Abstract

Recent increases in the incidence of both type 1 (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) in children and adolescents point to the importance of environmental factors in the development of these diseases. Metabolomic analysis explores the integrated response of the organism to environmental changes. Metabolic profiling can identify biomarkers that are predictive of disease incidence and development, potentially providing insight into disease pathogenesis. This review provides an overview of the role of metabolomic analysis in diabetes research and summarizes recent research relating to the development of T1D and T2D in children.

Keywords: autoimmunity, diabetes, lipidomics, metabolomics

Metabolomics is the detection and quantification of the spectrum of small-molecule metabolites measured in a biological sample (1). Analysis of the metabolome represents a quantitative assessment of the integrated changes produced by both endogenous and exogenous factors in a given disease state or in response to specific physiologic changes. There are currently almost 42 000 metabolites registered in the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB; http://www.hmdb.ca). Of these, about 4500 are expected or have been detected in the blood and about 2000 of these have been shown to be measureable. It is postulated that as analytic methods advance, the realm of quantifiable metabolites will continue to grow (2).

The measurement of the spectrum of small molecules comprising the metabolome can present an analytical challenge, as the metabolites within a sample may range in abundance from sub-nanomolar to millimolar concentrations and have varying chemical properties requiring variable analytic approaches. Despite the technical challenges, however, metabolomic analysis has significant advantages in the study of disease pathogenesis. Metabolites typically show more rapid fluctuation in response to a physiologic change than the time frame in which one can detect changes in gene expression or protein production. Furthermore, analysis of metabolites allows for insight into the association between the genes and their functions. Metabolites have the ability to control the function of proteins or expression of genes, their concentrations typically relate directly to activity, and they may represent already-established diagnostic markers (3).

Experimental considerations in metabolomics

Study design

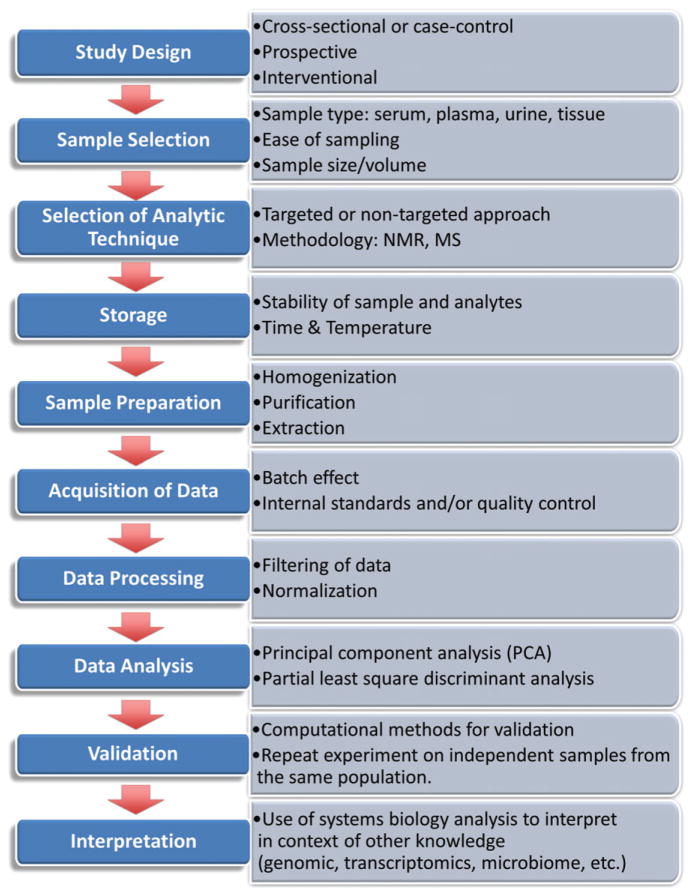

Metabolomic profiling studies can be used to obtain a snapshot in time, such as for comparison of the metabolome in a case–control study (Fig. 1). This type of analysis typically seeks to gain insight into disease development by identification of biomarkers associated with the disease state. While the simplicity of this single time-point approach is attractive, interpretation of disease-associated markers must address the question of whether the association represents a causal relationship, a consequence of the disease state or a result of some other confounding factor (4). Consideration also must be given to the selection of control subjects. The control group is frequently chosen to match for potential confounding factors such as age and sex (5). Alternately, minimizing matching criteria and including potential covariates into statistical models may improve statistical power (6). In contrast to case–control studies, prospective metabolomic studies have a greater potential to identify biomarkers that are predictive of disease incidence and development and thereby address questions of causality and mechanism. Finally, interventional studies can be used to test hypotheses of causality and provide information regarding mechanism.

Fig. 1.

Scheme for Design and Process of Metabolomic Study. NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy; MS: mass spectrometry (10, 89).

Sample selection

The selection of sample for analysis is of particular relevance in pediatric populations where considerations of invasiveness and subject discomfort as well as the availability of blood sample volume may influence study design. This is further relevant in prospective studies where the logistics and subject response to sample collection may influence study participation. The majority of metabolomics studies to date have used blood samples (serum or plasma) or urine; however, analysis of saliva can also yield useful markers, and studies in adults with T2D have identified a marker for glycemic control potentially useful for screening undiagnosed diabetes (7).

Targeted vs. non-targeted approaches

Metabolomic studies may take either a targeted or non-targeted approach. In the targeted design, the study focuses on a specific, predetermined set of metabolites. Targeted studies typically seek to be quantitative and will typically include internal standards for reference and quantitation. The focus on a subset of analytes allows for a more tailored methodologic approach. This may be beneficial in terms of accuracy and sensitivity of the data. The targeted approach has the advantage of producing data which can be compared or combined from a variety of studies.

In contrast, the non-targeted approach is optimized for maximal coverage of all the possible metabolites in the system. Measurements are typically semi-quantitative, may have lower sensitivity and can be less reliable. The non-targeted approach is more optimal for discovery of new or unanticipated metabolites (4). Untargeted metabolomic analysis generates large and complex data sets that require specialized software for analysis of the data. Identification of component metabolites often requires use of large databases such as the HMDB (2). Principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares-discriminant analysis are used to identify patterns associated with the outcome of interest and have been used to identify potential new disease markers (8).

It should be noted that the two strategies are not mutually exclusive and a study may combine both targeted and non-targeted approaches in a complementary fashion. A non-targeted analysis may be used to identify pathways associated with a disease state, followed by targeted evaluation of specific metabolites in these pathways (9). Furthermore, as the field progresses, advances in data mining capabilities as well as analytic techniques continue to improve both the quality and depth of data generated from biological samples as well as the ability to mitigate the limitations of the non-targeted approach (10–12).

Analytic techniques

The most commonly used techniques for metabolomic analysis are high-resolution proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H NMR) and mass spectrometry (MS), typically coupled to some form of chromatography or other type of separation of the sample. Examples of these include gas chromatography (GC-MS), liquid chromatography (LC-MS), ultraperformance liquid chromatography (UPLC-MS), and capillary electrophoresis (CE-MS). The two methodologies present different and complementary strengths.

NMR is chemically non-selective, making it less restrictive in regards to solubility or polarity of the analytes being measured. It has the benefit of requiring only minimal sample preparation and being reproducible across laboratories; however, it is less sensitive and therefore better suited to measurement of more abundant metabolites (10). Furthermore, it typically requires higher sample volumes (4). Each metabolite has a unique pattern of positions and intensities of peaks on its NMR spectrum. The identification of analytes in NMR is based on the deconvolution of complex NMR spectra in order to identify the component analytes. NMR has the additional advantage of providing information on unknown metabolites.

In contrast to NMR, MS-based methods are more sensitive, but often require more elaborate sample extraction methods. In MS-based methods, the chromatography step allows for the stratification of heterogeneous mixtures of metabolites, thus aiding in ease of identification. The combination of multiple analytic strategies for separation, identification and quantification of analytes makes MS-based methods more technically challenging and prone to both artifacts and measurement errors (11). MS-based strategies utilize both known fractionation patterns and high resolution of measured mass in order to identify analytes (12).

Lipidomics

Lipids are hydrophobic or amphipathic compounds that represent a subclass of small-molecule metabolites. As such, lipidomics is a branch of metabolomics, and the techniques involved are closely related (13). Beyond their roles in the structure and function of cell membranes and as a key component of energy storage, lipids have increasingly recognized functions as signaling molecules with implications for pathogenesis of many diseases (14). Lipids have been classified into eight categories by the LIPID MAPS (LIPID Metabolites And Pathways Strategy) database (http://www.lipidmaps.org). These are commonly used for categorization in lipidomic analysis. Six of these groups are carbanion-based condensations of thioesters (fatty acyls, glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, saccharolipids, and polyketides) and two groups are carbocation-based condensations of isoprene units (sterol lipids and prenol lipids) (15).

Sample preparation and storage

Ideal sample preparation for metabolomics analysis must be fast, reproducible, and able to extract metabolites with a wide range of chemical properties (3). Unlike classical sample preparation, which aims to be selective in order to produce a pure extraction, sample preparation for metabolomic analysis aims to be as comprehensive as possible while still yielding a sample that is appropriate for the analytic technique. Consideration must also be given to the storage conditions. Many metabolites are chemically labile and the ability to detect low levels may be affected by both storage conditions and the length of time before assay. For prospective studies, this is of particular importance as storage times may vary significantly among samples.

Interpretation and validation

Metabolomic studies, particularly those with non-targeted design, generate large amounts of complex data on a broad range of metabolites. Proper analysis of such data requires specialized bioinformatics tools and data analysis methods, reviewed recently by Alonso et al. (16). An important consideration in statistical analysis is the problem of multiple comparisons leading to a high probability of false positives. There are various statistical correction methods including the more conservative Bonferroni correction or less conservative approaches based on minimization of the false discovery rate. (17). Emerging analytic techniques use Bayesian inference instead of the frequentist approach to discover associations, abandoning the p-value paradigm in favor of measures of association. (18, 19)

Given the challenges involved in analysis and potential for false positives, assessment and validation of metabolomics findings are of particular importance. Biomarkers identified via metabolomics analysis can be evaluated by performance assessment using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The area under the curve (AUC) metric gives the probability that a randomly selected patient will have a higher test result than a randomly selected control. There are computational methods for biomarker model validation using iterative evaluation of subsets of the data set via permutation-based validation or cross-validation (16). Ideally, however, validation should be performed by replication of the results with independent samples from the same target population.

Considerations for pediatric studies

Understanding the development of disease in pediatric populations is well suited to a systems-based approach, given the potential for complex and variable contributing factors. Prenatal factors influencing disease development include not only the genetic contribution of the parents, but also intra-uterine influences such as maternal health, nutrition, weight, and environmental exposures (20). Furthermore, the health and function of the placenta can also influence prenatal growth and development (21). Early childhood factors, particularly in regards to feeding, environmental exposures, and infections all play a role in the evolving health and physiology of the young child. The gut microbiome is particularly intriguing as it is not only influenced by many of the above-mentioned factors, but it also exerts an influence on the physiology and the metabolome of the child (20). Finally, age and the onset of pubertal hormones may have an impact on the evolution of disease states.

Metabolomic analysis is well-poised to provide insight into the pathogenesis of diseases such as type 1 (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) in which an interplay of genetic risk factors and environmental triggers appear to be involved in both onset and development of disease (10). Changing environmental factors in recent decades resulted in increasing incidence among youth of both T1D and T2D (22, 23). While there has been a significant amount of data published on metabolomic analysis of the development of insulin resistance and T2D in adults, the studies in T1D and in the pediatric population in general are more limited. The goal of this review is to provide an overview of recent metabolomics research relating to the development of T1D and T2D in children.

Obesity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes

The increasing incidence of T2D in youth has become a significant worldwide public health problem (23). Early childhood factors, including early obesity and prenatal conditions, may play an important role in the pathogenesis of T2D in adolescence and adulthood (24–26). Insulin resistance is an important component of progression to T2D and is the focus of much of the research in youth. To date, metabolomic analysis has been utilized in only a handful of studies in obese, insulin resistant or T2D youth (Table 1).

Table 1.

Metabolomic studies of pediatric and adolescent obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes

| Disease/condition | Study design | Tissue | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity | Cross-sectional cohort: NW (n = 40) OB (n = 80) |

Serum | OB vs NW:

|

31 |

| Obesity and weight loss intervention | Cross-sectional cohort: OB, weight loss (n = 40) OB, stable weight (n = 40) |

Serum | Weight loss predicted by:

|

34 |

| Obesity and weight loss intervention | Cross-sectional cohort of OB: Weight loss (n = 80) Stable weight (n = 80) |

Serum | Weight loss associated with:

|

35 |

| Obesity and IR | Cross-sectional cohort: OB (n = 82) |

Plasma | BCAA: Males >Females (similar BMI) In males, HOMA-IR correlated:

In females, HOMA-IR correlated:

Adiponectin correlated inversely with BCAA and uric acid in males, but not females |

43 |

| Obesity and T2D | Case–control: NW (n = 39) OB (n = 64) OB T2D (n = 17) |

Plasma | T2D vs OB/NW:

T2D/OB vs NW:

No differences in fasting FFA levels |

37 |

| Obesity, IR, T2D | Case–control: NW (n = 38) OB (n = 57) OB prediabetes (n = 27) OB T2D (n = 17) |

Plasma | BCAA and BCAA intermediates correlated: positively with IS and DI | 42 |

| Obesity and IR | Cross-sectional study (n = 69) Longitudinal cohort study in subset (n = 17) |

Plasma | ↑ BCAA in OB vs. NW ↑ BCAA not associated with measures of insulin resistance at baseline Baseline BCAAs predicted HOMA-IR at 18 months |

44 |

AcylCN, acylcarnitines; BCAA, branched chain amino acids; FFA, free fatty acids; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; IR, insulin resistance; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry; NW, normal weight; OB, obese; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Elevations in amino acids, particularly branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs: leucine, isoleucine, and valine) as well as the aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine and tyrosine) have been described in adults with obesity and T2D (27–29). Longitudinal studies have shown that elevations in BCAAs predict insulin resistance and onset of T2D (29, 30). Studies in adults showed that BCAAs inhibit insulin signaling and influence the rate of glucose utilization (30); however, little was known until recently regarding the role of BCAAs in youth.

Targeted serum metabolomics analysis of a large cohort of obese (OB) and normal weight (NW) children and adolescents in Germany showed that BCAAs were lower in OB youth, in contrast to findings in adults, but this change was not significant when adjusted for multiple comparisons (31). There were higher concentrations of a medium- and long-chain acylcarnitine (C12:1 and C16:1) in OB relative to NW children, consistent with findings in adults (32) and possibly reflecting a defect in β-oxidative capacity in the face of the elevated fatty acid load in obesity. Acyl-alkyl phosphatidylcholine (PCae) concentrations were lower in the OB children. This includes the subclass of antioxidant plasmalogens and may reflect increased oxidative stress. Additionally, there were changes in some metabolite ratios including increased ratios of saturated lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) to diacyl phosphatidylcholines (PCaa) in OB children. LPCs are derived from PCaa during LDL oxidation and they have pro-atherogenic, pro-inflammatory, and anti-insulin signaling effect.(33) Interestingly, none of the metabolite concentrations showed significant association with pubertal stage, even when adjusted for age.

Two studies additional studies by the same German group used metabolomic analysis to study the predictors and effects of weight loss via an intensive lifestyle intervention (34, 35). Children who lost weight had increases in glutamine, methionine, selected LPCs, and acyl-alkyl PC (PCaeC36:2) (34, 35), all of which had been noted to be lower in the OB children relative to NW (31). Additionally, the baseline levels of glutamine, methionine, and PCae36:2 were all lower in the OB children with substantial weight loss compared to those who did not lose significant amounts of weight.(35) The most robust predictors of weight loss were lower serum concentrations of long-chain unsaturated PCaa and lower waist circumference (34). The authors speculate that the PCaa profile predicting better weight loss is representative of reduced endogenous choline synthesis pathways, while lower waist circumference is associated with a more beneficial adipokine profile (36). These observations hint at potential mechanisms for obesogenic phenotypes and will require further investigation.

In a study of OB non-diabetic and OB T2D adolescents (T2D) compared to NW controls, measures of lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation were higher in OB and T2D youth compared to controls, but did not differ from each other (37). There was no significant difference in long-chain acylcarnitines (AcylCN), but there were lower levels of short- and medium-chain AcylCN in the OB and T2D groups compared to NW controls. This is in contrast to adults who showed elevated AcylCN concentrations associated with obesity and insulin resistance (32, 38, 39). While rates of whole-body lipolysis in OB and T2D youth were about twofold higher than in controls, there were no differences in fasting free fatty acid levels (37). While adults with insulin resistance have been shown to have elevations in BCAAs (30, 39, 40), measured plasma amino acids, including BCAAs, were lower in T2D youth compared to both OB and NW groups. Furthermore, the levels of BCAA-derived AcylCN species were also lower in T2D adolescents (37).

Another study of OB and NW adolescents looked at insulin sensitivity (IS) as measured by the hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic clamp technique in addition to measurement of first-phase insulin secretion via the hyperglycemic clamp method. The disposition index (DI) is a measure of β-cell function relative to IS, and lower DI has been shown to predict development of T2D in adults (41). Contrary to what would be predicted from adult studies, however, there were positive associations between IS and BCAA as well as the BCAA-derived intermediates C4 and C5 acylcarnitine, methionine, and tyrosine, but these associations disappeared with adjustment for age, race, sex, BMI, and Tanner stage (42). Furthermore, DI was positively associated with elevation in the BCAA and BCAA intermediates, methionine, and tyrosine, but this also disappeared after adjustment (42). Another study of OB adolescents (ages 12–18 yr) used PCA to consolidate an array of metabolites into 17 components. Multivariate linear regression analyses showed that, independent of age, sex, and BMI z-score, HOMA-IR was related to a metabolic signature containing BCAA and uric acid. When stratified by sex, this relationship held for males, but not females (43).

A fourth cohort was examined at baseline and a subset of pre- or early-pubertal children were then followed prospectively for 18 months. At baseline, BCAA levels were positively associated with BMI z-score and measures of central adiposity but not the HOMA-IR measure of insulin resistance.

Interestingly, BCAA and other amino acids at baseline predicted HOMA-IR at 18 months follow-up (44). These relationships held when adjusted for adjusted to race, ethnicity, caloric intake, physical activity, family history of T2D, Tanner stage, and IGF-1 level. The discrepancy between adult and pediatric findings with regards to the relationship of BCAAs with insulin resistance may be due to the effect of chronic exposure, potentially exerting damaging effects on the β-cell. This could explain the lack of association in the previously-described cross-sectional studies, but the predictive value seen in this study over time. Furthermore, there may be additional effects of pubertal hormone changes that remain to be elucidated as there seems to be a gender-dependent relationship between IR and BCAA in at least one study (43). These studies point to the potential importance of age and developmental effects on progression of insulin resistance and T2D.

While limited data exist to date in children, many more markers of insulin resistance and T2D have been identified in adult studies including gluconeogenesis intermediates, carbohydrate derivatives, ketone bodies, amino acid derivatives, composition, and saturation of fatty acids (28, 39, 45, 46). Of these, in addition to BCAA, several other metabolites have been shown to both positively and negatively predict later development of dysglycemia and T2D (27, 47–50). Additional studies in children will be necessary to determine whether these factors play a role in early-life risk for T2D.

Type 1 diabetes

Metabolomic predictors of long-term complications

Hyperglycemia and relative insulinopenia characteristic of the T1D milieu profoundly alter metabolic homeostasis. Multiple metabolites affected by the variable insulin and glycemic levels may theoretically help to predict the risk of long-term complications. Balderas et al. compared the urine and serum metabolome from 34 children with well-controlled diabetes with that of 15 non-diabetic controls (51). Children with T1D had altered bile acid profile. As the bulk of bile acids are absorbed during enterohepatic circulation rather than generated de novo, this may reflect changes in the gut microbiome associated with T1D. There were also changes noted in some phospholipids and a group of sphingolipids – classes of lipid mediators which play a role in regulation of inflammation and immunity (52).

Increased levels of non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) were seen in the T1D children, but were not paralleled by any increase in triacylglycerols. As the NEFA are known to be associated with increased insulin resistance (53), this may have implications for development of complications. This is of particular relevance as T1D youth have insulin resistance, impaired exercise capacity and cardiovascular dysfunction when compared to non-diabetic controls matched for age, pubertal stage, activity level, and BMI. (54)

The urine metabolome of children with T1D showed changes that mostly highlighted changes in excretion of amino acids, including modified amino acids, potentially reflecting increased rates of protein catabolism. Overall, the lipid and protein catabolism changes in T1D children relative to controls may be related to relative insulinopenia and oxidative stress. It is unclear to what degree the observed changes in metabolomic measures are a result of the pathogenesis of T1D and to what degree they result from the presence of other factors such as hyperglycemia. A comparison of T1D in poor vs. good glycemic control may help in addressing this distinction. Future larger studies are needed to determine whether metabolomics markers can add to the prediction of long-term T1D complications. In addition to playing a role in predicting complications, further characterization of the metabolomics profile associated with disease progression may also lead to important insights into the pathogenesis of complications of diabetes.

Metabolomic predictors of islet autoimmunity and progression to overt diabetes

The incidence of T1D has shown a steady increase in recent decades (22). As the rate of change in incidence cannot be explained by genetic alterations in the population, addressing this growing trend will require improved understanding of disease pathogenesis and the role environmental factors play in the development and progression of autoimmunity. Islet autoantibodies are the markers of future development of T1D (55). While over 60% of children who develop islet autoimmunity carry moderate to high-risk human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes, only about 5% of the carriers of these genotypes develop T1D (56). The appearance of islet autoantibodies (seroconversion from negative to positive) is the first detectable sign of the sub-clinical progressive β-cell damage, often followed by spread to additional autoantibodies. It is likely that interventions must be aimed at preventing or modulating exposures prior to initial seroconversion in order to prevent eventual progression to T1D. Better understanding of the metabolic events preceding seroconversion may yield interventions which can slow or stop autoimmunity, once started. The times preceding and surrounding onset of autoimmunity as well as the development of overt T1D are therefore important time points for focused study. Metabolomic studies examining the progression to T1D are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Metabolomic studies of pediatric and adolescent islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes

| Disease/condition | Study design | Specimen | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islet autoimmunity | Case–control: Early seroconversion (≤2 yo), (n = 13) Late seroconversion (≥8 yo), (n = 22) |

Serum | Early development:

|

59 |

| Islet autoimmunity through development of T1D | Prospective study Progressors (n = 56) Non-progressors (n = 73) |

Cord blood Serum |

Progressors:

Before seroconversion and antibody progression:

|

63 |

| Early onset T1D | Case–control: T1D (n = 76) Control (n = 76) |

Cord blood | T1D vs. control:

|

79 |

| T1D | Case–control: T1D (n = 34) Control (n = 15) |

Serum Urine |

Serum:

Urine:

|

51 |

| T1D | Case–control: T1D (n = 33) 3–4 antibodies (n = 31) 2 antibodies (n = 31) 1 antibody (n = 48) Control (n = 143) |

Cord serum | T1D vs control:

|

80 |

CE-MS, capillary electrophoresis–mass spectrometry; GCxGX-TOF/MS, two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled to time-of-flight mass spectrometry; LC-MS, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry; MS/MS, tandem mass spectrometry; NEFA, non-esterified fatty-acids; PCs, phosphatidylcholines; PEs, phosphatidylethanolamines; SMs, sphingomyelins; UPLC-MS, ultraperformance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry.

Lipidomic and metabolomic analyses have been used to test a hypothesis that early vs. late development of islet autoantibodies represent different mechanisms of autoimmune activation. Children developing autoantibodies later have more often low-affinity antibodies and progress more slowly to multiple antibodies and T1D than those with early-onset autoimmunity (57, 58). The BABYDIAB cohort of children with at least one T1D parent (59) has been followed prospectively since birth. Subjects for metabolomics analysis were grouped into those with onset of islet autoantibodies either early (≤2 yr of age) or late (≥8 yr of age); a control group, matched for age, date of birth, and HLA genotype, was also included. Serum samples were analyzed from time of first autoantibody positivity as well as 1 yr later. Children with islet autoantibodies had lower abundance of methionine and hydroxyproline as well as higher levels of selected phospholipids and triglycerides (TGs) (59). These differences persisted after adjustment for HLA genotype, fasting status, and age at sample collection. Analysis of samples 1 yr after antibody positivity showed persistence of the group differences.

Children with early onset of autoantibodies had lower levels of methionine than those who developed IA late, and this difference did not appear to be strictly age-related as the control subjects showed no significant difference with age (59). In contrast, the elevation in selected lipids did not appear to vary between early- and late-onset antibody groups (59). Methionine is also noted to be lower in diabetic NOD mice (60). It is a key intermediate in transmethylation reactions and in the catabolism of choline, a major component of phospholipids. Methionine is a precursor to other sulfur-containing amino acids such as cysteine and taurine. Finally, methionine is a source of methyl groups for DNA methylation. It is essential for lymphocyte proliferation (61) and the amino acid starvation response plays a role in the regulation of T helper 17 cell differentiation (62). In addition to the metabolomic changes related to autoimmunity, this study identified multiple changes in both amino acid and lipid profiles which occurred with age, regardless of autoimmune status, including an increase in glutamine levels over time. This raises the potential for a confounding effect of age on metabolomic analyses of such analytes (59). Non-targeted metabolomic investigation of the Finnish Type 1 Diabetes Prediction and Prevention Project (DIPP) cohort examined the lipidome and metabolome from cord blood and serum samples of children with high-risk HLA genotypes who progressed to T1D (progressors) compared to matched controls who did not develop islet autoantibodies or progress to T1D (63). In the first year of life, TGs and multiple phospholipids were lower in progressors (63), and this finding was later replicated in the NOD mouse model of diabetes (64). Specifically, the ether phospholipid ethanolamine plasmalogen was noted to be lower in progressors (63). Plasmalogens (ether PCs) protect mammalian cells from the damaging effects of reactive oxygen species (65). As important antioxidants, this alteration in the phospholipid profile may indicate a susceptibility to oxidative damage in the pancreatic β-cell. Perhaps consistent with this, at high concentrations, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is preferentially incorporated into the ethanolamine plasmalogen phospholipids (66), and higher dietary intake of DHA has been reported as associated with a decreased risk of autoimmunity (67) and T1D (68).

In contrast, the most abundant proinflammatory LPC, lysoPC(18:0/0:0) (1-stearoyl-glycero-3-phosphocholine), was elevated in progressors during the first 2 yr of life with a peak prior to development of autoantibodies. Again, the NOD mouse model showed similar elevations in lysoPC associated with the time of seroconversion (64). Elevation of lysoPCs could be associated with increased oxidative stress from a viral infection or other proinflammatory events (69). It is interesting to note that the increase in the proinflammatory lysoPC just prior to seroconversion is paralleled by findings in the BABYDIET study, which have used gene microarray analysis to identify a signature inflammatory response in peripheral blood mononuclear cells at a corresponding time in T1D pathogenesis (70).

Additional metabolomic findings noted in the months preceding autoantibody appearance included low abundance of metabolites of the citric acid cycle at birth and during the first year of life in progressors relative to controls (63). These metabolites, including succinic acid (71), are influenced by the gut microbiome and may represent effects of infant metabolome on development of islet autoimmunity (72). The potential role of gut microbiota in development of T1D is supported by studies in humans (73) and mice (64), which show alterations in microbiome diversity associated with progression to T1D. This active area of research has been recently reviewed elsewhere (74–76).

Higher abundance of glutamic acid and branched chain amino acids (BCAAs) and lower abundance of ketoleucine (a product of BCAA catabolism), preceded appearance of autoantibodies. Glutamic acid is broken down by glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), another target of autoimmunity. BCAAs have been shown to increase insulin secretion (77), implying a possible impairment of insulin secretion at this stage of disease progression. The importance of these findings is unclear until independently confirmed; however, they are supported by findings in NOD mice which show increased BCAA in diabetic mice (60, 78) and mice at high risk of progression to diabetes (64).

A Swedish cohort study, the Diabetes Prediction in Skåne (DiPiS), also used umbilical cord blood lipidomic analysis to identify possible risk markers for early development of T1D. In this study, 76 children who developed T1D before 8 yr of age were matched to 76 healthy subjects for HLA risk, sex, and date of birth as well as mother’s age and gestational age (79). A total of 106 lipid metabolites from cord-blood samples were identified and using PCA, were analyzed for predictive ability. The best predictive model was achieved for children younger than 2 yr of age at diagnosis, while the groups of children older than 4 yr at diagnosis could not be modeled (79). In the children developing T1D before age 4, lower levels cord-blood phospholipids (phosphatidylcholines, phosphatidylethanolamines, and sphingomyelins) all predicted development of T1D while TGs predicted T1D in children before 2 yr of age. These results were replicated in a study of cord blood from children in the DIPP study, which also showed higher risk of progression to T1D associated with lower levels of choline-containing phospholipids, including sphingomyelins and phosphatidylcholines (80).

The metabolomic studies to date present several leads for a search for the environmental factors responsible for triggering of islet autoimmunity and involved in the increasing incidence of T1D. The alterations in cord-blood lipoprotein profiles noted in both the DIPP and DiPiS studies suggest that the intra-uterine environment may affect T1D risk. Furthermore, the other early metabolomic changes may reflect specific alterations in the infant’s microbiome. Other lipidomic and metabolomic changes noted preceding development of autoimmunity may reflect the activation of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mechanisms in early islet autoimmunity. While fascinating, these findings have to be interpreted with caution as the studies to date have been very small and remain to be replicated. Furthermore, the observation that age plays a role in the metabolic findings related to progression to autoimmunity (59) underlines the need for consideration of age and other potential confounders in study design. Integration of metabolomic findings with knowledge gleaned from genetic, transcriptomic, and proteomic studies (81, 82) as well as findings from mouse model systems (64) may lead to further delineation of critical pathways.

Future directions

The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study seeks to replicate and expand on previous metabolomic findings by prospectively following a multinational cohort of 8676 high-risk children enrolled before 4.5 months of age to identify environmental triggers of T1D (83). These subjects were identified based on newborn screening for high-risk HLA-DR-DQ genotypes and consist of both first degree relatives of a parent or sibling with T1D as well as children screened from the general public. Of the total TEDDY cohort, a nested case–control study for both development of persistent autoimmunity (n = 418) and development of T1D (n = 114) was designed based on case status as of 31 May 2012 at median age of follow up of 40 months (84). For metabolomic analysis, the cases were matched to controls 1:3 by clinical center, gender and family history of T1D, with an eye toward choosing controls with maximum sample availability. Plasma samples collected approximately every 3 months from birth through time to event will be profiled for each subject using approximately 13 000 samples for the entire nested case–control study. As this number of samples cannot be run on a single day, the study was carefully designed to minimize batch effect, including a set of blinded cases and their matched controls in each batch as well as quality control samples in each set to help assess for batch effects (84). The power of the TEDDY study to identify metabolomic signatures for the development of islet autoimmunity and progression to T1D will be enhanced by the parallel investigations of dietary biomarkers, gene expression and stool and plasma microbiome and viral metagenomics in the same case–control group. The sheer quantity of data and concurrent datasets from multiple omics approaches, will present an unprecedented analytical challenge but has the potential to greatly enhance our understanding of the pathogenesis of autoimmunity and T1D.

Summary

In summary, metabolomics is a powerful tool for investigation of the nature/nurture relationships involved in the development of pediatric diabetes, both type 1 and type 2. The ability to generate an assessment of physiologic function at varying stages of the development of disease will assist in better understanding the role of influences that occur during fetal life as well as the response of the young child to the ongoing exposures to environmental influences after birth. Infancy and early childhood is a time of frequent infectious exposures and other stimuli, including relatively rapid changes in dietary intake. The recent increase in the incidence of both T1D and T2D in children and adolescents points to the importance of a better understanding of the environmental factors contributing to the pathogenesis of these conditions.

While metabolomics presents opportunity to generate hypotheses regarding pathomechanisms of disease as well as biomarkers for early detection and monitoring of disease, it will become increasingly important to validate the initial reports in multiple larger studies. Potential confounders of metabolomics findings in pediatric diabetes studies include gender, BMI, and other environmental factors such as medications and diet. Age is an important consideration in pediatric studies, not only because of the profound association with changes in infectious exposure, diet, and activity taking place during the progression from infancy through adolescence, but also because of the large variations in growth hormone and pubertal hormones over time. Pubertal progression plays an important role insulin resistance and development of obesity (85, 86), and adolescence is a time associated with increased incidence of T1D (87) and deterioration in metabolic control of diabetes (88). Studies in those who have T1D or T2D must additionally account for potential confounding effects of metabolic control, diabetic medications and possible co-morbidities. Interpretation of metabolomic studies may be limited by study size and the degree to which potential confounders are addressed. It is also important to keep in mind that metabolomics of serum/plasma or urine provide a relatively narrow window into the intracellular processes and is unlikely to reflect low-grade metabolic pathways localized to, for example, pancreatic islets. Large prospective studies using a systems biology approach with integration of multiple snapshots from omics studies may be able to separate information from noise and identify modifiable pathways paving the way to prevention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation grant 17-2011-277; National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants DK-32493, DK320083, and 5K12DK094712.

References

- 1.Fiehn O. Metabolomics – the link between genotypes and phenotypes. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;48:155–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wishart DS, Jewison T, Guo AC, et al. HMDB 3.0 – the human metabolome database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D801–D807. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coral Arribas. Metabolomics. Electrophoresis. 2013;34:2761–2944. doi: 10.1002/elps.201370184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suhre K. Metabolic profiling in diabetes. J Endocrinol. 2014;221:R75–R85. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Graaf MA, Jager KJ, Zoccali C, Dekker FW. Matching, an appealing method to avoid confounding? Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;118:c315–c318. doi: 10.1159/000323136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faresjö T, Faresjö A. To match or not to match in epidemiological studies – same outcome but less power. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:325–332. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7010325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mook-Kanamori DO, Selim MME-D, Takiddin AH, et al. 1,5-Anhydroglucitol in saliva is a noninvasive marker of short-term glycemic control. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E479–E483. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang JH, Byun J, Pennathur S. Analytical approaches to metabolomics and applications to systems biology. Semin Nephrol. 2010;30:500–511. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunelli L, Ristagno G, Bagnati R, et al. A combination of untargeted and targeted metabolomics approaches unveils changes in the kynurenine pathway following cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Metabolomics. 2013;9:839–852. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orešič M. Metabolomics in the studies of islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes. Rev Diabet Stud. 2012;9:236–247. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2012.9.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahrous EA, Farag MA. Two dimensional NMR spectroscopic approaches for exploring plant metabolome: a review. J Adv Res. 2015;6:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lei Z, Huhman DV, Sumner LW. Mass spectrometry strategies in metabolomics. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25435–25442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.238691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orešič M. Metabolomics, a novel tool for studies of nutrition, metabolism and lipid dysfunction. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;19:816–824. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasuga K, Suga T, Mano N. Bioanalytical insights into mediator lipidomics. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2015;113:151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fahy E, Subramaniam S, Murphy RC, et al. Update of the LIPID MAPS comprehensive classification system for lipids. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S9–S14. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800095-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alonso A, Marsal S, Julià A. Analytical methods in untargeted metabolomics: state of the art in 2015. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2015;3:23. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2015.00023. (available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4350445/) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc Ser B (Stat Methodol) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webb-Robertson B-JM, McCue LA, Beagley N, et al. A Bayesian integration model of high-throughput proteomics and metabolomics data for improved early detection of microbial infections. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2009:451–463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krumsiek J, Suhre K, Illig T, Adamski J, Theis FJ. Bayesian independent component analysis recovers pathway signatures from blood metabolomics data. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:4120–4131. doi: 10.1021/pr300231n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moco S, Collino S, Rezzi S, Martin F-PJ. Metabolomics perspectives in pediatric research. Pediatr Res. 2013;73:570–576. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hay WW. The placenta: not just a conduit for maternal fuels. Diabetes. 1991;40(Suppl):44–50. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.2.s44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence JM, Imperatore G, Dabelea D, et al. Trends in incidence of type 1 diabetes among non-hispanic white youth in the U.S. 2002–2009. Diabetes. 2014;63:3938–3945. doi: 10.2337/db13-1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenbloom AL, Joe JR, Young RS, Winter WE. Emerging epidemic of type 2 diabetes in youth. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:345–354. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.2.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juonala M, Magnussen CG, Berenson GS, et al. Childhood adiposity, adult adiposity, and cardiovascular risk factors. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1876–1885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park MH, Falconer C, Viner RM, Kinra S. The impact of childhood obesity on morbidity and mortality in adulthood: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2012;13:985–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaag A, Brøns C, Gillberg L, et al. Genetic, nongenetic and epigenetic risk determinants in developmental programming of type 2 diabetes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:1099–1108. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Vasan RS, et al. Metabolite profiles and the risk of developing diabetes. Nat Med. 2011;17:448–453. doi: 10.1038/nm.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suhre K, Meisinger C, Doring A, et al. Metabolic footprint of diabetes: a multiplatform metabolomics study in an epidemiological setting. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013953. (available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2978704/) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Würtz P, Soininen P, Kangas AJ, et al. Branched-chain and aromatic amino acids are predictors of insulin resistance in young adults. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:648–655. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newgard CB. Interplay between lipids and branched-chain amino acids in development of insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2012;15:606–614. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wahl S, Yu Z, Kleber M, et al. Childhood obesity is associated with changes in the serum metabolite profile. Obes Facts. 2012;5:660–670. doi: 10.1159/000343204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mihalik SJ, Goodpaster BH, Kelley DE, et al. Increased levels of plasma acylcarnitines in obesity and type 2 diabetes and identification of a marker of glucolipotoxicity. Obesity. 2010;18:1695–1700. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levitan I, Volkov S, Subbaiah PV. Oxidized LDL: diversity, patterns of recognition, and pathophysiology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:39–75. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wahl S, Holzapfel C, Yu Z, et al. Metabolomics reveals determinants of weight loss during lifestyle intervention in obese children. Metabolomics. 2013;9:1157–1167. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reinehr T, Wolters B, Knop C, et al. Changes in the serum metabolite profile in obese children with weight loss. Eur J Nutr. 2014;54:173–181. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0698-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barkin S, Rao Y, Smith P, Po’e E. A novel approach to the study of pediatric obesity: a biomarker model. Pediatr Ann. 2012;41:250–256. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20120525-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mihalik SJ, Michaliszyn SF, Heras J, et al. Metabolomic profiling of fatty acid and amino acid metabolism in youth with obesity and type 2 diabetes evidence for enhanced mitochondrial oxidation. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:605–611. doi: 10.2337/DC11-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams SH, Hoppel CL, Lok KH, et al. Plasma acylcarnitine profiles suggest incomplete long-chain fatty acid beta-oxidation and altered tricarboxylic acid cycle activity in type 2 diabetic African-American women. J Nutr. 2009;139:1073–1081. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.103754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiehn O, Garvey WT, Newman JW, Lok KH, Hoppel CL, Adams SH. Plasma metabolomic profiles reflective of glucose homeostasis in non-diabetic and type 2 diabetic obese african-american women. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tai ES, Tan MLS, Stevens RD, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with a metabolic profile of altered protein metabolism in Chinese and Asian-Indian men. Diabetologia. 2010;53:757–767. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1637-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lyssenko V, Almgren P, Anevski D, et al. Predictors of and longitudinal changes in insulin sensitivity and secretion preceding onset of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:166–174. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michaliszyn SF, Sjaarda LA, Mihalik SJ, et al. Metabolomic profiling of amino acids and b-cell function relative to insulin sensitivity in youth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E2119–E2124. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newbern D, Gumus Balikcioglu P, Balikcioglu M, et al. Sex differences in biomarkers associated with insulin resistance in obese adolescents: metabolomic profiling and principal components analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:4730–4739. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCormack SE, Shaham O, McCarthy MA, et al. Circulating branched-chain amino acid concentrations are associated with obesity and future insulin resistance in children and adolescents. Pediatr Obes. 2013;8:52–61. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gall WE, Beebe K, Lawton KA, et al. alpha-Hydroxybutyrate is an early biomarker of insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in a nondiabetic population. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010883. (available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2878333/) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Würtz P, Mäkinen V-P, Soininen P, et al. Metabolic signatures of insulin resistance in 7,098 young adults. Diabetes. 2012;61:1372–1380. doi: 10.2337/db11-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santaren ID, Watkins SM, Liese AD, et al. Serum pentadecanoic acid (15:0), a short-term marker of dairy food intake, is inversely associated with incident type 2 diabetes and its underlying disorders. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:1532–1540. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.092544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Floegel A, Stefan N, Yu Z, et al. Identification of serum metabolites associated with risk of type 2 diabetes using a targeted metabolomic approach. Diabetes. 2013;62:639–648. doi: 10.2337/db12-0495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang-Sattler R, Yu Z, Herder C, et al. Novel biomarkers for pre-diabetes identified by metabolomics. Mol Syst Biol. 2012;8:615. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferrannini E, Natali A, Camastra S, et al. Early metabolic markers of the development of dysglycemia and type 2 diabetes and their physiological significance. Diabetes. 2013;62:1730–1737. doi: 10.2337/db12-0707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balderas C, Rupérez FJ, Ibañez E, et al. Plasma and urine metabolic fingerprinting of type 1 diabetic children. Electrophoresis. 2013;34:2882–2890. doi: 10.1002/elps.201300062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maceyka M, Spiegel S. Sphingolipid metabolites in inflammatory disease. Nature. 2014;510:58–67. doi: 10.1038/nature13475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carpentier A, Mittelman SD, Bergman RN, Giacca A, Lewis GF. Prolonged elevation of plasma free fatty acids impairs pancreatic beta-cell function in obese nondiabetic humans but not in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2000;49:399–408. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nadeau KJ, Regensteiner JG, Bauer TA, et al. Insulin resistance in adolescents with type 1 diabetes and its relationship to cardiovascular function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:513–521. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu L, Rewers M, Gianani R, et al. Antiislet autoantibodies usually develop sequentially rather than simultaneously. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:4264–4267. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.12.8954025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Achenbach P, Bonifacio E, Koczwara K, Ziegler AG. Natural history of type 1. Diabetes. 2005;54(Suppl 2):S25–S31. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.suppl_2.s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Achenbach P, Koczwara K, Knopff A, Naserke H, Ziegler A-G, Bonifacio E. Mature high-affinity immune responses to (pro)insulin anticipate the autoimmune cascade that leads to type 1 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:589–597. doi: 10.1172/JCI21307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ziegler A-G, Nepom GT. Prediction and pathogenesis in type 1 diabetes. Immunity. 2010;32:468–478. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pflueger M, Seppänen-Laakso T, Suortti T, et al. Age-and islet autoimmunity-associated differences in amino acid and lipid metabolites in children at risk for type 1. Diabetes. 2011;60:2740–2747. doi: 10.2337/db10-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fahrmann J, Grapov D, Yang J, et al. Systemic alterations in the metabolome of diabetic NOD mice delineate increased oxidative stress accompanied by reduced inflammation and hypertriglyceremia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;308:E978–E989. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00019.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chuang JC, Yu CL, Wang SR. Modulation of lymphocyte proliferation by enzymes that degrade amino acids. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;82:469–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb05473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sundrud MS, Koralov SB, Feuerer M, et al. Halofuginone inhibits TH17 cell differentiation by activating the amino acid starvation response. Science. 2009;324:1334–1338. doi: 10.1126/science.1172638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Orešič M, Simell S, Sysi-Aho M, et al. Dysregulation of lipid and amino acid metabolism precedes islet autoimmunity in children who later progress to type 1 diabetes. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2975–2984. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sysi-Aho M, Ermolov A, Gopalacharyulu PV, et al. Metabolic regulation in progression to autoimmune diabetes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002257. (available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3203065/) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brosche T, Platt D. The biological significance of plasmalogens in defense against oxidative damage. Exp Gerontol. 1998;33:363–369. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(98)00014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lagarde M, Calzada C, Véricel E. Pathophysiologic role of redox status in blood platelet activation. Influence of docosahexaenoic acid. Lipids. 2003;38:465–468. doi: 10.1007/s11745-003-1085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Norris JM, Yin X, Lamb MM, et al. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and islet autoimmunity in children at increased risk for type 1 diabetes. JAMA. 2007;298:1420–1428. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.12.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stene LC, Joner G Norwegian Childhood Diabetes Study Group. Use of cod liver oil during the first year of life is associated with lower risk of childhood-onset type 1 diabetes: a large, population-based, case–control study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:1128–1134. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.6.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Knip M, Simell O. Environmental triggers of type 1 diabetes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a007690. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ferreira RC, Guo H, Coulson RMR, et al. A type i interferon transcriptional signature precedes autoimmunity in children genetically at risk for type 1. Diabetes. 2014;63:2538–2550. doi: 10.2337/db13-1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jacobs DM, Deltimple N, van Velzen E, et al. (1)H NMR metabolite profiling of feces as a tool to assess the impact of nutrition on the human microbiome. NMR Biomed. 2008;21:615–626. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wen L, Ley RE, Volchkov PY, et al. Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of type 1 diabetes. Nature. 2008;455:1109–1113. doi: 10.1038/nature07336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kostic AD, Gevers D, Siljander H, et al. The dynamics of the human infant gut microbiome in development and in progression toward type 1 diabetes. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:260–273. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hu C, Wong FS, Wen L. Type 1 diabetes and gut microbiota: friend or foe? Pharmacol Res. 2015;98:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gülden E, Wong FS, Wen L. The gut microbiota and Type 1 Diabetes. Clin Immunol. 2015;159:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.05.013. (available from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1521661615001989) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McLean MH, Dieguez D, Miller LM, Young HA. Does the microbiota play a role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases? Gut. 2015;64:332–341. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang Y, Kobayashi H, Mawatari K, et al. Effects of branched-chain amino acid supplementation on plasma concentrations of free amino acids, insulin, and energy substrates in young men. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2011;57:114–117. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.57.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grapov D, Fahrmann J, Hwang J, et al. Diabetes associated metabolomic perturbations in NOD mice. Metabolomics. 2014;11:425–437. doi: 10.1007/s11306-014-0706-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Torre DL, Seppänen-Laakso T, Larsson HE, et al. Decreased cord-blood phospholipids in young age-at-onset type 1. Diabetes. 2013;62:3951–3956. doi: 10.2337/db13-0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Orešič M, Gopalacharyulu P, Mykkanen J, et al. Cord serum lipidome in prediction of islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:3268–3274. doi: 10.2337/db13-0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jin Y, She J-X. Novel biomarkers in type 1 diabetes. Rev Diabet Stud. 2012;9:224–235. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2012.9.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xie Z, Chang C, Zhou Z. Molecular mechanisms in autoimmune type 1 diabetes: a critical review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2014;47:174–192. doi: 10.1007/s12016-014-8422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.TEDDY Study Group. The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1150:1–13. doi: 10.1196/annals.1447.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee H-S, Burkhardt BR, McLeod W, et al. Biomarker discovery study design for type 1 diabetes in The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2014;30:424–434. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.He Q, Karlberg J. BMI in childhood and its association with height gain, timing of puberty, and final height. Pediatr Res. 2001;49:244–251. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200102000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moran A, Jacobs DR, Steinberger J, et al. Insulin resistance during puberty: results from clamp studies in 357 children. Diabetes. 1999;48:2039–2044. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.10.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tuomilehto J. The emerging global epidemic of type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13:795–804. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0433-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Beck RW, Tamborlane WV, Bergenstal RM, Miller KM, DuBose SN, Hall CA. The T1D exchange clinic registry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:4383–4389. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Scrivo R, Casadei L, Valerio M, Priori R, Valesini G, Manetti C. Metabolomics approach in allergic and rheumatic diseases. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11882-014-0445-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]