Abstract

Background

Multiple prospective studies have demonstrated that epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 19 and exon 21 mutations are the most powerful predictive biomarkers of response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, there are few studies focused on patients with double mutations compared with a single mutation.

Methods

We retrospectively screened 1,525 samples of Chinese patients with advanced NSCLC who underwent EGFR mutation detections in tumor tissues at Peking University Cancer Hospital between February 2006 and March 2011. Thirty-two cases harboring double mutations were included in this study. The Kaplan-Meier univariate analysis for prognostic factors of survival was applied.

Results

Patients with double mutations accounted for 2.1% (32/1525) of the overall tested samples. Double mutations were more common in female, adenocarcinoma, non-smokers, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG0)-1 and stage IV patients. Twenty-one patients with double mutations were treated with EGFR-TKIs. The objective response rate (ORR) was 23.8%, and the disease control rate (DCR) was 76.2%. In the first-line therapy, the ORR was 16.7%, and the DCR was 66.7%. In univariate analysis, gender, smoking-status, TKI type and TKI response were correlated with progression-free survival, and patients with ECOG 0–1 had longer overall survival.

Conclusions

Patients with double mutations had a low objective response rate when treated with EGFR-TKIs compared with single EGFR exon 19 or exon 21 mutations.

Keywords: DHPLC, double mutations, epidermal growth factor receptor, lung neoplasms, tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Introduction

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a transmembrane glycoprotein that is overexpressed in more than 40% of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC).1–5 The activating EGFR signal pathway is related to the proliferation and resistance to apoptosis of cancer cells. In patients with radiographic responses to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as gefitinib and erlotinib, several somatic mutations in EGFR have been identified, which mainly distribute in intracellular tyrosine kinase domains from exon 18 to exon 21, including G719S, 19 Del, T790M, L858R, and L861Q.6,7 Although many EGFR mutant subtypes have been reported, not all are associated with responsiveness to EGFR-TKIs. For instance, T790M was thought to be a secondary mutation resistant to EGFR-TKIs, and exon 20-point mutation has proven to be a poor predictor to EGFR-TKIs. Together with previous studies, the two most common EGFR mutant subtypes, accounting for 85% to 90% of EGFR mutations, are the EGFR exon 19 deletion mutation and the exon 21 L858R point mutation. Patients harboring either of these two mutations represent a classic subtype of NSCLC, with characteristics of Asian ethnicity, female gender, non-smoking status, or adenocarcinoma histology, and, importantly, superior response to EGFR-TKIs and even improved overall survival (OS) time compared to those without EGFR mutations.8

Theoretically, the different mutations may cause different types of structural change in the tyrosine kinase domain and, correspondingly, affect subsequent clinical outcomes. This speculation has been confirmed by some translational studies. Riely et al. reported that patients with EGFR exon 19 deletion mutations had a longer progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival than those with EGFR L858R point mutation.9 Wu et al. found that EGFR exon 20 mutations in NSCLC patients resulted in poorer responsiveness to gefitinib treatment.10 The outcomes of these studies suggest that the discrepancy among mutation type might lead to a distinct clinical course. Single mutation in exon 19 or exon 21 can cause structural transformation in intracellular tyrosine kinases, which facilitate the binding and improve the efficacy of EGFR-TKIs. However, whether concurrent mutation of exon 19 and exon 21 may further improve clinical outcomes remains unclear.

In clinical practice, we found that some patients harboring concurrent exon 19 and 21 mutations seemed to experience an inferior clinical course in response to EGFR-TKIs, which was different from those with single EGFR mutation. Therefore, we speculated that the double mutations might define a unique subset of NSCLC. To date, few published studies have shown the detailed clinical profiles of this subset of lung cancer. To explore the occurrence and clinical features of EGFR double mutations, we screened 1525 patients with sufficient tumor specimens for EGFR mutation detection and identified a total of 32 patients with concurrent exon 19 and exon 21 mutations. Further analyses of clinical characteristics, response profiles to treatment, and survival outcomes were undertaken.

Methods

Study population and data collection

This study retrospectively screened 1525 Chinese patients with advanced NSCLC who underwent EGFR mutation detections in tumor tissues at the Peking University Cancer Hospital between February 2006 and March 2011. Further analyses were undertaken in enrolled patients who met the following criteria: (i) histologically proven NSCLC; (ii) harboring concurrent exon 19 and exon 21 mutations; and (iii) stage III or IV according to the 2009 Tumor Node Metastasis (TNM) International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASCL) staging system. Biopsy tissue for genetic analysis was obtained from all patients. The Institutional Review Boards of the Peking University Cancer Hospital approved the study.

For all patients, medical records were reviewed to extract data on clinico-pathologic characteristics. At the time of data collection, we examined treatment regimens, response rates, and survival outcomes. Responses were classified by using standard Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). PFS was measured from the first day of treatment until radiologic progression or death. OS was measured from the date of diagnosis of advanced NSCLC until the date of death. Patients without a known date of death were censored at the time of last follow-up.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation detection by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC)

Specimen collection, DNA extraction and denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) were performed according to methods described in our prior publication.11 To confirm mutations identified by DHPLC, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products used for DHPLC were directly sequenced bidirectionally using a Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The reactions were carried out in an automated DNA analyzer (ABI Prism 377; Applied Biosystems).

Statistical analysis

The variables included for analysis in this study were age, gender, smoking history, performance status score, histological type, and EGFR mutation status. The differences between clinico-pathologic characteristics and treatment response were analyzed using Pearson's χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. The median PFS and median survival time (MST) were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and comparisons between groups were made using log-rank tests. All statistical tests were two sided, with significance defined as P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows Version 17.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL).

Results

Characteristic prevalence of 32 patients with concurrence of exon 19 and 21 mutations

From February 2006 to March 2011 at the Peking University Cancer Hospital, 1525 patients with NSCLC provided sufficient tissue samples for EGFR mutation detection. The EGFR mutation rate of the present cohort was 34.9% (532/1525), including 337 patients harboring exon 19 mutations (22.1%), and 227 patients with exon 21 mutations (14.6%). The predominant histological type was adenocarcinoma, and the majority of patients were female and never smokers. In the cohort of EGFR mutation population, 500 patients had single EGFR mutation of either exon 19 or exon 21 (32.8%), and 32 patients were identified with concurrent exon 19 and exon 21 mutations. The concurrence rate of EGFR double mutations accounted for 6.9% of patients with EGFR mutations and 2.1% of detected patients.

Table 1 lists the detailed information of 32 patients with concurrent mutation of EGFR exon 19 and 21.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 32 epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) double mutation patients

| Total | 32 | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 19 | 59.4 |

| Male | 13 | 40.6 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median | 57.3 | |

| Range | 34–76 | |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma (Including 3 BAC) | 30 | 93.8 |

| Squamous carcinoma | 1 | 3.1 |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 1 | 3.1 |

| Smoking history | ||

| Ever/current | 10 | 31.3 |

| Never | 22 | 68.8 |

| ECOG | ||

| 0–1 | 29 | 90.6 |

| 2 | 3 | 9.4 |

| Stage | ||

| IIIA | 2 | 6.2 |

| IIIB | 1 | 3.1 |

| IV | 29 | 90.6 |

BAC, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Results indicated that patients were more likely to be female (19 patients, 59.4%), never smokers (22 patients, 68.8%), with adenocarcinoma (30 patients, 93.8%) or stage IV disease (29 patients, 90.6%).

Efficacy and survival outcomes of EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in sub-population with concurrent EGFR exon 19 and 21 mutations

In the cohort of 32 patients with concurrent EGFR exon 19 and 21 mutations, 21 patients underwent EGFR-TKI therapy, including six patients as first-line therapy, seven as second-line therapy, six as third-line therapy, one as fifth-line therapy, and one as maintenance therapy after first-line chemotherapy. The objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR) were 23.8% (5/21) and 76.2% (16/21), respectively, including five of partial response (PR), 11 of stable disease (SD) and five of progressive disease (PD). In patients treated with EGFR-TKIs as first-line therapy, the ORR was 16.7% (1/6) and the DCR was 66.7% (4/6). In patients treated with EGFR-TKIs as post first-line therapy, the ORR was 26.7% (4/15) and the DCR was 80.0% (12/15). No characteristic factors, such as gender, smoking status, histology, or PS score were found to be related to ORR or DCR.

At the time of writing of this manuscript, 15 patients receiving EGFR-TKIs were classified as PD (71.4%) and 10 patients died (47.6%). The median follow-up time was 16.2 months (ranging from 1.7 to 58.5 months). The median PFS and OS were 7.3 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.5 to 31.6 months) and 23.8 months (95% CI, 1.7 to 58.5 months), respectively. In the cohort of patients who received EGFR-TKIs, we observed five patients who achieved a short PFS of about one month (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical features of 21 double mutated patients receiving epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR-TKI) therapy

| Case | Age/Gender | Cell type | Smoking status | Prior regimen | Staging | Maximal response | PFS (months) | Mortality | Survival (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 34/F | ADC | Non | 1 | IV | PR | 6.1 | Death | 32.5 |

| 2 | 69/F | ADC | Non | 2 | IV | PR | 10.8 | Death | 26.6 |

| 3 | 42/F | ADC | Non | 1 | IV | SD | 5.1 | Death | 15.0 |

| 4 | 56/M | ADC | Current | 4 | IV | SD | 5.4 | Death | 40.0 |

| 5 | 63/F | ADC | Non | 0 | IV | PR | 27.1 | Alive | 28.1 |

| 6 | 44/F | ADC | Non | 0 | IV | SD | 23.9 | Alive | 28.6 |

| 7 | 52/F | ADC | Non | 1 | IV | PD | 1.2 | Death | 11.6 |

| 8 | 69/F | ADC | Current | 1 | IV | PD | 0.5 | Death | 31.2 |

| 9 | 60/F | ADC | Non | 2 | IV | SD | 31.6 | Alive | 40.8 |

| 10 | 60/F | ADC | Current | 0 | IV | PD | 1.5 | Death | 23.8 |

| 11 | 35/F | ADC | Non | 2 | IV | PR | 8.3 | Death | 16.2 |

| 12 | 44/F | AdSCC | Non | 2 | IV | SD | 20.3 | Alive | 26 |

| 13 | 76/M | SCC | Current | 0 | IV | PD | 1.0 | Alive | 1.7 |

| 14 | 50/M | ADC | Non | 0 | IV | SD | 14.2 | Alive | 27.7 |

| 15 | 56/F | ADC | Current | 0 | IV | SD | 26.4 | Alive | 26.4 |

| 16 | 52/F | ADC | Non | 1 | IV | SD | 7.1 | Alive | 9.5 |

| 17 | 53/F | ADC | Non | 2 | IV | SD | 7.8 | Alive | 18.2 |

| 18 | 67/M | ADC | Current | 1 | IIIA | PD | 1.1 | Alive | 9.4 |

| 19 | 60/F | ADC | Non | 1† | IV | SD | 7.3 | Death | 17.0 |

| 20 | 60/M | ADC | Current | 2 | IV | PR | 4.7 | Alive | 7.6 |

| 21 | 56/F | ADC | Non | 1 | IV | SD | 10.4 | Death | 17.7 |

Patient 19 received EGFR-TKI as maintenance therapy. ADC, adenocarcinoma; AdSCC, adenosquamous carcinoma; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SD, stable disease.

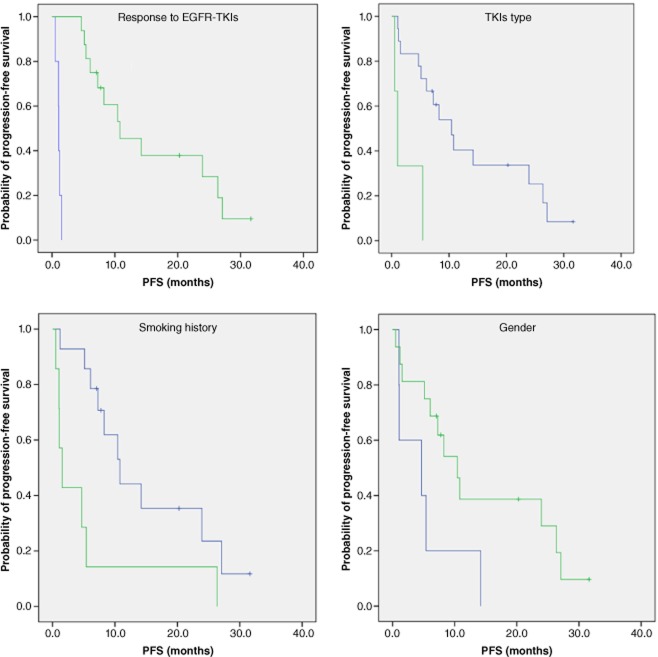

Furthermore, the correlations of several clinical characteristics with PFS were analyzed as univariate factors and showed that female patients, a non-smoking history, gefitinib treatment, and obtaining disease control after EGFR-TKIs might have superior PFS, compared with patients with counter characteristics (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) double mutant patients with different clinical characteristics treated with EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (response; EGFR-TKIs type; smoking history; gender).  , progressive disease (PD), n = 5, median progression-free survival (PFS): 1.1 months;

, progressive disease (PD), n = 5, median progression-free survival (PFS): 1.1 months;  , partial response + stable disease (PR+SD), n = 16, median PFS: 10.8 months, p = 0.000;

, partial response + stable disease (PR+SD), n = 16, median PFS: 10.8 months, p = 0.000;  , Iressa, n = 18, median PFS: 10.4 months;

, Iressa, n = 18, median PFS: 10.4 months;  , Tarceva, n = 3, median PFS: 10 months, p = 0.001;

, Tarceva, n = 3, median PFS: 10 months, p = 0.001;  , Non-smokers, n = 14, median PFS: 10.8 months;

, Non-smokers, n = 14, median PFS: 10.8 months;  , Smokers, n = 7, median PFS: 1.5 months, p = 0.012;

, Smokers, n = 7, median PFS: 1.5 months, p = 0.012;  , Male, n = 5, median PFS: 4.7 months;

, Male, n = 5, median PFS: 4.7 months;  , Female n = 16 median PFS: 10.4 months, p = 0.040.

, Female n = 16 median PFS: 10.4 months, p = 0.040.

Interestingly, we identified that there was no difference in PFS between those who achieved PR and SD (PFS 8.5 months, 95% CI 3.5–13.0 months vs. PFS 14.2 months, 95% CI, 0.0–30.0 months, P = 0.358). We also found no difference in PFS when patients achieved PR or SD after EGFR-TKIs as first–line therapy (PR vs. SD, 27.1 months vs. 23.9 months, P = 0.182); and post first-line therapy (PR vs. SD, PFS 6.1 months vs. 10.4 months, P = 0.254).

Survival outcomes of 31 followed-up patients

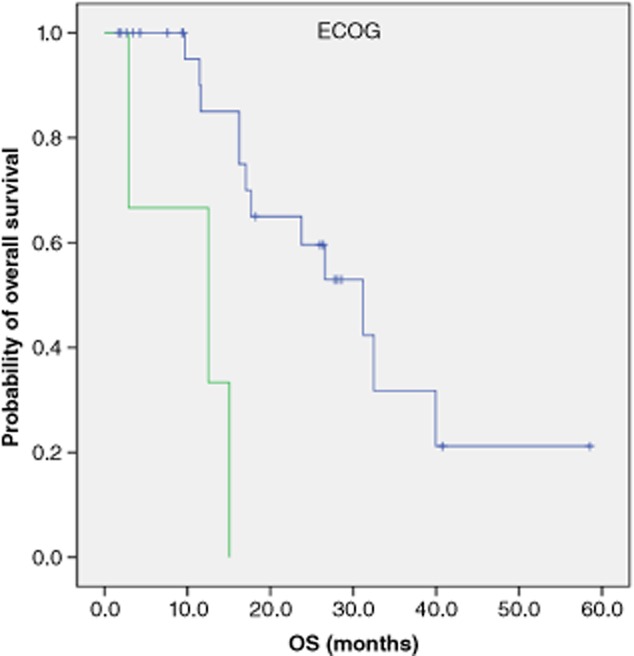

The Kaplan-Meier method was applied to analyze the correlations between OS and clinical characteristics including gender, smoking history, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, therapeutic regimens (TKI, first-line platinum-based or lack of therapy) and response (DCR vs. ORR after EGFR-TKI). ECOG PS was correlated with overall survival (ECOG 0–1 vs. ECOG 2, PFS 31.2 months, 95% CI: 20.0–42.4 months vs. PFS 12.5 months, 95% CI: 0–28.0 months, P = 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for 31 followed-up patients with different Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) status.  , 0–1, n = 28, median survival time (MST): 31.2 months;

, 0–1, n = 28, median survival time (MST): 31.2 months;  , 2, n = 3, MST: 12.5 months, p = 0.001.

, 2, n = 3, MST: 12.5 months, p = 0.001.

Discussion

Currently, EGFR mutations are still the most powerful predictors of EGFR-TKIs. Several randomized, controlled, and multi-centered clinical trials have demonstrated that when patients with EGFR mutations receive first-line EGFR-TKI therapy, the ORR is between 62.1% and 84.6%, and the median PFS is between 8.4 and 13.1 months.12–16 At present, EGFR sensitive mutations mainly refer to the EGFR exon 19 (19Del) and exon 21 mutations (L858R). Whether 19Del is superior to L858R has not been definitively concluded. In the past few years, EGFR double mutations have been reported in few clinical trials. In an ISEL trial, 215 patients were tested for EGFR mutations, but only one patient had double mutations,17 accounting for 0.47% of overall patients. In a BR21 trial, only three out of 204 patients had double mutations,18 accounting for 1.5% of overall patients. In an IPASS trial, only four out of 437 patients (0.92%) had double mutations.12The present study found that EGFR double mutations accounted for 2.1% of tested patients, which is obviously higher than previous reports. Two factors may affect the results. The first factor is the difference in detection methods. Sequencing and Amplified Refractory Mutation System methods were applied in ISEL and BR21, however, our study applied the DHPLC method. The second factor is the different proportion of patients. The ISEL and BR21 trial enrolled many American and European patients, but the IPASS trial recruited nearly all pan-Asian patients. Several studies have demonstrated that EGFR mutation more commonly occurs in east-Asian patients. All patients in our study were Chinese, therefore, these patients were more likely to carry an EGFR mutation, and, thus, the possibility of finding double mutations was higher. Another study which came out of China analyzed 145 Chinese NSCLC patients (including 78 adenocarcinoma and 77 squamous cell carcinoma), and identified five patients (3.4%) with EGFR exon 19 and exon 21 double mutations, similar to our study.19

To our knowledge, there has been only one study exploring the correlation between EGFR double mutations and EGFR-TKI response. In Zhang et al.'s study, three out of five patients with EGFR double mutations were treated with EGFR-TKIs. Two patients (67%) achieved PR, and their PFS rates were 19 and 21 months, respectively. One patient had PD, with a PFS rate of 1.5 months. Zhang et al. further demonstrated that cell lines with double mutations responded better than those with a single mutation when treated with either gefitinib or erlotinib. Our study revealed that 21 patients harboring double mutations received TKI therapy, but the ORR was only 23.8%. In those patients treated with first-line EGFR-TKIs, the ORR was only 16.7%, much lower than patients with single EGFR exon 19 or exon 21 mutations. However, 50% (3/6) of patients in first-line therapy and 52.4% (11/21) of overall patients achieved stable disease.

The mechanisms for the low response rate to EGFR-TKIs in patients with double EGFR mutations have not been clarified. Perhaps the molecular conformation change of the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain induced by EGFR double mutations leads to the difference in response. In general, there is equilibrium between EGFR-TK phosphorylation and dephosphorylation.20 Under most conditions, dephosphorylation exists in a dominant manner, and, therefore, EGFR-TK maintains an inactive status. At the same time, the side strand of L858 is embedded in the hydrophobic pocket. Once EGFR exon 21 L858R substitution mutation has occurred, the L858 side strand tends to escape from the hydrophobic pocket and expose the soluble surface.21 The phosphorylated active state of EGFR-TK will then be dominant. Furthermore, when EGFR-TKIs bound to the EGFR-TK, the alanine ring of TKIs, rotates by approximately 180 degrees9 the small molecule TKIs are able to adopt an alternate conformation. It is possible that EGFR 19Del has similar molecular conformation change under the influence of EGFR-TKIs. Coexistence of 19Del and L858R mutations may affect the crystal structures and molecular conformation of the EGFR-TK adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding site, especially the active domain, resulting in reduced EGFR-TKI binding to the EGFR-TK domain, ultimately affecting the response of EGFR-TKIs.

Although patients harboring EGFR double mutations had a lower response to EGFR-TKIs, the PFS and OS in this subgroup of patients were similar to those patients carrying only EGFR 19 or 21 mutations in previous studies. In patients treated with first-line EGFR-TKI therapy, the PFS of patients who achieved PR and SD was 27.1 months and 23.9 months, respectively, which was better than the results of the previous clinical trial. In patients who received EGFR-TKIs as second- or further line therapy, the PR and SD achieved were 6.1 months and 10.4 months, again, similar to previous studies.14–16 It seems that when treated with EGFR-TKIs, SD may transform into a survival prolongation in patients with double mutations of EGFR.

We also found that EGFR double mutations are more prevalent in female, adenocarcinoma, non-smokers, ECOG0-1, stage IV patients. Univariate analysis showed that female, non-smoking patients achieved PR or SD, and those treated with gefitinib had longer PFS. Meanwhile patients with ECOG 0–1 had longer OS.

Conclusion

In summary, EGFR exon 19 and exon 21 double mutations are rare. The ORR to EGFR-TKI therapy in this subgroup is lower than in single mutation groups. Patients achieved SD when treated with EGFR-TKIs had a survival advantage. However, this study was a retrospective study, and further investigations are needed to verify the conclusions.

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.

References

- Hirsch FR, Scagliotti GV, Langer CJ, Varella-Garcia M, Franklin WA. Epidermal growth factor family of receptors in preneoplasia and lung cancer: perspectives for targeted therapies. Lung Cancer. 2003;41 (Suppl. 1):29–42. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabender J, Danenberg KD, Metzger R, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor and HER2-neu mRNA expression in non-small cell lung cancer is correlated with survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1850–1855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch V, Klimstra D, Venkatraman E, Pisters PW, Lagenfeld J, Dmitrovsky E. Overexpression of the epidermal growth factor receptor and its ligand transforming growth factor alpha is frequent in resectable non-small cell lung cancer but does not predict tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:515–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga C. ErbB-targeted therapeutic approaches in human cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284:122–130. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch V, Baselga J, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. Differential expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor and its ligands in primary non-small cell lung cancers and adjacent benign lung. Cancer Res. 1993;53 (10 Suppl.):2379–2385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shegematsu H, Lin L, Takahashi T, et al. Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:339–346. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo E, Baselga J. Ethnic differences in response to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2158–2163. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riely GJ, Pao W, Pham DK, et al. Clinical course of patients with non-small cell lung cancer and epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 and exon 21 mutations treated with gefitinib or erlotinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:839–844. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JY, Wu SG, Yang CH, et al. Lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor exon 20 mutations is associated with poor gefitinib treatment response. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4877–4882. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai H, Mao L, Wang HS, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in plasma DNA samples predict tumor response in Chinese patients with stages IIIB to IV non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2653–2659. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin–paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosell R, Moran T, Queralt C, et al. Screening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:958–967. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib in a phase III placebo-controlled study in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5034–5042. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu CQ, da Cunha Santos G, Ding K, et al. Role of KRAS and EGFR as biomarkers of response to erlotinib in National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4268–4275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang GC, Lin JY, Wang Z, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor double activating mutations involving both exons 19 and 21 exist in Chinese non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin Oncol. 2007;19:499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Petri ET, Halmos B, Boggon TJ. Structure and clinical relevance of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1742–1751. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun CH, Boggon TJ, Li Y, et al. Structures of lung cancer-derived EGFR mutants and inhibitor complexes: mechanism of activation and insights into differential inhibitor sensitivity. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]