Abstract

With the increasing availability of integrated PET/MR scans the utility and need for MR contrast agents for combined scans is questioned. The purpose of our study was to evaluate if the administration of gadolinium chelates is necessary for evaluation of pediatric tumors on 18F-FDG-PET/MR scans.

Methods

First, we compared the diagnostic accuracy of pre-contrast T2-weighted fast spin echo (FSE), diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and T1-weighted MR scans with post-contrast gadolinium chelate enhanced T1-weighted MR scans for the evaluation of 14 diagnostic criteria in 119 pediatric patients with primary and secondary tumors. We next fused 18F-FDG PET scans with either unenhanced T2-weighted MR scans or gadolinium chelate enhanced T1-weighted MR scans in a subset of 36 pediatric patients. We compared the same 14 diagnostic criteria between fused 18F-FDG PET/T2-FSE and fused 18F-FDG PET/Gd-LAVA scans of 123 tumors in this subgroup and evaluated the concordance or discordance of 18F-FDG PET and gadolinium chelate enhancement, using McNemar’s test. Histopathology, surgical notes and follow up imaging served as the standard of reference.

Results

Pre- and post-contrast MR scans did not show significant differences in diagnostic accuracies of 14 diagnostic criteria that evaluated image quality and tumor origin, extent, composition and differential diagnosis. Accordingly, there was no significant difference in diagnostic accuracy of integrated 18F-FDG PET/T2-FSE and 18F-FDG PET/Gd-LAVA scans. The 18F-FDG PET/MR subgroup showed concordant gadolinium chelate enhancement and 18F-FDG avidity in 30 of 36 patients and 106 of 123 tumors.

Conclusion

Gadolinium chelate contrast administration is not necessary for accurate diagnostic characterization of most solid pediatric malignancies on integrated 18F-FDG-PET/MR scans. Exceptions may include focal liver lesions.

Keywords: PET/MR, PET-MR Fusion, Pediatric oncology, MR contrast utility, 18FDG-PET

Introduction

Magnetic Resonance (MR) Imaging is becoming the modality of choice for local staging of malignancies in pediatric patients, including neurogenic tumors (1), Wilms tumor (2), hepatoblastoma (3) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (4), germ cell tumors and sarcomas (5), among others (6). For some of these tumors, such as sarcomas and lymphomas, 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computer Tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) is added for whole body staging (7). Novel, integrated 18F-FDG PET/MR scans significantly reduce radiation exposure compared to 18F-FDG PET/CT scans. Combining local and whole body staging in one PET/MR session would enable “one stop shop” tumor staging and avoid duplicate anesthesias in small children. However, MR scans for local and whole body staging each take close to an hour of scan time (8). Economical and practical considerations mandate a streamlined protocol for local and whole body scans such that the combined exam could be done in about an hour or less. Initial 18F-FDG PET/MR studies of abdominal and pelvic tumors in adult patients have been performed by integration of 18F-FDG PET data with T2-weighted scans, in phase gradient echo scans or gadolinium chelate enhanced T1-weighted scans (9). Only one study has been published on integrated 18F-FDG PET/MR of pediatric cancers, where 18F-FDG PET data were integrated with water-sensitive fast inversion recovery sequence scans (10). To the best of our knowledge, nobody has systematically investigated whether gadolinium chelate contrast enhancement provides any additional information compared to “unenhanced” (no gadolinium chelate) 18F-FDG PET/MR scans generated either on an integrated PET-MR scanner or with software co-registration. The purpose of this study was to determine if the administration of gadolinium chelates is necessary for local staging of pediatric tumors on MR and 18F-FDG-PET/MR scans. If gadolinium chelate administration does not provide additional information, MR scans for local staging could be streamlined and gadolinium chelates could be replaced by alternative, more specific MR contrast agents (11, 12).

Materials and methods

Patients

The institutional review board at our institution approved this single center retrospective study and informed consent was waived. Inclusion criteria were patients 0–25 years of age, presenting with benign and malignant tumors, completed contrast enhanced MR imaging exam obtained between 2005 and 2013, and follow-up imaging studies for at least twelve months. Of note, we included both benign and malignant lesions in this cohort in order to consider all possible findings in a clinical setting. Exclusion criteria were loss to follow up and technically inadequate scans (e.g. motion artifacts, study not completed). We identified 119 patients that matched our inclusion and exclusion criteria. These 119 patients represented 66 males and 53 females with a mean age of 8.1 (±6.1) years. 103 patients had primary tumors. 8 patients had multiple liver metastases, 13 patients had multiple bone metastasis and 19 patients had lymph node metastasis. The pathological diagnoses of the total 119 patients as proven by histopathology and follow up imaging, are listed in Table1.

Table 1.

Distribution of various pathologies investigated in the study. The proportion of the investigated subgroup is shown in brackets.

| BENIGN | NO | MALIGNANT | NO |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIVER | |||

|

| |||

| Hemangioma | 1 | Hepatoblastoma | 10 |

| Hemangioendothelioma | 4 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 |

| Focal nodular hyperplasia | 8 | Hepatic metastases from neuroblastoma | 3 |

| Hepatic adenoma | 1 | ||

| Hepatic regenerative nodule | 6 | ||

| Hepatic abscess presenting as mass | 2 | ||

|

| |||

| KIDNEY | |||

|

| |||

| Mesoblastic nephroma | 1 | Wilm’s tumors | 9 |

| Renal abscess presenting as mass | 2 | Renal cell carcinoma | 1 (1) |

| Angiomyolipoma | 1 | ||

|

| |||

| ADRENAL | |||

|

| |||

| Ganglioneuroma | 2 | Neuroblastoma | 9 (3) |

| Adrenocortical carcinoma | 1 | ||

|

| |||

| SPLEEN | |||

|

| |||

| Hemangioma | 1 | ||

| Lymphangioma | 1 | ||

|

| |||

| PANCREAS | |||

|

| |||

| Pseudopapillary tumor | 1 | Metastases from neuroblastoma | 1 |

|

| |||

| OVARIAN | |||

|

| |||

| Complex ovarian cyst | 1 | Granulosa Cell Tumor | 2 |

| Dermoid cyst | 1 | Germ cell tumor | 1 (1) |

| Teratoma | 4 (1) | Papillary ovarian carcinoma | 1 (1) |

|

| |||

| OTHER LESIONS | |||

|

| |||

| Aggressive Desmoid fibromatosis | 3 (1) | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 8 (8) |

| Infradiaphragmatic sequestration presenting as abdominal mass | 2 | Sarcoma including Ewing’s and soft tissue sarcoma | 8 (5) |

| Schwannoma | 2 | ||

| Retroperitoneal Phlegmon presenting as mass | 1 | Metastatic lymphadenopathy from neuroblastoma | 1 |

| Cystic lymphatic malformation | 1 | Osteosarcoma | 1 (1) |

| Desmoplastic small round cell tumor | 1 (1) | Lymphoma (including PTLD) | 13 (12) |

| Metastatic sinonasal Carcinoma | 1 | ||

| Nasopharyngeal (NUT) Carcinoma | 1 (1) | ||

In a second step, we selected those patients from the main cohort described above, who had also received an 18F-FDG-PET scan within an interval of 3 weeks or less of their MR scan. Patients who had received interval treatment between the PET and MR were excluded. 36 patients fulfilled the criteria for this subgroup, including 14 males and 22 females with an age of 1–24 years and a mean age of 9.9 years. These patients had 123 tumors, as proven by histopathology and follow up imaging, and as listed in Table1.

Imaging protocols

MRI

MR examinations of the abdomen and/or pelvis had been carried out on clinical 1.5-Tesla (T) (GE Signa HDxt, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) and 3-T (GE Discovery MR750, GE Healthcare) MR scanners. Sequences included axial T2-weighted fast spin-echo (FSE) images with a repetition time (TR) 2,000–11,000 ms at 1.5 T, TR of 6,666–12,500 ms at 3 T, echo time (TE) 67–82 ms, slice thickness 2–4 mm and a field of view (FOV) of 20–32 cm at both field strengths, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences (TR/TE: 5250-7500/54-64ms; b=0, 500), 3D spoiled gradient echo sequences LAVA (liver acquisition with volume acquisition) before and after intravenous injection of 0.1 mmol Gd-BOPTA/kg gadobenate dimeglumine (Gd-BOPTA, MultiHance; Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, NJ), using a TR of 3.8–7.2 ms, a TE of 1.9–7.2 ms, a slice thickness of 2–5 mm, flip angle of 12–15° and a FOV of 24–36 cm.

18F-FDG PET/CT

18F-FDG PET/CT scans had been performed on integrated PET-CT scanners (Biograph 16, Siemens Medical Solutions or Discovery VCT, GE). Blood glucose levels were recorded prior to 18F-FDG injection in all patients. Patients were instructed to fast for at least 6 hours prior to the administration of 18F-FDG to decrease physiologic blood glucose levels and to reduce serum insulin levels to near baseline. Patients were not pre-medicated with muscle relaxants or sedated. 18F-FDG (7.77 MBq/kg of body weight; 0.14 mCi/kg) was injected intravenously 45–60 minutes prior to image acquisition, and patients were asked to void their urine immediately before the PET/CT scan. Oral contrast was not administered. Once patients were positioned in the scanner, Omnipaque 240 or 300 (2.0 ml/kg, the manufacturers recommended dose for children) was injected intravenously at a flow rate of 2.0–3.0 ml/s. PET and low-dose diagnostic CT images (20–120 mAs) from the whole body were obtained in an “arms-up” position with scanning times of approximately 25–45 minutes. In all patients, emission scans were acquired for 3 minutes per bed position in a 3-dimensional mode. The CT data were used for attenuation correction of the PET emission data.

Integration of 18F-FDG PET scans with T2-weighted and post-contrast T1-weighted MR scans

To generate images that integrate anatomical and functional information, we fused 18F-FDG PET scans with T2-weighted FSE images or post-contrast T1-weighted LAVA images, using OsiriX software (version 5.6; 64-bit), an open source DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) Viewer (13). Its fusion function combines the color-shaded 18F-FDG PET scan with corresponding anatomical T2-weighted scans or post-contrast LAVA scans using a transparency mask so that pixels with low signal intensity (SI) values in the color-shaded 18F-FDG PET scan will be completely transparent while high SI pixels will be opaque. An experienced radiologist (VT, 5 years of experience) manually adjusted the image fusions as needed using internal anatomical landmarks, such as outlines of anatomical organs, ribs, vertebrae and pelvic bones.

Standard of reference

In order to validate findings on imaging studies, surgical notes, histopathology reports and imaging follow up for at least twelve months served as the standard of reference.

Image analysis and Statistics

Three experienced radiologists (JT, VT, RG) with 3, 5 and 6 years of experience analyzed the pre- and post-contrast MR images independently. Pre-contrast images comprised T2-FSE, DWI and T1-LAVA sequences and post-contrast images comprised LAVA sequences after intravenous injection of gadolinium chelate. The readers were blinded to histopathology, disease history and other imaging findings. Pre- and post-contrast images were evaluated at least two weeks apart from each other to minimize recall bias. Images were evaluated in regards to 14 different parameters: Image quality/quality of the fused image on a four-point scale (1=poor, 2=satisfactory, 3=good, 4=excellent), organ of origin (primary lesion), tumor solid, cystic or both, homogeneous or inhomogeneous tumor tissue, necrosis yes/no (y/n), tumor margins (well-defined/ill defined), infiltration of adjacent organs (y/n), extensions across midline (y/n), encasement of vessels (y/n), tumor thrombosis (y/n), liver metastases (y/n), bone marrow metastases (y/n), lymph node metastasis (y/n), final diagnosis. Diagnostic criteria for tumor morphology, extent and metastases are listed in Table 2. In the event of multiple primary or metastatic lesions, the readers were asked to give a single overall score for the largest lesion in each target organ. Accuracy was calculated on a per-patient basis at each time point: accuracy for one subject at one time point was scored as 3/3 if all 3 readers agreed with the reference, as 2/3 if 2 readers agreed and one disagreed, as 1/3 if only one of the 3 agreed with the reference, as 0 if none of the readers agreed with the reference. Diagnostic accuracies were calculated for every parameter and a comparison of accuracy measures between the pre- and post-contrast pairs was performed using confidence intervals produced by the bootstrap using the bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap (BCa).

TABLE 2.

Description of various diagnostic criteria used for data analysis

| PARAMETER | Pre-contrast T2, DWI, T1 | Post-contrast T1 + gadolinium chelate | 18FDG PET |

|---|---|---|---|

|

MORPHOLOGY

| |||

| Solid | Restricted diffusion | Tumor enhancement | Increased visual avidity for18FDG* |

| Cystic | Hyperintense on T2 and DWI (T2-shine through) | No contrast enhancement | No central 18FDG avidity; exception: single paraspinal |

| Homogenous | Uniform T2 and DWI signal | Uniform contrast enhancement | N/A |

| Heterogeneous | Varying T2 and DWI signal | Varying contrast enhancement | N/A |

| Presence of necrosis(y/n), areas of decreased/absent contrast enhancement within lesion | Heterogenous/hyperintense on T2 and DWI (T2-shine through) | Decreased or absent areas of contrast enhancement | No 18FDG avidity and fluid noted present on CT or MRI |

| Tumor margins | Well-defined = distinct; Ill-defined = indistinct tumor boundary | N/A since all margins on PETare ill defined | |

|

| |||

|

TUMOR EXTENT

| |||

| Infiltration of adjacent organs (y/n) | Tumor/areas of visualized 18FDG avidity extends beyond organ of origin and infiltrates adjacent structures | ||

| Extension across midline(y/n) | Tumor/18FDG avidity extends beyond contralateral margin of the contralateral vertebral body | ||

| Encasement of vessels (y/n) | Tumor/18FDG avidity surrounding vessel more than 270°. For 18FDG PET, MRI or CT was used for anatomic correlation | ||

| Tumor thrombosis (y/n) | Enlarged vein with altered signal on T2 and DWI | Enlarged vein with focal area of intraluminal enhancement | Focal linear 18FDG uptake within a vein that was either enlarged or in contiguity solid tumoral tissue |

|

| |||

|

METASTASES

| |||

| Solid organ (liver, spleen, kidney and pancreas) (y/n) | Hyperintense on T2 and DWI | Lesions with Gd-enhancement and washout on delayed scans | Obvious 18FDG avidity beyond background visually within the organ* |

| Bone (y/n) | Hyperintense on T2 and DWI | Tumor enhancement | Visual 18FDG avidity either diffusely or focally within lesion* |

| Lymph node (y/n) | Short axis >1cm with loss of normal kidney bean shape | Visual 18FDG avidity within the lymph node despite size* | |

|

| |||

| FINAL DIAGNOSIS | Most appropriate diagnosis based on imaging features | ||

If equivocal, than an ROI was placed within the lesion of concern, mean SUVmax taken and compared to mediastinal blood pool or hepatic background. If the mean SUVmax was greater than 2.5, this was considered concerning for tumoral involvement or metastatic disease.

For the subgroup of 36 patients with integrated 18F-FDG PET/MR scans, a board certified pediatric radiologist and a nuclear medicine physician (VT and DW with both 5 years of experience) compared 18F-FDG PET/T2-FSE and 18F-FDG PET/Gd-LAVA scans regarding the 14 criteria described above. Diagnostic accuracies were calculated as described above for the whole patient group.

In addition, the readers evaluated the concordance or discordance of 18F-FDG PET and gadolinium chelate tumor enhancement in consensus on a lesion-by-lesion and patient-by-patient basis. Concordance was defined as tumors that demonstrated 18F-FDG avidity that also demonstrated gadolinium chelate enhancement in the same location. Discordance was defined as tumors that demonstrated either significant gadolinium chelate enhancement or 18F-FDG avidity but did not have similar areas of 18F-FDG avidity or gadolinium enhancement. Results were collected in a 2x2 table and compared using the McNemar’s Test. Significant differences were assumed for p<0.05.

Results

Comparison of pre- and post-contrast MR sequences

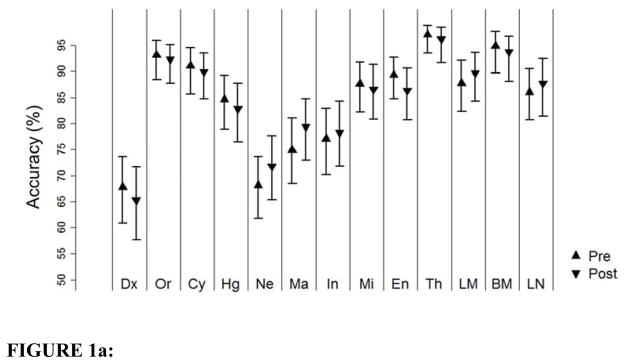

Image quality was rated good to excellent for both pre-contrast MR images and post-contrast images. Pre-contrast MR images received an average score of 3.59 (±0.63) and post-contrast MR images received an average score of 3.63 (± 0.62); these data were not significantly different (p>0.05). Figure 1a shows the mean data of all readers describing 13 criteria on pre-contrast and post-contrast scans in comparison with the standard of reference. The accuracies of the diagnostic criteria, calculated for pre-contrast MR scans and post-contrast MR scans as relative agreement with the standard of reference are depicted in Table 3. There were no significant differences in the diagnostic accuracies for all diagnostic criteria on pre-contrast and post-contrast scans in comparison with the standard of reference. Liver lesions were correctly detected on pre-contrast evaluations in 84.6% cases and on post-contrast evaluations in 85.7% cases, bone marrow lesions in 94.1% compared to 91% and lymph node lesions in 84.9% compared to 84.9% cases (Figure 1a).

FIGURE 1.

FIGURE 1a: Diagnostic Accuracy for 13 assessed categories in 119 patients

Figure 1a shows the diagnostic accuracy plot of the 13 diagnostic criteria evaluated on pre and post contrast MRI images in 119 patients. The abbreviations used in the plot are as follows: Dx: Diagnosis, Or: Organ, Cy: Cyst, Hg: Homogeneous, Ne: Necrosis, Ma: Margins, In: Infiltrates adjacent organs, Mi: extension across midline, En: vascular encasement, Th: tumor thrombosis, LM: Liver metastasis, BM: Bone marrow metastasis, LN: Lymph node

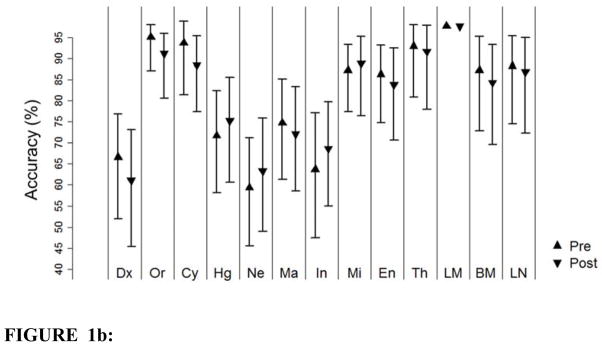

FIGURE 1b: Diagnostic Accuracy for the 13 assessed categories in the subgroup of 36 patients

Figure 1b shows the diagnostic accuracy plot of the 13 diagnostic criteria evaluated on pre and post contrast MRI images in the subgroup of 36 patients. The abbreviations used in the plot are as follows: Dx: Diagnosis, Or: Organ, Cy: Cyst, Hg: Homogeneous, Ne: Necrosis, Ma: Margins, In: Infiltrates adjacent organs, Mi: extension across midline, En: vascular encasement, Th: tumor thrombosis, LM: Liver metastasis, BM: Bone marrow metastasis, LN: Lymph node

Table 3.

Diagnostic accuracies of 13 diagnostic criteria, calculated for pre-contrast MR scans and post-contrast MR scans as relative agreement with the standard of reference (1.00=100%) in 119 patients. The numbers in brackets represent the 95% Confidence intervals. A difference with a confidence interval not straddling zero was considered significant.

| Category | Pre contrast Accuracy | Post contrast Accuracy | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | 0.678(0.608–0.737) | 0.653(0.577–0.720) | 0.025(−0.034–0.076) |

| Organ/Location | 0.924(0.880–0.952) | 0.899(0.849–0.930) | 0.025(−0.011–0.062) |

| Cyst | 0.874(0.815–0.916) | 0.826(0.765–0.871) | 0.048(0.000–0.095) |

| Homogeneity | 0.818(0.756–0.863) | 0.776(0.711–0.829) | 0.042(−0.020–0.092) |

| Necrosis | 0.664(0.602–0.717) | 0.672(0.608–0.728) | −0.008(−0.076–0.050) |

| Definition Margins | 0.725(0.658–0.783) | 0.742(0.675–0.798) | −0.017(−0.076–0.036) |

| Infiltrations | 0.765(0.695–0.821) | 0.751(0.683–0.807) | 0.014(−0.039–0.062) |

| Crossing Midline | 0.866(0.804–0.905) | 0.824(0.756–0.868) | 0.042(0.000–0.087) |

| Vessel Encasement | 0.885(0.835–0.916) | 0.826(0.768–0.868) | 0.059(0.008–0.104) |

| Thrombosis | 0.958(0.916–0.978) | 0.919(0.866–0.947) | 0.039(0.008–0.073) |

| Liver Metastasis | 0.846(0.793–0.885) | 0.857(0.801–0.896 | −0.011(−0.053–0.025) |

| Bone Marrow Metastasis | 0.941(0.890–0.969) | 0.91(0.854–0.944) | 0.031(0.000–0.064) |

| Lymph node Metastasis | 0.849(0.787–0.891) | 0.849(0.784–0.894) | 0(−0.048–0.042) |

Comparisons of 18F-FDG and gadolinium chelate tumor enhancement

Image quality was rated good to excellent for both 18F-FDG PET/T2-FSE and 18F-FDG PET/Gd-LAVA scans. 18F-FDG PET/T2-FS images received an average score of 3.6 (+/− 0.43) and 18F-FDG PET/Gd-LAVA scans received an average score of 3.7 (+/− 0.31); these data were not significantly different (p>0.05). The diagnostic accuracies for the 13 diagnostic criteria were not significantly different between 18F-FDG PET/T2-FSE and 18F-FDG PET/Gd-LAVA (p<0.05) (Table 4, Figure 1b).

Table 4.

Diagnostic accuracies of 13 diagnostic criteria, calculated for pre-contrast MR scans and post-contrast MR scans as relative agreement with the standard of reference (1.00=100%) in the subgroup of 36 patients. The numbers in brackets represent the 95% Confidence intervals. A difference with a confidence interval not straddling zero was considered significant.

| Category | Pre contrast Accuracy | Post contrast Accuracy | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | 0.667 (0.519–0.778) | 0.611(0.454–0.731) | 0.056(−0.074–0.157) |

| Organ/Location | 0.926 (0.833–0.963) | 0.87(0.741–0.935) | 0.056(−0.028–0.148) |

| Cyst | 0.843(0.694–0.778) | 0.75(0.602–0.852) | 0.093(−0.019–0.204) |

| Homogeneity | 0.667(0.528–0.778) | 0.685(0.546–0.796) | −0.019(−0.167–0.093) |

| Necrosis | 0.556(0.426–0.667) | 0.565(0.417–0.676) | −0.009(−0.139--0.139) |

| Definition Margins | 0.713(0.574–0.806) | 0.667(0.519–0.778) | 0.046(−0.065–0.148) |

| Infiltrations | 0.63(0.472–0.472) | 0.657(0.519–0.759) | −0.028(−0.148–0.083) |

| Crossing Midline | 0.852(0.750–0.907) | 0.833(0.685–0.907) | 0.019(−0.065–0.111) |

| Vessel Encasement | 0.843(0.728–0.907) | 0.787(0.648–0.870) | 0.056(−0.056–0.157) |

| Thrombosis | 0.898(0.787–0.954) | 0.861(0.722–0.935) | 0.037(−0.046–0.120) |

| Liver Metastasis | 0.852(0.769–0.898) | 0.917(0.796–0.963) | −0.065(−0.148–0.019) |

| Bone Marrow Metastasis | 0.852(0.704–0.926) | 0.806(0.648–0.898) | 0.046(−0.028–0.130) |

| Lymph node Metastasis | 0.843(0.694–0.926) | 0.824(0.676–0.917) | 0.019(−0.120–0.139) |

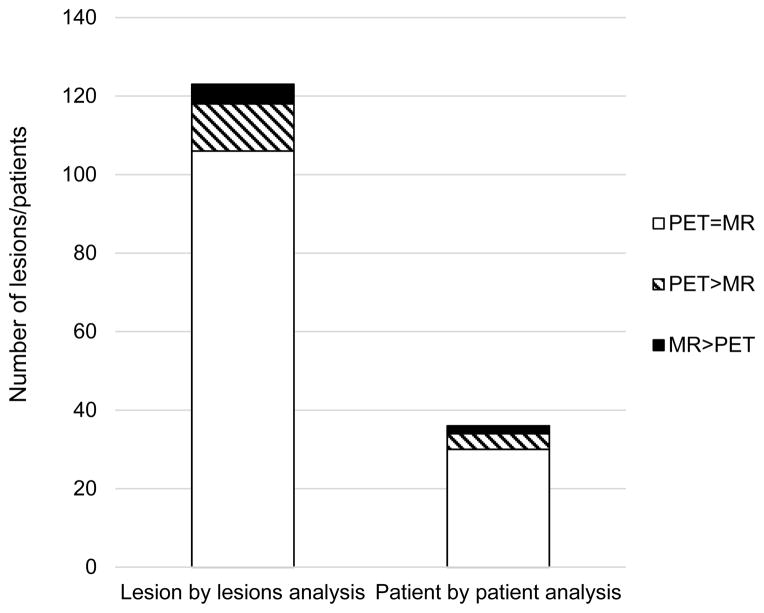

Lesion-by-lesion analyses revealed concordant 18F-FDG and gadolinium chelate tumor enhancement for 106 of 123 tumors (86%) and discordant enhancement for 17 of 123 tumors (14%). When evaluated on a patient-by-patient basis, 30 of 36 patients demonstrated concordant 18F-FDG and gadolinium chelate enhancement of all tumors and 6 of 36 patients demonstrated discordant 18F-FDG and gadolinium enhancement of at least one tumor. These differences between gadolinium enhancement and 18F-FDG avidity were not significantly different (p>0.05) (Figure 2,4,5).

FIGURE 2. Concordancy of gadolinium chelate enhancement and 18F-FDG PET avidity.

Bar graph showing (a) the outcome of the lesion-by-lesion analysis of 123 tumors in the subgroup of 36 patients and (b) the outcome of the patient-by-patient analysis in this subgroup (a): PET=MR 106/123, PET>MR 12/123, MR>PET 5/123; b): PET=MR 30/36, PET>MR 4/36, MR>PET 2/36).

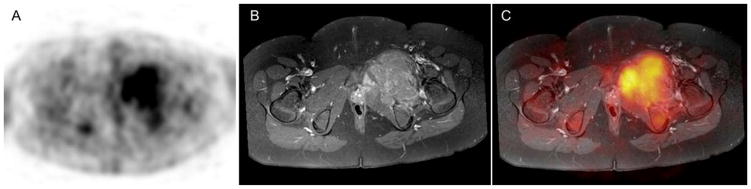

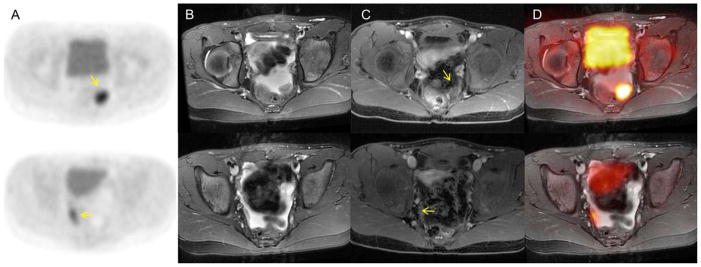

FIGURE 4. Concordance in 18F-FDG PET avidity and gadolinium chelate enhancement.

11-year-old boy with Ewing’s sarcoma of the left pelvis at his initial staging exam. (a) Axial 18F-FDG PET image. (b) Axial T1 MRI after administration of gadolinium chelate. (c) The fused image of the axial 18F-FDG PET and the axial T1 MRI shows concordance in 18F-FDG PET avidity and gadolinium chelate enhancement.

FIGURE 5. Concordance in 18F-FDG PET avidity and gadolinium chelate enhancement.

10 year old female with a history of an immature teratoma, status post resection: a), b) 18F-FDG PET scan demonstrates two foci with marked glucose hypermetabolism in the left and right lower pelvis (yellow arrows). c), d) T2 MR demonstrates that these correspond to two small soft tissue nodules outlined by pelvic fluid. e), f) T1 post contrast MR demonstrates these nodules enhance (yellow arrows). g), h) Fused T2 PET/MR demonstrates the nodules amidst pelvic fluid.

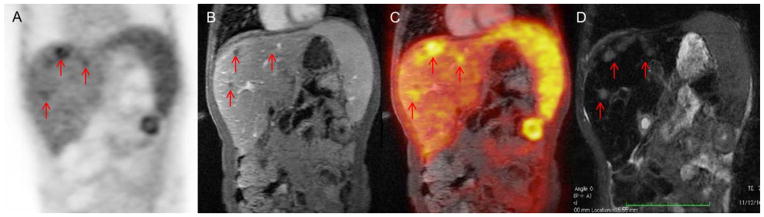

Discordant findings were as follows: Three patients with malignant sarcomas demonstrated a “mismatch” of a larger area of gadolinium chelate contrast enhancement around a “core” of FDG-avidity. Two calcified metastases of a malignant germ cell tumor and a case of renal post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) showed marked 18F-FDG-uptake, but little or no gadolinium chelate enhancement. Six hepatic metastases of a germ cell tumor appeared hypointense during all phases after gadolinium chelate injection, yet showed marked 18F-FDG avidity (Figure 6). These lesions were calcified on CT scans. We only found one false negative lesion on 18F-FDG PET: epidural disease in a patient with lymphoma, which was clearly noted on gadolinium enhanced MRI, but not detected on 18F-FDG PET, possibly due to the lower spatial resolution of the PET scan compared to the MRI.

FIGURE 6. Disconcordant FDG avidity and gadolinium chelate enhancement.

10 year old boy with treated metastasis of a desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a) 18F-FDG PET, b) Post contrast T1-weighted MR, c) Fused 18F-FDG PET/MRT1, d) T2 MR; There are multiple hepatic metastases (red arrows) which are FDG-avid, but apparently do not enhance.

Discussion

Our data showed no significant difference in diagnostic accuracies of gadolinium-enhanced and unenhanced MR scans as well as gadolinium chelate enhanced and unenhanced integrated 18F-FDG-PET/MR scans for staging of pediatric tumors. We found a high concordance of 18F-FDG and gadolinium chelate tumor enhancement. We conclude that MR contrast media administration may not be necessary for integrated 18F-FDG-PET/MR scans. Several previous investigators reported a superiority of T1-weighted fat-suppressed contrast-enhanced sequences compared to unenhanced sequences for tumor diagnosis in most of organs systems e.g. the spine (14) the kidney (15) or head and neck masses (16). Contrast enhanced imaging improved lesion detection, tissue characterization, and determination of tumor extent. However, advances in MR technology as well as improved soft tissue contrast and anatomical resolution on high field MR scanners give rise to the question if the administration of contrast agents is actually always needed. Tokuda and colleagues recently reported comparable results for differentiation of benign from malignant tumors in soft tissue masses (17) and even better results for differentiation of benign from malignant bone tumors by using fast short tau inversion recover (STIR) imaging (18) suggesting that contrast enhancement is not always needed. In addition diffusion weighted MR imaging provides information about solid and cystic/necrotic tumor areas, which was previously only accessible with contrast-enhanced sequences (19). DW-MRI was also superior for detection of small peritoneal and serosal metastases, which were difficult to detect on gadolinium chelate enhanced images (20), it showed better contrast between tumors and bowel contents compared to gadolinium chelate enhanced images (20) and it demonstrated equivalent results when compared to 18F-FDG PET-CT in patients with lymphoma (11). In accordance with these studies, we found similar diagnostic accuracies of T2 and diffusion weighted scans for local tumor staging compared to gadolinium chelate enhanced MR images.

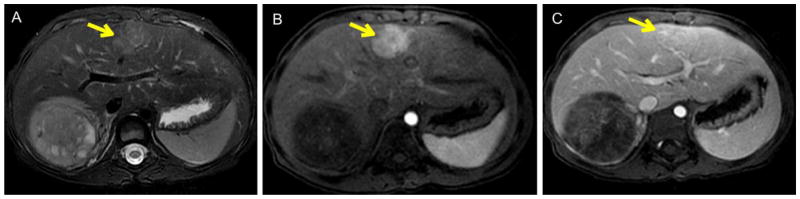

Our study and others found that Diffusion Weighted-MRI and T2-MRI has limitations in the characterization of focal liver lesions (Figure 3) (21). We therefore suggest that the administration of gadolinium chelates may only be necessary if equivocal liver lesions are identified on a pre-contrast scan check. This could be especially useful for example in the differentiation between focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH)/adenomas and hepatoblastomas or metastases, which often requires a two-step approach with more specific contrast agents such as Gd-DTPA-EOB (Gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid) (22, 23). In such cases, obtaining unenhanced sequences would enable the examiner to add more specific contrast agents in the same session and thus might actually be of advantage.

FIGURE 3. Comparison of T2 MR and T1 MR post contrast enhanced MRI scans.

Figure 3a shows a patient with wilms tumor of the right kidney and a T2 bright lesion in the right lobe of the liver concerning for metastases on the pre contrast T2 weighted images (yellow arrow). However, the post contrast images show early arterial enhancement (Fig. 3b, yellow arrow) with persistent retention of contrast on the delayed images in a central scar consistent with a focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH, Fig. 3c, yellow arrow).

Our data also showed that integrated 18F-FDG PET-MR does not require gadolinium chelate enhanced sequences for local tumor staging. Considering the risk of nephrogenic sclerosis (24, 25) and recently reported gadolinium chelate deposition in the brain (26, 27), in addition to costs and added examination time for contrast-enhanced sequences, there would be a major benefit from eliminating gadolinium-chelate administration and streamlining of pediatric PET/MR studies. Growing cancers are characterized by angiogenesis (28) and glucose metabolism (29). Previous studies have shown that gadolinium chelate enhanced sequences can detect vascularized tumor tissue (30). However, Kuhn et al. described an improved morphologic characterization of PET-positive primary tumors on T2w PET/MR imaging compared to contrast enhanced PET/CT (31). Zasadny and colleges reported a strong correlation between 18F-FDG uptake and tumor blood flow in women with untreated breast cancers (32). Similarly Armbruster et al. found a positive correlation between the arterial flow fraction and SUV (Standardized Uptake Value) of liver metastases of neuroendocrine tumors, suggesting a link between arterial tumor perfusion and metabolic activity (33). However, it is important to note that tumor blood flow is assessed on a first pass 2min post contrast scan while tumor 18F-FDG metabolism is assessed at 30–60min post contrast scans (34). In our study, 17 out of 123 tumors demonstrated “mismatched” tumor areas, where gadolinium chelate enhancement and 18F-FDG PET did not corroborate with one another (Figure 6). Two of these tumors were sarcomas, which have a known marked heterogeneity (35). Other “mismatches” included FDG positive tumors, which did not show gadolinium enhancement due to calcifications (germ cell tumors), or relatively low blood volume (PTLD) and false negative results due to low PET resolution (Lymphoma).

We acknowledge several limitations to our study. Our patient population that received serial 18F-FDG PET and MR scans is limited by a relatively small size of 36 patients, although this is the largest number of pediatric fused serial MRI and 18F-FDG PET scans described to date. The heterogeneity of tumor types included in our study reflects the typical pediatric imaging practice at our institution. Yet because of this variety conclusions maybe overgeneralized at the same time. We did not obtain simultaneous 18F-FDG PET/MR scans but rather fused serial MR and 18F-FDG PET scans. Image registration is important for this approach. We utilized the well-established image processing package Osirix, which has an image registration application that allows MR image registration within less than 500 microns. In few patients, we included markers on the skin to facilitate this process and found excellent co-registration of our approach. Moreover, even simultaneous PET/MR currently still has some limitations in comparison with PET/CT (36). Not all of the MR studies used for fused PET/MR scans were conducted on the 3T system. However there is currently no evidence suggesting that standard sequences on 3T and 1.5T systems provide different diagnostic accuracies for the diagnosis of pediatric tumors (37). Our study only included one malignant lesion with sub-centimeter size, which was below the anatomical resolution of PET. Results may have been less favorable for 18F-FDG PET if more sub-centimeter lesions had been included. However, tumors in pediatric patients are typically large and sub-centimeter lesions a rare in clinical practice.

Conclusion

In summary, 18F-FDG PET scans of pediatric tumors of the abdomen and/or pelvis can be integrated with either T2-weighted MR scans or contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR scans. There is high concordance of 18F-FDG and gadolinium chelate contrast enhancement in these tumors. If gadolinium chelate administration does not provide additional information compared to 18F-FDG-PET scans, MR scans for local staging could be streamlined and gadolinium chelates could be replaced by alternative, more specific MR contrast agents.

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: Child Health Research Institute, Stanford University

We thank Dr. Ying Chen for her valuable input regarding the statistical analysis. We thank Dr. David Weinreb and Dr. Bo Yoon Ha for their help with image analysis. We thank Prof. Sandy Napel for his valuable input regarding image processing.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- MR

Magnetic Resonance

- CT, Computer Tomography18F-FDG

18F-Flurodeoxyglucose

- 18F-FDG PET/MR

integrated 18F-FDG PET and MR

- SUV

Standardized uptake value

- LAVA

Liver acquisition with volume acquisition

- CNS

Central nervous system

- NHL

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

- FNH

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

- Gd-DTPA-EOB

Gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid

- FSE

Fast Spin Echo

- DWI

Diffusion-Weighted Imaging

- DW-MRI

Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- STIR

Short Tau Inversion Recovery

- FOV

Field of View

Footnotes

Disclosure:

The authors acknowledge support from the Child Health Research Institute, Stanford University and the NICHD (R01 HD081123-01A1). There are no other relevant relationships that could be perceived as a real or apparent conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ley S, Ley-Zaporozhan J, Gunther P, Deubzer HE, Witt O, Schenk JP. Neuroblastoma imaging. Rofo. 2011;183:217–225. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1245903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel MJ, Chung EM. Wilms' tumor and other pediatric renal masses. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2008;16:479–497. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kremer N, Walther AE, Tiao GM. Management of hepatoblastoma: an update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2014;26:362–369. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JM, Yoon JH, Joo I, Woo HS. Recent Advances in CT and MR Imaging for Evaluation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2012;1:22–40. doi: 10.1159/000339018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brisse H, Ollivier L, Edeline V, et al. Imaging of malignant tumours of the long bones in children: monitoring response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and preoperative assessment. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:595–605. doi: 10.1007/s00247-004-1192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cha S. Neuroimaging in neuro-oncology. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6:465–477. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iagaru A, Quon A, McDougall IR, Gambhir SS. F-18 FDG PET/CT evaluation of osseous and soft tissue sarcomas. Clin Nucl Med. 2006;31:754–760. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000246846.01492.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwee TC, van Ufford HM, Beek FJ, et al. Whole-body MRI, including diffusion-weighted imaging, for the initial staging of malignant lymphoma: comparison to computed tomography. Invest Radiol. 2009;44:683–690. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181afbb36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catalano OA, Rosen BR, Sahani DV, et al. Clinical impact of PET/MR imaging in patients with cancer undergoing same-day PET/CT: initial experience in 134 patients--a hypothesis-generating exploratory study. Radiology. 2013;269:857–869. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirsch FW, Sattler B, Sorge I, et al. PET/MR in children. Initial clinical experience in paediatric oncology using an integrated PET/MR scanner. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43:860–875. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2570-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klenk C, Gawande R, Uslu L, et al. Ionising radiation-free whole-body MRI versus (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT scans for children and young adults with cancer: a prospective, non-randomised, single-centre study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:275–285. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70021-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daldrup-Link HE, Golovko D, Ruffell B, et al. MRI of tumor-associated macrophages with clinically applicable iron oxide nanoparticles. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5695–5704. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosset A, Spadola L, Ratib O. OsiriX: an open-source software for navigating in multidimensional DICOM images. J Digit Imaging. 2004;17:205–216. doi: 10.1007/s10278-004-1014-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tien RD, Olson EM, Zee CS. Diseases of the lumbar spine: findings on fat-suppression MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:95–99. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.1.1609731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Semelka RC, Hricak H, Stevens SK, Finegold R, Tomei E, Carroll PR. Combined gadolinium-enhanced and fat-saturation MR imaging of renal masses. Radiology. 1991;178:803–809. doi: 10.1148/radiology.178.3.1994422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barakos JA, Dillon WP, Chew WM. Orbit, skull base, and pharynx: contrast-enhanced fat suppression MR imaging. Radiology. 1991;179:191–198. doi: 10.1148/radiology.179.1.2006277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tokuda O, Harada Y, Matsunaga N. MRI of soft-tissue tumors: fast STIR sequence as substitute for T1-weighted fat-suppressed contrast-enhanced spin-echo sequence. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1607–1614. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tokuda O, Hayashi N, Matsunaga N. MRI of bone tumors: Fast STIR imaging as a substitute for T1-weighted contrast-enhanced fat-suppressed spin-echo imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;19:475–481. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eberhardt SC, Johnson JA, Parsons RB. Oncology imaging in the abdomen and pelvis: where cancer hides. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:647–671. doi: 10.1007/s00261-012-9941-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Low RN, Gurney J. Diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI) in the oncology patient: value of breathhold DWI compared to unenhanced and gadolinium-enhanced MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25:848–858. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park MS, Kim S, Patel J, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: detection with diffusion-weighted versus contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in pretransplant patients. Hepatology. 2012;56:140–148. doi: 10.1002/hep.25681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Beers BE, Pastor CM, Hussain HK. Primovist, Eovist: what to expect? J Hepatol. 2012;57:421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jhaveri K, Cleary S, Audet P, et al. Consensus statements from a multidisciplinary expert panel on the utilization and application of a liver-specific MRI contrast agent (gadoxetic acid) AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:498–509. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.12399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinreb JC, Kuo PH. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2009;17:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weller A, Barber JL, Olsen OE. Gadolinium and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: an update. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29:1927–1937. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2636-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karabulut N. Gadolinium deposition in the brain: another concern regarding gadolinium-based contrast agents. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2015;21:269–270. doi: 10.5152/dir.2015.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Kallmes DF, et al. Intracranial Gadolinium Deposition after Contrast-enhanced MR Imaging. Radiology. 2015;275:772–782. doi: 10.1148/radiol.15150025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Folkman J. Seminars in Medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. Clinical applications of research on angiogenesis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1757–1763. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merida I, Avila-Flores A. Tumor metabolism: new opportunities for cancer therapy. Clin Transl Oncol. 2006;8:711–716. doi: 10.1007/s12094-006-0117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuncbilek N, Kaplan M, Altaner S, et al. Value of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and correlation with tumor angiogenesis in bladder cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:949–955. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuhn FP, Hullner M, Mader CE, et al. Contrast-Enhanced PET/MR Imaging Versus Contrast-Enhanced PET/CT in Head and Neck Cancer: How Much MR Information Is Needed? J Nucl Med. 2014;55:551–558. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.125443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zasadny KR, Tatsumi M, Wahl RL. FDG metabolism and uptake versus blood flow in women with untreated primary breast cancers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:274–280. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-1022-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armbruster M, Sourbron S, Haug A, et al. Evaluation of neuroendocrine liver metastases: a comparison of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Invest Radiol. 2014;49:7–14. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3182a4eb4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mullani NA, Herbst RS, O'Neil RG, Gould KL, Barron BJ, Abbruzzese JL. Tumor blood flow measured by PET dynamic imaging of first-pass 18F-FDG uptake: a comparison with 15O-labeled water-measured blood flow. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:517–523. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.048504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bestic JM, Peterson JJ, Bancroft LW. Pediatric FDG PET/CT: Physiologic uptake, normal variants, and benign conditions [corrected] Radiographics. 2009;29:1487–1500. doi: 10.1148/rg.295095024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bezrukov I, Schmidt H, Gatidis S, et al. Quantitative Evaluation of Segmentation- and Atlas-Based Attenuation Correction for PET/MR on Pediatric Patients. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1067–1074. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.149476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wardlaw JM, Brindle W, Casado AM, et al. A systematic review of the utility of 1.5 versus 3 Tesla magnetic resonance brain imaging in clinical practice and research. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:2295–2303. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2500-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]