Abstract

Two kinds of peony roots—white peony root (WPR) and red peony root (RPR)—are used for different remedies in traditional Chinese medicine; however, most of them are derived from the same botanical origin, Paeonia lactiflora. The difference between WPR and RPR has been debated for a long time. This study attempted to clarify the genetic and chemical characteristics of WPR and RPR in order to provide a scientific dataset for their identification and effective use. The nucleotide sequence of nrDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and the contents of 8 main bioactive constituents were analyzed from specimens of P. lactiflora, P. veitchii and two related species as well as crude drug samples of WPR, RPR and peony root produced in Japan. Of the samples derived from P. lactiflora, the WPR produced in the southern parts of China and the RPR produced in the northern parts of China were clearly divided into two subgroups within the P. lactiflora group based on similarity of the ITS sequences. The nucleotides at positions 69, 458 and 523 upstream of the ITS sequence served as molecular markers to discriminate between WPR and RPR. Quantitative analysis indicated that the RPR samples obviously contained a higher content of paeoniflorin and paeonol, but a lower content of albiflorin than the WPR produced in the southern parts of China and peony root produced in Japan. The WPR available from Chinese markets was usually processed by sulfur fumigation, which resulted in an extremely low content of paeoniflorin. This study indicated that WPR and RPR were not only geographically isolated, but also genetically and chemically separated. The ITS sequence provided a genetic index for their identification.

Keywords: Paeonia lactiflora, White peony root, Red peony root, Internal transcribed spacer of nrDNA (ITS) sequence, Chemical composition, Paeoniflorin, Pentagalloylglucose

Introduction

Peony root (PR) (Paeoniae Radix) is one of the most frequently used crude drugs in traditional Chinese medicine and Kampo medicine. In China there are two kinds of PR available—white peony root (WPR) and red peony root (RPR)—which are used for different remedies. WPR has been used to treat symptoms such as dizziness, limb spasm, abdominal pain, diarrhea, blood deficiency and irregular menses, etc. RPR, however, has been mainly used as remedies for blood stasis, gynecological diseases, cardiovascular illness, etc. [1]. In Chinese Pharmacopoeia, WPR is prescribed as the root of Paeonia lactiflora Pallas, which has been boiled and peeled and RPR is prescribed as the naturally dried root of P. lactiflora and P. veitchii Lynch. With the exception of P. veitchii-derived RPR, the WPR and RPR are from the same botanical origin, P. lactiflora. The difference between WPR and RPR has been debated for a long time with regard to the processing methods (peeled or unpeeled), difference in flower colors or root colors, and cultivated or wild, etc. [2]. The most recent Pharmacognosy textbook describes that WPR is derived from cultivated sources mainly produced in Anhui, Zhejiang, and Sichuan provinces of southern China, whereas RPR is derived from wild plants collected from Inner Mongolia and northeastern China [3]. It is interesting to explore the underlying differences between these two crude drugs. It is also an appealing yet difficult task in terms of how to accurately discriminate between them. In this study, we attempted to find the answers using genetic and chemical approaches.

In the Japanese Pharmacopoeia, PR is prescribed as the root of P. lactiflora with not less than 2.0 % paeoniflorin [4]. As an analgesic, antispasmodic, astringent, etc., it has been included in approximately one-third of Kampo formulas used in Japan [5]. Hereafter, PR refers limitedly to the crude drugs of the roots of P. lactiflora available from Japanese markets. PR is supplied mainly by import from China and partly by domestic production, e.g., 1,188 tons was imported in 2010 and the domestic supply was 38 tons [6]. Apart from the different processing methods, PR and WPR are considered to be almost the same crude drug, because both are derived from the cultivated P. lactiflora. Generally, the PR samples imported from China are produced in the same producing areas of WPR.

To date, genetic markers used in phylogenetic analysis of Paeonia species include nucleotide sequences of the ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, Adh1/2 genes and GPAT gene of nDNA, as well as matK gene, intergenic spacer trnL-F and psbA–trnH of cpDNA [7–10]. Among them, the ITS sequence has been demonstrated to be powerful for phylogenetic resolution and for discrimination between species due to the high rate of variation [11, 12]. Moreover, ITS sequencing of Paeonia species provides the most successful example of using the ITS sequence to reconstruct reticulate evolution; the nucleotide additivity is highly informative for detecting hybridization and inferring parental lineages [7]. Phytochemical studies have indicated that Paeonia plants contain many bioactive components, including monoterpenes, flavonoids, phenols and tannins [13]. Several reports have described quantitative analyses of the main chemical components of commercial samples of WPR and RPR [14, 15].

The present study determined the nucleotide sequence of the ITS region and conducted quantitative analysis of 8 main bioactive components on 4 Paeonia species, as well as commercial samples of PR, WPR and RPR collected from Japanese and Chinese markets to clarify the genetic and chemical characteristics of WPR and RPR.

Materials and methods

Plant and crude drug materials

Fourteen specimens of four Paeonia species were analyzed—P. lactiflora, P. veitchii, P. anomala Linn. and P. japonica Miyabe et Takeda. Details of the plant materials are shown in Table 1. Meanwhile, 46 commercial samples available from Chinese and Japanese markets were collected and analyzed for comparison. Of the PR samples collected from Japanese markets, half were imported from China and half were produced in Japan. In several commercial samples, multiple individuals were analyzed and their identities were indicated separately. All of the plant specimens and crude drug samples were stored in the Museum of Materia Medica, Institute of Natural Medicine, University of Toyama, Japan (TMPW) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Plant specimens used in this study

| Original plant | Location for collecting plant | W/C | Voucher no. | Code no. | Collection date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paeonia lactiflora Pallas | Duolun, Inner Mongolia, China | W | Wei S.L., 2007-1 | P1a | 2007.01.28 |

| P. lactiflora | Arxan, Inner Mongolia, China | W | Murakami M. MM-1 | P2 | 2007.08.11 |

| P. lactiflora | Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, China | W | Komatsu K. et al., HJN269 | P14 | 2012.08.04 |

| P. lactiflora | Wudalianchi, Heilongjiang, China | W | Komatsu K. et al., HJN143 | P15 | 2012.07.22 |

| P. lactiflora | Wudalianchi, Heilongjiang, China | W | Komatsu K. et al., HJN145 | P16 | 2012.07.22 |

| P. lactiflora | Mongolia | W | 623-63 | P3 | 1967 |

| P. lactiflora | Xinwo, Zhejiang, China | C | Komatsu K. et al., CJZ132 | P9a | 2009.08.05 |

| P. lactiflora (Bonten) | Toyama, Japan | C | Murakami M., S34 | S34a | 2008.11. |

| P. lactiflora (Kitasaisho) | Toyama, Japan | C | Murakami M., S31 | S31a | 2008.11. |

| P. anomala Linn. | Tuluugiyn davas-Hutag-Ondor, Bulgan, Mongolia | W | Komatsu K. et al., M505 | P4a | 2002.07.20 |

| P. anomala | Jingiin halzan-Bayannuul, Uvs, Mongolia | W | Komatsu K. et al., M755-1 | P5a | 2002.07.29 |

| P. anomala | Mongolia | W | Komatsu K. et al., M755-2 | P6a | 2002.07.29 |

| P. veitchii Lynch | Ganzi, Sichuan, China | W | Komatsu K. et al., S-1 | P7a | 1996.07.10 |

| P. japonica Miyabe et Takeda | Toyama, Japan | C | Murakami M., MM-4 | P8 | 2008.12.04 |

W, wild; C, cultivated

aSamples used in chemical analysis

Table 2.

Crude drug samples used in this study

| Drug name | Abr. | Production area | Obtained from | Code no. | Collection date | TMPW no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White peony root | WPR | Bozhou, Anhui, China | Bozhou, Anhui, China | D1a | 2006.05.02 | 25071 |

| White peony root | WPR | Bozhou, Anhui, China | Bozhou, Anhui, China | D2a | 2006.05.02 | 25072 |

| White peony root | WPR | Bozhou, Anhui, China | Bozhou, Anhui, China | D3a | 2006.10.17 | 25244 |

| White peony root | WPR | Bozhou, Anhui, China | Bozhou, Anhui, China | D17a | 2006.05.02 | 25073 |

| White peony root | WPR | Anhui, China | Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China | D23 a | 2010.10.14 | 26975 |

| White peony root | WPR | Zhongjiang, Sichuan, China | Jihuang, Zhongjiang, Sichuan, China | D4a | 2002.09.23 | 25820 |

| White peony root | WPR | Zhejiang, China | Cenxi, Guangxi, China | D18a | 2008.09.06 | 25973 |

| White peony root | WPR | Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China | Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China | D22a | 2010.10.13 | 26974 |

| White peony root | WPR | Pan’an, Zhejiang, China | Pan’an, Zhejiang, China | D29a | 2009.08.05 | 26620 |

| White peony root | WPR | Jiangsu, China | Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China | D24a | 2010.10.16 | 26976 |

| Peony root | PR | Anhui, China | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D30 | 2010 | 27685 |

| Peony root | PR | Anhui, China | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D31 | 2009 | 27689 |

| Peony root | PR | Anhui, China | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D32 | 2008 | 27690 |

| Peony root | PR | Anhui, China | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D33 | 2008 | 27691 |

| Peony root | PR | Anhui, China | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D34 | 2009 | 27693 |

| Peony root | PR | Anhui, China | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D35 | 2010 | 27696 |

| Peony root | PR | Anhui, China | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D36 | 2009 | 27697 |

| Peony root | PR | Zhejiang, China | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D37 | 2010 | 27686 |

| Peony root | PR | Sichuan, China | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D38 | 2009 | 27687 |

| Peony root | PR | Sichuan, China | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D39 | 2009 | 27692 |

| Peony root | PR | Sichuan, China | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D40 | Unknown | 27699 |

| Peony root | PR | Zhejiang, China | Tochimoto Tenkaido Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan | D45 a | 2012.09.04 | 27887 |

| Peony root | PR | Sichuan, China | Tochimoto Tenkaido Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan | D46 a | 2012.09.04 | 27888 |

| Peony root | PR | Anhui, China | Tochimoto Tenkaido Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan | D47 a | 2012.09.04 | 27889 |

| Peony root | PR | China | Uchida Wakanyaku Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan | D48 a | 2012.09.04 | 27890 |

| Peony root | PR | China | Matsuura Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan | D53a | 2012.10.04 | 27892 |

| Peony root (Bonten) | PR | Toyama, Japan | Nara, Japan | D50a | 2008.02.15 | 25834 |

| Peony root (Bonten) | PR | Toyama, Japan | Nara, Japan | D51a | 2008.02.15 | 25835 |

| Peony root (Bonten) | PR | Toyama, Japan | Nara, Japan | D52a | 2008.02.15 | 25836 |

| Peony root | PR | Niigata, Japan | Uchida Wakanyaku Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan | D6 a | 2008.10.07 | 26400 |

| Peony root (Yamato) | PR | Nara, Japan | Tochimoto Tenkaido Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan | D7a | 2008.02.14 | 25818 |

| Peony root (Yamato) | PR | Hokkaido and Nagano, Japan | Tochimoto Tenkaido Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan | D8a | 2008.02.14 | 25819 |

| Peony root (Yamato) | PR | Nara, Japan | Tochimoto Tenkaido Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan | D9a | 2008.10.31 | 26107 |

| Peony root (Yamato) | PR | Nara, Japan | Tochimoto Tenkaido Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan | D10a | 2008.10.31 | 26398 |

| Peony root | PR | Nagano, Japan | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D41 | 2009 | 27688 |

| Peony root | PR | Nara, Japan | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D42 | 2010 | 27694 |

| Peony root | PR | Niigata, Japan | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D43 | 2010 | 27695 |

| Peony root | PR | Nara, Japan | National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan | D44 | 2010 | 27698 |

| Peony root | PR | Japan | Uchida Wakanyaku Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan | D49a | 2012.09.04 | 27891 |

| Red peony root | RPR | Sichuan, China | Cenxi, Guangxi, China | D16a | 2008.09.06 | 25974 |

| Red peony root | RPR | Inner Mongolia, China | Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, China | D12a | 2002.09.14 | 21565 |

| Red peony root | RPR | Inner Mongolia, China | Bozhou, Anhui, China | D13a | 2006.05.01 | 25047 |

| Red peony root | RPR | China | Uchida Wakanyaku Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan | D14 a | 2008.10.07 | 26401 |

| Red peony root | RPR | Inner Mongolia, China | Tochimoto Tenkaido Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan | D15a | 2008.10.16 | 26406 |

| Red peony root | RPR | China | Matsuura Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan | D54a | 2012.10.04 | 27893 |

| Red peony rootb | RPRb | Ganzi, Sichuan, China | Ganzi, Sichuan, China | D11a | 1996.07.11 | 17304 |

aSamples used in chemical analysis; italicized number: multiple individuals in the sample were analyzed

bThis sample is derived from P. veitchii; apart from this sample the others are derived from P. lactiflora based on sequence analysis results

Genomic DNA extraction and PCR amplification

Total DNA was extracted from 50 − 60 mg of root powder by using DNeasy™ Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) with little modification to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The primer pair used for PCR amplification were ITS-1F (5′-GTA GGT GAA CCT GCA GAA GGA TCA-3′) and 18S-25S-3′R (5′-CCA TGC TTA AAC TCA GCG GGT-3′) as reported previously [16], which was able to amplify a fragment of approximately 700 bp including the rDNA ITS1–5.8S–ITS2 regions. PCR amplification was performed in 25 µl of reaction mixture, consisting of 1 × PCR buffer for KOD-Plus-, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1.0 mM MgSO4, 0.3 μM of each primer, 0.5 U KOD-Plus- DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Japan), and 0.5 µl of total DNA. PCR amplification was performed under the cycling profile of a preliminary denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 50 s, and a final extension at 68 °C for 10 min by a Takara thermal cycler (Takara, Japan). PCR products were purified with a WizardSV PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, USA).

Sequence analysis and clustering analysis

Sequencing reaction of purified PCR products was carried out separately using ABI PRISM Bigdye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kits (Applied Biosystems, USA) with each of the 4 types of primers (ITS-1F, 18S-25S-3′R, In-18S-25S-5′F: 5′-TCT CGC ATC GAT GAA GAA CG-3′ and In-18S-25S-3′R: 5′-GAC TCG ATG GTT CAC GGG ATT CT-3′). The sequence was determined directly using ABI Prism 3100-Avant Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA). With regard to the judgment of additive sites, we calculated the relative intensity of the lower peak as S value (lower peak intensity/sum of main peak intensity and lower peak intensity) for the sites where double peaks occurred. The sites with an S value no less than 15 % were recorded as additive sites, according to our previous results from experimental examinations [17, 18]. The borders of ITS1, 5.8S, and ITS2 regions were determined by comparison with the known sequences of mung bean and rice [19, 20]. The nucleotides sequence data of the ITS1–5.8S–ITS2 regions were deposited in the International Nucleotide Sequence Database (INSD: DDBJ/EMBI/NCBI) with the accession numbers shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

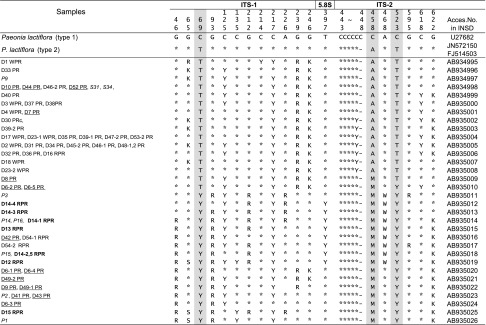

Comparison of ITS sequences among various samples derived from Paeonia lactiflora

K = G&T; M = A&C; R = A&G; S = C&G; W = A&T; Y = C&T

Italic numbers, plant materials; bold faced number, RPR produced in China; underlined numbers, PR produced in Japan

Comparison of ITS sequences was carried out by the ClastalW2 program for multiple sequence alignment. A guide tree on the basis of sequence similarity was constructed during multiple sequence alignment (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/). Besides the sequences determined in the present study, ITS sequences of related Paeonia species obtained from INSD were also included.

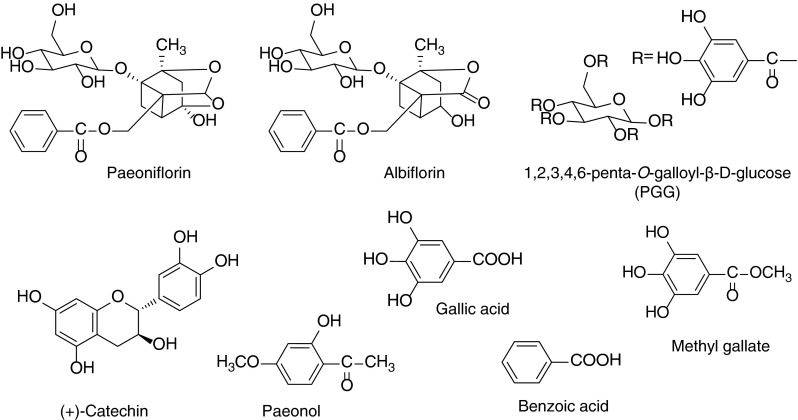

HPLC analysis of 8 main components

Quantitative analysis of 8 main components (paeoniflorin, albiflorin, pentagalloylglucose [PGG], (+)-catechin, gallic acid, methyl gallate, benzoic acid and paeonol) (Fig. 1) was conducted using the reported method [14, 21] with little modification. Of the standards, paeoniflorin, albiflorin and paeonol were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan), PGG from Toronto Research Chemicals (ON, Canada), (+)-catechin from Cayman Chemical Company (MI, USA), gallic acid and benzoic acid from Nacalai Tesque Inc. (Japan), and methyl gallate from ChromaDex (CA, USA). Reagents for HPLC analysis including acetonitrile, distilled water (both of HPLC grade) and phosphatic acid (analytical grade) were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Japan).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of 8 compounds

A Jasco HPLC system equipped with a PU-1580 pump, an LC-1580-02 ternary gradient unit, and an MD-1510 multiple wavelength detector was used. Analysis was carried out using a YMC Pack AQ-303 (ODS, 4.6 mm i.d. × 250 mm, 5 μm) with column temperature at 27 °C. The mobile phase consisted of binary eluents of (A) 0.1 % (v/v) phosphatic acid and (B) CH3CN under gradient conditions (0 min, 10 % B; 5 min, 15 % B; 40 min, 30 % B; 45 min, 70 % B; 46 min, 80 % B; 50 min, 80 % B; 55 min, 10 % B; 65 min, 10 % B). Flow rate was 1.0 ml/min. Detection was performed at a wavelength of 232 nm.

Each standard was accurately weighed and dissolved in 75 % EtOH to make a stock solution of 1.0 mg/ml. To make calibration curves, a series of standard solutions (200, 100, 20, 10, 2 µg/ml) were prepared from the stock solution. The calibration curve of each component was prepared by plotting the peak areas against a series of injection amounts.

The respective samples (10–50 g) were pulverized and then screened through a 300-µm sieve to obtain homogeneous fine powder of each sample; 0.3 g of the fine powder was accurately weighed and extracted with 75 % EtOH (9 ml, 8 ml × 2) by ultrasonication at room temperature for 30 min, mixed periodically by vortex to obtain full extraction. The supernatant was then obtained by centrifugation at 2,500 rpm (Kubota 3740, Japan) for 10 min. Supernatants were combined into a 25.0-ml volumetric flask and finally filled with 75 % EtOH to the volume. After filtration through a 0.2-µm Millipore filter unit (Advantec, Japan), 20.0 µl of this solution was injected into the HPLC system for analysis.

The quantitative analysis data was further subjected to principal component analysis (PCA) by using software IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 19.0) to facilitate characterization of WPR and RPR.

Results and discussion

Genetic characterization based on ITS sequences

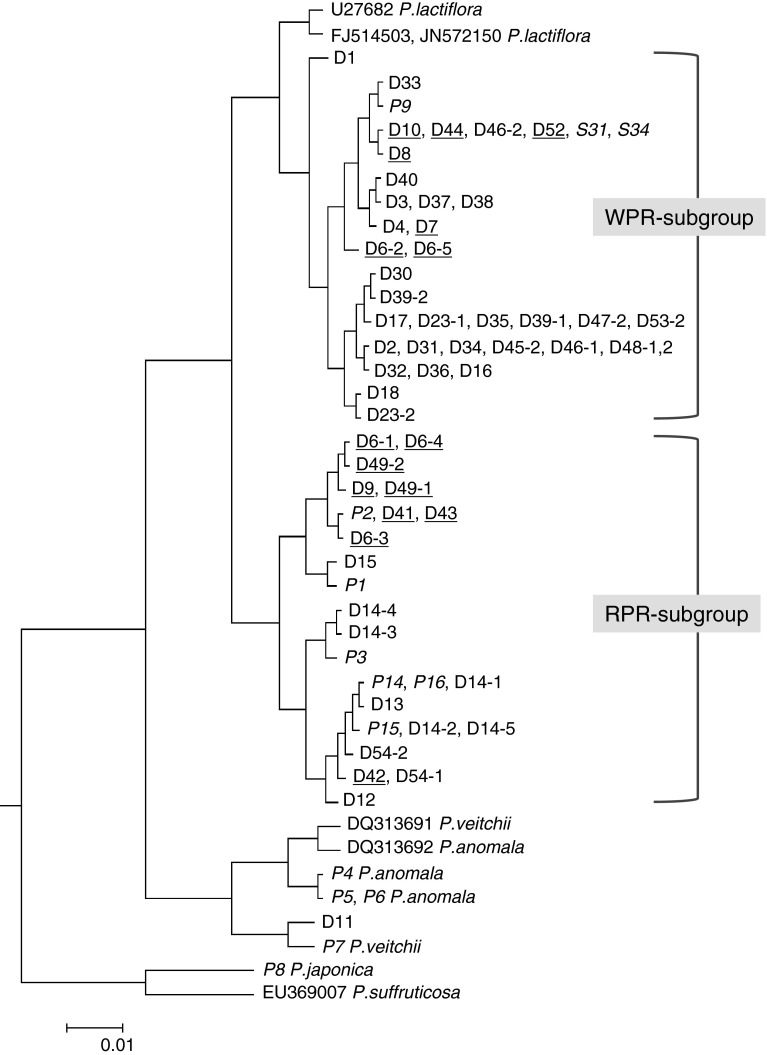

The ITS sequences of specimens of the four Paeonia species as well as the crude drug samples were clearly determined and compared. All the sequences were of the same length, in which the ITS1 region was 267 bp, the 5.8S rRNA gene region was 164 bp, and the ITS2 region was 221 bp. The specimens of the 4 species showed their own ITS sequences which had > 99 % homology to the corresponding sequences of the respective species registered in INSD. All the determined sequences were compared using ClastalW2, a program for multiple sequence alignment. The program constructed a guide tree (Fig. 2) on the basis of sequence similarity to facilitate the alignment. In this guide tree, P. lactiflora formed a large group which was completely separate from P. veitchii, P. anomala, P. japonica and P. suffruticosa. Of the crude drug samples collected from markets, only a sample of RPR (D11) collected from Sichuan province presented an almost identical sequence to that of P. veitchii (P7) and was identified as P. veitchii (Fig. 2). Other samples which included both WPR and RPR were confirmed to be P. lactiflora based on the sequence similarity. Within the group of P. lactiflora, two main subgroups were further clustered (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that the WPR produced in the southern parts of China belonged to one subgroup (WPR subgroup) and the RPR produced in the northern parts of China fell into another subgroup (RPR subgroup) (Fig. 2). The results clearly indicated that the ITS sequence was informative and sufficiently powerful to discriminate Paeonia plants at either inter-species or intra-species levels and suggested that WPR and RPR were geographically isolated and genetically separated.

Fig. 2.

Guide tree obtained from multiple sequence alignment on the basis of sequence similarity. *Italic numbers, plant materials; underlined numbers, PR produced in Japan

Within P. lactiflora, significant intra-species polymorphism of the ITS sequences was detected. Although Sang et al. [7] reported that there was almost no polymorphism in the ITS sequence among intraspecific populations, the present study, by sampling dozens of accessions widely collected from China and Japan, indicated a significant polymorphism in the ITS sequences of P. lactiflora. Table 3 shows nucleotide differences among various types of ITS sequences from P. lactiflora-derived samples. The ITS sequences of P. lactiflora deposited in INSD included two main types, which differed from each other by three nucleotides at positions 69, 458 and 523 (Table 3). Type 1 (U27682 reported by Sang et al. [7] ) shows three cytosines (C–C–C), while type 2 (JN572150 reported by Sun and Hong [22] ) has thymine, adenosine and thymine (T-A-T) at the three sites. According to the nucleotides at these three sites, the samples analyzed in the present study were divided into two main groups corresponding to the two subgroups as shown in Fig. 2. One subgroup which included all the samples of WPR produced in Anhui, Zhejiang and Sichuan provinces and the two Japanese medicinal cultivars (S31, S34) showed T69-A458-T523 at the same three sites as the type 2. The other subgroup which included plant specimens of wild P. lactiflora (P1–P3) as well as the RPR samples, except for sample D16 from Sichuan province, showed additive nucleotides (double nucleotides detected at the same site) as Y (T&C), M (A&C) and Y at the three sites (Y69-M458-Y523), respectively. Three PR samples (D6-2, D6-5, D8) with additive nucleotides at one or two of the three sites presented intermediate type of sequences.

Apart from the difference at the above three sites, nucleotide additivities were observed at another 17 positions (Table 3). Due to the bi-parental inheritance mode of the nrDNA ITS region, nucleotide additivities detected in the sequence are potentially advantageous features for speculating hybridization and inferring progenitors and lineages [7]. However, lineages other than P. lactiflora which are possibly involved and responsible for these nucleotide additivities could not be implied even through wide comparison of the ITS sequences from genus Paeonia registered in INSD. Future investigation around wild habitats of P. lactiflora and subsequent sequencing of related samples might provide further evidence. Among such sites, additivities detected at nucleotide positions 239 and 246 were found to be in common within the WPR subgroup, and those at position 93 were almost in common within the RPR subgroup. Detailed sequence comparison indicated that the divergent sites in the ITS sequence have the potential to discriminate between WPR and RPR; in particular, the nucleotides at positions 69, 458 and 523 were the most informative.

The two Japanese medicinal cultivars of P. lactiflora—‘Bonten’ (S34) and ‘Kitasaisho’ (S31)—showed the same sequence which was identical to a type of sequence from WPR (AB920144, Table 3). The PR produced in Nara prefecture which is usually called ‘Yamato Shakuyaku’ is believed to be derived from ‘Bonten’; however, two samples (D9, D42) out of the five produced in Nara prefecture also belonged to the RPR subgroup, but not the WPR subgroup. Meanwhile, analysis of five individual samples which were randomly picked from a crude drug sample produced in Niigata prefecture (D6-1–5) achieved five types of ITS sequences; however, none were the same as the Japanese medicinal cultivars. Such sequences were detected in diverse horticultural cultivars of P. lactiflora (unpublished data), which suggested that PR from Japanese markets included not only roots of the medicinal cultivars but also roots of the horticultural cultivars of P. lactiflora.

Chemical comparison on the basis of quantitation of 8 main components

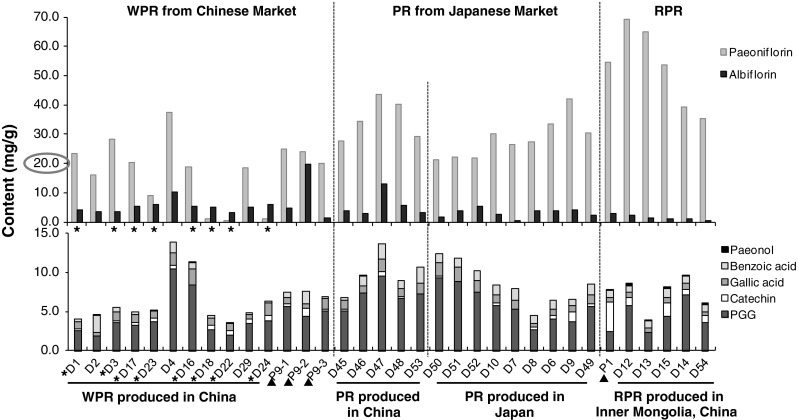

The contents of 8 main components were quantitatively analyzed to clarify the chemical properties of P. lactiflora, P. veitchii, P. anomala, and the crude drug samples including WPR, PR and RPR. Within the commercial samples derived from P. lactiflora, the RPR samples produced in the northern parts of China had an obviously higher content of paeoniflorin and paeonol, but a lower content of albiflorin than WPR/PR produced in the southern parts of China and most of the PR produced in Japan. Among the 11 commercial samples of WPR collected from various places in China, eight samples contained < 20 mg/g of paeoniflorin. In particular, the three samples (D18, D22, D24) had extremely low content of paeoniflorin (< 1.5 mg/g). When the HPLC chromatograms of these 3 samples were compared with others, a conspicuous peak with a retention time at approximately 10.4 min was commonly observed in these 3 samples, which was not detected in the PR collected from the Japanese markets. Wang et al. [14] reported that an artifact compound, paeoniflorin sulphonate, could be detected in WPR which has been processed by sulfur fumigation (a traditional process for crude drugs in traditional Chinese medicine). Further analysis using LC/MS clearly indicated this notable peak was paeoniflorin sulphonate (data not shown). In the HPLC chromatograms of more than half of the WPR collected from Chinese markets (indicated in Fig. 3), the paeoniflorin sulphonate peak was detected. This result indicated that the WPR available from Chinese markets was usually processed by sulfur fumigating which resulted in an extremely low content of paeoniflorin; however, the PR available from Japanese markets did not undergo this process (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Contents of 8 compounds in WPR, PR and RPR derived from P. lactiflora. *WPR which was processed by sulfur fumigation. D16 was purchased in Guangxi, China as RPR; however, genetic analysis indicated it belonged to the WPR subgroup. Therefore we placed it within the WPR group. ▲P9 and P1 were collected in Zhejiang and Inner Mongolia, respectively, where are the production areas of WPR and RPR

Table 4.

Contents of 8 compounds in Paeonia species and crude drug samples of WPR, PR and RPR

| Code no. |

Content (mg/g) Content (mg/g) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paeoniflorin | Albiflorin | PGG | Gallic acid | Catechin | Benzoic acid | Paeonol | Methylgallate | |

| D1 | 23.39 | 4.07 | 2.57 | 0.89 | 0.26 | 0.32 | ND | ND |

| D2 | 16.00 | 3.41 | 1.91 | 0.39 | ND | 2.20 | 0.02 | ND |

| D3 | 28.29 | 3.43 | 3.60 | 1.14 | 0.24 | 0.60 | ND | Trace |

| D17 | 20.21 | 5.33 | 3.31 | 0.98 | 0.30 | 0.34 | ND | ND |

| D23 | 9.12 | 5.92 | 3.72 | 0.91 | 0.46 | 0.13 | ND | ND |

| D4 | 37.58 | 10.36 | 10.51 | 1.60 | 0.40 | 1.39 | ND | ND |

| D16 | 18.82 | 5.21 | 8.37 | 2.15 | Trace | 0.72 | 0.05 | ND |

| D18 | 1.11 | 4.93 | 2.72 | 0.97 | 0.53 | 0.26 | Trace | ND |

| D22 | 0.53 | 3.16 | 2.05 | 0.88 | 0.53 | 0.17 | ND | ND |

| D29 | 18.48 | 4.96 | 3.52 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.20 | ND | ND |

| D24 | 1.21 | 5.87 | 3.87 | 1.60 | 0.68 | 0.17 | ND | ND |

| P9-1 | 24.81 | 4.77 | 5.71 | 0.84 | 0.29 | 0.68 | ND | ND |

| P9-2 | 23.90 | 19.66 | 4.39 | 0.57 | 1.03 | 1.63 | ND | ND |

| P9-3 | 20.02 | 1.47 | 5.11 | 1.39 | 0.23 | 0.20 | ND | ND |

| D45 | 27.54 | 3.73 | 5.09 | 1.21 | 0.22 | 0.28 | ND | ND |

| D46 | 34.42 | 2.77 | 7.38 | 0.95 | Trace | 1.20 | 0.03 | ND |

| D47 | 43.46 | 13.05 | 9.60 | 1.66 | 0.48 | 1.90 | ND | ND |

| D48 | 40.32 | 5.73 | 6.69 | 1.02 | 0.21 | 1.08 | ND | ND |

| D53 | 29.24 | 3.29 | 7.29 | 1.38 | Trace | 2.03 | ND | ND |

| D50 | 21.17 | 1.81 | 9.35 | 1.75 | 0.16 | 1.12 | ND | ND |

| D51 | 22.10 | 3.78 | 8.87 | 1.88 | ND | 1.08 | ND | ND |

| D52 | 21.82 | 5.28 | 7.44 | 1.57 | ND | 1.21 | ND | ND |

| D10 | 29.97 | 2.67 | 5.83 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 1.28 | ND | ND |

| D7 | 26.45 | 0.48 | 5.34 | 1.10 | ND | 1.47 | ND | ND |

| D8 | 27.36 | 3.70 | 2.66 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 1.13 | ND | ND |

| D6 | 33.42 | 3.80 | 4.10 | 0.81 | 0.43 | 1.12 | Trace | ND |

| D9 | 41.99 | 4.11 | 3.75 | 0.77 | 1.24 | 0.76 | ND | ND |

| D49 | 30.49 | 2.33 | 5.72 | 1.08 | 0.34 | 1.37 | Trace | ND |

| P1 | 54.65 | 2.89 | 2.51 | 0.57 | 3.73 | 0.88 | 0.11 | ND |

| D12 | 69.27 | 2.27 | 5.80 | 0.60 | 1.05 | 0.90 | 0.32 | ND |

| D13 | 64.94 | 1.47 | 2.38 | 0.55 | Trace | 0.90 | 0.14 | ND |

| D15 | 53.64 | 1.22 | 4.39 | 0.63 | 1.75 | 1.23 | 0.23 | ND |

| D14 | 39.43 | 1.04 | 7.18 | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.91 | 0.05 | ND |

| D54 | 35.32 | 0.53 | 3.63 | 0.48 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.27 | ND |

| P7 | 61.92 | 0.64 | 35.45 | 4.79 | ND | 1.01 | ND | ND |

| D11 | 71.36 | 0.69 | 38.32 | 9.79 | ND | 0.82 | ND | 0.78 |

| P4 | 8.42 | 2.65 | 11.08 | 2.25 | ND | 0.68 | ND | ND |

| P5 | 13.00 | 0.24 | 11.29 | 1.62 | ND | 0.79 | 0.01 | ND |

| P6 | 15.62 | 0.28 | 16.56 | 2.51 | ND | 0.81 | ND | ND |

ND, not detected; trace, lower than limit of quantitation

The root of P. veitchii (P7), as well as the RPR sample derived from this species (D11) showed the highest content of paeoniflorin (6.19–7.14 %), PGG (3.55–3.83 %) and gallic acid (0.48–0.98 %), and clearly differed from the samples derived from P. lactiflora. In particular, the contents of PGG as well as gallic acid were twice as high as those in other species. Such characteristics in the chemical composition have been supported by the reported data [21]. In the roots of P. anomala (P4–P6), the content of paeoniflorin was very low and catechin was not detected.

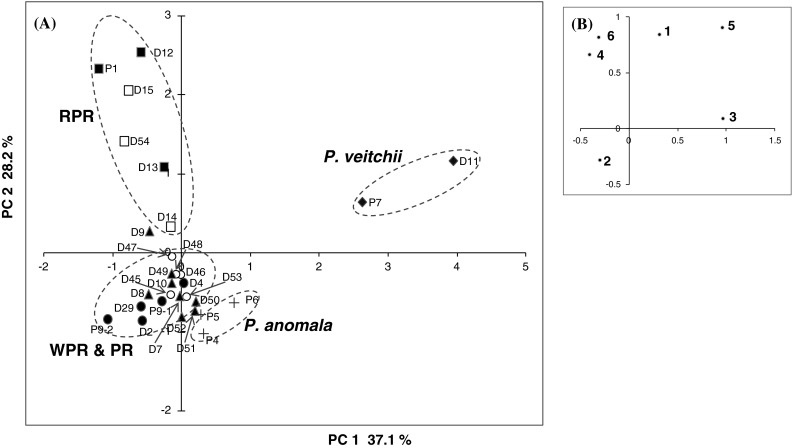

Apart from the WPR samples which were thought to be processed by sulfur fumigation, the quantitative data of the 6 main compounds in Paeonia specimens and commercial samples were subjected to PCA analysis in order to compare the chemical characteristics of WPR and RPR derived from P. lactiflora, as well as the related species. The PCA scores plot is shown in Fig. 4a, where the first and second principal components accounted for 65.3 % of the total variance (PC1, 37.1 %; PC2, 28.2 %). The PCA loading plot (Fig. 4b) indicated that compounds 3 and 5 contributed much to the positive value of PC1, and compounds 1 and 4–6 contributed much to the positive value of PC2. The distribution of all the samples in the PCA scores plot (Fig. 4a) showed that four separated groups were clustered. Besides the respective groups of P. veitchii and P. anomala, samples derived from P. lactiflora were clearly classified into two groups—one group included RPR and the other group was composed of WPR, PR produced in China and most of the PR produced in Japan. By comparing the scores plot and loading plot, the characteristic chemical composition of the respective groups could be easily observed. The P. veitchii group which was different from other groups had a significantly high content of paeoniflorin, PGG and gallic acid. The RPR group had an obviously high content of paeonol, catechin and paeoniflorin, while the WPR/PR group had a relatively high content of albiflorin. Moreover, the grouping result in the PCA scores plot was in accordance with the clustering result based on the similarity of ITS sequences.

Fig. 4.

Principal component analysis of chemical component data from Paeonia specimens and peony root samples. a Scores plot, filled circle WPR produced in China and P9-2, open circle PR produced in China, filled triangle PR produced in Japan, filled square RPR in Chinese market and P1, open square RPR in Japanese market. Above are P. lactiflora. Plus symbol, P. anomala; filled diamond, P. veitchii. b Loading plot; 1 paeoniflorin, 2 albiflorin, 3 PGG, 4 (+)-catechin, 5 gallic acid, 6 paeonol

Conclusion

The present study determined the nucleotide sequence of the ITS region and conducted quantitative analysis of 8 main chemical components of four Paeonia species, as well as commercial samples of WPR, PR and RPR collected from Chinese and Japanese markets. The ITS sequence was informative and sufficiently powerful to discriminate Paeonia plants at either inter-species or intra-species levels. Significant intra-species polymorphism of the ITS sequences was detected within P. lactiflora. Clustering analysis based on the ITS sequences of the samples showed that P. lactiflora formed a group which was completely separate from other Paeonia species. Within the P. lactiflora group, the WPR and PR produced in the southern parts of China and the RPR produced in the northern parts of China were clearly clustered into two subgroups. The nucleotides at positions 69, 458 and 523 upstream of the ITS sequence served as molecular markers to discriminate between WPR and RPR. The medicinal cultivars ‘Bonten’ and ‘Kitasaisho’, as well as half of the PR produced in Japan belonged to the WPR subgroup. Quantitative analysis of 8 main components clarified the chemical properties of three Paeonia species as well as the WPR and RPR derived from P. lactiflora. The root of P. veitchii and its derived RPR sample showed the highest content of paeoniflorin, PGG and gallic acid, which clearly differed from those derived from P. lactiflora. As for the samples derived from P. lactiflora, the RPR samples produced in the northern parts of China had an obviously higher content of paeoniflorin and paeonol, but a lower content of albiflorin than the WPR and PR produced in the southern parts of China and the PR produced in Japan. Chemical analysis indicated that the WPR available in Chinese markets was usually processed by sulfur fumigation, which resulted in an extremely low content of paeoniflorin. The present study indicated that WPR and RPR were not only geographically isolated, but also genetically and chemically separated. The ITS sequence provided a genetic index for their identification.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Javzan Batkhuu, National University of Mongolia and Dr. Chinbat Sanchir, Institute of Biology, Mongolian Academy of Science, Mr. Morikazu Murakami and the staff of Toyama Prefectural Medicinal Plants Center, Dr. Shengli Wei, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, and Dr. Kyoko Takahashi, Osaka University for kind help in sample collection. We thank Dr. Kohei Kazuma, Institute of Natural Medicine, University of Toyama for measurement of paeoniflorin sulphonate by LC/MS. This work was supported by MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI Grant Nos. 21406004 and 24406005, and in part by a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan (H22-SOYAKUSOGO-General-013).

Contributor Information

Shu Zhu, Phone: +81-76-4347606, Email: szhu@inm.u-toyama.ac.jp.

Katsuko Komatsu, Phone: +81-76-4347601, Email: katsukok@inm.u-toyama.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Namba T (1993) The encyclopedia of Wakan-Yaku (Traditional Sino-Japanese Medicines) with color pictures, 2nd edn, vol I. Hoikusha Publishing Co. Ltd., Osaka, pp 102-104

- 2.Mikage M, Ona N. Herbological study of red peony and white peony used in Chinese medicine. Kampo Med. 2009;60:419–428. doi: 10.3937/kampomed.60.419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai SQ, Qing LP, Chen DF, Yin J, editors. Pharmacognosy. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2011. pp. 130–133. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2011) The Japanese pharmacopoeia, 16th edn, p 1704 (English version)

- 5.The State Pharmacopoeia Commission of China (2010) Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China, vol 1 (English version). China Medical Science Press, Beijing, pp 306–308

- 6.Japan Kampo Medicinal Manufacturers Association (2013) Survey reports on annual consumption of herbal drugs (2). Tokyo, p 8

- 7.Sang T, Crawford DJ, Stuessy TF. Documentation of reticulate evolution in peonies (Paeonia) using internal transcribed spacer sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA: implications for biogeography and concerted evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6813–6817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sang T, Crawford D, Stuessy T. Chloroplast DNA phylogeny, reticulate evolution, and biogeography of Paeonia (Paeoniaceae) Am J Bot. 1997;84:1120–1136. doi: 10.2307/2446155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sang T, Donoghue MJ, Zhang D. Evolution of alcohol dehydrogenase genes in peonies (Paeonia): phylogenetic relationships of putative nonhybrid species. Mol Biol Evol. 1997;14:994–1007. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan J, Zhang D, Sang T. Molecular phylogenetic evidence for the origin of a diploid hybrid of Paeonia (Paeoniaceae) Am J Bot. 2007;94:400–408. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wen J, Zimmer EA. Phylogeny and biogeography of Panax L. (the Ginseng genus, Araliaceae): inferences from ITS sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1996;6:167–177. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.China Plant BOL Group Comparative analysis of a large dataset indicates that internal transcribed spacer (ITS) should be incorporated into the core barcode for seed plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19641–19646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104551108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu SH, Wu DG, Chen YW. Chemical constituents and bioactivities of plants from genus Paeonia. Chem Biodivers. 2010;7:90–104. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200800148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Q, Liu RX, Guo HZ, Ye M, Huo CH, Bi KS, Guo DA. Simultaneous LC determination of major constituents in red and white peony root. Chromatographia. 2005;62:581–588. doi: 10.1365/s10337-005-0660-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo NC, Ding W, Qian DW, Li ZH, Qian YF, Guo JM, Duan JA. UPLC-Q-TOF/MS Coupled with multivariate statistical analysis as a powerful technique for rapidly exploring potential chemical markers to differentiate between Radix Paeoniae Alba and Radix Paeoniae Rubra. Nat Prod Commun. 2013;8:487–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sukrong S, Zhu S, Ruangrungsi N, Phadungcharoen T, Palanuvej C, Komatsu K. Molecular analysis of the genus Mitragyna existing in Thailand based on rDNA ITS sequences and its application to identify a narcotic species: Mitragyna speciosa. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:1284–1288. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitani Y, Zhu S, Batkhuu J, Sanchir C, Komatsu K. Genetic diversity of Ephedra plants in Mongolia inferred from internal transcribed spacer sequence of nuclear ribosomal DNA. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34:717–726. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He JY, Zhu S, Komatsu K, Goda Y, Cai SQ. Genetic polymorphism of medicinally-used Codonopsis species in an internal transcribed spacer sequence of nuclear ribosomal DNA and its application to authenticate Codonopsis Radix. J Nat Med. 2014;68:112–124. doi: 10.1007/s11418-013-0780-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takaiwa F, Oono K, Iida Y, Sugiura M. Nucleotide sequence of the 17S–25S spacer region from rice rDNA. Plant Mol Biol. 1985;4:355–364. doi: 10.1007/BF02418257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiebel K, Hemleben V. Nucleotide sequence of the 18S–25S spacer region from rDNA of mung bean. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:2852. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.7.2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu S, Yang L, Tian RT, Wang ZT, Liu ZJ, Xie PS, Feng QR. Species differentiation and quality assessment of Radix Paeoniae Rubra (Chi-shao) by means of high-performance liquid chromatographic fingerprint. J Chromatogr A. 2009;1216:2163–2168. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun YL, Hong SK. Genetic diversity and phylogenetic analysis of genus Paeonia based on nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS sequence. J Plant Biotechnol. 2011;38:234–240. doi: 10.5010/JPB.2011.38.3.234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]