Abstract

Currently, less than thirty cases of primary malignant melanoma of the lung have been reported in the literature. Thus, strict criteria for diagnosis have been published and include: malignant melanoma associated with bronchial epithelial changes; a solitary lung tumor; no prior history of skin, mucous membrane, intestinal or ocular melanoma; and absence of any other detectable tumor at the time of diagnosis. In this article we present a case of melanoma of the lung without evidence of extra-pulmonary disease.

Keywords: Lung, melanoma, primary, thoracic

Introduction

More than 90% of melanomas are cutaneous in origin1 and the majority of the non-cutaneous melanomas are localized in the lung. Primary lung melanoma (PLM) is a very rare disease with less than thirty cases reported in the literature and even fewer satisfying the published diagnostic criteria.2 Herein, we report a case of an 82-year-old man who underwent a right lung resection for a right lower lobe mass. The histopathological findings were consistent with an achromic melanoma. Further investigations failed to confirm, with certainty, an occult primary tumor. Clinical, radiological, and histopathological features are presented and diagnostic criteria are reviewed.

Case presentation

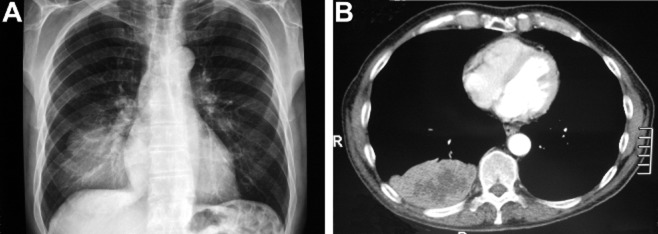

An 82-year-old male non-smoker with a three-year history of prostate adenocarcinoma, for which he had received hormonal treatment and radiotherapy, presented with a five-month history of upper gastrointestinal tract symptoms and weakness. The patient had no personal or family history of lung disease or skin tumors. He denied any history of pigmented or previously resected skin lesion; all other systems were reviewed and were negative. A chest radiography identified a right lower lobe mass centrally located (Fig 1A); computed tomography (CT) scans of the brain, chest, and superior abdomen did not reveal any metastatic lesions and confirmed the presence of a 9.5 × 5.5 × 9 cm pulmonary mass (Fig 1B). Prostatic specific antigen levels were normal.

Figure 1.

Preoperative chest X-ray (A) and computed tomography(CT) (B) scan showing the right lower lobe mass.

A transthoracic fine needle biopsy specimen of the mass revealed a poorly differentiated polymorphic carcinoma including medium-sized cells exhibiting large and hyperchromatic nuclei, as well as areas of large cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and some prominent nucleoli. The tumor stained strongly positive for vimentin and focally for S-100 protein. Epithelial markers (pancytokeratin, cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 20, epithelial membrane antigen [EMA]), keratin, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), P63, thyroid transcription factor (TTF)-1, CD45, neuroendocrine markers (synaptophysin, chromographin) and muscular markers (actin and desmin) were all negative.

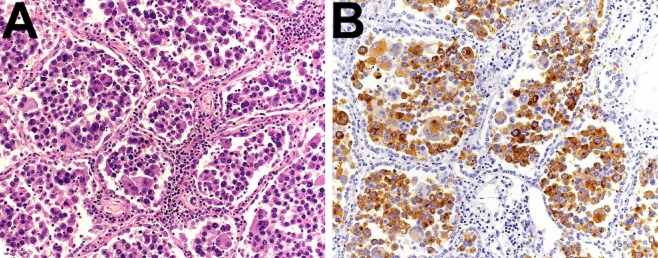

At preoperative work up, no other lesions were identified upon usual evaluation, which included chest, brain, and upper abdomen CT scans, as well as bone scintigraphy. The patient was, thus, considered a good surgical candidate and underwent total right lung resection without any major postoperative complications. Macroscopically there was no visceral pleura or lymph node involvement. The tumor measured 12 × 8.5 × 6.5 cm with areas of necrosis (Fig 2) and seemed to originate from the inferior lobar bronchus. Frozen-section analysis confirmed negative margins. The tumor consisted of focally multinucleated cells with marked anisokaryosis, markedly pleomorphic nuclei, and cytoplasmic intranuclear inclusions. Cytoplasm was dense and eosinophilic, without pigment. Interestingly, the alveolar spaces were stuffed with tumor cells (Fig 3). A thorough immunohistochemical analysis of the tumor was performed. Tumor cells were negative for epithelial markers (pancytokeratin, EMA, cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 20, CEA and p63), for neuroendocrine markers (synaptophysin and Chromogranin A), and for muscle markers (alpha-actin and desmin). They were positive for the melanoma markers S100 (Fig 3), human melanoma black (HMB)45 and Melan-A. Molecular analysis of the tumor showed absence of the EWS-ATF1 fusion-transcript, thus, excluding clear cell sarcoma (also known as malignant melanoma of soft parts). The morphology of the tumor as well as the immunophenotype was consistent with an achromic malignant melanoma.

Figure 2.

Right pneumonectomy specimen; the tumor can be identified as a white-colored mass of the lower lobe on the left of the picture, in contact with, but without macroscopic effraction of the visceral pleura.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry. (A) Tumor cells are discohesive, markedly pleomorphic, and fill almost completely the alveolar spaces of the lung parenchyma (hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining). (B) Tumor cells show a diffuse cytoplasmic and focal nuclear immunostaining with S100 (a melanocyte marker).

Given the final diagnosis, extensive postoperative evaluation was undertaken in order to detect a skin, mucous membrane, gastrointestinal tract or eye melanoma. This included physical examination, dermatoscopy, gastroscopy, colonoscopy, fundoscopic examination of the eyes, and a F-18 fluorodeoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) with CT. The latter did not identify any skin hypermetabolism, but showed increased uptake of multiple mediastinal lymph nodes (SUVbw max 3.7-5.4) and left adrenal gland (SUVbw max 4.8), consistent with metastases. Initially, no additional treatment was proposed taking into consideration the patient's age and lack of symptoms, after tumor resection. Three months later, the patient presented with right posterior chest-wall pain. A chest CT-scan showed a disseminated intercostal lesion infiltrating the ninth rib. Localized radiotherapy was initiated with a partial clinical response, but the patient finally passed away thirteen months after initial diagnosis. An autopsy was not performed.

Discussion

Diagnostic criteria for PLM include: junctional changes with “dropping off” or “nesting” of melanoma cells just beneath the bronchial epithelium; invasion of the bronchial epithelium by melanoma cells in an area where the bronchial epithelium is not ulcerated; and malignant melanoma associated with these epithelial changes.3 In order to further rule out metastatic pulmonary disease presenting as PLM, a solitary lung tumor, no prior history of a cutaneous mucous membrane or ocular melanoma and, finally, absence of any other detectable tumor at the time of diagnosis (proven subsequently by autopsy) are required.4

Less than thirty cases of PLM have been published since 1886 and many of these failed to meet the aforementioned criteria, as demonstrated by Ost et al.2 Furthermore, the possibility of an occult or antecedent primary skin or mucosal lesion cannot be excluded, especially if this lesion has spontaneously regressed.2 In our case, a postoperative FDG-PET scan showed increased left adrenal gland uptake, without enlargement, which could be consistent with metastatic disease. However, the possibility of a primary adrenal melanoma with solitary lung metastasis cannot safely be ruled out, even though primary adrenal melanoma is even rarer than PLM.5 Other unusual primary visceral sites have been reported, including the meninges,6 the esophagus,7,8 the oral-nasopharynx, anal canal, rectum, stomach, small bowel, gallbladder, and large bowel,9 the uterine cervix,10 the ovary11 and the kidney.12

Histological differential diagnosis of PLM includes carcinoma (which is negative for melanoma markers and positive for epithelial markers), neuroendocrine tumors (positive for neuroendocrine markers), and neurogenic sarcoma (positive for S100, but negative for HMB45 and Melan-A). PLM is thought to originate from junctional changes of bronchial epithelium (concomitant nevus-like lesion) according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors. In our case, however, the lobar bronchus from which the tumor seemed to originate was completely destroyed by the melanoma. The mechanism of PLM arousal is not fairly understood. Theories involve migration of melanocytes along the primordial tubular respiratory tract during fetal development,13 even though melanoblasts have not yet been demonstrated in the lungs. Another theory refers to a melanogenic metaplasia of respiratory epithelial cells into melanocytes.14 As mentioned before, metastasis of an indistinguishable or regressed skin or mucosal lesion should be taken into consideration as well.

Because of the rarity of the disease, treatment options are poorly delineated and are based on data deriving from two reviews with a total of twenty-seven patients,2,15 and from case reports. Overall prognosis is poor with most patients succumbing to the disease within 14 months15 and surgical resection, including affected lymph nodes, with or without adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, remains the mainstay of treatment. Nevertheless, long-term survival following lobectomy or pneumonectomy has been reported.15–18

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Gisella Puga Yung for her help in formatting the manuscript.

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.

References

- Chang AE, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma: a summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Cancer. 1998;83:1664–1678. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981015)83:8<1664::aid-cncr23>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ost D, Joseph C, Sogoloff H, Menezes G. Primary pulmonary melanoma: case report and literature review. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:62–66. doi: 10.4065/74.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MS, Jr, Drash EC. Primary melanoma of the lung. Cancer. 1968;21:154–159. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196801)21:1<154::aid-cncr2820210123>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen OA, Egedorf J. Primary malignant melanoma of the lung. Scand J Respir Dis. 1967;48:127–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Sáez L, Pita-Fernandez S, Lorenzo-Patino MJ, Arnal-Monreal F, Machuca-Santacruz J, Romero-Gonzalez J. Primary melanoma of the adrenal gland: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:273. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias M, Alberte-Woodward M, Arias S, Dapena D, Prieto A, Suarez-Penaranda JM. Primary malignant meningeal melanomatosis: a clinical, radiological and pathologic case study. Acta Neurol Belg. 2011;111:228–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Perrot M, Brundler MA, Robert Spiliopoulos A. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13:172–174. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2000.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado J, Ministro P, Araujo R, Cancela E, Castanheira A, Silva A. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4734–4738. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i42.4734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung MC, Perez EA, Molina MA, et al. Defining the role of surgery for primary gastrointestinal tract melanoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:731–738. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoes M, Cunha V, Nabais H, Riscado I, Jorge AF. Primary malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix – case report and review. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2011;32:448–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gök ND, Yildiz K, Corakci A. Primary malignant melanoma of the ovary: case report and review of the literature. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2011;27:169–172. doi: 10.5146/tjpath.2011.01069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasdemir Turkmen Samdanci E, Dogan M, Elmali C, Yasar Sargin S. Primer malignant melanoma of kidney: a case report. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2011;15:971–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DL, Allen MS. Rare pulmonary neoplasms. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:492–498. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings TA. Axiotis CA, Kress Y, Carter D. Primary malignant melanoma of the lower respiratory tract. Report of a case and literature review. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;94:649–655. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/94.5.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RW, Moran CA. Primary melanoma of the lung: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of eight cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1196–1202. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199710000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed RJ, 3rd, Kent EM. Solitary pulmonary melanomas: two case reports. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1964;48:226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid JD, Mehta VT. Melanoma of the lower respiratory tract. Cancer. 1966;19:627–631. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196605)19:5<627::aid-cncr2820190505>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitelman E. Donenfeld P, Kay K, Takabe K, Andaz S, Fox S. Successful treatment of primary pulmonary melanoma. J Thorac Dis. 2011;3:207–208. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2011.04.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]