Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii, a worldwide emerging nosocomial pathogen, acquires antimicrobial resistances in response to DNA-damaging agents, which increase the expression of multiple error-prone DNA polymerase components. Here we show that the aminocoumarin novobiocin, which inhibits the DNA damage response in Gram-positive bacteria, also inhibits the expression of error-prone DNA polymerases in this Gram-negative multidrug-resistant pathogen and, consequently, its potential acquisition of antimicrobial resistance through DNA damage-induced mutagenesis.

TEXT

Acinetobacter baumannii is a highly effective human colonizer in hospital settings worldwide. Its ability to acquire resistance to several extensively used antimicrobials has resulted in its emergence as a problematic nosocomial pathogen (1). As in other bacteria, A. baumannii achieves resistance against certain antimicrobials through single mutations in the corresponding target genes (i.e., point mutations in the rpoB gene can generate resistance to rifampin [2]). In previous works, we demonstrated that this bacterium contains multiple components of error-prone DNA polymerases, whose induction after DNA damage leads to the introduction of point mutations in the bacterial genome, including those conferring antibiotic resistance (3, 4).

Topoisomerase enzymes maintain the topological state of DNA and are critical regulators of protein translation and cell replication. Specifically, DNA gyrase (a type II topoisomerase) catalyzes the removal of the torsional stress that accumulates in bacterial chromosomes at sites preceding replication forks and transcriptional complexes by forming double-stranded breaks in the DNA (5). The formation of these double-stranded breaks and, therefore, of single-stranded DNA activates the bacterial SOS response, which results in mutagenic repair through the expression of mutagenic genes, especially those encoding error-prone DNA polymerases. This response guarantees DNA repair and cell survival but also results in some mutations that are able to confer antimicrobial resistance (2, 6). In Escherichia coli and other bacteria, the DNA damage response is regulated by the LexA repressor. However, A. baumannii lacks the LexA repressor, and the error-prone DNA polymerase (UmuDAb) carries out its functional role (3, 4). Thus, the induction of this DNA repair response in A. baumannii also results in the introduction of point mutations, including those conferring antibiotic resistance.

DNA gyrase inhibitors such as quinolones take advantage of the potential of topoisomerases to fragment the genome and thereby cause cell death. These drugs bind noncovalently at the enzyme-DNA interface in the cleavage-ligation active site to block ligation (5). Further, because quinolones also cause SOS induction, they ultimately promote antimicrobial resistance. Thus, one approach to combat the increasing prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant infections is to prevent SOS activation. Antimicrobials such as novobiocin interfere with the ATPase activity of DNA gyrase, such that chromosomal integrity is maintained, and the DNA repair/replication processes initiated by double-strand breaks are inhibited. Indeed, novobiocin was recently shown to be an effective inhibitor of the SOS response in Staphylococcus aureus (7). However, while the inhibition of DNA-damage-induced mutagenesis by novobiocin is well established in Gram-positive bacteria, whether this aminocoumarin also inhibits the mutagenic repair system of Gram-negative pathogens such as A. baumannii has yet to be determined. Therefore, in this study, we examined the effects of novobiocin on this microorganism and, specifically, on the expression of genes encoding error-prone DNA polymerases and on DNA-damage-induced mutagenesis.

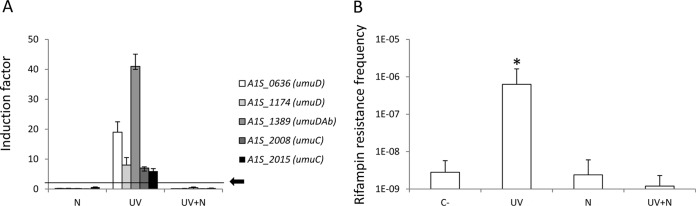

In this work, A. baumannii strain ATCC 17978 was used as the reference strain. The MICs of this strain for the antimicrobials used (ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, and novobiocin) were 0.25, 6, and 10 mg/liter, respectively, and were determined by broth microdilution. However, in all cases, we used the maximal antimicrobial concentration that produced no more than a 50% reduction in A. baumannii viability after 2 h of treatment (MC2h): 0.0625 mg/liter ciprofloxacin and 1.5 mg/liter tetracycline and novobiocin (8). UV treatments were performed as previously described (4). After irradiation of the samples (except the negative controls), the cultures were centrifuged, and the cells in the pellets were resuspended in 20 ml of LB broth with or without the MC2h of novobiocin and were incubated for 2 h in the dark to prevent photoreactivation of pyrimidine dimers. Ten milliliters of each culture was used for RNA extraction in order to determine the expression of genes belonging to the UmuDAb regulon of A. baumannii as previously described (3, 8). The relative mRNA concentrations of the studied genes were determined according to a standard curve generated by amplifying an internal fragment of the rpoB gene, which is not induced with any of the treatments used in this study (3, 9). The remaining 10 ml was washed twice and centrifuged again. The cells in the pellets were resuspended with fresh LB broth and were incubated for 24 h, after which the frequency of mutagenesis was evaluated as previously described (8). The results obtained showed that, after UV irradiation, all of the studied genes encoding components of the error-prone DNA polymerase V of A. baumannii were induced (Fig. 1A), as similarly reported by Norton et al. (2). However, in UV-irradiated and nonirradiated cultures, the expression of these genes was lower in those treated with novobiocin (Fig. 1A). In contrast, none of the treatments had any effect on the expression of the negative-control gene dinB (data not shown), which is not inducible after DNA damage in A. baumannii (2). Expression of the genes encoding the DNA polymerase V components correlated clearly with the frequency of the occurrence of rifampin resistance mutants (Fig. 1B). Thus, the frequency of mutagenesis was higher only in the UV-irradiated cultures, whereas in those treated with novobiocin, whether UV-irradiated or not, there was no significant difference compared to the negative control (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

(A) Expression of genes encoding components of error-prone DNA polymerase V in cultures of A. baumannii strain ATCC 17978 treated with novobiocin (N), UV irradiation (UV), or novobiocin after UV irradiation (UV+N) compared to expression in nontreated cultures (negative controls). Error bars represent the standard deviations of the means from at least two independent experiments, each carried out in duplicate. A value of ≥2 (black arrow) was considered to indicate induction. (B) Frequency of the occurrence of rifampin resistance mutants in A. baumannii strain ATCC 17978 cultures treated with UV irradiation, novobiocin, or novobiocin after UV irradiation. C−, negative control. Error bars represent the standard deviations of the means of the results of at least three independently tested cultures. The data were analyzed using a two-tailed, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Tukey test for post hoc multiple group comparisons. *, P < 0.01 compared to nontreated A. baumannii strain ATCC 17978 (C−).

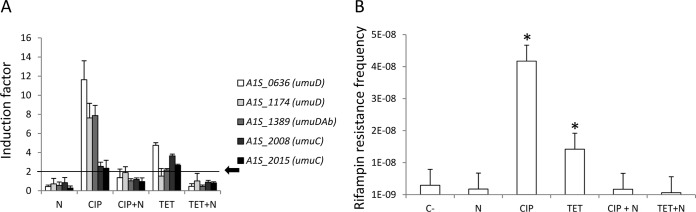

In recent work, we showed that ciprofloxacin and tetracycline induce SOS-mediated mutagenesis in A. baumannii (8). To determine whether novobiocin reduces the SOS response induced under these conditions, we analyzed its effect on the expression of umuDC genes and on the frequency of mutagenesis in A. baumannii treated with either ciprofloxacin or tetracycline. DNA damage mutagenesis was induced with the MC2h of either ciprofloxacin or tetracycline (8). The antimicrobial treatments, the gene expression determination, and the mutagenesis assays were performed as previously described (8) in the presence or absence of the corresponding antimicrobials with or without the MC2h of novobiocin for 2 h. Data obtained showed that after 2 h, in the presence or absence of novobiocin, gene expression (Fig. 2A) and mutagenesis (Fig. 2B) shared the same behavior when ciprofloxacin or tetracycline was used instead of UV irradiation as the DNA damage inducer.

FIG 2.

(A) Expression of genes encoding components of error-prone DNA polymerase V in cultures of A. baumannii strain ATCC 17978 treated with novobiocin (N), ciprofloxacin (CIP), ciprofloxacin plus novobiocin (CIP+N), tetracycline (TET), or tetracycline plus novobiocin (TET+N) compared to expression in nontreated cultures (negative controls). Error bars represent the standard deviations of the means from at least two independent experiments, each carried out in duplicate. A value of ≥2 (black arrow) was considered to indicate induction. (B) Frequency of the occurrence of rifampin resistance mutants in A. baumannii strain ATCC 17978 cultures treated with novobiocin, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin plus novobiocin, or tetracycline plus novobiocin. C−, negative control. Error bars represent the standard deviations of the means of the results of at least three independently tested cultures. The data were analyzed by a two-tailed, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Tukey test for post hoc multiple group comparisons. *, P < 0.01 compared to nontreated A. baumannii strain ATCC 17978 (C−).

In A. baumannii, DNA damage induces error-prone repair mechanisms, leading to mutations that confer antimicrobial resistance (2). Our results clearly show that, in the presence of novobiocin, expression of genes encoding mutagenic DNA polymerases is not induced, and, consequently, there is no increase in the mutagenesis frequency rates even in the presence of direct (UV irradiation and ciprofloxacin) or indirect (tetracycline) mediated DNA damage inducers. The recognition and removal of DNA damage may require unwinding the DNA by DNA gyrase, which is the target of novobiocin. Therefore, a possible mechanism underlying the observed effects due to novobiocin activity may be a reduction in the generation of single-strand DNA regions and in the number of DNA strand breaks made during the excision repair process, of which DNA gyrase (the novobiocin target) is an essential component (10). In conclusion, our data show that aminocoumarins such as novobiocin may reduce the risk of resistance development through error-prone DNA polymerase induction, thereby offering new perspectives in anti-infective therapy not only against Gram-positive but also against Gram-negative pathogens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the efforts of Joan Ruiz (UAB) and Susana Escribano (UAB) for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Pau Obregón (undergraduate UAB student) for his helpful support.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was also funded by Departament d’Innovació, Universitats i Empresa, Generalitat de Catalunya (DIUE), under grant number 2014SGR572.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pérez F, Hujer AM, Hujer KM, Decker BK, Rather PN, Bonomo RA. 2007. Global challenge of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:3471–3484. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01464-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norton MD, Spilkia AJ, Godoy VG. 2013. Antibiotic resistance acquired through a DNA damage-inducible response in Acinetobacter baumannii. J Bacteriol 195:1335–1345. doi: 10.1128/JB.02176-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aranda J, Poza M, Shingu-Vázquez M, Cortés P, Boyce JD, Adler B, Barbé J, Bou G. 2013. Identification of a DNA-damage-inducible regulon in Acinetobacter baumannii. J Bacteriol 195:5577–5582. doi: 10.1128/JB.00853-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aranda J, López M, Leiva E, Magán A, Adler B, Bou G, Barbé J. 2014. Role of Acinetobacter baumannii UmuD homologs in antibiotic resistance acquired through DNA damage-induced mutagenesis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:1771–1773. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02346-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aldred KJ, Kerns RJ, Osheroff N. 2014. Mechanism of quinolone action and resistance. Biochemistry 53:1565–1574. doi: 10.1021/bi5000564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Little JW, Mount DW. 1982. The SOS regulatory system of Escherichia coli. Cell 29:11–22. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schröder W, Goerke C, Wolz C. 2013. Opposing effects of aminocoumarins and fluoroquinolones on the SOS response and adaptability in Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:529–538. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jara LM, Cortés P, Bou G, Barbé J, Aranda J. 2015. Differential roles of antimicrobials in the acquisition of drug resistance through activation of the SOS response in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:4318–4320. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04918-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courcelle J, Khodursky A, Peter B, Brown PO, Hanawalt PC. 2001. Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics 158:41–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins A, Johnson R. 1979. Novobiocin; an inhibitor of the repair of UV-induced but not X-ray-induced damage in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 7:1311–1320. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.5.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]