Abstract

Cytotoxic therapies prime adaptive immune responses to cancer by stimulating the release of tumor-associated antigens. However, the tumor microenvironment into which these antigens are released is typically immunosuppressed, blunting the ability to initiate immune responses. Recently, activation of the DNA sensor molecule STING by cyclic dinucleotides was shown to stimulate infection-related inflammatory pathways in tumors. In this study, we report that the inflammatory pathways activated by STING ligands generate a powerful adjuvant activity for enhancing adaptive immune responses to tumor antigens released by radiation therapy. In a murine model of pancreatic cancer, we showed that combining CT-guided radiation therapy with a novel ligand of murine and human STING could synergize to control local and distant tumors. Mechanistic investigations revealed T cell-independent and TNFα-dependent hemorrhagic necrosis at early times followed by later CD8 T cell-dependent control of residual disease. Clinically, STING was found to be expressed extensively in human pancreatic tumor and stromal cells. Our findings suggest that this novel STING ligand could offer a potent adjuvant for leveraging radiotherapeutic management of pancreatic cancer.

Introduction

Radiation therapy (RT) is a potential means to kill cancer cells to release tumor antigens and endogenous immune adjuvants for immune priming (1, 2), and also to identify the tumor by initiating local inflammation to direct trafficking and function of effector T cells at the treatment site (3–5). In murine models, RT depends in part on T cells for tumor control (6–9). RT synergizes well with T cell targeted immunotherapies in murine models (8, 10–14), in early clinical studies (15) and anecdotal reports (16–18). However, the tissue damage caused by RT also initiates a well-characterized wound repair response at the treatment site (19). This wound repair process is driven by intratumoral macrophages that limit inflammation and immune-mediated tissue destruction (20–22). Thus, depletion of tumor macrophages (23, 24) or preventing macrophage polarization to wound-healing phenotypes (25) significantly enhances the efficacy of radiation therapy.

We are investigating therapeutic interventions that prevent the post-radiation transition to an immune suppressive environment and therefore have the potential to enhance immune-mediated tumor control following radiation therapy. Infectious agents are known to prevent wound healing (26) and both infectious agents and immunological adjuvants have shown synergy with radiation therapy (27–30). STING (STimulator of INterferon Genes) is a cytosolic sensor of microbial infection (reviewed in (31)). Importantly, hyperactivity of STING to host DNA can result in autoimmunity (32) and activating mutations in STING can result in immunopathology (33). Recent data demonstrates that host STING expression is critical for spontaneous rejection of immunogenic or partially allogeneic tumors via effects on tumor macrophages (34) and radiation-mediated cure of immunogenic tumors is dependent on host STING (35). We hypothesized that ligands that activate STING will initiate inflammatory mechanisms within the tumor environment to improve the efficacy of radiation therapy in unresponsive tumors.

To test our hypothesis, we utilized synthetic CDN derivatives that were designed to have increased activity compared to natural STING ligands produced by bacteria or by host cell cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate synthase (cGAS). Since CDNs are susceptible to degradation by phosphodiesterases, dithio analogs in which the non-bridging oxygen atoms in the internucleotide phosphate bridge were replaced with sulfur atoms during synthesis. Since the phosphate bridge constitutes a chiral center, we tested purified dithio diastereomers and found that the RP,RP molecule had increased immunostimulatory properties in vitro, and conferred increased therapeutic anti-tumor efficacy in vivo, as compared to the RP,SP dithio analog or the parent CDN compound (Fu et. al., manuscript submitted). When the RP,RP dithio modification was combined with compounds that contained the same 2’-5’, 3’-5’ non-canonical (or mixed) linkage phosphate bridge as 2’-3’ cGAMP, we found that these RP,RS dithio 2’-3’ CDN molecules activated all five human STING alleles (36) expressed in cell lines, activated human PBMCs including from donors homozygous for the refractory allele, and had potent therapeutic efficacy in tumor-bearing mice (37).

We hypothesize that the potent inflammatory response elicited by STING ligation will prevent initiation of the wound-healing process and will enhance adaptive immune responses to antigens released by radiation therapy. To test this hypothesis, we use a murine pancreatic cancer model that is poorly responsive to radiation therapy and following treatment generates a myeloid response that suppresses adaptive immunity (7, 25, 38). CT-guided radiation was used to target tumors with minimal dose to normal tissues, and combined with local injection of a novel human and murine STING agonist. We demonstrate that radiation therapy and STING ligation synergize to generate systemic T cell responses that control distant disease. We demonstrate that early tumor control by STING ligation is T cell independent but occurs due to TNFα-mediated hemorrhagic necrosis, while late control of recurrence is CD8 T cell dependent. These data demonstrate that application of this novel STING ligand can convert radiation-mediated cell death into an endogenous vaccine to enhance adaptive immune-mediated local and distant tumor control.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Cell Lines

The Panc02 murine pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line (39) was kindly provided in 2009 by Dr. Woo (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, NY). The 3LL lung adenocarcinoma cell line (40) was obtained in 2009 from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). The SCCVII squamous cell carcinoma cell line was kindly provided in 2014 by Dr. Lee (Duke University Medical Center, NC). Species identity checks on these murine cell lines were performed murine-specific MHC antibodies, and were tested for contamination within the past 6 months using a Mycoplasma Detection Kit (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, Alabama). 6–8 week old C57BL/6 (Panc02, 3LL), C3H (SCCVII) or FVB (MMTV-PyMT) mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) for use in these experiments. STING−/− (Goldenticket Stock# 017537) and Rag1−/− (Stock# 002216) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Transgenic MMTV-PyMT mice (41) were kindly provided by Dr. Akporiaye (Sidra Medical and Research Center, Doha, Qatar). Mice expressing Cre under the PDX promoter (Stock #014647) and floxed Kras(G12D) (Stock# 008179) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and mice with floxed Trp53(R172H) (Stock# 01XM2) were obtained from the NCI Fredrick Mouse Repository. Mice were cross-bred to generate Pdx-Cre+/− Kras(G12D)+/− Trp53(R172H)+/− mice that spontaneously generate pancreatic tumors (42). Survival experiments were performed with 6–8 mice per experimental group, and mechanistic experiments with 4–6 mice per group. Animal protocols were approved by the Earle A. Chiles Research Institute IACUC (Animal Welfare Assurance No. A3913-01).

Antibodies and Reagents

Depleting anti-CD8 antibody (YTS 169.4 – BioXCell, West Lebanon, NH) was given i.p. 250µg one day before treatment and again 1 week later. Blocking anti-TNFα antibody (XT3.11 – BioXCell) was given i.p. 500µg 6hrs before treatment and again 48hrs later. Fluorescently-conjugated antibodies CD11b-AF700, Gr1-PE-Cy7, IA (MHC class II)-APC-Cy7, CD4-FITC (HlS51), CD8-PerCP-Cy5.5(53.6.7), IFNγ-APC(XMG1.2) were purchased from Ebioscience (San Diego, CA). Western blotting antibodies used include Arginase I (BD biosciences, San Jose, CA), iNOS (Cayman Chemical Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI), GAPdH, anti-mouse-HRP, and anti-rabbit-HRP (all Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Immunohistology antibody to F4/80 was purchased from AdB Serotec (Raleigh NC); CD3, CD31 from Spring Bio (Pleasanton, CA); Cy3 conjugated Smooth Muscle Actin from Sigma (St. Louis MO); CD45 (30-F11) from Ebioscience; and unconjugated anti-STING from Cell Signaling.

Preparation of synthetic STING ligands

Modified CDN derivative molecules were synthesized according to modifications of the “one-pot” Gaffney procedure, described previously (37, 43). Synthesis of CDN molecules utilized phosphoramidite linear coupling and H-phosphonate cyclization reactions. Synthesis of dithio CDNs was accomplished by sulfurization reactions to replace the non-bridging oxygen atoms in the internucleotide phosphate bridge with sulfur atoms. The phosphorus III intermediates generated upon formation of the linear dimer (phosphite triester stage) and cyclic dincucleotide (H-phosphonate diester stage) were sulfurized by treatment with 3-((N,N-dimethylaminomethylidene)amino)-3H-1,2,4-dithiazole-5-thione (DDTT) and 3-H-1,2-benzodithiol-3-one, respectively. The crude reaction mixture obtained after the second sulfurization was chromatographed on silica gel to generate a mixture of the RR- and RS-diastereomers of fully protected ML S2 CDA. Benzoyl and cyanoethyl deprotection using methanol and concentrated aqueous ammonia generated bis-TBS-ML-S2 CDA as a mixture of RR- and RS-diastereomers which were separated by C-18 prep HPLC. The purified bis-TBS-ML RR-S2 CDA was deprotected with TEA-3HF, neutralized with 1 M triethylammonium bicarbonate and desalted on a C18 SepPak to give ML RR-S2 CDA as the bis-triethylammonium salt in >95% purity. CDN molecules were characterized by high resolution Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectroscopy (FT-ICR) to confirm the expected elemental formula, both 1H NMR and 31P NMR, and by 1H-1H COSY (correlation NMR spectroscopy) in combination with a 1H-31P HMBC (heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation spectroscopy) to confirm the regiochemistry of the phosphodiester linkages. Prior to use in experiments, all synthetic CDN preparations were verified by LAL assay to be endotoxin free (<1 EU/mg).

Radiation Therapy of Tumors

Tumors were inoculated in the right flank at a dose of 2×105 Panc02, 5×105 3LL, and 5×105 SCCVII. MMTV-PyMT tumors were established in naïve FVB mammary glands using the published method (44). Briefly, tumors were harvested from day 100 MMTV-PyMT+ mice and dissected into approximately 2mm fragments followed by agitation in 1mg/mL collagenase in PBS for 1hr at room temperature. The digest was filtered through 100µm nylon mesh to remove macroscopic debris and 1×106 cells were injected into the mammary fat pat in a 1:1 mix with Matrigel (BD Biosciences). 10–14 days post tumor challenge, mice were randomized to receive treatment with CT-guided radiation therapy using a Small Animal Radiation Research Platform (SARRP, XStrahl, Gulmay Medical, Suwanee, GA) to deliver 10Gy to an isocenter in the tumor, with beam angles designed to minimize dose to normal tissues. Dosimetry was performed using SLICER software with SARRP-specific add-ons (XStrahl). Mice were additionally randomized to receive concurrent intratumoral injection of doses of RR-CDG in 25µl of PBS or PBS vehicle alone, with an additional intratumoral injection 24 hours later.

Tumor-associated antigen specific responses

Control mice and mice bearing Panc02 expressing the model antigen SIY (Panc02-SIY, kindly provided by Dr R. Weishelbaum, U Chicago) were randomized to receive treatment as described above. Spleens were harvested 7 days following treatment and cell suspensions were stimulated with 2 µM of (SIYRYYGL) or DMSO vehicle in the presence of brefeldin A for 5 hours at 37°C. Stimulated cells were washed and stained with CD4-FITC and CD8-PerCP Cy5.5, then fixed and permeabilized using a BD Cytofix/Cytoperm plus kit (BD Biosciences) and frozen at −80°C. For analysis cells were thawed and intracellularly stained with IFNγ-APC. Cells were washed and analyzed on a BD LSRII Flow Cytometer and the data was interrogated using BD FACSDiva (BD Biosciences) and FloJo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistology murine tumors were fixed in Z7 zinc based fixative (35) overnight. Tissue was then processed for paraffin tissue sections. 5µm sections were cut and mounted for analysis. Tissue sections were boiled in EDTA buffer as appropriate for antigen retrieval. Primary antibody binding was visualized with AlexaFluor 488, AlexaFluor 568, or AlexaFluor 647 conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and mounted with DAPI (Invitrogen) to stain nuclear material. Routinely processed paraffin embedded tumor tissue and adjacent normal tissue from surgical specimens of patients with confirmed pathologic diagnosis of adenocarcinoma were used to prepare 5µm sections of sections for staining. Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated then deprotected before staining for STING. Antibody binding was detected using HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and DAB as the enzyme substrate; slides were be counterstained with haematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted for analysis. Images were acquired using a Zeiss Axio observer Z1 with attached Nuance Multispectral Image camera and software (Perkin Elmer) or a Leica SCN400 whole slide scanner. All images displayed in the manuscript are representative of the entire tumor and their respective experimental cohort.

Cytokine Bead Assay

Detection of cytokines from murine peripheral blood serum, tumor homogenates, and flow sorted tumor associated macrophages was performed using a murine multiplex bead assay as previously described (45). To prepare tumor homogenates, tumors were harvested on ice and homogenized in 4.5µl PBS containing HALT protease inhibitor per mg tissue. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 14000g for 15 minutes at 4°C, and supernatants were stored in aliquots at −80°C until used. Cytokine levels in the supernatants were detected using a murine multiplex bead assay (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and read on a Luminex 100 array reader. Cytokine concentrations for replicates of each tumor sample were calculated according to a standard curve.

Flow sorting of tumor macrophages

The tumor was dissected into approximately 2mm fragments followed by agitation in 1mg/mL collagenase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 100µg/mL hyaluronidase (Sigma, St Louis, MO), and 20mg/mL DNase (Sigma) in PBS for 1hr at room temperature. The digest was filtered through 100µm nylon mesh to remove macroscopic debris and cell suspensions were washed and stained with antibodies. FACS sorting of tumor macrophages was performed as previously described (25, 46) using a BD FACSAria Cell Sorter to greater than 98% purity.

Preparation of Bone Marrow macrophages

Bone marrow cells isolated from long-bones of mice were cultured for a total of 7 days in complete media containing 40ng/ml MCSF (Ebioscience), with additional growth media provided after 3 days of culture. Adherent cells were harvested and macrophage differentiation confirmed by flow cytometry for CD11b, F4/80, Gr1 and IA. Macrophages were differentiated into M1 or M2 phenotypes by culture for 24 hours in the presence of IFNγ (10ng/ml Ebioscience) + 1µg/ml Ultrapure LPS (Invivogen, San Diego, CA) or IL-4 (10ng/ml, Ebioscience), respectively as previously described (38), in the presence or absence of 1µg/ml or 25µg/ml RR-CDG.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer and denatured in SDS loading buffer containing β2-mercaptoethanol, electrophoresed on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose. Blocked blots were probed overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Binding was detected using a Pierce SuperSignal Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) and exposure to film.

Statistics

Data were analyzed and graphed using Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Individual data sets were compared using Student’s T-test and analysis across multiple groups was performed using ANOVA with individual groups assessed using Tukey’s comparison. A synergy evaluation for the endpoint of tumor size change between days 14 and days 28 was performed using multivariable linear regression modeling, with RT treatment, CDG treatment, as well as their interaction term in the model. This analysis was performed using R 3.1.0 statistical program (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

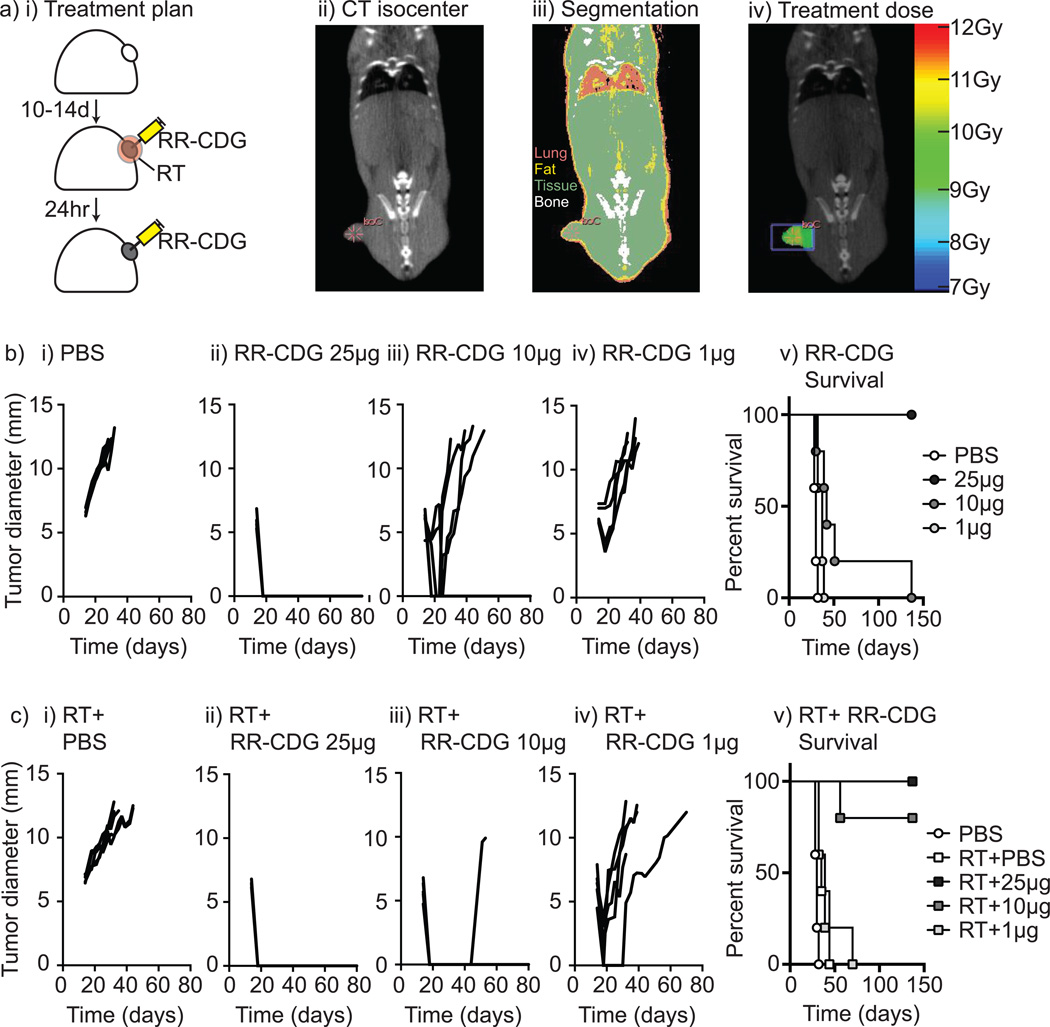

Dose dependent synergy between RR-CDG and radiation therapy

We have previously demonstrated that the tumor environment that emerges following radiation therapy suppresses adaptive immunity by activating a pathway of tissue repair and is driven by tumor macrophages (25, 38). We hypothesize that the potent inflammatory pathway activated by STING ligation will generate a strong adjuvant activity to enhance adaptive immune responses to antigens released by radiation therapy. To test the hypothesis, we evaluated synthetic CDN derivatives modified to be resistant to degradation by phosphodiesterases and to activate all known murine and human STING allele variants in a preclinical murine model of pancreatic cancer radiation therapy. We established Panc02 tumors in immune competent C57BL/6 mice and mice were randomized to receive radiation to the tumor, along with intratumoral injection of RP, Rp ditho c-di-GMP (RR-CDG) or vehicle to that same tumor immediately following radiation and again at 24 hours (Figure 1ai). Radiation was delivered using CT-guidance via the SARRP and dosed to deliver a suboptimal dose of 10Gy to the tumor with minimal dose to surrounding normal tissues (Figure 1aii–iv). RR-CDG was injected into the tumor at doses of 25, 10 or 1µg in PBS, or PBS vehicle alone and mice were followed for tumor growth and survival. RR-CDG caused a rapid, dose dependent control of the tumor (d4 following therapy PBS vs 25µg RR-CDG p<0.001; vs 10µg RR-CDG p<0.001; vs 1µg RR-CDG p<0.01), though at lower doses the tumor recurred (Figure 1b). 10Gy of radiation therapy alone did not significantly change tumor growth and minimally extended survival (median survival 30d vs. 35d, p<0.01), but significantly increased survival with 10µg of RR-CDG (median survival 42d vs. undefined, p<0.01) and was lost at 1µg RR-CDG (median survival 37d vs. 39d) (Figure 1c). Similar responses were seen in mice bearing 3LL tumors treated with 25, 10 or 1µg RR-CDG or PBS along with 10Gy radiation therapy (Supplementary Figure 1). To determine whether these effects at the 10µg dose were synergistic, we tested for super-additivity using the endpoint of tumor size change and found that the coefficient for RT:CDG was −4.11, in the same direction with the coefficients for both RT and CDG, and a p=0.043 indicating a super-additive effect of the combined therapy.

Figure 1. RR-CDG synergizes with radiation therapy for durable tumor cures.

Panc02 pancreatic adenocarcinoma tumors were established in immune competent C57BL/6 mice and a) randomized to remain untreated or to receive radiation therapy (RT) immediately followed by control (PBS) injections or 25, 10 or 1µg of RR-CDG into the tumor in matched volumes of PBS. ii) Tumor isocenters were identified by CT guidance. iii) CT images were used to determine tissue densities for iv) dosimetry using the SARRP to deliver 10Gy to isocenter with angled beams to minimize dose to radiosensitive organs. b) i–iv) growth of individual tumors in mice not treated with radiation therapy and v) overall survival. c) i–iv) growth of individual tumors in mice treated with radiation therapy and v) overall survival. Experiments incorporate 6–8 mice per group and the displayed experiment is representative of 3 independent repeats.

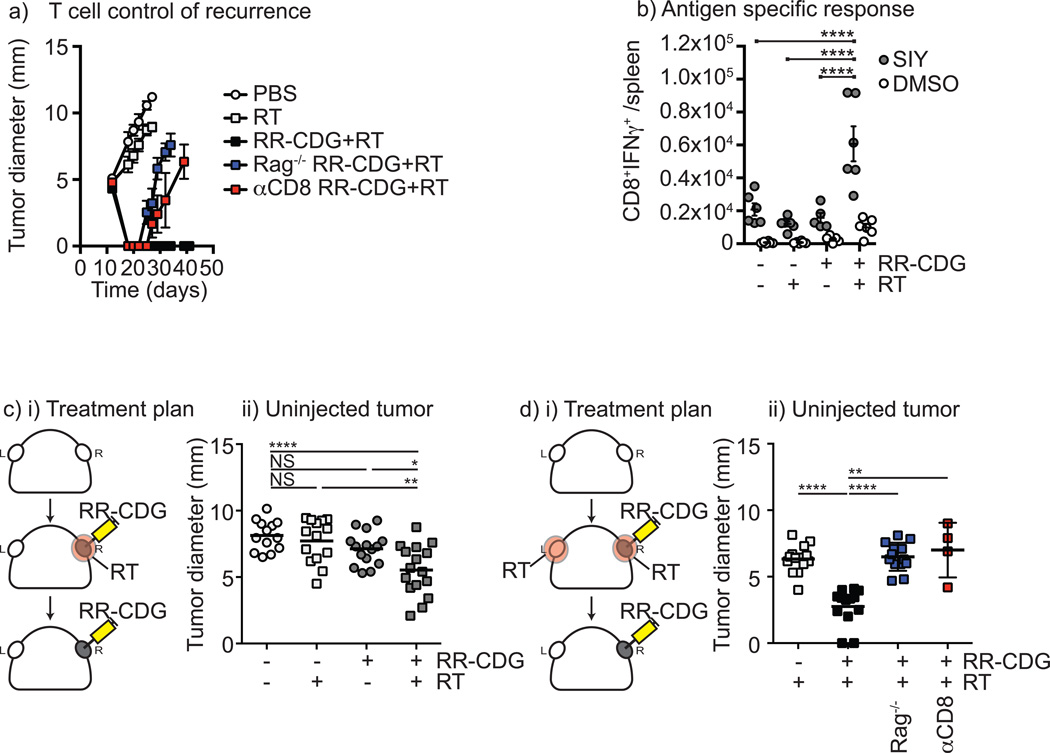

Adaptive immune control of distant tumors by RR-CDG plus radiation therapy

To determine whether this effect was a result of adaptive immune control of the tumor, the treatment was repeated in wild-type C57BL/6 mice as well as Rag1−/− mice that lack adaptive immunity. While combined therapy caused durable cure of tumors in wild-type mice, Rag1−/− mice showed an initial tumor control but all recurred (Figure 2a and Supplementary Figure 2). To identify the cell type required, wild-type mice were depleted of CD8 T cells and similarly demonstrated initial control followed by recurrence. These data demonstrate that the durable cure of tumors by RR-CDG is composed of both an initial T cell independent regression and long term-control dependent on CD8 T cells (Figure 2a and Supplementary Figure 2). To determine whether this therapy generated antigen specific T cells, we repeated treatment in mice bearing Panc02 tumors expressing the model antigen SIY, and measured SIY peptide-specific T cells in the spleen 7 days following treatment. We demonstrate that only in mice receiving combination therapy were we able to detect significant increases in antigen specific cells in the spleen (Figure 2b), suggesting this approach generates systemic T cell immunity. To determine whether this would permit control of distant disease, we established a model where unmodified Panc02 tumors were established on opposite flanks, and only one tumor was treated with radiation therapy and RR-CDG (Figure 2ci). Only in mice where the tumor was treated with both therapies resulted in control of the distant tumor, though while there was a significant decrease in tumor size in these mice, not all mice in the treatment groups demonstrated benefit (Figure 2cii). Radiation therapy has been shown to attract antigen-specific T cells to the treatment site and can improve immune killing at the treatment site (3–5). To determine whether additional radiation of the uninjected tumor could enhance the effect, we repeated the experimental model with RR-CDG injection to only one tumor, but irradiated both tumors (Figure 2di). In this setting, RR-CDG treatment resulted in a more dramatic control of the opposite flank tumor, and this did not occur in Rag−/− mice or where CD8 T cells were depleted (Figure 2dii), demonstrating that the effect is immune mediated. These data demonstrate that radiation combined with RR-CDG generates systemic immune responses to tumor-associated antigens that can control distant disease. Panc02 tumors are spontaneously metastatic to the lung, and radiation therapy of the primary tumor alone does not affect metastatic tumor growth (Supplementary Figure 3) as we have previously demonstrated with the 4T1 tumor model (45). Importantly, mice cleared of a single primary tumor by radiation plus RR-CDG did not develop metastatic disease over greater than 100 days of follow-up as determined by gross inspection and histological analysis. These data demonstrate that radiation plus RR-CDG generates a functional systemic immunity to treated tumors in vivo that eliminates residual microscopic disease.

Figure 2. Radiation plus RR-CDG generates a T cell response capable of controlling distant tumors.

C57BL/6 or Rag1−/− mice challenged with Panc02 were left untreated or treated with 10Gy focal radiation (RT) to the tumor followed immediately by intratumoral injection of 25µg RR-CDG or PBS with a repeat injection the following day. Comparison groups of C57BL/6 mice were treated with anti-CD8 depleting antibodies 1 day prior to RT and again 1 week later. a) Graphs show average tumor diameter. b) Panc02-SIY tumors were established and treated as in a) 7 days following treatment spleens were harvested and tested for SIY-peptide specific IFNγ production by intracellular cytokine staining. Graphs show the number of antigen-specific (SIY) or control (DMSO) CD8+IFNg+ cells per spleen. Each symbol represents one animal. c) i) Duplicate Panc02 tumors were established on each flank of C57BL/6 mice and only one tumor was treated as in a). ii) Graph shows tumor diameter of the untreated tumor 10 days following treatment. d) i) Duplicate Panc02 tumors were established on each flank of C57BL/6 or Rag1−/− mice and both tumors were treated with 10Gy RT, but only one tumor was treated with RR-CDG as in a). Additional groups were treated with anti-CD8 depleting antibodies 1 day prior to RT and again 1 week later. ii) Graph shows the tumor diameter of the uninjected tumor 10 days following treatment. Each symbol represents one mouse. Statistics calculated by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test: * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.005; **** p<0.001. The displayed experiment is representative of 2 independent repeats.

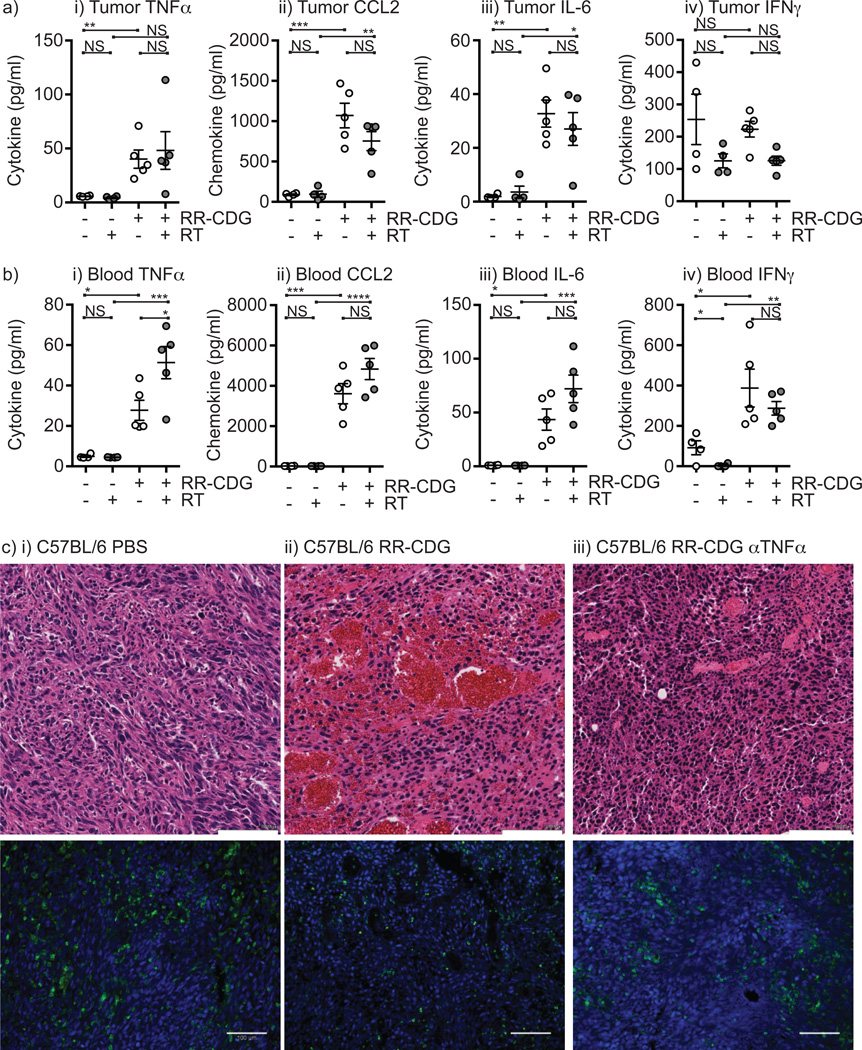

RR-CDG causes an early innate control by inducing stromal TNFα secretion

Since the initial tumor control by RR-CDG is not dependent on T cells, we investigated the mechanism of RR-CDG response in this early phase. Tumors harvested 6 hours following RR-CDG injection showed an extensive bloody infiltrate (Figure 3a), and histological evidence of early hemorrhagic necrosis (Figure 3b). Agents such as the flavanoid DMXAA—also known as a vascular disrupting agent—which activates mouse but not human STING have been shown to have potent vascular effects (47), so we investigated whether this hemorrhagic necrosis was a result of endothelial cell death. Immunohistology for CD31 and smooth muscle actin demonstrated vascular cells remained in the tumor. However, these CD31+ cells lacked Smooth Muscle Actin+ (SMA+) podocyte coverage and were greatly enlarged (Figure 3c). Immunostaining for F4/80 showed some clustering of macrophages around the enlarged immature vasculature (Figure 3d), and there was no significant accumulation of CD3+ T cells in the tumor at this early stage. RR-CDG administration did not cause hemorrhagic necrosis when injected into tumor-free subcutaneous sites (not shown), and did not cause hemorrhagic necrosis when injected into the liver (not shown), which has extensive fenestrated vasculature, suggesting that the neoangiogenic vasculature of the tumor is particularly susceptible to RR-CDG treatment. To confirm this data in a more authentic model of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in mice, Pdx-Cre+/− Kras(G12D)+/− Trp53(R172H)+/− mice that spontaneously generate pancreatic tumors (42) were treated with RR-CDG administered to established pancreatic masses via laparotomy. Control tumors show invasive pancreatic adenocarcinoma impinging on residual normal regions of the pancreas (Figure 3di). 24 hours following RR-CDG administration, tumors show extensive hemorrhagic necrosis through the tumor stroma (Figure 3dii). Interestingly, this hemorrhagic necrosis did not extend to adjacent normal regions of the pancreas (Figure 3diii). The rapid induction of hemorrhagic necrosis was also demonstrated in the SCCVII head and neck cancer model on the C3H background, the spontaneous MMTV-PyMT mammary carcinoma model on the FVB background, and in the 3LL lung adenocarcinoma model on the C57BL/6 background (Supplementary Figure 4). Though each model exhibited a different degree of hemorrhagic necrosis, each tumor showed a rapid decrease in size following treatment with RR-CDG and radiation therapy (Supplementary Figure 4).

Figure 3. RR-CDG causes rapid vascular and macrophage reorganization in the tumor.

a) Established Panc02 tumors in C57BL/6 mice were treated with intratumoral injection of i) PBS vehicle or ii) 25µg RR-CDG and harvested 6 hours later. At harvest 3 RR-CDG-treated tumors show macroscopic evidence of blood infiltrate. b) Histology of i) control and ii) RR-CDG-treated tumors at 6 hours. c) Immunofluorescence microscopy of i+iii) control and ii+iv) RR-CDG-treated tumors at 6 hours with staining for smooth muscle actin - red; CD3 - magenta; a DAPI nuclear stain - blue and either i–ii) CD31 - green or iii–iv) F4/80 - green. Experiments are representative of 2 independent replicates that include 4 or more mice per group. d) Pdx-Cre+/− Kras(G12D)+/− Trp53(R172H)+/− mice were treated with i) PBS or ii–iii) RR-CDG administered to established pancreatic masses via laparotomy. Images show representative sections of i–ii) tumor or iii) adjacent normal pancreas.

This early effect of RR-CDG resembles classic studies using TNFα injection into tumors (48). Analysis of cytokine and chemokine expression in tumors showed significant increases in TNFα, the monocyte chemoattractant CCL2, and IL-6 at 6 hours following radiation therapy and RR-CDG treatment (Figure 4a). This was accompanied by significant increases in these agents in the peripheral blood (Figure 4b). Interestingly, IFNγ was significantly elevated in the peripheral blood by RR-CDG treatment but not in the tumor, suggesting that IFNγ secretion was stimulated outside the tumor environment. To determine whether RR-CDG mediated induction of TNFα was responsible for the early hemorrhagic necrosis in treated tumors mice were treated with anti-TNFα blocking antibody 6 hours prior to RR-CDG injection and tumors harvested 24 hours following RR-CDG injection. As expected, RR-CDG treatment caused hemorrhagic necrosis in the treated tumor, and this was largely blocked by injection of anti-TNFα blocking antibody (Figure 4c). Staining for CD45+ cells in these tumors demonstrated persistent immune cell infiltrate even in the presence of anti-TNFα blocking antibody (Figure 4c).

Figure 4. RR-CDG treatment results in cytokine secretion that causes early tumor regression.

C57BL/6 mice challenged with Panc02 were left untreated or treated with 10Gy focal radiation (RT) to the tumor followed immediately by intratumoral injection of 25µg RR-CDG or PBS with a repeat injection the following day. Cytokine and chemokine levels were determined in the a) tumor or b) peripheral blood 6 hours following treatment by multiplex bead assay. Each symbol represents one mouse. Graphs additionally show mean plus SEM. c) C57BL/6 mice bearing established Panc02 tumors were treated with intratumoral injection of i) PBS, ii) 25µg RR-CDG or iii) 500µg anti-TNFα blocking antibody 6 hours prior to treatment with 25µg RR-CDG. Tumors were harvested 24 hours later for H&E staining in upper images or immunostained for CD45 (green) alongside DAPI (blue) in lower images. Scale bar (white) shows 100µM. Statistics calculated by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test: * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.005; **** p<0.001. Experiments incorporate 6–8 mice per group and the displayed experiment is representative of 2 independent repeats.

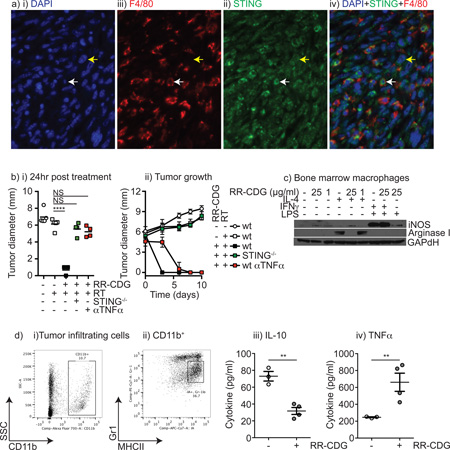

RR-CDG act through tumor stroma and repolarizes M2 tumor macrophages

To determine the cell type responsible for RR-CDG responses, tumors were stained for STING expression. Interestingly, both the cancer cells and the tumor stroma, including F4/80+ tumor macrophages, expressed STING (Figure 5a). In vitro, both Panc02 cells and bone marrow macrophages respond to RR-CDG with upregulation of MHCI and PDL1 (data not shown). To determine the relative importance of STING expression in the cancer cells versus the tumor stroma, Panc02 tumors were established in wild-type C57BL/6 mice or STING−/− (goldenticket) mice and treated with radiation therapy and RR-CDG. Interestingly, in STING−/− mice RR-CDG was entirely unable to cause early tumor regression, indicating that it is the stromal rather than cancer expression of STING that mediates this effect (Figure 5bi). Anti-TNFα also blocked the early regression caused by RR-CDG, in agreement with its ability to block hemorrhagic necrosis (Figure 4c). Despite blocking early regression, tumors treated with anti-TNFα gradually regressed, while tumors in STING−/− mice did not (Figure 5bii), suggesting that even without early TNFα-mediated hemorrhagic necrosis, radiation therapy combined with ligation of STING in tumor stroma results in tumor control through other immune-mediated control mechanisms.

Figure 5. RR-CDG suppresses M2 differentiation and generates pro-inflammatory responses from tumor macrophages.

a) Immune histology in Panc02 tumors showing i) DAPI, ii) F4/80, iii) STING and iv) a combined image. White arrow indicates a F4/80+ macrophage, yellow arrow a cancer cell. b) Wild-type C57BL/6 or STING−/− mice bearing established Panc02 tumors were left untreated or treated with 10Gy focal radiation along with concurrent intratumoral injection of PBS or 25µg RR-CDG and the injection was repeated 24 hours later. A control group of wild-type mice were treated with 500µg anti-TNFα blocking antibody 6 hours prior to treatment with 25µg RR-CDG and again 48 hours later. i) Average tumor diameter 24 hours following treatment. ii) tumor growth over time following treatment. c) Bone marrow macrophages were left untreated, treated with IL-4 to direct M2 differentiation, or IFNγ and LPS to direct M1 differentiation in the presence or absence of RR-CDG at 1 or 25µg/ml. 24 hours later macrophage differentiation was determined by western blotting for iNOS and Arginase I with GAPdH as a loading control. d) Tumor macrophages were sorted from Panc02 tumors by i) first gating for CD11b+ and ii) subgating on the MHCII+Gr1int population. c) sorted tumor macrophages were left untreated or treated with 25µg/ml RR-CDG for 6 hours, and secretion of i) IL-10 or ii) TNFα was determined by bead assay. Statistics calculated by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test: * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.005; **** p<0.001. Experiments incorporate 4–8 mice per group and the displayed experiment is representative of 2 independent repeats.

We have previously demonstrated that macrophages accumulate in Panc02 tumors following radiation therapy and exhibit a suppressive M2 differentiation, characterized by expression of arginase I rather than iNOS and secretion of IL-10 and not TNFα following LPS stimulation (25). To determine whether RR-CDG could overcome this suppressive differentiation, we differentiated bone marrow-derived macrophages into a M2 phenotype by treatment with IL-4, or into an M1 phenotype by treatment with IFNγ plus LPS. Concurrent treatment with 25µg/ml RR-CDG blocked arginase I upregulation by IL-4, though was not able to cause significant iNOS expression when compared to the IFNγ plus LPS control (Figure 5c). The effect was lost when the RR-CDG dose was dropped to 1µg/ml. These data suggest that RR-CDG treatment can block M2 differentiation of macrophages, though does not cause classic M1 differentiation. To determine the effect of RR-CDG on actual tumor macrophages, we purified tumor macrophages from Panc02 tumors (Figure 5di–ii) and measured cytokine secretion following stimulation with RR-CDG. RR-CDG stimulation significantly decreased IL-10 secretion by tumor macrophages and significantly increased TNFα (Figure 5diii–iv) confirming that RR-CDG can overcome the suppressive differentiation of tumor macrophages, and that tumor macrophages are a potential candidate from the stromal response RR-CDG and a potential source of TNFα.

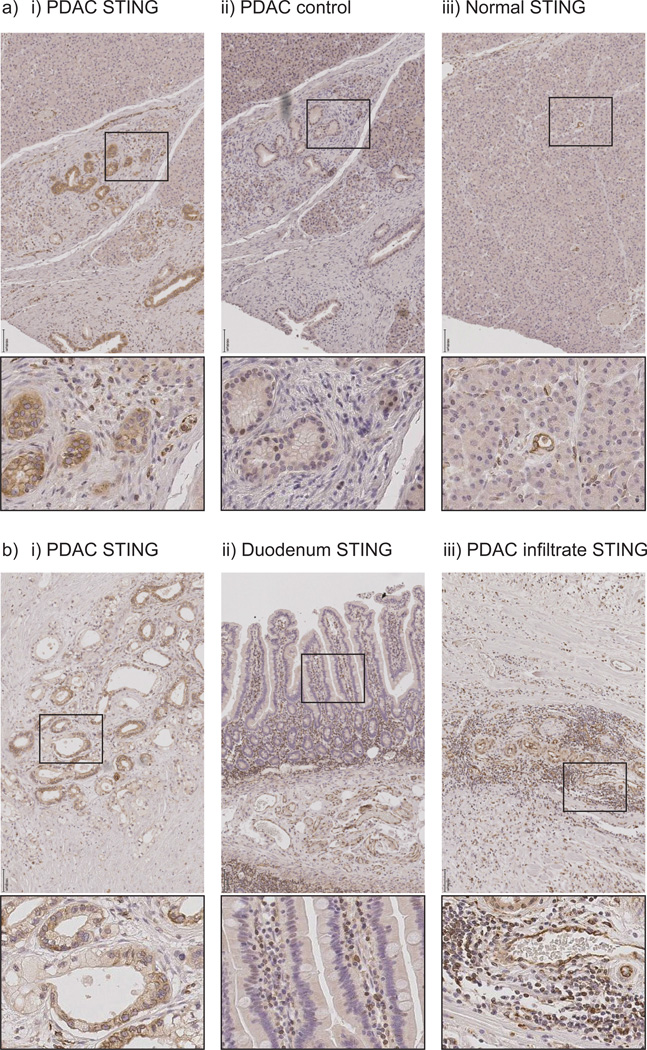

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma has STING expression in cancer cells and tumor stroma

The synthetic STING ligand RR-CDG is able to bind all isoforms of human STING (37). To determine whether pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma has STING expression in a similar pattern to our murine model, we performed immunohistology for STING in patient samples following pancreaticoduodenectomy. We identified strong specific STING staining in cancer cells in examples of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in patients that were treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation prior to pancreaticoduodenectomy (Figure 6ai–ii). In these patients, residual pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells as well as stromal cells express STING. Acinar cells in normal regions of the tumor-bearing pancreas do not express STING, though these normal regions still exhibit STING expression in stromal cells, and STING is detectable in both endothelial cells and ductal cells (Figure 6aiii). STING expression is also detectable in cancer cells in resection samples of untreated pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Figure 6bi). By contrast, normal duodenum epithelial cells neighboring the tumor resected during pancreaticoduodenectomy poorly express STING while underlying immune cells in the villi are strongly positive (Figure 6bii). Similarly, the lymphoid aggregates occasionally visible in the stroma of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma show strong STING expression in a large proportion of cells (Figure 6biii). These data demonstrate that human STING is present in stromal and cancer cells in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and remains following chemoradiation, suggesting that these engineered cyclic dinucleotides targeting both murine and human STING in conjunction with radiation therapy are a potential novel combination for immunotherapy of pancreatic cancer.

Figure 6. Expression of STING in pancreatic adenocarcinoma tumor and stroma.

a) T3 pancreatic adenocarcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by resection showing i–ii) residual cancer or iii) residual normal regions of the tumor-bearing pancreas stained for i+iii) STING or ii) control staining. b) Resected tissue samples from i) untreated T3 pancreatic adenocarcinoma stained with STING; ii) adjacent normal duodenum resected as part of pancreaticoduodenectomy; iii) lymphoid aggregates in resected pancreas. Black scale bar shows 100µM. Boxes show origin of expanded images.

Discussion

These data demonstrate that while radiation alone is poorly effective at generating systemic antigen specific immune responses, when combined with novel STING agonists, radiation therapy generates T cell immunity required for local control and control of distant disease. Treatment with the synthetic RR-CDG ligand of STING resulted in a two-phase control of tumors. Firstly, there was a T cell independent hemorrhagic necrosis driven by TNFα secretion, followed by a CD8 T cell dependent control of recurrence. With higher doses of RR-CDG, the initial innate response is sufficient to control the tumor, but at lower doses where local control is incomplete, the ability of radiation to boost endogenous T cell responses in the context of RR-CDG treatment results in T cell mediated control of both local and distant disease. RR-CDG treatment acts through cells in the tumor stroma, since its function is entirely dependent on STING expression by the host rather than the cancer cells, and we demonstrate that macrophages in the tumor are highly responsive to RR-CDG treatment.

Radiation therapy has a great deal of potential to deliver site-directed cytotoxicity with minimal damage to non-target tissues. The combined imaging technology, physics and computational dosimetry makes radiation therapy a rational intervention for therapy of individual lesions. Since radiation has rarely been able to affect tumors outside the treatment field, in patients with metastatic disease radiation has primarily been used as a palliative tool for individual problematic lesions. However, the recent combination of immunotherapy with radiation therapies has resulted in multiple reports of widespread metastatic tumor control in preclinical models and more recently in patients (15–18). While the role of radiation in pancreatic cancer treatment has evoked controversy over the past two decades, the increasing study of stereotactic body radiation therapy in the neoadjuvant and locally advanced setting as reviewed by Franke et al.(49), provides an opportunity to use radiation in patients with borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer both for its role in local control and as an immune modulator, alongside immunotherapy, to elicit systemic anti-tumor immune responses. As we gain a greater understanding of the immunological effects of radiation therapy, it is becoming clear that a complex interaction of multiple components are involved. Firstly, radiation, at sufficient doses, kills cancer cells. The appropriate delivery and dose for cancer cell killing has been well established over decades of careful radiobiological research, however the appropriate dose for priming immune effects is less clear. Fractionation of radiation over 5–7 weeks of daily treatment is a superior technique to ensure selective cancer versus normal cell death, though repeated treatment of the tumor likely causes repeated death of tumor infiltrating antigen specific T cells. Compacting radiation into fewer (1–5), higher doses of radiation made possible by advanced targeting techniques avoids continued treatments and is the approach used in almost all preclinical radiation models. However, we and others have shown that higher doses of radiation result in a wound-healing response involving tumor macrophages that likely suppresses adaptive immune responses at the treatment site (23–25). The second component brought by radiation therapy is a transient local improvement in the inflammatory environment of the tumor, resulting in cytokine and chemokine secretion and improved antigen presentation by cancer cells (3–5). Thus, when followed by adoptive transfer of strongly antigen-specific T cells, even low radiation doses can direct T cells to the tumor and improve local control where neither are effective alone (50). Together, these data suggest that where doses are high enough to kill cancer cells, radiation therapy can initiate new antigen specific immune responses if combined with immunotherapies sufficiently potent to overcome the poor context of antigen released by radiation. However, higher doses of radiation therapy are followed later by a wound-healing response that resolves adaptive immunity and limits immune control. The data reported here suggest that these novel ligands for STING can potently improve the inflammatory context of antigens released by higher doses of radiation therapy and allow extended T cell control of residual disease.

Our data demonstrates that the rapid TNFα-driven hemorrhagic necrosis driven by RR-CDG is not necessary for tumor control, since early TNFα blockade limits this necrosis yet still results in tumor regression. An alternative agonist of STING with reduced pyrogenic activity has been shown to have similar local control and improved ability to generate systemic T cell immunity as a single agent (37). Thus it is possible that the early TNFα-driven response limits T cell activity, potentially through an over-exuberant and possibly lymphotoxic cytokine response or a suboptimal kinetic of antigen release and immune stimulation. This would fit with published reports where systemic administration of STING ligands can activate tolerogenic responses (51), as has been reported with CpG (52). This may explain why our data indicates that while T cells play a role in local tumor control with RR-CDG as a single agent there appears to be a failure to generate systemic immunity. It is possible that varying timing with regards to radiation therapy has the potential to improve the systemic adaptive immune response initiated by STING ligands. Nevertheless, the ability of STING ligation to generate a pro-inflammatory response even from macrophages polarized to suppressive phenotypes distinguishes this pathway from conventional adjuvants targeting Toll-like receptors (TLR). TLR ligation of macrophages purified from Panc02 tumors causes secretion of immune suppressive IL-10 and not TNFα secretion in agreement with their M2 polarization (25), whereas we show here that STING ligation blocks IL-10 secretion and generates TNFα. A range of agents have been shown to redirect polarization of macrophages, for example systemic administration of anti-CD40 generated more M1-polarized macrophages that were subsequently recruited to the tumor to improve pancreatic cancer therapy (53), however few agents are able to generate M1-type responses from M2-type macrophages. The murine STING ligand DMXAA was recently shown to cause an early hemorrhagic necrosis in tumors that was dependent on macrophages and similarly repolarized macrophages from M2 to M1 phenotypes (47). In these experiments, it is interesting that tumors with higher macrophage infiltrates were more susceptible to DMXAA therapy (47) since commonly macrophages infiltrates causes resistance to T cell targeted immunotherapies such as anti-OX40, anti-CTLA4 and anti-PD1 (21, 54). These data suggest that therapies targeting STING may provide a novel treatment option for those patients most resistant to conventional immunotherapy.

Immunohistology shows that STING is well expressed in both the cancer cells and stroma of pancreatic tumors in patients, but is poorly expressed in normal regions of the pancreas. While expression of STING is required in stromal cells for tumor rejection by STING ligands, in vitro RR-CDG can cause upregulation of MHCI and PDL1 on STING-expressing cancer cells (data not shown) and non-hematopoetic cells can also self-sense DNA damage through STING (55). Thus, STING ligands have the potential to affect the cancer cells as well as the infiltrating cells as part of the desmoplastic reaction in pancreatic tumors. Nevertheless, since in our models RR-CDG function is entirely dependent on the expression of STING in stromal cells, the extensive stroma of pancreatic tumors remains an interesting independent target to accompany radiation-mediated death of cancer cells to generate a novel therapeutic combination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Gary L. Grunkemeier Ph.D, and Lian Wang, MS (Medical Data Research Center, and Regional Shared Services, Providence Health System, Portland OR.) for statistical support.

Financial Support.

This study was supported by America Cancer Society RSG-12-168-01-LIB, (M.J. Gough, B. Cottam, D. Friedman) and National Cancer Institute R01 CA182311-01A1 (M.J. Gough, J.R. Baird, B. Cottam, D. Friedman, M.R. Crittenden).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

Dr. Dubensky and Dr. Kanne are employees of Aduro Biotech, Inc., as listed in their author affiliations. Aduro Biotech did not finance or direct the study but did construct and provide the STING ligand as described. Dr. Crittenden has served as a consultant for or on the advisory board of Regeneron. No other conflicts are present.

References

- 1.Ludgate CM. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012. Optimizing Cancer treatments to induce an acute immune response; radiation abscopal effects, PAMPS and DAMPS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, Obeid M, Ortiz C, Criollo A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nature medicine. 2007;13(9):1050–1059. doi: 10.1038/nm1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reits EA, Hodge JW, Herberts CA, Groothuis TA, Chakraborty M, Wansley EK, et al. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203(5):1259–1271. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garnett CT, Palena C, Chakraborty M, Tsang KY, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Sublethal irradiation of human tumor cells modulates phenotype resulting in enhanced killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2004;64(21):7985–7994. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakraborty M, Abrams SI, Coleman CN, Camphausen K, Schlom J, Hodge JW. External beam radiation of tumors alters phenotype of tumor cells to render them susceptible to vaccine-mediated T-cell killing. Cancer research. 2004;64(12):4328–4337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee Y, Auh SL, Wang Y, Burnette B, Wang Y, Meng Y, et al. Therapeutic effects of ablative radiation on local tumor require CD8+ T cells: changing strategies for cancer treatment. Blood. 2009;114(3):589–595. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young KH, Newell P, Cottam B, Friedman D, Savage T, Baird J, et al. TGFbeta inhibition prior to hypofractionated radiation enhances efficacy in preclinical models. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014 doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gough MJ, Crittenden MR, Sarff M, Pang P, Seung SK, Vetto JT, et al. Adjuvant therapy with agonistic antibodies to CD134 (OX40) increases local control after surgical or radiation therapy of cancer in mice. J Immunother. 2010;33(8):798–809. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181ee7095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang H, Deng L, Chmura S, Burnette B, Liadis N, Darga T, et al. Radiation-induced equilibrium is a balance between tumor cell proliferation and T cell-mediated killing. Journal of immunology. 2013;190(11):5874–5881. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demaria S, Kawashima N, Yang AM, Devitt ML, Babb JS, Allison JP, et al. Immune-mediated inhibition of metastases after treatment with local radiation and CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model of breast cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11(2 Pt 1):728–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim JY, Brockstedt DG, Lord EM, Gerber SA. Radiation therapy combined with Listeria monocytogenes-based cancer vaccine synergize to enhance tumor control in the B16 melanoma model. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e29028. doi: 10.4161/onci.29028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng J, See AP, Phallen J, Jackson CM, Belcaid Z, Ruzevick J, et al. Anti-PD-1 Blockade and Stereotactic Radiation Produce Long-Term Survival in Mice With Intracranial Gliomas. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng L, Liang H, Burnette B, Beckett M, Darga T, Weichselbaum RR, et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124(2):687–695. doi: 10.1172/JCI67313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi W, Siemann DW. Augmented antitumor effects of radiation therapy by 4-1BB antibody (BMS-469492) treatment. Anticancer research. 2006;26(5A):3445–3453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seung SK, Curti BD, Crittenden M, Walker E, Coffey T, Siebert JC, et al. Phase 1 study of stereotactic body radiotherapy and interleukin-2--tumor and immunological responses. Science translational medicine. 2012;4(137):137ra74. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiniker SM, Chen DS, Reddy S, Chang DT, Jones JC, Mollick JA, et al. A Systemic Complete Response of Metastatic Melanoma to Local Radiation and Immunotherapy. Translational Oncology. 2012;5(6):404–407. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stamell EF, Wolchok JD, Gnjatic S, Lee NY, Brownell I. The Abscopal Effect Associated With a Systemic Anti-melanoma Immune Response. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Postow MA, Callahan MK, Barker CA, Yamada Y, Yuan J, Kitano S, et al. Immunologic correlates of the abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366(10):925–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tibbs MK. Wound healing following radiation therapy: a review. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 1997;42(2):99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(96)01880-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gough MJ, Young K, Crittenden M. The impact of the myeloid response to radiation therapy. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:281958. doi: 10.1155/2013/281958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gough MJ, Killeen N, Weinberg AD. Targeting macrophages in the tumour environment to enhance the efficacy of alphaOX40 therapy. Immunology. 2012;136(4):437–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez PC, Quiceno DG, Zabaleta J, Ortiz B, Zea AH, Piazuelo MB, et al. Arginase I production in the tumor microenvironment by mature myeloid cells inhibits T-cell receptor expression and antigen-specific T-cell responses. Cancer Res. 2004;64(16):5839–5849. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu J, Escamilla J, Mok S, David J, Priceman S, West B, et al. CSF1R Signaling Blockade Stanches Tumor-Infiltrating Myeloid Cells and Improves the Efficacy of Radiotherapy in Prostate Cancer. Cancer research. 2013;73(9):2782–2794. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahn GO, Tseng D, Liao CH, Dorie MJ, Czechowicz A, Brown JM. Inhibition of Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) enhances tumor response to radiation by reducing myeloid cell recruitment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(18):8363–8368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911378107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crittenden MR, Cottam B, Savage T, Nguyen C, Newell P, Gough MJ. Expression of NF-kappaB p50 in tumor stroma limits the control of tumors by radiation therapy. PloS one. 2012;7(6):e39295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bucknall TE. The effect of local infection upon wound healing: an experimental study. The British journal of surgery. 1980;67(12):851–855. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800671205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Touchefeu Y, Vassaux G, Harrington KJ. Oncolytic viruses in radiation oncology. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2011;99(3):262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrington KJ, Karapanagiotou EM, Roulstone V, Twigger KR, White CL, Vidal L, et al. Two-stage phase I dose-escalation study of intratumoral reovirus type 3 dearing and palliative radiotherapy in patients with advanced cancers. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2010;16(11):3067–3077. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milas L, Mason KA, Ariga H, Hunter N, Neal R, Valdecanas D, et al. CpG oligodeoxynucleotide enhances tumor response to radiation. Cancer Res. 2004;64(15):5074–5077. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason KA, Hunter NR. CpG plus radiotherapy: a review of preclinical works leading to clinical trial. Frontiers in oncology. 2012;2:101. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burdette DL, Vance RE. STING and the innate immune response to nucleic acids in the cytosol. Nature immunology. 2013;14(1):19–26. doi: 10.1038/ni.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gall A, Treuting P, Elkon KB, Loo YM, Gale M, Jr, Barber GN, et al. Autoimmunity initiates in nonhematopoietic cells and progresses via lymphocytes in an interferon-dependent autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2012;36(1):120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Jesus AA, Marrero B, Yang D, Ramsey SE, Montealegre Sanchez GA, et al. Activated STING in a vascular and pulmonary syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;371(6):507–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woo S-R, Fuertes Mercedes B, Corrales L, Spranger S, Furdyna Michael J, Leung Michael YK, et al. STING-Dependent Cytosolic DNA Sensing Mediates Innate Immune Recognition of Immunogenic Tumors. Immunity. 2014;41(5):830–842. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deng L, Liang H, Xu M, Yang X, Burnette B, Arina A, et al. STING-Dependent Cytosolic DNA Sensing Promotes Radiation-Induced Type I Interferon-Dependent Antitumor Immunity in Immunogenic Tumors. Immunity. 2014;41(5):843–852. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yi G, Brendel VP, Shu C, Li P, Palanathan S, Cheng Kao C. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of human STING can affect innate immune response to cyclic dinucleotides. PloS one. 2013;8(10):e77846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corrales L, Glickman LH, McWhirter SM, Kanne DB, Sivick KE, Katibah GE, et al. Direct Activation of STING in the Tumor Microenvironment Leads to Potent and Systemic Tumor Regression and Immunity. Cell Rep. 2015;11(7):1018–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crittenden MR, Savage T, Cottam B, Baird J, Rodriguez PC, Newell P, et al. Expression of arginase I in myeloid cells limits control of residual disease after radiation therapy of tumors in mice. Radiation research. 2014;182(2):182–190. doi: 10.1667/RR13493.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corbett TH, Roberts BJ, Leopold WR, Peckham JC, Wilkoff LJ, Griswold DP, Jr, et al. Induction and chemotherapeutic response of two transplantable ductal adenocarcinomas of the pancreas in C57BL/6 mice. Cancer Res. 1984;44(2):717–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bertram JS, Janik P. Establishment of a cloned line of Lewis Lung Carcinoma cells adapted to cell culture. Cancer letters. 1980;11(1):63–73. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(80)90130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guy CT, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Induction of mammary tumors by expression of polyomavirus middle T oncogene: a transgenic mouse model for metastatic disease. Molecular and cellular biology. 1992;12(3):954–961. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hingorani SR, Wang L, Multani AS, Combs C, Deramaudt TB, Hruban RH, et al. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer cell. 2005;7(5):469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gaffney BL, Veliath E, Zhao J, Jones RA. One-flask syntheses of c-di-GMP and the [Rp,Rp] and [Rp,Sp] thiophosphate analogues. Organic letters. 2010;12(14):3269–3271. doi: 10.1021/ol101236b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeNardo DG, Brennan DJ, Rexhepaj E, Ruffell B, Shiao SL, Madden SF, et al. Leukocyte Complexity Predicts Breast Cancer Survival and Functionally Regulates Response to Chemotherapy. Cancer discovery. 2011;1(1):54–67. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crittenden MR, Savage T, Cottam B, Bahjat KS, Redmond WL, Bambina S, et al. The peripheral myeloid expansion driven by murine cancer progression is reversed by radiation therapy of the tumor. PloS one. 2013;8(7):e69527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gough MJ, Ruby CE, Redmond WL, Dhungel B, Brown A, Weinberg AD. OX40 agonist therapy enhances CD8 infiltration and decreases immune suppression in the tumor. Cancer Res. 2008;68(13):5206–5215. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Downey CM, Aghaei M, Schwendener RA, Jirik FR. DMXAA causes tumor site-specific vascular disruption in murine non-small cell lung cancer, and like the endogenous non-canonical cyclic dinucleotide STING agonist, 2'3'-cGAMP, induces M2 macrophage repolarization. PloS one. 2014;9(6):e99988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pennica D, Nedwin GE, Hayflick JS, Seeburg PH, Derynck R, Palladino MA, et al. Human tumour necrosis factor: precursor structure, expression and homology to lymphotoxin. Nature. 1984;312(5996):724–729. doi: 10.1038/312724a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franke AJ, Rosati LM, Pawlik TM, Kumar R, Herman JM. The Role of Radiation Therapy in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma in the Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Settings. Semin Oncol. 2015;42(1):144–162. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klug F, Prakash H, Huber PE, Seibel T, Bender N, Halama N, et al. Low-dose irradiation programs macrophage differentiation to an iNOS(+)/M1 phenotype that orchestrates effective T cell immunotherapy. Cancer cell. 2013;24(5):589–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang L, Li L, Lemos H, Chandler PR, Pacholczyk G, Baban B, et al. Cutting edge: DNA sensing via the STING adaptor in myeloid dendritic cells induces potent tolerogenic responses. Journal of immunology. 2013;191(7):3509–3513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mellor AL, Baban B, Chandler PR, Manlapat A, Kahler DJ, Munn DH. Cutting Edge: CpG Oligonucleotides Induce Splenic CD19+ Dendritic Cells to Acquire Potent Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase-Dependent T Cell Regulatory Functions via IFN Type 1 Signaling. The Journal of Immunology. 2005;175(9):5601–5605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beatty GL, Chiorean EG, Fishman MP, Saboury B, Teitelbaum UR, Sun W, et al. CD40 agonists alter tumor stroma and show efficacy against pancreatic carcinoma in mice and humans. Science. 2011;331(6024):1612–1616. doi: 10.1126/science.1198443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu Y, Knolhoff BL, Meyer MA, Nywening TM, West BL, Luo J, et al. CSF1/CSF1R Blockade Reprograms Tumor-Infiltrating Macrophages and Improves Response to T-cell Checkpoint Immunotherapy in Pancreatic Cancer Models. Cancer Res. 2014 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahn J, Xia T, Konno H, Konno K, Ruiz P, Barber GN. Inflammation-driven carcinogenesis is mediated through STING. Nature communications. 2014;5:5166. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.