Abstract

Evaluation of cancer genomes in global context is of great interest in light of changing ethnic distribution of the world population. We focused our study on men of African ancestry because of their disproportionately higher rate of prostate cancer (CaP) incidence and mortality. We present a systematic whole genome analyses, revealing alterations that differentiate African American (AA) and Caucasian American (CA) CaP genomes. We discovered a recurrent deletion on chromosome 3q13.31 centering on the LSAMP locus that was prevalent in tumors from AA men (cumulative analyses of 435 patients: whole genome sequence, 14; FISH evaluations, 101; and SNP array, 320 patients). Notably, carriers of this deletion experienced more rapid disease progression. In contrast, PTEN and ERG common driver alterations in CaP were significantly lower in AA prostate tumors compared to prostate tumors from CA. Moreover, the frequency of inter-chromosomal rearrangements was significantly higher in AA than CA tumors. These findings reveal differentially distributed somatic mutations in CaP across ancestral groups, which have implications for precision medicine strategies.

Keywords: African American, Prostate cancer, Genome, LSAMP, ERG, PTEN

Highlights

-

•

Distinct genomic alterations were defined in prostate cancers of African American (AA) and Caucasian American (CA) men.

-

•

A novel prevalent deletion of the LSAMP locus associated with prostate cancer recurrence in AA prostate cancers

-

•

Focused evaluations of cancer genomes in the context of ethnicity have implications in enhancing precision medicine.

Men of African ancestry experience a disproportionately higher rate of prostate cancer (CaP) incidence and mortality. However, most prostate cancer genome evaluations thus far have focused on men of European ancestry. This report highlights a new recurrent genomic alteration of LSAMP locus in African American prostate cancers. Further, significant differences of two established prostate cancer driver genes, ERG and PTEN, were affirmed. This study conveys the need for careful evaluations of cancer genomes in global context with important implications for precision medicine strategies.

1. Introduction

Men of African ancestry have a significantly higher rate of prostate cancer (CaP) incidence and mortality in the United States and globally (Siegel et al., 2015). Accumulating evidence from our group and others support the contention that biological and genetic alterations differ in prevalence between AA and CA CaP (Chornokur et al., 2011, Farrell et al., 2013, Martin et al., 2013, Pomerantz and Freedman, 2011, Powell et al., 2010). Recently, many tumor sequencing studies have highlighted frequent alterations of ERG, PTEN and SPOP genes in early stages of CaP (Baca et al., 2013, Barbieri et al., 2012, Berger et al., 2011, Boutros et al., 2015, Grasso et al., 2012, Kumar et al., 2011, Taylor et al., 2010, Weischenfeldt et al., 2013) and of the androgen receptor (AR), p53 and PIK3CB and other genes in metastatic CaP or castration resistant prostate cancer (Robinson et al., 2015). However, the majority of these studies were performed in men of European ancestry. Motivated by the observation that the well-described TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion significantly differs across ancestral populations (Blattner et al., 2014, Farrell et al., 2014, Khani et al., 2014, Magi-Galluzzi et al., 2011, Rosen et al., 2012) we sought to perform comprehensive whole genome analyses of prostate cancers from AA and CA men.

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Prostate cancer specimens, sample preparation and quality control

Prostate cancer samples selected for this study were archived specimens under IRB approved protocol from patients undergoing radical prostatectomy treatment at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC). Clinically localized primary prostate tumors were selected for whole genome sequencing from seven African American (AA) and seven Caucasian American (CA) patients. Histologically defined tumors with primary Gleason pattern 3 were manually dissected under microscope from frozen OCT-embedded 6 μm prostate tissue sections with 80–95% tumor cell content (Table 1a). Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E)-stained tissue sections were reviewed by I.A.S. to determine Gleason score and percentage composition of tumor at the site selected for DNA extraction. DNA was purified from the isolated tissues, as well as from peripheral blood lymphocytes (normal DNA control) of the corresponding patients using DNeasy Blood and Tissue DNA isolation kit (Qiagen). DNA samples were subjected to extensive quality control to verify structural integrity by agarose gel-electophoresis. ERG fusion and expression status were determined by RT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 1.) and by immunohistochemistry (Furusato et al., 2010, Hu et al., 2008).

Table 1a.

Patient-specific features included in the study (patient number: GP02-18; Race: African American: AA, Caucasian American: CA; prostate specific antigen: PSA).

| Summary of information on patient and tumor | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-specific features |

Specific features of the sequenced tumors |

||||||||

| Sample ID | Race | Age | Pathologic Gleason score | Pathologic stage | Serum PSA (ng/ml) | TMPRSS2-ERG Status | Tumor Gleason score | Gleason 3 pattern of tumor (%) | Estimated tumor purity (%) |

| GP02 | AA | 68 | 7 (4 + 3) | T3C | 7 | − | 6 (3 + 3) | 100 | 80 |

| GP04 | AA | 51 | 7 (3 + 4) | T3A | 8.3 | − | 7 (3 + 4) | 95 | 80 |

| GP10 | AA | 53 | 7 (3 + 4) | T3C | 6.5 | − | 7 (3 + 4) | 95 | 90 |

| GP18 | AA | 48 | 7 (3 + 4) | T3A | 3.7 | − | 6 (3 + 3) | 100 | 80 |

| GP12 | AA | 52 | 6 (3 + 3) | TX | 3.8 | + | 6 (3 + 3) | 100 | 90 |

| GP13 | AA | 59 | 6 (3 + 3) | T2C | 7.7 | + | 7 (3 + 4) | 100 | 85 |

| GP15 | AA | 44 | 6 (3 + 3) | TX | 9.1 | + | 6 (3 + 3) | 92 | 80 |

| GP06 | CA | 58 | 7 (4 + 3) | T3C | 7.4 | − | 7 (3 + 4) | 100 | 95 |

| GP11 | CA | 64 | 7 (3 + 4) | T2C | 11.6 | − | 6 (3 + 3) | 95 | 90 |

| GP16 | CA | 49 | 7 (4 + 3) | T3A | 22.7 | − | 7 (3 + 4) | 85 | 90 |

| GP01 | CA | 64 | 7 (3 + 4) | T3B | 11.4 | + | 7 (3 + 4) | 95 | 80 |

| GP07 | CA | 69 | 6 (3 + 3) | TX | 4 | + | 6 (3 + 3) | 100 | 90 |

| GP09 | CA | 60 | 6 (3 + 3) | TX | 2.8 | + | 7 (3 + 4) | 97 | 80 |

| GP17 | CA | 67 | 7 (3 + 4) | T3A | 7.4 | + | 7 (3 + 4) | 95 | 80 |

2.2. Validation of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status by RT-PCR

TMPRSS2-ERG fusion positive cases were validated by RT-PCR. Approximately 40 ng of patient mRNA were reverse transcribed using Sensiscript (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) in the presence of random hexamer primers at 37 °C for 1 h. An additional reaction without reverse transcriptase was set up as control. PCR amplification was performed with 1.5 μl (0.5–1 μg) of cDNA from the reverse transcriptase reaction, TMPRSS2 and ERG primers as described in Supplementary Table 1 using AmpliTaq Gold (Life technologies, Grand Island, NY) as recommended by the manufacturer. DNA was first melted at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 amplification cycles (melting at 94 °C, 40 s; annealing at 55 °C, 40 s; and extension at 72 °C, 1 min) and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis on a 2% TBE-agarose gel (Supplementary Fig. 1).

2.3. Whole genome sequencing

DNA samples were processed using the Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation kit, starting with 500 ng input and resulting in an average insert size of 310 bp. Cluster amplification, linearization, blocking and hybridization to the Read 1 sequencing primer were carried out on a cBOT. Following the first sequencing read, flow cells were held in situ, and clusters were prepared for Read2 sequencing using the Illumina Paired-End Module. Paired-end sequence reads of 101 bases were generated using the Genome Analyzer IIX with v5 SBS reagent kits, as described in the Illumina Genome Analyzer operating manual. Data were processed using Real Time Analysis (RTA).

2.4. Processing pipeline for analyses of whole genome sequence data

Germline samples were sequenced to at least 30 × depth followed by alignment and variant calling using the ELANDv2e algorithm in Consensus Assessment of Sequence And VAriation (CASAVA v 1.8) pipeline. DNA derived from tumors was sequenced to at least 30-fold haploid coverage. After alignment to reference genome Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37 (GRCh37/hg19) and subtraction of the germline genome from tumor sequences, somatic variants were called using Strelka (for single nucleotide variants [SNVs] and Indels), Genomatix Mapper (www.genomatix.de) and BreakDancer (for structural variations [SVs]) (Chen et al., 2009), cn.MOPs (Klambauer et al., 2012) and Control-FREEC (Boeva et al., 2012) (for copy number variations [CNVs]). Somatic SNVs (one base-pair point mutations detected by single reads) initially called using Strelka (Saunders et al., 2012) (Supplementary Table 2) were validated using four other variant calling tools: Varscan2 (Koboldt et al., 2012), MuTect (Cibulskis et al., 2013, Roth et al., 2012) and Somatic Sniper (Larson et al., 2012) (Supplementary Table 3). SNVs that were detected by at least three variant calling tools were designated as high confidence SNVs (Wang et al., 2013) (Supplementary Table 4). SNVs that resulted in missense mutations, nonsense mutations (stop gain) and mutations affecting splice sites are presented in Supplementary Table 5. Indels, defined as small insertion and deletions of up to 300 bps, detected by single reads that were called by Strelka are listed in Supplementary Table 6. Somatic SVs, defined as large deletions, inversions, insertions, translocations detected by anomalous paired-end reads, were called by Genomatix Mapper and BreakDancer (www.genomatix.de). Genes with intergenic breakpoints, inversion and deletions that were called are presented in Supplementary Table 7. Structural variation breakpoints for ERG, LSAMP and PTEN that were detected by whole genome sequencing are tabulated in Supplementary Table 8. A subset of base-pair mutations and rearrangements were validated using Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Fig. 2) in order to assess the specificity of the detection algorithms (primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1).

2.5. Detection of transcripts from ZBTB20 and LSAMP promoters by 5′ RACE

mRNA transcripts initiating from ZBTB20 and LSAMP promoters were detected by 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) (Harvey and Darlison, 1991, Shi and Kaminskyj, 2000) using the SMARTer® RACE 5′/3′ kit (Clontech). In a coupled reaction, 10 ng of total RNA from patients reverse transcribed in the presence SMARTer IIA oligo into first-strand cDNA incorporated with the SMARTer sequence at the 5′ end. The first-strand cDNA is amplified in the presence of the universal primer and gene specific 5′ primers using two cycles of 94 °C for 30 s and 68 °C for 3 min followed by 28 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 3 min. The absence of distinct bands prompted another round of amplification using nested primers (primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1). Amplified DNA products were analyzed by using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent) DNA prior to separation on agarose gel. Distinct bands were excised (10 for GP02 and 18 for GP10), gel purified, subcloned into pC-Blunt II-TOPO plasmids and transformed into One Shot TOP10 E. coli (Life Technologies). Six colonies from each transformation were picked for the isolation of plasmid DNA and analyzed by Sanger sequencing. The types of splice variants and how frequently each was detected are described in Supplementary Fig. 3.

2.6. Principal component analysis (PCA)

The ancestry of patients for the CPDR cohort of seven AA and seven CA patients together with the patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network et al., 2013) were confirmed by principal component analysis using the EIGENSTRAT method from the EIGENSOFT package (Price et al., 2006). For the PCA of the 14 patients assessed by whole genome sequencing, 39,867 SNP markers were extracted from whole genome sequencing data, SNPs with less than 20 × coverage were filtered out and the genotypes are inferred from alternate allele frequency (0 ~ 0.2: ref./ref.; 0.2 ~ 0.8: ref./alt; 0.8 ~ 1: alt/alt). By applying the sampling criteria to filter out SNPs with batch difference, total of 1353 SNPs were selected. The principal components were computed from a combined matrix of these 1353 SNPs genotype derived from the WGS data of the 7AA and 7CA samples and from the SNP array data from 415 HapMap Phase II reference samples representing three distinct reference populations: Northern and Western European ancestry (CEU), Africans of Yoruba ancestry in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI), and Americans of African ancestry in Southwest of the United States (ASW).The computed ancestry of the seven AA and seven CA patients are shown to localize with ASW/YRI and with CEU populations, respectively, confirming identical classification to self-reported ethnicity (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The ancestry the TCGA cohort were established by using a CNV (SNP) array dataset (broad.mit.edu_PRAD.Genome_Wide_SNP_6.Level_3.184.2019.0) that contains genotype data determined by using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0. The principal components used to determine the ancestry of this cohort were computed from a combined matrix consisting of 13,541 SNPs or genotypes of 320 TCGA “cases” and 552 HapMap Phase II “controls” representing four reference populations (Han Chinese in Beijing, China [CHB] in addition to CEU, YRI and ASW). The 13541 SNPs were filtered from a total of 39,867 SNPs based on having an observed minor allele frequency greater than 0.05, a significant diversity among reference populations (Krusal Wallis test p < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction), and no significant batch difference for the allele frequency between TCGA samples and HapMap Phase II samples. EIGENSTRAT was used to calculate the first two principal components corresponding to the two largest eigenvalues. TCGA cases that show similar principal scores to the control HapMap samples were assigned to the same population as that of the HapMap samples from the same cluster. This stratified the TCGA cases into 41 African Americans and 279 Caucasian Americans (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 9).

2.7. Frequency of LSAMP and PTEN deletions and TMPRSS2-ERG fusion in the TCGA SNP array data

The TCGA cohort with established ancestry provides an independent patient cohort to assess the frequency of LSAMP and PTEN deletions and TMPRSS2-ERG alterations in prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD). To determine the deletions or copy number changes within LSAMP (3q13.31), PTEN and TMPRSS2-ERG loci, raw SNP data were first normalized using the CRMA v2 method from the AROMA package (Bengtsson et al., 2009). Integer copy number inference was performed with the ASCAT software suite (Van Loo et al., 2012). Copy numbers were normalized by chromosome-wide medians before the identification of deleted loci. Data from SNP arrays that failed to converge to an acceptable solution were omitted from analysis.

Principal component analysis was applied from the EIGENSTRAT package (Price et al., 2006) to establish the ancestry of patients (Supplementary Fig. 5).

2.8. Validation of LSAMP and PTEN deletion frequencies by interphase FISH assay

FISH analysis (Hopman et al., 1991) for the detection of deletions at the PTEN (Yoshimoto et al., 2006) and ZBTB20-LSAMP locus was performed on whole mounted sections and on prostate tumor tissue microarrays (TMAs) constructed from a cohort of radical prostatectomy specimens as described in Merseburger et al. (2003). A PTEN locus-specific probe was generated by selecting a combination of clones within the peak region of common PTEN deletions near 10q23.3. These clones were tested in an iterative trial-and-error process to optimize signal intensity and specificity, resulting in a probe matching ca. 450 kbp covering PTEN and adjacent genomic sequences (Supplementary Fig. 6a). A control probe derived from chromosome 10-specific alpha satellite centromeric DNA, labeled with CytoGreen fluorescent dye was used for chromosome 10 counting. A ZBTB20-LSAMP locus-specific probe was constructed from bacterial artificial chromosome clones obtained from a commercial vendor (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Clones were cultured in LB medium prior to DNA isolation using standard procedures and labeling with CytoOrange fluorescent dye. Clone combinations were selected in the core deleted region and tested in an iterative trial-and-error process to optimize signal intensity and specificity, resulting in a probe matching ca. 500 kbp of genomic sequence between the ZBTB20 and LSAMP loci, including the complete GAP43 gene (Supplementary Fig. 6b). A second, LSAMP-centered probe was designed using the same process, resulting in a probe containing ca. 600 kbp of genomic sequence centered on and covering the entire LSAMP gene (Supplementary Fig. 6c). A probe derived from chromosome 3-specific alpha satellite centromeric DNA, labeled with CytoGreen fluorescent dye was used as a control. Before use on tissue samples, locus-specific and control probes were mapped to normal human peripheral blood lymphocyte metaphases to confirm location and performance in interphase nuclei. Tumor cells with at least two centromeres were counted. Numbers of centromeres and LSAMP/PTEN signals were compared to determine whether cells were homozygous or heterozygous for this locus. Deletions were called when more than 75% of evaluable tumor cells showed loss of allele. Focal deletions were called when more than 25% of evaluable tumor cells showed loss of allele or when more than 50% evaluable tumor cells in each gland of a cluster of two or three tumor glands showed loss of allele. Benign prostatic glands and stroma served as built in control.

3. Results

3.1. Tumor and whole genome sequencing data of African American and Caucasian American prostate cancer patients

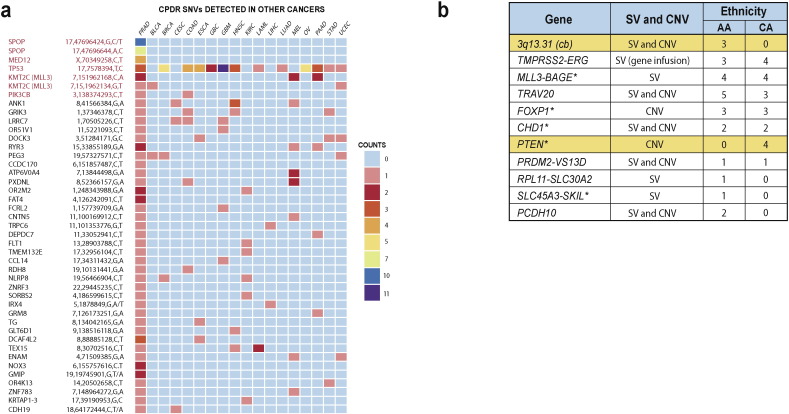

We focused this study on early stage CaP (Gleason score 6 or 7 with primary pattern, 3) because it represents the majority of newly diagnosed prostate cancers in the United States (Siegel et al., 2015). We evaluated histologically defined manually dissected tumor specimens (80–95% tumor purity, primary Gleason pattern 3) and matched normal prostate tissue or peripheral blood lymphocytes from seven AA and seven CA patients, yielding a total of 28 whole genome sequences (Table 1a). The overall landscape of primary CaP genomic alterations (single nucleotide variations [SNVs], structural variation [SVs], and indels) from this study revealed similarities, as well as differences compared to previous reports (Barbieri et al., 2012, Berger et al., 2011, Grasso et al., 2012) (Table 1b; Fig. 1a and b; Supplementary Tables 2–8, 11).

Table 1b.

Characteristics of the analyzed prostate tumor and matched normal blood whole genomes.

| Characteristics of the analyzed prostate tumor and matched normal blood whole genomes | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample ID | Race | TMPRSS2-ERG status | Tumor bases sequenced (Gb) | Tumor haploid coverage | Normal bases sequenced (Gb) | Normal haploid coverage | All somatic SNVs | Non-silent SNVs | Mutation (SNV) rate per Mb | All somatic indels | All somatic SVs | All somatic CNVs |

| GP02 | AA | - | 114.7 | 37.8 | 112.2 | 95.6 | 2331 | 25 | 0.82 | 528 | 284 | 31 |

| GP04 | AA | - | 116.7 | 38.3 | 111.8 | 95.6 | 2800 | 25 | 0.98 | 701 | 429 | 40 |

| GP10 | AA | - | 118.5 | 39.2 | 111.6 | 95.7 | 2570 | 23 | 0.90 | 602 | 242 | 5 |

| GP18 | AA | - | 116.2 | 38.6 | 102.4 | 95.7 | 1976 | 20 | 0.69 | 431 | 251 | 7 |

| GP12 | AA | + | 112.6 | 37.2 | 117.7 | 95.6 | 2069 | 8 | 0.72 | 452 | 286 | 15 |

| GP13 | AA | + | 107.6 | 34.9 | 113.4 | 95.3 | 1934 | 13 | 0.68 | 435 | 164 | 4 |

| GP15 | AA | + | 114.2 | 38.1 | 108.1 | 95.6 | 2167 | 12 | 0.76 | 455 | 399 | 6 |

| GP06 | CA | - | 123.5 | 41.0 | 113.3 | 95.8 | 3635 | 38 | 1.27 | 667 | 148 | 36 |

| GP11 | CA | - | 107.5 | 35.0 | 109.8 | 95.4 | 2158 | 19 | 0.75 | 382 | 130 | 9 |

| GP16 | CA | - | 108.6 | 36.0 | 115.3 | 95.4 | 2939 | 26 | 1.03 | 677 | 240 | 43 |

| GP01 | CA | + | 117.5 | 39.0 | 104.0 | 95.7 | 6652 | 38 | 2.33 | 1105 | 187 | 10 |

| GP07 | CA | + | 106.5 | 34.9 | 121.9 | 95.4 | 2113 | 16 | 0.74 | 359 | 102 | 4 |

| GP09 | CA | + | 111.9 | 37.2 | 105.3 | 95.5 | 2907 | 15 | 1.02 | 511 | 165 | 17 |

| GP17 | CA | + | 111.3 | 36.6 | 112.2 | 95.6 | 3238 | 35 | 1.13 | 551 | 186 | 16 |

| Mean | 113.4 | 37.4 | 111.4 | 95.6 | 2821 | 22 | 1.00 | 561 | 230 | 17 | ||

| Total | 1587.3 | 523.8 | 1559.0 | 1337.9 | 39489 | 313 | 13.82 | 7856 | 3213 | 243 | ||

Fig. 1.

Similarities and differences in the landscape of primary prostate cancer genomic alterations between AA and CA men. (a) Mutations identified in AA and CA genomes in this study are also found at higher frequencies in the TCGA prostate cancer mutation dataset (highlighted in red). (b) Affected loci or cytogenetic band (cb) of high confidence somatic structural variations (SV) and copy number variations (CNV) identified in AA or in CA genomes or in both ethnic group. Asterisk marks previously published somatic alterations.

3.2. Association of LSAMP locus rearrangements with African American ethnicity

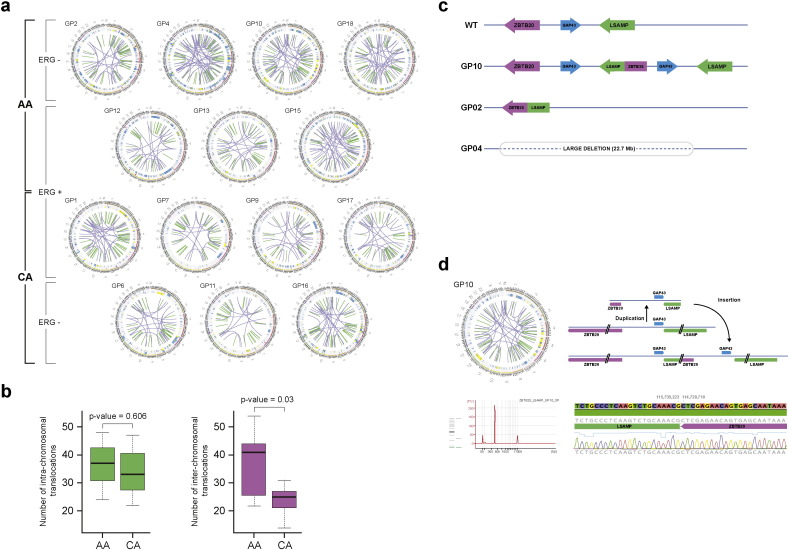

Among novel observations, significantly higher numbers of inter-chromosomal rearrangements (p = 0.03) (Fig. 2a and b) and exclusive association of chromosome 3q13.31 locus rearrangement/deletion were identified in AA CaP genomes (Fig. 1b). In depth analyses of the 3q13.31 region showed two tumors with 23 Mb (GP4) and 1 Mb (GP2) deletions in the ZBTB20-LSAMP region (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Table 8). In the third case (GP10) this locus was rearranged by duplication resulting in a novel fusion junction that was confirmed by RNA-Seq data, targeted genomic sequencing and by 5′-RACE of the resulting fusion products (Fig. 2d, and Supplementary Fig. 3). All of the three AA patients with the involvement of the 3q13.31 locus showed recurrence (two biochemical recurrences and one metastasis) after prostatectomy.

Fig. 2.

Significantly higher number of inter-chromosomal rearrangements and exclusive association of chromosome LSAMP deletion/rearrangement in prostate cancer of AA men. (a) Circos plots of AA and CA whole genomes indicate chromoplexy characteristic of prostate cancer genomes. Inter-chromosomal translocations are marked with purple. Inter-chromosomal rearrangements are marked by green. (b) Inter-chromosomal translocations are significantly more frequent events in AA prostate cancer genomes. (c) Wild type (WT), LSAMP locus rearrangements by large deletion (patient GP04), small deletion (GP2) or by duplication generating a ZBTB20-LSAMP gene fusion (GP10). (d) Confirmation of ZBTB20-LSAMP gene fusion by Sanger sequencing of the genomic fusion junction.

3.3. LSAMP deletion in prostate cancer is a hallmark of rapid disease progression in African American men

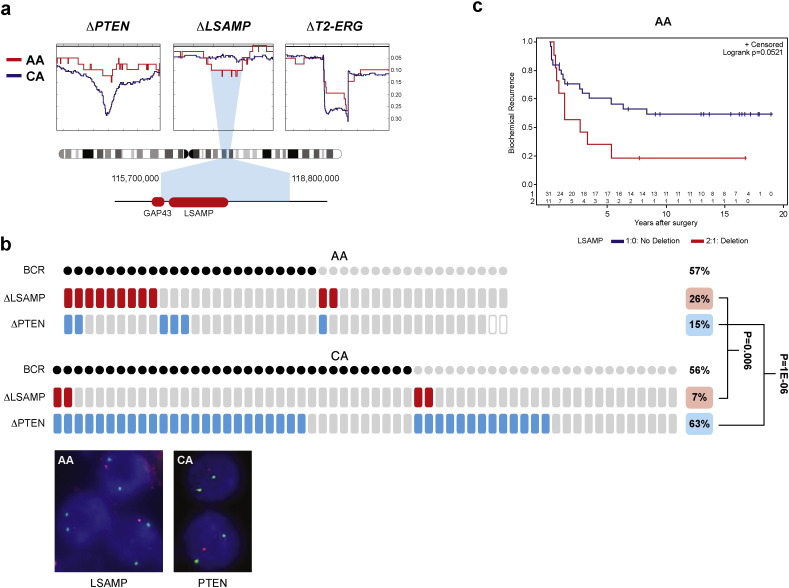

To validate the deleted locus in CaP and its frequency difference, we analyzed TCGA prostate cancer SNP data (The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network et al., 2013). Of note, LSAMP locus centered deletions were detected in 27% (11 of 41) of AA tumors and in 13% (37 of 279) of CA tumors (p = 0.023), strongly supporting our initial WGS observations (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 9). We further probed the deleted locus using an LSAMP -centered probe in fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) assay in tissue microarrays comprising of multi sampled cores from a matched cohort of 42 AA (174 cores) and 59 CA (299 cores) patients (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 6). Consistent with our initial result, tumors harboring LSAMP deletion were more prevalent in AA vs. CA cases (26% vs. 7%, p = 0.007). Moreover, LSAMP deletion in AA men correlated with biochemical recurrence (BCR) and with pT3 tumors (p = 0.05) (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Table 10).

Fig. 3.

LSAMP deletion is more prevalent in AA tumors correlating with rapid disease progression. Moreover, (a) SNP deletion frequencies in AA (red, n = 41) and CA (blue, n = 279) genomes indicate LSAMP within the minimum deletion region of 3q13.31 in AA patients. PTEN and TMPRSS2-ERG (T2-ERG) loci are more often deleted in CA patients. Deletion frequencies are marked on the Y-axis. (b) LSAMP deletion (red tiles) is associated with biochemical recurrence (BCR, marked by black dots) and is a more frequent event in AA patients. PTEN deletion (blue tiles) is a rare event in AA patients. Inset shows representative images of FISH assays of hemizygous LSAMP (red) and PTEN (red) deletions relative to centromeres (green), scale bar is 2 μm. (c) Rapid disease progression of AA patients harboring LSAMP deletion shown by the Kaplan–Meier biochemical recurrence free survival curves. Number of AA patients in BCR curves with deletion (red) or without deletion (blue) is marked above the X-axis.

3.4. The mutation landscape of prostate cancers of African American and Caucasian American men

We detected 261 somatically acquired SNVs in the coding sequence of 247 genes from 7 CA and 7 AA patients (Supplementary Table 5). A comparison of these SNVs against COSMIC and TCGA databases as shown in Fig. 1a, identified 43 SNVs that were previously described in prostate and/or other cancers (Baca et al., 2013, Barbieri et al., 2012, Forbes et al., 2015, Kandoth et al., 2013) (Supplementary Table 11). SNVs belonging to reported recurrently mutated CaP genes included SPOP, MED12, TP53, MLL3, ATM, CTNNB1 and PIK3CB. Additionally we identified SNVs in genes that were not previously linked to prostate cancer (DCAF4L2, RYR3, FAT4, CNTN5 and CDH19). While the majority of SNVs were detected in only one of 14 patients, several were detected in more than one patient: a distinct SNV of CEL1 was detected in two patients; two separate SNVs of SPOP, MLL3, FOXN2, EYS and NOX3 were detected in two different patients. Interestingly, four different SNVs of RBM26 were detected in one patient (Supplementary Table 5). Recurrent CaP genomic alterations such as TMPRSS2-ERG fusion, PTEN and CHD1 deletions and SPOP mutation were confirmed (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 5). ERG oncoprotein expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry showing anticipated lower frequencies in AA (29%) in comparison to CA (56%) cases (Farrell et al., 2013, Rosen et al., 2012).

3.5. Virtual absence of PTEN deletions in early stage prostate cancers of African American men

Recent studies noted frequency differences in PTEN deletion between AA and CA CaP (Blattner et al., 2014, Khani et al., 2014). The virtual absence of PTEN deletion observed in AA CaP whole genome sequence data shown here was striking (Fig. 1b). To validate these observations in an independent set of samples, we probed the PTEN locus by FISH in a tissue microarray, as described above. PTEN deletions were notably less frequent in AA (15%) compared to CA cases (63%) (p = 1E-06), with even larger difference seen between Gleason 6 AA (7%) and CA (53%) tumors (p = 0.004) (Table 2a, Table 2b).

Table 2a.

PTEN deletion status evaluated by FISH assay.

| Race |

PTEN status |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No deletion | Deletion | ||

| AA, N = 40 | 35 (88%) | 6 (15%) | 1E-06 |

| CA, N = 59 | 22 (37%) | 37 (63%) | |

Table 2b.

PTEN deletion frequencies by worst Gleason sum.

| Gleason Sum | AA (N = 40) |

CA (N = 52) |

p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTEN No Deletion | PTEN Deletion | PTEN No Deletion | PTEN Deletion | ||

| 6 or less | 14 (93%) | 1 (7%) | 9 (47%) | 10 (53%) | 0.004 |

| 7 | 11 (73%) | 4 (27%) | 7 (33%) | 14 (67%) | 0.02 |

| 8 to 10 | 7 (70%) | 3 (30%) | 4 (33%) | 8 (67%) | 0.09 |

4. Discussion

Emerging data from our and other groups support biological and genetic differences between African American (AA) and Caucasian American (CA) CaP. While reports on comprehensive evaluations of primary CaP genomes or exomes have highlighted recurrent alterations (TMPRSS2-ERG, PTEN, SPOP and CHD1), these studies were focused on patients with Caucasian ancestry. ERG oncogenic activation via gene fusions and deletion of the PTEN tumor suppressor are major early tumorigenic driver alterations in CaP genomes (Bigner et al., 1984, Li et al., 1997, Tomlins et al., 2005). Within the continuum of assessments of these alterations high frequencies in CA patients and lower frequencies in AA men were noted (Blattner et al., 2014, Farrell et al., 2014, Hu et al., 2008, Khani et al., 2014, Magi-Galluzzi et al., 2011, Petrovics et al., 2005, Rosen et al., 2012). In Asian subjects, CaP frequencies of ERG and PTEN alterations are the lowest (Blattner et al., 2014, Mao et al., 2010, Qi et al., 2014). The goal of this study was to delineate genomic features of AA and CA CaP focusing on early stages of the disease representing majority of cases at initial presentation in Western countries.

In summary, three recurrent genomic alterations (PTEN, LSAMP region and ERG) showed distinct prevalence between AA and CA CaP. This study discovered a novel deletion of LSAMP locus as a prevalent genomic alteration in AA CaP. Notably, this alteration is associated with rapid disease progression. Evaluation of the minimum site of deletion in SNP datasets of AA tumors suggests that the primary target of deletion is the LSAMP gene. LSAMP locus inactivation by recurrent deletions has been reported in osteosarcoma (Barøy et al., 2014, Kresse et al., 2009) and acute myeloid leukemia (Kühn et al., 2012) and by translocation in clear cell renal carcinoma (Chen et al., 2003) and ovarian carcinoma (Ntougkos et al., 2005). Single nucleotide polymorphism within the first intron of LSAMP has recently been shown to be a predictor of prostate cancer-specific mortality (Huang et al., 2013). Further, alterations of ZBTB20, GAP43 and GSK3B adjacent to LSAMP are less well understood but are suspected to have pro-tumorigenic functions in cancer (Chen et al., 2014, Kroon et al., 2014, Shi et al., 2011). Thus, the observed allelic loss of LSAMP in CaP is consistent with its tumor suppressor function reported in cancer.

Currently, chromoplexy through AR-mediated DNA breaks and faulty repair is a proposed mechanism of prostate cancer genomic rearrangements (Baca et al., 2013, Taylor et al., 2010). In our study we found significantly higher frequency of inter-chromosomal rearrangements in AA than in CA CaPs. Whether the chromoplexy initiating mechanism or the subsequent selection of tumor cells is different between AA and CA men needs to be further elucidated.

Taken together, this report highlights distinct features of AA CaP genome with emphasis on new findings on recurrent deletions of the LSAMP locus in AA CaP which associates with disease recurrence and identifies an aggressive subset of prostate cancers. These findings have broader implication towards the understanding of cancer genomes of currently underrepresented populations towards the development of ethnically informed diagnostic, prognostic marker and tailored therapeutic approaches.

Authorship contributions

Majority of experiments were performed by GP, HL, TS and S-H T. Bioinformatics analyses were performed by TS, SK, QL, KY, BK, DR, KG, CLD, IC, MSc, MSe, SzZ and TW. DY performed immunohistochemistry and FISH assays. LR prepared and QC-ed bio-specimens, IK performed 5′ RACE. DT performed supporting cell culture experiments. TMAs were prepared by IAS and ML. FISH probes were designed and prepared by RE, JC and HZ. TMA FISH readings were performed by HL, TG, SZ and IAS. Statistical analyses were performed by YC. TW, MF, AD and SS conceived and directed the study. TW, MF, RE, DGM, SS, JK, AD and SS wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by funds from the Center for Prostate Disease Research, Uniformed Services University Program, HU0001-10-2-0002 to DGM, the NCI/EDRN ACN12011-001-0 to SS, the NCI RO1 CA162383-05 grant to SS, the H.L. Snyder Medical Foundation to MLF, the KMR-12-1-2012-0216 and OTKA-114560 grants to DR and IC, the Otto Mønsteds Foundation to IC and ZS, and the Mazzone Foundation, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, grants by MTA-TKI643/2012, KTIA_NAP_13-2014-0021 to ZS. The funders did not have any role in the in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation or writing of the report. The authors thank Dr. Madhvi Upender, Dr. Ahmed A. Mohamed, Dr. Allissa Dillman, Dr. Nicholas Griner, Dr. Shashwat Sharad, Dr. Zhaozhang Li, and Ms. London Toney for the experimental support and Mr. Stephen Doyle for his assistance with the art and graphics. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense or the US Government.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.10.028.

Contributor Information

Matthew Freedman, Email: freedman@broadinstitute.org.

Albert Dobi, Email: adobi@cpdr.org.

Shiv Srivastava, Email: ssrivastava@cpdr.org.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Supplementary tables

References

- Baca S.C., Prandi D., Lawrence M.S., Mosquera J.M., Romanel A., Drier Y., Park K., Kitabayashi N., MacDonald T.Y. Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell. 2013;153:666–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri C.E., Baca S.C., Lawrence M.S., Demichelis F., Blattner M., Theurillat J.P., White T.A., Stojanov P., Van Allen E. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent SPOP, FOXA1 and MED12 mutations in prostate cancer. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:685–689. doi: 10.1038/ng.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barøy T., Kresse S.H., Skarn M., Stabell M., Castro R., Lauvrak S., Llombart-Bosch A., Myklebost O., Meza-Zepeda L.A. Reexpression of LSAMP inhibits tumor growth in a preclinical osteosarcoma model. Mol. Cancer. 2014;13:93. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson H., Wirapati P., Speed T.P. A single-array preprocessing method for estimating full-resolution raw copy numbers from all Affymetrix genotyping arrays including GenomeWideSNP 5 & 6. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2149–2156. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M.F., Lawrence M.S., Demichelis F., Drier Y., Cibulskis K., Sivachenko A.Y., Sboner A., Esgueva R., Pflueger D. The genomic complexity of primary human prostate cancer. Nature. 2011;470:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature09744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigner S.H., Mark J., Mahaley M.S., Bigner D.D. Patterns of the early, gross chromosomal changes in malignant human gliomas. Hereditas. 1984;101:103–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1984.tb00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner M., Lee D.J., O'Reilly C., Park K., MacDonald T.Y., Khani F., Turner K.R., Chiu Y.L., Wild P.J. SPOP mutations in prostate cancer across demographically diverse patient cohorts. Neoplasia. 2014;16:14–20. doi: 10.1593/neo.131704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeva V., Popova T., Bleakley K., Chiche P., Cappo J., Schleiermacher G., Janoueix-Lerosey I., Delattre O., Barillot E. Control-FREEC: a tool for assessing copy number and allelic content using next-generation rsequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:423–425. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutros P.C., Fraser M., Harding N.J., de Borja R., Trudel D., Lalonde E., Meng A., Hennings-Yeomans P.H., McPherson A. Spatial genomic heterogeneity within localized, multifocal prostate cancer. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:736–745. doi: 10.1038/ng.3315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Lui W.O., Vos M.D., Clark G.J., Takahashi M., Schoumans J., Khoo S.K., Petillo D., Lavery T. The t(1;3) breakpoint-spanning genes LSAMP and NORE1 are involved in clear cell renal cell carcinomas. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:405–413. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Wallis J.W., McLellan M.D., Larson D.E., Kalicki J.M., Pohl C.S., McGrath S.D., Wendl M.C., Zhang Q. BreakDancer: an algorithm for high-resolution mapping of genomic structural variation. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Liu C., Patel A.J., Liao C.P., Wang Y., Le L.Q. Cells of origin in the embryonic nerve roots for NF1-associated plexiform neurofibroma. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chornokur G., Dalton K., Borysova M.E., Kumar N.B. Disparities at presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and survival in African American men, affected by prostate cancer. Prostate. 2011;71:985–997. doi: 10.1002/pros.21314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibulskis K., Lawrence M.S., Carter S.L., Sivachenko A., Jaffe D., Sougnez C., Gabriel S., Meyerson M., Lander E.S. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell J., Petrovics G., McLeod D.G., Srivastava S. Genetic and molecular differences in prostate carcinogenesis between African American and Caucasian American men. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:15510–15531. doi: 10.3390/ijms140815510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell J., Young D., Chen Y., Cullen J., Rosner I.L., Kagan J., Srivastava S., Mc L.D., Sesterhenn I.A. Predominance of ERG-negative high-grade prostate cancers in African American men. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2014;2:982–986. doi: 10.3892/mco.2014.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes S.A., Beare D., Gunasekaran P., Leung K., Bindal N., Boutselakis H., Ding M., Bamford S., Cole C. COSMIC: exploring the world's knowledge of somatic mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D805–D811. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furusato B., Tan S.H., Young D., Dobi A., Sun C., Mohamed A.A., Thangapazham R., Chen Y., McMaster G. ERG oncoprotein expression in prostate cancer: clonal progression of ERG-positive tumor cells and potential for ERG-based stratification. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2010;13:228–237. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2010.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso C.S., Wu Y.M., Robinson D.R., Cao X., Dhanasekaran S.M., Khan A.P., Quist M.J., Jing X., Lonigro R.J. The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2012;487:239–243. doi: 10.1038/nature11125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey R.J., Darlison M.G. Random-primed cDNA synthesis fracilitates the isolation of multiple 5′-cDNA ends by RACE. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4002. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopman A.H., van Hooren E., van de Kaa C.A., Vooijs P.G., Ramaekers F.C. Detection of numerical chromosome aberrations using in situ hybridization in paraffin sections of routinely processed bladder cancers. Mod. Pathol. 1991;4:503–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Dobi A., Sreenath T., Cook C., Tadase A.Y., Ravindranath L., Cullen J., Furusato B., Chen Y. Delineation of TMPRSS2-ERG splice variants in prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:4719–4725. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S.P., Lin V.C., Lee Y.C., Yu C.C., Huang C.Y., Chang T.Y., Lee H.Z., Juang S.H., Lu T.L. Genetic variants in nuclear factor-kappa B binding sites are associated with clinical outcomes in prostate cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer. 2013;49:3729–3737. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandoth C., McLellan M.D., Vandin F., Ye K., Niu B., Lu C., Xie M., Zhang Q., McMichael J.F. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khani F., Mosquera J.M., Park K., Blattner M., O'Reilly C., MacDonald T.Y., Chen Z., Srivastava A., Tewari A.K. Evidence for molecular differences in prostate cancer between African American and Caucasian men. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20:4925–4934. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klambauer G., Schwarzbauer K., Mayr A., Clevert D.A., Mitterecker A., Bodenhofer U., Hochreiter S. cn.MOPS: mixture of poisons for discovering copy number variations in next-generation sequencing data with a low false discovery rate. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40 doi: 10.1093/nar/gks003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koboldt D.C., Zhang Q., Larson D.E., Shen D., McLellan M.D., Lin L., Miller C.A., Mardis E.R., Ding L. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22:568–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse S.H., Ohnstad H.O., Paulsen E.B., Bjerkehagen B., Szuhai K., Serra M., Schaefer K.L., Myklebost O., Meza-Zepeda L.A. LSAMP, a novel candidate tumor suppressor gene in human osteosarcomas, identified by array comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosom. Cancer. 2009;48:679–693. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon J., in ‘t Veld L.S., Buijs J.T., Cheung H., van der Horst G., van der Pluijm G. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta inhibition depletes the population of prostate cancer stem/progenitor-like cells and attenuates metastatic growth. Oncotarget. 2014;5:8986–8994. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn M.W., Radtke I., Bullinger L., Goorha S., Cheng J., Edelmann J., Gohlke J., Su X., Paschka P. High-resolution genomic profiling of adult and pediatric core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia reveals new recurrent genomic alterations. Blood. 2012;119:e67–e75. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-380444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., White T.A., MacKenzie A.P., Clegg N., Lee C., Dumpit R.F., Coleman I., Ng S.B., Salipante S.J. Exome sequencing identifies a spectrum of mutation frequencies in advanced and lrethal prostate cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:17087–17092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108745108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson D.E., Harris C.C., Chen K., Koboldt D.C., Abbott T.E., Dooling D.J., Ley T.J., Mardis E.R., Wilson R.K. SomaticSniper: identification of somatic point mutations in whole genome sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:311–317. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Yen C., Liaw D., Podsypanina K., Bose S., Wang S.I., Puc J., Miliaresis C., Rodgers L. PTEN, a putative prrotein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magi-Galluzzi C., Tsusuki T., Elson P., Simmerman K., LaFargue C., Esgueva R., Klein E., Rubin M.A., Zhou M. TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion prevalence and class are significantly different in prostate cancer of Caucasian, African-American and Japanese patients. Prostate. 2011;71:489–497. doi: 10.1002/pros.21265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X., Yu Y., Boyd L.K., Ren G., Lin D., Chaplin T., Kudahetti S.C., Stankiewicz E., Xue L. Distinct genomic alterations in prostate cancers in Chinese and Western populations suggest alternative pathways of prostate carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5207–5212. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D.N., Starks A.M., Ambs S. Biological determinants of health disparities in prostate cancer. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2013;25:235–241. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835eb5d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merseburger A.S., Kuczyk M.A., Serth J., Bokemeyer C., Young D.Y., Sun L., Connelly R.R., McLeod D.G., Mostofi F.K. Limitations of tissue microarrays in the evaluation of focal alterations of bcl-2 and p53 in whole mount derived prostate tissues. Oncol. Rep. 2003;10:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntougkos E., Rush R., Scott D., Frankenberg T., Gabra H., Smyth J.F., Sellar G.C. The IgLON family in epithelial ovarian cancer: expression profiles and clinicopathologic correlates. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:5764–5768. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovics G., Liu A., Shaheduzzaman S., Furusato B., Sun C., Chen Y., Nau M., Ravindranath L., Chen Y. Frequent overexpression of ETS-related gene-1 (ERG1) in prostate cancer transcriptome. Oncogene. 2005;24:3847–3852. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz M.M., Freedman M.L. The genetics of cancer risk. Cancer J. 2011;17:416–422. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31823e5387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell I.J., Bock C.H., Ruterbusch J.J., Sakr W. Evidence supports a faster growth rate and/or earlier transformation to clinically significant prostate cancer in black than in white American men, and influences racial progression and mortality disparity. J. Urol. 2010;183:1792–1796. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A.L., Patterson N.J., Plenge R.M., Weinblatt M.E., Shadick N.A., Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M., Yang X., Zhang F., Lin T., Sun X., Li Y., Yuan H., Ren Y., Zhang J. ERG rearrangement is associated with prostate cancer-related death in Chinese prostate cancer patients. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D., Van Allen E.M., Wu Y.M., Schultz N., Lonigro R.J., Mosquera J.M., Montgomery B., Taplin M.E., Pritchard C.C. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prrostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161:1215–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen P., Pfister D., Young D., Petrovics G., Chen Y., Cullen J., Bohm D., Perner S., Dobi A. Differences in frequency of ERG oncoprotein expression between index tumors of Caucasian and African American patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 2012;80:749–753. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A., Ding J., Morin R., Crisan A., Ha G., Giuliany R., Bashashati A., Hirst M., Turashvili G. JointSNVMix: a probabilistic model for accurate detection of somatic mutations in normal/tumour paired next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:907–913. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders C.T., Wong W.S., Swamy S., Becq J., Murray L.J., Cheetham R.K. Strelka: accurate somatic small-variant calling from sequenced tumor-normal sample pairs. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1811–1817. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X., Kaminskyj S.G. 5′ RACE by tailing a general template-switching oligonucleotide. Biotechniques. 2000;29:1192–1195. doi: 10.2144/00296bm07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Hu Z., Wu C., Dai J., Li H., Dong J., Wang M., Miao X., Zhou Y. A genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for non-cardia gastric cancer at 3q13.31 and 5p13.1. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:1215–1218. doi: 10.1038/ng.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B.S., Schultz N., Hieronymus H., Gopalan A., Xiao Y., Carver B.S., Arora V.K., Kaushik P., Cerami E. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Weinstein J.N., Collisson E.A., Mills G.B., Shaw K.R., Ozenberger B.A., Ellrott K., Shmulevich I., Sander C. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1113–1120. doi: 10.1038/ng.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlins S.A., Rhodes D.R., Perner S., Dhanasekaran S.M., Mehra R., Sun X.W., Varambally S., Cao X., Tchinda J. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loo P., Nilsen G., Nordgard S.H., Vollan H.K., Børresen-Dale A.L., Kristensen V.N., Lingjærde O.C. Analyzing cancer samples with SNP arrays. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;802:57–72. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-400-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Jia P., Li F., Chen H., Ji H., Hucks D., Dahlman K.B., Pao W., Zhao Z. Detecting somatic point mutations in cancer genome sequencing data: a comparison of mutation callers. Genome Med. 2013;5:91. doi: 10.1186/gm495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weischenfeldt J., Simon R., Feuerbach L., Schlangen K., Weichenhan D., Minner S., Wuttig D., Warnatz H.J., Stehr H. Integrative genomic analyses reveal an androgen-driven somatic alteration landscape in early-onset prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto M., Cutz J.C., Nuin P.A., Joshua A.M., Bayani J., Evans A.J., Zielenska M., Squire J.A. Interphase FISH analysis of PTEN in histologic sections shows genomic deletions in 68% of primary prostate cancer and 23% of high-grade prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasias. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2006;169:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary tables