Abstract

Here we describe the development and validation of an intracellular high-throughput screening assay for finding new antituberculosis compounds active in human macrophages. The assay consists of a luciferase-based primary identification assay, followed by a green fluorescent protein-based secondary profiling assay. Standard tuberculosis drugs and 158 previously recognized active antimycobacterial compounds were used to evaluate assay robustness. Data show that the assay developed is a short and valuable tool for the discovery of new antimycobacterial compounds.

TEXT

Tuberculosis (TB) caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis affects 9.0 million people annually, with 1.5 million deaths in 2013 (1). Standard TB treatment involves a regimen of four antibiotics taken daily for 6 to 9 months. However, the long treatment duration, toxicity, and interaction with antiretrovirals lead to poor patient compliance and treatment failure. Novel TB drug regimens are therefore urgently needed to treat both standard and drug-resistant forms of TB. Two new drugs, bedaquiline (2) and delamanid (3), were recently approved for the treatment of multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB, and other compounds are in the clinical development pipeline (4). Yet, the search for new TB drug candidates with different modes of action seeks to increase the chances of finding new drugs.

Screening of chemical libraries is the first crucial step in the antimicrobial discovery process. Potential antimycobacterial agents are identified by testing chemicals for the ability to inhibit M. tuberculosis growth under in vitro growth conditions in culture medium. However, in vitro screening results are often misleading, as the culture broth does not reflect the environment M. tuberculosis encounters in vivo during the natural course of the disease, neglecting important factors such as compound activation, membrane permeability, removal by efflux pump, and toxicity to mammalian cells (4). Furthermore, adaptive metabolic changes that M. tuberculosis undergoes within the host may affect compound activity (5). Ex vivo screening, in the macrophage, may represent physiological conditions that mimic disease and take into consideration the favorable contribution of host cells in the process of eradicating M. tuberculosis.

M. tuberculosis's intracellular lifestyle presents an attractive area for new drug discovery programs. A successful example is the intracellular high-content screening campaign that led to the discovery of Q203 (6). Image-based high-content screening technologies are being adopted more frequently to evaluate the activities of compounds against M. tuberculosis by using various cell types (7–9) or the granuloma infection model (10).

High-content screening against M. tuberculosis is a robust and informative assay; however, it is still lacking in terms of speed and simplicity since the endpoint assay requires multiple steps for staining, image acquisition, and cumbersome data analysis. In addition, most of the intracellular compound screening done so far was performed inside epithelial cells (11) or murine macrophages (7–9), which are not natural hosts of M. tuberculosis. In this report, we describe a new, fast, and robust intracellular high-throughput screening (HTS) method well suited for extensive compound screening campaigns against intracellular M. tuberculosis. Using this assay, we demonstrate the successful identification of a set of highly active intracellular compounds from a previously identified set of in vitro-active anti-M. tuberculosis compounds.

Our new protocol was developed to identify compounds active against intracellular M. tuberculosis by using THP-1 human monocytes infected with M. tuberculosis strains expressing either a luciferase or a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene for primary identification and a secondary profiling assay, respectively (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Large-scale production of uniformly infected THP-1 cells was achieved by performing the differentiation-infection in a single step and in bulk by using roller bottles with up to 1 liter of total volume, which is significantly different from microplate intracellular assays (7–9) and represents a key strategy to improve assay robustness by decreasing well-to-well variation, as reflected by the excellent Z′ scores obtained (Table 1). Different infection times and multiplicities of infection (MOIs) were tested (see the supplemental material) for M. tuberculosis constitutively expressing either luciferase or GFP. The conditions that worked best were concomitant differentiation and infection for 4 h with 40 ng ml−1 of phorbol myristate acetate at an MOI of 1:1. Intracellular bacterial loads were quantified to check the potency of the compounds by measuring either luciferase luminescence or GFP fluorescence. The optimal time point for measurement of growth inhibition in the primary assay was 5 days postinfection with the H37Rv strain expressing the luciferase gene. A shorter incubation time of only 4 days was required for the secondary assay with the Erdman strain expressing GFP, where intracellular mycobacterial growth was substantial and little apparent macrophage lysis was observed. These results are consistent with previous reports showing that the Erdman strain is more virulent than the H37Rv strain (12). Overall, the use of reporter genes to quantify bacterial loads along with concurrent differentiation and infection protocols and a 384-well plate format increased the assay throughput and shortened the screening time from weeks to only 5 or 6 days.

TABLE 1.

Intracellular MIC90 of standard TB drugs obtained by primary and secondary assay in comparison with in vitro MIC90a

| Drug | Intracellular MIC90 (μM) |

In vitro MIC90 (μM) in H37Rvb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary assayc | Secondary assayd | ||

| Rifampin | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Linezolid | 1.85 | 2.14 | 0.7 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.62 | 0.45 | 0.07 |

| Pyrazinamide | >50 | >50 | Inactive |

| Levofloxacin | 1.85 | 0.78 | 1.3 |

| Ethambutol | 16.67 | 14.63 | 4.6 |

| 4-Aminosalicylic acid | 50 | >50 | 6.5 |

| Isoniazid | 0.62 | 0.43 | 0.16 |

| Ofloxacin | 5.56 | 8.36 | 2.2 |

Data are the average results of two representative experiments.

Reference 21.

Assay robustness (Z′), 0.67, 0.64.

Assay robustness (Z′), 0.67, 0.76.

A dose-response assay was performed to determine the intracellular MICs of first- and second-line anti-TB drugs. MIC90 values were interpolated from dose-response curves obtained by testing the compounds with the luciferase and GFP assays and by plotting the percentage of growth inhibition against the log concentration of the standard compounds (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The intracellular MIC90 values obtained with both assays are summarized in Table 1. Overall, a good correlation between the MIC90 determined by the primary and secondary assays was observed. Rifampin was the most powerful intracellular compound in both assays, with MIC90 values of 0.02 to 0.06 μM, followed by isoniazid and moxifloxacin, both with MIC90 below 1 μM, which is consistent with previous reports (13, 14). Linezolid and levofloxacin demonstrated good intracellular activity, with a MIC90 of <2.5 μM, followed by ofloxacin and ethambutol with moderate activity (MIC90, <20), as reported elsewhere (13–15). Pyrazinamide did not exhibit any intracellular growth inhibition at any of the concentrations tested compared to a dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) negative control, consistent with previous data and in agreement with pyrazinamide's sterilizing activity against nonreplicating bacteria (16–19).

Statistical analysis was performed to assess assay quality, and Z′ values were calculated (20). The primary assay showed an average Z′ value of 0.65, and that of the secondary assay was similar at 0.71. This is a well-defined signal window for both assays, suggesting that the assays performed well and could be used for HTS to test a larger number of compounds.

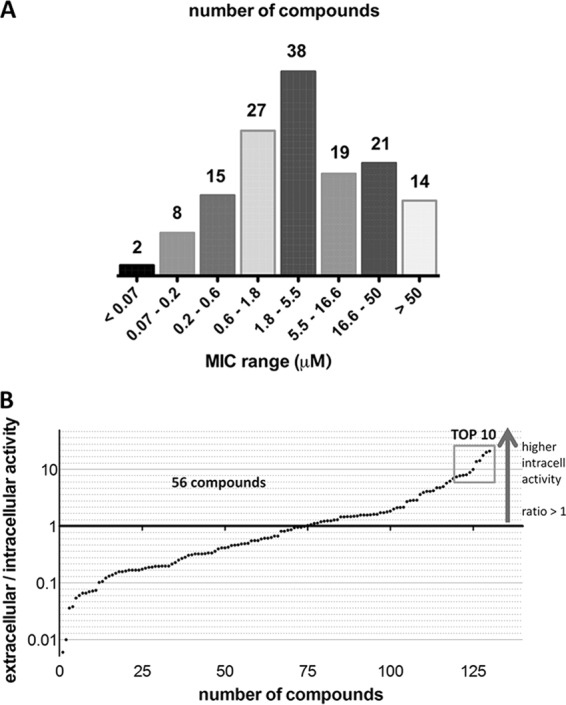

Next, the primary assay was used to screen a larger set of compounds shown to be highly active (MICs of ≤10 μM) against M. tuberculosis H37Rv under in vitro growth conditions (21). One hundred fifty-eight of these compounds were first tested in duplicate at a single concentration of 50 μM. Fourteen of the initial 158 compounds did not show intracellular activity and were discarded (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). One hundred forty-four compounds showed intracellular activity, with MICs below 50 μM, and were selected for dose-response studies.

Using the primary assay, 144 hits from the single-concentration assay were tested in a dose-response study. Figure 1A shows the distribution of the intracellular MIC90 of all of the compounds; for a summary of the individual MIC90, see Table S1 in the supplemental material. Of the 144 compounds tested, 90.3% were confirmed as active, with intracellular MIC90 of <50 μM. Of the 144 compounds tested in the dose-response study, 9.7% were found to have intracellular MIC90 above 50 μM. The previously reported extracellular MIC90 of each hit compound (21) was compared to the intracellular MIC90 obtained.

FIG 1.

Results of pilot screening of the set of compounds active in vitro. Panel A shows the distribution of the MIC ranges of the compounds tested (144 compounds distributed into eight MIC ranges). Panel B shows a comparison of compound potency in broth (extracellular MIC90) with activity in macrophages (intracellular MIC90). The extracellular/intracellular MIC90 ratios of all of the compounds were plotted. Compounds with ratios of >1 have higher activity in macrophages than in vitro, while compounds with ratios of <1 have higher in vitro activity. The 10 compounds with the highest intracellular versus extracellular activity are further described in Table 2.

Extracellular/intracellular MIC90 ratios are illustrated in Fig. 1B. Fifty-six compounds were more active in macrophages that in culture broth, showing extracellular/intracellular MIC90 ratios above 1. These compounds might be targeting pathways, either in the bacteria or in macrophages, that are essential during infection but not during in vitro growth (22–25). Although these compounds were identified initially as active under in vitro growth conditions, higher concentrations of them in macrophages, their intracellular conversion into active metabolites (26), or host cell interaction such as that of clofazimine (27, 28) could better explain our findings.

Seventy-four compounds had extracellular/intracellular MIC90 ratios below 1, indicating higher activity in vitro. This could be due to poor cell membrane permeability for the compound, activation of bacterial efflux pumps by macrophages (29), or even inactivation of the compound by host cell-derived metabolites (e.g., reactive oxygen or nitrogen species) or an acidic pH.

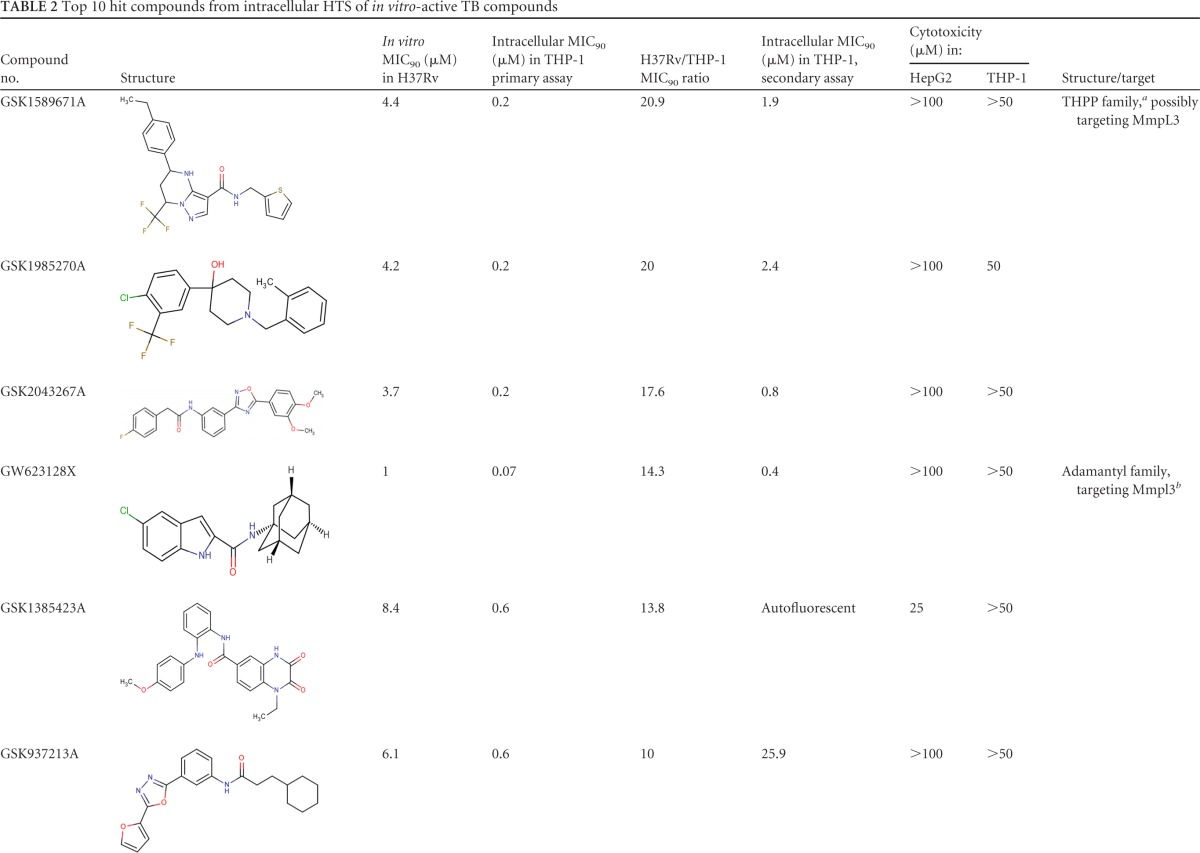

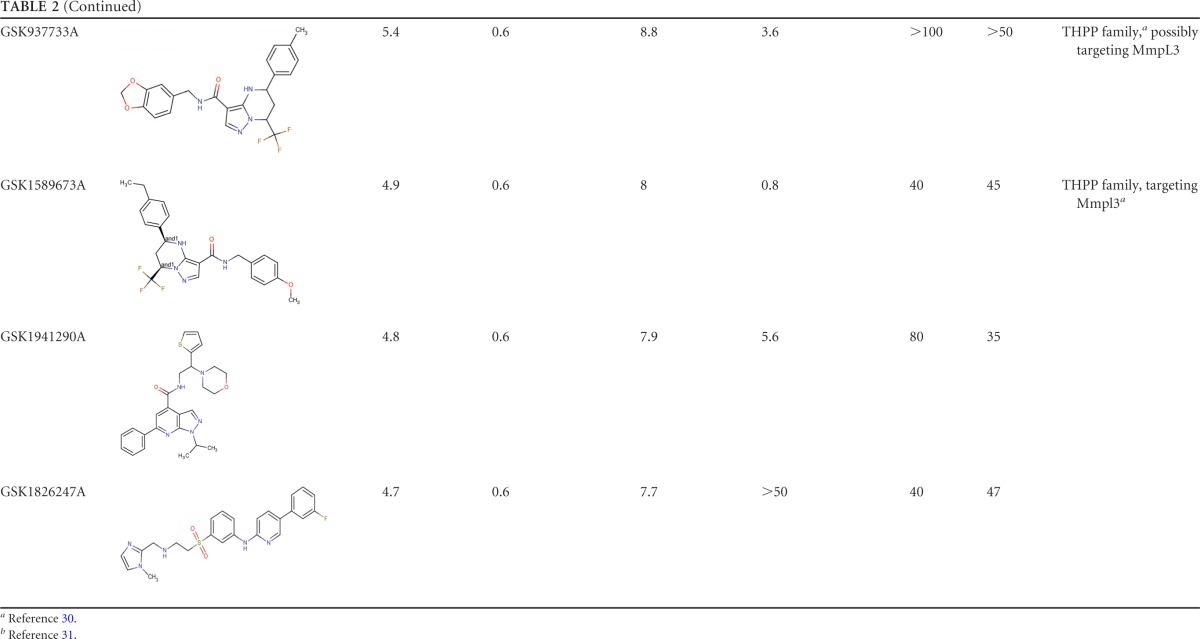

The 10 compounds with the highest extracellular/intracellular MIC90 ratios, as well as their chemical properties, are shown in Table 2. Among them are GSK1589671A (20.8-fold higher intracellular activity), GSK1985270A (20-fold higher intracellular activity), and GSK2043267A (17.6-fold higher intracellular activity).

TABLE 2.

Top 10 hit compounds from intracellular HTS of in vitro-active TB compounds

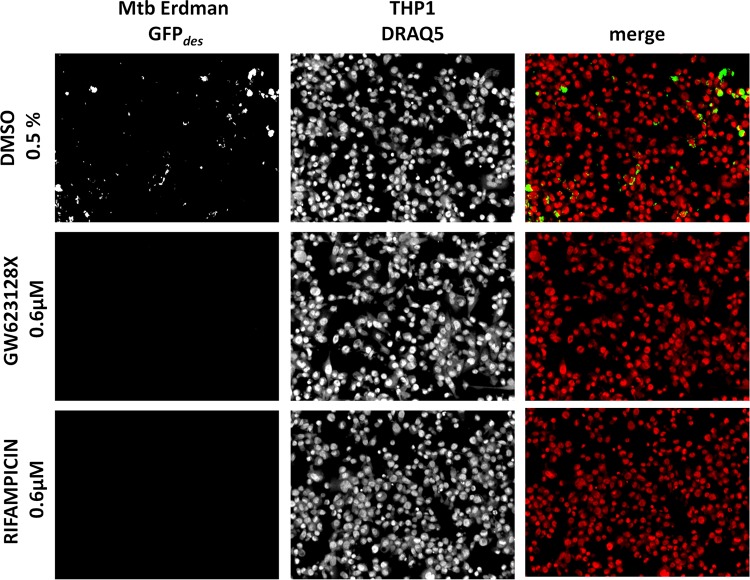

The intracellular activities of all 158 compounds at 50 μM were also tested by the secondary assay with the Opera High Content Screening System. The top 10 hit compounds from the primary screening were tested in a dose-response assay. On day 4, the percentage of infected cells reached an average of 34.3% in the DMSO control and 4.8% in the rifampin control (Fig. 2). Dose-dependent decreases in the bacterial loads and percentages of infection were obtained with all of the compounds tested (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The MIC90s obtained were consistent and in agreement with those obtained in the primary assay. However, high MIC90s of two compounds, GSK937213A and GSK1826247A, were obtained in the secondary assay. High lipophilicity (property forecast indexes of 9.8 and 8.4, respectively) and poor solubility could explain the difference between the data obtained in the primary and secondary assays with these two compounds. GSK1385423A appeared to be autofluorescent, interfering and thus giving false-negative results at the highest concentrations in the secondary assay (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

FIG 2.

Secondary intracellular assay of the top 10 compounds from the set of in vitro-active compounds. Pictures of M. tuberculosis (Mtb) Erdman-GFPdes-infected THP-1 cells at day 4 in the presence of DMSO at 0.5%, compound GW623128X at 0.6 μM, and rifampin at 0.6 μM are shown.

In conclusion, we have completed a pilot intracellular HTS assay with the differentiated human monocytic cell line THP-1. Robust assays were developed that enable the identification of compounds able to inhibit M. tuberculosis growth intracellularly. We believe that these assays will assist TB drug discovery by improving the ability to identify compounds that target mycobacterial and/or host cell proteins required for bacterial entry, replication, and survival in macrophages.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Neeraj Dahr for the kind gift of the M. tuberculosis Erdman GFP strain. We are grateful to Jeffrey Helm for help reviewing the manuscript. We also thank GSK Sample Management Technologies facilities for the preparation of compound-predispensed 384-well plates.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Tres Cantos Open Lab Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01920-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2014. Global tuberculosis report 2014. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diacon AH, Pym A, Grobusch M, Patientia R, Rustomjee R, Page-Shipp L, Pistorius C, Krause R, Bogoshi M, Churchyard G, Venter A, Allen J, Palomino JC, De Marez T, van Heeswijk RP, Lounis N, Meyvisch P, Verbeeck J, Parys W, de Beule K, Andries K, McNeeley DF. 2009. The diarylquinoline TMC207 for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 360:2397–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gler MT, Skripconoka V, Sanchez-Garavito E, Xiao H, Cabrera-Rivero JL, Vargas-Vasquez DE, Gao M, Awad M, Park SK, Shim TS, Suh GY, Danilovits M, Ogata H, Kurve A, Chang J, Suzuki K, Tupasi T, Koh WJ, Seaworth B, Geiter LJ, Wells CD. 2012. Delamanid for multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 366:2151–2160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mdluli K, Kaneko T, Upton A. 2015. The tuberculosis drug discovery and development pipeline and emerging drug targets. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 5:a021154. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galagan JE, Minch K, Peterson M, Lyubetskaya A, Azizi E, Sweet L, Gomes A, Rustad T, Dolganov G, Glotova I, Abeel T, Mahwinney C, Kennedy AD, Allard R, Brabant W, Krueger A, Jaini S, Honda B, Yu WH, Hickey MJ, Zucker J, Garay C, Weiner B, Sisk P, Stolte C, Winkler JK , Van de Peer Y, Iazzetti P, Camacho D, Dreyfuss J, Liu Y, Dorhoi A, Mollenkopf HJ, Drogaris P, Lamontagne J, Zhou Y, Piquenot J, Park ST, Raman S, Kaufmann SH, Mohney RP, Chelsky D, Moody DB, Sherman DR, Schoolnik GK. 2013. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis regulatory network and hypoxia. Nature 499:178–183. doi: 10.1038/nature12337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pethe K, Bifani P, Jang J, Kang S, Park S, Ahn S, Jiricek J, Jung J, Jeon HK, Cechetto J, Christophe T, Lee H, Kempf M, Jackson M, Lenaerts AJ, Pham H, Jones V, Seo MJ, Kim YM, Seo M, Seo JJ, Park D, Ko Y, Choi I, Kim R, Kim SY, Lim S, Yim SA, Nam J, Kang H, Kwon H, Oh CT, Cho Y, Jang Y, Kim J, Chua A, Tan BH, Nanjundappa MB, Rao SP, Barnes WS, Wintjens R, Walker JR, Alonso S, Lee S, Kim J, Oh S, Oh T, Nehrbass U, Han SJ, No Z, Lee J, Brodin P, Cho SN, Nam K, Kim J. 2013. Discovery of Q203, a potent clinical candidate for the treatment of tuberculosis. Nat Med 19:1157–1160. doi: 10.1038/nm.3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Queval CJ, Song OR, Delorme V, Iantomasi R, Veyron-Churlet R, Deboosere N, Landry V, Baulard A, Brodin P. 2014. A microscopic phenotypic assay for the quantification of intracellular mycobacteria adapted for high-throughput/high-content screening. J Vis Exp 83:e51114. doi: 10.3791/51114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanley SA, Barczak AK, Silvis MR, Luo SS, Sogi K, Vokes M, Bray MA, Carpenter AE, Moore CB, Siddiqi N, Rubin EJ, Hung DT. 2014. Identification of host-targeted small molecules that restrict intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth. PLoS Pathog 10:e1003946. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.VanderVen BC, Fahey RJ, Lee W, Liu Y, Abramovitch RB, Memmott C, Crowe AM, Eltis LD, Perola E, Deininger DD, Wang T, Locher CP, Russell DG. 2015. Novel inhibitors of cholesterol degradation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveal how the bacterium's metabolism is constrained by the intracellular environment. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004679. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva-Miranda M, Ekaza E, Breiman A, Asehnoune K, Barros-Aguirre D, Pethe K, Ewann F, Brodin P, Ballell-Pages L, Altare F. 2015. High-content screening technology combined with a human granuloma model as a new approach to evaluate the activities of drugs against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:693–697. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03705-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rybniker J, Chen JM, Sala C, Hartkoorn RC, Vocat A, Benjak A, Boy-Rottger S, Zhang M, Szekely R, Greff Z, Orfi L, Szabadkai I, Pato J, Keri G, Cole ST. 2014. Anticytolytic screen identifies inhibitors of mycobacterial virulence protein secretion. Cell Host Microbe 16:538–548. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.North RJ, Izzo AA. 1993. Mycobacterial virulence. Virulent strains of Mycobacteriatuberculosis have faster in vivo doubling times and are better equipped to resist growth-inhibiting functions of macrophages in the presence and absence of specific immunity. J Exp Med 177:1723–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chanwong S, Maneekarn N, Makonkawkeyoon L, Makonkawkeyoon S. 2007. Intracellular growth and drug susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 87:130–133. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartkoorn RC, Chandler B, Owen A, Ward SA, Bertel SS, Back DJ, Khoo SH. 2007. Differential drug susceptibility of intracellular and extracellular tuberculosis, and the impact of P-glycoprotein. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 87:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rey-Jurado E, Tudo G, Soy D, Gonzalez-Martin J. 2013. Activity and interactions of levofloxacin, linezolid, ethambutol and amikacin in three-drug combinations against Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in a human macrophage model. Int J Antimicrob Agents 42:524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Scorpio A, Nikaido H, Sun Z. 1999. Role of acid pH and deficient efflux of pyrazinoic acid in unique susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to pyrazinamide. J Bacteriol 181:2044–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi W, Zhang X, Jiang X, Yuan H, Lee J S, Barry CE III, Wang H, Zhang W, Zhang Y. 2011. Pyrazinamide inhibits trans-translation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 333:1630–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.1208813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grosset J, Almeida D, Converse PJ, Tyagi S, Li SY, Ammerman NC, Pym AS, Wallengren K, Hafner R, Lalloo U, Swindells S, Bishai WR. 2012. Modeling early bactericidal activity in murine tuberculosis provides insights into the activity of isoniazid and pyrazinamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:15001–15005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203636109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heifets L, Higgins M, Simon B. 2000. Pyrazinamide is not active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis residing in cultured human monocyte-derived macrophages. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 4:491–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. 1999. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen 4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballell L, Bates RH, Young RJ, Alvarez-Gomez D, Alvarez-Ruiz E, Barroso V, Blanco D, Crespo B, Escribano J, Gonzalez R, Lozano S, Huss S, Santos-Villarejo A, Martin-Plaza JJ, Mendoza A, Rebollo-Lopez MJ, Remuiñán-Blanco M, Lavandera JL, Perez-Herran E, Gamo-Benito FJ, Garcia-Bustos JF, Barros D, Castro JP, Cammack N. 2013. Fueling open-source drug discovery: 177 small-molecule leads against tuberculosis. ChemMedChem 8:313–321. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffin JE, Gawronski JD, Dejesus MA, Ioerger TR, Akerley BJ, Sassetti CM. 2011. High-resolution phenotypic profiling defines genes essential for mycobacterial growth and cholesterol catabolism. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002251. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang YJ, Reddy MC, Ioerger TR, Rothchild AC, Dartois V, Schuster BM, Trauner A, Wallis D, Galaviz S, Huttenhower C, Sacchettini JC, Behar SM, Rubin EJ. 2013. Tryptophan biosynthesis protects mycobacteria from CD4 T-cell-mediated killing. Cell 155:1296–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehrt S, Rhee K, Schnappinger D. 2015. Mycobacterial genes essential for the pathogen's survival in the host. Immunol Rev 264:319–326. doi: 10.1111/imr.12256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss G, Schaible UE. 2015. Macrophage defense mechanisms against intracellular bacteria. Immunol Rev 264:182–203. doi: 10.1111/imr.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wickramasinghe SN. 1987. Evidence of drug metabolism by macrophages: possible role of macrophages in the pathogenesis of drug-induced tissue damage and in the activation of environmental procarcinogens. Clin Lab Haematol 9:271–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2257.1987.tb00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baik J, Rosania GR. 2011. Molecular imaging of intracellular drug-membrane aggregate formation. Mol Pharm 8:1742–1749. doi: 10.1021/mp200101b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baik J, Rosania GR. 2012. Macrophages sequester clofazimine in an intracellular liquid crystal-like supramolecular organization. PLoS One 7:e47494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams KN, Takaki K, Connolly LE, Wiedenhoft H, Winglee K, Humbert O, Edelstein PH, Cosma CL, Ramakrishnan L. 2011. Drug tolerance in replicating mycobacteria mediated by a macrophage-induced efflux mechanism. Cell 145:39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Remuiñán MJ, Perez-Herran E, Rullas J, Alemparte C, Martinez-Hoyos M, Dow DJ, Afari J, Mehta N, Esquivias J, Jimenez E, Ortega-Muro F, Fraile-Gabaldon MT, Spivey VL, Loman NJ, Pallen MJ, Constantinidou C, Minick DJ, Cacho M, Rebollo-Lopez MJ, Gonzalez C, Sousa V, Angulo-Barturen I, Mendoza-Losana A, Barros D, Besra GS, Ballell L, Cammack N. 2013. Tetrahydropyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine-3-carboxamide and N-benzyl-6′,7′-dihydrospiro[piperidine-4,4′-thieno[3,2-c]pyran] analogues with bactericidal efficacy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis targeting MmpL3. PLoS One 8:e60933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grzegorzewicz AE, Pham H, Gundi VA, Scherman MS, North EJ, Hess T, Jones V, Gruppo V, Born SE, Kordulakova J, Chavadi SS, Morisseau C, Lenaerts AJ, Lee RE, McNeil MR, Jackson M. 2012. Inhibition of mycolic acid transport across the Mycobacterium tuberculosis plasma membrane. Nat Chem Biol 8:334–341. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.