Significance

Photosynthesis, the basis for life on earth, relies on proper balancing of the beneficial and destructive potentials of light. In cyanobacteria and red algae, which contribute substantially to photosynthesis, the core-membrane linker, LCM, is critical to this process. Light energy harvested by large antenna complexes, phycobilisomes, is funneled to LCM. Depending on light conditions, LCM passes this energy productively to reaction centers that transform it into chemical energy or, on oversaturating conditions, to the photoprotecting orange carotenoid protein (OCP). The details of these functions in the complex-structured LCM are poorly understood. The crystal structure and time-resolved data of the chromophore domain of LCM provide a rationale for the functionally relevant energetic matching, and indicate a mechanism for switching between photoproductive and photoprotective functions.

Keywords: cyanobacteria, phycobilisome, core-membrane linker, photosynthesis, crystal structure

Abstract

Photosynthesis relies on energy transfer from light-harvesting complexes to reaction centers. Phycobilisomes, the light-harvesting antennas in cyanobacteria and red algae, attach to the membrane via the multidomain core-membrane linker, LCM. The chromophore domain of LCM forms a bottleneck for funneling the harvested energy either productively to reaction centers or, in case of light overload, to quenchers like orange carotenoid protein (OCP) that prevent photodamage. The crystal structure of the solubly modified chromophore domain from Nostoc sp. PCC7120 was resolved at 2.2 Å. Although its protein fold is similar to the protein folds of phycobiliproteins, the phycocyanobilin (PCB) chromophore adopts ZZZssa geometry, which is unknown among phycobiliproteins but characteristic for sensory photoreceptors (phytochromes and cyanobacteriochromes). However, chromophore photoisomerization is inhibited in LCM by tight packing. The ZZZssa geometry of the chromophore and π-π stacking with a neighboring Trp account for the functionally relevant extreme spectral red shift of LCM. Exciton coupling is excluded by the large distance between two PCBs in a homodimer and by preservation of the spectral features in monomers. The structure also indicates a distinct flexibility that could be involved in quenching. The conclusions from the crystal structure are supported by femtosecond transient absorption spectra in solution.

The structural separation of light-harvesting and energy transduction processes allows photosynthetic organisms a flexible adaptation to the diverse light regimes present in terrestrial and aqueous habitats. In cyanobacteria and some phylogenetically related organisms that, together, provide a substantial proportion of global carbon fixation, light is harvested by hundreds of chromophores located in the peripheral antenna, namely, the phycobilisome (PBS). These excitations are then collected and transferred to the energy-transducing photosystems I (PSI) and PSII in the photosynthetic membrane via only two pigments, allophycocyanin B (AP-B) and the core-membrane linker (LCM) (1–5). AP-B preferentially serves PSI (2); it is structurally similar to the bulk phycobiliproteins of the PBS (6). LCM (denoted as ApcE according to the gene by which it is encoded), preferentially serving PSII (5), is a more complex multidomain protein, with an N-terminal section that binds the phycocyanobilin (PCB) chromophore, and is homologous to phycobiliproteins but carries an additional loop that probably acts as a membrane anchor to PSII (4, 7–10). The C-terminal section consists of two to four repeats (depending on the PBS type) that are homologous to the N-terminal domain (Pfam PF00427) of structural PBS proteins, rod-linkers [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID codes 3OSJ and 3OHW], and considered to organize the complex PBS core (9). They are probably also the loci for phosphorylation (11).

Both AP-B and LCM contain the same PCB chromophores as many of the bulk PBS pigments but show extremely red-shifted absorbance maxima that put their excitation energy between the excitation energy of the bulk biliproteins in the PBS and the excitation energy of the chlorophylls in the photosystems. They can funnel the energy collected by the PBS to the photosystems, or, alternatively, in the case of light overload, the excitations can be passed on to quenching centers to protect the photosystems from photodamage. This safeguarding function is particularly relevant for LCM serving the sensitive PSII. In cyanobacteria, energy is passed on to and quenched by the activated orange carotenoid protein (OCP) (12).

In the various phycobiliproteins, the absorptions of PCB cover the enormous range of ∼100 nm. These shifts and their intense fluorescence are brought about by noncovalent interactions with the apoproteins (13). The malleability of this flexible open-chain tetrapyrrole chromophore by the apoprotein is also further emphasized by its presence in sensory photoreceptors (phytochromes and cyanobacteriochromes), which serve as photoswitches (14–17). Here, PCB shows only low fluorescence. Excitation triggers, instead, a reversible photoreaction of the chromophore. The structural basis for adapting the chromophore to its different functions is important not only for understanding photosynthetic energy transfer but also for designing artificial photosynthetic systems (5) and for engineering fluorescent biomarkers (18, 19). In AP-B, the extreme red-shifted absorbance has recently been attributed to the planar geometry of the PCB chromophore on the ApcD subunit (6). The complex architecture and related poor solubility of LCM have so far prohibited detailed structural and functional analyses (3, 20, 21), including, in particular, the mechanism for its extreme red-shifted absorbance and fluorescence.

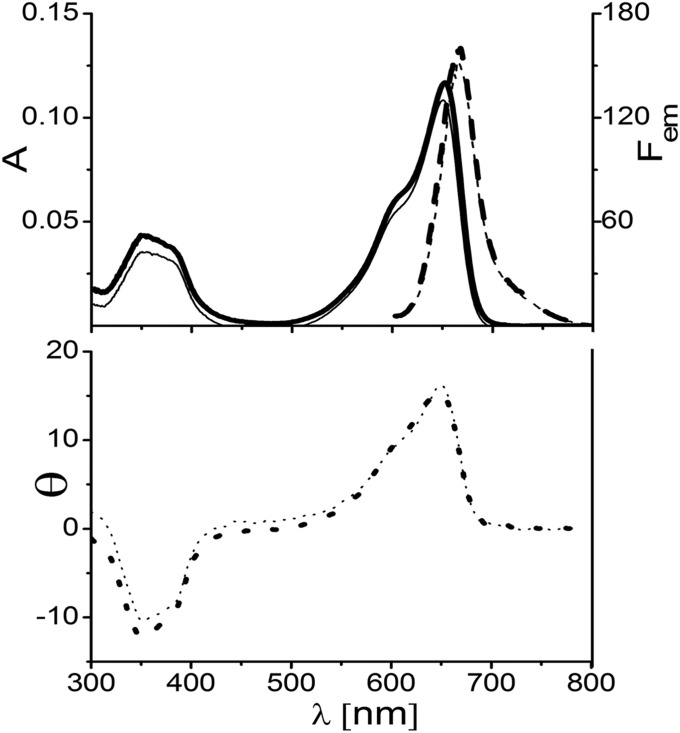

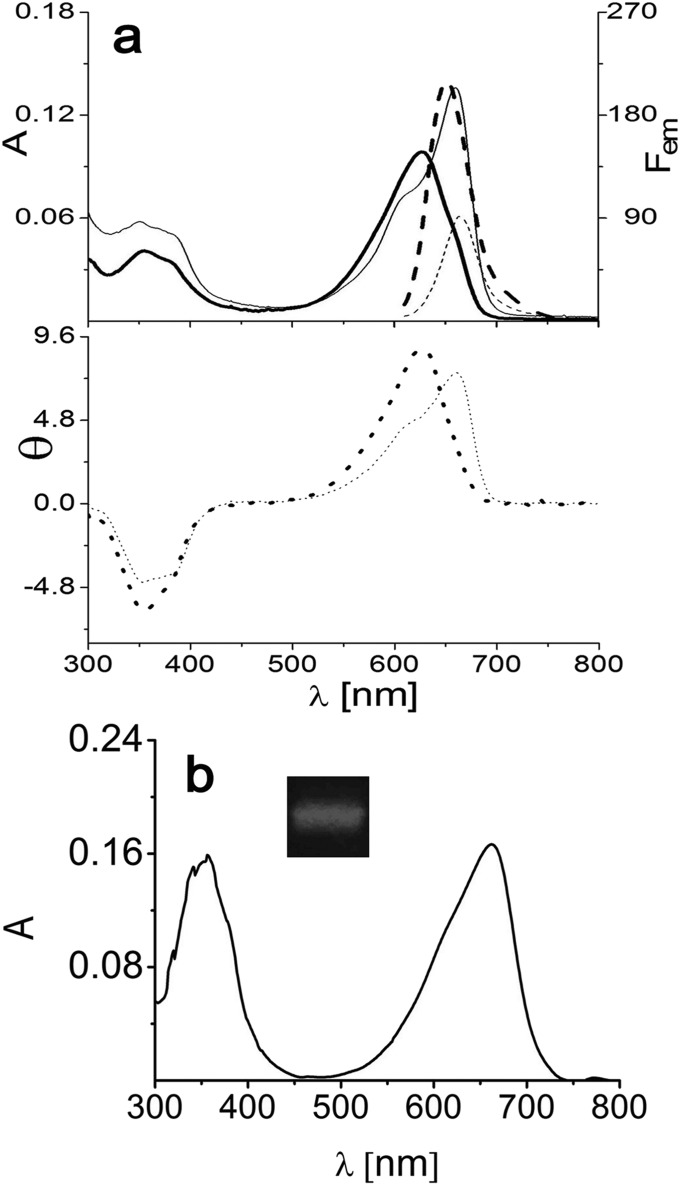

In this work, starting from a PCB-carrying chromophore domain construct of LCM from Nostoc sp. PCC7120, ApcE(1–240/Δ77–153) (if not otherwise mentioned, all ApcE constructs carry the PCB chromophore) lacking the hydrophobic loop (22), we have now generated soluble variants that retain the critical properties of the full-length protein, namely, autocatalytic chromophore binding (23, 24), red-shifted absorption and emission maxima, and high fluorescence yield. Here, we focus on the N-terminally truncated ApcE(20–240/Δ77–153), abbreviated as ApcEΔ, that allowed 3D structural characterization by X-ray crystallography to 2.2 Å and ultrafast absorption and fluorescence measurements. The full-length chromophore domain of LCM [ApcE(1–240)] is poorly soluble (24). Deletion of a putative loop (amino acids 80–150) thought to act as a membrane anchor (4, 7–10) improved solubility (22). Further deletion of 19 N-terminal residues for which no definite structural element was predicted (25) and in situ chromophorylation yielded ApcEΔ [ApcE(20–240/Δ77–153)] (Table S1). This construct was readily soluble, retained the optical properties of ApcE(1–240/Δ77–153) (Fig. 1 and Table S2), and could be crystallized. The combined results provide a basis for understanding the chromophore tuning of LCM, namely, an unexpected chromophore geometry resembling phytochromes rather than light-harvesting phycobiliproteins, which, in combination with π-π stacking, induces the extreme red shift, and a tight binding pocket that is responsible for fluorescence by inhibiting the photochemistry. The structure also indicates flexibility of the protein that could be relevant for its photoproductive and photoprotective functions.

Table S1.

Primers for apcE(20–240/Δ77–153) (apcEΔ), apcE(20–240/Δ38–39/Δ41–42/Δ77–153) (apcEΔΔ), and site-directed mutants

| Primer | Sequence | DNA |

| P1 | 5′-GTTCATATG AGTGTTAAGGCGAGTGGTGG-3′ | apcE(1–240/Δ77–153) |

| P2 | 5′-GTTCTCGAGAGGTGCTTTGAATTCTGTGA-3′ | |

| P3 | 5′-CTAGCTGTGGCAACAATCACCCAAGCG-3′ | apcE(20–240/Δ77–153) |

| P4 | 5′-CATGTGGATATCTCCTTCTTAAAGTTAAACAAAATTATTTC-3′ | |

| P5 | 5′-CTCCTCGCTAGCTATTTTGCATCTGGTG-3′ | apcE(20–240/Δ38–39/Δ41–42/Δ77–153) |

| P6 | 5′-CCTACCTAAAAAGCGGTCTTGCTGTTCC-3′ | |

| P7 | 5′-GCTCCATGGGTAGGGGTGAACTAGATG-3′ | apcE(36–240/Δ77–153) |

| P8 | 5′-GTGCTCGAGAGGTGCTTTGAATTCTGT-3′ | |

| P9 | 5′-TTTCCATGGGTGCAAAACGTCTAGAAA-3′ | apcE(50–240/Δ77–153) |

| P10 | 5′-GTGCTCGAGAGGTGCTTTGAATTCTGT-3′ | |

| P11 | 5′-GACGAACTCGCTAGCTATTTTGCATCTGGTG-3′ | apcEΔ-E39A |

| P12 | 5′-TAGTGCACCCCTACCTAAAAAGCGGTCTTGC-3′ | |

| P13 | 5′-GCTGAACTAGCAAGCTATTTTGCATCT-3′ | apcEΔ-D41A |

| P14 | 5′-TAGTTCACCCCTACCTAAAAAGCGGTC-3′ | |

| P15 | 5′-GACGCCCTAGCTAGCTATTTTGCATCTGGTG-3′ | apcEΔ-E42A |

| P16 | 5′-TAGTTCACCCCTACCTAAAAAGCGGTCTTGC-3′ | |

| P17 | 5′-GACGCCCTAGCTAGCTATTTTGCATCTGGTG-3′ | apcEΔ-E39A/E42A |

| P18 | 5′-TAGTGCACCCCTACCTAAAAAGCGGTCTTGC-3′ | |

| P19 | 5′-AAAGCTCTAGAAATTGCCCAACTTCTC-3′ | apcEΔ-R53A |

| P20 | 5′-TGCACCAGATGCAAAATAGCTTGCTAG-3′ | |

| P21 | 5′-GCCTTTCAGAAGATAGAAAACATGGCC-3′ | apcEΔ-I75A |

| P22 | 5′-CCGGTTAGCAGCACGAGAAACAATAAT-3′ | |

| P23 | 5′-GATAGAAAACATGGCCCTGAGCTTGCGGGACTTG-3′ | apcEΔ-K157L |

| P24 | 5′-CAAGTCCCGCAAGCTCAGGGCCATGTTTTCTATC-3′ | |

| P25 | 5′-GATAGAAAACATGGCCACGAGCTTGCGGGACTTG-3′ | apcEΔ-K157T |

| P26 | 5′-CAAGTCCCGCAAGCTCGTGGCCATGTTTTCTATC 3′ | |

| P27 | 5′-GAAAACATGGCCAAGGCCTTGCGGGACTTGTC-3′ | apcEΔ-S158A |

| P28 | 5′-GACAAGTCCCGCAAGGCCTTGGCCATGTTTTC-3′ | |

| P29 | 5′-TTGTCCTGGTTCTTGCGCTATGCTACTTATGC-3′ | apcEΔ-R160A |

| P30 | 5′-ATCTGCGAGACTCTTGGCCATGTTGCTTGG-3′ | |

| P31 | 5′-CCAAGAGCTTGCGGCACTTGTCCTGGTTC-3′ | apcEΔ-D161H |

| P32 | 5′-GAACCAGGACAAGTGCCGCAAGCTCTTGG-3′ | |

| P33 | 5′-CCAAGAGCTTGCGGGCCTTGTCCTGGTTCTTG-3′ | apcEΔ-D161A |

| P34 | 5′-CAAGAACCAGGACAAGGCCCGCAAGCTCTTGG-3′ | |

| P35 | 5′-GCGGGACTTGTCCTACTTCTTGCGCTATGC-3′ | apcEΔ-W164Y |

| P36 | 5′-GCATAGCGCAAGAAGTAGGACAAGTCCCGC-3′ | |

| P37 | 5′-GGACTTGTCCTGGTACTTGCGCTATGCTAC-3′ | apcEΔ-F165Y |

| P38 | 5′-GTAGCATAGCGCAAGTACCAGGACAAGTCC-3′ | |

| P39 | 5′-CCTGGTTCTTGCGCTTAGCTACTTATGCGATCG-3′ | apcEΔ-Y168L |

| P40 | 5′-CGATCGCATAAGTAGCTAAGCGCAAGAACCAGG-3′ | |

| P41 | 5′-CTAACATCATTGTGGTGGGCACAAGAGGTTTGCGG-3′ | apcEΔ-N184G |

| P42 | 5′-CCGCAAACCTCTTGTGCCCACCACAATGATGTTAG-3′ | |

| P43 | 5′-GTGAACACAAGAGGTGGGCGGGAAATTATTG-3′ | apcEΔ-L188G |

| P44 | 5′-CAATAATTTCCCGCCCACCTCTTGTGTTCAC-3′ | |

| P45 | 5′-GGGAAATTATTGAAAATGCTAGCTCTGGTGAAGCAACCATTG-3′ | apcEΔ-C196S |

| P46 | 5′-CAATGGTTGCTTCACCAGAGCTAGCATTTTCAATAATTTCCC-3′ | |

| P47 | 5′-TTCACCATTGTTGCTTTGCAAGAAATC-3′ | apcEΔ-A200F |

| P48 | 5′-TTCACCAGAGCAAGCATTTTCAATAAT-3′ | |

| P49 | 5′-GCAGCCGCAGAGATTGTGTCTCAATACATGG-3′ | apcEΔ-E221A |

| P50 | 5′-AGGATCTTTACGGAAATAAGAAAGTGATGCAGCTTTGATT-3′ |

Fig. 1.

Absorption (A, solid line), fluorescence (Fem, dashed line) (Top), and CD (θ, dotted line) (Bottom) spectra of ApcEΔ, which are similar to the respective spectra of the variants of ApcE(1–240/Δ77–153) (Table S2). Samples were reconstituted in E. coli (Table S5), purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography, and then dialyzed against potassium phosphate buffer (KPB; 20 mM, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.2) containing 0 M (thick lines) and 4 M (thin lines) urea. Emission spectra were obtained by excitation at 580 nm.

Table S2.

Absorption, fluorescence, and oligomerization state of PCB-ApcE variants

| Phycobiliproteins | Absorption | Fluorescence | Oligomerization state | Chromophorylation |

| λmax, nm | λmax, nm | Mass, kDa (n) | Relative yield, % | |

| PCB-ApcEΔ (0 M urea) | 654 | 668 | 38 (2) | 100 |

| PCB-ApcEΔ (4 M urea) | 652 | 667 | 35 (2) | |

| PCB-ApcEΔΔ (0 M urea) | 625 | 655 | 55 (3) | 50 |

| PCB-ApcEΔΔ (4 M urea) | 652 | 666 | 32 (2) | |

| PCB-ApcE(36–240/Δ77–153) (0 M urea) | 650 | 663 | 22 (1) | 33 |

| PCB-ApcE(36–240/Δ77–153) (4 M urea) | 652 | 666 | 28 (2) | |

| PCB-ApcE(50–240/Δ77–153) (0 M urea) | 648 | 663 | 15 (1) | 16 |

| PCB-ApcE(50–240/Δ77–153) (4 M urea) | 652 | 666 | 25 (2) | |

| PCB-ApcE(1–240/Δ87–130) | 662 | 668 | 51 (2) | n.d. |

| PCB-ApcE(20–240/Δ87–130) | 657 | 668 | 47 (2) | n.d. |

| PCB-ApcE(1–240/Δ77–153) | 660 | 667 | 47 (2) | n.d. |

| PCB-E39A*,‡ | 650 | 668 | n.d. | 10 |

| PCB-L40S†,‡ | 652 | 665 | n.d. | 6 |

| PCB-D41A* | 652 | 668 | 38 (2) | 113 |

| PCB-E42A*,‡ | 650 | 667 | n.d. | 5 |

| PCB-E39A/E42A*,‡ | 649 | 668 | n.d. | 4 |

| PCB-L43S†,‡ | 652 | 664 | n.d. | 3 |

| PCB-R53A*,‡ | 648 | 665 | n.d. | 7 |

| PCB-I75A* | 651 | 668 | n.d. | 131 |

| PCB-N154R* | 649 | 668 | n.d. | 71 |

| PCB-A156Q† | 656 | 666 | n.d. | 73 |

| PCB-K157L* | 654 | 671 | n.d. | 151 |

| PCB-K157T* | 654 | 672 | n.d. | 142 |

| PCB-S158A* | 647 | 660 | n.d. | 5 |

| PCB-S158C* | 644 | 663 | n.d. | 211 |

| PCB-S158C/C196S | — | — | — | 0 |

| PCB-R160A†,‡ | 640 | 662 | n.d. | 3 |

| PCB-R160S* | 645 | 668 | n.d. | 35 |

| PCB-D161A* | — | — | — | 0 |

| PCB-D161H* | — | — | — | 0 |

| PCB-W164A* | 648 | 667 | n.d. | 146 |

| PCB-W164Y* | 639 | 665 | n.d. | 110 |

| PCB-F165Y* | 643 | 661 | n.d. | 25 |

| PCB-Y168L* | 650 | 668 | n.d. | 40 |

| PCB-N184G* | 658 | 668 | n.d. | 37 |

| PCB-L188G* | 645 | 663 | n.d. | 20 |

| PCB-C196S* | — | — | — | 0 |

| PCB-A200F* | 652 | 668 | n.d. | 66 |

| PCB-F216A* | 652 | 664 | n.d. | 21 |

| PCB-E221A* | 653 | 668 | n.d. | 11 |

Spectra were obtained in KPB (20 mM, pH 7.0) or after addition of 4 M urea. The mutants are derived from the template apcE(20–240/Δ77–153) (i.e., apcEΔ) and apcE(20–240/Δ87–130), respectively. Further details on these mutants are to be published separately. Italicized numbers in parentheses denote oligomerization of the proteins. n.d., not determined.

Template apcE(20–240/Δ77–153) (i.e., apcEΔ).

Template apcE(20–240/Δ87–130).

Too few to determine.

Results and Discussion

Phycobiliprotein-Like Fold of Chromophore Domain.

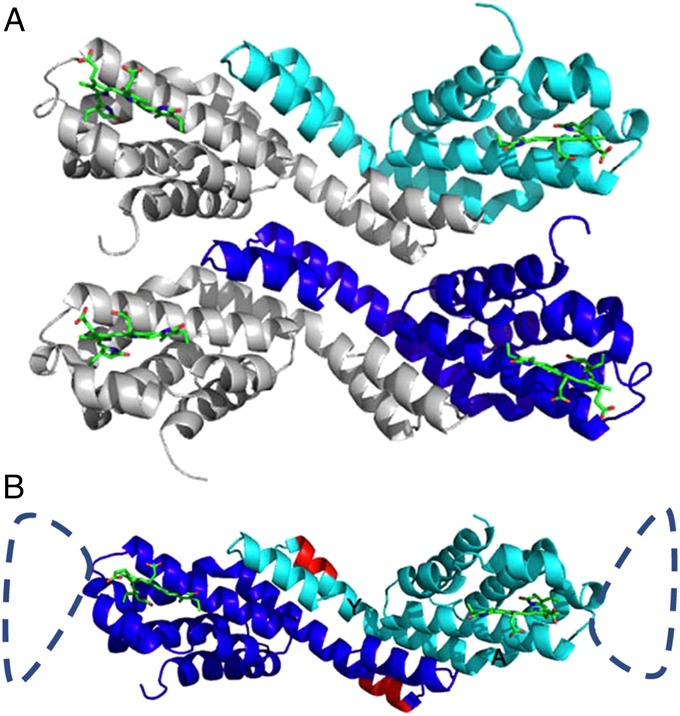

Crystals of selenomethionine-substituted ApcEΔ (ApcEΔ-Se) (see Materials and Methods and Table S1) diffracted to 2.97 Å (Table 1). There is one crescent-shaped homodimer in the asymmetrical unit (Fig. 2). The two chains of the homodimer associate with the two N-terminal helices X and Y (nomenclature as in phycobiliproteins), and the interface buries a surface area of 1,446 Å2 (26). The electron density is consistent with the entire sequence of ApcEΔ, with disorders only in the N-terminal Met and the C-terminal His-tag regions (Fig. S1). In the Ramachandran diagram (27), all 290 residues of the homodimer are found in the energetically allowed areas, with the noteworthy exception of the chromophore-binding Cys196 (“outliers” in Table 1).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics of X-ray crystallography

| PCB-ApcEΔ-Se | PCB-ApcEΔ | |

| Data collection | ||

| Beamline | ESRF, ID29 | EMBL, DESY, P13 |

| Space group | P21 | P22121 |

| Cell parameters, Å | a = 37.0, b = 66.6, c = 81.4 | a = 36.4, b = 80.6, c = 115.4 |

| α = 90.0°, β = 91.0°, γ = 90.0° | α = 90.0°, β = 90.0°, γ = 90.0° | |

| Resolution, Å | 40.70–2.97 | 50.00–2.20 |

| Rmerge | 0.061 (0.110) | 0.056 (0.215) |

| <I/σ(I)> | 21.7 (12.9) | 25.4 (9.0) |

| Completeness, % | 98.5 (95.5) | 99.9 (99.6) |

| Redundancy | 3.5 (3.5) | 8.5 (7.9) |

| Structure refinement | ||

| Resolution, Å | 19.49–2.97 (3.13–2.97) | 40.28–2.20 (2.32–2.20) |

| No. of unique reflections | 8,228 | 17,930 |

| Rwork, % | 17.6 | 18.5 |

| Rfree, % | 25.2 | 25.1 |

| Total no. of atoms | 2403 | 2451 |

| No. of molecules per ASU | 2 monomers | 2 monomers |

| Waters and ligands | 2 PCB | 62 HOH, 2 PCB, |

| Solvent content, % | 57.08 | 48.65 |

| Wilson B-factor, Å2 | 42.2 | 30.1 |

| rms, bonds | 0.021 | 0.023 |

| rms, angles | 1.65 | 1.74 |

| Ramachandran | ||

| Preferred regions | 283 (96.9%) | 281 (97.6%) |

| Allowed | 7 (2.4%) | 4 (1.4%) |

| Outliers | 2 (0.7%) | 3 (1.0%) |

| PDB ID code | 4XXK | 4XXI |

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell. ASU, asymmetric unit; DESY, Deutsches Elektronen Synchrotron; EMBL, European Molecular Biology Laboratory; ESRF, European Synchrotron Radiation Facility; <I/σ(I)>, signal-to-noise ratio of the measured intensities; PDB, Protein Data Bank.

Fig. 2.

(A) Structure of ApcEΔ bearing the PCB chromophore and arrangement of functional “homo”-dimers (chains A and B) in the crystal. Chain A is shown in cyan, and chain B is shown in blue. In the asymmetrical unit, the two chains are arranged in parallel. (B) Asymmetrical unit of ApcEΔ-Se containing a functional homodimer of chains A and B. The homodimers are similar to phycobiliprotein αβ-heterodimers; the position of the deleted amino acids 77–153 is indicated by the dashed loop. The PCB chromophores (green) in both monomers are shown as stick-and-ball presentations. Amino acids 38–39 and 41–42 (red), which have been deleted in the construct ApcEΔΔ, are located in helix Y (labeling shown in B). The angle between helices Y and A is relevant for the distance between two chromophores in the homodimer, and the positioning of the loop.

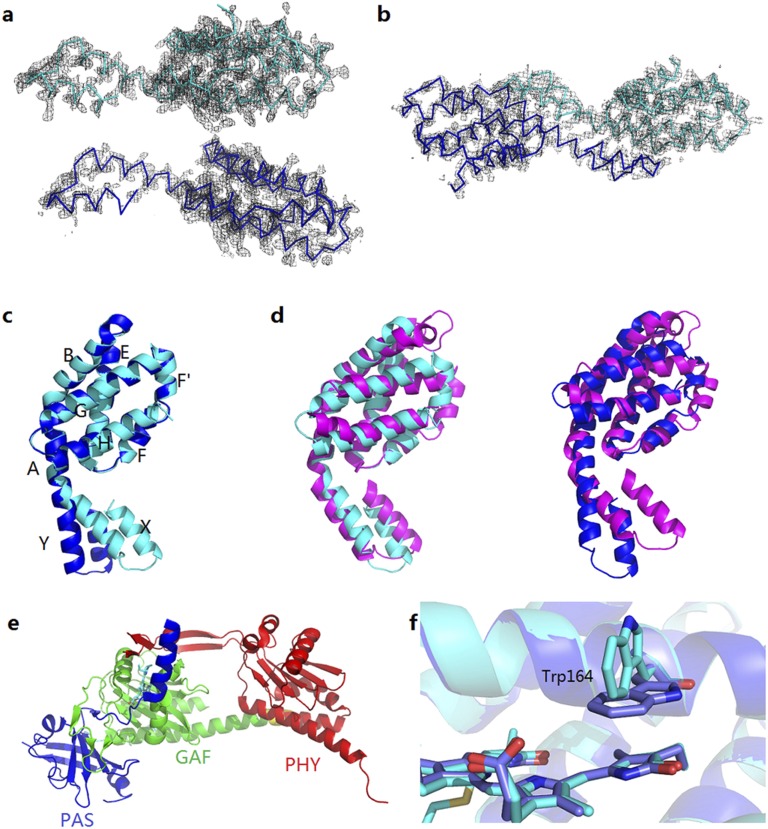

Fig. S1.

Side-by-side stereo-views of the 2Fo-Fc maps (contoured at 2σ) of PCB-ApcEΔ (A) and PCB-ApcEΔ-Se (B) show chain densities that are consistent with the entire sequence of ApcEΔ in chains A/B with disorders in the N-terminal Met and C-terminal His-tag regions. Structural comparison of PCB-ApcEΔ (C; chain A, cyan; chain B, blue), phycobiliprotein subunit ApcA (D, magenta) [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1B33], and phytochrome Cph1 (E) (PDB ID code 2VEA). GAF, acronym of common protein domain from cGMP phosphodiesterase, adenylyl cyclase, and FhlA; PAS, acronym of common protein domain from period circadian protein, Ah receptor nuclear translocator protein, and single-minded protein domain; PHY, phytochrome-specific domain. (F) In the structure of PCB-ApcEΔ at a higher resolution of 2.2 Å, different conformations at Trp164 in the two chains could be discerned.

Crystals of ApcEΔ are more compact, possibly due to lower water content (48.7% vs. 57.1% for ApcEΔ-Se). Using the coordinates of the Se derivative as a template for molecular replacement, the structure was resolved at 2.2 Å (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Again, there are two ApcEΔ molecules in the asymmetrical unit, but in parallel orientation. However, each of them forms a crescent-shaped dimer with molecules in neighboring unit cells that resembles the homodimer of ApcEΔ-Se. This arrangement is similar to the arrangement of αβ-heterodimers (“monomers”) of phycobiliproteins, but more extended: The kink between the globin domain and the N-terminal interaction domain (defined as the angle between helices A and Y) is smaller in ApcEΔ than in allophycocyanin (Fig. S1 C and D). Accordingly, the distance between the two chromophores (∼61 Å) is larger than in phycobiliprotein heterodimers (∼50 Å), and this distance is prohibitive for exciton coupling. Intradimer Förster energy transfer would also be poor, given the calculated times of ∼470 ps and the measured excited state lifetime of ApcEΔ (∼700 ps, discussed below) and of LCM in isolated core complexes (28, 29). WT LCM is also a homodimer in solution (24). Current PBS models, however, place a single molecule into a heterohexamer in each of the two basal core cylinders (4, 5). As in other isolated phycobiliprotein subunits, formation of homodimers probably reflects the absence of other allophycocyanin subunits (Fig. 2).

Although the overall structures of the two chains in the unit cell overlap well (Fig. 3 and Fig. S1), differences between them indicate some distinct flexibility. These differences include a different kink between the globin domain and the N-terminal helices responsible for aggregation; two rotamers of Gln228 in chain B; and different conformations of Trp164, which is located next to the chromophore (Fig. S1; discussed below). In chain A, the kink between helices A and Y is ∼120°, but it is widened to ∼130° in chain B. This altered kink changes the distance between the far end of helix Y (Asp13) and the chromophore by 5 Å. Provided that the structure of ApcEΔ reflects the structure of the full-length domain, this altered kink would also reposition the deleted loop that is located close to the chromophore (Fig. 2) and would protrude from the periphery of the LCM containing heterohexamer, corroborating the EM data of Chang et al. (4) (core rings A-3 in their terminology). A variation in the kink could then modulate the distance between the PCB and the nearby chlorophyll of PSII, and, thereby, energy transfer. Importantly, it could also modulate the interaction with the cyanobacterial quenching protein, OCP, where the carotenoid chromophore undergoes a translocation of 12 Å upon activation (30). In combination, these modifications would provide a structural model for modulating the flow of excitation between productive (to PSII) and photoprotective (to activated OCP) (discussed below).

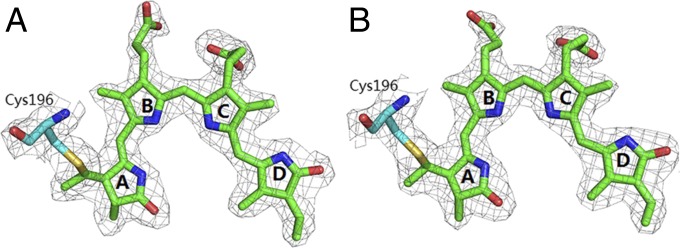

Fig. 3.

Structures of PCBs in chains A and B of the structure of ApcEΔ. Simulated-annealing omit maps for PCB in chain A (A) and chain B (B) of ApcEΔ show that both chromophores adopt the ZZZssa geometry. The chiral C31 at the PCB binding sites are R-configured in both chain A and chain B of ApcEΔ.

ApcE Chromophore Has Phytochrome-Type ZZZssa Geometry.

The geometry of the inherently flexible PCB chromophore contributes considerably to functionally relevant biophysical properties in biliproteins. The overall geometry of the PCB chromophores in all light-harvesting phycobiliproteins is ZZZasa (ref. 31 and references therein; nomenclature is provided in Fig. 4). However, PCB in ApcEΔ is exceptional in having, instead, the ZZZssa geometry (Figs. 3 and 4) that is characteristic for the photoactive bilin chromophores of the sensory photoreceptors, phytochromes, and cyanobacteriochromes (14–17). The unusual ZZZssa geometry of PCB is stabilized in ApcEΔ by the pivotal carboxyl group of Asp161: the pyrrolic nitrogens of rings A, B, and C are in H-bonding positions [NH-O = 2.7 (ring A), NH-O = 2.9 (ring B), and NH-O = 2.8 Å (ring C)] (Fig. 5). [These values refer to chain A but differ only slightly for chain B (same distances for N at rings A and B and 2.7 Å for N at ring C).] Such H-bonding interactions are restricted to rings B and C in other phycobiliproteins.

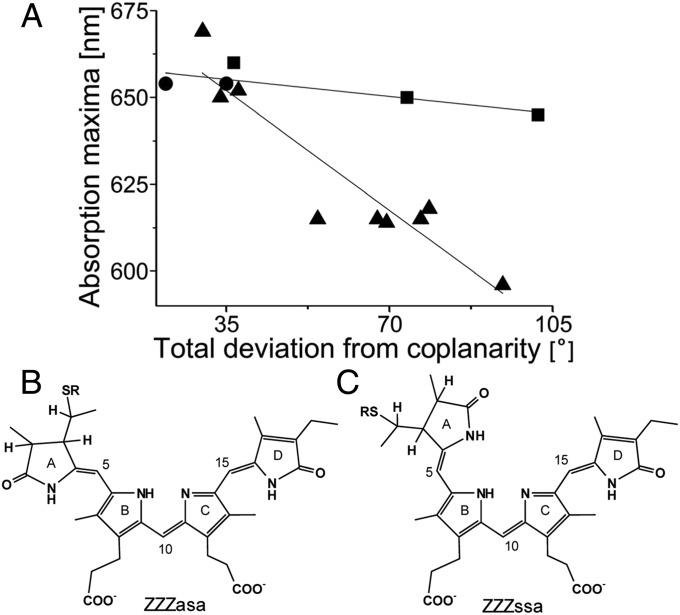

Fig. 4.

Relationships (A) between the absorption maxima and coplanarity of the PCB chromophore in the ZZZasa geometry (B) characteristic for light-harvesting phycobiliproteins and in the ZZZssa geometry (C) characteristic for sensory biliproteins. Over a range of 80°, the absorption maximum of PCB in the ZZZasa geometry (▲) changes by ∼80 nm (6), whereas the absorption maximum of PCB in the ZZZssa geometry (■) changes by only ∼13 nm. ApcEΔ (●) fits on the line. Coplanarity is defined here by summing the absolute values of dihedrals between rings A/B, B/C, and C/D.

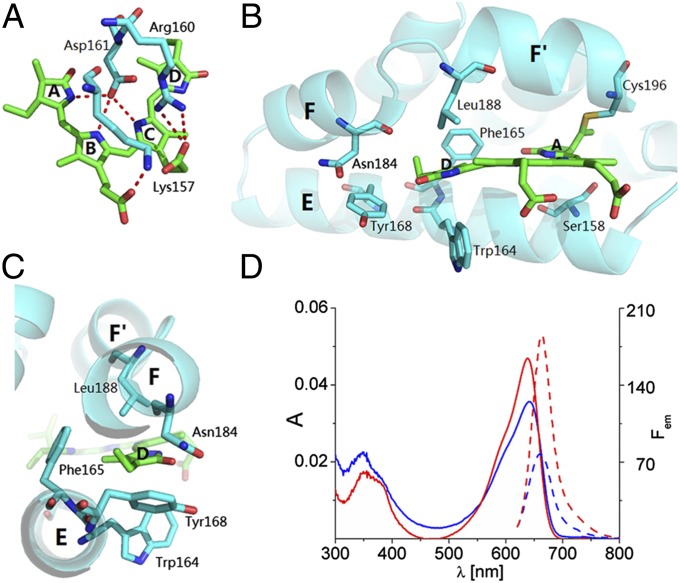

Fig. 5.

Hydrogen bond and van der Waals interactions in the chromophore pocket of ApcEΔ. (A) Rings A, B, and C of PCB (green) in ApcEΔ are involved in extensive hydrogen-bond interactions (dashed red lines) with protein side chains (cyan). (B) Bulky side chains around ring D of PCB provide a tighter chromophore pocket than in phytochromes and cyanobacteriochromes, where this ring rotates during photoisomerization. (C) Side view of the chromophore pocket shows that ring D is sandwiched amid the helices E, F, and F′, from which bulky side chains (Trp164, Phe165, Tyr168, Asn184, and Leu188) enforce a flat chromophore conformation. (D) Blue-shifted absorption (solid lines) and fluorescence (dashed lines) spectra of PCB-containing variants with a mutated chromophore pocket: ApcEΔ(W164Y) (red) and ApcEΔ(F165Y) (blue) (the parent construct is shown in Fig. 1, and data of more variants are provided in Table S2).

Interestingly, the absorption maximum of PCB in the ZZZssa geometry seems to show inherently red-shifted absorption (and fluorescence) that depends less on its coplanarity than the ZZZasa geometry (Fig. 4 and Table S2). There are only few examples of phytochromes or cyanobacteriochromes containing PCB (14–17), but the trend is pronounced. Extrapolating from these values, the absorption maxima of the chromophores in chains A (Φtot = 22°) and B (Φtot = 35°) are both expected at ∼660 nm, despite their moderate deviation from coplanarity [definition of coplanarity (Φtot) is provided in legend of Fig. 4]. This wavelength agrees with the absorption of ApcEΔ at 654 nm (Table S2). The spectrum of ApcEΔ is somewhat broadened and resolves into two bands, indicative of two species being present in solution. It is tempting to relate these two species to the two conformations seen in the crystal structure. A distinct difference is the conformation of Trp164 near the chromophore. It is parallel to ring D of the PCB at a minimal distance of 3.3 Å, which would allow substantial π-π stacking (Fig. S1F) and induce, at the same time, red-shifted absorption. In chain A, Trp164 is nearly perpendicular to ring D of PCB at a minimal distance of 3.9 Å. The relevance of Trp164 is corroborated by a 15-nm blue shift in absorption of variant W164Y (Fig. 5 and Table S2). The chains A and B are associated as a homodimer in solution (Table S2), and we could not unambiguously assign the two absorptions to the individual chains (Fig. 1). It is likely, however, that the different conformations of Trp164 in the two chains (i.e., π-π stacking on and off) relate to the “red” and “blue” states, respectively, of ApcE(20–240/Δ38–39/Δ41–42/Δ77–153) (ApcEΔΔ; discussed below). [Deletion of amino acids 38–39 and 41–42 in ApcEΔΔ even resulted in trimeric aggregates (Fig. 2 and Table S2). Although these trimers have blue-shifted absorption maxima (Table S2), their spectra undergo a red shift again upon dimerization that was induced by addition of urea or at elevated temperatures (Tables S2 and S3)]. The results would indicate a somewhat different mechanism for the red shifts of the two terminal emitters: coplanarity in AP-B (6) and π-π stacking in LCM.

Table S3.

Kinetics of the urea-induced conversion of the blue state (λmax = 625 nm) to the red state (λmax = 650 nm) of PCB-ApcEΔΔ

| Curea | Monitor, nm | τ1, s | A1, % | τ2, s | A2, % | R2 |

| 1 M | 616 | 190.1 (−) | 100.0 | — | — | 0.9962 |

| 658 | 195.7 (+) | 100.0 | — | — | 0.9980 | |

| 2 M | 616 | 111.1 (−) | 100.0 | — | — | 0.9939 |

| 658 | 132.3 (+) | 100.0 | — | — | 0.9929 | |

| 3 M | 616 | 85.9 (−) | 100.0 | — | — | 0.9908 |

| 658 | 58.7 (+) | 100.0 | — | — | 0.9976 | |

| 4 M | 616 | 24.8 (−) | 100.0 | — | — | 0.9922 |

| 658 | 20.8 (+) | 100.0 | — | — | 0.9888 | |

| 5 M | 616 | 33.1 (−) | 45.1 | 0.21 (−) | 54.9 | 0.9883 |

PCB-ApcEΔΔ in KPB (20 mM, pH 7.2) containing NaCl (0.15 M) was mixed with an appropriate amount of 8 M urea in the same buffer in a stopped-flow apparatus, and the absorptions were monitored at 616 or 658 nm. Absorption changes were fitted with single or, if necessary, biexponential models. Absorption increases are indicated by a plus sign, and decays are indicated by a minus sign.

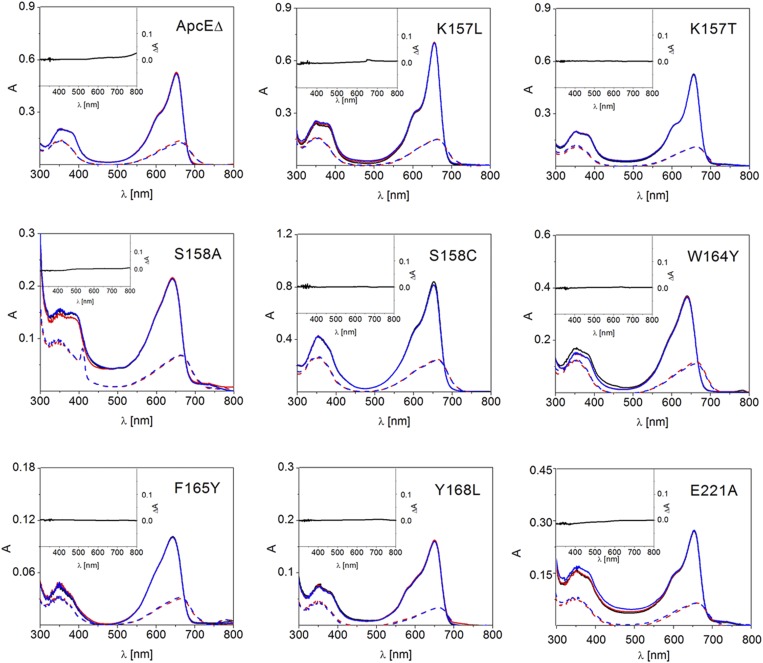

Taken together, ApcEΔ combines the apoprotein structure of light-harvesting phycobiliproteins (Fig. S1) with the chromophore structure of PCB-containing sensory photoreceptors (Fig. 3). However, unlike the case in the latter, the chromophore is photochemically inactive in ApcEΔ (Fig. S2) and shows strong fluorescence (Table S2). This inertness in ApcEΔ is rationalized by the tight packing between helices E, F, and F′ (Fig. 5) that impedes the photoisomerization that is characteristic for sensory biliproteins. A bidentate hydrogen bond (3.0 Å) of the guanidinium group of Arg160 with the C123-carboxylate of PCB fixes ring C. There is no H-bond partner around ring D, but it is held, as in a vise, by neighboring residues. On one side, ring D is in contact with Trp164 (3.8 Å), the C17-methyl with Asp161 (3.8 Å), and the C18-ethyl with Tyr168 (3.6 Å). On the opposite side, ring D contacts Leu188 (3.3 Å), C17-methyl contacts Phe165 (3.4 Å), and C18-ethyl contacts Asn184 (3.7 Å) (Fig. 5). These residues were mutated individually (Fig. 5 and Table S2). Mutations of Asp161 inhibit chromophorylation. The spectra of variants R160A, W164Y, F165Y, and L188G are markedly affected, whereas the spectra of R160S, W164A, Y168L, and N184G changed only slightly. These data support the view that tight fitting of PCB by the joint action of these residues contributes to the fluorescence and the extreme spectral red shift of PCB in ApcEΔ.

Fig. S2.

Silence of reversible photochemistry of ApcEΔ and its variants. Samples were reconstituted in E. coli (Table S5), purified with Ni2+ affinity chromatography, and then kept in KPB (20 mM, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.5). These absorption (A) spectra were measured under native conditions (solid lines) or darkly denatured conditions (dashed lines), respectively, before irradiation (black lines), after irradiation at 600 nm (blue lines), and after irradiation at 650 nm (red lines) at a light intensity of 30 μmol⋅m−2⋅s−1 for 10 min. The difference spectra were inserted. The denaturation was realized with 8 M acidic urea (pH 1.5) for 15 min.

Working Hypothesis for the Bifurcation of Energy Transfer in LCM.

Both propionic carboxyl groups as well as the ring D oxygen of ApcEΔ are near the protein surface. This geometry would locate the chromophore in the periphery of the heterohexamer containing LCM. The location of the loop deleted in ApcEΔ at the base of the PBS near PSII provides, furthermore, good evidence that this geometry also brings the chromophore close to PSII. Thus, the energetics and distance requirements are met for Förster transfer of the energy harvested by hundreds of chromophores onto the reaction center (4, 5). However, focusing the energy also poses the danger of photodamage, particularly to PSII. Nonphotochemical quenching by carotenoids has been evolved as a universal mechanism for thermalization of excess excitation energy (32). In cyanobacteria, this quenching involves excitation transfer to OCP that is itself activated by light: Activated OCP then associates with the PBS core and LCM. Energy transfer from LCM to the carotenoid is, however, more demanding (33). Dexter (electron exchange) transfer can be excluded, because the 4-keto-carotenoid is buried within activated OCP (30). The intense absorption of the carotenoid, however, makes energy transfer possible from LCM by a Förster process. This mechanism is effective over larger distances but requires spectral matching of donor and acceptor. The overlap between the LCM fluorescence (λmax = 670 nm) and the absorption of resting OCP (λmax = 495 nm) is only very small. It becomes better, however, in the activated state, where the band shifts to the red and broadens considerably, with the low-energy wing extending to >650 nm (33). If these changes were accompanied by a blue shift of the LCM fluorescence, the situation would become even more favorable, and such a shift is expected if Trp164 rotates from the “π-π–on” to the “π-π–off” state (discussed above). Furthermore, this shift would reduce the overlap integral for energy transfer to PSII. The structural change of OCP after activation (30) results in binding to the LCM-containing heterohexamer of the core (34), thereby bringing the red-shifted carotenoid closer to LCM. If this binding were also to induce the blue shift of the PCB chromophore, the combined effects of reduced distance, improved spectral overlap with the quenching OCP chromophore, and reduced spectral overlap with PSII would provide a mechanism for diverting energy flow away from PSII to the quenching carotenoid. Obviously, this working hypothesis poses many questions, including the controversial function of the loop deleted in AcpE (7), but it is consistent with known and new results.

Autocatalytic Chromophorylation.

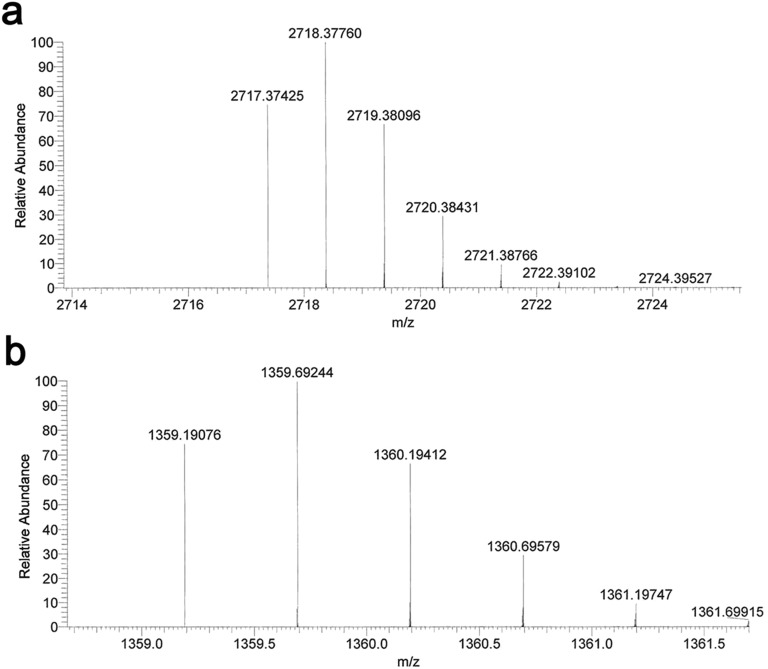

ApcE resembles the sensory biliproteins also in the autocatalytic chromophore attachment. Despite the different orientation of ring A in the ZZZssa geometry, C31 is R-configured as in all allophycocyanins (Fig. 3). The C31 distance to S of Cys196 is 1.5 Å, identifying the covalent attachment of PCB chromophore at this Cys, which agrees with the spectroscopic characteristics under denaturing conditions (Fig. 1). The close Ser158 (O-C3 = 3.3 Å and O-C31 = 4.2 Å) on the chromophore face opposite to Cys196 (Fig. 5) may be involved in the autocatalytic chromophore attachment. In (allo)phycocyanins, the position corresponding to Ser158 of ApcE is occupied by the chromophore-binding Cys84 and proper chromophore attachment is catalyzed by lyases (35). The necessary rotation of ring A for accommodating this bond yields the ZZZasa chromophore, whereas in ApcE, binding to Cys196 located at the opposite face results in the ZZZssa geometry. An S158A variant almost lost PCB-binding capacity, whereas S158C was twice as active in generating PCB-binding product as the WT (Table S2). However, neither C196S nor S158C/C196S bound PCB covalently (Table S2), indicating that S158C still maintains the genuine binding site of C196, which is verified from trypsin digests and MS characterization of the isolated PCB-peptide (Fig. S3). The finding highlights the importance of hydroxyl or sulfhydryl groups for autocatalytic chromophore binding to Cys196. It is reminiscent of Thr93 in the equally autocatalytically binding cyanobacteriochrome AnPixJ (16) and of Ser161, Asp163, and Tyr65 in the acid-catalyzed nucleophilic Michael addition catalyzed by CpcT lyase (36).

Fig. S3.

MS of the PCB chromopeptide. PCB-ApcEΔ-S158C was digested with trypsin, and the isolated peptides were then assayed using HPLC-MS. The chromopeptide of EIIENAC196(PCB)SGEATIVALQEIK was measured at 2,718.4 for [M + H]+ (A, calculated at 2,717.1 m/z) and at 1,359.7 for [M + 2H]2+ (B, calculated at 1,358.5 m/z), respectively.

Extreme Red-Shifted LCM Is Unrelated to Aggregation.

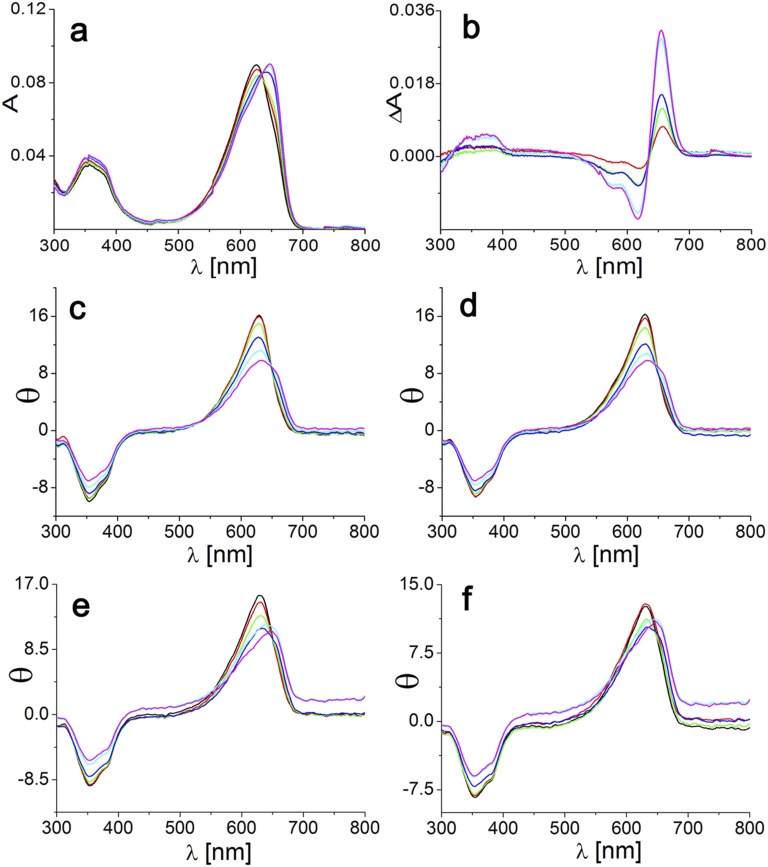

Contrary to other phycobiliproteins, the chromophore–protein interactions in the PCB pocket of LCM do not originate from adjacent subunits but are inherent to the binding subunit (Fig. 5). Accordingly, ApcEΔ retains the native-like red shift (Fig. 1) in the presence of 4 M urea that dissociates phycobiliprotein trimers to monomers (ref. 6 and references therein). This result is corroborated by other chromophorylated ApcE constructs: Almost all of them form homodimers in solution (22) (Table S2) yet retain the extreme red shift that is characteristic for LCM. These constructs include a variant with single-site mutation of Asp41 on the surface of helix Y that is involved in heterodimer formation [deletion of amino acids 38–39 and 41–42 in ApcEΔΔ resulted in blue-shifted trimeric aggregates (Fig. 2, Fig. S4, and Table S2), which form red-shifted dimers upon addition of urea or at elevated temperatures (Tables S2 and S3 and Fig. S5)]. Even monomers, obtained by complete deletion of helices X and/or Y (Δ1–35 or Δ1–49), retain most of the red shift (λmax,absorption = 650 nm) compared with phycobiliprotein monomers carrying the same PCB chromophore (λmax,absorption < 620 nm) (37). These monomers comprising only the globin fold underwent the urea-induced dimerization that has been reported for other globins (38, 39), but the aggregation-induced red shift is minimal (∼2 nm). Taken together, these studies rule out intersubunit interactions as well as exciton coupling in dimers as the origin of the red shift.

Fig. S4.

(A) Absorption (A, solid line), fluorescence (Fem, dashed line), and CD (θ, dotted line) spectra of native PCB-ApcEΔΔ in KPB. (B) Absorption spectra of PCB-ApcEΔΔ in 8 M acidic urea (pH 1.5). (Inset) Zinc-induced fluorescence of the SDS/PAGE indicating covalently attached chromophores. Samples were reconstituted in E. coli (Table S5), purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography, and then dialyzed against KPB (20 mM, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.2) containing 0 M (thick lines) and 4 M (thin lines) urea. Emission spectra were obtained by excitation at 580 nm for PCB.

Fig. S5.

Absorption (A) and difference absorption (B) changes of PCB-ApcEΔΔ with time at 0 (black lines), 2 (red lines), 4 (green lines), 8 (blue lines), 16 (cyan lines), and 60 (magenta) min in KPB (20 mM, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.2) containing 2 M urea. The spectral changes in KPB containing 1 M urea were similar but smaller. The difference absorption spectra were obtained by subtracting the absorption at 0 min from the one at the respective time. Reversible changes in the CD of PCB-ApcEΔΔ from 4 to 40 °C (C and E) and from 40 to 4 °C (D and F) in KPB containing 1 M urea (C and D) or 2 M urea (E and F) are shown. The black lines correspond to the case at 4 °C, red lines to the case at 8 °C, green lines to the case at 16 °C, blue lines to the case at 24 °C, cyan lines to the case at 32 °C, and magenta lines to the case at 40 °C. Samples were reconstituted in E. coli (Table S5), purified with Ni2+ affinity chromatography, and then kept in KPB (20 mM, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.2).

Excited State Dynamics.

The N-truncated constructs rendered ApcE accessible to time-resolved spectroscopy. Transient absorption measurements of all chromophorylated proteins [ApcEΔ, ApcEΔΔ, ApcE(50–240/Δ77–153), and ApcE(36–240/Δ77–153)] showed very similar three-exponential decay processes (Table S4). The longest lifetime (τ = 0.5–1 ns) corresponds to the S1 relaxation to the ground state, and it includes stimulated emission (λmax = 730 nm). This decay is about twice as fast as in full-length LCM (1, 29), in agreement with the reduced fluorescence quantum yield (0.06), indicating a less rigid chromophore pocket in the engineered constructs that all have deleted the loop near the chromophore binding site (22, 24) (Fig. 2). Quenching of LCM fluorescence has also been reported with OCP (29). It might be nonspecific (40) and/or dynamic, because OCP is associated with a site formed by two allophycocyanin trimers in the basal cylinders of the PBS core (34). The shortest component (∼5 ps) is most probably related to a vibrational relaxation and/or subsequent conformation relaxation. Its presence in monomers [ApcE(50–240/Δ77–153)] and long interchromophore distances in the dimers rule out exciton relaxation. Förster-type energy transfer can also be ruled out for the intermediate decay component (100–200 ps) because of its persistence in monomers. The strong (twofold) deuterium isotope effect on excitation at 660 nm would relate it to transient deprotonation and/or reprotonation in the excited state that accompanies photoisomerization in phytochromes. However, this process cannot be completed in LCM due to the tight packing of ring D, and we were unable to detect any reversible photochemistry via steady-state absorption spectra of ApcEΔ and its variants (Fig. S2).

Table S4.

Transient absorption spectroscopy

| Sample | τ1, fs | τ2, ps | τ3, ps | τ4, ps |

| PCB-ApcE(50–240/Δ77–153) in H2O | 77 | 4.2 | 176 | 754 |

| PCB-ApcE(36–240/Δ77–153) in H2O | 74 | 3.6 | 186 | 720 |

| PCB-ApcEΔΔ in H2O | 48 | 4.0 | 169 | 973 |

| PCB-ApcEΔ In H2O | 80 | 3.5 | 99 | 600 |

| PCB-ApcEΔ in D2O | 77 | 5.3 | 201 | 892 |

Time constants of PCB-ApcEΔ and its variants in KPB (20 mM, pH 7.0). The excitation pulse was at 660 nm with ∼10-nm FWHM. τ1 is considered a coherent artifact.

Concluding Remarks.

Engineering of the terminal PBS emitter, LCM, yielded soluble N-terminal constructs that retain the autocatalytic binding of the chromophore (22–24) and the spectroscopic characteristics of the full-length protein (Fig. 1 and Table S2). These constructs could be crystallized and permitted detailed studies in solution. The comparison of monomers with dimers excludes exciton coupling as the origin of the red-shifted absorption and fluorescence. Based on the structure, we ascribe the red shift to the unusual phytochrome-like ZZZssa geometry of the inherently flexible chromophore, and its fluorescence to a rigid fixation that inhibits photochemistry of the PCB chromophore. The flexibility seen by differences between chains A and B in the unit cell, combined with spectroscopic data, led us to propose a model for the bifurcation of energy transfer from LCM that is relevant for safeguarding the harvested light energy. As the missing link in structural studies, this work completes the domain structure of the complex LCM protein. In addition to its relevance for understanding light harvesting by PBS, it will allow studying interactions with other phycobiliproteins, photosynthetic membrane components, and OCP, with or without the loop (amino acids 77–153) present. Last but not least, this work provides access to a novel class of small fluorescence labels with strong emissions in the far-red to near-IR spectral region.

Materials and Methods

Cloning and Expression.

All genetic manipulations (Table S1) were carried out according to standard protocols (41). Plasmid pET30-apcE(1–240) and pET30-apcE(1–240/Δ77–153) for ApcE variants of Nostoc sp. PCC7120 and pACYC-ho1-pcyA for PCB have been reported previously (22). For overexpression, pET-derived expression vectors for ApcE variants were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) (Novagen) containing a PCB-generating plasmid (pACYC-ho1-pcyA) (22) (Table S5).

Table S5.

Plasmids used

| Antibiotic resistance | pACYCDuet derivative | pET30 or pET28 derivatives |

| Kanamycin | pET-apcE(1–240/Δ87–130) | |

| pET-apcE(1–240/Δ77–153) | ||

| pET-apcE(20–240/Δ87–130) | ||

| pET-apcEΔ | ||

| pET-apcEΔΔ | ||

| pET-apcE(36–240/Δ77–153) | ||

| pET-apcE(50–240/Δ77–153) | ||

| pET-E39A | ||

| pET-L40S | ||

| pET-D41A | ||

| pET-E42A | ||

| pET-L43S | ||

| pET-E39A/E42A | ||

| pET-R53A | ||

| pET-I75A | ||

| pET-N154R | ||

| pET-A156Q | ||

| pET-K157L | ||

| pET-K157T | ||

| pET-S158A | ||

| pET-S158C | ||

| pET-S158C/C196S | ||

| pET-R160A | ||

| pET-R160S | ||

| pET-D161A | ||

| pET-D161H | ||

| pET-W164A | ||

| pET-W164Y | ||

| pET-F165Y | ||

| pET-Y168L | ||

| pET-N184G | ||

| pET-L188G | ||

| pET-C196S | ||

| pET-A200F | ||

| pET-F216A | ||

| pET-E221A | ||

| Chloramphenicol | pACYC-ho1-pcyA |

The pACYCDuet and pET30 or pET28, from Novagen, are T7 promoter expression vectors. The pACYCDuet is designed to coexpress two target proteins in E. coli. Using the two vector derivatives, together with compatible replicons and antibiotic resistance, three proteins could be coexpressed in the same cell, thereby generating the respective designed core-membrane–like variants in E. coli.

Protein Assay.

Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay (42), and SDS/PAGE was performed with the buffer system of Laemmli (43). Proteins were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, and those proteins containing chromophores were identified by Zn2+-induced fluorescence (44). The oligomerization state of ApcEΔ variants was determined via gel filtration on a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare).

Spectral Analyses.

Covalently bound chromophores were quantified after denaturation with acidic urea (8 M, pH 1.5) by their absorption at 662 nm (PCB) using an extinction coefficient of 35,500 M−1⋅cm−1 (45). Fluorescence quantum yield, ΦF, was determined in potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), using the known ΦF = 0.27 of phycocyanin from Nostoc sp. PCC7120 (46) as a standard. Ultrafast spectroscopy was carried out using a setup previously described (47, 48). Time-resolved data were globally analyzed using the Glotaran software package (49).

Crystallization and Data Collection.

Purified ApcEΔ (10 mg/mL) was crystallized under the condition containing 0.1 Hepes (pH 7.0), 29% (wt/vol) PEG400, and 0.2 M NaCl. ApcEΔ-Se was prepared according to the standard protocol (50) via the ApcEΔ assembly system. Purified ApcEΔ-Se (7.5 mg/mL) was crystallized against the reservoir solution containing 16% up to 26% (wt/vol) PEG3350 and 0.25 M sodium thiocyanate (NaSCN).

All diffraction data were processed with the XDS program package and scaled using XSCALE (51). The crystal structure was determined by the single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) method (52) using the Se-substituted crystals. The initial model was obtained using molecular replacement SAD (MRSAD) on the Auto-Rickshaw server (53). The structure of native ApcEΔ was determined by molecular replacement [Phaser in CCP4 (54) using ApcEΔ-Se as a starting model]. In both the native and Se structure, the chromophore was fitted manually in the electron density using Coot (55). Structures were refined by iterative cycles of manual refinement using Coot and Refmac5 (56) from the CCP4 suite (54). Data refinement statistics and model content are summarized in Table 1. The structures of ApcEΔ and the Se derivative were deposited at the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 4XXI and 4XXK, respectively.

Materials and methods are detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Cloning and Expression.

All genetic manipulations were carried out according to standard protocols (41). Plasmid pET30-apcE(1–240) and pET30-apcE(1–240/Δ77–153) for ApcE variants of Nostoc sp. PCC7120 and pACYC-ho1-pcyA for PCB have been reported previously (22). To facilitate purification via Ni2+-affinity chromatography as well as subsequent crystallization, apcE(1–240/Δ77–153) was amplified by PCR using primers P1 and P2, and ligated into the expression vector pET30 (Novagen) via restriction sites NdeI and XhoI (Fermentas) for C-terminal fusion to a His6-tag. Then, apcE(20–240/Δ77–153) (i.e., apcEΔ) was generated from apcE(1–240/Δ77–153) via PCR with primers P3 and P4, and apcE(20–240/Δ38–39/Δ41–42/Δ77–153) (i.e., apcEΔΔ) was mutated from apcEΔ via PCR with primers P5 and P6 (Table S1). The apcE(36–240/Δ77–153) and apcE(50–240/Δ77–153) were amplified from apcEΔ via PCR with primers P7–P10 and ligated into the expression vector pET28 (Novagen) via restriction sites NcoI and XhoI (Fermentas) for fusing a C-terminal His6-tag. To analyze the structural effects on energy transfer of the truncated LCM, site-directed variants were constructed using a MutanBEST kit (TaKaRa) or QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with primers (Table S1). N154R, S158C, R160S, W164A, and F216A of apcEΔ, and L40S, L43S, and A156Q of apcE(20–240/Δ87–130) were purchased from Sangon Biotech Company.

For overexpression, pET-derived expression vectors for ApcE variants were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) (Novagen) containing a PCB-generating plasmid (pACYC-ho1-pcyA) (Table S5). The doubly transformed cells were cultured at 16 °C in LB supplemented with kanamycin (20 μg/mL) and chloromycetin (17 μg/mL). After induction with isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (1 mM) for 16 h, the cells were collected by centrifugation. After purification via Ni2+-affinity chromatography (22), the sample was dialyzed twice against potassium phosphate buffer (KPB; 20 mM, pH 7.5) containing 50 mM NaCl and 5 mM EDTA, subsequently loaded onto an ion exchange column (HiPrep DEAE FF 16/10; GE Healthcare), and eluted with the same buffer at a flow rate of 1 mL⋅min−1 and a linear gradient of 10 mM NaCl per minute to remove the nonchromophorylated apoprotein.

Protein Assay.

Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay (42) and calibrated with BSA, and SDS/PAGE was performed with the buffer system of Laemmli (43). Proteins were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue and those proteins containing chromophores were identified by Zn2+-induced fluorescence (44). To isolate the PCB-bound peptides, the purified chromophorylated ApcEΔ variants (2 mg/mL) were digested with trypsin (0.5 mg/mL; Sigma–Aldrich) in 5 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0) for 16 h. After centrifugation, the isolated peptides were analyzed by HPLC-MS.

Spectral Analyses.

All chromoproteins were investigated by UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy (DU 800; Beckman-Coulter). Covalently bound chromophores were quantified after denaturation with acidic urea (8 M, pH 1.5) by their absorptions at 662 nm (PCB) using an extinction coefficient of 35,500 M−1⋅cm−1 (45). Fluorescence spectra were recorded at room temperature with an LS 55 (PerkinElmer) or Cary Eclipse (Varian) spectrofluorimeter. Fluorescence quantum yields, ΦF, were determined in KPB (pH 7.2), using the known ΦF = 0.27 of phycocyanin from Nostoc sp. PCC7120 (46) as a standard. Ultrafast spectroscopy was carried out using a setup previously described (47, 48). Excitation energy at 660 nm (for PCB chromophores) was adjusted to 50 nJ per pulse. An interference filter (spectral width ∼ 10 nm) was used to narrow the wavelength. The spot size was ∼0.1 mm2. Time-resolved data were globally analyzed using the Glotaran software package (49). CD spectra were recorded with a model MOS-500 spectropolarimeter (Bio-Logic) equipped with a stopped flow unit.

Oligomerization Analysis.

To determine the oligomerization state of ApcEΔ variants under various conditions, the proteins were first purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography. A portion (0.2 mL) of the eluate was loaded on a Superdex 75 preparative grade column (30 × 1.0 cm) (GE Healthcare) and developed (0.5 mL⋅min−1) with KPB (20 mM, pH 7.5) containing NaCl (0.15 M) or an additional 4 M urea. The apparent molecular mass was determined by comparison with a marker set (12–66 kDa).

Crystallization and Data Collection.

Initial screening for crystallization conditions of the purified ApcEΔ was performed using 96-well sitting drop plates (Corning 3553) and commercial screening kits from Nextal (Qiagen). Crystallization droplets were prepared by mixing 100 nL of protein solution [10 mg/mL in 20 mM KPB (pH 7.5), 0.3 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA] with 100 nL of reservoir solution. They were equilibrated against 50 μL of the reservoir solution and stored at 285 K. The best diffracting crystals grew under conditions containing 0.1 Hepes (pH 7.0), 29% (wt/vol) PEG400, and 0.2 M NaCl within 2 wk to a final size of 40 × 55 × 70 µm3. Se-substituted ApcEΔ (ApcEΔ-Se) was prepared according to the standard protocol (50) via the ApcEΔ assembly system. After purification, ApcEΔ-Se [7.5 mg/mL in 20 mM KPB (pH 7.5), 0.1 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA] was crystallized against the reservoir solution containing 16% up to 26% (wt/vol) PEG3350 and 0.25 M sodium thiocyanate (NaSCN) using 72-well microbatch plates (Terasaki). Drops were prepared by mixing 1 μL of the protein solution with 1 μL of the corresponding precipitant, covered with mineral oil (Sigma–Aldrich), and stored at 285 K. The best diffracting crystals grew under conditions containing 16% (wt/vol) PEG3350 and 0.25 M NaSCN within 2 wk to a final size of 100 × 50 × 20 µm3.

To cryoprotect ApcEΔ crystals, the crystallization drops were covered with mineral oil before a single crystal was retrieved with a litho-loop and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Native and single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) X-ray diffraction data were collected from a single crystal in each case on beamline P13 [European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Deutsches Elektronen Synchrotron, Hamburg, Germany (for ApcEΔ)] and beamline ID29 [European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France (for ApcEΔ-Se)]. All diffraction data were processed with the XDS program package and scaled using XSCALE (51). The crystal structure was determined by the SAD method (52) using the Se-substituted crystals. The initial model was obtained using molecular replacement SAD on the Auto-Rickshaw server (53). The structure of native ApcEΔ was determined by molecular replacement [Phaser in CCP4 (54) using ApcEΔ-Se as a starting model]. In both the native and Se structures, the chromophore was fitted manually in the electron density using Coot (55). Structures were refined by iterative cycles of manual refinement using Coot and Refmac5 (56) from the CCP4 suite (54). Data refinement statistics and model content are summarized in Table 1. The structures of ApcEΔ and the Se derivative were deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the following accession codes: 4XXI and 4XXK, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory Outstation (Deutsches Elektronen Synchrotron) for their friendly help during data collection at beamline P13 and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility for provision of synchrotron radiation facilities for data collection at beamline ID29. We are grateful for expert discussion with Dr. Sandeer Smits (Institute of Biochemistry, Universität Düsseldorf). We also thank Stefanie Kobus for excellent technical assistance. The expert support of the chromatography unit of the Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Chemical Energy Conversion and the MS unit of the MPI für Kohlenforschung is greatly acknowledged. H.S. and K.-H.Z. (Grant 31110103912 to H.S. and K.-H.Z. and Grants 21472055 and 31270893 to K.-H.Z.) were supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. K.T. is the recipient of a grant from the China Scholar Council. W.G. received financial support from the Max Planck Society. Y.H. and J.T.M.K. were supported by the Chemical Sciences Council of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO-CW) through a VICI grant (to J.T.M.K.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 4XXI and 4XXK).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1519177113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gindt YM, Zhou J, Bryant DA, Sauer K. Core mutations of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 phycobilisomes: A spectroscopic study. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1992;15(1-2):75–89. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(92)87007-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong C, et al. ApcD is necessary for efficient energy transfer from phycobilisomes to photosystem I and helps to prevent photoinhibition in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787(9):1122–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gantt E, Grabowski B, Cunningham FX. In: Light-Harvesting Antennas in Photosynthesis. Green B, Parson W, editors. Kluwer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2003. pp. 307–322. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang L, et al. Structural organization of an intact phycobilisome and its association with photosystem II. Cell Res. 2015;25(6):726–737. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu H, et al. Phycobilisomes supply excitations to both photosystems in a megacomplex in cyanobacteria. Science. 2013;342(6162):1104–1107. doi: 10.1126/science.1242321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng PP, et al. The structure of allophycocyanin B from Synechocystis PCC 6803 reveals the structural basis for the extreme redshift of the terminal emitter in phycobilisomes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2014;70(Pt 10):2558–2569. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714015776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ajlani G, Vernotte C. Deletion of the PB-loop in the L(CM) subunit does not affect phycobilisome assembly or energy transfer functions in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6714. Eur J Biochem. 1998;257(1):154–159. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2570154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bald D, Kruip J, Rögner M. Supramolecular architecture of cyanobacterial thylakoid membranes: How is the phycobilisome connected with the photosystems? Photosynth Res. 1996;49(2):103–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00117661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capuano V, Thomas JC, Tandeau de Marsac N, Houmard J. An in vivo approach to define the role of the LCM, the key polypeptide of cyanobacterial phycobilisomes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(11):8277–8283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lundell DJ, Yamanaka G, Glazer AN. A terminal energy acceptor of the phycobilisome: The 75,000-dalton polypeptide of Synechococcus 6301 phycobilisomes--a new biliprotein. J Cell Biol. 1981;91(1):315–319. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.1.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piven I, Ajlani G, Sokolenko A. Phycobilisome linker proteins are phosphorylated in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(22):21667–21672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412967200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirilovsky D. Photoprotection in cyanobacteria: The orange carotenoid protein (OCP)-related non-photochemical-quenching mechanism. Photosynth Res. 2007;93(1-3):7–16. doi: 10.1007/s11120-007-9168-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schluchter WM, Bryant DA. In: Heme, Chlorophyll, and Bilins. Smith AG, Witty M, editors. Humana; Totowa, NJ: 2002. pp. 311–334. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anders K, Daminelli-Widany G, Mroginski MA, von Stetten D, Essen LO. Structure of the cyanobacterial phytochrome 2 photosensor implies a tryptophan switch for phytochrome signaling. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(50):35714–35725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.510461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mailliet J, et al. Spectroscopy and a high-resolution crystal structure of Tyr263 mutants of cyanobacterial phytochrome Cph1. J Mol Biol. 2011;413(1):115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narikawa R, et al. Structures of cyanobacteriochromes from phototaxis regulators AnPixJ and TePixJ reveal general and specific photoconversion mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(3):918–923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212098110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essen L-O, Mailliet J, Hughes J. The structure of a complete phytochrome sensory module in the Pr ground state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(38):14709–14714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806477105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glazer A. Phycobiliproteins —A family of valuable, widely used fluorophores. J Appl Phycol. 1994;6(2):105–112. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auldridge ME, Satyshur KA, Anstrom DM, Forest KT. Structure-guided engineering enhances a phytochrome-based infrared fluorescent protein. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(10):7000–7009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.295121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stadnichuk IN, et al. Site of non-photochemical quenching of the phycobilisome by orange carotenoid protein in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817(8):1436–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houmard J, Capuano V, Colombano MV, Coursin T, Tandeau de Marsac N. Molecular characterization of the terminal energy acceptor of cyanobacterial phycobilisomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87(6):2152–2156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang K, et al. A minimal phycobilisome: Fusion and chromophorylation of the truncated core-membrane linker and phycocyanin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817(7):1030–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biswas A, et al. Biosynthesis of cyanobacterial phycobiliproteins in Escherichia coli: Chromophorylation efficiency and specificity of all bilin lyases from Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(9):2729–2739. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03100-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao KH, et al. Reconstitution of phycobilisome core-membrane linker, LCM, by autocatalytic chromophore binding to ApcE. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1706(1-2):81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGregor A, Klartag M, David L, Adir N. Allophycocyanin trimer stability and functionality are primarily due to polar enhanced hydrophobicity of the phycocyanobilin binding pocket. J Mol Biol. 2008;384(2):406–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372(3):774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramachandran GN, Sasisekharan V. Conformation of polypeptides and proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 1968;23:283–438. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gindt YM, Zhou J, Bryant DA, Sauer K. Spectroscopic studies of phycobilisome subcore preparations lacking key core chromophores: Assignment of excited state energies to the Lcm, beta 18 and alpha AP-B chromophores. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1186(3):153–162. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stadnichuk IN, et al. Fluorescence quenching of the phycobilisome terminal emitter LCM from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 detected in vivo and in vitro. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2013;125:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leverenz RL, et al. PHOTOSYNTHESIS. A 12 Å carotenoid translocation in a photoswitch associated with cyanobacterial photoprotection. Science. 2015;348(6242):1463–1466. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa7234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marx A, Adir N. Allophycocyanin and phycocyanin crystal structures reveal facets of phycobilisome assembly. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1827(3):311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niyogi KK, Truong TB. Evolution of flexible non-photochemical quenching mechanisms that regulate light harvesting in oxygenic photosynthesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2013;16(3):307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berera R, et al. The photophysics of the orange carotenoid protein, a light-powered molecular switch. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116(8):2568–2574. doi: 10.1021/jp2108329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang H, et al. Molecular mechanism of photoactivation and structural location of the cyanobacterial orange carotenoid protein. Biochemistry. 2014;53(1):13–19. doi: 10.1021/bi401539w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schluchter WM, et al. Phycobiliprotein biosynthesis in cyanobacteria: Structure and function of enzymes involved in post-translational modification. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;675:211–228. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1528-3_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou W, et al. Structure and mechanism of the phycobiliprotein lyase CpcT. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(39):26677–26689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.586743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacColl R, Guard-Friar D. Phycobiliproteins. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwin F, Sharma YV, Jagannadham MV. Stabilization of molten globule state of papain by urea. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290(5):1441–1446. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Young LR, Dill KA, Fink AL. Aggregation and denaturation of apomyoglobin in aqueous urea solutions. Biochemistry. 1993;32(15):3877–3886. doi: 10.1021/bi00066a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jallet D, et al. Specificity of the cyanobacterial orange carotenoid protein: Influences of orange carotenoid protein and phycobilisome structures. Plant Physiol. 2014;164(2):790–804. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.229997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Plainview, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berkelman TR, Lagarias JC. Visualization of bilin-linked peptides and proteins in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1986;156(1):194–201. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glazer AN, Fang S. Chromophore content of blue-green algal phycobiliproteins. J Biol Chem. 1973;248(2):659–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cai YA, Murphy JT, Wedemayer GJ, Glazer AN. Recombinant phycobiliproteins. Recombinant C-phycocyanins equipped with affinity tags, oligomerization, and biospecific recognition domains. Anal Biochem. 2001;290(2):186–204. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berera R, van Grondelle R, Kennis JT. Ultrafast transient absorption spectroscopy: Principles and application to photosynthetic systems. Photosynth Res. 2009;101(2-3):105–118. doi: 10.1007/s11120-009-9454-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ravensbergen J, et al. Unraveling the carrier dynamics of BiVO4: A femtosecond to microsecond transient absorption study. J Phys Chem C. 2014;118(48):27793–27800. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snellenburg JJ, Laptenok SP, Seger R, Mullen KM, van Stokkum IHM. Glotaran: A Java-based graphical user interface for the R-package TIMP. J Stat Softw. 2012;49:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doublié S. Methods in enzymology. In: Carter C, Sweet R, editors. Macromolecular Crystallography, Part A. Vol 276. Academic; New York: 1997. pp. 523–530. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Panjikar S, Parthasarathy V, Lamzin VS, Weiss MS, Tucker PA. On the combination of molecular replacement and single-wavelength anomalous diffraction phasing for automated structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2009;65(Pt 10):1089–1097. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909029643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murshudov GN, et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]