Abstract

The reasons why aminoglycosides are bactericidal have not been not fully elucidated, and evidence indicates that the cidal effects are at least partly dependent on iron. We demonstrate that availability of iron markedly affects the susceptibility of the facultative intracellular bacterium Francisella tularensis strain SCHU S4 to the aminoglycoside gentamicin. Specifically, the intracellular depots of iron were inversely correlated to gentamicin susceptibility, whereas the extracellular iron concentrations were directly correlated to the susceptibility. Further proof of the intimate link between iron availability and antibiotic susceptibility were the findings that a ΔfslA mutant, which is defective for siderophore-dependent uptake of ferric iron, showed enhanced gentamicin susceptibility and that a ΔfeoB mutant, which is defective for uptake of ferrous iron, displayed complete growth arrest in the presence of gentamicin. Based on the aforementioned findings, it was hypothesized that gallium could potentiate the effect of gentamicin, since gallium is sequestered by iron uptake systems. The ferrozine assay demonstrated that the presence of gallium inhibited >70% of the iron uptake. Addition of gentamicin and/or gallium to infected bone marrow-derived macrophages showed that both 100 μM gallium and 10 μg/ml of gentamicin inhibited intracellular growth of SCHU S4 and that the combined treatment acted synergistically. Moreover, treatment of F. tularensis-infected mice with gentamicin and gallium showed an additive effect. Collectively, the data demonstrate that SCHU S4 is dependent on iron to minimize the effects of gentamicin and that gallium, by inhibiting the iron uptake, potentiates the bactericidal effect of gentamicin in vitro and in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Francisella tularensis is the etiological agent of the zoonotic disease tularemia. The bacterium has the capability to infect via many different routes, and the most common clinical manifestation is through vector-borne transmission, which leads to ulceroglandular tularemia (1). Another common route is through inhalation, which leads to respiratory tularemia, the most serious form of the disease (1). There are several subspecies of F. tularensis, and of these, the two clinically important forms are F. tularensis subsp. holarctica and F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (2). The latter is the more virulent form, and in the preantibiotic era, the respiratory form had a case-fatality rate of more than 50%. F. tularensis is a facultative intracellular bacterium capable of infecting many forms of cells; however, by far the most studied interaction is between F. tularensis and monocytic cells (3). As for other intracellular bacteria, the uptake of iron is critical for the successful replication, but in this regard F. tularensis is unusual since previous studies have identified only two iron uptake systems; the ferrous iron (feo) and the ferric siderophore (fsl) systems (4). The exact roles and contributions of these systems for efficient intramacrophage replication of the highly virulent strains are not clear, but efficient replication of the live vaccine strain of F. tularensis (LVS) in macrophages requires either one (5, 6).

The first-line treatments for tularemia are tetracyclines, quinolones, and aminoglycosides (7). The tetracycline of choice is doxycycline, which has good pharmacokinetic properties and low toxicity; however, due to its bacteriostatic nature, relapses are fairly common, and it is therefore not indicated for severe forms of tularemia. In contrast, the bactericidal nature of quinolones renders them promising therapeutic alternatives, although the clinical efficacy of ciprofloxacin has been validated only for infections caused by F. tularensis subsp. holarctica (7). Isolates of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis are susceptible to ciprofloxacin in vitro (8). Therefore, gentamicin is the drug of choice for treatment of more severe cases of tularemia.

Gentamicin, like all other aminoglycosides, has a bactericidal mode of action and acts through binding to the ribosome and various ribozymes, thereby leading to inhibition of protein synthesis (9). It is used to treat many types of bacterial infections, particularly those caused by Gram-negative organisms. The reasons why aminoglycosides are bactericidal have still not been fully elucidated, and recently the mechanisms of action have been much disputed. It has been suggested that the effects of aminoglycosides and other bactericidal antibiotics are mediated through the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and it was proposed that this, in turn, causes destabilization of iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters and generates highly toxic, bactericidal compounds through the Fenton reaction (10, 11). Several pieces of recent evidence argue against an involvement of ROS, however, since it has been demonstrated that killing of Escherichia coli by aminoglycosides is also effectuated under anaerobic conditions, and the aminoglycoside susceptibility is not enhanced for strains that lack ROS-detoxifying enzymes, although they are hypersusceptible to ROS (12, 13). An alternative hypothesis postulates that the role of Fe-S proteins in aminoglycoside susceptibility is due to the promotion of the uptake of the antibiotics (13).

Although the hypothesis that the primary killing mechanism effectuated by bactericidal antibiotics is dependent on ROS has been debated, there is still ample evidence that antibiotic-mediated killing indirectly may involve ROS. One such example is the finding that iron availability is important for the execution of antibiotic-mediated killing, since it was found that ferric iron promoted bacterial death via the Fenton reaction, iron chelation mitigated the antibiotic effects, and the susceptibility was closely correlated to the activity of the ferric reductase (14, 15). Besides the demonstrations that iron availability affects antibiotic susceptibility, there is also evidence that iron sequestration can potentiate antibiotic-mediated antibacterial effects in vitro. In support of this, several studies have demonstrated synergistic effects between aminoglycosides and iron chelation against multiple Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (16, 17). In view of the recent demonstration that Fe-S proteins promote uptake of aminoglycosides, the exact mechanisms behind the documented enhancement of antibiotic effects in vitro by iron chelation are unclear.

There is also direct chemical evidence that aminoglycosides form ROS in the presence of iron, since in the presence of polyunsaturated lipids, arachidonic acid is formed, which in turn forms a ternary complex with iron and gentamicin that leads to peroxidation (18). This has been postulated to be a basis for the well-known ototoxic effects of aminoglycosides but could also explain some of the bactericidal effects (19). Besides ototoxic effects, aminoglycosides also demonstrate nephrotoxic effects (19). These serious side effects also provide incentives to find means to potentiate the efficaciousness of aminoglycosides, which could allow the use of lower doses of gentamicin and thereby mitigation of the side effects. Previous examples of combination therapies to potentiate the efficacy of aminoglycosides include the use of gallium or the iron chelator deferoxamine in combination with gentamicin, which showed excellent effects on rabbit corneal infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (20). Similarly, liposome encapsulation of gallium and gentamicin showed efficacy superior to that of gentamicin alone for eradication of a P. aeruginosa biofilm (21). Thus, there is direct evidence that the efficacy of aminoglycosides can be potentiated through the use of iron chelation or by the addition of other metals, such as gallium, which presumably competitively displaces iron. Gallium is in itself a potential antibacterial compound with demonstrated efficacy against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (22–25). It is assumed that gallium is sequestered by iron uptake systems, since Ga(III) ligand chemistry shares similarity with that of ferric iron and it also potently binds siderophores used for iron uptake (20, 22, 26).

Gentamicin is a hydrophilic molecule and as such is considered to have limited capacity to penetrate into eukaryotic cells (27). In view of this, it would be logical if the antibiotic would show limited efficacy against intracellular organisms; however, it is among the recommended therapies against various facultative intracellular organisms, e.g., F. tularensis (7). Considering the limited intracellular concentrations of gentamicin and the predominant intracellular localization of F. tularensis, it is likely that the ability of gentamicin to eradicate F. tularensis could be enhanced. In view of the previous demonstration that gallium alone showed efficaciousness in an intranasal challenge model with Francisella novicida (24) in conjunction with the many publications that demonstrate critical roles of iron in the intracellular replication and virulence of F. tularensis (4, 5, 24, 28–32), we anticipated that a better understanding of how the requirement for iron affects antibiotic susceptibility of the bacterium would provide important clues to improved treatment regimens, and we hypothesized that gallium could potentiate the effect of gentamicin. We here demonstrate that gallium effectively inhibits the replication of F. tularensis in broth and during intracellular infection as well as in vivo, and these effects were partly synergistic with gentamicin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

F. tularensis LVS was originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. (ATCC 29684). The F. tularensis subspecies tularensis strain SCHU S4 was obtained from the Francisella Strain Collection (FSC), Swedish Defense Research Agency, Umeå. The construction of the ΔfslA and ΔfupA deletion mutants has been described elsewhere (29).

The ΔfeoB mutant was generated by allelic replacement essentially as described previously (33). Briefly, the fragments located upstream or downstream of the gene were amplified by PCR, and a second overlapping PCR using purified fragments 1 and 2 as templates was performed. After restriction enzyme digestion and purification, PCR fragments were cloned into the pDMK2 vector. The resulting plasmids were first introduced into E. coli S17-1 and then transferred to SCHU S4 by conjugation. Clones with plasmids integrated into the chromosome by a single recombination event were selected on plates containing kanamycin and polymyxin B. Integration was verified by PCR. Clones with integrations were then subjected to sucrose selection. This procedure selected for a second crossover event in which the integrated plasmid, carrying sacB, was excised from the chromosome. Kanamycin-sensitive, sucrose-resistant clones were examined by PCR, confirming the deletion of the genes. All primer sequences and detailed descriptions of the construction of the plasmids used to generate mutants are available upon request. All bacteriological work involving F. tularensis SCHU S4 was carried out in a biosafety level 3 facility certified by the Swedish Work Environment Authority.

Preparation of growth media.

Chamberlain's defined medium (CDM) was produced as described previously (2). This medium contains 2.0 μg/ml FeSO4. Deferoxamine (DFO) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to prepare agar plates devoid of free iron in the medium, and these were designated DFO plates. These plates were composed of 1 part 4% GC II agar base (BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD), 1 part CDM without FeSO4, and 25 μg/ml DFO. F. tularensis strains grown on agar plates with DFO have an iron content of less than 0.2 nmol/unit of optical density at 600 nm (OD) (29). Strains grown on DFO plates were denoted iron depleted.

MC plates were composed of 1% (wt/vol) hemoglobin (Oxoid LTD, Hampshire, England), 3.6% (wt/vol) GC agar base (BD Diagnostic Systems), and 1% (vol/vol) IsoVitaleX (BD Diagnostic Systems). F. tularensis subspecies tularensis strains cultivated on these plates have an iron content of about 7 nmol Fe/OD unit (29). Strains grown on MC plates were denoted iron replete.

Growth in CDM.

F. tularensis strains cultivated on MC plates or DFO plates were suspended in CDM to an OD of 0.1. Gentamicin (Sigma) and gallium-citrate (a gift from Madeleine Ramstedt, Department of Chemistry, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden) were supplied alone or in combination to the cultures as indicated for each experiment. In some experiments, CDM was supplemented with 10 μg/ml FeSO4 to reach a final concentration of 12 μg/ml FeSO4. The tubes were incubated at 37°C with agitation at 200 rpm, and the OD was measured at the indicated time points.

Etest.

Iron-depleted bacteria (100 μl) were seeded at a density of 3 × 107 CFU/ml on CDM agar plates containing 2, 6, or 24 μg/ml of FeSO4. An Etest strip with gentamicin (bioMérieux Nordic, Askim, Sweden) was placed on the agar. The plate was incubated for 3 days at 37°C in 5% CO2, and then the MIC was determined.

Ferrozine assay.

A ferrozine-based method was used to measure the total amount of iron in the bacterial samples, as previously described (30). Bacteria were cultivated in CDM and collected by centrifugation for 3 min at 13,000 rpm. The bacteria were thereafter washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by centrifugation for 5 min at 13,000 rpm, and the resulting bacterial pellet was lysed with 100 µl of 50 mM NaOH. The solution was mixed thoroughly to ensure complete lysis of the bacteria. One hundred microliters of 10 mM HCl was added to the lysate. To release protein-bound iron, the samples were treated with 100 μl of a freshly prepared solution of 0.7 M HCl and 2.25% (wt/vol) KMnO4 in H2O and incubated for 2 h at 60°C. All chemicals used were from Sigma-Aldrich. Thereafter, the samples were mixed with 100 μl of iron detection reagent composed of 6.5 mM ferrozine, 6.5 mM neocuproine, 2.5 M ammonium acetate, and 1.0 M ascorbic acid dissolved in water. The samples were incubated for 30 min, and insoluble particles were removed by centrifugation. Two hundred microliters of the supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate and the A562 determined in a microplate reader (Paradigm; Beckman Coulter, Bromma, Sweden). The iron content of the sample was calculated by comparing its absorbance to that of a range of samples with FeCl3 concentrations in the range of 0 to 40 μM that had been prepared identically to the test samples. The detection limit of the assay was 1 μM Fe.

Infection of BMDM.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) were obtained by flushing bone marrow cells from the femurs and tibias of C57BL/6 mice. These cells were cultured for 7 days in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 20% conditioned media (CM) from L929 cells (ATCC CCL-1) overexpressing macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF). CM was replaced every 2 to 3 days. The day before infection, macrophages were seeded at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well in a 24-well tissue culture plate in DMEM (GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (GIBCO). Following overnight incubation, cells were washed, reconstituted with fresh culture medium, and allowed to recover for at least 30 min prior to infection. A multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 30 was used, and phagocytosis of the bacteria was allowed to proceed for 90 min. Thereafter, the monolayer was washed three times and fresh medium added. The time point after the washing was defined as 0 h. For the remainder of the experiment, 10 μg/ml of gentamicin and/or 100 μM gallium was added to some of the wells. At 0 and 17 h, the macrophage monolayers were washed three times with DMEM and thereafter lysed with 200 μl of 0.1% deoxycholate, and the number of intracellular bacteria was determined by plating 10-fold serial dilutions of the lysates in PBS. The assay was performed in triplicates and repeated three times.

Mouse infection.

To measure the bacterial burden in spleen and liver, C57BL/6 female mice (n = 6 and n = 4) were infected subcutaneously with approximately 2 × 104 of F. tularensis LVS. Starting 24 h after inoculation, mice were given daily intraperitoneal injections of either PBS (300 μl/mouse), gentamicin (0.2 mg/mouse), gallium-citrate (0.6 mg/mouse), or both of the last two substances. In addition, mice receiving gallium were given one dose at 6 h after inoculation. Mice were examined twice daily for signs of severe infection, but no mice showed signs leading to euthanasia. The experiment was terminated after 4 days. The number of bacteria was determined by plating 10-fold serial dilutions of homogenized organs in PBS. All animal experiments were approved by the Local Ethical Committee on Laboratory Animals, Umeå, Sweden (A99-11 and A67-14).

Statistical analysis.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post hoc Bonferroni test was used to assess differences among treatments with regard to growth inhibition in CDM, BMDM, and mice, and if significant effects were found by this analysis, the Bliss independence test was applied to determine if there were synergistic effects (34).

RESULTS

Iron availability and gentamicin susceptibility of SCHU S4.

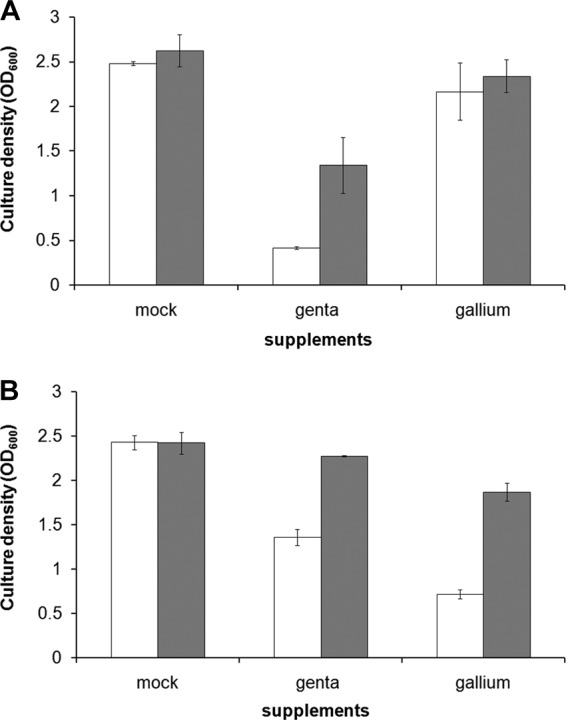

Based on the complex role of iron in antibiotic susceptibility, we tested whether the iron pool and the availability of iron in the medium influenced the susceptibility of SCHU S4 to gentamicin. The iron pool was depleted by culturing the bacteria on DFO plates overnight as previously described (30). Regardless of the size of the iron pool and the iron concentration in the medium, bacteria reached an OD of >2.0 after 24 h of cultivation (Fig. 1A and B). The MICs of gentamicin to inhibit growth of SCHU S4 in CDM were found to be approximately 1.0 and 1.25 μg/ml with 2 and 12 μg/ml of FeSO4, respectively, regardless of the size of the iron pool (data not shown).The concentration of 0.5 μg/ml of gentamicin was used in the subsequent experiments.

FIG 1.

Culture density of iron-replete SCHU S4 (A) or iron-depleted SCHU S4 (B) at 24 h in CDM supplemented with 2 μg/ml FeSO4 (white bars) or 12 μg/ml FeSO4 (gray bars), together with gentamicin (genta) (0.5 μg/ml) or gallium (100 μM). Similar results were observed in two additional experiments.

Gentamicin-induced growth inhibition was most pronounced when the bacteria had an intact iron pool and were grown in medium with 2 μg/ml FeSO4 (Fig. 1A). This growth inhibition was significantly decreased when iron-replete bacteria were grown in medium with 12 μg/ml FeSO4 (Fig. 1A) (P < 0.001), and a similar iron-dependent effect was observed for the iron-depleted bacteria (Fig. 1B) (P < 0.01). Thus, a high iron concentration in the medium decreased the gentamicin-induced growth inhibition regardless of the intracellular iron pool of the bacteria. Notably, regardless of the extracellular iron concentration, the effect of gentamicin was much more pronounced when bacteria were iron replete than when they were iron depleted (Fig. 1A and B) (P < 0.01).

Similarly to the bacteria grown in CDM, the susceptibility to gentamicin of SCHU S4 growing on agar was correlated to the iron concentration in the medium. By use of the Etest, it was observed that the MIC gradually increased and was 0.12, 0.19, and 0.25 μg/ml in the presence of 2.0, 6.0, and 24 μg/ml of FeSO4, respectively.

In summary, the initial intracellular and extracellular levels of iron showed opposite effects on the susceptibility of SCUH S4 to gentamicin, since the bacterium exhibited minimal susceptibility when the iron pool was depleted prior to the gentamicin exposure and the extracellular iron concentration was high during the exposure. As the former condition leads to upregulation of the iron uptake, the findings imply that a high uptake of iron is a means of SCHU S4 to minimize the effects of gentamicin. In view of this, we next intended to understand how the availability of iron affected the susceptibility to gentamicin.

FslA- and FeoB-dependent iron uptake and gentamicin susceptibility.

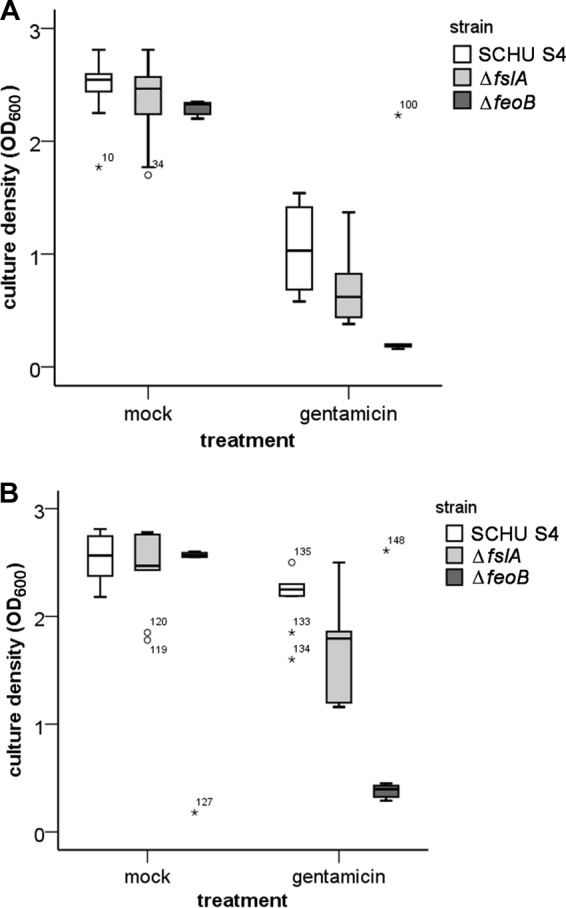

The role of iron and iron uptake in the susceptibility of SCHU S4 to gentamicin was evaluated by use of two mutants: a ΔfslA mutant, which is defective for siderophore-dependent uptake of ferric iron, and a ΔfeoB mutant, which is defective for uptake of ferrous iron. After cultivation in medium with 2 μg/ml of FeSO4 and 0.5 μg/ml of gentamicin, the iron-depleted ΔfslA mutant showed impaired growth (P < 0.05 versus SCHU S4) and the ΔfeoB mutant showed virtually no growth (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). Notably, the ΔfeoB mutant exhibited essentially no growth in the presence of 0.5 μg/ml of gentamicin even in medium with 12 μg/ml of FeSO4 (Fig. 2B). Growth of SCHU S4 and the ΔfslA mutant was significantly enhanced in the presence of 12 μg/ml versus 2.0 μg/ml of FeSO4 (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 2A and B), and the former grew most effectively (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

Gentamicin-induced growth inhibition of iron-depleted SCHU S4 and the ΔfslA and ΔfeoB mutants in CDM supplemented with 2.0 μg/ml FeSO4 (A) or 12 μg/ml FeSO4 (B). After 24 h of growth, the culture density was determined. The box plots represent values from three separate experiments, each with triplicate samples. The circles and asterisks represent mild and extreme outliers, respectively, as determined by SPSS. The numbers next to the circles and asterisks represent arbitrary designations for the individual values.

If the availability of iron is important for F. tularensis to resist gentamicin, then the efficacy of the iron uptake should play a role; therefore, this was assessed by measuring the iron pool of iron-depleted bacteria incubated in medium with 2 μg/ml of FeSO4 for 2 h. SCHU S4 and the ΔfslA mutant acquired 3.4 ± 0.4 and 3.3 ± 0.4 nmol Fe, respectively, per OD unit, whereas the ΔfeoB mutant acquired only 1.3 ± 0.3 nmol (P < 0.01).

In summary, the results imply that FeoB is crucial for SCHU S4 to resist the antibacterial effect of gentamicin and that it was the main molecular mechanism responsible for the uptake of iron from FeSO4. Based on this dependency on iron uptake and existing knowledge regarding the potential of gallium to utilize iron uptake mechanisms in F. tularensis (24), it was hypothesized that gallium could potentiate the effect of gentamicin.

Iron and gallium susceptibilities of SCHU S4.

Conditions under which gallium restricted growth of SCHU S4 were identified by exposing the bacterium to the substance under variable iron conditions. Growth of SCHU S4 bacteria with an intact iron pool was marginally affected by gallium (Fig. 1A). The gallium-induced growth inhibition was most pronounced when the bacteria had a depleted iron pool and were cultivated in medium with 2 μg/ml of FeSO4, whereas a concentration of 12 μg/ml of FeSO4 significantly reduced this growth inhibition (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1B).

Thus, addition of gallium led to marked growth inhibition when the iron pool had been depleted and bacteria were cultivated in medium with low iron concentration. The ferrozine assay was used to assess how the different conditions actually affected the uptake of iron. After 4 h, iron-depleted SCHU S4 incubated in medium supplemented with 2 or 12 μg/ml FeSO4 had accumulated 5.0 ± 0.2 and 95 ± 8 nmol Fe/OD unit, respectively, whereas the corresponding iron pools were 1.1 ± 0.4 and 12.9 ± 0.9 nmol/OD unit in the presence of 100 μM gallium.

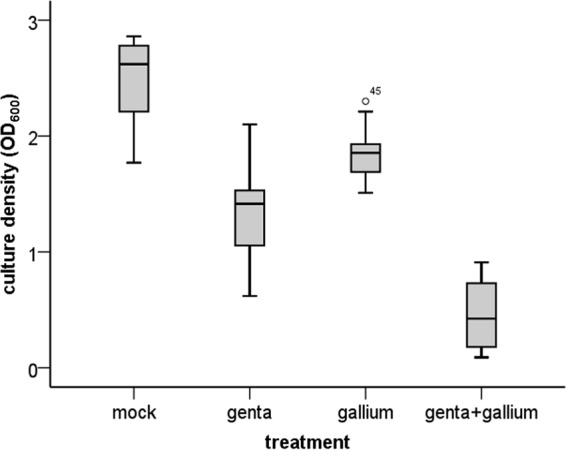

Synergism of gentamicin and gallium.

The finding that SCHU S4 was dependent on high iron uptake to resist the effects of gentamicin, together with the ability of gallium to inhibit iron uptake, led to the hypothesis that gallium could potentiate the antibacterial effect of gentamicin. Accordingly, when iron-depleted bacteria were grown in medium with either 0.5 μg/ml of gentamicin or 100 μM gallium, prominent growth inhibition was observed (P < 0.01 for gallium and P < 0.001 for gentamicin) (Fig. 3). When a combination of these substances was added to the medium, growth of SCHU S4 was inhibited to a significantly greater extent than with either substance alone (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3) and in a synergistic manner (Table 1). Not surprisingly, in view of the resistance of iron-replete bacteria to gallium, the synergistic effect of gentamicin and gallium was not apparent in cultures with iron-replete SCHU S4 (data not shown). In summary, gallium reduced the iron uptake of SCHU S4 and acted in synergy with gentamicin to inhibit bacterial growth. The findings lend further support to the hypothesis that limiting the iron uptake renders F. tularensis more susceptible to the antibacterial effects of gentamicin.

FIG 3.

Gentamicin- and gallium-induced growth inhibition of iron-depleted SCHU S4 in CDM. Cultures of SCHU S4 were supplemented with PBS (mock), gentamicin (genta) (0.5 μg/ml), gallium (100 μM), or both gentamicin and gallium. The culture densities were determined after 24 h. The box plots represent values from four experiments, each with triplicate samples. The circles and asterisks represent mild and extreme outliers, respectively, as determined by SPSS. The numbers next to the circles and asterisks represent arbitrary designations for the individual values.

TABLE 1.

Analysis of the combined effect of gentamicin and gallium in inhibition of growth of F. tularensis in different experimental models

| Experimental model | % inhibition with gentamicin and galliuma |

No. of experiments | Combined effect of gentamicin and gallium (P value)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictedb | Observed | |||

| CDM | 66 ± 7 | 88 ± 9 | 4 | Synergistic (<0.01) |

| BMDM, 6 h | 29 ± 19 | 53 ± 6 | 3 | Synergistic (<0.05) |

| BMDM, 17 h | 87 ± 5 | 98 ± 4 | 3 | Synergistic (<0.05) |

| Livers of mice | 99.7 ± 0 | 99.6 ± 1 | 2 | Additive (>0.05) |

Values are means ± standard deviations for observations derived from two to four separate experiments.

If two drugs work independently, the combined percent inhibition, Yab,P, can be predicted using the complete additivity of the probability theory, i.e., Yab,P = Ya + Yb − YaYb, where Ya is the observed percent inhibition of drug A and Yb is the observed percentage inhibition of drug B. This formula was used to calculate the predicted combined percent inhibition by gentamicin and gallium.

Synergistic indicates that in each separate experiment, the observed values were significantly different from the predicted value according to the one-sample t test. Additive indicates that in each separate experiment, the observed values were not significantly different from the predicted value according to the one-sample t test.

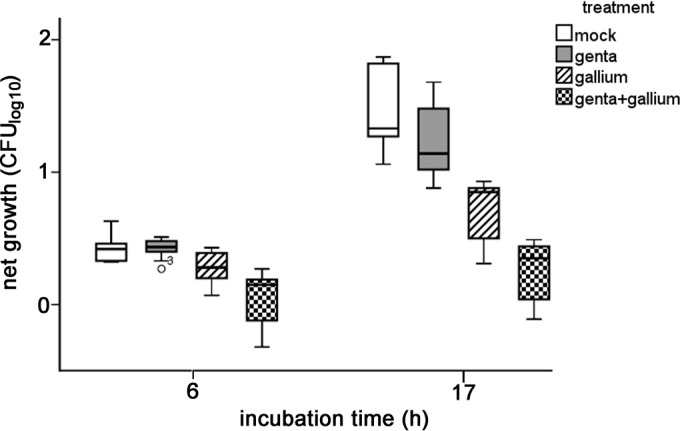

Effect of gentamicin and gallium on growth of SCHU S4 in BMDM.

In view of the observed synergistic effect of gentamicin and gallium under in vitro conditions, we asked if such a synergistic effect also occurred during intracellular infection. To this end, BMDM were infected with SCHU S4, and 10 μg/ml of gentamicin and/or 100 μM gallium was added to the cultures. The number of intracellular bacteria was analyzed at 6 and 17 h, time points where the cells showed no signs of cytotoxicity as determined by microscopy and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release.

At 6 h in untreated and gentamicin-treated cultures, SCHU S4 had grown less than 0.5. log10, and this growth was reduced, albeit not significantly, in the presence of gallium (Fig. 4). Nevertheless, a combination of gentamicin and gallium significantly inhibited the growth (P < 0.01 versus mock and gentamicin treatments), and the effect was synergistic (Fig. 4 and Table 1).

FIG 4.

Gentamicin- and gallium-induced growth inhibition of SCHU S4 in BMDM. Cell cultures infected with SCHU S4 were supplemented with PBS (mock), gentamicin (genta) (10 μg/ml), gallium (100 μM), or both gentamicin and gallium. After 0, 6, and 17 h of incubation, the number of intracellular bacteria was determined, and at 0 h it was on average 4.0 ± 0.1. The box plots represent values from three experiments, each with triplicate samples.

At 17 h in nontreated cultures, SCHU S4 had grown >1.0. log10, and this growth was reduced, albeit not significantly, in the presence of gentamicin, whereas the growth was reduced on average 0.7 log10 in the presence of gallium (P < 0.001 versus mock treatment and 0.01 versus gentamicin treatment) (Fig. 4). When a combination of gentamicin and gallium was added to the medium, growth of SCHU S4 was inhibited to a significantly greater extent than with either substance alone (P < 0.001 versus gentamicin treatment and 0.01 versus gallium treatment), and the effect was synergistic (Fig. 4 and Table 1).

In summary, gallium effectively inhibited the intracellular replication of F. tularensis in BMDM and showed a synergistic antibacterial effect with gentamicin.

Effect of gentamicin and gallium on growth of F. tularensis LVS in mice.

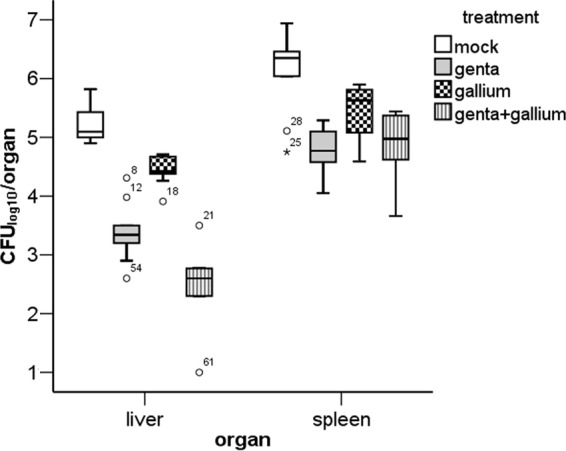

We also investigated whether the observed synergistic effects of gentamicin and gallium in vitro had any relevance in vivo. Mice were inoculated subcutaneously with a sublethal dose of 2 × 104 CFU of F. tularensis LVS and groups of mice treated with gallium (0.6 mg/mouse) and/or gentamicin (0.2 mg/mouse). Bacterial numbers in liver and spleen were determined after 4 days, a time point when maximal numbers of bacteria are present (35). Livers and spleens of control mice contained on average 5.2 and 6.1 log10, respectively. There was a significant inhibition of bacterial growth in both organs of mice treated with gentamicin (P < 0.001) and in livers and spleens of mice treated with gallium (P < 0.01 and P = 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 5). Notably, inhibition of growth was greater in livers of mice receiving both gentamicin and gallium than in those receiving either substance alone (P < 0.001), and this combined effect was additive (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Such a combined effect of gentamicin and gallium was not observed in spleen. Thus, the data demonstrated that both gallium and gentamicin had potent bactericidal effects in infected mice and that together they showed additive effects in liver.

FIG 5.

Gentamicin- and gallium-induced growth inhibition of LVS in livers and spleens of mice. Starting at 24 h after inoculation of bacteria, mice were given daily intraperitoneal injections of either PBS (300 μl/mouse), gentamicin (0.2 mg/mouse), gallium (0.6 mg/mouse), or both gentamicin and gallium. In addition, mice receiving gallium were given one dose at 6 h after inoculation. The bacterial numbers in spleens and livers were determined on day 4. The box plots represent bacterial numbers from two experiments (n = 10). The circles and asterisks represent mild and extreme outliers, respectively, as determined by SPSS. The numbers next to the circles and asterisks represent arbitrary designations for the individual values.

DISCUSSION

In view of the important role of gentamicin as a therapeutic agent for many infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria in general and tularemia in particular, we believed that a thorough understanding of how its mode of action against F. tularensis is affected by the availability of iron would be of relevance. Numerous publications have implied that iron contributes to the bactericidal effect of aminoglycosides; however, the findings have to some extent been contradictory. Some studies implied that ferric iron promoted bacterial death and iron chelation mitigated the antibiotic effect (14, 15), whereas other studies indicated that iron chelation acted in synergy with aminoglycosides against various Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (16, 17).

We observed that the susceptibility of SCHU S4 to gentamicin in vitro was very significantly affected by both the intracellular iron depots and the extracellular availability of iron. In fact, bacteria depleted of the iron pool and cultivated in medium with a high concentration of iron showed no significant growth inhibition, whereas the effect was very significant if bacteria were iron replete and grown in medium with a low concentration of iron. Since iron depletion will lead to increased iron uptake, we hypothesized that enhancement of iron uptake concomitantly with a surplus of extracellular iron will provide F. tularensis with optimal means to resist the bactericidal activity. Accordingly, the use of the ΔfslA and ΔfeoB mutants demonstrated that both uptake mechanisms were important for the bacteria to withstand the effects of gentamicin, since both mutants showed increased susceptibility, and this was particularly obvious for the ΔfeoB mutant since it showed virtually no growth. The findings emphasize the important role of iron in the susceptibility of F. tularensis to gentamicin and in particular the availability of ferrous iron. Also, our findings demonstrated that FeoB was by far the most important mediator of iron uptake from medium with FeSO4, since the uptake by the ΔfeoB mutant was some 70% lower than that by SCHU S4, whereas the ΔfslA-mediated uptake was similar to that by the wild-type strain.

FeoB was show to be critical for the ability of SCHU S4 to resist the antibacterial effect of gentamicin and also the main molecular mechanism responsible for the uptake of iron from FeSO4. These findings, together with the demonstration of the critical role of iron for bacteria to withstand the bactericidal effect of gentamicin, led to the hypothesis that the effect of gentamicin could be potentiated by gallium, since this metal utilizes iron uptake mechanisms and therefore competitively antagonizes the importance of an increased iron uptake. In addition, it has been shown that gallium per se executes an antibacterial effect against F. novicida (24). First, we observed that the antibacterial effects of gallium in vitro were most pronounced when the iron pool had been depleted and the bacteria were cultivated in medium with a low concentration of iron. In contrast, bacteria with an intact iron pool were only marginally affected by gallium. Thus, the results demonstrated that the effects of gallium were inversely correlated to availability of iron, indicating direct antagonism between the two metals as the mode of action. Since the in vitro findings based on the manipulation of the iron supply suggested that a surplus of iron and upregulated iron uptake both were important for the bacteria to minimize the effects of gentamicin, the collective evidence implied that gallium would counteract these effects and, therefore, possibly enhance the effect of gentamicin.

In accordance with our hypothesis, we found that gallium or gentamicin alone showed prominent inhibitory effects on iron-depleted F. tularensis and that the two compounds acted synergistically in vitro. Since the bacterium effectively replicates intracellularly, it was also of relevance to investigate how the antibacterial mechanisms were operative in infected cell cultures. To this end, gallium and/or gentamicin was added to F. tularensis-infected BMDM, and we observed that either inhibited the intracellular bacterial growth. Again, when both substances were added, they exhibited synergistic effects. When mice infected with a sublethal dose were treated with gentamicin and/or gallium, we observed a significant inhibition of bacterial growth in the organs of mice treated with either substance, and an additive effect of the two substances was found in liver. Although the reason for the more profound effect in liver is not known, it has been demonstrated that a considerable proportion of administered gallium is located in the liver and that the concentrations are higher in liver than in spleen (36). Possibly, the effects in vivo of the combined treatment could be enhanced by improved delivery systems. Also, in view of the intracellular nature of F. tularensis and the hydrophilic nature of gentamicin, the present investigation was of interest from a theoretical point of view, since it could be postulated that the effective intracellular uptake of gallium would potentiate the effects of gentamicin against intracellular bacteria.

Collectively, our findings identify a critical role of iron for the bacteria to withstand the effects of gentamicin, and the antagonistic effect seems to be correlated to the presence of high extracellular concentrations and depleted intracellular depots; presumably, the latter effect is related to upregulation of the iron uptake. Gallium was found to be an effective competitive antagonist of the iron uptake, and the combined synergistic effects of gallium and gentamicin also supported a scenario where the high uptake of iron was critical for the bacterium to withstand the gentamicin-mediated effects. In relation to previous data on the effects of iron chelation and the antibacterial effects of gentamicin, our findings support previously published studies that reported an additive or synergistic effect (16, 17).

Our study focused on the role of iron and did not investigate the role of ROS for the gentamicin-mediated killing. Several pieces of evidence argue, however, against a direct role of ROS. First, the effect of gentamicin was minimized in the presence of a high concentration of iron, an environment which will favor the Fenton reaction and thus should have enhanced the gentamicin-induced killing if the effect was ROS dependent. Second, the inhibitory effect of gentamicin was most prominent for the ΔfeoB mutant, which had a severely impaired iron uptake that should have minimized the Fenton reaction and the effect of ROS. In addition, in a previous study, we studied the ability of F. tularensis to survive in the presence of hydrogen peroxide and observed that strains of F. tularensis subspecies tularensis, e.g., SCHU S4, showed a much more restricted iron uptake and storage than other subspecies and that this correlated to better survival, indicating that minimizing the Fenton reaction was beneficial (30). These findings are in contrast to the present findings on the ability of the bacterium to withstand the effects of gentamicin and again argue against a role of the Fenton reaction in the latter case.

Altogether, this study demonstrates a promising strategy to potentiate antibiotic effects via manipulation of iron availability. This has been only rarely studied, and in view of the effect observed in vitro and in vivo in the present study, the strategy of combination therapies based on a traditional antibiotic and compounds that affect iron availability should be further evaluated, since they could be promising alternatives when the antibiotic regimens used show limited efficacy due to resistant or inaccessible bacteria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was performed in part at the Umeå Centre for Microbial Research.

We thank Madeleine Ramstedt and Olena Rzhepishevska, Department of Chemistry, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden for advice during the initial work.

Funding Statement

Support was also obtained from the Medical Faculty, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tärnvik A, Berglund L. 2003. Tularaemia. Eur Respir J 21:361–373. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00088903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjöstedt A. 2007. Tularemia: history, epidemiology, pathogen physiology, and clinical manifestations. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1105:1–29. doi: 10.1196/annals.1409.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elkins KL, Cowley SC, Bosio CM. 2007. Innate and adaptive immunity to Francisella. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1105:284–324. doi: 10.1196/annals.1409.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez NM, Ramakrishnan G. 2014. The reduced genome of the Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain (LVS) encodes two iron acquisition systems essential for optimal growth and virulence. PLoS One 9:e93558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramakrishnan G, Sen B, Johnson R. 2012. Paralogous outer membrane proteins mediate uptake of different forms of iron and synergistically govern virulence in Francisella tularensis subspecies tularensis. J Biol Chem 287:25191–25202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.371856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramakrishnan G, Sen B. 2014. The FupA/B protein uniquely facilitates transport of ferrous iron and siderophore-associated ferric iron across the outer membrane of Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain. Microbiology 160:446–457. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.072835-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tärnvik A, Chu MC. 2007. New approaches to diagnosis and therapy of tularemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1105:378–404. doi: 10.1196/annals.1409.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urich SK, Petersen JM. 2008. In vitro susceptibility of isolates of Francisella tularensis types A and B from North America. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:2276–2278. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01584-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mingeot-Leclercq MP, Glupczynski Y, Tulkens PM. 1999. Aminoglycosides: activity and resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 43:727–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalghatgi S, Spina CS, Costello JC, Liesa M, Morones-Ramirez JR, Slomovic S, Molina A, Shirihai OS, Collins JJ. 2013. Bactericidal antibiotics induce mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in mammalian cells. Sci Transl Med 5:192ra185. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. 2007. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell 130:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Imlay JA. 2013. Cell death from antibiotics without the involvement of reactive oxygen species. Science 339:1210–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.1232751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ezraty B, Vergnes A, Banzhaf M, Duverger Y, Huguenot A, Brochado AR, Su SY, Espinosa L, Loiseau L, Py B, Typas A, Barras F. 2013. Fe-S cluster biosynthesis controls uptake of aminoglycosides in a ROS-less death pathway. Science 340:1583–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1238328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foti JJ, Devadoss B, Winkler JA, Collins JJ, Walker GC. 2012. Oxidation of the guanine nucleotide pool underlies cell death by bactericidal antibiotics. Science 336:315–319. doi: 10.1126/science.1219192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeom J, Imlay JA, Park W. 2010. Iron homeostasis affects antibiotic-mediated cell death in Pseudomonas species. J Biol Chem 285:22689–22695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.127456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Asbeck BS, Marcelis JH, van Kats JH, Jaarsma EY, Verhoef J. 1983. Synergy between the iron chelator deferoxamine and the antimicrobial agents gentamicin, chloramphenicol, cefalothin, cefotiam and cefsulodin. Eur J Clin Microbiol 2:432–438. doi: 10.1007/BF02013900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartzen SH, Frimodt-Möller N, Thomsen VF. 1994. The antibacterial activity of a siderophore. 3. The activity of deferoxamine in vitro and its influence on the effect of antibiotics against Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis and coagulase-negative staphylococci. APMIS 102:219–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lesniak W, Pecoraro VL, Schacht J. 2005. Ternary complexes of gentamicin with iron and lipid catalyze formation of reactive oxygen species. Chem Res Toxicol 18:357–364. doi: 10.1021/tx0496946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forge A, Schacht J. 2000. Aminoglycoside antibiotics. Audiol Neurootol 5:3–22. doi: 10.1159/000013861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banin E, Lozinski A, Brady KM, Berenshtein E, Butterfield PW, Moshe M, Chevion M, Greenberg EP. 2008. The potential of desferrioxamine-gallium as an anti-Pseudomonas therapeutic agent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:16761–16766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808608105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halwani M, Yebio B, Suntres ZE, Alipour M, Azghani AO, Omri A. 2008. Co-encapsulation of gallium with gentamicin in liposomes enhances antimicrobial activity of gentamicin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother 62:1291–1297. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaneko Y, Thoendel M, Olakanmi O, Britigan BE, Singh PK. 2007. The transition metal gallium disrupts Pseudomonas aeruginosa iron metabolism and has antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity. J Clin Invest 117:877–888. doi: 10.1172/JCI30783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeLeon K, Balldin F, Watters C, Hamood A, Griswold J, Sreedharan S, Rumbaugh KP. 2009. Gallium maltolate treatment eradicates Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in thermally injured mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:1331–1337. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01330-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olakanmi O, Gunn JS, Su S, Soni S, Hassett DJ, Britigan BE. 2010. Gallium disrupts iron uptake by intracellular and extracellular Francisella strains and exhibits therapeutic efficacy in a murine pulmonary infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:244–253. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00655-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menon S, Wagner HN Jr, Tsan MF. 1978. Studies on gallium accumulation in inflammatory lesions. II. Uptake by Staphylococcus aureus: concise communication. J Nucl Med 19:44–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emery T. 1986. Exchange of iron by gallium in siderophores. Biochemistry 25:4629–4633. doi: 10.1021/bi00364a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mingeot-Leclercq MP, Piret J, Brasseur R, Tulkens PM. 1990. Effect of acidic phospholipids on the activity of lysosomal phospholipases and on their inhibition by aminoglycoside antibiotics. I. Biochemical analysis. Biochem Pharmacol 40:489–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fortier AH, Leiby DA, Narayanan RB, Asafoadjei E, Crawford RM, Nacy CA, Meltzer MS. 1995. Growth of Francisella tularensis LVS in macrophages: the acidic intracellular compartment provides essential iron required for growth. Infect Immun 63:1478–1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindgren H, Honn M, Golovlev I, Kadzhaev K, Conlan W, Sjöstedt A. 2009. The 58-kilodalton major virulence factor of Francisella tularensis is required for efficient utilization of iron. Infect Immun 77:4429–4436. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00702-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindgren H, Honn M, Salomonsson E, Kuoppa K, Forsberg A, Sjöstedt A. 2011. Iron content differs between Francisella tularensis subspecies tularensis and subspecies holarctica strains and correlates to their susceptibility to H(2)O(2)-induced killing. Infect Immun 79:1218–1224. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01116-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sen B, Meeker A, Ramakrishnan G. 2010. The fslE homolog, FTL_0439 (fupA/B), mediates siderophore-dependent iron uptake in Francisella tularensis LVS. Infect Immun 78:4276–4285. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00503-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas-Charles CA, Zheng HX, Palmer LE, Mena P, Thanassi DG, Furie MB. 2013. FeoB-mediated uptake of iron by Francisella tularensis. Infect Immun 81:2828–2837. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00170-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadzhaev K, Zingmark C, Golovliov I, Bolanowski M, Shen H, Conlan W, Sjöstedt A. 2009. Identification of genes contributing to the virulence of Francisella tularensis SCHU S4 in a mouse intradermal infection model. PLoS One 4:e5463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bliss C. 1956. The calculation of microbial assays. Bacteriol Rev 20:243–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conlan JW, Sjöstedt A, North RJ. 1994. CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell-dependent and -independent host defense mechanisms can operate to control and resolve primary and secondary Francisella tularensis LVS infection in mice. Infect Immun 62:5603–5607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collery P, Domingo JL, Keppler BK. 1996. Preclinical toxicology and tissue gallium distribution of a novel antitumour gallium compound: tris (8-quinolinolato) gallium (III). Anticancer Res 16:687–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]