Abstract

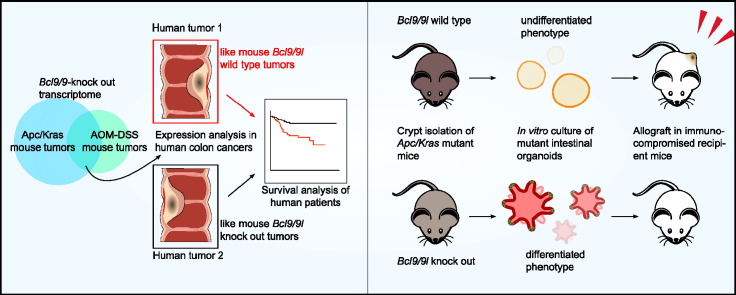

BCL9/9L proteins enhance the transcriptional output of the β-catenin/TCF transcriptional complex and contribute critically to upholding the high WNT signaling level required for stemness maintenance in the intestinal epithelium. Here we show that a BCL9/9L-dependent gene signature derived from independent mouse colorectal cancer (CRC) models unprecedentedly separates patient subgroups with regard to progression free and overall survival. We found that this effect was by and large attributable to stemness related gene sets. Remarkably, this signature proved associated with recently described poor prognosis CRC subtypes exhibiting high stemness and/or epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) traits. Consistent with the notion that high WNT signaling is required for stemness maintenance, ablating Bcl9/9l-β-catenin in murine oncogenic intestinal organoids provoked their differentiation and completely abrogated their tumorigenicity, while not affecting their proliferation. Therapeutic strategies aimed at targeting WNT responses may be limited by intestinal toxicity. Our findings suggest that attenuating WNT signaling to an extent that affects stemness maintenance without disturbing intestinal renewal might be well tolerated and prove sufficient to reduce CRC recurrence and dramatically improve disease outcome.

Keywords: WNT signaling, BCL9/9L-β-catenin, Cancer stem cells, Colorectal cancer subtypes, Patient outcome

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Inhibiting BCL9/9L-β-catenin in CRC models reduces stemness and boosts differentiation traits

-

•

CRC patients with low expression of BCL9/9L-β-catenin regulated genes have a better prognosis

-

•

Tempering WNT signaling without affecting intestinal self renewal might be an attractive therapeutic strategy in CRC

Mutational activation of the WNT pathway is a key oncogenic event in colorectal cancer (CRC). Targeting the WNT pathway therefore appears as an attractive strategy, but the therapeutic window might be limited due to intestinal toxicity. Maximum WNT signaling strength is required for upholding stemness traits, which are linked to poor prognosis in CRC. Our data suggest that tempering WNT signaling through abrogating BCL9/9L-β-catenin signaling in CRC models is tolerable for intestinal homeostasis yet strongly diminishes stemness traits and may have a vast impact on CRC patient outcome.

1. Introduction

The majority of colorectal cancers (CRC) are caused by a common set of genetic alterations, whereby mutational activation of the WNT pathway represents a key oncogenic initiation event (Cancer Genome Atlas, 2012, Fearon and Vogelstein, 1990) that remains critical for tumor maintenance and progression (Dow et al., 2015). Molecular CRC subtypes based upon gene expression patterns have recently been described that likely reflect further genetic and functional heterogeneity and are associated with patient outcome (Budinska et al., 2013, Marisa et al., 2013, Sadanandam et al., 2013). Across these data sets, subtypes enriched for mesenchymal and/or stem-cell-like features were associated with poorest outcome (Budinska et al., 2013, Guinney et al., 2015, Marisa et al., 2013, Sadanandam et al., 2013).

In the intestinal epithelium a gradient of WNT-β-catenin signaling along the crypt-villus axis regulates cellular hierarchy and continuous renewal. High WNT signaling is required for the establishment of intestinal stem cells (ISC) at the crypt bottom, where neighboring Paneth cells constitute the major source of WNT ligands (Clevers, 2013, Sato et al., 2011b). Numerous observations indicate that analogously, WNT-β-catenin signaling contributes to CRC progression through the maintenance of a stem-cell-like state in a subset of cancer cells (Anastas and Moon, 2013, Nguyen et al., 2012).

Canonical WNT signaling output is mediated through a core complex of β-catenin and TCF/LEF transcription factors, which in the intestine is critical for the establishment and proliferation of the normal crypt epithelium, as ablation of either TCF or β-catenin results in prompt crypt loss (Fevr et al., 2007, Ireland et al., 2004, Korinek et al., 1998, van Es et al., 2012). Whereas the C-terminal domain of β-catenin recruits proteins involved in chromatin remodeling and transcriptional activation that are not β-catenin specific (Mosimann et al., 2009, Valenta et al., 2012), its N-terminal domain selectively binds Bcl9 or Bcl9l, two likely redundant paralogs which serve as adaptors for additional partner proteins and thereby contribute to further enhancing WNT-β-catenin transcription (Valenta et al., 2012). Despite this apparent auxiliary role, Bcl9 proteins are essential for mouse development, as their ablation is lethal at E10 (Cantù et al., 2014). Yet full blockade of WNT signaling through ablating WNTless (Wls) or Porcupine, which are critical for the secretion of WNT ligands, results in a stronger phenotype with pre-gastrulation lethality at E7 (Biechele et al., 2011, Fu et al., 2009). In mammalian cells overexpression and RNAi gene knock-down experiments confirmed that Bcl9 proteins contribute to, but are not essential for WNT-β-catenin transcription (Brack et al., 2009, Brembeck et al., 2004, Hoffmans et al., 2005, Mani et al., 2009, Valenta et al., 2012).

Our previous work revealed that ablation of Bcl9/9l in the adult mouse is dispensable for normal homeostasis of the gastrointestinal epithelium. Though there were no overt anomalies in intestinal homeostasis, mice lacking Bcl9/9l proteins were deficient in epithelial regeneration, as shown in an ulcerative colitis model, pointing to a possible deficiency in ISC expansion and/or maintenance (Deka et al., 2010). The role of Bcl9/9l in the regulation of stemness properties became overtly apparent in a mouse chemical carcinogenesis model of CRC, which combines exposure to the mutagen azoxymethane (AOM) and the inflammatory agent dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) and serves as a model for constitutively WNT driven human CRC (Greten et al., 2004, Taketo and Edelmann, 2009). Ablation of Bcl9/9l proteins resulted in virtual loss of ISC markers, concurrently with marked down-regulation of genes related to EMT and a group of selected WNT targets (Deka et al., 2010). The control of ISC identity appears to depend upon WNT signaling strength (Schuijers et al., 2015). Here we show that the apparently rather subtle tuning role of Bcl9 proteins in WNT β-catenin signaling may by critical for upholding stemness traits in CRC, contributing to the functional heterogeneity among molecular subtypes and determining patient outcome.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. APC/Kras-mutant Organoids

The culture of small intestinal crypts from Apc/Kras animals has been previously described (Sato et al., 2011a, van Es and Clevers, 2015). Briefly, crypts were isolated and purified, embedded in 50 μl matrigel drops (Corning, 356231) and overlaid with 500 μl organoid medium (Advanced DMEM/F12 (Life Technologies, 11320-082), 2 mM GlutaMAX (Life Technologies, 35050-061), 10 mM HEPES buffer (Sigma, 83264-100ML-F), 0.5 U/ml Penicillin/Streptomycin (Life Technologies, 15070-063), N2 (Life Technologies, 17502-048), B27 (Life Technologies, 12587-010). Organoids were expanded in growth factor supplemented medium for 5 days: 50 ng/ml mEGF (Life Technologies, PMG8041), 100 ng/ml mNoggin (Peprotech, 250–38), 500 ng/ml hRSPO1 (R&D, 4645-RS-025) according to Fig. 4A. EGF and R-spondin were subsequently removed to select for organoids that had lost the wild-type Apc copy. The medium was changed every 2 days. Established mutant lines were passaged every four days by mechanical disruption with a bent P1000 pipette tip. Allograft assays were performed by subcutaneously injecting 50′000 organoid cells mixed 1:1 with 100 μl matrigel. Receiver NOD scid gamma mice (Jackson laboratory, 005557) were bred by the Animal Facility of Epalinges, University of Lausanne, Switzerland. Allograft length and width was determined by caliper measurement, volume was calculated by use of the modified ellipsoid formula: 1 / 2(Length × Width^2). In vitro recombination by R26-CreERT2 was induced by applying 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Sigma, H7904) to the culture medium.

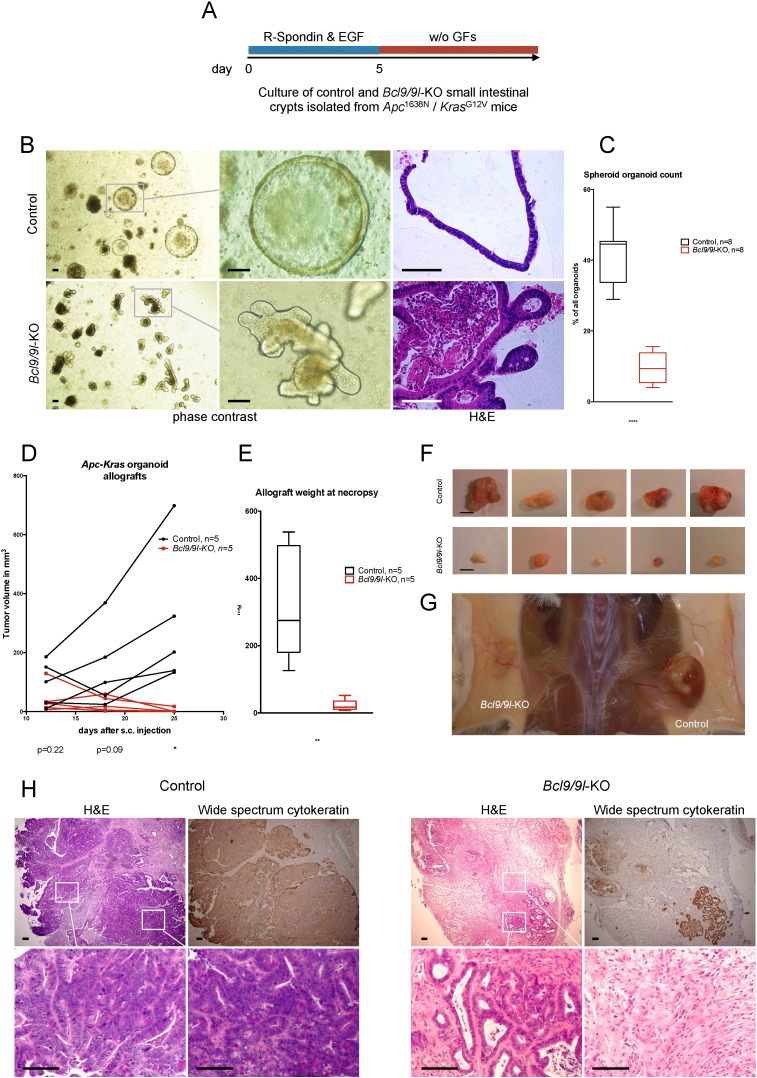

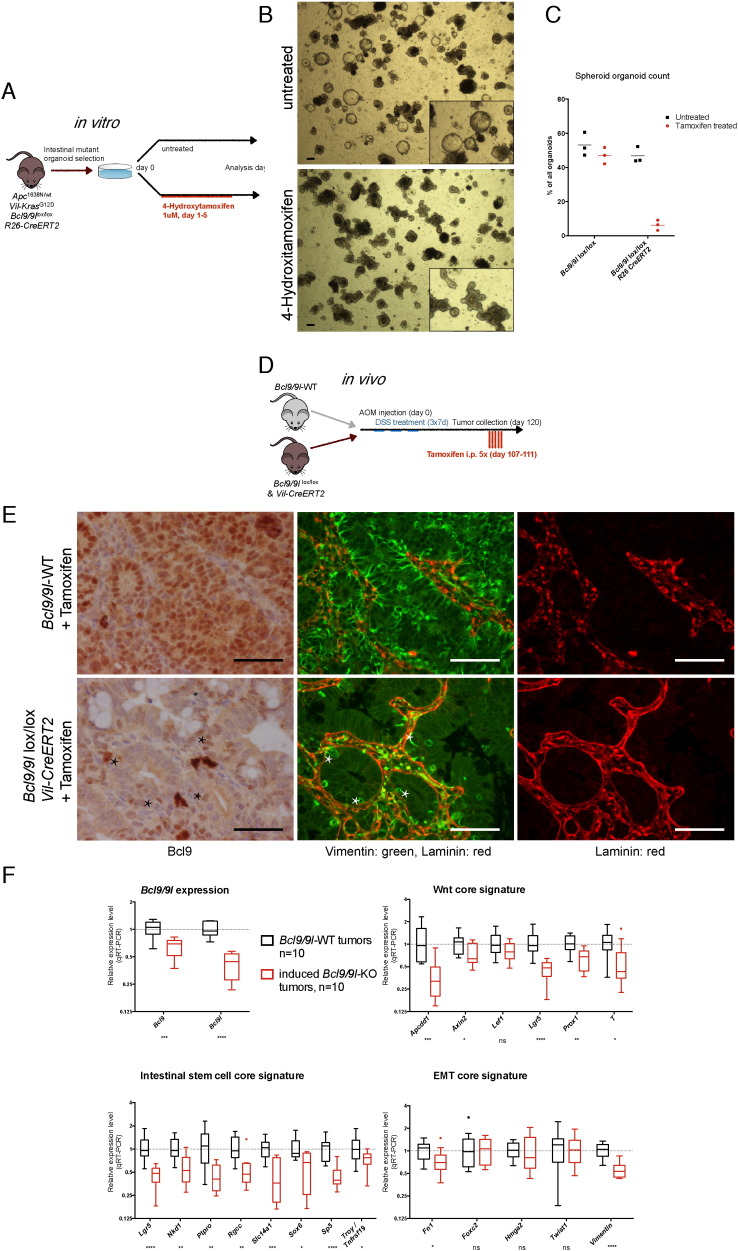

Fig. 4.

Loss of Bcl9/9l accelerates differentiation of intestinal organoids and abrogates their tumorigenicity. (A) Small intestinal crypts derived from Bcl9/9l-wild-type or -KO Apc/Kras mutant mice were cultivated for 5 days as described (see Materials and Methods and ref. Sato et al. (2011a)). Subsequent removal of EGF and R-spondin resulted in selection of organoids with Apc loss-of-heterozygosity that grew independently of those growth factors. (B) Morphology of organoids one week after growth factor removal. Bcl9/9l-wild-type cultures contained a large proportion of spheroids, Bcl9/9l-KO cultures were virtually devoid of spheroids and contained mostly budding organoids. Scale bars: 100 μm. (C) Quantification of undifferentiated spheroids. (D) Organoid-derived allografts of 50,000 cells injected subcutaneously in NOD scid gamma mice. (E) Weight of allografts collected after 26 days upon reaching the legally admitted tumor size. (F) Resected allografts. Scale bar: 500 μm. (G) Representative picture of a NOD scid gamma mouse exhibiting a large wild-type allograft (right flank) and a small mutant allograft (left flank), consisting mostly of scar tissue. (H) Left panel: Representative images of consecutive sections of a Bcl9/9l-wild-type allograft. Histopathological analysis revealed a large, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of intestinal origin. Broad spectrum cytokeratin staining confirms the large content of viable epithelial cells. Scale bars: 50 μm. Right panel: Representative images of consecutive sections of a Bcl9/9l-KO allograft. Histopathological analysis revealed small residual and well differentiated islets of epithelial cells of intestinal origin (bottom left). Large parts of the allograft consist of fibroblastic, presumably scar tissue (bottom right) with residual inflammation. Scale bars: 50 μm.

2.2. Human CRC Datasets

We made use of the following CRC Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) databases: GSE12945, GSE14333, GSE17538, GSE33113, GSE37892, GSE39582 and GSE41258, all generated using the Affymetrix HG U133 Plus 2.0 platform. Gene expression data from the PETACC-3 (Pan-European Trials in Alimentary Tract Cancers) trial patients were generated as previously described (Popovici et al., 2012) using the ALMAC Colorectal Cancer DSA platform (Craigavon, Northern Ireland), which is a customized Affymetrix chip that includes 61′528 probe sets mapping to 15′920 unique Entrez Gene IDs. A set of 752 colorectal cancer patients of stage II (108/752) and stage III (644/752) was used here.

2.3. Signature Scores and Survival Analysis

Bcl9/9l-dependent genes with coinciding significant differential expression (log2 fold change of > 1 and an adjusted p value of < 0.001) in both the AOM/DSS and Apc/Kras model were used to identify human homologs (NCBI) and constitute the BCL9/9L-KO signature. Optimal microarray probe sets were selected according to Li et al. (2011). The BCL9/9L-KO signature is composed of 300 down-regulated and 78 up-regulated human genes. Of these, 215 (71%) down-regulated and 66 (84%) up-regulated genes were contained in the PETACC-3 dataset (Table S1). The BCL9/9L-KO signature score was defined by subtracting the average of the 300 human homologs down-regulated upon ablation of Bcl9/9l from the average of the 78 human homologs up-regulated (or 215 down-regulated and 66 up-regulated genes in the PETACC-3 dataset, respectively). Effects of the BCL9/9L-KO signature on DFS and OS were investigated using Kaplan–Meier estimates with patients categorized into two groups by median split and logrank tests for assessing significance. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess the prognostic value of interquartile range (IQR)-standardized values in each patient cohort separately. These survival analyses were performed with the R package survival. Meta-analysis and forest plots were done using the Meta package in R.

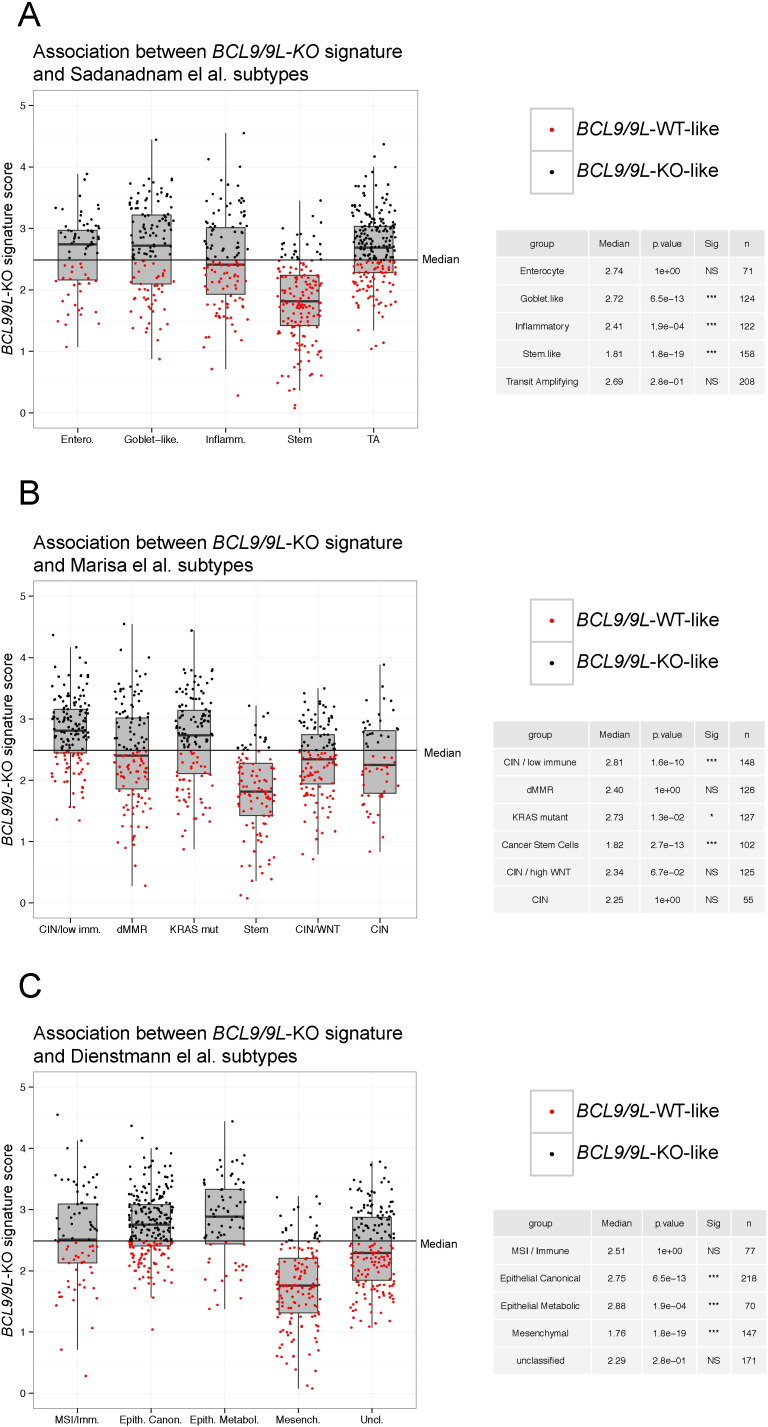

2.4. Association Between Known CRC Subtypes and BCL9/9L-KO Signature

The association between the BCL9/9L-KO signature score standardized by IQR division and subtypes from three studies (Guinney et al., 2015, Marisa et al., 2013, Sadanandam et al., 2013) was determined by performing a non-parametric Wilcoxon test to evaluate whether the median of BCL9/9L-KO signature score for each subtype was different from the median of all patients (2.455313).

3. Results

3.1. RNA Sequencing Reveals a Robust Bcl9/9l-dependent Gene Expression Signature Across Independent Mouse CRC Models

We previously made use of a chemically induced mouse CRC model, which combines exposure to the mutagen azoxymethane (AOM) and the inflammatory agent DSS and serves as a model for constitutively WNT driven human CRC (Greten et al., 2004, Taketo and Edelmann, 2009), to investigate the genome-wide impact of Bcl9/9l ablation on gene expression. Among the striking changes, down-regulation of selected WNT targets, ISC markers and EMT-related genes was particularly noticeable (Deka et al., 2010). AOM/DSS tumors are typically initiated by β-catenin stabilizing mutations (Greten et al., 2004). We therefore sought to validate our observations in an independent mouse CRC model driven by loss of Apc and oncogenic Kras, which are common oncogenic events in human CRC (Janssen et al., 2006). Apc1638N and villin-driven KrasG12V alleles (hereafter Apc/Kras) were crossed into a homozygous Bcl/9lloxP/loxP background (Deka et al., 2010). Bcl9/9l deletion in the intestinal epithelium was driven by villin-Cre; mice lacking the villin-Cre transgene served as controls (Fig. 1A).

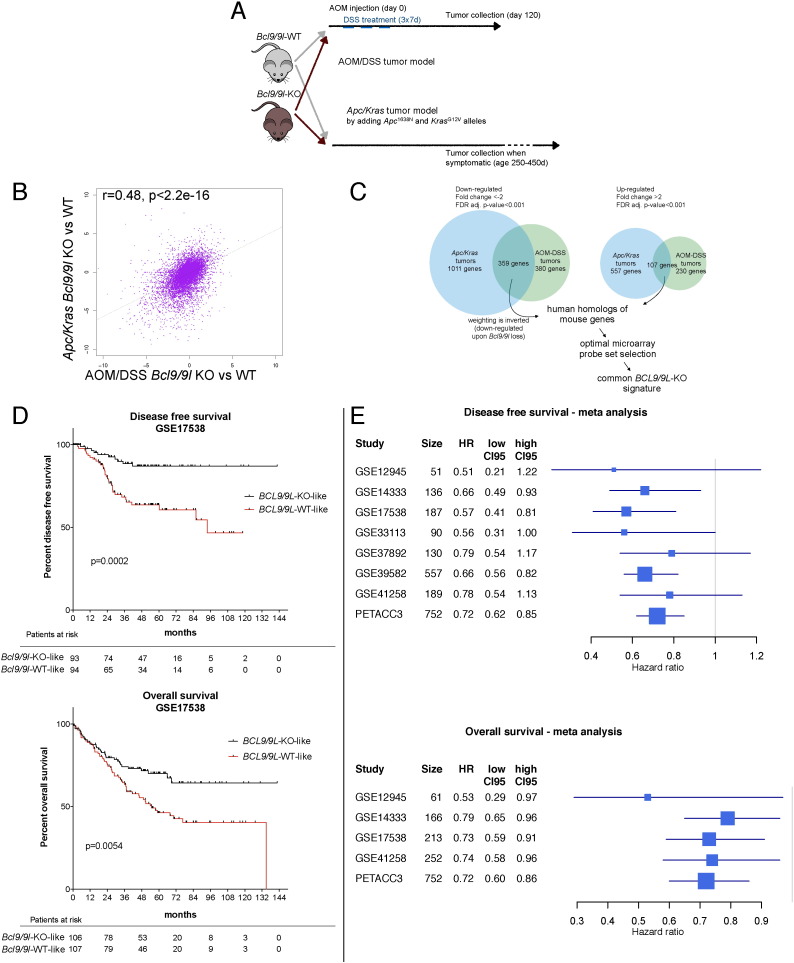

Fig. 1.

A murine CRC derived BCL9/9L-KO signature is associated with vastly improved survival in human CRC. (A) Bcl9/9l-KO and control littermates were subjected to a chemical tumorigenesis protocol as described (see Materials and Methods and ref. Neufert et al. (2007)). Independently, Apc/Kras alleles were crossed into Bcl9/9l-KO and wild-type background for inducing WNT-activated CRC (Janssen et al., 2006). (B) RNAseq: Correlation of log2 fold changes between wild-type and Bcl9/9l-KO AOM/DSS and Apc/Kras tumors. Pearson's r were determined and tested for the hypothesis r = 0. (C) Venn diagram (approximated proportions). Left: genes down-regulated in Bcl9/9l-KO samples of both Apc/Kras and AOM/DSS tumors; right: respective up-regulated genes. Human homologs of common mouse genes were selected according to NCBI and corresponding optimal microarray probe sets chosen as described (Li et al., 2011), resulting in 300 down-regulated (negatively weighted) and 78 up-regulated (positively weighted) human probe sets. This gene list, hereafter referred to as “BCL9/9L-KO signature”, is shown in Table S1 and was used for probing human CRC patient databases. (D) Kaplan–Meier estimates for DFS and OS of CRC patients from one of the largest public human CRC microarray databases (Affymetrix HG U133 Plus 2.0; GSE17538). DFS and OS of patients with higher (black) or lower (red) expression of the BCL9/9L-KO signature after subdividing patients according to a median split. (E) Meta-analysis of all CRC patient microarray databases. The relative strength of association of the BCL9/9L-KO signature with DFS and OS is presented as forest plots of HRs for one inter-quartile unit of the signature score. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

A murine CRC derived BCL9/9L-KO signature is associated with vastly improved survival in human CRC. (A) Bcl9/9l-KO and control littermates were subjected to a chemical tumorigenesis protocol as described (see Materials and Methods and ref. Neufert et al. (2007)). Independently, Apc/Kras alleles were crossed into Bcl9/9l-KO and wild-type background for inducing WNT-activated CRC (Janssen et al., 2006). (B) RNAseq: Correlation of log2 fold changes between wild-type and Bcl9/9l-KO AOM/DSS and Apc/Kras tumors. Pearson's r were determined and tested for the hypothesis r = 0. (C) Venn diagram (approximated proportions). Left: genes down-regulated in Bcl9/9l-KO samples of both Apc/Kras and AOM/DSS tumors; right: respective up-regulated genes. Human homologs of common mouse genes were selected according to NCBI and corresponding optimal microarray probe sets chosen as described (Li et al., 2011), resulting in 300 down-regulated (negatively weighted) and 78 up-regulated (positively weighted) human probe sets. This gene list, hereafter referred to as “BCL9/9L-KO signature”, is shown in Table S1 and was used for probing human CRC patient databases. (D) Kaplan–Meier estimates for DFS and OS of CRC patients from one of the largest public human CRC microarray databases (Affymetrix HG U133 Plus 2.0; GSE17538). DFS and OS of patients with higher (black) or lower (red) expression of the BCL9/9L-KO signature after subdividing patients according to a median split. (E) Meta-analysis of all CRC patient microarray databases. The relative strength of association of the BCL9/9L-KO signature with DFS and OS is presented as forest plots of HRs for one inter-quartile unit of the signature score.

To compare Bcl9/9l-dependent phenotypes between the two tumor models we first assessed expression of the genes that were most strongly down-regulated in AOM/DSS tumors lacking Bcl9/9l (hereafter WNT/stemness/EMT reference genes) (Deka et al., 2010) (Fig. S1A). Similar to AOM/DSS tumors, ablation of Bcl9/9l in Apc/Kras colon tumors also resulted in down-regulation of WNT/stemness/EMT reference genes (Fig. S1B). Like AOM/DSS tumors, Apc/Kras colon tumors also expressed vimentin within tumor cells, albeit to a somewhat lesser extent, and typically the basement membrane underlying vimentin expressing tumor cells appeared to be discontinuous. In both tumor models deletion of Bcl9/9l resulted in complete abrogation of vimentin expression and restored basement membrane integrity (Fig. S1C, D). These findings clearly suggested that ablation of Bcl9/9l in Apc/Kras tumors by and large phenocopies gene expression changes observed in the AOM/DSS model. It is noteworthy that mice bearing Bcl9/9l-KO Apc/Kras tumors survived significantly longer than controls, presumably due to a delay in tumor growth (Fig. S1E, F).

To extend the gene expression analysis beyond WNT/stemness/EMT reference genes and establish a robust signature of overlapping changes across these CRC models, we subjected wild-type and Bcl9/9l-ablated tumor samples from AOM/DSS and Apc/Kras tumors to RNA sequencing. Bcl9/9l-dependent gene expression changes correlated positively and highly significantly across the two tumor models (Fig. 1B).

3.2. A BCL9/9L-knockout Signature is Associated With Improved Progression-free and Overall CRC Patient Survival

The list of genes that were differentially expressed upon ablation of Bcl9/9l and common to both the RNA sequencing DSS and/DSS and Apc/Kras tumors comprised 359 down- and 107 up-regulated genes (Fig. 1C), for which 300 and 78 human homologs, respectively were identified (hereafter BCL9/9L-KO signature) (Table S1). This BCL9/9L-KO signature was used to probe the largest public human CRC microarray database (Affymetrix HG U133 Plus 2.0) containing both disease free (DFS) and overall survival (OS) information (Fig. 1D). Kaplan–Meier analysis of patient samples subdivided into two groups by median split revealed a striking positive association of the BCL9/9L-KO signature with a more favorable outcome (Fig. 1D). Additional human CRC databases were probed analogously, including a set of 752 stage II and III samples from the PETACC-3 clinical trial (Van Cutsem et al., 2009), which was generated using a different platform (see Experimental Procedures) and contained high quality clinical follow-up data (Popovici et al., 2012). Consistently, and across different platforms, these analyses corroborated that hazard of relapse or death was highly significantly reduced in patients with tumor profiles associated with the BCL9/9L-KO signature (Fig. 1E). Remarkably, the prognostic capacity of the BCL9/9L-KO signature was observed irrespective of tumor stage and independent of molecular parameters as revealed by multivariable analysis (Table S2). Specifically, there was no important effect modulation by other variables such as BRAF, KRAS or P53 mutations, or the microsatellite instability status.

3.3. Loss of BCL9/9L Results in Shifting the Stemness to Differentiation Gene Expression Balance Towards Differentiation

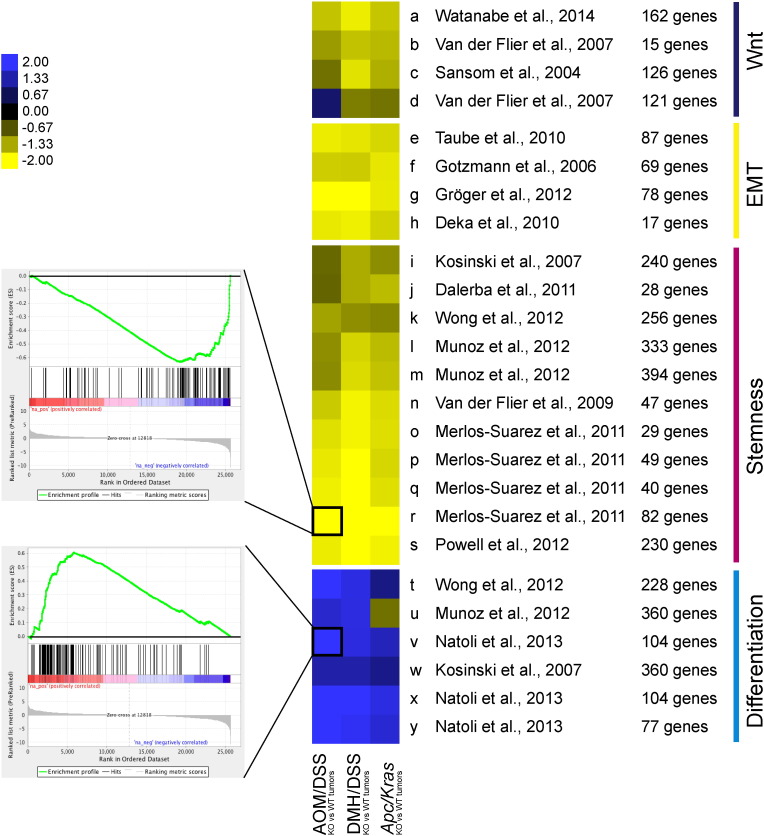

To assess to what extent the prognostic value of the BCL9/9L-KO signature could be attributed to biologic functions, a wide array of published gene sets relating to intestinal WNT targets, stemness, EMT, and differentiation (Fig. 2, Table S3) was assessed by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (Subramanian et al., 2005) for enrichment in the transcriptomes of BCL9/9L-KO tumors. Each gene set was assessed individually as exemplified in the two insets, given a score after normalization for the size of the relevant set, and the scores represented as a heatmap (Fig. 2). Unambiguously, all examined WNT- stemness-, and EMT-related gene sets were negatively enriched, while differentiation-related sets were positively enriched within the transcriptomes of knockout tumors. Remarkably, consistent enrichment scores were observed across the three mouse CRC datasets, i.e. the new RNA sequencing sets from AOM/DSS and Apc/Kras tumors, and our previously reported Affymetrix microarray data set from DMH/DSS tumors (GSE21576) (Deka et al., 2010).See Fig. 1

Fig. 2.

Loss of Bcl9/9l is correlated with loss of WNT, EMT and stemness signatures, and increased differentiation traits. Heatmap of normalized GSEA scores in transcriptomes of Bcl9/9l-KO versus wild-type tumors from three different models. Gene signatures relating to intestinal stemness, WNT, EMT or differentiation were selected from the literature. Each row represents a gene set whose composition and origin are listed in Table S3. Each field depicts a single GSEA of the respective gene signature in the corresponding tumor dataset; insets show examples of a negatively and positively enriched signature, respectively. The color code represents normalized enrichment scores. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Loss of Bcl9/9l is correlated with loss of WNT, EMT and stemness signatures, and increased differentiation traits. Heatmap of normalized GSEA scores in transcriptomes of Bcl9/9l-KO versus wild-type tumors from three different models. Gene signatures relating to intestinal stemness, WNT, EMT or differentiation were selected from the literature. Each row represents a gene set whose composition and origin are listed in Table S3. Each field depicts a single GSEA of the respective gene signature in the corresponding tumor dataset; insets show examples of a negatively and positively enriched signature, respectively. The color code represents normalized enrichment scores.

Importantly, a list comprising all genes common to the individual functional gene sets and the BCL9/9L-KO signature (highlighted in Table S1) proved correlated with patient outcome similar to the entire BCL9/9L-KO signature (Fig. S2), corroborating that genes comprised in these WNT-, stemness-, EMT-, and differentiation-related gene sets by and large determined its prognostic value.

3.4. The BCL9/9L-KO Signature is Negatively Associated With High Stemness CRC Subtypes

Recently, gene expression subtypes of CRC have been reported, which are associated with patient outcome (Budinska et al., 2013, Guinney et al., 2015, Marisa et al., 2013, Sadanandam et al., 2013). We classified patient samples of the PETACC dataset according to the molecular subtypes defined by Sadanandam et al. (2013) (Fig. 3A) and Marisa et al. (2013)) (Fig. 3B) and consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) recently reported by the Colorectal Cancer Subtyping Consortium (CRCSC) (Guinney et al., 2015) (Fig. 3C) and asked to what extent the BCL9/9L-KO signature was enriched in any of these subtypes. Remarkably, there was a highly significant negative association of the BCL9/9L-KO signature with the “Stem-like” (Sadanandam et al., 2013), “C4/CSC” (Marisa et al., 2013) and “CMS4/mesenchymal” (Guinney et al., 2015)subtypes that were all characterized by high stemness and/or EMT traits and associated with poor prognosis. BCL9/9L were expressed above background across all patient samples, and to our knowledge there are no reports on inactivating BCL9/9L mutations in human tumors. The BCL9/9L-KO signature was therefore not expected to show strong positive enrichment in any of the other subtypes. It is noteworthy that there was a significant correlation between expression of stemness traits and BCL9L and to a lesser extent BCL9 gene expression levels (Fig. S3A). Accordingly, BCL9L, but not BCL9 expression was significantly correlated to poor outcome in most databases (Fig. S3B).

Fig. 3.

Association between the BCL9/9L-KO signature and stemness subtypes in independent CRC classifications. (A) Association of the BCL9/9L-KO signature with five CRC subtypes defined by Sadanandam et al. (2013) in 752 patients from the PETACC-3 clinical trial (Marisa et al., 2013, Sampietro et al., 2006). Patients with BCL9/9L-KO signature scores below the median are shown in red (BCL9/9L-WT-like), those with scores above the median are shown in black (BCL9/9L-KO-like). The insets display the results of a Wilcoxon test evaluating the difference between the median of the BCL9/9L-KO signature score for each subtype and the median of all patients (2.455313). (B) Analogous analysis to (a) with the CRC subtypes described by Marisa et al. (2013). (C) Analogous analysis to (a) with the consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) described by the Colorectal Cancer Subtyping Consortium (Guinney et al., 2015).

3.5. BCL9/9L-ablation in Intestinal Organoids Results in Increased Differentiation and Loss of Tumorigenicity

Recently, conditions have been established allowing to culture and passage intestinal crypt-derived epithelial organoids, which recapitulate the differentiation hierarchy of the small intestinal epithelium (Sato et al., 2011a, van Es and Clevers, 2015). We isolated and cultured Bcl9/9l-wild-type or Bcl9/9l-KO small intestinal crypts from Apc/Kras mice (Janssen et al., 2006), initially in the presence of R-spondin and EGF to stimulate the WNT pathway and expand the cultures as described (Sato et al., 2011a). After five days these growth factors were withdrawn to select for organoids that had lost the remaining wild-type Apc allele and had therefore become independent of external WNT stimulation (Sato et al., 2011a) (Fig. 4A). Apc/Kras-driven crypt cultures grew mostly as undifferentiated spheres (Fig. 4B), as described for mutant adenoma-derived organoids (Sato et al., 2011a). In the absence of Bcl9/9l, however, budding structures resembling normal intestinal organoids (Sato et al., 2011b) were vastly predominant over spherical organoids (Fig. 4B, C), indicative of a more differentiated state. The Bcl9/9l status was verified by qRT-PCR and confirmed that there was no selection of escaping Bcl9/9l-wild-type organoids within Bcl9/9l-KO cultures (Fig. S4A). Expression of the Bcl9/9l-dependent WNT/stemness/EMT reference genes identified in AOM/DSS colon tumors proved at least in part down-regulated in Bcl9/9-KO organoids (Fig. S4B–D), despite their small intestinal origin, and conversely, intestinal differentiation markers including villin and keratin 20(Dow et al., 2015) were up-regulated (Fig. S4E). Both wild-type and Bcl9/9l-KO organoid cultures grew at similar proliferation rates (Fig. S4F), while maintaining their distinct morphology over serial passaging.

Next, we assessed the tumorigenicity of Bcl9/9l-wild-type or Bcl9/9l-KO Apc/Kras organoids in NOD scid gamma mice. Whereas Bcl9/9l-wild-type subcutaneous allografts grew exponentially, Bcl9/9l-KO grew only for up to one week before tumors started regressing and became virtually impalpable (Fig. 4D). Allografts were collected at day 26 after injection when tumors had reached legally admitted size limits. As expected from tumor palpation, wild-type grafts weighed substantially more than Bcl9/9l-KO counterparts (Fig. 4E). Macroscopically, some wild-type tumors showed signs of rapid growth with central necrosis, whereas Bcl9/9l-KO grafts appeared as scar tissue (Fig. 4F, G). Histologically, wild-type grafts appeared as low-grade adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin, with high resemblance to human CRC, whereas Bcl9/9l-KO grafts contained only small islets of highly differentiated epithelial structures reminiscent of normal intestinal epithelium, which were surrounded by fibroblastic and inflammatory tissue, compatible with ongoing tumor resorption and concomitant scarring (Fig. 4H).

3.6. Induced Bcl9/9l Ablation in Wild-type Intestinal Organoids and Pre-established Tumors Phenocopies Constitutive Bcl9/9l Inactivation

The strong association of Bcl9/9l-dependent phenotypes with CRC patient outcome prompted us to address to what extent ablating Bcl9/9l in wild-type intestinal organoids or pre-established wild-type tumors was able to recapitulate the observed gene expression changes and thereby validate the BCL9/9L-β-catenin interaction as a potential therapeutic target. 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) exposure of intestinal organoids derived from of Apc/Kras mice expressing R26-CreERT (Ventura et al., 2007) and carrying Bcl9/9lloxP/loxP alleles resulted in a rapid shift in the ratio between sphere-like and budding organoids, with progressive disappearance of spheroid structures over 48 h, whereas the proportion of sphere-like organoids remained stable in the untreated controls (Fig. 5A–C). This phenotype was not observed in 4-OHT treated wild-type spheroids (Fig. 5C) and correlated with Bcl9/9l expression levels (Fig. S5A).

Fig. 5.

Induced loss of Bcl9/9l recapitulates constitutive phenotypes in vitro and in vivo. (A) Organoid cultures were established from Apc/Kras Bcl9/9lloxP/loxP mice carrying a R26-CreERT2 transgene as described in Fig. 4A. Bcl9/9l ablation was induced through addition of 4-OHT to the culture medium for 5 days. (B) Representative phase-contrast images 7 days after starting the 4-OHT treatment. Scale bar: 100 μM. (C) Quantification of spheroids in 4-OHT-treated R26-CreERT Apc/Kras Bcl9/9lloxP/loxP cultures as compared to untreated or R26-CreERT-negative controls. (D) Inducible ablation of Bcl9/9l proteins was investigated in vivo in AOM/DSS tumors. The mice were injected intraperitoneally with AOM and subjected to three cycles of DSS administration through the drinking water. Gene deletion was induced when mice showed symptoms of intestinal bleeding, typically 15 weeks after tumor induction. (E) Tamoxifen induced villin-CreERT2-mediated recombination resulted after 14 days in patchy Bcl9/9l deletion, possibly due to uneven tamoxifen permeation. Consecutive tissue sections revealed a remarkable overlap between absence of Bcl9 and vimentin staining and basement membrane integrity; inversely, areas of residual Bcl9 expression (asterisk) correlated with the presence of epithelial vimentin. (F) Induction of villin-CreERT2 resulted in approx. 2-fold decrease of Bcl9/9l transcripts in bulk tumor mRNA two weeks after the first tamoxifen injection, reflecting approx. 50% chimerism between wild-type and Bcl9/9l-null tumor tissue. 14 out of 18 WNT/stemness/EMT reference genes (Fig. S1A) were significantly down-regulated in these tumor samples, to an extent that was proportional to the decrease of BCL9/9L transcripts.

Analogously, induction of Bcl9/9l deletion in pre-established AOM/DSS tumors (Fig. 5D) resulted, as early as two weeks after tamoxifen-mediated villin-CreERT activation, in phenotypic changes that by and large recapitulated those observed in constitutively Bcl9/9l-ablated tumors (Fig. 5E, F and Fig. S5B). One of the hallmarks of wild-type AOM/DSS tumors is a widespread expression of vimentin within the tumor epithelium paired with discontinuous basement membrane staining (Fig. S1C, upper panel). Upon Bcl9/9l ablation vimentin expression was completely abrogated and the underlying basement membrane regained normal looking continuity (Deka et al., 2010) (Fig. S1C, lower panel). These striking phenotypic changes were recapitulated upon conditional Bcl9/9l-ablation. Tumor areas with residual vimentin expression also showed residual Bcl9 protein, pointing to uneven tamoxifen permeation into tumor tissue and indicating that these Bcl9/9l-dependent phenotypic changes are cell autonomous (Fig. 5E). Despite residual Bcl9/9l expression, 14 out of the 18 WNT/stemness/EMT reference genes (Fig. S1A) were down-regulated significantly and proportionally to Bcl9/9l expression levels (Fig. 5F).

Taken together these findings demonstrated that Bcl9/9l-dependent phenotypic changes are readily inducible in wild-type organoids as well as pre-established AOM/DSS tumors.

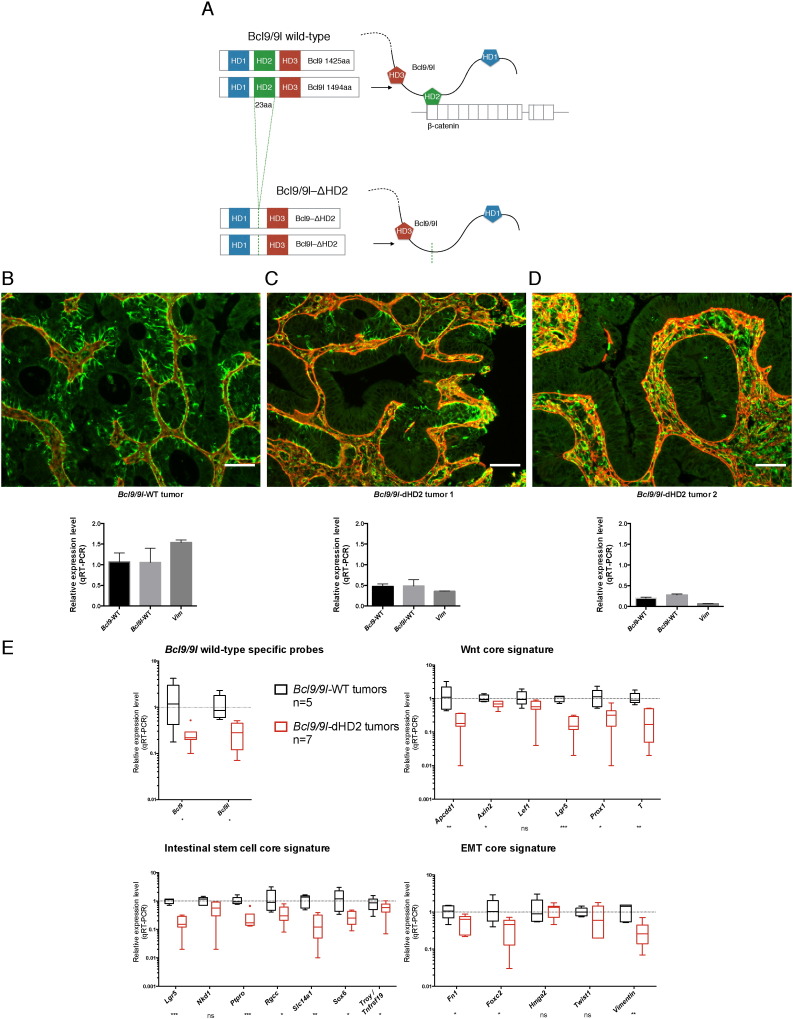

3.7. Genetic Mimicry of a Putative BCL9/9L-β-catenin Inhibitor

To further validate the BCL9/9L-β-catenin interaction as a potential therapeutic target and simulate its pharmacologic inhibition, we combined Bcl9/9l knock-in alleles, in which only the β-catenin interaction domains (HD2) were deleted (Cantù et al., 2014), with conditional Bcl9/9l-null alleles (Deka et al., 2010) to generate villin-CreERT2-Bcl9/9lloxP/∆ HD2 mice (Fig. 6A). AOM/DSS tumors were generated prior to deleting the wild-type alleles as described in Fig. 5D. Similar to tumors with induced Bcl9/9l ablation (Fig. 5E, F), tamoxifen administration resulted in loss of vimentin expression in tumor areas that also showed restored basement membrane integrity (Fig. 6B–D). Accordingly, expression of WNT/stemness/EMT reference genes was reduced proportionally to Bcl9/9l expression (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

Deletion of the Bcl9/9l-β-catenin interaction domain recapitulates the loss of Bcl9/9l phenotype. (A) A knock-in mouse strain with HD2 deletions of both Bcl9/9l proteins, which were shown to selectively lack the ability to interact with β-catenin (Cantù et al., 2014), was intercrossed with villin-CreERT2-Bcl9/9lloxP/loxP mice (Deka et al., 2010), generating mice heterozygous for both ∆ HD2 and Bcl9/9lloxP/loxP alleles. AOM/DSS tumors were generated as described in Fig. 5D. Upon tamoxifen administration these tumors became chimeric for tumor tissue, in which either only Bcl9/9l-∆ HD2 was expressed, or Bcl9/9l-∆ HD2 was co-expressed with undeleted Bcl9/9lloxP/loxP alleles. (B–D) Deletion of the wild-type Bcl9/9l alleles resulted in virtual abrogation of vimentin (green) in tumor epithelium that became surrounded with a contiguous basement membrane (laminin, red), as observed upon constitutive or induced ablation of Bcl9/9l alleles (Fig. S1 and Fig. 5). Antibodies recognizing wild-type, but not ∆ HD2 Bcl9 proteins were unavailable. Still, tumor samples with different proportions of wild-type and Bcl9/9l-deleted tissue suggested a correlation between Bcl9/9l expression and vimentin protein and transcript levels (C, D). The same tumor samples were used for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and for determining Bcl9/9l transcript levels (n = 1; mean and SE values relate to technical replicates). Scale bar: 50 μm. (E) Two weeks after the first tamoxifen injection deletion of wild-type Bcl9/9l in presence of Bcl9/9l-∆ HD2 resulted in significant down-regulation of 14 out of 18 WNT/stemness/EMT reference genes that was proportional to the residual level of wild-type Bcl9/9l, thereby phenocopying the induced loss of Bcl9/9l (Fig. 5F).

Importantly, these experiments unequivocally established that Bcl9/9l-KO phenotypes observed in CRC models were indeed mediated by the Bcl9/9l-β-catenin complex and were not caused by β-catenin-independent effects of Bcl9/9l as they have recently been reported to occur during lens development (Cantù et al., 2014).

4. Discussion

It is accepted that the cellular hierarchy along the crypt villus axis in the intestinal epithelium is maintained through a WNT signaling gradient (Clevers, 2013, Sato et al., 2011b), yet the mechanisms underlying the translation of signaling strength into cell type specification remain largely unexplored. Clearly, the identity of ISCs depends critically upon high WNT signaling. A transcriptional response to high WNT ligand concentrations, as they occur in the ISC niche where Paneth cells act as a ligand source, has recently been described to trigger an autoactivation loop of the transcription factor Ascl2, which together with the β-catenin/TCF core complex activates genes that are essential to establishing a stem cell state (Schuijers et al., 2015). We previously showed that the BCl9/9L-β-catenin arm of WNT signaling contributes to maintaining this stem cell state (Deka et al., 2010).

Here we extended these studies and corroborated our observations in an independent mouse CRC model driven by oncogenic Kras and loss of Apc, providing a basis for establishing an unbiased, robust signature of Bcl9/9l-dependent genes (Fig. 1A–C).The resulting BCL9/9L-KO signature of human homologs proved of remarkable prognostic value when used to probe databases of human CRC transcriptomes, clearly revealing that patients with tumor profiles resembling the KO signature had a markedly better prognosis (Fig. 1D, E). GSEA revealed that published gene sets relating to WNT signaling, intestinal stemness, and mesenchymal (EMT) traits were consistently negatively enriched within the individual transcriptomes of Bcl9/9l-KO mouse tumors, whereas gene sets relating to differentiation were positively enriched (Fig. 2). Importantly, the subset of genes common to both, these public gene sets and the unbiased BCL9/9L-KO signature proved of virtually identical prognostic value as the entire KO signature (Fig. S2). Altogether these findings clearly suggest that the prognostic value of the BCL9/9L-KO signature is by and large due to the attenuation of stemness and mesenchymal, and a concomitant gain in differentiation traits, as a consequence of diminished WNT signaling. Remarkably, the BCL9/9L-KO signature consistently correlated negatively with subtypes characterized by high stemness traits and poorest outcome (Fig. 3).

To assess the functional impact of modulating BCL9/9L expression in an in vitro cell based-model we turned to a panel of human CRC cell lines that we had characterized previously (Christensen et al., 2012). While expression of stemness traits in these cell lines correlated significantly with the recently described poor prognosis features (Budinska et al., 2013, Guinney et al., 2015, Marisa et al., 2013, Sadanandam et al., 2013), we did not notice any significant correlation with BCL9/9L expression. Also, xenografts of both stemness-high cell lines such as SW480, or more differentiated lines such as HT29 resulted in high-grade tumors with little resemblance to human CRC (data not shown), which typically are of much lower grade. We therefore focused our efforts on a recently described oncogenic intestinal organoid model harboring Apc and Kras double mutations (van Es and Clevers, 2015), which upon allografting produced low grade tumors strongly resembling human CRC (Fig. 4H) and in which we introduced conditional Bcl9/9l knockout alleles. Apc/Kras-driven Bcl9/9l-null intestinal organoids were unable to maintain a sphere-like phenotype and readily evolved towards more differentiated budding structures, thereby completely losing their tumorigenicity in allograft assays (Fig. 4), in accordance with the notion that Bcl9/9l in the CRC models is critical for upholding stemness traits.

Collectively, the highly significant impact of Bcl9/9l-ablation on expression of stemness traits in mouse CRC models paired with the relatively mild phenotype in the unchallenged normal epithelium renders the BCL9/9L-β-catenin interface an attractive potential therapeutic target to target cancer stem cells (CSC) in human CRC. It should be emphasized that BCL9/9L were expressed across all patient samples (Fig. S2). Pharmacologic inhibition of the BCL9/9L-β-catenin interaction might therefore be of even greater benefit than suggested by the correlation of the BCL9/9L-KO signature with more favorable outcome (Fig. 1D, E).

To further validate the BCL9/9L-β-catenin complex as a potential target we first demonstrated using loxP-flanked alleles and tamoxifen inducible CreERT2 that Bcl9/9l-KO phenotypes could be rapidly induced in intestinal organoids and also in pre-established AOM/DSS tumors (Fig. 5). Our studies consistently made use of compound loss-of function mutants, preventing addressing to what extent Bcl9 and Bcl9l paralogs, which share the same highly conserved homology domains(Brembeck et al., 2006), are functionally redundant. In most CRC databases stemness traits correlated with BCL9L, but not BCL9 expression, pointing to potentially different roles (Fig. S3B). It is of note, however, that knock-in mice in which the β-catenin binding sites of both Bcl9 and Bcl9l were selectively deleted, phenocopied the loss of the entire proteins, demonstrating unmistakably that the observed loss-of-Bcl9/9l phenotypes were mediated by β-catenin. This was important as recently β-catenin-independent functions of Bcl9/9l have been discovered (Cantù et al., 2014) (Fig. 6). Furthermore, these experiments mimicked the action of a potential inhibitor of the BCL9/9L-β-catenin interaction, which in principle appears to be drugable by small molecules (de la Roche et al., 2012, Hoggard et al., 2015, Sampietro et al., 2006) or peptides (Takada et al., 2012).

The mechanisms underlying the transcriptional co-activation function of Bcl9/9 l, which appears to be critical for sustaining stemness-related target genes (Fig. 2, Table S3), but not WNT targets involved in cell proliferation (Fevr et al., 2007, Ireland et al., 2004, Korinek et al., 1998, van Es et al., 2012), remain to be explored. Bcl9/9l proteins have been described to function as adapters that recruit partner proteins such as Pygopus (Pygo), which eventually may bridge to and modulate the general transcriptional activation complex at the C-terminus of β-catenin (Kramps et al., 2002, Mosimann et al., 2009, Valenta et al., 2012). It remains unclear whether Bcl9/9l exerts its stemness maintenance effects through selective transcriptional modulation of WNT target gene subsets, or through non-selectively enhancing WNT-β-catenin transcriptional output, resulting in threshold-dependent triggering of amplifying loops as described for Ascl2 (Schuijers et al., 2015). Pharmacologic inhibition of the interaction of β-catenin with CBP, a component of the general transcriptional activation complex recruited to the C-terminus of β-catenin, has been reported to affect the balance between undifferentiated and differentiated cell states in various tumor models (Ring et al., 2014), supporting the possibility that general tempering of WNT signaling output might be sufficient for lessening stemness maintenance.

Establishment and maintenance of stemness in the ISC niche requires high WNT signaling. Mutational activation of WNT signaling in CRC results in transcriptional output possibly exceeding WNT responses observed in normal tissues (Rosin-Arbesfeld et al., 2003). Our findings are compatible with the notion of a direct relation between WNT signaling strength and stemness maintenance. They show that pruning WNT-mediated stemness maintenance as observed upon inactivation of Bcl9/9l affects the regenerative potential in both the normal intestinal epithelium as well in CRC. Whereas the former is tolerated, reducing the regenerative potential of tumors might prove sufficient to significantly impact relapse, in accordance with the CSC model (Zeuner et al., 2014). Combining such a stemness tuning strategy with an established CRC treatment protocol therefore represents a promising therapeutic strategy.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Fig. S1 Concordant Bcl9/9l-KO phenotypes in two independent mouse CRC models. (A) AOM/DSS tumors derived from constitutively Bcl9/9l-null as compared to wild-type gastrointestinal epithelium displayed highly reproducible gene expression changes involving genes associated with WNT signaling, stemness traits and EMT (Deka et al., 2010). Herein, genes with the strongest down-regulation in constitutively Bcl9/9l-ablated tumors were assembled into WNT-, stemness- and EMT-core signatures (WNT/stemness/EMT reference genes) that served as a reference for quantitation by qRT-PCR. (Note: 1190002H23Rik has recently been annotated as Rgcc). (B) Apc/Kras tumors lacking Bcl9/9l showed a significant down-regulation of 13 out of 18 WNT/stemness/EMT reference genes, thereby largely phenocopying the gene signature shift observed in the AOM/DSS CRC model (Fig. S1A). (C) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of wild-type and Bcl9/9l-null AOM/DSS tumors (left); Vimentin (green) and laminin (red) staining of consecutive sections of wild-type versus Bcl9/9l deleted AOM/DSS tumors (right). As described previously and reproduced here for comparison (Deka et al., 2010) villin-Cre-mediated constitutive deletion of Bcl9/9l resulted in virtual abrogation of vimentin protein expression in the tumor epithelium that became surrounded by a continuous underlying basement membrane, contrasting with its irregular appearance in wild- type vimentin-positive tumor epithelium. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of wild-type and Bcl9/9l-null Apc/Kras tumors (left); Vimentin (green) and laminin (red) staining of consecutive sections of wild-type versus Bcl9/9l deleted Apc/Kras tumors (right). (E) Median DFS of Apc/Kras tumor bearing mice. Bcl9/9l wild-type: 289d; Bcl9/9l-deleted: 440d; HR 0.31 (95% CI: 0.05–0.51). Mice were sacrificed in pairs, macroscopically inspected for the presence of colon tumors and classified as events or as censored (marks) for survival analysis. (F) Tumor statistics in the Apc/Kras tumor model. Ablation of Bcl9/9l resulted in significant, yet modest reduction in tumor size, but had no significant impact on tumor incidence and load. Error bars represent SEM.

Fig. S2 Contribution to patient outcome of functionally annotated genes within the BCL9/9L-KO signature. Forest plots of hazard ratios for DFS and OS for the genes contained in both, the individual gene sets in Fig. 2 and the BCL9/9L-KO signature. Relevant genes (marked in red in Table S1) contributed similarly to patient outcome as the entire BCL9/9L-KO signature (Fig. 1E).

Fig. S3 Correlation between BCL9/9L-KO signature and CRC stemness subtypes. (A) Correlation between BCL9L and BCL9 expression levels and the “Stem-like” signature from Sadanandam et al. (2013) in three patient data sets. Correlation and p-value were quantified by Pearson's r. (B) BCL9L, but not BCL9 expression was significantly correlated to poor outcome in most databases. Forest plots of HRs for DFS relating to expression of BCL9 or BCL9L.

Fig. S4 Expression of WNT/Stemness/EMT reference genes in intestinal organoids. (A–D) QRT-PCR analysis of Bcl9 and Bcl9l transcript levels and of Bcl9/9l-KO reference WNT/stemness/EMT gene sets (Fig. S1). (E) QRT-PCR analysis of intestinal differentiation markers. (F) Proliferation analysis after 96 h of growth, n = 6 for each genotype.

Fig. S5 Recapitulation of constitutive phenotypes upon induced Bcl9/9l ablation. (A) qRT PCR analysis of Bcl9 and Bcl9l transcript levels in untreated and 4-OHT treated mutant organoids. RNA was collected 7 days after starting 4-OHT treatment. (B) Similar to constitutively Bcl9/9l ablated AOM/DSS tumors (Deka et al., 2010), conditional Bcl9/9l ablation in established AOM/DSS tumors had no significant impact on tumor incidence and proliferation as assessed two weeks after the first tamoxifen injection.

BCL9/9L-KO signature components. Corresponding probe sets for Affymetrix HG U133 Plus 2.0 datasets and probe sets for the PETACC3 dataset are shown. Genes marked in red are comprised within the individual gene sets in Fig. 2 and were used for the outcome analysis in Fig. S3B.

Univariable and multivariable analysis of the BCL9/9L-KO signature with regard to patient outcome. Top: univariable and multivariable analysis of DFS and available pathological and molecular markers in GSE39528 patients. Bottom: multivariable analysis of DFS and OS in PETACC3 patients.

Components of GSEA in Fig. 3. Origin and composition of all individual gene sets that were subjected to GSEA in Fig. 3 (Dalerba et al., 2011, Deka et al., 2010, Gotzmann et al., 2006, Groger et al., 2012, Kosinski et al., 2007, Merlos-Suarez et al., 2011, Munoz et al., 2012, Natoli et al., 2013, Powell et al., 2012, Sansom et al., 2004, Taube et al., 2010, Van der Flier et al., 2007, van der Flier, et al., 2009, Watanabe et al., 2014, Wong et al., 2012).

List of qRT-PCR primers.

Supplementary Material

Author Contributions

A.M. planned and performed most of the experiments and contributed to writing the manuscript. P.A., D.B., M.D. and B.G. carried out bioinformatics analyses. C.C. generated HD-mutant knock-in mice. P.R. N.W., F.B., J.D., S.A., T.V. and M.B.M. carried out specific experiments. K.B. participated in experimental design. M.A. supervised the project and wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Mouse strains carrying villin-Cre, villin-CreERT2, Apc1638N and villin-KrasG12V alleles were kindly provided by Sylvie Robine, Institut Curie, Paris. We thank the Lemanic Animal Facility Network, the Mouse Pathology Facility of the University of Lausanne, and the Lausanne Genomic Technologies Facility for their support, Benoît Lhermitte, CHUV, Lausanne for histopathologic assessment of mouse tumors, and Felipe De Sousa E Melo, Genentech, San Francisco for assistance in intestinal organoid culture. This work was in part supported by the OTKA K 108655 grant and grants from the Swiss Cancer League, MD-PhD 02806-07-2011 (A.M.), the ISREC Foundation (P.A.) and the Sinergia program of the Swiss National Science Foundation, 136274 (F.B.).

References

- Anastas J.N., Moon R.T. WNT signalling pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013;13(1):11–26. doi: 10.1038/nrc3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biechele S., Cox B.J., Rossant J. Porcupine homolog is required for canonical Wnt signaling and gastrulation in mouse embryos. Dev. Biol. 2011;355(2):275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brack A.S., Murphy-Seiler F., Hanifi J. BCL9 is an essential component of canonical Wnt signaling that mediates the differentiation of myogenic progenitors during muscle regeneration. Dev. Biol. 2009;335(1):93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brembeck F.H., Rosario M., Birchmeier W. Balancing cell adhesion and Wnt signaling, the key role of beta-catenin. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2006;16(1):51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brembeck F.H., Schwarz-Romond T., Bakkers J. Essential role of BCL9-2 in the switch between beta-catenin's adhesive and transcriptional functions. Genes Dev. 2004;18(18):2225–2230. doi: 10.1101/gad.317604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budinska E., Popovici V., Tejpar S. Gene expression patterns unveil a new level of molecular heterogeneity in colorectal cancer. J. Pathol. 2013;231(1):63–76. doi: 10.1002/path.4212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantù C., Zimmerli D., Hausmann G. Pax6-dependent, but beta-catenin-independent, function of Bcl9 proteins in mouse lens development. Genes Dev. 2014;28(17):1879–1884. doi: 10.1101/gad.246140.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J., El-Gebali S., Natoli M. Defining new criteria for selection of cell-based intestinal models using publicly available databases. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:274–284. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H. The intestinal crypt, a prototype stem cell compartment. Cell. 2013;154(2):274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalerba P., Kalisky T., Sahoo D. Single-cell dissection of transcriptional heterogeneity in human colon tumors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29(12):1120–1127. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Roche M., Rutherford T.J., Gupta D. An intrinsically labile alpha-helix abutting the BCL9-binding site of beta-catenin is required for its inhibition by carnosic acid. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:680. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deka J., Wiedemann N., Anderle P. Bcl9/Bcl9l Are Critical for Wnt-Mediated Regulation of Stem Cell Traits in Colon Epithelium and Adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 2010;70(16):6619–6628. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow L.E., O'Rourke K.P., Simon J. Apc restoration promotes cellular differentiation and reestablishes crypt homeostasis in colorectal cancer. Cell. 2015;161(7):1539–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon E.R., Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61(5):759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2188735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fevr T., Robine S., Louvard D. Wnt/beta-catenin is essential for intestinal homeostasis and maintenance of intestinal stem cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27(21):7551–7559. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01034-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J., Jiang M., Mirando A.J. Reciprocal regulation of Wnt and Gpr177/mouse Wntless is required for embryonic axis formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106(44):18598–18603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904894106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotzmann J., Fischer A.N., Zojer M. A crucial function of PDGF in TGF-beta-mediated cancer progression of hepatocytes. Oncogene. 2006;25(22):3170–3185. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greten F.R., Eckmann L., Greten T.F. IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118(3):285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groger C.J., Grubinger M., Waldhor T. Meta-analysis of gene expression signatures defining the epithelial to mesenchymal transition during cancer progression. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinney J., Dienstmann R., Wang X. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nm.3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmans R., Stadeli R., Basler K. Pygopus and legless provide essential transcriptional coactivator functions to armadillo/beta-catenin. Curr. Biol. 2005;15(13):1207–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoggard L.R., Zhang Y., Zhang M. Rational Design of Selective Small-Molecule Inhibitors for beta-Catenin/B-Cell Lymphoma 9 Protein-Protein Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137(38):12249–12260. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland H., Kemp R., Houghton C. Inducible Cre-mediated control of gene expression in the murine gastrointestinal tract: effect of loss of beta-catenin. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(5):1236–1246. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.020. http://dx.doi.org/S0016508504004500 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen K.P., Alberici P., Fsihi H. APC and oncogenic KRAS are synergistic in enhancing Wnt signaling in intestinal tumor formation and progression. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(4):1096–1109. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korinek V., Barker N., Moerer P. Depletion of epithelial stem-cell compartments in the small intestine of mice lacking Tcf-4. Nat. Genet. 1998;19(4):379–383. doi: 10.1038/1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski C., Li V.S., Chan A.S. Gene expression patterns of human colon tops and basal crypts and BMP antagonists as intestinal stem cell niche factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104(39):15418–15423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707210104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramps T., Peter O., Brunner E. Wnt/wingless signaling requires BCL9/legless-mediated recruitment of pygopus to the nuclear beta-catenin-TCF complex. Cell. 2002;109(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00679-7. http://dx.doi.org/S0092867402006797 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Birkbak N.J., Gyorffy B. Jetset: selecting the optimal microarray probe set to represent a gene. BMC Bioinf. 2011;12:474. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani M., Carrasco D.E., Zhang Y. BCL9 Promotes Tumor Progression by Conferring Enhanced Proliferative, Metastatic, and Angiogenic Properties to Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2009 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marisa L., de Reynies A., Duval A. Gene expression classification of colon cancer into molecular subtypes: characterization, validation, and prognostic value. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlos-Suarez A., Barriga F.M., Jung P. The intestinal stem cell signature identifies colorectal cancer stem cells and predicts disease relapse. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(5):511–524. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosimann C., Hausmann G., Basler K. Beta-catenin hits chromatin: regulation of Wnt target gene activation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10(4):276–286. doi: 10.1038/nrm2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz J., Stange D.E., Schepers A.G. The Lgr5 intestinal stem cell signature: robust expression of proposed quiescent '+4' cell markers. EMBO J. 2012;31(14):3079–3091. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natoli M., Christensen J., El-Gebali S. The role of CDX2 in Caco-2 cell differentiation. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013;85(1):20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufert C., Becker C., Neurath M.F. An inducible mouse model of colon carcinogenesis for the analysis of sporadic and inflammation-driven tumor progression. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2(8):1998–2004. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L.V., Vanner R., Dirks P. Cancer stem cells: an evolving concept. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12(2):133–143. doi: 10.1038/nrc3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovici V., Budinska E., Tejpar S. Identification of a poor-prognosis BRAF-mutant-like population of patients with colon cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30(12):1288–1295. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell A.E., Wang Y., Li Y. The pan-ErbB negative regulator Lrig1 is an intestinal stem cell marker that functions as a tumor suppressor. Cell. 2012;149(1):146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring A., Kim Y.M., Kahn M. Wnt/catenin signaling in adult stem cell physiology and disease. Stem Cell Rev. 2014;10(4):512–525. doi: 10.1007/s12015-014-9515-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosin-Arbesfeld R., Cliffe A., Brabletz T. Nuclear export of the APC tumour suppressor controls beta-catenin function in transcription. EMBO J. 2003;22(5):1101–1113. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadanandam A., Lyssiotis C.A., Homicsko K. A colorectal cancer classification system that associates cellular phenotype and responses to therapy. Nat. Med. 2013;19(5):619–625. doi: 10.1038/nm.3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampietro J., Dahlberg C.L., Cho U.S. Crystal structure of a beta-catenin/BCL9/Tcf4 complex. Mol. Cell. 2006;24(2):293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom O.J., Reed K.R., Hayes A.J. Loss of Apc in vivo immediately perturbs Wnt signaling, differentiation, and migration. Genes Dev. 2004;18(12):1385–1390. doi: 10.1101/gad.287404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Stange D.E., Ferrante M. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett's epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., van Es J.H., Snippert H.J. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature. 2011;469(7330):415–418. doi: 10.1038/nature09637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuijers J., Junker J.P., Mokry M. Ascl2 Acts as an R-spondin/Wnt-Responsive Switch to Control Stemness in Intestinal Crypts. Cell Stem Cell. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102(43):15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16199517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada K., Zhu D., Bird G.H. Targeted Disruption of the BCL9/beta-Catenin Complex Inhibits Oncogenic Wnt Signaling. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4(148):148ra117. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taketo M.M., Edelmann W. Mouse models of colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(3):780–798. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.049. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19263594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taube J.H., Herschkowitz J.I., Komurov K. Core epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition interactome gene-expression signature is associated with claudin-low and metaplastic breast cancer subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107(35):15449–15454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004900107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenta T., Hausmann G., Basler K. The many faces and functions of beta-catenin. EMBO J. 2012;31(12):2714–2736. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cutsem E., Labianca R., Bodoky G. Randomized phase III trial comparing biweekly infusional fluorouracil/leucovorin alone or with irinotecan in the adjuvant treatment of stage III colon cancer: PETACC-3. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27(19):3117–3125. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Flier L.G., Sabates-Bellver J., Oving I. The Intestinal Wnt/TCF Signature. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(2):628–632. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Flier L.G., van Gijn M.E., Hatzis P. Transcription factor achaete scute-like 2 controls intestinal stem cell fate. Cell. 2009;136(5):903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Es J.H., Clevers H. Generation and Analysis of Mouse Intestinal Tumors and Organoids Harboring APC and K-Ras Mutations. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1267:125–144. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2297-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Es J.H., Haegebarth A., Kujala P. A critical role for the Wnt effector Tcf4 in adult intestinal homeostatic self-renewal. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012;32(10):1918–1927. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06288-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura A., Kirsch D.G., McLaughlin M.E. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature. 2007;445(7128):661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature05541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K., Biesinger J., Salmans M.L. Integrative ChIP-seq/microarray analysis identifies a CTNNB1 target signature enriched in intestinal stem cells and colon cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong V.W., Stange D.E., Page M.E. Lrig1 controls intestinal stem-cell homeostasis by negative regulation of ErbB signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14(4):401–408. doi: 10.1038/ncb2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuner A., Todaro M., Stassi G. Colorectal cancer stem cells: From the crypt to the clinic. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(6):692–705. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Concordant Bcl9/9l-KO phenotypes in two independent mouse CRC models. (A) AOM/DSS tumors derived from constitutively Bcl9/9l-null as compared to wild-type gastrointestinal epithelium displayed highly reproducible gene expression changes involving genes associated with WNT signaling, stemness traits and EMT (Deka et al., 2010). Herein, genes with the strongest down-regulation in constitutively Bcl9/9l-ablated tumors were assembled into WNT-, stemness- and EMT-core signatures (WNT/stemness/EMT reference genes) that served as a reference for quantitation by qRT-PCR. (Note: 1190002H23Rik has recently been annotated as Rgcc). (B) Apc/Kras tumors lacking Bcl9/9l showed a significant down-regulation of 13 out of 18 WNT/stemness/EMT reference genes, thereby largely phenocopying the gene signature shift observed in the AOM/DSS CRC model (Fig. S1A). (C) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of wild-type and Bcl9/9l-null AOM/DSS tumors (left); Vimentin (green) and laminin (red) staining of consecutive sections of wild-type versus Bcl9/9l deleted AOM/DSS tumors (right). As described previously and reproduced here for comparison (Deka et al., 2010) villin-Cre-mediated constitutive deletion of Bcl9/9l resulted in virtual abrogation of vimentin protein expression in the tumor epithelium that became surrounded by a continuous underlying basement membrane, contrasting with its irregular appearance in wild- type vimentin-positive tumor epithelium. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of wild-type and Bcl9/9l-null Apc/Kras tumors (left); Vimentin (green) and laminin (red) staining of consecutive sections of wild-type versus Bcl9/9l deleted Apc/Kras tumors (right). (E) Median DFS of Apc/Kras tumor bearing mice. Bcl9/9l wild-type: 289d; Bcl9/9l-deleted: 440d; HR 0.31 (95% CI: 0.05–0.51). Mice were sacrificed in pairs, macroscopically inspected for the presence of colon tumors and classified as events or as censored (marks) for survival analysis. (F) Tumor statistics in the Apc/Kras tumor model. Ablation of Bcl9/9l resulted in significant, yet modest reduction in tumor size, but had no significant impact on tumor incidence and load. Error bars represent SEM.

Fig. S2 Contribution to patient outcome of functionally annotated genes within the BCL9/9L-KO signature. Forest plots of hazard ratios for DFS and OS for the genes contained in both, the individual gene sets in Fig. 2 and the BCL9/9L-KO signature. Relevant genes (marked in red in Table S1) contributed similarly to patient outcome as the entire BCL9/9L-KO signature (Fig. 1E).

Fig. S3 Correlation between BCL9/9L-KO signature and CRC stemness subtypes. (A) Correlation between BCL9L and BCL9 expression levels and the “Stem-like” signature from Sadanandam et al. (2013) in three patient data sets. Correlation and p-value were quantified by Pearson's r. (B) BCL9L, but not BCL9 expression was significantly correlated to poor outcome in most databases. Forest plots of HRs for DFS relating to expression of BCL9 or BCL9L.

Fig. S4 Expression of WNT/Stemness/EMT reference genes in intestinal organoids. (A–D) QRT-PCR analysis of Bcl9 and Bcl9l transcript levels and of Bcl9/9l-KO reference WNT/stemness/EMT gene sets (Fig. S1). (E) QRT-PCR analysis of intestinal differentiation markers. (F) Proliferation analysis after 96 h of growth, n = 6 for each genotype.

Fig. S5 Recapitulation of constitutive phenotypes upon induced Bcl9/9l ablation. (A) qRT PCR analysis of Bcl9 and Bcl9l transcript levels in untreated and 4-OHT treated mutant organoids. RNA was collected 7 days after starting 4-OHT treatment. (B) Similar to constitutively Bcl9/9l ablated AOM/DSS tumors (Deka et al., 2010), conditional Bcl9/9l ablation in established AOM/DSS tumors had no significant impact on tumor incidence and proliferation as assessed two weeks after the first tamoxifen injection.

BCL9/9L-KO signature components. Corresponding probe sets for Affymetrix HG U133 Plus 2.0 datasets and probe sets for the PETACC3 dataset are shown. Genes marked in red are comprised within the individual gene sets in Fig. 2 and were used for the outcome analysis in Fig. S3B.

Univariable and multivariable analysis of the BCL9/9L-KO signature with regard to patient outcome. Top: univariable and multivariable analysis of DFS and available pathological and molecular markers in GSE39528 patients. Bottom: multivariable analysis of DFS and OS in PETACC3 patients.

Components of GSEA in Fig. 3. Origin and composition of all individual gene sets that were subjected to GSEA in Fig. 3 (Dalerba et al., 2011, Deka et al., 2010, Gotzmann et al., 2006, Groger et al., 2012, Kosinski et al., 2007, Merlos-Suarez et al., 2011, Munoz et al., 2012, Natoli et al., 2013, Powell et al., 2012, Sansom et al., 2004, Taube et al., 2010, Van der Flier et al., 2007, van der Flier, et al., 2009, Watanabe et al., 2014, Wong et al., 2012).

List of qRT-PCR primers.

Supplementary Material