Abstract

Unkempt is an evolutionarily conserved RNA-binding protein that regulates translation of its target genes and is required for the establishment of the early bipolar neuronal morphology. Here we determined the X-ray crystal structure of mouse Unkempt and show that its six CCCH zinc fingers (ZnFs) form two compact clusters, ZnF–3 and ZnF4–6, that recognize distinct trinucleotide RNA substrates. Both ZnF clusters adopt a similar overall topology and use distinct recognition principles to target specific RNA sequences. Structure-guided point mutations reduce the RNA binding affinity of Unkempt both in vitro and in vivo, ablate Unkempt’s translational control and impair the ability of Unkempt to induce a bipolar cellular morphology. Our study unravels a new mode of RNA sequence recognition by clusters of CCCH ZnFs that is critical for post-transcriptional control of neuronal morphology.

The CCCH ZnF proteins make up the second most common group of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) in mammals1 but have not received as much attention as, for instance, the RBPs containing the RNA-recognition motif (RRM) or the K-homology (KH) domain2-4. Phenotypically, the roles of CCCH ZnF proteins range from specification of embryonic asymmetry in Caenorhabditis elegans5-7 to control of macrophage activation and muscle development in mammals8-11. A similar diversity is seen at the mechanistic level: CCCH ZnF proteins participate in numerous RNA-regulatory processes, including alternative splicing, RNA localization, transcript stability, polyadenylation, translation and small-RNA biogenesis12-16.

CCCH ZnF structures of only three proteins in complexes with their target RNAs have been determined to date, namely TIS11d17, MBNL1 (ref. 18) and the yeast Nab2 protein19,20. All three proteins regulate distinct biological processes and differ in their mechanisms of action. TIS11d is encoded by an ‘immediate early’ gene and controls the inflammatory response by binding to the class II AU-rich element in the 3′ untranslated region of target mRNAs and consequently promoting their deadenylation and degradation17,21. In contrast, MBNL1 contributes to muscle and eye development and is thought to function through regulation of alternative splicing and mRNA localization10,13,22. Finally, in budding yeast, Nab2 participates in the regulation of polyadenylation and nuclear export of mature mRNAs23-25. Despite their functional differences, however, the structures of these CCCH proteins all point to a specific recognition of two to four ribonucleotides per ZnF domain. Unexpectedly, these structures have also revealed that sequence-specific RNA recognition is frequently achieved through intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the functional groups (amide and carbonyl) of the protein backbone and the Watson-Crick edges of the bases. This is in contrast to the mechanisms of several other RBPs that recognize their cognate RNA motifs largely through interactions with amino acid side chains, thus resulting in a more permissive RNA recognition. Hence, the shape of a CCCH ZnF domain, which provides a rigid hydrogen-bonding template that ensures high sequence specificity, appears to be the primary determinant of RNA binding17,26.

A general characteristic of RBPs is their modular architecture, wherein a combination of multiple copies of RNA-binding domains allows for higher specificity, affinity and versatility of RNA binding than could be achieved with individual domains26. The majority of the CCCH ZnF proteins contain at least two CCCH ZnFs, and several ZnF proteins contain three ZnFs in tandem; some family members contain additional RNA-binding domains12. Furthermore, the individual CCCH ZnFs of a particular tandem CCCH protein display similar if not identical sequence specificities: each of the two ZnFs of TIS11d recognizes a UAUU repeat17, the tandem ZnFs of MBNL1 each target a separate GC(U) site18, and all CCCH ZnFs of Nab2 exhibit specificity for polyadenosine sequences19,27. Despite these common features, however, the apparent diversity of CCCH ZnF-RNA interactions in the available structures calls for additional studies to better elucidate the different modes of RNA recognition by this small RNA–binding domain.

The tandem CCCH ZnF protein Unkempt, first described as a developmental regulator in the fruit fly, binds to its target mRNAs in a sequence-specific manner and functions to reduce target-mRNA translation and control the early morphology of neurons28,29. Interestingly, the consensus Unkempt response element (URE) consists of two different motifs: a UAG trinucleotide and a more variable U-rich motif29. Given that Unkempt contains six evolutionarily conserved tandem CCCH ZnFs, it seems difficult to conceive of why such a large array would be needed to recognize a relatively short stretch of RNA sequence. To resolve the binding requirement as well as the strict functional need for the intact RNA-binding region of Unkempt, we determined the crystal structures of two subsets of mouse Unkempt zinc fingers, ZnF1–3 and ZnF4–6 (Fig. 1a), bound to a consensus URE.

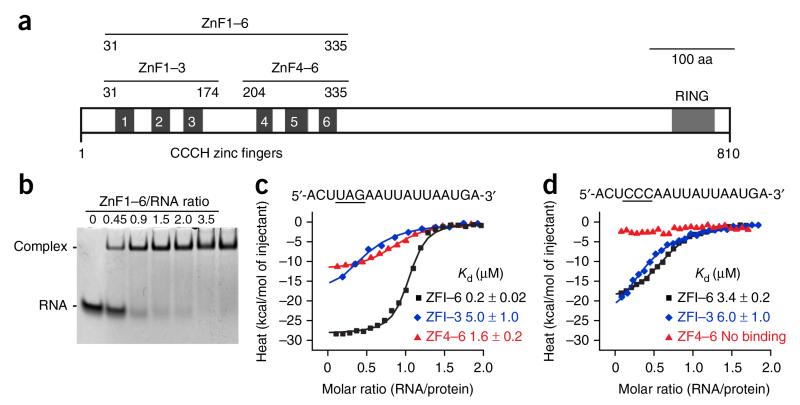

Figure 1.

Domain architecture of Unkempt and RNA affinity of its CCCH ZnFs. (a) Schematic of mouse Unkempt protein depicting all six predicted CCCH ZnFs and the RING domain. Also shown are domain boundaries of Unkempt constructs ZnF1–6, ZnF1–3 and ZnF4–6 used in this study. Aa, amino acids. (b) RNA EMSA demonstrating near-equimolar binding of recombinant ZnF1–6 to the 18-mer URE located in the HSPA8 mRNA29. The synthetic RNA was used at 40 μM. The uncropped image of the gel is shown in Supplementary Data Set 1. (c,d) ITC binding curves of complex formation between the indicated wild-type (c) or UAG-mutated (d) HSPA8 RNA and ZnF1–6, ZnF1–3 and ZnF4–6 of Unkempt. Solid lines represent nonlinear least-squares fit to the measured titration data, with binding enthalpy (kcal/mol), association constant and number of binding sites per monomer as variables. The calculated values for Kd (mean ± range of two independent technical replicates) are indicated.

RESULTS

CCCH ZnF subsets and their affinity for URE motifs

We found two putative structured regions within the ZnF domain of the mouse Unkempt protein—the N-terminal ZnF1–3 and the C-terminal ZnF4–6—which share 23% sequence identity and are separated by a less-ordered linker region (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). Using electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) techniques, we observed a roughly equimolar stoichiometry of binding between the zinc-finger region (ZnF1–6) and the URE located in the human HSPA8 mRNA (Fig. 1b). To examine whether the UAG motif is preferentially bound by either of the two sets of three ZnFs, we carried out isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and found that mutation of the UAG motif reduced the binding by ZnF4–6 but not by ZnF1–3 (Fig. 1c,d). The mutation also weakened the affinity of the entire ZnF domain for the mutant compared to the wild-type URE. These data suggest that ZnF4–6 recognizes the UAG motif and that ZnF1–3 might interact with other parts of the URE.

Recognition of the UAG motif by the ZnF4–6 cluster

According to the current understanding of the RNA recognition by the CCCH ZnF domain, a tandem array of six CCCH ZnFs would be expected to recognize between 12 and 24 ribonucleotides, far more than the number observed for Unkempt. To explain the puzzlingly high number of Unkempt’s CCCH ZnFs per length of bound RNA, we solved the structure of crystals grown from a mixture of purified ZnF1–6 and the 18-nt HSPA8 RNA substrate at 2.3-Å resolution (Table 1). This structure, however, contained only ZnF4–6 in complex with the UUAG segment of the target RNA (Fig. 2a); ZnF1–3 appeared to have been cleaved off at the site of the unstructured linker sequence separating both sets of three ZnFs (Supplementary Note).

Table 1. Data collection and refinement statistics.

| Mouse Unk–ZnF4–6 RNA complex |

Mouse Unk–ZnF1–3 RNA complex |

|

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | Zn SAD | Zn SAD |

| Space group | C2 | P22121 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 70.2, 51.2, 37.5 | 43.2, 56.6, 131.0 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0, 97.2, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 40–2.3 (2.4–2.3)a | 131–1.8 (1.9–1.8) |

| R merge | 4.0 (44.7) | 8.3 (96.7) |

| I / σI | 16.0 (1.9) | 14.6 (1.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 96.7 (85.5) | 99.4 (98.3) |

| Redundancy | 3.7 (2.4) | 6.6 (5.9) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 19.4–2.3 | 20–1.8 |

| No. reflections | 5,721 | 30,114 |

| Rwork / Rfree | 18.1 / 22.4 | 17.8 / 21.6 |

| No. atoms | 1,095 | 2,805 |

| Protein / RNA | 983 / 90 | 2,373 / 99 |

| Zn / sulfate ion | 3 / - | 6 / 20 |

| Water | 19 | 307 |

| B factors | 52.7 | 29.1 |

| Protein / RNA | 52.0 / 62.6 | 28.5 / 22.4 |

| Zn / sulfate ion | 60.9 / - | 31.0 / 67.0 |

| Water | 42.2 | 33.5 |

| r.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.008 | 0.007 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.2 | 1.0 |

A single crystal was used for each data set. SAD, single-wavelength anomalous dispersion.

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

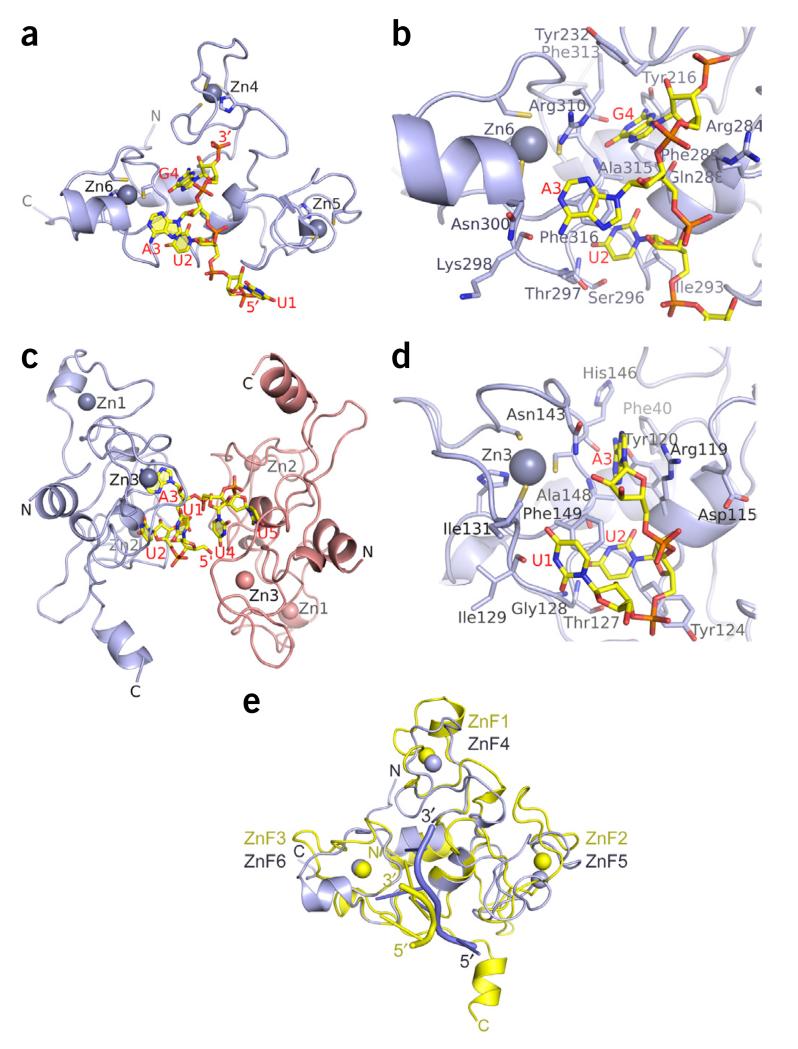

Figure 2.

Crystal structures of the CCCH ZnF clusters of Unkempt bound to their RNA substrates. (a,b) Structure of the ZnF4–6 cluster bound to a UAG-containing RNA. Ribbon and stick representation of the complex highlighting the overall fold of the ZnF4–6 cluster (light blue) and the position of the bound RNA (yellow) (a), and the key residues of the ZnF4–6 cluster contacting the bound UAG motif (b). Cysteine and histidine side chains coordinated to zinc atoms (Zn4, Zn5 and Zn6; light-blue balls) as well as the bound RNA molecules are shown in stick representation. (c,d) Structure of the ZnF1–3 cluster bound to a UUA-containing RNA. Ribbon-and-stick representation of the complex containing two protein molecules and one UUAUU RNA molecule in the crystallographic asymmetric unit (c) and the UUA motif bound on the surface of the ZnF1–3 cluster, highlighting the key side chain residues contacting the RNA (d). (e) Comparison of Unkempt’s ZnF1–3 bound to a U1-U2-A3 RNA element (yellow) and ZnF4–6 bound to a U1-U2-A3-G4 RNA element (light blue). Additional stereo views are in Supplementary Figure 3a.

The structure revealed the formation of a unique compact fold in Unkempt ZnF4–6, which at first glance resembled the fold of the ZnF domain of Nab2 (refs. 19,20), the only other known case in which three CCCH ZnFs form a single compact unit. Nevertheless, the ZnF4–6 of Unkempt adopts a different topology with no similarity to any structure annotated in the Protein Data Bank (Supplementary Fig. 1c and Supplementary Note).

The conformation of the ZnF4–6 cluster appears designed to specifically recognize the UAG trimer, a motif required for high-affinity binding of Unkempt to its RNA targets29. In this protein–RNA complex, two bases of the RNA, U2 and G4, are inserted into specific binding pockets, while A3 is packed against the surface formed by the ZnF6 (Figs. 2 and 3a). The specificity of the UAG sequence recognition is conferred predominantly through hydrogen-bonding of the Watson-Crick edges of each base with the ZnF6 backbone and the side chains of Tyr216 and Gln288 (Fig. 3b,c).

Figure 3.

Intermolecular protein-RNA recognition in Unkempt complexes involving ZnF clusters. (a) Electrostatic surface view of the ZnF4–6 cluster with the bound UAG motif highlighting insertion of U2 and G4 in the pockets and packing of A3 against the surface of ZnF6. (b,c) Hydrogen-bonding, stacking and van der Waals interactions of U2 and A3 (b) and G4 (c) with the backbone and side chain residues of ZnF4–6. (d) Electrostatic surface view of the ZnF1–3 cluster with the bound UUA motif, highlighting insertions of U2 and A3 in the pockets and packing of U1 against the surface of ZnF3. (e,f) Hydrogen-bonding, stacking and van der Waals interactions of U1 and U2 (e) and A3 (f) with the backbone and side chain residues of ZnF1–3. The electrostatic surface views were generated with GRASP and PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org/). The bound RNA molecules are in stick representation.

The N-terminal ZnF–3 cluster recognizes the U-rich motif

To examine the RNA sequence specificity of the ZnF1–3 domain, we carried out extensive crystallization trials with a recombinant ZnF1–3 construct and various oligonucleotides derived from the HSPA8 18-mer RNA sequence downstream of the UAG motif. We obtained crystals of ZnF1–3 in the presence of a UUAUU pentamer RNA and solved the structure of the complex at a resolution of 1.8 Å (Table 1 and Fig. 2c). This complex consisted of two molecules of ZnF1–3 and one RNA molecule in the crystallographic asymmetric unit (Fig. 2c), with one protomer binding the 5′ end of the pentamer (nucleotides U1-U2-A3) and the other protomer binding the two remaining uridines (U4 and U5).

Similarly to the ZnF4–6 cluster, the ZnF1–3 domain assumes a compact fold with a spatial arrangement conferred by essentially the same core interactions as in ZnF4–6 (Supplementary Figs. 1d and 2). Both clusters contain several key residues that contact their respective target RNA motifs (Fig. 2b,d, Supplementary Note and two complexes superposed in Fig. 2e and in stereo in Supplementary Fig. 3a).

The UUA motif is bound on the surface of the ZnF1–3 cluster (Figs. 2d and 3d), which is analogous to the surface occupied by the UAG motif in the ZnF4–6 cluster (Figs. 2b and 3a). Likewise, the second and the third base, U2 and A3 in the ZnF1–3 complex, are inserted in separate pockets (Fig. 3d), similarly to U2 and G4 in the ZnF4–6 complex (Fig. 3a). The first base, U1 of the UUA motif, is packed against the surface of the ZnF3 in a flipped-over orientation (Fig. 3e), while A3 adopts a syn alignment in the ZnF1–3 complex (Fig. 3f). As a result, the sugar-phosphate-backbone conformation of the UUA trimer bound to ZnF1–3 (Fig. 2d) is drastically different from that of the UAG trimer bound to ZnF4–6 (Fig. 2b and superposition of complexes in stereo in Supplementary Fig. 3b,c). The specificity of the UUA sequence recognition is conferred predominantly through hydrogen-bonding of the Watson-Crick edges of each base with the ZnF3 backbone (Fig. 3e,f).

Together, these structures reveal a new RNA-binding fold wherein three CCCH ZnFs form a compact globular unit that specifically recognizes a continuous sequence of three ribonucleotides. Two such clusters of Unkempt, ZnF1–3 and ZnF4–6, recognize different sequence motifs with different affinities in a cooperative manner. Whereas the ZnF4–6 cluster exhibits a high affinity for the UAG motif, the ZnF1–3 cluster recognizes the UUA sequence with somewhat weaker affinity. Interestingly, as previously indicated, the base composition of the U-rich motif varies in vivo and may consist of either uracils or adenines without substantially affecting the overall binding affinity of the Unkempt protein29.

Base composition and relevance of the U-rich motif

To determine the prevalence of different U-rich sequences in vivo, we reexamined our individual-nucleotide-resolution cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (iCLIP) data generated for the endogenous Unkempt in mouse brain SH-SY5Y cells, as well as for ectopically expressed Unkempt in HeLa cells29, and looked for enrichment of each of the 64 possible triplets within Unkempt-binding sites (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 4). Unbiased hierarchical clustering segregated the occurrence pattern of UAG from all other triplets; the UAG triplet was enriched 5′ of the binding-site maxima, whereas most other triplets showed either enrichment or depletion at or immediately 3′ of the binding-site maxima (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Definition and functional importance of the U-rich RNA motif. (a) Base composition of the U-rich motif in the mouse embryonic brain. The heat map illustrates positional frequency of the 64 possible trimers within Unkempt-binding sites between 15 nt upstream and downstream of the binding-site maxima. The plot above the heat map profiles the mean enrichment of different sets of triplets, color-coded as shown in the heat map (red, UAG; blue, 13 enriched U-rich triplets; gray, all other triplets). The enrichment scale below the heat map indicates fold enrichment over the median triplet frequency in a 103-nt window around the binding-site maxima. Additional data and information are in Supplementary Figures 4 and 5 and Online Methods. (b) Effects of the U-rich motif on the in vitro RNA binding affinity of ZnF1–6. Shown are ITC binding profiles for the indicated synthetic 10-mer RNA substrates. Kd values are shown as mean ± range of two independent technical replicates. ND, Kd could not be determined. Data representation is as in Figure 1c,d. (c) Metaprofile of Unkempt-binding sites in an 800-nt window around stop codons on target transcripts. Binding sites were summarized into 10-nt bins. The solid line depicts local regression. (d) Metaprofile analysis showing the coverage with U-rich triplets per nucleotide around all Unkempt-bound (n = 578) and nonbound (n = 17,185) out-of-frame UAGs in the coding regions as well as around all UAG stop codons (n = 468) of the bound genes.

To test whether the in vivo frequency of individual U-rich triplets might be correlated with the binding affinity of Unkempt, we measured the in vitro affinity of Unkempt ZnF1–6 for RNA oligonucleotides containing the UAG motif spaced by two ribonucleotides from the interrogated triplet (Fig. 4b). Indeed, oligonucleotides containing either of the two examined highly enriched triplets, UUA and GUU, showed the strongest affinities; a sequence containing the less abundant AAU was less tightly bound; and the oligonucleotides with the nonenriched or depleted triplets, GCG or GUG, were not bound (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Fig. 5). Of note, the lack of ZnF1–6 affinity for the GCG- or GUG-containing RNA substrates despite the presence of the UAG motif is in agreement with the notion that a GC-rich environment inhibits RNA binding by Unkempt29. Together, these analyses illustrate the binding-site preference of Unkempt by defining the composition and positional frequency of each of the two Unkempt-binding motifs that constitute the URE.

Binding sites of Unkempt predominantly map to coding regions of target genes and are broadly distributed along the gene length29. However, Unkempt is almost completely absent at stop codons (Fig. 4c), a surprising result given that the mandatory UAG motif matches the sequence of one of the stop codons. Because two recognition motifs of Unkempt are required for the high-affinity RNA binding, we asked whether the second, U-rich motif is adequately enriched downstream of the actual UAG stop codons. To address this question, we examined the frequency of the 13 most common triplets constituting the U-rich motif in the vicinity of the bound and nonbound UAGs within the coding regions as well as the stop codons. Notably, in contrast to the bound, out-of-frame UAGs, which showed a substantial accumulation of the U-rich motif at their 3′ sides, as expected, the stop codon UAGs resembled the nonbound UAGs, lacking the 3′ peak (Fig. 4d). Thus, the absence of the U-rich recognition motif could explain, at least in part, the relatively lower occupancy of the annotated stop codons by Unkempt.

Structure-guided mutations affect RNA binding affinity

To assess the significance of individual amino acid residues in contact with specific bases of the 18-mer HSPA8 URE, we used ITC to measure the RNA binding affinity of the alanine-mutated ZnF1–6 domain (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Note). Whereas mutations in the ZnF1–3 cluster resulted in a modest reduction in binding affinity (Fig. 5a,c), mutations of the corresponding amino acid residues in the UAG-binding ZnF4–6 cluster had a much stronger effect on RNA binding affinity (Fig. 5b,c). Thus, consistently with their specificities of RNA binding, the ZnF4–6 cluster exhibits a higher sensitivity to mutations than does the more promiscuous ZnF1–3 cluster.

Figure 5.

Effects of structure-guided mutations on the RNA binding affinity of Unkempt. (a,b) Binding of the wild-type or mutated recombinant ZnF1–6 of Unkempt to HSPA8 18-mer RNA. Single- or double-residue conversions to alanine were introduced into the ZnF1–3 cluster (a) or ZnF4–6 cluster (b), and the resulting mutants were tested by ITC, as indicated. (c) Quantification of the results in a and b. Kd values for individual mutants are the mean of two independent technical replicates. Bars indicate range. (d) RNA binding affinity of Unkempt mutants in vivo. Shown is a result of the CLIP experiment on HeLa cells inducibly expressing wild-type or mutant Unkempt proteins. IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, western blot; UNK, Unkempt. Additional information in Online Methods. Uncropped images of the blots are shown in Supplementary Data Set 1.

To examine whether the in vitro-observed effects of mutations also translate in vivo, we carried out CLIP to determine the extent of RNA binding by the different Unkempt mutants in doxycycline (Dox)-inducible HeLa cells. Immunoprecipitation of the labeled UV-cross-linked complexes revealed strong associations of the wild-type Unkempt with RNA (Fig. 5d). Mutations in the ZnF1–3 cluster had a milder effect on RNA binding, whereas all tested mutations to the ZnF4–6 cluster severely perturbed Unkempt-RNA interactions, consistently with the reduced binding affinities measured in vitro.

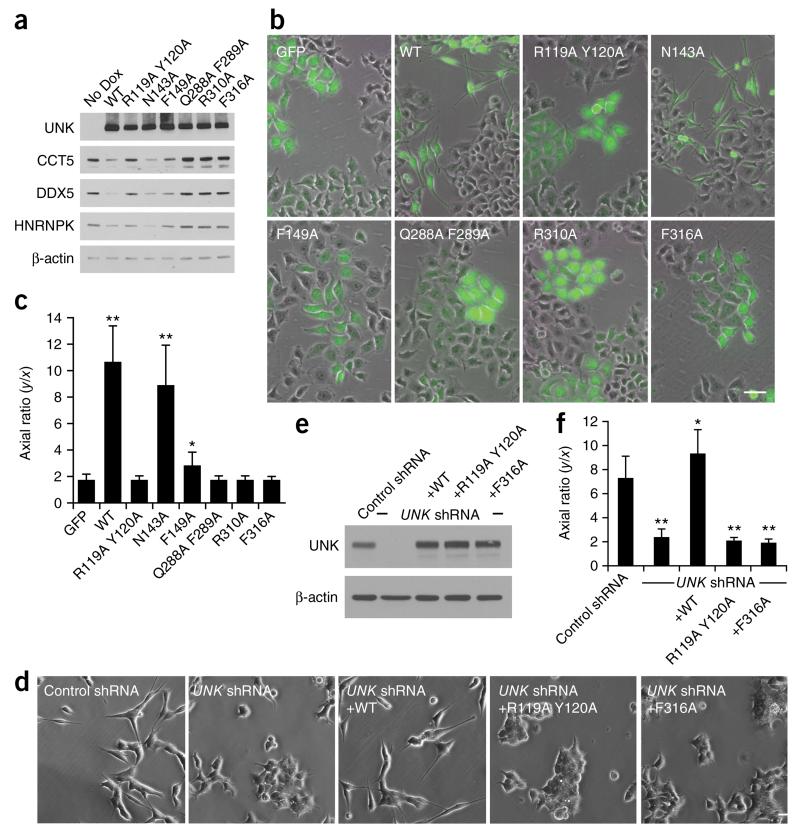

Effects of mutations on translation and cell polarization

Unkempt has previously been shown to represses translation by lowering ribosome occupancy specifically on its target transcripts29. To explore the requirement of key structural residues for translational control by Unkempt, we selected three high-confidence Unkempt targets, CCT5, HNRNPK and DDX5 (ref. 29), and analyzed their expression upon induction of the wild-type or mutated Unkempt proteins in HeLa cells (Fig. 6a). We observed a strong anticorrelation between the levels of detected target proteins and the RNA binding affinity of Unkempt in the corresponding samples; wild-type Unkempt and the N143A mutant tightly bound to RNA and substantially reduced the expression of all three target proteins, whereas the weaker binding mutants, particularly the ZnF4–6 mutants, had less to no reducing effect on the endogenous target-protein levels (Supplementary Fig. 6a). These findings indicate that post-transcriptional gene regulation by Unkempt directly and critically depends on the structural and RNA binding properties of the CCCH ZnF domain.

Figure 6.

Effects of RNA-contacting residues on protein translation and cellular polarization. (a) Protein levels of three high-confidence Unkempt (UNK) targets, CCT5, DDX5 and HNRNPK, in inducible HeLa cells, measured by immunoblotting after 60 h of treatment with Dox. Additional data in Supplementary Figure 6a. Uncropped images of the blots are shown in Supplementary Data Set 1. (b) Representative images (from a total of ten images collected per condition) of HeLa cells inducibly expressing GFP or GFP and either wild-type or mutant Unkempt protein, as indicated, after 48 h of treatment with Dox. Scale bar, 50 μm. (c) Cell morphologies quantified after 48 h of Dox treatment. The results are compared with GFP control. Error bars, s.d. (n = 30 GFP-positive cells). *P = 0.00005; **P < 0.00001 by two-tailed Student’s t test. (d) Representative images (from a total of ten images collected per condition) of SH-SY5Y cells stably expressing either control or UNK-targeting shRNA and either wild-type or mutant Unkempt protein, as indicated. Scale bar, 50 μm. (e) Immunoblot analysis showing expression levels of Unkempt in cells used for the morphologic analysis in f. The uncropped image of the blot is shown in Supplementary Data Set 1. (f) Quantification as in c of the morphologies of SH-SY5Y cells stably expressing the indicated constructs. The results are compared with control shRNA. Error bars, s.d. (n = 30 cells). *P = 0.00968; **P < 0.00001 by two-tailed Student’s t test.

Unkempt regulates the early neuronal morphology during embryonic development, and its expression is sufficient to endow a bipolar morphology to cells of non-neuronal lineages29. Given their reduced affinity for RNA and their impaired translational regulation, we asked whether the above Unkempt mutants could still induce bipolar cellular morphology in amorphous HeLa cells. Notably, the morphogenetic effect of Unkempt appeared to be strictly dependent on the intact RNA-binding domain (Fig. 6b,c). With the exception of N143A, all other mutations, including Y216A, significantly affected or completely eliminated the polarizing activity of Unkempt (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 6b–e). Because of the relatively high levels of Unkempt expression achieved with this system, and because we used non-neuronal cells, we wished to validate our findings in a more physiologically relevant setting, using near-endogenous levels of ectopic Unkempt in neuronal cells. Indeed, add-back of wild-type but not mutated Unkempt (R119A Y120A or F316A) restored the bipolar morphology of Unkempt-deficient SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 6d–f). The early neuronal morphology is thus strictly dependent on the native affinity of Unkempt for RNA. Although the high phenotypic sensitivity to the F149A or the Y216A mutations, which only mildly reduced the RNA binding affinity (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 6), may seem unexpected, it is conceivable that relatively small perturbations in RNA binding and translational control by Unkempt of more than 1,000 target mRNAs may manifest a much greater consequence in a living cell.

Conservation of RNA binding and cellular morphogenesis

The origins of Unkempt protein can be traced back roughly 600 million years to the emergence of metazoans and the evolution of the neuronal lineage29,30. We noted that the key amino acid residues within the six CCCH ZnFs of Unkempt have remained conserved between the demo-sponge Amphimedon queenslandica, one of the earliest metazoans with a sequenced genome, and more advanced eukaryotes including humans (Supplementary Fig. 7). Notably, we found that Unkempt orthologs of mouse, zebrafish, worm and sponge all recognized the wild-type URE with comparable affinities, although the sponge ortholog bound slightly less tightly than the mouse and zebrafish counterparts (Fig. 7a). Moreover, the high affinity of each ortholog for the URE was strongly dependent on the presence of the UAG motif, thus suggesting a deep evolutionary conservation of the RNA binding specificity of Unkempt.

Figure 7.

Evolutionary conservation of RNA binding specificity and morphogenetic activity of Unkempt. (a) RNA binding by recombinant ZnF1–6 domains of the indicted Unkempt orthologs. The affinity of each ZnF1–6 for the wild-type (5′-ACUUAGAAUUAUUAAUGA-3′) or UAG-mutated (5′-ACUCCCAAUUAUUAAUGA-3′) human HSPA8 URE was measured with ITC, with the Kd values (mean ± range of two independent technical replicates), binding enthalpy (ΔH) and number of binding sites per monomer (N) shown. Sequence alignments are in Supplementary Figure 7. (b,c) Induction of bipolar cellular morphology by mouse, fish and sponge orthologs of Unkempt. (b) Representative images (from a total of ten images collected per condition) of HeLa cells inducibly expressing GFP and one of the indicated Unkempt orthologs after 48 h of treatment with Dox. Scale bar, 50 μm. (c) Quantification of the morphologies of GFP-negative cells (control) and GFP- and Unkempt-expressing cells (Unk). Error bars, s.d. (n = 30 cells). *P < 0.005; **P < 0.00005 by two-tailed Student’s t test.

Interestingly, all tested Unkempt orthologs endowed otherwise amorphous HeLa cells with a polarized morphology (Fig. 7b). In correlation with their RNA binding affinities, the morphogenetic potencies of zebrafish and mouse Unkempt proteins were comparable, whereas the sponge ortholog appeared somewhat less active (Fig. 7b,c). These data suggest that the structure and the RNA binding properties, as well as the intrinsic activity of Unkempt to polarize cells, has undergone little evolutionary change.

DISCUSSION

The ZnF1–3 and ZnF4–6 clusters of Unkempt recognize an unexpectedly short stretch of RNA sequence—only three consecutive ribonucleotides—with a varying degree of specificity. Although the structure of the yeast Nab2 protein similarly contains an aggregate of three ZnFs, these assume a different conformation that binds five to eight adenosines19,20, a number roughly within the common range of two to four bound ribonucleotides per CCCH ZnF. Despite the unusual topologies of the ZnF clusters of Unkempt, the RNA-base recognition is mediated predominantly by hydrogen-bonding interactions between the protein backbone and the Watson-Crick edges of bases, analogously to that in TIS11d17 or MBNL1 (ref. 18) complexes with their RNA targets.

It would seem counterproductive for a protein to evolve a bulky structure such as a ZnF cluster with the sole purpose of recognizing a specific RNA triplet; although a unique conformation of a ZnF cluster clearly matters, a single CCCH ZnF could in principle substitute for an entire cluster in recognizing a trinucleotide sequence (Supplementary Note). We speculate that the bulkiness of a CCCH ZnF cluster might fulfill requirements beyond the affinity for RNA alone. For instance, the large size of a cluster could provide a surface for interactions of Unkempt with ribosomes and other proteins with which Unkempt is known to associate29,31. Notably, we found 13 other mostly unstudied human proteins with an apparent apposition of three or more CCCH ZnFs similar to the linear arrangement seen in Unkempt (data not shown). Although these proteins have no known binding motifs, and their CCCH ZnFs may recognize RNA in unrelated manners, it is intriguing that for one of them, ZC3H10, the consensus binding motif has recently been determined to be a trinucleotide, GCG32. Whether the ZnFs of ZC3H10 and other proteins form a cluster similar to ZnF1–3 and ZnF4–6 of Unkempt, and whether the formation of such a cluster could broadly predict the regulatory function of an RBP, remains to be determined.

Despite our intense efforts to crystalize the entire ZnF1–6 domain in complex with the full URE, the cleavage at the site of the linker peptide led to a separation of the ZnF clusters. The unstructured nature, fragility and poor sequence conservation of this linker segment suggest that it may serve to allow for flexible separation and orientation of the two ZnF clusters. As is the case for numerous other RBPs with a modular architecture, the two clusters, or modules, of Unkempt could recognize motifs separated by an intervening stretch of ribonucleotides or that belong to different RNA molecules26. However, given the short distance separating the UAG and the U-rich motif, on average just two to three ribonucleotides, and because we found no evidence for dimer formation by Unkempt, we favor a model in which both ZnF clusters interact with parts of the same URE (Supplementary Fig. 8).

The deep and exclusive conservation of all six CCCH ZnFs of Unkempt across metazoans along with the high sensitivity to mutations highlight the functional importance of the RNA binding. This is further supported by the capacity of the mouse, zebrafish and sponge Unkempt orthologs to polarize human cells and the ability of several point mutations of Unkempt to abolish this activity. Our findings thus suggest that the sequence specificity and the overall function of Unkempt have remained largely unchanged during the evolution of animal species. Interestingly, two previous studies have supported a neuronal role of Unkempt during fruit fly development; one study documented its localization to the central nervous system during later embryonic stages and an unkempt phenotype of the hypomorphs28, whereas the other reported a role for Unkempt in neuronal differentiation31. Of note, the evolution of the neuronal lineage itself appears to have coincided with the emergence of Unkempt30. Sponges, the metazoan ancestors in which Unkempt was first detected, lack nerve cells but contain elongated larval globular cells that are part of a complex sensory system along with several molecules required for nerve-cell function; these protoneural components are thought to have connected into a functional neuron in eumetazoans30. We hypothesize that the ancestral Unkempt, already equipped with the full set of CCCH zinc fingers, might have had a key role in the evolution of neuronal morphology.

The compact CCCH ZnF clusters of Unkempt present a new RNA-binding unit with a unique topology and substrate specificity. Given the high abundance of CCCH-type RBPs and their wide functional diversity in organisms including yeast and humans, it will be important to determine the prevalence of CCCH ZnF clusters, the rules that predict their formation and the set of properties beyond RNA binding that they may impart to proteins. These properties may include various processes linked to protein-RNA interactions and post-transcriptional control, including co-recruitment of other proteins, organization of the bound RNA into higher-order structures, or modulation of the access of other RBPs to RNA.

With regard to Unkempt, future work is required to validate our proposed model of RNA binding, particularly to determine the relative orientation of each cluster in the complex of ZnF1–6 bound to a full-length URE and to assess the intercluster flexibility conferred by the intervening linker peptide. Additional studies are also warranted to investigate other determinants that may guide Unkempt to its specific binding sites on target transcripts and to provide more insight into the overall mechanism of translational regulation by Unkempt.

Finally, for a more comprehensive but also elementary understanding of this small RNA–binding domain, we may need to consider redefining the canonical peptide sequence of the CCCH ZnF, which was initially set as CX6–14CX4-5CX3H (ref. 33) and was later corrected to CX4–15CX4–6CX3H (ref. 34). Even with the broader definition of this domain, some cases of CCCH ZnFs escape bioinformatics-based detection. These include the CCCH ZnF1 of Unkempt, the primary sequence of which is CX7CX7CX3H, and the CCCH ‘zinc wing’ of the Zucchini protein (CX16CPCX3H), a nuclease participating in biogenesis of primary piwi-interacting RNAs16. We propose a new consensus motif of CX4–16CX1–7CX3H to capture these and similar atypical cases of CCCH ZnFs. However, we caution that any CCCH ZnF newly predicted on the basis of our proposed expanded consensus motif should be carefully evaluated biochemically and structurally to confirm its actual existence.

ONLINE METHODS

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

cDNA fragments encoding the ZnF1–6 domain (31–335), the ZnF1–3 domain (31–174), or the ZnF4–6 domain (204–335) of mouse Unkempt protein were PCR-amplified and cloned into a modified pRSF-Duet1 vector (Novagen) between the unique BamHI and XhoI restriction sites for the expression of His-SUMO N-terminally tagged fusion proteins. Single and double mutations of Unkempt (N143A, F149A, F316A, R310A, Y216A, R119A Y120A, and Q288A F289A) were introduced into the plasmids by site-directed mutagenesis with a QuikChange II XL kit (Agilent) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasmids were transformed into the Escherichia coli strain BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL (Stratagene), and the bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertrani (LB) medium supplemented with 50 mg/ml kanamycin. Expression of recombinant proteins was induced by addition of 0.4 mM IPTG followed by 12 h of incubation at 18 °C. The bacterial cell pellets were lysed with a French press and further clarified by centrifugation at 40,000 r.p.m. The proteins were then purified from the soluble fraction by a nickel-chelating affinity column HisTrap (GE Healthcare), and this was followed by cleavage of the N-terminal His-SUMO tag with Ulp1 protease and additional purification by sequential chromatography on HiTrap Q HP, HiTrap Heparin, and Superdex 75 columns (all from GE Healthcare). Protein purity was monitored by SDS-PAGE.

Crystallization, data collection, and crystal-structure determination

Synthetic RNA oligonucleotides (Dharmacon) were deprotected and desalted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Crystallization conditions for the complexes of Unkempt ZnF1–6 with 5′-ACUUAGAAUUAUUAAUGA-3′ RNA and ZnF1–3 with 5′-UUAUU-3′ RNA were determined with matrix screens (Hampton Research and Qiagen) by sitting-drop vapor diffusion with a Mosquito crystallization robot (TTP Labtech). The ZnF4–6-RNA complex was crystallized by mixing equal volumes (0.2 μl) of 0.3 mM complex solution containing an equimolar ratio of ZnF1–6 protein and RNA in 25 mM Tris, pH 7.2, 0.2 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 40 μM ZnCl2 and reservoir solution containing 0.1 M HEPES, pH 7.0, and 17% PEG 3350. Crystals of the ZnF1–3–RNA complex (0.5 mM protein, 0.5 mM RNA, 25 mM Tris, pH 7.2, 0.2 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 40 μM ZnCl2) were grown in 0.2 M lithium sulfate, 0.1 M Tris, pH 8.5, and 25% (w/v) PEG 3350. Droplets were equilibrated against 0.1-ml reservoirs at 20 °C. For data collection, crystals were cryoprotected in reservoir solution supplemented with 40% PEG 3350 and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

The data were collected on the 24-ID beamline at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) and processed with HKL2000. Crystals of the ZnF4–6–RNA complex belonged to space group C2, with one protein and one RNA molecule per asymmetric unit. Crystals of the ZnF1–3–RNA complex belonged to space group P22121with two protein and one RNA molecules per asymmetric unit. Crystal and diffraction data characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Structures of both Unkempt–RNA complexes were determined by SAD phasing with the anomalous diffraction data collected at the Zn edge at a 1.2837-Å wavelength. The AutoSol Wizard of the PHENIX package35 was used for phasing and density modification. The initial experimental maps showed clear density for most regions of the protein-RNA complexes. Iterative manual model building and refinement with phenix.refine produced the current models of the complexes. All protein residues in both structures are in the allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot as evaluated by phenix.refine. Refinement statistics are given in Table 1.

Comparison of Unkempt’s ZnF1–3 bound to a U1-U2-A3 RNA element and ZnF4–6 bound to a U1-U2-A3-G4 RNA element in Figure 2e was performed by superimposing the most C-terminal ZnFs in both clusters, i.e., ZnF3 and ZnF6.

The interdomain linker and the 1- or 3-nt spacer connecting the UAG and the UUA motifs shown in Supplementary Figure 8 are idealized structures modeled with the Coot toolkit, whereas the remainder of each model in Supplementary Figure 8 is based on the X-ray structures of the complexes.

ITC measurements

ITC measurements were performed at 25 °C with an iTC200 calorimeter (Microcal). Protein and RNA samples were dialyzed in 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, containing 100 mM NaCl, 40 μM ZnCl2, and 1 mM DTT. The protein concentration range in the cell of volume 200 μl was 0.02–0.05 mM. The RNA concentration range in the injection syringe of volume 60 μl was 0.2–0.5 mM. The data were analyzed with the Microcal ORIGIN software with a single site-binding model.

Cell culture and derivation of mutant Unkempt-inducible cell lines

HeLa or SH-SY5Y cells were obtained from ATCC (http://www.atcc.org/) and were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The parent and all derived stable HeLa and SH-SY5Y cell lines were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Plasmids for Dox-inducible expression of mutant mouse full-length Unkempt proteins were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of the pTtight-Flag-HA-Unk-IGPP plasmid29. Zebrafish and sponge Unkempt orthologs were amplified from cDNAs for the respective source organisms and cloned into the pTt-IGPP vector29. HeLa cells stably expressing the rtTA3-IRES-EcoR-PGK-Neo cassette29 were infected with ecotropic retroviruses expressing the puromycin resistance gene and a TREtight-driven transcript encoding GFP and either of the Unkempt proteins. To induce transgene expression, double-selected cells were treated with doxycycline (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1 μg/ml.

To create stable SH-SY5Y lines for the rescue experiment, human neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y) stably expressing control shRNA or UNK shRNA were infected with MSCV-based retroviruses expressing wild-type or mutant mouse Unkempt. Cells with genomic integration of the transgene were selected in the presence of puromycin.

UV cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP)

CLIP of ectopically expressed wild-type or mutant Unkempt proteins in HeLa cells was carried out essentially as described previously29. GFP and Unkempt-inducible HeLa cells were treated with Dox for 24 h and irradiated with UV light (254 nm), and immunoprecipitation of the cross-linked Unkempt–RNA complexes was performed with anti-Unkempt antibody (HPA023636, Sigma-Aldrich)29. The CLIP experiment was repeated in four replicates and a representative result is shown (Fig. 5d)

SDS-PAGE and western blotting

Whole cell lysates of inducible HeLa cells were run on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to supported nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) by standard methods. Membranes were blocked for 1 h in 5% nonfat dry milk in 1× TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST), rinsed, and incubated with primary antibody diluted in 3% BSA in TBST overnight at 4 °C. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-UNK (HPA023636, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-β-actin-peroxidase (A3854, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-CCT5 (sc-374554, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-DDX5 (sc-81350, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-HNRNPK (sc-28380, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Validation of these antibodies is provided on the manufacturers’ websites and in our previous report29. Blots were washed in TBST, incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (AP307P and DC02L, both from EMD Millipore) in 5% milk in TBST for 1 h (except for the anti-β-actin-peroxidase antibody), and washed again. HRP signal was detected by Enhanced ChemiLuminescence (PerkinElmer).

Quantification of Unkempt-induced cellular morphology

After 48 h of incubation with Dox, the inducible HeLa cells were imaged, and the axes of GFP-positive cells were measured with Adobe Illustrator software (Adobe). The morphologies of 30 GFP-positive cells were quantified for each induced transgene by calculation of their axial ratios (y/x; y, length of the absolute longest cellular axis; x, length of the longest axis perpendicular to the y axis). The morphologies of SH-SY5Y cells, which did not express GFP, were quantified in the same manner but with no treatment with Dox.

Computational analyses of Unkempt-binding sites

The analyses were performed on major Unkempt-binding sites as determined previously29. All analyses were based on the human genome version hg19 (Ensembl v73/GENCODE v18) and the mouse genome version mm9 (Ensembl v65/GENCODE vM1), with only transcript annotations of support levels 1 and 2 (i.e., from verified and manually annotated loci). Briefly, binding sites were identified from collapsed replicate iCLIP data with a 5% false discovery rate and were further filtered for those that showed a minimum of five cross-link events per binding site and were completely included within the longest protein-coding transcript of only one gene. This procedure identified a total of 3,478, 2,312 and 2,837 binding sites for SH-SY5Y cells, HeLa cells, and mouse brain samples, respectively.

To assess the sequence composition at Unkempt-binding sites, we identified the position of the maximum within each binding site (i.e., the nucleotide with the highest number of cross-link events; the first was taken in the case of multiple nucleotides with equal counts) and extracted an extended window of 51 nt on either side. We counted the frequency of all 64 possible trinucleotides (triplets) at each position across all binding sites, counting each triplet on the first of three nucleotides (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). To correct for different background levels, we further normalized the frequency profile of each triplet to its median frequency across the complete 103-nt window.

To compare the spatial arrangement of different triplets, we performed unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the normalized triplet profiles in a 31-nt window around the binding-site maxima from mouse embryonic brain (Fig. 4a). The resulting dendrogram was split into subtrees to obtain three sets of triplets with similar spatial distribution: (i) UAG, (ii) AUU, CUU, GUU, UUA, UUU, UUC, UAC, UAU, UCG, UCA, UCC, UAA, UUG, and (iii) all remaining triplets. Triplet frequencies in each set were combined into a summarized profile (Fig. 4a). Triplet profiles for Unkempt-binding sites in SH-SY5Y and HeLa cells were ordered by the hierarchy and summarized into the triplet sets obtained for binding sites from mouse embryonic brain (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The triplet sets were also used to analyze the sequence composition flanking different groups of UAGs: (i) The identification of UAGs in the coding region was based on the longest protein-coding transcripts of all bound protein-coding genes in the mouse embryonic brain. UAGs that lay within a 20-nt window upstream of Unkempt-binding-site maxima were classified as bound. (ii) To obtain a complete set of UAG stop codons, we extracted stop codons from all protein-coding transcripts of bound genes. Triplet coverage was calculated by normalizing the summarized positional frequencies of each triplet set to the number of UAGs in each group (Fig. 4d).

For the profile of Unkempt binding around stop codons (Fig. 4c), we used the longest protein-coding transcript of all bound protein-coding genes and extracted binding sites from SH-SY5Y cells within an 800-nt window around the stop codons (500 nt upstream plus 300 nt downstream). We then summed all cross-link events in 10-nt bins within the 800-nt window.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the staff of the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team for their assistance with collection of the X-ray data; to K. Kathrein (Boston Children’s Hospital) for zebrafish cDNA, E. Greer (Boston Children’s Hospital) for worm cDNA and K. Roper (University of Queensland) for sponge cDNA; and to members of the laboratories of D.J.P. and Y.S. for discussion and comments on the manuscript. This study was supported by the Nancy Lurie Marks Post-doctoral Fellowship (J.M.), the LOEWE program Ubiquitin Networks (Ub-Net) of the State of Hesse (Germany) (K.Z.), US National Institutes of Health grants MH096066 (Y.S.) and GM104962 (D.J.P.), and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center support Grant/Core Grant (P3O CA008748) (D.J.P.). Y.S. is supported as an American Cancer Society Research Professor.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M. and M.T. performed the experiments; K.Z. carried out the computational analysis of sequencing data; J.M., M.T., K.Z., Y.S. and D.J.P. analyzed and interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare competing financial interests: details are available in the online version of the paper.

Accession codes. Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes PDB 5ELH(Unkempt ZnF1–3-RNA) and PDB 5ELK (ZnF4–6-RNA).

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Cook KB, Kazan H, Zuberi K, Morris Q, Hughes TR. RBPDB: a database of RNA-binding specificities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D301–D308. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daubner GM, Cléry A, Allain FH. RRM-RNA recognition: NMR or crystallography...and new findings. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013;23:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall TM. Multiple modes of RNA recognition by zinc finger proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2005;15:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valverde R, Edwards L, Regan L. Structure and function of KH domains. FEBS J. 2008;275:2712–2726. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tenlen JR, Schisa JA, Diede SJ, Page BD. Reduced dosage of pos-1 suppresses Mex mutants and reveals complex interactions among CCCH zinc-finger proteins during Caenorhabditis elegans embryogenesis. Genetics. 2006;174:1933–1945. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.052621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schubert CM, Lin R, de Vries CJ, Plasterk RH, Priess JR. MEX-5 and MEX-6 function to establish soma/germline asymmetry in early C. elegans embryos. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:671–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tenenhaus C, Subramaniam K, Dunn MA, Seydoux G. PIE-1 is a bifunctional protein that regulates maternal and zygotic gene expression in the embryonic germ line of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1031–1040. doi: 10.1101/gad.876201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carballo E, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. Feedback inhibition of macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by tristetraprolin. Science. 1998;281:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsushita K, et al. Zc3h12a is an RNase essential for controlling immune responses by regulating mRNA decay. Nature. 2009;458:1185–1190. doi: 10.1038/nature07924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller JW, et al. Recruitment of human muscleblind proteins to (CUG)(n) expansions associated with myotonic dystrophy. EMBO J. 2000;19:4439–4448. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanadia RN, et al. A muscleblind knockout model for myotonic dystrophy. Science. 2003;302:1978–1980. doi: 10.1126/science.1088583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang J, Song W, Tromp G, Kolattukudy PE, Fu M. Genome-wide survey and expression profiling of CCCH-zinc finger family reveals a functional module in macrophage activation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang ET, et al. Transcriptome-wide regulation of pre-mRNA splicing and mRNA localization by muscleblind proteins. Cell. 2012;150:710–724. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barabino SM, Hübner W, Jenny A, Minvielle-Sebastia L, Keller W. The 30-kD subunit of mammalian cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor and its yeast homolog are RNA-binding zinc finger proteins. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1703–1716. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jadhav S, Rana M, Subramaniam K. Multiple maternal proteins coordinate to restrict the translation of C. elegans nanos-2 to primordial germ cells. Development. 2008;135:1803–1812. doi: 10.1242/dev.013656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ipsaro JJ, Haase AD, Knott SR, Joshua-Tor L, Hannon GJ. The structural biochemistry of Zucchini implicates it as a nuclease in piRNA biogenesis. Nature. 2012;491:279–283. doi: 10.1038/nature11502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hudson BP, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Recognition of the mRNA AU-rich element by the zinc finger domain of TIS11d. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:257–264. doi: 10.1038/nsmb738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teplova M, Patel DJ. Structural insights into RNA recognition by the alternative-splicing regulator muscleblind-like MBNL1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:1343–1351. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhlmann SI, Valkov E, Stewart M. Structural basis for the molecular recognition of polyadenosine RNA by Nab2 Zn fingers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:672–680. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brockmann C, et al. Structural basis for polyadenosine-RNA binding by Nab2 Zn fingers and its function in mRNA nuclear export. Structure. 2012;20:1007–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blackshear PJ. Tristetraprolin and other CCCH tandem zinc-finger proteins in the regulation of mRNA turnover. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002;30:945–952. doi: 10.1042/bst0300945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pascual M, Vicente M, Monferrer L, Artero R. The Muscleblind family of proteins: an emerging class of regulators of developmentally programmed alternative splicing. Differentiation. 2006;74:65–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson JT, Wilson SM, Datar KV, Swanson MS. NAB2: a yeast nuclear polyadenylated RNA-binding protein essential for cell viability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:2730–2741. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hector RE, et al. Dual requirement for yeast hnRNP Nab2p in mRNA poly(A) tail length control and nuclear export. EMBO J. 2002;21:1800–1810. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marfatia KA, Crafton EB, Green DM, Corbett AH. Domain analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein, Nab2p: dissecting the requirements for Nab2p-facilitated poly(A) RNA export. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:6731–6740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207571200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lunde BM, Moore C, Varani G. RNA-binding proteins: modular design for efficient function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:479–490. doi: 10.1038/nrm2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martínez-Lumbreras S, Santiveri CM, Mirassou Y, Zorrilla S, Pérez-Cañadillas JM. Two singular types of CCCH tandem zinc finger in Nab2p contribute to polyadenosine RNA recognition. Structure. 2013;21:1800–1811. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohler J, et al. The embryonically active gene, unkempt, of Drosophila encodes a Cys3His finger protein. Genetics. 1992;131:377–388. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.2.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murn J, et al. Control of a neuronal morphology program by an RNA-binding zinc finger protein, Unkempt. Genes Dev. 2015;29:501–512. doi: 10.1101/gad.258483.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srivastava M, et al. The Amphimedon queenslandica genome and the evolution of animal complexity. Nature. 2010;466:720–726. doi: 10.1038/nature09201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Avet-Rochex A, et al. Unkempt is negatively regulated by mTOR and uncouples neuronal differentiation from growth control. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ray D, et al. A compendium of RNA-binding motifs for decoding gene regulation. Nature. 2013;499:172–177. doi: 10.1038/nature12311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berg JM, Shi Y. The galvanization of biology: a growing appreciation for the roles of zinc. Science. 1996;271:1081–1085. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang D, et al. Genome-wide analysis of CCCH zinc finger family in Arabidopsis and rice. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.