Abstract

The COMBREX database (COMBREX-DB; combrex.bu.edu) is an online repository of information related to (i) experimentally determined protein function, (ii) predicted protein function, (iii) relationships among proteins of unknown function and various types of experimental data, including molecular function, protein structure, and associated phenotypes. The database was created as part of the novel COMBREX (COMputational BRidges to EXperiments) effort aimed at accelerating the rate of gene function validation. It currently holds information on ∼3.3 million known and predicted proteins from over 1000 completely sequenced bacterial and archaeal genomes. The database also contains a prototype recommendation system for helping users identify those proteins whose experimental determination of function would be most informative for predicting function for other proteins within protein families. The emphasis on documenting experimental evidence for function predictions, and the prioritization of uncharacterized proteins for experimental testing distinguish COMBREX from other publicly available microbial genomics resources. This article describes updates to COMBREX-DB since an initial description in the 2011 NAR Database Issue.

INTRODUCTION

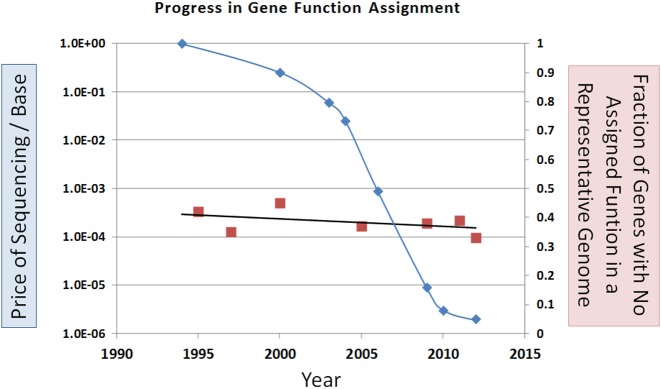

Knowledge of protein function is fundamental for an understanding of most of biology. However, only a small fraction of proteins have had their function characterized experimentally - the rest either have annotations that are either computationally predicted, or they lack any functional annotation. Furthermore, the high discovery rate of new genes by Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) is far greater than the rate of experimental characterization of their protein products (Figure 1). Thus, an ever larger percentage of proteins have functions predicted based on an ever smaller percentage of experimentally characterized ones. This places a premium on every new experimental test of gene function.

Figure 1.

Progress for DNA sequencing, blue diamonds, left axis, logarithmic scale. Progress in gene function assignment, red squares, right axis. Red squares represent individual genomes (selected randomly after 2007). Chronologically: H. influenzae, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, Magnetospirillum sp. strain AMB-1, Halogeometricum borinquense type strain (PR3T), Odoribacter splanchnicus type strain (1651/6T), Desulfotomaculum ruminis type strain (DLT).

Experimental sources supporting gene functional assignments have not been systematically documented. When newly discovered genes are annotated based on similarity to an experimentally characterized gene, they then become sources for future annotation of other genes. As a result, genes may be annotated based upon genes that are themselves far removed from solid experimental evidence. This can be a major source of inaccurate annotations.

The ‘annotation problem’ is both large and of uncertain accuracy. Size: our analysis of the proteins in COMBREX-DB identified close to 1 million hypothetical proteins with no annotated function, either computational or experimental (1). Error estimates: a recent study observed an average misannotation rate of 40% for 37 different protein families (2).

COMBREX-DB was created to provide comprehensive information of protein function, and to help experimentalists effectively deal with the two annotation issues listed above (lack of functional annotation and errors in existing annotation). This broader effort has been previously described (1,3). Two guiding philosophies of COMBREX are the maximal leveraging of existing experimental information, and the facilitation of maximal information gain with each new experiment. These guidelines are addressed primarily through the inclusion of traceable information connecting annotations or predictions to their foundational experiments, and the identification and ranking of proteins according to likely information gain from a potential experimental result.

DATA SOURCES AND CONTENT

Currently in the COMBREX Database, there is information regarding protein function status for ∼3.3 million known and predicted proteins from over 1000 completely sequenced microbial genomes, organized into more than 400 000 protein families. Much of the protein data was obtained from RefSeq (4) and UniProt(5), and information regarding protein clusters followed the system established by the NCBI Protein Clusters Database (ProtClustDB) (6).

Protein function status was comprehensively assessed (the Gene Ontology ‘molecular function’, unless otherwise stated), and each protein in COMBREX-DB was assigned into one of three major functional categories, which were color-coded: proteins whose function is experimentally characterized are designated green, proteins that have functional predictions but have not been experimentally characterized are blue, and those with no available computational predictions or associated experimental data are black (a fourth category, gold, respresents green proteins that have been manually verified by a curator, and is in the early stages of development.) Most proteins, 76%, have at least one computational prediction of function, but have not been experimentally characterized (blue). The second in size group consists of proteins with no functional prediction (black), which characterizes ∼24% of all proteins. The smallest group, experimentally characterized proteins (green), comprises less than 1% of all proteins. Protein clusters are also categorized according to protein functional status, and they acquire the status of their most characterized protein (green > blue > black).

Pages for individual proteins emphasize information and data related to protein function, and provide links to the major databases (Entrez Gene, UniProt, etc.) for comprehensive description of all knowledge related to the gene. For a particular protein, COMBREX-DB highlights links to: PubMed for papers containing experimental characterization of the protein; PDB for associated structural data; BRENDA for biochemical data; the gene ontology (GO) for assigned functional categories (7); CDD and Pfam for protein domain information (8,9). COMBREX-DB also lists if the protein has been associated with any of 243 phenotypes, mostly related to drug resistance, drug sensitivity or essentiality. This information is obtained from other depositories or databases hosted by collaborators (10–20) and is rigorously documented.

COMBREX-DB hosts locally computational predictions about the protein's potential function, along with the associated provenance data users require to evaluate the prediction. Individual proteins may have multiple predictions of their function, from different providers using different methodologies, which may, or may not, agree. COMBREX-DB makes no attempt to evaluate the relative merits of various submitted predictions so long as the methods were described in a peer-reviewed manuscript—it is intended to serve as an open platform and comprehensive repository for functional predictions which users may browse. If the function of a protein has not been experimentally verified, and has only a predicted function, COMBREX-DB is the first database that attempts to trace predictions to their source data by providing computed links to closely related proteins that have been experimentally characterized. This enables the user to obtain highly relevant experimental information that will eventually highlight the differences that might cause a change of function.

Most proteins are grouped with closely related proteins into protein clusters, or families, whenever possible, on the assumption that proteins of highly related sequence likely have shared function (6). Each cluster has a dedicated page that again highlights information related to protein function. Central to every protein family is a listing of each protein member, and a succinct listing of each protein's functional classification status, whether it has a solved structure, whether it is been purified and expressed, whether it has any shared Pfam domains with human proteins, and whether or not a specific functional prediction has been submitted directly to COMBREX for that protein. This information is useful to prioritize experimental validations and guiding experiments.

Additionally, COMBREX-DB lists properties of the cluster, such as the phylogenetic spread of protein members, so that one can assess the degree of conservation for this protein family. As will be detailed below, information is also presented that allows a user to gauge in a simple manner which proteins might be most informative if their function was experimentally validated.

While COMBREX groups genes in clusters, multiple annotation methods are integrated (1). In particular, we included BLAST style methods, phylogenetic methods (21), general functional linkages stored in VISANT that are computed based on a variety of context methods (22–24). Future versions of COMBREX aim to allow user-selected methods of organizing genes, whether using clusters, or functional linkage networks based on ideas described in (24–27).

COMBREX-DB has the capability to serve as a central repository for computational predictions. Many journals enforce a data availability policy that biological data set described in the manuscript must be publicly available (e.g. DNA sequences, or protein structural coordinates). However, there is no established public repository for computational predictions of protein function. While the number of predictions generated by a single method can be very large, the visibility of those predicted annotations may be low.

An important database design element in the construction of COMBREX-DB was the creation of an easily searchable database of functional predictions for microbial genes. Computational biologists can deposit functional predictions into COMBREX-DB, providing exposure for their work and allowing experimentalists to search for predictions they might be interested in testing. COMBREX-DB contains close to 14 000 predictions using nine distinct methods (1,21,23,28–32). Functional linkage connections for each protein can be visualized using the integrated VISANT platform (33), which can provide clues for functional context.

DATABASE USE

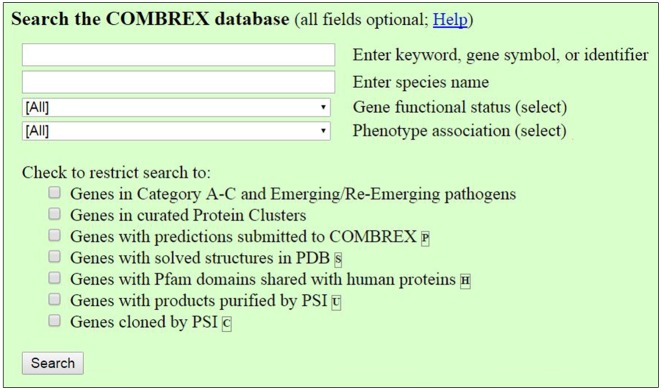

COMBREX-DB is designed to allow biologists to quickly analyze a protein's function status, data related to its function, and any predictions of function in a convenient manner. Users may search the COMBREX database for genes or groups of genes using the search box by gene names, descriptions, predictions, and identifiers. Searches can be restricted by a number of options to limit and focus search results. Searches may specify a specific organism or a pathogenic organism. Searches may specify the experimental validation status of a protein, and/or the protein cluster. Advanced search can also be used to restrict your search to genes with predictions submitted to COMBREX, genes containing a Pfam domain also found in human genes, genes with structure entries in RCSB Protein Data Bank, or proteins cloned and purified by the Protein Structure Initiative (PSI) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The search interface for COMBREX-DB, allowing users to search by gene, organism, functional status with a variety of filters.

All search results from COMBREX-DB are returned organized into protein families. A cluster will be returned if the search term matches any gene in the cluster, or the cluster itself. This is the case even if the search term specified one exact protein by unique accession number—in this case the results would return the protein cluster to which the query protein belonged. Opening the Cluster Detail page would then allow the user to quickly assess the cumulative functional information for all proteins in the cluster, and a second click would open the desired Protein Detail page. This strategy for the presentation of results has been found to be quite effective at enabling users to efficiently identify highly relevant functional information annotated for orthologous proteins, but which might not be included in the annotation of the query protein.

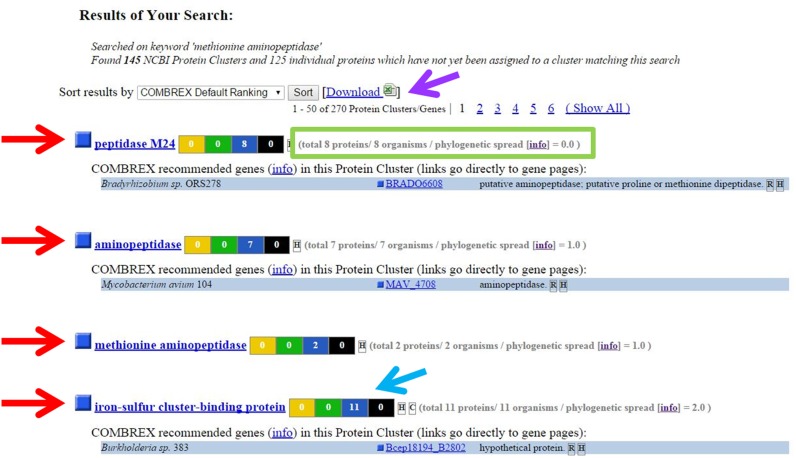

A sample search result is shown in Figure 3, in this case for the query ‘methionine aminopeptidase’. The results are organized by Cluster (red arrows). One hundred and forty-five clusters were found in the database, of which the top four are pictured. The number of proteins with various ranks of experimental determination is summarized by the color-coded boxes to the right of the cluster name (blue arrow). The search results are inclusive. The top result is a cluster named ‘Peptidase M24’ contains a protein labeled ‘putative Proline or Methionine dipeptidase’ which is the reason why that cluster was returned as a match.

Figure 3.

A sample search result for the query ‘methionine aminopeptidase.’ Results are organized by Cluster (red arrows). The functional status of member proteins are summarized graphically (blue arrow). Clusters are ranked by phylogenetic spread score (green box) and number of members (see text for details). All results can be easily downloaded (purple arrow).

The default rank order of search results follows a set of guidelines intended to emphasize to users the potential value of performing an experimental test of protein function of a member of that cluster. Therefore, clusters with zero experimentally characterized proteins are ranked ahead of clusters that contain protein(s) with experimentally determined function(s). Clusters that have members with wide distributions on a phylogenetic tree (and lower phylogenetic spread score; green box) are ranked ahead of clusters with narrower spreads. Lastly, larger clusters are ranked ahead of smaller clusters. Given the pressing need for experimental tests of protein function to keep up with the determination of new genome sequences, this rank order draws attention to the user that it may be more informative to experimentally test a protein that is conserved among the largest number of phyla or kingdoms, and that has a large number of closely related homologs. Users may rank results by other criteria according to personal preference. COMBREX-DB also highlights particular genes that may be the most informative to test experimentally within a cluster (blue boxes – see below).

Recommendation system

In COMBREX-DB, a proof-of-concept system for prioritizing experiments based on flexible criteria is provided. The identification of proteins to test by the researcher can balance interest in a specific protein, with ‘informative’ proteins using the proof-of-concept prioritization system. Typically, there is only a marginal increase in labor to biochemically test several proteins in parallel when one has procured all the reagents and created all the buffers for the testing of a single protein.

Prioritization of targets implemented in COMBREX-DB takes into account a number of factors, such as protein family size or phylogenetic distribution. In its prototype form, protein families were defined according to NCBI's ProtClustDB, and a multiple sequence alignment of each family was performed using MUSCLE (34). A distance matrix for the alignment was calculated using the protdist program in PHYLIP (35) under the Jones-Taylor-Thornton model of amino acid substitution (36). For each protein in a cluster, COMBREX-DB has pre-computed the average tree based distance to all other proteins. A small average distance for a protein suggests that the sequence is present near the centroid of the cluster (that is close to the evolutionary ancestor of the family), and that it would be expected to be a ‘typical’ protein for that cluster. For clusters without any experimentally validated members, the ‘central’ protein is recommended as a protein whose experimental validation would likely provide the greatest amount of information for all proteins in that cluster.

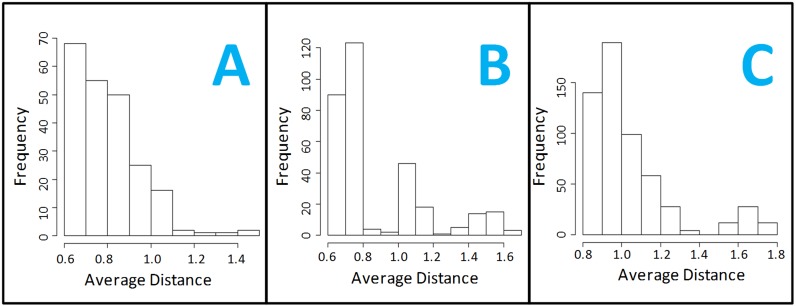

COMBREX-DB displays the histograms of the pre-computed distances on the Cluster Detail pages. For some protein families without evidence of sub-classification, characterization of a single protein might be a good overall representation of the protein family's activity (Figure 4, Panel A). When the histograms become multi-modal (Figure 4, Panel B—two subclusters; Figure 4, Panel C—three subclusters) one would expect that characterization of a single protein from these would not be adequate, and that testing multiple proteins would be required. This type of information is not available on any existing database.

Figure 4.

Histograms of average distance for each protein in a cluster to all other proteins in the cluster. Proteins with the shortest average distance to all others, are considered ‘most typical’ for the cluster, and recommended for experimental testing in clusters which have no experimentally validated protein. Panels B and C indicate clusters with potential substructure, indicating the likely necessity for testing multiple proteins experimentally within a cluster for an adequate characterization.

Tracing annotations to experimental evidence

The vast majority of proteins have predicted functional annotations based on sequence similarities, and most of those result from automated processing of newly sequenced genomes. Unfortunately these pipelines typically do not record the source protein that was used to annotate the new protein. This can make the task of evaluating the likely veracity of an assigned annotation challenging. COMBREX-DB attempts to provide traceable links of assigned function to experimentally characterized proteins, whenever possible. Currently, COMBREX can associate roughly 45% of all annotations in COMBREX-DB (1.47M proteins) to experimentally characterized proteins, which could serve as the experimental source supporting the annotations. It is not possible to determine if the proposed associations were the experimental evidence used at the time of first annotation, but it may be regarded as the current closest relevant evidence in sequence space. This is surprising coverage, especially considering the incompleteness of our knowledge of experimentally characterized proteins (see the discussion of the Gold Standard Database in (1)).

Nearly a half million proteins are associated with proteins that have solved crystal structures. This is again impressive, as less than a half of one percent have solved structures, yet they inform structural considerations for over 14% of all proteins. Phenotype data is even more sparse, with a little over 5000 proteins having been recorded to exhibit one of the cataloged phenotypes on COMBREX-DB. However these proteins reside in clusters containing more than 300 000 proteins, and suggests the possibility that similar phenotypes might be observed when the expression of those proteins is altered. In sum, these examples concretely demonstrate the extent to which experimental results can be more effectively leveraged as the community attempts to process the very large amounts of gene sequence data.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

COMBREX-DB is a repository that attempts to emphasize the experimental foundations of our knowledge of protein function, by documenting the relationships between experiment, annotated function, and function prediction. While currently limited to bacteria and archaea, the architecture could accommodate entries on proteins from fungi, protozoa and viruses. It is our belief that there would be general utility to the inclusion of more types of phenotype data, including those that result from genetic manipulation of protein expression. The ability to search COMBREX-DB with sequence queries and return experimental information related to biochemical function, structure and phenotype was prototyped (37), and requires a web interface for wider dissemination. While these enhancements would all be of some benefit, the potentially most important role for COMBREX-DB remains its bridging position between the computational and experimental communities—providing a forum for computational biologists to share specialized function predictions to a wider audience, and enabling experimentalists to easily browse and consider testing specific predictions. Coordinated effort will be essential in order to shed light on, and increase biological understanding of, even a few of the many mysteries of genomes which NGS generates daily, terabyte by inexorable terabyte.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following people for providing useful advice, data, software, or other support: Peter Brown, Charles DeLisi, Lina L. Faller, Jyotsna Guleria, Daniel Haft, David Horn, John Hunt, Peter Karp, William Klimke, Stanley Letovsky, Ami Levy-Moonshine, Almaz Maksad, Mark McGettrick, Jeffrey H. Miller, Revonda Pokrzywa, Steven L. Salzberg, Daniel Segrè, Kimmen Sjölander, Rajeswari Swaminathan, and Dennis Vitkup. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

FUNDING

COMBREX is funded by a GO grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) [1RC2GM092602-01]. The open access publication charge for this paper has been waived by Oxford University Press - NAR Editorial Board members are entitled to one free paper per year in recognition of their work on behalf of the journal.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anton B.P., Chang Y.C., Brown P., Choi H.P., Faller L.L., Guleria J., Hu Z., Klitgord N., Levy-Moonshine A., Maksad A., et al. The COMBREX project: design, methodology, and initial results. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schnoes A.M., Brown S.D., Dodevski I., Babbitt P.C. Annotation error in public databases: misannotation of molecular function in enzyme superfamilies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts R.J., Chang Y.C., Hu Z., Rachlin J.N., Anton B.P., Pokrzywa R.M., Choi H.P., Faller L.L., Guleria J., Housman G., et al. COMBREX: a project to accelerate the functional annotation of prokaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D11–D14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tatusova T., Ciufo S., Federhen S., Fedorov B., McVeigh R., O'Neill K., Tolstoy I., Zaslavsky L. Update on RefSeq microbial genomes resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D599–D605. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UniProtConsortium. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D204–D212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klimke W., Agarwala R., Badretdin A., Chetvernin S., Ciufo S., Fedorov B., Kiryutin B., O'Neill K., Resch W., Resenchuk S., et al. The national center for biotechnology information's protein clusters database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D216–D223. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gene Ontology Consortium. Gene Ontology Consortium: going forward. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D1049–D1056. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marchler-Bauer A., Derbyshire M.K., Gonzales N.R., Lu S., Chitsaz F., Geer L.Y., Geer R.C., He J., Gwadz M., Hurwitz D.I., et al. CDD: NCBI's conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D222–D226. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finn R.D., Bateman A., Clements J., Coggill P., Eberhardt R.Y., Eddy S.R., Heger A., Hetherington K., Holm L., Mistry J., et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D222–D230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu B., Pop M. ARDB—Antibiotic Resistance Genes Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D443–D447. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu A., Tran L., Becket E., Lee K., Chinn L., Park E., Tran K., Miller J.H. Antibiotic sensitivity profiles determined with an Escherichia coli gene knockout collection: generating an antibiotic bar code. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1393–1403. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00906-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akerley B.J., Rubin E.J., Novick V.L., Amaya K., Judson N., Mekalanos J.J. A genome-scale analysis for identification of genes required for growth or survival of Haemophilus influenzae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:966–971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012602299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi K., Ehrlich S.D., Albertini A., Amati G., Andersen K.K., Arnaud M., Asai K., Ashikaga S., Aymerich S., Bessieres P., et al. Essential Bacillus subtilis genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:4678–4683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730515100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerdes S.Y., Scholle M.D., Campbell J.W., Balazsi G., Ravasz E., Daugherty M.D., Somera A.L., Kyrpides N.C., Anderson I., Gelfand M.S., et al. Experimental determination and system level analysis of essential genes in Escherichia coli MG1655. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:5673–5684. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.19.5673-5684.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobs M.A., Alwood A., Thaipisuttikul I., Spencer D., Haugen E., Ernst S., Will O., Kaul R., Raymond C., Levy R., et al. Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:14339–14344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036282100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salama N.R., Shepherd B., Falkow S. Global transposon mutagenesis and essential gene analysis of Helicobacter pylori. Journal of bacteriology. 2004;186:7926–7935. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.7926-7935.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liberati N.T., Urbach J.M., Miyata S., Lee D.G., Drenkard E., Wu G., Villanueva J., Wei T., Ausubel F.M. An ordered, nonredundant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 transposon insertion mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:2833–2838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511100103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato J., Hashimoto M. Construction of consecutive deletions of the Escherichia coli chromosome. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007;3:132. doi: 10.1038/msb4100174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Berardinis V., Vallenet D., Castelli V., Besnard M., Pinet A., Cruaud C., Samair S., Lechaplais C., Gyapay G., Richez C., et al. A complete collection of single-gene deletion mutants of Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2008;4:174. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto N., Nakahigashi K., Nakamichi T., Yoshino M., Takai Y., Touda Y., Furubayashi A., Kinjyo S., Dose H., Hasegawa M., et al. Update on the Keio collection of Escherichia coli single-gene deletion mutants. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009;5:335. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Datta R.S., Meacham C., Samad B., Neyer C., Sjolander K. Berkeley PHOG: PhyloFacts orthology group prediction web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W84–W89. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcotte E.M., Pellegrini M., Thompson M.J., Yeates T.O., Eisenberg D. A combined algorithm for genome-wide prediction of protein function. Nature. 1999;402:83–86. doi: 10.1038/47048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf Y.I., Rogozin I.B., Kondrashov A.S., Koonin E.V. Genome alignment, evolution of prokaryotic genome organization, and prediction of gene function using genomic context. Genome Res. 2001;11:356–372. doi: 10.1101/gr.gr-1619r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szklarczyk D., Franceschini A., Wyder S., Forslund K., Heller D., Huerta-Cepas J., Simonovic M., Roth A., Santos A., Tsafou K.P., et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D447–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Letovsky S., Kasif S. Predicting protein function from protein/protein interaction data: a probabilistic approach. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(Suppl. 1):i197–i204. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez Cuesta S., Rahman S.A., Furnham N., Thornton J.M. The classification and evolution of enzyme function. Biophys. J. 2015;109:1082–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muratore K.E., Engelhardt B.E., Srouji J.R., Jordan M.I., Brenner S.E., Kirsch J.F. Molecular function prediction for a family exhibiting evolutionary tendencies toward substrate specificity swapping: recurrence of tyrosine aminotransferase activity in the Ialpha subfamily. Proteins. 2013;81:1593–1609. doi: 10.1002/prot.24318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pertea M., Ayanbule K., Smedinghoff M., Salzberg S.L. OperonDB: a comprehensive database of predicted operons in microbial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D479–D482. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weingart U., Lavi Y., Horn D. Data mining of enzymes using specific peptides. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:446. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yanai I., Derti A., DeLisi C. Genes linked by fusion events are generally of the same functional category: a systematic analysis of 30 microbial genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:7940–7945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141236298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu J., Kasif S., DeLisi C. Identification of functional links between genes using phylogenetic profiles. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1524–1530. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yanai I., Mellor J.C., DeLisi C. Identifying functional links between genes using conserved chromosomal proximity. Trends in genetics: TIG. 2002;18:176–179. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02621-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu Z., Chang Y.C., Wang Y., Huang C.L., Liu Y., Tian F., Granger B., Delisi C. VisANT 4.0: Integrative network platform to connect genes, drugs, diseases and therapies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W225–W231. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edgar R.C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP–phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones D.T., Taylor W.R., Thornton J.M. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1992;8:275–282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood D.E., Lin H., Levy-Moonshine A., Swaminathan R., Chang Y.C., Anton B.P., Osmani L., Steffen M., Kasif S., Salzberg S.L. Thousands of missed genes found in bacterial genomes and their analysis with COMBREX. Biol. Direct. 2012;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]