Abstract

Background:

Determining the temporal variation and forecasting the incidence of smear positive tuberculosis (TB) can play an important role in promoting the TB control program. Its results may be used as a decision-supportive tool for planning and allocating resources. The present study forecasts the incidence of smear positive TB in Iran.

Methods:

This a longitudinal study using monthly tuberculosis incidence data recorded in the Iranian National Tuberculosis Control Program. The sum of registered cases in each month created 84 time points. Time series methods were used for analysis. Based on the residual chart of ACF, PACF, Ljung-Box tests and the lowest levels of AIC and BIC, the most suitable model was selected.

Results:

From April 2005 until March 2012, 34012 smear positive TB cases were recorded. The mean of TB monthly incidence was 404.9 (SD=54.7). The highest number of cases was registered in May and the difference in monthly incidence of smear positive TB was significant (P<0.001). SARIMA (0,1,1)(0,1,1)12 was selected as the most adequate model for prediction. It was predicted that the incidence of smear positive TB for 2015 will be about 9.8 per 100,000 people.

Conclusion:

Based on the seasonal pattern of smear positive TB recorded cases, seasonal ARIMA model was suitable for predicting its incidence. Meanwhile, prediction results show an increasing trend of smear positive TB cases in Iran.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Forecasting, SARIMA, Box-Jenkins, Iran

Introduction

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease that usually affects the lungs, although it can affect almost any part of the body (1–2) and has probably killed more human beings than any other disease in history. Even now in the 21st century, it is still one of the leading infections causing death, which kills at least 2 million people every year. TB can result following recent infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis or from reactivation of a former latent TB infection. Reactivation of disease is more common in countries that have controlled transmission, but new transmission is more common in endemic countries (3–4) such as Iran.

In the Millennium Development Objectives of the United Nations, accepted by 189 countries, in September 2000, countries agreed to achieve the objectives of reducing 50% of mortality from TB in comparison to 1990, stopping or reducing its incidence and prevalence until 2015 and dropping its incidence to less than one case per million population in 2050. The global plan to stop TB started its activity in January 2006 with strategies to control tuberculosis based on the dynamics of TB infection in societies (3, 5–7).

The incidence of smear positive TB in Iran was 6.9 to 7.6 per 100,000 people from 2005 to 2011. It seems like in Iran it is hard to achieve the predicted objectives due to problems such as proximity to Pakistan and Afghanistan that are one of the 22 highly infected world countries, proximity to Iraq which has been through instability and proximity to other countries such as Azerbaijan and Kyrgyzstan with high prevalence of multidrug-resistant TB (3, 6, 8).

Considering epidemiological transition, emerging of Multi Drug Resistant (MDR) and Extensively Drug Resistant (XDR) TB, spread of HIV/AIDS, and the high prevalence of diabetes mellitus new challenges in the control of tuberculosis should be expected (9–13). Therefore, in order to better control tuberculosis and allocate the available resources more efficiently, reviewing the temporal changes in disease incidence and predicting future trends is necessary (14).

In order to forecast tuberculosis occurrence and to study its temporal variations, different methods have been used in diverse studies (15–17), and based on data nature and evaluation, a certain model has been used in every study. For example, Zhang et al. compared the autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model and the generalized regression neural network (GRNN)-ARIMA combination model based on minimum mean square error in predicting tuberculosis incidence and determined the best option (16) or Li et al. used a time series decomposition analysis (X-12-ARIMA) to examine the seasonal variation in active TB cases nationwide from 2005 through 2012 in China (17). In addition, the incidence of tuberculosis changes by season and has shown peaks in spring and/or summer (11, 17–24).

Due to the afore mentioned reasons, in the millennium development objectives one of the aims is to stop or decrease the trend of TB by 2015 and eliminate it in 2050. Due to the absence of such research in Iran, the present study was designed in order to predict the incidence of TB using time series analysis and through selection of a suitable model.

Materials and Methods

In this time series study, data from April 2005 until March 2012 was inquired from the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education. The number of incident cases was aggregated in each month and 84 data points were created. In this study, spring includes April, May and June; summer includes July, August and September; autumn includes October, November and December; and January, February and March are the months of winter.

In order to compare the effect of season and month on registered cases of smear positive tuberculosis and the grading of sputum smear positive (the grading of sputum smear positive includes 1–9 bacilli defined as 1–9 AFB Per 100 immersion fields, 1+ defined as 10–99 AFB per 100 immersion fields, 2+ is defined as 1–10 AFB per 1 immersion fields, 3+ is defined as >10 AFB per 1 immersion fields) ANOVA was used. The differences among means were determined using post hoc tests (Turkey).

In order to determine the incidence of tuberculosis per 105 persons, the population denominator was calculated by using the results of the 2006 and 2011 census of Iran and considering the growth rate of 1.62% for the years 2005 and 2007 to 2010 and 1.29% for the years 2012 to 2015 (25). According to the 2006 and 2011 census, Iran had a population of 70,495,782 and 75,149,669 respectively (25).

Modeling and Evaluation

In time series analysis, Box Jenkins models using moving averages, auto regression and a combination of these two were used for forecasting. The steps in making Box Jenkins models includes; identifying the pattern, fitting a model and predicting. The ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average) models are a general class of models also known as Box-Jenkins models. The seasonal ARIMA model (SARIMA) is an expanded form of ARIMA, which allows seasonal factors to be reflected (26–27).

In order to examine the nature of data, tsplot time series graphs, ACF (autocorrelation function) and PACF (partial autocorrelation function) were initially depicted. Then the type of series was examined concerning stationary and non-stationary of the mean, variance and seasonal trend diagnosis. In addition, Bartlett test was used to study the variance equality and Kolmogorov-Smirnov was used to study data normality. Since this series had a trend and non-stationary conditions in its average, one stage differencing was used to remove the trend and create stationary.

To make the model, an experimental model was first recognized from ARIMA models using real data analysis. The unknown parameters were estimated using ACF and PACF graphs before differencing, after differencing, without seasonal effects and with seasonal effects. Then according to the confidence interval of residuals, ACF and PACF graphs of the prepared model, reviewing white noise series of the prepared model through Ljung -Box tests, results of t-test for reviewing equality of the given parameter with zero and goodness of fit models, a suitable model was selected.

After examining different models, ultimately the univariate SARIMA model was used for forecasting. The SARIMA model consists of auto-regression, difference, and moving average, and is represented as SARIMA (P, d, q) (P, D, Q) s, in which (p, d, q) represents the non-seasonal part, (P, D, Q) represents the seasonal part and S represents the length of the seasonality. The p, d, q and P, D, Q represents the auto-regression, difference, and moving average, respectively (26). Statistical calculations were performed by Minitab 16 and R software.

Several models can be obtained for various combinations of AR and MA individually and collectively. After the experimental model has been fit to the data, in order to test adequacy and performance of the constructed models, residual analysis was conducted and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Ljung–Box–Pierce chi-square statistics and t-test for examination of null hypothesis of the parameters equalization to zero were calculated. The AIC and BIC values from the forecasting models were compared and the one with the smallest value was selected as the final forecasting model.

Results

From April 2005 to March 2012, 74144 cases of tuberculosis were registered as part of the tuberculosis control program of Iran, in which 63569 cases were Iranian. Overall, 34012 cases (53.5%) had smear positive tuberculosis. The mean age of tuberculosis smear positive patients was 51.2±21.1 yr at the time of diagnosis. 52.2% of the smear positive tuberculosis patients were male. The smear positive patients were 3.4% 1–9 bacillus, 36.2% one positive, 23.5% two positive and 37% three positive.

The average recorded cases were 404.9 TB cases in a month with a standard deviation of 54.7. Among these 84 months, the minimum and maximum of incidence was 287 and 558 cases in November 2005 and May 2009 respectively. Bartlett’s Test revealed that the variances in this time series were equal (Bartlett test: 7.21, P = 0.8). In addition, according to the results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, the distribution of this time series had the prerequisite of normality (KS=0.08, P>0.15).

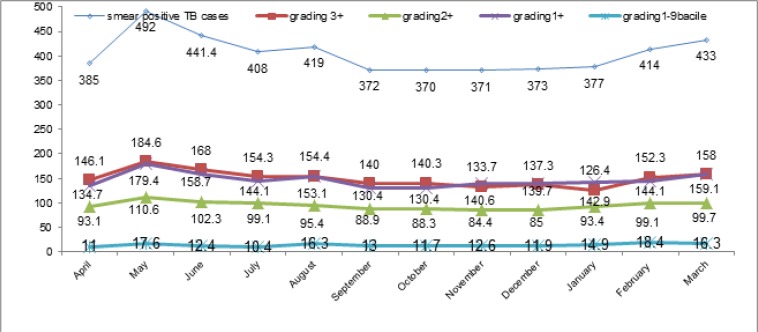

Based on Fig. 1, the average of maximum monthly smear positive TB incidences and the grading of sputum smear positive (excepting the grading 1–9 bacilli) in April 2005–March 2012, were recorded in May.

Fig. 1: Monthly average incidence of smear positive TB and its grading in Iran from April 2005 until March 2012.

ANOVA test showed that these differences were significant (P-value for smear positive TB, the grading of 1+ and 3+ was <0.001 and for the grading of 2+ was equal to 0.03). According to the Tukey post hoc test, there was a significant difference in smear positive TB monthly incidences between May and other months (April, July, September, October, November, December and January).

However, the differences observed in the number of monthly incidence of sputum smear with the grading of 1–9 bacile were not significant (P=0.5). Moreover, the average of smear positive TB seasonal incidence was 439.5±64.1 in spring, 399.9±45.3 in summer, 371.9±39.1 in autumn and 408.9±54.7 in winter. ANOVA showed significant differences between the seasonal incidence (P-value=0.001). According to the post hoc tests (Tukey), there was a significant difference between spring and autumn.

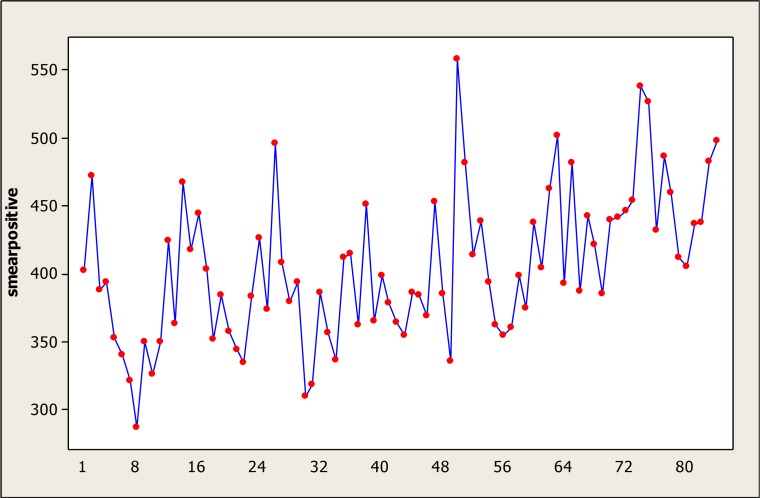

Time series graphs of raw data (Fig. 2) indicate that smear positive TB incidence has a seasonal pattern and this curve has a non-stationary trend.

Fig. 2: Time Series Plot of (actual data) smear positive TB incident cases per month from April 2005 until March 2012.

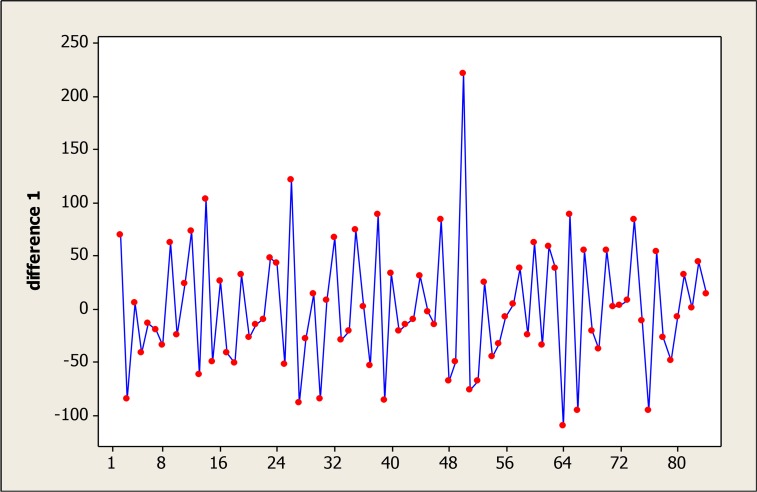

This time series reached the stationary conditions required for fitness of Box-Jenkins models after one differencing step on the original data and one seasonal differencing step (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: The time series after transforms using one stage difference.

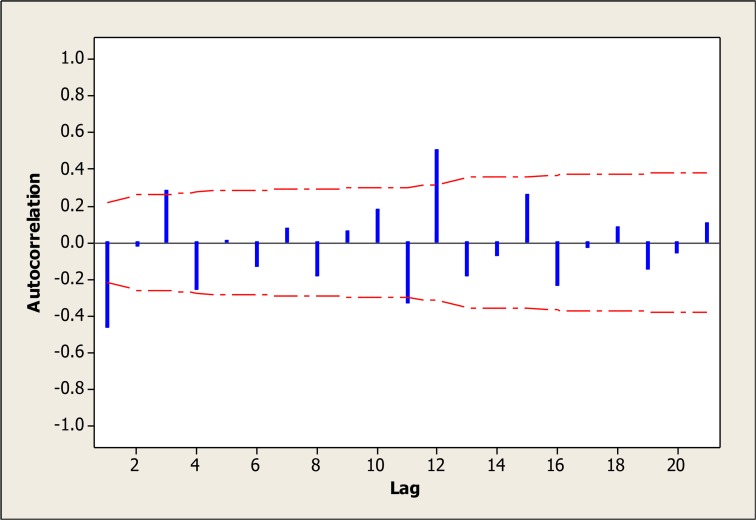

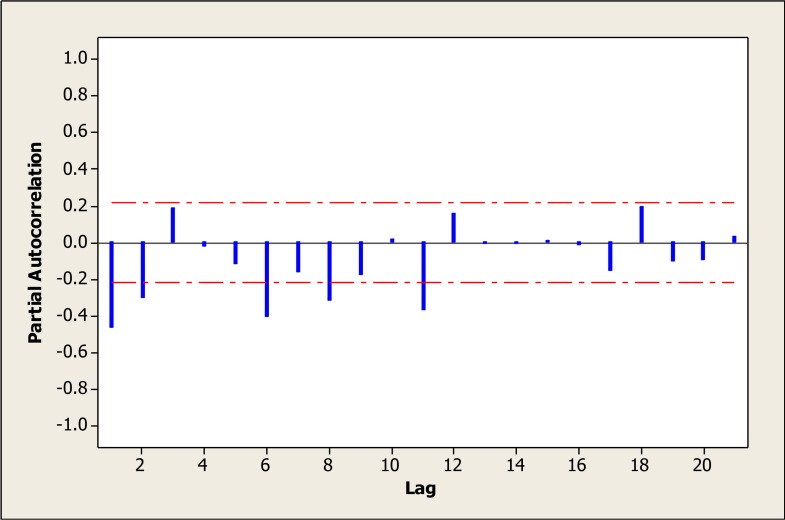

Therefore the amount of 1 was considered for the parameters d and D. According to the ACF graph, the parameters q and Q were more likely to be 1 (Fig. 4 and 5). However, different amounts of parameters were tested (Table 1). Various levels of non-seasonal ARIMA, were also examined concerning various levels of p, d and q and according to model evaluation indexes, none of them was suitable. Thus, adding the seasonal parameters of “P, D and Q” was strongly suggested.

Fig. 4: Autocorrelation plot after one stage difference.

Fig. 5: Partial autocorrelation plot after one stage difference.

Table 1: Test results comparing the adequacy and performance of the constructed models.

| Model type | Residuals plot | Ljung-Box (lag 12) | Goodness of fit of different models | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACF | PACF | Chi-Square | P | AIC | BIC | |

| SARIMA(0,1,1)(0,1,1)12 | NS | NS | 13.3 | 0.1 | 12.027 | 7.027 |

| SARIMA(1,1,1)(1,1,1)12 | NS | NS | 9.8 | 0.2 | 15.999 | 6.999 |

| SARIMA(2,1,1)(0,1,1)12 | NS | NS | 12.8 | 0.08 | 15.993 | 6.993 |

| SARIMA(0,1,2)(0,1,2)12 | NS | NS | 11.2 | 0.1 | 15.999 | 6.999 |

Despite the parameter estimations we made based on the ACF and PACF graphs, in order to find the best fit, 16 different models were evaluated, 4 models were more appropriate according to the ACF, PACF, reviewing white noise series by using Ljung -Box tests and results of t-test for reviewing equality of the given parameter with zero. The goodness of fit of these parameters has been shown in Table 1.

The best model with suitable parameters was selected based on minimum of BIC and AIC. Among these four models, SARIMA (0,1,1)(0,1,1)12 was selected as the most adequate and qualified model for prediction.

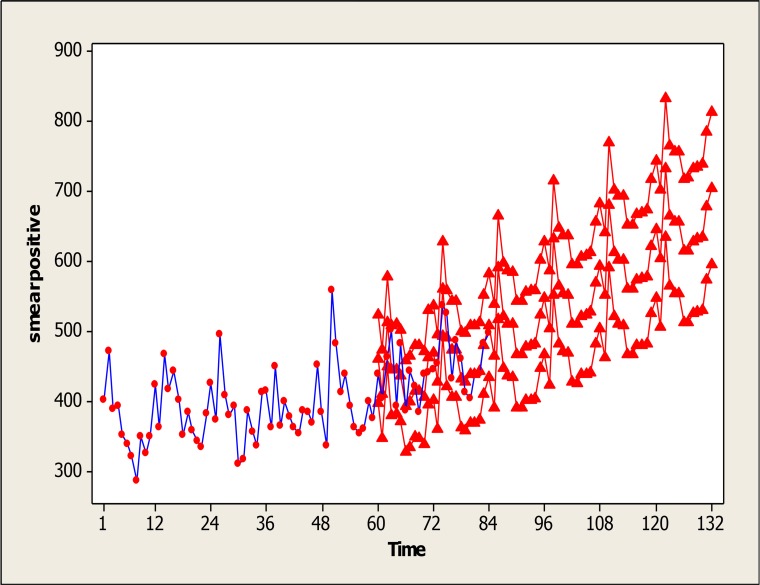

Using this selected model SARIMA (0,1,1)(0,1,1)12, prediction was made for the next 48 months (April 2012–2015). The results are shown in Fig. 6. Months 1 to 84 are real data, while months 85 to 132 are predicted. This graph also shows that the confidence interval of the predicted levels is narrow and shows high adequacy of this model for prediction.

Fig. 6: Observed and predicted monthly cases of smear positive TB in Iran from April 2005 until March 2015.

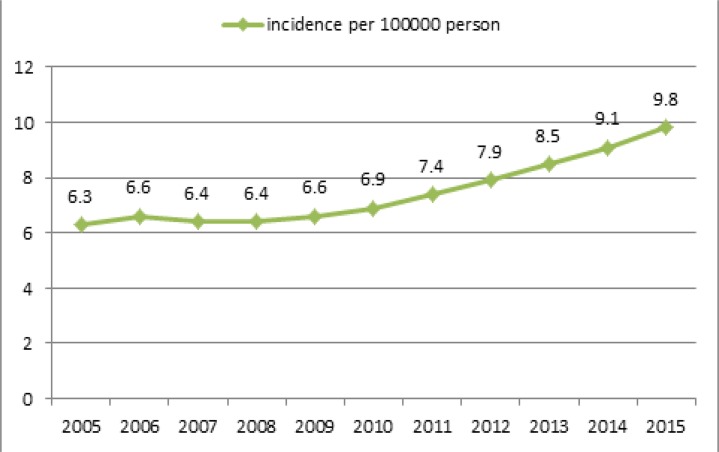

Based on real data and predictions, TB incidence was calculated from 2005 to 2015 per 100,000 people. Its incidence from April 2005 to March 2012 was determined according to real data, while its incidence for years April 2012–2015 was based on prediction. Based on real data, smear positive incidence varied from 6.3 in 100,000 in 2005 to 7.4 in 2011; its incidence for 2015 was predicted to be 9.8 per 100,000 people (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7: The incidence of smear positive TB in Iran, based on real data and predictions.

Discussion

The present study indicated that the best forecasting for smear positive TB incidence was possible with SARIMA (0, 1, 1) (0, 1, 1)12. Smear positive TB incidence in 2015 is predicted to be 1.5 times its incidence in year 2005. The smear positive TB incidence peak in Iran is in spring and in May. In addition, the maximum incidence according to the grading of sputum smear positive with 3+, 2+ and 1+ is also in May.

Yi et al. applied seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models in order to predictive the incidence of tuberculosis in China. The model parameters were estimated using the conditional least squares method. The model was appraised by AIC, BIC and white noise residuals. Moreover the chi square test confirmed the adequacy of SARIMA (0, 1, 1) (0, 1, 1)4 (28). Permanasari et al. investigated the performance of six different forecasting methods, including linear regression, moving average, decomposition, ARIMA, Neural Network and Holt-Winter’s for monthly tuberculosis data prediction and showed that the most appropriate model was ARIMA (29). Zhang et al. investigated two models of ARIMA and (GRNN)-ARIMA in prediction of tuberculosis incidence. The time series of tuberculosis shows a gradual secular decline and a striking seasonal variation. Ultimately, The ARIMA (2,1,0) × (0,1,1).12 model was selected from several plausible ARIMA models. They reported that the mean absolute error and mean absolute percentage error of the hybrid model were less than the ARIMA model (16). Other prediction studies with non-time series methods on tuberculosis data have been conducted as well, such as a study in Spain (18) with mathematical modeling on the registered cases of tuberculosis from 1971 until 1996, which has predicted the pattern for tuberculosis incidence and showed increases in the incidence. The incidence of pulmonary tuberculosis in Iran has a seasonal trend (30) and a study from the Mazandaran Province of Iran has reached similar results (31).

Results of the present study match a study in Spain, which predicted increases in TB cases. Considering the cyclic pattern of TB, time series analysis models are probably the most suitable to examine the trend and to predict TB incidence. As mentioned in the results of other studies, seasonal ARIMA model was more efficient than other time series analysis models in terms of predicting TB; one of its principal advantages is its capability to remove easily irregular variations and seasonal factors. The seasonal ARIMA model or SARIMA model is an expanded form of ARIMA, which allows seasonal factors to be reflected (26).

Factors such as the increased prevalence of diabetes, HIV/AIDS infections, addiction and smoking due to their suppressive effects on the immune system have contributed to increases in the prevalence of smear positive tuberculosis. According to a recent systematic review, people with diabetes had approximately three times the risk of developing TB disease as people without it (32). Factors that can activate latent tuberculosis are HIV/AIDS, immunosuppressive drugs such as corticosteroids, silicosis, air pollution, smoking, alcoholism, addiction and diabetes mellitus (12, 13, 33).

The global burden of diabetes is rising and the prevalence is estimated to reach 438 million by 2030. Probably more than 80% of the adult cases will be in newly developed or developing countries (13).

Due to the high prevalence of diabetes mellitus in Iran and its comorbidity with tuberculosis, an increase in the number of smear positive tuberculosis cases is expected in Iran. According to our results, the peak of smear positive TB incidence in Iran is in spring and May. Among the research done in other countries, the peak of tuberculosis in Hong Kong (20) was summer, in America (24) was spring and autumn and in Taiwan (22) and Ireland (23) was spring and summer. Also in the north of India, the peak of tuberculosis was spring and summer, but a seasonal pattern was not seen in the south of India (19). The peak was in spring and summer, but this peak was different in different countries and was probably affected by climate. In this study, we showed that the increase of smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis in Iran starts in the second month of winter (February) and reaches its peak in May. However, between February and May, patient detection decreases considerably in April (the first month of spring). This situation is probably due to the closing of the health centers in about half of the days in April due to Iranian New Year holidays. As tuberculosis is a chronic disease and people can tolerate the disease symptoms, they probably visit the clinics later and this is can be one main reason for the increased registered cases in May.

In the present study, the peak of detecting pulmonary tuberculosis patients with 2+ and 3+ sputum smears was in spring. Therefore, there is a possibility that disease transmission happens more frequently in winter, but because of the latent period, the diagnosis happens in spring. In addition, the disease, which manifests with coughing etc. might be mistaken with other common winter diseases and viral diseases by physicians; and this may also contribute to a later diagnosis in winter. There are several hypotheses about the reason for the seasonal pattern of tuberculosis. One of the hypotheses is that due to cold weather, and confined spaces transmission happens in winter and eventually after passing the latency period, the presentation of symptoms and diagnosis of the disease happens in spring (34–35). In addition, decrease in vitamin D and sunlight significantly increases the incidence of smear and sputum positive tuberculosis (20).

One of the limitations of the present study was the uncertain status of most patients regarding HIV/AIDS and MDR-TB that due to theirs effects were not consider in multivariate model. One of the strength of this study was using the valuable data from the national tuberculosis surveillance program and preparing predictions for the next few years. Meanwhile this information can be used for TB control programs.

Conclusion

Because of the seasonal pattern of smear positive tuberculosis incidence, time series models with seasonal ARIMA are suitable for prediction. The results of this prediction show an increasing trend in smear positive TB cases in Iran.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, Informed Consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc) have been completely observed by the authors. This study used the number of TB cases detected per month, and no identification or patients’ personal information was revealed.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the personnel working at the Tuberculosis Office of the Ministry of Health and the tuberculosis coordinators of all Iranian Medical Science Universities who provided the data. This study was supported by a grant from the Deputy Research and Technology at Kerman University of Medical Sciences. This article is extracted from the Epidemiology Ph.D. thesis of Mr. Mahmood Moosazadeh. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Cox H, Kebede Y, Allamuratova S, Ismailov G, Davletmuratova Z, Byrnes G, et al. (2006). Tuberculosis Recurrence and Mortality after Successful Treatment: Impact of Drug Resistance. PLoS Med, 3 (10): e384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ignatova A, Dubiley S, Stepanshina V, Shemyakin I. (2006). Predominance of multi-drug-resistant LAM and Beijing family strains among Myco-bacterium tuberculosis isolates recovered from prison inmates in Tula Region, Russia. J Med Microbiol, 55 (10): 1413 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nasehi M, Moosazadeh M, Amiresmaeili M, Parsaee M, Nezammahalleh A. (2012). The Epidemiology of Factors Associated with Screening and Treatment Outcomes of Patients with Smear Positive Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Population-Based Study. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci, 21 (1) : 9– 18. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Corbett EL, Bandason T, Bun Cheung YB, Munyati S, Godfrey-Faussett P, Hayes R, et al. (2007). Epidemiology of Tuberculosis in a High HIV Prevalence Population Provided with Enhanced Diagnosis of Symptomatic Disease. PLoS Med, 4 (1): 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moosazadeh M, Khanjani N. (2012). The Existing Problems in the Tuberculosis Control Program of Iran: A Qualitative Study. J Qualitative Res Health Sci, 1 (3): 189 201. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Broekmans JF, Migliori GB, Rieder HL, Lees J, Ruutu P, Loddenkemper R, et al. (2002). European framework for tuberculosis control and elimination in countries with a low incidence. Eur Respir J, 19: 765– 775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hassan Zadeh J, Nasehi M, Rezaianzadeh A, Tabatabaee H, Rajaeifard A, Ghaderi E. (2013). Pattern of Reported Tuberculosis Cases in Iran 2009–2010. Iran J Public Health, 42 (1): 72 78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. CDC of Iran, Department of Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control (2012). Available from: http://www.cdc.hbi.ir.

- 9. Velayati AA, Farnia P, Mirsaeidi M, Reza Masjedi M. (2006). The most prevalent Mycobacterium tuberculosis superfamilies among Iranian and Afghan TB cases. Scand J Infect Dis, 38( 6–7): 463– 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moosazadeh M, Nasehi M, Bahrampour A, Khanjani N, Sharafi S, Ahmadi S. (2014). Forecasting tuberculosis incidence in Iran using box-Jenkins models. Iran Red Crescent Med J, 16 (5): e11779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jam S, Sabzvari D, SeyedAlinaghi S, Fattahi F, Jabbari H, Mohraz M. (2010). Frequency of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection among Iranian patients with HIV/AIDS by PPD test. Acta Med Iran, 48( 1): 67– 71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hadadi A, Tajik P, Rasoolinejad M, Davoudi S, Mohraz M. (2011). Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Patients with HIV/AIDS in Iran. Iran J Public Health, 40( 1): 100– 6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baker MA, Harries AD, Jeon CY, Hart JE, Kapur A, Lönnroth K, et al. (2011). The impact of diabetes on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Med, 1; 9: 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Akhtar S, Mohammad HGHH. (2008). Seasonality in pulmonary tuberculosis among migrant workers entering Kuwait. BMC Infect Dis, 8( 1): 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Avilov KK, Romanyukha AA. (2007). Mathematical modeling of tuberculosis propagation and patient detection. Automation and Remote Control, 68( 9): 1604– 1617. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang G, Huang S, Duan Q, Shu W, Hou Y, Zhu S, et al. (2013). Application of a hybrid model for predicting the incidence of tuberculosis in Hubei, China. PLoS One, 6; 8 (11): e80969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li XX, Wang LX, Zhang H, Du X, Jiang SW, Shen T, et al. (2013). Seasonal variations in notification of active tuberculosis cases in China, 2005–2012. PLoS One, 10; 8 (7): e68102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rios M, Garcia JM, Sanchez JA, Perez D. (2000). A statistical analysis of the seasonality in pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur J Epidemiol, 16: 483– 488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thorpe LE, Frieden TR, Laserson KF, Wells C, Khatri GR. (2004). Seasonality of tuberculosis in India: is it real and what does it tell us? Lancet, 364: 1613– 1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leung CC, Yew WW, Chan TYK, Tam CM, Chan CY, Chan CK, et al. (2005). Seasonal pattern of tuberculosis in Hong Kong. Int J Epidemiol, 34: 924– 930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luqureo FJ, Sanchez-Padilla E, Simon-Soria F, Eiros JM, Golub JE. (2008). Trend and seasonality of tuberculosis in Spain, 1996–2004. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 12: 221– 224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liao CM, Hsieh NH, Huang TL, Cheng YH, Lin YJ, Chio CP, et al. (2012). Assessing trends and predictors of tuberculosis in Taiwan. BMC Public Health, 12 (1): 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fares A. (2011). Seasonality of Tuberculosis. J Glob Infect Dis, 3( 1): 46– 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Willis MD, Winston CA, Heilig CM, Cain KP, Walter ND, Kenzie M. (2012). Seasonality of Tuberculosis in the United States, 1993–2008. Clin Infect Dis, 54( 11): 1553– 1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Statistical Center of Iran (2011). Available from: http://www.amar.org.ir

- 26. Kam HJ, Sung JO, Park RW. (2010). Prediction of Daily Patient Numbers for a Regional Emergency Medical Center using Time Series Analysis. Healthcare Inform Res, 16( 3): 158– 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Helfenstein U. (1996). Box-Jenkins modelling in medical research. Stat Methods Med Res, 5( 1): 3– 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yi J, Du CT, Wang RH, Liu L. (2007). Applications of multiple seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model on predictive incidence of tuberculosis. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi, 41 (2): 118– 21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Permanasari AE, Rambli DR, Dominic PD. (2011). Performance of Univariate Forecasting on Seasonal Diseases: The Case of Tuberculosis. Adv Exp Med Biol, 696: 171– 179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rafei A, Pasha E, Jamshidi Orak R. (2012). Tuberculosis surveillance using a hidden markov model. Iran J Public Health, 41( 10): 87– 96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moosazadeh M, Khanjani N, Abbas Bahrampoor A. (2013). Seasonality and temporal variations of tuberculosis in the north of Iran. Tanaffos, 12 (4) (in press). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jeon CY, Murray MB. (2008). Diabetes mellitus increases the risk of active tuberculosis: a systematic review of 13 observational studies. PLoS Med, 5: e152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Harries AD, Satyanarayana S, Kumar AMV, Nagaraja SB, Isaakidis P, Malhotra S, et al. (2013). Epidemiology and interaction of diabetes mellitus and tuberculosis and challenges for care: a review. PHA, 3( S1): S3– S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nnoaham KE, Clarke A. (2008). Low serum vitamin D levels and tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol, 37 (1): 113 119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marashian SM, Farnia P, Seyf S, Anoosheh S, Velayati AA. (2010). Evaluating the role of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms on susceptibility to tuberculosis among Iranian patients: a case-control study. Tuberk Toraks, 58( 2): 147– 53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]