary for membrane fusion and infection (26, 37). Passive transfer of either MAb C179 or CR6261 conferred protection against a novel H1N1 and the pandemic H5N1 in a prophylactic challenge model (38, 39). However, only MAb CR6261 provided a therapeutic effect when administered after infection (39). Additionally, HA stalk-specific antibodies can also contribute to in vivo protection through promoting complement-dependent lysis and antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (40–42).

Despite a decline in stalk-specific serum antibody titers, sequentially infected ferrets (PR/34→Den/57 and PR/34→Bris/07) were protected against challenge with the novel H1N1 CA/09 and poorly transmitted the virus to naive contacts. Krammer et al. also demonstrated HA stalk-specific antibody efficacy against novel H1N1 challenge in the ferret model following sequential infection with chimeric HA (cHA)-expressing viruses (43). However, virus was recovered from nasal wash samples after pH1N1 challenge. The differential protection observed between these studies is likely to be attributable to the routes of antigen exposure and the infection regimen. In this study, the ferrets were sequentially infected with sH1N1 isolates via the intranasal route. In contrast, Krammer et al. initially infected the ferrets with a cHA-expressing influenza B virus via the intranasal route; but the second virus exposure was via the intramuscular route, and the third virus exposure utilized a replication-deficient viral vector (43). In support of the role(s) for route of administration and infection regimen, the initial production of HA stalk-specific antibody requires viral replication, and the magnitude of the boost correlates with the replication capacity of the second virus (25). Recent evidence also highlights the importance of secretory IgA in protecting the respiratory tract against influenza virus infection (44, 45). He et al. demonstrated that HA stalk-specific MAbs exhibit superior neutralization in vitro when they are expressed in the context of the IgA heavy chain (24). Collectively, these observations support the notion that ferrets sequentially infected with sH1N1 influenza virus exhibited superior protection against novel H1N1 challenge due to an increased abundance of HA stalk-specific Ig.

The presence of cross-reactive HAI antibody titers against the CA/09 virus at day 168 following sequential infection of Sing/86-preimmune ferrets with an NC/99 or Bris/07 sH1N1 isolate precluded challenge of these animals with pH1N1. Had reduced viral titers, as well as inefficient transmission to naive contacts following direct challenge of these preimmune ferrets, been observed, the relative contribution of globular head and stalk-specific antibodies would not have been distinguishable (Fig. 4). It is noteworthy that cH5/1-specific titers were maintained in these ferrets 12 weeks after sequential infection. In contrast, C179 and CR6261 competitive titers declined significantly during this same period. These findings suggest that sequential infection with antigenically related, but non-HAI cross-reactive, sH1N1 viruses elicited an HA stalk-specific antibody response against epitopes other than those recognized by MAb C179 and CR6261 (16, 26). In this regard, in vitro neutralization assays utilizing chimeric HA-expressing reassortant virus would have enabled comparison between the HA stalk-specific antibody responses described in this report (46).

The identification of broadly neutralizing antibodies targeting the conserved HA stalk region of influenza virus has motivated considerable effort toward the generation of HA stalk-specific immunogens (47). A variety of approaches for eliciting HA stalk-specific antibody responses have been evaluated in animal models with various degrees of success (43, 48–60). Collectively, these approaches aim to elicit HA stalk-specific responses through tactics that subvert HA globular head immunodominance. One such tactic is the use of chimeric HA (cHA)-expressing exotic globular heads in the context of group 1 or group 2 stalk domains (61). Another promising approach for eliciting HA stalk-specific antibody responses is the use of stabilized headless HA (50, 51, 54, 58, 60). Recently, protection of mice and ferrets against virulent H5N1 influenza viruses was demonstrated following vaccination with an HA-stalk specific immunogen fused to a ferritin nanoparticle (50). Additionally, rationally designed headless HA stem trimers, termed mini-HAs, conferred protection against lethal influenza virus challenge. Each of these stem-based vaccine approaches provides protection against influenza viruses that span both seasonal and pandemic influenza virus subtypes (43, 50, 53, 60). It remains unclear, however, if these approaches will elicit the desired antibody specificities in humans possessing various degrees of preexisting influenza virus immunity and whether the conferred protection will be sufficient to reduce infection, limit transmission, and resist antigenic drift (62). Overall, a better understanding of anti-HA stalk responses, especially within preimmune animal models and human subjects, will guide future efforts toward the generation of a broadly protective influenza vaccine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Chalise Bloom, Christopher Darby, and Bradford Lefoley for technical assistance. We thank Florian Krammer for providing the chimeric HA (cH5/1 and cH6/1). Influenza viruses were obtained from the Biodefense and Emerging Infections Resource, the Influenza Reagent Resource, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We have no conflicts of interest with the results reported in this study.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by internal start-up accounts at the University of Georgia and the Vaccine and Gene Therapy Institute to T.M.R. (grants UGA-001 and VGTI-005), by an Oak Ridge Visiting Scientist training program award to D.M.C., and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Library of Medicine. T.M.R. is a GRA Eminent Scholar and is supported by the Georgia Research Alliance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Houser K, Subbarao K. 2015. Influenza vaccines: challenges and solutions. Cell Host Microbe 17:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouvier NM, Palese P. 2008. The biology of influenza viruses. Vaccine 26(Suppl 4):D49–D53. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 2000. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Biochem 69:531–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerhard W. 2001. The role of the antibody response in influenza virus infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 260:171–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohmit SE, Petrie JG, Cross RT, Johnson E, Monto AS. 2011. Influenza hemagglutination-inhibition antibody titer as a correlate of vaccine-induced protection. J Infect Dis 204:1879–1885. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knossow M, Skehel JJ. 2006. Variation and infectivity neutralization in influenza. Immunology 119:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02421.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webster RG, Laver WG, Air GM, Schild GC. 1982. Molecular mechanisms of variation in influenza viruses. Nature 296:115–121. doi: 10.1038/296115a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellebedy AH, Ahmed R. 2012. Re-engaging cross-reactive memory B cells: the influenza puzzle. Front Immunol 3:53. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krammer F, Palese P. 2013. Influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-based antibodies and vaccines. Curr Opin Virol 3:521–530. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clementi N, De Marco D, Mancini N, Solforosi L, Moreno GJ, Gubareva LV, Mishin V, Di Pietro A, Vicenzi E, Siccardi AG, Clementi M, Burioni R. 2011. A human monoclonal antibody with neutralizing activity against highly divergent influenza subtypes. PLoS One 6:e28001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corti D, Voss J, Gamblin SJ, Codoni G, Macagno A, Jarrossay D, Vachieri SG, Pinna D, Minola A, Vanzetta F, Silacci C, Fernandez-Rodriguez BM, Agatic G, Bianchi S, Giacchetto-Sasselli I, Calder L, Sallusto F, Collins P, Haire LF, Temperton N, Langedijk JP, Skehel JJ, Lanzavecchia A. 2011. A neutralizing antibody selected from plasma cells that binds to group 1 and group 2 influenza A hemagglutinins. Science 333:850–856. doi: 10.1126/science.1205669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ekiert DC, Friesen RH, Bhabha G, Kwaks T, Jongeneelen M, Yu W, Ophorst C, Cox F, Korse HJ, Brandenburg B, Vogels R, Brakenhoff JP, Kompier R, Koldijk MH, Cornelissen LA, Poon LL, Peiris M, Koudstaal W, Wilson IA, Goudsmit J. 2011. A highly conserved neutralizing epitope on group 2 influenza A viruses. Science 333:843–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1204839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sui J, Hwang WC, Perez S, Wei G, Aird D, Chen LM, Santelli E, Stec B, Cadwell G, Ali M, Wan H, Murakami A, Yammanuru A, Han T, Cox NJ, Bankston LA, Donis RO, Liddington RC, Marasco WA. 2009. Structural and functional bases for broad-spectrum neutralization of avian and human influenza A viruses. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16:265–273. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan GS, Krammer F, Eggink D, Kongchanagul A, Moran TM, Palese P. 2012. A pan-H1 anti-hemagglutinin monoclonal antibody with potent broad-spectrum efficacy in vivo. J Virol 86:6179–6188. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00469-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan GS, Lee PS, Hoffman RM, Mazel-Sanchez B, Krammer F, Leon PE, Ward AB, Wilson IA, Palese P. 2014. Characterization of a broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibody that targets the fusion domain of group 2 influenza A virus hemagglutinin. J Virol 88:13580–13592. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02289-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Throsby M, van den Brink E, Jongeneelen M, Poon LL, Alard P, Cornelissen L, Bakker A, Cox F, van Deventer E, Guan Y, Cinatl J, ter Meulen J, Lasters I, Carsetti R, Peiris M, de Kruif J, Goudsmit J. 2008. Heterosubtypic neutralizing monoclonal antibodies cross-protective against H5N1 and H1N1 recovered from human IgM+ memory B cells. PLoS One 3:e3942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wrammert J, Koutsonanos D, Li GM, Edupuganti S, Sui J, Morrissey M, McCausland M, Skountzou I, Hornig M, Lipkin WI, Mehta A, Razavi B, Del Rio C, Zheng NY, Lee JH, Huang M, Ali Z, Kaur K, Andrews S, Amara RR, Wang Y, Das SR, O'Donnell CD, Yewdell JW, Subbarao K, Marasco WA, Mulligan MJ, Compans R, Ahmed R, Wilson PC. 2011. Broadly cross-reactive antibodies dominate the human B cell response against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection. J Exp Med 208:181–193. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellebedy AH, Krammer F, Li GM, Miller MS, Chiu C, Wrammert J, Chang CY, Davis CW, McCausland M, Elbein R, Edupuganti S, Spearman P, Andrews SF, Wilson PC, Garcia-Sastre A, Mulligan MJ, Mehta AK, Palese P, Ahmed R. 2014. Induction of broadly cross-reactive antibody responses to the influenza HA stem region following H5N1 vaccination in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:13133–13138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414070111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nachbagauer R, Wohlbold TJ, Hirsh A, Hai R, Sjursen H, Palese P, Cox RJ, Krammer F. 2014. Induction of broadly reactive anti-hemagglutinin stalk antibodies by an H5N1 vaccine in humans. J Virol 88:13260–13268. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02133-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pica N, Hai R, Krammer F, Wang TT, Maamary J, Eggink D, Tan GS, Krause JC, Moran T, Stein CR, Banach D, Wrammert J, Belshe RB, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P. 2012. Hemagglutinin stalk antibodies elicited by the 2009 pandemic influenza virus as a mechanism for the extinction of seasonal H1N1 viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:2573–2578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200039109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whittle JR, Wheatley AK, Wu L, Lingwood D, Kanekiyo M, Ma SS, Narpala SR, Yassine HM, Frank GM, Yewdell JW, Ledgerwood JE, Wei CJ, McDermott AB, Graham BS, Koup RA, Nabel GJ. 2014. Flow cytometry reveals that H5N1 vaccination elicits cross-reactive stem-directed antibodies from multiple Ig heavy-chain lineages. J Virol 88:4047–4057. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03422-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter DM, Bloom CE, Nascimento EJ, Marques ET, Craigo JK, Cherry JL, Lipman DJ, Ross TM. 2013. Sequential seasonal H1N1 influenza virus infections protect ferrets against novel 2009 H1N1 influenza virus. J Virol 87:1400–1410. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02257-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maines TR, Chen LM, Matsuoka Y, Chen H, Rowe T, Ortin J, Falcon A, Nguyen TH, Mai le Q, Sedyaningsih ER, Harun S, Tumpey TM, Donis RO, Cox NJ, Subbarao K, Katz JM. 2006. Lack of transmission of H5N1 avian-human reassortant influenza viruses in a ferret model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:12121–12126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605134103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He W, Mullarkey CE, Duty JA, Moran TM, Palese P, Miller MS. 2015. Broadly neutralizing anti-influenza virus antibodies: enhancement of neutralizing potency in polyclonal mixtures and IgA backbones. J Virol 89:3610–3618. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03099-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krammer F, Pica N, Hai R, Tan GS, Palese P. 2012. Hemagglutinin stalk-reactive antibodies are boosted following sequential infection with seasonal and pandemic H1N1 influenza virus in mice. J Virol 86:10302–10307. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01336-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dreyfus C, Ekiert DC, Wilson IA. 2013. Structure of a classical broadly neutralizing stem antibody in complex with a pandemic H2 influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Virol 87:7149–7154. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02975-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okuno Y, Isegawa Y, Sasao F, Ueda S. 1993. A common neutralizing epitope conserved between the hemagglutinins of influenza A virus H1 and H2 strains. J Virol 67:2552–2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiu C, Ellebedy AH, Wrammert J, Ahmed R. 2015. B cell responses to influenza infection and vaccination. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 386:381–398. doi: 10.1007/82_2014_425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margine I, Hai R, Albrecht RA, Obermoser G, Harrod AC, Banchereau J, Palucka K, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P, Treanor JJ, Krammer F. 2013. H3N2 influenza virus infection induces broadly reactive hemagglutinin stalk antibodies in humans and mice. J Virol 87:4728–4737. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03509-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li GM, Chiu C, Wrammert J, McCausland M, Andrews SF, Zheng NY, Lee JH, Huang M, Qu X, Edupuganti S, Mulligan M, Das SR, Yewdell JW, Mehta AK, Wilson PC, Ahmed R. 2012. Pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine induces a recall response in humans that favors broadly cross-reactive memory B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:9047–9052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118979109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomson CA, Wang Y, Jackson LM, Olson M, Wang W, Liavonchanka A, Keleta L, Silva V, Diederich S, Jones RB, Gubbay J, Pasick J, Petric M, Jean F, Allen VG, Brown EG, Rini JM, Schrader JW. 2012. Pandemic H1N1 influenza infection and vaccination in humans induces cross-protective antibodies that target the hemagglutinin stem. Front Immunol 3:87. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox RJ, Pedersen G, Madhun AS, Svindland S, Saevik M, Breakwell L, Hoschler K, Willemsen M, Campitelli L, Nostbakken JK, Weverling GJ, Klap J, McCullough KC, Zambon M, Kompier R, Sjursen H. 2011. Evaluation of a virosomal H5N1 vaccine formulated with matrix M adjuvant in a phase I clinical trial. Vaccine 29:8049–8059. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller MS, Gardner TJ, Krammer F, Aguado LC, Tortorella D, Basler CF, Palese P. 2013. Neutralizing antibodies against previously encountered influenza virus strains increase over time: a longitudinal analysis. Sci Transl Med 5:198ra107. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radbruch A, Muehlinghaus G, Luger EO, Inamine A, Smith KG, Dorner T, Hiepe F. 2006. Competence and competition: the challenge of becoming a long-lived plasma cell. Nat Rev Immunol 6:741–750. doi: 10.1038/nri1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marcelin G, DuBois R, Rubrum A, Russell CJ, McElhaney JE, Webby RJ. 2011. A contributing role for anti-neuraminidase antibodies on immunity to pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza A virus. PLoS One 6:e26335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palese P, Wang TT. 2011. Why do influenza virus subtypes die out? A hypothesis. mBio 2(5):e00150-11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00150-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ekiert DC, Bhabha G, Elsliger MA, Friesen RH, Jongeneelen M, Throsby M, Goudsmit J, Wilson IA. 2009. Antibody recognition of a highly conserved influenza virus epitope. Science 324:246–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1171491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakabe S, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Horimoto T, Nidom CA, Le M, Takano R, Kubota-Koketsu R, Okuno Y, Ozawa M, Kawaoka Y. 2010. A cross-reactive neutralizing monoclonal antibody protects mice from H5N1 and pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus infection. Antiviral Res 88:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friesen RH, Koudstaal W, Koldijk MH, Weverling GJ, Brakenhoff JP, Lenting PJ, Stittelaar KJ, Osterhaus AD, Kompier R, Goudsmit J. 2010. New class of monoclonal antibodies against severe influenza: prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy in ferrets. PLoS One 5:e9106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DiLillo DJ, Tan GS, Palese P, Ravetch JV. 2014. Broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies require FcγR interactions for protection against influenza virus in vivo. Nat Med 20:143–151. doi: 10.1038/nm.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terajima M, Cruz J, Co MD, Lee JH, Kaur K, Wrammert J, Wilson PC, Ennis FA. 2011. Complement-dependent lysis of influenza a virus-infected cells by broadly cross-reactive human monoclonal antibodies. J Virol 85:13463–13467. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05193-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jegaskanda S, Job ER, Kramski M, Laurie K, Isitman G, de Rose R, Winnall WR, Stratov I, Brooks AG, Reading PC, Kent SJ. 2013. Cross-reactive influenza-specific antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity antibodies in the absence of neutralizing antibodies. J Immunol 190:1837–1848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krammer F, Hai R, Yondola M, Tan GS, Leyva-Grado VH, Ryder AB, Miller MS, Rose JK, Palese P, Garcia-Sastre A, Albrecht RA. 2014. Assessment of influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-based immunity in ferrets. J Virol 88:3432–3442. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03004-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Renegar KB, Small PA Jr, Boykins LG, Wright PF. 2004. Role of IgA versus IgG in the control of influenza viral infection in the murine respiratory tract. J Immunol 173:1978–1986. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seibert CW, Rahmat S, Krause JC, Eggink D, Albrecht RA, Goff PH, Krammer F, Duty JA, Bouvier NM, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P. 2013. Recombinant IgA is sufficient to prevent influenza virus transmission in guinea pigs. J Virol 87:7793–7804. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00979-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He W, Mullarkey CE, Miller MS. 6 May 2015. Measuring the neutralization potency of influenza A virus hemagglutinin stalk/stem-binding antibodies in polyclonal preparations by microneutralization assay. Methods doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krammer F, Palese P. 2015. Advances in the development of influenza virus vaccines. Nat Rev Drug Discov 14:167–182. doi: 10.1038/nrd4529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneemann A, Speir JA, Tan GS, Khayat R, Ekiert DC, Matsuoka Y, Wilson IA. 2012. A virus-like particle that elicits cross-reactive antibodies to the conserved stem of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Virol 86:11686–11697. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01694-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang TT, Tan GS, Hai R, Pica N, Ngai L, Ekiert DC, Wilson IA, Garcia-Sastre A, Moran TM, Palese P. 2010. Vaccination with a synthetic peptide from the influenza virus hemagglutinin provides protection against distinct viral subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:18979–18984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013387107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yassine HM, Boyington JC, McTamney PM, Wei CJ, Kanekiyo M, Kong WP, Gallagher JR, Wang L, Zhang Y, Joyce MG, Lingwood D, Moin SM, Andersen H, Okuno Y, Rao SS, Harris AK, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, Graham BS. 2015. Hemagglutinin-stem nanoparticles generate heterosubtypic influenza protection. Nat Med 21:1065–1070. doi: 10.1038/nm.3927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wohlbold TJ, Nachbagauer R, Margine I, Tan GS, Hirsh A, Krammer F. 2015. Vaccination with soluble headless hemagglutinin protects mice from challenge with divergent influenza viruses. Vaccine 33:3314–3321. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steel J, Lowen AC, Wang TT, Yondola M, Gao Q, Haye K, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P. 2010. Influenza virus vaccine based on the conserved hemagglutinin stalk domain. mBio 1(1):e00018-10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00018-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Margine I, Krammer F, Hai R, Heaton NS, Tan GS, Andrews SA, Runstadler JA, Wilson PC, Albrecht RA, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P. 2013. Hemagglutinin stalk-based universal vaccine constructs protect against group 2 influenza A viruses. J Virol 87:10435–10446. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01715-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mallajosyula VV, Citron M, Ferrara F, Lu X, Callahan C, Heidecker GJ, Sarma SP, Flynn JA, Temperton NJ, Liang X, Varadarajan R. 2014. Influenza hemagglutinin stem-fragment immunogen elicits broadly neutralizing antibodies and confers heterologous protection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E2514–E2523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402766111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krammer F, Pica N, Hai R, Margine I, Palese P. 2013. Chimeric hemagglutinin influenza virus vaccine constructs elicit broadly protective stalk-specific antibodies. J Virol 87:6542–6550. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00641-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krammer F, Margine I, Hai R, Flood A, Hirsh A, Tsvetnitsky V, Chen D, Palese P. 2014. H3 stalk-based chimeric hemagglutinin influenza virus constructs protect mice from H7N9 challenge. J Virol 88:2340–2343. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03183-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eggink D, Goff PH, Palese P. 2014. Guiding the immune response against influenza virus hemagglutinin toward the conserved stalk domain by hyperglycosylation of the globular head domain. J Virol 88:699–704. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02608-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bommakanti G, Lu X, Citron MP, Najar TA, Heidecker GJ, ter Meulen J, Varadarajan R, Liang X. 2012. Design of Escherichia coli-expressed stalk domain immunogens of H1N1 hemagglutinin that protect mice from lethal challenge. J Virol 86:13434–13444. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01429-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bommakanti G, Citron MP, Hepler RW, Callahan C, Heidecker GJ, Najar TA, Lu X, Joyce JG, Shiver JW, Casimiro DR, ter Meulen J, Liang X, Varadarajan R. 2010. Design of an HA2-based Escherichia coli expressed influenza immunogen that protects mice from pathogenic challenge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:13701–13706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007465107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Impagliazzo A, Milder F, Kuipers H, Wagner M, Zhu X, Hoffman RM, van Meersbergen R, Huizingh J, Wanningen P, Verspuij J, de Man M, Ding Z, Apetri A, Kukrer B, Sneekes-Vriese E, Tomkiewicz D, Laursen NS, Lee PS, Zakrzewska A, Dekking L, Tolboom J, Tettero L, van Meerten S, Yu W, Koudstaal W, Goudsmit J, Ward AB, Meijberg W, Wilson IA, Radosevic K. 2015. A stable trimeric influenza hemagglutinin stem as a broadly protective immunogen. Science 349:1301–1306. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hai R, Krammer F, Tan GS, Pica N, Eggink D, Maamary J, Margine I, Albrecht RA, Palese P. 2012. Influenza viruses expressing chimeric hemagglutinins: globular head and stalk domains derived from different subtypes. J Virol 86:5774–5781. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00137-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krammer F, Palese P. 2014. Universal influenza virus vaccines: need for clinical trials. Nat Immunol 15:3–5. doi: 10.1038/nri3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]