Abstract

Interleukin-15 (IL-15), a potent stimulant of CD8+ T and NK cells, is a promising cancer immunotherapeutic. ALT-803 is a complex of an IL-15 superagonist mutant and a dimeric IL-15 receptor αSu/Fc fusion protein that was found to exhibit enhanced biologic activity in vivo with a substantially longer serum half-life than recombinant IL-15. A single intravenous dose of ALT-803, but not IL-15, eliminated well-established tumors and prolonged survival of mice bearing multiple myeloma. In this study, we extended these findings to demonstrate the superior antitumor activity of ALT-803 over IL-15 in mice bearing subcutaneous B16F10 melanoma tumors and CT26 colon carcinoma metastases. Tissue biodistribution studies in mice also showed much greater retention of ALT-803 in the lymphoid organs compared to IL-15, consistent with its highly potent immunostimulatory and antitumor activities in vivo. Weekly dosing with 1 mg/kg ALT-803 in C57BL/6 mice was well-tolerated, yet capable of increasing peripheral blood lymphocyte, neutrophil and monocyte counts by >8-fold. ALT-803 dose-dependent stimulation of immune cell infiltration into the lymphoid organs was also observed. Similarly, cynomolgus monkeys treated weekly with ALT-803 showed dose-dependent increases of peripheral blood lymphocyte counts, including NK, CD4+, and CD8+ memory T cell subsets. In vitro studies demonstrated ALT-803-mediated stimulation of mouse and human immune cell proliferation and IFN-γ production without inducing a broad-based release of other proinflammatory cytokines (i.e., cytokine storm). Based on these results, a weekly dosing regimen of ALT-803 has been implemented in multiple clinical studies to evaluate the dose required for effective immune cell stimulation in humans.

Keywords: IL-15 superagonist, ALT-803, pharmacodynamics, biodistribution, toxicity

Introduction

Therapeutic approaches using common γ-chain cytokines, such as interleukin-2 (IL-2), for patients with cancer offer the potential for curative antitumor immune responses (1, 2). However, IL-2 therapy has limitations due to its significant toxicity and immunosuppressive activity mediated by T regulatory cells (Tregs) (3-6). Alternative approaches employing the other γ-chain cytokines have focused on stimulating effector immune cells against tumors without inducing Tregs or IL-2-associated capillary leak syndrome (7, 8).

IL-15, like IL-2, has the ability to stimulate T cell and natural killer (NK) cell responses through the IL-2 receptor β-common γ chain (IL-2Rβγc) complex (9, 10). However, these cytokines exhibit functionally distinct activities due to differential interactions with their unique α receptor subunits. IL-2 is produced as a soluble protein that binds to immune cells expressing IL-2Rβγc or IL-2Rαβγc complexes. In contrast, IL-15 and its IL-15Rα chain are co-expressed by monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells and subsequently displayed as a cell surface IL-15:IL-15Rα complex, which is trans-presented to neighboring immune cells expressing IL-2Rβγc (10, 11). Due to these differences, unlike IL-2, IL-15 does not support maintenance of Tregs and rather than inducing apoptosis of activated CD8+ T cells, provides anti-apoptotic signals (9, 12). IL-15 also has non-redundant roles in the development, proliferation and activation of NK cells (13-15). IL-15 does not induce significant capillary leak syndrome in mice or nonhuman primates (NHPs), suggesting that IL-15-based therapies may provide the immunostimulatory benefits of IL-2 with fewer adverse effects (AEs) (16, 17).

Since IL-15Rα is considered an integral part of the active cytokine complex, various therapeutic strategies are being explored using soluble pre-associated IL-15:IL-15Rα complexes (18-23). For example, IL-15:IL-15Rα/Fc (i.e., soluble IL-15Rα linked to an Ig Fc-domain) was found to exhibit up to 50-fold greater activity than free IL-15 in stimulating mouse CD8+ T cell proliferation (19). Additionally, IL-15:IL-15Rα/Fc increased efficacy compared to IL-15 in various mouse tumor models (18, 21, 24, 25). These effects may be partially due to a ~150-fold increase in IL-2Rβγc binding affinity for the IL-15:IL-15Rα complex compared to free IL-15 (26). Moreover, the IL-15:IL-15Rα/Fc complex greatly enhanced IL-15 half-life and bioavailability in vivo (18), suggesting advantages of IL-15:IL-15Rα/Fc over free IL-15 as an immunotherapeutic (27). Although non-clinical studies demonstrated the pharmacodynamic and safety profiles of IL-15 in NHPs (17, 28-30), similar studies have not yet been reported to support clinical development of IL-15:IL-15Rα complexes.

To advance IL-15:IL-15Rα-based therapies into clinical testing, we have created a complex (referred to as ALT-803) between a novel human IL-15 superagonist variant (IL-15N72D) and a human IL-15Rα sushi domain-Fc fusion protein (22, 23). We have previously shown that the IL-15N72D mutation increases IL-2Rβγc binding and IL-15 biological activity by ~5-fold (22). This IL-15 superagonist fusion protein complex, ALT-803 (IL-15N72D:IL-15RαSu/Fc), exhibited superior immunostimulatory activity, a prolonged serum half-life, and more potent anti-myeloma activity compared to IL-15 in mouse models (23, 31). In this paper, we further evaluate the antitumor activity, biodistribution, pharmacodynamics and toxicity of ALT-803 in mice. We found that ALT-803 was significantly more efficacious than IL-15 in mice bearing solid tumors. Additionally, ALT-803 was retained in lymphoid organs to a greater extent than IL-15, consistent with its more potent immunostimulatory and antitumor activities in vivo. Evaluation of ALT-803 toxicity in mice compared to its efficacious dose in various tumor models indicated that this complex has a wide therapeutic dose range. Finally, studies of multidose ALT-803 treatment in cynomolgus monkeys and dose-dependent effects on human immune cell activity provided results consistent with mouse studies and further defined a weekly dosing regimen suitable for initiation of human clinical studies.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and animals

ALT-803 was generated as previously described (23). Recombinant human IL-15 (IL-15) (17) was kindly provided by Dr. Jason Yovandich (National Cancer Institute, Fredrick, MD). Antibodies used to characterize immune cell phenotype and activation markers are described in Supplementary Table S1. C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were obtained from Harlan Laboratories and cynomolgus monkeys were supplied by Yunnan Laboratory Primate, Inc. (YLP) (Kunming, China) and the Oregon National Primate Research Center. All animal studies (mouse biodistribution at Univ. Wisconsin, other mouse studies at Altor BioScience, and monkey studies at YLP and Oregon Health and Science University) were conducted under approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols.

Cell lines and human PBMCs

The murine B16F10 (CRL-6475) and CT26 (CRL-2638) tumor cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection in 2009 and 2013, respectively. Within one week of receipt, the cells were viably cryopreserved and stored in liquid nitrogen. Both tumor cell lines shown to be free of Mycoplasma contamination. In each experiment, one frozen vial was expanded for use and the cells were authenticated by confirming cell morphology in vitro and reproducible tumor growth characteristics in mice of the control treatment groups. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated using Histopaque (Sigma) from peripheral blood of anonymous donors (OneBlood, Lake Park, FL) (17, 23). Human PBMCs, mouse splenocytes and CT26 cells were cultured in R10 media (32). B16F10 cells were cultured in IMDM (HyClone) supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging and tissue biodistribution studies

Protein conjugation methods with 2-S-(4-isothiocyanatobenzyl)-1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid (p-SCN-Bn-NOTA) (Macrocyclics), radiolabeling with 64CuCl2 (UW-Madison cyclotron facility), and subsequent purification were conducted as previously described (33). For serial PET imaging, C57BL/6 mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) with 3-7 MBq of 64Cu-labeled ALT-803 or IL-15 (~3.7 GBq/mg protein). Static PET scans were performed on anesthetized animals at various times post-injection using an Inveon microPET/microCT hybrid scanner (Siemens). Data acquisition, image reconstruction, and region-of-interest analysis to calculate the percentage injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g) for major organs were conducted as previously described (33, 34). At various times post-injection, mice were euthanized and blood, lymph nodes, thymus, and major organs/tissues were collected and weighed. The radioactivity in each tissue was measured using a gamma-counter (Perkin Elmer) and presented as %ID/g.

In vitro studies

Cytokine-release and proliferation assays were conducted on human and mouse immune cells using ALT-803 as soluble protein, or as soluble or air-dried plastic-immobilized proteins prepared according to Stebbing et al. (35). ALT-803 was tested at 0.08, 0.8, and 44 nM, which correspond to maximal serum concentrations in humans as a 0.3, 3.0, and 170 μg/kg i.v. dose, respectively. For proliferation assays, human PBMCs and mouse CD3+ T cells enriched from splenocytes (CD3+ T Cell Enrichment column, R&D Systems) were labeled with CellTrace™ Violet (Invitrogen) and cultured in PBS- or ALT-803-containing wells. As a positive control, 27 nM of monoclonal antibody (mAb) to CD3 (145-2C11 for mouse splenocytes and OKT3 for human PBMCs) (BioLegend) was added to separate wells in the same assay formats. Cells were incubated for 4 days and then analyzed by flow cytometry to determine cell proliferation based on violet dye dilution. Additionally, human and mouse immune cells were cultured as described above for 24 and 96 hours. Cytokines released into the media were measured using human and mouse cytometric bead array (CBA) Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokine kits per manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences).

For assessment of immune cell subset and activation markers, human PBMCs were cultured in various concentrations of ALT-803, stained under appropriate conditions with marker-specific antibodies (Supplementary Table S1), and analyzed on a FACSVerse flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using FACSuite software.

Antitumor efficacy and toxicity of ALT-803 in mice

Comparative efficacy of ALT-803 and IL-15 was assessed in immunocompetent mice bearing subcutaneous (s.c.) B16F10 melanoma tumors or CT26 colon carcinoma metastases. C57BL/6 mice were injected s.c. with B16F10 cells (5×105/mouse) and then treated with i.v. ALT-803, IL-15 or PBS as described in the figure legends. Tumor volume was measured as described (36). In the second model, BALB/c mice were injected i.v. with CT26 cells (2×105/mouse) and treated with i.v. ALT-803, IL-15 or PBS as described in the figure legends. Mouse survival based on humane endpoint criteria was monitored to generate survival curves.

Toxicity studies were conducted in C57BL/6 mice (~10-11 weeks old) that were injected i.v. with 0.1, 1.0, or 4.0 mg/kg ALT-803 or PBS weekly for 4 weeks (study days (SD) 1, 8, 15 and 22). Assessments including physical examination, serum chemistry, hematology, gross necropsy, body and organ weight and histopathology were performed on mice sacrificed at 4 days (SD26) or 2 weeks (SD36) post-treatment. In a second study, C57BL/6 mice were treated with 4 weekly i.v. injections of 0.1 or 1.0 mg/kg ALT-803 or PBS and toxicity assessments were performed 4 days (SD26) or 4 weeks (SD50) post-treatment.

Toxicity, pharmacodynamics (PD), and pharmacokinetics (PK) of ALT-803 in cynomolgus monkeys

A study was performed under Good Laboratory Practice guidelines to evaluate the effects of multidose administration of ALT-803 in cynomolgus monkeys. Animals (2-3 years old, 5 animals/sex/group) were treated weekly for 4 weeks (SD1, 8, 15 and 22) with 0.03 or 0.1 mg/kg ALT-803 or PBS administered i.v. over about 3 minutes. Throughout the in-life study phase, animals were assessed for clinical and behavioral changes, food consumption, body weight, cardiac and ocular function. Blood was collected for hematology, chemistry, coagulation, and immune cell analysis pre-dosing and on SD5, 26 and 36. Immunogenicity testing and PK analyses were conducted using validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) methods. Urine was collected for urinalysis (pre-dosing and SD4, 25 and 35). Clinical pathology assessments including physical examination, gross necropsy, organ weight measurements and histopathology were performed 4 days (SD26) and 2 weeks (SD36) post-treatment.

A separate time course study was conducted on 2 animals (5 year-old females) injected i.v. with 0.1 mg/kg ALT-803 on SD1, 8, 15 and 22. Blood and serum were collected as indicated in the figure legend. Serum cytokines were measured using NHP CBA Th1/Th2 cytokine kits (BD Biosciences). Immune cell phenotyping was conducted on blood samples after lysis of red blood cells and staining with antibodies specific to immune cell phenotype markers (Supplementary Table S1). For Ki67 assessment, cells were fixed with BD FACS Lysing solution (BD Biosciences) prior to antibody staining.

Data analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SE. Survival data were analyzed using the log-rank test and Kaplan–Meier method. Comparisons of continuous variables were done using Student t tests or ANOVA (2-tailed; GraphPad Prism Version 4.03). P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. PK analysis was conducted as previously described (23).

Results

Comparative efficacy of ALT-803 and IL-15 against solid tumors in immunocompetent mice

In mice bearing myeloma tumors, single-dose treatment of ALT-803 was found to provide significant reduction of tumor burden compared to an equivalent dose of IL-15 (36). To extend these findings to solid tumors, we compared the antitumor activity of ALT-803 and IL-15 against subcutaneous (s.c.) B16F10 melanoma tumors or CT26 colon carcinoma metastases, which are sensitive to IL-15-based therapies (24, 37). As shown in Fig. 1A, B16F10 cells injected s.c. into the flank of C57BL/6 mice developed into palpable tumors by day 7 and progressed rapidly over the next 8 days. Treatment of tumor-bearing mice with IL-15 on days 1 and 8 failed to affect tumor growth. In contrast, ALT-803 administered at a molar cytokine equivalent dose (i.e., 0.06 mg/kg IL-15 equals 0.2 mg/kg ALT-803) significantly inhibited growth of B16F10 tumors compared to IL-15 (P < 0.05) or PBS (control) (P < 0.01) treatment. These results are comparable to previous studies demonstrating superior efficacy of pre-associated IL-15:IL-15Rα complexes against s.c. and metastatic B16 tumors (18, 24).

Figure 1.

Comparative antitumor activity of ALT-803 and IL-15 in immunocompetent mice bearing solid tumors. A, changes in tumor volume of subcutaneous B16F10 melanoma tumors in C57BL/6 mice treated with i.v. PBS, 0.2 mg/kg ALT-803, or 0.06 mg/kg IL-15 (IL-15 molar equivalent dose of 0.2 mg/kg ALT-803) on days 1 and 8 post-tumor injection. Data points are expressed as mean + SE (n = 5 mice/group). *, P < 0.05 comparing ALT-803 vs. IL-15. B, survival curves of BALB/c mice (n = 6/group) injected i.v. with CT26 colon carcinoma cells and subsequently treated with i.v. 0.25 mg/kg IL-15 on study days 1 to 5, and 8 to 12, or with 0.2 mg/kg ALT-803, or PBS on study days 1, 4, 8, and 11. *, P < 0.05 comparing IL-15 vs. PBS; **, P < 0.01 comparing ALT-803 vs. IL-15 or PBS. The results shown for both tumor models are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

In the CT26 colon carcinoma metastases model (Fig. 1B), IL-15 administered as five weekly 0.25 mg/kg doses (10 doses total) for 2 weeks resulted in modest improvement in survival of tumor-bearing mice compared to the control group (median survival time (MST): IL-15, 17 days vs. PBS, 15 days; P < 0.05), consistent with previously published results (37). However, less frequent dosing with ALT-803 (four 0.2 mg/kg doses over 2 weeks) provided significantly better survival benefit than either IL-15 or PBS (MST; ALT-803; 22.5 days; P < 0.01 vs. IL-15 or PBS). Notably, this enhanced efficacy was observed with a cumulative molar cytokine dose of ALT-803 that was 9% of the IL-15 dose. Together, these results are consistent with potent immunostimulatory activity of ALT-803 compared to IL-15 observed in vivo and in our previous efficacy studies in hematologic tumor models (23, 31).

Biodistribution of ALT-803 in mice

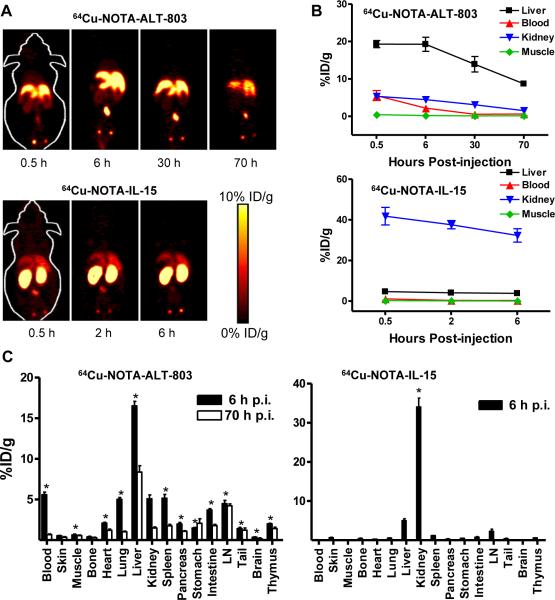

Earlier studies indicated that ALT-803 had a 25 hour serum half-life in mice compared to <40 minutes observed for IL-15 (23). To further explore the pharmacokinetic properties of these molecules, biodistribution studies were conducted in mice administered 64Cu-labeled ALT-803 or IL-15. Serial non-invasive PET scans of C57BL/6 mice at different times post-injection showed that 64Cu-IL-15 was rapidly cleared via the renal pathway consistent with previous reports (38), whereas ALT-803 was cleared primarily via the hepatobiliary pathway (Fig. 2A and B). In accordance with PK analysis, 64Cu-ALT-803 exhibited a longer circulatory half-life than 64Cu-IL-15. Tissue distribution of the 64Cu-labeled proteins was determined at 6 hours (IL-15 and ALT-803) and 70 hours (ALT-803) post-injection (Fig. 2C). These results corroborated the findings from the PET scans by showing elevated uptake of 64Cu-IL-15 and 64Cu-ALT-803 in the kidneys and liver, respectively, at 6 hours post-injection. Additionally, 64Cu-ALT-803 levels were elevated in the lungs, spleen, and lymph nodes at 6 hours post-injection and persisted at >4 %ID/g in the lymph nodes for at least 70 hours post-injection, at which time 64Cu-IL-15 was not detectable. Thus, ALT-803 not only exhibits a longer serum half-life but also greater distribution and a longer residence time in the lymphoid organs than IL-15.

Figure 2.

Quantitative PET imaging and biodistribution of ALT-803 and IL-15 in C57BL/6 mice. A, serial coronal PET images at different time points post-injection of 64Cu-ALT-803 (0.5, 6, 30, and 70 hours) or 64Cu-IL-15 (0.5, 2, and 6 hours). B, time-activity curves of quantitative PET imaging of the liver, kidney, blood, and muscle upon i.v. injection of 64Cu-ALT-803 and 64Cu-IL-15. Data are expressed as mean percentages + SE of %ID/g (n = 4). C, tissue biodistribution of 64Cu-ALT-803 (left) and 64Cu-IL-15 (right) in C57BL/6 mice at 6 hours and 70 hours post-injection. Data are expressed as mean percentages + SE of %ID/g (n = 4/group). *, tissue showing significantly greater distribution of ALT-803 compared to IL-15 (left) or significantly greater distribution of IL-15 compared to ALT-803 (right) at 6 hours post-injection (P < 0.05). The results shown are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Immunostimulatory effects of ALT-803 on murine and human immune cells

To assess the ALT-803-mediated responses of mouse and human immune cells, studies were conducted with human PBMCs and mouse splenocytes incubated with soluble or plastic-immobilized ALT-803 (Fig. 3). Incubation with immobilized ALT-803 for 1 day (data not shown) or 4 days (Fig. 3A) resulted in elevated IFN-γ release by human PBMCs. Soluble IL-6 was also increased in 4-day PBMC cultures treated with ALT-803; however, this effect was not dose-dependent. In contrast, ALT-803 had no effect on TNF-α, IL-4, IL-10, or IL-17A release in 4-day PBMC cultures (data not shown). When tested in parallel cultures, a positive control anti-CD3 mAb induced release of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-4 (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

ALT-803 induces cytokine release and proliferation of mouse and human immune cells in vitro. A, human PBMCs (n = 3 from normal donors) were incubated for 4 days in wells containing media and the indicated concentrations of soluble or plastic-immobilized ALT-803. At the end of the incubation period, concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines in the culture media were assessed using a cytometric bead array. ALT-803-mediated changes in human IFN-γ and IL-6 were observed and are plotted, whereas no significant differences in the levels of human TNF-α, IL-4, IL-10, or IL-17A were found among the treatment groups. Bars represent mean cytokine concentration ± SE. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 comparing ALT-803 vs. media control. B, CD3-enriched mouse splenocytes (n = 6) were incubated for 4 days in media containing soluble or immobilized ALT-803 and concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines in the culture media were assessed as described in (A). Mouse IFN-γ and TNF-α levels were significantly induced by ALT-803, but there were no treatment-mediated changes in the levels of IL-6, IL-2, IL-10, IL-4, and IL-17A. Bars represent mean cytokine concentration ± SE. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 comparing ALT-803 vs. media control. C, CD3-enriched mouse splenocytes (n = 6) (left) and human PBMCs (n = 3) were labeled with CellTraceTM violet and cultured for 4 days in media containing soluble or immobilized ALT-803 as described in (A). As a positive control, 27 nM of anti-CD3 Ab (145-2C11 for mouse splenocytes and OKT3 for human PBMCs) was added to separate wells in the same assay formats. At the end of the incubation period, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine cell proliferation based on violet dye dilution. Bars represent mean ± SE of percent total lymphocytes that showed decreased violet-labeling (i.e., proliferating cells). *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 comparing ALT-803 vs. media control. The results shown for plastic-immobilized ALT-803 aqueous solution were equivalent to those observed for ALT-803 that was air-dried onto the assay wells. In each case, the results shown are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

Compared to human immune cells, mouse splenocytes exhibited a similar but less intense response for IFN-γ release following incubation with ALT-803 (Fig. 3B). ALT-803 also induced TNF-α production by splenocytes but showed no significant effect on IL-6, IL-2, IL-10, IL-4 and IL-17A concentrations. Conversely, murine lymphocytes incubated with immobilized mAb to CD3 showed significantly elevated release of all of the cytokines tested except for IL-6 (Fig. 3C). Together, these findings indicate that ALT-803 primarily stimulates IFN-γ production by human and mouse immune cells, in contrast to the broad profile of cytokines induced by mAb to CD3.

The ability of ALT-803 to induce in vitro proliferation of CellTrace™ Violet-labeled human and mouse immune cells was also evaluated. Pronounced proliferation of mouse lymphocytes was evident following incubation with 0.8 - 44 nM soluble or immobilized ALT-803 (Fig. 3D). Up to 83% of the cells in the high-dose soluble ALT-803 group underwent 1-6 rounds of cell division during the 4-day incubation period. Little or no proliferation was detected in untreated murine cells or those treated with 0.08 nM soluble ALT-803. As expected, murine lymphocytes incubated with immobilized mAb to CD3 exhibited strong proliferative responses (Fig. 3E). ALT-803 dose-dependent lymphocyte proliferation was also observed in human PBMC cultures, but to a lesser extent than that seen for mouse cells (Fig. 3D). Overall, <20% of all human lymphocytes proliferated in response to high-dose ALT-803 and these responses were lower than those induced by the positive control mAb to CD3 ((Fig. 3E). The mechanisms responsible for the differential responsiveness of mouse and human immune cells to ALT-803 (and mAb to CD3) stimulation are not understood.

Both soluble and immobilized forms of ALT-803 were capable of stimulating mouse and human immune cell proliferation. However, immobilized ALT-803 (44 nM) was more potent than soluble ALT-803 at stimulating IFN-γ release (Fig. 3A and B), suggesting IL-2Rβγc crosslinking and stronger signaling provided by immobilized ALT-803 is required for this response. Additionally, significant variations in the immunostimulatory activity of both ALT-803 and mAb to CD3 were observed in lymphocytes collected from different human donors, likely due to different genetic and environmental factors shaping immune responses in these individuals.

The immunostimulatory activity of ALT-803 was further assessed in 7-day cultures of human PBMCs. Treatment with 0.5 nM of soluble ALT-803 resulted in 2.1-fold increase (range: 1.4 – 3.1, n = 7) in lymphocyte counts (Fig. 4A). These effects were due to increased numbers of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (3.0- and 1.8-fold, respectively) and NK cells (2.8-fold), whereas CD19+ B cell and Treg cell counts were not significantly changed by incubation with ALT-803 compared to control. Similar effects were seen with equivalent concentrations of IL-15, consistent with previous studies reporting comparable in vitro activity of these proteins on human PBMCs bearing IL-15Rα/IL-2Rβγc complexes (32). Titration studies showed that 0.07 nM ALT-803 significantly increased CD8+ T cell numbers in 7-day human PBMC cultures (Fig. 4B). Additionally, cell surface activation marker expression of CD69 on NK and CD8+ T cells and CD25 on NK and CD4+ T cells was stimulated by ALT-803 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4C). Consistent with increased cytotoxic activity against NK-sensitive cells and tumor cells (32), ALT-803 also induced increased granzyme B and perforin expression in both human NK cells and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4D). Together, these findings indicate that ALT-803 at a concentration as low as 0.01 nM is capable of activating human immune cells in vitro.

Figure 4.

ALT-803 stimulates proliferation and activation of human NK cells and T cells in vitro. A, human PBMCs (n = 7 normal donors) were cultured for 7 days in media alone or media containing 0.5 nM ALT-803 or IL-15. At the end of the incubation period, changes in absolute cell counts were determined following staining with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD8a, CD4, CD335, CD19, and CD4/CD25/FOXP3. Bars represent mean ± SE. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 comparing ALT-803 vs. media control. B, ALT-803 ranging from 0.07 to 5.5 nM was added to human PBMC cultures (n = 2 donors). After 7 days, changes in CD8+ T cell counts were assessed. Bars represent mean ± SE. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 comparing ALT-803 vs. media control. C, representative normal donor PBMCs were cultured for 5 days in the indicated concentrations of ALT-803. Cells were then harvested and expression of the cell surface activation markers CD25 and CD69 was determined on CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and NK cells by flow cytometry. The symbols represent mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± SE of triplicates. Similar treatment-related changes were obtained with other human donor PBMCs though control levels of CD25 and CD69 varied between individuals. D, human PBMCs (n = 2 donors) were cultured for 5 days in the indicated concentrations of ALT-803. Following stimulation, cells were harvested and analyzed for intracellular perforin and granzyme B expression in NK cells and CD8+ T cells. The symbols represent the MFI ± SE. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 comparing ALT-803 vs. media control. In each case, the results shown are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

Toxicity of ALT-803 in mice

The results of comparative binding of ALT-803 to immune cells from mice, cynomolgus monkeys, and healthy human donors were consistent with previously reported species-specific differences in IL-15 binding to IL-15Rα/IL-2Rβγc complexes (Supplementary Fig. S3) (39) and verify that mice and cynomolgus monkeys are appropriate species for evaluating the range of ALT-803-mediated effects. Thus, the safety and pharmacodynamic profiles of ALT-803 were assessed in healthy C57BL/6 mice injected i.v. with 0.1, 1.0, or 4.0 mg/kg ALT-803, or PBS weekly for 4 consecutive weeks (Fig. 5A). Mice receiving 4.0 mg/kg ALT-803 exhibited signs of toxicity (i.e., weight loss) and mortality between 4 - 20 days after treatment initiation. Post-mortem necropsy did not determine the cause of death but observations (i.e., pulmonary edema, and enlarged lymph nodes and spleen) were consistent with cytokine-induced inflammatory responses (40, 41). Treatment-related mortality was not observed in mice treated with 1.0 or 0.1 mg/kg ALT-803 (n = 50/dose level). Dose-dependent increases in spleen weights and white blood cell (WBC) counts were seen 4 days after the last dose of ALT-803 (SD26) (Fig. 5B). Of the WBCs, absolute counts for lymphocytes, neutrophils, and monocytes all increased >8-fold in 1.0 mg/kg ALT-803-treated mice compared to controls. By 2 weeks after treatment (SD36), lymphocyte counts returned to control levels but neutrophil counts remained elevated in 1.0 mg/kg ALT-803-treated mice (Fig. 5B). Histopathological analysis verified ALT-803 dose-dependent stimulation of immune cell infiltration and hyperplasia in the spleen, liver, thymus, kidney, lungs and lymph nodes on SD26, and to a lesser degree on SD36. Similar results were observed in a second study where C57BL/6 mice were treated with four weekly ALT-803 doses and assessed on SD26 and SD50 (i.e., 4 weeks post-treatment). The results of these studies define the tolerable dose of multidose ALT-803 treatment of up to 1 mg/kg in mice in a weekly dosing regimen for 4 weeks.

Figure 5.

ALT-803 treatment changes spleen weight and peripheral blood leukocyte counts in C57BL/6 mice. A, study design schema. C57BL/6 mice (n = 10 males and 10 females/group) were treated with i.v. PBS, 0.1 mg/kg ALT-803 or 1.0 mg/kg ALT-803 once weekly for 4 weeks. Four days after the last injection (day 26), clinical assessments including physical examination, blood chemistry, hematology, gross necropsy, body and organ weight measurements, and histopathology were performed on 5 females and 5 males per group. Similar assessments were performed on the remaining 5 females and 5 males per group 14 days after the last treatment (day 36). B, there were no changes in body weights with treatment, whereas a dose-dependent increase in spleen weight was observed. Dose-dependent changes in absolute numbers of WBCs, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and monocytes were plotted. Bars represent mean ± SE of combined data from male and female mice. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 comparing ALT-803 vs. PBS. Similar results were obtained in a second independent study of C57BL/6 mice treated weekly for 4 weeks with 0.1 or 1.0 mg/kg ALT-803 or PBS and assessed 4 days (n = 10 mice/sex/group) or 4 weeks after the last injection (n = 5 mice/sex/group) (data not shown).

Toxicity, PK and PD profiles of ALT-803 in cynomolgus monkeys

Based on allometric scaling to the tolerable murine dose, the activity and toxicity profiles of multidose i.v. treatment of ALT-803 at 0.1 and 0.03 mg/kg were assessed in healthy cynomolgus monkeys. PK analysis after the first dose estimated the terminal half-life of ALT-803 to be 7.2-8 hours, which did not appear to differ significantly between dose levels (Fig. 6; Supplementary Table S2). The maximum serum concentration (Cmax) of 30 nM for 0.1 mg/kg ALT-803 was consistent with full recovery of the administered dose, whereas Cmax and AUCINF values indicated ~30% less recovery at the 0.03 mg/kg dose. However, even at the low dose level, the Cmax of 6 nM in the serum was >50-fold higher than the 0.1 nM concentration found to stimulate immune cell proliferation and activation in vitro.

Figure 6.

Pharmacokinetics of ALT-803 in cynomolgus monkeys. Serum concentrations of ALT-803 were evaluated in blood samples obtained from cynomolgus monkeys (n = 5/sex/group) pre-dosing and at 0.5, 2, 4, 8, 24, and 48 hours following a single i.v. dose of 0.03 mg/kg or 1.0 mg/kg ALT-803. The symbols represent the mean concentration ± SE of ALT-803 in the serum of each animal analyzed independently.

Monkeys receiving 4 consecutive weekly injections of ALT-803 showed a dose-dependent reduction in appetite during the first 2 weeks. However, there were no significant differences in mean body weights or any other dose-related clinical or behavioral observations among the groups. Additionally, organ weights were not significantly different in ALT-803-treated animals compared to controls (summarized in Supplementary Table S3).

The most biologically relevant changes observed after weekly ALT-803 treatment were dose-dependent increases in peripheral blood WBC and lymphocyte counts (Fig. 7A). After the 4-week dosing period (SD26), animals receiving 0.1 mg/kg ALT-803 showed a 1.5-fold increase in absolute lymphocyte numbers which returned to control levels following a 2-week recovery period (SD36). Of the lymphocyte subsets, transient dose-dependent increases in NK cell and CD4+ and CD8+ T cell counts were seen post-treatment (Fig. 7B). Increased peripheral blood monocyte counts were observed in 0.1 mg/kg ALT-803-treated monkeys whereas peripheral blood neutrophil levels were not different among the treatment groups.

Figure 7.

ALT-803 administration increases peripheral blood cell counts of lymphocyte subsets in cynomolgus monkeys. A and B, cynomolgus monkeys (n = 5/sex/group) were injected i.v. (days 1, 8, 15, and 22) with PBS, 0.03 mg/kg ALT-803, or 0.1 mg/kg ALT-803 once weekly for 4 consecutive weeks. Blood was collected pre-dosing and 4 days after the first and fourth dose (i.e., days 5 and 26, respectively) and 14 days after completion of treatment (i.e., day 36). Blood samples were evaluated for changes in absolute cell numbers for leukocyte (A) and lymphocyte subsets (B). The symbols represent the mean ± SE of combined data from male and female animals. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 comparing ALT-803 vs. PBS. C and D, in a second independent study, cynomolgus monkeys (n = 2) were injected i.v. days 1, 8, 15, and 22 (indicated by arrows) with 0.1 mg/kg ALT-803 once weekly for 4 consecutive weeks. Blood was taken on days −4, 1 (predosing), 6, 8 (predosing), 13, 15 (predosing), 20, 22 (predosing), 27 and 29. Cells were stained with antibodies to CD3, CD8, CD45, CD20, CD14, CD16 and CD56 for NK cells, gating on CD14−, CD45+, CD3−, CD20−, CD16+, and CD56− cells. For CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, antibodies to CD3, CD4, CD8 were used as well as CD28 and CD95 for staining of memory subsets (46). Absolute cell counts were calculated from the percentage of the particular cell subset from total cells and the white blood cell (WBC) count. C, absolute blood cell counts during the ALT-803 treatment course were determined for WBC, lymphocytes, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, NK cells and naïve, central memory and effector memory phenotypes for each of the CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets. D, cell proliferation was determined as percentage of Ki-67-positive cells based on the lymphocyte subsets described in panel C. The symbols represent the mean ± range.

In addition, there was a dose-dependent increase in mild multifocal lymphocytic infiltration in the liver, kidneys, and lungs of ALT-803-treated monkeys based on histopathology analysis conducted on SD26 (Supplementary Table S4). Scattered mild liver necrosis was also observed with increased frequency in ALT-803-treated animals. Clinical chemistry at this time point showed a decrease in serum albumin in the high-dose ALT-803 group compared to controls, which may be a consequence of inflammatory responses in the liver. However, serum liver enzymes were not elevated in ALT-803-treated animals compared to controls. Bone marrow hyperplasia was observed in most animals, and increased in severity in the high-dose ALT-803-treated group. Lesions in the majority of affected organs in the ALT-803-treated groups were reduced in incidence and severity by SD36 and were consistent with findings in the control animals.

Eight of 20 animals in the ALT-803 treatment groups developed detectable anti-ALT-803 antibodies after multidose treatment. The pharmacologic consequences of these responses are unclear since there were no post-dosing allergic reactions or effects on ALT-803-mediated responses in animals that developed anti-ALT-803 antibodies.

The effects of ALT-803 on T cell subpopulations were also assessed in cynomolgus monkeys receiving 4 consecutive weekly injections at 0.1 mg/kg. Consistent with the results describe above, multidose ALT-803 treatment resulted in an increase in blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cell and CD16+ NK cell counts over the treatment course (Fig. 7C). Of the CD8+ T cells, effector memory (EM) and to a lesser extent central memory (CM) T cell counts increased shortly after treatment initiation, whereas naïve CD8+ T cell counts were elevated compared to predose counts as the 4-week treatment course proceeded. Similarly, naïve, CM and EM CD4+ T cell counts were elevated after the first dose of ALT-803 resulting in an approximately 3-fold increase in blood CD4+ T cells. The changes in blood lymphocyte counts were associated with increased expression of the proliferation marker Ki-67 in CD16+ NK cells and memory CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (Fig. 7D), indicating the ALT-803-mediated effects are due to increased cell proliferation rather than merely redistribution. Assessment of serum samples collected in this study indicated that there was no significant induction of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-5, IL-4 or IL-2 levels during the 4-week ALT-803 treatment course. Overall, the observed changes in peripheral blood and tissue lymphocytes after ALT-803 treatment of cynomolgus monkeys were consistent with transient effects reported for NHPs treated with IL-15 twice weekly at up to 0.1 mg/kg or daily at 10 to 50 μg/kg (17, 28, 29).

Discussion

In the present study, we assessed the in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy, toxicity and pharmacodynamic profiles of an IL-15 superagonist fusion protein complex, ALT-803 (IL-15N72D:IL-15RαSu/Fc), in animal models to provide the rationale for the initial clinical dose regimen. We have previously found that treatment of mice with a single i.v. dose of ALT-803 resulted in significant increases in spleen weight and CD8+ T cell and NK cell counts that were not observed after IL-15 treatment (23). Moreover, a single dose of ALT-803, but not IL-15 alone, effectively eliminated well-established murine myeloma in the bone marrow of tumor-bearing mice (31). Extending these findings to solid tumor models, we found that ALT-803 (even at less than 10% of cumulative cytokine concentrations) was more efficacious than IL-15 for antitumor responses in mice bearing s.c. B16 melanoma tumors or CT26 colon carcinoma metastases. These effects were likely due in part to the >20-fold longer in vivo half-life of ALT-803 compared to IL-15 (23).

The results of biodistribution experiments reported here confirm the hypothesis that the pharmacological properties of ALT-803 are highly differentiated from IL-15. Consistent with previous reports using 125I-labeled IL-15 (38), 64Cu-IL-15 was very rapidly cleared from circulation with the kidney as the major site of IL-15 accumulation. 64Cu-labeled IL-15 also showed low uptake by the liver and lymph nodes and little or no retention by other tissues. The poor bioavailability of intravenously administered IL-15 in lymphoid tissues and its rapid clearance have been important factors in determining the optimal immunostimulatory treatment regimens of IL-15, which have focused on daily or continuous i.v. administration (17, 42). In contrast, the biodistribution of 64Cu-labeled ALT-803 showed significantly longer circulation in the blood, lower kidney uptake, and much broader and prolonged accumulation in multiple tissues. Particularly, quantitative PET imaging showed about 5-fold higher amounts of 64Cu-ALT-803 in the liver compared to that of 64Cu-IL-15 at 1.5 to 6 hours post-injection. Additionally, the spleen, lungs and lymph nodes had elevated uptake of ALT-803 (i.e. >4 %ID/g) at 6 hours post-injection and lymph node localization persisted without diminishing for at least 70 hours after treatment. Thus, ALT-803 is distributed to and retained in the lymphoid organs to a greater extent than IL-15, which is consistent with its more potent immunostimulatory activity in vivo.

In mice, maximal immune cell stimulation occurs 4 days after ALT-803 dosing, suggesting that once or twice weekly administration of ALT-803 may be suitable for initial clinical testing (23, 31). Dose-ranging studies of four weekly ALT-803 i.v. injections in C57BL/6 mice showed progressively increased immunologic effects from 0.1 mg/kg to 4.0 mg/kg. At the intermediate 1.0 mg/kg ALT-803 dose, parallel increases in mouse spleen weight and peripheral blood cell counts for lymphocytes, neutrophils and monocytes were observed. Consistent with the pattern of ALT-803 tissue biodistribution, immune cell infiltration and hyperplasia were seen in the spleen, liver, thymus, kidney, lungs, and lymph nodes. Treatment with 4.0 mg/kg ALT-803 resulted in mortality of about half of the mice 4 to 6 days after the initial dose. Similar mortality due to NK cell–mediated acute hepatocellular injury was recently reported in mice receiving four daily 11 μg/dose (~0.5 mg/kg) injections of pre-associated murine IL-15:IL-15Rα/Fc complex (41). However, similar toxicity was not apparent in 1.0 mg/kg ALT-803-treated mice, as serum liver enzyme concentrations were comparable to controls. Overall, the 1.0 mg/kg ALT-803 dose showed tolerable but significant immune cell stimulation in mice when given as a weekly treatment. In comparison, a single injection of 0.05 mg/kg ALT-803 had potent antitumor activity in 5T33 myeloma-bearing C57BL/6 mice, suggesting that the therapeutic window of ALT-803 spans a more than 20-fold dose range (31).

Consistent with these observations, multidose ALT-803 administration to cynomolgus monkeys resulted in dose-dependent increases in peripheral blood lymphocytes, primarily NK and CD8+ and CD4+ memory T cells, as well as lymphocytic infiltration in the liver, kidneys and lungs. Modest or no treatment-dependent effects were seen with other blood cell types. These results contrast with previous studies of IL-15 administration to macaques and rhesus monkeys where the major toxicity reported was grade 3/4 transient neutropenia (17, 29). Evaluation of peripheral tissues from IL-15-treated monkeys suggests that this event was due to neutrophil migration from the blood to tissues mediated by an IL-15 initiated IL-18-dependent signaling cascade (17). Consistent with these findings, grade 3/4 neutropenia AEs have been reported for five of nine cancer patients receiving daily i.v. IL-15 infusions at 0.3 μg/kg (43). The lack of ALT-803 effects on peripheral blood neutrophil counts in cynomolgus monkeys may reflect differential sensitivity of these cells to ALT-803 compared to IL-15, a hypothesis that will be further evaluated in in vitro and human clinical studies of ALT-803.

Preclinical studies in animal models have been traditionally used to predict toxicities and determine the initial dose level of immunotherapeutics for clinical trials. However, recent evidence showed that these animal models alone may not be sufficient to predict the safety profiles of immunomodulatory molecules in humans (35, 44). An approach using an in vitro assessment of human immune cells was proposed to supplement the animal models and was employed in this study to further evaluate ALT-803 effects on cytokine release. Comparative studies of human and mouse lymphocytes showed that ALT-803 provided dose-dependent stimulation of IFN-γ release and immune cell proliferation in vitro. These results were consistent with the ability of ALT-803 to stimulate CD8+ T cell proliferation and IFN-γ release in mice bearing myeloma tumors (31). Since the antitumor activity of ALT-803 in this mouse tumor model was dependent on both CD8+ T cells and IFN-γ (31), these responses may be important indicators of potential clinical activity in cancer patients receiving ALT-803 treatment. We also found that ALT-803 at < 0.1 nM could induce activation and cytotoxicity marker expression on human NK and T cells in vitro. However, unlike the mAb to CD3, ALT-803 did not stimulate release of TNF-α, IL-4, or IL-10 by human PBMCs, suggesting that ALT-803 will not trigger a cytokine storm typical of immunostimulatory CD3 or CD28 agonists (35, 44). Supporting this, no induction of serum IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-5, IL-4 or IL-2 was observed after multidose 0.1 mg/kg ALT-803 administration to cynomolgus monkeys.

In dose-ranging toxicology studies, no AEs were observed in mice treated with 0.1 mg/kg ALT-803 or in cynomolgus monkeys treated with 0.03 mg/kg ALT-803, suggesting that human dosing at approximately 10 μg/kg would be justified based on standard allometric scaling approaches (45). In addition, administration of 5 μg/kg ALT-803 is anticipated to achieve a maximum serum concentration of >1 nM (based on the NHP PK studies), which is sufficient to induce significant human T cell and NK cell proliferation and activation in vitro. Based on these results, an initial dose of ALT-803 at 1.0 to 5.0 μg/kg/dose in human clinical trials is expected to provide immune cell stimulation without overt toxicological effects. This range is consistent with that of the recently published dose-escalation study of IL-15 administered daily in patients with metastatic malignancies (43).

In summary, the results of the present study support Phase 1 clinical evaluation of weekly dosing of ALT-803, which has been initiated under FDA-approved clinical protocols for treatment of patients with advanced solid tumors (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01946789), multiple myeloma (NCT02099539) and relapsed hematologic malignancy following allogeneic stem cell transplant (NCT01885897).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Norman H. Altman, V.M.D, and Carolyn Cray, Ph.D., University of Miami, Division of Comparative Pathology, for assistance with the mouse toxicity studies.

Financial support: NCI grants 2R44CA156740-02 and 2R44CA167925-02 to H.C. Wong; NCI grants 1R01CA169365 and P30CA014520, the University of Wisconsin - Madison, and the American Cancer Society 125246-RSG-13-099-01-CCE to W. Cai.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Certain authors are employees and/or shareholders of Altor BioScience Corp. and declare competing financial interests.

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design: P.R. Rhode, H.C. Wong

Development of methodology: J.O. Egan, W. Xu, H.C. Wong, X. Chen, B. Liu, X. Zhu, J. Wen, L. You, L. Kong, A.C. Edwards, S. Shi

Acquisition of data (provided animals, acquired and managed patients, provided facilities, etc.): J.O. Egan, W. Xu, X. Chen, B. Liu, X. Zhu, J. Wen, L. You,, L. Kong, A.C. Edwards, S. Shi, K. Han, G.M. Webb

Analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis): J.O. Egan, W. Xu, X. Chen, B. Liu, X. Zhu, J. Wen, A.C. Edwards, P.R. Rhode, S. Alter, G.M. Webb, J.B. Sacha, E.K. Jeng, W. Cai, H. Hong

Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: P.R. Rhode, J.O. Egan, S. Alter, E.K. Jeng, H.C. Wong

Study supervision: P.R. Rhode, J.B. Sacha, W. Cai, H. Hong, H.C. Wong

References

- 1.Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP, Fisher RI, Weiss G, Margolin K, et al. High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(7):2105–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkins MB, Regan M, McDermott D. Update on the role of interleukin 2 and other cytokines in the treatment of patients with stage IV renal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(18 Pt 2):6342S–6S. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-040029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarhini AA, Agarwala SS. Interleukin-2 for the treatment of melanoma. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;6(12):1234–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmadzadeh M, Rosenberg SA. IL-2 administration increases CD4+ CD25(hi) Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in cancer patients. Blood. 2006;107(6):2409–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cesana GC, DeRaffele G, Cohen S, Moroziewicz D, Mitcham J, Stoutenburg J, et al. Characterization of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients treated with high-dose interleukin-2 for metastatic melanoma or renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(7):1169–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sim GC, Martin-Orozco N, Jin L, Yang Y, Wu S, Washington E, et al. IL-2 therapy promotes suppressive ICOS+ Treg expansion in melanoma patients. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(1):99–110. doi: 10.1172/JCI46266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheever MA. Twelve immunotherapy drugs that could cure cancers. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:357–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sim GC, Radvanyi L. The IL-2 cytokine family in cancer immunotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014;25(4):377–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waldmann TA. The biology of interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: implications for cancer therapy and vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(8):595–601. doi: 10.1038/nri1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldmann T, Tagaya Y, Bamford R. Interleukin-2, interleukin-15, and their receptors. Int Rev Immunol. 1998;16(3-4):205–26. doi: 10.3109/08830189809042995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubois S, Mariner J, Waldmann TA, Tagaya Y. IL-15Ralpha recycles and presents IL-15 In trans to neighboring cells. Immunity. 2002;17(5):537–47. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00429-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanjabi S, Mosaheb MM, Flavell RA. Opposing effects of TGF-beta and IL-15 cytokines control the number of short-lived effector CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;31(1):131–44. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon SR, Kim TD, Choi I. Understanding of molecular mechanisms in natural killer cell therapy. Exp Mol Med. 2015;47:e141. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcais A, Cherfils-Vicini J, Viant C, Degouve S, Viel S, Fenis A, et al. The metabolic checkpoint kinase mTOR is essential for IL-15 signaling during the development and activation of NK cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(8):749–57. doi: 10.1038/ni.2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang M, Li D, Chang Z, Yang Z, Tian Z, Dong Z. PDK1 orchestrates early NK cell development through induction of E4BP4 expression and maintenance of IL-15 responsiveness. J Exp Med. 2015;212(2):253–65. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munger W, DeJoy SQ, Jeyaseelan R, Sr., Torley LW, Grabstein KH, Eisenmann J, et al. Studies evaluating the antitumor activity and toxicity of interleukin-15, a new T cell growth factor: comparison with interleukin-2. Cell Immunol. 1995;165(2):289–93. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waldmann TA, Lugli E, Roederer M, Perera LP, Smedley JV, Macallister RP, et al. Safety (toxicity), pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity, and impact on elements of the normal immune system of recombinant human IL-15 in rhesus macaques. Blood. 2011;117(18):4787–95. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoklasek TA, Schluns KS, Lefrancois L. Combined IL-15/IL-15Ralpha immunotherapy maximizes IL-15 activity in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;177(9):6072–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubinstein MP, Kovar M, Purton JF, Cho JH, Boyman O, Surh CD, et al. Converting IL-15 to a superagonist by binding to soluble IL-15Ra. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(24):9166–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600240103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mortier E, Quemener A, Vusio P, Lorenzen I, Boublik Y, Grotzinger J, et al. Soluble interleukin-15 receptor alpha (IL-15R alpha)-sushi as a selective and potent agonist of IL-15 action through IL-15R beta/gamma. Hyperagonist IL-15 × IL-15R alpha fusion proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(3):1612–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508624200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubois S, Patel HJ, Zhang M, Waldmann TA, Muller JR. Preassociation of IL-15 with IL-15R alpha-IgG1-Fc enhances its activity on proliferation of NK and CD8+/CD44high T cells and its antitumor action. J Immunol. 2008;180(4):2099–106. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu X, Marcus WD, Xu W, Lee HI, Han K, Egan JO, et al. Novel human interleukin-15 agonists. J Immunol. 2009;183(6):3598–607. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han KP, Zhu X, Liu B, Jeng E, Kong L, Yovandich JL, et al. IL-15:IL-15 receptor alpha superagonist complex: High-level co-expression in recombinant mammalian cells, purification and characterization. Cytokine. 2011;56(3):804–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epardaud M, Elpek KG, Rubinstein MP, Yonekura AR, Bellemare-Pelletier A, Bronson R, et al. Interleukin-15/interleukin-15R alpha complexes promote destruction of established tumors by reviving tumor-resident CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(8):2972–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bessard A, Sole V, Bouchaud G, Quemener A, Jacques Y. High antitumor activity of RLI, an interleukin-15 (IL-15)-IL-15 receptor alpha fusion protein, in metastatic melanoma and colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(9):2736–45. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ring AM, Lin JX, Feng D, Mitra S, Rickert M, Bowman GR, et al. Mechanistic and structural insight into the functional dichotomy between IL-2 and IL-15. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(12):1187–95. doi: 10.1038/ni.2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu J. IL-15 Agonists: The Cancer Cure Cytokine. J Mol Genet Med. 2013;7:85. doi: 10.4172/1747-0862.1000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller YM, Petrovas C, Bojczuk PM, Dimitriou ID, Beer B, Silvera P, et al. Interleukin-15 increases effector memory CD8+ T cells and NK Cells in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Virol. 2005;79(8):4877–85. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.4877-4885.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berger C, Berger M, Hackman RC, Gough M, Elliott C, Jensen MC, et al. Safety and immunologic effects of IL-15 administration in nonhuman primates. Blood. 2009;114(12):2417–26. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-189266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lugli E, Goldman CK, Perera LP, Smedley J, Pung R, Yovandich JL, et al. Transient and persistent effects of IL-15 on lymphocyte homeostasis in nonhuman primates. Blood. 2010;116(17):3238–48. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu W, Jones M, Liu B, Zhu X, Johnson CB, Edwards AC, et al. Efficacy and mechanism-of-action of a novel superagonist interleukin-15: interleukin-15 receptor alpha Su/Fc fusion complex in syngeneic murine models of multiple myeloma. Cancer Res. 2013;73(10):3075–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosario M, Liu B, Kong L, Schneider SE, Jeng EK, Rhode PR, et al. The IL-15 Superagonist ALT-803 Enhances NK Cell ADCC and in Vivo Clearance of B Cell Lymphomas Directed By an Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibody. Blood. 2014;124(21):807. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Hong H, Engle JW, Bean J, Yang Y, Leigh BR, et al. Positron emission tomography imaging of CD105 expression with a 64Cu-labeled monoclonal antibody: NOTA is superior to DOTA. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hong H, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Engle JW, Barnhart TE, Nickles RJ, et al. Positron emission tomography imaging of CD105 expression during tumor angiogenesis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38(7):1335–43. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1765-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stebbings R, Findlay L, Edwards C, Eastwood D, Bird C, North D, et al. “Cytokine storm” in the phase I trial of monoclonal antibody TGN1412: better understanding the causes to improve preclinical testing of immunotherapeutics. J Immunol. 2007;179(5):3325–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wen J, Zhu X, Liu B, You L, Kong L, Lee HI, et al. Targeting activity of a TCR/IL-2 fusion protein against established tumors. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57(12):1781–94. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0504-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu P, Steel JC, Zhang M, Morris JC, Waldmann TA. Simultaneous blockade of multiple immune system inhibitory checkpoints enhances antitumor activity mediated by interleukin-15 in a murine metastatic colon carcinoma model. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(24):6019–28. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi H, Carrasquillo JA, Paik CH, Waldmann TA, Tagaya Y. Differences of biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, and tumor targeting between interleukins 2 and 15. Cancer Res. 2000;60(13):3577–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eisenman J, Ahdieh M, Beers C, Brasel K, Kennedy MK, Le T, et al. Interleukin-15 interactions with interleukin-15 receptor complexes: characterization and species specificity. Cytokine. 2002;20(3):121–9. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carson WE, Yu H, Dierksheide J, Pfeffer K, Bouchard P, Clark R, et al. A fatal cytokine-induced systemic inflammatory response reveals a critical role for NK cells. J Immunol. 1999;162(8):4943–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biber JL, Jabbour S, Parihar R, Dierksheide J, Hu Y, Baumann H, et al. Administration of two macrophage-derived interferon-gamma-inducing factors (IL-12 and IL-15) induces a lethal systemic inflammatory response in mice that is dependent on natural killer cells but does not require interferon-gamma. Cell Immunol. 2002;216(1-2):31–42. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00501-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sneller MC, Kopp WC, Engelke KJ, Yovandich JL, Creekmore SP, Waldmann TA, et al. IL-15 administered by continuous infusion to rhesus macaques induces massive expansion of CD8+ T effector memory population in peripheral blood. Blood. 2011;118(26):6845–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conlon KC, Lugli E, Welles HC, Rosenberg SA, Fojo AT, Morris JC, et al. Redistribution, hyperproliferation, activation of natural killer cells and CD8 T cells, and cytokine production during first-in-human clinical trial of recombinant human interleukin-15 in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(1):74–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romer PS, Berr S, Avota E, Na SY, Battaglia M, ten Berge I, et al. Preculture of PBMCs at high cell density increases sensitivity of T-cell responses, revealing cytokine release by CD28 superagonist TGN1412. Blood. 2011;118(26):6772–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-319780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Food and Drug Administration, HHS Guidance for industry on estimating the maximum safe starting dose in initial clinical trials for therapeutics in adult healthy volunteers. Fed Regist. 2005;70(140):42346. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahnke YD, Brodie TM, Sallusto F, Roederer M, Lugli E. The who's who of T-cell differentiation: human memory T-cell subsets. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43(11):2797–809. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.