Abstract

Abstract

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is one of the re-emerging “neglected” tropical diseases whose recent outbreak affected not only Africa and South-East Asia but also several parts of America and Europe. To date, despite its serious nature, no antivirals or vaccines were developed in order to counter this resurgent infectious disease. The recent advancement in crystallography and availability of crystal structures of certain domains of CHIKV initiates the development of anti-CHIKV agents using structure-based drug design or synthetic medicinal chemistry approach. Despite the fact that almost 50 % of the new chemical entities against several biological targets were either obtained from natural products or natural product analogues, a very humble effort was directed towards identification of novel CHIKV inhibitors from natural products. In this review, besides a brief overview on CHIKV as well as the nature as a source of medicines, we highlight the current progress and future steps towards the discovery of CHIKV inhibitors from natural products. This report could pave the road towards the design of novel semi-synthetic derivatives with enhanced anti-viral activities.

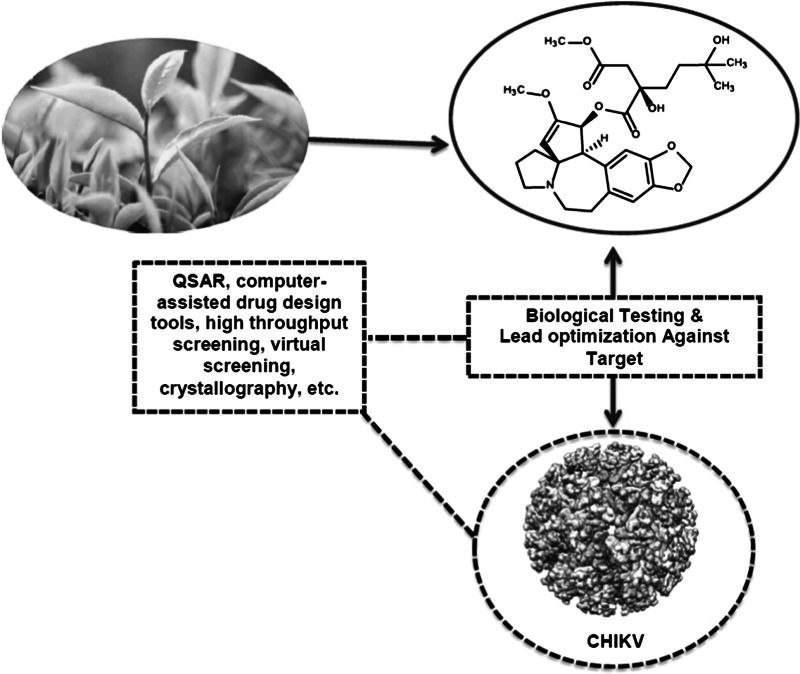

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Chikungunya virus, Antivirals, Natural product

Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a re-emerging arbovirus which belongs to the genus alphavirus and is responsible for chikungunya fever (CHIKF), severe joint pains and rash. The outbreak of CHIKF was first described in 1952 after an outbreak along the border of east African states, Tanganyika and Mozambique. This mosquito born alphavirus is transmitted by mosquitoes of the Aedes genus i.e. Aedes ageypti, Aedes furcifier and Aedes albopictus. Recent research highlighted the occurrence of A226 V mutation in the envelope glycoprotein of CHIKV which increased the CHIKV fitness in A. albopictus as well as improved transmissibility of the virus through A. albopictus [1]. In the mid twentieth century CHIKV emerged as a major epidemic in India and South East Asia [1, 2]. After several minor outbreaks in Africa, during 1999–2000 there was a large outbreak of CHIKV in the Republic of the Congo and further outbreak was documented in Gabon through A. albopictus. The beginning of 20th century observed a huge outbreak of chikungunya in India and several islands of South-East Asia [1, 3]. Since 2005, India and countries in South-East Asia have reported over 1.9 million cases (Fig. 1b). In 2007, CHIKV transmission was reported for the first time in Europe [4].

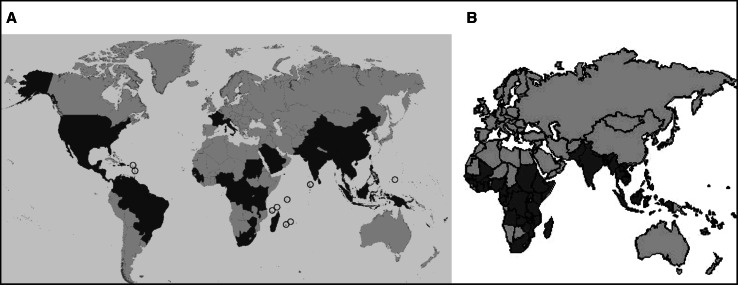

Fig. 1.

a Countries and territories where chikungunya cases have been reported (highlighted in green as of November 18, 2014) and b cases of chikungunya outbreak during 1952–2006, the regions highlighted in ‘red’ have been reported with chikungunya outbreak during that period [3]

Recently the outbreak of chikungunya Caribbean island was the first of its kind in the western hemisphere with 66 confirmed cases and suspected cases of around 181 [3]. By the beginning of the year 2014 an estimated 30,000 cases of CHIKV were confirmed in the Caribbean island which brings the most alarming situation about the re-emerging status of chikungunya [3]. Since then several cases of CHIKV were documented in several parts of USA with an alarming rate (Fig. 1a). This sudden re-emergence of CHIKV across different parts of developed countries such as USA led to a rising effort from academic research to identify novel inhibitors targeting this re-emerging neglected disease.

Nature as a source of medicines: a brief overview

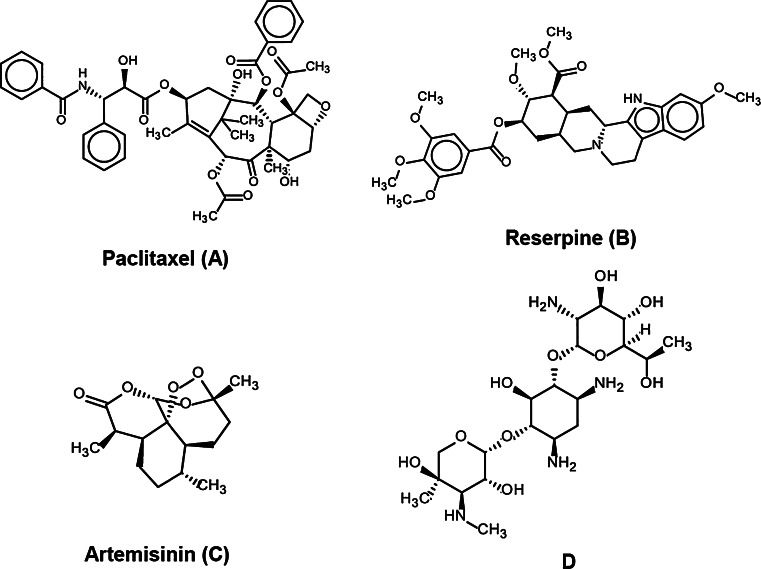

Chemical constituents isolated from natural products emerged as a source of novel therapeutics since early stages of drug discovery. Statistically around 50 % of the new chemical entities either obtained from natural products or natural product analogues [5–9]. Several natural products and natural product analogues have been widely used in a variety of different therapeutic indications, for instance, a few examples are presented here (Fig. 2a, b).

Fig. 2.

Some example of natural products used in the treatment of several diseases. 2D structures of several natural product drugs used in the treatment of cancer (paclitaxel, a), hypertension (reserpine, b), malaria (artemisinin, c). Compound d [10] is one of the natural product which displayed inhibitory activity against neglected tropical disease, dengue virus infection

Natural sources for medicines against tropical diseases

The first spark of success was the discovery of the natural compound artemisinin (Fig. 2c) to treat malaria, one of the serious tropical diseases [11]. This was followed by a slow but steady increase in natural product based inhibitors towards re-emerging neglected tropical diseases especially against malaria and dengue virus (DENV) [10] (Fig. 2d). The natural product based treatment of malaria revolves around discovery and development of novel analogs/derivatives of highly active natural products e.g. salinosporamide A, a marine actinomycetes with antimalarial property, febrifugine and artemisinin [12]. The development of natural product inspired medicinal chemistry approach led to development of halofuginone, as well as some highly active febrifugine analogues as well as development of novel artemisinin analogues [12]. Similarly, several novel scaffolds were identified against different serotypes of DENV by exploiting the pool of natural products. This exploration led to identification of several terpenoids, polycyclic quinones, phenolics, alkaloids, flavonoids and polysaccharides against different serotypes of DENV [10]. The success in identifying a diverse set of natural product based scaffolds against DENV inspired the progress of natural product based inhibitors in targeting other neglected tropical diseases such as CHIKV.

To best of our knowledge this review is first of its kind that highlights the current status in natural product based inhibitors targeting CHIKV.

Structural biology of CHIKV

The genome of CHIKV is a positive sense, single stranded RNA genome consists of two open reading frames, one in 5′ end which encodes non-structural proteases necessary for formation of viral replicase complexes and other 3′ end which encoded structural proteins, necessary for receptor binding and fusion with cell membrane [1, 4, 13].

Despite the advancement in crystallography and structural biology, the rational drug discovery targeting several domains of CHIKV genome were limited due to lack of crystallographic evidences. The crystal structures of CHIKV non-structural protease 2 (NSP2), non-structural protease 3 (NSP3) macrodomain and immature envelope glycoprotein complexes were resolved which emerged as a promising starting point to develop novel inhibitors targeting CHIKV [13].

Some of the recent reviews highlighted the detailed features of CHIKV genome and its application in modern era of antiviral drug discovery [1, 4, 13]. Herein, we emphasize on the structural features of CHIKV NSP2, NSP3 macrodomain and envelope glycoprotein complexes which emerged as crucial drug targets to develop novel antivirals targeting this re-emerging disease.

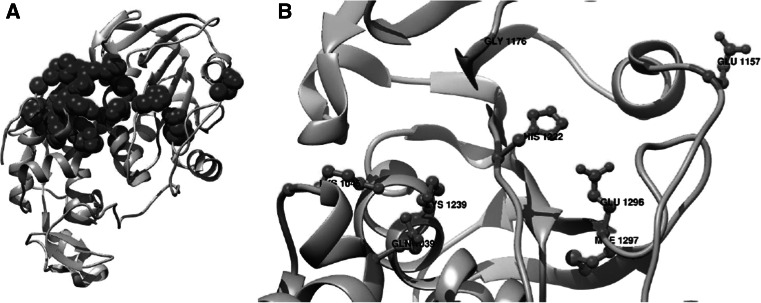

CHIKV NSP2 is responsible for protease and helicase activity and thus emerged as a crucial target to develop novel antivirals [1, 13]. Both N and C terminal domains are composed of α-helices and β-strands. The active site of CHIKV NSP2 is composed of residues located at C-terminal domains. The active site (Fig. 3a) of NSP2 consists of some key residues include Gln1039, Lys1045, Glu1157, His1222, Cys1239, Ser1293, Glu1296 and Met1297 (Fig. 3b) [1]. CHIKV NSP2 is a cysteine protease thus cysteine residues played an important role in enzyme activity. Structural analysis of NSP2 showed the existence of three N-terminal cysteine residues (Cys1013, Cys1057 and Cys1121) as well three C-terminal cysteine residues (Cys1233, Cys1274 and Cys1290). C-terminal cysteine residues Cys1233 and Cys1290 in combination with histidine residues (His1222, His1228, His1229 and His1236) could be associated with deprotonation mechanism and thus played a major role in viral pathogenesis [1].

Fig. 3.

Representation of CHIKV NSP2 (PDB: 3TRK [14]) which highlights the active site region of NSP2 (represented in green spheres, a as well as critical residues of active site are highlighted in orange (ball and stick representation, b)

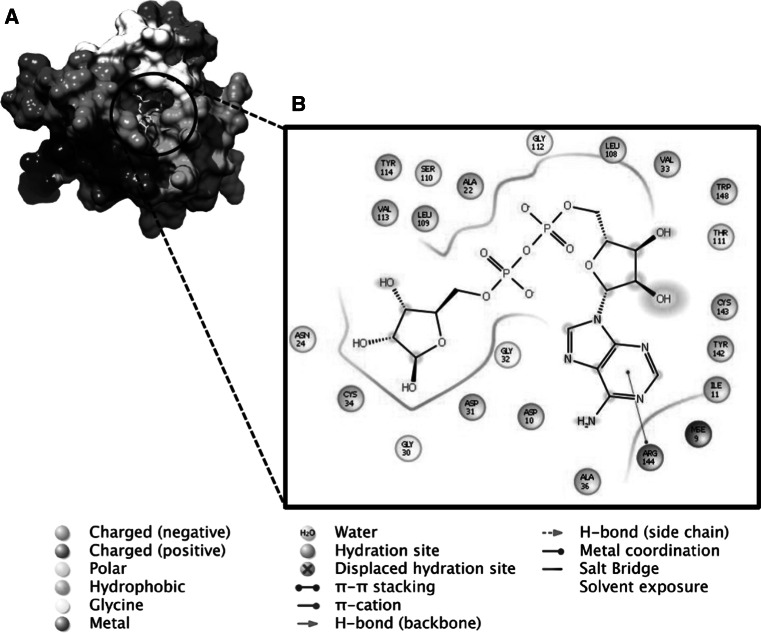

Similar to NSP2, the crystal structure of N-terminal domain of CHIKV NSP3 emerged as a potential drug target to develop novel antivirals [15]. Advancement in crystallography led to discovery of high resolution crystal structure of CHIKV NSP3 in complex with ADP ribose (Fig. 4) [16]. NSP3 macrodomain believed to play a major role in metabolism of ADP ribose derivatives that played major role in cell regulatory function [1, 16]. Thus, understanding the binding region of ADP ribose derivative could serve as a starting point to develop novel inhibitors targeting CHIKV [1].

Fig. 4.

Structure of CHIKV NSP3 macrodomain in complexed with ADP ribose derivative (PDB: 3GPO [16], a). The active site residues interacting with NSP3 active site might act as a foot print to design novel chemical entities targeting CHIKV NSP3

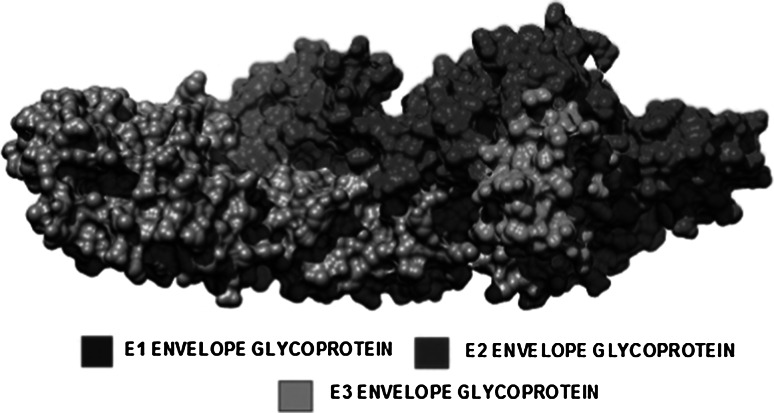

Similar to NSP3 macrodomain and NSP2, the mature envelope glycoprotein complex comprises of E1-E2-E3 structural proteins [17] (Fig. 5) led to identification of two plausible binding sites which might help in development of novel anti-CHIKV agents targeting viral structural proteins.

Fig. 5.

The mature glycoprotein complex of CHIKV (PDB: 3N42 [17]) which might act as a promising target to develop novel drug molecules targeting CHIKV structural proteins

Till date, except the below-mentioned a few attempts (Sect. “Natural products targeting CHIKV: a medicinal chemistry perspective”), a humble effort has been directed rationally to design anti-CHIKV inhibitors targeting these drug targets. Therefore, further natural products and natural product-based optimization studies should be encouraged in order to identify novel chemical entities targeting different structural/non-structural proteins of the “neglected” CHIKV.

Natural products targeting CHIKV: a medicinal chemistry perspective

Despite the success of natural products as treatments for various diseases like cancer [18, 19], malaria [20], and HIV [21], the “neglected” CHIKV—and some others like Sindbis virus (SINV)—has not received much attention from researchers. Herein, we compile the efforts that have been made so far towards the identification of novel leads from natural products that aimed to target CHIKV.

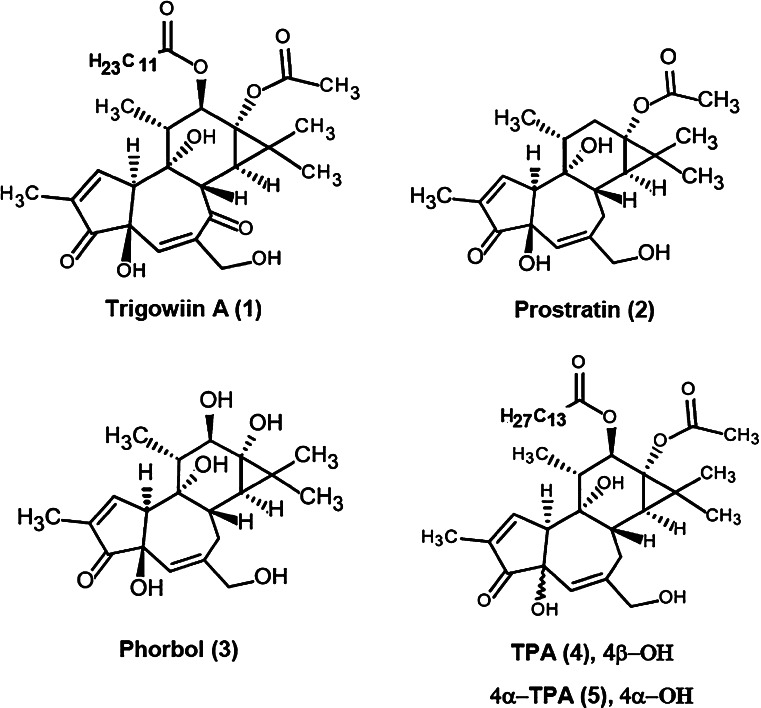

Recently the study of a Vietnamese plant species Trigonostemon howii led to isolation of a new tigliane-type diterpenoid, trigowiin A (1). Trigowiin A (1) (Fig. 6) exhibited moderate antiviral activity in a virus-cell-based assay against CHIKV. Antiviral testing of structurally related tigliane diterpenoids such as prostratin (2), phorbol (3), 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA, 4), and 4α-TPA (5) (Fig. 6) led to identification novel antiviral leads targeting CHIKV [22].

Fig. 6.

2D structural representation of tigliane-type diterpenoids trigowiin A (1) prostratin (2), phorbol (3), 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA, 4), and 4α-TPA (5)

Besides the moderate CHIKV inhibitory activity possessed by trigowiin A, prostratin and TPA, two structurally related tigliane-type diterpenoids, displayed potent and selective anti-CHIKV activity (Table 1) [22]. The strong inhibitory activity observed by prostratin (EC50 = 2.6 μM and a selectivity index of 30) might initiate future efforts to design optimized novel tigliane type diterpenoids-based inhibitors since this chemical scaffold proved potential as CHIKV inhibitor (Table 1) [22]. Bourjit et al. [22.] postulated that activation of the signal transduction enzyme protein kinase C (PKC) could be the main reason behind the antiviral activity of these molecules (compounds 1–5) on CHIKV which is quite similar to the proposed mechanism of TPA on HIV replication [23]. Thus the structure and pharmacophoric features of these compounds might be effective in order to develop specific PKC activators as potential anti-CHIKV agents.

Table 1.

Antiviral activities of compounds 1–5 in vero cells against CHIKV [22]

| Compounds | CC50 vero cells (μM) | EC50 CHIKV (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Compound 1 | >100 | 43.5 ± 12.8 |

| Compound 2 | 79.0 ± 17.4 | 2.6 ± 1.5 |

| Compound 3 | >343 | >343 |

| Compound 4 | 5.7 ± 1.7 | 0.0029 ± 0.0003 |

| Compound 5 | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.5 |

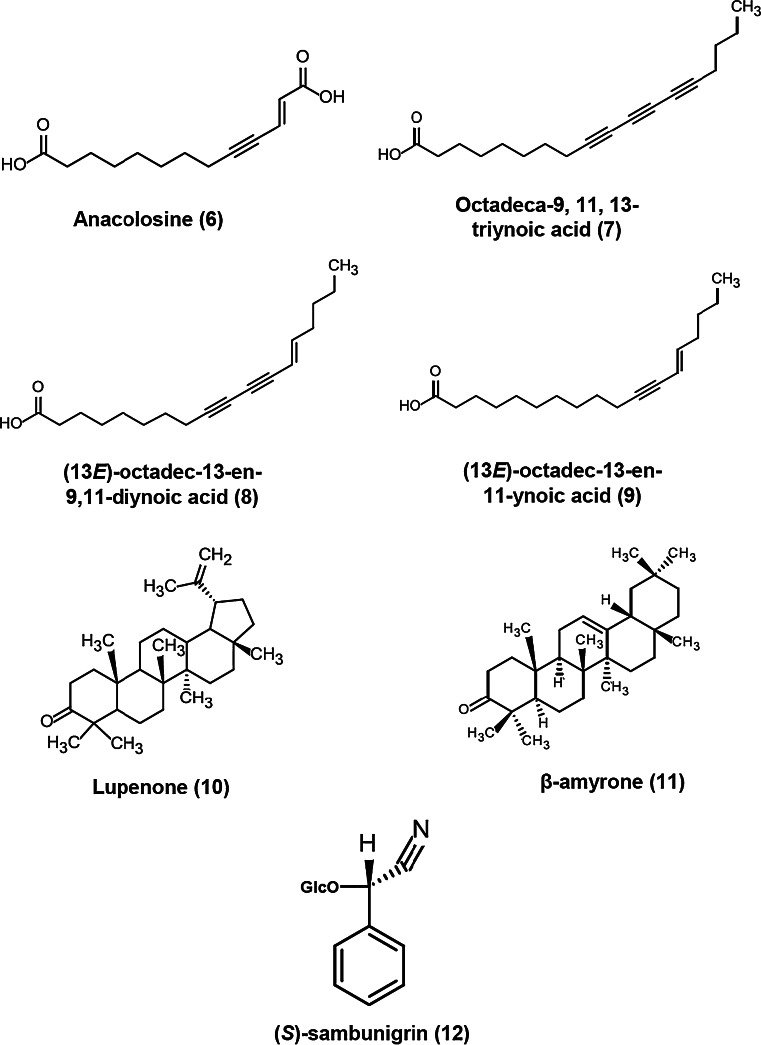

In an effort to identify novel scaffolds targeting CHIKV replication, an extensive study taking in account 820 ethyl acetate extracts of Madagascan plants was performed in a virus-cell-based assay for CHIKV. This exploration led to identification of one new(E)-tridec-2-en-4-ynedioic acid named anacolosine (6), together with three known acetylenic acids, the octadeca-9,11,13-triynoic acid (7), (13E)-octadec-13-en-9,11-diynoic acid (8), (13E)-octadec-13-en-11-ynoic acid (9), two terpenoids, lupenone (10) and β-amyrone (11), and one cyanogenic glycoside, (S)-sambunigrin (12) (Fig. 7) [24].

Fig. 7.

Structural representation of anacolosine (6), octadeca-9,11,13-triynoic acid (7), (13E)-octadec-13-en-9,11-diynoic acid (8), (13E)-octadec-13-en-11-ynoic acid (9), lupenone (10), β-amyrone (11), and (S)-sambunigrin (12)

The inhibitory activity of these chemical entities was tested against CHIKV in a viral cell-based assay. Two terpenoids, lupenone (10) and β-amyrone (11) displayed moderate inhibitory activity against CHIKV with EC50 77 μM and 86 μM, respectively (Table 2) [24]. The inhibitory effect of lupenone (10) further confirmed that lupane based triterpenoid skeleton are selective inhibitors of CHIKV and can be further optimized in order to provide semi-synthetic derivatives with enhanced anti-viral activity.

Table 2.

Antiviral activities of compounds 6–12 in vero cells against CHIKV [24]

| Compounds | CC50 vero cells (μM) | EC50 CHIKV (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Compound 6 | >420 | >420 |

| Compound 7 | 30 | >30 |

| Compound 8 | 23 | >23 |

| Compound 9 | 30 | >30 |

| Compound 10 | >235 | 77 ± 26 |

| Compound 11 | >235 | 86 ± 9 |

| Compound 12 | >426 | >426 |

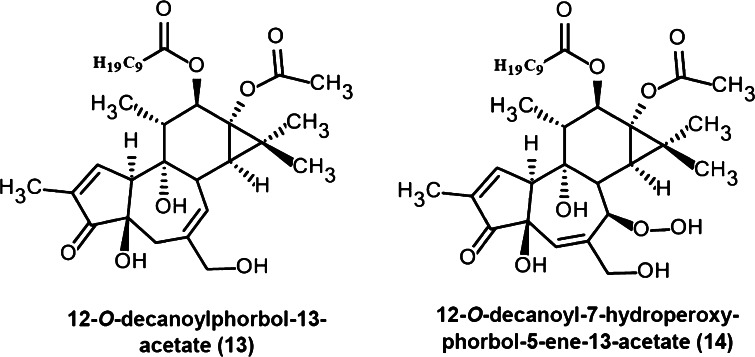

Further, bioassay guided purification and virus cell-based assay of an EtOAc extract of the leaves of Croton mauritianus led to isolation of two phorbol esters 12-O-decanoylphorbol-13-acetate and 12-O-decanoyl-7-hydroperoxy-phorbol-5-ene-13-acetate as well as five ionone derivatives i.e. loliolide, vomifoliol, dehydrovomifoliol, annuionone D and bluemol C [25]. Virus cell based assay identifies 12-O-decanoylphorbol-13-acetate (13) and 12-O-decanoyl-7-hydroperoxy-phorbol-5-ene-13-acetate (14) (Fig. 8) as novel inhibitors of CHIKV with EC50 of 2.4 ± 0.3 μM and 4.0 ± 0.8 μM, respectively [25]. Exploring the inhibitory effect of structural analogues of these phorbol esters and side chains associated with the main skeleton might act as an area of further exploration to target CHIKV.

Fig. 8.

2D structural representation of 12-O-decanoylphorbol-13-acetate (13) and 12-O-decanoyl-7-hydroperoxy-phorbol-5-ene-13-acetate (14) isolated from the leaves of Croton mauritianus. R3=R4=C9H19

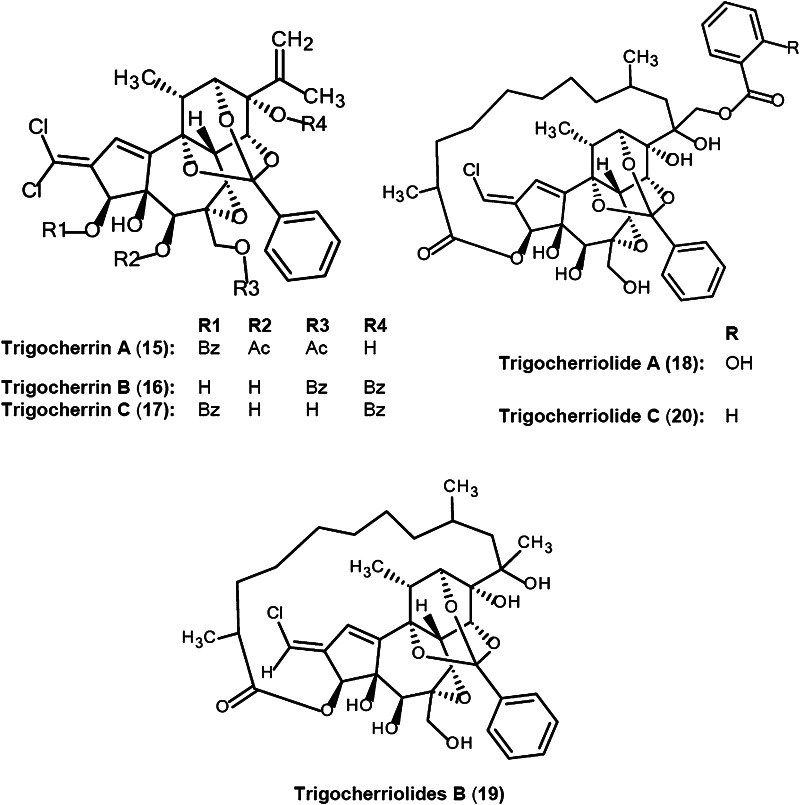

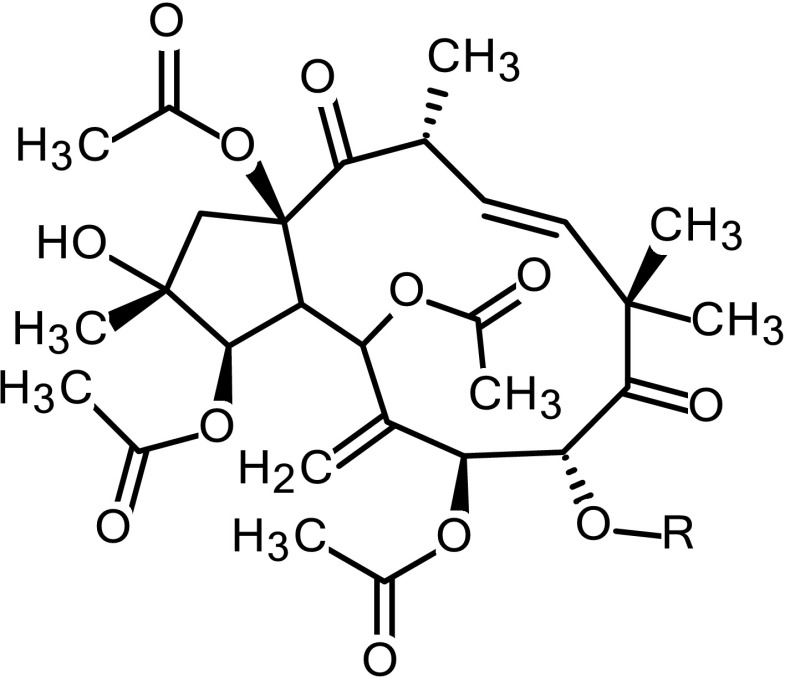

Moreover, A study has been performed on the bark and the wood of a rare endemic plant Trigonostemon cherrieri led to isolation of highly oxygenated daphnane diterpenoid orthoesters (DDO) bearing an uncommon chlorinated moiety: trigocherrins A (15), B (16) and F (17) (Fig. 9) and trigocherriolides A (18), B (19) and C (20) (Fig. 9) displayed moderate to fair activity against CHIKV with EC50 ranging from 1.5 to 3.9 μM [26]. Trigocherrins B was identified as the most active diterpenoid with EC50 1.5 μM against CHIKV in a virus cell based assay (Table 3) [26]. These DDOs further possessed significant inhibitory activity against several other neglected re-emerging pathogens including Sindbis virus (SINV), Semliki forest virus (SFV) and DENV and thus can be explored further to design novel leads targeting several re-emerging viruses.

Fig. 9.

Structural representation of daphnane diterpenoid orthoesters isolated from Trigonostemon cherrieri

Table 3.

Anti-CHIKV activities of compounds 15–20 in virus cell based assay [26]

| Compounds | CC50 vero cells (μM) | EC50 CHIKV (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Compound 15 | 35 ± 8 | 1.5 ± 0.6 |

| Compound 16 | 93 ± 3 | 2.6 ± 0.7 |

| Compound 17 | 23.1 ± 0.6 | 3.0 ± 1.2 |

| Compound 18 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.6 |

| Compound 19 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.3 |

| Compound 20 | 10.5 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 1.0 |

In another study, the aqueous-ethanolic and ethanolic extracts of the leaves of Vitex negundo, Hyptis suaveolens and roots of Decalepis hamiltonii were studied for their antiviral activity against CHIKV. The extracts were found to be effective against Asian strain of CHIKV with an IC50 of 15.62 μM [27]. This study led to an interesting finding as the aqueous ethanolic extract of Hyptis suaveolens found to be more selective towards inhibition of Asian strain of CHIKV when compared with ribavirin. This inhibitory activity might be due to the presence of pentacyclic triterpenoids as major constituent. Further study might focus on purification of active constituents to explore novel scaffolds with antichikungunya activity.

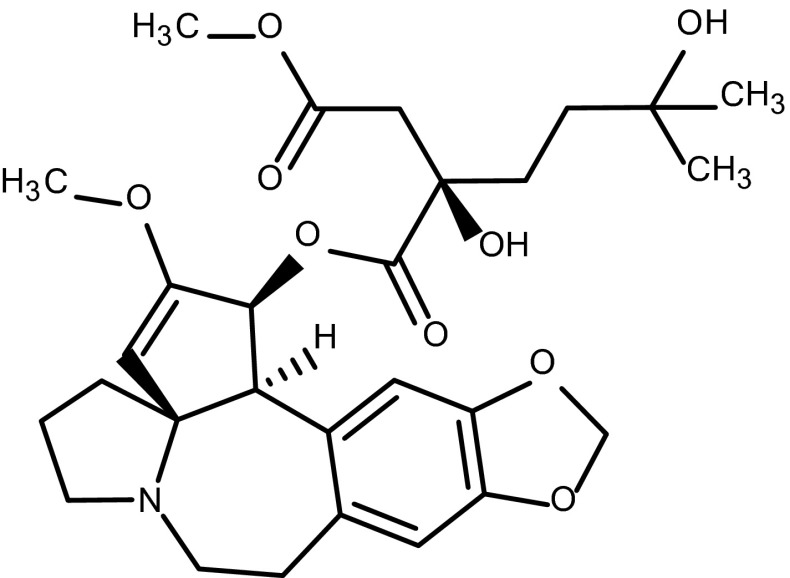

In a recent study, an immunofluorescence-based screening was performed to identify potential inhibitors of CHIKV using a highly purified natural product compound library. Out of these focused library 44 compounds exhibiting >70 % inhibition of CHIKV infection were identified as positive hits. Harringtonine (21), (Fig. 10), a cephalotaxine alkaloid, displayed an EC50 0.24 μM with minimal cytotoxicity [28]. In addition to its potent anti-CHIKV activity, time-of-addition studies, cotreatment assays etc. highlighted that harringtonine inhibit an early stage of CHIKV replication cycle by affecting viral protein expression [28]. The highly selective inhibitory nature of harringtonine as well as its inhibitory activity against sindbis virus, another alphavirus makes it a blockbuster candidate for further rational drug design efforts against CHIKV and other alphaviruses.

Fig. 10.

Structural representation of harringtonine (21), a cephalotaxine alkaloid which displayed significant inhibitory activity against CHIKV [28]

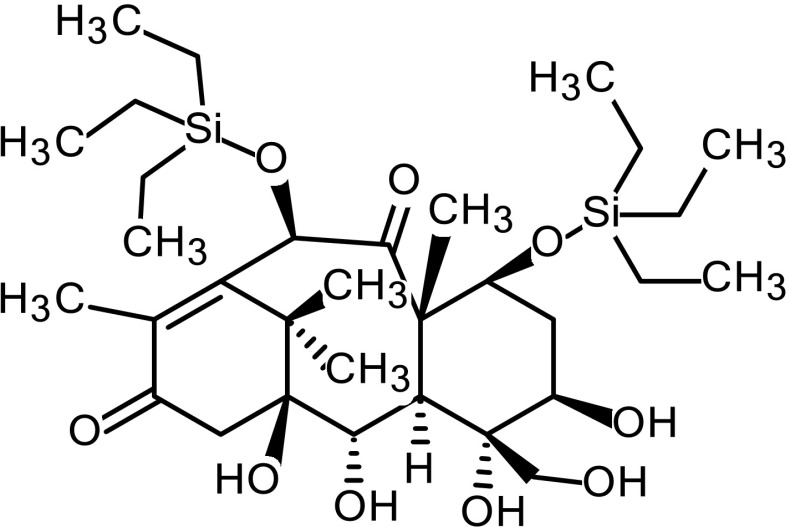

CHIKV NSP2 (non-structural protease 2) is one of the emerging target to discover novel inhibitors towards this emerging alphavirus. High throughput screening of 3040 molecules led to identification of a natural compound (22), (Fig. 11) which partially blocks NSP2 and CHIKV replication [29]. This study could further open up an opportunity to develop novel CHIKV NSP2 inhibitors from a natural product.

Fig. 11.

Chemical representation of compound 22 which displayed inhibitory activity against CHIKV NSP2 [29]

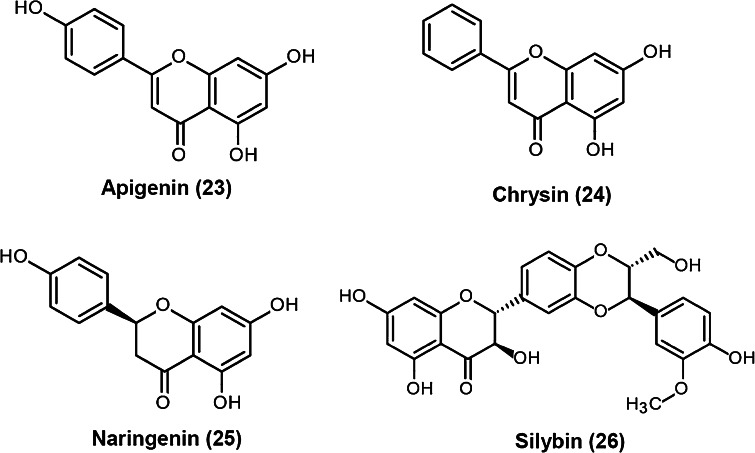

Also recently, a focused library of 356 compounds including natural products and clinically approved drugs were screened against EGFP and Rluc marker genes expressed by the CHIKV replicon. The 5, 7-dihydroxyflavones apigenin (23), chrysin (24), naringenin (25) and silybin (26) (Fig. 12) were found to suppress activities of EGFP and Rluc (Renilla luciferase) marker genes expressed by the CHIKV replicon (Table 4) [30]. Further these compounds also found to inhibit genome-replication of Semliki Forest virus (SFV), another alpha virus. Silybin (28) found to inhibit the entry of SFV into the host cell [30]. The antiviral activity of these compounds on Rluc gene confirmed that these molecules can inhibit genome replication of CHIKV and other alphaviruses [30]. Thus development of small molecule inhibitors using the pharmacophoric features of these compounds might lead to development of new replication inhibitor against CHIKV. Whereas, the structural and pharmacophoric feature of silybin (28) will be helpful in the development of entry inhibitors targeting CHIKV and other alphaviruses.

Fig. 12.

2D structural representations of compound 23-26 which displayed antiviral activities against EGFP and Rluc marker genes expressed by the CHIKV [30]

Table 4.

Antiviral activity of compound 25–28 against EGFP and Rluc marker genes expressed by the CHIKV [30]

| Natural products | EGFP IC50 (μM) | Rluc IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Apigenin (23) | 22.5 | 28.3 |

| Chrysin (24) | 46.8 | 50.2 |

| Naringenin (25) | 25.8 | 30.0 |

| Silybin (26) | 71.1 | 59.8 |

In a different report, two new daphnane diterpenoid orthoesters, trigocherrierin A (27), (Fig. 13) and trigocherriolide E were isolated from the leaves of Trigonostemon cherrieri exhibited anti-CHIKV activity in virus cell-based assay [31]. Trigocherrierin A displayed strongest anti-CHIKV activity with EC50 0.6 ± 0.1 μM and selectivity index (SI) = 71.7 [31].

Fig. 13.

2D structural representation of daphnane diterpenoid orthoester based CHIKV inhibitor, trigocherrierin A (27) [31]

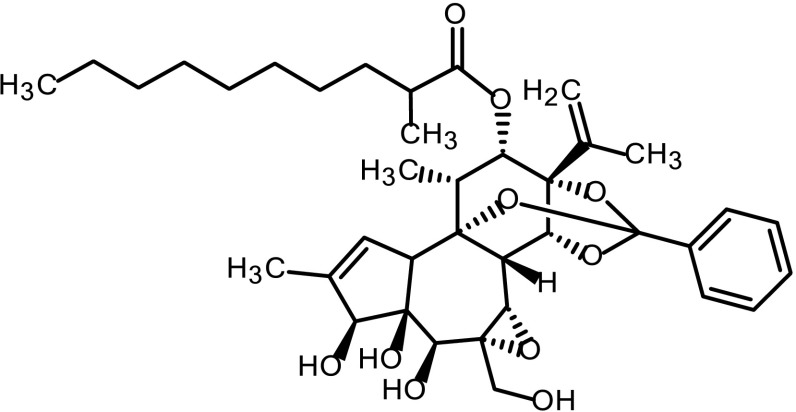

In another unique study, bioassay guided purification of an EtOAc extract of the whole plant of Euphorbia amygdaloides ssp. semiperfoliata led to identification of a new jatrophane ester (38), (Fig. 14) which exhibited potent and selective inhibitory activity against CHIKV with an EC50 of 0.76 μM [32]. Findings reported from this exploration can be further continued with structure activity relationship study to develop more potent anti-CHIKV inhibitors by providing correct substitutions on the jatrophane skeleton.

Fig. 14.

Structural representation of a jatrophane ester (28) which exhibited selective inhibitory activity against CHIKV [32]. “R” represents tiglyloxy (Tig) group

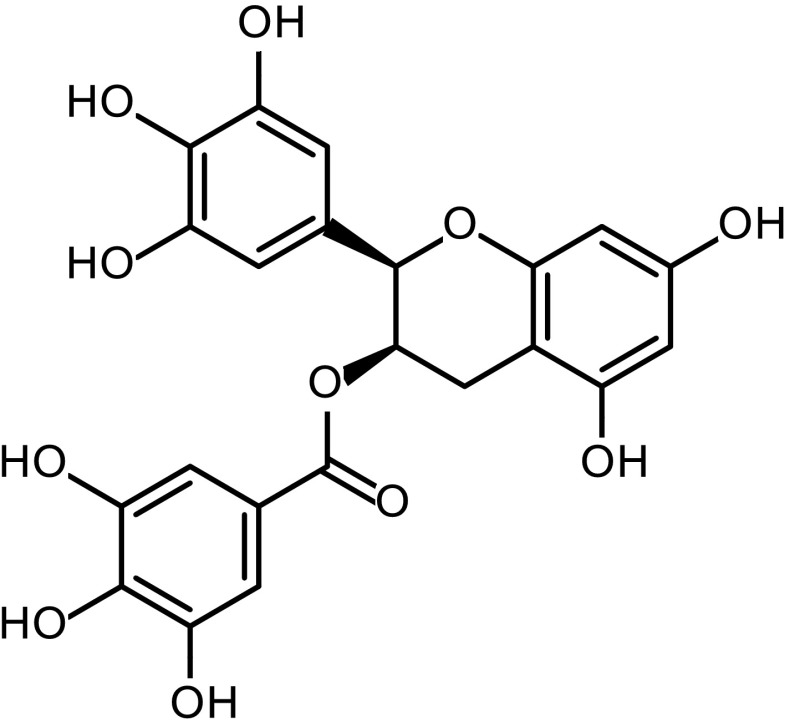

Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) (29), (Fig. 15), one of the major component of green tea displayed several biological activities such as HIV [33], cancer [34], fatigue syndrome [35] etc. Recent antiviral examination of EGCG displayed antiviral activity of EGCG against CHIKV. EGCG inhibited CHIKV infection in vitro by blocking the entry of CHIKV Env-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors and inhibiting CHIKV attachment [36]. Thus EGCG might be used as a structural template to design potent small molecule inhibitors targeting CHIKV.

Fig. 15.

2D structural feature of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (29)

Another antimalarial natural product, quinine (30), (Fig. 16) displayed significant anti-CHIKV activity with an IC50 0.1 µg/ml at a concentration less than chloroquine (IC50 = 1.1 µg/ml) [37].

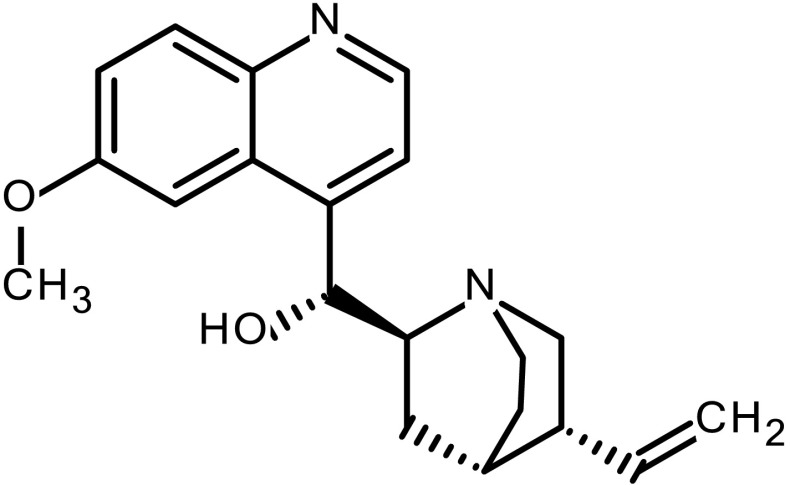

Fig. 16.

Chemical representation of quinine (30), an antimalarial compound which displayed anti-CHIKV activity

As a closing remark, the current efforts made to identify novel natural products against CHIKV is still insufficient and further research is highly encouraged towards either the discovery of novel leads or optimization of the currently identified compounds. This report demonstrated various potential chemical entities/scaffolds from natural sources; such information could assist medicinal chemists towards the design of optimized and more potent inhibitors against CHIKV.

Conclusions

During last 3 years, exploring several natural products as potential antivirals targeting CHIKV has gradually increased. Several interesting scaffolds with moderate to potent activity against CHIKV were reported, however, due to the neglected nature of the disease, less efforts were reported in order to optimize novel scaffolds identified from natural products in order to develop potent and selective inhibitors with an increased potency and ADME profile. Furthermore, the majority of the inhibitors were identified using in vitro cell-based assays, hence, identification of enzyme specific inhibitor targeting CHIKV is still a major challenge. As a result, till date, a very small amount of chemical space containing natural products have been explored in order to identify potent anti-CHIKV agents. With the advancement in assay techniques, future efforts might be directed towards identification of novel anti-CHIKV agents targeting specific structural/non-structural proteins using novel scaffolds identified from natural products. Natural product inspired small molecule inhibitors might prove a cornerstone in the hectic development process of drug candidates against CHIKV due to their low toxicity profile. Using modern state of the art computational approach the structural and pharmacophoric features of active natural products can be used in order to develop target specific inhibitors against CHIKV. The use of GRID computing and collaborative drug discovery efforts will play a crucial role in this process in order to speed up the discovery process. In conclusion, more effort from researchers towards the development of antiviral agents targeting CHIKV from natural products is highly encouraged. More advanced computer-assisted and molecular modelling approaches augmented with analytical and experimental techniques should be applied in order to optimize the activity of the currently discovered natural compounds.

Acknowledgements

SB wish to thank School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal for providing financial support through scholarship in the academic year 2013/14.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare there is no potential conflicts of interests.

Contributor Information

Soumendranath Bhakat, Email: bhakatsoumendranath@gmail.com, https://cbiores.wordpress.com/.

Mahmoud E. S. Soliman, Phone: +27 031 260 7413, Email: soliman@ukzn.ac.za, http://soliman.ukzn.ac.za/

References

- 1.Rashad AA, Mahalingam S, Keller PA. Chikungunya virus: emerging targets and new opportunities for medicinal chemistry. J Med Chem. 2014;57:1147–1166. doi: 10.1021/jm400460d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belov GA. Modulation of lipid synthesis and trafficking pathways by picornaviruses. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;9:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirneisen K, Reith JL, Wei J, Hoover DG, Hicks DT, Pivarnik LF, Kniel KE. Comparison of pressure inactivation of caliciviruses and picornaviruses in a model food system. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2014;26:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2014.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parashar D, Cherian S. Antiviral perspectives for chikungunya virus. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:631642. doi: 10.1155/2014/631642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koehn FE, Carter GT. The evolving role of natural products in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:206–220. doi: 10.1038/nrd1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li JW, Vederas JC. Drug discovery and natural products: end of an era or an endless frontier? Science. 2009;325:161–165. doi: 10.1126/science.1168243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molinari G. Natural products in drug discovery: present status and perspectives. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;655:13–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1132-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molinari G. Natural products in drug discovery: present status and perspectives. In: Guzman CA, Feuerstein GZ, editors. Pharmaceutical biotechnology. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li JWH, Vederas JC. Drug discovery and natural products: end of an era or an endless frontier? Science. 2009;325:161–165. doi: 10.1126/science.1168243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teixeira RR, Pereira WL, da Silveira Costa, Oliveira AF, da Silva AM, de Oliveira AS, da Silva ML, da Silva CC, de Paula SO. Natural products as source of potential dengue antivirals. Molecules. 2014;19:8151–8176. doi: 10.3390/molecules19068151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S. Artemisinin, promising lead natural product for various drug developments. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2007;7:411–422. doi: 10.2174/138955707780363837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guantai E, Chibale K. How can natural products serve as a viable source of lead compounds for the development of new/novel anti-malarials? Malar J. 2011;10:S2. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhakat S, Karubiu W, Jayaprakash V, Soliman ME. A perspective on targeting non-structural proteins to combat neglected tropical diseases: dengue, West Nile and chikungunya viruses. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;6:677–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Case DA, Cheatham TE, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM, Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods RJ. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen PTV, Yu H, Keller PA. Discovery of in silico hits targeting the nsP3 macro domain of chikungunya virus. J Mol Model. 2014;20:2216. doi: 10.1007/s00894-014-2216-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malet H, Coutard B, Jamal S, Dutartre H, Papageorgiou N, Neuvonen M, Ahola T, Forrester N, Gould EA, Lafitte D, Ferron F, Lescar J, Gorbalenya AE, de Lamballerie X, Canard B. The crystal structures of chikungunya and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus nsP3 Macro domains define a conserved adenosine binding pocket. J Virol. 2009;83:6534–6545. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00189-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voss JE, Vaney M-C, Duquerroy S, Vonrhein C, Girard-Blanc C, Crublet E, Thompson A, Bricogne G, Rey FA. Glycoprotein organization of chikungunya virus particles revealed by X-ray crystallography. Nature. 2010;468:709–712. doi: 10.1038/nature09555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mann J. Natural products in cancer chemotherapy: past, present and future. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:143–148. doi: 10.1038/nrc723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mondal S, Bandyopadhyay S, Ghosh MK, Mukhopadhyay S, Roy S, Mandal C. Natural products: promising resources for cancer drug discovery. Anti Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2012;12:49–75. doi: 10.2174/187152012798764697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells T. Natural products as starting points for future anti-malarial therapies: going back to our roots? Malar J. 2011;10:S3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-S1-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh IP, Bodiwala HS. Recent advances in anti-HIV natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27:1781–1800. doi: 10.1039/c0np00025f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourjot M, Delang L, Van Hung N, Neyts J, Gueritte F, Leyssen P, Litaudon M. Prostratin and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate are potent and selective inhibitors of chikungunya virus replication. J Nat Prod. 2012;75:2183–2187. doi: 10.1021/np300637t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chowdhury IH, Koyanagi Y, Kobayashi S, Hamamoto Y, Yoshiyama H, Yoshida T, Yamamoto N. The phorbol ester TPA strongly inhibits HIV-1-induced syncytia formation but enhances virus production: possible involvement of protein kinase C pathway. Virology. 1990;176:126–132. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90237-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourjot M, Leyssen P, Eydoux C, Guillemot J-C, Canard B, Rasoanaivo P, Gueritte F, Litaudon M. Chemical constituents of Anacolosa pervilleana and their antiviral activities. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:1076–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corlay N, Delang L, Girard-Valenciennes E, Neyts J, Clerc P, Smadja J, Gueritte F, Leyssen P, Litaudon M. Tigliane diterpenes from Croton mauritianus as inhibitors of chikungunya virus replication. Fitoterapia. 2014;97:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allard P-M, Leyssen P, Martin M-T, Bourjot M, Dumontet V, Eydoux C, Guillemot J-C, Canard B, Poullain C, Gueritte F, Litaudon M. Antiviral chlorinated daphnane diterpenoid orthoesters from the bark and wood of Trigonostemon cherrieri. Phytochemistry. 2012;84:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kothandan S, Swaminathan R. Evaluation of in vitro antiviral activity of Vitex Negundo L., Hyptis suaveolens (L) poit., Decalepis hamiltonii Wight & Arn., to chikungunya virus. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2014;4(Supplement 1):S111–S115. doi: 10.1016/S2222-1808(14)60424-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaur P, Thiruchelvan M, Lee RCH, Chen H, Chen KC, Ng ML, Chu JJH. Inhibition of chikungunya virus replication by harringtonine, a novel antiviral that suppresses viral protein expression. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:155–167. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01467-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucas-Hourani M, Lupan A, Despres P, Thoret S, Pamlard O, Dubois J, Guillou C, Tangy F, Vidalain P-O, Munier-Lehmann H. A phenotypic assay to identify chikungunya virus inhibitors targeting the nonstructural protein nsP2. J Biomol Screen. 2013;18:172–179. doi: 10.1177/1087057112460091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pohjala L, Utt A, Varjak M, Lulla A, Merits A, Ahola T, Tammela P. Inhibitors of alphavirus entry and replication identified with a stable chikungunya replicon cell line and virus-based assays. Plos One. 2011;6:e28923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bourjot M, Leyssen P, Neyts J, Dumontet V, Litaudon M. Trigocherrierin a, a potent inhibitor of chikungunya virus replication. Molecules. 2014;19:3617–3627. doi: 10.3390/molecules19033617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nothias-Scaglia L-F, Retailleau P, Paolini J, Pannecouque C, Neyts J, Dumontet V, Roussi F, Leyssen P, Costa J, Litaudon M. Jatrophane diterpenes as inhibitors of chikungunya virus replication: structure-activity relationship and discovery of a potent lead. J Nat Prod. 2014;77:1505–1512. doi: 10.1021/np500271u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williamson MP, McCormick TG, Nance CL, Shearer WT. Epigallocatechin gallate, the main polyphenol in green tea, binds to the T-cell receptor, CD4: potential for HIV-1 therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:1369–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen D, Wan SB, Yang H, Yuan J, Chan TH, Dou QP (2011) EGCG, green tea polyphenols and their synthetic analogs and prodrugs for human cancer prevention and treatment, In: Makowski GS (eds) Advances in clinical chemistry, vol 53, pp 155–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Sachdeva AK, Kuhad A, Chopra K. Epigallocatechin gallate ameliorates behavioral and biochemical deficits in rat model of load-induced chronic fatigue syndrome. Brain Res Bull. 2011;86:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weber C, Sliva K, von Rhein C, Kümmerer BM, Schnierle BS The green tea catechin, epigallocatechin gallate inhibits chikungunya virus infection, Antiviral Res [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.de Lamballerie X, Ninove L, Charrel RN. Antiviral treatment of chikungunya virus infection. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9:101–104. doi: 10.2174/187152609787847712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]