Abstract

In non-endemic countries, leprosy, or Hansen's disease (HD), remains rare and is often underrecognized. Consequently, the literature is currently lacking in clinical descriptions of leprosy complications in the United States. Immune-mediated inflammatory states known as reactions are common complications of HD. Type 1 reactions are typical of borderline cases and occur in 30% of patients and present as swelling and inflammation of existing skin lesions, neuritis, and nerve dysfunction. Type 2 reactions are systemic events that occur at the lepromatous end of the disease spectrum, and typical symptoms include fever, arthralgias, neuritis, and classic painful erythematous skin nodules known as erythema nodosum leprosum. We report three patients with lepromatous leprosy seen at a U.S. HD clinic with complicated type 2 reactions. The differences in presentations and clinical courses highlight the complexity of the disease and the need for increased awareness of unique manifestations of lepromatous leprosy in non-endemic areas.

Introduction

Hansen's disease (HD), also known as leprosy, has not been eliminated from the United States with over 200 cases diagnosed yearly (http://www.hrsa.gov/hansensdisease/pdfs/hansens2009report.pdf). Worldwide, there were 219,075 new cases of leprosy reported in 2011.1 Even though the prevalence has decreased significantly with the help of multidrug therapy (MDT), leprosy remains a public health problem in many areas and poses diagnostic and treatment challenges.2 Leprosy is caused by the bacteria, Mycobacterium leprae, and infects skin, nerves, and mucous membranes with the potential to cause significant nerve damage and disability.3 In terms of presentation, leprosy involves a pathologic disease spectrum, with indeterminate and tuberculoid cases on one end of the spectrum and lepromatous disease on the opposite end (Table 1). Transmission is believed to occur through nasal droplets of untreated patients,4 but there is also evidence it could spread through direct contact. Because of its rare occurrence in non-endemic countries and nonspecific presentations, it is often misdiagnosed with subsequent delays in diagnosis and treatment contributing to permanent nerve damage.5 Finally, two types of severe immunologic reactions complicate about 30–50% of cases and are important causes of disability in patients. These are medical emergencies and need to be treated aggressively to avoid permanent nerve damage.

Table 1.

Pathologic classification of leprosy: Ridley–Jopling vs. WHO

| Leprosy type | Ridley–Jopling classification | WHO classification | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TT | Single or few lesions, negative or rare bacilli | Very good cell-mediated immunity | Paucibacillary |

| BT | Single or few lesions, rare bacilli | Good cell-mediated immunity | Paucibacillary (if less than five lesions), multibacillary if > 5 lesions |

| BB | Several lesions, more bacilli on histology | Fair cell-mediated immunity | Multibacillary |

| BL | Many lesions, many bacilli | Fair–poor cell-mediated immunity | Multibacillary |

| LL | Diffuse lesions, heavy bacillary load | Poor cell-mediated immunity | Multibacillary |

BB = borderline borderline; BL = borderline lepromatous; BT = borderline tuberculoid; LL = lepromatous; TT = tuberculoid; WHO = World Health Organization.

Reactions are characterized by immune responses to M. leprae that initiate a cascade of humoral and cellular responses.6 Type 1, or reversal, reactions are most typical of borderline cases, although can occur anywhere along the disease spectrum, and occur in 30% of patients. Reversal reactions typically present as enlargement of skin lesions, neuritis, and nerve dysfunction.7 Type 2 reactions (T2Rs), also known as erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), are systemic events that occur in borderline lepromatous and lepromatous cases and can cause damage to the nerves, eyes, and skin.8 Typical symptoms included fever, arthralgias, neuritis, nerve trunk inflammation, and classic painful erythematous skin nodules, hence the name ENL. These reactions can vary greatly from patient to patient, with several reports of unique clinical manifestations.9–12 The two reactions differ in their pathogenesis with type 1 reactions (T1Rs) typical of a predominate cell-mediated reaction and T2Rs with more of a mixed picture including an overactive humoral response.13 Although both reactions can cause nerve inflammation and damage, this is more likely to occur in T1Rs. On the other hand, systemic symptoms and evidence of inflammation (outside the skin lesions) are rare in T1Rs and occur more commonly in T2Rs.

This case series highlights three cases seen at the Emory TravelWell Clinic with varying and unique presentations of T2R. Since HD is still present in non-endemic countries including the United States, and with the increasing trends of human migration as a result of globalization, it is important for clinicians in non-endemic areas to be aware of atypical presentations of T2R because of its serious nature and need for immediate attention. Furthermore, since reactions can occur at any point during the disease, T2R may be the first manifestation of the disease and thus even more difficult for clinicians to diagnose. These three cases highlight the complexities of T2R. Recognizing a reaction in a timely manner is crucial for treatment and alleviation of symptoms to arrest nerve damage.

Case Reports

Case 1.

A 33-year-old woman, originally from Bangladesh, was admitted to an Atlanta hospital after 4 days of intermittent fever, neck and low back pain, and difficulty breathing through her nose. She had been diagnosed with lepromatous leprosy by skin biopsy 3 months prior, soon after immigrating to the United States, and had begun treatment with dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Her initial presentation involved a 3-year history of thickened facial skin with associated bilateral eye redness and intermittent numbness in ear lobes, fingers, and feet.

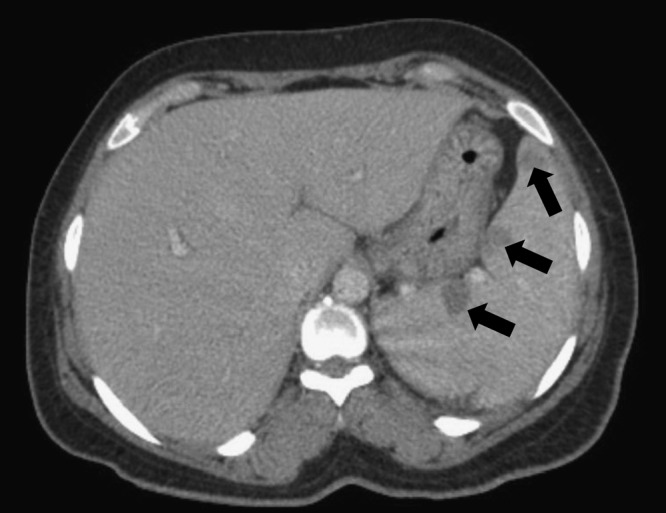

Examination was significant for an ill-appearing woman with a blood pressure of 98/47 mmHg, temperature of 39.3°C, diaphoresis, leonine facies, palpable splenic tip, localized edema, erythema, and calor in the hands and feet. There were no skin nodules, no new peripheral neurologic deficits, and no thickened peripheral nerves in exam. Laboratory studies showed signs of acute inflammation (Table 2) with a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein (CRP). The remaining laboratory findings are summarized in Table 2. Because of the hepatosplenomegaly, further infectious work-up was done including histoplasma antigen, malaria smears, Epstein-Barr virus polymerase chain reaction, and viral hepatitis serologies, all of which were negative. An interferon-gamma release assay for tuberculosis was also negative and chest radiography showed no acute pulmonary findings. A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast showed mild hepatomegaly, portal lymphadenopathy with the largest lymph node measuring 1.9 × 1.4 cm, and splenomegaly (17.4 cm in the craniocaudal dimension) with approximately 15 hypoattenuating lesions in the spleen, the largest being 1.6 cm (Figure 1 ).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of T2R in three different patients

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Fever, abdominal pain, nasal stuffiness, back pain | Joint/extremity swelling, nodular rash (initially), neuritis | Fever, new painful skin lesions |

| Exam findings | Abdominal tenderness, no rash | Joint swelling, erythematous lesions on back | Hypotension, diffuse nodular, tender rash, enlarged tender inguinal lymphadenopathy |

| Laboratory findings | ESR: > 120 mm/hour | CRP: 28.67 mg/L | Creatinine: 1.8 mg/dL |

| CRP: 10.82 mg/dL | WBCs: 5,600 cells/mL | ALT: 90 IU/L | |

| WBCs: 2,900 cells/mL | Creatinine: 1.3 mg/dL | AST: 119 IU/L | |

| Normal creatinine | Normal liver enzymes | WBCs: 23,400 cells/mL | |

| Normal liver enzymes | Na: 124 mmol/L | ||

| Radiographic findings | Abdominal CT: reactive mesenteric lymphadenopathy and hypodense splenic lesions | N/A | N/A |

| Treatment | Prednisone | Prednisone and thalidomide | Prednisone → thalidomide |

| Clinical course | Recurrence after 2 years with abdominal pain | Stable on low-dose prednisone and thalidomide after first recurrence | No recurrence after starting thalidomide |

ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; CRP = C-reactive protein; CT = computed tomography; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; N/A = not applicable; Na = sodium; T2R = type 2 reaction; WBCs = white blood cells.

Figure 1.

Case 1: computerized tomography of splenic lesions found on presentation of type 2 reaction (T2R).

Treatment with 60 mg of prednisone daily for presumed T2R was started and MDT continued. Within 48 hours, the patient was afebrile, breathing comfortably, with normalized white blood cell and platelet counts, and a decreasing CRP. Multiple repeat scans over the course of the following 2 years showed stable splenic lesions without progression, and she was weaned off prednisone completely 6 months after presentation. Two years after this episode, she presented with persistent abdominal pain, right-sided neck pain, and intermittent lower back pain. An abdominal CT scan showed scattered, mildly enlarged, reactive mesenteric lymph nodes, somewhat more prominent than in her prior CT scan. Prednisone (40 mg/day) was started for suspected recurrence of atypical T2R and her symptoms resolved. She was able to wean down to 5 mg of prednisone within 3 months without recurrence of abdominal pain.

Case 2.

The second patient is a 68-year-old man born in the United States who grew up in Texas and served in the Vietnam War. He initially presented with swollen hand and feet joints and progressive peripheral neuropathy. He was managed for a suspected seronegative arthritis for 3 years before presenting with erythema nodosum. At that time he was diagnosed with lepromatous leprosy confirmed by a skin lesion biopsy. He began MDT and was subsequently started on thalidomide for persistent symptoms of reaction because he had not responded to prednisone alone. His rash and joint swelling improved on low-dose prednisone and thalidomide. However, 6 months later, after his prednisone was weaned, he presented with recurrent severe extremity swelling and elevated CRP (Figure 2 , Table 2). He was afebrile, and the original skin lesions on his back were more erythematous than usual. Prednisone was increased and he continued on low-dose thalidomide with improvement of the extremity swelling. He was taken off thalidomide because of concern of worsening neuropathy and his clinical course remained stable on low-dose prednisone. His initial presentation of painful skin nodules was most consistent with T2R (ENL). However, his subsequent presentation appeared to be a mixed T1R and T2R due to increased inflammatory markers (T2R) and extremity swelling/prominence of old skin lesions (T1R).

Figure 2.

Case 2: erythematous lesions on back and extremity swelling.

Case 3.

A 42-year-old man from southeast Asia was referred to our clinic with a 1-year history of a nodular lesion on his left chest. His primary care doctor initially saw him and recommended observation. Because of persistence, the lesion was biopsied by a dermatologist and histopathologic analysis was consistent with lepromatous leprosy. He was started on dapsone, rifampin, and minocycline. After 9 months, he developed fever, enlarged inguinal lymphadenopathy and painful skin nodules on his back and lower extremities. He was diagnosed with T2R/ENL based on clinical features (Figure 3 ). He was switched to clofazimine while rifampin and dapsone were continued and high-dose oral prednisone (60 mg) was added with initial improvement of his symptoms (Figure 3). Unfortunately, his rash and systemic symptoms continued to flare whenever his prednisone dose was reduced.

Figure 3.

Case 3: left: erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) lesions and right: lesions 4 days after starting prednisone.

After 3 months, his oral prednisone dose was increased to 80 mg a day because of worsening symptoms. When this dose did not control his rash, fever, and lymphadenopathy, he was admitted to the hospital. On admission, his temperature was 39.1°C, heart rate 124 beats/minute, blood pressure 84/51 mmHg, and respiratory rate 28 breaths/minute. On exam, he had erythematous painful nodular lesions on his face, trunk, and extremities (Figure 4 ), with associated enlarged, tender inguinal lymphadenopathy. He had a normal neurologic exam. His laboratory evaluation on admission included a sodium of 125 mmol/L, potassium 3.7 mmol/L, glucose 120 mg/dL, creatinine 1.8 mg/dL (baseline < 1), total bilirubin 1.8 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 119 unit/L, alanine aminotransferase 92 unit/L, alkaline phosphatase 80 unit/L, white blood count 23,400/μL (87% segmented), hemoglobin 12 g/dL, platelets 218,000/μL, and a normal urine analysis. Given his fever, hypotension, and altered laboratory parameters, he was admitted to the medical intensive care unit and empirically treated with vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam for possible sepsis. On infectious diseases consultation, he was started on intravenous solumedrol for a suspected exacerbation of his known T2R with multiorgan involvement. He improved rapidly on parenteral steroids. Evaluation for other causes of fever was unrevealing. On discharge, he was subsequently started on thalidomide for recalcitrant T2R. He was eventually weaned off prednisone and continued on thalidomide. No documented relapses of ENL were recorded in the subsequent 2 years of follow-up. He completed leprosy treatment 12 months after presentation.

Figure 4.

Case 3: erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) lesions on the back on admission to the intensive care unit.

Discussion

These three cases of T2R/ENL represent the challenges faced by providers when diagnosing and treating HD. They also demonstrate the high index of suspicion necessary to recognize these complications. The pathogenesis of ENL or T2R involves an inflammatory reaction to M. leprae. ENL typically manifests clinically as painful, enlarged skin nodules that are sensitive to touch. Other symptoms include fever, neuritis, vasculitis, arthritis, and diffuse pain.14 The episodes are acute, but cause major discomfort and could lead to permanent nerve damage if neuritis is involved.

Although T2Rs are usually diagnosed clinically with typical exam findings as well as elevations of CRP and white blood cells in the blood, there are some characteristic histologic findings.15–17 ENL has traditionally been considered an immune complex–mediated condition, with neutrophils and immune complexes found sequestered in the lesions.18,19 Immunoglobulin levels (IgG and IgM) have also been shown to be elevated with T2Rs.20 T helper (Th1 and Th2) cell-mediated responses appear to be at play with evidence of elevated cytokines from both of these arms.21,22 Studies are mixed about the degree of contribution of Th1 and Th2 responses in the pathogenesis of T2Rs, although traditionally they are thought to be characterized by an overactive humoral immune response.13

Although ENL can happen at any point during the course of the infection, occurrence soon after treatment is initiated is common. This is thought to be associated with the killing of bacteria and subsequent release of bacterial antigens causing an inflammatory response.14 First-line treatment of ENL is thalidomide although the exact mechanisms of action are not completely understood.23,24 Corticosteroids are also common treatment of ENL, especially when thalidomide is not practical or safe. Finally, the World Health Organization also recommends the use of clofazimine as adjunctive therapy for T2R because of its anti-inflammatory properties.25 In cases where the patient still has active leprosy, MDT should be continued. An uncontrolled reaction can lead to permanent nerve damage, therefore prompt recognition and treatment is critical.

In the first patient, even though she did not have classic ENL skin lesions, her constellation of systemic symptoms in the absence of an alternative diagnosis was most consistent with a T2R especially given her high burden of infection. In addition to this atypical leprosy reaction (fever without new dermatologic or neurologic findings), an incidental finding of hepatosplenomegaly was discovered on CT with multiple hypoattenuating lesions in the spleen. Although she did not have a definitive aspiration of splenic lesion, multiple other diagnoses were ruled out. The lesions may have represented granulomas from M. leprae infection since the lesions persisted after resolution of her other reaction symptoms; however, immune complex phenomena related to T2R could not be ruled out as these have been found in other organs (i.e., the liver) besides the skin.26 Mycobacterium leprae has been previously recovered from liver biopsies, so the mild hepatomegaly may have been a result of direct mycobacterial infiltration or from an immune complex–mediated reaction syndrome.26,27 In terms of the spleen, a previous study showed that 41.1% of lepromatous patients in a small sample were found to have the formation of lepromas in the spleen on autopsy.28 Furthermore, a case report described aggregates of lepra cells (macrophages containing acid fast bacilli) dispersed throughout the spleen in a patient suffering from lepromatous leprosy and Lucio reaction.29 Splenic complications, although not widely reported, should be a concern for HD patients reporting pain in their abdominal region.

Case 2 shows how HD and concomitant reaction can be misdiagnosed and result in subsequent long-lasting nerve damage. The patient was misdiagnosed as having a seronegative arthritis for 3 years. This case also had elements of a mixed T1R and T2R. When he was first diagnosed, he had a nodular rash consistent with ENL. However, subsequently, he did not have ENL lesions—only swollen extremities and non-tender rash with more prominent erythema. This was more consistent with T1R, although he simultaneously had increased inflammatory markers consistent with a mixed picture. Mixed reactions have been reported previously, with 20 patients in a study performed in China reported symptoms of both a reversal reaction and ENL.30 The ability to recognize mixed reactions is important when treating HD patients, because the treatment of a reversal reaction and ENL can be different.

Case 3 demonstrates the potential severity of T2R, even mimicking a sepsis-like syndrome. In fact, in HD patients, T2Rs have been reported to be the most frequent reason for hospitalization.31 A retrospective study in Ethiopia described mortality associated with T2R. Although the authors suggest that the majority of the eight deaths were likely due to complications associated with corticosteroid use, two deaths were thought to be from T2R alone.32 Case 3 also highlights the fact that high-dose steroids are not always sufficient to treat ENL and why thalidomide is often first-line treatment.

Although all the three cases reported are T2R, the differences in presentations, clinical courses, and responses to treatment highlight the complexity of the disease and the need for increased awareness of unique manifestations of lepromatous leprosy. This is especially important in non-endemic area such as the United States. Although varying presentations like these may be more common in endemic areas, providers in the United States and other non-endemic countries are often very unfamiliar with leprosy reactions. Furthermore, these varied presentations of T2Rs make it imperative that physicians have a high index of suspicion both for HD as well as for reactions complicating the course of HD to avoid delays in treatment and to decrease the risk of permanent nerve damage. Finally, as illustrated in this case series, recurrences of T2R are common and therefore necessitates close follow-up of patients.33

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to staff support provided by the TravelWell Clinic of Emory University in the care of these patients. We also acknowledge the clinical advice and support provided by Barbara Stryjewska and David Scollard at the National Hansen's Disease Program, Baton Rouge, LA. Unfortunately, Robert W. McDonald passed away before the submission of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial support: The care of these patients was financially supported by a contract from the United States Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Salinas is partially supported by the Fogarty Global Health Fellowship (R25TW009337).

Authors' addresses: Kristoffer Leon, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, E-mail: keleon@emory.edu. Jorge L. Salinas, Robert W. McDonald (deceased), Anandi N. Sheth, and Jessica K. Fairley, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, E-mails: jlsalinas@emory.edu, ansheth@emory.edu, and jessica.fairley@emory.edu.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Global leprosy situation, 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;87:317–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodrigues LC, Lockwood DNJ. Leprosy now: epidemiology, progress, challenges, and research gaps. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:464–470. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White C, Franco-Paredes C. Leprosy in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:80–94. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00079-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Job CK, Jayakumar J, Kearney M, Gillis TP. Transmission of leprosy: a study of skin and nasal secretions of household contacts of leprosy patients using PCR. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:518–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang F, Chen S, Sun Y, Chu T. Healthcare seeking behaviour and delay in diagnosis of leprosy in a low endemic area of China. Lepr Rev. 2009;80:416–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhat RM, Prakash C. Leprosy: an overview of pathophysiology. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2012;2012:6. doi: 10.1155/2012/181089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker SL, Lockwood DN. Leprosy type 1 (reversal) reactions and their management. Lepr Rev. 2008;79:372–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Legendre DP, Muzny CA, Swiatlo E. Hansen's disease (leprosy): current and future pharmacotherapy and treatment of disease-related immunologic reactions. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32:27–37. doi: 10.1002/PHAR.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rattan R, Shanker V, Tegta GR, Verma GK. Severe form of type 2 reaction in patients of Hansen's disease after withdrawal of thalidomide: case reports. Indian J Lepr. 2009;81:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendiratta V, Malik M, Gurtoo A, Chander R. Fulminant hepatic failure in a 15 year old boy with borderline lepromatous leprosy and type 2 reaction. Lepr Rev. 2014;8:54–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naveen KN, Athanikar SB, Hegde SP, Athanikar VS. Livedo reticularis in type 2 lepra reaction: a rare presentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:182–184. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.131097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh SK, Sharma T, Rai T, Prabhu A. Type 2 lepra reaction in an immunocompromised patient precipitated by filariasis. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2014;35:40–42. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.132418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamath S, Vaccaro SA, Rea TH, Ochoa MT. Recognizing and managing the immunologic reactions in leprosy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:795–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahawita IP, Lockwood DNJ. Towards understanding the pathology of erythema nodosum leprosum. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mabalay MC, Helwig EB, Tolentino JG, Binford CH. The histopathology and histochemistry of erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Lepr. 1965;33:28–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva EA, Iyer A, Ura S, Lauris JR, Naafs B, Das PK, Vilani-Moreno F. Utility of measuring serum levels of anti-PGL-I antibody, neopterin and C-reactive protein in monitoring leprosy patients during multi-drug treatment and reactions. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:1450–1458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Memon RA, Hussain R, Raynes JG, Lateff A, Chiang TJ. Alterations in serum lipids in lepromatous leprosy patients with and without ENL reactions and their relationship to acute phase proteins. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1996;64:115–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wemambu SN, Turk JL, Waters MF, Rees RJ. Erythema nodosum leprosum: a clinical manifestation of the arthus phenomenon. Lancet. 1969;2:933–935. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)90592-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridley MJ, Ridley DS. The immunopathology of erythema nodosum leprosum: the role of extravascular complexes. Lepr Rev. 1983;54:95–107. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19830015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma VK, Saha K, Sehgal VN. Serum immunoglobulins an autoantibodies during and after erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1982;50:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laal S, Bhutani LK, Nath I. Natural emergence of antigen-reactive T cells in lepromatous leprosy patients during erythema nodosum leprosum. Infect Immun. 1985;50:887–892. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.3.887-892.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdallah M, Attia EA, Saad AA, El-Khateeb EA, Lotfi RA, Abdallah M, El-Shennawy D. Serum Th1/Th2 and macrophage lineage cytokines in leprosy; correlation with circulating CD4+ CD25high FoxP3+ T-regs cells. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:742–747. doi: 10.1111/exd.12529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker SL, Waters MF, Lockwood DN. The role of thalidomide in the management of erythema nodosum leprosum. Lepr Rev. 2007;78:197–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheskin J. Thalidomide in the treatment of lepra reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1965;6:303–306. doi: 10.1002/cpt196563303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization . WHO Guidelines for the Management of Severe Erythema Nodosum Leprosum (ENL) Reactions. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patnaik JK, Saha PK, Satpathy SK, Das BS, Bose TK. Hepatic morphology in reactional states of leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1989;57:499–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bullock WE. Leprosy: a model of immunological perturbation in chronic infection. J Infect Dis. 1978;137:341–354. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu TC, Qiu JS. Pathological findings on peripheral nerves, lymph nodes, and visceral organs of leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1984;52:377–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rea TH, Bevans L, Taylor CR. The histopathology of the spleen from a patient with lepromatous leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1980;48:285–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen J, Liu M, Zhou M, Wengzhong L. Occurrence and management of leprosy reaction in China in 2005. Lepr Rev. 2009;80:164–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy L, Fasal P, Levan N, Freedman R. Treatment of erythema nodosum leprosum with thalidomide. Lancet. 1973;302:324–325. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)90829-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker SL, Lebas E, Doni SN, Lockwood DN, Lambert SM. The mortality associated with erythema nodosum leprosum in Ethiopia: a retrospective hospital-based study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voorend CGN, Post EB. A systematic review on the epidemiological data of erythema nodosum leprosum, a type 2 leprosy reaction. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]